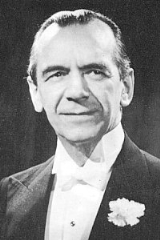

Malcolm Sargent

Encyclopedia

Ballets Russes

The Ballets Russes was an itinerant ballet company from Russia which performed between 1909 and 1929 in many countries. Directed by Sergei Diaghilev, it is regarded as the greatest ballet company of the 20th century. Many of its dancers originated from the Imperial Ballet of Saint Petersburg...

, the Royal Choral Society

Royal Choral Society

The Royal Choral Society is an amateur choir, based in London. Formed soon after the opening of the Royal Albert Hall in 1871, the choir gave its first performance as the Royal Albert Hall Choral Society on 8 May 1872 – the choir's first conductor Charles Gounod included the Hallelujah Chorus from...

, the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company was a professional light opera company that staged Gilbert and Sullivan's Savoy operas. The company performed nearly year-round in the UK and sometimes toured in Europe, North America and elsewhere, from the 1870s until it closed in 1982. It was revived in 1988 and...

, and the London Philharmonic

London Philharmonic Orchestra

The London Philharmonic Orchestra , based in London, is one of the major orchestras of the United Kingdom, and is based in the Royal Festival Hall. In addition, the LPO is the main resident orchestra of the Glyndebourne Festival Opera...

, Hallé

The Hallé

The Hallé is a symphony orchestra based in Manchester, England. It is the UK's oldest extant symphony orchestra , supports a choir, youth choir and a youth orchestra, and releases its recordings on its own record label, though it has occasionally released recordings on Angel Records and EMI...

, Liverpool Philharmonic, BBC Symphony

BBC Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Symphony Orchestra is the principal broadcast orchestra of the British Broadcasting Corporation and one of the leading orchestras in Britain.-History:...

and Royal Philharmonic

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra is a British orchestra based in London. It tours widely, and is sometimes referred to as "Britain's national orchestra"...

orchestras. Sargent was held in high esteem by choirs and instrumental soloists, but because of his high standards and a statement that he made in a 1936 interview about musicians' rights to tenure, his relationship with orchestral players was often uneasy. Despite this, he was co-founder of the London Philharmonic, was the first conductor of the Liverpool Philharmonic as a full-time ensemble, and played an important part in saving the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra from disbandment in the 1960s.

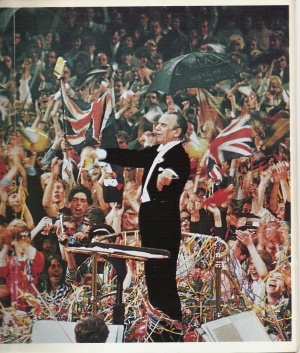

As chief conductor of London's internationally famous summer music festival the Proms

The Proms

The Proms, more formally known as The BBC Proms, or The Henry Wood Promenade Concerts presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert Hall in London...

from 1948 to 1967, Sargent was one of the best-known English conductors. When he took over the Proms from their founder, Sir Henry Wood, he and two assistants conducted the two-month season between them. By the time he died, he was assisted by a large international roster of guest conductors.

At the outbreak of World War II, Sargent turned down an offer of a major musical directorship in Australia and returned to the UK to bring music to as many people as possible as his contribution to national morale. His fame extended beyond the concert hall: to the British public, he was a familiar broadcaster in BBC

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

radio talk shows, and generations of Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan refers to the Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the librettist W. S. Gilbert and the composer Arthur Sullivan . The two men collaborated on fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which H.M.S...

devotees have known his recordings of the most popular Savoy Opera

Savoy opera

The Savoy Operas denote a style of comic opera that developed in Victorian England in the late 19th century, with W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan as the original and most successful practitioners. The name is derived from the Savoy Theatre, which impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte built to house...

s. He toured widely throughout the world and was noted for his skill as a conductor, his championship of British composers, and his debonair appearance, which won him the nickname "Flash Harry."

Life and career

Sargent was born in Bath Villas, AshfordAshford, Kent

Ashford is a town in the borough of Ashford in Kent, England. In 2005 it was voted the fourth best place to live in the United Kingdom. It lies on the Great Stour river, the M20 motorway, and the South Eastern Main Line and High Speed 1 railways. Its agricultural market is one of the most...

, in Kent

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

, England, to a working-class family. His father, Henry Sargent, was a coal merchant, amateur musician and part-time church organist; his mother, Agnes, née Hall, was the matron of a local school. Sargent was brought up in Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a town and civil parish within the South Kesteven district of the county of Lincolnshire, England. It is approximately to the north of London, on the east side of the A1 road to York and Edinburgh and on the River Welland...

, where he joined the choir at Peterborough Cathedral

Peterborough Cathedral

Peterborough Cathedral, properly the Cathedral Church of St Peter, St Paul and St Andrew – also known as Saint Peter's Cathedral in the United Kingdom – is the seat of the Bishop of Peterborough, dedicated to Saint Peter, Saint Paul and Saint Andrew, whose statues look down from the...

, studied the organ

Organ (music)

The organ , is a keyboard instrument of one or more divisions, each played with its own keyboard operated either with the hands or with the feet. The organ is a relatively old musical instrument in the Western musical tradition, dating from the time of Ctesibius of Alexandria who is credited with...

and won a scholarship to Stamford School

Stamford School

Stamford School is an English independent school situated in the market town of Stamford, Lincolnshire, England. It has been a member of the Headmasters' and Headmistresses' Conference since 1920.-History:...

. At the age of 14, he accompanied rehearsals for amateur productions of The Gondoliers

The Gondoliers

The Gondoliers; or, The King of Barataria is a Savoy Opera, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert. It premiered at the Savoy Theatre on 7 December 1889 and ran for a very successful 554 performances , closing on 30 June 1891...

and The Yeomen of the Guard

The Yeomen of the Guard

The Yeomen of the Guard; or, The Merryman and His Maid, is a Savoy Opera, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert. It premiered at the Savoy Theatre on 3 October 1888, and ran for 423 performances...

at Stamford. At age 16, he earned his diploma as Associate of the Royal College of Organists

Royal College of Organists

The Royal College of Organists or RCO, is a charity and membership organisation based in the United Kingdom, but with members around the world...

, and at 18, he was awarded the degree of Bachelor of Music

Bachelor of Music

Bachelor of Music is an academic degree awarded by a college, university, or conservatory upon completion of program of study in music. In the United States, it is a professional degree; the majority of work consists of prescribed music courses and study in applied music, usually requiring a...

by the University of Durham.

Early career

St. Mary's Church, Melton Mowbray

St Mary's Church, Melton Mowbray is a parish church in the Church of England located in Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire.-Features:St Mary's Church is the largest and "stateliest" parish church in Leicestershire, with visible remains dating mainly from the 13th-15th centuries...

, Leicestershire, from 1914 to 1924, except for eight months in 1918 when he served as a private

Private (rank)

A Private is a soldier of the lowest military rank .In modern military parlance, 'Private' is shortened to 'Pte' in the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries and to 'Pvt.' in the United States.Notably both Sir Fitzroy MacLean and Enoch Powell are examples of, rare, rapid career...

in the Durham Light Infantry

Durham Light Infantry

The Durham Light Infantry was an infantry regiment of the British Army from 1881 to 1968. It was formed by the amalgamation of the 68th Regiment of Foot and the 106th Regiment of Foot along with the militia and rifle volunteers of County Durham...

during World War I. Sargent was chosen for the organist post over more than 150 other applicants. At the same time, he worked on many musical projects in Leicester, Melton Mowbray and Stamford, where he not only conducted but also produced the operas of Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan refers to the Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the librettist W. S. Gilbert and the composer Arthur Sullivan . The two men collaborated on fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which H.M.S...

and others for amateur societies. The Prince of Wales and his entourage often hunted in Leicestershire and watched the annual Gilbert and Sullivan productions there together with the Duke of York and other members of the Royal Family. At the age of 24, Sargent became England's youngest Doctor of Music

Doctor of Music

The Doctor of Music degree , like other doctorates, is an academic degree of the highest level. The D.Mus. is intended for musicians and composers who wish to combine the highest attainments in their area of specialization with doctoral-level academic study in music...

