Carrier language

Encyclopedia

The Carrier language is a Northern Athabaskan language. It is named after the Dakelh

people, a First Nations

people of the Central Interior of British Columbia

, Canada

, for whom Carrier is the usual English name. People who are referred to as Carrier speak two related languages. One, Babine-Witsuwit'en

is sometimes referred to as Northern Carrier. The other, Carrier proper, includes what are sometimes referred to as Central Carrier and Southern Carrier.

There are three series of stops and affricates: aspirated, unaspirated (written voiced in the practical orthography), and ejective.

/r/ is not native to the language but has been introduced by loans from French and English. /f/ occurs in a single loanword "coffee". The labialized voiced velar fricative /ɣʷ/ is found only in the speech of the most conservative speakers; for most speakers it has merged with /w/. The palatal nasal /ɲ/ occurs allophonically before other palatal consonants; otherwise, it occurs only in a small set of 2nd-person singular

morphemes. For most speakers it has become an [n̩j] sequence, with a syllabic [n]. Similarly, the velar nasal /ŋ/ occurs allophonically before other velar consonants but is found distinctively in one or two morphemes in each dialect.

Carrier once had a dental/alveolar (or laminal

/apical

) distinction, attested in the earliest grammatical treatise of the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. However, by 1976 this had been leveled to the present alveolar series among younger speakers, and in 1981 the dental/laminal series (marked by underlining the consonant) was said to be found in only the "very oldest speakers". Poser (2005) states that it is found in only the most conservative speech. In even the earliest description, there is evidence of the distinction being neutralized.

. Unlike in some related languages, there is no distinctive nasalization; that is, Carrier does not contrast oral and nasal vowel

s.

The great majority of instances of /ə/ are predictable from the phonotactics, introduced in order to create an acceptable syllable structure. The remaining instances are all found in certain forms of the verb where the morphology requires some vowel to be present.

In most if not all dialects there are surface-phonemic distinctions of vowel length

. However, all of the long vowels that create such distinctions are morphophonemically derived. There is no need to represent vowel length in lexical representations.

system of the type often described as pitch accent

—it is in fact very similar to the prototypical pitch-accent language, Japanese

. In Carrier, a word may or may not have a tonic syllable. If it does not, the pitch rises gradually across the phonological word. If it does have a tonic syllable, then that syllable has a high pitch, the following syllable downsteps to a low pitch, and subsequent syllables until the end of the prosodic unit

are also low pitched. Any syllable in the word may carry the accent; if it is the final syllable, then the first syllable of the following word is low pitched, even if it would otherwise be tonic. Representing this phonemic drop in pitch with the downstep symbol ꜜ, there is a contrast between the surface tone following an unaccented word xoh "goose" compared with the accented word "wolf":

However, after a tonic syllable, the high pitch of "wolf" is lost:

Word-internally consonant clusters occur only at the juncture between two syllables. Tautosyllablic clusters are found only word-initially, where any of the onset consonants may be preceded by /s/ or /ɬ/.

Nasals at all points of articulation are syllabic word-initially preceding a consonant.

The only diacritic it uses in its standard form is the underscore, which is written under ⟨s⟩, ⟨z⟩, ⟨ts⟩, and ⟨dz⟩ to indicate that the consonant is lamino-dental rather than apico-alveolar. An acute accent is sometimes used to mark high tone, but tone is not routinely written in Carrier.

Carrier was formerly written in a derivative of the Cree Syllabics

Carrier was formerly written in a derivative of the Cree Syllabics

known variously as the Carrier syllabics

or Déné Syllabics. This writing system was widely used for several decades from its inception in 1885 but began to fade in the 1930s. Today only a few people can read it.

A good deal of scholarly material, together with the first edition of the "Little Catechism" and the Third Edition of the Prayerbook, is written in the writing system used by Father Adrien-Gabriel Morice

in his scholarly work. This writing system is a somewhat idiosyncratic version of the phonetic transcription of the time. It is subphonemic and was never used by Carrier people themselves, though many learned to read the Prayerbook in it.

and number

of the possessor. possession

is marked by prefixation as well, in some cases, as changes in the noun stem. Number is marked only on nouns denoting human beings and dogs, and these distinguish only singular and plural. Some dialects of Carrier have no number distinctions in nouns at all.

A noun has six basic personal possessive forms:

Possessive Paradigm of stick

Reading row-wise, these mean "my stick", "our stick", "your (1 person) stick", "your (two or more people) stick", "his/her/its stick", and "their stick".

However, in some dialects, such as that of Stony Creek, there is a distinction between first person dual and first person plural possessors:

Possessive Paradigm of stick (Stoney Creek dialect)

In such dialects, while the 1d and 1p are distinct, the 1d is the same as the 2dp.

There are five additional third person possessive forms:

The areal form is used when the possessor is saliently areal, spatial, or an extent of time. The reflexive is used when the subject of the clause and the possessor are the same, whether singular or plural. The disjoint form is used when both subject and possessor are third person singular and are not the same. The plural disjoint form is used when the subject is third person plural, the possessor is third person singular, and the possessor is not one of the individuals in the subject group.

The reciprocal form, meaning "each other's", was used into the early twentieth century but has

since fallen out of use.

The twelfth possessive form is almost always found on inalienably possessed

nouns. These are nouns that may not occur as words in their own right. In Carrier, the great majority of such nouns are either body parts or kinship terms. For example, although we can abstract the stem /ke/ from forms for "foot" such as /ske/ ('my foot'), /neke/ ('our feet'), and /uke/ ('his foot'), /ke/ by itself is not a word. It must either occur with a possessive prefix or as part of a compound, such as /kekˈetɬˈu/ ('sock'). To refer to an inalienably possessed noun without specifying its owner, the indefinite possessive prefix /ʔ/ is used. The approximate equivalent of "a foot" is therefore /ʔəke/.

To describe alienable possession of an inalienably possessed noun, the regular possessive forms are used with the indefinite form as a base rather than the bare stem. Thus, to say "my foot" if the foot is not your own foot but is, for example, a rabbit's foot, you would say [seʔəke]. (The fact that the vowel is [e] rather than [ə] is the result of a phonological rule that changes /ə/ to [e] immediately preceding /ʔ/ in noun prefixes and in the disjunct zone of the verb.)

Most Dakelh nouns do not have distinct singular and plural forms.

How many items are under discussion may be inferred from context

or may be specified by using a number or quantifier; otherwise, it

remains ambiguous. With very limited exceptions, only nouns denoting

human beings and dogs have distinct plural forms.

The most common way of forming the plural is by adding the suffix /-ne/.

Thus, we have /dəne/ "man", /dənene/ "men", /dakelh/ "Dakelh person", /dakelhne/ "Dakelh people".

Nouns derived from verbs by adding the suffix /-ən/ form their plurals by replacing /-ən/ with /-ne/. Thus we have /hodəɬʔeh-ən/ "teacher", /hodəɬʔeh-ne/ "teachers".

A smaller but nonetheless considerable number of nouns take the plural suffix /-ke/, e.g. /ɬi/ "dog", /ɬike/ "dogs". This is the usual way of making the plural of kinship terms, e.g. /nelu/ "our mother", /neluke/ "our mothers". The plural suffix /-ne/ is occasionally heard on kinship terms, but the suffix /-ke/ is more widely used and generally considered to be more correct. The plural of "dog" is invariably /ɬike/, never /ɬine/.

In addition, there are a handful of nouns with irregular

plurals:

/ʔat/ "wife" is also found with the

more regular plural /ʔatke/. /tʼet/ is sometimes found

with the double plural /tʼedəkune/. /-dəs/ "parent, ancestor"

is also found with the undoubled plural /-dəske/.

