Regulamentul Organic

Encyclopedia

Romanian language

Romanian Romanian Romanian (or Daco-Romanian; obsolete spellings Rumanian, Roumanian; self-designation: română, limba română ("the Romanian language") or românește (lit. "in Romanian") is a Romance language spoken by around 24 to 28 million people, primarily in Romania and Moldova...

name, translated as Organic Statute or Organic Regulation; , Russian

Russian language

Russian is a Slavic language used primarily in Russia, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. It is an unofficial but widely spoken language in Ukraine, Moldova, Latvia, Turkmenistan and Estonia and, to a lesser extent, the other countries that were once constituent republics...

: Oрганический регламент, Organichesky reglament) was a quasi-constitutional

Constitution of Romania

The 1991 Constitution of Romania, adopted on 21 November 1991, voted in the referendum of 8 December 1991 and introduced on the same day, is the current fundamental law that establishes the structure of the government of Romania, the rights and obligations of the country's citizens, and its mode...

organic law

Organic law

An organic or fundamental law is a law or system of laws which forms the foundation of a government, corporation or other organization's body of rules. A constitution is a particular form of organic law for a sovereign state....

enforced in 1834–1835 by the Imperial Russian

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

authorities in Moldavia

Moldavia

Moldavia is a geographic and historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester river...

and Wallachia

Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians...

(the two Danubian Principalities

Danubian Principalities

Danubian Principalities was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th century. The term was coined in the Habsburg Monarchy after the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in order to designate an area on the lower Danube with a common...

that were to become the basis of the modern Romanian state

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

). The onset of a common Russian protectorate

Protectorate

In history, the term protectorate has two different meanings. In its earliest inception, which has been adopted by modern international law, it is an autonomous territory that is protected diplomatically or militarily against third parties by a stronger state or entity...

which lasted until 1854, and itself in force until 1858, the document signified a partial confirmation of traditional government (including rule by the hospodar

Hospodar

Hospodar or gospodar is a term of Slavonic origin, meaning "lord" or "master".The rulers of Wallachia and Moldavia were styled hospodars in Slavic writings from the 15th century to 1866. Hospodar was used in addition to the title voivod...

s). Conservative

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

in its scope, it also engendered a period of unprecedented reforms which provided a setting for the Westernization

Westernization

Westernization or Westernisation , also occidentalization or occidentalisation , is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in such matters as industry, technology, law, politics, economics, lifestyle, diet, language, alphabet,...

of local society. The Regulament offered the two Principalities their first common system of government.

Background

The two principalities, owing tributeTribute

A tribute is wealth, often in kind, that one party gives to another as a sign of respect or, as was often the case in historical contexts, of submission or allegiance. Various ancient states, which could be called suzerains, exacted tribute from areas they had conquered or threatened to conquer...

and progressively ceding political control to the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

since the Middle Ages

Romania in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages in Romania began with the withdrawal of the Mongols, the last of the migrating populations to invade the territory of modern Romania, after their attack of 1241–1242...

, had been subject to frequent Russian interventions as early as the Russo-Turkish War (1710–1711), when a Russian army penetrated Moldavia and Emperor Peter the Great

Peter I of Russia

Peter the Great, Peter I or Pyotr Alexeyevich Romanov Dates indicated by the letters "O.S." are Old Style. All other dates in this article are New Style. ruled the Tsardom of Russia and later the Russian Empire from until his death, jointly ruling before 1696 with his half-brother, Ivan V...

probably established links with the Wallachians. Eventually, the Ottomans enforced a tighter control on the region, effected under Phanariote

Phanariotes

Phanariots, Phanariotes, or Phanariote Greeks were members of those prominent Greek families residing in Phanar , the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople, where the Ecumenical Patriarchate is situated.For all their cosmopolitanism and often Western education, the Phanariots were...

hospodars (who were appointed directly by the Porte). Ottoman rule over the region remained contested by competition from Russia, which, as an Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church, is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece,...

empire with claim to a Byzantine

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire was the Eastern Roman Empire during the periods of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, centred on the capital of Constantinople. Known simply as the Roman Empire or Romania to its inhabitants and neighbours, the Empire was the direct continuation of the Ancient Roman State...

heritage, exercised notable influence over locals. At the same time, the Porte made several concessions to the rulers and boyars of Moldavia and Wallachia, as a means to ensure the preservation of its rule.

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

Treaty of Kucuk Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca was signed on 21 July 1774, in Küçük Kaynarca , Dobruja between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire after the Ottoman Empire was defeated in the...

, signed in 1774 between the Ottomans and Russians, gave Russia the right to intervene on behalf of Eastern Orthodox Ottoman subjects in general, a right which it used to sanction Ottoman interventions in the Principalities in particular. Thus, Russia intervened to preserve reigns of hospodars who had lost Ottoman approval in the context of the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

(the casus belli

Casus belli

is a Latin expression meaning the justification for acts of war. means "incident", "rupture" or indeed "case", while means bellic...

for the 1806–12 conflict), and remained present in the Danubian states, vying for influence with the Austrian Empire

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

, well into the 19th century and annexing Moldavia's Bessarabia

Bessarabia

Bessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

in 1812.

Despite the influx of Greeks

Greeks in Romania

There has been a Greek presence in Romania for at least 27 centuries. At times, as during the Phanariote era, this presence has amounted to hegemony; at other times , the Greeks have simply been one among the many ethnic minorities in Romania.-Ancient and Medieval Period:The Greek presence in what...

, arriving in the Principalities as a new bureaucracy

Bureaucracy

A bureaucracy is an organization of non-elected officials of a governmental or organization who implement the rules, laws, and functions of their institution, and are occasionally characterized by officialism and red tape.-Weberian bureaucracy:...

favored by the hospodars, the traditional Estates of the realm

Estates of the realm

The Estates of the realm were the broad social orders of the hierarchically conceived society, recognized in the Middle Ages and Early Modern period in Christian Europe; they are sometimes distinguished as the three estates: the clergy, the nobility, and commoners, and are often referred to by...

(the Divan) remained under the tight control of a number of high boyar

Boyar

A boyar, or bolyar , was a member of the highest rank of the feudal Moscovian, Kievan Rus'ian, Bulgarian, Wallachian, and Moldavian aristocracies, second only to the ruling princes , from the 10th century through the 17th century....

families, who, while intermarrying with members of newly arrived communities, opposed reformist attempts — and successfully preserved their privilege

Privilege

A privilege is a special entitlement to immunity granted by the state or another authority to a restricted group, either by birth or on a conditional basis. It can be revoked in certain circumstances. In modern democratic states, a privilege is conditional and granted only after birth...

s by appealing against their competitors to both Istanbul

Istanbul

Istanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

and Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

.

