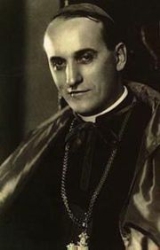

Aloysius Stepinac

Encyclopedia

Aloysius Viktor Stepinac , also known as Blessed Aloysius Stepinac, was a Croatian

Catholic cardinal and Archbishop of Zagreb from 1937 to 1960. In 1998 he was declared a martyr

and beatified

by Pope John Paul II

.

Stepinac was ordained on October 26, 1930 by archbishop Giuseppe Palica

, and in 1931 he became a parish curate in Zagreb

. He established the archdiocesan branch of Caritas

in 1931, and was appointed coadjutor to the see of Zagreb in 1934. When Archbishop Anton Bauer died on December 7, 1937, Stepinac succeeded him as the Archbishop of Zagreb. During World War II

, on 6 April 1941, Yugoslavia

was invaded by Nazi Germany

, who established the Ustaše

-led Independent State of Croatia

. As archbishop of the puppet state's capital, Stepinac had close associations with the Ustaše leaders during the Nazi occupation, had issued proclamations celebrating the NDH, and welcomed the Ustaše leaders. Stepinac also objected against the persecution of Jews and Nazi laws, helped Jews and others to escape and criticized Ustaše atrocities in front of Zagreb Cathedral

in 1943.

After the war he publicly condemned the new Yugoslav government and its actions during World War II, especially for murders of priests by Communist militants. Yugoslav authorities indicted the archbishop on multiple counts of war crimes and collaboration

with the enemy during wartime. The trial was depicted in the West as a typical communist "show trial", biased against the archbishop; however, some claim the trial was "carried out with proper legal procedure". In a verdict that polarized public opinion both in Yugoslavia and beyond, the Yugoslav authorities found him guilty of collaboration

with the fascist

Ustaše movement and complicity in allowing the forced conversions of Orthodox

Serbs

to Catholicism

.

After foreign and domestic pressure, Stepinac was released from Lepoglava prison

. In 1952 he was appointed cardinal by Pope Pius XII

. Stepinac died while still under confinement in his parish, almost certainly as the result of poisoning by his Communist captors. In October 3, 1998, Pope John Paul II

declared him a martyr

and beatified

him before 500,000 Croatians in Marija Bistrica

near Zagreb. This again polarized public opinion.

to study in the Classical Gymnasium

and graduated in 1916. Just before his eighteenth birthday he was conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian Army

. He was attached to the 96th Karlovac Infantry Regiment before going to Rijeka

for six months training. He was then sent to serve on the Italian Front

during World War I

. In July 1918 he was captured by the Italians who held him as a prisoner of war for five months. After the formation of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

, he was no longer treated as an enemy soldier, and he instead volunteered for the Yugoslav legion that was engaged on the Salonika Front. A few months later, he was demobilized with the rank of Second Lieutenant

and returned home in the spring of 1919.

For service in the Yugoslav forces during World War I, he was awarded the Order of the Star of Karađorđe, an award for heroism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

. After the war he enrolled at the faculty of agronomy of the University of Zagreb

, but left it after only one semester and returned home to help his father. In 1922 Stepinac was part of the Croatian Eagles Association

and traveled to the Catholic Eagle slet

in Brno

, Czechoslovakia

. He was at the front of the group's ceremonial procession, carrying a Croatian flag. In 1924, he traveled to Rome to study for the priesthood at the Collegium Germanicum et Hungaricum

. During his studies there he befriended the future cardinal Franz König when the two played together on the same volleyball team. He was ordained on October 26, 1930 by archbishop Giuseppe Palica

in a ceremony which also included Franjo Šeper

. On November 1, he said his first mass at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore

. In 1931 he became a parish curate in Zagreb

. He established the archdiocesan branch of Caritas

in 1931.

because king Alexander I of Yugoslavia

needed to agree with the appointment. Upon his naming, he took In te, Domine, speravi (O Lord, in Thee have I trusted) as his motto. During this period, King Alexander ran a dictatorship in the country. Stepinac was among those who signed the Zagreb memorandum demanding from the king the release of Vladko Maček

and other Croatian politicians, as well as a general amnesty. Stepinac was denied access by Yugoslav authorities to see Maček to thank him for his well-wishes concerning Stepinac's appointment as coadjutor.

King Alexander was assassinated in Marseilles in 1934, and Stepinac along with Bishops Antun Akšamović, Dionizije Njaradi and Gregorij Rožman

were given special permission from the Holy See

to attend the funeral in an Orthodox church. Croatian politician Ante Trumbić

spoke to Stepinac on several occasions in 1934. On his relation with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

, he recorded that Stepinac has "loyalty to the state as it is, but with the condition that the state acts towards the Catholic Church as it does to all just denominations and that it guarantees them freedom". On July 30 he received French deputy Robert Schuman

, whom he told: "There is no justice in Yugoslavia. [...] The Catholic Church endures much".

In 1936, he climbed the Mount Triglav

, the tallest peak in Yugoslavia

. In 2006 this climb was commemorated by a memorial chapel being built near the summit. In 1937 he led a pilgrimage to the Holy Land

(then the British Mandate of Palestine). During the pilgrimage he blessed an altar dedicated to the martyr Nikola Tavelić

(who was beatified then, but later canonized).

On December 7, 1937 Archbishop Anton Bauer died, and though still below the age of forty. Stepinac succeeded him as the Archbishop of Zagreb. During Lent

in 1938, Stepinac told a group of students from the University of Zagreb

: "Love towards one's own nation cannot turn a man into a wild animal, which destroys everything and calls for reprisal, but it must ennoble him, so that his own nation secures respect and love for other nations." In 1938, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia held its last election before the outbreak of World War II

. Stepinac voted for Vlatko Maček's opposition list, while Radio Belgrade

spread the false information that he had voted for Milan Stojadinović

's Yugoslav Radical Union

. In the latter half of 1938, Stepinac had an operation for acute appendicitis.

In response to growing tensions in Europe, in 1936 Stepinac helped sponsor a committee aiding Jewish refuges from Austria and Germany. Then in April 1939 Dr. Dragutin Hren spoke to Stepinac about a group of Croatian Discalced Carmelite nuns from Mayerling

who were being pressured by the German Nazis. Stepinac decided to accept the group and place them at a mansion in Brezovica

. Stepinac spent October 6, 1939 in Ivanić-Grad where he administered confirmation for the local parish. In 1940, he received Prince Paul

at St. Mark's Church

as the prince arrived in Zagreb to curry support for the Cvetković-Maček Agreement

. Under Stepinac, Pope Pius XII declared 1940 as a Jubilee

year for Croats

to celebrate 1300 years of Christianity among the Croats. In 1940, the Franciscan Order celebrated 700 years in Croatia and the order's minister general Leonardo Bello came to Zagreb for the event. During his visit Stepinac joined the Franciscan Third Order, on September 29, 1940.

, on 6 April 1941, Yugoslavia

was invaded by Nazi Germany

and its allies. The (Allied

) Yugoslav forces maintained a defence up until 17 April. On 10 April 1941, the Wehrmacht occupied Zagreb

. Having previously agreed to form a Croatian satellite, the Germans and Italians established therein the Independent State of Croatia

, and installed the Ustaše movement into power. Fiercely nationalistic, the Ustaše were also fanatically Catholic. In the Yugoslav political context, they identified Catholicism with Croatian nationalism and, once established in power, set about persecuting and murdering non-Catholics."Fiercely nationalistic, the Ustaše were also fanatically Catholic. In the Yugoslav political context, they identified Catholicism with Croatian nationalism and, once established in power, set about persecuting and murdering non-Catholics."