The exceptions to the statement that only nouns denoting human beings

and dogs have distinct plurals are all nouns derived from verbs.

The form of the underlying verb may vary with number in such a way as

to create distinct number forms for the derived noun.

Where the deverbal noun is derived by means of the agentive suffix

/ -ən/ the verb is almost invariably in the third person

singular form, which is to say, not marked for number. Plurality

in these forms is normally marked only by the use of the duo-plural

agentive suffix /-ne/ in place of singular /-ən/.

Zero-derived agentive nouns may show plurality by means of subject

markers. For example, "shaman" may be either /dəjən-ən/,

with an overt agentive suffix, but the zero-marked /dəjən/

is more common. There are two plural forms: /dəjən-ne/,

with the duo-plural agentive suffix, and /hədəjən/, in

which the zero-marked form is based on the plural form of the verb.

There are two other cases in which the underlying verb may

lead to a number distinction in the derived nouns. One is when

the verb is restricted in the number of its absolutive argument.

For example, there are two verbs "to kill", one that takes a

singular or dual object, another that takes a strictly plural object.

Since the word "prey" is derived from "kill", there

are a singular-dual form /beˈdəzəlɡɣe-i/, based on the stem

/-ɡhe/ "kill one or two" and a plural form /beˈdəɣan-i/,

based on the stem /ɣan/ "kill three or more".

The other case in which the underlying verb induces a number

distinction in the derived noun is when the verb contains a

prefix such as distributive /n/. For example,

/nati/

"cross-road" has the duo-plural

/nanəti/. Similarly,

/ˈədzatbeti/

"rabbit trail" has the duo-plural

/ˈədzatbenəti/. Such examples arise because the "noun"

/ti/ "road, trail" is really a verb and takes the distributive

prefix.

Even if a noun possesses a plural form, it is not necessary for it

to take on the plural form in order to have a plural meaning.

Indeed, there is a strong tendency to avoid overt marking of the

plural if plurality is indicated in other ways, in particular,

by an immediately following possessed noun. For example, the

full form of "Dakelh language" is /dakeɬne bəɣəni/, literally

"the words of the Dakelh people". Here /dakeɬne/ consists of

/dakeɬ/ "Dakelh person with the plural suffix /-ne/,

and /bəɣəni/ is the third person plural possessed form of /xəni/

"words". The plurality of the possessor is indicated by the use of

the third person duo-plural possessive prefix /bə/ instead of the

third person singular /u/.

The form /dakeɬ bəɣəni/, in which

/dakeɬ/ is not overtly plural-marked, is much preferred.

Object Paradigm of for

The postposition /be/ "by means of" is unusual in being uninflectable. At the other extreme, the postposition /ɬ/ "together with" is always inflected, even when its object is an overt noun phrase.

Whereas the reciprocal possessive form of nouns is obsolete, the reciprocal object of postpositions remains in common use. The form /ɬba/, for example, may be used in roughly the same contexts as the English phrase "for each other".

and number of the subject, object, and indirect object, tense, mood, numerous aspect

ual categories, and negation

. The subjects of verbs, and in some dialects objects and indirect objects, distinguish singular, dual, and plural numbers. Verbs are also marked for numerous "derivational" categories. For example, a basic motion verb, such as "walk" has derivatives meaning "walk into water", "walk into a hole", "walk ashore", "walk around" and "walk erroneously" (that is, "get lost walking").

The basic paradigm of a verb consists of three persons in three numbers, with the tenses and modes Imperfective, Perfective, Future, and Optative, in both affirmative and negative forms. Notice how the stem of the verb changes with tense/aspect/mode and negation, e.g. /ke/ in the Imperfective Affirmative but /koh/ in the Imperfective Negative and /ki/ in the Perfective Affirmative. In addition to the stem, the forms below contain the prefix /n/ "around, in a loop".

Go Around By Boat

Carrier has multiple systems of noun classification, several of which are realized on the verb. One of these, the system of absolutive or gender classifiers, consists of the prefixes /n/, /d/, and /xʷ/, which indicate that the absolutive argument (the subject of an intransitive verb or the object of a transitive verb) is round, stick-like, or areal/spatial, respectively. Some verbs can take any or none of these prefixes. Others can take only a subset or none at all. For example, the verb "to be white" has the forms:

comes at the end of the clause

, adposition

s are postpositions rather than prepositions, and complementizers follow their clause. However, it is not consistently head-final: in head-external relative clauses, the relative clause

follows the head noun. Carrier has both head-internal and head-external relative clauses. The subject

usually precedes the object if one is present.

Carrier is an "everything drop" language. A verb can form a grammatical sentence by itself. It is not in general necessary for the subject or object to be expressed overtly by a noun phrase or pronoun

.

[ɬeʔzəstʼət] "I am not smoking (unspecified object)"

is acceptable since the object marker (underlyingly just /ʔ/, with epenthetic /ə/ changed to [e] because it immediately precedes /ʔ/ in the disjunct zone) is part of the verb, but

[dekʼa ɬəzəstʼət] "I am not smoking tobacco"

is bizarre because the object /dekʼa/ "tobacco" is a separate noun phrase. The bizarreness results from the fact that the negative morphology of the verb does not have scope over the NP object. In order to bring the object within the scope of negation, it must follow the negative particle /ʔaw:

/ʔaw dekʼa ɬəzəstʼət/ "I am not smoking tobacco"

and Chilcotin

. As noted above, the term "Carrier" has often been applied to both Carrier proper and Babine-Witsuwit'en

but this identification is now rejected by specialists. The Ethnologue

treats Carrier proper as consisting of two languages, Carrier (code: crx) and Southern Carrier (code: caf), where the latter consists of the dialects of the Ulkatcho, Kluskus, Nazko, and Red Bluff bands. More recent research disputes the treatment of "Southern Carrier" as a distinct language and in fact classifies this dialect group as one of two parts of a larger "Southern Carrier" dialect group that contains all of Carrier proper except for the Stuart/Trembleur Lake dialect. Southern Carrier in the sense of the Ethnologue, that is, the Blackwater dialect group, is mutually comprehensible with all other Carrier dialects.

Much of the literature distinguishes Central Carrier from Southern Carrier. Unfortunately, the usage of these terms is quite variable. Almost all material in or about Central Carrier is in the Stuart Lake dialect. However, Central Carrier cannot be taken to be a synonym for Stuart-Trembleur Lake dialect because some of the more northerly of the Southern Carrier dialects, particularly Saik'uz dialect, are sometimes included in Central Carrier.

Much of the literature distinguishes Central Carrier from Southern Carrier. Unfortunately, the usage of these terms is quite variable. Almost all material in or about Central Carrier is in the Stuart Lake dialect. However, Central Carrier cannot be taken to be a synonym for Stuart-Trembleur Lake dialect because some of the more northerly of the Southern Carrier dialects, particularly Saik'uz dialect, are sometimes included in Central Carrier.

Although all speakers of all varieties of Carrier can communicate with each other with little difficulty, the dialects are quite diverse. They differ from each other not only in phonological details and lexicon but in morphology and even syntax.

and Haisla

, to the north by Sekani

, to the southeast by Shuswap

, to the south by Chilcotin

, and to the southwest by Nuxalk

. Furthermore, in the past few centuries, with the westward movement of the Plains Cree, there has been contact with the Cree from the East. Carrier has borrowed from some of these languages, but apparently not in large numbers. Loans from Cree include [məsdus] ('cow') from Cree (which originally meant "buffalo" but extended to "cow" already in Cree) and [sunija] ('money, precious metal'). There are also loans from languages that do not directly neighbor Carrier territory. A particularly interesting example is [maj] ('berry, fruit'), a loan from Gitksan, which has been borrowed into all Carrier dialects and has displaced the original Athabascan word.