, with a degree from Durham.

Sargent's break came when Sir Henry Wood visited De Montfort Hall

De Montfort Hall

De Montfort Hall is a music and performance venue in Leicester, England. It is situated adjacent to Victoria Park and is named after Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester.-History:...

, Leicester

Leicester

Leicester is a city and unitary authority in the East Midlands of England, and the county town of Leicestershire. The city lies on the River Soar and at the edge of the National Forest...

, early in 1921 with the Queen's Hall orchestra. As it was customary to commission a piece from a local composer, Wood commissioned Sargent to write a piece entitled Impression on a Windy Day. Sargent completed the work too late for Wood to have enough time to learn it, and so Wood called on Sargent to conduct the first performance himself. Wood recognised not only the worth of the piece but also Sargent's talent as a conductor and gave him the chance to make his debut conducting the work at Wood's annual season of promenade concerts, generally known as the Proms

The Proms

The Proms, more formally known as The BBC Proms, or The Henry Wood Promenade Concerts presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert Hall in London...

, in the Queen's Hall

Queen's Hall

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect T.E. Knightley, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. From 1895 until 1941, it was the home of the promenade concerts founded by Robert...

on 11 October of the same year.

Sargent as composer attracted favourable notice in a Prom season when other composer-conductors included Gustav Holst

Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst was an English composer. He is most famous for his orchestral suite The Planets....

with his Planets

The Planets

The Planets, Op. 32, is a seven-movement orchestral suite by the English composer Gustav Holst, written between 1914 and 1916. Each movement of the suite is named after a planet of the Solar System and its corresponding astrological character as defined by Holst...

suite, and the next year, Wood included a nocturne

Nocturne

A nocturne is usually a musical composition that is inspired by, or evocative of, the night...

and scherzo

Scherzo

A scherzo is a piece of music, often a movement from a larger piece such as a symphony or a sonata. The scherzo's precise definition has varied over the years, but it often refers to a movement which replaces the minuet as the third movement in a four-movement work, such as a symphony, sonata, or...

by Sargent in the Proms programme, also conducted by the composer. Sargent was invited to conduct the Impression again in the 1923 season, but it was as a conductor that he made the greater impact. On the advice of Wood, among others, he soon abandoned composition in favour of conducting. He founded the amateur Leicester Symphony Orchestra in 1922, which he continued to conduct until 1939. Under Sargent, the orchestra's prestige grew until it was able to obtain such top-flight soloists as Alfred Cortot

Alfred Cortot

Alfred Denis Cortot was a Franco-Swiss pianist and conductor. He is one of the most renowned 20th-century classical musicians, especially valued for his poetic insight in Romantic period piano works, particularly those of Chopin and Schumann.-Early life and education:Born in Nyon, Vaud, in the...

, Artur Schnabel

Artur Schnabel

Artur Schnabel was an Austrian classical pianist, who also composed and taught. Schnabel was known for his intellectual seriousness as a musician, avoiding pure technical bravura...

, Solomon, Guilhermina Suggia

Guilhermina Suggia

Guilhermina Augusta Xavier de Medim Suggia Carteado Mena, known as Guilhermina Suggia, was a Portuguese cellist. She studied in Germany with Pablo Casals, and built an international reputation. She spent many years living in England, where she was particularly celebrated...

and Benno Moiseiwitsch

Benno Moiseiwitsch

Benno Moiseiwitsch CBE was a Ukrainian-born British pianist.-Biography:Born in Odessa, Ukraine, Moiseiwitsch began his studies at age seven at the Odessa Music Academy. He won the Anton Rubinstein Prize when he was just nine years old. He later took lessons from Theodor Leschetizky in Vienna...

. Moiseiwitsch gave Sargent piano lessons without charge, judging him talented enough to make a successful career as a concert pianist. At the instigation of Wood and Adrian Boult

Adrian Boult

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult CH was an English conductor. Brought up in a prosperous mercantile family he followed musical studies in England and at Leipzig, Germany, with early conducting work in London for the Royal Opera House and Sergei Diaghilev's ballet company. His first prominent post was...

, however, Sargent became a lecturer at the Royal College of Music

Royal College of Music

The Royal College of Music is a conservatoire founded by Royal Charter in 1882, located in South Kensington, London, England.-Background:The first director was Sir George Grove and he was followed by Sir Hubert Parry...

in London in 1923.

National fame

British National Opera Company

The British National Opera Company presented opera in English in London and on tour in the British provinces between 1922 and 1929. It was founded in December 1921 by singers and instrumentalists from Sir Thomas Beecham's Beecham Opera Company , which was disbanded when financial problems over...

, he conducted Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg is an opera in three acts, written and composed by Richard Wagner. It is among the longest operas still commonly performed today, usually taking around four and a half hours. It was first performed at the Königliches Hof- und National-Theater in Munich, on June 21,...

on tour in 1925, and for the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

D'Oyly Carte Opera Company

The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company was a professional light opera company that staged Gilbert and Sullivan's Savoy operas. The company performed nearly year-round in the UK and sometimes toured in Europe, North America and elsewhere, from the 1870s until it closed in 1982. It was revived in 1988 and...

, he conducted London seasons at the Prince's Theatre in 1926 and the newly-rebuilt Savoy Theatre

Savoy Theatre

The Savoy Theatre is a West End theatre located in the Strand in the City of Westminster, London, England. The theatre opened on 10 October 1881 and was built by Richard D'Oyly Carte on the site of the old Savoy Palace as a showcase for the popular series of comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan,...

in 1929–30. Sargent was criticised by The Times's

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

review of 20 September 1926 for adding "gags" to the Gilbert and Sullivan scores, although it praised the crispness of the ensemble, the "musicalness" of the performance and the beauty of the overture. Rupert D'Oyly Carte

Rupert D'Oyly Carte

Rupert D'Oyly Carte was an English hotelier, theatre owner and impresario, best known as proprietor of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company and Savoy Hotel from 1913 to 1948....

wrote to the paper stating that, in fact, Sargent had worked from Arthur Sullivan

Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan MVO was an English composer of Irish and Italian ancestry. He is best known for his series of 14 operatic collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including such enduring works as H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado...

's manuscript scores and had merely brought out the "details of the orchestration" exactly as Sullivan had written them. Some of the principal cast members and the stage director, J. M. Gordon

J. M. Gordon

J. M. Gordon, was an English singer, actor, stage manager and director, best known as the influential long-time director of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company following the death of W. S. Gilbert.-Life and career:...

, also objected to Sargent's fast tempi, at least at first. The D'Oyly Carte seasons brought Sargent's name to a wider public with an early BBC radio

BBC Radio

BBC Radio is a service of the British Broadcasting Corporation which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a Royal Charter since 1927. For a history of BBC radio prior to 1927 see British Broadcasting Company...

relay of The Mikado

The Mikado

The Mikado; or, The Town of Titipu is a comic opera in two acts, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert, their ninth of fourteen operatic collaborations...

in 1926 heard by up to eight million people. The Evening Standard

Evening Standard

The Evening Standard, now styled the London Evening Standard, is a free local daily newspaper, published Monday–Friday in tabloid format in London. It is the dominant regional evening paper for London and the surrounding area, with coverage of national and international news and City of London...

noted that this was "probably the largest audience that has ever heard anything at one time in the history of the world."

