Gaelic Ireland

Encyclopedia

Gaelic Ireland is the name given to the period when a Gaelic

political order existed in Ireland

. The order continued to exist after the arrival of the Anglo-Normans

(1169 AD) until about 1607 AD. For much of this period, the island was a patchwork of kingdoms of various size and other semi-sovereign territories known as túath

a, much like the situation in Medieval Germany

but in most periods without any effective national overlordship. These kingdoms and túatha very frequently competed for control of resources and thus continually grew and receded with the fortunes of time. Thousands of battles and predatory excursions involving their leaders are recorded in the Irish annals

and other sources.

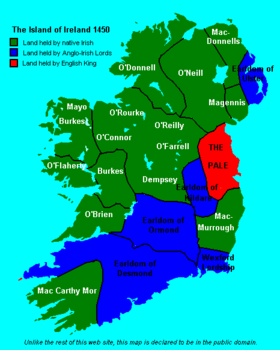

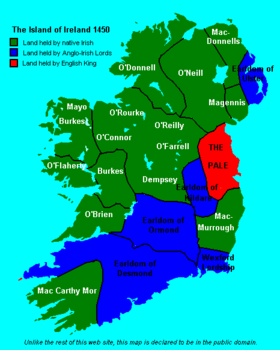

After the Norman invasion

of 1169–71, large portions of Ireland came under the control of Norman lords – this territory was known as the Lordship of Ireland

. However, the Gaelic system continued to exist in areas outside Norman control, and the government

's power gradually shrank to an area known as The Pale

. In 1541 the Kingdom of Ireland

was established and the English monarchy began to conquer the island. This resulted in the Flight of the Earls

in 1607, which marked the end of the Gaelic order.

n) and, as such, the landscape and history of Ireland was wrought with inter-fine relationships, marriages, friendships, wars, vendettas, trading, and so on. Despite this, Gaelic Ireland possessed a rich oral culture and appreciation of deeper and intellectual pursuits. Filidh and druids were held in high regard during pagan

times and carried the oral history and traditions of their people throughout generations. Later, many of the spiritual and intellectual tasks they carried out were passed down to Christian monks, after said religion prevailed from the 5th century onwards. However, the filidh continued to hold a high position in their clanns and territories. Poetry, music, storytelling, literature and various forms of arts were highly prized and cultivated in both pagan and Christian Gaelic Ireland. Hospitality, bonds of kinship and the fulfilment of social and ritual responsibilities were held sacred.

The Gaelic order in Ireland, rather than a single unified kingdom in the feudal sense, was a patchwork of túath

a (singular: túath). These túatha often competed for control of resources and thus continually grew and shrank. Law tracts from the beginning of the eight century describe a hierarchy of kings: kings of túath subject to kings of several túatha who again were subject to provincial over kings. Already before the 8th century these over-kingships had begun to dissolve the túatha as the basic sociopolitic unit.

. They worshipped a variety of gods and goddesses, which generally have parallels in the pantheons of other Celts. They were also animists

, believing that all aspects of the natural world contained spirits, and that these spirits could be communicated with. Burial practices –which included burying food, weapons, and ornaments with the dead– suggest a belief in life after death

. Some have equated this afterlife with the realms known as Mag Mell

and Tír na nÓg

in Irish mythology. There were four major religious festivals each year, marking the traditional four divisions of the year – Imbolc

, Beltaine, Lughnasadh

and Samhain

.

The mythology of Ireland did not entirely survive the conversion to Christianity

, but much of it was preserved, shorn of its religious meanings, in medieval Irish literature. This large body of work is typically divided into three overlapping cycles: the Mythological Cycle

, the Ulster Cycle

, and the Fenian Cycle

. The first cycle is a pseudo-history of Ireland that describes four invasions (or migrations) by semi-divine peoples. Two of these groups, the Fomorians

and Tuatha Dé Danann

, are believed to represent the pre-Gaelic and Gaelic pantheons

. The second cycle recounts the lives and deaths of Ulaid

heroes such as Cúchulainn

. The third cycle recounts the exploits of Fionn mac Cumhaill

and the Fianna

. There are also a number of stories that do not fit into these cycles – this includes the immrama and echtrai, which are tales of the 'otherworld

' and the voyages to get there.

. The brithem were the judiciary

in Gaelic society and were expected to interpret the written laws and give advice or pass judgement accordingly. Kings would have been able to pass judgement also, but it is unclear how much they would have been able to make their own judgments, and how much they would have had to rely on professionals. However, unlike other kingdoms in Europe, Gaelic kings—by their own authority—could not enact new laws as they wished and could not be "above the law".