European contact has brought loans from a number of sources. The majority of demonstrable loans into Carrier are from French, though it is not generally clear whether they come directly from French or via Chinook Jargon

European contact has brought loans from a number of sources. The majority of demonstrable loans into Carrier are from French, though it is not generally clear whether they come directly from French or via Chinook Jargon

. Loans from French include [liɡok] ('chicken') (from French le coq 'rooster'), [lisel] (from le sel 'salt'), and [lizas] ('angel'). As these examples show, the French article is normally incorporated into the Carrier borrowing. A single loan from Spanish

is known: [mandah] ('canvas, tarpaulin'), apparently acquired from Spanish-speaking packers.

The trade language Chinook Jargon

came into use among Carrier people as a result of European contact. Most Carrier people never knew Chinook Jargon. It appears to have been known in most areas primarily by men who had spent time freighting on the Fraser River

. Knowledge of Chinook Jargon may have been more common in the southwestern

part of Carrier country due to its use at Bella Coola

. The southwestern dialects have more loans from Chinook Jargon than other dialects. For example, while most dialects use the Cree loan described above for "money", the southwestern dialects use [tʃikəmin], which is from Chinook Jargon. The word [daji] ('chief') is a loan from Chinook Jargon.

European contact brought many new objects and ideas. The names for some were borrowed, but in most cases terms have been created using the morphological resources of the language, or by extending or shifting the meaning of existing terms. Thus, [tɬʼuɬ] now means not only "rope" but also "wire", while [kʼa] has shifted from its original meaning of "arrow" to mean "cartridge" and [ʔəɬtih] has shifted from "bow" to "rifle". [hutʼəp], originally "leeches" now also means "pasta".

A microwave oven is referred to as [ʔa benəlwəs] ('that by means of which things are warmed quickly'). "Mustard" is [tsʼudənetsan] ('children's feces'), presumably after the texture and color rather than the flavor.

, Carrier is an endangered language

. Only about 10% of Dakelh people now speak the Carrier language, hardly any of them children. Members of the generation following that of the last speakers can often understand the language but they do not contribute to its transmission.

Carrier is taught as a second language in both public and band schools throughout Carrier

territory. This instruction provides an acquaintance with the language but has not proven effective in producing functional knowledge of the language. Carrier has also been taught at the University of Northern British Columbia

, the College of New Caledonia

, and the University of British Columbia

.

The Yinka Dene Language Institute

(YDLI) is charged with the maintenance and promotion of Carrier language and culture. Its activities include research, archiving, curriculum development, teacher training, literacy instruction, and production of teaching and reference materials. Prior to the founding of YDLI in 1988 the Carrier Linguistic Committee, a group based in Fort Saint James affiliated with the Summer Institute of Linguistics, produced a number of publications in Carrier, literacy materials for several dialects, a 3000-entry dictionary of the Stuart Lake dialect, and various other materials. The Carrier Linguistic Committee is largely responsible for literacy among younger speakers of the language. The Carrier Bible Translation Committee produced a translation of the New Testament that was published in 1995. An adaptation to Blackwater dialect appeared in 2002.

for the year 1806 and by a list of over 300 words given in an appendix to his journal by Daniel Harmon

, published in 1820. The first known text by native speakers of Carrier is the Barkerville Jail Text of 1885.

Dakelh

The Dakelh or Carrier are the indigenous people of a large portion of the Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada.Most Carrier call themselves Dakelh, meaning "people who go around by boat"...

people, a First Nations

First Nations

First Nations is a term that collectively refers to various Aboriginal peoples in Canada who are neither Inuit nor Métis. There are currently over 630 recognised First Nations governments or bands spread across Canada, roughly half of which are in the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia. The...

people of the Central Interior of British Columbia

British Columbia Interior

The British Columbia Interior or BC Interior or Interior of British Columbia, usually referred to only as the Interior, is one of the three main regions of the Canadian province of British Columbia, the other two being the Lower Mainland, which comprises the overlapping areas of Greater Vancouver...

, Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, for whom Carrier is the usual English name. People who are referred to as Carrier speak two related languages. One, Babine-Witsuwit'en

Babine-Witsuwit'en

-External links:****** Note, however, that the Carrier-speaking region is marked incorrectly on this map and that Babine-Witsuwit'en is not indicated. The area around Babine Lake and Takla Lake, included in the Dakelh region on the map, is actually Babine speaking...

is sometimes referred to as Northern Carrier. The other, Carrier proper, includes what are sometimes referred to as Central Carrier and Southern Carrier.

Consonants

All dialects of Carrier have essentially the same consonant system, which is shown in this chart.| Bilabial Bilabial consonant In phonetics, a bilabial consonant is a consonant articulated with both lips. The bilabial consonants identified by the International Phonetic Alphabet are:... |

Alveolar Alveolar consonant Alveolar consonants are articulated with the tongue against or close to the superior alveolar ridge, which is called that because it contains the alveoli of the superior teeth... |

Post- alveolar Postalveolar consonant Postalveolar consonants are consonants articulated with the tongue near or touching the back of the alveolar ridge, further back in the mouth than the alveolar consonants, which are at the ridge itself, but not as far back as the hard palate... |

Velar Velar consonant Velars are consonants articulated with the back part of the tongue against the soft palate, the back part of the roof of the mouth, known also as the velum).... |

Glottal Glottal consonant Glottal consonants, also called laryngeal consonants, are consonants articulated with the glottis. Many phoneticians consider them, or at least the so-called fricative, to be transitional states of the glottis without a point of articulation as other consonants have; in fact, some do not consider... |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| central | lateral | plain | labial | |||||

| Nasal Nasal consonant A nasal consonant is a type of consonant produced with a lowered velum in the mouth, allowing air to escape freely through the nose. Examples of nasal consonants in English are and , in words such as nose and mouth.- Definition :... |

m | n | (ɲ) | (ŋ) | ||||

| Plosive | unaspirated | p | t | k | kʷ | ʔ | ||

| aspirated Aspiration (phonetics) In phonetics, aspiration is the strong burst of air that accompanies either the release or, in the case of preaspiration, the closure of some obstruents. To feel or see the difference between aspirated and unaspirated sounds, one can put a hand or a lit candle in front of one's mouth, and say pin ... |

tʰ | kʰ | kʷʰ | |||||

| ejective | tʼ | kʼ | kʷʼ | |||||

| Affricate Affricate consonant Affricates are consonants that begin as stops but release as a fricative rather than directly into the following vowel.- Samples :... |

unaspirated | ts | tɬ | tʃ | ||||

| aspirated | tsʰ | tɬʰ | tʃʰ | |||||

| ejective | tsʼ | tɬʼ | tʃʼ | |||||

| Fricative Fricative consonant Fricatives are consonants produced by forcing air through a narrow channel made by placing two articulators close together. These may be the lower lip against the upper teeth, in the case of ; the back of the tongue against the soft palate, in the case of German , the final consonant of Bach; or... |

voiceless | (f) | s | ɬ | ʃ | x | xʷ | h |

| voiced | z | ɣ | (ɣʷ) | |||||

| Approximant Approximant consonant Approximants are speech sounds that involve the articulators approaching each other but not narrowly enough or with enough articulatory precision to create turbulent airflow. Therefore, approximants fall between fricatives, which do produce a turbulent airstream, and vowels, which produce no... |

(r) | l | j | w | ||||

There are three series of stops and affricates: aspirated, unaspirated (written voiced in the practical orthography), and ejective.

