Aftermath of World War II

Encyclopedia

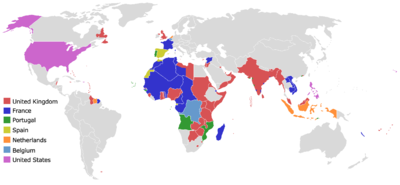

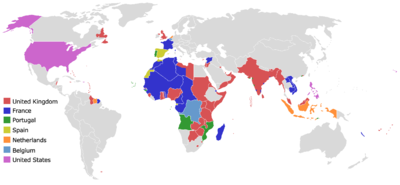

After World War II a new era of tensions emerged based on opposing ideologies, mutual distrust between nations, and a nuclear arms race

. This emerged into an environment dominated by a international balance of power

that had changed significantly from the status quo before the war. A number of boundary disputes emerged in countries affected by the war, and the dwindling of power of the imperial nations such as Britain and France resulted in an increase in the demand for national self-determination

in European colonial territories.

The immediate post-war period in Europe was dominated by the Soviet Union

annexing, or converting into Soviet Socialist Republics, all the countries captured by the Red Army

driving the German invaders out of central and eastern Europe. New Soviet satellite states rose in Poland

, Bulgaria, Hungary

, Czechoslovakia

, Romania, Albania, and East Germany; the last of these was created from the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany. Yugoslavia emerged as an independent Communist state, allied but not aligned with the Soviet Union, owing to the independent nature of the military victory of the Partisans of Josip Broz Tito

in the Yugoslav Front.

The Allies established the Far Eastern Commission

and Allied Council For Japan

to administer their occupation of that country. They demilitarised the nation, dismantled its arms industry, and installed a democratic government with a new constitution.

A similar body, the Allied Control Council

, administered occupied Germany. In accordance with the Potsdam Conference

agreements promising territorial concessions to the Soviet Union in the Far East in return for entering the war against Japan, the Soviet Union occupied and subsequently annexed the strategic island of Sakhalin

.

At the end of the war, millions of people were homeless, the European economy had collapsed, and much of the European industrial infrastructure had been destroyed. The Soviet Union

At the end of the war, millions of people were homeless, the European economy had collapsed, and much of the European industrial infrastructure had been destroyed. The Soviet Union

, too, had been heavily affected. In response, in 1947, U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall

devised the "European Recovery Program", which became known as the Marshall Plan

. Under the plan, during 1948-1952 the United States government allocated US$13 billion (US$ billion in dollars) for the reconstruction of Western Europe

.

was exhausted. More than a quarter of its national wealth had been spent. Until the introduction of Lend-Lease the UK had been spending its assets to purchase American equipment including aircraft and ships - over £437 million on aircraft alone. Lend-lease came just before its reserved were exhausted. Britain put 55% of its total labour force into in war production.

In Spring 1945, the Labour Party

withdrew from the wartime coalition government, forcing a general election

. Following a landslide victory, Labour held more than 60% of the seats in the House of Commons and formed a new government on 26 July 1945 under Clement Attlee

.

Britain's war debt was described by some in the American administration as a "millstone round the neck of the British economy". Although there were suggestions for an international conference to tackle the issue, in August 1945 the U.S. announced unexpectedly that the Lend-Lease programme was to end immediately.

The abrupt withdrawal of American Lend Lease support to Britain on 2 September 1945 dealt a severe blow to the plans of the new government. It was only with the completion of the Anglo-American loan

by the United States to Great Britain on 15 July 1946 that some measure of economic stability was restored. However, the loan was made primarily to support British overseas expenditure in the immediate post-war years and not to implement the Labour government's policies for domestic welfare reforms and the nationalisation of key industries.

Although the loan was agreed on reasonable terms its conditions included what proved to be damaging fiscal conditions for Sterling. From 1946-1948 the UK had to introduce bread rationing which it had never had to do during the war.

The Soviet Union suffered enormous losses in the war against Germany. The Soviet population decreased by about 40 million during the war; of these, 8.7 million were combat deaths. The 19 million non-combat deaths had a variety of causes: starvation in the siege of Leningrad

The Soviet Union suffered enormous losses in the war against Germany. The Soviet population decreased by about 40 million during the war; of these, 8.7 million were combat deaths. The 19 million non-combat deaths had a variety of causes: starvation in the siege of Leningrad

; conditions in German prisons and concentration camps; mass shootings of civilians; harsh labour in German industry; famine and disease; conditions in Soviet camps; and service in German or German-controlled military units fighting the Soviet Union. The population would not return to its pre-war level for 30 years.

Soviet ex-POWs and civilians repatriated from abroad were suspected of having been Nazi collaborators, and 226,127 of them were sent to forced labour camps after scrutiny by Soviet intelligence, NKVD

. Many ex-POWs and young civilians were also conscripted to serve in the Red Army. Others worked in labour battalions to rebuild infrastructure destroyed during the war.

The economy had been devastated. Roughly a quarter of the Soviet Union's capital resources were destroyed, and industrial and agricultural output in 1945 fell far short of pre-war levels. To help rebuild the country, the Soviet government obtained limited credits from Britain and Sweden; it refused assistance offered by the United States under the Marshall Plan. Instead, the Soviet Union compelled Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe to supply machinery and raw materials. Germany and former Nazi satellites made reparations to the Soviet Union. The reconstruction programme emphasised heavy industry to the detriment of agriculture and consumer goods. By 1953, steel production was twice its 1940 level, but the production of many consumer goods and foodstuffs was lower than it had been in the late 1920s.

In the west, Alsace-Lorraine

In the west, Alsace-Lorraine

was returned to France. The Sudetenland

reverted back to Czechoslovakia following the European Advisory Commission

's decision to delimit German territory to be the territory it held on December 31, 1937. Close to one quarter of pre-war (1937) Germany was de facto annexed by the Allies; roughly 10 million Germans were either expelled from this territory or not permitted to return to it if they had fled during the war. The remainder of Germany was partitioned into four zones of occupation, coordinated by the Allied Control Council

. The Saar

was detached and put in economic union with France in 1947. In 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany

was created out of the Western zones. The Soviet zone became the German Democratic Republic

.

Germany paid reparations

to the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union, mainly in the form of dismantled factories

, forced labour

, and coal. German standard of living

was to be reduced to its 1932 level. Beginning immediately after the German surrender and continuing for the next two years, the U.S. and Britain pursued an "intellectual reparations" programme to harvest all technological and scientific know-how as well as all patents in Germany. The value of these amounted to around US$10 billion (US$ billion in dollars). In accordance with the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947

, reparations were also assessed from the countries of Italy

, Romania

, Hungary

, Bulgaria

, and Finland

.

