Military history of Oceania

Encyclopedia

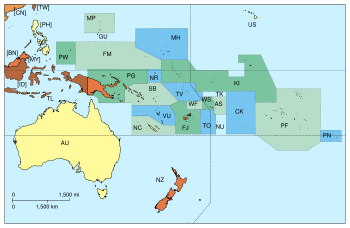

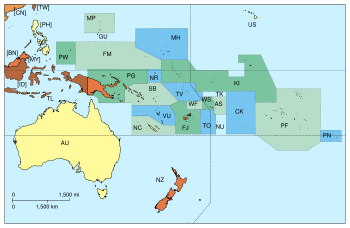

Although the military history of Oceania

probably goes back thousands of years to the first human settlement in the region, little is known about war in Oceania until the arrival of Europeans. The introduction of firearms transformed conflict in the region; in some cases helping to unify regions and in others sparking large-scale tribal and civil wars. Force and the threat of force played a role in the annexation of most of Oceania to various European and American powers, but only in Australia and New Zealand did wars of conquest occur. Western Oceania was a major site of conflict in World War II as the Japanese Empire sought to expand southwards. Since 1945 the region has been mostly at peace, although Melanesia

has suffered from Indonesia

n expansionism in some areas and civil wars and coups in others. The Australian Defence Force

is currently the largest military force in Oceania.

Violent conflict was common to nearly all the peoples of Oceania in the period before European arrival, although there is much debate about the frequency of warfare, which of course varied between different societies. Some scholars have argued that peaceful societies are very unusual, with Lawrence H. Keeley of the University of Illinois

Violent conflict was common to nearly all the peoples of Oceania in the period before European arrival, although there is much debate about the frequency of warfare, which of course varied between different societies. Some scholars have argued that peaceful societies are very unusual, with Lawrence H. Keeley of the University of Illinois

calculating that 87 per cent of tribal societies were at war more than once per year, and some 65 per cent of them were fighting continuously.http://www.troynovant.com/Franson/Keeley/War-Before-Civilization.html For instance, in Arnhem

Land in northern Australia, a study of warfare among the Murngin people in the late-19th century found that over a 20-year period no less than 200 out of 800 men, or 25 percent of all adult males, had been killed in intertribal warfare.http://washingtontimes.com/books/20030816-105047-3673r.htm On the other hand, New Zealand historian James Belich

cautions against the assumption that tribal societies were inevitably in a constant state of war, pointing out that oral histories tend to emphasise warfare rather than peace even if there is far more of the latter than the former, and that estimating the frequency of war based on the number of weapons and fortifications is like estimating the number of house fires based on the number of insurance policies. However it is clear that in most societies warriors were held in high esteem and that completely pacifist societies were very unusual. One exception was the Moriori

of the Chatham Islands

.

A range of weapons were used in Oceania. These included the woomera

and boomerang

in Australia, and the bow

in some parts of Melanesia and Polynesia. Nearly all Oceanic peoples had spears and clubs, although the Māori of New Zealand were unusual in having no distance weapons. Weapons could be very simple or elaborately crafted, with distance weapons in particular requiring a great deal of craftsmanship to be accurate. It has been estimated that Aboriginal spears were more accurate than nineteenth century European firearms.

Most pre-European conflicts in Oceania took place between peoples with a shared culture, and often language. However there were also wars between peoples of different cultures, for example in Australia and Papua New Guinea, each of which contains many different cultures, and in central Polynesia, where island groups are close enough for parties of war canoes to travel to other territories.

in which iwi

(tribes) with musket

s attacked iwi who lacked them. Serious warfare raged throughout New Zealand for nearly thirty years, only ending when all tribes had acquired muskets. The presence of European ships also affected Māori warfare, for example enabling Māori to travel to the Chatham Islands, where they almost wiped out the Moriori. The presence of firearms could also turn what would otherwise have been minor squabbles into full-scale wars. One such was the Nauruan Tribal War

, which lasted for a decade and ultimately resulted in the annexation of Nauru

by Germany. In other parts of the Pacific, particular leaders were able to use their contacts with Europeans to unify their islands. One leader who did this was the Fijian chief Tanoa Visawaqa

who, in the 1840s, used arms purchased from a Swedish mercenary to subdue most of Western Fiji. Tonga was also united into a kingdom around this time.

Armed force, or the threat thereof, was sometimes used to gain European sovereignty over Oceanic nations. One example of this was the 'Bayonet Constitution

' of Hawai'i. This was not the only method of winning sovereignty. In some cases a treaty was peacefully agreed to, but even in these cases violence or the fear of it was often still a factor. For example New Zealand's Treaty of Waitangi

was presented to Māori partly as a way to prevent a French invasion and partly as a way to stop inter-tribal warfare; while Tonga became a British protected state as a result of an attempt to oust the Tongan king. In other parts of the region, such as Australia, European sovereignty was simply proclaimed without any attempt to win the consent of the indigenous peoples. In many cases, including those in which sovereignty had been ceded more or less voluntarily, force and the threat of force were required to maintain European dominance.

Although virtually every part of Oceania was at some point annexed by a foreign power, in most cases there was no major European settlement. The smallness of most Pacific islands coupled with their lack of resources or strategic importance meant that during the nineteenth century they were targets for neither large-scale immigration nor substantial military involvement. The majority of Europeans in most of the islands were colonial administrators, missionaries and traders. The two major exceptions to this were Australia and New Zealand, both of which had enough land and cool enough climates to attract huge numbers of British settlers. These were initially welcomed by most Māori and rejected by most Australian Aborigines, but in both cases wars broke out; In Australia, when settlers wanted more land than the indigenous peoples were willing to part with, land was the primary motivation. In New Zealand, although land was an issue, major conflicts were primarily over who controlled the country. In Australia there was a mixture of battles, guerrilla tactics and genocide, while in New Zealand fighting was characterised by assaults on complicated defensive positions, Pa

