John Stapp

Encyclopedia

John Paul Stapp, M.D., Ph.D., Colonel, USAF (Ret.) (11 July 1910–13 November 1999) was a career U.S. Air Force officer, USAF flight surgeon

and pioneer in studying the effects of acceleration and deceleration forces on humans. He was a colleague and contemporary of Chuck Yeager

, and became known as "the fastest man on earth".

, Brazil

, the son of Reverend and Mrs. Charles F. Stapp.

His preliminary education was at the Brownwood High School, Brownwood, Texas

, and San Marcos Academy, San Marcos, Texas

. Stapp received a bachelor's degree in 1931 from Baylor University

, Waco, Texas

, a MA

from Baylor in 1932, a PhD

in Biophysics

from the University of Texas at Austin

in 1940, and an MD

from the University of Minnesota

, Twin Cities

, in 1944. He interned for one year at St. Mary's Hospital in Duluth, Minnesota

. Stapp also received an honorary

Doctor of Science

from Baylor University.

Stapp entered the Army Air Corps

Stapp entered the Army Air Corps

on 5 October 1944. On 10 August 1946, he was transferred to the Aero Medical Laboratory at Wright Field

as project officer and medical consultant in the Biophysics Branch. His first assignment as a project officer included a series of flights testing various oxygen

systems in unpressurized aircraft at 40,000 ft

(12.2 km). One of the stickiest problems with high-altitude flight was the danger of "the bends" or decompression sickness

. Stapp's work resolved that problem and a host of others that led to the next generation of high-altitude aircraft, as well as HALO insertion techniques. He was assigned to the deceleration project in March 1947.

In 1967, the Air Force loaned Stapp to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

to conduct auto-safety research. Dr. Stapp retired from the US Air Force with the rank of colonel in 1970.

As far back as 1945, service personnel realized the need for a comprehensive and controlled series of studies leading to fundamental concepts that could be applied to better safeguard aircraft occupants during a crash. The initial phase of the program, as set up by the Aero Medical Laboratory of the Wright Air Development Center, was to develop equipment and instrumentation whereby aircraft crashes might be simulated, and to study the strength factors of seats and harnesses, and human tolerance to the deceleration encountered in simulated aircraft crashes.

As far back as 1945, service personnel realized the need for a comprehensive and controlled series of studies leading to fundamental concepts that could be applied to better safeguard aircraft occupants during a crash. The initial phase of the program, as set up by the Aero Medical Laboratory of the Wright Air Development Center, was to develop equipment and instrumentation whereby aircraft crashes might be simulated, and to study the strength factors of seats and harnesses, and human tolerance to the deceleration encountered in simulated aircraft crashes.

When he began his research in 1947, the aerospace

conventional wisdom

was that a man would suffer fatally around 18 g. Stapp shattered this barrier in the process of his progressive work, experiencing more "peak" g-forces voluntarily than any other human. Stapp suffered repeated and various injuries including broken limbs, ribs, detached retina

, and miscellaneous traumas which eventually resulted in lifelong lingering vision problems caused by permanently burst blood vessels in his eyes. In one of his final rocket-propelled rides, Stapp was subjected to 46.2 times the force of gravity. The aeronautical design changes this fundamental research wrought are widespread and hard to quantify, but fundamentally important.

The crash survival research program was originally slated to be conducted near the Aero Medical Laboratory, but Muroc Army Air Field

(now Edwards AFB) was chosen because of the presence of a 2,000-foot (610-m) track, built originally for V-1 rocket research. That particular program had been completed and was taken over by the deceleration research program.

Designed to Aero Medical Laboratory specifications and fabricated by Northrop Aircraft

of Hawthorne, California

, equipment was maintained and operated on service contract by the Northrop Company.

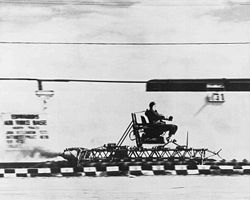

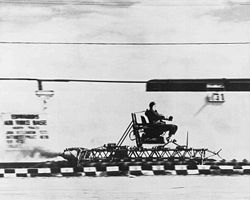

The "human decelerator" (dubbed the "Gee Whiz" by the scientists) consisted of a 1,500-pound (680-kg) carriage mounted on a 2,000-foot (610-m) standard gauge railroad track supported on a heavy concrete bed, and a 45-foot (14-m) hydraulic braking system believed to be one of the most powerful ever constructed. Four slippers secured the carriage to the rails while permitting it to slide freely. At the rear of the carriage, 1,000-lbf (4-kN) rockets provided the propelling force. Braking was accomplished by partitioned bins of water and scoops that picked up the water and threw it forward. By varying the number and pattern of brake buckets used and the number of carriage-propelling rockets, it was possible to control the deceleration.