/r/ is not native to the language but has been introduced by loans from French and English. /f/ occurs in a single loanword "coffee". The labialized voiced velar fricative /ɣʷ/ is found only in the speech of the most conservative speakers; for most speakers it has merged with /w/. The palatal nasal /ɲ/ occurs allophonically before other palatal consonants; otherwise, it occurs only in a small set of 2nd-person singular

Grammatical person

Grammatical person, in linguistics, is deictic reference to a participant in an event; such as the speaker, the addressee, or others. Grammatical person typically defines a language's set of personal pronouns...

morphemes. For most speakers it has become an [n̩j] sequence, with a syllabic [n]. Similarly, the velar nasal /ŋ/ occurs allophonically before other velar consonants but is found distinctively in one or two morphemes in each dialect.

Carrier once had a dental/alveolar (or laminal

Laminal consonant

A laminal consonant is a phone produced by obstructing the air passage with the blade of the tongue, which is the flat top front surface just behind the tip of the tongue on the top. This contrasts with apical consonants, which are produced by creating an obstruction with the tongue apex only...

/apical

Apical consonant

An apical consonant is a phone produced by obstructing the air passage with the apex of the tongue . This contrasts with laminal consonants, which are produced by creating an obstruction with the blade of the tongue .This is not a very common distinction, and typically applied only to fricatives...

) distinction, attested in the earliest grammatical treatise of the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. However, by 1976 this had been leveled to the present alveolar series among younger speakers, and in 1981 the dental/laminal series (marked by underlining the consonant) was said to be found in only the "very oldest speakers". Poser (2005) states that it is found in only the most conservative speech. In even the earliest description, there is evidence of the distinction being neutralized.

Vowels

Carrier has six surface-phonemic vowels: /i/, /u/, /e/, /o/, /a/, and /ə/. The first four are tense in open syllables and lax in closed syllables. The reduced vowel /ə/ is quite variable in its realization: it approaches [i] immediately preceding /j/ and approaches [a] when either or both adjacent consonants are laryngealLaryngeal

Laryngeal may mean*pertaining to the larynx*in Indo-European linguistics, a consonant postulated in the laryngeal theory*in phonetics, an alternate term for glottal sounds....

. Unlike in some related languages, there is no distinctive nasalization; that is, Carrier does not contrast oral and nasal vowel

Nasal vowel

A nasal vowel is a vowel that is produced with a lowering of the velum so that air escapes both through nose as well as the mouth. By contrast, oral vowels are ordinary vowels without this nasalisation...

s.

The great majority of instances of /ə/ are predictable from the phonotactics, introduced in order to create an acceptable syllable structure. The remaining instances are all found in certain forms of the verb where the morphology requires some vowel to be present.

In most if not all dialects there are surface-phonemic distinctions of vowel length

Vowel length

In linguistics, vowel length is the perceived duration of a vowel sound. Often the chroneme, or the "longness", acts like a consonant, and may etymologically be one, such as in Australian English. While not distinctive in most dialects of English, vowel length is an important phonemic factor in...

. However, all of the long vowels that create such distinctions are morphophonemically derived. There is no need to represent vowel length in lexical representations.

Tone

Carrier has a very simple toneTone (linguistics)

Tone is the use of pitch in language to distinguish lexical or grammatical meaning—that is, to distinguish or inflect words. All verbal languages use pitch to express emotional and other paralinguistic information, and to convey emphasis, contrast, and other such features in what is called...

system of the type often described as pitch accent

Pitch accent

Pitch accent is a linguistic term of convenience for a variety of restricted tone systems that use variations in pitch to give prominence to a syllable or mora within a word. The placement of this tone or the way it is realized can give different meanings to otherwise similar words...

—it is in fact very similar to the prototypical pitch-accent language, Japanese

Japanese pitch accent

Japanese pitch accent is a feature of the Japanese language which distinguishes words in most Japanese dialects, though the nature and location of the accent for a given word may vary between dialects...

. In Carrier, a word may or may not have a tonic syllable. If it does not, the pitch rises gradually across the phonological word. If it does have a tonic syllable, then that syllable has a high pitch, the following syllable downsteps to a low pitch, and subsequent syllables until the end of the prosodic unit

Prosodic unit

In linguistics, a prosodic unit, often called an intonation unit or intonational phrase, is a segment of speech that occurs with a single prosodic contour...

are also low pitched. Any syllable in the word may carry the accent; if it is the final syllable, then the first syllable of the following word is low pitched, even if it would otherwise be tonic. Representing this phonemic drop in pitch with the downstep symbol ꜜ, there is a contrast between the surface tone following an unaccented word xoh "goose" compared with the accented word "wolf":

- [xóh niɬʔén]

- "He sees the goose."

- [jésꜜ nìɬʔèn]

- "He sees the wolf."

However, after a tonic syllable, the high pitch of "wolf" is lost:

- [ʔiɬóꜜ jèsꜜ]

- "One wolf"

Phonotactics

In general the Carrier syllable is maximally CVC. All consonants other than the extremely rare /ŋ/ are found in syllable-initial position. The possible coda consonants, on the other hand, are restricted. All of the sonorants except for the extremely rare palatal nasal may occur in the coda, but of the obstruents only the pulmonic unaspirated series occur. Affricates are not found in the coda with the exception of a few instances of /ts/. Palatals are also absent from the coda.Word-internally consonant clusters occur only at the juncture between two syllables. Tautosyllablic clusters are found only word-initially, where any of the onset consonants may be preceded by /s/ or /ɬ/.

Nasals at all points of articulation are syllabic word-initially preceding a consonant.

Writing system

The writing system in general use today is the Carrier Linguistic Committee writing system, a Roman-based system developed in the 1960s by Summer Institute of Linguistics missionaries and a group of Carrier people with whom they worked. The CLC writing system was designed to be typed on a standard English typewriter. It uses numerous digraphs and trigraphs to write the many Carrier consonants not found in English, e.g. ⟨gh⟩ for [ɣ] and ⟨lh⟩ for [ɬ], with an apostrophe to mark glottalization, e.g. ⟨ts'⟩ for the ejective alveolar affricate. Letters generally have their English rather than European values. For example, ⟨u⟩ represents /ə/ while ⟨oo⟩ represents /u/.The only diacritic it uses in its standard form is the underscore, which is written under ⟨s⟩, ⟨z⟩, ⟨ts⟩, and ⟨dz⟩ to indicate that the consonant is lamino-dental rather than apico-alveolar. An acute accent is sometimes used to mark high tone, but tone is not routinely written in Carrier.

Cree syllabics

Cree syllabics, found in two primary variants, are the versions of Canadian Aboriginal syllabics used to write Cree dialects, including the original syllabics system created for Cree and Ojibwe. Syllabics were later adapted to several other languages...

known variously as the Carrier syllabics

Carrier syllabics

Carrier or Déné syllabics is a script created by Adrien-Gabriel Morice for the Carrier language. It was inspired by Cree syllabics and is one of the writing systems in the Canadian Aboriginal syllabics Unicode range.-History:...

or Déné Syllabics. This writing system was widely used for several decades from its inception in 1885 but began to fade in the 1930s. Today only a few people can read it.