Gaelic law was a civil

Gaelic law was a civil

rather than a criminal

code, concerned with the payment of fines (dire) for harm done. Although Gaelic law recognized a distinction between intentional and unintentional injury, any type of injury required compensation. The legal text Bretha Déin Chécht goes into great detail in describing compensation based on the location, severity, and type of wound. Types of fines included coirpdire (body-fine), einachlan (honour-price) and éraic (reparation). The éraic was the fine for murder

or manslaughter

; the fine for murder being twice that for manslaughter. State-administered punishment for crime was a foreign concept. Criminals were summoned to appear before a brithem, who heard the case and assessed the amount of fine that should be paid. If the defendant did not pay outright, his property was seized

until he did so. Should the offender be unable to pay, his family would be responsible for doing so. Should the family be unable or unwilling to pay, responsibility would extend to the wider fine. If the criminal died, and his crime was purely personal, the fine would be freed of liability. However, if the criminal died and his crime had caused damage/loss of property, the fine was still liable for this loss. Hence, it has been argued that "the people were their own police".

Punishment was adjusted to match one's rank or profession. In certain cases, those of higher rank could receive a higher amount of compensation. However, an offence against the property of a poor man (who could ill afford it), was punished more harshly than a similar offence upon a wealthy man. The clergy

were more harshly punished than the laity

. When a layman had paid his fine he would go through a probationary period and then regain his status, but a convicted clergyman could never regain his status.

It is generally believed that execution

of criminals was rare. If a murderer was unable/unwilling to pay éraic and was surrendered to his victim's family, they might kill him if they pleased should nobody intervene by paying the éraic. Certain criminals might be expelled from the fine and its territory, even though the fine had been paid. Such people became outlaws (with no protection from the law) and anyone who sheltered him became liable for his crimes. If he still haunted the fine territory and continued his crimes there, he was proclaimed in the fines public assembly and after this anyone might lawfully kill him.

The law texts take great care to define social status, the rights and duties that went with that status, and the relationships between people. For example, chieftains had to take responsibility for members of their fine, acting as a surety

for some of the actions of members and making sure debts were paid. He would also be responsible for unmarried women after the death of their fathers.

In Gaelic Ireland each person belonged to a kin-group known as a clan

In Gaelic Ireland each person belonged to a kin-group known as a clan

n (plural: clanna) or fine (plural: finte). Each clann was a large group of related people—theoretically an extended family—supposedly descended from one progenitor and all owing allegiance to its chieftain, known as a cennfine or toísech

(plural: toísigh). Often, clanna are thought of as based on blood kinship alone; however, clanna also included those who were adopted or fostered into the clann, and those who joined the clann for strategic reasons (such as safety or combining of resources). As Nicholls describes, they would be better thought of as akin to the modern-day corporation

. The power of clanna fluctuated, and endemic warfare

between clanna was a constant affair. Once-powerful clanna could in time decline in stature and be amalgamated into once-smaller ones. How this "merger" would be dealt with would be a matter of negotiation. Many clanna were also divided into a number of sub-groups known as septs

, often when that group took up residence outside the original clann territory.

Lineage was based on the practice of tanistry

(rather than primogeniture

). At an assembly called a tocomra a relative was elected—prior to the death of a leader—to act as his deputy and then his successor. To be eligible for election, one had to share the same great-grandfather as the toísech. This group of electable cousins was called the derbfine

, and the elected person was called a tanaiste

(plural: tanaistí). The clann system formed the basis of society.

Gaelic society was structured hierarchically

.

Although quite distinct, these ranks were not utterly exclusive caste

s like those of India. It was possible for persons to rise or sink from one rank to another. Progressing upward could be achieved a number of ways, such as by gaining wealth, by gaining skill in some department, by qualifying for a learned profession, by displaying conspicuous valour, or by performing some signal service to the community. An example is a person choosing to become a briugu (hospitaller). A briugu had to have his house open to any guests, which included feeding no matter how large the group. To enable the briugu to fulfill these duties, he was allowed more land and privileges, but if he ever refused guests he could lose this status.

Apparently the laws on marriage and divorce were wholly pagan, and never underwent any change in Christian times. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Gaelic Irish kept many of their marriage laws and traditions separate from those of the Church.

Under Gaelic law, married women could hold property independent of their husbands, the tie between married women and their own families was kept intact, couples could easily divorce/separate, and men could have concubines

(which could be lawfully bought). These laws differed from most of contemporary Europe and from Church law.

The lawful age of marriage was fifteen for girls and eighteen for boys. Upon marriage, the families of the bride and bridegroom were expected to contribute to the match. It was the custom for the bridegroom and his family to pay a coibche and the bride was allowed a portion of it. If the marriage ended due to a fault of the husband then the coibche was kept by the wife and her family, but if the fault lay with the wife then the coibche was to be returned. It was customary for the bride to receive a spréidh from her family (or foster family) upon marriage. This was to be returned if the marriage ended through divorce or the death of the husband. Later, the spréidh seems to have been converted into a dowry

. Women could seek divorce/separation as easily as men could and, when obtained on her petition, she kept all the property she had brought her husband during their marriage.