Consul (representative)

The political title Consul is used for the official representatives of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, and to facilitate trade and friendship between the peoples of the two countries...

representing European powers directly interested in observing local developments (Russia, the Austrian Empire, and France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

; later, British

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

and Prussian

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

ones were opened as well). An additional way for consuls to exercise particular policies was the awarding of a privileged status and protection to various individuals, who were known as sudiţi

Suditi

For the commune in Ialomiţa County, see Sudiţi, Ialomiţa. For the villages in Buzău County, see Gherăseni and Poşta Câlnău.The Sudiţi were inhabitants of the Danubian Principalities who, for the latter stage of the 18th and a large part of the 19th century...

("subjects", in the language of the time) of one or the other of the foreign powers.

A seminal event occurred in 1821, when the rise of Greek nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

in various parts of the Balkans

Balkans

The Balkans is a geopolitical and cultural region of southeastern Europe...

in connection with the Greek War of Independence

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution was a successful war of independence waged by the Greek revolutionaries between...

led to occupation of the two states by the Filiki Eteria

Filiki Eteria

thumb|right|200px|The flag of the Filiki Eteria.Filiki Eteria or Society of Friends was a secret 19th century organization, whose purpose was to overthrow Ottoman rule over Greece and to establish an independent Greek state. Society members were mainly young Phanariot Greeks from Russia and local...

, a Greek secret society

Secret society

A secret society is a club or organization whose activities and inner functioning are concealed from non-members. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence agencies or guerrilla insurgencies, which hide their...

who sought, and initially obtained, Russian approval. A mere takeover of the government in Moldavia, the Eterist expedition met a more complex situation in Wallachia, where a regency

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

of high boyars attempted to have the anti-Ottoman Greek nationalists confirm both their rule and the rejection of Phanariote institutions. A compromise was achieved through their common support for Tudor Vladimirescu

Tudor Vladimirescu

Tudor Vladimirescu was a Wallachian Romanian revolutionary hero, the leader of the Wallachian uprising of 1821 and of the Pandur militia. He is also known as Tudor din Vladimiri or — occasionally — as Domnul Tudor .-Background:Tudor was born in Vladimiri, Gorj County in a family of landed peasants...

, an Oltenia

Oltenia

Oltenia is a historical province and geographical region of Romania, in western Wallachia. It is situated between the Danube, the Southern Carpathians and the Olt river ....

n pandur

Pandur

Pandur can refer to:* Pandurs, Balkan Slavic guerrilla fighters* Pandur, an armoured personnel carrier:* Pandur I 6x6* Pandur II 8x8* The Sumerian term for long-necked lutes...

leader who had already instigated an anti-Phanariote rebellion

Wallachian uprising of 1821

The Wallachian uprising of 1821 was an uprising in Wallachia against Ottoman rule which took place during 1821.-Background:...

(as one of the Russian sudiţi, it was hoped that Vladimirescu could assure Russia that the revolt was not aimed against its influence). However, the eventual withdrawal of Russian support made Vladimirescu seek a new agreement with the Ottomans, leaving him to be executed by an alliance of Eterists and weary locals (alarmed by his new anti-boyar program); after the Ottomans invaded the region and crushed the Eteria, the boyars, still perceived as a third party, obtained from the Porte an end to the Phanariote system

Akkerman Convention and Treaty of Adrianople

Ioan Sturdza

Ioan Sturdza was a Prince of Moldavia and the most famous descendant of Alexandru Sturdza...

as Prince of Moldavia and Grigore IV Ghica

Grigore IV Ghica

Grigore IV Ghica or Grigore Dimitrie Ghica was Prince of Wallachia between 1822 and 1828. A member of the Ghica family, Grigore IV was the brother of Alexandru Ghica and the uncle of Dora d'Istria....

as Prince of Wallachia — were, in essence, short-lived: although the patron-client relation

Clientelism

Clientelism is a term used to describe a political system at the heart of which is an assyemtric relationship between groups of political actors described as patrons and clients...

between Phanariote hospodars and a foreign ruler was never revived, Sturdza and Ghica were deposed by the Russian military intervention during the Russo-Turkish War, 1828–1829. Sturdza's time on the throne was marked by an important internal development: the last in a series of constitutional proposals, advanced by boyars as a means to curb princely authority, ended in a clear conflict between the rapidly decaying class of low-ranking boyars (already forming the upper level of the middle class

Middle class

The middle class is any class of people in the middle of a societal hierarchy. In Weberian socio-economic terms, the middle class is the broad group of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the working class and upper class....

rather than a segment of the traditional nobility) and the high-ranking families who had obtained the decisive say in politics. The proponent, Ionică Tăutu

Ionica Tautu

Ionică Tăutu was a Moldavian low-ranking boyar, Enlightenment-inspired pamphleteer, and craftsman .-Constitutional project:...

, was defeated in the Divan after the Russian consul sided with the conservatives (expressing the official view that the aristocratic-republican

Mixed government

Mixed government, also known as a mixed constitution, is a form of government that integrates elements of democracy, aristocracy, and monarchy. In a mixed government, some issues are decided by the majority of the people, some other issues by few, and some other issues by a single person...

and liberal

Liberalism and radicalism in Romania

This article gives an overview of Liberalism and Radicalism in Romania. It is limited to liberal parties with substantial support, mainly proved by having had a representation in parliament. The sign ⇒ denotes another party in this scheme...

aims of the document could have threatened international conventions in place).

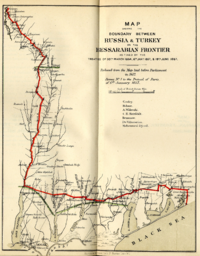

On October 7, 1826, the Ottoman Empire — anxious to prevent Russia's intervention in the Greek Independence War — negotiatied with it a new status for the region in Akkerman

Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi

Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi is a city situated on the right bank of the Dniester Liman in the Odessa Oblast of southwestern Ukraine, in the historical region of Bessarabia...

, one which conceded to several requests of the inhabitants: the resulting Akkerman Convention was the first official document to nullify the principle of Phanariote reigns, instituting seven-year terms for new princes elected by the respective Divans, and awarding the two countries the right to engage in unresticted international trade

International trade

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories. In most countries, such trade represents a significant share of gross domestic product...

(as opposed to the tradition of limitations and Ottoman protectionism

Protectionism

Protectionism is the economic policy of restraining trade between states through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, restrictive quotas, and a variety of other government regulations designed to allow "fair competition" between imports and goods and services produced domestically.This...

, it only allowed Istanbul to impose its priorities in the grain trade

Grain trade

The grain trade refers the local and international trade in cereals and other food grains such as wheat, maize, and rice.-History:The grain trade is probably nearly as old as grain growing, going back the Neolithic Revolution . Wherever there is a scarcity of land The grain trade refers the local...

). The convention also made the first mention of new Statutes, enforced by both powers as governing documents, which were not drafted until after the war — although both Sturdza and Ghica had appointed commissions charged with adopting such projects.

