History of the Republic of the Congo

Encyclopedia

Republic of the Congo

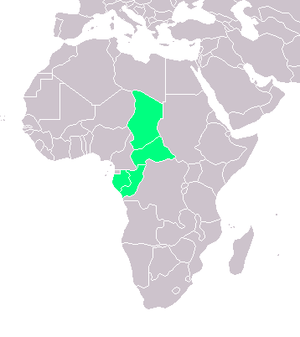

The Republic of the Congo , sometimes known locally as Congo-Brazzaville, is a state in Central Africa. It is bordered by Gabon, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo , the Angolan exclave province of Cabinda, and the Gulf of Guinea.The region was dominated by...

has been marked by French colonization, a transition to independence, Marxist-Leninism, and the transition to a market-oriented economy.

Bantus and Pygmies

The earliest inhabitants of the region comprising present-day Congo were the Bambuti people. The Bambuti were linked to PygmyPygmy

Pygmy is a term used for various ethnic groups worldwide whose average height is unusually short; anthropologists define pygmy as any group whose adult men grow to less than 150 cm in average height. A member of a slightly taller group is termed "pygmoid." The best known pygmies are the Aka,...

tribes whose Stone Age

Stone Age

The Stone Age is a broad prehistoric period, lasting about 2.5 million years , during which humans and their predecessor species in the genus Homo, as well as the earlier partly contemporary genera Australopithecus and Paranthropus, widely used exclusively stone as their hard material in the...

culture was slowly replaced by Bantu tribes coming from regions north of present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is a state located in Central Africa. It is the second largest country in Africa by area and the eleventh largest in the world...

about 2,000 years ago, introducing Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

culture to the region. The main Bantu tribe living in the region were the Kongo

Kongo people

The Bakongo or the Kongo people , also sometimes referred to as Kongolese or Congolese, is a Bantu ethnic group which lives along the Atlantic coast of Africa from Pointe-Noire to Luanda, Angola...

, also known as Bakongo, who established mostly weak and unstable kingdoms along the mouth, north and south of the Congo River

Congo River

The Congo River is a river in Africa, and is the deepest river in the world, with measured depths in excess of . It is the second largest river in the world by volume of water discharged, though it has only one-fifth the volume of the world's largest river, the Amazon...

. The capital of this Congolese kingdom, Mbanza Kongo, later baptized as São Salvador by the Portuguese

Portuguese people

The Portuguese are a nation and ethnic group native to the country of Portugal, in the west of the Iberian peninsula of south-west Europe. Their language is Portuguese, and Roman Catholicism is the predominant religion....

, is a town in northern Angola

Angola

Angola, officially the Republic of Angola , is a country in south-central Africa bordered by Namibia on the south, the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the north, and Zambia on the east; its west coast is on the Atlantic Ocean with Luanda as its capital city...

near the border with the DRC.

From the capital they ruled over an empire encompassing large parts of present-day Angola, the Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ruling over nearby tributary states often by appointing sons of the Kongo kings to head these states. It had six so-called provinces called Mbemba, Soyo

Soyo

Soyo is a city located in the province of Zaire in Angola. Soyo recently became the largest oil-producing region in the country, with an estimate of .-Early history:...

, Mbamba, Mbata, Nsundi

Nsundi

Nsundi was a province of the old Kingdom of Kongo whose capital lay on the Inkisi River right on the border between modern-day Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo.- History :...

and Mpangu. With the Kingdom of Loango

Loango

Loango may refer to:* Loango National Park, a national park in Western Gabon* Petit Loango, a town in Gabon* Kingdom of Loango, a pre-colonial state in what is now the Republic of Congo* Loango, a schooner wrecked in 1909 at St Ives, Cornwall...

in the north and the Kingdom of Mbundu in the south being tributary states. In the East it bordered on the Kwango river, a tributary of the Congo River. In total the kingdom is said to have had 3 to 4 million inhabitants and a surface of about 300,000 km². According to oral traditions it was established in around 1400 when King Lukena Lua Nimi conquered the kingdom of Kabunga and established Mbanza Kongo as its capital.

Portuguese exploration

This African Iron Age culture came under great pressure with the arrival of the first EuropeanEuropean ethnic groups

The ethnic groups in Europe are the various ethnic groups that reside in the nations of Europe. European ethnology is the field of anthropology focusing on Europe....

s, being in this case the Portuguese explorers

Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire , also known as the Portuguese Overseas Empire or the Portuguese Colonial Empire , was the first global empire in history...

. In Portugal, King John II

John II of Portugal

John II , the Perfect Prince , was the thirteenth king of Portugal and the Algarves...

said in order to break Venetian

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice or Venetian Republic was a state originating from the city of Venice in Northeastern Italy. It existed for over a millennium, from the late 7th century until 1797. It was formally known as the Most Serene Republic of Venice and is often referred to as La Serenissima, in...

and Ottoman

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

control over trade with the East, they needed to organise a series of expeditions southwards along the African coast with the idea of establishing direct contacts with Asia. In 1482–1483, Captain Diogo Cão

Diogo Cão

Diogo Cão was a Portuguese explorer and one of the most remarkable navigators of the Age of Discovery, who made two voyages sailing along the west coast of Africa to Namibia in the 1480s.-Early life and family:...

, sailing southwards on uncharted Congo River

Congo River

The Congo River is a river in Africa, and is the deepest river in the world, with measured depths in excess of . It is the second largest river in the world by volume of water discharged, though it has only one-fifth the volume of the world's largest river, the Amazon...

, discovered the mouth of the river, and became the first European to encounter the Kingdom of Kongo

Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo was an African kingdom located in west central Africa in what are now northern Angola, Cabinda, the Republic of the Congo, and the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo...