Trial marriages seem to have been popular among the rich and powerful, and thus it has been argued that cohabitation

before marriage must have been acceptable. It also seems that the wife of a chieftain was entitled to some share of the chief's authority over his territory. This led to some Gaelic Irish wives wielding a great deal of political power.

In Gaelic Ireland a type of fosterage

was commonplace, whereby (for certain periods of time) children would be placed in the care of other fine members, namely their mother's family, preferably her brother. This may have been used to strengthen family ties or political bonds. Foster parents were required to teach their foster children or to have them taught. Foster parents who had properly done their duties were entitled to be supported by their foster children in old age (if they were in need and had no children of their own). As with divorce, Gaelic law again differed from most of Europe and from Church law in giving legal status to both "legitimate" and "illegitimate"

children.

The Gaelic Irish typically lived in circular houses with conical roofs. In some areas, walls were built mostly of stone. In others, walls were built with wattle and daub

The Gaelic Irish typically lived in circular houses with conical roofs. In some areas, walls were built mostly of stone. In others, walls were built with wattle and daub

, timber, sods, clay, or a mix of materials. Roofs were made of thatch or sods. These houses (along with livestock) were often surrounded by a circular rampart

called a "ringfort

". There are two main types of ringfort. The ráth is an earthen ringfort, averaging 30m diameter, with a dry outside ditch. The cathair or caiseal is a stone ringfort. Sometimes there were several buildings inside. Most date to the period 500–1000 CE and there is evidence of large-scale ringfort desertion at the end of the first millennium. Between 30,000 and 40,000 survived into the 19th century to be mapped by Ordnance Survey Ireland

. Another type of native dwelling was the crannóg

, which were fortified roundhouses built on wooden platforms in lakes.

Monastic settlements emerged in the 5th century. Although there were no town

s or village

s, the monasteries sometimes became the centre of a small settlement cluster or "monastic town". By the 10th century, there were few nucleated settlements other than these monastic towns and the Norse-Gaelic

ports. It was at this time, perhaps as a response to Viking raids, that many of the Irish round tower

s were built.

In the fifty years before the Norman invasion (1169), the term "castle" appears in Gaelic writings, although all the recorded examples of pre-Norman castles have been destroyed. After the invasion, the Normans converted some ringforts into motte-and-bailey

s. From the mid 14th century onward, the Normans began to build tower house

s in large numbers. These are free-standing multi-storey stone towers usually surrounded by a wall (see bawn

) and ancillary buildings. Gaelic families had begun to build their own tower houses by the 15th century. As many as 7000 may have been built, but they were rare in areas with little Norman settlement or contact. They are concentrated in counties Limerick and Clare but are lacking in Ulster, except the area around Strangford Lough

.

In Gaelic law, a 'sanctuary' called a maighin digona surrounded each person's dwelling. Within this the owner and his family and property were protected by law. The maighin digona's size varied according to the owner's rank. In the case of a bóaire

it extended as far as he, while sitting at his house, could cast a cnairsech (variously described as a spear or sledgehammer). The owner of a maighin digona could extend its protection to someone fleeing from pursuers, who would then have to resort to legal methods of bringing that person to justice.

(cows, sheep, pigs and horses) and fishing

was the main currency and the main source of sustenance. Horticulture

was practiced; the main crops being oats, wheat and barley, although flax was also grown for making linen. The main exports were fish, hides, wool and linen cloth. The main imports were goods that could not be found in Ireland, such as salt and wine.

Transhumance

was practised, whereby the people moved with their livestock (over short distances) to higher pasture

s in summer and back to lower pastures in the cooler months. The summer pasture was called the buaile (anglicised as booley) and it is significant that the Irish word for boy (buachaill) originally meant a herdsman. Many moorland

areas were "shared as a common summer pasturage

by the people of a whole parish or barony".

Throughout the Middle Ages

Throughout the Middle Ages

, the common clothing amongst the Gaelic Irish consisted of a brat (a woollen cloak or mantle) worn over a léine (a loose-fitting, long-sleeved tunic made of wool or linen). For men these were either thigh-length or knee-length and for women they were longer. Men sometimes wore tight-fitting truis

on the legs, but otherwise went bare-legged. The brat was usually fastened with a crios (belt

) and dealg (brooch

), with men usually wearing the dealg at their shoulders and women at their chests. The ionar (a short, tight-fitting jacket) became popular later on. In Topographia Hibernica

, written during the 1180s, Gerald de Barri wrote that the Irish also wore hoods at that time (perhaps forming part of the brat), while Edmund Spenser

wrote in the 1580s that the brat was (in general) their sole garment.

