Nuclear thermal rocket

Encyclopedia

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with atomic number 1. It is represented by the symbol H. With an average atomic weight of , hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant chemical element, constituting roughly 75% of the Universe's chemical elemental mass. Stars in the main sequence are mainly...

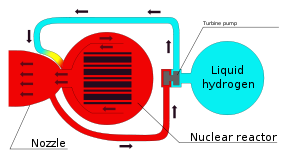

, is heated to a high temperature in a nuclear reactor

Nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device to initiate and control a sustained nuclear chain reaction. Most commonly they are used for generating electricity and for the propulsion of ships. Usually heat from nuclear fission is passed to a working fluid , which runs through turbines that power either ship's...

, and then expands through a rocket nozzle to create thrust

Thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's second and third laws. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction on that system....

. In this kind of thermal rocket

Thermal rocket

A thermal rocket is a rocket engine that uses a propellant that is externally heated before being passed through a nozzle, as opposed to undergoing a chemical reaction as in a chemical rocket.Thermal rockets can give high performance....

, the nuclear reactor's energy replaces the chemical energy of the propellant

Propellant

A propellant is a material that produces pressurized gas that:* can be directed through a nozzle, thereby producing thrust ;...

's reactive chemicals in a chemical rocket. Due to the higher energy density

Energy density

Energy density is a term used for the amount of energy stored in a given system or region of space per unit volume. Often only the useful or extractable energy is quantified, which is to say that chemically inaccessible energy such as rest mass energy is ignored...

of the nuclear fuel compared to chemical fuels, about 107 times, the resulting propellant efficiency (effective exhaust velocity) of the engine is at least twice as good as chemical engines. The overall gross lift-off mass of a nuclear rocket is about half that of a chemical rocket, and hence when used as an upper stage it roughly doubles or triples the payload carried to orbit.

A nuclear engine was considered for some time as a replacement for the J-2

J-2 (rocket engine)

Rocketdyne's J-2 rocket engine was a major component of the Saturn V rocket used in the Apollo program to send men to the Moon. Five J-2 engines were used on the S-II second stage, and one J-2 was used on the S-IVB third stage. The S-IVB was also used as the second stage of the smaller Saturn IB...

used on the S-II

S-II

The S-II was the second stage of the Saturn V rocket. It was built by North American Aviation. Using liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen it had five J-2 engines in a cross pattern...

and S-IVB

S-IVB

The S-IVB was built by the Douglas Aircraft Company and served as the third stage on the Saturn V and second stage on the Saturn IB. It had one J-2 engine...

stages on the Saturn V

Saturn V

The Saturn V was an American human-rated expendable rocket used by NASA's Apollo and Skylab programs from 1967 until 1973. A multistage liquid-fueled launch vehicle, NASA launched 13 Saturn Vs from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida with no loss of crew or payload...

and Saturn I

Saturn I

The Saturn I was the United States' first heavy-lift dedicated space launcher, a rocket designed specifically to launch large payloads into low Earth orbit. Most of the rocket's power came from a clustered lower stage consisting of tanks taken from older rocket designs and strapped together to make...

rockets. Originally "drop-in" replacements were considered for higher performance, but a larger replacement for the S-IVB stage was later studied for missions to Mars and other high-load profiles, known as the S-N. Nuclear thermal space "tugs" were planned as part of the Space Transportation System

Space Transportation System

The Space Transportation System is another name for the NASA Space Shuttle and Space Shuttle program. However, the name originates from, and can describe a more elaborate set of spacefaring hardware in the 1970s, although this meaning is obscure...

to take payloads from a propellant depot in Low Earth Orbit to higher orbits, the Moon, and other planets. Robert Bussard proposed the Single-Stage-To-Orbit "Aspen" vehicle using a nuclear thermal rocket for propulsion and liquid hydrogen propellant for partial shielding against neutron back scattering in the lower atmosphere. The Soviets studied nuclear engines for their own moon rockets, notably upper stages of the N-1, although they never entered an extensive testing program like the one the U.S. conducted throughout the 1960s at the Nevada Test Site

Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site , previously the Nevada Test Site , is a United States Department of Energy reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about northwest of the city of Las Vegas...

. Despite many successful firings, American nuclear rockets did not fly before the space race

Space Race

The Space Race was a mid-to-late 20th century competition between the Soviet Union and the United States for supremacy in space exploration. Between 1957 and 1975, Cold War rivalry between the two nations focused on attaining firsts in space exploration, which were seen as necessary for national...

ended.

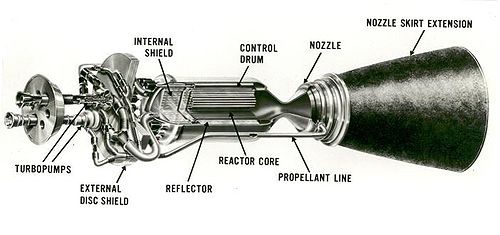

To date, no nuclear thermal rocket has flown, although the NERVA

NERVA

NERVA is an acronym for Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application, a joint program of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and NASA managed by the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office until both the program and the office ended at the end of 1972....