Although virtually every part of Oceania was at some point annexed by a foreign power, in most cases there was no major European settlement. The smallness of most Pacific islands coupled with their lack of resources or strategic importance meant that during the nineteenth century they were targets for neither large-scale immigration nor substantial military involvement. The majority of Europeans in most of the islands were colonial administrators, missionaries and traders. The two major exceptions to this were Australia and New Zealand, both of which had enough land and cool enough climates to attract huge numbers of British settlers. These were initially welcomed by most Māori and rejected by most Australian Aborigines, but in both cases wars broke out; In Australia, when settlers wanted more land than the indigenous peoples were willing to part with, land was the primary motivation. In New Zealand, although land was an issue, major conflicts were primarily over who controlled the country. In Australia there was a mixture of battles, guerrilla tactics and genocide, while in New Zealand fighting was characterised by assaults on complicated defensive positions, Pa

s, though on occasion warfare was more or less conventional and on other occasions both sides used guerrilla tactics. There was a distinct difference in scale - at the height of the New Zealand Land Wars

18,000 English troops were required, in addition to settler and "loyal native" forces to contain the belligerent minority of the well armed and militarily competent Māori. Nevertheless, in both cases 'native resistance' was eventually subdued although in Australia occasional fighting continued into the twentieth century.

Although World War I occurred almost entirely in Europe and the Middle East, Oceania was involved in a number of ways. British settlers and their descendants in Australia and New Zealand enthusiastically signed up to fight for their 'mother country', as did some Māori. Australian and New Zealand troops, joined together in ANZAC formations, fought and died in large numbers in the Gallipoli Campaign

, the Western Front

and in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign

in the Middle East.

In Oceania itself, islands possessed by Germany were invaded by Japan (see Japan during World War I

), Australia (German New Guinea

and Nauru

), and New Zealand (German Samoa

), with little serious resistance apart from the Battle of Bita Paka

in German New Guinea.

After the war the islands were granted to their new conquerors by the League of Nations

as mandated territories. In this way, Japan took control of the Mariana Islands

, Caroline Islands

and Marshall Islands

, while Australia took over German New Guinea

and New Zealand took over German Samoa

. Nauru

was administered by the United Kingdom in conjunction with Australia and New Zealand.

The western Pacific was a major site of fighting between Japan and the United States-led Allies. Japan conquered most of Melanesia and South-East Asia, and brought the United States into the war by bombing the US possession of Hawaii at Pearl Harbor

. The inhabitants of areas conquered by the Japanese were often harshly treated; for example 1,200 Nauruans were forcibly transported as labour to the Chuuk islands

, where 463 died. Papua New Guinea

was a major battleground, and the Japanese possessions taken from Germany during World War I were re-taken by the United States, with the Mariana Islands serving as a US bombing base. New Zealand and most of Polynesia remained relatively untouched by the war, apart from the sending of troops and the visits of American servicement on rest and recreation leave.

As with the First World War, New Zealand and Australia were enthusiastic defenders of Britain in World War II, and some other member countries of the British Empire

also sent troops. New Zealand forces served primarily in Europe, fighting in Greece

, North Africa

and Italy, but with some forces serving in Singapore

, Fiji

, and in the Solomon Islands campaign

. Australian initially sent troops to Europe, most were recalled to the Pacific following Japan's push southward, which included air raids on Darwin and other parts of Australia

in 1942-43. Australian soldiers fought crucial battles along the Kokoda Track

in Papua New Guinea

and in the Borneo campaign

.

(where there were attempts by Indonesia

to extend its territory in the area), a civil war

in Bougainville

and several coups in Fiji

. During this time many Pacific nations won their independence, usually peacefully. However a number of islands remained territories of European, Asian and American powers, and several were used as nuclear testing sites. In the 1970s, these activities became highly controversial. Meanwhile, several Oceanic countries, notably Australia and New Zealand, contributed combat and peacekeeping troops to a range of conflicts outside of Oceania.

.jpg)

. Tests were conducted in various locations by the United Kingdom (Operation Grapple

and Operation Antler), the United States (Bikini atoll

and the Marshall Islands

) and France (Moruroa

), often with devastating consequences for the inhabitants. In 1954, for example, fallout

from the American Castle Bravo

hydrogen bomb test in the Marshall Islands

was such that the inhabitants of the Rongelap Atoll were forced to abandon their island. Three years later the islanders were allowed to return, but suffered abnormally high levels of cancer. They were evacuated again in 1985 and in 1996 given $45 million in compensation. A series of British tests were also conducted in the 1950s at Maralinga

in South Australia

, forcing the removal of the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara peoples from their ancestral homelands. The atoll of Moruroa

in French Polynesia

became notorious as a site of French nuclear testing, primarily because tests were carried out there after most Pacific testing had ceased. These tests were opposed by most other nations in Oceania. The last atmospheric test was conducted in 1974, and the last underground test in 1996.

with the British territories of Sarawak

and British North Borneo into a new nation of Malaysia. Indonesia felt that this would increase British power in the region and threaten Indonesian independence. From 1963 Indonesian troops began conducting guerrilla raids into Malaysia, and British, Australian and New Zealand troops were brought in. In 1965 there was an attempted coup in Indonesia, and the subsequent power struggles reduced that country's ability to conduct external warfare. A peace treaty was signed the following year.

.svg.png)

In 1975, East Timor

declared itself independent, following the withdrawal of its coloniser Portugal. Nine days later the area was invaded by Indonesia. Because the East Timorese FRETILIN party had some communist support, the Indonesia government was able to portray its actions as anti-communist, and thus won the backing of the United States and Australia. A detailed statistical report prepared for the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor

cited a lower range of 102,800 conflict-related deaths in the Indonesian occupation period 1974-1999, namely, approximately 18,600 killings and 84,200 'excess' deaths from hunger and illness. Amnesty International

estimates the death toll to be about 200,000. A guerrilla campaign against Indonesia was carried out by Falintil

throughout the period of occupation.

In 1999 a United Nations

supervised referendum

was held as a result of an agreement between Indonesia, Portugal and the United States. The East Timorese voted for full independence. The Indonesian military backed militia attacks within East Timor, and a peacekeeping force consisting mostly of Australian and New Zealand troops was sent in. East Timor's independence was recognised in 2006, but since then there have been two major outbreaks of violence, each requiring the intervention of UN-backed troops.

and Indo-Fijians, who originally came to the islands as indentured labour in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The 1987 coup followed the election of a multi-ethnic coalition, which Lieutenant Colonel

Sitiveni Rabuka

overthrew, claiming racial discrimination against ethnic Fijians. The coup was denounced by the United Nations

and Fiji was expelled from the Commonwealth of Nations

.