According to Gerald de Barri, most of the Irish wore clothes made of black wool, because most of the sheep in Ireland were black in his time. The number of colours worn came to indicate the rank or wealth of the wearer; the wealthy often wore cloth of many colours while the poor only wore cloth of one colour.

Both men and women grew their hair long and often braid

ed it. It is claimed that the Gaelic Irish took great pride in their long hair—for example, a person could be forced to pay the heavy fine of two cows for shaving a man's head against his will. The glib (short all over except for a thick lock of hair towards the front of the head) was also popular among some medieval Gaels, and the mohawk

may have been popular in pre-Christian times (as worn by the Irish bog body

known as Clonycavan man

). Gaelic men typically let their facial hair grow into a beard

, and it was often seen as dishonourable for a Gaelic man to have no facial hair.

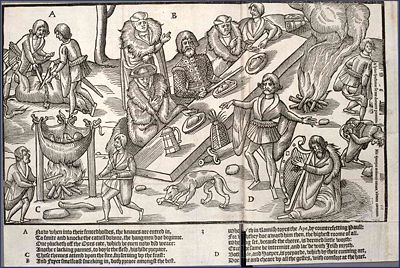

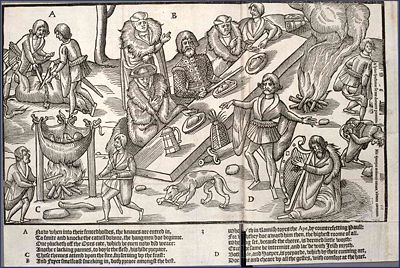

Gaelic Ireland was a land of continuous warfare, as túatha fought for supremacy against each other and (later) against the Anglo-Normans.

Gaelic Ireland was a land of continuous warfare, as túatha fought for supremacy against each other and (later) against the Anglo-Normans.

Throughout the Middle Ages and for some time after, outsiders often wrote that the style of Irish warfare differed greatly from what they deemed to be the norm. The Gaelic Irish preferred hit-and-run

raids

(the creach), which involved catching the enemy unaware and storming their strongholds. If this worked they would then seize any valuables (mainly livestock) and potentially valuable hostages, burn the crops, and escape. The cattle raid was often referred to as a táin bó

in Gaelic literature. Although hit-and-run raiding was the preferred tactic in medieval times, the Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib recounts lengthy pitched battle

s and the use of boats in tandem with land forces. It was not unusual for armies to launch long-range attacks, setting up camps along the way.

A typical medieval Irish army included light infantry

, heavy infantry

and cavalry

. The bulk of the army was made-up of light infantry called ceithern

(anglicised kern). The ceithern wandered Ireland offering their services for hire, usually carrying swords, knives, short spears, bows and shields. The cavalry was usually made-up of a chieftain and his close relatives. They usually rode without saddles but wore armour and helmets and wielded swords, knives and long spears. One type of Irish cavalry was the hobelar

. The heavy infantry were the gallóglaigh

(anglicised gallowglass). They were originally Scottish mercenaries who appeared in the 13th century, but by the 15th century most large túatha had their own hereditary force of gallóglaigh. They usually wore chainmail

and helmets and wielded claymore

s and axes. The gallóglaigh provided the retreating plunderers with a "moving line of defence from which the horsemen could make short, sharp charges, and behind which they could retreat when pursued". As their armour made them less mobile, they were sometimes planted at strategic spots along the line of retreat. Both the horsemen and gallóglaigh had servants to carry their weapons into battle.

Warriors were sometimes rallied into battle accompanied by blowing horn

s and warpipes

. Gaius Julius Solinus

wrote (in the 2nd century) that the pagan Irish besmeared their faces with the blood of the slain to frighten their enemies. According to Gerald de Barri (in the 12th century), they did not wear armour, as they deemed it cumbersome to wear and "brave and honourable" to fight without it. Instead, most ordinary soldiers fought semi-naked and carried only their weapons and a small round shield—Spenser wrote that these shields were covered with leather and painted in bright colours. Chieftains sometimes went into battle wearing helmets or headpieces adorned with eagle feathers. For ordinary soldiers, their thick hair often served as a helmet, but they sometimes wore simple helmets made from animal hides.

Gaelic warriors (and Celtic warriors in general) had a reputation as head hunters

. Ancient Romans

and Greeks

recorded the Celtic custom of beheading their enemies and publicly displaying the severed heads (for example by hanging them from the necks of horses). According to Paul Jacobsthal

, "Amongst the Celts the human head was venerated above all else, since the head was to the Celt the soul, centre of the emotions, as well as of life itself".