In 1927, Sergei Diaghilev

Sergei Diaghilev

Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev , usually referred to outside of Russia as Serge, was a Russian art critic, patron, ballet impresario and founder of the Ballets Russes, from which many famous dancers and choreographers would arise.-Early life and career:...

engaged Sargent to conduct for the Ballets Russes

Ballets Russes

The Ballets Russes was an itinerant ballet company from Russia which performed between 1909 and 1929 in many countries. Directed by Sergei Diaghilev, it is regarded as the greatest ballet company of the 20th century. Many of its dancers originated from the Imperial Ballet of Saint Petersburg...

, sharing the conducting duties with Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky ; 6 April 1971) was a Russian, later naturalized French, and then naturalized American composer, pianist, and conductor....

and Sir Thomas Beecham

Thomas Beecham

Sir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet CH was an English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic and the Royal Philharmonic orchestras. He was also closely associated with the Liverpool Philharmonic and Hallé orchestras...

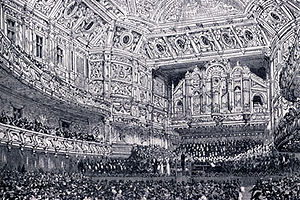

. Sargent also conducted for the final Ballets Russes season in 1928. In 1928 he became conductor of the Royal Choral Society

Royal Choral Society

The Royal Choral Society is an amateur choir, based in London. Formed soon after the opening of the Royal Albert Hall in 1871, the choir gave its first performance as the Royal Albert Hall Choral Society on 8 May 1872 – the choir's first conductor Charles Gounod included the Hallelujah Chorus from...

, and he retained this post for four decades until his death. The society was famous in the 1920s and 1930s for staged performances of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was an English composer who achieved such success that he was once called the "African Mahler".-Early life and education:...

's The Song of Hiawatha

The Song of Hiawatha (Coleridge-Taylor)

The Song of Hiawatha, Op. 30, is a trilogy of cantatas by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, produced between 1898 and 1900. The first part, Hiawatha's Wedding Feast, was particularly famous for many years and it made the composer's name known throughout the world.-Background:In 1898, Coleridge-Taylor was...

at the Royal Albert Hall

Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall situated on the northern edge of the South Kensington area, in the City of Westminster, London, England, best known for holding the annual summer Proms concerts since 1941....

, a work with which Sargent's name soon became synonymous.

Samuel Courtauld (industrialist)

Samuel Courtauld was an industrialist and Unitarian, chiefly remembered as the driving force behind the rapid growth of the Courtauld textile business in Britain....

, promoted a popular series of subscription concerts beginning in 1929 and on Schnabel's advice engaged Sargent as chief conductor, with guest conductors as eminent as Bruno Walter

Bruno Walter

Bruno Walter was a German-born conductor. He is considered one of the best known conductors of the 20th century. Walter was born in Berlin, but is known to have lived in several countries between 1933 and 1939, before finally settling in the United States in 1939...

, Otto Klemperer

Otto Klemperer

Otto Klemperer was a German conductor and composer. He is widely regarded as one of the leading conductors of the 20th century.-Biography:Otto Klemperer was born in Breslau, Silesia Province, then in Germany...

and Stravinsky. The Courtauld-Sargent concerts, as they became known, were aimed at people who had not previously attended concerts. They attracted large audiences bringing Sargent's name before another section of the public. In addition to the core repertory, Sargent introduced new works by Arthur Bliss

Arthur Bliss

Sir Arthur Edward Drummond Bliss, CH, KCVO was an English composer and conductor.Bliss's musical training was cut short by the First World War, in which he served with distinction in the army...

, Arthur Honegger

Arthur Honegger

Arthur Honegger was a Swiss composer, who was born in France and lived a large part of his life in Paris. He was a member of Les six. His most frequently performed work is probably the orchestral work Pacific 231, which is interpreted as imitating the sound of a steam locomotive.-Biography:Born...

, Zoltán Kodály

Zoltán Kodály

Zoltán Kodály was a Hungarian composer, ethnomusicologist, pedagogue, linguist, and philosopher. He is best known internationally as the creator of the Kodály Method.-Life:Born in Kecskemét, Kodály learned to play the violin as a child....

, Bohuslav Martinů

Bohuslav Martinu

Bohuslav Martinů was a prolific Czech composer of modern classical music. He was of Czech and Rumanian ancestry. Martinů wrote six symphonies, 15 operas, 14 ballet scores and a large body of orchestral, chamber, vocal and instrumental works. Martinů became a violinist in the Czech Philharmonic...

, Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor who mastered numerous musical genres and is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century...

, Karol Szymanowski

Karol Szymanowski

Karol Maciej Szymanowski was a Polish composer and pianist.-Life:Szymanowski was born into a wealthy land-owning Polish gentry family in Tymoszówka, then in the Russian Empire, now in Cherkasy Oblast, Ukraine. He studied music privately with his father before going to Gustav Neuhaus'...

and William Walton

William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton OM was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera...

, among others. At first, the plan was to engage the London Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra is a major orchestra of the United Kingdom, as well as one of the best-known orchestras in the world. Since 1982, the LSO has been based in London's Barbican Centre.-History:...

for these concerts, but the orchestra, a self-governing co-operative, refused to replace key players whom Sargent considered sub-standard. As a result, in conjunction with Beecham, Sargent set about establishing a new orchestra, the London Philharmonic

London Philharmonic Orchestra

The London Philharmonic Orchestra , based in London, is one of the major orchestras of the United Kingdom, and is based in the Royal Festival Hall. In addition, the LPO is the main resident orchestra of the Glyndebourne Festival Opera...

.

In these years Sargent tackled a wide range of repertoire, recording much of it, but he was particularly noted for performances of choral pieces. He promoted British music, as he would throughout his career, conducting Handel

George Frideric Handel

George Frideric Handel was a German-British Baroque composer, famous for his operas, oratorios, anthems and organ concertos. Handel was born in 1685, in a family indifferent to music...

's Messiah

Messiah (Handel)

Messiah is an English-language oratorio composed in 1741 by George Frideric Handel, with a scriptural text compiled by Charles Jennens from the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer. It was first performed in Dublin on 13 April 1742, and received its London premiere nearly a year later...

performed with large choruses and orchestras; and the premières of At the Boar's Head (1925) by Gustav Holst

Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst was an English composer. He is most famous for his orchestral suite The Planets....

; Hugh the Drover

Hugh the Drover

Hugh the Drover is an opera in two acts by Ralph Vaughan Williams to an original English libretto by Harold Child. According to Michael Kennedy, the composer took first inspiration for the opera from this question to Bruce Richmond, editor of The Times Literary Supplement, around 1909–1910:"I...

(1924) and Sir John in Love (1929) by Ralph Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams OM was an English composer of symphonies, chamber music, opera, choral music, and film scores. He was also a collector of English folk music and song: this activity both influenced his editorial approach to the English Hymnal, beginning in 1904, in which he included many...

; and Walton's oratorio

Oratorio

An oratorio is a large musical composition including an orchestra, a choir, and soloists. Like an opera, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias...