As the archbishop of the capital, Stepinac enjoyed close associations with the Ustaše leaders. When the Ustaše arrived, following the capitulation of Allied Yugoslavia, he publicly welcomed their arrival and issued proclamations celebrating the NDH. Among other such occasions, on April 21, 1941 the Catholic newspaper Katolički List, over which Stepinac had full control as president of the bishops' conference, reported that he had welcomed Ustaše leaders in meetings on April 12 and 16. With the Yugoslav army still fighting the invaders, this was high treason

and constituted collaboration

with the enemy. It meant Stepinac, a Yugoslav citizen, had breached the oath of allegiance he had given his King when appointed coadjutor. Even though (with the exception of the Axis) no state around the world, including the Vatican, recognized the NDH as a sovereign nation, Stepinac publicly exhorted his hierarchy to pray for the Independent State of Croatia

, and publicly called for God to "fill the Ustaše

leader, Ante Pavelić

, with a spirit of wisdom for the benefit of the nation".

On more than one occasion, the archbishop professed his support for the Independent State of Croatia and welcomed the demise of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

, and continued to do so throughout the war. On April 10 each year during the war he celebrated a mass to celebrate proclamation of the Ustaše state. In his reports to the Vatican Stepinac spoke only favourably about the regime, and on March 28, 1941 he had made clear his own attitude to the problems of coexistence of the two peoples:

However, during the war on several occasions Stepinac criticized the Ustaše atrocities to certain leaders in private, but continued to give communion to Ustaše leaders and made no public comments about their activities, ignoring complaints about the atrocities and forced conversions, particularly those described to him in great detail by Bishop Alojzije Mišić

of Mostar

.

Upon hearing news of the Glina massacre

, on May 14, 1941 Stepinac sent a letter to Pavelić, requesting that "on the whole territory of the Independent State of Croatia, not one Serb is killed if he is not proven guilty for what he has deserved death." When hearing of the racial laws being enacted, he asked: "We...appeal to you to issue regulations so that even in the framework of antisemitic legislation, and similar legislation concerning Serbs, the principles of human dignity be preserved." On Sunday May 24, 1942 he condemned racial persecution in general terms, though he did not specifically mention Serbs

. He stated in a diocesan letter:

In a sermon on October 25, 1942, he further commentated on racial acceptance:

After the release of left-wing activist Ante Ciliga from Jasenovac in January 1943, Stepinac requested a meeting with him to learn about what was occurring at the camp. He also wrote directly to Pavelić, saying on 24 February 1943, "The Jasenovac camp itself is a shameful stain on the honor of the [Independent State of Croatia]."

Later Stepinac advised individual priests to admit Orthodox believers to the Catholic Church if their lives were in danger, such that this conversion had no validity, allowing them to return to their faith once the danger passed.

Stepinac was involved directly and indirectly in efforts to save Jews from persecution. Amiel Shomrony

, alias Emil Schwartz, was the personal secretary of Miroslav Šalom Freiberger

(the chief rabbi

in Zagreb

) until 1942. In the actions for saving Jews, Shomrony acted as the mediator between the chief rabbi and Stepinac. He later stated that he considered Stepinac "truly blessed" since he did the best he could for the Jews during the war. Allegedly the Ustaša government at this point agitated at the Holy See

for him to be removed from the position of archbishop of Zagreb, this however was refused due to the fact that the Vatican did not recognize the Ustaše state (despite Italian pressure). Stepinac and the papal nuncio to Belgrade

mediated with Royal Italian, Hungarian and Bulgarian troops, urging that the Yugoslav

Jews be allowed to take refuge in the occupied Balkan territories to avoid deportation. He also arranged for Jews to travel via these territories to the safe, neutral states of Turkey

and Spain, along with Istanbul

-based nuncio Angelo Roncalli

. He sent some Jews for safety to Rev. Dragutin Jeish, who was killed during the war by the Ustaše on suspicion of supporting the Partisans.

In 1942, officials from Hungary

lobbied to attach the Hungarian-occupied Međimurje ecclesiastically to a diocese in Hungary. Stepinac opposed this and received guarantees from the Holy See that diocesan boundaries would not change during the war. On October 26, 1943 the Germans killed the archbishop's brother Mijo Stepinac. In 1944, Stepinac received the Polish Pauline

priest Salezy Strzelec, who wrote about the archbishop, Zagreb, and Marija Bistrica upon his return to Poland.

The Catholic Church in Croatia has also had to contend with criticism of what some has seen as a passive stance towards the Ustaša policy of religious conversion

whereby some Serbs - but not the intelligentsia element - were able to escape other persecution by adopting the Catholic faith.

While Stepinac did suspend a number of priests, he only had the authority to do so within his own diocese; he had no power to suspend other priests or bishops outside of Zagreb.

After the war, on May 17, 1945, Stepinac was arrested. On June 2, Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito

After the war, on May 17, 1945, Stepinac was arrested. On June 2, Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito

met with representatives of the Archdiocese of Zagreb. The following day, he was released from custody. On June 4 Stepinac met with Tito but no agreement was reached between them. On June 22, the bishops of Croatia released a public letter accusing the Yugoslav authorities of injustices and crimes towards them. On June 28, Stepinac wrote a letter to the government of the Croatia asking for an end to the prosecution of Nazi collaborationists

(collaboration having been widespread in occupied Yugoslavia). On July 10, Stepinac's secretary Stjepan Lacković travelled to Rome. While he was there, the Yugoslav authorities forbade him to return. In August, a new land reform law was introduced which legalized the confiscation of 85 percent of church holdings in Yugoslavia.

During the same period the archbishop almost certainly had ties with the post-war Ustaše

(fascist) guerrillas, the "Crusaders", and actively worked against the state. From September 17 to 22 1945, a synod of the Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia

was held in Zagreb which discussed the confrontation with the government. On October 20 Stepinac published a letter in which he made the claim that "273 clergymen had been killed" since the Partisan take-over, "169 had been imprisoned", and another "89 were missing and presumed dead". Similar numbers were later published.

In response to this letter Tito spoke out publicly against Stepinac for the first time by writing an editorial on 25 October in the communist party's newspaper Borba accusing Stepinac of declaring war on the fledgling new Yugoslavia. Consequently on November 4 Stepinac had stones thrown at him by a crowd of Partisans in Zaprešić

. Tito had established "brotherhood and unity

" as the federation's over-arching objective and central policy, one which he did not want threatened by internal agitation. In addition, with the escalating Cold War conflict and increased concerns over both Western and Soviet infiltration (see Tito-Stalin split

), the Yugoslav government did not tolerate further internal subversion within the potentially fragile new federation.

In an effort to put a stop to the archbishop's activities, Tito attempted to reach an accord with Stepinac, and achieve a greater degree of independence for the Catholic Church in Yugoslavia and Croatia. Stepinac refused to break from the Vatican, and continued to publicly condemn the communist government. Tito, however, was reluctant to bring him to trial, in spite of condemning evidence which was available. Abandoning the strive towards increased Church independence, Tito first attempted to persuade Stepinac to cease his activities. When this too failed, in January 1946 the federal government attempted to solicit his replacement with the Vatican

, a request that was denied. Finally, Stepinac was himself asked to leave the country, which he refused. On September 1946 the Yugoslav authorities indicted Stepinac on multiple counts of war crimes and collaboration

with the enemy during wartime. Milovan Đilas, a prominent leader in the Party, stated that Stepinac would never have been brought to trial "had he not continued to oppose the new Communist regime."

with the occupation forces, relations with the Ustaše regime, having chaplains in the Ustaše army as religious agitators, forceful conversions of Serb Orthodox to Catholicism at gunpoint and high treason against the Yugoslav government. Stepinac was arrested on September 18, 1946 and his trial started on September 30, 1946, where he was tried alongside former officials of the Ustaše government including Erih Lisak (sentenced to death) and Ivan Šalić. Altogether there were 16 defendants.