, jewelry

, weapon

s, drinkware, tableware

, stone carving

s and illuminated manuscript

s. Like other types of Celtic art

, Irish art from about 300 BC forms part of the wider La Tène art

style, which developed in west central Europe. By around 600 AD, after the Christianization of Ireland had begun, a style combining Celtic, Mediterranean and Germanic Anglo-Saxon

elements emerged, and was spread widely to Britain and the Continent by the Hiberno-Scottish mission

. This is known as Insular art

or Hiberno-Saxon art, which continued in some form in Ireland until the 12th century, although the Viking invasions ended its "Golden Age". Most surviving works of Insular art were either created by monks or created for use by the monasteries, with the exception of Celtic brooch

es, which were probably made and used by both clergy and laity. Examples of Insular art from Ireland include the Book of Kells

, Muiredach's High Cross

, the Tara Brooch

, the Ardagh Hoard the Derrynaflan Chalice

, and the late Cross of Cong

, which also uses Viking styles.

" and "tabor

" (see bodhrán

), that their music was fast and lively, and that their songs always began and ended with B-flat. In A History of Irish Music (1905), W. H. Grattan Flood

wrote that there were at least ten instruments in general use by the Gaelic Irish. These were the cruit (a small harp) and clairseach

(a bigger harp with typically 30 strings), the timpan (a small string instrument

played with a bow

or plectrum

), the feadan (a fife

), the buinne (an oboe

or flute

), the guthbuinne (a bassoon

-type horn

), the bennbuabhal and corn (hornpipes

), the cuislenna (bagpipes

- see Great Irish Warpipes

), the stoc and sturgan (clarion

s or trumpet

s), and the cnamha (castanets). There is also evidence of the fiddle

being used in the 8th century.

As mentioned previously, Gaelic Ireland was divided into a large number of clann territories and kingdoms which were called túath (plural: túatha). Although there was no central 'government' or 'parliament', a number of local, regional and national assemblies were held. These combined features of assemblies

As mentioned previously, Gaelic Ireland was divided into a large number of clann territories and kingdoms which were called túath (plural: túatha). Although there was no central 'government' or 'parliament', a number of local, regional and national assemblies were held. These combined features of assemblies

and fair

s.

In Ireland the highest of these was the feis

at Tara

, which occurred every third Samhain

. This was an assembly of the leading men of the whole island — kings, lords, chieftains, druids, judges etc. Below this was the óenach

or aenach. These were regional or provincial assemblies open to everyone. Examples include that held at Taillten

each Lughnasadh

, and that held at Uisnech

each Beltaine. The main purpose of these assemblies was to promulgate and reaffirm the laws — they were read aloud in public that they might not be forgotten, and any changes in them carefully explained to those present.

Each túath or clann had two assemblies of its own. These were the cuirmtig, which was open to all clann members, and the dal (a term later adopted for the Irish parliament - see Dáil Éireann

), which was open only to clann chiefs. Each clann had an additional assembly called a tocomra, in which the clann chief (toísech) and his deputy/successor (tanaiste) were elected.

Ireland became Christianized

between the 5th and 7th centuries. Pope Adrian IV, the only English pope

, had already issued a Papal Bull

in 1155 giving Henry II of England

authority to invade Ireland as a means of curbing Irish refusal to recognize Roman law. Importantly, for later English monarchs, the Bull, Laudabiliter

, maintained papal suzerainty

over the island:

In 1166, after losing the protection of High King Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, the King of Leinster

, Diarmait Mac Murchada, was forcibly exiled by a confederation of Irish forces under the new High King, Ruaidri mac Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair. Fleeing first to Bristol

and then to Normandy

, Diarmait obtained permission from Henry II of England

to use his subjects to regain his kingdom. By the following year, he had obtained these services and in 1169 the main body of Norman, Welsh

and Flemish

forces landed in Ireland and quickly retook Leinster and the cities of Waterford

and Dublin on behalf of Diarmait. The leader of the Norman force, Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke

, more commonly known as Strongbow, married Diarmait's daughter, Aoife

, and was named tánaiste

to the Kingdom of Leinster. This caused consternation to Henry II, who feared the establishment of a rival Norman state in Ireland. Accordingly, he resolved to visit Leinster to establish his authority.