The Russian military presence on the Principalities' soil was inaugurated in the first days of the war: by late April 1828, the Russian army of Peter Wittgenstein

Peter Wittgenstein

Ludwig Adolph Peter, Prince Wittgenstein was a Russian Field Marshal distinguished for his services in the Napoleonic wars.-Life:...

had reached the Danube

Danube

The Danube is a river in the Central Europe and the Europe's second longest river after the Volga. It is classified as an international waterway....

(in May, it entered present-day Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

). The campaign, prolonged for the following year and coinciding with devastating bubonic plague

Bubonic plague

Plague is a deadly infectious disease that is caused by the enterobacteria Yersinia pestis, named after the French-Swiss bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin. Primarily carried by rodents and spread to humans via fleas, the disease is notorious throughout history, due to the unrivaled scale of death...

and cholera

Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

epidemics (which together killed around 1.6% of the population in both countries), soon became a drain on local economy: according to British observers, the Wallachian state was required to indebt itself to European creditors for a total sum of ten million piastre

Piastre

The piastre or piaster refers to a number of units of currency. The term originates from the Italian for 'thin metal plate'. The name was applied to Spanish and Latin American pieces of eight, or pesos, by Venetian traders in the Levant in the 16th century.These pesos, minted continually for...

s, in order to provide for the Russian army's needs. Accusations of widespread plunder were made by the French author Marc Girardin

Marc Girardin

Saint-Marc Girardin was a French politician and man of letters, whose real name was Marc Girardin.-Biography:...

, who travelled in the region during the 1830s; Girardin alleged that Russian troops had confiscated virtually all cattle for their needs, and that Russian officers had insulted the political class by publicly stating that, in case the supply in oxen was to prove insufficient, boyars were to be tied to carts in their place — an accusation backed by Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica was a Romanian revolutionary, mathematician, diplomat and twice Prime Minister of Romania . He was a full member of the Romanian Academy and its president for four times...

in his recollections. He also recorded a mounting dissatifaction with the new rule, mentioning that peasants were especially upset by the continuous maneuvers of troops inside the Principalities' borders. Overall, Russophilia

Russophilia

Russophilia is the love of Russia and/or Russians. The term is used in two basic contexts: in international politics and in cultural context. "Russophilia" and "Russophilic" are the terms used to denote pro-Russian sentiments, usually in politics and literature...

in the two Principalities appears to have suffered a major blow. Despite the confiscations, statistics of the time indicated that the pace of growth in heads of cattle remained steady (a 50% growth appears to have occurred between 1831 and 1837).

The Treaty of Adrianople

Treaty of Adrianople

The Peace Treaty of Adrianople concluded the Russo-Turkish War, 1828-1829 between Russia and the Ottoman Empire. It was signed on September 14, 1829 in Adrianople by Russia's Count Alexey Fyodorovich Orlov and by Turkey's Abdul Kadyr-bey...

, signed on September 14, 1829, confirmed both the Russian victory and the provisions of the Akkerman Convention, partly amended to reflect the Russian political ascendancy over the area. Furthermore, Wallachia's southern border was settled on the Danube thalweg

Thalweg

Thalweg in geography and fluvial geomorphology signifies the deepest continuous inline within a valley or watercourse system.-Hydrology:In hydrological and fluvial landforms, the thalweg is a line drawn to join the lowest points along the entire length of a stream bed or valley in its downward...

, and the state was given control over the previously Ottoman-ruled ports of Brăila

Braila

Brăila is a city in Muntenia, eastern Romania, a port on the Danube and the capital of Brăila County, in the close vicinity of Galaţi.According to the 2002 Romanian census there were 216,292 people living within the city of Brăila, making it the 10th most populous city in Romania.-History:A...

, Giurgiu

Giurgiu

Giurgiu is the capital city of Giurgiu County, Romania, in the Greater Wallachia. It is situated amid mud-flats and marshes on the left bank of the Danube facing the Bulgarian city of Rousse on the opposite bank. Three small islands face the city, and a larger one shelters its port, Smarda...

, and Turnu Măgurele

Turnu Magurele

Turnu Măgurele is a city in Teleorman County, Romania . Developed nearby the site once occupied by the medieval port of Turnu, it is situated north-east of the confluence between the Olt River and the Danube....

. The freedom of commerce (which consisted mainly of grain exports from the region) and freedom of navigation on the river and on the Black Sea

Black Sea

The Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

were passed into law, allowing for the creation of naval fleet

Naval fleet

A fleet, or naval fleet, is a large formation of warships, and the largest formation in any navy. A fleet at sea is the direct equivalent of an army on land....

s in both Principalities in the following years, as well as for a more direct contact with European traders, with the confirmation of the Moldavia and Wallachia's commercial privileges first stipulated at Akkerman (alongside the tight links soon established with Austrian and Sardinian traders, the first French ships visited Wallachia in 1830).

Russian occupation over Moldavia and Wallachia (as well as the Bulgarian town of Silistra

Silistra

Silistra is a port city of northeastern Bulgaria, lying on the southern bank of the lower Danube at the country's border with Romania. Silistra is the administrative centre of Silistra Province and one of the important cities of the historical region of Southern Dobrudzha...

) was prolonged pending the payment of war reparations by the Ottomans. Emperor Nicholas I

Nicholas I of Russia

Nicholas I , was the Emperor of Russia from 1825 until 1855, known as one of the most reactionary of the Russian monarchs. On the eve of his death, the Russian Empire reached its historical zenith spanning over 20 million square kilometers...

assigned Fyodor Pahlen

Fyodor Petrovich Pahlen

Count Fyodor Petrovich Pahlen was a Russian diplomat and administrator.-Biography:Fyodor was the youngest son of Petr Alekseevich Pahlen, a prominent Russian courtier. He worked at Russian diplomatic missions in Sweden, France and Great Britain...

as governor over the two countries before the actual peace, as the first in a succession of three Plenipotentiary Presidents of the Divans in Moldavia and Wallachia, and official supervisor of the two commissions charged with drafting the Statutes. The bodies, having for secretaries Gheorghe Asachi

Gheorghe Asachi

Gheorghe Asachi was a Moldavian-born Romanian prose writer, poet, painter, historian, dramatist and translator. An Enlightenment-educated polymath and polyglot, he was one of the most influential people of his generation...

in Moldavia and Barbu Dimitrie Ştirbei

Barbu Dimitrie Stirbei

Barbu Dimitrie Ştirbei , a member of the Bibescu boyar family, was a Prince of Wallachia on two occasions, in 1848–1853 and in 1854–1856.-Early life:...

in Wallachia, had resumed their work while the cholera epidemic was still raging, and continued it after Pahlen had been replaced with Pyotr Zheltukhin in February 1829.

Adoption and character

Treasury

A treasury is either*A government department related to finance and taxation.*A place where currency or precious items is/are kept....