A good deal of scholarly material, together with the first edition of the "Little Catechism" and the Third Edition of the Prayerbook, is written in the writing system used by Father Adrien-Gabriel Morice

Adrien-Gabriel Morice

Adrien-Gabriel Morice was a missionary priest belonging to the Oblates of Mary Immaculate. He served as a missionary in Canada, and created a writing system for the Carrier language.-Early life:...

in his scholarly work. This writing system is a somewhat idiosyncratic version of the phonetic transcription of the time. It is subphonemic and was never used by Carrier people themselves, though many learned to read the Prayerbook in it.

Nouns

Carrier nouns are inflected for possession, including the personGrammatical person

Grammatical person, in linguistics, is deictic reference to a participant in an event; such as the speaker, the addressee, or others. Grammatical person typically defines a language's set of personal pronouns...

and number

Grammatical number

In linguistics, grammatical number is a grammatical category of nouns, pronouns, and adjective and verb agreement that expresses count distinctions ....

of the possessor. possession

Possession (linguistics)

Possession, in the context of linguistics, is an asymmetric relationship between two constituents, the referent of one of which possesses the referent of the other ....

is marked by prefixation as well, in some cases, as changes in the noun stem. Number is marked only on nouns denoting human beings and dogs, and these distinguish only singular and plural. Some dialects of Carrier have no number distinctions in nouns at all.

A noun has six basic personal possessive forms:

Possessive Paradigm of stick

| sg | pl | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | /sdətʃən/ | /nedətʃən/ |

| 2 | /ndətʃən/ | /nahdətʃən/ |

| 3 | /udətʃən/ | /bədətʃən/ |

Reading row-wise, these mean "my stick", "our stick", "your (1 person) stick", "your (two or more people) stick", "his/her/its stick", and "their stick".

However, in some dialects, such as that of Stony Creek, there is a distinction between first person dual and first person plural possessors:

Possessive Paradigm of stick (Stoney Creek dialect)

| sg | du | pl | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | /sdətʃən/ | /nahdətʃən/ | /nedətʃən/ |

| 2 | /ndətʃən/ | /nahdətʃən/ | /nahdətʃən/ |

| 3 | /udətʃən/ | /həbədətʃən/ | /həbədətʃən/ |

In such dialects, while the 1d and 1p are distinct, the 1d is the same as the 2dp.

There are five additional third person possessive forms:

| Areal | /xwədətʃən/ |

|---|---|

| Reflexive | /dədətʃən/ |

| Disjoint | /jədətʃən/ |

| Plural disjoint | /hidətʃən/ |

| Reciprocal | /ɬdətʃən/ |

The areal form is used when the possessor is saliently areal, spatial, or an extent of time. The reflexive is used when the subject of the clause and the possessor are the same, whether singular or plural. The disjoint form is used when both subject and possessor are third person singular and are not the same. The plural disjoint form is used when the subject is third person plural, the possessor is third person singular, and the possessor is not one of the individuals in the subject group.

The reciprocal form, meaning "each other's", was used into the early twentieth century but has

since fallen out of use.

The twelfth possessive form is almost always found on inalienably possessed

Inalienable possession

In linguistics, inalienable possession refers to the linguistic properties of certain nouns or nominal morphemes based on the fact that they are always possessed. The semantic underpinning is that entities like body parts and relatives do not exist apart from a possessor. For example, a hand...

nouns. These are nouns that may not occur as words in their own right. In Carrier, the great majority of such nouns are either body parts or kinship terms. For example, although we can abstract the stem /ke/ from forms for "foot" such as /ske/ ('my foot'), /neke/ ('our feet'), and /uke/ ('his foot'), /ke/ by itself is not a word. It must either occur with a possessive prefix or as part of a compound, such as /kekˈetɬˈu/ ('sock'). To refer to an inalienably possessed noun without specifying its owner, the indefinite possessive prefix /ʔ/ is used. The approximate equivalent of "a foot" is therefore /ʔəke/.

To describe alienable possession of an inalienably possessed noun, the regular possessive forms are used with the indefinite form as a base rather than the bare stem. Thus, to say "my foot" if the foot is not your own foot but is, for example, a rabbit's foot, you would say [seʔəke]. (The fact that the vowel is [e] rather than [ə] is the result of a phonological rule that changes /ə/ to [e] immediately preceding /ʔ/ in noun prefixes and in the disjunct zone of the verb.)

Most Dakelh nouns do not have distinct singular and plural forms.

How many items are under discussion may be inferred from context

or may be specified by using a number or quantifier; otherwise, it

remains ambiguous. With very limited exceptions, only nouns denoting

human beings and dogs have distinct plural forms.

The most common way of forming the plural is by adding the suffix /-ne/.

Thus, we have /dəne/ "man", /dənene/ "men", /dakelh/ "Dakelh person", /dakelhne/ "Dakelh people".

Nouns derived from verbs by adding the suffix /-ən/ form their plurals by replacing /-ən/ with /-ne/. Thus we have /hodəɬʔeh-ən/ "teacher", /hodəɬʔeh-ne/ "teachers".

A smaller but nonetheless considerable number of nouns take the plural suffix /-ke/, e.g. /ɬi/ "dog", /ɬike/ "dogs". This is the usual way of making the plural of kinship terms, e.g. /nelu/ "our mother", /neluke/ "our mothers". The plural suffix /-ne/ is occasionally heard on kinship terms, but the suffix /-ke/ is more widely used and generally considered to be more correct. The plural of "dog" is invariably /ɬike/, never /ɬine/.

In addition, there are a handful of nouns with irregular

plurals:

| Singular | Plural | Gloss |

| ʔat | ʔatku | wife |

| tʃiɬ | tʃilke | young man |

| -tʃəl | -tʃisle | younger brother |

| -dəs | -dəsneke | ancestor |

| kʼeke | kʼekuke | friend |

| tʼet | tʼedəku | young woman |

| tsʼeke | tsʼeku | woman |

/ʔat/ "wife" is also found with the

more regular plural /ʔatke/. /tʼet/ is sometimes found

with the double plural /tʼedəkune/. /-dəs/ "parent, ancestor"

is also found with the undoubled plural /-dəske/.

The exceptions to the statement that only nouns denoting human beings

and dogs have distinct plurals are all nouns derived from verbs.

The form of the underlying verb may vary with number in such a way as

to create distinct number forms for the derived noun.

Where the deverbal noun is derived by means of the agentive suffix

/ -ən/ the verb is almost invariably in the third person

singular form, which is to say, not marked for number. Plurality

in these forms is normally marked only by the use of the duo-plural

agentive suffix /-ne/ in place of singular /-ən/.

Zero-derived agentive nouns may show plurality by means of subject

markers. For example, "shaman" may be either /dəjən-ən/,

with an overt agentive suffix, but the zero-marked /dəjən/

is more common. There are two plural forms: /dəjən-ne/,

with the duo-plural agentive suffix, and /hədəjən/, in

which the zero-marked form is based on the plural form of the verb.

There are two other cases in which the underlying verb may

lead to a number distinction in the derived nouns. One is when

the verb is restricted in the number of its absolutive argument.

For example, there are two verbs "to kill", one that takes a

singular or dual object, another that takes a strictly plural object.

Since the word "prey" is derived from "kill", there

are a singular-dual form /beˈdəzəlɡɣe-i/, based on the stem

/-ɡhe/ "kill one or two" and a plural form /beˈdəɣan-i/,

based on the stem /ɣan/ "kill three or more".

The other case in which the underlying verb induces a number

distinction in the derived noun is when the verb contains a

prefix such as distributive /n/. For example,

/nati/

"cross-road" has the duo-plural

/nanəti/. Similarly,

/ˈədzatbeti/

"rabbit trail" has the duo-plural

/ˈədzatbenəti/. Such examples arise because the "noun"

/ti/ "road, trail" is really a verb and takes the distributive

prefix.