Henry landed with in 1171, proclaiming Waterford

and Dublin as Royal Cities

. Adrian's successor, Pope Alexander III

, ratified the grant of Ireland to Henry in 1172. The 1175 Treaty of Windsor

between Henry and Ruaidhrí maintained Ruaidhrí as High King of Ireland but codified Henry's control of Leinster, Meath and Waterford. However, with Diarmuid and Strongbow dead, Henry back in England, and Ruaidhrí unable to curb his vassals, the high kingship rapidly lost control of the country. Henry, in 1185, awarded his Ireland to his younger son, John, with the title Dominus Hiberniae, "Lord of Ireland"

. This kept the newly created title and the Kingdom of England personally and legally separate. However, when John unexpectedly succeeded his brother as King of England in 1199, the Lordship of Ireland fell back into personal union with the Kingdom of England.

By 1261, the weakening of the Anglo-Norman Lordship had become manifest following a string of military defeats. In the chaotic situation, local Irish lords won back large amounts of land. The invasion by Edward Bruce

By 1261, the weakening of the Anglo-Norman Lordship had become manifest following a string of military defeats. In the chaotic situation, local Irish lords won back large amounts of land. The invasion by Edward Bruce

in 1315-18 at a time of famine weakened the Norman economy. The Black Death

arrived in Ireland in 1348. Because most of the English and Norman inhabitants of Ireland lived in towns and villages, the plague hit them far harder than it did the native Irish, who lived in more dispersed rural settlements. After it had passed, Gaelic Irish language and customs came to dominate the country again. The English-controlled area shrank back to the Pale

, a fortified area around Dublin. Outside the Pale, the Hiberno-Norman

lords intermarried with Gaelic noble families, adopted the Irish language and customs and sided with the Gaelic Irish in political and military conflicts against the Lordship. They became known as the Old English

, and in the words of a contemporary English commentator, were "more Irish than the Irish themselves

."

The authorities in the Pale worried about the "Gaelicisation" of Norman Ireland, and passed the Statutes of Kilkenny

in 1366 banning those of English descent from speaking the Irish language

, wearing Irish clothes or inter-marrying with the Irish. The government in Dublin had little real authority. By the end of the fifteenth century, central English authority in Ireland had all but disappeared. England's attentions were diverted by the Hundred Years' War

(1337–1453) and then by the Wars of the Roses

(1450–85). Around the country, local Gaelic and Gaelicised lords expanded their powers at the expense of the English government in Dublin.

(see Irish Bruce Wars 1315–1318) to drive the Normans out of Ireland, there emerged a number of important Gaelic kingdoms and Gaelic-controlled lordships.

decided to conquer Ireland and bring it under English control. The FitzGerald dynasty of Kildare

, who had become the effective rulers of the Lordship of Ireland (The Pale

) in the 15th century, had become unreliable allies and Henry resolved to bring Ireland under English government control so the island would not become a base for future rebellions or foreign invasions of England. To involve the Gaelic nobility

and allow them to retain their lands under English law the policy of surrender and regrant

was applied.

In 1541, Henry upgraded Ireland from a lordship to a full kingdom

, partly in response to changing relationships with the papacy, which still had suzerainty over Ireland, following Henry's break with the church. Henry was proclaimed King of Ireland at a meeting of the Irish Parliament that year. This was the first meeting of the Irish Parliament to be attended by the Gaelic Irish princes as well as the Hiberno-Norman

aristocracy.

With the technical institutions of government in place, the next step was to extend the control of the Kingdom of Ireland over all of its claimed territory. This took nearly a century, with various English administrations in the process either negotiating or fighting with the independent Irish and Old English lords. The conquest was completed during the reigns of Elizabeth

and James I

, after several bloody conflicts.

The flight into exile in 1607 of Hugh O'Neill, 2nd Earl of Tyrone and Rory O'Donnell, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell

following their defeat at the Battle of Kinsale in 1601 and the suppression of their rebellion in Ulster

in 1603 is seen as the watershed of Gaelic Ireland. It marked the destruction of Ireland's ancient Gaelic nobility

following the Tudor conquest and cleared the way for the Plantation of Ulster

. After this point, the English authorities in Dublin established real control over Ireland for the first time, bringing a centralised government to the entire island, and successfully disarmed the Gaelic lordships.

Gaels

The Gaels or Goidels are speakers of one of the Goidelic Celtic languages: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx. Goidelic speech originated in Ireland and subsequently spread to western and northern Scotland and the Isle of Man....

political order existed in Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

. The order continued to exist after the arrival of the Anglo-Normans

Normans

The Normans were the people who gave their name to Normandy, a region in northern France. They were descended from Norse Viking conquerors of the territory and the native population of Frankish and Gallo-Roman stock...