U.S. policy in post-war Germany from April 1945 until July 1947 had been that no help should be given to the Germans in rebuilding their nation, save for the minimum required to mitigate starvation. The Allies' immediate post-war "industrial disarmament" plan for Germany had been to destroy Germany's capability to wage war by complete or partial de-industrialization. The first industrial plan for Germany, signed in 1946, required the destruction of 1,500 manufacturing plants to lower German heavy industry output to roughly 50% of its 1938 level. Dismantling of West German industry ended in 1951. By 1950, equipment had been removed from 706 manufacturing plants, and steel production capacity had been reduced by 6.7 million tons. After lobbying by the Joint Chiefs of Staff

U.S. policy in post-war Germany from April 1945 until July 1947 had been that no help should be given to the Germans in rebuilding their nation, save for the minimum required to mitigate starvation. The Allies' immediate post-war "industrial disarmament" plan for Germany had been to destroy Germany's capability to wage war by complete or partial de-industrialization. The first industrial plan for Germany, signed in 1946, required the destruction of 1,500 manufacturing plants to lower German heavy industry output to roughly 50% of its 1938 level. Dismantling of West German industry ended in 1951. By 1950, equipment had been removed from 706 manufacturing plants, and steel production capacity had been reduced by 6.7 million tons. After lobbying by the Joint Chiefs of Staff

and Generals Lucius D. Clay

and George Marshall

, the Truman administration

accepted that economic recovery in Europe could not go forward without the reconstruction of the German industrial base on which it had previously had been dependent. In July 1947, President Truman rescinded on "national security grounds" the directive that had ordered the U.S. occupation forces to "take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany." A new directive recognised that "[a]n orderly, prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany." From mid-1946 onwards Germany received U.S. government aid through the GARIOA

programme. From 1948 onwards West Germany also became a minor beneficiary of the Marshall Plan. Volunteer organisations had initially been forbidden to send food, but in early 1946 the Council of Relief Agencies Licensed to Operate in Germany was founded. The prohibition against sending CARE Package

s to individuals in Germany was rescinded on 5 June 1946.

After the German surrender, the International Red Cross was prohibited from providing aid such as food or visiting POW camps for Germans inside Germany. However, after making approaches to the Allies in the autumn of 1945 it was allowed to investigate the camps in the UK and French occupation zones of Germany, as well as to provide relief to the prisoners held there. On February 4, 1946, the Red Cross was permitted to visit and assist prisoners also in the U.S. occupation zone of Germany, although only with very small quantities of food. The Red Cross petitioned successfully for improvements to be made in the living conditions of German POWs.

, and Korea

became independent. At the Yalta Conference

, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt

had secretly traded the Japanese Kurils and south Sakhalin to the Soviet Union in return for Soviet entry in the war with Japan. In response, the Soviet Union annexed the Kuril Islands

, provoking the Kuril Islands dispute

, which was ongoing as of 2011.

Hundreds of thousands of Japanese were forced to relocate to the Japanese main islands. Okinawa became a main U.S. staging point. The U.S. covered large areas of it with military bases and continued to occupy it until 1972, years after the end of the occupation of the main islands. The bases still remain. To skirt the Geneva Convention, the Allies classified many Japanese soldiers as Japanese Surrendered Personnel

instead of POWs and used them as forced labour until 1947. The UK, France, and the Netherlands conscripted some Japanese troops to fight colonial resistances elsewhere in Asia. General Douglas MacArthur

established the International Military Tribunal for the Far East

. The Allies collected reparations from Japan.

To further remove Japan as a potential future military threat, the Far Eastern Commission

decided to de-industrialise Japan, with the goal of reducing Japanese standard of living to what prevailed between 1930 and 1934. In the end, the de-industrialisation program in Japan was implemented to a lesser degree than the one in Germany. Japan received emergency aid from GARIOA, as did Germany. In early 1946, the Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia

were formed and permitted to supply Japanese with food and clothes. In April 1948 the Johnston Committee Report recommended that the economy of Japan should be reconstructed due to the high cost to U.S. taxpayers of continuous emergency aid.

Survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

, known as hibakusha

(被爆者), were ostracized by Japanese society. Japan provided no special assistance to these people until 1952. By the 65th anniversary of the bombings, total casualties from the initial attack and later deaths reached about 270,000 in Hiroshima and 150,000 in Nagasaki. About 230,000 hibakusha were still alive as of 2010, and about 2,200 were suffering from radiation-caused illnesses as of 2007.

of 1939, the Soviet Union invaded neutral Finland

and annexed some of its territory. The Finnish attempt to recover this territory in the Continuation War

of 1941-44 failed. Finland retained its independence following the war but remained subject to Soviet-imposed constraints in its domestic affairs.

, Estonia

, Latvia

, and Lithuania

. In June 1941, the Soviet governments of the Baltic states carried out mass deportations

of "enemies of the people"; as a result, many treated the invading Nazis as liberators when they invaded only a week later.

The Atlantic Charter

promised self-determination to peoples deprived of it during the war. The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill

, argued for a weaker interpretation of the Charter to permit the Soviet Union to continue to control the Baltic states. In March 1944 the U.S. accepted Churchill's view that the Atlantic Charter did not apply to the Baltic states.

With the return of Soviet troops at the end of the war, the Forest Brothers

mounted a guerrilla war. This continued until the mid-1950s.

As a result of the new borders drawn by the victorious nations, large populations suddenly found themselves in hostile territory. The Soviet Union took over areas formerly controlled by Germany, Finland, Poland, and Japan. Poland received most of Germany east

As a result of the new borders drawn by the victorious nations, large populations suddenly found themselves in hostile territory. The Soviet Union took over areas formerly controlled by Germany, Finland, Poland, and Japan. Poland received most of Germany east

of the Oder-Neisse line

, including the industrial regions of Silesia

. The German state of the Saar was temporarily a protectorate of France but later returned to German administration.

The number expelled from Germany, as set forth at Potsdam, totalled roughly 12 million, including seven million from Germany proper and three million from the Sudetenland

. Mainstream estimates of casualties from the expulsions range between 500,000 and two million dead.

The Soviet Union expelled two million Poles from east of the new border approximating the Curzon Line

. This border change reversed the results of the 1919-1920 Polish-Soviet War

. Former Polish cities such as L'vov

came under control of the of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Additionally, the Soviet Union transferred more than two million people within their own borders; these included Germans, Finns, Crimean Tatars

, and Chechens.

During the war, the United States government interned approximately 110,000 Japanese American

s and Japanese

who lived along the Pacific coast of the United States in the wake of Imperial Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor

. Canada interned approximately 22,000 Japanese Canadians, 14,000 of whom were born in Canada. After the war, some internees chose to return to Japan, while most remained in North America.