The prosecution presented their evidence for the archbishop's collaboration with the Ustaše regime. Numerous witnesses were heard concerning the killings and forced conversions members of Aloysius Stepinac's military vicariate performed, explaining that "forced conversions" were more often than not followed by the slaughter of the new "converts" (which is the main cause of their infamy). In relation to these events the prosecution pointed out that even if the archbishop did not explicitly order them, he also did nothing to stop them or punish those within the church who were responsible. They also pointed out the disproportionate number of chaplains in the NDH armed forces and attempted to present in detail his relationship with the Ustaše authorities. The Vatican was not excluded of implication in these accusations.

On October 3, as part of the fourth day of the proceedings, Stepinac gave a lengthy 38-minute speech during which he laid down his views on the legitimacy of the trial. He claimed that the process was a "show trial", that he was being attacked in order for the state to attack the Church, and that "no religious conversions were done in bad faith". He went on to state that "My conscience is clear and calm. If you will not give me the right, history will give me that right", and that he did not intend to defend himself or appeal against a conviction, and that he is prepared to take ridicule, disdain, humiliation and death for his beliefs. He claimed that the military vicariate in the Independent State of Croatia was created to address the needs of the faithful among the soldiers and not for the army itself, nor as a sign of approval of all action by the army. He stated that he was never an Ustaša and that his Croatian nationalism stemmed from the nation's grievances in the Serb-dominated Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and that he never took part in any anti-government or terrorist activities against the state or against Serbs.

Stepinac also mentioned 260-270 priests were summarily executed by the Allied Yugoslav army for collaboration, which was widespread among the Catholic clergy in many parts of the NDH

, and that these summary death sentences "uncivilized". He also spoke against the nationalization of Church property and the newly implemented division of church and state (prevention of Church involvement in education, press, charitable work, and teaching of religion in school), as well as alleged intimidation and molestation of clergy. He also complained against atheism, spoke out against evolution

, materialism, and communism in general.

Stepinac was arrested on September 18, and was only given the indictment on the 23rd−meaning his defense were given only six to seven days to prepare. Stepinac's defense counsel were only allowed to call twenty witnesses—while the prosecution was allowed to call however many they pleased. The President of the Court refused to hear fourteen witnesses for the defense without giving any reason why.

On October 11, 1946, the court found Stepinac guilty of high treason

and war crimes. He was sentenced to 16 years in prison. He served five years in the prison at Lepoglava until he was released in a conciliatory gesture by Tito, on condition that he either retired to Rome or was confined to his home parish of Krašić. He chose to stay in Krašić, saying he would never leave "unless they put me on a plane by force and take me over the frontier."

atmosphere, and with the Vatican putting forward worldwide publicity, the trial was depicted in the West as a typical communist "show trial", in which the testimony was all false. The trial was immediately condemned by the Holy See. All Catholics who had taken part in the court proceedings, including most of the jury members, were excommunicated by Pope Pius XII

who referred to the process as the "saddest trial" (tristissimo processo).

In the United States, one of Stepinac's biggest supporters was the Archbishop of Boston, Richard Cushing, who delivered several sermons in support of him. U.S. Acting Secretary of State Dean Acheson

on October 11, 1946 bemoaned the conditions in Yugoslavia and stated his regret of the trial.

Support also came from the American Jewish Committee

, who put out a declaration that

On October 13, 1946, The New York Times

wrote that,

The National Conference of Christians and Jews at the Bronx Round Table adopted a unanimous resolution on October 13 condemning the trial:

In Britain

, on 23 October 1946, Mr Richard Stokes MP declared in the House of Commons that,

On November 1, 1946 Winston Churchill

addressed the House of Commons on the subject of the trial, expressing "great sadness" at the result.

In Stepinac's absence, archbishop of Belgrade

In Stepinac's absence, archbishop of Belgrade

Josip Ujčić became acting president of the Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia

, a position he held until Stepinac's death. In March 1947 the president of the People's Republic of Croatia Vladimir Bakarić

made an official visit to Lepoglava prison

to see Stepinac. He offered him to sign an amnesty plea to Yugoslavia's leader Josip Broz who would in turn allow Stepinac to leave the country. Instead, Stepinac gave Bakarić a request to Broz that he be retried by a neutral court. He also offered to explain his actions to the Croatian people on the largest square in Zagreb

. A positive response was not received from either request.

The 1947 pilgrimage to Marija Bistrica attracted 75,000 people. Dragutin Saili had been in charge of the pilgrimage on the part of the Yugoslav authorities. At a meeting of the Central Committee on August 1, 1947 Saili was chastised for allowing pictures of Stepinac to be carried during the pilgrimage, as long as the pictures were alongside those of Yugoslav leader Josip Broz. Marko Belinić responded to the report by saying, "Saili's path, his poor cooperation with the Local Committee, is a deadly thing".

In February, 1949, the United States House of Representatives

approved a resolution condemning Stepinac's imprisonment, with the Senate

following suit several months later. On November 11, 1951 Jewish-American Cyrus L. Sulzberger

from the New York Times visited Stepinac in Lepoglava. He won the Pulitzer Prize

for the interview. A visiting congressional delegation from the United States, including Clement J. Zablocki

and Edna F. Kelly

, pressed to see Stepinac in late November 1951. Their request was denied by the Yugoslav authorities, but Josip Broz Tito assured the delegation that Stepinac would be released within a month.

Aloysius Stepinac eventually served five years of his sixteen-year sentence for high treason

in the Lepoglava

prison, where he received preferred treatment in recognition of his clerical status. He was allocated two cells for personal use and an additional cell as his private chapel, while being exempt of all hard labor. Alojzije Stepinac was released in a conciliatory gesture by the Yugoslav Prime Minister Josip Broz Tito

, on the condition that he either retired to Rome or was confined to his home parish of Krašić. He refused to leave Yugoslavia and opted to live in Krašić, where he was transferred on December 5, 1951. He stated that: "They will never make me leave unless they put me on a plane by force and take me over the frontier. It is my duty in these difficult times to stay with the people."

At a meeting of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Croatia on October 5, 1951 Ivan Krajačić said, "In America they are printing the book Crvena ruža na oltaru of 350 pages, in which is described the entire Stepinac process. Religious education is particularly recently being taught on a large scale. We should do something about this. We could ban religious education. We could ban religious education in schools, but they will then pass it into their churches". On January 31, 1952 the Yugoslav authorities abolished religious education in state-run public schools, as part of the programme of separating church and state in Yugoslavia. In April, Stepinac told a journalist from Belgium's La Libertea, "I am greatly concerned about Catholic youth. In schools they are carrying out intensive communist propaganda, based on negating the truth".

, which coincided with Yugoslavia's Republic Day. Yugoslavia then severed diplomatic relations with the Vatican

on December 17, 1952. The government also expelled the Catholic Faculty of Theology from the University of Zagreb

, to which it was not restored until the first democratic elections were held in 1990, and was finally formalized in 1996.

Pius XII wrote to Stepinac and three other jailed prelates (Stefan Wyszyński, József Mindszenty and Josef Beran) on June 29, 1956 urging their supporters to remain loyal. Stepinac was unable to participate in the 1958 Papal conclave

due to his house arrest, despite calls from the Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia

for his release. On June 2, 1959 he wrote in a letter to Ivan Meštrović: "I likely will not live to see the collapse of communism in the world due to my poor health. But I am absolutely certain of that collapse."

The 1955 film The Prisoner

was loosely based on József Mindszenty and to some extent Stepinac. The Cardinal character, played by Alec Guinness

, was made to appear physically similar to Stepinac.