The 2000 coup was essentially a repeat of the 1987 affair, although it was led by civilian George Speight

, apparently with military support. Commodore

Frank Bainimarama

, who was opposed to Speight, then took over and appointed a new Prime Minister. Speight was later tried and convicted for treason

. Many indigenous Fijians were unhappy at the treatment of Speight and his supporters, feeling that the coup had been legitimate. In 2006 the Fijian parliament attempted to introduce a series of bills which would have, amongst other things, pardoned those involved in the 2000 coup. Bainimarama, concerned that the legal and racial injustices of the previous coups would be perpetuated, staged his own coup. It was internationally condemned, and Fiji again suspended from the Commonwealth.

to secede from Papua New Guinea

. These were resisted by Papua New Guinea primarily because of the presence in Bougainville of the Panguna mine, which was vital to Papua New Guinea's economy. The Bougainville Revolutionary Army

began attacking the mine in 1988, forcing its closure the following year. Further BRA activity led to the declaration of a state of emergency

and the conflict continued until about 2005, when successionist leader and self-proclaimed King of Bougainville Francis Ona

died of malaria. Peacekeeping troops led by Australia have been in the region since the late 1990s, and a referendum on independence will be held in the 2010s.

Oceanic military forces have played minor roles in numerous conflicts outside Oceania since 1945. The region's two biggest military powers, Australia and New Zealand, sent troops to fight in the Korean

Oceanic military forces have played minor roles in numerous conflicts outside Oceania since 1945. The region's two biggest military powers, Australia and New Zealand, sent troops to fight in the Korean

, Vietnam

, Gulf

and Afghanistan War

s, and Australia also participated in the Iraq War. Neither is a major military power in world terms, preferring to join with coalition operations, but both possess modern and well trained defense forces. Both have made significant contributions to international peacekeeping

operations, although their focus has tended to be within Oceania.

Following the fall of Singapore in World War II, Australia and New Zealand both came to the realisation that Britain could no longer protect her former colonies in the Pacific. Accordingly, both countries desired an alliance with the United States and in 1951 the ANZUS

Treaty was signed between the three countries. This meant that if a Treaty partner came under attack, the other two would be required to come to its aid. Although none of the ANZUS partners came under attack, (until, arguably, September 11, 2001, or the Rainbow Warrior bombing

), both Australia and New Zealand nonetheless felt obliged to help America in its Cold War

conflicts in Korea and Vietnam. Because of its close proximity to Asia, Australia has always been more worried than New Zealand about an invasion from Asia, and has thus been a more enthusiastic partner with America. New Zealand's contribution to the Vietnam War was small, whereas Australia went as far as to introduce conscription

. By the 1970s, many people in both countries had begun to oppose the American alliance, not least because of Vietnam. America's role as a major nuclear power was also a strong factor in anti-American sentiment. In 1984 New Zealand enacted a ban on nuclear armed or powered ships in its waters, essentially preventing most American naval ships from visiting New Zealand. As a result, America suspended it's treaty obligations to New Zealand under the ANZUS alliance. Despite this, New Zealand committed small numbers of soldiers to the 1991 Gulf and Afghanistan Wars, and has sent engineering units to Iraq. Australia has remained a strong supporter of America, despite major domestic opposition; it was the third largest member (by number of troops) in the 'coalition of the willing

' in Iraq.

Other Oceanic nations have contributed troops to outside conflicts, although the smallness of these countries and their militaries has meant that these contributions have been fairly minimal. The military participation of smaller Oceanic countries includes Fiji sending peacekeeping troops to Lebanon

in 1978 and the Sinai Peninsula

in 1981, and Tonga's sending of 45 soldiers to the Iraq War for several months.

Oceania

Oceania is a region centered on the islands of the tropical Pacific Ocean. Conceptions of what constitutes Oceania range from the coral atolls and volcanic islands of the South Pacific to the entire insular region between Asia and the Americas, including Australasia and the Malay Archipelago...

probably goes back thousands of years to the first human settlement in the region, little is known about war in Oceania until the arrival of Europeans. The introduction of firearms transformed conflict in the region; in some cases helping to unify regions and in others sparking large-scale tribal and civil wars. Force and the threat of force played a role in the annexation of most of Oceania to various European and American powers, but only in Australia and New Zealand did wars of conquest occur. Western Oceania was a major site of conflict in World War II as the Japanese Empire sought to expand southwards. Since 1945 the region has been mostly at peace, although Melanesia

Melanesia

Melanesia is a subregion of Oceania extending from the western end of the Pacific Ocean to the Arafura Sea, and eastward to Fiji. The region comprises most of the islands immediately north and northeast of Australia...

has suffered from Indonesia

Indonesia

Indonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

n expansionism in some areas and civil wars and coups in others. The Australian Defence Force

Australian Defence Force

The Australian Defence Force is the military organisation responsible for the defence of Australia. It consists of the Royal Australian Navy , Australian Army, Royal Australian Air Force and a number of 'tri-service' units...

is currently the largest military force in Oceania.

Pre-European warfare

University of Illinois at Chicago

The University of Illinois at Chicago, or UIC, is a state-funded public research university located in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its campus is in the Near West Side community area, near the Chicago Loop...

calculating that 87 per cent of tribal societies were at war more than once per year, and some 65 per cent of them were fighting continuously.http://www.troynovant.com/Franson/Keeley/War-Before-Civilization.html For instance, in Arnhem

Arnhem

Arnhem is a city and municipality, situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands. It is the capital of the province of Gelderland and located near the river Nederrijn as well as near the St. Jansbeek, which was the source of the city's development. Arnhem has 146,095 residents as one of the...