. In the beginning relations were limited and considered beneficial to both sides. With Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

easily being accepted by the local nobility, leading on 3 May 1491 to the baptising of king Nzinga a Nkuwu as the first Christian Congolese king João I

João I of Kongo

João I of Kongo, alias Nzinga a Nkuwu or Nkuwu Nzinga, was ruler of the Kingdom of Kongo between 1470–1506. He was baptized as João in 3 May 1491 by Portuguese missionaries.-Early reign:...

. Being replaced after his death in 1506 by his son Nzinga Mbemba who ruled as king Afonso I until 1543. Under his reign Christianity gained a strong foothold in the country with many churches being built in Mbanza of which the Kulumbimbi Cathedral (erected between 1491 and 1534) being the most impressive. In theory both the kings of Portugal and Kongo were considered equals exchanging letters as such. Kongo at some point even established diplomatic relations with the Vatican

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

, with the Pope

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

appointing a local as bishop for the region.

Slave trade

Brazil

Brazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

in 1500 and the need for labor to work on the Portuguese plantations in Brazil, Cape Verde

Cape Verde

The Republic of Cape Verde is an island country, spanning an archipelago of 10 islands located in the central Atlantic Ocean, 570 kilometres off the coast of Western Africa...

and São Tomé

São Tomé

-Transport:São Tomé is served by São Tomé International Airport with regular flights to Europe and other African Countries.-Climate:São Tomé features a tropical wet and dry climate with a relatively lengthy wet season and a short dry season. The wet season runs from October through May while the...

led Portugal to look for more slaves. As the Portuguese's demand for black slaves grew, the pressure on the Kongo kings increased. With the Kongo king Afonso I complaining in 1526 to his Portuguese counterpart, John III

John III of Portugal

John III , nicknamed o Piedoso , was the fifteenth King of Portugal and the Algarves. He was the son of King Manuel I and Maria of Aragon, the third daughter of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile...

, bitterly of the damage done to his kingdom by this trade, which was depopulating whole areas and leading to constant wars with his neighbors. At some point even members of the royal family were taken and deported as slaves to work on these plantations. It is estimated that by the end of the 18th century European traders took about 350,000 slaves from the region of the present-day Republic of Congo.

Revolts

The result was a series of revolts against Portuguese rule of which the battle of MbwilaBattle of Mbwila

At the Battle of Mbwila on October 29, 1665, Portuguese forces defeated the forces of the Kingdom of Kongo and decapitated king António I of Kongo, also called Nvita a Nkanga.-Origins of the War:...

and the revolt led by Kimpa Vita

Kimpa Vita

Beatriz Kimpa Vita , was a Congolese prophet and leader of her own Christian movement, known as Antonianism. Her teaching grew out of the traditions of the Roman Catholic Church in Kongo.-Early life:...

(Tchimpa Vita) were the most important. The Battle of Mbwila (or Battle of Ambouilla or Battle of Ulanga) was the result of a conflict between the Portuguese led by governor André Vidal de Negreiros and the Kongolese king António I concerning mining rights. With the Kongolese refusing to give the Portuguese extra territorial rights and the Portuguese angry because of Kongolese support for previous Dutch

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

invasions of the region. During the battle on 25 October 1665 an estimated 20.000 Kongolese fought against the Portuguese who won the battle thanks to the early death in battle of the Kongolese king António I.

The revolt of Kimpa Vita was another attempt to regain independence from the Portuguese. Baptised around 1684 as Dona Béatrice, Kimpa Vita was raised Catholic and being very pious she became a nun seeing visions of St. Anthony of Padua ordering her to restore thee kingdom of Kongo to its former glory. Creating the Anthonian prophetic movement she interfered directly in the then civil war between the three members of the local nobility claiming the Kongolese throne, João II, Pedro IV and Pedro Kibenga. In it she took sides against Pedro IV, considered the favorite of the Portuguese. Her revolt, during which she captured the capital Mbanza Kongo, was short lived. She was captured by the forces of Pedro IV and under orders of Portuguese Capuchin Friars condemned for being a witch and a heretic and consequently burned to death. For many African nationalists she is the African version of Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc

Saint Joan of Arc, nicknamed "The Maid of Orléans" , is a national heroine of France and a Roman Catholic saint. A peasant girl born in eastern France who claimed divine guidance, she led the French army to several important victories during the Hundred Years' War, which paved the way for the...

and an early symbol of African resistance against colonialism.

Congo's disintegration

Teke

-People:* Fatih Tekke, a Turkish footballer* Teke people or Bateke, a Central African ethnic group** Teke languages, a series of Bantu languages spoken by the Teke people* Teke tribe or Tekke, a tribe of southern Turkmenistan...

was the most important, ruling over a large area encompassing present-day Brazzaville

Brazzaville

-Transport:The city is home to Maya-Maya Airport and a railway station on the Congo-Ocean Railway. It is also an important river port, with ferries sailing to Kinshasa and to Bangui via Impfondo...

and Kinshasa

Kinshasa

Kinshasa is the capital and largest city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The city is located on the Congo River....

. Portugal's position in Europe suffered a major change in 1580 when the Kingdoms of Spain and Portugal were united by a personal union

Personal union

A personal union is the combination by which two or more different states have the same monarch while their boundaries, their laws and their interests remain distinct. It should not be confused with a federation which is internationally considered a single state...

under King Philip

Philip II of Spain

Philip II was King of Spain, Portugal, Naples, Sicily, and, while married to Mary I, King of England and Ireland. He was lord of the Seventeen Provinces from 1556 until 1581, holding various titles for the individual territories such as duke or count....

, creating the Iberian Union

Iberian Union

The Iberian union was a political unit that governed all of the Iberian Peninsula south of the Pyrenees from 1580–1640, through a dynastic union between the monarchies of Portugal and Spain after the War of the Portuguese Succession...

which lasted until 1640. This resulted in a diminished role for Portugal in African affairs, including the area around the mouth of the Congo River. The Kingdom of Congo was reduced to a small enclave in the north of Angola with King Pedro V in 1888 finally accepting to become a vassal of the Portuguese. The Portuguese abolished the kingdom after the revolt of the Kongolese in 1914.