, Hungary

, Czechoslovakia

and Yugoslavia. The population of Bulgaria was largely spared this treatment, due possibly to a sense of ethnic kinship or to the leadership of Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin

. The population of Germany was treated significantly worse. Rape and murder of German civilians was as bad as, and sometimes worse than, Nazi propaganda had anticipated. Political officers encouraged Soviet troops to seek revenge and terrorise the German population. Estimates of the numbers of rapes committed by Soviet soldiers range from tens of thousands to two million. About one-third of all German women in Berlin were raped by Soviet forces. A substantial minority were raped multiple times. In Berlin, contemporary hospital records indicate between 95,000 and 130,000 women were raped by Soviet troops. About 10,000 of these women died, mostly by suicide. Over 4.5 million Germans fled towards the West. The Soviets initially had no rules against their troops fraternising with German women, but by 1947 they started to isolate their troops from the German population in an attempt to stop rape and robbery by the troops. Not all Soviet soldiers participated in these activities.

Foreign reports of Soviet brutality were denounced as false. Rape, robbery, and murder were blamed on German bandits impersonating Soviet soldiers. Some justified Soviet brutality towards German civilians based on previous brutality of German troops toward Russian civilians. Until the reunification of Germany, East German histories virtually ignored the actions of Soviet troops, and Russian histories still tend to do so. Reports of mass rapes by Soviet troops were often dismissed as anti-Communist propaganda or the normal byproduct of war.

Rapes also occurred under other occupation forces, though the majority were committed by Soviet troops. French Moroccan troops matched the behavior of Soviet troops when it came to rape, especially in the early occupations of Baden

and Württemberg

. In a letter to the editor of TIME

published in September 1945, an American army sergeant

wrote, "Our own Army and the British Army along with ours have done their share of looting and raping ... This offensive attitude among our troops is not at all general, but the percentage is large enough to have given our Army a pretty black name, and we too are considered an army of rapists." Robert Lilly’s analysis of military records led him to conclude about 14,000 rapes occurred in Britain, France and Germany at the hands of U.S. soldiers between 1942 to 1945. Lilly assumed that only 5% of rapes by American soldiers were reported, making 17,000 GI rapes a possibility, while analysts estimate that 50% of (ordinary peace-time) rapes are reported. Supporting Lilly's lower figure is the "crucial difference" that for World War II military rapes "it was the commanding officer, not the victim, who brought charges".

German soldiers left many war children

behind in nations such as France and Denmark, which were occupied for an extended period. After the war, the children and their mothers often suffered recriminations. In Norway, the “Tyskerunger“ (German-kids) suffered greatly.

The alliance between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union began to deteriorate even before the war was over, when Stalin

The alliance between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union began to deteriorate even before the war was over, when Stalin

, Roosevelt, and Churchill exchanged a heated correspondence over whether the Polish Government in Exile, backed by Roosevelt and Churchill, or the Provisional Government, backed by Stalin, should be recognised. Stalin won.

A number of allied leaders felt that war between the United States and the Soviet Union was likely. On May 19, 1945, American Under-Secretary of State Joseph Grew

went so far as to say that it was inevitable.

On March 5, 1946, in his "Sinews of Peace" (Iron Curtain) speech at Westminster College

in Fulton, Missouri

, Winston Churchill said "a shadow" had fallen over Europe. He described Stalin as having dropped an "Iron Curtain

" between East and West. Stalin responded by charging that co-existence between Communist and capitalist systems was impossible. In mid-1948 the Soviet Union imposed a blockade on the Western zone of occupation in Berlin

.

Due to the rising tension in Europe and concerns over further Soviet expansion, American planners came up with a contingency plan code-named Operation Dropshot

in 1949. It considered possible nuclear and conventional war with the Soviet Union and its allies in order to counter a Soviet takeover of Western Europe, the Near East and parts of Eastern Asia that they anticipated would begin around 1957. In response, the U.S. would saturate the Soviet Union with atomic and high-explosive bombs, and then invade and occupy the country. In later years, to reduce military expenditures while countering Soviet conventional strength, President Dwight Eisenhower would adopt a strategy of massive retaliation

, relying on the threat of a U.S. nuclear strike to prevent non-nuclear incursions by the Soviet Union in Europe and elsewhere. The approach entailed a major buildup of U.S. nuclear forces and a corresponding reduction in America's non-nuclear ground and naval strength. The Soviet Union viewed these developments as "atomic blackmail".

In Greece

, civil war broke out

in 1947 between Anglo-American-supported royalist forces and communist-led forces

, with the royalist forces emerging as the victors. The U.S. launched a massive programme of military and economic aid to Greece and to neighbouring Turkey

, arising from a fear that the Soviet Union stood on the verge of breaking through the NATO defence line to the oil-rich Middle East

. On March 12, 1947, to gain Congressional

support for the aid, U.S. President Harry Truman described the aid as promoting democracy

in defence of the "free world

", a principle that became known as the Truman Doctrine

.

The U.S. sought to promote an economically strong and politically united Western Europe to counter the threat posed by the Soviet Union. This was done openly using tools such as the European Recovery Program, which encouraged European economic integration. The International Authority for the Ruhr

, designed to keep German industry down and controlled, evolved into the European Coal and Steel Community

, a founding pillar of the European Union

. The United States also worked covertly to promote European integration, for example using the American Committee on United Europe

to funnel funds to European federalist movements. In order to ensure that Western Europe could withstand the Soviet military threat, the Western European Union

was founded in 1948 and NATO in 1949. The first NATO Secretary General, Lord Ismay, famously stated the organisation's goal was "to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down". However, without the manpower and industrial output of West Germany

no conventional defence of Western Europe had any hope of succeeding. To remedy this, in 1950 the U.S. sought to promote the European Defence Community

, which would have included a rearmed West Germany. The attempt was dashed when the French Parliament rejected it. On May 9, 1955, West Germany was instead admitted to NATO; the immediate result was the creation of the Warsaw Pact

five days later.

The Cold War

also saw the creation of propaganda and espionage organisations such as Radio Free Europe

, the Information Research Department

, the Gehlen Organization

, the Central Intelligence Agency

, the Special Activities Division

, and the Ministry for State Security.

In Asia, the surrender of Japanese forces was complicated by the split between East and West as well as by the movement toward national self-determination in European colonial territories.

the Allies agreed that an undivided post-war Korea would be placed under four-power multinational trusteeship. After Japan's surrender, this agreement was modified to a joint Soviet-American occupation

of Korea. The agreement was that Korea would be divided and occupied by the Soviets from the north and the Americans from the south.

Korea, formerly under Japanese rule

Korea, formerly under Japanese rule

, and which had been partially occupied by the Red Army following the Soviet Union's entry into the war against Japan, was divided at the 38th parallel on the orders of the U.S. War Department. A U.S. military government in southern Korea was established in the capital city of Seoul

. The American military commander, Lt. Gen.

John R. Hodge

, enlisted many former Japanese administrative officials to serve in this government. North of the military line, the Soviets administered the disarming and demobilisation of repatriated Korean nationalist guerrillas who had fought on the side of Chinese nationalists against the Japanese in Manchuria during World War II. Simultaneously, the Soviets enabled a build-up of heavy armaments to pro-communist forces in the north. The military line became a political line in 1948, when separate republics emerged on both sides of the 38th parallel, each republic claiming to be the legitimate government of Korea. It culminated in the north invading the south, and the Korean War

two years later.

