Science in the Age of Enlightenment

Encyclopedia

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

traces developments in science

Science

Science is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe...

and technology

Technology

Technology is the making, usage, and knowledge of tools, machines, techniques, crafts, systems or methods of organization in order to solve a problem or perform a specific function. It can also refer to the collection of such tools, machinery, and procedures. The word technology comes ;...

during the Age of Reason

Age of reason

Age of reason may refer to:* 17th-century philosophy, as a successor of the Renaissance and a predecessor to the Age of Enlightenment* Age of Enlightenment in its long form of 1600-1800* The Age of Reason, a book by Thomas Paine...

, when Enlightenment ideas and ideals were being disseminated across Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

and North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

. Generally, the period spans from the final days of the 16th and 17th-century Scientific revolution

Scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution is an era associated primarily with the 16th and 17th centuries during which new ideas and knowledge in physics, astronomy, biology, medicine and chemistry transformed medieval and ancient views of nature and laid the foundations for modern science...

until roughly the 19th century, after the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

(1789) and the Napoleonic era

Napoleonic Era

The Napoleonic Era is a period in the history of France and Europe. It is generally classified as including the fourth and final stage of the French Revolution, the first being the National Assembly, the second being the Legislative Assembly, and the third being the Directory...

(1799–1815). The scientific revolution saw the creation of the first scientific societies

Learned society

A learned society is an organization that exists to promote an academic discipline/profession, as well a group of disciplines. Membership may be open to all, may require possession of some qualification, or may be an honor conferred by election, as is the case with the oldest learned societies,...

, the rise of Copernicanism

Heliocentrism

Heliocentrism, or heliocentricism, is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around a stationary Sun at the center of the universe. The word comes from the Greek . Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at the center...

, and the displacement of Aristotelian natural philosophy

Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism is a tradition of philosophy that takes its defining inspiration from the work of Aristotle. The works of Aristotle were initially defended by the members of the Peripatetic school, and, later on, by the Neoplatonists, who produced many commentaries on Aristotle's writings...

and Galen’s

Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus , better known as Galen of Pergamon , was a prominent Roman physician, surgeon and philosopher...

ancient medical doctrine. By the 18th century, scientific authority began to displace religious authority, and the disciplines of alchemy

Alchemy

Alchemy is an influential philosophical tradition whose early practitioners’ claims to profound powers were known from antiquity. The defining objectives of alchemy are varied; these include the creation of the fabled philosopher's stone possessing powers including the capability of turning base...

and astrology

Astrology

Astrology consists of a number of belief systems which hold that there is a relationship between astronomical phenomena and events in the human world...

lost scientific credibility.

While the Enlightenment cannot be pigeonholed into a specific doctrine or set of dogmas, science came to play a leading role in Enlightenment discourse and thought. Many Enlightenment writers and thinkers had backgrounds in the sciences and associated scientific advancement with the overthrow of religion and traditional authority in favour of the development of free speech and thought. Broadly speaking, Enlightenment science greatly valued empiricism

Empiricism

Empiricism is a theory of knowledge that asserts that knowledge comes only or primarily via sensory experience. One of several views of epistemology, the study of human knowledge, along with rationalism, idealism and historicism, empiricism emphasizes the role of experience and evidence,...

and rational thought, and was embedded with the Enlightenment ideal of advancement and progress. As with most Enlightenment views, the benefits of science were not seen universally; Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer of 18th-century Romanticism. His political philosophy influenced the French Revolution as well as the overall development of modern political, sociological and educational thought.His novel Émile: or, On Education is a treatise...

criticized the sciences for distancing man from nature and not operating to make people happier.

Science during the Enlightenment was dominated by scientific societies and academies

Academy

An academy is an institution of higher learning, research, or honorary membership.The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 385 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the goddess of wisdom and skill, north of Athens, Greece. In the western world academia is the...

, which had largely replaced universities as centres of scientific research and development. Societies and academies were also the backbone of the maturation of the scientific profession. Another important development was the popularization

Popular culture

Popular culture is the totality of ideas, perspectives, attitudes, memes, images and other phenomena that are deemed preferred per an informal consensus within the mainstream of a given culture, especially Western culture of the early to mid 20th century and the emerging global mainstream of the...

of science among an increasingly literate population. Philosophe

Philosophe

The philosophes were the intellectuals of the 18th century Enlightenment. Few were primarily philosophers; rather they were public intellectuals who applied reason to the study of many areas of learning, including philosophy, history, science, politics, economics and social issues...

s introduced the public to many scientific theories, most notably through the Encyclopédie

Encyclopédie

Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It was edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert...

and the popularization of Newtonianism

Newtonianism

Newtonianism is a doctrine that involves following the principles and using the methods of natural philosopher Isaac Newton. While Newton's influential contributions were primarily in physics and mathematics, his broad conception of the universe as being governed by rational and understandable laws...

by Voltaire

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet , better known by the pen name Voltaire , was a French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion, free trade and separation of church and state...

as well as by Emilie du Chatelet, the French translator of Newton's Principia. Some historians have marked the 18th century as a drab period in the history of science

History of science

The history of science is the study of the historical development of human understandings of the natural world and the domains of the social sciences....

; however, the century saw significant advancements in the practice of medicine

Medicine

Medicine is the science and art of healing. It encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness....

, mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

, and physics

Physics

Physics is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic...

; the development of biological taxonomy

Taxonomy

Taxonomy is the science of identifying and naming species, and arranging them into a classification. The field of taxonomy, sometimes referred to as "biological taxonomy", revolves around the description and use of taxonomic units, known as taxa...

; a new understanding of magnetism

Magnetism

Magnetism is a property of materials that respond at an atomic or subatomic level to an applied magnetic field. Ferromagnetism is the strongest and most familiar type of magnetism. It is responsible for the behavior of permanent magnets, which produce their own persistent magnetic fields, as well...

and electricity

Electricity

Electricity is a general term encompassing a variety of phenomena resulting from the presence and flow of electric charge. These include many easily recognizable phenomena, such as lightning, static electricity, and the flow of electrical current in an electrical wire...

