Moroccan Arabic

Encyclopedia

Moroccan Arabic is the variety of Arabic

spoken in the Arabic

-speaking areas of Morocco

. For official communications, the government and other public bodies use Modern Standard Arabic, as is the case in most Arabic-speaking countries. A mixture of French

and Moroccan Arabic is used in business. It is within the Maghrebi Arabic dialect continuum

.

Native speakers typically consider Moroccan Arabic a dialect

Native speakers typically consider Moroccan Arabic a dialect

because it is not a literary language

and because it lacks prestige compared to Standard Arabic . It differs from Standard Arabic in phonology, lexicon, and syntax, and has been influenced by Berber

(mainly in its pronunciation, and grammar), French

and Spanish

.

Moroccan Arabic continues to evolve by integrating new French or English words, notably in technical fields, or by replacing old French and Spanish ones with Standard Arabic words within some circles.

Darija

(which means "dialect") can be divided into two groups:

A similar phenomenon can be observed in Algerian Arabic

and Tunisian Arabic

.

. It is grammatically simpler, and has a less voluminous vocabulary than Classical Arabic. It has also integrated many Berber

, French

and Spanish

words.

There is a relatively clear-cut division between Moroccan Arabic and Standard Arabic, and most uneducated Moroccans do not understand Modern Standard Arabic. Depending on cultural background and degree of literacy, those who do speak Modern Standard Arabic may prefer to use Arabic words instead of their French or Spanish borrowed counterparts, while upper and educated classes often adopt code-switching

between French and Moroccan Arabic. As elsewhere in the world, how someone speaks and what words or language they use is often an indicator of their social class

.

accent, or with Berber phoneme

s. This is similar to the phenomenon in the south of France where some pronounce French with Occitan phonemes.

Some dialects are more conservative in their treatment of short vowels. For example, some dialects allow /ŭ/ in more positions. Dialects of the Sahara, and eastern dialects near the border of Algeria, preserve a distinction between /ă/ and /ĭ/ and allow /ă/ to appear at the beginning of a word, e.g. /ăqsˤărˤ/ "shorter" (standard /qsˤərˤ/), /ătˤlăʕ/ "go up!" (standard /tˤlăʕ/ or /tˤləʕ/), /ăsˤħab/ "friends" (standard /sˤħab/).

Long /a/, /i/ and /u/ are maintained as semi-long vowels, which are substituted for both short and long vowels in most borrowings from Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). Long /a/, /i/ and /u/ also have many more allophones than in most other dialects; in particular, /a/, /i/, /u/ appear as [ɑ], [e], [o] in the vicinity of emphatic consonants, but [æ], [i], [u] elsewhere. (Most other Arabic dialects only have a similar variation for the phoneme /a/.) In some dialects, such as that of Marrakech

, front-rounded and other allophones also exist.

Emphatic spreading (i.e. the extent to which emphatic consonants affect nearby vowels) occurs much less than in many other dialects. Emphasis spreads fairly rigorously towards the beginning of a word and into prefixes, but much less so towards the end of a word. Emphasis spreads consistently from a consonant to a directly following vowel, and less strongly when separated by an intervening consonant, but generally does not spread rightwards past a full vowel. For example, /bidˤ-at/ [bedɑt͡s] "eggs" (/i/ and /a/ both affected), /tˤʃaʃ-at/ [tʃɑʃæt͡s] "sparks" (rightmost /a/ not affected), /dˤrˤʒ-at/ [drˤʒæt͡s] "stairs" (/a/ usually not affected), /dˤrb-at-u/ [drˤbat͡su] "she hit him" (with [a] variable but tending to be in between [ɑ] and [æ]; no effect on /u/), /tˤalib/ [tɑlib] "student" (/a/ affected but not /i/). Contrast, for example, Egyptian Arabic

, where emphasis tends to spread forward and backward to both ends of a word, even through several syllables.

Emphasis is audible mostly through its effects on neighboring vowels or syllabic consonants, and through the differing pronunciation of /t/ [t͡s] and /tˤ/ [t]. Actual pharyngealization of "emphatic" consonants is weak and may be absent entirely. In contrast with some dialects, vowels adjacent to emphatic consonants are pure; there is no diphthong-like transition between emphatic consonants and adjacent front vowels.

or Modern Standard Arabic), and there is no universally standard written system. There is also a loosely standardized Latin system used for writing Moroccan Arabic in electronic media, such as texting and chat, often based on sound-letter correspondences from French ('ch' for English 'sh', 'ou' for English 'u', etc.). It is extremely rare to find Moroccan Arabic written in the Arabic script, which is reserved for Standard Arabic. However, most systems used for writing Moroccan Arabic in linguistic works largely agree among each other, and such a system is used here.

Long (aka "stable") vowels /a/, /i/, /u/ are written a, i, u. e represents /ə/ and o represents /ŭ/ (see section on phonology, above). ă is used for /ă/ in speakers who still have this phoneme in the vicinity of pharyngeal /ʕ/ and /ħ/. ă, ĭ, and o are also used for ultra-short vowels used by educated speakers for the short vowels of some recent borrowings from MSA.

Note that in practice, /ə/ is usually deleted when not the last vowel of a word, and hence some authors prefer a transcription without this vowel, e.g. ka-t-ktb-u "You're (pl) writing" instead of ka-t-ketb-u. Others (like Richard Harrell in his reference grammar of Moroccan Arabic) maintain the e; but it never occur in an open syllable (followed by a single consonant and a vowel). Instead the e is transposed with the preceding (sometimes geminated) consonant, which ends up following the e; this is known as inversion.

y represents /j/.

ḥ and ` represent pharyngeal /ħ/ and /ʕ/.

ġ and x represent velar /ɣ/ and /x/.

ṭ, ḍ, ṣ, ẓ, ṛ, ḷ represent emphatic /tˤ, dˤ, sˤ, zˤ, rˤ, lˤ/.

š, ž represent hushing /ʃ, ʒ/.

, also practice code-switching

(moving from Moroccan Arabic to French

and the other way around as it can be seen in the movie Marock

). In the northern parts of Morocco, as in Tangier

, it is common for code-switching to occur between Moroccan Arabic and Spanish

, as Spain

had previously controlled part of the region

, and also continues to possess the territories of Ceuta

and Melilla

in North Africa bordering only Morocco. On the other hand, some educated Moroccans, particularly those sympathetic to the ideas of Arab nationalism

, generally attempt to avoid French and Spanish influences (save those Spanish influences from al-Andalus

) on their speech, even when speaking in darija; consequently, their speech tends to resemble old Andalusi Arabic

and pre-occupation Maghrebi.

, French

and Spanish

words. Spanish words typically entered Moroccan Arabic earlier than French ones. Some words might have been brought by Moriscos who spoke Andalusi Arabic

which was influenced by Spanish (Castilian), an example being the typical Andalusian

dish Pastilla

. Other influences have been the result of the Spanish protectorate

in Spanish Morocco

. French words came with the French protectorate

(1912–1956). Recently, young Moroccans have started to use English words in their dialects.

There are noticeable lexical differences between Moroccan Arabic and most other dialects. Some words are essentially unique to Moroccan Arabic: e.g. daba "now". Many others, however, are characteristic of Maghrebi Arabic as a whole, including both innovations and unusual retentions of Classical vocabulary that has disappeared elsewhere such as hbeṭ "go down" from Classical habaṭ. Others distinctives are shared with Algerian Arabic

such as hḍeṛ "talk", from Classical hadhar "babble" and temma "there" from Classical thamma.

There are a number of Moroccan Arabic dictionaries in existence, including (in chronological order):

brought by Moriscos when they were expelled from Spain

following the Christian Reconquest

.

, El Jadida

, and Tangier

)

.

The stem of the Moroccan verb for "to write" is kteb.

The past tense of kteb "write" is as follows:

I wrote: kteb-t

You wrote: kteb-ti

He/it wrote: kteb (kteb can also be an order to write, e.g.: kteb er-rissala: Write the letter)

She/it wrote: ketb-et

We wrote: kteb-na

You (pl) wrote: kteb-tu

They wrote: ketb-u

Note that the stem kteb turns into ketb before a vowel suffix, due to the process of inversion described above.

The present tense of kteb "write" is as follows:

I'm writing: ka-ne-kteb

You're (masculine) writing: ka-te-kteb

You're (feminine) writing: ka-t-ketb-i

He's/it's writing: ka-ye-kteb

She's/it's writing: ka-te-kteb

We're writing: ka-n-ketb-u

You're (pl) writing: ka-t-ketb-u

They're writing: ka-y-ketb-u

Note that the stem kteb turns into ketb before a vowel suffix, due to the process of inversion described above. Between the prefix ka-n-, ka-t-, ka-y- and the stem kteb, an e vowel appears, but not between the prefix and the transformed stem ketb, due to the same restriction that produces inversion.

In the north, "youre writing" is always ka-de-kteb, regardless of whom you are speaking to.