(1169 AD) until about 1607 AD. For much of this period, the island was a patchwork of kingdoms of various size and other semi-sovereign territories known as túath

Tuath

Túath is an Old Irish word, often translated as "people" or "nation". It is cognate with the Welsh and Breton tud , and with the Germanic þeudō ....

a, much like the situation in Medieval Germany

Medieval Germany

Medieval Germany:*Carolingian Empire *East Francia *Kingdom of Germany *German Late Middle Ages...

but in most periods without any effective national overlordship. These kingdoms and túatha very frequently competed for control of resources and thus continually grew and receded with the fortunes of time. Thousands of battles and predatory excursions involving their leaders are recorded in the Irish annals

Irish annals

A number of Irish annals were compiled up to and shortly after the end of Gaelic Ireland in the 17th century.Annals were originally a means by which monks determined the yearly chronology of feast days...

and other sources.

After the Norman invasion

Norman Invasion of Ireland

The Norman invasion of Ireland was a two-stage process, which began on 1 May 1169 when a force of loosely associated Norman knights landed near Bannow, County Wexford...

of 1169–71, large portions of Ireland came under the control of Norman lords – this territory was known as the Lordship of Ireland

Lordship of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland refers to that part of Ireland that was under the rule of the king of England, styled Lord of Ireland, between 1177 and 1541. It was created in the wake of the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169–71 and was succeeded by the Kingdom of Ireland...

. However, the Gaelic system continued to exist in areas outside Norman control, and the government

Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland was a legislature that existed in Dublin from 1297 until 1800. In its early mediaeval period during the Lordship of Ireland it consisted of either two or three chambers: the House of Commons, elected by a very restricted suffrage, the House of Lords in which the lords...

's power gradually shrank to an area known as The Pale

The Pale

The Pale or the English Pale , was the part of Ireland that was directly under the control of the English government in the late Middle Ages. It had reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast stretching from Dalkey, south of Dublin, to the garrison town of Dundalk...

. In 1541 the Kingdom of Ireland

Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland refers to the country of Ireland in the period between the proclamation of Henry VIII as King of Ireland by the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 and the Act of Union in 1800. It replaced the Lordship of Ireland, which had been created in 1171...

was established and the English monarchy began to conquer the island. This resulted in the Flight of the Earls

Flight of the Earls

The Flight of the Earls took place on 14 September 1607, when Hugh Ó Neill of Tír Eóghain, Rory Ó Donnell of Tír Chonaill and about ninety followers left Ireland for mainland Europe.-Background to the exile:...

in 1607, which marked the end of the Gaelic order.

Culture and society

Gaelic culture and society was centered around the Fine (clanClan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clan members may be organized around a founding member or apical ancestor. The kinship-based bonds may be symbolical, whereby the clan shares a "stipulated" common ancestor that is a...

n) and, as such, the landscape and history of Ireland was wrought with inter-fine relationships, marriages, friendships, wars, vendettas, trading, and so on. Despite this, Gaelic Ireland possessed a rich oral culture and appreciation of deeper and intellectual pursuits. Filidh and druids were held in high regard during pagan

Celtic polytheism

Celtic polytheism, commonly known as Celtic paganism, refers to the religious beliefs and practices adhered to by the Iron Age peoples of Western Europe now known as the Celts, roughly between 500 BCE and 500 CE, spanning the La Tène period and the Roman era, and in the case of the Insular Celts...

times and carried the oral history and traditions of their people throughout generations. Later, many of the spiritual and intellectual tasks they carried out were passed down to Christian monks, after said religion prevailed from the 5th century onwards. However, the filidh continued to hold a high position in their clanns and territories. Poetry, music, storytelling, literature and various forms of arts were highly prized and cultivated in both pagan and Christian Gaelic Ireland. Hospitality, bonds of kinship and the fulfilment of social and ritual responsibilities were held sacred.

The Gaelic order in Ireland, rather than a single unified kingdom in the feudal sense, was a patchwork of túath

Tuath

Túath is an Old Irish word, often translated as "people" or "nation". It is cognate with the Welsh and Breton tud , and with the Germanic þeudō ....

a (singular: túath). These túatha often competed for control of resources and thus continually grew and shrank. Law tracts from the beginning of the eight century describe a hierarchy of kings: kings of túath subject to kings of several túatha who again were subject to provincial over kings. Already before the 8th century these over-kingships had begun to dissolve the túatha as the basic sociopolitic unit.

Religion and mythology

Paganism

Before Christianisation, the religion of the Gaelic Irish, as with other Celts, can be described as polytheistic or paganPaganism

Paganism is a blanket term, typically used to refer to non-Abrahamic, indigenous polytheistic religious traditions....

. They worshipped a variety of gods and goddesses, which generally have parallels in the pantheons of other Celts. They were also animists

Animism

Animism refers to the belief that non-human entities are spiritual beings, or at least embody some kind of life-principle....

