Perkinsus marinus

Encyclopedia

Perkinsus marinus is a prevalent pathogen

of oyster

s, causing massive mortality in oyster populations. The disease it causes is known as "Dermo" (or, more recently, as "Perkinsosis"),

and is characterized by proteolytic degradation of oyster tissues. Due to its negative effect on the oyster industry, parasitologists interested in helping oyster farmers are trying to find novel strategies to combat the disease. P. marinus are found in marine water, and grow especially well in warm waters during the summer months. Its genome has been sequenced by TIGR

, but as of Nov, 2010 no publication describing this can be found in PubMed

. The size of the genome is estimated to be ~86 megabases.

, and in particular belong to a group called the alveolate

s. The individual cells have two flagella, and have a partial polar ring used to attach to their hosts at the anterior. This is similar to structures found among the Apicomplexa

, and Perkinsus was previously classified with them. However, genetic studies show that P. marinus is probably closer to the dinoflagellate

s, which also appear to have modified polar rings. If Perkinsus is a dinoflagellate, it is a basal one.

The genome project of P. marinus, funded by NSF

-USDA

, was released in 2010 from The Institute for Genomic Research

in collaboration with The Center of Marine Biotechnology of the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute

. Currently (2010), no associated journal article can be found on PubMed

. It is unusual that genome projects complete without a publication being associated.

The closest relation to Perkinsus is the genus Parvilucifera. These form a sister group to the dinoflagellates.

The genus Colpodella

forms a sister clade to the Apicomplexia.

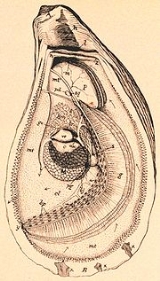

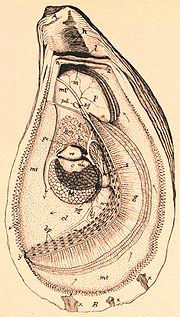

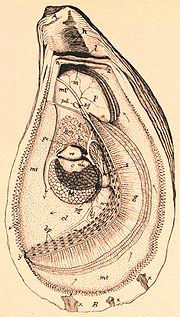

merozoite, or aplanospore stage depending on the authors' taxonomic preferences), at 2-3 µm in diameter.

A mature trophozoite stage (also known as mature-meront, mature-merozoite, or mature-aplanospore stage)

then forms with an appearance of a "signet-ring"

3-10 µm in diameter each containing a large eccentric vacuole

with

the nucleus

dislocated to the periphery of the cell

.

The tomont

stage (a.k.a. sporangia

or schizonts),

may form "rosettes"

, 4-15 µm in diameter, and containing 2, 4, 8, 16 or 32

developing immature trophozoites. Under certain conditions there may also be an additional stage known as a biflagellate

zoospore

.

Dermo infections are usually passed from oyster to oyster, though waterborne P. marinus may drift and

Dermo infections are usually passed from oyster to oyster, though waterborne P. marinus may drift and

help to spread the disease. Another possible vector is dormant infections in other shellfish. Perkinsosis is not known to present any danger to human consumers of oyster tissue.

oyster

s in the Gulf of Mexico

in 1950.

It was initially given the binomial designation Dermocystidium marinum from which the disease name Dermo originated.

By 1954 infections were also found in oysters

throughout the southeastern United States

.

The infection appeared in Long Island Sound

by the 1990s.

In recent years the parasite has spread to a wider range, including the Northeastern United States

up to Maine

, but has not yet been

reported in Canada

.

from Maine to Florida

,

and along the Gulf Coast of the United States

and Mexico

to the Yucatán Peninsula

. Within that range certain

places appear to suffer infection rates higher than other places. The pathogen was accidentally introduced into Pearl Harbor

, Hawaii

as

early as 1973. For example the Chesapeake Bay

appears to suffer high infection rates.

s of Crassostrea virginica or Eastern oyster

s.

Although experiments have been carried out with infections of

Crassostrea gigas (Pacific oyster

s), Crassostrea ariakensis (Suminoe oysters),

and Pinctada maxima (white or gold lipped pearl oyster

s)

those other bivalves appear to be less susceptible to the disease than C. virginica.

In experiments certain species of clam

s, abalone

, and scallop

s

appeared susceptible, but several mussel

s appeared immune.