, and that Zheltukhin used his position to interfere in the proceedings of the commission, nominated his own choice of members, and silenced all opposition by having anti-Russian boyars expelled from the countries (including, notably, Iancu Văcărescu

Iancu Vacarescu

Iancu Văcărescu was a Romanian Wallachian boyar and poet, member of the Văcărescu family.-Biography:The son of Alecu Văcărescu, descending from a long line of Wallachian men of letters — his paternal uncle, Ienăchiţă Văcărescu, was author of the first Romanian grammar; Iancu was the...

, a member of the Wallachian Divan who had questioned his methods of government). According to the radical

Radicalism (historical)

The term Radical was used during the late 18th century for proponents of the Radical Movement. It later became a general pejorative term for those favoring or seeking political reforms which include dramatic changes to the social order...

Ghica, "General Zheltukhin [and his subordinates] defended all Russian abuse and injustice. Their system consisted in never listening to complaints, but rather rushing in with accusations, so as to inspire fear, so as the plaintiff would run away for fear of not having to endure a harsher thing than the cause of his [original] complaint". However, the same source also indicated that this behaviour was hiding a more complex situation: "Those who nevertheless knew Zheltukhin better… said that he was the fairest, most honest, and most kind of men, and that he gave his cruel orders with an aching heart. Many gave assurance that he had addressed to the emperor heart-breaking reports on the deplorable state in which the Principalities were to be found, in which he stated that Russia's actions in the Principalities deserved the scorn of the entire world".

The third and last Russian governor, Pavel Kiselyov

Pavel Kiselyov

Count Pavel Dmitrievich Kiselyov or Kiseleff is generally regarded as the most brilliant Russian reformer during Nicholas I's generally conservative reign.- Early military career :...

(or Kiseleff), took office on October 19, 1829, and faced his first major task in dealing with the last outbreaks of plague and cholera, as well as the threat of famine

Famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including crop failure, overpopulation, or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompanied or followed by regional malnutrition, starvation, epidemic, and increased mortality. Every continent in the world has...

, with which he dealt by imposing quarantine

Quarantine

Quarantine is compulsory isolation, typically to contain the spread of something considered dangerous, often but not always disease. The word comes from the Italian quarantena, meaning forty-day period....

s and importing grain from Odessa

Odessa

Odessa or Odesa is the administrative center of the Odessa Oblast located in southern Ukraine. The city is a major seaport located on the northwest shore of the Black Sea and the fourth largest city in Ukraine with a population of 1,029,000 .The predecessor of Odessa, a small Tatar settlement,...

. His administration, lasting until April 1, 1834, was responsible for the most widespread and influential reforms of the period, and coincided with the actual enforcement of the new legislation. The of earliest Kiselyov's celebrated actions was the convening of the Wallachian Divan in November 1829, with the assurance that abuses were not to be condoned anymore.

Regulamentul Organic was adopted in its two very similar versions on July 13, 1831 (July 1, OS

Old Style and New Style dates

Old Style and New Style are used in English language historical studies either to indicate that the start of the Julian year has been adjusted to start on 1 January even though documents written at the time use a different start of year ; or to indicate that a date conforms to the Julian...

) in Wallachia and January 13, 1832 (January 1, OS) in Moldavia, after having minor changes applied to it in Saint Petersburg (where a second commission from the Principalities, presided by Mihail Sturdza

Mihail Sturdza

Mihail Sturdza was a prince of Moldavia from 1834 to 1849. A man of liberal education, he established the Mihaileana Academy, a kind of university, in Iaşi. He brought scholars from foreign countries to act as teachers, and gave a very powerful stimulus to the educational development of the...

and Alexandru Vilara, assessed it further). Its ratification

Ratification

Ratification is a principal's approval of an act of its agent where the agent lacked authority to legally bind the principal. The term applies to private contract law, international treaties, and constitutionals in federations such as the United States and Canada.- Private law :In contract law, the...

by Sultan

Ottoman Dynasty

The Ottoman Dynasty ruled the Ottoman Empire from 1299 to 1922, beginning with Osman I , though the dynasty was not proclaimed until Orhan Bey declared himself sultan...

Mahmud II

Mahmud II

Mahmud II was the 30th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839. He was born in the Topkapi Palace, Istanbul, the son of Sultan Abdulhamid I...

was not a requirement from Kiselyov's perspective, who began enforcing it as a fait accompli

Fait Accompli

Fait accompli is a French phrase which means literally "an accomplished deed". It is commonly used to describe an action which is completed before those affected by it are in a position to query or reverse it...

before this was granted. The final version of the document sanctioned the first local government abiding by the principles of separation

Separation of powers

The separation of powers, often imprecisely used interchangeably with the trias politica principle, is a model for the governance of a state. The model was first developed in ancient Greece and came into widespread use by the Roman Republic as part of the unmodified Constitution of the Roman Republic...

and balance of powers. The hospodars, elected for life (and not for the seven year-term agreed in the Convention of Akkerman) by an Extraordinary Assembly which comprised representatives

Representation (politics)

In politics, representation describes how some individuals stand in for others or a group of others, for a certain time period. Representation usually refers to representative democracies, where elected officials nominally speak for their constituents in the legislature...

of merchands and guild

Guild

A guild is an association of craftsmen in a particular trade. The earliest types of guild were formed as confraternities of workers. They were organized in a manner something between a trade union, a cartel, and a secret society...

s, stood for the executive

Executive (government)

Executive branch of Government is the part of government that has sole authority and responsibility for the daily administration of the state bureaucracy. The division of power into separate branches of government is central to the idea of the separation of powers.In many countries, the term...

, with the right to nominate ministers (whose offices were still referred to using the traditional titles of courtiers

Historical Romanian ranks and titles

This is a glossary of historical Romanian ranks and titles used in the principalities of Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania, and later in Romania. Many of these titles are of Slavic etymology, with some of Greek, Byzantine, Latin, and Turkish etymology; several are original...

) and public officials; hospodars were to be voted in office by an electoral college

Electoral college

An electoral college is a set of electors who are selected to elect a candidate to a particular office. Often these represent different organizations or entities, with each organization or entity represented by a particular number of electors or with votes weighted in a particular way...

with a confirmed majority of high-ranking boyars (in Wallachia, only 70 persons were members of the college).

Each National Assembly (approximate translation of Adunarea Obştească), inaugurated in 1831–2, was a legislature

Legislature

A legislature is a kind of deliberative assembly with the power to pass, amend, and repeal laws. The law created by a legislature is called legislation or statutory law. In addition to enacting laws, legislatures usually have exclusive authority to raise or lower taxes and adopt the budget and...

itself under the control of high-ranking boyars, comprising 35 (in Moldavia) or 42 members (in Wallachia), voted into office by no more than 3,000 electors in each state; the judiciary

Judiciary

The judiciary is the system of courts that interprets and applies the law in the name of the state. The judiciary also provides a mechanism for the resolution of disputes...

was, for the very first time, removed from the control of hospodars. In effect, the Regulament confirmed earlier steps leading to the eventual separation of church and state

Separation of church and state

The concept of the separation of church and state refers to the distance in the relationship between organized religion and the nation state....