The Nationalist

The Nationalist

and Communist

Chinese forces resumed their civil war

, which had been temporarily suspended when they fought together against Japan. Despite U.S. support to the Kuomintang

, Communist forces were ultimately victorious and established the People's Republic of China

on the mainland. Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek

's Nationalist forces retreated to Taiwan

.

. The Emergency would endure for the next 12 years, ending in 1960. In 1967, communist leader Chin Peng

revived hostilities, known as the Communist Insurgency War

, ending in the defeat of the communists by British Commonwealth forces in 1969.

, which had fallen to Japan during the war. Following the reoccupation, the Việt Minh launched a rebellion against the French authorities, who were backed by the U.S.

Japan invaded and occupied Indonesia

Japan invaded and occupied Indonesia

during the war and replaced much of the Dutch

colonial state. Although the top positions were held by Japanese, the internment of all Dutch citizens meant that Indonesians filled many leadership and administrative positions. Following the Japanese surrender in August 1945, nationalist leaders Sukarno

and Mohammad Hatta

declared Indonesian independence. A four and a half-year struggle followed as the Dutch tried to re-establish their colony, using a significant portion of their Marshall Plan aid to this end. The Dutch were directly helped by UK forces who sought to re-establish the colonial dominions in Asia. The UK also kept 35,000 Japanese Surrendered Personnel

under arms to fight the Indonesians.

Although Dutch forces re-occupied most of Indonesia's territory a guerrilla struggle ensued, and the majority of Indonesians, and ultimately international opinion, favoured Indonesian independence. In December 1949, the Netherlands formally recognised Indonesian sovereignty.

British covert operations in the Baltic States, which began in 1944 against the Nazis, escalated after the war. In Operation Jungle

British covert operations in the Baltic States, which began in 1944 against the Nazis, escalated after the war. In Operation Jungle

, the Secret Intelligence Service

(known as MI6) recruited and trained Balts for the clandestine work in the Baltic states between 1948 and 1955. Leaders of the operation included Alfons Rebane

, Stasys Žymantas, and Rūdolfs Silarājs. The agents were transported under the cover of the "British Baltic Fishery Protection Service". They launched from British-occupied Germany, using a converted World War II E-boat

captained and crewed by former members of the wartime German navy

. British intelligence also trained and infiltrated anti-communist agents into Russia from across the Finnish border, with orders to assassinate Soviet officials. In the end, counter-intelligence supplied to the KGB

by Kim Philby

allowed the KGB to penetrate and ultimately gain control of MI6's entire intelligence network in the Baltic states.

Vietman

and the Middle East

would later damage the reputation gained by the US during its successes in Europe.

The KGB believed that the Third World

rather than Europe was the arena in which it could win the Cold War

. Moscow would in later years fuel an arms buildup in Africa

. In later years, African countries used as proxies in the Cold War would often become "failed states" of their own.

When the divisions of postwar Europe began to emerge, the war crimes programmes and denazification policies of Britain and the United States were relaxed in favour of recruiting German scientists, especially nuclear and long-range rocket scientists. Many of these, prior to their capture, had worked on developing the German V-2 long-range rocket at the Baltic coast German Army Research Center Peenemünde

When the divisions of postwar Europe began to emerge, the war crimes programmes and denazification policies of Britain and the United States were relaxed in favour of recruiting German scientists, especially nuclear and long-range rocket scientists. Many of these, prior to their capture, had worked on developing the German V-2 long-range rocket at the Baltic coast German Army Research Center Peenemünde

. Western Allied occupation force officers in Germany were ordered to refuse to cooperate with the Soviets in sharing captured wartime secret weapons.

In Operation Paperclip

, beginning in 1945, the United States imported 1,600 German scientists and technicians, as part of the intellectual reparations owed to the U.S. and the UK, including about $10 billion (US$ billion in dollars) in patents and industrial processes. In late 1945, three German rocket-scientist groups arrived in the U.S. for duty at Fort Bliss, Texas, and at White Sands Proving Grounds, New Mexico

, as “War Department Special Employees”.

The wartime activities of some Operation Paperclip scientists would later be investigated. Arthur Rudolph

left the United States in 1984,in order to not be prosecuted. Similarly, Georg Rickhey, who came to the United States under Operation Paperclip in 1946, was returned to Germany to stand trial at the Mittelbau-Dora

war crimes trial in 1947. Following his acquittal, he returned to the United States in 1948 and eventually became a U.S. citizen.

The Soviets began Operation Osoaviakhim

in 1946. NKVD

and Soviet army units effectively deported thousands of military-related technical specialists from the Soviet occupation zone of post-war Germany to the Soviet Union. The Soviets used 92 trains to transport the specialists and their families, an estimated 10,000-15,000 people. Much related equipment was also moved, the aim being to virtually transplant research and production centres, such as the relocated V-2 rocket

centre at Mittelwerk

Nordhausen

, from Germany to the Soviet Union. Among the people moved were Helmut Gröttrup

and about two hundred scientists and technicians from Mittelwerk

. Personnel were also taken from AEG

, BMW

's Stassfurt jet propulsion group, IG Farben

's Leuna chemical works, Junkers

, Schott AG, Siebel

, Telefunken

, and Carl Zeiss AG.

The operation was commanded by NKVD deputy Colonel General Serov

, outside the control of the local Soviet Military Administration

. The major reason for the operation was the Soviet fear of being condemned for noncompliance with Allied Control Council

agreements on the liquidation of German military installations. Some Western observers thought Operation Osoaviakhim was a retaliation for the failure of the Socialist Unity Party

in elections, though Osoaviakhim was clearly planned before that.

, which officially came into existence on October 24, 1945. The UN adopted The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

in 1948, "as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations." The Soviet Union abstained from voting on adoption of the declaration. The U.S. did not ratify the social and economic rights

sections.

had collapsed with 70% of the industrial infrastructure destroyed. The property damage in the Soviet Union consisted of complete or partial destruction of 1,710 cities and towns, 70,000 villages/hamlets, and 31,850 industrial establishments. The strength of the economic recovery following the war varied throughout the world, though in general it was quite robust. In Europe, West Germany

, after having continued to decline economically during the first years of the Allied occupation, later experienced a remarkable recovery

, and had by the end of the 1950s doubled production from its pre-war levels. Italy came out of the war in poor economic condition, but by 1950s, the Italian economy was marked by stability and high growth. France rebounded quickly and enjoyed rapid economic growth and modernisation under the Monnet Plan

. The UK, by contrast, was in a state of economic ruin after the war and continued to experience relative economic decline for decades to follow.

The Soviet Union also experienced a rapid increase in production in the immediate post-war era. Japan experienced rapid

economic growth, becoming one of the most powerful economies in the world by the 1980s. China, following the conclusion of its civil war, was essentially bankrupt. By 1953, economic restoration seemed fairly successful as production had resumed pre-war levels. This growth rate mostly persisted, though it was interrupted by economic experiments during the disastrous Great Leap Forward

.