They may also suffer from emaciation, gaping, retraction of the mantle away from the

edge of the shell, and stunted growth. In advanced stages of infection there may

be pus like areas in oyster soft tissues. The gross signs of infection are not

necessarily pathognomonic

of perkinsosis (in particular they are

also symptoms of MSX infection).

Dermo can be diagnosed by examination of a preparation from the oyster's anal-rectal tissues which have been cultured for 4 to 7 days in Ray's Fluid Thioglycollate Medium

(RFTM). After the culture period the tissue sample is then stained with Lugol's iodine

. In a light microscope

P. marinus cells will appear as blue to black stained spheres.

There may be commercial or government agencies that are able to provide diagnostic services.

P. chesapeaki infects Baltic clam (Macoma balthica

), soft shell clam (Mya arenaria), the stout razor clam (Tagelus plebeius)

P. marinus infects the pleasure oyster (Crassostrea corteziensis), Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica), Baltic clam (Macoma balthica

), hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria), soft shell clam (Mya arenaria), white pearl oyster (Pinctada maxima)

P. mediterraneus infects the European flat oyster (Ostrea edulis).

P. olseni infects several clam species: New Zealand cockle (Austrovenus stutchburyi

), Crassostrea ariakensis, venerid clam (Pitar rostrata), Venus clam (Protothaca jedoensis), grooved carpet shell (Ruditapes decussatus), Manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum), Tapes decussatus and the boring clam (Tridacna crocea). It is found in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, New Zealand, Portuguese, Spanish and Uruguayan waters.

The closest relations to this genus are the genera Oxyrrhis

, Parvilucifera and Rastrimonas. The ellobiopsids may also be related.

The genus Perkinsoide may be related.

Members of this genus have nine chromosome

s.

Pathogen

A pathogen gignomai "I give birth to") or infectious agent — colloquially, a germ — is a microbe or microorganism such as a virus, bacterium, prion, or fungus that causes disease in its animal or plant host...

of oyster

Oyster

The word oyster is used as a common name for a number of distinct groups of bivalve molluscs which live in marine or brackish habitats. The valves are highly calcified....

s, causing massive mortality in oyster populations. The disease it causes is known as "Dermo" (or, more recently, as "Perkinsosis"),

and is characterized by proteolytic degradation of oyster tissues. Due to its negative effect on the oyster industry, parasitologists interested in helping oyster farmers are trying to find novel strategies to combat the disease. P. marinus are found in marine water, and grow especially well in warm waters during the summer months. Its genome has been sequenced by TIGR

The Institute for Genomic Research

The Institute for Genomic Research was a non-profit genomics research institute founded in 1992 by Craig Venter in Rockville, Maryland, United States. It is now a part of the J. Craig Venter Institute.-History:...

, but as of Nov, 2010 no publication describing this can be found in PubMed

PubMed

PubMed is a free database accessing primarily the MEDLINE database of references and abstracts on life sciences and biomedical topics. The United States National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health maintains the database as part of the Entrez information retrieval system...

. The size of the genome is estimated to be ~86 megabases.

Taxonomy

P. marinus are protozoaProtozoa

Protozoa are a diverse group of single-cells eukaryotic organisms, many of which are motile. Throughout history, protozoa have been defined as single-cell protists with animal-like behavior, e.g., movement...

, and in particular belong to a group called the alveolate

Alveolate

The alveolates are a major line of protists.-Phyla:There are four phyla, which are very divergent in form, but are now known to be close relatives based on various ultrastructural and genetic similarities:...

s. The individual cells have two flagella, and have a partial polar ring used to attach to their hosts at the anterior. This is similar to structures found among the Apicomplexa

Apicomplexa

The Apicomplexa are a large group of protists, most of which possess a unique organelle called apicoplast and an apical complex structure involved in penetrating a host's cell. They are unicellular, spore-forming, and exclusively parasites of animals. Motile structures such as flagella or...

, and Perkinsus was previously classified with them. However, genetic studies show that P. marinus is probably closer to the dinoflagellate

Dinoflagellate

The dinoflagellates are a large group of flagellate protists. Most are marine plankton, but they are common in fresh water habitats as well. Their populations are distributed depending on temperature, salinity, or depth...

s, which also appear to have modified polar rings. If Perkinsus is a dinoflagellate, it is a basal one.