The first run on the rocket sled

took place on 30 April 1947 with ballast. The sled ran off the tracks. The first human run took place the following December. Instrumentation on all of the early runs was in the developmental stage, and it was not until August 1948 that it was adequate to begin recording. By August 1948, 16 human runs had been made, all in the backward facing position. Forward facing runs were started in August 1949. Most of the earlier tests were run to compare the standard Air Force harnesses with a series of modified harnesses, to determine which type gave the best protection to the pilot.

By 8 June 1951, a total of 74 human runs had been made on the decelerator, 19 with the subjects in the backward position, and 55 in the forward position. Stapp, one of the most frequent volunteers on the runs, sustained a fracture of his right wrist during the runs on two separate occasions.

Stapp's research on the decelerator had profound implications for both civilian and military aviation. For instance, the backward-facing seat concept, which was known previously, was given great impetus by the officer's crash research program, which proved beyond a doubt that this position was the safest for aircraft passengers and required little harness support, and that a human can withstand much greater deceleration than in the forward position. As a result, many Military Air Transport Service

(MATS) aircraft in USAF were equipped or retrofitted with this type of seat. Commercial airlines were made aware of these findings, but still use mostly forward-facing seats. The British Royal Air Force

also installed it on many of their military transport aircraft.

As a result of Stapp's findings, the acceleration requirement for fighter seats was increased considerably up to 32 g

(310 m/s²) since his work showed that a pilot could walk away from crashes when properly protected by harnesses if the seat does not break loose.

The "side saddle" or sideways-facing harness was also developed by Stapp. The new triangular-shaped harness gave vastly increased protection to fully equipped paratroopers sitting side by side in Air Force aircraft. It was made of nylon

mesh webbing, fit snugly over the shoulder facing the forward part of the aircraft, and protected the wearer from the force of crash impacts, takeoffs and landing bumps. It withstood a crash force of approximately 8,000 pounds of force (36 kN) at 32 g (310 m/s²) and was developed to replace the old-fashioned lap belts which gave inadequate protection to their wearers.

By riding the decelerator sled himself, Stapp demonstrated that a human can withstand at least 45 g (440 m/s²) in the forward position, with adequate harness. This is the highest known acceleration voluntarily encountered by a human. Stapp believed that the tolerance of humans to acceleration had not yet been reached in tests, and is much greater than ordinarily thought possible.

Also developed by Stapp as an added safety measure was an improved version of the currently used shoulder strap and lap belt. The new high-strength harness withstood 45.4 g (445 m/s²), compared to the 17 g (167 m/s²), which was the limit that could be tolerated with the old combination. Basically, the new pilot harness added an inverted "V" strap crossing the pilot's thighs added to the standard lap belt and shoulder straps. The leg and shoulder straps and the lap belt all fastened together at one point, and pressure was distributed evenly over the stronger body surfaces, hips, thighs and shoulders, rather than on the solar plexus, as was the case with the old harness.

Stapp became interested in the implications of his work for car safety

. At the time, cars were generally not fitted with seatbelts but Stapp had shown that a properly restrained human could survive far greater impacts than an unrestrained one. Many traffic accident deaths were therefore avoidable but for the lack of seatbelts. Stapp became a strong advocate and publicist for this cause, frequently steering interviews onto the subject, organizing conferences, and staging demonstrations (including the first known use of automobile crash test dummies

). At one point the military objected to funding work they believed was outside their purview, but they were persuaded when Stapp gave them statistics showing that more Air Force pilots were killed in traffic accidents than in plane crashes. The culmination of his efforts came in 1966 when Stapp witnessed Lyndon B. Johnson

sign the law making manufacture of cars with seatbelts (lapbelts at that time) compulsory.