, and, although Orthodox

Romanian Orthodox Church

The Romanian Orthodox Church is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church. It is in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox churches, and is ranked seventh in order of precedence. The Primate of the church has the title of Patriarch...

church authorities were confirmed a privileged position and a political say, the religious institution was closely supervised by the government (with the establishment of a quasi-salary expense).

A fiscal reform

Tax reform

Tax reform is the process of changing the way taxes are collected or managed by the government.Tax reformers have different goals. Some seek to reduce the level of taxation of all people by the government. Some seek to make the tax system more progressive or less progressive. Some seek to simplify...

ensued, with the creation of a poll tax

Poll tax

A poll tax is a tax of a portioned, fixed amount per individual in accordance with the census . When a corvée is commuted for cash payment, in effect it becomes a poll tax...

(calculated per family), the elimination of most indirect tax

Indirect tax

The term indirect tax has more than one meaning.In the colloquial sense, an indirect tax is a tax collected by an intermediary from the person who bears the ultimate economic burden of the tax...

es, annual state budgets (approved by the Assemblies) and the introduction of a civil list

Civil list

-United Kingdom:In the United Kingdom, the Civil List is the name given to the annual grant that covers some expenses associated with the Sovereign performing their official duties, including those for staff salaries, State Visits, public engagements, ceremonial functions and the upkeep of the...

in place of the hospodars personal treasuries. New methods of bookkeeping

Bookkeeping

Bookkeeping is the recording of financial transactions. Transactions include sales, purchases, income, receipts and payments by an individual or organization. Bookkeeping is usually performed by a bookkeeper. Bookkeeping should not be confused with accounting. The accounting process is usually...

were regulated, and the creation of national bank

National bank

In banking, the term national bank carries several meanings:* especially in developing countries, a bank owned by the state* an ordinary private bank which operates nationally...

s was projected, but, like the adoption of national fixed currencies, was never implemented.

According to the historian Nicolae Iorga

Nicolae Iorga

Nicolae Iorga was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, poet and playwright. Co-founder of the Democratic Nationalist Party , he served as a member of Parliament, President of the Deputies' Assembly and Senate, cabinet minister and briefly as Prime Minister...

, "The [boyar] oligarchy

Oligarchy

Oligarchy is a form of power structure in which power effectively rests with an elite class distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, commercial, and/or military legitimacy...

was appeased [by the Regulaments adoption]: a beautifully harmonious modern form had veiled the old medieval

Romania in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages in Romania began with the withdrawal of the Mongols, the last of the migrating populations to invade the territory of modern Romania, after their attack of 1241–1242...

structure…. The bourgeoisie

Bourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

… held no influence. As for the peasant, he lacked even the right to administer his own commune, he was not even allowed to vote for an Assembly deemed, as if in jest, «national»." Nevertheless, conservative boyars remained suspicious of Russian tutelage, and several expressed their fear that the regime was a step leading to the creation of a regional guberniya

Guberniya

A guberniya was a major administrative subdivision of the Russian Empire usually translated as government, governorate, or province. Such administrative division was preserved for sometime upon the collapse of the empire in 1917. A guberniya was ruled by a governor , a word borrowed from Latin ,...

for the Russian Empire. Their mistrust was, in time, reciprocated by Russia, who relied on hospodars and the direct intervention of its consuls to push further reforms. Kiselyov himself voiced a plan for the region's annexation

Annexation

Annexation is the de jure incorporation of some territory into another geo-political entity . Usually, it is implied that the territory and population being annexed is the smaller, more peripheral, and weaker of the two merging entities, barring physical size...

to Russia, but the request was dismissed by his superiors.

Cities and towns

Despite under-representation in politics, the middle class

Middle class

The middle class is any class of people in the middle of a societal hierarchy. In Weberian socio-economic terms, the middle class is the broad group of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the working class and upper class....

swelled in numbers, profiting from a growth in trade which had increased the status of merchants. Under continuous competition from the sudiţi

Suditi

For the commune in Ialomiţa County, see Sudiţi, Ialomiţa. For the villages in Buzău County, see Gherăseni and Poşta Câlnău.The Sudiţi were inhabitants of the Danubian Principalities who, for the latter stage of the 18th and a large part of the 19th century...

, traditional guilds (bresle or isnafuri) faded away, leading to a more competitive, purely capitalist

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

environment. This nevertheless signified that, although the traditional Greek

Greeks in Romania

There has been a Greek presence in Romania for at least 27 centuries. At times, as during the Phanariote era, this presence has amounted to hegemony; at other times , the Greeks have simply been one among the many ethnic minorities in Romania.-Ancient and Medieval Period:The Greek presence in what...

competition for Romanian

Romanians

The Romanians are an ethnic group native to Romania, who speak Romanian; they are the majority inhabitants of Romania....

merchants and artisans had become less relevant, locals continued to face one from Austrian subjects of various nationalities, as well as from a sizeable immigration of Jews

History of the Jews in Romania

The history of Jews in Romania concerns the Jews of Romania and of Romanian origins, from their first mention on what is nowadays Romanian territory....

from the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria and Russia — prevented from settling in the countryside, Jews usually became keepers of inn

INN

InterNetNews is a Usenet news server package, originally released by Rich Salz in 1991, and presented at the Summer 1992 USENIX conference in San Antonio, Texas...

s and tavern

Tavern

A tavern is a place of business where people gather to drink alcoholic beverages and be served food, and in some cases, where travelers receive lodging....

s, and later both bankers and leaseholders of estates

Leasehold estate

A leasehold estate is an ownership of a temporary right to land or property in which a lessee or a tenant holds rights of real property by some form of title from a lessor or landlord....

. In this context, an anti-Catholic

Roman Catholicism in Romania

The Roman Catholic Church in Romania is a Latin Rite Christian church, part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope and Curia in Rome. Its administration is centered in Bucharest, and comprises two archdioceses and four other dioceses...

sentiment was growing, based, according to Keith Hitchins, on the assumption that Catholicism and Austrian influence were closely related, as well as on a widespread preference for secularism

Secularism

Secularism is the principle of separation between government institutions and the persons mandated to represent the State from religious institutions and religious dignitaries...

.

Xenophobia

Xenophobia is defined as "an unreasonable fear of foreigners or strangers or of that which is foreign or strange". It comes from the Greek words ξένος , meaning "stranger," "foreigner" and φόβος , meaning "fear."...

discourse of the National Liberal Party

National Liberal Party (Romania)

The National Liberal Party , abbreviated to PNL, is a centre-right liberal party in Romania. It is the third-largest party in the Romanian Parliament, with 53 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 22 in the Senate: behind the centre-right Democratic Liberal Party and the centre-left Social...

during the latter's first decade of existence (between 1875 and World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

).