; and the maturation of chemistry

Chemistry

Chemistry is the science of matter, especially its chemical reactions, but also its composition, structure and properties. Chemistry is concerned with atoms and their interactions with other atoms, and particularly with the properties of chemical bonds....

as a discipline, which established the foundations of modern chemistry.

Universities

YALE

RapidMiner, formerly YALE , is an environment for machine learning, data mining, text mining, predictive analytics, and business analytics. It is used for research, education, training, rapid prototyping, application development, and industrial applications...

. The number of university students remained roughly the same throughout the Enlightenment in most Western nations, excluding Britain, where the number of institutions and students increased. University students were generally males from affluent families, seeking a career in either medicine, law, or the Church. The universities themselves existed primarily to educate future physician

Physician

A physician is a health care provider who practices the profession of medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, injury and other physical and mental impairments...

s, lawyer

Lawyer

A lawyer, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "a person learned in the law; as an attorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law." Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political...

s and members of the clergy

Clergy

Clergy is the generic term used to describe the formal religious leadership within a given religion. A clergyman, churchman or cleric is a member of the clergy, especially one who is a priest, preacher, pastor, or other religious professional....

.

The study of science under the heading of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or the philosophy of nature , is a term applied to the study of nature and the physical universe that was dominant before the development of modern science...

was divided into physics and a conglomerate grouping of chemistry and natural history

Natural history

Natural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

, which included anatomy

Anatomy

Anatomy is a branch of biology and medicine that is the consideration of the structure of living things. It is a general term that includes human anatomy, animal anatomy , and plant anatomy...

, biology, geology

Geology

Geology is the science comprising the study of solid Earth, the rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which it evolves. Geology gives insight into the history of the Earth, as it provides the primary evidence for plate tectonics, the evolutionary history of life, and past climates...

, mineralogy

Mineralogy

Mineralogy is the study of chemistry, crystal structure, and physical properties of minerals. Specific studies within mineralogy include the processes of mineral origin and formation, classification of minerals, their geographical distribution, as well as their utilization.-History:Early writing...

, and zoology

Zoology

Zoology |zoölogy]]), is the branch of biology that relates to the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinct...

. Most European universities taught a Cartesian

René Descartes

René Descartes ; was a French philosopher and writer who spent most of his adult life in the Dutch Republic. He has been dubbed the 'Father of Modern Philosophy', and much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings, which are studied closely to this day...

form of mechanical philosophy in the early 18th century, and only slowly adopted Newtonianism in the mid-18th century. A notable exception were universities in Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

, which under the influence of Catholicism

Catholicism

Catholicism is a broad term for the body of the Catholic faith, its theologies and doctrines, its liturgical, ethical, spiritual, and behavioral characteristics, as well as a religious people as a whole....

focused almost entirely on Aristotelian natural philosophy until the mid-18th century; they were among the last universities to do so. Another exception occurred in the universities of Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

and Scandinavia

Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a cultural, historical and ethno-linguistic region in northern Europe that includes the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, characterized by their common ethno-cultural heritage and language. Modern Norway and Sweden proper are situated on the Scandinavian Peninsula,...

, where University of Halle professor Christian Wolff

Christian Wolff (philosopher)

Christian Wolff was a German philosopher.He was the most eminent German philosopher between Leibniz and Kant...

taught a form of Cartesianism modified by Leibnizian physics.

Lecture

thumb|A lecture on [[linear algebra]] at the [[Helsinki University of Technology]]A lecture is an oral presentation intended to present information or teach people about a particular subject, for example by a university or college teacher. Lectures are used to convey critical information, history,...

s. The structure of courses began to change in the first decades of the 18th century, when physical demonstrations

Scientific demonstration

A scientific demonstration is a scientific experiment carried out for the purposes of demonstrating scientific principles, rather than for hypothesis testing or knowledge gathering ....

were added to lectures. Pierre Polinière

Pierre Polinière

Pierre Polinière was an early investigator of electricity and electrical phenomena, notably "barometric light", a form of gas-discharge light, which suggested the possibility of electric lighting...

and Jacques Rohault

Jacques Rohault

Jacques Rohault was a French philosopher, physicist and mathematician, and a follower of Cartesianism.Rohault was born in Amiens, the son of a wealthy wine merchant, and educated in Paris. Having grown up with the conventional scholastic philosophy of his day, he adopted and popularised the new...

were among the first individuals to provide demonstrations of physical principles in the classroom. Experiments ranged from swinging a bucket of water at the end of a rope, demonstrating that centrifugal force

Centrifugal force

Centrifugal force can generally be any force directed outward relative to some origin. More particularly, in classical mechanics, the centrifugal force is an outward force which arises when describing the motion of objects in a rotating reference frame...

would hold the water in the bucket, to more impressive experiments involving the use of an air-pump

Vacuum pump

A vacuum pump is a device that removes gas molecules from a sealed volume in order to leave behind a partial vacuum. The first vacuum pump was invented in 1650 by Otto von Guericke.- Types :Pumps can be broadly categorized according to three techniques:...

. One particularly dramatic air-pump demonstration involved placing an apple inside the glass receiver of the air-pump, and removing air until the resulting vacuum caused the apple to explode. Polinière’s demonstrations were so impressive that he was granted an invitation to present his course to Louis XV in 1722.

Some attempts at reforming the structure of the science curriculum were made during the 18th-century and the first decades of the 19th century. Beginning around 1745, the Hats party

Hats (party)

The Hats were a Swedish political faction active during the Age of Liberty . Their name derives from the tricorne hat worn by officers and gentlemen. They vied for power with the Caps. The Hats, who ruled Sweden from 1738 to 1765, advocated an alliance with France and an assertive foreign policy,...

in Sweden made propositions to reform the university system by separating natural philosophy into two separate faculties of physics and mathematics. The propositions were never put into action, but they represent the growing calls for institutional reform in the later part of the 18th century. In 1777, the study of arts at Cracow and Vilna in Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

was divided into the two new faculties of moral philosophy and physics. However, the reform did not survive beyond 1795 and the Third Partition

Third Partition of Poland

The Third Partition of Poland or Third Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth took place in 1795 as the third and last of three partitions that ended the existence of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.-Background:...