Belshazzar's Feast

Belshazzar's Feast (Walton)

Belshazzar's Feast is an oratorio by the English composer William Walton. It was first performed at the Leeds Festival on 8 October 1931. The work has remained one of Walton's most celebrated compositions and one of the most popular works in the English choral repertoire...

(at the Leeds

Leeds

Leeds is a city and metropolitan borough in West Yorkshire, England. In 2001 Leeds' main urban subdivision had a population of 443,247, while the entire city has a population of 798,800 , making it the 30th-most populous city in the European Union.Leeds is the cultural, financial and commercial...

Triennial Festival of 1931). To popularise classical music, Sargent conducted many concerts for young people including the Robert Mayer Concerts for Children from 1924 to 1939.

Difficult years and war years

In October 1932, Sargent suffered a near-fatal attack of tuberculosisTuberculosis

Tuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

. For almost two years he was unable to work, and it was only later in the 1930s that he returned to the concert scene. In 1936, he conducted his first opera at Covent Garden

Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply "Covent Garden", after a previous use of the site of the opera house's original construction in 1732. It is the home of The Royal Opera, The...

, Gustave Charpentier

Gustave Charpentier

Gustave Charpentier, , born in Dieuze, Moselle on 25 June 1860, died Paris, 18 February 1956) was a French composer, best known for his opera Louise.-Life and career:...

's Louise

Louise (opera)

Louise is an opera in four acts by Gustave Charpentier to an original French libretto by the composer, with some contributions by Saint-Pol-Roux, a symbolist poet and inspiration of the surrealists....

. He did not return to the Royal Opera House to conduct opera again until 1954, with Walton's Troilus and Cressida

Troilus and Cressida (opera)

Troilus and Cressida is the first of the two operas by William Walton. The libretto was by Christopher Hassall, his own first opera libretto, based on Chaucer's poem Troilus and Criseyde...

, although he did conduct the incidental music for a dramatisation of The Pilgrim's Progress

The Pilgrim's Progress

The Pilgrim's Progress from This World to That Which Is to Come is a Christian allegory written by John Bunyan and published in February, 1678. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of religious English literature, has been translated into more than 200 languages, and has never been...

given at the Royal Opera House in 1948.

As an orchestra conductor, the diligent Sargent had already been known as a hard taskmaster. According to The Independent

The Independent

The Independent is a British national morning newspaper published in London by Independent Print Limited, owned by Alexander Lebedev since 2010. It is nicknamed the Indy, while the Sunday edition, The Independent on Sunday, is the Sindy. Launched in 1986, it is one of the youngest UK national daily...

, he brought professionalism to orchestras by shaking them free of dead wood, clearing out talented dilettantes and pushing the survivors to perform at their best through relentless rehearsal. After giving a Daily Telegraph interview in 1936 in which he said that an orchestral musician did not deserve a "job for life" and should "give of his lifeblood with every bar he plays," Sargent lost much favour with musicians. They were particularly annoyed because of their support of him during his long illness, and Sargent thereafter faced frequent hostility from British orchestras.

Australian Broadcasting Corporation

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation, commonly referred to as "the ABC" , is Australia's national public broadcaster...

when, at the outbreak of World War II, he felt it his duty to return to his country, resisting strong pressure from the Australian media for him to stay. During the war, Sargent directed the Hallé Orchestra

The Hallé

The Hallé is a symphony orchestra based in Manchester, England. It is the UK's oldest extant symphony orchestra , supports a choir, youth choir and a youth orchestra, and releases its recordings on its own record label, though it has occasionally released recordings on Angel Records and EMI...

in Manchester (1939–42) and the Liverpool Philharmonic (1942–48) and became a popular BBC Home Service

BBC Home Service

The BBC Home Service was a British national radio station which broadcast from 1939 until 1967.-Development:Between the 1920s and the outbreak of The Second World War, the BBC had developed two nationwide radio services, the BBC National Programme and the BBC Regional Programme...

radio broadcaster. He helped boost public morale during the war by extensive concert tours around the country conducting for nominal fees. On one famous occasion, an air raid interrupted a performance of Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven was a German composer and pianist. A crucial figure in the transition between the Classical and Romantic eras in Western art music, he remains one of the most famous and influential composers of all time.Born in Bonn, then the capital of the Electorate of Cologne and part of...

's Symphony No. 7

Symphony No. 7 (Beethoven)

Ludwig van Beethoven's Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92, in 1811, was the seventh of his nine symphonies. He worked on it while staying in the Bohemian spa town of Teplice in the hope of improving his health. It was completed in 1812, and was dedicated to Count Moritz von Fries.At its debut,...

. Sargent stopped the orchestra, calmed the audience by saying they were safer inside the hall than fleeing outside, and resumed conducting. He later said that no orchestra had ever played so well and that no audience in his experience had ever listened so intently. In May 1941 Sargent conducted the last performance held in the Queen's Hall. Following an afternoon performance of Elgar

Edward Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet OM, GCVO was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestral works including the Enigma Variations, the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, concertos...

's The Dream of Gerontius

The Dream of Gerontius

The Dream of Gerontius, popularly called just Gerontius, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by Edward Elgar in 1900, to text from the poem by John Henry Newman. It relates the journey of a pious man's soul from his deathbed to his judgment before God and settling into Purgatory...

, the hall was destroyed during a night-time incendiary raid.

In 1945, Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini was an Italian conductor. One of the most acclaimed musicians of the late 19th and 20th century, he was renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orchestral detail and sonority, and his photographic memory...

invited Sargent to conduct the NBC Symphony Orchestra

NBC Symphony Orchestra

The NBC Symphony Orchestra was a radio orchestra established by David Sarnoff of the National Broadcasting Company especially for conductor Arturo Toscanini...

. In four concerts Sargent chose to present all English music, with the exception of Jean Sibelius

Jean Sibelius

Jean Sibelius was a Finnish composer of the later Romantic period whose music played an important role in the formation of the Finnish national identity. His mastery of the orchestra has been described as "prodigious."...

's Symphony No. 1

Symphony No. 1 (Sibelius)

Jean Sibelius's Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39 was written in 1898, when Sibelius was 33. The work was first performed on 26 April 1899 by the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by the composer, in an original version which has not survived. After the premiere, Sibelius made some...

and Antonín Dvořák

Antonín Dvorák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák was a Czech composer of late Romantic music, who employed the idioms of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia. Dvořák’s own style is sometimes called "romantic-classicist synthesis". His works include symphonic, choral and chamber music, concerti, operas and many...

's Symphony No. 7

Symphony No. 7 (Dvorák)

Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70, B. 141, by Antonín Dvořák was first performed in London on April 22, 1885 shortly after the piece was completed on March 17, 1885.-Compositional structure:Allegro maestosoPoco adagio...

. Two concertos, Walton

William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton OM was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera...

's Viola Concerto

Viola Concerto (Walton)

The Viola Concerto by William Walton was written in 1929 for the violist Lionel Tertis at the suggestion of Sir Thomas Beecham. The concerto carries the dedication "To Christabel" ....

with William Primrose

William Primrose

William Primrose CBE was a Scottish violist and teacher.-Biography:Primrose was born in Glasgow and studied violin initially. In 1919 he moved to study at the then Guildhall School of Music in London. On the urging of the accompanist Ivor Newton, Primrose moved to Belgium to study under Eugène...

, and Elgar's Violin Concerto

Violin Concerto (Elgar)

Edward Elgar's Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61, is one of his longest orchestral compositions, and the last of his works to gain immediate popular success....

with Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi Menuhin, Baron Menuhin, OM, KBE was a Russian Jewish American violinist and conductor who spent most of his performing career in the United Kingdom. He was born to Russian Jewish parents in the United States, but became a citizen of Switzerland in 1970, and of the United Kingdom in 1985...