Scramble for raw materials

The period leading up to the Berlin ConferenceBerlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–85 regulated European colonization and trade in Africa during the New Imperialism period, and coincided with Germany's sudden emergence as an imperial power...

on Africa saw a rush by the major European powers to increase their control of the African continent. The rise in Western Europe of capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

and the consequent industrialization led to a fast growing demand for African raw materials like rubber

Rubber

Natural rubber, also called India rubber or caoutchouc, is an elastomer that was originally derived from latex, a milky colloid produced by some plants. The plants would be ‘tapped’, that is, an incision made into the bark of the tree and the sticky, milk colored latex sap collected and refined...

, palm oil

Palm oil

Palm oil, coconut oil and palm kernel oil are edible plant oils derived from the fruits of palm trees. Palm oil is extracted from the pulp of the fruit of the oil palm Elaeis guineensis; palm kernel oil is derived from the kernel of the oil palm and coconut oil is derived from the kernel of the...

and cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

. Those who had these raw materials could have their economy grow strong. Others would lose out. This resulted in a new and more intensified scramble for Africa

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also known as the Race for Africa or Partition of Africa was a process of invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period, between 1881 and World War I in 1914...

.

The Congo River hereby was a prime target for this new conquest by the European nations. Here the French, the Belgian King Leopold II and the Portuguese, in close cooperation with the British, fought for control of this area. Resulting in the division of the mouth of the Congo River between Portugal, who obtained Cabinda

Cabinda (province)

Cabinda is an exclave and province of Angola, a status that has been disputed by many political organizations in the territory. The capital city is also called Cabinda. The province is divided into four municipalities - Belize, Buco Zau, Cabinda and Cacongo.Modern Cabinda is the result of a fusion...

, an enclave north of the Congo River situated on the Atlantic Coast, the French who seized the large area north of the River, and king Leopold II gaining only a small foothold at the mouth of the Congo River but obtaining the huge hinterland, the present-day Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire

Zaire

The Republic of Zaire was the name of the present Democratic Republic of the Congo between 27 October 1971 and 17 May 1997. The name of Zaire derives from the , itself an adaptation of the Kongo word nzere or nzadi, or "the river that swallows all rivers".-Self-proclaimed Father of the Nation:In...

). Hereby Leopold II obtained control via his International African Society and later the International Congolese Society, so-called philanthropic organizations who hired the British explorer Henry Morton Stanley

Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley, GCB, born John Rowlands , was a Welsh journalist and explorer famous for his exploration of Africa and his search for David Livingstone. Upon finding Livingstone, Stanley allegedly uttered the now-famous greeting, "Dr...

to establish its authority. This resulted in the creation of the Congo Free State

Congo Free State

The Congo Free State was a large area in Central Africa which was privately controlled by Leopold II, King of the Belgians. Its origins lay in Leopold's attracting scientific, and humanitarian backing for a non-governmental organization, the Association internationale africaine...

, the private empire of Leopold II. On November 15, 1908 the Belgian parliament annexed the colony, the reign of Leopold II over Congo being discredited.

Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza

On the north bank of the river arrived the French explorer Pierre Savorgnan de BrazzaPierre Savorgnan de Brazza

Pietro Paolo Savorgnan di Brazzà, best known as Pierre Paul François Camille Savorgnan de Brazza , was a Franco-Italian explorer, born in Italy and later naturalized Frenchman...

, born in the Italian city of Rome in 1852. As a French naval officer he refused to work for the International African Society and instead helped the French in their conquest of the area north of the Congo River. Traveling from the Atlantic Ocean coast in present-day Gabon via the rivers Ogooué and Lefini

Lefini River

Lefini River is a river of the Republic of Congo and a tributary of the Congo River....

he arrived in 1880 in the kingdom of the Téké where on 10 September 1880 he signed the treaty with king Makoko

Makoko

Makoko is a slum neighborhood located in Lagos, Nigeria. At present its population is considered to be 85,840; however, the area was not officially counted as part of the 2007 census and the population today is considered to be much higher. Established in the 18th century primarily as a fishing...

establishing French control over the region and making his capital soon afterwards at the small village named Mfoa later to be called Brazzaville.

Establishing control

Indigénat

The Code de l'indigénat was a set of laws creating, in practice, an inferior legal status for natives of French Colonies from 1887 until 1944–1947. First put in place in Algeria, it was applied across the French Colonial Empire in 1887–1889...

Act. A law, which introduced forced labor, made it illegal for the local population to publicly air its grievances and excluded them from all the important jobs.

Because the French government did not want to spend too much money on its colony it allowed for the establishment of the so-called Concessionary Companies, monopolies given a free hand to exploit the colony's resources except at a few strategic places, mainly around the Congo River. Most of these companies failed because of a shortage of funds. In 1911 parts of the colony (the so called New Cameroon territories) were ceded to the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

in exchange for German recognition of France's rights to Morocco. The German rule lasted only five years. New Cameroon returned to France in 1916, after the fall of German forces in Africa.

French rule was brutal and led to many thousands of deaths. The construction between 1921 and 1934 of the 511 km long railway, the Chemin de Fer Congo-Océan between Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire

Pointe-Noire

Pointe-Noire is the second largest city in the Republic of the Congo, following the capital of Brazzaville, and an autonomous department since 2004. Before this date it was the capital of the Kouilou region . It is situated on a headland between Pointe-Noire Bay and the Atlantic Ocean...

is for example said to have cost the lives of around 23,000 locals and a few hundred Europeans. Any resistance against French colonial rule, however small, was brutally repressed.