NRX/EST and NRX/XE were built and tested with flight design components. The highly successful U.S. Project Rover

Project Rover

Project Rover was an American project to develop a nuclear thermal rocket. The program ran at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory from 1955 through 1972 and involved the Atomic Energy Commission, and NASA. The project was managed by the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office.Nuclear reactors for the...

which ran from 1955 through 1972 accumulated over 17 hours of run time. The NERVA NRX/XE, judged by SNPO to be the last "technology development" reactor necessary before proceeding to flight prototypes, accumulated over 2 hours of run time, including 28 minutes at full power. The Russian nuclear thermal rocket RD-0410

RD-0410

RD-0410 was a Soviet nuclear thermal rocket engine developed from 1965 through the 1980s using liquid hydrogen propellant...

was also claimed by the Soviets to have gone through a series of tests at the nuclear test site near Semipalatinsk.

The United States tested twenty different sizes and designs during Project Rover

Project Rover

Project Rover was an American project to develop a nuclear thermal rocket. The program ran at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory from 1955 through 1972 and involved the Atomic Energy Commission, and NASA. The project was managed by the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office.Nuclear reactors for the...

and NASA's NERVA program from 1959 through 1972 at the Nevada Test Site, designated Kiwi, Phoebus, NRX/EST, NRX/XE, Pewee, Pewee 2 and the Nuclear Furnace, with progressively higher power densities culminating in the Pewee (1970) and Pewee 2. Tests of the improved Pewee 2 design were cancelled in 1970 in favor of the lower-cost Nuclear Furnace (NF-1), and the U.S. nuclear rocket program officially ended in spring of 1973. Research into nuclear rockets has continued quietly since that time within NASA . Current (2010) 25,000 pound-thrust reference designs (NERVA-Derivative Rockets, or NDRs) are based on the Pewee, and have specific impulses of 925 seconds .

Types of Nuclear Thermal Rockets

A nuclear thermal rocket can be categorized by the construction of its reactor, which can range from a relatively simple solid reactor up to a much more complicated but more efficient reactor with a gas core.Solid core

The most traditional type uses a conventional (albeit light-weight) nuclear reactor running at high temperatures to heat the working fluid that is moving through the reactor core. This is known as the solid-core design, and is the simplest design to construct.

Specific impulse

Specific impulse is a way to describe the efficiency of rocket and jet engines. It represents the derivative of the impulse with respect to amount of propellant used, i.e., the thrust divided by the amount of propellant used per unit time. If the "amount" of propellant is given in terms of mass ,...

s (Isp) on the order of 850 to 1000 seconds, about twice that of liquid hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen is the liquid state of the element hydrogen. Hydrogen is found naturally in the molecular H2 form.To exist as a liquid, H2 must be pressurized above and cooled below hydrogen's Critical point. However, for hydrogen to be in a full liquid state without boiling off, it needs to be...

-oxygen

Liquid oxygen

Liquid oxygen — abbreviated LOx, LOX or Lox in the aerospace, submarine and gas industries — is one of the physical forms of elemental oxygen.-Physical properties:...

designs such as the Space Shuttle Main Engine

Space Shuttle main engine

The RS-25, otherwise known as the Space Shuttle Main Engine , is a reusable liquid-fuel rocket engine built by Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne for the Space Shuttle, running on liquid hydrogen and oxygen. Each Space Shuttle was propelled by three SSMEs mated to one powerhead...

. Other propellants are sometimes proposed, such as ammonia, water or LOX

Lox

Lox is salmon fillet that has been cured. In its most popular form, it is thinly sliced—less than in thickness—and, typically, served on a bagel, often with cream cheese, onion, tomato, cucumber and capers...

. Although these propellants would provide reduced exhaust velocity, their greater availability can reduce payload costs by a very large factor where the mission delta-v

Delta-v

In astrodynamics a Δv or delta-v is a scalar which takes units of speed. It is a measure of the amount of "effort" that is needed to change from one trajectory to another by making an orbital maneuver....

is not too high, such as within cislunar space or between Earth orbit and Martian orbit. Above about 1500 K hydrogen begins to dissociate at low pressures, or 3000 K at high pressures, a potential area of promise for greatly increasing the Isp of solid core reactors.

Immediately after World War II, the weight of a complete nuclear reactor was so great that it was feared that solid-core engines would be hard-pressed to achieve a thrust-to-weight ratio

Thrust-to-weight ratio

Thrust-to-weight ratio is a ratio of thrust to weight of a rocket, jet engine, propeller engine, or a vehicle propelled by such an engine. It is a dimensionless quantity and is an indicator of the performance of the engine or vehicle....

of 1:1, which would be needed to overcome the gravity of the Earth on launch. The problem was quickly overcome, however, and over the next twenty-five years U.S. nuclear thermal rocket designs eventually reached thrust-to-weight ratios of approximately 7:1. Still, the lower thrust-to-weight ratio of nuclear thermal rockets versus chemical rockets (which have thrust-to-weight ratios of 70:1) and the large tanks necessary for liquid hydrogen storage mean that solid-core engines are best used in upper stages where vehicle velocity is already near orbital, in space "tugs" used to take payloads between gravity well

Gravity well

A gravity well or gravitational well is a conceptual model of the gravitational field surrounding a body in space. The more massive the body the deeper and more extensive the gravity well associated with it. The Sun has a far-reaching and deep gravity well. Asteroids and small moons have much...

s, or in launches from a lower gravity planet, moon or minor planet where the required thrust is lower. To be a useful Earth launch engine, the system would have to be either much lighter, or provide even higher specific impulse. The true strength of nuclear rockets currently lies in solar system exploration, outside Earth's gravity well.