At the end of the war, the United States produced roughly half of the world's industrial output. This dominance had lessened significantly by the early 1970s.

Nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was a competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War...

. This emerged into an environment dominated by a international balance of power

Balance of power in international relations

In international relations, a balance of power exists when there is parity or stability between competing forces. The concept describes a state of affairs in the international system and explains the behavior of states in that system...

that had changed significantly from the status quo before the war. A number of boundary disputes emerged in countries affected by the war, and the dwindling of power of the imperial nations such as Britain and France resulted in an increase in the demand for national self-determination

Self-determination

Self-determination is the principle in international law that nations have the right to freely choose their sovereignty and international political status with no external compulsion or external interference...

in European colonial territories.

The immediate post-war period in Europe was dominated by the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

annexing, or converting into Soviet Socialist Republics, all the countries captured by the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

driving the German invaders out of central and eastern Europe. New Soviet satellite states rose in Poland

People's Republic of Poland

The People's Republic of Poland was the official name of Poland from 1952 to 1990. Although the Soviet Union took control of the country immediately after the liberation from Nazi Germany in 1944, the name of the state was not changed until eight years later...

, Bulgaria, Hungary

People's Republic of Hungary

The People's Republic of Hungary or Hungarian People's Republic was the official state name of Hungary from 1949 to 1989 during its Communist period under the guidance of the Soviet Union. The state remained in existence until 1989 when opposition forces consolidated in forcing the regime to...

, Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was the official name of Czechoslovakia from 1960 until end of 1989 , a Soviet satellite state of the Eastern Bloc....

, Romania, Albania, and East Germany; the last of these was created from the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany. Yugoslavia emerged as an independent Communist state, allied but not aligned with the Soviet Union, owing to the independent nature of the military victory of the Partisans of Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz Tito

Marshal Josip Broz Tito – 4 May 1980) was a Yugoslav revolutionary and statesman. While his presidency has been criticized as authoritarian, Tito was a popular public figure both in Yugoslavia and abroad, viewed as a unifying symbol for the nations of the Yugoslav federation...

in the Yugoslav Front.

The Allies established the Far Eastern Commission

Far Eastern Commission

It was agreed at the Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministers, and made public in communique issued at the end of the conference on December 27, 1945 that the Far Eastern Advisory Commission would become the Far Eastern Commission , it would be based in Washington, and would oversee the Allied...

and Allied Council For Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

to administer their occupation of that country. They demilitarised the nation, dismantled its arms industry, and installed a democratic government with a new constitution.

A similar body, the Allied Control Council

Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council or Allied Control Authority, known in the German language as the Alliierter Kontrollrat and also referred to as the Four Powers , was a military occupation governing body of the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany after the end of World War II in Europe...

, administered occupied Germany. In accordance with the Potsdam Conference

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference was held at Cecilienhof, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, occupied Germany, from 16 July to 2 August 1945. Participants were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States...

agreements promising territorial concessions to the Soviet Union in the Far East in return for entering the war against Japan, the Soviet Union occupied and subsequently annexed the strategic island of Sakhalin

Sakhalin

Sakhalin or Saghalien, is a large island in the North Pacific, lying between 45°50' and 54°24' N.It is part of Russia, and is Russia's largest island, and is administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast...

.

Immediate effects

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, too, had been heavily affected. In response, in 1947, U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall

George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall was an American military leader, Chief of Staff of the Army, Secretary of State, and the third Secretary of Defense...

devised the "European Recovery Program", which became known as the Marshall Plan

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was the large-scale American program to aid Europe where the United States gave monetary support to help rebuild European economies after the end of World War II in order to combat the spread of Soviet communism. The plan was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948...

. Under the plan, during 1948-1952 the United States government allocated US$13 billion (US$ billion in dollars) for the reconstruction of Western Europe

Western Europe

Western Europe is a loose term for the collection of countries in the western most region of the European continents, though this definition is context-dependent and carries cultural and political connotations. One definition describes Western Europe as a geographic entity—the region lying in the...

.

United Kingdom

By the end of the war, the economy of the United KingdomUnited Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

was exhausted. More than a quarter of its national wealth had been spent. Until the introduction of Lend-Lease the UK had been spending its assets to purchase American equipment including aircraft and ships - over £437 million on aircraft alone. Lend-lease came just before its reserved were exhausted. Britain put 55% of its total labour force into in war production.

In Spring 1945, the Labour Party

Labour Party (UK)

The Labour Party is a centre-left democratic socialist party in the United Kingdom. It surpassed the Liberal Party in general elections during the early 1920s, forming minority governments under Ramsay MacDonald in 1924 and 1929-1931. The party was in a wartime coalition from 1940 to 1945, after...

withdrew from the wartime coalition government, forcing a general election

United Kingdom general election, 1945

The United Kingdom general election of 1945 was a general election held on 5 July 1945, with polls in some constituencies delayed until 12 July and in Nelson and Colne until 19 July, due to local wakes weeks. The results were counted and declared on 26 July, due in part to the time it took to...

. Following a landslide victory, Labour held more than 60% of the seats in the House of Commons and formed a new government on 26 July 1945 under Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955...

.

Britain's war debt was described by some in the American administration as a "millstone round the neck of the British economy". Although there were suggestions for an international conference to tackle the issue, in August 1945 the U.S. announced unexpectedly that the Lend-Lease programme was to end immediately.

The abrupt withdrawal of American Lend Lease support to Britain on 2 September 1945 dealt a severe blow to the plans of the new government. It was only with the completion of the Anglo-American loan

Anglo-American loan

The Anglo-American Loan Agreement was a post World War II loan made to the United Kingdom by the United States on 15 July 1946, and paid off 29 December 2006...

by the United States to Great Britain on 15 July 1946 that some measure of economic stability was restored. However, the loan was made primarily to support British overseas expenditure in the immediate post-war years and not to implement the Labour government's policies for domestic welfare reforms and the nationalisation of key industries.

Although the loan was agreed on reasonable terms its conditions included what proved to be damaging fiscal conditions for Sterling. From 1946-1948 the UK had to introduce bread rationing which it had never had to do during the war.

Soviet Union

Siege of Leningrad

The Siege of Leningrad, also known as the Leningrad Blockade was a prolonged military operation resulting from the failure of the German Army Group North to capture Leningrad, now known as Saint Petersburg, in the Eastern Front theatre of World War II. It started on 8 September 1941, when the last...

; conditions in German prisons and concentration camps; mass shootings of civilians; harsh labour in German industry; famine and disease; conditions in Soviet camps; and service in German or German-controlled military units fighting the Soviet Union. The population would not return to its pre-war level for 30 years.