. During the French Revolution, all colleges and universities in France were abolished and reformed in 1808 under the single institution of the Université imperiale. The Université divided the arts and sciences into separate faculties, something that had never before been done before in Europe. The state of Belgium-Holland

United Kingdom of the Netherlands

United Kingdom of the Netherlands is the unofficial name used to refer to Kingdom of the Netherlands during the period after it was first created from part of the First French Empire and before the new kingdom of Belgium split out in 1830...

employed the same system in 1815. However, the other countries of Europe did not adopt a similar division of the faculties until the mid-19th century.

French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research...

. The contributions of universities in Britain were mixed. On the one hand, the University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

began teaching Newtonianism early in the Enlightenment, but failed to become a central force behind the advancement of science. On the other end of the spectrum were Scottish universities, which had strong medical faculties and became centres of scientific development. Under Frederick II

Frederick II of Prussia

Frederick II was a King in Prussia and a King of Prussia from the Hohenzollern dynasty. In his role as a prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire, he was also Elector of Brandenburg. He was in personal union the sovereign prince of the Principality of Neuchâtel...

, German universities began to promote the sciences. Christian Wolff

Christian Wolff (philosopher)

Christian Wolff was a German philosopher.He was the most eminent German philosopher between Leibniz and Kant...

's unique blend of Cartesian-Leibnizian physics began to be adopted in universities outside of Halle. The University of Göttingen, founded in 1734, was far more liberal than its counterparts, allowing professors to plan their own courses and select their own textbooks. Göttingen also emphasized research and publication. A further influential development in German universities was the abandonment of Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

in favour of the German vernacular

Vernacular

A vernacular is the native language or native dialect of a specific population, as opposed to a language of wider communication that is not native to the population, such as a national language or lingua franca.- Etymology :The term is not a recent one...

.

In the 17th century, the Netherlands

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

had played a significant role in the advancement of the sciences, including Isaac Beeckman’s

Isaac Beeckman

Isaac Beeckman was a Dutch philosopher and scientist, who, through his studies and contact with leading natural philosophers, may have "virtually given birth to modern atomism".-Biography:...

mechanical philosophy and Christiaan Huygens’ work on the calculus and in astronomy

Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that deals with the study of celestial objects and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth...

. Professors at universities in the Dutch Republic

Dutch Republic

The Dutch Republic — officially known as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands , the Republic of the United Netherlands, or the Republic of the Seven United Provinces — was a republic in Europe existing from 1581 to 1795, preceding the Batavian Republic and ultimately...

were among the first to adopt Newtonianism. From the University of Leiden, Willem 's Gravesande

Willem 's Gravesande

Willem Jacob 's Gravesande was a Dutch philosopher and mathematician.-Life:Born in 's-Hertogenbosch, he studied law in Leiden and wrote a thesis on suicide. He was praised by John Bernoulli when he published his book Essai de perspective. In 1715, he visited London and King George I. He became a...

’s students went on to spread Newtonianism to Harderwijk

Harderwijk

' is a municipality and a small city in the eastern Netherlands.- The history of Harderwijk :Harderwijk received city rights from Count Otto II of Guelders in 1231. A defensive wall surrounding the city was completed by the end of that century. The oldest part of the city is near where the...

and Franeker

Franeker

Franeker is one of the eleven historical cities of Friesland and capital of the municipality of Franekeradeel. It is located about 20 km west of Leeuwarden on the Van Harinxma Canal. As of 1 January 2006, it had 12,996 inhabitants. The city is famous for the Eisinga Planetarium from around...

, among other Dutch universities, and also to the University of Amsterdam.

While the number of universities did not dramatically increase during the Enlightenment, new private and public institutions added to the provision of education. Most of the new institutions emphasized mathematics as a discipline, making them popular with professions that required some working knowledge of mathematics, such as merchants, military and naval officers, and engineers. Universities, on the other hand, maintained their emphasis on the classics, Greek, and Latin, encouraging the popularity of the new institutions with individuals who had not been formally educated.

Societies and Academies

Scientific academies and societies grew out of the Scientific Revolution as the creators of scientific knowledge in contrast to the scholasticism of the university. During the Enlightenment, some societies created or retained links to universities. However, contemporary sources distinguished universities from scientific societies by claiming that the university’s utility was in the transmission of knowledge, while societies functioned to create knowledge. As the role of universities in institutionalized science began to diminish, learned societies became the cornerstone of organized science. After 1700 a tremendous number of official academies and societies were founded in Europe and by 1789 there were over seventy official scientific societies . In reference to this growth, Bernard de Fontenelle coined the term “the Age of Academies” to describe the 18th century.National scientific societies were founded throughout the Enlightenment era in the urban hotbeds of scientific development across Europe. In the 17th century the Royal Society of London (1662), the Paris Académie Royale des Sciences (1666), and the Berlin Akademie der Wissenschaften (1700) were founded. At the turn of the century, the Academia Scientiarum Imperialis (1724) in St. Petersburg, and the Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien (Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences) (1739) were created. Regional and provincial societies emerged out of the 18th century in Bologna

Bologna

Bologna is the capital city of Emilia-Romagna, in the Po Valley of Northern Italy. The city lies between the Po River and the Apennine Mountains, more specifically, between the Reno River and the Savena River. Bologna is a lively and cosmopolitan Italian college city, with spectacular history,...

, Bordeaux

Bordeaux

Bordeaux is a port city on the Garonne River in the Gironde department in southwestern France.The Bordeaux-Arcachon-Libourne metropolitan area, has a population of 1,010,000 and constitutes the sixth-largest urban area in France. It is the capital of the Aquitaine region, as well as the prefecture...

, Copenhagen

Copenhagen

Copenhagen is the capital and largest city of Denmark, with an urban population of 1,199,224 and a metropolitan population of 1,930,260 . With the completion of the transnational Øresund Bridge in 2000, Copenhagen has become the centre of the increasingly integrating Øresund Region...

, Dijon

Dijon

Dijon is a city in eastern France, the capital of the Côte-d'Or département and of the Burgundy region.Dijon is the historical capital of the region of Burgundy. Population : 151,576 within the city limits; 250,516 for the greater Dijon area....