The genome project of P. marinus, funded by NSF

National Science Foundation

The National Science Foundation is a United States government agency that supports fundamental research and education in all the non-medical fields of science and engineering. Its medical counterpart is the National Institutes of Health...

-USDA

United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture is the United States federal executive department responsible for developing and executing U.S. federal government policy on farming, agriculture, and food...

, was released in 2010 from The Institute for Genomic Research

The Institute for Genomic Research

The Institute for Genomic Research was a non-profit genomics research institute founded in 1992 by Craig Venter in Rockville, Maryland, United States. It is now a part of the J. Craig Venter Institute.-History:...

in collaboration with The Center of Marine Biotechnology of the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute

University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute

Formed in 1985, the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute is part of the University System of Maryland. It was created to provide a unified focus for Maryland's biotechnology research and education.-About UMBI:...

. Currently (2010), no associated journal article can be found on PubMed

PubMed

PubMed is a free database accessing primarily the MEDLINE database of references and abstracts on life sciences and biomedical topics. The United States National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health maintains the database as part of the Entrez information retrieval system...

. It is unusual that genome projects complete without a publication being associated.

The closest relation to Perkinsus is the genus Parvilucifera. These form a sister group to the dinoflagellates.

The genus Colpodella

Colpodella

Colpodella is a genus of alveolates comprising 5 species, and two further possible species: They share all the synapomorphies of apicomplexans, but are free-living, rather than parasitic. This genus was previously known as Spiromonas...

forms a sister clade to the Apicomplexia.

Morphology

P. marinus may start out in an immature trophozoite stage (also referred to as a meront,merozoite, or aplanospore stage depending on the authors' taxonomic preferences), at 2-3 µm in diameter.

A mature trophozoite stage (also known as mature-meront, mature-merozoite, or mature-aplanospore stage)

then forms with an appearance of a "signet-ring"

3-10 µm in diameter each containing a large eccentric vacuole

Vacuole

A vacuole is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in all plant and fungal cells and some protist, animal and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic molecules including enzymes in solution, though in certain...

with

the nucleus

Cell nucleus

In cell biology, the nucleus is a membrane-enclosed organelle found in eukaryotic cells. It contains most of the cell's genetic material, organized as multiple long linear DNA molecules in complex with a large variety of proteins, such as histones, to form chromosomes. The genes within these...

dislocated to the periphery of the cell

Cell (biology)

The cell is the basic structural and functional unit of all known living organisms. It is the smallest unit of life that is classified as a living thing, and is often called the building block of life. The Alberts text discusses how the "cellular building blocks" move to shape developing embryos....

.

The tomont

Tomont

Tomont is a protozoan, especially of the Apicomplexa, in the active stage of its life cycle, which develops into an encyst....

stage (a.k.a. sporangia

Sporangium

A sporangium is an enclosure in which spores are formed. It can be composed of a single cell or can be multicellular. All plants, fungi, and many other lineages form sporangia at some point in their life cycle...

or schizonts),

may form "rosettes"

Rosette (botany)

In botany, a rosette is a circular arrangement of leaves, with all the leaves at a single height.Though rosettes usually sit near the soil, their structure is an example of a modified stem.-Function:...

, 4-15 µm in diameter, and containing 2, 4, 8, 16 or 32

developing immature trophozoites. Under certain conditions there may also be an additional stage known as a biflagellate

Intraflagellar transport

Intraflagellar transport or IFT is a bidirectional motility along axonemal microtubules that is essential for the formation and maintenance of most eukaryotic cilia and flagella. It is thought to be required to build all cilia that assemble within a membrane projection from the cell surface...

zoospore

Zoospore

A zoospore is a motile asexual spore that uses a flagellum for locomotion. Also called a swarm spore, these spores are created by some algae, bacteria and fungi to propagate themselves.-Flagella:...

.

Dermo

help to spread the disease. Another possible vector is dormant infections in other shellfish. Perkinsosis is not known to present any danger to human consumers of oyster tissue.

History

P. marinus was first identified as a pathogen of theoyster

Oyster

The word oyster is used as a common name for a number of distinct groups of bivalve molluscs which live in marine or brackish habitats. The valves are highly calcified....

s in the Gulf of Mexico

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico is a partially landlocked ocean basin largely surrounded by the North American continent and the island of Cuba. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States, on the southwest and south by Mexico, and on the southeast by Cuba. In...

in 1950.