One way to increase the temperature, and thus the specific impulse, is to isolate the fuel elements so they no longer have to be rigid. This is the basis of the particle-bed reactor, also known as the fluidized-bed, dust-bed, or rotating-bed design. In this design the fuel is placed in a number of (typically spherical) elements which "float" inside the hydrogen working fluid. Spinning the entire engine forces the fuel elements out to walls that are being cooled by the hydrogen. This design increases the specific impulse to about 1000 seconds (9.8 kN·s/kg), allowing for thrust-to-weight ratios just over 1:1, although at the cost of increased complexity. Such a design could share design elements with a pebble-bed reactor, several of which are currently generating electricity.

Liquid core

Dramatically greater improvements are theoretically possible by mixing the nuclear fuel into the working fluid, and allowing the reaction to take place in the liquid mixture itself. This is the basis of the so-called liquid-core engine, which can operate at higher temperatures beyond the melting point of the nuclear fuel. In this case the maximum temperature is whatever the container wall (typically a neutron reflectorNeutron reflector

A neutron reflector is any material that reflects neutrons. This refers to elastic scattering rather than to a specular reflection. The material may be graphite, beryllium, steel, and tungsten carbide, or other materials...

of some sort) can withstand, while actively cooled by the hydrogen. It is expected that the liquid-core design can deliver performance on the order of 1300 to 1500 seconds (12.8–14.8 kN·s/kg).

These engines are currently considered very difficult to build. The reaction time of the nuclear fuel is much higher than the heating time of the working fluid, requiring a method to trap the fuel inside the engine while allowing the working fluid to easily exit through the nozzle. Most liquid-phase engines have focused on rotating the fuel/fluid mixture at very high speeds, forcing the fuel to the outside due to centrifugal force (uranium is heavier than hydrogen). In many ways the design mirrors the particle-bed design, although operating at even higher temperatures.

An alternative liquid-core design, the nuclear salt-water rocket

Nuclear salt-water rocket

A nuclear salt-water rocket is a proposed type of nuclear thermal rocket designed by Robert Zubrin that would be fueled by water bearing dissolved salts of Plutonium or U235...

has been proposed by Robert Zubrin

Robert Zubrin

Robert Zubrin is an American aerospace engineer and author, best known for his advocacy of the manned exploration of Mars. He was the driving force behind Mars Direct—a proposal intended to produce significant reductions in the cost and complexity of such a mission...

. In this design, the working fluid is water, which serves as neutron moderator

Neutron moderator

In nuclear engineering, a neutron moderator is a medium that reduces the speed of fast neutrons, thereby turning them into thermal neutrons capable of sustaining a nuclear chain reaction involving uranium-235....

as well. The nuclear fuel is not retained, drastically simplifying the design. However, by its very design, the rocket would discharge massive quantities of extremely radioactive waste and could only be safely operated well outside the Earth's atmosphere and perhaps even entirely outside earth's magnetosphere

Magnetosphere

A magnetosphere is formed when a stream of charged particles, such as the solar wind, interacts with and is deflected by the intrinsic magnetic field of a planet or similar body. Earth is surrounded by a magnetosphere, as are the other planets with intrinsic magnetic fields: Mercury, Jupiter,...

.

Gas core

The final classification is the gas-core engineGas core reactor rocket

Gas core reactor rockets are a conceptual type of rocket that is propelled by the exhausted coolant of a gaseous fission reactor. The nuclear fission reactor core may be either a gas or plasma...

. This is a modification to the liquid-core design which uses rapid circulation of the fluid to create a toroidal

Toroid (geometry)

In mathematics, a toroid is a doughnut-shaped object, such as an O-ring. Its annular shape is generated by revolving a plane geometrical figure about an axis external to that figure which is parallel to the plane of the figure and does not intersect the figure...

pocket of gaseous uranium fuel in the middle of the reactor, surrounded by hydrogen. In this case the fuel does not touch the reactor wall at all, so temperatures could reach several tens of thousands of degrees, which would allow specific impulses of 3000 to 5000 seconds (30 to 50 kN·s/kg). In this basic design, the "open cycle", the losses of nuclear fuel would be difficult to control, which has led to studies of the "closed cycle" or nuclear lightbulb

Nuclear lightbulb

A nuclear lightbulb is a hypothetical type of spacecraft engine using a Fission reactor to achieve Nuclear propulsion. Specifically it would be a type of Gas core reactor rocket that separates the nuclear fuel from the coolant/propellant with a quartz wall. It would be operated at such high...

engine, where the gaseous nuclear fuel is contained in a super-high-temperature quartz

Quartz

Quartz is the second-most-abundant mineral in the Earth's continental crust, after feldspar. It is made up of a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon–oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall formula SiO2. There are many different varieties of quartz,...

container, over which the hydrogen flows. The closed cycle engine actually has much more in common with the solid-core design, but this time limited by the critical temperature of quartz instead of the fuel stack. Although less efficient than the open-cycle design, the closed-cycle design is expected to deliver a rather respectable specific impulse of about 1500–2000 seconds (15–20 kN·s/kg).