. Stapp was its popularizer and probably framed its final form, first using the soon to be widespread term in his first press conference about Project MX981 in the phrase, "We do all of our work in consideration of Murphy's Law" in a nonchalant answer to a reporter. It was his team that, within an adaged-filled subculture, and while using a new device developed by reliability engineering

expert Major Edward Murphy

, coined the euphemistic phrase and began to use it in the months prior to that press conference. When the unfamiliar "Law" was clarified by a subsequent follow-up question, it soon burst into the press in various diverse publications, and got picked up by commentators and talk programs.

Stapp is credited with creating Stapp's Law (or Stapp's Ironic Paradox) during his work on the project. It states "The universal aptitude for ineptitude makes any human accomplishment an incredible miracle".

's Elliott Cresson Medal

.

In 1979 Stapp was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame

. The New Mexico Museum of Space History, which houses the International Space Hall of Fame, includes a John P. Stapp Air & Space Park which holds Sonic Wind No. 1, a rocket sled ridden by Stapp.

In 1985, Stapp was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame for his work in aviation safety.

In 1991, Stapp was awarded the National Medal of Technology

, "for his research on the effects of mechanical force on living tissues leading to safety developments in crash protection technology".

, as well as chairman of the annual Stapp Car Crash Conference. This event meets to study car crashes and determine ways to make cars safer. In addition, Stapp was honorary chairman of the Stapp Foundation, which is underwritten by General Motors

and provides scholarships for automotive engineering students.

Stapp died peacefully at his home in Alamogordo at the age of 89, a remarkable show of longevity considering the extreme forces his body was subject to during his many years of research.

s, and he would work them into press-conference answers over many years and many press conferences. When President Johnson

signed the mandatory seat-belt bill into law in 1966, and consumer advocate Ralph Nader

stood by his side, much of the decades-long underlying popularization ground work and its supporting research had been laid by J.P. Stapp, who also stood in the room that day only a short distance away.

Flight surgeon

A flight surgeon is a military medical officer assigned to duties in the clinical field variously known as aviation medicine, aerospace medicine, or flight medicine...

and pioneer in studying the effects of acceleration and deceleration forces on humans. He was a colleague and contemporary of Chuck Yeager

Chuck Yeager

Charles Elwood "Chuck" Yeager is a retired major general in the United States Air Force and noted test pilot. He was the first pilot to travel faster than sound...

, and became known as "the fastest man on earth".

Early years

John Paul Stapp was born in BahiaBahia

Bahia is one of the 26 states of Brazil, and is located in the northeastern part of the country on the Atlantic coast. It is the fourth most populous Brazilian state after São Paulo, Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro, and the fifth-largest in size...

, Brazil

Brazil

Brazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

, the son of Reverend and Mrs. Charles F. Stapp.

His preliminary education was at the Brownwood High School, Brownwood, Texas

Brownwood, Texas

Brownwood is a city in and the county seat of Brown County, Texas, United States. The population was 18,813 at the 2000 census.-History:The original site of the Brown County seat of Brownwood was on the east of Pecan Bayou. A dispute arose over land and water rights, and the settlers were forced...

, and San Marcos Academy, San Marcos, Texas

San Marcos, Texas

San Marcos is a city in the U.S. state of Texas, and is the seat of Hays County. Located within the metropolitan area, the city is located on the Interstate 35 corridor—between Austin and San Antonio....

. Stapp received a bachelor's degree in 1931 from Baylor University

Baylor University

Baylor University is a private, Christian university located in Waco, Texas. Founded in 1845, Baylor is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.-History:...

, Waco, Texas

Waco, Texas

Waco is a city in and the county seat of McLennan County, Texas. Situated along the Brazos River and on the I-35 corridor, halfway between Dallas and Austin, it is the economic, cultural, and academic center of the 'Heart of Texas' region....

, a MA

Master of Arts (postgraduate)

A Master of Arts from the Latin Magister Artium, is a type of Master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The M.A. is usually contrasted with the M.S. or M.Sc. degrees...

from Baylor in 1932, a PhD

PHD

PHD may refer to:*Ph.D., a doctorate of philosophy*Ph.D. , a 1980s British group*PHD finger, a protein sequence*PHD Mountain Software, an outdoor clothing and equipment company*PhD Docbook renderer, an XML renderer...

in Biophysics

Biophysics

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that uses the methods of physical science to study biological systems. Studies included under the branches of biophysics span all levels of biological organization, from the molecular scale to whole organisms and ecosystems...

from the University of Texas at Austin

University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin is a state research university located in Austin, Texas, USA, and is the flagship institution of the The University of Texas System. Founded in 1883, its campus is located approximately from the Texas State Capitol in Austin...

in 1940, and an MD

Doctor of Medicine

Doctor of Medicine is a doctoral degree for physicians. The degree is granted by medical schools...

from the University of Minnesota

University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, Twin Cities is a public research university located in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, United States. It is the oldest and largest part of the University of Minnesota system and has the fourth-largest main campus student body in the United States, with 52,557...

