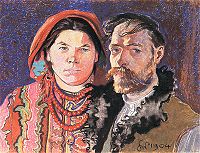

Chłopomania

Encyclopedia

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

portmanteau of a Polish language

Polish language

Polish is a language of the Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages, used throughout Poland and by Polish minorities in other countries...

word for a peasant

Peasant

A peasant is an agricultural worker who generally tend to be poor and homeless-Etymology:The word is derived from 15th century French païsant meaning one from the pays, or countryside, ultimately from the Latin pagus, or outlying administrative district.- Position in society :Peasants typically...

(chłop) and mania

Mania

Mania, the presence of which is a criterion for certain psychiatric diagnoses, is a state of abnormally elevated or irritable mood, arousal, and/ or energy levels. In a sense, it is the opposite of depression...

, the equivalent for the Ukrainian language

Ukrainian language

Ukrainian is a language of the East Slavic subgroup of the Slavic languages. It is the official state language of Ukraine. Written Ukrainian uses a variant of the Cyrillic alphabet....

Khlopomanstvo (Хлопоманство). As a historical and literary term, inspired by the Young Poland

Young Poland

Young Poland is a modernist period in Polish visual arts, literature and music, covering roughly the years between 1890 and 1918. It was a result of strong aesthetic opposition to the ideas of Positivism...

modernist

Modernism

Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society...

movement, it refers specifically to late 19th century Galician intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

's fascination and interest in the local peasantry. Although the term itself was originally used in jest, with time the renewed interest in the folk traditions had an impact onto national revival

Romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism is the form of nationalism in which the state derives its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs...

in Polish and Ukrainian societies. The phenomenon, a manifestation of both neo-romanticism

Neo-romanticism

The term neo-romanticism is used to cover a variety of movements in music, painting and architecture. It has been used with reference to very late 19th century and early 20th century composers such as Gustav Mahler particularly by Carl Dahlhaus who uses it as synonymous with late Romanticism...

and populism

Populism

Populism can be defined as an ideology, political philosophy, or type of discourse. Generally, a common theme compares "the people" against "the elite", and urges social and political system changes. It can also be defined as a rhetorical style employed by members of various political or social...

, overlapped with Galicia's incorporation into Austria–Hungary, and touched both Poles

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

and Ukrainians

Ukrainians

Ukrainians are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine, which is the sixth-largest nation in Europe. The Constitution of Ukraine applies the term 'Ukrainians' to all its citizens...

. It also manifested itself inside the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

, where it mostly contributed to shaping modern Ukrainian culture.

History

The political situation of the region led many intellectuals (Poles and Ukrainians) to believe that the only alternative to decadenceDecadence

Decadence can refer to a personal trait, or to the state of a society . Used to describe a person's lifestyle. Concise Oxford Dictionary: "a luxurious self-indulgence"...

is getting back to the folk roots: moving out of large cities and mixing with "simple men". Focusing on chłopomania within Polish culture, Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

n literary historian Constantin Geambaşu argues: "Initially, the Cracovian

Kraków

Kraków also Krakow, or Cracow , is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century. Kraków has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life...

bohemians

Bohemianism

Bohemianism is the practice of an unconventional lifestyle, often in the company of like-minded people, with few permanent ties, involving musical, artistic or literary pursuits...

' interest in the village followed purely artistic goals. Preoccupied with the idea of national freedom, the democratic Polish intellectuals were made aware of the necessity to attract and enlist the peasantry's potential in view of [Poland's] independence movement

Polish resistance movement during the partitions

Polish resistance movement during the partitions refers to the resistance movement in partitioned Poland . Although some of the szlachta was reconciled to the end of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, the possibility of Polish independence was kept alive by events within and without Poland...

. The notion of social solidarity is formed and consolidated as a solution to overcome the impasse faced by Polish society, especially given the failure of the January 1863 insurrection

January Uprising

The January Uprising was an uprising in the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth against the Russian Empire...

."

Chłopomania spread into Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia is a region in Eastern Europe, mostly located in western Ukraine's Zakarpattia Oblast , with smaller parts in easternmost Slovakia , Poland's Lemkovyna and Romanian Maramureş.It is...

and the Russian Empire, touching the westernmost parts of Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

(Right-bank Ukraine

Right-bank Ukraine

Right-bank Ukraine , a historical name of a part of Ukraine on the right bank of the Dnieper River, corresponding with modern-day oblasts of Volyn, Rivne, Vinnitsa, Zhytomyr, Kirovohrad and Kiev, as well as part of Cherkasy and Ternopil...