French administration

The first name given officially on 1 August 1886 for the new colony was Colony of Gabon and Congo. On 30 April 1891 this was renamed Colony of French Congo, consisting of Gabon and Middle Congo, the name the French gave to Congo-Brazzaville at that time. On 15 January 1910 the colony again was renamed to French Equatorial AfricaFrench Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa or the AEF was the federation of French colonial possessions in Middle Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River to the Sahara Desert.-History:...

(Afrique Equatoriale Française or AEF), this time it also included Chad

Chad

Chad , officially known as the Republic of Chad, is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic to the south, Cameroon and Nigeria to the southwest, and Niger to the west...

and Oubangui-Chari

Oubangui-Chari

Oubangui-Chari, or Ubangi-Shari, was a French territory in central Africa which later became the independent Central African Republic . French activity in the area began in 1889 with the establishment of an outpost at Bangui, now the capital of CAR. The territory was named in 1894.In 1903, French...

, nowadays the Central African Republic

Central African Republic

The Central African Republic , is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It borders Chad in the north, Sudan in the north east, South Sudan in the east, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of the Congo in the south, and Cameroon in the west. The CAR covers a land area of about ,...

. Congo-Brazzaville gained autonomy on the November 28, 1958 and independence from France on the August 15, 1960.

The French government ruled it through a Governor-General until the elections of 1957 when a High Commissioner of the République took over. Ruling as Colonial Heads of French Equatorial Africa

Colonial heads of French Equatorial Africa

-See also:*French Equatorial Africa*Cameroon**French Cameroon*Chad*Central African Republic*Democratic Republic of the Congo*Republic of the Congo*Guinea*Gabon*Lists of office-holders...

Total population in 1950 for the whole AEF was 4,143,922, except for around 15,000 al of them indigenous people. The capital of the AEF was Brazzaville, for Middle Congo the capital was Pointe Noire.

World War II

As with the arrival of the Portuguese events in Europe again had a deep impact on the affairs of Congo-Brazzaville, and Africa in general. Marshal Philippe PétainPhilippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain , generally known as Philippe Pétain or Marshal Pétain , was a French general who reached the distinction of Marshal of France, and was later Chief of State of Vichy France , from 1940 to 1944...

surrendered to Germany on 22 June 1940, and this gave birth to the so-called Vichy France

Vichy France

Vichy France, Vichy Regime, or Vichy Government, are common terms used to describe the government of France that collaborated with the Axis powers from July 1940 to August 1944. This government succeeded the Third Republic and preceded the Provisional Government of the French Republic...

republic. Pétain had earlier refused to continue the war against Germany from African territory alongside Great Britain. With the help of a handful of local French administrators and officers, the British, and the Belgian government in exile Charles de Gaulle

Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle was a French general and statesman who led the Free French Forces during World War II. He later founded the French Fifth Republic in 1958 and served as its first President from 1959 to 1969....

's Free French won over large parts of the French Empire. Politicians such as René Pleven

René Pleven

René Pléven was a notable French politician of the Fourth Republic. A member of the Free French, he helped found the Democratic and Socialist Union of the Resistance , a political party that was meant to be a successor to the wartime Resistance movement...

, who later became Prime Minister, and officers as General Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque

Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque

Philippe François Marie, comte de Hauteclocque, then Leclerc de Hauteclocque, by a 1945 decree that incorporated his French Resistance alias Jacques-Philippe Leclerc to his name, , was a French general during World War II...

, Lieutenant René Amiot, Captain Raymond Delange, Colonel Edgar De Larminat and Adolphe Sicé helped him to gain control of the AEF territory. In three days troops loyal to De Gaulle took control of Chad (26 August 1940), Cameroon (27 August) and of Middle Congo (the 28th of August). Brazzaville hereby became the capital of the so-called Free French in Africa, ruled in theory by a Conseil de défense de l'Empire set up by De Gaulle on 27 October 1940.

Felix Eboué

In this revolt the then-governor of Chad Félix EbouéFélix Éboué

Félix Adolphe Éboué was a Black French colonial administrator and Free French leader. He was the first black French man appointed to high post in the French colonies, when appointed as Governor of Guadeloupe in 1936...

played a key role. Because of this and his earlier support for De Gaulle he became Governor General of the Afrique Equatoriale Française (AEF) in 1940, the first not white to achieve this position in French colonial history. Born in 1884 in French Guiana

French Guiana

French Guiana is an overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department located on the northern Atlantic coast of South America. It has borders with two nations, Brazil to the east and south, and Suriname to the west...

this descendant of African slaves was a key figure together with René Pleven in the organisation by the De Gaulle government of the Brazzaville Conference of 1944

Brazzaville Conference of 1944

After the Fall of France during World War II, and the alignment of many West African French colonies with the Free French, Charles de Gaulle recognized the need to revise the relationship between France and its colonies in Africa...

, which took place between the January 30 and February 8, 1944 and which did set out the new direction of French colonial policies after World War II. Policies already put forward by Eboué in his 1941 book entitled "La nouvelle politique coloniale de l'A.E.F." This conference led to the abolition of forced labour and the code de l'indigénat, which made the political and social activities of the indigenous people illegal. This in turn led to the new French constitution of the Fourth Republic approved on 27 October 1946 and the election of the first African members of Parliament in Paris. For Eboué and the new French government the people in the colonies were officially part of the French empire and had a new series of rights. A severely weakened France, under pressure from the US, had hardly any option but to change its colonial policies.