This is also the case of de in de-kteb, as northerners prefer to use de and southerners prefer using te.

Instead of the prefix ka, some speakers prefer the use of ta (e.g. ta-ne-kteb "I'm writing"). The co-existence of these two prefixes is due to historical differences. In general ka is more used in the north and ta in the south. In some regions like the east (Oujda) the majority of speakers don't use any preverb (ne-kteb, te-kteb, y-kteb, etc.).

To form the future tense, just remove the prefix ka-/ta- and replace it with the prefix ġa-, ġad- or ġadi instead (e.g. ġa-ne-kteb "I will write", ġad-ketb-u (north) or ġadi t-ketb-u "You (pl) will write").

For the subjunctive and infinitive, just remove the ka- (e.g. bġit ne-kteb "I want to write", bġit te-kteb "I want you to write").

The imperative is conjugated with the suffixes of the present tense but without any prefixes or preverbs:

kteb "Write! (masc. sing.)"

ketb-i "Write! (fem. sing.)"

ketb-u "Write! (pl.)"

One characteristic of Moroccan syntax which it shares with other North African varieties as well as some southern Levantine dialect areas is in the two-part negative verbal circumfix /ma-...-ʃi/.

/ma-/ comes from the Classical Arabic negator /ma/. /-ʃi/ is a development of Classical /ʃayʔ/ "thing". The development of a circumfix is similar to the French circumfix ne ... pas, where ne comes from Latin non "not" and pas comes from Latin passus "step". (Originally, pas would have been used specifically with motion verbs, as in "I didn't walk a step", and then was generalized to other verbs.)

The negative circumfix surrounds the entire verbal composite including direct and indirect object pronouns:

"he didn't write them to me" "he doesn't write them to me" "he won't write them to me" "didn't he write them to me?" "doesn't he write them to me?" "won't he write them to me?"

Note that future-tense and interrogative sentences use the same /ma-...-ʃi/ circumfix (unlike, for example, in Egyptian Arabic).

Also, unlike in Egyptian Arabic, there are no phonological changes to the verbal cluster as a result of adding the circumfix. In Egyptian Arabic, adding the circumfix can trigger stress shifting, vowel lengthening and shortening, elision when /ma-/ comes into contact with a vowel, addition or deletion of a short vowel, etc. However, none of these occur in Moroccan Arabic (MA):

Negative pronouns such as walu "nothing", ḥta ḥaja "nothing" and ḥta waḥed "nobody" could be added to the sentence without ši as a suffix.

Examples:

Note: wellah ma-ne-kteb could be a response to a command to write kteb, while wellah ma-ġa-ne-kteb could be an answer to a question like waš ġa-te-kteb? "Are you going to write?" .

In the north, "youre writing" is always ka-de-kteb, regardless of whom you are speaking to.

This is also the case of de in de-kteb, as northerners prefer to use de and southerners prefer using te.

Instead of the prefix ka, some speakers prefer the use of ta (e.g. ta-ne-kteb "I'm writing"). The co-existence of these two prefixes is due to historical differences. In general ka is more used in the north and ta in the south. In some regions like the east (Oujda) the majority of speakers don't use any preverb (ne-kteb, te-kteb, y-kteb, etc.).

In Moroccan Arabic, the word order doesn't change for negative questions in the northern parts of Morocco, but in the western areas and other regions, the word order is preferably changed. The pronoun waš could be added in the beginning of the sentence, although it rarely changes the meaning of it. The prefix ma can rarely be removed when asking a question in a fast way.

Examples:

A ka can be added in the beginning of the sentence when asking a question in an angry or surprised way. In this case, waš can't be added.

Examples:

, intensive

, passive

or reflexive

.

Each particular lexical verb is specified by two stems, one used for the past tense and one used for non-past tenses along with subjunctive

and imperative

moods. To the former stem, suffixes are added to mark the verb for person, number and gender, while to the latter stem, a combination of prefixes and suffixes are added. (Very approximately, the prefixes specify the person and the suffixes indicate number and gender.) The third person masculine singular past tense form serves as the "dictionary form" used to identify a verb, similar to the infinitive

in English. (Arabic has no infinitive.) For example, the verb meaning "write" is often specified as kteb, which actually means "he wrote". In the paradigms below, a verb will be specified as kteb/ykteb (where kteb means "he wrote" and ykteb means "he writes"), indicating the past stem (kteb-) and non-past stem (also -kteb-, obtained by removing the prefix y-).

The verb classes in Arabic are formed along two axes. The first or derivational axis (described as "form I", "form II", etc.) is used to specify grammatical concepts such as causative

, intensive

, passive

or reflexive

, and mostly involves varying the consonants of a stem form. For example, from the root K-T-B "write" is derived form I kteb/ykteb "write", form II ketteb/yketteb "cause to write", form III kateb/ykateb "correspond with (someone)", etc. The second or weakness axis (described as "strong", "weak", "hollow", "doubled" or "assimilated") is determined by the specific consonants making up the root—especially, whether a particular consonant is a W or Y—and mostly involves varying the nature and location of the vowels of a stem form. For example, so-called weak verbs have a W or Y as the last root consonant, which is reflected in the stem as a final vowel instead of a final consonant (e.g. rˤma/yrˤmi "throw" from R-M-Y). Meanwhile, hollow verbs are usually caused by a W or Y as the middle root consonant, and the stems of such verbs have a full vowel (/a/, /i/ or /u/) before the final consonant, oftentimes along with only two consonants (e.g. ʒab/yʒib "bring" from ʒ-Y-B).

When speaking of the weakness axis, it is important to distinguish between strong, weak, etc. stems and strong, weak, etc. roots. For example, X-W-F is a hollow root, but the corresponding form II stem xuwwef/yxuwwef "frighten" is a strong stem. In particular:

In this section all verb classes and their corresponding stems are listed, excluding the small number of irregular verbs described above. Verb roots are indicated schematically using capital letters to stand for consonants in the root:

Hence, the root F-M-L stands for all three-consonant roots, and F-S-T-L stands for all four-consonant roots. (Traditional Arabic grammar uses F-ʕ-L and F-ʕ-L-L, respectively, but the system used here appears in a number of grammars of spoken Arabic dialects and is probably less confusing for English speakers, since the forms are easier to pronounce than those involving /ʕ/.)

The following table lists the prefixes and suffixes to be added to mark tense, person, number and gender, and the stem form to which they are added. The forms involving a vowel-initial suffix, and corresponding stem PAv or NPv, are highlighted in silver. The forms involving a consonant-initial suffix, and corresponding stem PAc, are highlighted in gold. The forms involving no suffix, and corresponding stem PA0 or NP0, are unhighlighted.

The following table lists the verb classes along with the form of the past and non-past stems, active and passive participles, and verbal noun, in addition to an example verb for each class.

Notes:

Example: kteb/ykteb "write"

Some comments:

Example: kteb/ykteb "write": non-finite forms

Example: dker/ydker "mention"

This paradigm differs from kteb/ykteb in the following ways:

Reduction and assimilation occur as follows:

Examples:

Example: xrˤeʒ/yxrˤoʒ "go out"

Example: beddel/ybeddel "teach"

Boldfaced forms indicate the primary differences from the corresponding forms of kteb, which apply to many classes of verbs in addition to form II strong:

Example: sˤaferˤ/ysˤaferˤ "travel"

The primary differences from the corresponding forms of beddel (shown in boldface) are:

Example: ttexleʕ/yttexleʕ "get scared"

Example: nsa/ynsa "forget"

The primary differences from the corresponding forms of kteb (shown in boldface) are:

Example: rˤma/yrˤmi "throw"

This verb type is quite similar to the weak verb type nsa/ynsa. The primary differences are:

Verbs other than form I behave as follows in the non-past:

Examples:

Hollow have a W or Y as the middle root consonant. Note that for some forms (e.g. form II and form III), hollow verbs are conjugated as strong verbs (e.g. form II ʕeyyen/yʕeyyen "appoint" from ʕ-Y-N, form III ʒaweb/yʒaweb "answer" from ʒ-W-B).

Example: baʕ/ybiʕ "sell"

This verb works much like beddel/ybeddel "teach". Like all verbs whose stem begins with a single consonant, the prefixes differ in the following way from those of regular and weak form I verbs:

In addition, the past tense has two stems: beʕ- before consonant-initial suffixes (first and second person) and baʕ- elsewhere (third person).

Example: ʃaf/yʃuf "see"

This verb class is identical to verbs such as baʕ/ybiʕ except in having stem vowel /u/ in place of /i/.

Doubled verbs have the same consonant as middle and last root consonant, e.g. ɣabb/yiħebb "love" from Ħ-B-B.

Example: ħebb/yħebb "love"

This verb works much like baʕ/ybiʕ "sell". Like that class, it has two stems in the past, which are ħebbi- before consonant-initial suffixes (first and second person) and ħebb- elsewhere (third person). Note that /i-/ was borrowed from the weak verbs; the Classical Arabic equivalent form would be *ħabáb-, e.g. *ħabáb-t.