Land in northern Australia, a study of warfare among the Murngin people in the late-19th century found that over a 20-year period no less than 200 out of 800 men, or 25 percent of all adult males, had been killed in intertribal warfare.http://washingtontimes.com/books/20030816-105047-3673r.htm On the other hand, New Zealand historian James Belich

James Belich (historian)

James Christopher Belich, ONZM is a New Zealand revisionist historian, known for his work on the New Zealand Wars.Of Croatian descent, he was born in Wellington in 1956, the son of Sir James Belich, who later became Mayor of Wellington. He attended Onslow College.He gained an M.A...

cautions against the assumption that tribal societies were inevitably in a constant state of war, pointing out that oral histories tend to emphasise warfare rather than peace even if there is far more of the latter than the former, and that estimating the frequency of war based on the number of weapons and fortifications is like estimating the number of house fires based on the number of insurance policies. However it is clear that in most societies warriors were held in high esteem and that completely pacifist societies were very unusual. One exception was the Moriori

Moriori

Moriori are the indigenous people of the Chatham Islands , east of the New Zealand archipelago in the Pacific Ocean...

of the Chatham Islands

Chatham Islands

The Chatham Islands are an archipelago and New Zealand territory in the Pacific Ocean consisting of about ten islands within a radius, the largest of which are Chatham Island and Pitt Island. Their name in the indigenous language, Moriori, means Misty Sun...

.

A range of weapons were used in Oceania. These included the woomera

Woomera (spear-thrower)

A woomera is an Australian Aboriginal spear-throwing device used for when there is a greater distance to be overcome. It is highly efficient and made of wood. Similar to an atlatl, it enables a spear to travel much further than by arm strength alone...

and boomerang

Boomerang

A boomerang is a flying tool with a curved shape used as a weapon or for sport.-Description:A boomerang is usually thought of as a wooden device, although historically boomerang-like devices have also been made from bones. Modern boomerangs used for sport are often made from carbon fibre-reinforced...

in Australia, and the bow

Bow (weapon)

The bow and arrow is a projectile weapon system that predates recorded history and is common to most cultures.-Description:A bow is a flexible arc that shoots aerodynamic projectiles by means of elastic energy. Essentially, the bow is a form of spring powered by a string or cord...

in some parts of Melanesia and Polynesia. Nearly all Oceanic peoples had spears and clubs, although the Māori of New Zealand were unusual in having no distance weapons. Weapons could be very simple or elaborately crafted, with distance weapons in particular requiring a great deal of craftsmanship to be accurate. It has been estimated that Aboriginal spears were more accurate than nineteenth century European firearms.

Most pre-European conflicts in Oceania took place between peoples with a shared culture, and often language. However there were also wars between peoples of different cultures, for example in Australia and Papua New Guinea, each of which contains many different cultures, and in central Polynesia, where island groups are close enough for parties of war canoes to travel to other territories.

Impact of European contact

The arrival of Europeans in Oceania had dramatic consequences, especially in parts of the area which had no previous contact with Asia. In many cases European weapons, transport and sometimes troops massively upset an existing balance of power. One example of this was the New Zealand Musket WarsMusket Wars

The Musket Wars were a series of five hundred or more battles mainly fought between various hapū , sometimes alliances of pan-hapū groups and less often larger iwi of Māori between 1807 and 1842, in New Zealand.Northern tribes such as the rivals Ngāpuhi and Ngāti Whātua were the first to obtain...

in which iwi

Iwi

In New Zealand society, iwi form the largest everyday social units in Māori culture. The word iwi means "'peoples' or 'nations'. In "the work of European writers which treat iwi and hapū as parts of a hierarchical structure", it has been used to mean "tribe" , or confederation of tribes,...

(tribes) with musket

Musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded, smooth bore long gun, fired from the shoulder. Muskets were designed for use by infantry. A soldier armed with a musket had the designation musketman or musketeer....

s attacked iwi who lacked them. Serious warfare raged throughout New Zealand for nearly thirty years, only ending when all tribes had acquired muskets. The presence of European ships also affected Māori warfare, for example enabling Māori to travel to the Chatham Islands, where they almost wiped out the Moriori. The presence of firearms could also turn what would otherwise have been minor squabbles into full-scale wars. One such was the Nauruan Tribal War

Nauruan Tribal War

The Nauruan Tribal War was a War among the twelve indigenous tribes of Nauru between 1878 and 1888. By the end of the war about 500 people had died, around a third of the population.-Origins:...

, which lasted for a decade and ultimately resulted in the annexation of Nauru

Nauru

Nauru , officially the Republic of Nauru and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country in Micronesia in the South Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in Kiribati, to the east. Nauru is the world's smallest republic, covering just...

by Germany. In other parts of the Pacific, particular leaders were able to use their contacts with Europeans to unify their islands. One leader who did this was the Fijian chief Tanoa Visawaqa

Tanoa Visawaqa

Ratu Tanoa Visawaqa was a Fijian Chieftain who held the title Vunivalu of Bau. With Adi Savusavu, one of his nine wives, he was the father of Seru Epenisa Cakobau, who succeeded in unifying Fiji into a single kingdom.- Installation :...

who, in the 1840s, used arms purchased from a Swedish mercenary to subdue most of Western Fiji. Tonga was also united into a kingdom around this time.

Armed force, or the threat thereof, was sometimes used to gain European sovereignty over Oceanic nations. One example of this was the 'Bayonet Constitution

1887 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii

The 1887 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii was a legal document by anti-monarchists to strip the Hawaiian monarchy of much of its authority, initiating a transfer of power to American, European and native Hawaiian elites...

' of Hawai'i. This was not the only method of winning sovereignty. In some cases a treaty was peacefully agreed to, but even in these cases violence or the fear of it was often still a factor. For example New Zealand's Treaty of Waitangi

Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi is a treaty first signed on 6 February 1840 by representatives of the British Crown and various Māori chiefs from the North Island of New Zealand....

was presented to Māori partly as a way to prevent a French invasion and partly as a way to stop inter-tribal warfare; while Tonga became a British protected state as a result of an attempt to oust the Tongan king. In other parts of the region, such as Australia, European sovereignty was simply proclaimed without any attempt to win the consent of the indigenous peoples. In many cases, including those in which sovereignty had been ceded more or less voluntarily, force and the threat of force were required to maintain European dominance.