, Lyon

Lyon

Lyon , is a city in east-central France in the Rhône-Alpes region, situated between Paris and Marseille. Lyon is located at from Paris, from Marseille, from Geneva, from Turin, and from Barcelona. The residents of the city are called Lyonnais....

s, Montpellier

Montpellier

-Neighbourhoods:Since 2001, Montpellier has been divided into seven official neighbourhoods, themselves divided into sub-neighbourhoods. Each of them possesses a neighbourhood council....

and Uppsala

Uppsala

- Economy :Today Uppsala is well established in medical research and recognized for its leading position in biotechnology.*Abbott Medical Optics *GE Healthcare*Pfizer *Phadia, an offshoot of Pharmacia*Fresenius*Q-Med...

. Following this initial period of growth, societies were founded between 1752 and 1785 in Barcelona

Barcelona

Barcelona is the second largest city in Spain after Madrid, and the capital of Catalonia, with a population of 1,621,537 within its administrative limits on a land area of...

, Brussels

Brussels

Brussels , officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region , is the capital of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union...

, Dublin, Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

, Göttingen, Mannheim

Mannheim

Mannheim is a city in southwestern Germany. With about 315,000 inhabitants, Mannheim is the second-largest city in the Bundesland of Baden-Württemberg, following the capital city of Stuttgart....

, Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

, Padua

Padua

Padua is a city and comune in the Veneto, northern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Padua and the economic and communications hub of the area. Padua's population is 212,500 . The city is sometimes included, with Venice and Treviso, in the Padua-Treviso-Venice Metropolitan Area, having...

and Turin

Turin

Turin is a city and major business and cultural centre in northern Italy, capital of the Piedmont region, located mainly on the left bank of the Po River and surrounded by the Alpine arch. The population of the city proper is 909,193 while the population of the urban area is estimated by Eurostat...

. The development of unchartered societies, such as the private the Naturforschende Gesellschaft of Danzig (1743) and Lunar Society

Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 in Birmingham, England. At first called the Lunar Circle,...

of Birmingham (1766–1791), occurred alongside the growth of national, regional and provincial societies.

.jpg)

Scientific journal

In academic publishing, a scientific journal is a periodical publication intended to further the progress of science, usually by reporting new research. There are thousands of scientific journals in publication, and many more have been published at various points in the past...

s. Periodicals offered society members the opportunity to publish, and for their ideas to be consumed by other scientific societies and the literate public. Scientific journals, readily accessible to members of learned societies, became the most important form of publication for scientists during the Enlightenment.

Periodicals

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society of London. It was established in 1665, making it the first journal in the world exclusively devoted to science, and it has remained in continuous publication ever since, making it the world's...

, published by the Royal Society of London, was the only scientific periodical being published on a regular, quarterly basis. The Paris Academy of Sciences, formed in 1666, began publishing in volumes of memoirs rather than a quarterly journal, with periods between volumes sometimes lasting years. While some official periodicals may have published more frequently, there was still a long delay from a paper’s submission for review to its actual publication. Smaller periodicals, such as Transactions of the American Philosophical Society

American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society, founded in 1743, and located in Philadelphia, Pa., is an eminent scholarly organization of international reputation, that promotes useful knowledge in the sciences and humanities through excellence in scholarly research, professional meetings, publications,...

, were only published when enough content was available to complete a volume. At the Paris Academy, there was an average delay of three years for publication. At one point the period extended to seven years. The Paris Academy processed submitted articles through the Comité de Librarie, which had the final word on what would or would not be published. In 1703, the mathematician Antoine Parent

Antoine Parent

Antoine Parent was a French mathematician, born at Paris and died there, who wrote in 1700 on analytical geometry of three dimensions. His works were collected and published in three volumes at Paris in 1713....

began a periodical, Researches in Physics and Mathematics, specifically to publish papers that had been rejected by the Comité.

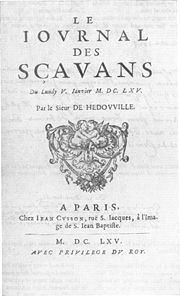

Journal des sçavans

The Journal des sçavans , founded by Denis de Sallo, was the earliest academic journal published in Europe, that from the beginning also carried a proportion of material that would not now be considered scientific, such as obituaries of famous men, church history, and legal reports...

(1665–1792), the Jesuit Mémoires de Trévoux (1701–1779), and Leibniz’s Acta Eruditorum

Acta Eruditorum

Acta Eruditorum was the first scientific journal of the German lands, published from 1682 to 1782....

(Reports/Acts of the Scholars) (1682–1782). Independent periodicals were published throughout the Enlightenment and excited scientific interest in the general public. While the journals of the academies primarily published scientific papers, independent periodicals were a mix of reviews, abstracts, translations of foreign texts, and sometimes derivative, reprinted materials. Most of these texts were published in the local vernacular, so their continental spread depended on the language of the readers. For example, in 1761 Russian scientist Mikhail Lomonosov

Mikhail Lomonosov

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov was a Russian polymath, scientist and writer, who made important contributions to literature, education, and science. Among his discoveries was the atmosphere of Venus. His spheres of science were natural science, chemistry, physics, mineralogy, history, art,...

correctly attributed the ring of light around Venus

Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun, orbiting it every 224.7 Earth days. The planet is named after Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty. After the Moon, it is the brightest natural object in the night sky, reaching an apparent magnitude of −4.6, bright enough to cast shadows...

, visible during the planet’s transit

Transit of Venus

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and Earth, becoming visible against the solar disk. During a transit, Venus can be seen from Earth as a small black disk moving across the face of the Sun...

, as the planet's atmosphere

Atmosphere

An atmosphere is a layer of gases that may surround a material body of sufficient mass, and that is held in place by the gravity of the body. An atmosphere may be retained for a longer duration, if the gravity is high and the atmosphere's temperature is low...

; however, because few scientists understood Russian outside of Russia, his discovery was not widely credited until 1910.