Soviet ex-POWs and civilians repatriated from abroad were suspected of having been Nazi collaborators, and 226,127 of them were sent to forced labour camps after scrutiny by Soviet intelligence, NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

. Many ex-POWs and young civilians were also conscripted to serve in the Red Army. Others worked in labour battalions to rebuild infrastructure destroyed during the war.

The economy had been devastated. Roughly a quarter of the Soviet Union's capital resources were destroyed, and industrial and agricultural output in 1945 fell far short of pre-war levels. To help rebuild the country, the Soviet government obtained limited credits from Britain and Sweden; it refused assistance offered by the United States under the Marshall Plan. Instead, the Soviet Union compelled Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe to supply machinery and raw materials. Germany and former Nazi satellites made reparations to the Soviet Union. The reconstruction programme emphasised heavy industry to the detriment of agriculture and consumer goods. By 1953, steel production was twice its 1940 level, but the production of many consumer goods and foodstuffs was lower than it had been in the late 1920s.

Germany

Alsace-Lorraine

The Imperial Territory of Alsace-Lorraine was a territory created by the German Empire in 1871 after it annexed most of Alsace and the Moselle region of Lorraine following its victory in the Franco-Prussian War. The Alsatian part lay in the Rhine Valley on the west bank of the Rhine River and east...

was returned to France. The Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

reverted back to Czechoslovakia following the European Advisory Commission

European Advisory Commission

The formation of the European Advisory Commission was agreed on at the Moscow Conference on October 30, 1943 between the foreign ministers of the United Kingdom, Anthony Eden, the United States, Cordell Hull, and the Soviet Union, Molotov, and confirmed at the Tehran Conference in November...

's decision to delimit German territory to be the territory it held on December 31, 1937. Close to one quarter of pre-war (1937) Germany was de facto annexed by the Allies; roughly 10 million Germans were either expelled from this territory or not permitted to return to it if they had fled during the war. The remainder of Germany was partitioned into four zones of occupation, coordinated by the Allied Control Council

Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council or Allied Control Authority, known in the German language as the Alliierter Kontrollrat and also referred to as the Four Powers , was a military occupation governing body of the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany after the end of World War II in Europe...

. The Saar

Saar (protectorate)

The Saar Protectorate was a German borderland territory twice temporarily made a protectorate state. Since rejoining Germany the second time in 1957, it is the smallest Federal German Area State , the Saarland, not counting the city-states Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen...

was detached and put in economic union with France in 1947. In 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany

West Germany

West Germany is the common English, but not official, name for the Federal Republic of Germany or FRG in the period between its creation in May 1949 to German reunification on 3 October 1990....

was created out of the Western zones. The Soviet zone became the German Democratic Republic

German Democratic Republic

The German Democratic Republic , informally called East Germany by West Germany and other countries, was a socialist state established in 1949 in the Soviet zone of occupied Germany, including East Berlin of the Allied-occupied capital city...

.

Germany paid reparations

German reparations for World War II

After World War II, both West Germany and East Germany were obliged to pay war reparations to the Allied governments, according to the Potsdam Conference...

to the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union, mainly in the form of dismantled factories

Industrial plans for Germany

The Industrial plans for Germany were designs the Allies considered imposing on Germany in the aftermath of World War II to reduce and manage Germany's industrial capacity.-Background:...

, forced labour

Forced labor of Germans after World War II

Forced labour of Germans after World War II refers to the Allied use of German civilians and captured soldiers for forced labor in years following World War II ....

, and coal. German standard of living

Standard of living

Standard of living is generally measured by standards such as real income per person and poverty rate. Other measures such as access and quality of health care, income growth inequality and educational standards are also used. Examples are access to certain goods , or measures of health such as...

was to be reduced to its 1932 level. Beginning immediately after the German surrender and continuing for the next two years, the U.S. and Britain pursued an "intellectual reparations" programme to harvest all technological and scientific know-how as well as all patents in Germany. The value of these amounted to around US$10 billion (US$ billion in dollars). In accordance with the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947

Paris Peace Treaties, 1947

The Paris Peace Conference resulted in the Paris Peace Treaties signed on February 10, 1947. The victorious wartime Allied powers negotiated the details of treaties with Italy, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Finland .The...

, reparations were also assessed from the countries of Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

, Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

, and Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

.

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff is a body of senior uniformed leaders in the United States Department of Defense who advise the Secretary of Defense, the Homeland Security Council, the National Security Council and the President on military matters...

and Generals Lucius D. Clay

Lucius D. Clay

General Lucius Dubignon Clay was an American officer and military governor of the United States Army known for his administration of Germany immediately after World War II. Clay was deputy to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1945; deputy military governor, Germany 1946; commander in chief, U.S....

and George Marshall

George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall was an American military leader, Chief of Staff of the Army, Secretary of State, and the third Secretary of Defense...

, the Truman administration

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

accepted that economic recovery in Europe could not go forward without the reconstruction of the German industrial base on which it had previously had been dependent. In July 1947, President Truman rescinded on "national security grounds" the directive that had ordered the U.S. occupation forces to "take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany." A new directive recognised that "[a]n orderly, prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany." From mid-1946 onwards Germany received U.S. government aid through the GARIOA

GARIOA

Government and Relief in Occupied Areas was a program under which the US after the 1945 end of World War II from 1946 onwards provided emergency aid to the occupied nations, Japan, Germany, Austria. The aid was predominantly in the form of food to alleviate starvation in the occupied...

programme. From 1948 onwards West Germany also became a minor beneficiary of the Marshall Plan. Volunteer organisations had initially been forbidden to send food, but in early 1946 the Council of Relief Agencies Licensed to Operate in Germany was founded. The prohibition against sending CARE Package

CARE Package

The CARE Package was the original unit of aid distributed by the humanitarian organization CARE...

s to individuals in Germany was rescinded on 5 June 1946.

After the German surrender, the International Red Cross was prohibited from providing aid such as food or visiting POW camps for Germans inside Germany. However, after making approaches to the Allies in the autumn of 1945 it was allowed to investigate the camps in the UK and French occupation zones of Germany, as well as to provide relief to the prisoners held there. On February 4, 1946, the Red Cross was permitted to visit and assist prisoners also in the U.S. occupation zone of Germany, although only with very small quantities of food. The Red Cross petitioned successfully for improvements to be made in the living conditions of German POWs.

Austria

Austria was separated from Germany and divided into four zones of occupation. These zones reunited in 1955 to become the Republic of Austria.Japan

After the war, the Allies rescinded Japanese pre-war annexations such as ManchuriaManchuria

Manchuria is a historical name given to a large geographic region in northeast Asia. Depending on the definition of its extent, Manchuria usually falls entirely within the People's Republic of China, or is sometimes divided between China and Russia. The region is commonly referred to as Northeast...