Rise of nationalism

Governor General Felix EbouéFélix Éboué

Félix Adolphe Éboué was a Black French colonial administrator and Free French leader. He was the first black French man appointed to high post in the French colonies, when appointed as Governor of Guadeloupe in 1936...

had a carrot and stick

Carrot and stick

Carrot and stick is an idiom that refers to a policy of offering a combination of rewards and punishment to induce behavior. It is named in reference to a cart driver dangling a carrot in front of a mule and holding a stick behind it...

approach to local Congolese grievances. While allowing certain freedoms he brutally repressed any activities deemed dangerous to French colonial control. The case of the Congolese trade unionist André Matsoua

André Matsoua

André Grenard Matsoua was a Congolese Lari religious figure and politician, perhaps the most influential figure in Congolese politics before independence in 1960...

(Matswa) shows his tough approach to political dissent.

André Matsoua can be seen as the father of modern Congolese nationalism. His rise shows how, in spite of the Code de l'Indigénat and the brutal repression, Africans in French colonies were able to set up resistance movements to colonial rule. Local schools run by French missionaries, as elsewhere in Africa formed the basis of this rise of African nationalism. André Matsoua got his education and contacts with European thinking through the church. Born in 1899 in Mandzakala he joined the French customs administration in Brazzaville in 1919 and soon after left for France where he joined the French army to fight in Morocco

Morocco

Morocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

during the rebellion of . He returned home as a non-commissioned officer. In 1926 he in Paris formed the Association des Originaires de l'A.E.F. with the purpose of helping people from his region living in France. For this he got support from some sections of French society as the French Communist Party

French Communist Party

The French Communist Party is a political party in France which advocates the principles of communism.Although its electoral support has declined in recent decades, the PCF retains a large membership, behind only that of the Union for a Popular Movement , and considerable influence in French...

and elements within the Free Masonry movement.

When in 1929 his group also became active in Congo itself and demanded an end to the Code de l'Indigénat, things changed. In 1929 the French dissolved Matsoua's association and he together with some of his friends were jailed and sent in exile to Chad, leading to riots and a campaign of disobedience against the French administration lasting many years. He however escaped to France in 1935 where under a new identity he continued his political work. Showing his loyalty to France, in spite of the harsh repression, he joined the French army to fighting the German invasion in 1940. Wounded, he was rearrested, and sent back to Brazzaville where on 8 February 1941 he was sentenced under Felix Eboué to work in labour camps for the rest of his life. He died under unclear circumstances in prison on 13 January 1942. His supporters maintain that he was murdered, and began the Matsouanist movement, active chiefly among the Lari, even after independence.

Road to independence

The most prominent Congolese politician until 1956 was Jean-Félix TchicayaJean-Félix Tchicaya

Jean-Félix Tchicaya was a Congolese politician in the French colony of Middle Congo. He was born in Libreville on the 9th of November 1903 and a member of the royal family of the Kingdom of Loango....

, born in Libreville

Libreville

Libreville is the capital and largest city of Gabon, in west central Africa. The city is a port on the Komo River, near the Gulf of Guinea, and a trade center for a timber region. As of 2005, it has a population of 578,156.- History :...

on 9 November 1903 and a member of the royal family of the Kingdom of Loango

Kingdom of Loango

The Kingdom of Loango, also known as the Kingdom of Lwããgu, was a pre-colonial African state from approximately the 15th to the 19th century in what is now the Republic of Congo. At its height in the seventeenth century the country stretched from Cape St Catherine in the north to almost the mouth...

. Together with Ivory Coast leader Félix Houphouët-Boigny

Félix Houphouët-Boigny

Félix Houphouët-Boigny , affectionately called Papa Houphouët or Le Vieux, was the first President of Côte d'Ivoire. Originally a village chief, he worked as a doctor, an administrator of a plantation, and a union leader, before being elected to the French Parliament and serving in a number of...

and others, he formed the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (RDA) in 1946 and, in 1947, the Parti Progressiste Africain. On 21 November 1945, Tchicaya became one of the first African leaders elected to the French parliament, giving him great prestige in his native country.

Although Tchicaya was on the left of the French political spectrum, he never strongly questioned French colonial rule. This resulted in a loss of influence as the Congo prepared for independence, influenced by nationalist anti-colonial leaders as Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah was the leader of Ghana and its predecessor state, the Gold Coast, from 1952 to 1966. Overseeing the nation's independence from British colonial rule in 1957, Nkrumah was the first President of Ghana and the first Prime Minister of Ghana...

from Ghana

Ghana

Ghana , officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country located in West Africa. It is bordered by Côte d'Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, Togo to the east, and the Gulf of Guinea to the south...

and Egyptian President

President of Egypt

The President of the Arab Republic of Egypt is the head of state of Egypt.Under the Constitution of Egypt, the president is also the supreme commander of the armed forces and head of the executive branch of the Egyptian government....

Gamel Abdel Nasser. Only by aligning him with his erstwhile enemy, the more radical Jacques Opangault

Jacques Opangault

Jacques Opangault was a Congolese politician. The founder of the Mouvement Socialiste Africain , he competed with Félix Tchicaya's Parti Progressiste Congolais during two-party rule in Congo during the 1950s. He served as the first colonial prime minister of the Republic of the Congo...

in the parliamentary elections of March 31, 1957 could he continue to play a leading role in Congolese political life.

Prior to independence, the French establishment and Catholic Church feared Opangault's radicalism and favoured the rise of Fulbert Youlou

Fulbert Youlou

Abbé Fulbert Youlou was a Brazzaville-Congolese Roman Catholic priest, nationalist leader and politician.-Early life:...

, a former priest. The defection of Georges Yambot from the African Socialist Movement

African Socialist Movement

African Socialist Movement was a political party in French West Africa. The MSA was formed following a meeting of the Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière federations of Cameroon, Chad, the Republic of the Congo, French Sudan , Gabon, Guinea, Niger, Oubangui-Chari , and Senegal; the...