Some verbs have /o/ in the stem: koħħ/ykoħħ "cough".

As for the other forms:

"Doubly weak" verbs have more than one "weakness", typically a W or Y as both the second and third consonants. This term is in fact a misnomer, as such verbs actually behave as normal weak verbs (e.g. ħya/yħya "live" from Ħ-Y-Y, quwwa/yquwwi "strengthen" from Q-W-Y, dawa/ydawi "treat, cure" from D-W-Y).

The irregular verbs are as follows:

and modern words. However, in recent years constant exposure to revived classical forms on television and in print media and a certain desire among many Moroccans for a revitalization of an Arab

identity has inspired many Moroccans to integrate words from Standard Arabic, replacing their French or Spanish counterparts or even speaking in Modern Standard Arabic while keeping the Moroccan accent

to sound less pedantic. This phenomenon mostly occurs among literate people.

Though rarely written, Moroccan Arabic is currently undergoing an unexpected and pragmatic revival. It is now the preferred language in Moroccan chat rooms or for sending SMS

, using Arabic Chat Alphabet

composed of Latin letters supplemented with the numbers 2, 3, 5, 7 and 9 for coding specific Arabic sounds as is the case with other Arabic speakers.

The language continues to evolve quickly as can be noted when consulting the Colin dictionary. Many words and idiomatic expressions recorded between 1921 and 1977 are now obsolete.

has evolved from Vulgar Latin

, Moroccan Arabic is considered as a language of low prestige whereas it is Modern Standard Arabic that is used in more formal contexts. While Moroccan Arabic is the mother tongue of nearly twenty million people in Morocco it is rarely used in written form. This situation may explain in part the high illiteracy rates in Morocco.

This situation is not specific to Morocco but occurs in all Arabic-speaking countries. The French Arabist

William Marçais coined in 1930 the term diglossie (diglossia

) to describe this situation, where two (often) closely related languages co-exist, one of high prestige, which is generally used by the government and in formal texts, and one of low prestige, which is usually the spoken vernacular

tongue.

. In the troubled and autocratic Morocco of the 70s (known as the years of lead), the legendary Nass El Ghiwane

band wrote beautiful and allusive lyrics in Moroccan Arabic which were very appealing to the youth even in other Maghreb

countries.

Another interesting movement is the development of an original rap music

scene, which explores new and innovative usages of the language.

s, their aim is to bring information to people with a low level of education

. From September 2006 to October 2010, Telquel Magazine had a Moroccan Arabic edition Nichane

. There is also a free weekly magazine that is totally written in "standard" Moroccan dialect: Khbar Bladna, i.e. 'News of our country'.

Varieties of Arabic

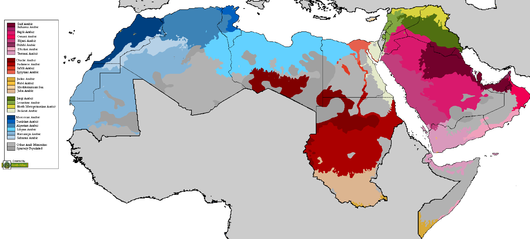

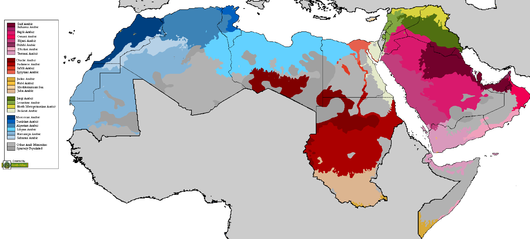

The Arabic language is a Semitic language characterized by a wide number of linguistic varieties within its five regional forms. The largest divisions occur between the spoken languages of different regions. The Arabic of North Africa, for example, is often incomprehensible to an Arabic speaker...

spoken in the Arabic

Arabic language

Arabic is a name applied to the descendants of the Classical Arabic language of the 6th century AD, used most prominently in the Quran, the Islamic Holy Book...

-speaking areas of Morocco

Morocco

Morocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

. For official communications, the government and other public bodies use Modern Standard Arabic, as is the case in most Arabic-speaking countries. A mixture of French

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

and Moroccan Arabic is used in business. It is within the Maghrebi Arabic dialect continuum

Dialect continuum

A dialect continuum, or dialect area, was defined by Leonard Bloomfield as a range of dialects spoken across some geographical area that differ only slightly between neighboring areas, but as one travels in any direction, these differences accumulate such that speakers from opposite ends of the...

.

Overview

Dialect

The term dialect is used in two distinct ways, even by linguists. One usage refers to a variety of a language that is a characteristic of a particular group of the language's speakers. The term is applied most often to regional speech patterns, but a dialect may also be defined by other factors,...

because it is not a literary language

Literary language

A literary language is a register of a language that is used in literary writing. This may also include liturgical writing. The difference between literary and non-literary forms is more marked in some languages than in others...

and because it lacks prestige compared to Standard Arabic . It differs from Standard Arabic in phonology, lexicon, and syntax, and has been influenced by Berber

Berber languages

The Berber languages are a family of languages indigenous to North Africa, spoken from Siwa Oasis in Egypt to Morocco , and south to the countries of the Sahara Desert...

(mainly in its pronunciation, and grammar), French

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

and Spanish

Spanish language

Spanish , also known as Castilian , is a Romance language in the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several languages and dialects in central-northern Iberia around the 9th century and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castile into central and southern Iberia during the...

.

Moroccan Arabic continues to evolve by integrating new French or English words, notably in technical fields, or by replacing old French and Spanish ones with Standard Arabic words within some circles.

Darija

Darija

Darija is the group of Arabic dialects spoken by Maghrebi Arabic speakers. It is only used for oral communication, with Modern Standard Arabic used for written communication...

(which means "dialect") can be divided into two groups:

- The pre-French protectorate: when Morocco was officially colonized by France in 1912, it had an accelerated French influence in aspects of everyday life. The pre-French Darija is one that is spoken by older and more conservative people. It is an Arabic dialect with Berber influences that can be found in texts and poems of Malhoun, and Andalusi music for example. Later, in the 1970s, traditionalist bands like Nass El GhiwaneNass El GhiwaneNass El Ghiwane are a musical group established in 1971 in Casablanca, Morocco. Their song "Ya Sah" appears in the film The Last Temptation of Christ and on the associated album Passion – Sources. The group, which originated in avant-garde political theater, has played an influential role in...

and Jil JilalaJil JilalaJil Jilala is a Moroccan musical group which rose to prominence in the 1970s among the movement created by Nass El Ghiwane and Lem Chaheb. Jil Jilala was founded in Marrakech in 1972 by performing arts students Mohamed Derhem, Moulay Tahar Asbahani, Sakina Safadi, Mahmoud Essaadi, Hamid Zoughi and...

followed this course, and only sang in "classical darija".

- The post-French protectorate: after the coming of the French, any French word, whether a verb or a noun, could be thrown into a sentence. This was more a habit of the young educated generations of the cities.

A similar phenomenon can be observed in Algerian Arabic

Algerian Arabic

Algerian Arabic is the variety or varieties of Arabic spoken in Algeria. In Algeria, as elsewhere, spoken Arabic differs from written Arabic; Algerian Arabic has a vocabulary mostly Arabic, with significant Berber substrates, and many new words and loanwords borrowed from French, Turkish and...

and Tunisian Arabic

Tunisian Arabic

Tunisian Arabic is a Maghrebi dialect of the Arabic language, spoken by some 11 million people. It is usually known by its own speakers as Derja, which means dialect, to distinguish it from Standard Arabic, or as Tunsi, which means Tunisian...

.

Relationship with other languages

Moroccan Arabic has a distinct pronunciation and is nearly unintelligible to other Arabic speakers, but is generally mutually intelligible with other Maghrebi Arabic dialects with which it forms a dialect continuumDialect continuum

A dialect continuum, or dialect area, was defined by Leonard Bloomfield as a range of dialects spoken across some geographical area that differ only slightly between neighboring areas, but as one travels in any direction, these differences accumulate such that speakers from opposite ends of the...

. It is grammatically simpler, and has a less voluminous vocabulary than Classical Arabic. It has also integrated many Berber

Berber languages

The Berber languages are a family of languages indigenous to North Africa, spoken from Siwa Oasis in Egypt to Morocco , and south to the countries of the Sahara Desert...

, French

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

and Spanish

Spanish language

Spanish , also known as Castilian , is a Romance language in the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several languages and dialects in central-northern Iberia around the 9th century and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castile into central and southern Iberia during the...

words.