, and Korea

Korea

Korea ) is an East Asian geographic region that is currently divided into two separate sovereign states — North Korea and South Korea. Located on the Korean Peninsula, Korea is bordered by the People's Republic of China to the northwest, Russia to the northeast, and is separated from Japan to the...

became independent. At the Yalta Conference

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference, sometimes called the Crimea Conference and codenamed the Argonaut Conference, held February 4–11, 1945, was the wartime meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union, represented by President Franklin D...

, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

had secretly traded the Japanese Kurils and south Sakhalin to the Soviet Union in return for Soviet entry in the war with Japan. In response, the Soviet Union annexed the Kuril Islands

Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands , in Russia's Sakhalin Oblast region, form a volcanic archipelago that stretches approximately northeast from Hokkaidō, Japan, to Kamchatka, Russia, separating the Sea of Okhotsk from the North Pacific Ocean. There are 56 islands and many more minor rocks. It consists of Greater...

, provoking the Kuril Islands dispute

Kuril Islands dispute

The Kuril Islands dispute , also known as the , is a dispute between Japan and Russia over sovereignty over the South Kuril Islands. The disputed islands, which were occupied by Soviet forces during the Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation at the end of World War II, are under Russian...

, which was ongoing as of 2011.

Hundreds of thousands of Japanese were forced to relocate to the Japanese main islands. Okinawa became a main U.S. staging point. The U.S. covered large areas of it with military bases and continued to occupy it until 1972, years after the end of the occupation of the main islands. The bases still remain. To skirt the Geneva Convention, the Allies classified many Japanese soldiers as Japanese Surrendered Personnel

Japanese Surrendered Personnel

Japanese Surrendered Personnel is a designation for captive Japanese soldiers...

instead of POWs and used them as forced labour until 1947. The UK, France, and the Netherlands conscripted some Japanese troops to fight colonial resistances elsewhere in Asia. General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur was an American general and field marshal of the Philippine Army. He was a Chief of Staff of the United States Army during the 1930s and played a prominent role in the Pacific theater during World War II. He received the Medal of Honor for his service in the...

established the International Military Tribunal for the Far East

International Military Tribunal for the Far East

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East , also known as the Tokyo Trials, the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, or simply the Tribunal, was convened on April 29, 1946, to try the leaders of the Empire of Japan for three types of crimes: "Class A" crimes were reserved for those who...

. The Allies collected reparations from Japan.

To further remove Japan as a potential future military threat, the Far Eastern Commission

Far Eastern Commission

It was agreed at the Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministers, and made public in communique issued at the end of the conference on December 27, 1945 that the Far Eastern Advisory Commission would become the Far Eastern Commission , it would be based in Washington, and would oversee the Allied...

decided to de-industrialise Japan, with the goal of reducing Japanese standard of living to what prevailed between 1930 and 1934. In the end, the de-industrialisation program in Japan was implemented to a lesser degree than the one in Germany. Japan received emergency aid from GARIOA, as did Germany. In early 1946, the Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia

Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia

Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia was created in April 1946 by eleven volunteer relief organizations, it was the Asian equivalent to CRALOG in Europe....

were formed and permitted to supply Japanese with food and clothes. In April 1948 the Johnston Committee Report recommended that the economy of Japan should be reconstructed due to the high cost to U.S. taxpayers of continuous emergency aid.

Survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

, known as hibakusha

Hibakusha

The surviving victims of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are called , a Japanese word that literally translates to "explosion-affected people"...

(被爆者), were ostracized by Japanese society. Japan provided no special assistance to these people until 1952. By the 65th anniversary of the bombings, total casualties from the initial attack and later deaths reached about 270,000 in Hiroshima and 150,000 in Nagasaki. About 230,000 hibakusha were still alive as of 2010, and about 2,200 were suffering from radiation-caused illnesses as of 2007.

Finland

In the Winter WarWinter War

The Winter War was a military conflict between the Soviet Union and Finland. It began with a Soviet offensive on 30 November 1939 – three months after the start of World War II and the Soviet invasion of Poland – and ended on 13 March 1940 with the Moscow Peace Treaty...

of 1939, the Soviet Union invaded neutral Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

and annexed some of its territory. The Finnish attempt to recover this territory in the Continuation War

Continuation War

The Continuation War was the second of two wars fought between Finland and the Soviet Union during World War II.At the time of the war, the Finnish side used the name to make clear its perceived relationship to the preceding Winter War...

of 1941-44 failed. Finland retained its independence following the war but remained subject to Soviet-imposed constraints in its domestic affairs.

The Baltic states

In 1940 the Soviet Union invaded and annexed the neutral Baltic statesBaltic states

The term Baltic states refers to the Baltic territories which gained independence from the Russian Empire in the wake of World War I: primarily the contiguous trio of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania ; Finland also fell within the scope of the term after initially gaining independence in the 1920s.The...

, Estonia

Estonia

Estonia , officially the Republic of Estonia , is a state in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea, to the south by Latvia , and to the east by Lake Peipsi and the Russian Federation . Across the Baltic Sea lies...

, Latvia

Latvia

Latvia , officially the Republic of Latvia , is a country in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by Estonia , to the south by Lithuania , to the east by the Russian Federation , to the southeast by Belarus and shares maritime borders to the west with Sweden...

, and Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

. In June 1941, the Soviet governments of the Baltic states carried out mass deportations

June deportation

June deportation was the first in the series of mass Soviet deportations of tens of thousands of people from the Baltic states, Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova starting June 14, 1941 that followed the occupation and annexation of the Baltic states. The procedure for deporting the "anti-Soviet...

of "enemies of the people"; as a result, many treated the invading Nazis as liberators when they invaded only a week later.

The Atlantic Charter

Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a pivotal policy statement first issued in August 1941 that early in World War II defined the Allied goals for the post-war world. It was drafted by Britain and the United States, and later agreed to by all the Allies...

promised self-determination to peoples deprived of it during the war. The British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, argued for a weaker interpretation of the Charter to permit the Soviet Union to continue to control the Baltic states. In March 1944 the U.S. accepted Churchill's view that the Atlantic Charter did not apply to the Baltic states.

With the return of Soviet troops at the end of the war, the Forest Brothers

Forest Brothers

The Forest Brothers were Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian partisans who waged a guerrilla war against Soviet rule during the Soviet invasion and occupation of the three Baltic states during, and after, World War II...

mounted a guerrilla war. This continued until the mid-1950s.

Population displacement

Historical Eastern Germany

The former eastern territories of Germany are those provinces or regions east of the current eastern border of Germany which were lost by Germany during and after the two world wars. These territories include the Province of Posen and East Prussia, Farther Pomerania, East Brandenburg and Lower...

of the Oder-Neisse line

Oder-Neisse line

The Oder–Neisse line is the border between Germany and Poland which was drawn in the aftermath of World War II. The line is formed primarily by the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, and meets the Baltic Sea west of the seaport cities of Szczecin and Świnoujście...

, including the industrial regions of Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

. The German state of the Saar was temporarily a protectorate of France but later returned to German administration.