(MSA) to Youlou's Union Démocratique pour la Défense d'Intérêts Africains (UDDIA) helped Youlou become Prime Minister in 1958. This led to the establishment of the Republic of Congo on 28 November 1958 (with Brazzaville

Brazzaville

-Transport:The city is home to Maya-Maya Airport and a railway station on the Congo-Ocean Railway. It is also an important river port, with ferries sailing to Kinshasa and to Bangui via Impfondo...

replacing Point Noire as the country's capital).

On 16 February 1959, a revolt organised by Opangault and his MSA erupted in clashes along tribal lines between Southerners, supporting Youlou, and people from the North, loyal to the MSA. The riots were suppressed by French army and Opangault was arrested. In total about 200 people died. Prime Minister Youlou then held the elections for which Opangault had previously asked in vain. After the May 9 arrest of several politicians, including veteran politician Simon Kikhounga Ngot, because of an alleged communist plot, parliamentary elections were convincingly won by Youlou, who led the country to full independence from France on 15 August 1960.

In November that year, Youlou released Opangault, Ngot and other adversaries, as part of an amnesty. In return both politicians, as well as Germain Bicoumat, joined Youlou's government and received ministerial posts, effectively destroying any organized political opposition.

Oil

Shortly before gaining independence an event occurred that in the years to come would have deep influence on the country and its relations with the outside world, mainly France. In 1957 near Pointe Indienne the French Societé des Pétroles de l'Afrique Equatoriale Françaises (SPAEF) found oilOil

An oil is any substance that is liquid at ambient temperatures and does not mix with water but may mix with other oils and organic solvents. This general definition includes vegetable oils, volatile essential oils, petrochemical oils, and synthetic oils....

and gas

Gas

Gas is one of the three classical states of matter . Near absolute zero, a substance exists as a solid. As heat is added to this substance it melts into a liquid at its melting point , boils into a gas at its boiling point, and if heated high enough would enter a plasma state in which the electrons...

reserves offshore in sufficient exploitable quantities. Although French geologists already in 1926 established for certain the presence of oil and gas in the country only then France started exploiting these reserves. The reason was that in Algeria

Algeria

Algeria , officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria , also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa with Algiers as its capital.In terms of land area, it is the largest country in Africa and the Arab...

a war of independence was fought the French were losing. And Algeria until then was the main source of oil and gas destined for the French market. To remain independent of the American and British oil majors France had to look elsewhere for its supply. For some the discovery of oil of the Congolese coast was a blessing. For the majority of the local population it rather proved to be a curse as the International Monetary Fund

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund is an organization of 187 countries, working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world...

in its yearly reports on the country a few years ago sadly observed.

Les Trois Glorieuses and the 1968 Coup d'état

As Brazzaville had been the capital of the large federation of French Equatorial AfricaFrench Equatorial Africa

French Equatorial Africa or the AEF was the federation of French colonial possessions in Middle Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River to the Sahara Desert.-History:...

, it had an important workforce and lots of trade unions. Further radicalisation elsewhere in Africa as a result of the decolonization led to revolt against the dictatorial rule of Youlou. Following Youlou's 6 August 1960 announcement of the formation of a one-party state with only one legal trade union, trade unions started their revolt on the 13th of August. Youlou's palace was besieged on the 15th by angry workers and the French refused to intervene militarily, and he was forced to resign. This uprising is known as Les Trois Glorieuses

Les Trois Glorieuses

Les Trois Glorieuses was the anthem of the People's Republic of the Congo from January 1, 1970 through 1991 from December 13, 2011 when the original anthem, La Congolaise was restored....

(the Three Glorious Days), named after the French July Revolution

July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution or in French, saw the overthrow of King Charles X of France, the French Bourbon monarch, and the ascent of his cousin Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, who himself, after 18 precarious years on the throne, would in turn be overthrown...

against King Charles X in 1830. Fulbert Youlou and his main supporters were arrested by the military and ceased to play any further role in Congolese political life.

The Congolese military took charge of the country briefly and installed a civilian provisional government headed by Alphonse Massamba-Débat. Under the 1963 constitution

Constitution of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Constitution of the Democratic Republic of the Congo is the basic law governing the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Constitution has been changed and/or replaced several times since its independence in 1960.- Current Constitution :...

, Massamba-Débat was elected President for a 5-year term and named Pascal Lissouba

Pascal Lissouba

Pascal Lissouba was the first democratically elected President of the Republic of the Congo from August 31, 1992 to October 15, 1997. He was overthrown by the current President Denis Sassou Nguesso in the 1997 civil war....

to serve as Prime Minister.

President Massamba-Débat's term ended in August 1968 when Captain Marien Ngouabi

Marien Ngouabi

Marien Ngouabi was the military President of the Republic of the Congo from January 1, 1969 to March 18, 1977.-Origins:...

and other army officers toppled the government in a coup. After a period of consolidation under the newly formed National Revolutionary Council, Ngouabi assumed the presidency on December 31, 1968. One year later, President Ngouabi proclaimed the People's Republic of the Congo

People's Republic of the Congo

The People's Republic of the Congo was a self-declared Marxist-Leninist socialist state that was established in 1970 in the Republic of the Congo...

, Africa's first People's Republic

People's Republic

People's Republic is a title that has often been used by Marxist-Leninist governments to describe their state. The motivation for using this term lies in the claim that Marxist-Leninists govern in accordance with the interests of the vast majority of the people, and, as such, a Marxist-Leninist...

and announced the decision of the National Revolutionary Movement to change its name to the Congolese Party of Labour

Congolese Party of Labour

The Congolese Party of Labour , founded in 1969 by Marien Ngouabi, is the ruling political party of the Republic of the Congo...

(PCT).

Assassination of Ngouabi and election of Sassou-Nguesso

On March 18, 1977 President Ngouabi was assassinated. A number of people were accused of shooting Ngouabi tried and some of them executed, including former President Alphonse Massemba-DébatAlphonse Massemba-Débat

Alphonse Massamba-Debat was a political figure of the Republic of the Congo who led the country from 1963 until 1968....