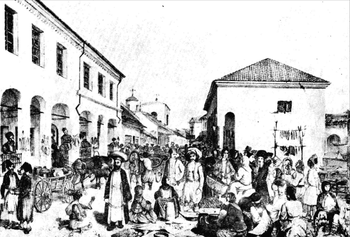

Urban development occurred at a very fast pace: overall, the urban population had doubled by 1850. Bucharest

Bucharest

Bucharest is the capital municipality, cultural, industrial, and financial centre of Romania. It is the largest city in Romania, located in the southeast of the country, at , and lies on the banks of the Dâmbovița River....

, the capital of Wallachia, expanded from about 70,000 in 1831 to about 120,000 in 1859; Iaşi

Iasi

Iași is the second most populous city and a municipality in Romania. Located in the historical Moldavia region, Iași has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Romanian social, cultural, academic and artistic life...

, the capital of Moldavia, followed at around half that number. Brăila

Braila

Brăila is a city in Muntenia, eastern Romania, a port on the Danube and the capital of Brăila County, in the close vicinity of Galaţi.According to the 2002 Romanian census there were 216,292 people living within the city of Brăila, making it the 10th most populous city in Romania.-History:A...

and Giurgiu

Giurgiu

Giurgiu is the capital city of Giurgiu County, Romania, in the Greater Wallachia. It is situated amid mud-flats and marshes on the left bank of the Danube facing the Bulgarian city of Rousse on the opposite bank. Three small islands face the city, and a larger one shelters its port, Smarda...

, Danube ports returned to Wallachia by the Ottomans, as well as Moldavia's Galaţi

Galati

Galați is a city and municipality in Romania, the capital of Galați County. Located in the historical region of Moldavia, in the close vicinity of Brăila, Galați is the largest port and sea port on the Danube River and the second largest Romanian port....

, grew from the grain trade to become prosperous cities. Kiselyov, who had centered his administration on Bucharest, paid full attention to its development, improving its infrastructure and services and awarding it, together with all other cities and towns, a local administration (see History of Bucharest

History of Bucharest

The history of Bucharest covers the time from the early settlements on the locality's territory until its modern existence as a city, capital of Wallachia, and present-day capital of Romania.-Ancient times:...

). Public works

Public works

Public works are a broad category of projects, financed and constructed by the government, for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community...

were carried out in the urban sphere, as well as in the massive expansion of the transport and communications system.

Countryside

The success of the grain trade was secured by a conservative take on property, which restricted the right of peasants to exploit for their own gain those plots of land they leased on boyar estates (the Regulament allowed them to consume around 70% of the total harvest per plot leased, while boyars were allowed to use a third of their estate as they pleased, without any legal duty toward the neighbouring peasant workforce); at the same time, small properties, created after Constantine MavrocordatosConstantine Mavrocordatos

Constantine Mavrocordatos was a Greek noble who served as Prince of Wallachia and Prince of Moldavia at several intervals...

had abolished serfdom

Serfdom

Serfdom is the status of peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to Manorialism. It was a condition of bondage or modified slavery which developed primarily during the High Middle Ages in Europe and lasted to the mid-19th century...

in the 1740s, proved less lucrative in the face of competition by large estates — boyars profited from the consequences, as more landowning peasants had to resort to leasing plots while still owing corvée

Corvée

Corvée is unfree labour, often unpaid, that is required of people of lower social standing and imposed on them by the state or a superior . The corvée was the earliest and most widespread form of taxation, which can be traced back to the beginning of civilization...

s to their lords. Confirmed by the Regulament at up to 12 days a year, the corvée was still less significant than in other parts of Europe; however, since peasants relied on cattle for alternative food supplies and financial resources, and pasture

Pasture

Pasture is land used for grazing. Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, cattle, sheep or swine. The vegetation of tended pasture, forage, consists mainly of grasses, with an interspersion of legumes and other forbs...

s remained the exclusive property of boyars, they had to exchange right of use for more days of work in the respective boyar's benefit (as much as to equate the corresponding corvée requirements in Central Europe

Central Europe

Central Europe or alternatively Middle Europe is a region of the European continent lying between the variously defined areas of Eastern and Western Europe...

an countries, without ever being enforced by laws). Several laws of the period display a particular concern in limiting the right of peasants to evade corvées by paying their equivalent in currency, thus granting the boyars a workforce to match a steady growth in grain demands on foreign markets.

In respect to pasture access, the Regulament divided peasants into three wealth-based categories: fruntaşi ("foremost people"), who, by definition, owned 4 working animal

Working animal

A working animal is an animal, usually domesticated, that is kept by humans and trained to perform tasks. They may be close members of the family, such as guide or service dogs, or they may be animals trained strictly to perform a job, such as logging elephants. They may also be used for milk, a...

s and one or more cows (allowed to use ca.4 hectare

Hectare

The hectare is a metric unit of area defined as 10,000 square metres , and primarily used in the measurement of land. In 1795, when the metric system was introduced, the are was defined as being 100 square metres and the hectare was thus 100 ares or 1/100 km2...

s of pasture); mijlocaşi ("middle people") — two working animals and one cow (ca.2 hectares); codaşi ("backward people") — people who owned no property, and not allowed the use of pastures.

At the same time, the major demographic

Demography

Demography is the statistical study of human population. It can be a very general science that can be applied to any kind of dynamic human population, that is, one that changes over time or space...

changes took their toll on the countryside. For the very first time, food supplies were no longer abundant in front of a population growth

Population growth

Population growth is the change in a population over time, and can be quantified as the change in the number of individuals of any species in a population using "per unit time" for measurement....

ensured by, among other causes, the effective measures taken against epidemics; rural-urban migration became a noticeable phenomenon, as did the relative increase in urbanization

Urbanization

Urbanization, urbanisation or urban drift is the physical growth of urban areas as a result of global change. The United Nations projected that half of the world's population would live in urban areas at the end of 2008....

of traditional rural areas, with an explosion of settlements around established fair

Fair

A fair or fayre is a gathering of people to display or trade produce or other goods, to parade or display animals and often to enjoy associated carnival or funfair entertainment. It is normally of the essence of a fair that it is temporary; some last only an afternoon while others may ten weeks. ...

s.

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

was minimal (although factories

Factory

A factory or manufacturing plant is an industrial building where laborers manufacture goods or supervise machines processing one product into another. Most modern factories have large warehouses or warehouse-like facilities that contain heavy equipment used for assembly line production...

had first been opened during the Phanariotes

Phanariotes

Phanariots, Phanariotes, or Phanariote Greeks were members of those prominent Greek families residing in Phanar , the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople, where the Ecumenical Patriarchate is situated.For all their cosmopolitanism and often Western education, the Phanariots were...