The number expelled from Germany, as set forth at Potsdam, totalled roughly 12 million, including seven million from Germany proper and three million from the Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

. Mainstream estimates of casualties from the expulsions range between 500,000 and two million dead.

The Soviet Union expelled two million Poles from east of the new border approximating the Curzon Line

Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was put forward by the Allied Supreme Council after World War I as a demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and Bolshevik Russia and was supposed to serve as the basis for a future border. In the wake of World War I, which catalysed the Russian Revolution of 1917, the...

. This border change reversed the results of the 1919-1920 Polish-Soviet War

Polish-Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War was an armed conflict between Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine and the Second Polish Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic—four states in post–World War I Europe...

. Former Polish cities such as L'vov

Lviv

Lviv is a city in western Ukraine. The city is regarded as one of the main cultural centres of today's Ukraine and historically has also been a major Polish and Jewish cultural center, as Poles and Jews were the two main ethnicities of the city until the outbreak of World War II and the following...

came under control of the of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Additionally, the Soviet Union transferred more than two million people within their own borders; these included Germans, Finns, Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars or Crimeans are a Turkic ethnic group that originally resided in Crimea. They speak the Crimean Tatar language...

, and Chechens.

During the war, the United States government interned approximately 110,000 Japanese American

Japanese American

are American people of Japanese heritage. Japanese Americans have historically been among the three largest Asian American communities, but in recent decades have become the sixth largest group at roughly 1,204,205, including those of mixed-race or mixed-ethnicity...

s and Japanese

Japanese people

The are an ethnic group originating in the Japanese archipelago and are the predominant ethnic group of Japan. Worldwide, approximately 130 million people are of Japanese descent; of these, approximately 127 million are residents of Japan. People of Japanese ancestry who live in other countries...

who lived along the Pacific coast of the United States in the wake of Imperial Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

. Canada interned approximately 22,000 Japanese Canadians, 14,000 of whom were born in Canada. After the war, some internees chose to return to Japan, while most remained in North America.

In Europe

As Soviet troops marched across the Balkans, they committed rapes and robberies in RomaniaRomania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

, Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

, Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

and Yugoslavia. The population of Bulgaria was largely spared this treatment, due possibly to a sense of ethnic kinship or to the leadership of Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin

Fyodor Tolbukhin

Fyodor Ivanovich Tolbukhin was a Soviet military commander.-Biography:Tolbukhin was born into a peasant family in the province of Yaroslavl, north-east of Moscow. He volunteered for the Imperial Army in 1914 at the outbreak of World War I. He was steadily promoted, advancing from private to...

. The population of Germany was treated significantly worse. Rape and murder of German civilians was as bad as, and sometimes worse than, Nazi propaganda had anticipated. Political officers encouraged Soviet troops to seek revenge and terrorise the German population. Estimates of the numbers of rapes committed by Soviet soldiers range from tens of thousands to two million. About one-third of all German women in Berlin were raped by Soviet forces. A substantial minority were raped multiple times. In Berlin, contemporary hospital records indicate between 95,000 and 130,000 women were raped by Soviet troops. About 10,000 of these women died, mostly by suicide. Over 4.5 million Germans fled towards the West. The Soviets initially had no rules against their troops fraternising with German women, but by 1947 they started to isolate their troops from the German population in an attempt to stop rape and robbery by the troops. Not all Soviet soldiers participated in these activities.

Foreign reports of Soviet brutality were denounced as false. Rape, robbery, and murder were blamed on German bandits impersonating Soviet soldiers. Some justified Soviet brutality towards German civilians based on previous brutality of German troops toward Russian civilians. Until the reunification of Germany, East German histories virtually ignored the actions of Soviet troops, and Russian histories still tend to do so. Reports of mass rapes by Soviet troops were often dismissed as anti-Communist propaganda or the normal byproduct of war.

Rapes also occurred under other occupation forces, though the majority were committed by Soviet troops. French Moroccan troops matched the behavior of Soviet troops when it came to rape, especially in the early occupations of Baden

Baden

Baden is a historical state on the east bank of the Rhine in the southwest of Germany, now the western part of the Baden-Württemberg of Germany....

and Württemberg

Württemberg

Württemberg , formerly known as Wirtemberg or Wurtemberg, is an area and a former state in southwestern Germany, including parts of the regions Swabia and Franconia....

. In a letter to the editor of TIME

Time

Time is a part of the measuring system used to sequence events, to compare the durations of events and the intervals between them, and to quantify rates of change such as the motions of objects....

published in September 1945, an American army sergeant

Sergeant

Sergeant is a rank used in some form by most militaries, police forces, and other uniformed organizations around the world. Its origins are the Latin serviens, "one who serves", through the French term Sergent....

wrote, "Our own Army and the British Army along with ours have done their share of looting and raping ... This offensive attitude among our troops is not at all general, but the percentage is large enough to have given our Army a pretty black name, and we too are considered an army of rapists." Robert Lilly’s analysis of military records led him to conclude about 14,000 rapes occurred in Britain, France and Germany at the hands of U.S. soldiers between 1942 to 1945. Lilly assumed that only 5% of rapes by American soldiers were reported, making 17,000 GI rapes a possibility, while analysts estimate that 50% of (ordinary peace-time) rapes are reported. Supporting Lilly's lower figure is the "crucial difference" that for World War II military rapes "it was the commanding officer, not the victim, who brought charges".

German soldiers left many war children

War children

A war child refers to a child born to a native parent and a parent belonging to a foreign military force . It also refers to children of parents collaborating with an occupying force...

behind in nations such as France and Denmark, which were occupied for an extended period. After the war, the children and their mothers often suffered recriminations. In Norway, the “Tyskerunger“ (German-kids) suffered greatly.

Europe

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

, Roosevelt, and Churchill exchanged a heated correspondence over whether the Polish Government in Exile, backed by Roosevelt and Churchill, or the Provisional Government, backed by Stalin, should be recognised. Stalin won.

A number of allied leaders felt that war between the United States and the Soviet Union was likely. On May 19, 1945, American Under-Secretary of State Joseph Grew

Joseph Grew

Joseph Clark Grew was a United States diplomat and career foreign service officer. He was the chargé d'affaires at the U.S. embassy in Vienna when Austria-Hungary severed diplomatic relations with the United States on April 9, 1917. Later he was the U.S. Ambassador to Denmark 1920–1921 and U.S....

went so far as to say that it was inevitable.

On March 5, 1946, in his "Sinews of Peace" (Iron Curtain) speech at Westminster College

Westminster College, Missouri

Westminster College is a private, selective, liberal arts institution in Fulton, Missouri, USA. It was founded by Presbyterians in 1849 as Fulton College and assumed the present name in 1851. The are located on the campus. The National Churchill Museum is a national historic site and includes...

in Fulton, Missouri

Fulton, Missouri

Fulton is a city in Callaway County, Missouri, the United States of America. It is part of the Jefferson City, Missouri Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 12,790 in the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Callaway County...