, were programmed as part of these concerts. Menuhin judged Sargent's conducting of the latter "the next best to Elgar in this work."

The Proms and later years

Sargent was knightKnight

A knight was a member of a class of lower nobility in the High Middle Ages.By the Late Middle Ages, the rank had become associated with the ideals of chivalry, a code of conduct for the perfect courtly Christian warrior....

ed for his services to music in 1947 and performed in numerous English-speaking countries during the post-war years. He continued to promote British composers, conducting the premières of Walton's opera, Troilus and Cressida

Troilus and Cressida (opera)

Troilus and Cressida is the first of the two operas by William Walton. The libretto was by Christopher Hassall, his own first opera libretto, based on Chaucer's poem Troilus and Criseyde...

(1954), and Vaughan Williams's

Ralph Vaughan Williams

Ralph Vaughan Williams OM was an English composer of symphonies, chamber music, opera, choral music, and film scores. He was also a collector of English folk music and song: this activity both influenced his editorial approach to the English Hymnal, beginning in 1904, in which he included many...

Symphony No. 9

Symphony No. 9 (Vaughan Williams)

The Symphony No. 9 in E minor was the last symphony written by the British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. He composed it from 1956 to 1957 and it was given its premiere performance in London by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Malcolm Sargent on 2 April 1958, in the composer's...

(1958).

BBC Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Symphony Orchestra is the principal broadcast orchestra of the British Broadcasting Corporation and one of the leading orchestras in Britain.-History:...

from 1950 to 1957, succeeding Sir Adrian Boult. One author has written that "Sargent sometimes ruffled the orchestra in a way that Boult had never done. Indeed there were many people inside the BBC who profoundly regretted Boult's departure." The same author contended that Sargent was the target of criticism from the BBC's own Music Department for "not devoting enough time to the orchestra." Norman Lebrecht

Norman Lebrecht

Norman Lebrecht is a British commentator on music and cultural affairs and a novelist. He was a columnist for The Daily Telegraph from 1994 until 2002 and assistant editor of the Evening Standard from 2002 until 2009...

goes so far as to claim that that Sargent "almost wrecked" the BBC orchestra. Although the orchestra players bridled at some of Sargent's initiatives, there has been ample praise for Sargent's work with the orchestra. His biographer Reid contended, "Sargent's liveliness and drive soon gave BBC playing a gloss and briskness which had not been conspicuous before." Another biographer, Aldous, wrote, "Everywhere Sargent and the orchestra performed there were ovations, laurel wreaths and terrific reviews." The orchestra's reputation both in Britain and internationally grew during Sargent's tenure. The conductor had "great moments of triumph ... both at festivals overseas and during the Proms." In the 1950s and 1960s Sargent made many recordings with the BBC Symphony, as well as other ensembles, as described below. In this period, also, he conducted the concerts that opened the Royal Festival Hall

Royal Festival Hall

The Royal Festival Hall is a 2,900-seat concert, dance and talks venue within Southbank Centre in London. It is situated on the South Bank of the River Thames, not far from Hungerford Bridge. It is a Grade I listed building - the first post-war building to become so protected...

in 1951 and returned to the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company for the summer 1951 "Festival of Britain

Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition in Britain in the summer of 1951. It was organised by the government to give Britons a feeling of recovery in the aftermath of war and to promote good quality design in the rebuilding of British towns and cities. The Festival's centrepiece was in...

" season at the Savoy Theatre and the winter 1961–62 and 1963–64 seasons at the Savoy. In August 1956 the BBC announced that Sargent would be replaced as Chief Conductor of the BBC orchestra by Rudolf Schwarz

Rudolf Schwarz (conductor)

Rudolf Schwarz CBE was an Austrian-born conductor of Jewish ancestry. He became a British citizen and spent the latter half of his life in England.-Early life:...

. Sargent was given the title of "Chief Guest Conductor" and he remained Conductor-in-Chief of the Proms.

Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach was a German composer, organist, harpsichordist, violist, and violinist whose sacred and secular works for choir, orchestra, and solo instruments drew together the strands of the Baroque period and brought it to its ultimate maturity...

, Sibelius

Jean Sibelius

Jean Sibelius was a Finnish composer of the later Romantic period whose music played an important role in the formation of the Finnish national identity. His mastery of the orchestra has been described as "prodigious."...

, Dvořák

Antonín Dvorák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák was a Czech composer of late Romantic music, who employed the idioms of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia. Dvořák’s own style is sometimes called "romantic-classicist synthesis". His works include symphonic, choral and chamber music, concerti, operas and many...

, Berlioz

Hector Berlioz

Hector Berlioz was a French Romantic composer, best known for his compositions Symphonie fantastique and Grande messe des morts . Berlioz made significant contributions to the modern orchestra with his Treatise on Instrumentation. He specified huge orchestral forces for some of his works; as a...

, Rachmaninoff

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilievich Rachmaninoff was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of the last great representatives of Romanticism in Russian classical music...

, Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov was a Russian composer, and a member of the group of composers known as The Five.The Five, also known as The Mighty Handful or The Mighty Coterie, refers to a circle of composers who met in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in the years 1856–1870: Mily Balakirev , César...

, Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss was a leading German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras. He is known for his operas, which include Der Rosenkavalier and Salome; his Lieder, especially his Four Last Songs; and his tone poems and orchestral works, such as Death and Transfiguration, Till...

and Kodály

Zoltán Kodály

Zoltán Kodály was a Hungarian composer, ethnomusicologist, pedagogue, linguist, and philosopher. He is best known internationally as the creator of the Kodály Method.-Life:Born in Kecskemét, Kodály learned to play the violin as a child....

in three successive programmes. During his chief conductorship, prestigious foreign conductors and orchestras began to perform regularly at the Proms. In his first season in charge, Sargent and two assistant conductors conducted all the concerts among them; by 1966, there were Sargent and 25 other conductors. Those making their Prom debuts in the Sargent years included Carlo Maria Giulini

Carlo Maria Giulini

Carlo Maria Giulini was an Italian conductor.-Biography:Giulini was born in Barletta, Italy, to a father born in Lombardy and a mother born in Naples; but he was raised in Bolzano, which at the time of his birth was part of Austria...

, Georg Solti

Georg Solti

Sir Georg Solti, KBE, was a Hungarian-British orchestral and operatic conductor. He was a major classical recording artist, holding the record for having received the most Grammy Awards, having personally won 31 as a conductor, including the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. In addition to his...

, Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski was a British-born, naturalised American orchestral conductor, well known for his free-hand performing style that spurned the traditional baton and for obtaining a characteristically sumptuous sound from many of the great orchestras he conducted.In America, Stokowski...

, Rudolf Kempe

Rudolf Kempe

Rudolf Kempe was a German conductor.- Biography :Kempe was born in Dresden, where from the age of fourteen he studied at the Dresden State Opera School. He played oboe in the opera orchestra of Dortmund and then in the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra, from 1929...

, Pierre Boulez

Pierre Boulez

Pierre Boulez is a French composer of contemporary classical music, a pianist, and a conductor.-Early years:Boulez was born in Montbrison, Loire, France. As a child he began piano lessons and demonstrated aptitude in both music and mathematics...

and Bernard Haitink

Bernard Haitink

Bernard Johan Herman Haitink, CH, KBE is a Dutch conductor and violinist.- Early life :Haitink was born in Amsterdam, the son of Willem Haitink and Anna Haitink. He studied music at the conservatoire in Amsterdam...