Programs

United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by Congress to foster and control the peace time development of atomic science and technology. President Harry S...

in 1955 as Project Rover

Project Rover

Project Rover was an American project to develop a nuclear thermal rocket. The program ran at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory from 1955 through 1972 and involved the Atomic Energy Commission, and NASA. The project was managed by the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office.Nuclear reactors for the...

, with work on a suitable reactor starting at Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory, managed and operated by Los Alamos National Security , located in Los Alamos, New Mexico...

and Area 25

Area 25

Area 25 is the largest named area in the Nevada Test Site at , and has its own direct access from Route 95. The majority of Area 25 is composed of a shallow alluvial basin called Jackass Flats....

in the Nevada Test Site

Nevada Test Site

The Nevada National Security Site , previously the Nevada Test Site , is a United States Department of Energy reservation located in southeastern Nye County, Nevada, about northwest of the city of Las Vegas...

. Four basic designs came from this project: KIWI, Phoebus, Pewee and the Nuclear Furnace. Twenty rockets were tested.

When NASA

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration is the agency of the United States government that is responsible for the nation's civilian space program and for aeronautics and aerospace research...

was formed in 1958, it was given authority over all non-nuclear aspects of the Rover program. In order for NASA to cooperate with the AEC

AEC

AEC is a three-letter abbreviation that may refer to:Governance* African Economic Community* ASEAN Economic Community* Asian European Council, a Paris-based non-partisan policy research organization...

, the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office

Space Nuclear Propulsion Office

The United States Space Nuclear Propulsion Office was created in 1961 in response to NASA Marshall Space Flight Center's desire to explore the use of nuclear thermal rockets created by Project Rover in NASA space exploration activities...

was created at the same time. In 1961, the NERVA

NERVA

NERVA is an acronym for Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application, a joint program of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and NASA managed by the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office until both the program and the office ended at the end of 1972....

program (Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Applications) was created. Marshall Space Flight Center

Marshall Space Flight Center

The George C. Marshall Space Flight Center is the U.S. government's civilian rocketry and spacecraft propulsion research center. The largest center of NASA, MSFC's first mission was developing the Saturn launch vehicles for the Apollo moon program...

had been increasingly using KIWI for mission planning, and NERVA was formed to formalize the entry of nuclear thermal rocket engines into space exploration. Unlike the AEC work, which was intended to study the reactor design itself, NERVA's goal was to produce a real engine that could be deployed on space missions. A 75,000 lbf (334 kN) thrust baseline NERVA design was based on the KIWI B4 series, and was considered for some time as the upper stages for the Saturn V

Saturn V

The Saturn V was an American human-rated expendable rocket used by NASA's Apollo and Skylab programs from 1967 until 1973. A multistage liquid-fueled launch vehicle, NASA launched 13 Saturn Vs from the Kennedy Space Center, Florida with no loss of crew or payload...

, in place of the J-2

J-2 (rocket engine)

Rocketdyne's J-2 rocket engine was a major component of the Saturn V rocket used in the Apollo program to send men to the Moon. Five J-2 engines were used on the S-II second stage, and one J-2 was used on the S-IVB third stage. The S-IVB was also used as the second stage of the smaller Saturn IB...

s that were actually flown.

Although the Kiwi/Phoebus/NERVA designs were the only ones to be tested in any substantial program, a number of other solid-core engines were also studied to some degree. The Small Nuclear Rocket Engine, or SNRE, was designed at the Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory, managed and operated by Los Alamos National Security , located in Los Alamos, New Mexico...

(LANL) for upper stage use, both on unmanned launchers as well as the Space Shuttle

Space Shuttle

The Space Shuttle was a manned orbital rocket and spacecraft system operated by NASA on 135 missions from 1981 to 2011. The system combined rocket launch, orbital spacecraft, and re-entry spaceplane with modular add-ons...

. It featured a split-nozzle that could be rotated to the side, allowing it to take up less room in the Shuttle cargo bay. The design provided 73 kN of thrust and operated at a specific impulse of 875 seconds (8.58 kN·s/kg), and it was planned to increase this to 975 with fairly basic upgrades. This allowed it to achieve a mass fraction

Mass fraction

In aerospace engineering, the propellant mass fraction is a measure of a vehicle's performance, determined as the portion of the vehicle's mass which does not reach the destination...

of about 0.74, comparing with 0.86 for the SSME, one of the best conventional engines.

A related design that saw some work, but never made it to the prototype stage, was Dumbo. Dumbo was similar to KIWI/NERVA in concept, but used more advanced construction techniques to lower the weight of the reactor. The Dumbo reactor consisted of several large tubes (more like barrels) which were in turn constructed of stacked plates of corrugated material. The corrugations were lined up so that the resulting stack had channels running from the inside to the outside. Some of these channels were filled with uranium fuel, others with a moderator, and some were left open as a gas channel. Hydrogen was pumped into the middle of the tube, and would be heated by the fuel as it travelled through the channels as it worked its way to the outside. The resulting system was lighter than a conventional design for any particular amount of fuel. The project developed some initial reactor designs and appeared to be feasible.

More recently an advanced engine design was studied under Project Timberwind

Project Timberwind

Project Timberwind aimed to develop nuclear thermal rockets. It was under the aegis of the Strategic Defence Initiative , later expanded into a larger design in the Space Thermal Nuclear Propulsion program...