): most revenues came from a highly productive agriculture based on peasant labour, and were invested back into agricultural production. In parallel, hostility between agricultural workers and landowners mounted: after an increase in lawsuit

Lawsuit

A lawsuit or "suit in law" is a civil action brought in a court of law in which a plaintiff, a party who claims to have incurred loss as a result of a defendant's actions, demands a legal or equitable remedy. The defendant is required to respond to the plaintiff's complaint...

s involving leaseholders and the decrease in quality of corvée outputs, resistance, hardened by the examples of Tudor Vladimirescu

Tudor Vladimirescu

Tudor Vladimirescu was a Wallachian Romanian revolutionary hero, the leader of the Wallachian uprising of 1821 and of the Pandur militia. He is also known as Tudor din Vladimiri or — occasionally — as Domnul Tudor .-Background:Tudor was born in Vladimiri, Gorj County in a family of landed peasants...

and various hajduk

Hajduk

Hajduk is a term most commonly referring to outlaws, highwaymen or freedom fighters in the Balkans, Central- and Eastern Europe....

s, turned to sabotage

Sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening another entity through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. In a workplace setting, sabotage is the conscious withdrawal of efficiency generally directed at causing some change in workplace conditions. One who engages in sabotage is...

and occasional violence. A more serious incident occurred in 1831, when around 60,000 peasants protested against projected conscription

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

criteria; Russian troops dispatched to quell the revolt killed around 300 people.

Political and cultural setting

The most noted cultural development under the Regulament was Romanian Romantic nationalismRomantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism is the form of nationalism in which the state derives its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs...

, in close connection with Francophilia

Francophile

Is a person with a positive predisposition or interest toward the government, culture, history, or people of France. This could include France itself and its history, the French language, French cuisine, literature, etc...

. Institutional modernization

Modernization

In the social sciences, modernization or modernisation refers to a model of an evolutionary transition from a 'pre-modern' or 'traditional' to a 'modern' society. The teleology of modernization is described in social evolutionism theories, existing as a template that has been generally followed by...

engered a renaissance of the intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

. In turn, the concept of "nation

Nation

A nation may refer to a community of people who share a common language, culture, ethnicity, descent, and/or history. In this definition, a nation has no physical borders. However, it can also refer to people who share a common territory and government irrespective of their ethnic make-up...

" was first expanded beyond its coverage of the boyar category, and more members of the privileged displayed a concern in solving problems facing the peasantry: although rarer among the high-ranking boyars, the interest was shared by most progressive

Progressivism

Progressivism is an umbrella term for a political ideology advocating or favoring social, political, and economic reform or changes. Progressivism is often viewed by some conservatives, constitutionalists, and libertarians to be in opposition to conservative or reactionary ideologies.The...

political figures by the 1840s.

Dacia

In ancient geography, especially in Roman sources, Dacia was the land inhabited by the Dacians or Getae as they were known by the Greeks—the branch of the Thracians north of the Haemus range...

(first notable in the title of Mihail Kogălniceanu

Mihail Kogalniceanu

Mihail Kogălniceanu was a Moldavian-born Romanian liberal statesman, lawyer, historian and publicist; he became Prime Minister of Romania October 11, 1863, after the 1859 union of the Danubian Principalities under Domnitor Alexander John Cuza, and later served as Foreign Minister under Carol I. He...

's Dacia Literară

Dacia Literara

- History :Founded by Mihail Kogălniceanu and printed in Iaşi, it was short-lived—having lasted only from January to June 1840. Dacia Literară was a Romantic nationalist and liberal magazine, engendering a literary society.- External links :*...

, a short-lived Romantic literary magazine

Literary magazine

A literary magazine is a periodical devoted to literature in a broad sense. Literary magazines usually publish short stories, poetry and essays along with literary criticism, book reviews, biographical profiles of authors, interviews and letters...

published in 1840). As a trans-border notion, Dacia also indicated a growth in Pan-Romanian sentiment — the latter had first been present in several boyar requests of the late 18th century, which had called for the union of the two Danubian Principalities

Danubian Principalities

Danubian Principalities was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th century. The term was coined in the Habsburg Monarchy after the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in order to designate an area on the lower Danube with a common...

under the protection of European powers (and, in some cases, under the rule of a foreign prince). To these was added the circulation of fake documents which were supposed to reflect the text of Capitulations

Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire

Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire were contracts between the Ottoman Empire and European powers, particularly France. Turkish capitulations, or ahdnames, were generally bilateral acts whereby definite arrangements were entered into by each contracting party towards the other, not mere...

awarded by the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

to its Wallachian and Moldavian vassal

Vassal

A vassal or feudatory is a person who has entered into a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. The obligations often included military support and mutual protection, in exchange for certain privileges, usually including the grant of land held...

s in the Middle Ages

Romania in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages in Romania began with the withdrawal of the Mongols, the last of the migrating populations to invade the territory of modern Romania, after their attack of 1241–1242...

, claiming to stand out as proof of rights and privileges which had been long neglected (see also Islam in Romania

Islam in Romania

Islam in Romania is followed by only 0.3 percent of population, but has 700 years of tradition in Northern Dobruja, a region on the Black Sea coast which was part of the Ottoman Empire for almost five centuries . In present-day Romania, most adherents to Islam belong to the Tatar and Turkish ethnic...

).

Education

Education in Romania

According to the Law on Education adopted in 1995, the Romanian Educational System is regulated by the Ministry of Education and Research . Each level has its own form of organization and is subject to different legislation. Kindergarten is optional between 3 and 6 years old...

, still accessible only to the wealthy, was first removed from the domination of the Greek language

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

and Hellenism

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

upon the disestablishment of Phanariotes sometime after 1821; the attempts of Gheorghe Lazăr

Gheorghe Lazar

Gheorghe Lazăr , born and died in Avrig, Sibiu County, was a Transylvanian-born Romanian scholar, the founder of the first Romanian language school - in Bucharest, 1818.-Biography:...

(at the Saint Sava College

Saint Sava College

Saint Sava College was one of the earliest academic institutions in Wallachia, Romania. It was the predecessor to both Saint Sava National College and the University of Bucharest.-History:...

) and Gheorghe Asachi

Gheorghe Asachi

Gheorghe Asachi was a Moldavian-born Romanian prose writer, poet, painter, historian, dramatist and translator. An Enlightenment-educated polymath and polyglot, he was one of the most influential people of his generation...

to engender a transition towards Romanian-language

Romanian language

Romanian Romanian Romanian (or Daco-Romanian; obsolete spellings Rumanian, Roumanian; self-designation: română, limba română ("the Romanian language") or românește (lit. "in Romanian") is a Romance language spoken by around 24 to 28 million people, primarily in Romania and Moldova...

teaching had been only moderately successful, but Wallachia became the scene of such a movement after the start of Ion Heliade Rădulescu

Ion Heliade Radulescu

Ion Heliade Rădulescu or Ion Heliade was a Wallachian-born Romanian academic, Romantic and Classicist poet, essayist, memoirist, short story writer, newspaper editor and politician...

's teaching career and the first issue of his newspaper, Curierul Românesc. Moldavia soon followed, after Asachi began printing his highly influential magazine Albina Românească

Albina Româneasca

Albina Românească was a Romanian-language bi-weekly political and literary magazine, printed in Iaşi, Moldavia, at two intervals during the Regulamentul Organic period . The owner and editor was Gheorghe Asachi...