Wars of colonisation

Pa (Maori)

The word pā can refer to any Māori village or settlement, but in traditional use it referred to hillforts fortified with palisades and defensive terraces and also to fortified villages. They first came into being about 1450. They are located mainly in the North Island north of lake Taupo...

s, though on occasion warfare was more or less conventional and on other occasions both sides used guerrilla tactics. There was a distinct difference in scale - at the height of the New Zealand Land Wars

New Zealand land wars

The New Zealand Wars, sometimes called the Land Wars and also once called the Māori Wars, were a series of armed conflicts that took place in New Zealand between 1845 and 1872...

18,000 English troops were required, in addition to settler and "loyal native" forces to contain the belligerent minority of the well armed and militarily competent Māori. Nevertheless, in both cases 'native resistance' was eventually subdued although in Australia occasional fighting continued into the twentieth century.

World War I

Although World War I occurred almost entirely in Europe and the Middle East, Oceania was involved in a number of ways. British settlers and their descendants in Australia and New Zealand enthusiastically signed up to fight for their 'mother country', as did some Māori. Australian and New Zealand troops, joined together in ANZAC formations, fought and died in large numbers in the Gallipoli Campaign

Battle of Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the Dardanelles Campaign or the Battle of Gallipoli, took place at the peninsula of Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916, during the First World War...

, the Western Front

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

and in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign

Sinai and Palestine Campaign

The Sinai and Palestine Campaigns took place in the Middle Eastern Theatre of World War I. A series of battles were fought between British Empire, German Empire and Ottoman Empire forces from 26 January 1915 to 31 October 1918, when the Armistice of Mudros was signed between the Ottoman Empire and...

in the Middle East.

In Oceania itself, islands possessed by Germany were invaded by Japan (see Japan during World War I

Japan during World War I

Japan participated in ' from 1914 to 1918 as one of the major Entente Powers and played an important role in securing the sea lanes in South Pacific and Indian Oceans against the German Kaiserliche Marine...

), Australia (German New Guinea

German New Guinea

German New Guinea was the first part of the German colonial empire. It was a protectorate from 1884 until 1914 when it fell to Australia following the outbreak of the First World War. It consisted of the northeastern part of New Guinea and several nearby island groups...

and Nauru

Nauru

Nauru , officially the Republic of Nauru and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country in Micronesia in the South Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in Kiribati, to the east. Nauru is the world's smallest republic, covering just...

), and New Zealand (German Samoa

German Samoa

German Samoa was a German protectorate from 1900 to 1914, consisting of the islands of Upolu, Savai'i, Apolima and Manono, now wholly within the independent state Samoa, formerly Western Samoa...

), with little serious resistance apart from the Battle of Bita Paka

Battle of Bita Paka

The Battle of Bita Paka was fought south of Kabakaul, on the island of New Britain, and was a part of the invasion and subsequent occupation of German New Guinea by the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force shortly after the outbreak of the First World War...

in German New Guinea.

After the war the islands were granted to their new conquerors by the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

as mandated territories. In this way, Japan took control of the Mariana Islands

Mariana Islands

The Mariana Islands are an arc-shaped archipelago made up by the summits of 15 volcanic mountains in the north-western Pacific Ocean between the 12th and 21st parallels north and along the 145th meridian east...

, Caroline Islands

Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia in the eastern part of the group, and Palau at the extreme western end...

and Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands

The Republic of the Marshall Islands , , is a Micronesian nation of atolls and islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, just west of the International Date Line and just north of the Equator. As of July 2011 the population was 67,182...

, while Australia took over German New Guinea

German New Guinea

German New Guinea was the first part of the German colonial empire. It was a protectorate from 1884 until 1914 when it fell to Australia following the outbreak of the First World War. It consisted of the northeastern part of New Guinea and several nearby island groups...

and New Zealand took over German Samoa

German Samoa

German Samoa was a German protectorate from 1900 to 1914, consisting of the islands of Upolu, Savai'i, Apolima and Manono, now wholly within the independent state Samoa, formerly Western Samoa...

. Nauru

Nauru

Nauru , officially the Republic of Nauru and formerly known as Pleasant Island, is an island country in Micronesia in the South Pacific. Its nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in Kiribati, to the east. Nauru is the world's smallest republic, covering just...

was administered by the United Kingdom in conjunction with Australia and New Zealand.

World War II

The western Pacific was a major site of fighting between Japan and the United States-led Allies. Japan conquered most of Melanesia and South-East Asia, and brought the United States into the war by bombing the US possession of Hawaii at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor, known to Hawaiians as Puuloa, is a lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. Much of the harbor and surrounding lands is a United States Navy deep-water naval base. It is also the headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Fleet...

. The inhabitants of areas conquered by the Japanese were often harshly treated; for example 1,200 Nauruans were forcibly transported as labour to the Chuuk islands

Chuuk

Chuuk — formerly Truk, Ruk, Hogoleu, Torres, Ugulat, and Lugulus — is an island group in the south western part of the Pacific Ocean. It comprises one of the four states of the Federated States of Micronesia , along with Kosrae, Pohnpei, and Yap. Chuuk is the most populous of the FSM's...

, where 463 died. Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea , officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is a country in Oceania, occupying the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and numerous offshore islands...

was a major battleground, and the Japanese possessions taken from Germany during World War I were re-taken by the United States, with the Mariana Islands serving as a US bombing base. New Zealand and most of Polynesia remained relatively untouched by the war, apart from the sending of troops and the visits of American servicement on rest and recreation leave.

As with the First World War, New Zealand and Australia were enthusiastic defenders of Britain in World War II, and some other member countries of the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

also sent troops. New Zealand forces served primarily in Europe, fighting in Greece

Battle of Greece

The Battle of Greece is the common name for the invasion and conquest of Greece by Nazi Germany in April 1941. Greece was supported by British Commonwealth forces, while the Germans' Axis allies Italy and Bulgaria played secondary roles...

, North Africa

North African campaign

During the Second World War, the North African Campaign took place in North Africa from 10 June 1940 to 13 May 1943. It included campaigns fought in the Libyan and Egyptian deserts and in Morocco and Algeria and Tunisia .The campaign was fought between the Allies and Axis powers, many of whom had...

and Italy, but with some forces serving in Singapore

Battle of Singapore

The Battle of Singapore was fought in the South-East Asian theatre of the Second World War when the Empire of Japan invaded the Allied stronghold of Singapore. Singapore was the major British military base in Southeast Asia and nicknamed the "Gibraltar of the East"...

