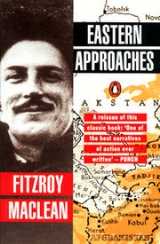

Eastern Approaches

Encyclopedia

Eastern Approaches is an autobiographical account of the early career of Fitzroy Maclean. It is divided into three parts: his life as a junior diplomat in Moscow

and his travels in the Soviet Union

, especially the forbidden zones of Central Asia

; his exploits in the British Army

and SAS

in the North Africa theatre of war; and his time with Josip Broz Tito

and the Partisans in Yugoslavia

.

Maclean was considered to be one of the inspirations for James Bond

, and this book contains many of the elements: remote travel, the sybaritic delights of diplomatic life, violence and adventure. The American edition was titled Escape To Adventure, and was published a year later. All place names in this article use the spelling in the book.

embassy. He loved the pleasures of life in the French capital, but eventually longed for adventure. Against the advice of his friends (and to the delight of his London bosses), he requested a posting to Moscow

, which he received right away; once there, he began to learn Russian

. Travelling within the Soviet Union

was frowned upon by the authorities, but Maclean managed to take several trips anyway.

on the Caspian Sea

. The Intourist

official tried to dissuade him, but he found a ship to take him to Lenkoran (Lankaran

, Azerbaijan), where he witnessed the deportation of several hundred Turko-Tartar

peasants to Central Asia

. Stuck there for a few days, he bargained for horses with which to explore the countryside, and was arrested by the NKVD

cavalry near to the Persian border. He explained that he held diplomatic immunity

, but his captors could not read his Soviet diplomatic pass. Eventually, as the only person literate in Russian, Maclean "read out, with considerable expression, and such improvements as occurred to me" the contents of his pass, and was set free. He took an 1856 paddle steamer

back to Baku, and then a train on to Tiflis (Tbilisi

, Georgia). British troops had supported the Democratic Republic

after World War I

, and Maclean sought out the British war cemetery

, in the process discovering an English governess who had lived in the town since 1912. He caught a truck through the Caucasus mountains

, via Mtzkhet (Mtskheta

), the former capital of Georgia but by then merely a village, to Vladikavkaz

(capital of North Ossetia

), and then a train to Moscow.

. Although he disembarked without warning at Novosibirsk

, he acquired an NKVD escort. He travelled on the Turksib Railway

south to Biisk (Biysk

), at the foot of the Altai Mountains, and then to Altaisk

and Barnaul

. On the trains he heard the complaints of the Siberian kolkhoz

niks (workers on collective farms) and witnessed another mass movement, this time of Koreans to Central Asia

. His first main destination was Alma Ata (Almaty

), the capital of the Kazakh republic, which lies near to the Tien Shan Mountains. He characterised it as "one of the pleasantest provincial towns in the Soviet Union" and particularly appreciated the apples for which it is famous. From there he took a truck to a hill village called Talgar

and went walking with one of his NKVD escort; Maclean availed himself of peasant hospitality and commented on the general prosperity. He managed to hire a car and made it to Issyk-kul, the lake that never freezes, but had to turn back because of the season. From Alma Ata Maclean took the train for Tashkent

, passing through villages where "nothing seemed to have changed since the time when the country was ruled over by the Emir of Bokhara"; men still rode bulls and women still wore veils made of black horsehair. From Tashkent, which then had a reputation for wickedness, he made the final leg to the fabled city of Samarkand

. He returned to Moscow with plans for a further trip.

Maclean spent the winter working in Moscow and amusing himself at the dacha

(country cottage) of American friends, including Chip Bohlen

. In March 1938 a show trial

was announced, the first such public event in over a year; he attended every day of what became known as the Trial of the Twenty-One. The book goes into great detail, spending 40 pages on description and analysis of the trial, its prominent figures and its twists and turns.

), the capital of the province of Sinkiang (Xinjiang

), which had fallen under Soviet influence. He was commissioned to talk to the tupan

(provincial governor) there about the situation of both the consul-general and the British Indian traders. The first stage was retracing his steps on a five-day train journey to Alma Ata; the train ran via Orenburg

and the Aral Sea

, then parallel to the Syr Darya

and the mountains of Kirghizia (Kyrgyzstan

). From Alma Aty he travelled four hundred miles north through the Hungry Steppe to Ayaguz (Ayagoz), where "a road which had been made, and was being kept up, for a very definite purpose" lay to the frontier town of Bakhti (Bakhty or Bakhtu, about 17 km from Tacheng

, known in Maclean's time as Chuguchak). The Soviet officials were, at first, willing to assist him but the Chinese ones were not, and in the course of the negotiations that surrounded his passage, Maclean discovered that the Soviets exercised some influence over at least the consul if not the provincial government of their neighbours. He crossed the border into China

, where he was refused permission to continue; he was forced to return to Alma Aty, whence he was expelled. Soon he found himself back in Moscow.

, Uzbekistan

), the capital of the emirate which had been closed to Europeans until recent times. Maclean recounts how Charles Stoddart

and Arthur Conolly

were executed there in the context of The Great Game

, and how Joseph Wolff

, known as the Eccentric Missionary, barely escaped their fate when he came looking for them in 1845. In early October 1938 Maclean set out again, first for Ashkhabad (Ashgabat, capital of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic), then through the Kara Kum (Black Desert), not breaking his journey at either Tashkent or Samarkand, but pushing on to Kagan

, the nearest point on the railway to Bokhara. After trying to smuggle himself aboard a lorry transporting cotton, he ended up walking to the city, and spent several days sight-seeing "in the steps of the Eccentric Missionary" and sleeping in parks, much to the frustration of the NKVD spies who were shadowing him. He judged it an "enchanted city", with buildings that rivalled "the finest architecture of the Italian Renaissance

". Aware of his limited time, he cut short his wanderings and took the train towards Stalinabad (Dushanbe

, the capital of Tajikistan

), disembarking at Termez

. This town sits on the Amu Darya

(the Oxus), and the other side of the river lies in Afghanistan

. Maclean claimed that "very few Europeans except Soviet frontier guards have ever seen it at this or any other point of its course". After more negotiations, he managed to cross the river and thus leave the USSR, and from that point his only guide seems to have been the narrative of "the Russian Burnaby

", a colonel Nikolai Ivanovich Grodekov, who rode from Samarkand to Mazar-i-Sharif and Herat

in 1878. The following day he and a guide set out on horseback, riding through jungle and desert, and detained on the way by dubious characters who may or may not have been brigands. (Maclean, a proficient linguist, was hamstrung on entering Afghanistan by the lack of any lingua franca

.) They rode past the ruins of Balkh

, a civilization founded by Alexander the Great and destroyed by Genghis Khan

. After a night in Mazar, Maclean managed to get a car and driver, and progressed as rapidly as he could to Doaba, a village half-way to Kabul

, where he had arranged to meet the British minister

(i.e., ambassador), Colonel Frazer-Tytler. Together, they returned to the capital via Bamyan and its famous statues

. Maclean circled back to Moscow via Peshawar

, Delhi

, Baghdad

, Persia, and Armenia

.

. He was invited to join the newly formed Special Air Service

(SAS), where, as part of the Western Desert Campaign

, he planned and executed raids on Axis-held Benghazi

, on the coast of Libya

. When it became clear that the North African Campaign

was drawing to a close towards the end of 1942 and it became too quiet for his taste, he travelled east to arrest General Fazlollah Zahedi

, at the time the head of the Persian armed forces

in the south.