In 1953, Stepinac was diagnosed with polycythemia

In 1953, Stepinac was diagnosed with polycythemia

, a rare blood disorder involving the excess of red blood cells, causing him to joke "I am suffering from an excess of reds." On 10 February 1960 at the age of 61, Stepinac died of a thrombosis

. Pope John XXIII

held a requiem mass for him soon after at St. Peter's Basilica

. He was buried in Zagreb during a service in which the protocols appropriate to his senior clerical status were, with Tito's permission, fully observed. Cardinal Franz König

was among those who attended the funeral.

Notwithstanding that Stepinac died peacefully at home, he quickly became a martyr

in the view of his supporters and many other Catholics. After his death, traces of poison were found in Stepinac's bones, leading many to believe he had been poisoned by his captors.

When in 1943 Stepinac travelled to the Vatican, he came into contact with the Croatian artist Ivan Meštrović

. According to Meštrović, Stepinac asked him whether Croatian leader Ante Pavelić knew about crimes being committed in the state. When Meštrović replied that he must know everything, Stepinac reportedly broke into tears. Meštrović did not return to Yugoslavia until 1959 and upon his return met with Stepinac again, who was then under house arrest. Meštrović went on to sculpt a bust of Stepinac after his death which reads: "Archbishop Stepinac was not a man of idle words, but rather, he actively helped every person─when he was able, and to the extent he was able. He made no distinctions as to whether a man in need was a Croat or a Serb, whether he was a Catholic or an Orthodox, whether he was Christian or non-Christian. All the attacks upon him be they the product of misinformation, or the product of a clouded mind, cannot change this fact....".

In 1970, Glas Koncila

published a text on Stepinac taken from L'Osservatore Romano

which resulted in the edition being confiscated by court decree. Stepinac's beatification process began on October 9, 1981. The Catholic Church declared Stepinac a martyr on November 11, 1997, and on October 3, 1998 Pope John Paul II

declared that Stepinac had indeed been martyred while on pilgrimage to Marija Bistrica to beatify him. John Paul had earlier determined that where a candidate for sainthood had been martyred, his/her cause could be advanced without the normal requirement for evidence of a miraculous intercession by the candidate. Accordingly he beatified

the late cardinal after saying these words: One of the outstanding figures of the Catholic Church, having endured in his own body and his own spirit the atrocities of the Communist system, is now entrusted to the memory of his fellow countrymen with the radiant badge of martyrdom.

On the other hand many non-Catholics have remained unconvinced about Stepinac's martyrdom and about his saintly qualities in general. The beatification re-ignited old controversies between Catholicism and Communism and between Serbs and Croats. The Jewish community in Croatia, some members of which had been helped by Stepinac during World War II, did not oppose his beatification but the Simon Wiesenthal Center

asked for it to be deferred until the wartime conduct of Stepinac had been further investigated. The Vatican had no reaction, though some Croats expressed irritation.

On February 14, 1992, Croatian representative Vladimir Šeks

put forth a declaration in the Croatian Sabor condemning the court decision and the process that led to it. The declaration was passed, along with a similar one about the death of Croatian communist official Andrija Hebrang

. The declaration states that the true reason of Stepinac's imprisonment was his pointing out many communist crimes and especially refusing to form a Croatian Catholic Church in schism

with the Pope

. The verdict has not been formally challenged nor overturned in any court between 1997 and 1999 while it was possible under Croatian law. In 1998, the Croatian National Bank

released commemmoratives 500 kuna gold and 150 kuna silver coins.

In 2007, the municipality of Marija Bistrica began on a project called Stepinac's Path, which would build pilgrimage paths linking places significant to the cardinal: Krašić

, Kaptol

in Zagreb

, Medvednica

, Marija Bistrica, and Lepoglava

. The Aloysius Stepinac Museum opened in Zagreb in 2007.

Croatian football

international Dario Šimić

wore a t-shirt with Stepinac's image on it under his jersey during the country's UEFA Euro 2008 game against Poland, which he revealed after the game.

. Amiel Shomrony

(previously known in Croatia as Emil Schwarz), the secretary to the war-time head rabbi Miroslav Šalom Freiberger, nominated Stepinac in 1970. He was again nominated in 1994 by Igor Primorac. Amiel Shomrony has recently challenged the Serb lobby for preventing the inclusion of Stepinac into Yad Vashem's Righteous list. Esther Gitman

, a Jew from Sarajevo

living in the USA who holds a PhD on the subject of the fate of Jews in the Independent State of Croatia, said that Stepinac did much more for Jews than some want to admit. However the reason stated by Yad Vashem for denying the requests were that the proposers were not themselves Holocaust

survivors, which is a requirement for inclusion in the list; and that maintaining close links with a genocidal regime at the same time as making humanitarian interventions would preclude listing.

in the archives of the Federal Ministry of Justice, but only the extracts quoted by Jakov Blažević, the public prosecutor at Stepinac's trial, in his memoir Mač a ne Mir are available. Father Josip Vranković

kept a diary from December 1951 to February 10, 1960, recording what Stepinac related to him each day; that diary was used by Franciscan Aleksa Benigar to write a biography of Stepniac, but Benigar refused to share the diary with any other researcher. The diocesan archives have also been made available to Benigar, but no other researcher.

The official transcript of Stepinac's trial Sudjenje Lisaku, Stepincu etc. was published in Zagreb in 1946, but contains substantial evidence of alteration. Alexander's Triple Myth therefore relies on the Yugoslav and foreign press—particularly Vjesnik

and Narodne Novine

—as well as Katolički List. All other primary sources available to researchers only indirectly focus on Stepinac.

Croats

Croats are a South Slavic ethnic group mostly living in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and nearby countries. There are around 4 million Croats living inside Croatia and up to 4.5 million throughout the rest of the world. Responding to political, social and economic pressure, many Croats have...

Catholic cardinal and Archbishop of Zagreb from 1937 to 1960. In 1998 he was declared a martyr

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

and beatified

Beatification

Beatification is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a dead person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in his or her name . Beatification is the third of the four steps in the canonization process...

by Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II

Blessed Pope John Paul II , born Karol Józef Wojtyła , reigned as Pope of the Catholic Church and Sovereign of Vatican City from 16 October 1978 until his death on 2 April 2005, at of age. His was the second-longest documented pontificate, which lasted ; only Pope Pius IX ...

.

Stepinac was ordained on October 26, 1930 by archbishop Giuseppe Palica

Giuseppe Palica

Giuseppe Palica was an italian Archbishop.Born on 8 October 1869 in Rome, he was ordained priest on 18 December 1892.On 25 April 1917 he was appointed vice-gerent of Rome and titular archbishop of Philippi....

, and in 1931 he became a parish curate in Zagreb

Zagreb

Zagreb is the capital and the largest city of the Republic of Croatia. It is in the northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the Medvednica mountain. Zagreb lies at an elevation of approximately above sea level. According to the last official census, Zagreb's city...

. He established the archdiocesan branch of Caritas

Caritas (charity)

Caritas Internationalis is a confederate of 164 Roman Catholic relief, development and social service organisations operating in over 200 countries and territories worldwide....

in 1931, and was appointed coadjutor to the see of Zagreb in 1934. When Archbishop Anton Bauer died on December 7, 1937, Stepinac succeeded him as the Archbishop of Zagreb. During World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, on 6 April 1941, Yugoslavia

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a state stretching from the Western Balkans to Central Europe which existed during the often-tumultuous interwar era of 1918–1941...

was invaded by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

, who established the Ustaše

Ustaše

The Ustaša - Croatian Revolutionary Movement was a Croatian fascist anti-Yugoslav separatist movement. The ideology of the movement was a blend of fascism, Nazism, and Croatian nationalism. The Ustaše supported the creation of a Greater Croatia that would span to the River Drina and to the border...