, under the aegis of the Strategic Defense Initiative

Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative was proposed by U.S. President Ronald Reagan on March 23, 1983 to use ground and space-based systems to protect the United States from attack by strategic nuclear ballistic missiles. The initiative focused on strategic defense rather than the prior strategic...

("Star Wars"), which was later expanded into a larger design in the Space Thermal Nuclear Propulsion (STNP) program. Advances in high-temperature metals, computer modelling and nuclear engineering in general resulted in dramatically improved performance. While the NERVA engine was projected to weigh about 6,803 kg, the final STNP offered just over 1/3 the thrust from an engine of only 1,650 kg by improving the Isp to between 930 and 1000 seconds.

Test Firings

KIWI was the first to be fired, starting in July 1959 with KIWI 1. The reactor was not intended for flight, hence the naming of the rocket after a flightless birdKiwi

Kiwi are flightless birds endemic to New Zealand, in the genus Apteryx and family Apterygidae.At around the size of a domestic chicken, kiwi are by far the smallest living ratites and lay the largest egg in relation to their body size of any species of bird in the world...

. This was unlike later tests because the engine design could not really be used; the core was simply a stack of uncoated uranium oxide plates onto which the hydrogen was dumped. Nevertheless it generated 70 MW and produced an exhaust temperature of 2683 K. Two additional tests of the basic concept, A' and A3, added coatings to the plates to test fuel rod concepts.

The KIWI B series fully developed the fuel system, which consisted of the uranium

Uranium

Uranium is a silvery-white metallic chemical element in the actinide series of the periodic table, with atomic number 92. It is assigned the chemical symbol U. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons...

fuel in the form of tiny uranium dioxide

Uranium dioxide

Uranium dioxide or uranium oxide , also known as urania or uranous oxide, is an oxide of uranium, and is a black, radioactive, crystalline powder that naturally occurs in the mineral uraninite. It is used in nuclear fuel rods in nuclear reactors. A mixture of uranium and plutonium dioxides is used...

(UO2) spheres embedded in a low-boron

Boron

Boron is the chemical element with atomic number 5 and the chemical symbol B. Boron is a metalloid. Because boron is not produced by stellar nucleosynthesis, it is a low-abundance element in both the solar system and the Earth's crust. However, boron is concentrated on Earth by the...

graphite

Graphite

The mineral graphite is one of the allotropes of carbon. It was named by Abraham Gottlob Werner in 1789 from the Ancient Greek γράφω , "to draw/write", for its use in pencils, where it is commonly called lead . Unlike diamond , graphite is an electrical conductor, a semimetal...

matrix, and then coated with niobium carbide

Niobium carbide

Niobium carbide is an extremely hard refractory ceramic material, commercially used in tool bits for cutting tools. It is usually processed by sintering and is a frequent additive in cemented carbides. It has the appearance of a brown-gray metallic powder with purple lustre...

. Nineteen holes ran the length of the bundles, and through these holes the liquid hydrogen flowed for cooling. A final change introduced during the KIWI program changed the fuel to uranium carbide

Uranium carbide

Uranium carbide, a carbide of uranium, is a hard refractory ceramic material. It comes in several stoichiometries , such as uranium monocarbide , uranium sesquicarbide ,...

, which was run for the last time in 1964.

On the initial firings immense reactor heat and vibration cracked the fuel bundles. Likewise, while the graphite materials used in the reactor's construction were indeed resistant to high temperatures, they eroded under the heat and pressure of the enormous stream of superheated hydrogen. The fuel bundle problem was largely (but not completely) solved by the end of the program, and related materials work at Argonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory

Argonne National Laboratory is the first science and engineering research national laboratory in the United States, receiving this designation on July 1, 1946. It is the largest national laboratory by size and scope in the Midwest...

looked promising. Fuel and engine coatings never wholly solved this problem before the program ended.

Building on the KIWI series, the Phoebus series were much larger reactors. The first 1A test in June 1965 ran for over 10 minutes at 1090 MW, with an exhaust temperature of 2370 K. The B run in February 1967 improved this to 1500 MW for 30 minutes. The final 2A test in June 1968 ran for over 12 minutes at 4,000 MW, the most powerful nuclear reactor ever built. For contrast, the Itaipu Dam, one of the most powerful hydroelectric plants in the world, produces 14,000 MW, enough to supply 19% of all the electricity used in Brazil

Brazil

Brazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

, and 90% of that used in Paraguay

Paraguay

Paraguay , officially the Republic of Paraguay , is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to the east and northeast, and Bolivia to the northwest. Paraguay lies on both banks of the Paraguay River, which runs through the center of the...

.

NERVA NRX (Nuclear Rocket Experimental), started testing in September 1964. The final engine in this series was the XE, designed with flight design hardware and fired in a downward position into a low-pressure chamber to simulate a vacuum. SNPO fired NERVA NRX/XE twenty-eight times in March 1968. The series all generated 1100 MW, and many of the tests concluded only when the test-stand ran out of hydrogen propellant. NERVA NRX/XE produced the baseline 75,000 lbf (334 kN) thrust that Marshall required in Mars mission plans.

Zirconium carbide

Zirconium carbide is an extremely hard refractory ceramic material, commercially used in tool bits for cutting tools. It is usually processed by sintering. It has the appearance of a gray metallic powder with cubic crystal structure...