, so he was not allowed to enlist. The only way around this was to go into politics, and on this stated ground Maclean tendered his resignation in 1941 to Alexander Cadogan, an FO mandarin

. When his erstwhile employers discovered this to be merely a ruse or legal fiction

along the lines of taking the Chiltern Hundreds

, he was forced to run for office and, despite his self-confessed inexperience, was chosen as a Conservative candidate, and eventually elected MP. Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

jocularly accused him of using "the Mother of Parliaments as a public convenience". In the meantime, Maclean had immediately enlisted, taking a taxi from Sir Alexander's office to a nearby recruiting station, where he joined the Cameron Highlanders

, his father's regiment, as a private

.

, where David Stirling

invited him to join the newly formed Special Air Service

(SAS), which he did. They worked closely with the Long Range Desert Group

(LRDG), a mechanised reconnaissance unit, to travel far behind enemy lines and attack targets such as aerodromes. Maclean's first operation with the SAS, once his training was completed, was to Benghazi

, Libya

's second largest city, in late May 1942. He was joined on this operation by Randolph Churchill

, son of the prime minister. They drove from Alexandria

via the seaport of Mersa Matruh and the inland Siwa Oasis

. They crossed the ancient caravan route known as the Trigh-el-Abd, which the enemy had laced with little bombs, and camped in the Gebel Akhdar, the Green Mountain just inland from the coastal plain. Once inside the occupied city, their patrol came face to face with Italian soldiers several times; Maclean, with his excellent Italian, managed to bluff his way out of all of these encounters by pretending to be a staff officer. They spent two nights and a day in the city. They had hoped to sabotage ships, but both the rubber boats

they had brought with them failed to inflate, so they treated the visit as a reconnaissance

mission. The drive back was uneventful, but nearing Cairo, Maclean, along with most of his party, was seriously injured in a crash and spent months out of action.

Once he had recovered, Stirling involved him in preparations for a larger SAS attack on Benghazi. They attended a dinner with Churchill, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff General Alan Brooke

, and General Harold Alexander

, who was about to assume control of Middle East Command

, the post responsible for the overall conduct of the campaign in the North African desert

. Four operations were designed to create a diversion from Rommel

's attempt on El Alamein

: attacks on Benghazi, Tobruk

, Barce, and the Jalo oasis

. These all started out from Kufra

, an oasis 800 miles inland. Maclean's convoy drove to the Gebel across the Sand Sea

at its narrowest point, Zighen, and made it there undetected, although "bazaar gossip" from an Arab spy indicated that the enemy expected an imminent attack. When Maclean's group reached the outskirts of Benghazi, they were ambushed and had to retreat. Axis planes repeatedly bombed them, destroying many of the vehicles and most of their supplies. Thus began a painful limp of days and nights over the desert towards Jalo, without even knowing whether that oasis was in Allied hands. They existed on rations of "a cup of water and a tablespoon of bully beef a day.... We found ourselves looking forward to the evening meal with painful fixity". When they got to that oasis, they found a battle going on between the Italian defenders and the Sudan Defence Force

, and despite their offers to help, they received orders from GHQ to abandon the assault. Some days later they made it back to Kufra.

, where General Wilson

, the new head of Persia and Iraq Command

, wanted his advice about starting something like the SAS in Persia, should that country fall to the Germans. He proceeded there to recruit volunteers, passing through many of the places he had seen in peacetime four years earlier: Kermanshah

, Hamadan

, Kazvin, Teheran. He was soon diverted to a more urgent task. General Joseph Baillon

, the Chief of Staff

, and Reader Bullard

, the minister (i.e., ambassador, as above), summoned him to Teheran. They were concerned about the influence of Fazlollah Zahedi

, the general in charge of the Persian forces

in the Isfahan area, who, their intelligence told them, was stockpiling grain, liaising with German agents, and preparing an uprising. Baillon and Bullard asked Maclean to remove Zahidi alive and without creating a fuss. He devised a Trojan horse

plan: he and a senior officer would call on Zahidi to pay their respects, and then arrest him "at the point of a pistol" within his walled and guarded residence. He would be whisked out in the British staff car

, driven a waiting plane, and flown into internment

and exile. Maclean obtained and trained a platoon of Seaforth Highlanders

to cover his retreat, and the plan went according to clockwork. (Zahidi spent the rest of the war in British Palestine; five years later he was back in charge of the military of southern Persia, by 1953 he was prime minister.)

By the end of the year, the war had developed in such a way that the new SAS detachment would not be needed in Persia. General Wilson was being transferred to Middle East Command

, and Maclean extracted a promise that the newly trained troops would go with him, as their style of commando raids were ideal for southern and eastern Europe. Frustrated by the abandoning of plans for an assault on Crete

, Maclean went to see Reginald Leeper

, "an old friend from Foreign Office days, and now His Majesty's Ambassador to the Greek Government then in exile

in Cairo". Leeper put in a word for him, and very soon Maclean was told to go to London to get his instructions directly from the prime minister. Churchill told him to parachute into Jugoslavia (now spelled Yugoslavia

) as head of a military mission accredited to Josip Broz Tito

(a shadowy figure at that point) or whoever was in charge of the Partisans, the Communist-led resistance movement

. Mihajlovic

's royalist Cetniks

(now spelled Chetniks), which the Allies had been supporting, did not appear to be fighting the Germans very hard, and indeed were said to be collaborating with the enemy. Maclean famously paraphrased Churchill: "My task was simply to help find out who was killing the most Germans and suggest means by which we could help them to kill more." The prime minister saw Maclean as "a daring Ambassador-leader to these hardy and hunted guerillas".

.

(whom he called his British and American Chiefs of Staff, respectively) and Sergeant Duncan, his bodyguard. They were attached to Tito's headquarters, then in the ruined castle of Jajce

. Here and elsewhere, Maclean lived in proximity to the Partisan leader for a year and a half, on and off. Maclean gives much of this section of the book to his personal assessment of the Partisan position and of Tito as a man and as a leader. Their talks, in German and Russian (while Maclean learned Serbo-Croat), were wide-ranging, and from them Maclean gained hope that a future Communist Yugoslavia might not be the fear-wracked place the USSR was. The Partisans were extremely proud of their movement, dedicated to it, and prepared to live a life of austerity in its cause. All of this won his admiration.

Some of the characters close to Tito whom Maclean met in his first months in Bosnia were Vlatko Velebit, an urbane young man about town, who later went with Maclean to Allied HQ as a liaison officer; Father Vlado (Vlado Zechevich), a Serbian Orthodox priest

, "raconteur and trencherman"; Arso Jovanović

, the Chief of Staff; Edo Kardelj

, the Marxist theoretician who ended up vice-premier; Aleksandar Ranković

, a professional revolutionary and Party organiser; Milovan Đilas (Dzilas), who became vice-president; Moša Pijade

, one of the highest-ranking Jews; and a young woman named Olga whose father had been a minister in the Royalist government and who spoke English like a debutante.

Other Yugoslavs of note whom he met later included Koča Popović

, later Chief of the General Staff of Yugoslav People's Army

, whom Maclean judged "one of the outstanding figures of the Partisan Movement"; Ivo Lola Ribar

, son of Dr Ivan Ribar

, who seemed destined for great things; Miloje Milojević

; Slavko Rodic; Sreten Žujović

(Crni the Black).

Officers and soldiers under Maclean's command included Peter Moore of the Royal Engineers

; Mike Parker, Deputy Assistant Quartermaster general

; Gordon Alston; John Henniker-Major

, a career diplomat; Donald Knight, and Robin Whetherly.