-led Independent State of Croatia

Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia was a World War II puppet state of Nazi Germany, established on a part of Axis-occupied Yugoslavia. The NDH was founded on 10 April 1941, after the invasion of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers. All of Bosnia and Herzegovina was annexed to NDH, together with some parts...

. As archbishop of the puppet state's capital, Stepinac had close associations with the Ustaše leaders during the Nazi occupation, had issued proclamations celebrating the NDH, and welcomed the Ustaše leaders. Stepinac also objected against the persecution of Jews and Nazi laws, helped Jews and others to escape and criticized Ustaše atrocities in front of Zagreb Cathedral

Zagreb cathedral

Zagreb Cathedral on Kaptol is the most famous building in Zagreb, and the tallest building in Croatia. It is dedicated to the Holy Virgin's Ascension and to St. Stephen and St. Ladislaus. The cathedral is typically Gothic, as is its sacristy, which is of great architectonic value...

in 1943.

After the war he publicly condemned the new Yugoslav government and its actions during World War II, especially for murders of priests by Communist militants. Yugoslav authorities indicted the archbishop on multiple counts of war crimes and collaboration

Collaborationism

Collaborationism is cooperation with enemy forces against one's country. Legally, it may be considered as a form of treason. Collaborationism may be associated with criminal deeds in the service of the occupying power, which may include complicity with the occupying power in murder, persecutions,...

with the enemy during wartime. The trial was depicted in the West as a typical communist "show trial", biased against the archbishop; however, some claim the trial was "carried out with proper legal procedure". In a verdict that polarized public opinion both in Yugoslavia and beyond, the Yugoslav authorities found him guilty of collaboration

Collaborationism

Collaborationism is cooperation with enemy forces against one's country. Legally, it may be considered as a form of treason. Collaborationism may be associated with criminal deeds in the service of the occupying power, which may include complicity with the occupying power in murder, persecutions,...

with the fascist

Fascism

Fascism is a radical authoritarian nationalist political ideology. Fascists seek to rejuvenate their nation based on commitment to the national community as an organic entity, in which individuals are bound together in national identity by suprapersonal connections of ancestry, culture, and blood...

Ustaše movement and complicity in allowing the forced conversions of Orthodox

Serbian Orthodox Church

The Serbian Orthodox Church is one of the autocephalous Orthodox Christian churches, ranking sixth in order of seniority after Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Russia...

Serbs

Serbs

The Serbs are a South Slavic ethnic group of the Balkans and southern Central Europe. Serbs are located mainly in Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and form a sizable minority in Croatia, the Republic of Macedonia and Slovenia. Likewise, Serbs are an officially recognized minority in...

to Catholicism

Catholicism

Catholicism is a broad term for the body of the Catholic faith, its theologies and doctrines, its liturgical, ethical, spiritual, and behavioral characteristics, as well as a religious people as a whole....

.

After foreign and domestic pressure, Stepinac was released from Lepoglava prison

Lepoglava prison

Lepoglava prison is the oldest prison in Croatia. It is located in Lepoglava, Varaždin County, northern Croatia, southwest of Varaždin prison.-History:...

. In 1952 he was appointed cardinal by Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII

The Venerable Pope Pius XII , born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli , reigned as Pope, head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of Vatican City State, from 2 March 1939 until his death in 1958....

. Stepinac died while still under confinement in his parish, almost certainly as the result of poisoning by his Communist captors. In October 3, 1998, Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II

Blessed Pope John Paul II , born Karol Józef Wojtyła , reigned as Pope of the Catholic Church and Sovereign of Vatican City from 16 October 1978 until his death on 2 April 2005, at of age. His was the second-longest documented pontificate, which lasted ; only Pope Pius IX ...

declared him a martyr

Martyr

A martyr is somebody who suffers persecution and death for refusing to renounce, or accept, a belief or cause, usually religious.-Meaning:...

and beatified

Beatification

Beatification is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a dead person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in his or her name . Beatification is the third of the four steps in the canonization process...

him before 500,000 Croatians in Marija Bistrica

Marija Bistrica

Marija Bistrica is municipality in Krapina-Zagorje County in central Croatia, located on the slopes of the Medvednica mountain in Hrvatsko Zagorje, not far away from Zagreb...

near Zagreb. This again polarized public opinion.

Early life

Stepinac was born in the village of Brezarić in the parish of Krašić on 8 May 1898 to Josip Stepinac and his wife Barbara. He was the fifth of eight children in his peasant family. In 1909 he moved to ZagrebZagreb

Zagreb is the capital and the largest city of the Republic of Croatia. It is in the northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the Medvednica mountain. Zagreb lies at an elevation of approximately above sea level. According to the last official census, Zagreb's city...

to study in the Classical Gymnasium

Classical Gymnasium in Zagreb

The Classical Gymnasium in Zagreb is the home of the oldest high schools in Croatia and southeastern Europe. It was founded by the Society of Jesus in 1607 and hasn't stopped working since...

and graduated in 1916. Just before his eighteenth birthday he was conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian Army

Austro-Hungarian Army

The Austro-Hungarian Army was the ground force of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy from 1867 to 1918. It was composed of three parts: the joint army , the Austrian Landwehr , and the Hungarian Honvédség .In the wake of fighting between the...

. He was attached to the 96th Karlovac Infantry Regiment before going to Rijeka

Rijeka

Rijeka is the principal seaport and the third largest city in Croatia . It is located on Kvarner Bay, an inlet of the Adriatic Sea and has a population of 128,735 inhabitants...

for six months training. He was then sent to serve on the Italian Front

Italian Campaign (World War I)

The Italian campaign refers to a series of battles fought between the armies of Austria-Hungary and Italy, along with their allies, in northern Italy between 1915 and 1918. Italy hoped that by joining the countries of the Triple Entente against the Central Powers it would gain Cisalpine Tyrol , the...

during World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. In July 1918 he was captured by the Italians who held him as a prisoner of war for five months. After the formation of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs was a short-lived state formed from the southernmost parts of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy after its dissolution at the end of the World War I by the resident population of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs...

, he was no longer treated as an enemy soldier, and he instead volunteered for the Yugoslav legion that was engaged on the Salonika Front. A few months later, he was demobilized with the rank of Second Lieutenant

Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces.- United Kingdom and Commonwealth :The rank second lieutenant was introduced throughout the British Army in 1871 to replace the rank of ensign , although it had long been used in the Royal Artillery, Royal...

and returned home in the spring of 1919.

For service in the Yugoslav forces during World War I, he was awarded the Order of the Star of Karađorđe, an award for heroism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a state stretching from the Western Balkans to Central Europe which existed during the often-tumultuous interwar era of 1918–1941...

. After the war he enrolled at the faculty of agronomy of the University of Zagreb

University of Zagreb

The University of Zagreb is the biggest Croatian university and the oldest continuously operating university in the area covering Central Europe south of Vienna and all of Southeastern Europe...

, but left it after only one semester and returned home to help his father. In 1922 Stepinac was part of the Croatian Eagles Association

Sokol

The Sokol movement is a youth sport movement and gymnastics organization first founded in Czech region of Austria-Hungary, Prague, in 1862 by Miroslav Tyrš and Jindřich Fügner...

and traveled to the Catholic Eagle slet

Mass games

Mass games or mass gymnastics are a form of performing arts or gymnastics in which large numbers of performers take part in a highly regimented performance that emphasizes group dynamics rather than individual prowess.-Methods:...

in Brno

Brno

Brno by population and area is the second largest city in the Czech Republic, the largest Moravian city, and the historical capital city of the Margraviate of Moravia. Brno is the administrative centre of the South Moravian Region where it forms a separate district Brno-City District...

, Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

. He was at the front of the group's ceremonial procession, carrying a Croatian flag. In 1924, he traveled to Rome to study for the priesthood at the Collegium Germanicum et Hungaricum

Collegium Germanicum et Hungaricum

The Collegium Germanicum et Hungaricum or simply Collegium Germanicum is a German-speaking seminary for Roman Catholic priests in Rome, founded in 1552. Since 1580 its full name has been Pontificium Collegium Germanicum et Hungaricum de Urbe....

. During his studies there he befriended the future cardinal Franz König when the two played together on the same volleyball team. He was ordained on October 26, 1930 by archbishop Giuseppe Palica

Giuseppe Palica

Giuseppe Palica was an italian Archbishop.Born on 8 October 1869 in Rome, he was ordained priest on 18 December 1892.On 25 April 1917 he was appointed vice-gerent of Rome and titular archbishop of Philippi....

in a ceremony which also included Franjo Šeper

Franjo Šeper

Franjo Šeper was a Croatian Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. He served as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith from 1968 to 1981, and was elevated to the cardinalate in 1965....

. On November 1, he said his first mass at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore

Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore

The Papal Basilica of Saint Mary Major , known also by other names, is the largest Roman Catholic Marian church in Rome, Italy.There are other churches in Rome dedicated to Mary, such as Santa Maria in Trastevere, Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Santa Maria sopra Minerva, but the greater size of the...

. In 1931 he became a parish curate in Zagreb

Zagreb

Zagreb is the capital and the largest city of the Republic of Croatia. It is in the northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the Medvednica mountain. Zagreb lies at an elevation of approximately above sea level. According to the last official census, Zagreb's city...

. He established the archdiocesan branch of Caritas

Caritas (charity)

Caritas Internationalis is a confederate of 164 Roman Catholic relief, development and social service organisations operating in over 200 countries and territories worldwide....

in 1931.

Pre-war Coadjutor and Archbishop of Zagreb

He was appointed coadjutor to the see of Zagreb in 1934, after other candidates had been rejected by Pope Pius XIPope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI , born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, was Pope from 6 February 1922, and sovereign of Vatican City from its creation as an independent state on 11 February 1929 until his death on 10 February 1939...

because king Alexander I of Yugoslavia

Alexander I of Yugoslavia

Alexander I , also known as Alexander the Unifier was the first king of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia as well as the last king of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes .-Childhood:...

needed to agree with the appointment. Upon his naming, he took In te, Domine, speravi (O Lord, in Thee have I trusted) as his motto. During this period, King Alexander ran a dictatorship in the country. Stepinac was among those who signed the Zagreb memorandum demanding from the king the release of Vladko Maček

Vladko Macek

Vladko Maček was a Croatian politician active within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the first half of the 20th century. He led the Croatian Peasant Party following the assassination of Stjepan Radić, and all through World War II.- Early life :Maček was born to a Slovene-Czech family in the village...

and other Croatian politicians, as well as a general amnesty. Stepinac was denied access by Yugoslav authorities to see Maček to thank him for his well-wishes concerning Stepinac's appointment as coadjutor.

King Alexander was assassinated in Marseilles in 1934, and Stepinac along with Bishops Antun Akšamović, Dionizije Njaradi and Gregorij Rožman

Gregorij Rožman

Gregorij Rožman was a Slovenian Roman Catholic clergyman and theologian. Between 1930 and 1959, he served as bishop of the Diocese of Ljubljana. He is most famous for his controversial role during World War II...

were given special permission from the Holy See

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

to attend the funeral in an Orthodox church. Croatian politician Ante Trumbić

Ante Trumbic

Ante Trumbić was a Croatian politician in the early 20th century. He was one of the key politicians in the creation of a Yugoslav state....

spoke to Stepinac on several occasions in 1934. On his relation with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a state stretching from the Western Balkans to Central Europe which existed during the often-tumultuous interwar era of 1918–1941...

, he recorded that Stepinac has "loyalty to the state as it is, but with the condition that the state acts towards the Catholic Church as it does to all just denominations and that it guarantees them freedom". On July 30 he received French deputy Robert Schuman

Robert Schuman

Robert Schuman was a noted Luxembourgish-born French statesman. Schuman was a Christian Democrat and an independent political thinker and activist...

, whom he told: "There is no justice in Yugoslavia. [...] The Catholic Church endures much".

In 1936, he climbed the Mount Triglav

Triglav

Triglav is the highest mountain in Slovenia and the highest peak of the Julian Alps. While its name, meaning "three-headed", can describe its shape as seen from the Bohinj area, the mountain was most probably named after the Slavic god Triglav. The mountain is the preeminent symbol of the Slovene...

, the tallest peak in Yugoslavia

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a state stretching from the Western Balkans to Central Europe which existed during the often-tumultuous interwar era of 1918–1941...

. In 2006 this climb was commemorated by a memorial chapel being built near the summit. In 1937 he led a pilgrimage to the Holy Land

Holy Land

The Holy Land is a term which in Judaism refers to the Kingdom of Israel as defined in the Tanakh. For Jews, the Land's identifiction of being Holy is defined in Judaism by its differentiation from other lands by virtue of the practice of Judaism often possible only in the Land of Israel...

(then the British Mandate of Palestine). During the pilgrimage he blessed an altar dedicated to the martyr Nikola Tavelić

Nikola Tavelic

Nikola Tavelić is a saint of the Catholic Church. This Franciscan missionary, who died a martyr's death in Jerusalem, was the first Croatian saint.- Life :...

(who was beatified then, but later canonized).

On December 7, 1937 Archbishop Anton Bauer died, and though still below the age of forty. Stepinac succeeded him as the Archbishop of Zagreb. During Lent

Lent

In the Christian tradition, Lent is the period of the liturgical year from Ash Wednesday to Easter. The traditional purpose of Lent is the preparation of the believer – through prayer, repentance, almsgiving and self-denial – for the annual commemoration during Holy Week of the Death and...

in 1938, Stepinac told a group of students from the University of Zagreb

University of Zagreb

The University of Zagreb is the biggest Croatian university and the oldest continuously operating university in the area covering Central Europe south of Vienna and all of Southeastern Europe...

: "Love towards one's own nation cannot turn a man into a wild animal, which destroys everything and calls for reprisal, but it must ennoble him, so that his own nation secures respect and love for other nations." In 1938, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia held its last election before the outbreak of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. Stepinac voted for Vlatko Maček's opposition list, while Radio Belgrade

Radio Belgrade

Radio Belgrade is a state-owned and operated radio station in Belgrade, Serbia.The predecessor of Radio Beograd, Radio Beograd-Rakovica, started its program in 1924 and was a part of a state wireless telegraph station. Radio Beograd, AD started in March 1929...

spread the false information that he had voted for Milan Stojadinović

Milan Stojadinovic

Milan Stojadinović was a Yugoslav political figure and a noted economist.Stojadinović was born in Čačak in central Serbia, and went to school in Užice and Kragujevac. In 1910 he graduated from the University of Belgrade's Law School, and gained a Ph.D. in economics in 1911...

's Yugoslav Radical Union

Yugoslav Radical Union

The Yugoslav Radical Union was a conservative political party in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.The party was formed by the Serbian politician Milan Stojadinović in 1935. It was made up by different groups, that could be divided in three parts: in Serbia, it was made mostly by former members of the...

. In the latter half of 1938, Stepinac had an operation for acute appendicitis.

In response to growing tensions in Europe, in 1936 Stepinac helped sponsor a committee aiding Jewish refuges from Austria and Germany. Then in April 1939 Dr. Dragutin Hren spoke to Stepinac about a group of Croatian Discalced Carmelite nuns from Mayerling

Mayerling

Mayerling is a small village in Lower Austria belonging to the municipality of Alland in the district of Baden. It is situated on the Schwechat River, in the Wienerwald , 15 miles southwest of Vienna...

who were being pressured by the German Nazis. Stepinac decided to accept the group and place them at a mansion in Brezovica

Brezovica, Zagreb

Brezovica is a city district of Zagreb, Croatia. It is located in the southwestern part of the city and has 12,040 inhabitants . It is one of the more rural districts in Zagreb...