, Fiji

Colonial Fiji

The United Kingdom declined its first opportunity to annex Fiji in 1852. Ratu Seru Epenisa Cakobau had offered to cede the islands, subject to being allowed to retain his Tui Viti title, a condition unacceptable to both the British and to many of his fellow chiefs, who regarded him only as first...

, and in the Solomon Islands campaign

Solomon Islands campaign

The Solomon Islands campaign was a major campaign of the Pacific War of World War II. The campaign began with Japanese landings and occupation of several areas in the British Solomon Islands and Bougainville, in the Territory of New Guinea, during the first six months of 1942...

. Australian initially sent troops to Europe, most were recalled to the Pacific following Japan's push southward, which included air raids on Darwin and other parts of Australia

Japanese air attacks on Australia, 1942-43

Between February 1942 and November 1943, during the Pacific War, the Australian mainland, domestic airspace, offshore islands and coastal shipping were attacked at least 97 times by aircraft from the Imperial Japanese Navy and Imperial Japanese Army Air Force...

in 1942-43. Australian soldiers fought crucial battles along the Kokoda Track

Kokoda Track

The Kokoda Trail or Track is a single-file foot thoroughfare that runs overland — in a straight line — through the Owen Stanley Range in Papua New Guinea...

in Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea , officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is a country in Oceania, occupying the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and numerous offshore islands...

and in the Borneo campaign

Borneo campaign (1945)

The Borneo Campaign of 1945 was the last major Allied campaign in the South West Pacific Area, during World War II. In a series of amphibious assaults between 1 May and 21 July, the Australian I Corps, under General Leslie Morshead, attacked Japanese forces occupying the island. Allied naval and...

.

Post 1945

Throughout the second half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, Oceania was mostly peaceful. Exceptions to this was MelanesiaMelanesia

Melanesia is a subregion of Oceania extending from the western end of the Pacific Ocean to the Arafura Sea, and eastward to Fiji. The region comprises most of the islands immediately north and northeast of Australia...

(where there were attempts by Indonesia

Indonesia

Indonesia , officially the Republic of Indonesia , is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania. Indonesia is an archipelago comprising approximately 13,000 islands. It has 33 provinces with over 238 million people, and is the world's fourth most populous country. Indonesia is a republic, with an...

to extend its territory in the area), a civil war

Civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same nation state or republic, or, less commonly, between two countries created from a formerly-united nation state....

in Bougainville

Bougainville Province

The Autonomous Region of Bougainville, previously known as North Solomons, is an autonomous region in Papua New Guinea. The largest island is Bougainville Island , and the province also includes the island of Buka and assorted outlying islands including the Carterets...

and several coups in Fiji

Fiji

Fiji , officially the Republic of Fiji , is an island nation in Melanesia in the South Pacific Ocean about northeast of New Zealand's North Island...

. During this time many Pacific nations won their independence, usually peacefully. However a number of islands remained territories of European, Asian and American powers, and several were used as nuclear testing sites. In the 1970s, these activities became highly controversial. Meanwhile, several Oceanic countries, notably Australia and New Zealand, contributed combat and peacekeeping troops to a range of conflicts outside of Oceania.

.jpg)

Nuclear testing in Oceania

Due to its low population, Oceania was a popular location for atmospheric and underground nuclear testsUnderground nuclear testing

Underground nuclear testing refers to test detonations of nuclear weapons that are performed underground. When the device being tested is buried at sufficient depth, the explosion may be contained, with no release of radioactive materials to the atmosphere....

. Tests were conducted in various locations by the United Kingdom (Operation Grapple

Operation Grapple

Operation Grapple, and operations Grapple X, Grapple Y and Grapple Z, were the names of British nuclear tests of the hydrogen bomb. They were held 1956—1958 at Malden Island and Christmas Island in the central Pacific Ocean. Nine nuclear detonations took place during the trials, resulting in...

and Operation Antler), the United States (Bikini atoll

Bikini atomic experiments

The Bikini Atomic Experiments were a series of nuclear and thermonuclear tests conducted on Bikini Atoll in the Bikini Islands. The experiments were part of the United States' research into the full effects of the atomic bomb, including post-detonation radioactive fallout...

and the Marshall Islands

Pacific Proving Grounds

The Pacific Proving Grounds was the name used to describe a number of sites in the Marshall Islands and a few other sites in the Pacific Ocean, used by the United States to conduct nuclear testing at various times between 1946 and 1962...

) and France (Moruroa

Moruroa

Moruroa , also historically known as Aopuni, is an atoll which forms part of the Tuamotu Archipelago in French Polynesia in the southern Pacific Ocean...

), often with devastating consequences for the inhabitants. In 1954, for example, fallout

Nuclear fallout

Fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and shock wave have passed. It commonly refers to the radioactive dust and ash created when a nuclear weapon explodes...

from the American Castle Bravo

Castle Bravo

Castle Bravo was the code name given to the first U.S. test of a dry fuel thermonuclear hydrogen bomb device, detonated on March 1, 1954 at Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands, as the first test of Operation Castle. Castle Bravo was the most powerful nuclear device ever detonated by the United States ,...

hydrogen bomb test in the Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands

The Republic of the Marshall Islands , , is a Micronesian nation of atolls and islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, just west of the International Date Line and just north of the Equator. As of July 2011 the population was 67,182...

was such that the inhabitants of the Rongelap Atoll were forced to abandon their island. Three years later the islanders were allowed to return, but suffered abnormally high levels of cancer. They were evacuated again in 1985 and in 1996 given $45 million in compensation. A series of British tests were also conducted in the 1950s at Maralinga

British nuclear tests at Maralinga

British nuclear tests at Maralinga occurred between 1955 and 1963 at the Maralinga site, part of the Woomera Prohibited Area, in South Australia. A total of seven major nuclear tests were performed, with approximate yields ranging from 1 to 27 kilotons of TNT equivalent...

in South Australia

South Australia

South Australia is a state of Australia in the southern central part of the country. It covers some of the most arid parts of the continent; with a total land area of , it is the fourth largest of Australia's six states and two territories.South Australia shares borders with all of the mainland...