Even if a noun possesses a plural form, it is not necessary for it

to take on the plural form in order to have a plural meaning.

Indeed, there is a strong tendency to avoid overt marking of the

plural if plurality is indicated in other ways, in particular,

by an immediately following possessed noun. For example, the

full form of "Dakelh language" is /dakeɬne bəɣəni/, literally

"the words of the Dakelh people". Here /dakeɬne/ consists of

/dakeɬ/ "Dakelh person with the plural suffix /-ne/,

and /bəɣəni/ is the third person plural possessed form of /xəni/

"words". The plurality of the possessor is indicated by the use of

the third person duo-plural possessive prefix /bə/ instead of the

third person singular /u/.

The form /dakeɬ bəɣəni/, in which

/dakeɬ/ is not overtly plural-marked, is much preferred.

Postpositions

Most postpositions are inflected for their object in a manner closely resembling the marking of possession on nouns. The inflected forms are used when the object is not a full noun phrase. Here is the paradigm of /ba/ "for":Object Paradigm of for

| sg | pl | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | /sba/ | /neba/ |

| 2 | /mba/ | /nohba/ |

| 3 | /uba/ | /bəba/ |

| Areal | /həba/ |

|---|---|

| Reflexive | /dəba/ |

| Disjoint | /jəba/ |

| Plural disjoint | /hiba/ |

| Reciprocal | /ɬba/ |

The postposition /be/ "by means of" is unusual in being uninflectable. At the other extreme, the postposition /ɬ/ "together with" is always inflected, even when its object is an overt noun phrase.

Whereas the reciprocal possessive form of nouns is obsolete, the reciprocal object of postpositions remains in common use. The form /ɬba/, for example, may be used in roughly the same contexts as the English phrase "for each other".

Verbs

The Carrier verb is extremely complex. A single verb may have hundreds of thousands of forms. Verbs are marked for the personGrammatical person

Grammatical person, in linguistics, is deictic reference to a participant in an event; such as the speaker, the addressee, or others. Grammatical person typically defines a language's set of personal pronouns...

and number of the subject, object, and indirect object, tense, mood, numerous aspect

Aspect

Aspect may be:*Aspect , a feature that is linked to many parts of a program, but which is not necessarily the primary function of the program...

ual categories, and negation

Negation

In logic and mathematics, negation, also called logical complement, is an operation on propositions, truth values, or semantic values more generally. Intuitively, the negation of a proposition is true when that proposition is false, and vice versa. In classical logic negation is normally identified...

. The subjects of verbs, and in some dialects objects and indirect objects, distinguish singular, dual, and plural numbers. Verbs are also marked for numerous "derivational" categories. For example, a basic motion verb, such as "walk" has derivatives meaning "walk into water", "walk into a hole", "walk ashore", "walk around" and "walk erroneously" (that is, "get lost walking").

The basic paradigm of a verb consists of three persons in three numbers, with the tenses and modes Imperfective, Perfective, Future, and Optative, in both affirmative and negative forms. Notice how the stem of the verb changes with tense/aspect/mode and negation, e.g. /ke/ in the Imperfective Affirmative but /koh/ in the Imperfective Negative and /ki/ in the Perfective Affirmative. In addition to the stem, the forms below contain the prefix /n/ "around, in a loop".

| Imperfective | Affirmative | Negative | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

| 1 | nəske | nike | nəts’əke | nəɬəzəskoh | nəɬəzikoh | nəɬts’əskoh | |

| 2 | ninke | nahke | nahke | nəɬəzinkoh | nəɬəzahkoh | nəɬəzahkoh | |

| 3 | nəke | nəhəke | nəhəke | nəɬəskoh | nəɬəhəskoh | nəɬəhəskoh | |

| Perfective | Affirmative | Negative | |||||

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

| 1 | nəsəski | nəsiki | nəts’əski | nəɬəskel | nəɬikel | nəɬts’ikel | |

| 2 | nəsinki | nəsahki | nəsahki | nəɬinkel | nəɬəhkel | nəɬəhkel | |

| 3 | nəsəki | nəhəzəki | nəhəzəki | nəɬikel | nəɬehikel | nəɬehikel | |

| Future | Affirmative | Negative | |||||

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

| 1 | nətiskeɬ | nətakeɬ | nəztikeɬ | nəɬtəziskel | nəɬtəzakel | nəɬts’ətiskel | |

| 2 | nətankeɬ | nətihkeɬ | nətihkeɬ | nəɬtəzankel | nəɬtəzihkel | nəɬtəzihkel | |

| 3 | nətikeɬ | notikeɬ | notikeɬ | nəɬtəziskel | nəɬotiskel | nəɬotiskel | |

| Optative | Affirmative | Negative | |||||

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

| 1 | noskeʔ | nokeʔ | nəts’ukeʔ | nəɬəzuskeʔ | nəɬəzokeʔ | nəɬts’uskeʔ | |

| 2 | nonkeʔ | nohkeʔ | nohkeʔ | nəɬəzonkeʔ | nəɬəzuhkeʔ | nəɬəzuhkeʔ | |

| 3 | nokeʔ | nəhukeʔ | nəhukeʔ | nəɬuskeʔ | nəɬəhuskeʔ | nəɬəhuskeʔ | |

Carrier has multiple systems of noun classification, several of which are realized on the verb. One of these, the system of absolutive or gender classifiers, consists of the prefixes /n/, /d/, and /xʷ/, which indicate that the absolutive argument (the subject of an intransitive verb or the object of a transitive verb) is round, stick-like, or areal/spatial, respectively. Some verbs can take any or none of these prefixes. Others can take only a subset or none at all. For example, the verb "to be white" has the forms:

| ɬjəl | it (generic) is white |

| nəljəl | it (round) is white |

| dəljəl | it (stick-like) is white |

| xʷəljəl | it (areal/spatial) is white |

Syntax

In general terms, Carrier is a head-final language: the verbVerb

A verb, from the Latin verbum meaning word, is a word that in syntax conveys an action , or a state of being . In the usual description of English, the basic form, with or without the particle to, is the infinitive...

comes at the end of the clause

Clause

In grammar, a clause is the smallest grammatical unit that can express a complete proposition. In some languages it may be a pair or group of words that consists of a subject and a predicate, although in other languages in certain clauses the subject may not appear explicitly as a noun phrase,...

, adposition

Adposition

Prepositions are a grammatically distinct class of words whose most central members characteristically express spatial relations or serve to mark various syntactic functions and semantic roles...

s are postpositions rather than prepositions, and complementizers follow their clause. However, it is not consistently head-final: in head-external relative clauses, the relative clause

Relative clause

A relative clause is a subordinate clause that modifies a noun phrase, most commonly a noun. For example, the phrase "the man who wasn't there" contains the noun man, which is modified by the relative clause who wasn't there...

follows the head noun. Carrier has both head-internal and head-external relative clauses. The subject

Subject (grammar)

The subject is one of the two main constituents of a clause, according to a tradition that can be tracked back to Aristotle and that is associated with phrase structure grammars; the other constituent is the predicate. According to another tradition, i.e...

usually precedes the object if one is present.

Carrier is an "everything drop" language. A verb can form a grammatical sentence by itself. It is not in general necessary for the subject or object to be expressed overtly by a noun phrase or pronoun

Pronoun

In linguistics and grammar, a pronoun is a pro-form that substitutes for a noun , such as, in English, the words it and he...

.