(instead of niobium carbide

Niobium carbide

Niobium carbide is an extremely hard refractory ceramic material, commercially used in tool bits for cutting tools. It is usually processed by sintering and is a frequent additive in cemented carbides. It has the appearance of a brown-gray metallic powder with purple lustre...

) but Pewee also increased the power density of the system. An unrelated water-cooled system known as NF-1 (for Nuclear Furnace) was used for future materials testing. Pewee became the basis for current NTR designs being researched at NASA's Glenn and Marshall Research Centers.

The last NRX firing lost a relatively small 38 pounds of fuel in 2 hours of testing, enough to be judged sufficient for space missions by SNPO. Pewee 2's fuel elements reduced fuel corrosion still further, by a factor of 3 in Nuclear Furnace testing, but Pewee 2 was never tested on the stand. Later designs were deemed by NASA to be usable for space exploration and Los Alamos felt that it had cured the last of the materials problems with the untested Pewee.

The NERVA/Rover

NERVA

NERVA is an acronym for Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application, a joint program of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and NASA managed by the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office until both the program and the office ended at the end of 1972....

project was eventually cancelled in 1972 with the general wind-down of NASA in the post-Apollo

Project Apollo

The Apollo program was the spaceflight effort carried out by the United States' National Aeronautics and Space Administration , that landed the first humans on Earth's Moon. Conceived during the Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower, Apollo began in earnest after President John F...

era. Without a manned mission to Mars

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun in the Solar System. The planet is named after the Roman god of war, Mars. It is often described as the "Red Planet", as the iron oxide prevalent on its surface gives it a reddish appearance...

, the need for a nuclear thermal rocket was unclear. To a lesser extent it was becoming clear that there could be intense public outcry against any attempt to use a nuclear engine.

Nuclear vs. chemical

Directly comparing the performance of a nuclear engine and a chemical one is not easy; the design of any rocket is a study in compromises and different ideas of what constitutes "better". In the outline below we will consider the NERVA-derived engine that was considered by NASA in the 1960s, comparing it with the S-IVB stage from the Saturn it was intended to replace.For any given thrust, the amount of power that needs to be generated is defined by

, where T is the thrust, and

, where T is the thrust, and  is the exhaust velocity.

is the exhaust velocity.  can be calculated from the specific impulse

can be calculated from the specific impulseSpecific impulse

Specific impulse is a way to describe the efficiency of rocket and jet engines. It represents the derivative of the impulse with respect to amount of propellant used, i.e., the thrust divided by the amount of propellant used per unit time. If the "amount" of propellant is given in terms of mass ,...

, Isp, where

(when Isp is in seconds and gn is the standard, not local, acceleration of gravity), Using the J-2 on the S-IVB as a baseline design, we have P = (1014 kN)(414 s)(9.81 m/s2)/2 = 2,060 MW. This is about the amount of power generated in a large nuclear reactor.

(when Isp is in seconds and gn is the standard, not local, acceleration of gravity), Using the J-2 on the S-IVB as a baseline design, we have P = (1014 kN)(414 s)(9.81 m/s2)/2 = 2,060 MW. This is about the amount of power generated in a large nuclear reactor.However, as outlined above, even the simple solid-core design provided a large increase in Isp to about 850 seconds. Using the formula above, we can calculate the amount of power that needs to be generated, at least given extremely efficient heat transfer: P = (1014 kN)(850 s * 9.81 m/s²)/2 = 4,227 MW. Note that it is the Isp improvement that demands the higher energy. Given inefficiencies in the heat transfer, the actual NERVA designs were planned to produce about 5 GW, which would make them the largest nuclear reactors in the world.

The fuel flow for any given thrust level can be found from

. For the J-2, this is m = 1014 kN/(414 * 9.81), or about 250 kg/s. For the NERVA replacement considered above, this would be 121 kg/s. Remember that the mass of hydrogen is much lower than the hydrogen/oxygen mix in the J-2, where only about 1/6 of the mass is hydrogen. Since liquid hydrogen has a density of about 70 kg/m³, this represents a flow of about 1,725 litres per second, about three times that of the J-2. This requires additional plumbing but is by no means a serious problem; the famed F-1

. For the J-2, this is m = 1014 kN/(414 * 9.81), or about 250 kg/s. For the NERVA replacement considered above, this would be 121 kg/s. Remember that the mass of hydrogen is much lower than the hydrogen/oxygen mix in the J-2, where only about 1/6 of the mass is hydrogen. Since liquid hydrogen has a density of about 70 kg/m³, this represents a flow of about 1,725 litres per second, about three times that of the J-2. This requires additional plumbing but is by no means a serious problem; the famed F-1F-1 (rocket engine)

The F-1 is a rocket engine developed by Rocketdyne and used in the Saturn V. Five F-1 engines were used in the S-IC first stage of each Saturn V, which served as the main launch vehicle in the Apollo program. The F-1 is still the most powerful single-chamber liquid-fueled rocket engine ever...

had flow rates on the order of 2,500 l/s.