, forcing the removal of the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara peoples from their ancestral homelands. The atoll of Moruroa

Moruroa

Moruroa , also historically known as Aopuni, is an atoll which forms part of the Tuamotu Archipelago in French Polynesia in the southern Pacific Ocean...

in French Polynesia

French Polynesia

French Polynesia is an overseas country of the French Republic . It is made up of several groups of Polynesian islands, the most famous island being Tahiti in the Society Islands group, which is also the most populous island and the seat of the capital of the territory...

became notorious as a site of French nuclear testing, primarily because tests were carried out there after most Pacific testing had ceased. These tests were opposed by most other nations in Oceania. The last atmospheric test was conducted in 1974, and the last underground test in 1996.

Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation 1962-1966

This was an intermittent battle over the future of the island of Borneo, between Malaysia and Indonesia from 1962 to 1966. Indonesia opposed the consolidation of MalayaFederation of Malaya

The Federation of Malaya is the name given to a federation of 11 states that existed from 31 January 1948 until 16 September 1963. The Federation became independent on 31 August 1957...

with the British territories of Sarawak

Sarawak

Sarawak is one of two Malaysian states on the island of Borneo. Known as Bumi Kenyalang , Sarawak is situated on the north-west of the island. It is the largest state in Malaysia followed by Sabah, the second largest state located to the North- East.The administrative capital is Kuching, which...

and British North Borneo into a new nation of Malaysia. Indonesia felt that this would increase British power in the region and threaten Indonesian independence. From 1963 Indonesian troops began conducting guerrilla raids into Malaysia, and British, Australian and New Zealand troops were brought in. In 1965 there was an attempted coup in Indonesia, and the subsequent power struggles reduced that country's ability to conduct external warfare. A peace treaty was signed the following year.

East Timor

.svg.png)

In 1975, East Timor

East Timor

The Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, commonly known as East Timor , is a state in Southeast Asia. It comprises the eastern half of the island of Timor, the nearby islands of Atauro and Jaco, and Oecusse, an exclave on the northwestern side of the island, within Indonesian West Timor...

declared itself independent, following the withdrawal of its coloniser Portugal. Nine days later the area was invaded by Indonesia. Because the East Timorese FRETILIN party had some communist support, the Indonesia government was able to portray its actions as anti-communist, and thus won the backing of the United States and Australia. A detailed statistical report prepared for the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor

Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor

The Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor was an independent truth commission established in East Timor in 2001 under the UN Transitional Administration in East Timor and charged to “inquire into human rights violations committed...

cited a lower range of 102,800 conflict-related deaths in the Indonesian occupation period 1974-1999, namely, approximately 18,600 killings and 84,200 'excess' deaths from hunger and illness. Amnesty International

Amnesty International

Amnesty International is an international non-governmental organisation whose stated mission is "to conduct research and generate action to prevent and end grave abuses of human rights, and to demand justice for those whose rights have been violated."Following a publication of Peter Benenson's...

estimates the death toll to be about 200,000. A guerrilla campaign against Indonesia was carried out by Falintil

Falintil

Falintil originally began as the military wing of the political party FRETILIN of East Timor. It was established on 20 August 1975 in response to FRETILIN’s political conflict with the Timorese Democratic Union ....

throughout the period of occupation.

In 1999 a United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

supervised referendum

Referendum

A referendum is a direct vote in which an entire electorate is asked to either accept or reject a particular proposal. This may result in the adoption of a new constitution, a constitutional amendment, a law, the recall of an elected official or simply a specific government policy. It is a form of...

was held as a result of an agreement between Indonesia, Portugal and the United States. The East Timorese voted for full independence. The Indonesian military backed militia attacks within East Timor, and a peacekeeping force consisting mostly of Australian and New Zealand troops was sent in. East Timor's independence was recognised in 2006, but since then there have been two major outbreaks of violence, each requiring the intervention of UN-backed troops.

Fijian coups

Fiji has suffered several coups d'état: military in 1987 and 2006 and civilian in 2000. All were ultimately due to ethnic tension between indigenous FijiansFijian people

Fijian people are the major indigenous people of the Fiji Islands, and live in an area informally called Melanesia. The Fijian people are believed to have arrived in Fiji from western Melanesia approximately 3,500 years ago, though the exact origins of the Fijian people are unknown...

and Indo-Fijians, who originally came to the islands as indentured labour in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. The 1987 coup followed the election of a multi-ethnic coalition, which Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel is a rank of commissioned officer in the armies and most marine forces and some air forces of the world, typically ranking above a major and below a colonel. The rank of lieutenant colonel is often shortened to simply "colonel" in conversation and in unofficial correspondence...

Sitiveni Rabuka

Sitiveni Rabuka

Major-General Sitiveni Ligamamada Rabuka, OBE, MSD, OStJ, is best known as the instigator of two military coups that shook Fiji in 1987. He was later democratically elected the third Prime Minister, serving from 1992 to 1999...

overthrew, claiming racial discrimination against ethnic Fijians. The coup was denounced by the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

and Fiji was expelled from the Commonwealth of Nations

Commonwealth of Nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, normally referred to as the Commonwealth and formerly known as the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organisation of fifty-four independent member states...

.

The 2000 coup was essentially a repeat of the 1987 affair, although it was led by civilian George Speight

George Speight

George Speight , occasionally known as Ilikimi Naitini, was the principal instigator of the Fiji coup of 2000, in which he kidnapped thirty-six government officials and held them from May 19, 2000 to July 13, 2000...

, apparently with military support. Commodore

Commodore (rank)

Commodore is a military rank used in many navies that is superior to a navy captain, but below a rear admiral. Non-English-speaking nations often use the rank of flotilla admiral or counter admiral as an equivalent .It is often regarded as a one-star rank with a NATO code of OF-6, but is not always...

Frank Bainimarama

Frank Bainimarama

Commodore Josaia Voreqe Bainimarama, CF, MSD, OStJ, Fijian Navy, known commonly as Frank Bainimarama and sometimes by the chiefly title Ratu , is a Fijian naval officer and politician. He is the Commander of the Fijian Military Forces and, as of April 2009, Prime Minister...