. The Regulament brought about the creation of new schools, which were dominated by the figures of Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

n Romanians who had taken exile after expressing their dissatifaction with Austrian

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

rule in their homeland — these teachers, who usually rejected the adoption of French cultural models in the otherwise conservative

Conservatism

Conservatism is a political and social philosophy that promotes the maintenance of traditional institutions and supports, at the most, minimal and gradual change in society. Some conservatives seek to preserve things as they are, emphasizing stability and continuity, while others oppose modernism...

society (viewing the process as an unnatural one), counted among them Ioan Maiorescu and August Treboniu Laurian

August Treboniu Laurian

August Treboniu Laurian was a Transylvanian Romanian politician, historian and linguist. He was born in the village of Fofeldea in Nocrich. He was a participant at the 1848 revolution, an organizer of the Romanian school and one of the founding members of the Romanian Academy.Laurian was a member...

.

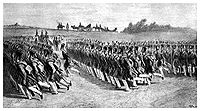

Another impetus for nationalism was the Russian-supervised creation of small standing armies

Standing army

A standing army is a professional permanent army. It is composed of full-time career soldiers and is not disbanded during times of peace. It differs from army reserves, who are activated only during wars or natural disasters...

(occasionally referred to as "militia

Militia

The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with...

s"; see Moldavian military forces

Moldavian military forces

Moldavia had a military force for much of its history as an independent and, later, autonomous principality subject to the Ottoman Empire .-Middle Ages:Under the reign of Stephen the Great, all farmers and villagers had to bear arms...

and Wallachian military forces). The Wallachian one first maneuvered in the autumn of 1831, and was supervised by Kiselyov himself. According to Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica

Ion Ghica was a Romanian revolutionary, mathematician, diplomat and twice Prime Minister of Romania . He was a full member of the Romanian Academy and its president for four times...

, the prestige of military careers had a relevant tradition: "Only the arrival of the Muscovites [sic] in 1828 ended [the] young boyars' sons flighty way of life, as it made use of them as commissioners (mehmendari) in the service of Russian generals, in order to assist in providing the troops with [supplies]. In 1831 most of them took to the sword, signing up for the national militia."

Westernization

Westernization or Westernisation , also occidentalization or occidentalisation , is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in such matters as industry, technology, law, politics, economics, lifestyle, diet, language, alphabet,...

of Romanian society took place at a rapid pace, and created a noticeable, albeit not omnipresent, generation gap

Generation gap

The generational gap is and was a term popularized in Western countries during the 1960s referring to differences between people of a younger generation and their elders, especially between children and parents....

. The paramount cultural model was the French one, following a pattern already established by contacts between the region and the French Consulate

French Consulate

The Consulate was the government of France between the fall of the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799 until the start of the Napoleonic Empire in 1804...

and First Empire

First French Empire

The First French Empire , also known as the Greater French Empire or Napoleonic Empire, was the empire of Napoleon I of France...

(attested, among others, by the existence of a Wallachian plan to petition

Petition

A petition is a request to do something, most commonly addressed to a government official or public entity. Petitions to a deity are a form of prayer....

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon I of France

Napoleon Bonaparte was a French military and political leader during the latter stages of the French Revolution.As Napoleon I, he was Emperor of the French from 1804 to 1815...

, whom locals believed to be a descendant of the Byzantine Emperors, with a complaint against the Phanariotes, as well as by an actual anonymous petition sent in 1807 from Moldavia). This trend was consolidated by the French cultural model partly adopted by the Russians, a growing mutual sympathy between the Principalities and France, increasingly obvious under the French July Monarchy

July Monarchy

The July Monarchy , officially the Kingdom of France , was a period of liberal constitutional monarchy in France under King Louis-Philippe starting with the July Revolution of 1830 and ending with the Revolution of 1848...

, and, as early as the 1820s, the enrolment of young boyars in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

ian educational institutions (coupled with the 1830 opening of a French-language school in Bucharest, headed by Jean Alexandre Vaillant

Jean Alexandre Vaillant

Jean Alexandre Vaillant was a French and Romanian teacher, political activist, historian, linguist and translator, who was noted for his activities in Wallachia and his support for the 1848 Wallachian Revolution...

). The young generation eventually attempted to curb French borrowings, which it had come to see as endangering its nationalist aspirations.

Statutory rules and nationalist opposition

.jpg)

Hospodar

Hospodar or gospodar is a term of Slavonic origin, meaning "lord" or "master".The rulers of Wallachia and Moldavia were styled hospodars in Slavic writings from the 15th century to 1866. Hospodar was used in addition to the title voivod...

s (instead of providing for their election), as a means to ensure both the monarchs' support for a moderate pace in reforms and their allegiance in front of conservative boyar opposition. The choices were Alexandru II Ghica

Alexandru II Ghica

Alexandru II or Alexandru D. Ghica , a member of the Ghica family, was Prince of Wallachia from April 1834 to 7 October 1842 and later caimacam from July 1856 to October 1858....

(the stepbrother of the previous monarch, Grigore IV

Grigore IV Ghica

Grigore IV Ghica or Grigore Dimitrie Ghica was Prince of Wallachia between 1822 and 1828. A member of the Ghica family, Grigore IV was the brother of Alexandru Ghica and the uncle of Dora d'Istria....

) as Prince of Wallachia and Mihail Sturdza

Mihail Sturdza

Mihail Sturdza was a prince of Moldavia from 1834 to 1849. A man of liberal education, he established the Mihaileana Academy, a kind of university, in Iaşi. He brought scholars from foreign countries to act as teachers, and gave a very powerful stimulus to the educational development of the...

(a distant cousin of Ioniţă Sandu

Ioan Sturdza

Ioan Sturdza was a Prince of Moldavia and the most famous descendant of Alexandru Sturdza...

) as Prince of Moldavia. The two rules (generally referred to as Domnii regulamentare — "statutory" or "regulated reigns"), closely observed by the Russian consuls

Consul (representative)

The political title Consul is used for the official representatives of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, and to facilitate trade and friendship between the peoples of the two countries...

and various Russian technical advisors, soon met a vocal and unified opposition in the Assemblies and elsewhere.

Immediately after the confirmation of the Regulament, Russia had begun demanding that the two local Assemblies each vote an Additional Article (Articol adiţional) — one preventing any modification of the texts without the common approval of the courts in Istanbul and Saint Petersburg. In Wallachia, the issue turned into scandal after the pressure for adoption mounted in 1834, and led to a four-year long standstill, during which a nationalist group in the legislative body began working on its own project for a constitution, proclaiming the Russian protectorate

Protectorate

In history, the term protectorate has two different meanings. In its earliest inception, which has been adopted by modern international law, it is an autonomous territory that is protected diplomatically or militarily against third parties by a stronger state or entity...