Finally, one must consider the design of the stage as a whole. The S-IVB carried just over 300,000 litres of fuel; 229,000 litres of liquid hydrogen (17,300 kg), and 72,700 litres of liquid oxygen (86,600 kg). The S-IVB uses a common bulkhead between the tanks, so removing it to produce a single larger tank would increase the total load only slightly. A new hydrogen-only nuclear stage would thus carry just over 300,000 litres in total (300 m³), or about 21,300 kg (47,000 lb). At 1,725 litres per second, this is a burn time of only 175 seconds, compared to about 500 in the original S-IVB (although some of this is at a lower power setting).

The total change in velocity, the so-called delta-v

Delta-v

In astrodynamics a Δv or delta-v is a scalar which takes units of speed. It is a measure of the amount of "effort" that is needed to change from one trajectory to another by making an orbital maneuver....

, can be found from the rocket equation, which is based on the starting and ending masses of the stage:

Where

is the initial mass with fuel,

is the initial mass with fuel,  the final mass without it, and Ve is as above. The total empty mass of the J-2 powered S-IVB was 13,311 kg, of which about 1,600 kg was the J-2 engine. Removing the inter-tank bulkhead to improve hydrogen storage would likely lighten this somewhat, perhaps to 10,500 kg for the tankage alone. The baseline NERVA designs were about 15,000 lb, or 6,800 kg, making the total unfueled mass (

the final mass without it, and Ve is as above. The total empty mass of the J-2 powered S-IVB was 13,311 kg, of which about 1,600 kg was the J-2 engine. Removing the inter-tank bulkhead to improve hydrogen storage would likely lighten this somewhat, perhaps to 10,500 kg for the tankage alone. The baseline NERVA designs were about 15,000 lb, or 6,800 kg, making the total unfueled mass ( ) of a "drop-in" S-IVB replacement around 17,300 kg. The lighter weight of the fuel more than makes up for the increase in engine weight; whereas the fueled mass (

) of a "drop-in" S-IVB replacement around 17,300 kg. The lighter weight of the fuel more than makes up for the increase in engine weight; whereas the fueled mass ( ) of the original S-IVB was 119,900 kg, for the nuclear-powered version this drops to only 38,600 kg.

) of the original S-IVB was 119,900 kg, for the nuclear-powered version this drops to only 38,600 kg.Following the formula above, this means the J-2 powered version generates a Δv of (414 s * 9.81) ln(119,900/13,311), or 8,900 m/s. The nuclear-powered version assumed above would be (850*9.81) ln(38,600/17,300), or 6,700 m/s. This drop in overall performance is due largely to the much higher "burnout" weight of the engine, and to smaller burn time due to the less-dense fuel. As a drop-in replacement, then, the nuclear engine does not seem to offer any advantages.

However, this simple examination ignores several important issues. For one, the new stage weighs considerably less than the older one, which means that the lower stages below it will leave the new upper stage at a higher velocity. This alone will make up for much of the difference in performance. More importantly, the comparison assumes that the stage would otherwise remain the same design overall. This is a bad assumption; one generally makes the upper stages as large as they can be given the throw-weight of the stages below them. In this case one would not make a drop-in version of the S-IVB, but a larger stage whose overall weight was the same as the S-IVB.

Following that line of reasoning, we can envision a replacement S-IVB stage that weighs 119,900 kg fully fueled, which would require much larger tanks. Assuming that the tankage mass triples, we have a m1 of 31,500 + 6,800 = 38,300 kg, and since we have fixed

at 119,900 kg, we get

at 119,900 kg, we getΔv = (850 s*9.81) ln(119,900/38,300), or 9,500 m/s. Thus, given the same mass as the original S-IVB, one can expect a moderate increase in overall performance using a nuclear engine. This stage would be about the same size as the S-II

S-II

The S-II was the second stage of the Saturn V rocket. It was built by North American Aviation. Using liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen it had five J-2 engines in a cross pattern...

stage used on the Saturn.

Of course this increase in tankage might not be easy to arrange. NASA actually considered a new S-IVB replacement, the S-N, built to be as physically large as possible while still being able to be built in the VAB

VAB

VAB is an initialism for several things:*Vehicle Assembly Building, a large building at NASA's Kennedy Space Center where vehicles are prepared for launch*Véhicule de l'Avant Blindé, a French wheeled armored personnel carrier...

. It weighed only 10,429 kg empty and 53,694 kg fueled (suggesting that structural loading is the dominant factor in stage mass, not the tankage). The combination of lower weight and higher performance improved the payload of the Saturn V as a whole from 127,000 kg delivered to low earth orbit

Low Earth orbit

A low Earth orbit is generally defined as an orbit within the locus extending from the Earth’s surface up to an altitude of 2,000 km...

(LEO) to 155,000 kg.

It is also worth considering the improvement in stage performance using the more advanced engine from the STNP program. Using the same S-IVB baseline, which does make sense in this case due to the lower thrust, we have an unfueled weight (

) of 10,500 + 1,650 = 12,150 kg, and a fueled mass (

) of 10,500 + 1,650 = 12,150 kg, and a fueled mass ( ) of 22,750 + 12,150 = 34,900 kg. Putting these numbers into the same formula we get a Δv of just over 10,000 m/s—remember, this is from the smaller S-IV-sized stage. Even with the lower thrust, the stage also has a thrust-to-weight ratio similar to the original S-IVB, 34,900 kg being pushed by 350 kN (10.0 N/kg or 1.02 lbf/lb), as opposed to 114,759 kg pushed by 1,112 kN (9.7 N/kg or 0.99 lbf/lb). The STNP-based S-IVB would indeed be a "drop-in replacement" for the original S-IVB, offering higher performance from much lower weight.