There is a relatively clear-cut division between Moroccan Arabic and Standard Arabic, and most uneducated Moroccans do not understand Modern Standard Arabic. Depending on cultural background and degree of literacy, those who do speak Modern Standard Arabic may prefer to use Arabic words instead of their French or Spanish borrowed counterparts, while upper and educated classes often adopt code-switching

Code-switching

In linguistics, code-switching is the concurrent use of more than one language, or language variety, in conversation. Multilinguals—people who speak more than one language—sometimes use elements of multiple languages in conversing with each other...

between French and Moroccan Arabic. As elsewhere in the world, how someone speaks and what words or language they use is often an indicator of their social class

Prestige dialect

In sociolinguistics, prestige describes the level of respect accorded to a language or dialect as compared to that of other languages or dialects in a speech community. The concept of prestige in sociolinguistics is closely related to that of prestige or class within a society...

.

Pronunciation

Moroccan Arabic has a distinct pronunciation nearly unintelligible to Arabic speakers from the Middle East. With the exception of the Shamali Darija, the North Moroccan dialect spoken in and around Tanger and Tetouan (also known as Jibli) and other regional varieties in Fes and Rabat, it is heavily influenced by Berber pronunciation, and it has even been argued that it is Arabic pronounced with a BerberBerber people

Berbers are the indigenous peoples of North Africa west of the Nile Valley. They are continuously distributed from the Atlantic to the Siwa oasis, in Egypt, and from the Mediterranean to the Niger River. Historically they spoke the Berber language or varieties of it, which together form a branch...

accent, or with Berber phoneme

Phoneme

In a language or dialect, a phoneme is the smallest segmental unit of sound employed to form meaningful contrasts between utterances....

s. This is similar to the phenomenon in the south of France where some pronounce French with Occitan phonemes.

Vowels

One of the most notable features of Moroccan Arabic is the collapse of short vowels. Initially, short /ă/ and /ĭ/ were merged into a phoneme /ə/ (however, some speakers maintain a difference between /ă/ and /ə/ when adjacent to pharyngeal /ʕ/ and /ħ/). This phoneme was then deleted entirely in most positions; for the most part, it is maintained only in the position /...CəC#/ or /...CəCC#/ (where C represents any consonant and # indicates a word boundary), i.e. when appearing as the last vowel of a word. When /ə/ is not deleted, it is pronounced as a very short vowel, tending towards [ɐ] in the vicinity of emphatic consonants, [a] in the vicinity of pharyngeal /ʕ/ and /ħ/ (for speakers who have merged /ă/ and /ə/ in this environment), and [ɪ] elsewhere. Original short /ŭ/ usually merges with /ə/ except in the vicinity of a labial or velar consonant. In positions where /ə/ was deleted, /ŭ/ was also deleted, and is maintained only as labialization of the adjacent labial or velar consonant; where /ə/ is maintained, /ŭ/ surfaces as [ʊ]. This deletion of short vowels can result in long strings of consonants (a feature shared with Berber and certainly derived from it). These clusters are never simplified; instead, consonants occurring between other consonants tend to syllabify, according to a sonorance hierarchy. Similarly, and unlike most other Arabic dialects, doubled consonants are never simplified to a single consonant, even when at the end of a word or preceding another consonant.Some dialects are more conservative in their treatment of short vowels. For example, some dialects allow /ŭ/ in more positions. Dialects of the Sahara, and eastern dialects near the border of Algeria, preserve a distinction between /ă/ and /ĭ/ and allow /ă/ to appear at the beginning of a word, e.g. /ăqsˤărˤ/ "shorter" (standard /qsˤərˤ/), /ătˤlăʕ/ "go up!" (standard /tˤlăʕ/ or /tˤləʕ/), /ăsˤħab/ "friends" (standard /sˤħab/).

Long /a/, /i/ and /u/ are maintained as semi-long vowels, which are substituted for both short and long vowels in most borrowings from Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). Long /a/, /i/ and /u/ also have many more allophones than in most other dialects; in particular, /a/, /i/, /u/ appear as [ɑ], [e], [o] in the vicinity of emphatic consonants, but [æ], [i], [u] elsewhere. (Most other Arabic dialects only have a similar variation for the phoneme /a/.) In some dialects, such as that of Marrakech

Marrakech

Marrakech or Marrakesh , known as the "Ochre city", is the most important former imperial city in Morocco's history...

, front-rounded and other allophones also exist.

Emphatic spreading (i.e. the extent to which emphatic consonants affect nearby vowels) occurs much less than in many other dialects. Emphasis spreads fairly rigorously towards the beginning of a word and into prefixes, but much less so towards the end of a word. Emphasis spreads consistently from a consonant to a directly following vowel, and less strongly when separated by an intervening consonant, but generally does not spread rightwards past a full vowel. For example, /bidˤ-at/ [bedɑt͡s] "eggs" (/i/ and /a/ both affected), /tˤʃaʃ-at/ [tʃɑʃæt͡s] "sparks" (rightmost /a/ not affected), /dˤrˤʒ-at/ [drˤʒæt͡s] "stairs" (/a/ usually not affected), /dˤrb-at-u/ [drˤbat͡su] "she hit him" (with [a] variable but tending to be in between [ɑ] and [æ]; no effect on /u/), /tˤalib/ [tɑlib] "student" (/a/ affected but not /i/). Contrast, for example, Egyptian Arabic

Egyptian Arabic

Egyptian Arabic is the language spoken by contemporary Egyptians.It is more commonly known locally as the Egyptian colloquial language or Egyptian dialect ....

, where emphasis tends to spread forward and backward to both ends of a word, even through several syllables.

Emphasis is audible mostly through its effects on neighboring vowels or syllabic consonants, and through the differing pronunciation of /t/ [t͡s] and /tˤ/ [t]. Actual pharyngealization of "emphatic" consonants is weak and may be absent entirely. In contrast with some dialects, vowels adjacent to emphatic consonants are pure; there is no diphthong-like transition between emphatic consonants and adjacent front vowels.

Consonants

| Labial Labial consonant Labial consonants are consonants in which one or both lips are the active articulator. This precludes linguolabials, in which the tip of the tongue reaches for the posterior side of the upper lip and which are considered coronals... |

Dental/Alveolar | Palatal Palatal consonant Palatal consonants are consonants articulated with the body of the tongue raised against the hard palate... |

Velar Velar consonant Velars are consonants articulated with the back part of the tongue against the soft palate, the back part of the roof of the mouth, known also as the velum).... |

Uvular Uvular consonant Uvulars are consonants articulated with the back of the tongue against or near the uvula, that is, further back in the mouth than velar consonants. Uvulars may be plosives, fricatives, nasal stops, trills, or approximants, though the IPA does not provide a separate symbol for the approximant, and... |

Pharyn- geal Pharyngeal consonant A pharyngeal consonant is a type of consonant which is articulated with the root of the tongue against the pharynx.-Pharyngeal consonants in the IPA:Pharyngeal consonants in the International Phonetic Alphabet :... |

Glottal Glottal consonant Glottal consonants, also called laryngeal consonants, are consonants articulated with the glottis. Many phoneticians consider them, or at least the so-called fricative, to be transitional states of the glottis without a point of articulation as other consonants have; in fact, some do not consider... |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic labialized | plain | emphatic | |||||||

| Nasal Nasal consonant A nasal consonant is a type of consonant produced with a lowered velum in the mouth, allowing air to escape freely through the nose. Examples of nasal consonants in English are and , in words such as nose and mouth.- Definition :... |

m | (mˤʷ)2 | n | |||||||

| Stop Stop consonant In phonetics, a plosive, also known as an occlusive or an oral stop, is a stop consonant in which the vocal tract is blocked so that all airflow ceases. The occlusion may be done with the tongue , lips , and &... |

voiceless | (p)3 | t͡s, (t)1 | tˤ | k | q6 | ʔ | |||

| voiced | b | (bˤʷ)2 | d | dˤ | ɡ6,7 | |||||

| Fricative Fricative consonant Fricatives are consonants produced by forcing air through a narrow channel made by placing two articulators close together. These may be the lower lip against the upper teeth, in the case of ; the back of the tongue against the soft palate, in the case of German , the final consonant of Bach; or... |

voiceless | f | (fˤʷ)2 | s8 | sˤ | ʃ | x | ħ | h | |

| voiced | (v)3 | z8 | zˤ | ʒ7 | ɣ | ʕ | ||||

| Tap | ɾ | ɾˤ4 | ||||||||

| Approximant | l | (ɫ)5 | j | w | ||||||

- In normal circumstances, non-emphatic /t/ is pronounced with noticeable affrication, almost like /t͡s/ (still distinguished from a sequence of /t/ + /s/), and hence is easily distinguishable from emphatic /tˤ/. However, in some recent loanwords from European languages, a non-affricated, non-emphatic t appears, distinguished from emphatic /tˤ/ primarily by its lack of effect on adjacent vowels (see above; an alternative analysis is possible).