, Podolia

Podolia

The region of Podolia is an historical region in the west-central and south-west portions of present-day Ukraine, corresponding to Khmelnytskyi Oblast and Vinnytsia Oblast. Northern Transnistria, in Moldova, is also a part of Podolia...

etc.). This section of the movement merged into the larger Ukrainophile current, which brought together partisans and sympathizers of Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism

Ukrainian nationalism refers to the Ukrainian version of nationalism.Although the current Ukrainian state emerged fairly recently, some historians, such as Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, Orest Subtelny and Paul Magosci have cited the medieval state of Kievan Rus' as an early precedents of specifically...

irrespective of cultural or ethnic background. Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

n scholar Aleksei I. Miller defines the social makeup of some chłopomania groups (whose members are known as chłopomani or khlopomany) in terms of reversed acculturation

Acculturation

Acculturation explains the process of cultural and psychological change that results following meeting between cultures. The effects of acculturation can be seen at multiple levels in both interacting cultures. At the group level, acculturation often results in changes to culture, customs, and...

: "Khlopomany were young people from Polish or traditionally Polonized

Polonization

Polonization was the acquisition or imposition of elements of Polish culture, in particular, Polish language, as experienced in some historic periods by non-Polish populations of territories controlled or substantially influenced by Poland...

families who, due to their populist convictions, rejected social and cultural belonging to their stratum and strove to approach the local peasantry." Similarly, Canadian

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

researcher John-Paul Himka describes the Ukrainian chłopomani as "primarily Poles of Right Bank Ukraine", noting that their contribution was in line with a tradition of "Ukrainophile" cooperation against the Russians

Russians

The Russian people are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Russia, speaking the Russian language and primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries....

and the Russophiles

Ukrainian Russophiles

The focus of this article is part of a general political movement in Western Ukraine of the nineteenth and early 20th century. The movement contained several competing branches: Moscowphiles, Ukrainophiles, Rusynphiles, and others....

. In reference to the cultural crossover between the two ethnic versions of chłopomania, French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

historian Daniel Beauvois noted that "in certain numbers", chłopomani from within the Polish gentry contributed to "reinforcing the Ukrainian movement". Miller however focuses on the movement's role in exacerbating tensions between Ukrainians, Poles and the Russian administrators. He writes: "The government could not but rejoice at the fact that some khlopomany renounced their Catholic faith

Roman Catholicism in Ukraine

The Roman Catholic Church in Ukraine is part of the worldwide Roman Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope and curia in Rome. The present Archbishop is Mieczysław Mokrzycki ....

, converted to Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church, is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece,...

, and refused to support the Polish national movement. However, the Polish ill-wishers were quick to draw the government's attention to the subversive flavor of the khlopomanys social views and their pro-Ukrainophile orientation. The authorities were more often than not inclined to pay heed to these accusations, being guided more by the instinct of social solidarity with Polish landowners than by the strategy of national confrontation with the Poles."

According to Himka, the earliest chłopomani, active in the early 1860s, included Paulin Święcicki

Paulin Święcicki

Paulin Święcicki was a Polish writer, journalist, playwright and translator. Active in Austro-Hungarian Galicia, he was one of key figures in Ukrainian national revival. He is mostly known as a founder and editor-in-chief of a Polish-Ukrainian Sioło monthly...

, who dedicated much of his career to advancing the Ukrainian cause. Among the best-known representatives of this circle of intellectuals are Stanisław Wyspiański (whose The Wedding

The Wedding (1901 play)

The Wedding is a defining work of Polish drama written at the turn of the 20th century by Stanisław Wyspiański. It describes the perils of the national drive toward self-determination following the two unsuccessful uprisings against the Partitions of Poland, in November 1830 and January 1863...

is occasionally associated with chłopomania as its standard manifesto). In 1900 Wyspiański married the mother of his four children Teodora Pytko from a village near Kraków. In November of the same year he participated in the peasant wedding of his friend, poet Lucjan Rydel

Lucjan Rydel

Lucjan Rydel a.k.a. Lucjan Antoni Feliks Rydel , was a Polish playwright and poet from the Young Poland movement.-Life:...

in Bronowice. Other prominent figures include intellectuals associated with the Ukrainian magazine Osnova

Osnova

The Ukrainian magazine Osnova was published in 1861-1862 in St Petersburg. It contained articles devoted to life and customs of the Ukrainian people, including regular features about their wedding costumes and traditions...