Scope phenomena

Verb-internal negation has low scope, meaning that, with certain exceptions, the scope of negation is restricted to the verb itself. Thus, a sentence like:[ɬeʔzəstʼət] "I am not smoking (unspecified object)"

is acceptable since the object marker (underlyingly just /ʔ/, with epenthetic /ə/ changed to [e] because it immediately precedes /ʔ/ in the disjunct zone) is part of the verb, but

[dekʼa ɬəzəstʼət] "I am not smoking tobacco"

is bizarre because the object /dekʼa/ "tobacco" is a separate noun phrase. The bizarreness results from the fact that the negative morphology of the verb does not have scope over the NP object. In order to bring the object within the scope of negation, it must follow the negative particle /ʔaw:

/ʔaw dekʼa ɬəzəstʼət/ "I am not smoking tobacco"

Classification

Carrier is generally regarded as one of three members of the central British Columbia subgroup of Athabascan, the other two being Babine-Witsuwit'enBabine-Witsuwit'en

-External links:****** Note, however, that the Carrier-speaking region is marked incorrectly on this map and that Babine-Witsuwit'en is not indicated. The area around Babine Lake and Takla Lake, included in the Dakelh region on the map, is actually Babine speaking...

and Chilcotin

Chilcotin

Chilcotin, meaning "people of the red ochre river" may refer to:*The Tsilhqot'in , an Athabaskan First Nations people of British Columbia, Canada*Chilcotin language, the language spoken by the Tsilhqot’in...

. As noted above, the term "Carrier" has often been applied to both Carrier proper and Babine-Witsuwit'en

Babine-Witsuwit'en

-External links:****** Note, however, that the Carrier-speaking region is marked incorrectly on this map and that Babine-Witsuwit'en is not indicated. The area around Babine Lake and Takla Lake, included in the Dakelh region on the map, is actually Babine speaking...

but this identification is now rejected by specialists. The Ethnologue

Ethnologue

Ethnologue: Languages of the World is a web and print publication of SIL International , a Christian linguistic service organization, which studies lesser-known languages, to provide the speakers with Bibles in their native language and support their efforts in language development.The Ethnologue...

treats Carrier proper as consisting of two languages, Carrier (code: crx) and Southern Carrier (code: caf), where the latter consists of the dialects of the Ulkatcho, Kluskus, Nazko, and Red Bluff bands. More recent research disputes the treatment of "Southern Carrier" as a distinct language and in fact classifies this dialect group as one of two parts of a larger "Southern Carrier" dialect group that contains all of Carrier proper except for the Stuart/Trembleur Lake dialect. Southern Carrier in the sense of the Ethnologue, that is, the Blackwater dialect group, is mutually comprehensible with all other Carrier dialects.

Dialects

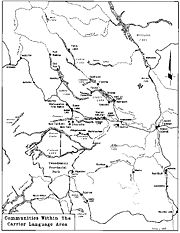

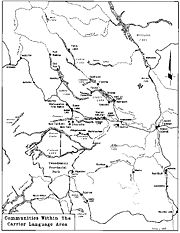

Current research divides Carrier into two major dialect groups, a Stuart-Trembleur Lake group, and a Southern group. The Southern group, in turn, is divided into two subgroups, the Fraser-Nechako group, comprising the communities of Cheslatta, Stellako, Nadleh, Saik'uz, and Lheidli, and the Blackwater group, comprising the communities of Lhk'acho (Ulgatcho), Lhoosk'uz (Kluskus), Nazko, and Lhtakoh (Red Bluff).

Although all speakers of all varieties of Carrier can communicate with each other with little difficulty, the dialects are quite diverse. They differ from each other not only in phonological details and lexicon but in morphology and even syntax.

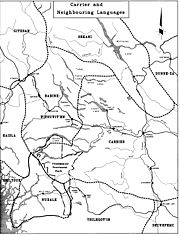

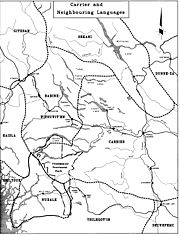

Contact with other languages

Carrier is neighbored on the west by Babine-Witsuwit'enBabine-Witsuwit'en

-External links:****** Note, however, that the Carrier-speaking region is marked incorrectly on this map and that Babine-Witsuwit'en is not indicated. The area around Babine Lake and Takla Lake, included in the Dakelh region on the map, is actually Babine speaking...

and Haisla

Haisla

The Haisla are an indigenous people living at Kitamaat in the North Coast region of the Canadian province of British Columbia. Their indigenous Haisla language is named after them...

, to the north by Sekani

Sekani

Sekani is the name of an Athabaskan First Nations people in the Northern Interior of British Columbia. Their territory includes the Finlay and Parsnip River drainages of the Rocky Mountain Trench. The neighbors of the Sekani are the Babine to the west, Dakelh to the south, Dunneza to the east, and...

, to the southeast by Shuswap

Shuswap

Shuswap *Secwepemc - an indigenous people in British Columbia, Canada, also known in English as the Shuswap*Shuswap language - a language spoken by the Secwepemc...

, to the south by Chilcotin

Chilcotin

Chilcotin, meaning "people of the red ochre river" may refer to:*The Tsilhqot'in , an Athabaskan First Nations people of British Columbia, Canada*Chilcotin language, the language spoken by the Tsilhqot’in...

, and to the southwest by Nuxalk

Nuxalk

Nuxálk are an indigenous people native to Bella Coola, British Columbia in Canada. The term can refer to:* Nuxálk language, a moribund Salishan language.* Nuxalk Nation, the name of the Nuxálk group in the First Nations....

. Furthermore, in the past few centuries, with the westward movement of the Plains Cree, there has been contact with the Cree from the East. Carrier has borrowed from some of these languages, but apparently not in large numbers. Loans from Cree include [məsdus] ('cow') from Cree (which originally meant "buffalo" but extended to "cow" already in Cree) and [sunija] ('money, precious metal'). There are also loans from languages that do not directly neighbor Carrier territory. A particularly interesting example is [maj] ('berry, fruit'), a loan from Gitksan, which has been borrowed into all Carrier dialects and has displaced the original Athabascan word.

Chinook Jargon

Chinook Jargon originated as a pidgin trade language of the Pacific Northwest, and spread during the 19th century from the lower Columbia River, first to other areas in modern Oregon and Washington, then British Columbia and as far as Alaska, sometimes taking on characteristics of a creole language...

. Loans from French include [liɡok] ('chicken') (from French le coq 'rooster'), [lisel] (from le sel 'salt'), and [lizas] ('angel'). As these examples show, the French article is normally incorporated into the Carrier borrowing. A single loan from Spanish

Spanish language

Spanish , also known as Castilian , is a Romance language in the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several languages and dialects in central-northern Iberia around the 9th century and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castile into central and southern Iberia during the...

is known: [mandah] ('canvas, tarpaulin'), apparently acquired from Spanish-speaking packers.

The trade language Chinook Jargon

Chinook Jargon

Chinook Jargon originated as a pidgin trade language of the Pacific Northwest, and spread during the 19th century from the lower Columbia River, first to other areas in modern Oregon and Washington, then British Columbia and as far as Alaska, sometimes taking on characteristics of a creole language...

came into use among Carrier people as a result of European contact. Most Carrier people never knew Chinook Jargon. It appears to have been known in most areas primarily by men who had spent time freighting on the Fraser River

Fraser River

The Fraser River is the longest river within British Columbia, Canada, rising at Fraser Pass near Mount Robson in the Rocky Mountains and flowing for , into the Strait of Georgia at the city of Vancouver. It is the tenth longest river in Canada...