Some changes in periodicals occurred during the course of the Enlightenment. First, they increased in number and size. There was also a move away from publishing in Latin in favour of publishing in the vernacular. Experimental descriptions became more detailed and began to be accompanied by reviews. In the late 18th century, a second change occurred when a new breed of periodical began to publish monthly about new developments and experiments in the scientific community. The first of this kind of journal was François Rozier's Observations sur la physiques, sur l’histoire naturelle et sur les arts, commonly referred to as "Rozier’s journal", which was first published in 1772. The journal allowed new scientific developments to be published relatively quickly compared to annuals and quarterlies. A third important change was the specialization seen in the new development of disciplinary journals. With a wider audience and ever increasing publication material, specialized journals such as Curtis’ Botanical Magazine (1787) and the Annals de Chimie (1789) reflect the growing division between scientific disciplines in the Enlightenment era.

Popularization of science

One of the most important developments that the Enlightenment era brought to the discipline of science was its popularization. An increasingly literate population seeking knowledge and education in both the arts and the sciences drove the expansion of print culture and the dissemination of scientific learning. The new literate population was due to a high rise in the availability of food. This enabled many people to rise out of poverty, and instead of paying more for food, they had money for education. Popularization was generally part of an overarching Enlightenment ideal that endeavoured “to make information available to the greatest number of people.” As public interest in natural philosophy grew during the 18th century, public lecture courses and the publication of popular texts opened up new roads to money and fame for amateurs and scientists who remained on the periphery of universities and academies.British coffeehouses

An early example of science emanating from the official institutions into the public realm was the British coffeehouseCoffeehouse

A coffeehouse or coffee shop is an establishment which primarily serves prepared coffee or other hot beverages. It shares some of the characteristics of a bar, and some of the characteristics of a restaurant, but it is different from a cafeteria. As the name suggests, coffeehouses focus on...

. With the establishment of coffeehouses, a new public forum for political, philosophical and scientific discourse was created. In the mid-16th century, coffeehouses cropped up around Oxford

Oxford

The city of Oxford is the county town of Oxfordshire, England. The city, made prominent by its medieval university, has a population of just under 165,000, with 153,900 living within the district boundary. It lies about 50 miles north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames run through...

, where the academic community began to capitalize on the unregulated conversation that the coffeehouse allowed. The new social space began to be used by some scholars as a place to discuss science and experiments outside of the laboratory of the official institution. Coffeehouse patrons were only required to purchase a dish of coffee to participate, leaving the opportunity for many, regardless of financial means, to benefit from the conversation. Education was a central theme and some patrons began offering lessons and lectures to others. The chemist Peter Staehl provided chemistry lessons at Tilliard’s coffeehouse in the early 1660s. As coffeehouses developed in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, customers heard lectures on scientific subjects, such as astronomy and mathematics, for an exceedingly low price. Notable Coffeehouse enthusiasts included John Aubrey

John Aubrey

John Aubrey FRS, was an English antiquary, natural philosopher and writer. He is perhaps best known as the author of the collection of short biographical pieces usually referred to as Brief Lives...

, Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS was an English natural philosopher, architect and polymath.His adult life comprised three distinct periods: as a scientific inquirer lacking money; achieving great wealth and standing through his reputation for hard work and scrupulous honesty following the great fire of 1666, but...

, James Brydges, and Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys FRS, MP, JP, was an English naval administrator and Member of Parliament who is now most famous for the diary he kept for a decade while still a relatively young man...

.

Public lectures

Public lecture courses offered some scientists who were unaffiliated with official organizations a forum to transmit scientific knowledge, at times even their own ideas, and the opportunity to carve out a reputation and, in some instances, a living. The public, on the other hand, gained both knowledge and entertainment from demonstration lectures. Between 1735 and 1793, there were over seventy individuals offering courses and demonstrations for public viewers in experimental physics. Class sizes ranged from one hundred to four or five hundred attendees. Courses varied in duration from one to four weeks, to a few months, or even the entire academic year. Courses were offered at virtually any time of day; the latest occurred at 8:00 or 9:00 at night. One of the most popular start times was 6:00 pm, allowing the working population to participate and signifying the attendance of the nonelite. Barred from the universities and other institutions, women were often in attendance at demonstration lectures and constituted a significant number of auditors.The importance of the lectures was not in teaching complex mathematics or physics, but rather in demonstrating to the wider public the principles of physics and encouraging discussion and debate. Generally, individuals presenting the lectures did not adhere to any particular brand of physics, but rather demonstrated a combination of different theories. New advancements in the study of electricity offered viewers demonstrations that drew far more inspiration among the laity than scientific papers could hold. An example of a popular demonstration used by Jean-Antoine Nollet

Jean-Antoine Nollet

Jean-Antoine Nollet was a French clergyman and physicist. As a priest, he was also known as Abbé Nollet. He was particularly interested in the new science of electricity, which he explored with the help of Du Fay and Réaumur...

and other lecturers was the ‘electrified boy’. In the demonstration, a young boy would be suspended from the ceiling, horizontal to the floor, with silk chords. An electrical machine would then be used to electrify the boy. Essentially becoming a magnet, he would then attract a collection of items scattered about him by the lecturer. Sometimes a young girl would be called from the auditors to touch or kiss the boy on the cheek, causing sparks to shoot between the two children in what was dubbed the ‘electric kiss‘. Such marvels would certainly have entertained the audience, but the demonstration of physical principles also served an educational purpose. One 18th-century lecturer insisted on the utility of his demonstrations, stating that they were “useful for the good of society.”

Popular science in print

Increasing literacy rates in Europe during the course of the Enlightenment enabled science to enter popular culture through print. More formal works included explanations of scientific theories for individuals lacking the educational background to comprehend the original scientific text. Sir Isaac Newton’sIsaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

celebrated Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica

Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica

Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, Latin for "Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy", often referred to as simply the Principia, is a work in three books by Sir Isaac Newton, first published 5 July 1687. Newton also published two further editions, in 1713 and 1726...

was published in Latin and remained inaccessible to readers without education in the classics until Enlightenment writers began to translate and analyze the text in the vernacular. The first French introduction to Newtonianism and the Principia was Eléments de la philosophie de Newton, published by Voltaire in 1738. Émilie du Châtelet

Émilie du Châtelet

-Early life:Du Châtelet was born on 17 December 1706 in Paris, the only daughter of six children. Three brothers lived to adulthood: René-Alexandre , Charles-Auguste , and Elisabeth-Théodore . Her eldest brother, René-Alexandre, died in 1720, and the next brother, Charles-Auguste, died in 1731...