. The charity founded in Sargent's name

CLIC Sargent

CLIC Sargent is charity in the United Kingdom that was formed by the merger of Sargent Cancer Care for Children and Cancer and Leukaemia in Childhood in 2005. The charity specializes in providing support for children with cancer....

continues to hold a special 'Promenade Concert' each year shortly after the main season ends.

Sargent made two tours of South America. In 1950 he conducted in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires is the capital and largest city of Argentina, and the second-largest metropolitan area in South America, after São Paulo. It is located on the western shore of the estuary of the Río de la Plata, on the southeastern coast of the South American continent...

, Montevideo

Montevideo

Montevideo is the largest city, the capital, and the chief port of Uruguay. The settlement was established in 1726 by Bruno Mauricio de Zabala, as a strategic move amidst a Spanish-Portuguese dispute over the platine region, and as a counter to the Portuguese colony at Colonia del Sacramento...

, Rio de Janeiro and Santiago

Santiago, Chile

Santiago , also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile, and the center of its largest conurbation . It is located in the country's central valley, at an elevation of above mean sea level...

. His programmes included Vaughan Williams's London

A London Symphony

A London Symphony is the second symphony composed by Ralph Vaughan Williams. The work is sometimes referred to as the Symphony No. 2, though it was not designated as such by the composer...

and 6th

Symphony No. 6 (Vaughan Williams)

Ralph Vaughan Williams's Symphony in E minor, published as Symphony No. 6, was composed in 1946–47, during and immediately after World War II. Dedicated to Michael Mullinar, it was first performed by Sir Adrian Boult and the BBC Symphony Orchestra on April 21, 1948. Within a year it had received...

Symphonies; Haydn

Joseph Haydn

Franz Joseph Haydn , known as Joseph Haydn , was an Austrian composer, one of the most prolific and prominent composers of the Classical period. He is often called the "Father of the Symphony" and "Father of the String Quartet" because of his important contributions to these forms...

's Symphony No. 88

Symphony No. 88 (Haydn)

The Symphony No. 88 in G major was written by Joseph Haydn. It is occasionally referred to as The Letter V referring to an older method of cataloguing Haydn's symphonic output.The symphony was completed in 1787...

, Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven was a German composer and pianist. A crucial figure in the transition between the Classical and Romantic eras in Western art music, he remains one of the most famous and influential composers of all time.Born in Bonn, then the capital of the Electorate of Cologne and part of...

's Symphony No. 8

Symphony No. 8 (Beethoven)

Symphony No. 8 in F Major, Op. 93 is a symphony in four movements composed by Ludwig van Beethoven in 1812. Beethoven fondly referred to it as "my little Symphony in F," distinguishing it from his Sixth Symphony, a longer work also in F....

, Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart , baptismal name Johannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart , was a prolific and influential composer of the Classical era. He composed over 600 works, many acknowledged as pinnacles of symphonic, concertante, chamber, piano, operatic, and choral music...

's Jupiter symphony

Symphony No. 41 (Mozart)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart completed his Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, on 10 August 1788. It was the last symphony that he composed.The work is nicknamed the Jupiter Symphony...

, Schubert

Franz Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert was an Austrian composer.Although he died at an early age, Schubert was tremendously prolific. He wrote some 600 Lieder, nine symphonies , liturgical music, operas, some incidental music, and a large body of chamber and solo piano music...

's 5th

Symphony No. 5 (Schubert)

The Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, D.485, written in 1816 by Franz Schubert is a work in four movements:#Allegro in B, in divided cut time.#Andante con moto in E, in 6:8 time.#Menuetto...

, Brahms

Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms was a German composer and pianist, and one of the leading musicians of the Romantic period. Born in Hamburg, Brahms spent much of his professional life in Vienna, Austria, where he was a leader of the musical scene...

's 2nd

Symphony No. 2 (Brahms)

The Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73, was composed by Johannes Brahms in the summer of 1877 during a visit to Pörtschach am Wörthersee, a town in the Austrian province of Carinthia. Its composition was brief in comparison with the fifteen years it took Brahms to complete his First Symphony...

and 4th

Symphony No. 4 (Brahms)

The Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98 by Johannes Brahms is the last of his symphonies. Brahms began working on the piece in 1884, just a year after completing his Symphony No...

, Sibelius

Jean Sibelius

Jean Sibelius was a Finnish composer of the later Romantic period whose music played an important role in the formation of the Finnish national identity. His mastery of the orchestra has been described as "prodigious."...

's 5th

Symphony No. 5 (Sibelius)

Symphony No. 5 in E flat major, Op. 82 is a major work for orchestra in three movements by Jean Sibelius.-History:Sibelius was commissioned to write this symphony by the Finnish government in honor of his 50th birthday, which had been declared a national holiday. The symphony was originally...

, Elgar's Serenade for Strings, Britten

Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten, OM CH was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He showed talent from an early age, and first came to public attention with the a cappella choral work A Boy Was Born in 1934. With the premiere of his opera Peter Grimes in 1945, he leapt to...

's Purcell Variations

The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra

The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra, Op. 34, is a musical composition by Benjamin Britten in 1946 with a subtitle "Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell"...

, Strauss

Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss was a leading German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras. He is known for his operas, which include Der Rosenkavalier and Salome; his Lieder, especially his Four Last Songs; and his tone poems and orchestral works, such as Death and Transfiguration, Till...

's Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, Walton

William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton OM was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera...

's Viola Concerto

Viola Concerto (Walton)

The Viola Concerto by William Walton was written in 1929 for the violist Lionel Tertis at the suggestion of Sir Thomas Beecham. The concerto carries the dedication "To Christabel" ....

and Dvořák

Antonín Dvorák

Antonín Leopold Dvořák was a Czech composer of late Romantic music, who employed the idioms of the folk music of Moravia and his native Bohemia. Dvořák’s own style is sometimes called "romantic-classicist synthesis". His works include symphonic, choral and chamber music, concerti, operas and many...

's Cello Concerto

Cello Concerto (Dvorák)

The Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191, by Antonín Dvořák was the composer's last solo concerto, and was written in 1894–1895 for his friend, the cellist Hanuš Wihan, but premiered by the English cellist Leo Stern.- Structure :...

with Pierre Fournier

Pierre Fournier

Pierre Fournier was a French cellist who was called the "aristocrat of cellists," on account of his elegant musicianship and majestic sound....

. The President of Uruguay

Uruguay

Uruguay ,officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay,sometimes the Eastern Republic of Uruguay; ) is a country in the southeastern part of South America. It is home to some 3.5 million people, of whom 1.8 million live in the capital Montevideo and its metropolitan area...

addressed him thus: "We Uruguayans are fond of all English people, Sir Malcolm, but especially fond of you." In 1952 Sargent conducted in all the above-mentioned cities and also in Lima

Lima

Lima is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín rivers, in the central part of the country, on a desert coast overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Together with the seaport of Callao, it forms a contiguous urban area known as the Lima...

. Half his repertory on that tour consisted of British music and included Delius

Frederick Delius

Frederick Theodore Albert Delius, CH was an English composer. Born in the north of England to a prosperous mercantile family of German extraction, he resisted attempts to recruit him to commerce...

, Vaughan Williams, Britten, Walton, and Handel.