, but there was little evidence to prove their involvement, and the motive behind the assassination remains unclear.

An 11-member Military Committee of the Party (CMP) was named to head an interim government with Col. (later Gen.) Joachim Yhombi-Opango

Joachim Yhombi-Opango

Jacques Joachim Yhombi Opango is a Congolese politician. He was an army officer who became Congo-Brazzaville's first general and served as Head of State of Congo-Brazzaville from 1977 to 1979. He is currently the President of the Rally for Democracy and Development , a political party, and served...

to serve as President of the Republic. After two years in power, Yhombi-Opango was accused of corruption and deviation from party directives, and removed from office on February 5, 1979, by the Central Committee of the PCT, which then simultaneously designated Vice President and Defense Minister Col. Denis Sassou-Nguesso as interim President.

The Central Committee directed Sassou-Nguesso to take charge of preparations for the Third Extraordinary Congress of the PCT, which proceeded to elect him President of the Central Committee and President of the Republic. Under a congressional resolution, Yhombi-Opango was stripped of all powers, rank, and possessions and placed under arrest to await trial for high treason. He was released from house arrest in late 1984 and ordered back to his native village of Owando

Owando

Owando is a town in the central Republic of the Congo, lying on the Kouyou River. It is the capital of Cuvette Department and an autonomous commune...

.

Democracy and civil war

After decades of turbulent politics bolstered by Marxist-Leninist rhetoric, and with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Congolese gradually moderated their economic and political views to the point that, in 1992, Congo completed a transition to multi-party democracy. Ending a long history of one-party Marxist rule, a specific agenda for this transition was laid out during Congo's national conference of 1991 and culminated in August 1992 with multi-party parliamentaryRepublic of the Congo parliamentary election, 1992

Parliamentary elections were held in the Republic of the Congo in 1992, along with a presidential election, marking the end of the transition to multiparty politics. The election was held in two rounds, the first on 24 June 1992 and the second on 19 July 1992...

and presidential elections

Republic of the Congo presidential election, 1992

Presidential elections were held in the Republic of the Congo in August 1992, marking the end of the transitional period that began with the February–June 1991 National Conference...

. Sassou Nguesso conceded defeat and Congo's new president, Professor Pascal Lissouba

Pascal Lissouba

Pascal Lissouba was the first democratically elected President of the Republic of the Congo from August 31, 1992 to October 15, 1997. He was overthrown by the current President Denis Sassou Nguesso in the 1997 civil war....

, was inaugurated on August 31, 1992.

Congolese democracy experienced severe trials in 1993 and early 1994. The President dissolved the National Assembly

National Assembly of the Republic of the Congo

The Parliament of the Republic of Congo has two chambers. The lower house is the National Assembly . It has 153 members, for a five year term in single-seat constituencies.-See also:...

in November 1992, calling for new elections in May 1993

Republic of the Congo parliamentary election, 1993

Parliamentary elections were held in the Republic of the Congo on 2 May 1993, with a second round in several constituencies on 6 June. The result was a victory for the Presidential Tendency coalition, which won 65 of the 125 seats in the National Assembly....

. The results of those elections were disputed, touching off violent civil unrest in June and again in November. In February 1994 the decisions of an international board of arbiters were accepted by all parties, and the risk of large-scale insurrection subsided.

Mr. Lissouba lost favour with the French government early in his presidency by asking the American-owned Occidental Petroleum

Occidental Petroleum

Occidental Petroleum Corporation is a California-based oil and gas exploration and production company with operations in the United States, the Middle East, North Africa, and South America...

company to provide financial support for his Government in exchange for promises of future oil production. As the French company Elf Aquitaine

Elf Aquitaine

Elf Aquitaine was a French oil company which merged with TotalFina to form TotalFinaElf. The new company changed its name to Total in 2003...

(which reaped much of its profits from the Republic of the Congo) had only just recently opened a large deep-water oil platform

Oil platform

An oil platform, also referred to as an offshore platform or, somewhat incorrectly, oil rig, is a lаrge structure with facilities to drill wells, to extract and process oil and natural gas, and to temporarily store product until it can be brought to shore for refining and marketing...

off the coast of Pointe-Noire

Pointe-Noire

Pointe-Noire is the second largest city in the Republic of the Congo, following the capital of Brazzaville, and an autonomous department since 2004. Before this date it was the capital of the Kouilou region . It is situated on a headland between Pointe-Noire Bay and the Atlantic Ocean...

. Mr. Lissouba was pressured by the French into canceling all contracts with Occidental Petroleum, but suspicions of Lissouba remained.

However, Congo's democratic progress derailed in 1997. As presidential elections scheduled for July 1997 approached, tensions between the Lissouba and Sassou Nguesso camps mounted. In May, a visit by Sassou Nguesso to Owando

Owando

Owando is a town in the central Republic of the Congo, lying on the Kouyou River. It is the capital of Cuvette Department and an autonomous commune...

, Joachim Yhombi-Opango

Joachim Yhombi-Opango

Jacques Joachim Yhombi Opango is a Congolese politician. He was an army officer who became Congo-Brazzaville's first general and served as Head of State of Congo-Brazzaville from 1977 to 1979. He is currently the President of the Rally for Democracy and Development , a political party, and served...

's political stronghold, led to the outbreak of violence between their supporters. On June 5, 1997, government forces surrounded Sassou Nguesso's home in the Mpila section of Brazzaville

Brazzaville

-Transport:The city is home to Maya-Maya Airport and a railway station on the Congo-Ocean Railway. It is also an important river port, with ferries sailing to Kinshasa and to Bangui via Impfondo...