's translation of the Principia, published after her death in 1756, also helped to spread Newton’s theories beyond scientific academies and the university.

Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds

Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds is a popular science book by French author Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, published in 1686. It offered an explanation of the heliocentric model of the Universe, suggested by Nicolaus Copernicus in his 1543 work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium...

(1686) marked the first significant work that expressed scientific theory and knowledge expressly for the laity, in the vernacular, and with the entertainment of readers in mind. The book was produced specifically for women with an interest in scientific writing and inspired a variety of similar works. These popular works were written in a discursive style, which was laid out much more clearly for the reader than the complicated articles, treatises, and books published by the academies and scientists. Charles Leadbetter’s Astronomy (1727) was advertised as “a Work entirely New” that would include “short and easie [sic] Rules and Astronomical Tables.” Francesco Algarotti

Francesco Algarotti

Count Francesco Algarotti was an Italian philosopher and art critic.He also completed engravings.He was born in Venice to a rich merchant. He studied at Rome for a year, and then Bologna, he studied natural sciences and mathematics...

, writing for a growing female audience, published Il Newtonianism per le dame, which was a tremendously popular work and was translated from Italian into English by Elizabeth Carter

Elizabeth Carter

Elizabeth Carter was an English poet, classicist, writer and translator, and a member of the Bluestocking Circle.-Biography:...

. A similar introduction to Newtonianism for women was produced by Henry Pembarton. His A View of Sir Isaac Newton’s Philosophy was published by subscription. Extant records of subscribers show that women from a wide range of social standings purchased the book, indicating the growing number of scientifically inclined female readers among the middling class. During the Enlightenment, women also began producing popular scientific works themselves. Sarah Trimmer

Sarah Trimmer

Sarah Trimmer was a noted writer and critic of British children's literature in the eighteenth century...

wrote a successful natural history textbook for children entitled The Easy Introduction to the Knowledge of Nature (1782), which was published for many years after in eleven editions.

The influence of science also began appearing more commonly in poetry and literature during the Enlightenment. Some poetry became infused with scientific metaphor and imagery, while other poems were written directly about scientific topics. Sir Richard Blackmore committed the Newtonian system to verse in Creation, a Philosophical Poem in Seven Books (1712). After Newton’s death in 1727, poems were composed in his honour for decades. James Thomson (1700–1748) penned his “Poem to the Memory of Newton,” which mourned the loss of Newton, but also praised his science and legacy:

Thy swift career is with whirling orbs,

Comparing things with things in rapture loft,

And grateful adoration, for that light,

So plenteous ray'd into thy mind below.

While references to the sciences were often positive, there were some Enlightenment writers who criticized scientists for what they viewed as their obsessive, frivolous careers. Other antiscience writers, including William Blake

William Blake

William Blake was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of both the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age...

, chastised scientists for attempting to use physics, mechanics and mathematics to simplify the complexities of the universe, particularly in relation to God. The character of the evil scientist was invoked during this period in the romantic tradition. For example, the characterization of the scientist as a nefarious manipulator in the work of Ernst Theodor Wilhelm Hoffmann.

Women in science

Forceps

Forceps or forcipes are a handheld, hinged instrument used for grasping and holding objects. Forceps are used when fingers are too large to grasp small objects or when many objects need to be held at one time while the hands are used to perform a task. The term 'forceps' is used almost exclusively...

. That particular restriction exemplified the increasingly constrictive, male-dominated medical community. Over the course of the 18th century, male surgeons began to assume the role of midwives in gynaecology. Some male satirists also ridiculed scientifically minded women, describing them as neglectful of their domestic role. The negative view of women in the sciences reflected the sentiment apparent in some Enlightenment texts that women need not, nor ought to be educated; the opinion is exemplified by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in Émile:

Laura Bassi

Laura Maria Caterina Bassi was an Italian scientist, the first woman to officially teach at a university in Europe.-Biography:Born in Bologna into a wealthy family with a lawyer as a father, she was privately educated and tutored for seven years in her teens by Gaetano Tacconi...

and the Russian Princess Yekaterina Dashkova

Yekaterina Romanovna Vorontsova-Dashkova

Princess Yekaterina Romanovna Vorontsova-Dashkova was the closest female friend of Empress Catherine the Great and a major figure of the Russian Enlightenment...

. Bassi was an Italian physicist who received a PhD from the University of Bologna and began teaching there in 1732. Dashkova became the director of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences of St. Petersburg in 1783. Her personal relationship with Czarina Catherine the Great (r. 1762-1796) allowed her to obtain the position, which marked in history the first appointment of a woman to the directorship of a scientific academy.

More commonly, women participated in the sciences through an association with a male relative or spouse. Caroline Herschel

Caroline Herschel

Caroline Lucretia Herschel was a German-British astronomer, the sister of astronomer Sir Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel with whom she worked throughout both of their careers. Her most significant contribution to astronomy was the discovery of several comets and in particular the periodic comet...

began her astronomical career, although somewhat reluctantly at first, by assisting her brother William Herschel

William Herschel

Sir Frederick William Herschel, KH, FRS, German: Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel was a German-born British astronomer, technical expert, and composer. Born in Hanover, Wilhelm first followed his father into the Military Band of Hanover, but emigrated to Britain at age 19...

. Caroline Herschel is most remembered for her discovery of eight comets and her Index to Flamsteed’s Observations of the Fixed Stars (1798). On August 1, 1786, Herschel discovered her first comet, much to the excitement of scientifically minded women. Fanny Burney

Fanny Burney

Frances Burney , also known as Fanny Burney and, after her marriage, as Madame d’Arblay, was an English novelist, diarist and playwright. She was born in Lynn Regis, now King’s Lynn, England, on 13 June 1752, to musical historian Dr Charles Burney and Mrs Esther Sleepe Burney...

commented on the discovery, stating that “the comet was very small, and had nothing grand or striking in its appearance; but it is the first lady’s comet, and I was very desirous to see it.” Marie-Anne Pierette Paulze worked collaboratively with her husband, Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier , the "father of modern chemistry", was a French nobleman prominent in the histories of chemistry and biology...