When the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra

The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra is a British orchestra based in London. It tours widely, and is sometimes referred to as "Britain's national orchestra"...

was in danger of extinction after Beecham's death in 1961, Sargent played a major part in saving the orchestra, doing much to win back the good opinion of orchestral players that he had lost because of his 1936 interview. In the 1960s, Sargent toured Russia, the United States, Canada, Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

, Israel, India, the Far East and Australia. By the mid-1960s, however, his health began to deteriorate.

Sargent underwent surgery in July 1967 for pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer refers to a malignant neoplasm of the pancreas. The most common type of pancreatic cancer, accounting for 95% of these tumors is adenocarcinoma, which arises within the exocrine component of the pancreas. A minority arises from the islet cells and is classified as a...

but made a valedictory appearance at the end of the last night of the Proms in September that year, handing over the baton to his successor, Colin Davis

Colin Davis

Sir Colin Rex Davis, CH, CBE is an English conductor. His repertoire is broad, but among the composers with whom he is particularly associated are Mozart, Berlioz, Elgar, Sibelius, Stravinsky and Tippett....

. He died two weeks later, at the age of 72. He was buried in Stamford cemetery alongside members of his family.

Musical reputation and repertoire

ToscaniniArturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini was an Italian conductor. One of the most acclaimed musicians of the late 19th and 20th century, he was renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orchestral detail and sonority, and his photographic memory...

, Beecham

Thomas Beecham

Sir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet CH was an English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic and the Royal Philharmonic orchestras. He was also closely associated with the Liverpool Philharmonic and Hallé orchestras...

and many others regarded Sargent as the finest choral conductor in the world. Even orchestral musicians gave him credit: the principal violist of the BBC Symphony Orchestra wrote of him, "He is able to instil into the singers a life and efficiency they never dreamed of. You have only to see the eyes of a choral society screwing into him like hundreds of gimlets to understand what he means to them." However, another of Sargent's colleagues, Sir Adrian Boult, said of him, "[H]e was a great all-rounder but never developed his potentialities, which were enormous, simply because he didn't think hard enough about music – he never troubled to improve on a successful interpretation. He was too interested in other things, and not single-minded enough about music." Although orchestral players resented Sargent for much of his career after the 1936 interview, instrumental soloists generally liked working with him. The cellist Pierre Fournier called him a "guardian angel" and compared him favourably with George Szell

George Szell

George Szell , originally György Széll, György Endre Szél, or Georg Szell, was a Hungarian-born American conductor and composer...

and Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan

Herbert von Karajan was an Austrian orchestra and opera conductor. To the wider world he was perhaps most famously associated with the Berlin Philharmonic, of which he was principal conductor for 35 years...

. Artur Schnabel

Artur Schnabel

Artur Schnabel was an Austrian classical pianist, who also composed and taught. Schnabel was known for his intellectual seriousness as a musician, avoiding pure technical bravura...

, Jascha Heifetz

Jascha Heifetz

Jascha Heifetz was a violinist, born in Vilnius, then Russian Empire, now Lithuania. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest violinists of all time.- Early life :...

and Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi Menuhin, Baron Menuhin, OM, KBE was a Russian Jewish American violinist and conductor who spent most of his performing career in the United Kingdom. He was born to Russian Jewish parents in the United States, but became a citizen of Switzerland in 1970, and of the United Kingdom in 1985...

thought similarly highly of him. Cyril Smith

Cyril Smith (pianist)

Cyril James Smith OBE was a virtuoso concert pianist of the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, and a piano teacher.-Personal life:...

wrote in his autobiography, "...he seems to sense what the pianist wants of the music even before he begins to play it.... He has an incredible speed of mind, and it has always been a great joy, as well as a rare professional experience, to work with him." For this reason, among others, Sargent was continually in demand as a conductor for concertos.

The Times

The Times

The Times is a British daily national newspaper, first published in London in 1785 under the title The Daily Universal Register . The Times and its sister paper The Sunday Times are published by Times Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary since 1981 of News International...

obituary said Sargent "was of all British conductors in his day the most widely esteemed by the lay public... a fluent, attractive pianist, a brilliant score-reader, a skilful and effective arranger and orchestrator... as a conductor his stick technique was regarded by many as the most accomplished and reliable in the world.... [H]is taste... was moulded by the Victorian

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

cathedral tradition into which he was born." It commented that, in his later years, his interpretations of the standard classical and romantic repertoire were "prepared... down to the last detail" but sometimes "unexuberant", though his performances of "the music composed within his lifetime... remained lucid and continually compelling." The flute player Gerald Jackson wrote, "I feel that [Walton] conducts his own music as well as anyone else, with the possible exception of Sargent, who of course introduced and always makes a big thing of Belshazzar's Feast

Belshazzar's Feast (Walton)

Belshazzar's Feast is an oratorio by the English composer William Walton. It was first performed at the Leeds Festival on 8 October 1931. The work has remained one of Walton's most celebrated compositions and one of the most popular works in the English choral repertoire...

."

The composers whose works Sargent regularly conducted included, from the eighteenth century, J. S. Bach, Handel, Gluck

Christoph Willibald Gluck

Christoph Willibald Ritter von Gluck was an opera composer of the early classical period. After many years at the Habsburg court at Vienna, Gluck brought about the practical reform of opera's dramaturgical practices that many intellectuals had been campaigning for over the years...

, Mozart and Haydn; and from the nineteenth century, Beethoven, Berlioz, Schubert, Schumann

Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann, sometimes known as Robert Alexander Schumann, was a German composer, aesthete and influential music critic. He is regarded as one of the greatest and most representative composers of the Romantic era....

, Mendelssohn

Felix Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Barthóldy , use the form 'Mendelssohn' and not 'Mendelssohn Bartholdy'. The Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians gives ' Felix Mendelssohn' as the entry, with 'Mendelssohn' used in the body text...

, Brahms, Wagner

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner was a German composer, conductor, theatre director, philosopher, music theorist, poet, essayist and writer primarily known for his operas...

, Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian: Пётр Ильи́ч Чайко́вский ; often "Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky" in English. His names are also transliterated "Piotr" or "Petr"; "Ilitsch", "Il'ich" or "Illyich"; and "Tschaikowski", "Tschaikowsky", "Chajkovskij"...

, Smetana

Bedrich Smetana

Bedřich Smetana was a Czech composer who pioneered the development of a musical style which became closely identified with his country's aspirations to independent statehood. He is thus widely regarded in his homeland as the father of Czech music...

, Sullivan

Arthur Sullivan

Sir Arthur Seymour Sullivan MVO was an English composer of Irish and Italian ancestry. He is best known for his series of 14 operatic collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, including such enduring works as H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado...

and Dvořák. From the twentieth century, British composers in his repertoire included Bliss, Britten, Delius, Elgar (a favourite, especially Elgar's oratorio

Oratorio

An oratorio is a large musical composition including an orchestra, a choir, and soloists. Like an opera, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias...

s The Dream of Gerontius

The Dream of Gerontius

The Dream of Gerontius, popularly called just Gerontius, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by Edward Elgar in 1900, to text from the poem by John Henry Newman. It relates the journey of a pious man's soul from his deathbed to his judgment before God and settling into Purgatory...

, The Apostles

The Apostles (Elgar)

The Apostles, Op. 49, is an oratorio for soloists, chorus and orchestra composed by Edward Elgar. It was first performed on 14 October 1903.-Overview:...

and The Kingdom

The Kingdom (Elgar)

The Kingdom, Op. 51, is an oratorio for soloists, chorus and orchestra composed by Edward Elgar.It was first performed at the Birmingham Music Festival on 3 October 1906, with the orchestra conducted by the composer, and soloists Agnes Nicholls, Muriel Foster, John Coates and William Higley. The...

and symphonies), Holst, Tippett

Michael Tippett

Sir Michael Kemp Tippett OM CH CBE was an English composer.In his long career he produced a large body of work, including five operas, three large-scale choral works, four symphonies, five string quartets, four piano sonatas, concertos and concertante works, song cycles and incidental music...