, who was opposed to Speight, then took over and appointed a new Prime Minister. Speight was later tried and convicted for treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

. Many indigenous Fijians were unhappy at the treatment of Speight and his supporters, feeling that the coup had been legitimate. In 2006 the Fijian parliament attempted to introduce a series of bills which would have, amongst other things, pardoned those involved in the 2000 coup. Bainimarama, concerned that the legal and racial injustices of the previous coups would be perpetuated, staged his own coup. It was internationally condemned, and Fiji again suspended from the Commonwealth.

Bougainville conflict

From 1975, there were attempts by the Bougainville ProvinceBougainville Province

The Autonomous Region of Bougainville, previously known as North Solomons, is an autonomous region in Papua New Guinea. The largest island is Bougainville Island , and the province also includes the island of Buka and assorted outlying islands including the Carterets...

to secede from Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea , officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is a country in Oceania, occupying the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and numerous offshore islands...

. These were resisted by Papua New Guinea primarily because of the presence in Bougainville of the Panguna mine, which was vital to Papua New Guinea's economy. The Bougainville Revolutionary Army

Bougainville Revolutionary Army

The Bougainville Revolutionary Army was formed in 1988 by Bougainvilleans seeking independence from Papua New Guinea .BRA leaders argue that Bougainville is ethnically part of the Solomon Islands and has not profited from the extensive mining that has occurred on the island...

began attacking the mine in 1988, forcing its closure the following year. Further BRA activity led to the declaration of a state of emergency

State of emergency

A state of emergency is a governmental declaration that may suspend some normal functions of the executive, legislative and judicial powers, alert citizens to change their normal behaviours, or order government agencies to implement emergency preparedness plans. It can also be used as a rationale...

and the conflict continued until about 2005, when successionist leader and self-proclaimed King of Bougainville Francis Ona

Francis Ona

Francis Ona was a Bougainville secessionist leader who led an uprising against the Government of Papua New Guinea, motivated at least initially by his concerns over the operation of the Panguna mine by Bougainville Copper, a subsidiary of Rio Tinto Group...

died of malaria. Peacekeeping troops led by Australia have been in the region since the late 1990s, and a referendum on independence will be held in the 2010s.

Participation in non-Oceanic conflicts

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

, Vietnam

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

, Gulf

Gulf War

The Persian Gulf War , commonly referred to as simply the Gulf War, was a war waged by a U.N.-authorized coalition force from 34 nations led by the United States, against Iraq in response to Iraq's invasion and annexation of Kuwait.The war is also known under other names, such as the First Gulf...

and Afghanistan War

War in Afghanistan (2001–present)

The War in Afghanistan began on October 7, 2001, as the armed forces of the United States of America, the United Kingdom, Australia, and the Afghan United Front launched Operation Enduring Freedom...

s, and Australia also participated in the Iraq War. Neither is a major military power in world terms, preferring to join with coalition operations, but both possess modern and well trained defense forces. Both have made significant contributions to international peacekeeping

Peacekeeping

Peacekeeping is an activity that aims to create the conditions for lasting peace. It is distinguished from both peacebuilding and peacemaking....

operations, although their focus has tended to be within Oceania.

Following the fall of Singapore in World War II, Australia and New Zealand both came to the realisation that Britain could no longer protect her former colonies in the Pacific. Accordingly, both countries desired an alliance with the United States and in 1951 the ANZUS

ANZUS

The Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty is the military alliance which binds Australia and New Zealand and, separately, Australia and the United States to cooperate on defence matters in the Pacific Ocean area, though today the treaty is understood to relate to attacks...

Treaty was signed between the three countries. This meant that if a Treaty partner came under attack, the other two would be required to come to its aid. Although none of the ANZUS partners came under attack, (until, arguably, September 11, 2001, or the Rainbow Warrior bombing

Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior

The sinking of the Rainbow Warrior, codenamed Opération Satanique, was an operation by the "action" branch of the French foreign intelligence services, the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure , carried out on July 10, 1985...

), both Australia and New Zealand nonetheless felt obliged to help America in its Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

conflicts in Korea and Vietnam. Because of its close proximity to Asia, Australia has always been more worried than New Zealand about an invasion from Asia, and has thus been a more enthusiastic partner with America. New Zealand's contribution to the Vietnam War was small, whereas Australia went as far as to introduce conscription

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

. By the 1970s, many people in both countries had begun to oppose the American alliance, not least because of Vietnam. America's role as a major nuclear power was also a strong factor in anti-American sentiment. In 1984 New Zealand enacted a ban on nuclear armed or powered ships in its waters, essentially preventing most American naval ships from visiting New Zealand. As a result, America suspended it's treaty obligations to New Zealand under the ANZUS alliance. Despite this, New Zealand committed small numbers of soldiers to the 1991 Gulf and Afghanistan Wars, and has sent engineering units to Iraq. Australia has remained a strong supporter of America, despite major domestic opposition; it was the third largest member (by number of troops) in the 'coalition of the willing

Coalition of the willing

The term coalition of the willing is a post-1990 political phrase used to collectively describe participants in military or military-humanitarian interventions for which the United Nations Security Council cannot agree to mount a full UN peacekeeping operation...

' in Iraq.

Other Oceanic nations have contributed troops to outside conflicts, although the smallness of these countries and their militaries has meant that these contributions have been fairly minimal. The military participation of smaller Oceanic countries includes Fiji sending peacekeeping troops to Lebanon

Lebanon

Lebanon , officially the Republic of LebanonRepublic of Lebanon is the most common term used by Lebanese government agencies. The term Lebanese Republic, a literal translation of the official Arabic and French names that is not used in today's world. Arabic is the most common language spoken among...

in 1978 and the Sinai Peninsula

Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula or Sinai is a triangular peninsula in Egypt about in area. It is situated between the Mediterranean Sea to the north, and the Red Sea to the south, and is the only part of Egyptian territory located in Asia as opposed to Africa, effectively serving as a land bridge between two...

in 1981, and Tonga's sending of 45 soldiers to the Iraq War for several months.