. Aside from assisting in Lavoisier’s laboratory research, she was responsible for translating a number of English texts into French for her husband’s work on the new chemistry. Paulze also illustrated many of her husband’s publications, such as his Treatise on Chemistry (1789). Eva Ekeblad

Eva Ekeblad

Eva Ekeblad , née Eva De la Gardie, was a Swedish agronomist, scientist, Salonist and noble . Her most known discovery was to make flour and alcohol out of potatoes...

became the first woman inducted in to the Royal Swedish Academy of Science (1748).

Many other women became illustrators or translators of scientific texts. In France, Madeleine Françoise Basseporte

Françoise Basseporte

Madeleine Françoise Basseporte, was a French painter.She became one of the pupils of Claude Aubriet thanks to her precocious talent for design. She replaced him as the Royal Painter after his death...

was employed by the Royal Botanical Garden as an illustrator. Englishwoman Mary Delany

Mary Delany

Mary Delany was an English Bluestocking, artist, and letter-writer; equally famous for her "paper-mosaicks" and her lively correspondence.-Early life:...

developed a unique method of illustration. Her technique involved using hundreds of pieces of coloured-paper to recreate lifelike renditions of living plants. Noblewomen sometimes cultivated their own botanical gardens, including Mary Somerset and Margaret Harley. Scientific translation sometimes required more than a grasp on multiple languages. Besides translating Newton’s Principia into French, Émilie du Châtelet expanded Newton’s work to include recent progress made in mathematical physics after his death.

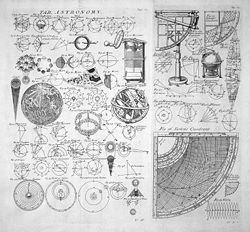

Astronomy

Building on the body of work forwarded by Copernicus, Kepler and NewtonIsaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

, 18th-century astronomers refined telescopes, produced star catalogue

Star catalogue

A star catalogue, or star catalog, is an astronomical catalogue that lists stars. In astronomy, many stars are referred to simply by catalogue numbers. There are a great many different star catalogues which have been produced for different purposes over the years, and this article covers only some...

s, and worked towards explaining the motions of heavenly bodies and the consequences of universal gravitation. Among the prominent astronomers of the age was Edmund Halley. In 1705 Halley correctly linked historical descriptions of particularly bright comets to the reappearance of just one, which would later be named Halley’s Comet, based on his computation of the orbits of comets. Halley also changed the theory of the Newtonian universe, which described the fixed stars. When he compared the ancient positions of stars to their contemporary positions, he found that they had shifted. James Bradley

James Bradley

James Bradley FRS was an English astronomer and served as Astronomer Royal from 1742, succeeding Edmund Halley. He is best known for two fundamental discoveries in astronomy, the aberration of light , and the nutation of the Earth's axis...

, while attempting to document stellar parallax

Stellar parallax

Stellar parallax is the effect of parallax on distant stars in astronomy. It is parallax on an interstellar scale, and it can be used to determine the distance of Earth to another star directly with accurate astrometry...

, realized that the unexplained motion of stars he had early observed with Samuel Molyneux

Samuel Molyneux

Samuel Molyneux FRS , son of William Molyneux, was an 18th-century member of the British parliament from Kew and an amateur astronomer whose work with James Bradley attempting to measure stellar parallax led to the discovery of the aberration of light...

was caused by the aberration of light

Aberration of light

The aberration of light is an astronomical phenomenon which produces an apparent motion of celestial objects about their real locations...

. The discovery was proof of a heliocentric model of the universe, since it is the revolution of the earth around the sun that causes an apparent motion in the observed position of a star. The discovery also led Bradley to a fairly close estimate to the speed of light.

Transit of Venus

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and Earth, becoming visible against the solar disk. During a transit, Venus can be seen from Earth as a small black disk moving across the face of the Sun...

, the Russian scientist Mikhail Lomonosov

Mikhail Lomonosov

Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov was a Russian polymath, scientist and writer, who made important contributions to literature, education, and science. Among his discoveries was the atmosphere of Venus. His spheres of science were natural science, chemistry, physics, mineralogy, history, art,...

observed a ring of light around the planet. Lomonosov attributed the ring to the refraction of sunlight, which he correctly hypothesized was caused by the atmosphere of Venus. Further evidence of Venus' atmosphere was gathered in observations by Johann Hieronymus Schröter in 1779. The planet also offered Alexis Claude de Clairaut an opportunity to work his considerable mathematical skills when he computed the mass of Venus through complex mathematical calculations.

However, much astronomical work of the period becomes shadowed by one of the most dramatic scientific discoveries of the 18th-century. On 13 March 1781, amateur astronomer William Herschel

William Herschel

Sir Frederick William Herschel, KH, FRS, German: Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel was a German-born British astronomer, technical expert, and composer. Born in Hanover, Wilhelm first followed his father into the Military Band of Hanover, but emigrated to Britain at age 19...

spotted a new planet with his powerful reflecting telescope

Reflecting telescope

A reflecting telescope is an optical telescope which uses a single or combination of curved mirrors that reflect light and form an image. The reflecting telescope was invented in the 17th century as an alternative to the refracting telescope which, at that time, was a design that suffered from...

. Initially identified as a comet, the celestial body later came to be accepted as a planet. Soon after, the planet was named Georgium Sidus by Herschel and was called Herschelium in France. The name Uranus

Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. It has the third-largest planetary radius and fourth-largest planetary mass in the Solar System. It is named after the ancient Greek deity of the sky Uranus , the father of Cronus and grandfather of Zeus...

, as proposed by Johann Bode, came into widespread usage after Herschel's death. On the theoretical side of astronomy, the English natural philosopher John Michell

John Michell

John Michell was an English natural philosopher and geologist whose work spanned a wide range of subjects from astronomy to geology, optics, and gravitation. He was both a theorist and an experimenter....

first proposed the existence of dark stars in 1783. Michell postulated that if the density of a stellar object became great enough, its attractive force would become so large that even light could not escape. He also surmised that the location of a dark star could be determined by the strong gravitational force it would exert on surrounding stars. While differing somewhat from a black hole

Black hole

A black hole is a region of spacetime from which nothing, not even light, can escape. The theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass will deform spacetime to form a black hole. Around a black hole there is a mathematically defined surface called an event horizon that...