. Stepinac spent October 6, 1939 in Ivanić-Grad where he administered confirmation for the local parish. In 1940, he received Prince Paul

Prince Paul of Yugoslavia

Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, also known as Paul Karađorđević , was Regent of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia during the minority of King Peter II. Peter was the eldest son of his first cousin Alexander I...

at St. Mark's Church

St. Mark's Church, Zagreb

Church of St. Mark is the parish church of old Zagreb.-Overview:The Romanesque window found in its south facade is the best evidence that the church must have been built as early as the 13th century as is also the semicircular groundplan of St...

as the prince arrived in Zagreb to curry support for the Cvetković-Maček Agreement

Cvetkovic-Macek Agreement

The Cvetković-Maček Agreement was a political agreement on the internal divisions in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia which was settled on August 23, 1939 by Yugoslav prime minister Dragiša Cvetković and Vladko Maček, a Croat politician...

. Under Stepinac, Pope Pius XII declared 1940 as a Jubilee

Jubilee (Christian)

The concept of the Jubilee is a special year of remission of sins and universal pardon. In the Biblical Book of Leviticus, a Jubilee year is mentioned to occur every fifty years, in which slaves and prisoners would be freed, debts would be forgiven and the mercies of God would be particularly...

year for Croats

Croats

Croats are a South Slavic ethnic group mostly living in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and nearby countries. There are around 4 million Croats living inside Croatia and up to 4.5 million throughout the rest of the world. Responding to political, social and economic pressure, many Croats have...

to celebrate 1300 years of Christianity among the Croats. In 1940, the Franciscan Order celebrated 700 years in Croatia and the order's minister general Leonardo Bello came to Zagreb for the event. During his visit Stepinac joined the Franciscan Third Order, on September 29, 1940.

World War II

During World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, on 6 April 1941, Yugoslavia

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a state stretching from the Western Balkans to Central Europe which existed during the often-tumultuous interwar era of 1918–1941...

was invaded by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and its allies. The (Allied

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

) Yugoslav forces maintained a defence up until 17 April. On 10 April 1941, the Wehrmacht occupied Zagreb

Zagreb

Zagreb is the capital and the largest city of the Republic of Croatia. It is in the northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the Medvednica mountain. Zagreb lies at an elevation of approximately above sea level. According to the last official census, Zagreb's city...

. Having previously agreed to form a Croatian satellite, the Germans and Italians established therein the Independent State of Croatia

Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia was a World War II puppet state of Nazi Germany, established on a part of Axis-occupied Yugoslavia. The NDH was founded on 10 April 1941, after the invasion of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers. All of Bosnia and Herzegovina was annexed to NDH, together with some parts...

, and installed the Ustaše movement into power. Fiercely nationalistic, the Ustaše were also fanatically Catholic. In the Yugoslav political context, they identified Catholicism with Croatian nationalism and, once established in power, set about persecuting and murdering non-Catholics."Fiercely nationalistic, the Ustaše were also fanatically Catholic. In the Yugoslav political context, they identified Catholicism with Croatian nationalism and, once established in power, set about persecuting and murdering non-Catholics."

As the archbishop of the capital, Stepinac enjoyed close associations with the Ustaše leaders. When the Ustaše arrived, following the capitulation of Allied Yugoslavia, he publicly welcomed their arrival and issued proclamations celebrating the NDH. Among other such occasions, on April 21, 1941 the Catholic newspaper Katolički List, over which Stepinac had full control as president of the bishops' conference, reported that he had welcomed Ustaše leaders in meetings on April 12 and 16. With the Yugoslav army still fighting the invaders, this was high treason

High treason

High treason is criminal disloyalty to one's government. Participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplomats, or its secret services for a hostile and foreign power, or attempting to kill its head of state are perhaps...

and constituted collaboration

Collaborationism

Collaborationism is cooperation with enemy forces against one's country. Legally, it may be considered as a form of treason. Collaborationism may be associated with criminal deeds in the service of the occupying power, which may include complicity with the occupying power in murder, persecutions,...

with the enemy. It meant Stepinac, a Yugoslav citizen, had breached the oath of allegiance he had given his King when appointed coadjutor. Even though (with the exception of the Axis) no state around the world, including the Vatican, recognized the NDH as a sovereign nation, Stepinac publicly exhorted his hierarchy to pray for the Independent State of Croatia

Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia was a World War II puppet state of Nazi Germany, established on a part of Axis-occupied Yugoslavia. The NDH was founded on 10 April 1941, after the invasion of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers. All of Bosnia and Herzegovina was annexed to NDH, together with some parts...

, and publicly called for God to "fill the Ustaše

Ustaše

The Ustaša - Croatian Revolutionary Movement was a Croatian fascist anti-Yugoslav separatist movement. The ideology of the movement was a blend of fascism, Nazism, and Croatian nationalism. The Ustaše supported the creation of a Greater Croatia that would span to the River Drina and to the border...

leader, Ante Pavelić

Ante Pavelic

Ante Pavelić was a Croatian fascist leader, revolutionary, and politician. He ruled as Poglavnik or head, of the Independent State of Croatia , a World War II puppet state of Nazi Germany in Axis-occupied Yugoslavia...

, with a spirit of wisdom for the benefit of the nation".

On more than one occasion, the archbishop professed his support for the Independent State of Croatia and welcomed the demise of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a state stretching from the Western Balkans to Central Europe which existed during the often-tumultuous interwar era of 1918–1941...

, and continued to do so throughout the war. On April 10 each year during the war he celebrated a mass to celebrate proclamation of the Ustaše state. In his reports to the Vatican Stepinac spoke only favourably about the regime, and on March 28, 1941 he had made clear his own attitude to the problems of coexistence of the two peoples:

All in all, Croats and Serbs are of two worlds, north pole and south pole, never will they be able to get together unless by a miracle of God. The SchismEast-West SchismThe East–West Schism of 1054, sometimes known as the Great Schism, formally divided the State church of the Roman Empire into Eastern and Western branches, which later became known as the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church, respectively...

is the greatest curse in Europe, almost greater than Protestantism. Here there is no moral, no principles, no truth, no justice, no honesty.

However, during the war on several occasions Stepinac criticized the Ustaše atrocities to certain leaders in private, but continued to give communion to Ustaše leaders and made no public comments about their activities, ignoring complaints about the atrocities and forced conversions, particularly those described to him in great detail by Bishop Alojzije Mišić

Alojzije Mišic

Alojzije Mišić was the Bishop of Mostar-Duvno and Apostolic Administrator of Trebinje-Mrkan from 1912 to 1942....

of Mostar

Mostar

Mostar is a city and municipality in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the largest and one of the most important cities in the Herzegovina region and the center of the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton of the Federation. Mostar is situated on the Neretva river and is the fifth-largest city in the country...

.

Upon hearing news of the Glina massacre

Glina massacre

The Glina massacre was the August 1941 killing of hundreds of Serbs by members of the Croatian fascist Ustaše movement in the town of Glina in Croatia. It was one of the largest single acts of mass murder to occur in Yugoslavia during the Second World War....

, on May 14, 1941 Stepinac sent a letter to Pavelić, requesting that "on the whole territory of the Independent State of Croatia, not one Serb is killed if he is not proven guilty for what he has deserved death." When hearing of the racial laws being enacted, he asked: "We...appeal to you to issue regulations so that even in the framework of antisemitic legislation, and similar legislation concerning Serbs, the principles of human dignity be preserved." On Sunday May 24, 1942 he condemned racial persecution in general terms, though he did not specifically mention Serbs

Serbs

The Serbs are a South Slavic ethnic group of the Balkans and southern Central Europe. Serbs are located mainly in Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and form a sizable minority in Croatia, the Republic of Macedonia and Slovenia. Likewise, Serbs are an officially recognized minority in...