, Twin Cities

Twin cities

Twin cities are a special case of two cities or urban centres which are founded in close geographic proximity and then grow into each other over time...

, in 1944. He interned for one year at St. Mary's Hospital in Duluth, Minnesota

Duluth, Minnesota

Duluth is a port city in the U.S. state of Minnesota and is the county seat of Saint Louis County. The fourth largest city in Minnesota, Duluth had a total population of 86,265 in the 2010 census. Duluth is also the second largest city that is located on Lake Superior after Thunder Bay, Ontario,...

. Stapp also received an honorary

Honorary degree

An honorary degree or a degree honoris causa is an academic degree for which a university has waived the usual requirements, such as matriculation, residence, study, and the passing of examinations...

Doctor of Science

Doctor of Science

Doctor of Science , usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D. or Dr.Sc., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries Doctor of Science is the name used for the standard doctorate in the sciences, elsewhere the Sc.D...

from Baylor University.

Military career

United States Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps was a forerunner of the United States Air Force. Renamed from the Air Service on 2 July 1926, it was part of the United States Army and the predecessor of the United States Army Air Forces , established in 1941...

on 5 October 1944. On 10 August 1946, he was transferred to the Aero Medical Laboratory at Wright Field

Wright-Patterson Air Force Base

Wright-Patterson Air Force Base is a United States Air Force base in Greene and Montgomery counties in the state of Ohio. It includes both Wright and Patterson Fields, which were originally Wilbur Wright Field and Fairfield Aviation General Supply Depot. Patterson Field is located approximately...

as project officer and medical consultant in the Biophysics Branch. His first assignment as a project officer included a series of flights testing various oxygen

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

systems in unpressurized aircraft at 40,000 ft

Ft

Ft or ft. may mean:* Foot , a unit of distance or length* Hungarian forint, the currency of Hungary* Fair Trade, the principle to give a fair price when trading* Fort, a fortified place, especially in place names...

(12.2 km). One of the stickiest problems with high-altitude flight was the danger of "the bends" or decompression sickness

Decompression sickness

Decompression sickness describes a condition arising from dissolved gases coming out of solution into bubbles inside the body on depressurization...

. Stapp's work resolved that problem and a host of others that led to the next generation of high-altitude aircraft, as well as HALO insertion techniques. He was assigned to the deceleration project in March 1947.

In 1967, the Air Force loaned Stapp to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration is an agency of the Executive Branch of the U.S. government, part of the Department of Transportation...

to conduct auto-safety research. Dr. Stapp retired from the US Air Force with the rank of colonel in 1970.

Works on effects of deceleration

When he began his research in 1947, the aerospace

Aerospace

Aerospace comprises the atmosphere of Earth and surrounding space. Typically the term is used to refer to the industry that researches, designs, manufactures, operates, and maintains vehicles moving through air and space...

conventional wisdom

Conventional wisdom

Conventional wisdom is a term used to describe ideas or explanations that are generally accepted as true by the public or by experts in a field. Such ideas or explanations, though widely held, are unexamined. Unqualified societal discourse preserves the status quo. It codifies existing social...

was that a man would suffer fatally around 18 g. Stapp shattered this barrier in the process of his progressive work, experiencing more "peak" g-forces voluntarily than any other human. Stapp suffered repeated and various injuries including broken limbs, ribs, detached retina

Retinal detachment

Retinal detachment is a disorder of the eye in which the retina peels away from its underlying layer of support tissue. Initial detachment may be localized, but without rapid treatment the entire retina may detach, leading to vision loss and blindness. It is a medical emergency.The retina is a...

, and miscellaneous traumas which eventually resulted in lifelong lingering vision problems caused by permanently burst blood vessels in his eyes. In one of his final rocket-propelled rides, Stapp was subjected to 46.2 times the force of gravity. The aeronautical design changes this fundamental research wrought are widespread and hard to quantify, but fundamentally important.