, the dark star can be understood as a predecessor to the black holes resulting from Albert Einstein's

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

theory of general relativity.

Chemistry

The chemical revolutionChemical Revolution

The chemical revolution, also called the first chemical revolution, denotes the reformulation of chemistry based on the Law of Conservation of Matter and the oxygen theory of combustion. It was centered on the work of French chemist Antoine Lavoisier...

was a period in the 18th century marked by significant advancements in the theory and practice of chemistry. Despite the maturity of most of the sciences during the scientific revolution, by the mid-18th century chemistry had yet to outline a systematic framework or theoretical doctrine. Elements of alchemy still permeated the study of chemistry, and the belief that the natural world was composed of the classical elements of earth, water, air and fire remained prevalent. The key achievement of the chemical revolution has traditionally been viewed as the abandonment of phlogiston theory

Phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory , first stated in 1667 by Johann Joachim Becher, is an obsolete scientific theory that postulated the existence of a fire-like element called "phlogiston", which was contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion...

in favour of Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier , the "father of modern chemistry", was a French nobleman prominent in the histories of chemistry and biology...

's oxygen theory of combustion

Combustion

Combustion or burning is the sequence of exothermic chemical reactions between a fuel and an oxidant accompanied by the production of heat and conversion of chemical species. The release of heat can result in the production of light in the form of either glowing or a flame...

; however, more recent studies attribute a wider range of factors as contributing forces behind the chemical revolution.

Developed under Johann Joachim Becher and Georg Ernst Stahl

Georg Ernst Stahl

Georg Ernst Stahl was a German chemist and physician.He was born at Ansbach. Having graduated in medicine at the University of Jena in 1683, he became court physician to Duke Johann Ernst of Sachsen Weimar in 1687...

, phlogiston theory was an attempt to account for products of combustion. According to the theory, a substance called phlogiston was released from inflammable materials through burning. The resulting product was termed calx, which was considered a 'dephlogisticated' substance in its 'true' form. The first strong evidence against phlogiston theory came from pneumatic chemists in Britain during the later half of the 18th century. Joseph Black

Joseph Black

Joseph Black FRSE FRCPE FPSG was a Scottish physician and chemist, known for his discoveries of latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide. He was professor of Medicine at University of Glasgow . James Watt, who was appointed as philosophical instrument maker at the same university...

, Joseph Priestly and Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish FRS was a British scientist noted for his discovery of hydrogen or what he called "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable air, which formed water on combustion, in a 1766 paper "On Factitious Airs". Antoine Lavoisier later reproduced Cavendish's experiment and...

all identified different gases that composed air; however, it was not until Antoine Lavoisier discovered in the fall of 1772 that, when burned, sulphur and phosphorus

Phosphorus

Phosphorus is the chemical element that has the symbol P and atomic number 15. A multivalent nonmetal of the nitrogen group, phosphorus as a mineral is almost always present in its maximally oxidized state, as inorganic phosphate rocks...

“gain[ed] in weight” that the phlogiston theory began to unravel.

Lavoisier subsequently discovered and named oxygen

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

, described its role in animal respiration

Respiration (physiology)

'In physiology, respiration is defined as the transport of oxygen from the outside air to the cells within tissues, and the transport of carbon dioxide in the opposite direction...

and the calcination

Calcination

Calcination is a thermal treatment process applied to ores and other solid materials to bring about a thermal decomposition, phase transition, or removal of a volatile fraction. The calcination process normally takes place at temperatures below the melting point of the product materials...

of metals exposed to air (1774–1778). In 1783, Lavoisier found that water was a compound of oxygen and hydrogen

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with atomic number 1. It is represented by the symbol H. With an average atomic weight of , hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant chemical element, constituting roughly 75% of the Universe's chemical elemental mass. Stars in the main sequence are mainly...

. Lavoisier’s years of experimentation formed a body of work that contested phlogiston theory. After reading his “Reflections on Phlogiston” to the Academy in 1785, chemists began dividing into camps based on the old phlogiston theory and the new oxygen theory. A new form of chemical nomenclature, developed by Louis Bernard Guyton de Morveua, with assistance from Lavoisier, classified elements binomially into a genus

Genus

In biology, a genus is a low-level taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms, which is an example of definition by genus and differentia...

and a species

Species

In biology, a species is one of the basic units of biological classification and a taxonomic rank. A species is often defined as a group of organisms capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring. While in many cases this definition is adequate, more precise or differing measures are...

. For example, burned lead was of the genus oxide

Oxide

An oxide is a chemical compound that contains at least one oxygen atom in its chemical formula. Metal oxides typically contain an anion of oxygen in the oxidation state of −2....

and species lead

Lead

Lead is a main-group element in the carbon group with the symbol Pb and atomic number 82. Lead is a soft, malleable poor metal. It is also counted as one of the heavy metals. Metallic lead has a bluish-white color after being freshly cut, but it soon tarnishes to a dull grayish color when exposed...

. Transition to and acceptance of Lavoisier’s new chemistry varied in pace across Europe. The new chemistry was established in Glasgow and Edinburgh early in the 1790s, but was slow to become established in Germany. Eventually the oxygen-based theory of combustion drowned out the phlogiston theory and in the process created the basis of modern chemistry.

See also

- History of ScienceHistory of scienceThe history of science is the study of the historical development of human understandings of the natural world and the domains of the social sciences....

- Age of EnlightenmentAge of EnlightenmentThe Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

- Natural philosophyNatural philosophyNatural philosophy or the philosophy of nature , is a term applied to the study of nature and the physical universe that was dominant before the development of modern science...

- Scientific methodScientific methodScientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of...

- RationalismRationalismIn epistemology and in its modern sense, rationalism is "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification" . In more technical terms, it is a method or a theory "in which the criterion of the truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive"...

- Chemical RevolutionChemical RevolutionThe chemical revolution, also called the first chemical revolution, denotes the reformulation of chemistry based on the Law of Conservation of Matter and the oxygen theory of combustion. It was centered on the work of French chemist Antoine Lavoisier...