, primarily Volodymyr Antonovych

Volodymyr Antonovych

Volodymyr Antonovych , was a prominent Ukrainian historian and one of the leaders of the Ukrainian national awakening in the Russian Empire. As a historian, Antonovych, who was longtime Professor of History at the University of Kiev, represented a populist approach to Ukrainian history.This...

and Tadei Rylsky, as well as poet Pavlo Chubynsky

Pavlo Chubynsky

Pavlo Chubynsky was a Ukrainian poet and ethnographer whose poem "Shche ne vmerla Ukraina" was set to music and adapted as the Ukrainian national anthem....

.

Scholars have noted links between chłopomania and currents emerging in regions neighboring Galicia, both inside and outside Austria–Hungary. Literary historian John Neubauer described it as part of late 19th century "populist strains" in the literature of East-Central Europe

East-Central Europe

East-Central Europe – a term defining the countries located between German-speaking countries and Russia. Those lands are described as situated “between two”: between two worlds, between two stages, between two futures...

, in close connection to the agrarianist

Agrarianism

Agrarianism has two common meanings. The first meaning refers to a social philosophy or political philosophy which values rural society as superior to urban society, the independent farmer as superior to the paid worker, and sees farming as a way of life that can shape the ideal social values...

Głos

Głos (1886–1905)

Głos was a Polish language social, literary and political weekly review published in Warsaw between 1886 and 1905. It was one of the leading journals of the Polish positivist movement. Many of the most renowned Polish writers published their novels in Głos, which also became a tribune of the...

magazine (published in Congress Poland

Congress Poland

The Kingdom of Poland , informally known as Congress Poland , created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, was a personal union of the Russian parcel of Poland with the Russian Empire...

) and with the ideas of Estonia

Estonia

Estonia , officially the Republic of Estonia , is a state in the Baltic region of Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea, to the south by Latvia , and to the east by Lake Peipsi and the Russian Federation . Across the Baltic Sea lies...

n cultural activists Jaan Tõnisson

Jaan Tõnisson

Jaan Tõnisson VR I/3, II/3 and III/1 was an Estonian statesman, serving as the Prime Minister of Estonia twice during 1919 to 1920 and as the Foreign Minister of Estonia from 1931 to 1932.-Early life:...

and Villem Reiman. Neubauer also traces the inspiration of chłopomania to Władysław Reymont and his Nobel

Nobel Prize in Literature

Since 1901, the Nobel Prize in Literature has been awarded annually to an author from any country who has, in the words from the will of Alfred Nobel, produced "in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction"...

-winning Chłopi novel, as well as seeing it manifested in the work of Young Poland authors such as Jan Kasprowicz

Jan Kasprowicz

Jan Kasprowicz was a poet, playwright, critic and translator; a foremost representative of Young Poland.-Life:...

. According to Beauvois, the participation of various Poles in the Ukrainian branch of the movement was later echoed in the actions of Stanisław Stempowski

Stanisław Stempowski

Stanisław Stempowski was a Polish-Ukrainian politician and Grand Master of the National Grand Lodge of Poland.Born in Huta Czernielewiecka, Podolia , he was educated in Krzemieniec and studied in Dorpat ....

, who, although a Pole, invested in improving the living standard of Ukrainian peasants in Podolia

Podolia

The region of Podolia is an historical region in the west-central and south-west portions of present-day Ukraine, corresponding to Khmelnytskyi Oblast and Vinnytsia Oblast. Northern Transnistria, in Moldova, is also a part of Podolia...

. Miller also notes that the movement had echoes in areas of the Russian Empire other than Congress Poland and Ukraine, highlighting one parallel, "albeit of a much lesser dimension", in what later became Belarus

Belarus

Belarus , officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, bordered clockwise by Russia to the northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Its capital is Minsk; other major cities include Brest, Grodno , Gomel ,...

. The notion of chłopomania was specifically linked by Geambaşu with the Sămănătorist

Sămănătorul

Sămănătorul or Semănătorul was a literary and political magazine published in Romania between 1901 and 1910. Founded by poets Alexandru Vlahuţă and George Coşbuc, it is primarily remembered as a tribune for early 20th century traditionalism, neoromanticism and ethnic nationalism...

and Poporanist

Poporanism

The word “poporanism” is derived from “popor”, meaning “people” in the Romanian language. The ideology of Romanian Populism and poporanism are interchangeable. Founded by Constantin Stere in the early 1890s, populism is distinguished by its opposition to socialism, promotion of voting rights for...

currents cultivated by ethnic Romanian

Romanians

The Romanians are an ethnic group native to Romania, who speak Romanian; they are the majority inhabitants of Romania....

intellectuals from the Kingdom of Romania

Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania was the Romanian state based on a form of parliamentary monarchy between 13 March 1881 and 30 December 1947, specified by the first three Constitutions of Romania...

and Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

.