. Knowledge of Chinook Jargon may have been more common in the southwestern

part of Carrier country due to its use at Bella Coola

Bella Coola

Bella Coola may refer to several things, all closely related to a geographic area within British Columbia's Central Coast:*The Nuxalk, an indigenous people of the area who in the past had been referred to as the Bella Coola...

. The southwestern dialects have more loans from Chinook Jargon than other dialects. For example, while most dialects use the Cree loan described above for "money", the southwestern dialects use [tʃikəmin], which is from Chinook Jargon. The word [daji] ('chief') is a loan from Chinook Jargon.

European contact brought many new objects and ideas. The names for some were borrowed, but in most cases terms have been created using the morphological resources of the language, or by extending or shifting the meaning of existing terms. Thus, [tɬʼuɬ] now means not only "rope" but also "wire", while [kʼa] has shifted from its original meaning of "arrow" to mean "cartridge" and [ʔəɬtih] has shifted from "bow" to "rifle". [hutʼəp], originally "leeches" now also means "pasta".

A microwave oven is referred to as [ʔa benəlwəs] ('that by means of which things are warmed quickly'). "Mustard" is [tsʼudənetsan] ('children's feces'), presumably after the texture and color rather than the flavor.

Status

Like most of the languages of British ColumbiaBritish Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost of Canada's provinces and is known for its natural beauty, as reflected in its Latin motto, Splendor sine occasu . Its name was chosen by Queen Victoria in 1858...

, Carrier is an endangered language

Endangered language

An endangered language is a language that is at risk of falling out of use. If it loses all its native speakers, it becomes a dead language. If eventually no one speaks the language at all it becomes an "extinct language"....

. Only about 10% of Dakelh people now speak the Carrier language, hardly any of them children. Members of the generation following that of the last speakers can often understand the language but they do not contribute to its transmission.

Carrier is taught as a second language in both public and band schools throughout Carrier

territory. This instruction provides an acquaintance with the language but has not proven effective in producing functional knowledge of the language. Carrier has also been taught at the University of Northern British Columbia

University of Northern British Columbia

The University of Northern British Columbia is a small, primarily undergraduate university whose main campus is in Prince George, British Columbia. UNBC also has regional campuses in the northern British Columbia cities of Prince Rupert, Terrace, Quesnel, and Fort St. John...

, the College of New Caledonia

College of New Caledonia

The College of New Caledonia is a post-secondary educational institution that serves the residents of the Central Interior of British Columbia. The college was established in Prince George, British Columbia, Canada in 1969 as a successor to the BC Vocational School. The first convocation of 37...

, and the University of British Columbia

University of British Columbia

The University of British Columbia is a public research university. UBC’s two main campuses are situated in Vancouver and in Kelowna in the Okanagan Valley...

.

The Yinka Dene Language Institute

Yinka Dene Language Institute

The Yinka Dene Language Institute is an organization based in Stoney Creek, British Columbia, whose purpose is the study and maintenance of the language and culture of Dakelh and other First Nations people in northern British Columbia.-History:...

(YDLI) is charged with the maintenance and promotion of Carrier language and culture. Its activities include research, archiving, curriculum development, teacher training, literacy instruction, and production of teaching and reference materials. Prior to the founding of YDLI in 1988 the Carrier Linguistic Committee, a group based in Fort Saint James affiliated with the Summer Institute of Linguistics, produced a number of publications in Carrier, literacy materials for several dialects, a 3000-entry dictionary of the Stuart Lake dialect, and various other materials. The Carrier Linguistic Committee is largely responsible for literacy among younger speakers of the language. The Carrier Bible Translation Committee produced a translation of the New Testament that was published in 1995. An adaptation to Blackwater dialect appeared in 2002.

Place names in Carrier

Here are the Carrier names for some of the major places in Carrier territory, written in the Carrier Linguistic Committee writing system:- Mount Pope – Nak'al

- Fort St. James – Nak'azdli

- Stuart LakeStuart LakeStuart Lake, or Nak'albun in the Carrier language is a lake situated in the Northern Interior of British Columbia, Canada. The town of Fort St. James is situated by the lake near the outlet...

– Nak'albun - Stuart RiverStuart RiverThe Stuart River is a river in northeastern British Columbia, Canada. The river flows over from Stuart Lake to its junction with the Nechako River. The river drains a portion of the Nechako Plateau — a gently-rolling region characterized by small lakes and tributaries...

– Nak'alkoh - Fraser Lake – Nadlehbun

- Nautley RiverNautley RiverNautley River drains Fraser Lake into the Nechako River in the Central Interior of British Columbia, Canada.Only 800m in length, it is the shortest river in the province and one of the shortest rivers in the world, along with Powell River, the Wannock River at Rivers Inlet, and the Little River...

– Nadlehkoh - Endako River – Ndakoh

- Stellako River – Stellakoh

- Tachie River – Duzdlikoh

- Nechako RiverNechako RiverThe Nechako River arises on the Nechako Plateau east of the Kitimat Ranges of the Coast Mountains of British Columbia and flows north toward Fort Fraser, then east to Prince George where it enters the Fraser River...

– Nechakoh - Fraser RiverFraser RiverThe Fraser River is the longest river within British Columbia, Canada, rising at Fraser Pass near Mount Robson in the Rocky Mountains and flowing for , into the Strait of Georgia at the city of Vancouver. It is the tenth longest river in Canada...

– Lhtakoh - Babine LakeBabine LakeBabine Lake is the longest natural lake in British Columbia, Canada.Babine Lake is located northeast of the town of Burns Lake in central British Columbia, some west northwest of the city of Prince George. It is long, wide, and has a net area of and a total area of...

– Nadobun - Burns Lake – Tselhk'azkoh

- Francois LakeFrancois LakeFrançois Lake is a lake located in British Columbia about 30 kilometers south of Burns Lake and 10 kilometers west of Fraser Lake. The lake is 110 kilometers long and is the second longest natural lake entirely within British Columbia after Babine Lake. Nadina River is the inflow of the lake at the...

– Nedabun - Cluculz Lake – Lhoohk'uz

Attestation

The earliest record of the language consists of a list of 25 words recorded by Alexander MacKenzie on June 22, 1793. This is followed by a few Carrier words mentioned in the journal of Simon FraserSimon Fraser (explorer)

Simon Fraser was a fur trader and an explorer who charted much of what is now the Canadian province of British Columbia. Fraser was employed by the Montreal-based North West Company. By 1805, he had been put in charge of all the company's operations west of the Rocky Mountains...

for the year 1806 and by a list of over 300 words given in an appendix to his journal by Daniel Harmon

Daniel Williams Harmon

Daniel Williams Harmon was a fur trader and diarist.Harmon was born in Bennington, Vermont on February 19, 1778, son of Daniel and Lucretia Harmon and died April 23, 1843, in Sault-au-Récollet , Lower Canada. He took as a common-law wife Elizabeth Laval or Duval Daniel Williams Harmon (February...

, published in 1820. The first known text by native speakers of Carrier is the Barkerville Jail Text of 1885.

External links

- The Yinka Dene Language Institute Website contains extensive information about the Carrier language and other First Nations languages of British Columbia.

- The Carrier Sekani Tribal Council represents many of the Carrier bands. Its web site contains information about the tribe and about current political issues.

- Map of Northwest Coast First Nations Note, however, that the Carrier-speaking region is marked incorrectly on this map. The area around Babine Lake and Takla Lake, included in the Dakelh region on the map, is actually Babine speaking. A correct map would attach the Babine and Takla Lake areas to what is shown on this map as "Wet'suwet'en" and label the combination "Babine-Witsuwit'en".

- Ethnologue entry

- Words from the west (Language Log)