Maclean arranged for an Allied officer, under his command, to be attached to each of the main Partisan bases, bringing with him a radio transmitting set. Maclean was not in fact the first Allied officer in Yugoslavia, but the few who had been dropped before him had not been able to get much of their information out. Maclean made contact with Bill Deakin

, an Oxford history don who had served as a research assistant to Churchill; Anthony Hunter, a Scots Fusilier

, and Major William Jones, an enthusiastic but unorthodox one-eyed Canadian.

was reluctant to risk landing on what they saw as an amateur airstrip at Glamoj (Glamoč

), although Slim Farish was in fact an airfield designer, and night air drops were sporadic. The Royal Navy

was approached, and they offered to bring supplies to an outlying island off the Dalmatia

n coast. Maclean and a couple of companions set off on foot for Korčula

, being passed from guerilla group to guerilla group. They passed through battle-scarred villages and towns that had changed hands many times, some so recently that corpses still lay on the ground: Bugojno

and Livno

and Aržano

. Once, they were billeted with a landlady whose sympathies clearly did not lie with the Partisans; she would not sell them food, but there was no question of simply commandeering it. Eventually, after an all-night march across noisy stony ground, dodging German patrols as they crossed a major road, the little group reached Zadvarje

, where they were greeted with astonishment as creatures from another world "as indeed in a sense we were". After a few hours' sleep, they continued over the final range of hills to the coast, and down to Baška Voda

, where a fishing boat took them circuitously to Korčula. There, all seemed in order for a Navy supply drop, but the wireless set developed problems. Maclean was on the point of returning to Jajce when the motor launch

arrived, with a crew that included Sandy Glen (also, like Maclean, thought to be one of the inspirations for James Bond

) and David Satow. By this point the enemy were closing in to take the remaining access points to the coast, which would throttle the Partisan supply route before it had even begun. He sent top priority requests, asking for air and sea support from Allied bases in Italy, and these took effect. Maclean decided he needed to discuss matters with Tito and then with Allied superiors in Cairo to argue for more resources to push the project forward, and accordingly made his way back to Partisan HQ in Jajce. He returned to the islands, first on Hvar

and then on Vis

, to wait for the response to his strongly worded signals. On Vis he discovered an overgrown British war cemetery dating from a naval victory over the French

in 1811.

, the Foreign Secretary. He stated his conclusions straight-forwardly: that the Partisans were important militarily and politically and would influence the future of Yugoslavia whether the Allies helped them or not; their impact on the Germans could be greatly increased by Allied support; they were Communist and oriented towards the USSR. He says that his report created "something of a stir". He was sent back to collect two Yugoslav liasison officers who had not been allowed to come out with him on the first Navy pick-up. From Bari

on the Italian Adriatic coast

, now a centre of operations for the Tactical Air Force

, he saw that this would prove difficult, as the German offensive had captured the whole Dalmatian coast. Fortunately, he had asked Air Marshal

Sholto Douglas

to assign him a liaison officer

, and Wing Commander

John Selby proved a godsend. Together they obtained the use of a Baltimore bomber

and an escort of Lightnings

. Twice they set out from Italy on a sunny day and twice the clouds blocked them from the Bosnian hills. On the third day the fighters were unavailable so the bomber set out alone, but again the weather proved impossible to land. On their return to Italy, they received a signal that the Partisans had captured a small German plane that they proposed to use. As they were loading up the plane, an enemy aircraft, alerted by a traitor, bombed the landing strip at Glamoc, killing Whetherly, Knight, and Ribar, and wounding Milojevic. This event, at the end of November, proved a spur to getting the mission higher priority, and soon Maclean got a large Dakota

and half a squadron of Lightnings to complete the landing operation. Milojevic and Velebit accompanied Maclean to Alexandria

, where the Yugoslavs decompressed for a few days, while Maclean sought out the prime minister.

Churchill received him in trademark fashion: in bed, wearing an embroidered dressing gown, smoking a cigar. He, Joseph Stalin

, and Franklin D. Roosevelt

had discussed the matter of Yugoslavia at a recent conference in Teheran

, and had decided to give all possible support to the Partisans. This was the turning point. The Chetniks were given a task (a bridge to blow up) and a deadline, to show whether they could still be effective allies; they failed this test and supplies were re-directed from them to the Partisans. The British government was left with the tricky political and moral problem of King Peter

and his royalist government in exile. But the main issues were air supplies and air support, and to help co-ordinate this, Maclean's mission was expanded. Some of the new officers included Andrew Maxwell of the Scots Guards, John Clarke of the 2nd Scots Guards, Geoffrey Kup, a gunnery expert, Hilary King, a signals officer, Johnny Tregida, and, for a time, Randolph Churchill. Some of these were SAS or otherwise known from the Western Desert Campaign the previous year.

as being the best site for an airstrip and a naval base. He then needed to garrison it. He discussed the matter with General Alexander and his Chief of Staff General John Harding

, who seemed to think it might be possible, and who gave him a lift to Marrakech

to put the matter to the prime minister. Churchill assured him on the point of troops, and wrote a personal letter to Tito which he commissioned Maclean to deliver. Maclean parachuted into Bosnia again, thinking it no longer an unknown, as it had been only six months before. Tito, since the end of November

Marshal of Yugoslavia

, was delighted with the recognition from Churchill, as from one statesman to another.

The Partisan headquarters moved to the village of Drvar

, where Tito took up residence in a cave with a waterfall. Maclean spent months there with him, "talking, eating, and above all, arguing". He and Tito agreed a system of allocating the air drop supplies around the country, although there was some friction from officers wanting a bigger share. Air drops became much more frequent, as did air support for Partisan operations. At this point all support for the Cetniks was withdrawn, a fact Churchill announced in the House of Commons. Maclean decided to go to Serbia

to see for himself what this stronghold of Cetniks held for the Partisans. In early April, before this could be arranged, he was ordered to London

for further discussions. (A stop-over in Algiers

meant a specially arranged radio phone call with Churchill. Maclean, who hated telephone conversations, managed to wring amusement from the mix-ups of codes and scrambling. Churchill's son was referred to as Pippin

.)

They arrived in England to find "the whole of the southern counties [were] one immense armed camp". Despite the tension over the anticipated invasion of Normandy, the press and officials were eager to hear the Yugoslav story, and Maclean and Velebit had a busy time; even U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower

wanted to meet them. At Chequers

Maclean participated in attempts to build a possible compromise between the Royalist government in exile and the Partisans. As Maclean was preparing to go back to Bari and Bosnia, he received news that the enemy had made a fierce attack on Partisan headquarters at Drvar, later known as the Knight's Move. "It was the kind of communication that took your breath away." When he got the full story from Vivian Street, he heard how the German bombers had made a full and thorough attack, and, after Tito and the Partisans escaped, revenged themselves on the civilians, massacring almost everyone, men, women, and children. In the week that followed the attack on Drvar, Allied planes flew more than a thousand sorties in support of the Partisans. Tito, harassed and harried through the woods, reached the decision that he needed to leave and establish his headquarters in a place of security. Accordingly, he asked Vivian Street to arrange for the Allies to evacuate him and his staff, which they did. Maclean, on his way back from London, caught up with the Marshall at Bari, and found him proposing to establish his base on Vis. The Royal Navy took him across in fine style, with a memorable wardroom dinner, at which Tito recited, in English, "The Owl and the Pussycat

".

to Montenegro

". Meanwhile, other fronts of the war were progressing rapidly, and the Germans were hard-pressed. It was necessary to discuss the future shape of Yugoslavia at the highest possible level, and so Maclean was instructed to invite Tito and his entourage to Caserta

, the Allied Force Headquarters near Naples

. Maclean accompanied him on this, his first public appearance outside his own country. While the negotiations wore on, Maclean was told that Churchill would be in Italy in a week and wanted to see the Yugoslav Marshal, but security meant the prime minister's movements could not be released. Maclean helped to spin out Tito's visit with side trips and excuses, taking him to Rome

and Cassino

, "to tea with Hermione Ranfurly

at her ridiculous little house of the side of the hill overlooking the Bay of Naples" and to Capri

to meet Mrs Harrison Williams

. Sitting outside one afternoon, Tito saw a heavy plane and a dozen fighters coming in, and announced that that must be Mr Churchill. Maclean commented wryly, "He was not an easy man to keep anything from".