. He stated in a diocesan letter:

All men and all races are children of God; all without distinction. Those who are Gypsies, Black, European, or Aryan all have the same rights (...) for this reason, the Catholic Church had always condemned, and continues to condemn, all injustice and all violence committed in the name of theories of class, race, or nationality. It is not permissible to persecute Gypsies or Jews because they are thought to be an inferior race.

In a sermon on October 25, 1942, he further commentated on racial acceptance:

We affirm then that all peoples and races descend from God. In fact, there exists but one race...The members of this race can be white or black, they can be separated by oceans or live on the opposing poles, [but] they remain first and foremost the race created by God, according to the precepts of natural law and positive Divine law as it is written in the hearts and minds of humans or revealed by Jesus Christ, the son of God, the sovereign of all peoples.

After the release of left-wing activist Ante Ciliga from Jasenovac in January 1943, Stepinac requested a meeting with him to learn about what was occurring at the camp. He also wrote directly to Pavelić, saying on 24 February 1943, "The Jasenovac camp itself is a shameful stain on the honor of the [Independent State of Croatia]."

Later Stepinac advised individual priests to admit Orthodox believers to the Catholic Church if their lives were in danger, such that this conversion had no validity, allowing them to return to their faith once the danger passed.

Stepinac was involved directly and indirectly in efforts to save Jews from persecution. Amiel Shomrony

Amiel Shomrony

Amiel Shomrony was a Croatian Jew who survived the Holocaust as the secretary of Zagreb's chief rabbi Miroslav Šalom Freiberger during the World War II....

, alias Emil Schwartz, was the personal secretary of Miroslav Šalom Freiberger

Miroslav Šalom Freiberger

Miroslav Šalom Freiberger was chief rabbi of Zagreb and a catechist, translator, writer and spiritual leader. He was educated as a lawyer and doctor of theology.-Biography:...

(the chief rabbi

Rabbi

In Judaism, a rabbi is a teacher of Torah. This title derives from the Hebrew word רבי , meaning "My Master" , which is the way a student would address a master of Torah...

in Zagreb

Zagreb

Zagreb is the capital and the largest city of the Republic of Croatia. It is in the northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the Medvednica mountain. Zagreb lies at an elevation of approximately above sea level. According to the last official census, Zagreb's city...

) until 1942. In the actions for saving Jews, Shomrony acted as the mediator between the chief rabbi and Stepinac. He later stated that he considered Stepinac "truly blessed" since he did the best he could for the Jews during the war. Allegedly the Ustaša government at this point agitated at the Holy See

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

for him to be removed from the position of archbishop of Zagreb, this however was refused due to the fact that the Vatican did not recognize the Ustaše state (despite Italian pressure). Stepinac and the papal nuncio to Belgrade

Belgrade

Belgrade is the capital and largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers, where the Pannonian Plain meets the Balkans. According to official results of Census 2011, the city has a population of 1,639,121. It is one of the 15 largest cities in Europe...

mediated with Royal Italian, Hungarian and Bulgarian troops, urging that the Yugoslav

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a state stretching from the Western Balkans to Central Europe which existed during the often-tumultuous interwar era of 1918–1941...

Jews be allowed to take refuge in the occupied Balkan territories to avoid deportation. He also arranged for Jews to travel via these territories to the safe, neutral states of Turkey

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

and Spain, along with Istanbul

Istanbul

Istanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

-based nuncio Angelo Roncalli

Pope John XXIII

-Papal election:Following the death of Pope Pius XII in 1958, Roncalli was elected Pope, to his great surprise. He had even arrived in the Vatican with a return train ticket to Venice. Many had considered Giovanni Battista Montini, Archbishop of Milan, a possible candidate, but, although archbishop...

. He sent some Jews for safety to Rev. Dragutin Jeish, who was killed during the war by the Ustaše on suspicion of supporting the Partisans.

In 1942, officials from Hungary

Kingdom of Hungary (1920–1946)

The Kingdom of Hungary also known as the Regency, existed from 1920 to 1946 and was a de facto country under Regent Miklós Horthy. Horthy officially represented the abdicated Hungarian monarchy of Charles IV, Apostolic King of Hungary...

lobbied to attach the Hungarian-occupied Međimurje ecclesiastically to a diocese in Hungary. Stepinac opposed this and received guarantees from the Holy See that diocesan boundaries would not change during the war. On October 26, 1943 the Germans killed the archbishop's brother Mijo Stepinac. In 1944, Stepinac received the Polish Pauline

The Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit

The Pauline Fathers a Hungarian order of the Roman Catholic Church, are more formally known as The Order of Saint Paul the First Hermit .This name is derived from the hermit Saint Paul of Thebes , canonized in 491 by Pope Gelasius I...

priest Salezy Strzelec, who wrote about the archbishop, Zagreb, and Marija Bistrica upon his return to Poland.

The Catholic Church in Croatia has also had to contend with criticism of what some has seen as a passive stance towards the Ustaša policy of religious conversion

Religious conversion

Religious conversion is the adoption of a new religion that differs from the convert's previous religion. Changing from one denomination to another within the same religion is usually described as reaffiliation rather than conversion.People convert to a different religion for various reasons,...

whereby some Serbs - but not the intelligentsia element - were able to escape other persecution by adopting the Catholic faith.

While Stepinac did suspend a number of priests, he only had the authority to do so within his own diocese; he had no power to suspend other priests or bishops outside of Zagreb.

Post-war period

Josip Broz Tito

Marshal Josip Broz Tito – 4 May 1980) was a Yugoslav revolutionary and statesman. While his presidency has been criticized as authoritarian, Tito was a popular public figure both in Yugoslavia and abroad, viewed as a unifying symbol for the nations of the Yugoslav federation...

met with representatives of the Archdiocese of Zagreb. The following day, he was released from custody. On June 4 Stepinac met with Tito but no agreement was reached between them. On June 22, the bishops of Croatia released a public letter accusing the Yugoslav authorities of injustices and crimes towards them. On June 28, Stepinac wrote a letter to the government of the Croatia asking for an end to the prosecution of Nazi collaborationists

Collaborationism

Collaborationism is cooperation with enemy forces against one's country. Legally, it may be considered as a form of treason. Collaborationism may be associated with criminal deeds in the service of the occupying power, which may include complicity with the occupying power in murder, persecutions,...

(collaboration having been widespread in occupied Yugoslavia). On July 10, Stepinac's secretary Stjepan Lacković travelled to Rome. While he was there, the Yugoslav authorities forbade him to return. In August, a new land reform law was introduced which legalized the confiscation of 85 percent of church holdings in Yugoslavia.

During the same period the archbishop almost certainly had ties with the post-war Ustaše

Ustaše

The Ustaša - Croatian Revolutionary Movement was a Croatian fascist anti-Yugoslav separatist movement. The ideology of the movement was a blend of fascism, Nazism, and Croatian nationalism. The Ustaše supported the creation of a Greater Croatia that would span to the River Drina and to the border...

(fascist) guerrillas, the "Crusaders", and actively worked against the state. From September 17 to 22 1945, a synod of the Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia

Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia

The Bishops' Conference of Yugoslavia was an episcopal conference of the Catholic Church covering the territory of Yugoslavia.The first such bishops' conference was held in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in November of 1918...

was held in Zagreb which discussed the confrontation with the government. On October 20 Stepinac published a letter in which he made the claim that "273 clergymen had been killed" since the Partisan take-over, "169 had been imprisoned", and another "89 were missing and presumed dead". Similar numbers were later published.