, attempting to arrest two men, Pierre Aboya and Engobo Bonaventure, who had been implicated in the earlier violence. Fighting broke out between the government forces and Sassou Nguesso's fighters, called Cobras, igniting a 4-month conflict that destroyed or damaged much of Brazzaville.

Lissouba traveled throughout southern

Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost region of the African continent, variably defined by geography or geopolitics. Within the region are numerous territories, including the Republic of South Africa ; nowadays, the simpler term South Africa is generally reserved for the country in English.-UN...

and central Africa

Central Africa

Central Africa is a core region of the African continent which includes Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda....

in September, asking the governments of Rwanda

Rwanda

Rwanda or , officially the Republic of Rwanda , is a country in central and eastern Africa with a population of approximately 11.4 million . Rwanda is located a few degrees south of the Equator, and is bordered by Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo...

, Uganda

Uganda

Uganda , officially the Republic of Uganda, is a landlocked country in East Africa. Uganda is also known as the "Pearl of Africa". It is bordered on the east by Kenya, on the north by South Sudan, on the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the southwest by Rwanda, and on the south by...

, and Namibia

Namibia

Namibia, officially the Republic of Namibia , is a country in southern Africa whose western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and east. It gained independence from South Africa on 21 March...

for assistance. Laurent Kabila, the new-President of the Democratic Republic of Congo, sent hundreds of troops into Brazzaville to fight on Lissouba's behalf. Angola supported Sassou Nguesso with about 1,000 Angolan tanks, troops. Support by the sympathetic French government further bolstered Sassou Nguesso's rebels.

Together these forces took Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire in the morning of October 16. Lissouba fled the capital while his soldiers surrendered and citizens began looting. Yhombi-Opango supported Lissouba during the war, serving as leader of the Presidential Majority, and after Sassou Nguesso's victory he fled into exile in Côte d'Ivoire

Côte d'Ivoire

The Republic of Côte d'Ivoire or Ivory Coast is a country in West Africa. It has an area of , and borders the countries Liberia, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso and Ghana; its southern boundary is along the Gulf of Guinea. The country's population was 15,366,672 in 1998 and was estimated to be...

and France. Soon thereafter, Sassou Nguesso declared himself President and named a 33-member government.

In January 1998 the Sassou Nguesso regime held a National Forum for Reconciliation to determine the nature and duration of the transition period. The Forum, tightly controlled by the government, decided elections should be held in about 3 years, elected a transition advisory legislature, and announced that a constitutional convention will finalize a draft constitution. However, the eruption in late 1998 of fighting between Sassou Nguesso's government forces and an armed opposition disrupted the transitional return to democracy. This new violence also closed the economically vital Congo-Ocean Railway

Congo-Ocean Railway

The Congo–Ocean Railway links the Atlantic port of Pointe-Noire with Brazzaville, a distance of 502 kilometres...

, caused great destruction and loss of life in southern Brazzaville and in the Pool, Bouenza, and Niari regions, and displaced hundreds of thousands of persons.

In November and December 1999, the government signed agreements with representatives of many, though not all, of the rebel groups. The December accord, mediated by President Omar Bongo

Omar Bongo

El Hadj Omar Bongo Ondimba , born as Albert-Bernard Bongo, was a Gabonese politician who was President of Gabon for 42 years from 1967 until his death in office in 2009....

of Gabon

Gabon

Gabon , officially the Gabonese Republic is a state in west central Africa sharing borders with Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north, and with the Republic of the Congo curving around the east and south. The Gulf of Guinea, an arm of the Atlantic Ocean is to the west...

, called for follow-on, inclusive political negotiations between the government and the opposition.

2000s

Sassou won elections in 2002 with an implausible 90% or so of the votes. His two main rivals, Lissouba and Bernard KolelasBernard Kolélas

Bernard Bakana Kolélas was a Congolese politician and President of the Congolese Movement for Democracy and Integral Development...

, were prevented from competing and the only remaining credible rival, André Milongo

André Milongo

André Ntsatouabantou Milongo was a Congolese politician who served as Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo from June 1991 to August 1992. He was chosen by the 1991 National Conference to lead the country during its transition to multiparty elections, which were held in 1992...

, boycotted the elections and withdrew from the race due to, among other reasons, perceived voter fraud on the part of Sassou. A new constitution

Constitution

A constitution is a set of fundamental principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization is governed. These rules together make up, i.e. constitute, what the entity is...

was agreed upon in January 2002, granting the president new powers and extending his term to seven years as well as introducing a new bicameral assembly.

On December 30, twenty opposition political parties issued a statement through spokesman Chistope Ngokaka, saying Sassou's government had purchased "weapons and military craft... under contracts signed between the officials in Brazzaville and the government in Beijing

Beijing

Beijing , also known as Peking , is the capital of the People's Republic of China and one of the most populous cities in the world, with a population of 19,612,368 as of 2010. The city is the country's political, cultural, and educational center, and home to the headquarters for most of China's...

."

Congo's next presidential election is set for July 2009. Five candidates have formally announced their intention to run in the election and President Sassou is expected to run for another term.

See also

- History of AfricaHistory of AfricaThe history of Africa begins with the prehistory of Africa and the emergence of Homo sapiens in East Africa, continuing into the present as a patchwork of diverse and politically developing nation states. Agriculture began about 10,000 BCE and metallurgy in about 4000 BCE. The history of early...

- People's Republic of the CongoPeople's Republic of the CongoThe People's Republic of the Congo was a self-declared Marxist-Leninist socialist state that was established in 1970 in the Republic of the Congo...

- Politics of the Republic of the CongoPolitics of the Republic of the CongoPolitics of the Republic of the Congo takes place in a framework of a presidential republic, whereby the President is both head of state and head of government, and of a pluriform multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government...

- List of heads of government of the Republic of the Congo

- List of heads of state of the Republic of the Congo