The negotiations that followed were called the Naples Conference, with Tito, Velebit and Olga on one side of the table and Churchill and Maclean on the other. Churchill was happy to give this matter his personal attention, and, Maclean says, he did it very well. One day the two leaders were taking a rest, having handed things over to a committee of experts, when a matter arose required Churchill's immediate attention. Maclean was sent to find him; he was believed to be bathing in the Bay of Naples. When they got to the shore, they saw the huge flotilla of troopships setting off for the south of France (Operation Dragoon

), and a small bright blue admiral's barge dodging around them. Maclean was assigned a little torpedo boat

, complete with a cautious captain and an attractive stenographer. It zoomed after the barge, eventually catching up with the prime minister, who found Maclean and his crew's arrival a source of much hilarity.

Immediately after the Naples Conference, Tito continued the diplomatic discussions on Vis, this time with Dr Ivan Subasic

, prime minister of the Royal Jugoslav Government, and his colleagues. Ralph Stevenson

, the British Ambassador to this government in exile

, accompanied Subasić to Vis, but he and Maclean stayed out of the negotiations and spent their days swimming and speculating. The two parties came to an agreement, the Treaty of Vis, which, Maclean said, "sounded (and was) too good to be true". To celebrate this, Tito took everyone out in a motor boat to a local beauty spot, an underwater cave

illuminated with sunlight (Biševo

). "We all stripped and bathed, our bodies glistening bluish and ghastly. Almost everyone there was a Cabinet Minister in one or other of the two Jugoslav Governments, and there was much shouting and laughter as one blue and phosphorescent Excellency cannoned into another, bobbing about in that cerulean twilight."

, in which the Partisans and Allies were to harass the Axis troops in close co-ordination for seven days, destroying their communication lines. Bill Elliot

, in command of the Balkan Air Force

, supported the plan, as did the Navy and General Wilson. Tito committed himself too, although, as Maclean points out, it would have been understandable had he wished to let the Germans leave as soon as possible. Maclean got permission from Churchill to go to Serbia

, previously a stronghold of the Chetniks, to supervise Ratweek from there.

He landed at Bojnik

near Radan Mountain

, a position surrounded by Bulgars

, Albanians

, White Russians

, and Germans

. Through the latter part of August he, and his team back in Bari and Caserta, and the Partisans in Serbia and elsewhere, finalised the details of Ratweek. Almost to cue, the White Russians blew up their ammunition dump and the enemy started to retreat. The following day, Maclean moved to near Leskovac

, and the next day, Ratweek began, with fifty heavy bombers attacking the town at 11:30. "Already the Fortresses were over their target -- were past it -- when, as we watched, the whole of Leskovac seemed to rise bodily into the air in a tornado of dust and smoke and debris,and a great rending noise fell on our ears. When we looked at the sky again, the Forts, still relentlessly following their course, were mere silvery dots in the distance. [...] Even the Partisans seemed subdued." That night, the land offensive began, and Maclean watched the Partisans attack the Belgrade-Salonika

railway, blowing up bridges, burning sleepers, and rendering it unusable. When the Germans tried to repair it, the Balkan Air Force soon dissuaded them. They tried to evacuate Greece and Macedonia by air, but again the Allies thwarted them. Maclean, with three British companions and one Yugoslav guide, made his way on horseback north into Serbia. They travelled for several days through prosperous countryside, "so surprising after Bosnia and Dalmatia", where the peasants, who expressed great friendship for Britain and a certain caution about the Partisans, gave them lavish hospitality and food. One evening they camped outside a village, and soon saw "a procession of peasant women arriving with an array of bowls, baskets, jars and bottles. From these they produced eggs and sour milk and fresh bread and a couple of chickens and a roast suckling-pig and cream cheese and pastry and wine and peaches and grapes". The journey produced many such vignettes, some pleasant, others of confusion, discomfort, worry. Altogether Maclean found it "an agreeable existence", reflecting "with heightened distaste" on the life he lived on Vis in the shadow of political negotiations. He hoped he could remain in Serbia to be there when Belgrade was liberated

, but received a message that Tito had disappeared—or as Churchill put it "levanted" -- and he had to try to find him. A plane was sent to pick up Maclean.

with a jeep. It was here that "Lili Marlene", the song broadcast from Radio Belgrade

and which he had listened to night after night, from the desert to the mountain tops, finally ceased. "Not long now," he thought. The Partisan troops travelled through Arandjelovac and soon met up with the Red Army

, who were being hailed as liberators. Maclean noted that almost every one of them was a fighting soldier, and that their vehicles carried nothing but petrol and ammunition. For the rest, he presumed, they got from the enemy or the local people. "We were witnessing a return to the administrative methods of Attila and Genghis Khan

, and the results seemed to deserve careful attention." In the last ten miles outside the capital, they passed hundreds and hundreds of corpses from the recent battle, and a neat stack of a hundred or more who appeared to have been executed. When they reached the HQ of General Peko Dapčević

, his chief of staff, who had only a vague notion of the geography of the city, took Maclean and Vivian Street out for a tour, through heavy shelling that he appeared oblivious to. From the terrace of the Kalemegdan

, the ancient fort in the middle of the city, they witnessed the withdrawal of German troops over the Danube

to the suburb of Zemun

. Inexplicably, the Germans failed to blow up the bridge after the last of their troops were over it, allowing the Russians to follow only minutes behind. Maclean, some time afterwards, found out the answer to this puzzle, comparing it to a fairytale. An old schoolmaster, whose one experience of modern warfare was in the Balkan War of 1912, saw the charges being laid and knew how to disconnect them. He got a gold medal in 1912 and another for this iniative too.

A few days later Tito arrived and Maclean had to convey Churchill's displeasure at his sudden and unexplained departure. Tito had been to Moscow at Stalin's invitation, to arrange matters with the Soviet High Command. Maclean helped to hammer out a draft agreement, and went to London with it, while Tito's envoys took it to Moscow. "It was a difficult and thankless task. King Peter, quite naturally, was not easy to reassure, and Tito, sitting in Belgrade with all the cards in his hand, was not easy to satisfy." The bargaining went on for months, and meanwhile Maclean's staff wanted to get away, to assist guerrilla wars elsewhere. When the Big Three (Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin) met at Yalta

in February 1945, and made it clear that Tio and Subasic had to get on with it, King Peter gave in, and all the pieces fell into place. The regents were sworn in, as was the united government, and the British ambassador flew in. Maclean was finally able to leave.

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

and his travels in the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, especially the forbidden zones of Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia is a core region of the Asian continent from the Caspian Sea in the west, China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, and Russia in the north...

; his exploits in the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

and SAS

Special Air Service

Special Air Service or SAS is a corps of the British Army constituted on 31 May 1950. They are part of the United Kingdom Special Forces and have served as a model for the special forces of many other countries all over the world...

in the North Africa theatre of war; and his time with Josip Broz Tito

Josip Broz Tito

Marshal Josip Broz Tito – 4 May 1980) was a Yugoslav revolutionary and statesman. While his presidency has been criticized as authoritarian, Tito was a popular public figure both in Yugoslavia and abroad, viewed as a unifying symbol for the nations of the Yugoslav federation...

and the Partisans in Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia refers to three political entities that existed successively on the western part of the Balkans during most of the 20th century....

.

Maclean was considered to be one of the inspirations for James Bond

Inspirations for James Bond

A number of real-life inspirations have been suggested for James Bond, the sophisticated fictional character and British spy created by Ian Fleming. Although the Bond stories were often fantasy-driven, they did incorporate some real places, incidents and, occasionally, organisations such as...