- mˤʷ, bˤʷ, fˤʷ are very distinct consonants that only occur geminated, and almost always come at the beginning of a word. They function completely differently from other emphatic consonants: They are pronounced with heavy pharyngealization, affect adjacent short/unstable vowels but not full vowels, and are pronounced with a noticeable diphthongal off-glide between one of these consonants and a following front vowel. Most of their occurrences can be analyzed as underlying sequences of /mw/, /fw/, /bw/ (which appear frequently in diminutives, for example). However, a few lexical items appear to have independent occurrences of these phonemes, e.g. /mˤmˤʷ-/ "mother" (with attached possessive, e.g. /mˤmˤʷək/ "your mother").

- (p) and (v) occur mostly in recent borrowings from European languages, and may be assimilated to /b/ or /f/ in some speakers.

- Unlike in most other Arabic dialects (but, again, similar to Berber), non-emphatic /r/ and emphatic /rˤ/ are two entirely separate phonemes, almost never contrasting in related forms of a word.

- (lˤ) is rare in native words; in nearly all cases of native words with vowels indicating the presence of a nearby emphatic consonant, there is a nearby triggering /tˤ/, /dˤ/, /sˤ/, /zˤ/ or /rˤ/. Many recent European borrowings appear to require (ɫ) or some other unusual emphatic consonant in order to account for the proper vowel allophones; but an alternative analysis is possible for these words where the vowel allophones are considered to be (marginal) phonemes on their own.

- Original /q/ splits lexically into /q/ and /ɡ/; for some words, both alternatives exist.

- Original /dʒ/ normally appears as /ʒ/, but as /ɡ/ (sometimes /d/) if /s/ or /z/ appears later in the same stem: /ɡləs/ "he sat" (MSA /dʒalas/), /ɡzzar/ "butcher" (MSA /dʒazzaːr/), /duz/ "go past" (MSA /dʒuːz/).

- Original /s/ is converted to /ʃ/ if /ʃ/ occurs elsewhere in the same stem, and /z/ is similarly converted to /ʒ/ as a result of a following /ʒ/: /ʃəmʃ/ "sun" vs. MSA /ʃams/, /ʒuʒ/ "two" vs. MSA /zawdʒ/ "pair", /ʒaʒ/ "glass" vs. MSA /zudʒaːdʒ/, etc. This does not apply to recent borrowings from MSA (e.g. /mzaʒ/ "disposition"), nor as a result of the negative suffix /ʃ/ or /ʃi/.

Writing

Moroccan Arabic is rarely written (most books and magazines are in FrenchFrench language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

or Modern Standard Arabic), and there is no universally standard written system. There is also a loosely standardized Latin system used for writing Moroccan Arabic in electronic media, such as texting and chat, often based on sound-letter correspondences from French ('ch' for English 'sh', 'ou' for English 'u', etc.). It is extremely rare to find Moroccan Arabic written in the Arabic script, which is reserved for Standard Arabic. However, most systems used for writing Moroccan Arabic in linguistic works largely agree among each other, and such a system is used here.

Long (aka "stable") vowels /a/, /i/, /u/ are written a, i, u. e represents /ə/ and o represents /ŭ/ (see section on phonology, above). ă is used for /ă/ in speakers who still have this phoneme in the vicinity of pharyngeal /ʕ/ and /ħ/. ă, ĭ, and o are also used for ultra-short vowels used by educated speakers for the short vowels of some recent borrowings from MSA.

Note that in practice, /ə/ is usually deleted when not the last vowel of a word, and hence some authors prefer a transcription without this vowel, e.g. ka-t-ktb-u "You're (pl) writing" instead of ka-t-ketb-u. Others (like Richard Harrell in his reference grammar of Moroccan Arabic) maintain the e; but it never occur in an open syllable (followed by a single consonant and a vowel). Instead the e is transposed with the preceding (sometimes geminated) consonant, which ends up following the e; this is known as inversion.

y represents /j/.

ḥ and ` represent pharyngeal /ħ/ and /ʕ/.

ġ and x represent velar /ɣ/ and /x/.

ṭ, ḍ, ṣ, ẓ, ṛ, ḷ represent emphatic /tˤ, dˤ, sˤ, zˤ, rˤ, lˤ/.

š, ž represent hushing /ʃ, ʒ/.

Code switching

Many Moroccan Arabic speakers among the educated class, especially in the territory which was previously known as French MoroccoFrench Morocco

French Protectorate of Morocco was a French protectorate in Morocco, established by the Treaty of Fez. French Morocco did not include the north of the country, which was a Spanish protectorate...

, also practice code-switching

Code-switching

In linguistics, code-switching is the concurrent use of more than one language, or language variety, in conversation. Multilinguals—people who speak more than one language—sometimes use elements of multiple languages in conversing with each other...

(moving from Moroccan Arabic to French

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

and the other way around as it can be seen in the movie Marock

Marock

Marock is the 2005 Moroccan film by the female director Laïla Marrakchi. The movie was very controversial as it deals with a Muslim/Jewish love between two high school mates, Rita and Youri...

). In the northern parts of Morocco, as in Tangier

Tangier

Tangier, also Tangiers is a city in northern Morocco with a population of about 700,000 . It lies on the North African coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar where the Mediterranean meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel...

, it is common for code-switching to occur between Moroccan Arabic and Spanish

Spanish language

Spanish , also known as Castilian , is a Romance language in the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several languages and dialects in central-northern Iberia around the 9th century and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castile into central and southern Iberia during the...

, as Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

had previously controlled part of the region

Spanish Morocco

The Spanish protectorate of Morocco was the area of Morocco under colonial rule by the Spanish Empire, established by the Treaty of Fez in 1912 and ending in 1956, when both France and Spain recognized Moroccan independence.-Territorial borders:...

, and also continues to possess the territories of Ceuta

Ceuta

Ceuta is an autonomous city of Spain and an exclave located on the north coast of North Africa surrounded by Morocco. Separated from the Iberian peninsula by the Strait of Gibraltar, Ceuta lies on the border of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Ceuta along with the other Spanish...

and Melilla

Melilla

Melilla is a autonomous city of Spain and an exclave on the north coast of Morocco. Melilla, along with the Spanish exclave Ceuta, is one of the two Spanish territories located in mainland Africa...

in North Africa bordering only Morocco. On the other hand, some educated Moroccans, particularly those sympathetic to the ideas of Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism

Arab nationalism is a nationalist ideology celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language and literature of the Arabs, calling for rejuvenation and political union in the Arab world...

, generally attempt to avoid French and Spanish influences (save those Spanish influences from al-Andalus

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

) on their speech, even when speaking in darija; consequently, their speech tends to resemble old Andalusi Arabic

Andalusi Arabic

Andalusian Arabic was a variety of the Arabic language spoken in Al-Andalus, the regions of the Iberian Peninsula under Muslim rule...

and pre-occupation Maghrebi.

Vocabulary

Moroccan Arabic is grammatically simpler and has a less voluminous vocabulary than Classical Arabic. It has also integrated many BerberBerber languages

The Berber languages are a family of languages indigenous to North Africa, spoken from Siwa Oasis in Egypt to Morocco , and south to the countries of the Sahara Desert...

, French

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

and Spanish

Spanish language

Spanish , also known as Castilian , is a Romance language in the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several languages and dialects in central-northern Iberia around the 9th century and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castile into central and southern Iberia during the...

words. Spanish words typically entered Moroccan Arabic earlier than French ones. Some words might have been brought by Moriscos who spoke Andalusi Arabic

Andalusi Arabic

Andalusian Arabic was a variety of the Arabic language spoken in Al-Andalus, the regions of the Iberian Peninsula under Muslim rule...

which was influenced by Spanish (Castilian), an example being the typical Andalusian

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

dish Pastilla

Pastilla

It is a pie which combines sweet and salty flavours; a combination of crisp layers of the crêpe-like warka dough , savory meat slow-cooked in broth and spices and shredded, and a crunchy layer of toasted and ground almonds, cinnamon, and sugar.The filling is made a day ahead, and is made by...

. Other influences have been the result of the Spanish protectorate

Protectorate

In history, the term protectorate has two different meanings. In its earliest inception, which has been adopted by modern international law, it is an autonomous territory that is protected diplomatically or militarily against third parties by a stronger state or entity...

in Spanish Morocco

Spanish Morocco

The Spanish protectorate of Morocco was the area of Morocco under colonial rule by the Spanish Empire, established by the Treaty of Fez in 1912 and ending in 1956, when both France and Spain recognized Moroccan independence.-Territorial borders:...

. French words came with the French protectorate

Protectorate

In history, the term protectorate has two different meanings. In its earliest inception, which has been adopted by modern international law, it is an autonomous territory that is protected diplomatically or militarily against third parties by a stronger state or entity...

(1912–1956). Recently, young Moroccans have started to use English words in their dialects.