The crash survival research program was originally slated to be conducted near the Aero Medical Laboratory, but Muroc Army Air Field

Edwards Air Force Base

Edwards Air Force Base is a United States Air Force base located on the border of Kern County, Los Angeles County, and San Bernardino County, California, in the Antelope Valley. It is southwest of the central business district of North Edwards, California and due east of Rosamond.It is named in...

(now Edwards AFB) was chosen because of the presence of a 2,000-foot (610-m) track, built originally for V-1 rocket research. That particular program had been completed and was taken over by the deceleration research program.

Designed to Aero Medical Laboratory specifications and fabricated by Northrop Aircraft

Northrop Corporation

Northrop Corporation was a leading United States aircraft manufacturer from its formation in 1939 until its merger with Grumman to form Northrop Grumman in 1994. The company is known for its development of the flying wing design, although only a few of these have entered service.-History:Jack...

of Hawthorne, California

Hawthorne, California

Hawthorne is a city in southwestern Los Angeles County, California. The city at the 2010 census had a population of 84,293, up from 84,112 at the 2000 census.-Geography:...

, equipment was maintained and operated on service contract by the Northrop Company.

The "human decelerator" (dubbed the "Gee Whiz" by the scientists) consisted of a 1,500-pound (680-kg) carriage mounted on a 2,000-foot (610-m) standard gauge railroad track supported on a heavy concrete bed, and a 45-foot (14-m) hydraulic braking system believed to be one of the most powerful ever constructed. Four slippers secured the carriage to the rails while permitting it to slide freely. At the rear of the carriage, 1,000-lbf (4-kN) rockets provided the propelling force. Braking was accomplished by partitioned bins of water and scoops that picked up the water and threw it forward. By varying the number and pattern of brake buckets used and the number of carriage-propelling rockets, it was possible to control the deceleration.

The first run on the rocket sled

Rocket sled

A rocket sled is a test platform that slides along a set of rails, propelled by rockets.As its name implies, a rocket sled does not use wheels. Instead, it has sliding pads, called "slippers", which are curved around the head of the rails to prevent the sled from flying off the track...

took place on 30 April 1947 with ballast. The sled ran off the tracks. The first human run took place the following December. Instrumentation on all of the early runs was in the developmental stage, and it was not until August 1948 that it was adequate to begin recording. By August 1948, 16 human runs had been made, all in the backward facing position. Forward facing runs were started in August 1949. Most of the earlier tests were run to compare the standard Air Force harnesses with a series of modified harnesses, to determine which type gave the best protection to the pilot.

By 8 June 1951, a total of 74 human runs had been made on the decelerator, 19 with the subjects in the backward position, and 55 in the forward position. Stapp, one of the most frequent volunteers on the runs, sustained a fracture of his right wrist during the runs on two separate occasions.

Stapp's research on the decelerator had profound implications for both civilian and military aviation. For instance, the backward-facing seat concept, which was known previously, was given great impetus by the officer's crash research program, which proved beyond a doubt that this position was the safest for aircraft passengers and required little harness support, and that a human can withstand much greater deceleration than in the forward position. As a result, many Military Air Transport Service

Military Air Transport Service

The Military Air Transport Service is an inactive Department of Defense Unified Command. Activated on 1 June 1948, MATS was a consolidation of the United States Navy Naval Air Transport Service and the United States Air Force Air Transport Command into a single, joint, unified command...

(MATS) aircraft in USAF were equipped or retrofitted with this type of seat. Commercial airlines were made aware of these findings, but still use mostly forward-facing seats. The British Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

also installed it on many of their military transport aircraft.

As a result of Stapp's findings, the acceleration requirement for fighter seats was increased considerably up to 32 g

G-force

The g-force associated with an object is its acceleration relative to free-fall. This acceleration experienced by an object is due to the vector sum of non-gravitational forces acting on an object free to move. The accelerations that are not produced by gravity are termed proper accelerations, and...

(310 m/s²) since his work showed that a pilot could walk away from crashes when properly protected by harnesses if the seat does not break loose.