, and this book contains many of the elements: remote travel, the sybaritic delights of diplomatic life, violence and adventure. The American edition was titled Escape To Adventure, and was published a year later. All place names in this article use the spelling in the book.

Golden Road: the Soviet Union

Fresh out of Cambridge, Maclean joined the Foreign Office and spent a couple of years at the ParisParis

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

embassy. He loved the pleasures of life in the French capital, but eventually longed for adventure. Against the advice of his friends (and to the delight of his London bosses), he requested a posting to Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

, which he received right away; once there, he began to learn Russian

Russian language

Russian is a Slavic language used primarily in Russia, Belarus, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. It is an unofficial but widely spoken language in Ukraine, Moldova, Latvia, Turkmenistan and Estonia and, to a lesser extent, the other countries that were once constituent republics...

. Travelling within the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

was frowned upon by the authorities, but Maclean managed to take several trips anyway.

The Caucasus

In the spring of 1937, he took a trial trip, heading south from Moscow to BakuBaku

Baku , sometimes spelled as Baki or Bakou, is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. It is located on the southern shore of the Absheron Peninsula, which projects into the Caspian Sea. The city consists of two principal...

on the Caspian Sea

Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the largest enclosed body of water on Earth by area, variously classed as the world's largest lake or a full-fledged sea. The sea has a surface area of and a volume of...

. The Intourist

Intourist

Intourist is a Russian travel agency, 66%-owned by Moscow-based holding company Sistema.Before privatisation in 1992, Intourist was renowned as the official state travel agency of the Soviet Union. It was founded in 1929 by Joseph Stalin and was staffed by NKVD and later KGB officials...

official tried to dissuade him, but he found a ship to take him to Lenkoran (Lankaran

Lankaran

-History:The city was built on a swamp along the northern bank of the river bearing the city's name. There are remains of human settlements in the area dating back to the Neolithic period as well as ruins of fortified villages from the Bronze and Iron Ages. Lankaran's history is rather recent,...

, Azerbaijan), where he witnessed the deportation of several hundred Turko-Tartar

Tatars

Tatars are a Turkic speaking ethnic group , numbering roughly 7 million.The majority of Tatars live in the Russian Federation, with a population of around 5.5 million, about 2 million of which in the republic of Tatarstan.Significant minority populations are found in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan,...

peasants to Central Asia

Central Asia

Central Asia is a core region of the Asian continent from the Caspian Sea in the west, China in the east, Afghanistan in the south, and Russia in the north...

. Stuck there for a few days, he bargained for horses with which to explore the countryside, and was arrested by the NKVD

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs was the public and secret police organization of the Soviet Union that directly executed the rule of power of the Soviets, including political repression, during the era of Joseph Stalin....

cavalry near to the Persian border. He explained that he held diplomatic immunity

Diplomatic immunity

Diplomatic immunity is a form of legal immunity and a policy held between governments that ensures that diplomats are given safe passage and are considered not susceptible to lawsuit or prosecution under the host country's laws...

, but his captors could not read his Soviet diplomatic pass. Eventually, as the only person literate in Russian, Maclean "read out, with considerable expression, and such improvements as occurred to me" the contents of his pass, and was set free. He took an 1856 paddle steamer

Paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or riverboat, powered by a steam engine, using paddle wheels to propel it through the water. In antiquity, Paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, where the first uses were wheelers driven by animals or humans...

back to Baku, and then a train on to Tiflis (Tbilisi

Tbilisi

Tbilisi is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Mt'k'vari River. The name is derived from an early Georgian form T'pilisi and it was officially known as Tiflis until 1936...

, Georgia). British troops had supported the Democratic Republic

Democratic Republic of Georgia

The Democratic Republic of Georgia , 1918–1921, was the first modern establishment of a Republic of Georgia.The DRG was created after the collapse of the Russian Empire that began with the Russian Revolution of 1917...

after World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, and Maclean sought out the British war cemetery

War grave

A war grave is a burial place for soldiers or civilians who died during military campaigns or operations. The term does not only apply to graves: ships sunk during wartime are often considered to be war graves, as are military aircraft that crash into water...

, in the process discovering an English governess who had lived in the town since 1912. He caught a truck through the Caucasus mountains

Caucasus Mountains

The Caucasus Mountains is a mountain system in Eurasia between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea in the Caucasus region .The Caucasus Mountains includes:* the Greater Caucasus Mountain Range and* the Lesser Caucasus Mountains....

, via Mtzkhet (Mtskheta

Mtskheta

Mtskheta , one of the oldest cities of the country of Georgia , is located approximately 20 kilometers north of Tbilisi at the confluence of the Aragvi and Kura rivers. The city is now the administrative centre of the Mtskheta-Mtianeti region...

), the former capital of Georgia but by then merely a village, to Vladikavkaz

Vladikavkaz

-Notable structures:In Vladikavkaz, there is a guyed TV mast, tall, built in 1961, which has six crossbars with gangways in two levels running from the mast structure to the guys.-Twin towns/sister cities:...

(capital of North Ossetia

North Ossetian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic

The North Ossetian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was an autonomous republic of the Soviet Union. Currently it is known as North Ossetia-Alania, a federal subject of Russia....

), and then a train to Moscow.

To Samarkand

His second trip, in the autumn of the same year, took him east along the Trans-Siberian RailwayTrans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway is a network of railways connecting Moscow with the Russian Far East and the Sea of Japan. It is the longest railway in the world...

. Although he disembarked without warning at Novosibirsk

Novosibirsk

Novosibirsk is the third-largest city in Russia, after Moscow and Saint Petersburg, and the largest city of Siberia, with a population of 1,473,737 . It is the administrative center of Novosibirsk Oblast as well as of the Siberian Federal District...

, he acquired an NKVD escort. He travelled on the Turksib Railway

Turkestan-Siberia Railway

The Turkestan–Siberian Railway is a broad gauge railway that connects Central Asia with Siberia. It starts north of Tashkent in Uzbekistan at Arys, where it branches off from the Trans-Caspian Railway. It heads roughly northeast through Shymkent, Taraz, Bishkek to the former Kazakh capital of...

south to Biisk (Biysk

Biysk

Biysk is a city in Altai Krai, Russia. It is the second largest city of the krai . Population: -Geography:Biysk is situated in southwestern Siberia, on the Biya River . The city is called "the gates to the Altai Mountains", because of its position comparatively not far from this range...

), at the foot of the Altai Mountains, and then to Altaisk

Gorno-Altaysk

Gorno-Altaysk is the capital town of the Altai Republic, Russia, situated east of Moscow. Population: This only town of the republic lies in a narrow Mayma Valley in the foothills of the Altay Mountains...

and Barnaul

Barnaul

-Russian Empire:Barnaul was one of the earlier cities established in Siberia. Originally chosen for its proximity to the mineral-rich Altai Mountains and its location on a major river, the site was founded by the wealthy Demidov family in the 1730s. In addition to the copper which had originally...

. On the trains he heard the complaints of the Siberian kolkhoz

Kolkhoz

A kolkhoz , plural kolkhozy, was a form of collective farming in the Soviet Union that existed along with state farms . The word is a contraction of коллекти́вное хозя́йство, or "collective farm", while sovkhoz is a contraction of советское хозяйство...

niks (workers on collective farms) and witnessed another mass movement, this time of Koreans to Central Asia

Deportation of Koreans in the Soviet Union

Deportation of Koreans in the Soviet Union, originally conceived in 1926, initiated in 1930, and carried through in 1937, was the first mass transfer of an entire nationality based on their ethnicity to be committed by the Soviet Union...