There are noticeable lexical differences between Moroccan Arabic and most other dialects. Some words are essentially unique to Moroccan Arabic: e.g. daba "now". Many others, however, are characteristic of Maghrebi Arabic as a whole, including both innovations and unusual retentions of Classical vocabulary that has disappeared elsewhere such as hbeṭ "go down" from Classical habaṭ. Others distinctives are shared with Algerian Arabic

Algerian Arabic

Algerian Arabic is the variety or varieties of Arabic spoken in Algeria. In Algeria, as elsewhere, spoken Arabic differs from written Arabic; Algerian Arabic has a vocabulary mostly Arabic, with significant Berber substrates, and many new words and loanwords borrowed from French, Turkish and...

such as hḍeṛ "talk", from Classical hadhar "babble" and temma "there" from Classical thamma.

There are a number of Moroccan Arabic dictionaries in existence, including (in chronological order):

- A Dictionary of Moroccan Arabic: Moroccan-English, ed. Richard S. Harrell & Harvey Sobelman. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1963 (reprinted 2004.) معجم الفصحى في العامية المغربية, Muhammad Hulwi, Rabat: al-Madaris 1988.

- Dictionnaire Colin d'arabe dialectal marocain (Rabat, éditions Al Manahil, ministère des Affaires Culturelles), by a Frenchman named Georges Séraphin Colin, who devoted nearly all his life to it from 1921 to 1977. The dictionary contains 60 000 entries and was published in 1993, after Colin's death.

Some words borrowed from Berber

- Mouch or Mech : cat (orig. Amouch)

- Khizzou : carrots ([xizzu])

- Yekh : onomatopoeia expressing disgust (orig. Ikhan) ([jɛx])

- Dchar or Tchar : zone ([tʃɑr])

- Neggafa : wedding facilitator (orig. taneggaft) ([nɪɡɡafa])

- sifet or sayfet : send ([sˤaɪfɪtˤ])

- Sebniya: veil in north only

- jaada : carrots in north only

- sarred : synonyme of send in the north only

Some words borrowed from French

- forchita : fourchette (fork)

- tomobile or tonobile : automobile (car) ([tˤomobil])

- telfaza : télévision (television) ([tɪlfɑzɑ])

- radio : radio ([rɑdˤjo])—NB: rādio is common across most varieties of Arabic.

- bartma : appartement (apartment) ([bɑrtˤmɑ])

- rambwa : rondpoint (traffic circle) ([rambwa])

- tobis : autobus (bus) ([tˤobis])

- camera: caméra (camera) ([kɑmerɑ])

- portable: portable (cell phone) ([portˤɑbl])

- tilifūn: téléphone (telephone) ([tilifuːn])

- brika: briquet (lighter) ([bri-key])

- parisiana: a French baguette, more common is komera, stick

- disk : song

- Danon: Yogurt, genericizedGenericized trademarkA genericized trademark is a trademark or brand name that has become the colloquial or generic description for, or synonymous with, a general class of product or service, rather than as an indicator of source or affiliation as intended by the trademark's holder...

from Danone, a brand of yoghurt (in some regions)

Some words borrowed from Spanish

Some of these words might also have come through Andalusi ArabicAndalusi Arabic

Andalusian Arabic was a variety of the Arabic language spoken in Al-Andalus, the regions of the Iberian Peninsula under Muslim rule...

brought by Moriscos when they were expelled from Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

following the Christian Reconquest

Reconquista

The Reconquista was a period of almost 800 years in the Middle Ages during which several Christian kingdoms succeeded in retaking the Muslim-controlled areas of the Iberian Peninsula broadly known as Al-Andalus...

.

- roueda : rueda (wheel)

- cuzina : cocina (kitchen) ([kuzinɑ])

- simana : semana (week) ([simɑnɑ])

- manta : manta (blanket) ([mɑltˤɑ])

- rial : real (five centimes; this term has also been borrowed into many other Arabic dialects) ([rjɑl])

- fundo : fondo (bottom of the sea or the swimming pool) ([fundˤo])

- carrossa : carrosa (carrosse) ([kɑrrosɑ])

- courda : cuerda (rope) ([kordˤɑ])

- cama (in the north only) : cama (bed) ([kamˤɑ])

- blassa : plaza (place) ([blasɑ])

- l banio: el baño (toilet)

- comer : eat (but Moroccans use this expression to name the parisian bread)

- Disco : song (in north only)

Some words borrowed from Portuguese and German

These words are used in several coastal cities across the Moroccan coast like OualidiaOualidia

Oualidia is a little coastal village in Morocco situated between El Jadida and Safi. It owns the largest bird habitat....

, El Jadida

El Jadida

El Jadida is a port city on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, in the province of El Jadida. It has a population of 144,440...

, and Tangier

Tangier

Tangier, also Tangiers is a city in northern Morocco with a population of about 700,000 . It lies on the North African coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar where the Mediterranean meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel...

)

Some examples of regional differences

- Now: "Daba" in the majority of regions but "druk" or "druka" is also used in some regions in the center and south, and "drwek" or "durk" in the East

- When?: "fuqash" in most regions,"fewakht" in the Northwest (Tangier-Tetouan) but "imta" in the Atlantic region, and "waqtash" in Rabat region

- What?: "Ashnu", "shnu" or "ash" in most regions, but "shenni", "shennu" in the North, "shnu", "sh" in Fes, and "washta", "wasmu", "wash" in the Far East

Some useful sentences

Note: All the sentences are written according to the transliteration of the Arabic alphabetArabic alphabet

The Arabic alphabet or Arabic abjad is the Arabic script as it is codified for writing the Arabic language. It is written from right to left, in a cursive style, and includes 28 letters. Because letters usually stand for consonants, it is classified as an abjad.-Consonants:The Arabic alphabet has...

.

| English | Western Arabic | Northern (Jebli, Tetouani) Arabic | Eastern (Oujda) Arabic |

|---|---|---|---|

| How are you? | La bas / Ça va? | La bas? / Bikhayr?/ Keef nta? / Amandrah? | La bas? / Rak ġaya / Rak Shbab? |

| Can you help me? | Yemken lek tʿaweni? | Tekdar dʿaweni? | Yemken lek tʿaweni? |

| Do you speak English? | Waš katehdar lingliziya / wash katidwi bil lingliziya? | Waš kadehdar be llingliza? / kat tehdar lengliziya? | Waš tehdar lingliziya? |

| Excuse me | Smaḥ liya | Smaḥ li | Smaḥ liya |

| Good luck | ḥaḍ saʿid | ḥaḍ saʿid | ḥaḍ saʿid |

| Good morning | ṣbaḥ el-khir | ṣbaḥ el-khir / Sbah el noor | ṣbaḥ el-khir |

| Good night | Teṣbaḥ ʿla khir | ṣbaḥ ʿla khir | Teṣbaḥ ʿla khir |

| Goodbye | Beslama | Beslama / howa hadak | Beslama |

| Happy new year | Sana saʿida | Sana saʿida | Sana saʿida |

| Hello | As-salam ʿleykum / Ahlan | As-salamou ʿaleykum/ Ahlan | As-salam ʿlikum |

| How are you doing? | La bas ʿlik? | La bas? | La bas ʿlik? |

| How are you? | Ki dayer ? (masculine) / Ki dayra ? (feminine) | Kif ntin? / Keef ntinah? | Ki rak? |

| Is everything okay? | Kulši mezyan ? | Kulši mezyan ? / Kulšî huwa hadak ? | Kulši mliḥ? / Kulšî zin? |

| Nice to meet you | Metšarfin | Metšarfin | Metšarfin |

| No thanks | La šukran | La šukran | La šukran |

| Please | Allāh ikhallik / ʿafak | Laykhallik / Layʿizek / Khaylah | Allāh ikhallik / yʿizek |

| Take care | Thalla f raṣek | Thallah / Thalla | Thalla f raṣek |

| Thank you very much | Šukran bezaf | Šukran bezaf | Šukran bezaf |

| What do you do? | Faš khaddam? | Škad ʿaddel? / šenni khaddam? (masculine) / šenni khaddama? (feminine) / škadekhdem? / cheeni kat e'mel/'adal f hyatak? | Faš tekhdem? (masculine) / Faš tkhedmi ? (feminine) |

| What's your name? | Ašnu smiytek? / šu smiytek | Šenni ismek? / keefach msemy nta/ntinah? | Wašta smiytek? |

| Where are you from? | Mnin nta? (masculine) / Mnin nti? (feminine) | Mnayen ntina? / Mayen ntina? | Min ntaya? / Min ntiya? |

| Where are you going? | Fin ġadi temši? | Nayemmaši? (masculine) / Nayemmaša? (feminine) | Ferak temši? / Ferak rayaḥ |

| You are welcome | La šukr ʿlâ wajib / Bla jmil | La šukr ʿlâ wajib/mashi mushkil | La šukr ʿlâ wajib |

Introduction

The regular Moroccan verb conjugates with a series of prefixes and suffixes. The stem of the conjugated verb may change a bit depending on the conjugation. Example:The stem of the Moroccan verb for "to write" is kteb.