The "side saddle" or sideways-facing harness was also developed by Stapp. The new triangular-shaped harness gave vastly increased protection to fully equipped paratroopers sitting side by side in Air Force aircraft. It was made of nylon

Nylon

Nylon is a generic designation for a family of synthetic polymers known generically as polyamides, first produced on February 28, 1935, by Wallace Carothers at DuPont's research facility at the DuPont Experimental Station...

mesh webbing, fit snugly over the shoulder facing the forward part of the aircraft, and protected the wearer from the force of crash impacts, takeoffs and landing bumps. It withstood a crash force of approximately 8,000 pounds of force (36 kN) at 32 g (310 m/s²) and was developed to replace the old-fashioned lap belts which gave inadequate protection to their wearers.

By riding the decelerator sled himself, Stapp demonstrated that a human can withstand at least 45 g (440 m/s²) in the forward position, with adequate harness. This is the highest known acceleration voluntarily encountered by a human. Stapp believed that the tolerance of humans to acceleration had not yet been reached in tests, and is much greater than ordinarily thought possible.

Also developed by Stapp as an added safety measure was an improved version of the currently used shoulder strap and lap belt. The new high-strength harness withstood 45.4 g (445 m/s²), compared to the 17 g (167 m/s²), which was the limit that could be tolerated with the old combination. Basically, the new pilot harness added an inverted "V" strap crossing the pilot's thighs added to the standard lap belt and shoulder straps. The leg and shoulder straps and the lap belt all fastened together at one point, and pressure was distributed evenly over the stronger body surfaces, hips, thighs and shoulders, rather than on the solar plexus, as was the case with the old harness.

Wind-blast experiments

Stapp also participated in wind-blast experiments, in which he flew in jet aircraft at high speeds to determine whether or not it was safe for a pilot to remain with his aircraft if the canopy should accidentally blow off. Stapp stayed with his aircraft at a speed of 570 mph (917 km/h), with the canopy removed, and suffered no injurious effects from the wind blasts. Among these experiments was one of the first high altitude skydives, executed by Stapp himself. He also supervised research programs in the fields of human factors in escape from aircraft and human tolerance to abrupt acceleration and deceleration.Car safety

During his work at the Holloman Air Force BaseHolloman Air Force Base

Holloman Air Force Base is a United States Air Force base located six miles southwest of the central business district of Alamogordo, a city in Otero County, New Mexico, United States. The base was named in honor of Col. George V. Holloman, a pioneer in guided missile research...

Stapp became interested in the implications of his work for car safety

Car safety

Automobile safety is the study and practice of vehicle design, construction, and equipment to minimize the occurrence and consequences of automobile accidents. Automobile safety is the study and practice of vehicle design, construction, and equipment to minimize the occurrence and consequences of...

. At the time, cars were generally not fitted with seatbelts but Stapp had shown that a properly restrained human could survive far greater impacts than an unrestrained one. Many traffic accident deaths were therefore avoidable but for the lack of seatbelts. Stapp became a strong advocate and publicist for this cause, frequently steering interviews onto the subject, organizing conferences, and staging demonstrations (including the first known use of automobile crash test dummies

Crash test dummy

Crash test dummies are full-scale anthropomorphic test devices that simulate the dimensions, weight proportions and articulation of the human body, and are usually instrumented to record data about the dynamic behavior of the ATD in simulated vehicle impacts...

). At one point the military objected to funding work they believed was outside their purview, but they were persuaded when Stapp gave them statistics showing that more Air Force pilots were killed in traffic accidents than in plane crashes. The culmination of his efforts came in 1966 when Stapp witnessed Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson , often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States...

sign the law making manufacture of cars with seatbelts (lapbelts at that time) compulsory.

Stapp's law

Stapp was an inveterate collector of aphorisms and adages, kept a logbook of such, and the practice spread to his entire working group. He published a collection of these in 1992. Witty and charismatic and thus popular with the press and his staff, Stapp's team in particular, and its workplace subculture is also the clear originating source for the ubiquitous principle known as Murphy's lawMurphy's law

Murphy's law is an adage or epigram that is typically stated as: "Anything that can go wrong will go wrong". - History :The perceived perversity of the universe has long been a subject of comment, and precursors to the modern version of Murphy's law are not hard to find. Recent significant...