. His first main destination was Alma Ata (Almaty

Almaty

Almaty , also known by its former names Verny and Alma-Ata , is the former capital of Kazakhstan and the nation's largest city, with a population of 1,348,500...

), the capital of the Kazakh republic, which lies near to the Tien Shan Mountains. He characterised it as "one of the pleasantest provincial towns in the Soviet Union" and particularly appreciated the apples for which it is famous. From there he took a truck to a hill village called Talgar

Talgar

-Talgar Mountains:Talgar mountains is an informal name for a north-western part of Zailiisky Alatau adjacent to the town. The Talgar mountains are a popular tourist destination famous for their mountaineering routes, camping and recreational facilities...

and went walking with one of his NKVD escort; Maclean availed himself of peasant hospitality and commented on the general prosperity. He managed to hire a car and made it to Issyk-kul, the lake that never freezes, but had to turn back because of the season. From Alma Ata Maclean took the train for Tashkent

Tashkent

Tashkent is the capital of Uzbekistan and of the Tashkent Province. The officially registered population of the city in 2008 was about 2.2 million. Unofficial sources estimate the actual population may be as much as 4.45 million.-Early Islamic History:...

, passing through villages where "nothing seemed to have changed since the time when the country was ruled over by the Emir of Bokhara"; men still rode bulls and women still wore veils made of black horsehair. From Tashkent, which then had a reputation for wickedness, he made the final leg to the fabled city of Samarkand

Samarkand

Although a Persian-speaking region, it was not united politically with Iran most of the times between the disintegration of the Seleucid Empire and the Arab conquest . In the 6th century it was within the domain of the Turkic kingdom of the Göktürks.At the start of the 8th century Samarkand came...

. He returned to Moscow with plans for a further trip.

Maclean spent the winter working in Moscow and amusing himself at the dacha

Dacha

Dacha is a Russian word for seasonal or year-round second homes often located in the exurbs of Soviet and post-Soviet cities. Cottages or shacks serving as family's main or only home are not considered dachas, although many purpose-built dachas are recently being converted for year-round residence...

(country cottage) of American friends, including Chip Bohlen

Charles E. Bohlen

Charles Eustis “Chip” Bohlen was a United States diplomat from 1929 to 1969 and Soviet expert, serving in Moscow before and during World War II, succeeding George F. Kennan as United States Ambassador to the Soviet Union , then ambassador to the Philippines , and to France...

. In March 1938 a show trial

Show trial

The term show trial is a pejorative description of a type of highly public trial in which there is a strong connotation that the judicial authorities have already determined the guilt of the defendant. The actual trial has as its only goal to present the accusation and the verdict to the public as...

was announced, the first such public event in over a year; he attended every day of what became known as the Trial of the Twenty-One. The book goes into great detail, spending 40 pages on description and analysis of the trial, its prominent figures and its twists and turns.

To Chinese Turkestan

When the weather became more conducive to travel, Maclean began his third and longest trip, aiming for Chinese Turkestan, immediately east of the Soviet Central Asian republics he had reached in 1937. This journey, unlike the previous two, was at the request of the British government. They wished him to investigate the conditions in Urumchi (ÜrümqiÜrümqi

Ürümqi , formerly Tihwa , is the capital of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China, in the northwest of the country....

), the capital of the province of Sinkiang (Xinjiang

Xinjiang

Xinjiang is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. It is the largest Chinese administrative division and spans over 1.6 million km2...

), which had fallen under Soviet influence. He was commissioned to talk to the tupan

Tupan

Tupan can mean several things:* Another spelling of tapan, a drum used in Balkan and Turkish music. See davul.* The provincial governor in some areas of China in the first half of the 20th Century.* The thunder god of the Tupi and Guaraní people of Brazil....

(provincial governor) there about the situation of both the consul-general and the British Indian traders. The first stage was retracing his steps on a five-day train journey to Alma Ata; the train ran via Orenburg

Orenburg

Orenburg is a city on the Ural River and the administrative center of Orenburg Oblast, Russia. It lies southeast of Moscow, very close to the border with Kazakhstan. Population: 546,987 ; 549,361 ; Highest point: 154.4 m...

and the Aral Sea

Aral Sea

The Aral Sea was a lake that lay between Kazakhstan in the north and Karakalpakstan, an autonomous region of Uzbekistan, in the south...

, then parallel to the Syr Darya

Syr Darya

The Syr Darya , also transliterated Syrdarya or Sirdaryo, is a river in Central Asia, sometimes known as the Jaxartes or Yaxartes from its Ancient Greek name . The Greek name is derived from Old Persian, Yakhsha Arta , a reference to the color of the river's water...

and the mountains of Kirghizia (Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan , officially the Kyrgyz Republic is one of the world's six independent Turkic states . Located in Central Asia, landlocked and mountainous, Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the southwest and China to the east...

). From Alma Aty he travelled four hundred miles north through the Hungry Steppe to Ayaguz (Ayagoz), where "a road which had been made, and was being kept up, for a very definite purpose" lay to the frontier town of Bakhti (Bakhty or Bakhtu, about 17 km from Tacheng

Tacheng

-References:* Khālidī, Qurbanʻali, Allen J. Frank, and Mirkasym Abdulakhatovich Usmanov. An Islamic Biographical Dictionary of the Eastern Kazakh Steppe, 1770-1912. Brill's Inner Asian library, v. 12. Leiden: Brill, 2004....

, known in Maclean's time as Chuguchak). The Soviet officials were, at first, willing to assist him but the Chinese ones were not, and in the course of the negotiations that surrounded his passage, Maclean discovered that the Soviets exercised some influence over at least the consul if not the provincial government of their neighbours. He crossed the border into China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, where he was refused permission to continue; he was forced to return to Alma Aty, whence he was expelled. Soon he found himself back in Moscow.

To Bokhara and Kabul

His fourth and final Soviet trip was once more to Central Asia, spurred by the desire to reach Bokhara (BukharaBukhara

Bukhara , from the Soghdian βuxārak , is the capital of the Bukhara Province of Uzbekistan. The nation's fifth-largest city, it has a population of 263,400 . The region around Bukhara has been inhabited for at least five millennia, and the city has existed for half that time...

, Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan , officially the Republic of Uzbekistan is a doubly landlocked country in Central Asia and one of the six independent Turkic states. It shares borders with Kazakhstan to the west and to the north, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to the east, and Afghanistan and Turkmenistan to the south....

), the capital of the emirate which had been closed to Europeans until recent times. Maclean recounts how Charles Stoddart

Charles Stoddart

Colonel Charles Stoddart was a British officer and diplomat. He was a famous British agent in Central Asia during the period of the Great Game....

and Arthur Conolly

Arthur Conolly

Arthur Conolly was a British intelligence officer, explorer and writer. He was a captain of the 1st Bengal Light Cavalry in the service of the British East India Company...

were executed there in the context of The Great Game

The Great Game

The Great Game or Tournament of Shadows in Russia, were terms for the strategic rivalry and conflict between the British Empire and the Russian Empire for supremacy in Central Asia. The classic Great Game period is generally regarded as running approximately from the Russo-Persian Treaty of 1813...

, and how Joseph Wolff

Joseph Wolff

Joseph Wolff , Jewish Christian missionary, was born at Weilersbach, near Bamberg, Germany. He travelled widely, and was known as the Eccentric Missionary, according to Fitzroy Maclean's Eastern Approaches...

, known as the Eccentric Missionary, barely escaped their fate when he came looking for them in 1845. In early October 1938 Maclean set out again, first for Ashkhabad (Ashgabat, capital of the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic), then through the Kara Kum (Black Desert), not breaking his journey at either Tashkent or Samarkand, but pushing on to Kagan

Kagan, Uzbekistan

Kagan, Uzbekistan is a town and seat of Kagan District in Bukhara Province in Uzbekistan....