The past tense

The past tense of kteb "write" is as follows:

I wrote: kteb-t

You wrote: kteb-ti

He/it wrote: kteb (kteb can also be an order to write, e.g.: kteb er-rissala: Write the letter)

She/it wrote: ketb-et

We wrote: kteb-na

You (pl) wrote: kteb-tu

They wrote: ketb-u

Note that the stem kteb turns into ketb before a vowel suffix, due to the process of inversion described above.

The present tense

The present tense of kteb "write" is as follows:

I'm writing: ka-ne-kteb

You're (masculine) writing: ka-te-kteb

You're (feminine) writing: ka-t-ketb-i

He's/it's writing: ka-ye-kteb

She's/it's writing: ka-te-kteb

We're writing: ka-n-ketb-u

You're (pl) writing: ka-t-ketb-u

They're writing: ka-y-ketb-u

Note that the stem kteb turns into ketb before a vowel suffix, due to the process of inversion described above. Between the prefix ka-n-, ka-t-, ka-y- and the stem kteb, an e vowel appears, but not between the prefix and the transformed stem ketb, due to the same restriction that produces inversion.

In the north, "youre writing" is always ka-de-kteb, regardless of whom you are speaking to.

This is also the case of de in de-kteb, as northerners prefer to use de and southerners prefer using te.

Instead of the prefix ka, some speakers prefer the use of ta (e.g. ta-ne-kteb "I'm writing"). The co-existence of these two prefixes is due to historical differences. In general ka is more used in the north and ta in the south. In some regions like the east (Oujda) the majority of speakers don't use any preverb (ne-kteb, te-kteb, y-kteb, etc.).

Other tenses

To form the future tense, just remove the prefix ka-/ta- and replace it with the prefix ġa-, ġad- or ġadi instead (e.g. ġa-ne-kteb "I will write", ġad-ketb-u (north) or ġadi t-ketb-u "You (pl) will write").

For the subjunctive and infinitive, just remove the ka- (e.g. bġit ne-kteb "I want to write", bġit te-kteb "I want you to write").

The imperative is conjugated with the suffixes of the present tense but without any prefixes or preverbs:

kteb "Write! (masc. sing.)"

ketb-i "Write! (fem. sing.)"

ketb-u "Write! (pl.)"

Negation

One characteristic of Moroccan syntax which it shares with other North African varieties as well as some southern Levantine dialect areas is in the two-part negative verbal circumfix /ma-...-ʃi/.

- Past: /kteb/ "he wrote" /ma-kteb-ʃi/ "he didn't write"

- Present: /ka-y-kteb/ "he writes" /ma-ka-y-kteb-ʃi/ "he doesn't write"

/ma-/ comes from the Classical Arabic negator /ma/. /-ʃi/ is a development of Classical /ʃayʔ/ "thing". The development of a circumfix is similar to the French circumfix ne ... pas, where ne comes from Latin non "not" and pas comes from Latin passus "step". (Originally, pas would have been used specifically with motion verbs, as in "I didn't walk a step", and then was generalized to other verbs.)

The negative circumfix surrounds the entire verbal composite including direct and indirect object pronouns:

"he didn't write them to me" "he doesn't write them to me" "he won't write them to me" "didn't he write them to me?" "doesn't he write them to me?" "won't he write them to me?"

Note that future-tense and interrogative sentences use the same /ma-...-ʃi/ circumfix (unlike, for example, in Egyptian Arabic).

Also, unlike in Egyptian Arabic, there are no phonological changes to the verbal cluster as a result of adding the circumfix. In Egyptian Arabic, adding the circumfix can trigger stress shifting, vowel lengthening and shortening, elision when /ma-/ comes into contact with a vowel, addition or deletion of a short vowel, etc. However, none of these occur in Moroccan Arabic (MA):

- There is no phonological stress in MA.

- There is no distinction between long and short vowels in MA.

- There are no restrictions on complex consonant clusters in MA, and hence no need to insert vowels to break up such clusters.

- There are no verbal clusters that begin with a vowel: The short vowels in the beginning of Forms IIa(V) and such have already been deleted, and MA has first-person singular non-past /ne-/ in place of Egyptian /a-/.

Negative pronouns such as walu "nothing", ḥta ḥaja "nothing" and ḥta waḥed "nobody" could be added to the sentence without ši as a suffix.

Examples:

- ma-ġa-ne-kteb walu "I will not write anything"

- ma-te-kteb ḥta ḥaja "Do not write anything"

- ḥta waḥed ma-ġa-ye-kteb "Nobody will write"

- wellah ma-ne-kteb or wellah ma-ġa-ne-kteb "I swear to God I will not write"

Note: wellah ma-ne-kteb could be a response to a command to write kteb, while wellah ma-ġa-ne-kteb could be an answer to a question like waš ġa-te-kteb? "Are you going to write?" .

In the north, "youre writing" is always ka-de-kteb, regardless of whom you are speaking to.

This is also the case of de in de-kteb, as northerners prefer to use de and southerners prefer using te.

Instead of the prefix ka, some speakers prefer the use of ta (e.g. ta-ne-kteb "I'm writing"). The co-existence of these two prefixes is due to historical differences. In general ka is more used in the north and ta in the south. In some regions like the east (Oujda) the majority of speakers don't use any preverb (ne-kteb, te-kteb, y-kteb, etc.).

Negative interrogation

In Moroccan Arabic, the word order doesn't change for negative questions in the northern parts of Morocco, but in the western areas and other regions, the word order is preferably changed. The pronoun waš could be added in the beginning of the sentence, although it rarely changes the meaning of it. The prefix ma can rarely be removed when asking a question in a fast way.

Examples:

A ka can be added in the beginning of the sentence when asking a question in an angry or surprised way. In this case, waš can't be added.

Examples:

In Detail

Verbs in Arabic are based on a consonantal root composed of three or four consonants. The set of consonants communicates the basic meaning of a verb. Changes to the vowels in between the consonants, along with prefixes and/or suffixes, specify grammatical functions such as tense, person and number, in addition to changes in the meaning of the verb that embody grammatical concepts such as causativeCausative

In linguistics, a causative is a form that indicates that a subject causes someone or something else to do or be something, or causes a change in state of a non-volitional event....

, intensive

Intensive

In grammar, an intensive word form is one which denotes stronger or more forceful action relative to the root on which the intensive is built. Intensives are usually lexical formations, but there may be a regular process for forming intensives from a root...

, passive

Passive voice

Passive voice is a grammatical voice common in many of the world's languages. Passive is used in a clause whose subject expresses the theme or patient of the main verb. That is, the subject undergoes an action or has its state changed. A sentence whose theme is marked as grammatical subject is...

or reflexive

Reflexive

Reflexive may refer to:In fiction:*MetafictionIn grammar:*Reflexive pronoun, a pronoun with a reflexive relationship with its self-identical antecedent*Reflexive verb, where a semantic agent and patient are the same...

.

Each particular lexical verb is specified by two stems, one used for the past tense and one used for non-past tenses along with subjunctive

Subjunctive mood

In grammar, the subjunctive mood is a verb mood typically used in subordinate clauses to express various states of irreality such as wish, emotion, possibility, judgment, opinion, necessity, or action that has not yet occurred....

and imperative

Imperative mood

The imperative mood expresses commands or requests as a grammatical mood. These commands or requests urge the audience to act a certain way. It also may signal a prohibition, permission, or any other kind of exhortation.- Morphology :...

moods. To the former stem, suffixes are added to mark the verb for person, number and gender, while to the latter stem, a combination of prefixes and suffixes are added. (Very approximately, the prefixes specify the person and the suffixes indicate number and gender.) The third person masculine singular past tense form serves as the "dictionary form" used to identify a verb, similar to the infinitive

Infinitive

In grammar, infinitive is the name for certain verb forms that exist in many languages. In the usual description of English, the infinitive of a verb is its basic form with or without the particle to: therefore, do and to do, be and to be, and so on are infinitives...

in English. (Arabic has no infinitive.) For example, the verb meaning "write" is often specified as kteb, which actually means "he wrote". In the paradigms below, a verb will be specified as kteb/ykteb (where kteb means "he wrote" and ykteb means "he writes"), indicating the past stem (kteb-) and non-past stem (also -kteb-, obtained by removing the prefix y-).

The verb classes in Arabic are formed along two axes. The first or derivational axis (described as "form I", "form II", etc.) is used to specify grammatical concepts such as causative

Causative

In linguistics, a causative is a form that indicates that a subject causes someone or something else to do or be something, or causes a change in state of a non-volitional event....

, intensive

Intensive

In grammar, an intensive word form is one which denotes stronger or more forceful action relative to the root on which the intensive is built. Intensives are usually lexical formations, but there may be a regular process for forming intensives from a root...

, passive

Passive voice

Passive voice is a grammatical voice common in many of the world's languages. Passive is used in a clause whose subject expresses the theme or patient of the main verb. That is, the subject undergoes an action or has its state changed. A sentence whose theme is marked as grammatical subject is...

or reflexive

Reflexive

Reflexive may refer to:In fiction:*MetafictionIn grammar:*Reflexive pronoun, a pronoun with a reflexive relationship with its self-identical antecedent*Reflexive verb, where a semantic agent and patient are the same...