It was initially given the binomial designation Dermocystidium marinum from which the disease name Dermo originated.

By 1954 infections were also found in oysters

throughout the southeastern United States

Southern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

.

The infection appeared in Long Island Sound

Long Island Sound

Long Island Sound is an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean, located in the United States between Connecticut to the north and Long Island, New York to the south. The mouth of the Connecticut River at Old Saybrook, Connecticut, empties into the sound. On its western end the sound is bounded by the Bronx...

by the 1990s.

In recent years the parasite has spread to a wider range, including the Northeastern United States

Northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States is a region of the United States as defined by the United States Census Bureau.-Composition:The region comprises nine states: the New England states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont; and the Mid-Atlantic states of New...

up to Maine

Maine

Maine is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the east and south, New Hampshire to the west, and the Canadian provinces of Quebec to the northwest and New Brunswick to the northeast. Maine is both the northernmost and easternmost...

, but has not yet been

reported in Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

.

Range

P. marinus infections have appeared primarily along the East coast of the United StatesEast Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, refers to the easternmost coastal states in the United States, which touch the Atlantic Ocean and stretch up to Canada. The term includes the U.S...

from Maine to Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

,

and along the Gulf Coast of the United States

Gulf Coast of the United States

The Gulf Coast of the United States, sometimes referred to as the Gulf South, South Coast, or 3rd Coast, comprises the coasts of American states that are on the Gulf of Mexico, which includes Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida and are known as the Gulf States...

and Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

to the Yucatán Peninsula

Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula, in southeastern Mexico, separates the Caribbean Sea from the Gulf of Mexico, with the northern coastline on the Yucatán Channel...

. Within that range certain

places appear to suffer infection rates higher than other places. The pathogen was accidentally introduced into Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor, known to Hawaiians as Puuloa, is a lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. Much of the harbor and surrounding lands is a United States Navy deep-water naval base. It is also the headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Fleet...

, Hawaii

Hawaii

Hawaii is the newest of the 50 U.S. states , and is the only U.S. state made up entirely of islands. It is the northernmost island group in Polynesia, occupying most of an archipelago in the central Pacific Ocean, southwest of the continental United States, southeast of Japan, and northeast of...

as

early as 1973. For example the Chesapeake Bay

Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States. It lies off the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by Maryland and Virginia. The Chesapeake Bay's drainage basin covers in the District of Columbia and parts of six states: New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West...

appears to suffer high infection rates.

Pathology

P. marinus primarily infects hemocyteHemocyte

A hemocyte is a cell that plays a role in the immune system of invertebrates. It is found within the hemolymph.Hemocytes are phagocytes of invertebrates....

s of Crassostrea virginica or Eastern oyster

Eastern oyster

The eastern oyster — also called Atlantic oyster or Virginia oyster — is a species of true oyster native to the eastern seaboard and Gulf of Mexico coast of North America. It is also farmed in Puget Sound, Washington, where it is known as the Totten Inlet Virginica. Eastern oysters are and have...

s.

Although experiments have been carried out with infections of

Crassostrea gigas (Pacific oyster

Pacific oyster

The Pacific oyster, Japanese oyster or Miyagi oyster , is an oyster native to the Pacific coast of Asia. It has become an introduced species in North America, Australia, Europe, and New Zealand.- Etymology :...

s), Crassostrea ariakensis (Suminoe oysters),

and Pinctada maxima (white or gold lipped pearl oyster

Pearl oyster

Pearl oysters are saltwater clams, marine bivalve molluscs of the genus Pinctada in the family Pteriidae. They have a strong inner shell layer composed of nacre, also known as "mother of pearl"....

s)

those other bivalves appear to be less susceptible to the disease than C. virginica.

In experiments certain species of clam

Clam

The word "clam" can be applied to freshwater mussels, and other freshwater bivalves, as well as marine bivalves.In the United States, "clam" can be used in several different ways: one, as a general term covering all bivalve molluscs...

s, abalone

Abalone

Abalone , from aulón, are small to very large-sized edible sea snails, marine gastropod molluscs in the family Haliotidae and the genus Haliotis...

, and scallop

Scallop

A scallop is a marine bivalve mollusk of the family Pectinidae. Scallops are a cosmopolitan family, found in all of the world's oceans. Many scallops are highly prized as a food source...

s

appeared susceptible, but several mussel

Mussel

The common name mussel is used for members of several families of clams or bivalvia mollusca, from saltwater and freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other edible clams, which are often more or less rounded or oval.The...

s appeared immune.