, the nearest point on the railway to Bokhara. After trying to smuggle himself aboard a lorry transporting cotton, he ended up walking to the city, and spent several days sight-seeing "in the steps of the Eccentric Missionary" and sleeping in parks, much to the frustration of the NKVD spies who were shadowing him. He judged it an "enchanted city", with buildings that rivalled "the finest architecture of the Italian Renaissance

Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance began the opening phase of the Renaissance, a period of great cultural change and achievement in Europe that spanned the period from the end of the 13th century to about 1600, marking the transition between Medieval and Early Modern Europe...

". Aware of his limited time, he cut short his wanderings and took the train towards Stalinabad (Dushanbe

Dushanbe

-Economy:Coal, lead, and arsenic are mined nearby in the cities of Nurek and Kulob allowing for the industrialization of Dushanbe. The Nurek Dam, the world's highest as of 2008, generates 95% of Tajikistan's electricity, and another dam, the Roghun Dam, is planned on the Vakhsh River...

, the capital of Tajikistan

Tajikistan

Tajikistan , officially the Republic of Tajikistan , is a mountainous landlocked country in Central Asia. Afghanistan borders it to the south, Uzbekistan to the west, Kyrgyzstan to the north, and China to the east....

), disembarking at Termez

Termez

Termez is a city in southern Uzbekistan near the border with Afghanistan.Some link the name of the city to thermos, "hot" in Greek, tracing its name back to Alexander the Great. Others suggest that it came from Sanskrit taramato, meaning "on the river bank". It is the hottest point of Uzbekistan...

. This town sits on the Amu Darya

Amu Darya

The Amu Darya , also called Oxus and Amu River, is a major river in Central Asia. It is formed by the junction of the Vakhsh and Panj rivers...

(the Oxus), and the other side of the river lies in Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Afghanistan , officially the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located in the centre of Asia, forming South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East. With a population of about 29 million, it has an area of , making it the 42nd most populous and 41st largest nation in the world...

. Maclean claimed that "very few Europeans except Soviet frontier guards have ever seen it at this or any other point of its course". After more negotiations, he managed to cross the river and thus leave the USSR, and from that point his only guide seems to have been the narrative of "the Russian Burnaby

Frederick Gustavus Burnaby

Colonel Frederick Gustavus Burnaby was an English traveller and soldier.-Life:He was born in Bedford, the son of the Rev. Gustavus Andrew Burnaby of Somersby Hall, Leicestershire, and canon of Middleham in Yorkshire , by Harriet, sister of Mr. Henry Villebois of Marham House, Norfolk...

", a colonel Nikolai Ivanovich Grodekov, who rode from Samarkand to Mazar-i-Sharif and Herat

Herat

Herāt is the capital of Herat province in Afghanistan. It is the third largest city of Afghanistan, with a population of about 397,456 as of 2006. It is situated in the valley of the Hari River, which flows from the mountains of central Afghanistan to the Karakum Desert in Turkmenistan...

in 1878. The following day he and a guide set out on horseback, riding through jungle and desert, and detained on the way by dubious characters who may or may not have been brigands. (Maclean, a proficient linguist, was hamstrung on entering Afghanistan by the lack of any lingua franca

Lingua franca

A lingua franca is a language systematically used to make communication possible between people not sharing a mother tongue, in particular when it is a third language, distinct from both mother tongues.-Characteristics:"Lingua franca" is a functionally defined term, independent of the linguistic...

.) They rode past the ruins of Balkh

Balkh

Balkh , was an ancient city and centre of Zoroastrianism in what is now northern Afghanistan. Today it is a small town in the province of Balkh, about 20 kilometers northwest of the provincial capital, Mazar-e Sharif, and some south of the Amu Darya. It was one of the major cities of Khorasan...

, a civilization founded by Alexander the Great and destroyed by Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan , born Temujin and occasionally known by his temple name Taizu , was the founder and Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, which became the largest contiguous empire in history after his death....

. After a night in Mazar, Maclean managed to get a car and driver, and progressed as rapidly as he could to Doaba, a village half-way to Kabul

Kabul

Kabul , spelt Caubul in some classic literatures, is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. It is also the capital of the Kabul Province, located in the eastern section of Afghanistan...

, where he had arranged to meet the British minister

Diplomatic rank

Diplomatic rank is the system of professional and social rank used in the world of diplomacy and international relations. Over time it has been formalized on an international basis.-Ranks:...

(i.e., ambassador), Colonel Frazer-Tytler. Together, they returned to the capital via Bamyan and its famous statues

Buddhas of Bamyan

The Buddhas of Bamiyan were two 6th century monumental statues of standing buddhas carved into the side of a cliff in the Bamyan valley in the Hazarajat region of central Afghanistan, situated northwest of Kabul at an altitude of 2,500 meters...

. Maclean circled back to Moscow via Peshawar

Peshawar

Peshawar is the capital of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and the administrative center and central economic hub for the Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan....

, Delhi

Delhi

Delhi , officially National Capital Territory of Delhi , is the largest metropolis by area and the second-largest by population in India, next to Mumbai. It is the eighth largest metropolis in the world by population with 16,753,265 inhabitants in the Territory at the 2011 Census...

, Baghdad

Baghdad

Baghdad is the capital of Iraq, as well as the coterminous Baghdad Governorate. The population of Baghdad in 2011 is approximately 7,216,040...

, Persia, and Armenia

Armenia

Armenia , officially the Republic of Armenia , is a landlocked mountainous country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia...

.

Orient Sand: the Western Desert Campaign

The middle section of the book details Maclean's first set of experiences in World War IIWorld War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. He was invited to join the newly formed Special Air Service

Special Air Service

Special Air Service or SAS is a corps of the British Army constituted on 31 May 1950. They are part of the United Kingdom Special Forces and have served as a model for the special forces of many other countries all over the world...

(SAS), where, as part of the Western Desert Campaign

Western Desert Campaign

The Western Desert Campaign, also known as the Desert War, was the initial stage of the North African Campaign during the Second World War. The campaign was heavily influenced by the availability of supplies and transport. The ability of the Allied forces, operating from besieged Malta, to...

, he planned and executed raids on Axis-held Benghazi

Benghazi

Benghazi is the second largest city in Libya, the main city of the Cyrenaica region , and the former provisional capital of the National Transitional Council. The wider metropolitan area is also a district of Libya...

, on the coast of Libya

Libya

Libya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

. When it became clear that the North African Campaign

North African campaign

During the Second World War, the North African Campaign took place in North Africa from 10 June 1940 to 13 May 1943. It included campaigns fought in the Libyan and Egyptian deserts and in Morocco and Algeria and Tunisia .The campaign was fought between the Allies and Axis powers, many of whom had...

was drawing to a close towards the end of 1942 and it became too quiet for his taste, he travelled east to arrest General Fazlollah Zahedi

Fazlollah Zahedi

Mohammad Fazlollah Zahedi was an Iranian general and statesman who replaced democratically elected Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadeq through a western-backed coup d'état, in which he played a major role.-Early years:Born in Hamedan in 1897, Fazlollah Zahedi was the son of Abol Hassan...

, at the time the head of the Persian armed forces

Military of Iran

The Armed Forces of the Islamic Republic of Iran include the IRIA and the IRGC and the Police Force .These forces total about 545,000 active personnel . All branches of armed forces fall under the command of General Headquarters of Armed Forces...

in the south.

Joining up

The first challenge Maclean faced was getting into military service at all. His Foreign Office job was a reserved occupationReserved occupation

A reserved occupation is an occupation considered important enough to a country that those serving in such occupations are exempt - in fact forbidden - from military service....