) of 22,750 + 12,150 = 34,900 kg. Putting these numbers into the same formula we get a Δv of just over 10,000 m/s—remember, this is from the smaller S-IV-sized stage. Even with the lower thrust, the stage also has a thrust-to-weight ratio similar to the original S-IVB, 34,900 kg being pushed by 350 kN (10.0 N/kg or 1.02 lbf/lb), as opposed to 114,759 kg pushed by 1,112 kN (9.7 N/kg or 0.99 lbf/lb). The STNP-based S-IVB would indeed be a "drop-in replacement" for the original S-IVB, offering higher performance from much lower weight.Risks

There is always an inherent possibility of atmospheric or orbital rocket failure which could result in a dispersal of radioactive material. Catastrophic failure, meaning the release of radioactive material into the environment, if it took place, would be the result of a containment breach. A containment breach could be the result of an impact with orbital debris, material failure due to uncontrolled fission, material imperfections or fatigue and human design flaws. A release of radioactive material while in flight could disperse radioactive debris over the Earth in a wide and unpredictable area. The zone of contamination and its concentration would be dependent on prevailing weather conditions and orbital parameters at the time of re-entry. The amount of contamination would depend on the size of the nuclear thermal rocket engine.Fuel elements in solid-core nuclear thermal rockets are designed to withstand very high temperatures (up to 3500K) and high pressures (up to 200 atm); hence, it is highly unlikely that a reactor's fuel elements would be spread over a wide area. They are composed of very strong materials, either carbon composites or carbides, and normally coated with zirconium hydride

Zirconium hydride

Zirconium hydride is an inorganic chemical compound, a hydride of zirconium with the formula ZrHx. Whereas x can be as large as 4, the most common values are between 1 and 2. Zirconium hydrides form upon reaction of zirconium metal with hydrogen gas. They behave as typical metals in terms of...

. The solid core NTR fuel itself is conventionally a small percentage of U-235 buried well inside an extremely strong carbon or carbide mixture. Unless the physically small reactors have been run for an extended period, the radioactivity of these elements is quite low and would pose a minimal hazard. The U.S. Rover program did in fact purposely destroy a Kiwi reactor to simulate a fall from altitude, and no radioactive material was released.

With current solid-core nuclear thermal rocket designs, it's possible that potentially radioactive fuel elements would be dispersed intact over a much smaller area. The overall hazard from the elements would be confined to near the launch site and would be much lower than the many open-air nuclear weapons tests of the 1950s.

See also

- In-situ resource utilizationIn-Situ Resource UtilizationIn space exploration, in-situ resource utilization describes the proposed use of resources found or manufactured on other astronomical objects to further the goals of a space mission....

- NERVANERVANERVA is an acronym for Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application, a joint program of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and NASA managed by the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office until both the program and the office ended at the end of 1972....

- Nuclear pulse propulsionNuclear pulse propulsionNuclear pulse propulsion is a proposed method of spacecraft propulsion that uses nuclear explosions for thrust. It was first developed as Project Orion by DARPA, after a suggestion by Stanislaw Ulam in 1947...

- Project OrionProject OrionProject Orion may refer to:*Project Orion was an engineering design study of spacecraft powered by nuclear pulse propulsion...

- Project PlutoProject PlutoProject Pluto was a United States government program to develop nuclear powered ramjet engines for use in cruise missiles. Two experimental engines were tested at the United States Department of Energy Nevada Test Site in 1961 and 1964.-History:...

- Project RoverProject RoverProject Rover was an American project to develop a nuclear thermal rocket. The program ran at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory from 1955 through 1972 and involved the Atomic Energy Commission, and NASA. The project was managed by the Space Nuclear Propulsion Office.Nuclear reactors for the...

- Project PrometheusProject PrometheusProject Prometheus was established in 2003 by NASA to develop nuclear-powered systems for long-duration space missions. This was NASA's first serious foray into nuclear spacecraft propulsion since the cancellation of the NERVA project in 1972...

- Project TimberwindProject TimberwindProject Timberwind aimed to develop nuclear thermal rockets. It was under the aegis of the Strategic Defence Initiative , later expanded into a larger design in the Space Thermal Nuclear Propulsion program...

- Spacecraft propulsionSpacecraft propulsionSpacecraft propulsion is any method used to accelerate spacecraft and artificial satellites. There are many different methods. Each method has drawbacks and advantages, and spacecraft propulsion is an active area of research. However, most spacecraft today are propelled by forcing a gas from the...

- UHTREXUHTREXThe Ultra High Temperature Reactor Experiment was an experimental gas cooled nuclear reactor experiment starting in 1959 and lasting about 12 years UHTREX was located at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. The reactor first achieved full power in 1969...

External links

- Dumbo (PDF)

- picture of the EX' engine

- Rover Nuclear Rocket Engine Program: Final Report - NASA 1991 (PDF)

- Neofuel Proposal for steam-based interplanetary drive, using off-earth ice deposits

- Project Prometheus: Beyond the Moon and Mars

- Nuclear propulsion

- RD-0410 USSR's nuclear rocket engine

- Soviet/russian solid core nuclear rocket engine