, and mostly involves varying the consonants of a stem form. For example, from the root K-T-B "write" is derived form I kteb/ykteb "write", form II ketteb/yketteb "cause to write", form III kateb/ykateb "correspond with (someone)", etc. The second or weakness axis (described as "strong", "weak", "hollow", "doubled" or "assimilated") is determined by the specific consonants making up the root—especially, whether a particular consonant is a W or Y—and mostly involves varying the nature and location of the vowels of a stem form. For example, so-called weak verbs have a W or Y as the last root consonant, which is reflected in the stem as a final vowel instead of a final consonant (e.g. rˤma/yrˤmi "throw" from R-M-Y). Meanwhile, hollow verbs are usually caused by a W or Y as the middle root consonant, and the stems of such verbs have a full vowel (/a/, /i/ or /u/) before the final consonant, oftentimes along with only two consonants (e.g. ʒab/yʒib "bring" from ʒ-Y-B).

When speaking of the weakness axis, it is important to distinguish between strong, weak, etc. stems and strong, weak, etc. roots. For example, X-W-F is a hollow root, but the corresponding form II stem xuwwef/yxuwwef "frighten" is a strong stem. In particular:

- Weak roots are those that have W or Y as the last consonant. Weak stems are those that have a vowel as the last segment of the stem. For the most part, there is a one-to-one correspondence between weak roots and weak stems. However, form IX verbs with a weak root will show up the same way as other root types (that is, with doubled stems in most dialects, but with hollow stems in Moroccan Arabic).

- Hollow roots are triliteral roots that have W or Y as the last consonant. Hollow stems are those that end with /-VC/, where V is a long vowel (most dialects) or full vowel in Moroccan (i.e. /a/, /i/ or /u/). Only triliteral hollow roots form hollow stems, and only in forms I, IV, VII, VIII and X. In other cases, a strong stem generally results. In Moroccan Arabic, all form IX verbs yield hollow stems regardless of root shape, e.g. sman "be fat" from S-M-N.

- Doubled roots are roots that have the final two consonants identical. Doubled stems end with a geminate consonant. Only Forms I, IV, VII, VIII, and X yield a doubled stem from a doubled root—other Forms yield a strong stem. In addition, in most dialects (but not Moroccan) all stems in Form IX are doubled, e.g. Egyptian Arabic iħmárˤrˤ/yiħmárˤrˤ "be red, blush" from Ħ-M-R.

- Assimilated roots are those where the first consonant is a W or Y. Assimilated stems begin with a vowel. Only Form I (and Form IV?) yields assimilated stems, and only in the non-past. In Moroccan Arabic, assimilated stems don't really exist at all.

- Strong roots and stems are those that don't fall under any of the other categories described above. It is common for a strong stem to correspond with a non-strong root, but not usually the other way around.

Table of Verb Forms

In this section all verb classes and their corresponding stems are listed, excluding the small number of irregular verbs described above. Verb roots are indicated schematically using capital letters to stand for consonants in the root:

- F = first consonant of root

- M = middle consonant of three-consonant root

- S = second consonant of four-consonant root

- T = third consonant of four-consonant root

- L = last consonant of root

Hence, the root F-M-L stands for all three-consonant roots, and F-S-T-L stands for all four-consonant roots. (Traditional Arabic grammar uses F-ʕ-L and F-ʕ-L-L, respectively, but the system used here appears in a number of grammars of spoken Arabic dialects and is probably less confusing for English speakers, since the forms are easier to pronounce than those involving /ʕ/.)

The following table lists the prefixes and suffixes to be added to mark tense, person, number and gender, and the stem form to which they are added. The forms involving a vowel-initial suffix, and corresponding stem PAv or NPv, are highlighted in silver. The forms involving a consonant-initial suffix, and corresponding stem PAc, are highlighted in gold. The forms involving no suffix, and corresponding stem PA0 or NP0, are unhighlighted.

| Tense/Mood | Past | Non-Past | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person | Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| 1st | PAc-t | PAc-na | n(e)-NP0 | n(e)-NP0-u/w | |

| 2nd | masculine | PAc-ti | PAc-tiw | t(e)-NP0 | t(e)-NPv-u/w |

| feminine | t(e)-NPv-i/y | ||||

| 3rd | masculine | PA0 | PAv-u/w | y-NP0 | y-NPv-u/w |

| feminine | PAv-et | t(e)-NP0 | |||

The following table lists the verb classes along with the form of the past and non-past stems, active and passive participles, and verbal noun, in addition to an example verb for each class.

Notes:

- Italicized forms are those that follow automatically from the regular rules of deletion of /e/.

- In the past tense, there can be up to three stems:

- When only one form appears, this same form is used for all three stems.

- When three forms appear, these represent first-singular, third-singular and third-plural, which indicate the PAc, PA0 and PAv stems, respectively.

- When two forms appear, separated by a comma, these represent first-singular and third-singular, which indicate the PAc and PA0 stems. When two forms appear, separated by a semicolon, these represent third-singular and third-plural, which indicate the PA0 and PAv stems. In both cases, the missing stem is the same as the third-singular (PA0) stem.

- Not all forms have a separate verb class for hollow or doubled roots. In such cases, the table below has the notation "(use strong form)", and roots of that shape appear as strong verbs in the corresponding form; e.g. Form II strong verb dˤáyyaʕ/yidˤáyyaʕ "waste, lose" related to Form I hollow verb dˤaʕ/yidˤiʕ "be lost", both from root Dˤ-Y-ʕ.

| Form | Strong | Weak | Hollow | Doubled | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past | Non-Past | Example | Past | Non-Past | Example | Past | Non-Past | Example | Past | Non-Past | Example | |

| I | FMeL; FeMLu | yFMeL, yFeMLu | kteb/ykteb "write", ʃrˤeb/yʃrˤeb "drink" | FMit, FMa | yFMi | rˤma/yrˤmi "throw", ʃra/yʃri "buy" | FeLt, FaL | yFiL | baʕ/ybiʕ "sell", ʒab/yʒib "bring" | FeMMit, FeMM | yFeMM | ʃedd/yʃedd "close", medd/ymedd "hand over" |

| yFMoL, yFeMLu | dxel/ydxol "enter", sken/yskon "reside" | yFMa | nsa/ynsa "forget" | yFuL | ʃaf/yʃuf "see", daz/yduz "pass" | FoMMit, FoMM | yFoMM | koħħ/ykoħħ "cough" | ||||

| yFMu | ħba/yħbu "crawl" | yFaL | xaf/yxaf "sleep", ban/yban "seem" | |||||||||

| FoLt, FaL | yFuL | qal/yqul "say", kan/ykun "be" (the only examples) | ||||||||||

| II | FeMMeL; FeMMLu | yFeMMeL, yFeMMLu | beddel/ybeddel "change" | FeMMit, FeMMa | yFeMMi | werra/ywerri "show" | (same as strong) | |||||

| FuwweL; FuwwLu | yFuwweL, yFuwwLu | xuwwef/yxuwwef "frighten" | Fuwwit, Fuwwa | yFuwwi | luwwa/yluwwi "twist" | |||||||

| FiyyeL; FiyyLu | yFiyyeL, yFiyyLu | biyyen/ybiyyen "indicate" | Fiyyit, Fiyya | yFiyyi | qiyya/yqiyyi "make vomit" | |||||||

| III | FaMeL; FaMLu | yFaMeL, yFaMLu | sˤaferˤ/ysˤaferˤ "travel" | FaMit, FaMa | yFaMi | qadˤa/yqadˤi "finish (trans.)", sawa/ysawi "make level" | (same as strong) | FaMeMt/FaMMit, FaM(e)M, FaMMu | yFaM(e)M, yFaMMu | sˤaf(e)f/ysˤaf(e)f "line up (trans.)" | ||

| Ia(VIIt) | tteFMeL; ttFeMLu | ytteFMeL, yttFeMLu | ttekteb/yttekteb "be written" | tteFMit, tteFMa | ytteFMa | tterˤma/ytterˤma "be thrown", ttensa/yttensa "be forgotten" | ttFaLit/ttFeLt/ttFaLt, ttFaL | yttFaL | ttbaʕ/yttbaʕ "be sold" | ttFeMMit, ttFeMM | yttFeMM | ttʃedd/yttʃedd "be closed" |

| ytteFMoL, yttFeMLu | ddxel/yddxol "be entered" | yttFoMM | ttfekk/yttfokk "get loose" | |||||||||

| IIa(V) | tFeMMeL; tFeMMLu | ytFeMMeL, ytFeMMLu | tbeddel/ytbeddel "change (intrans.)" | tFeMMit, tFeMMa | ytFeMMa | twerra/ytwerra "be shown" | (same as strong) | |||||