Identification and diagnosis

Infected oysters may have digestive glands that appear paler than uninfected oysters.They may also suffer from emaciation, gaping, retraction of the mantle away from the

edge of the shell, and stunted growth. In advanced stages of infection there may

be pus like areas in oyster soft tissues. The gross signs of infection are not

necessarily pathognomonic

Pathognomonic

Pathognomonic is a term, often used in medicine, that means characteristic for a particular disease. A pathognomonic sign is a particular sign whose presence means that a particular disease is present beyond any doubt...

of perkinsosis (in particular they are

also symptoms of MSX infection).

Dermo can be diagnosed by examination of a preparation from the oyster's anal-rectal tissues which have been cultured for 4 to 7 days in Ray's Fluid Thioglycollate Medium

Thioglycollate broth

Fluid thioglycolate media or thioglycolate broth is a multi-purpose enriched differentiating media used primarily to differentiate oxygen requirement levels of various organisms. Oxygen levels throughout the media are reduced via reaction with sodium thioglycolate. This produces a range of...

(RFTM). After the culture period the tissue sample is then stained with Lugol's iodine

Lugol's iodine

Lugol's iodine, also known as Lugol's solution, first made in 1829, is a solution of elemental iodine and potassium iodide in water, named after the French physician J.G.A. Lugol. Lugol's iodine solution is often used as an antiseptic and disinfectant, for emergency disinfection of drinking water,...

. In a light microscope

Microscope

A microscope is an instrument used to see objects that are too small for the naked eye. The science of investigating small objects using such an instrument is called microscopy...

P. marinus cells will appear as blue to black stained spheres.

There may be commercial or government agencies that are able to provide diagnostic services.

Genus

There are other members in this genus.- Perkinsus beihaiensis

- Perkinsus chesapeaki

- Perkinsus honshuensis

- Perkinsus mediterraneus

- Perkinsus olseni (synonym Perkinsus atlanticus)

P. chesapeaki infects Baltic clam (Macoma balthica

Macoma balthica

Macoma balthica, commonly called the Baltic macoma, Baltic clam or Baltic tellin, is a small saltwater clam, a marine bivalve mollusk in the family Tellinidae ....

), soft shell clam (Mya arenaria), the stout razor clam (Tagelus plebeius)

P. marinus infects the pleasure oyster (Crassostrea corteziensis), Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica), Baltic clam (Macoma balthica

Macoma balthica

Macoma balthica, commonly called the Baltic macoma, Baltic clam or Baltic tellin, is a small saltwater clam, a marine bivalve mollusk in the family Tellinidae ....

), hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria), soft shell clam (Mya arenaria), white pearl oyster (Pinctada maxima)

P. mediterraneus infects the European flat oyster (Ostrea edulis).

P. olseni infects several clam species: New Zealand cockle (Austrovenus stutchburyi

Austrovenus stutchburyi

Austrovenus stutchburyi, common name the New Zealand cockle or New Zealand little neck clam, is an edible saltwater clam, a marine bivalve mollusc in the family Veneridae, the Venus clams.-References:* Powell A. W...

), Crassostrea ariakensis, venerid clam (Pitar rostrata), Venus clam (Protothaca jedoensis), grooved carpet shell (Ruditapes decussatus), Manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum), Tapes decussatus and the boring clam (Tridacna crocea). It is found in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, New Zealand, Portuguese, Spanish and Uruguayan waters.

The closest relations to this genus are the genera Oxyrrhis

Oxyrrhis

Oxyrrhis is a genus of dinoflagellate. It includes the species Oxyrrhis marina....

, Parvilucifera and Rastrimonas. The ellobiopsids may also be related.

The genus Perkinsoide may be related.

Members of this genus have nine chromosome

Chromosome

A chromosome is an organized structure of DNA and protein found in cells. It is a single piece of coiled DNA containing many genes, regulatory elements and other nucleotide sequences. Chromosomes also contain DNA-bound proteins, which serve to package the DNA and control its functions.Chromosomes...

s.

Other sources

- Who Killed Crassostrea virginica? The Fall and Rise of Chesapeake Bay Oysters (2011), Maryland Sea Grant College (60 min. film)