. Stapp was its popularizer and probably framed its final form, first using the soon to be widespread term in his first press conference about Project MX981 in the phrase, "We do all of our work in consideration of Murphy's Law" in a nonchalant answer to a reporter. It was his team that, within an adaged-filled subculture, and while using a new device developed by reliability engineering

Reliability engineering

Reliability engineering is an engineering field, that deals with the study, evaluation, and life-cycle management of reliability: the ability of a system or component to perform its required functions under stated conditions for a specified period of time. It is often measured as a probability of...

expert Major Edward Murphy

Major Edward A. Murphy, Jr.

Edward Aloysius Murphy, Jr. was an American aerospace engineer who worked on safety-critical systems. He is best-known for Murphy's law, which is said to state, "Anything that can go wrong will go wrong."...

, coined the euphemistic phrase and began to use it in the months prior to that press conference. When the unfamiliar "Law" was clarified by a subsequent follow-up question, it soon burst into the press in various diverse publications, and got picked up by commentators and talk programs.

Stapp is credited with creating Stapp's Law (or Stapp's Ironic Paradox) during his work on the project. It states "The universal aptitude for ineptitude makes any human accomplishment an incredible miracle".

Awards

In 1973 Stapp was awarded the Franklin InstituteFranklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and one of the oldest centers of science education and development in the United States, dating to 1824. The Institute also houses the Benjamin Franklin National Memorial.-History:On February 5, 1824, Samuel Vaughn Merrick and...

's Elliott Cresson Medal

Elliott Cresson Medal

The Elliott Cresson Medal, also known as the Elliott Cresson Gold Medal, was the highest award given by the Franklin Institute. The award was established by Elliott Cresson, life member of the Franklin Institute, with $1,000 granted in 1848...

.

In 1979 Stapp was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame

International Space Hall of Fame

The New Mexico Museum of Space History is a museum and planetarium complex in Alamogordo, New Mexico, dedicated to artifacts and displays related to space flight and the space age. It includes the International Space Hall of Fame. The Museum of Space History highlights the role that New Mexico has...

. The New Mexico Museum of Space History, which houses the International Space Hall of Fame, includes a John P. Stapp Air & Space Park which holds Sonic Wind No. 1, a rocket sled ridden by Stapp.

In 1985, Stapp was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame for his work in aviation safety.

In 1991, Stapp was awarded the National Medal of Technology

National Medal of Technology

The National Medal of Technology and Innovation is an honor granted by the President of the United States to American inventors and innovators who have made significant contributions to the development of new and important technology...

, "for his research on the effects of mechanical force on living tissues leading to safety developments in crash protection technology".

Later life

In the years before his death, Stapp was president of the New Mexico Research Institute, headquartered in Alamogordo, New MexicoAlamogordo, New Mexico

Alamogordo is the county seat of Otero County and a city in south-central New Mexico, United States. A desert community lying in the Tularosa Basin, it is bordered on the east by the Sacramento Mountains. It is the nearest city to Holloman Air Force Base. The population was 35,582 as of the 2000...

, as well as chairman of the annual Stapp Car Crash Conference. This event meets to study car crashes and determine ways to make cars safer. In addition, Stapp was honorary chairman of the Stapp Foundation, which is underwritten by General Motors

General Motors

General Motors Company , commonly known as GM, formerly incorporated as General Motors Corporation, is an American multinational automotive corporation headquartered in Detroit, Michigan and the world's second-largest automaker in 2010...

and provides scholarships for automotive engineering students.

Stapp died peacefully at his home in Alamogordo at the age of 89, a remarkable show of longevity considering the extreme forces his body was subject to during his many years of research.

Legacy

Stapp's life was dedicated to aerospace safety in particular, and safety in general; he was one of the principal advocates of automotive safety beltSeat belt

A seat belt or seatbelt, sometimes called a safety belt, is a safety harness designed to secure the occupant of a vehicle against harmful movement that may result from a collision or a sudden stop...

s, and he would work them into press-conference answers over many years and many press conferences. When President Johnson

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson , often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th President of the United States after his service as the 37th Vice President of the United States...

signed the mandatory seat-belt bill into law in 1966, and consumer advocate Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader is an American political activist, as well as an author, lecturer, and attorney. Areas of particular concern to Nader include consumer protection, humanitarianism, environmentalism, and democratic government....

stood by his side, much of the decades-long underlying popularization ground work and its supporting research had been laid by J.P. Stapp, who also stood in the room that day only a short distance away.