, so he was not allowed to enlist. The only way around this was to go into politics, and on this stated ground Maclean tendered his resignation in 1941 to Alexander Cadogan, an FO mandarin

Mandarin (bureaucrat)

A mandarin was a bureaucrat in imperial China, and also in the monarchist days of Vietnam where the system of Imperial examinations and scholar-bureaucrats was adopted under Chinese influence.-History and use of the term:...

. When his erstwhile employers discovered this to be merely a ruse or legal fiction

Legal fiction

A legal fiction is a fact assumed or created by courts which is then used in order to apply a legal rule which was not necessarily designed to be used in that way...

along the lines of taking the Chiltern Hundreds

Chiltern Hundreds

Appointment to the office of Crown Steward and Bailiff of the three Chiltern Hundreds of Stoke, Desborough and Burnham is a sinecure appointment which is used as a device allowing a Member of the United Kingdom Parliament to resign his or her seat...

, he was forced to run for office and, despite his self-confessed inexperience, was chosen as a Conservative candidate, and eventually elected MP. Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

jocularly accused him of using "the Mother of Parliaments as a public convenience". In the meantime, Maclean had immediately enlisted, taking a taxi from Sir Alexander's office to a nearby recruiting station, where he joined the Cameron Highlanders

Cameron Highlanders

Cameron Highlanders may mean:* The Highlanders , infantry regiment in the Scottish Division of the British Army* The Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa, Primary Reserve infantry regiment of the Canadian Forces...

, his father's regiment, as a private

Private (rank)

A Private is a soldier of the lowest military rank .In modern military parlance, 'Private' is shortened to 'Pte' in the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries and to 'Pvt.' in the United States.Notably both Sir Fitzroy MacLean and Enoch Powell are examples of, rare, rapid career...

.

Benghazi and the desert retreat

After basic training, Maclean was sent to CairoCairo

Cairo , is the capital of Egypt and the largest city in the Arab world and Africa, and the 16th largest metropolitan area in the world. Nicknamed "The City of a Thousand Minarets" for its preponderance of Islamic architecture, Cairo has long been a centre of the region's political and cultural life...

, where David Stirling

David Stirling

Colonel Sir Archibald David Stirling, DSO, DFC, OBE was a Scottish laird, mountaineer, World War II British Army officer, and the founder of the Special Air Service.-Life before the war:...

invited him to join the newly formed Special Air Service

Special Air Service

Special Air Service or SAS is a corps of the British Army constituted on 31 May 1950. They are part of the United Kingdom Special Forces and have served as a model for the special forces of many other countries all over the world...

(SAS), which he did. They worked closely with the Long Range Desert Group

Long Range Desert Group

The Long Range Desert Group was a reconnaissance and raiding unit of the British Army during the Second World War. The commander of the German Afrika Corps, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, admitted that the LRDG "caused us more damage than any other British unit of equal strength".Originally called...

(LRDG), a mechanised reconnaissance unit, to travel far behind enemy lines and attack targets such as aerodromes. Maclean's first operation with the SAS, once his training was completed, was to Benghazi

Benghazi

Benghazi is the second largest city in Libya, the main city of the Cyrenaica region , and the former provisional capital of the National Transitional Council. The wider metropolitan area is also a district of Libya...

, Libya

Libya

Libya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

's second largest city, in late May 1942. He was joined on this operation by Randolph Churchill

Randolph Churchill

Major Randolph Frederick Edward Spencer-Churchill, MBE was the son of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his wife Clementine. He was a Conservative Member of Parliament for Preston from 1940 to 1945....

, son of the prime minister. They drove from Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

via the seaport of Mersa Matruh and the inland Siwa Oasis

Siwa Oasis

The Siwa Oasis is an oasis in Egypt, located between the Qattara Depression and the Egyptian Sand Sea in the Libyan Desert, nearly 50 km east of the Libyan border, and 560 km from Cairo....

. They crossed the ancient caravan route known as the Trigh-el-Abd, which the enemy had laced with little bombs, and camped in the Gebel Akhdar, the Green Mountain just inland from the coastal plain. Once inside the occupied city, their patrol came face to face with Italian soldiers several times; Maclean, with his excellent Italian, managed to bluff his way out of all of these encounters by pretending to be a staff officer. They spent two nights and a day in the city. They had hoped to sabotage ships, but both the rubber boats

Inflatable boat

An inflatable boat is a lightweight boat constructed with its sides and bow made of flexible tubes containing pressurised gas. For smaller boats, the floor and hull beneath it is often flexible. On boats longer than , the floor often consists of three to five rigid plywood or aluminium sheets fixed...

they had brought with them failed to inflate, so they treated the visit as a reconnaissance

Reconnaissance

Reconnaissance is the military term for exploring beyond the area occupied by friendly forces to gain information about enemy forces or features of the environment....

mission. The drive back was uneventful, but nearing Cairo, Maclean, along with most of his party, was seriously injured in a crash and spent months out of action.

Once he had recovered, Stirling involved him in preparations for a larger SAS attack on Benghazi. They attended a dinner with Churchill, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff General Alan Brooke

Alan Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke

Field Marshal The Rt. Hon. Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke, KG, GCB, OM, GCVO, DSO & Bar , was a senior commander in the British Army. He was the Chief of the Imperial General Staff during the Second World War, and was promoted to Field Marshal in 1944...

, and General Harold Alexander

Harold Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Tunis

Field Marshal Harold Rupert Leofric George Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Tunis was a British military commander and field marshal of Anglo-Irish descent who served with distinction in both world wars and, afterwards, as Governor General of Canada, the 17th since Canadian...

, who was about to assume control of Middle East Command

Middle East Command

The Middle East Command was a British Army Command established prior to the Second World War in Egypt. Its primary role was to command British land forces and co-ordinate with the relevant naval and air commands to defend British interests in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean region.The...

, the post responsible for the overall conduct of the campaign in the North African desert

Western Desert Campaign

The Western Desert Campaign, also known as the Desert War, was the initial stage of the North African Campaign during the Second World War. The campaign was heavily influenced by the availability of supplies and transport. The ability of the Allied forces, operating from besieged Malta, to...

. Four operations were designed to create a diversion from Rommel

Rommel

Erwin Rommel was a German World War II field marshal.Rommel may also refer to:*Rommel *Rommel Adducul , Filipino basketball player*Rommel Fernández , first Panamanian footballer to play in Europe...

's attempt on El Alamein

El Alamein

El Alamein is a town in the northern Matrouh Governorate of Egypt. Located on the Mediterranean Sea, it lies west of Alexandria and northwest of Cairo. As of 2007, it has a local population of 7,397 inhabitants.- Climate :...

: attacks on Benghazi, Tobruk

Tobruk

Tobruk or Tubruq is a city, seaport, and peninsula on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near the border with Egypt. It is the capital of the Butnan District and has a population of 120,000 ....

, Barce, and the Jalo oasis

Jalo oasis

Jalo Oasis is an oasis in Cyrenaica, Libya, located west of the Great Sand Sea and about 250 km south-east of the Gulf of Sirte. Quite large, long and up to wide, it supports a number of settlements, the largest of which is the town of Jalu...

. These all started out from Kufra

Kufra

Kufra is a basin and oasis group in Al Kufrah District, southeastern Cyrenaica in Libya. Kufra is historically important above all because at the end of nineteenth century it became the center and holy place of the Senussi order...

, an oasis 800 miles inland. Maclean's convoy drove to the Gebel across the Sand Sea

Kalansho Sand Sea

The Calanshio Sand Sea is located in the Saharan Libyan Desert, of the Kufra District in Cyrenaica, eastern Libya. This and the Egyptian and Ribiana Sand Seas contains dunes up to 110m in height and cover ~25% of the Libyan Desert. The dunes were created by the wind.The Calanshio Sand Sea is the...