, Vaughan Williams and Walton. With the exception of Alban Berg's Violin Concerto

Violin Concerto (Berg)

Alban Berg's Violin Concerto was written in 1935 . It is probably Berg's best-known and most frequently performed instrumental piece.-Conception and composition:...

, Sargent avoided the works of the Second Viennese School

Second Viennese School

The Second Viennese School is the group of composers that comprised Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils and close associates in early 20th century Vienna, where he lived and taught, sporadically, between 1903 and 1925...

but programmed works by Bartók

Béla Bartók

Béla Viktor János Bartók was a Hungarian composer and pianist. He is considered one of the most important composers of the 20th century and is regarded, along with Liszt, as Hungary's greatest composer...

, Dohnányi

Erno Dohnányi

Ernő Dohnányi was a Hungarian conductor, composer, and pianist. He used the German form of his name Ernst von Dohnányi for most of his published compositions....

, Hindemith

Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith was a German composer, violist, violinist, teacher, music theorist and conductor.- Biography :Born in Hanau, near Frankfurt, Hindemith was taught the violin as a child...

, Honegger

Arthur Honegger

Arthur Honegger was a Swiss composer, who was born in France and lived a large part of his life in Paris. He was a member of Les six. His most frequently performed work is probably the orchestral work Pacific 231, which is interpreted as imitating the sound of a steam locomotive.-Biography:Born...

, Kodály

Zoltán Kodály

Zoltán Kodály was a Hungarian composer, ethnomusicologist, pedagogue, linguist, and philosopher. He is best known internationally as the creator of the Kodály Method.-Life:Born in Kecskemét, Kodály learned to play the violin as a child....

, Martinů

Bohuslav Martinu

Bohuslav Martinů was a prolific Czech composer of modern classical music. He was of Czech and Rumanian ancestry. Martinů wrote six symphonies, 15 operas, 14 ballet scores and a large body of orchestral, chamber, vocal and instrumental works. Martinů became a violinist in the Czech Philharmonic...

, Poulenc

Francis Poulenc

Francis Jean Marcel Poulenc was a French composer and a member of the French group Les six. He composed solo piano music, chamber music, oratorio, choral music, opera, ballet music, and orchestral music...

, Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor who mastered numerous musical genres and is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century...

, Rachmaninoff

Sergei Rachmaninoff

Sergei Vasilievich Rachmaninoff was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor. Rachmaninoff is widely considered one of the finest pianists of his day and, as a composer, one of the last great representatives of Romanticism in Russian classical music...

, Shostakovich

Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich was a Soviet Russian composer and one of the most celebrated composers of the 20th century....

, Sibelius

Jean Sibelius

Jean Sibelius was a Finnish composer of the later Romantic period whose music played an important role in the formation of the Finnish national identity. His mastery of the orchestra has been described as "prodigious."...

, Richard Strauss

Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss was a leading German composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras. He is known for his operas, which include Der Rosenkavalier and Salome; his Lieder, especially his Four Last Songs; and his tone poems and orchestral works, such as Death and Transfiguration, Till...

, Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky ; 6 April 1971) was a Russian, later naturalized French, and then naturalized American composer, pianist, and conductor....

and Szymanowski

Karol Szymanowski

Karol Maciej Szymanowski was a Polish composer and pianist.-Life:Szymanowski was born into a wealthy land-owning Polish gentry family in Tymoszówka, then in the Russian Empire, now in Cherkasy Oblast, Ukraine. He studied music privately with his father before going to Gustav Neuhaus'...

.

Private life

In 1923, Sargent married Eileen Laura Harding Horne, daughter of Frederic Horne of Drinkstone, SuffolkSuffolk

Suffolk is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in East Anglia, England. It has borders with Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south. The North Sea lies to the east...

. Sargent's biographers differ on her background. Aldous states that she was a maid in domestic service, whereas Reid notes that she was a keen rider, with many friends in hunting circles, and that her uncle (who officiated at her wedding to Sargent) was rector

Rector

The word rector has a number of different meanings; it is widely used to refer to an academic, religious or political administrator...

of Drinkwater, Suffolk

Suffolk

Suffolk is a non-metropolitan county of historic origin in East Anglia, England. It has borders with Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south. The North Sea lies to the east...

. According to Aldous, it was believed locally that Sargent had to marry Horne, having made her pregnant. By 1926, the couple had two children, a daughter Pamela who was to die of polio in 1944, and a son Peter. Sargent was much affected by his daughter's death, and his recording of Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius

The Dream of Gerontius

The Dream of Gerontius, popularly called just Gerontius, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by Edward Elgar in 1900, to text from the poem by John Henry Newman. It relates the journey of a pious man's soul from his deathbed to his judgment before God and settling into Purgatory...

in 1945 was an expression of his grief at her passing.

Sargent's marriage was unhappy and ended in divorce in 1946. Before, during and after his marriage, Sargent was a continual womaniser, a fact that he did not deny. His liaisons with powerful women began early, in Stamford, when he was still conducting the Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan refers to the Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the librettist W. S. Gilbert and the composer Arthur Sullivan . The two men collaborated on fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which H.M.S...

shows attended by the London gentry who came to join the Melton Mowbray

Melton Mowbray

Melton Mowbray is a town in the Melton borough of Leicestershire, England. It is to the northeast of Leicester, and southeast of Nottingham...

hunt. Among his affairs were long-standing ones with Diana Bowes-Lyon

John Herbert Bowes-Lyon

John Herbert "Jock" Bowes-Lyon , was the second son of the 14th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne and the Countess of Strathmore and Kinghorne, the favourite brother of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon...

, Princess Marina

Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent

Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent, née Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark was a member of the British Royal Family; the wife of Prince George, Duke of Kent, the fourth son of King George V of the United Kingdom and Mary of Teck....

and Edwina Mountbatten. More casual encounters are typified by the young woman who said, "Promise me that whatever happens I shan't have to go home alone in a taxi with Malcolm Sargent."

Away from music, Sargent was elected a member of The Literary Society

The Literary Society

The Literary Society is a London dining club, founded by William Wordsworth and others in 1807. Its members are generally either prominent figures in English literature or eminent people in other fields with a strong interest in literature. No papers are delivered at its meetings. It meets monthly...

, a dining club founded in 1807 by William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth was a major English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with the 1798 joint publication Lyrical Ballads....

and others. He was also a member of the Beefsteak Club

Beefsteak Club

Beefsteak Club is the name, nickname and historically common misnomer applied by sources to several 18th and 19th century male dining clubs that celebrated the beefsteak as a symbol of patriotic and often Whig concepts of liberty and prosperity....

, for which his proposer was Sir Edward Elgar

Edward Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet OM, GCVO was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestral works including the Enigma Variations, the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, concertos...

, the Garrick

Garrick Club

The Garrick Club is a gentlemen's club in London.-History:The Garrick Club was founded at a meeting in the Committee Room at Theatre Royal, Drury Lane on Wednesday 17 August 1831...

, and the long-established and aristocratic White's and Pratt's clubs. His public service appointments included the joint presidency of the London Union of Youth Clubs, and the presidency of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals is a charity in England and Wales that promotes animal welfare. In 2009 the RSPCA investigated 141,280 cruelty complaints and collected and rescued 135,293 animals...

.