, believing that all aspects of the natural world contained spirits, and that these spirits could be communicated with. Burial practices –which included burying food, weapons, and ornaments with the dead– suggest a belief in life after death

Afterlife

The afterlife is the belief that a part of, or essence of, or soul of an individual, which carries with it and confers personal identity, survives the death of the body of this world and this lifetime, by natural or supernatural means, in contrast to the belief in eternal...

. Some have equated this afterlife with the realms known as Mag Mell

Mag Mell

In Irish mythology, Mag Mell was a mythical realm achievable through death and/or glory...

and Tír na nÓg

Tír na nÓg

Tír na nÓg is the most popular of the Otherworlds in Irish mythology. It is perhaps best known from the story of Oisín, one of the few mortals who lived there, who was said to have been brought there by Niamh of the Golden Hair. It was where the Tuatha Dé Danann settled when they left Ireland's...

in Irish mythology. There were four major religious festivals each year, marking the traditional four divisions of the year – Imbolc

Imbolc

Imbolc , or St Brigid’s Day , is an Irish festival marking the beginning of spring. Most commonly it is celebrated on 1 or 2 February in the northern hemisphere and 1 August in the southern hemisphere...

, Beltaine, Lughnasadh

Lughnasadh

Lughnasadh is a traditional Gaelic holiday celebrated on 1 August. It is in origin a harvest festival, corresponding to the Welsh Calan Awst and the English Lammas.-Name:...

and Samhain

Samhain

Samhain is a Gaelic harvest festival held on October 31–November 1. It was linked to festivals held around the same time in other Celtic cultures, and was popularised as the "Celtic New Year" from the late 19th century, following Sir John Rhys and Sir James Frazer...

.

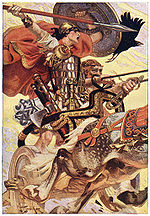

The mythology of Ireland did not entirely survive the conversion to Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

, but much of it was preserved, shorn of its religious meanings, in medieval Irish literature. This large body of work is typically divided into three overlapping cycles: the Mythological Cycle

Mythological Cycle

The Mythological Cycle is one of the four major cycles of Irish mythology, and is so called because it represents the remains of the pagan mythology of pre-Christian Ireland, although the gods and supernatural beings have been euhemerised into historical kings and heroes.The cycle consists of...

, the Ulster Cycle

Ulster Cycle

The Ulster Cycle , formerly known as the Red Branch Cycle, one of the four great cycles of Irish mythology, is a body of medieval Irish heroic legends and sagas of the traditional heroes of the Ulaid in what is now eastern Ulster and northern Leinster, particularly counties Armagh, Down and...

, and the Fenian Cycle

Fenian Cycle

The Fenian Cycle , also referred to as the Ossianic Cycle after its narrator Oisín, is a body of prose and verse centering on the exploits of the mythical hero Fionn mac Cumhaill and his warriors the Fianna. It is one of the four major cycles of Irish mythology along with the Mythological Cycle,...

. The first cycle is a pseudo-history of Ireland that describes four invasions (or migrations) by semi-divine peoples. Two of these groups, the Fomorians

Fomorians

In Irish mythology, the Fomoire are a semi-divine race said to have inhabited Ireland in ancient times. They may have once been believed to be the beings who preceded the gods, similar to the Greek Titans. It has been suggested that they represent the gods of chaos and wild nature, as opposed to...

and Tuatha Dé Danann

Tuatha Dé Danann

The Tuatha Dé Danann are a race of people in Irish mythology. In the invasions tradition which begins with the Lebor Gabála Érenn, they are the fifth group to settle Ireland, conquering the island from the Fir Bolg....

, are believed to represent the pre-Gaelic and Gaelic pantheons

Pantheon (gods)

A pantheon is a set of all the gods of a particular polytheistic religion or mythology.Max Weber's 1922 opus, Economy and Society discusses the link between a...

. The second cycle recounts the lives and deaths of Ulaid

Ulaid

The Ulaid or Ulaidh were a people of early Ireland who gave their name to the modern province of Ulster...

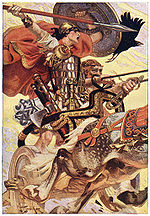

heroes such as Cúchulainn

Cúchulainn

Cú Chulainn or Cúchulainn , and sometimes known in English as Cuhullin , is an Irish mythological hero who appears in the stories of the Ulster Cycle, as well as in Scottish and Manx folklore...

. The third cycle recounts the exploits of Fionn mac Cumhaill

Fionn mac Cumhaill

Fionn mac Cumhaill , known in English as Finn McCool, was a mythical hunter-warrior of Irish mythology, occurring also in the mythologies of Scotland and the Isle of Man...

and the Fianna

Fianna

Fianna were small, semi-independent warrior bands in Irish mythology and Scottish mythology, most notably in the stories of the Fenian Cycle, where they are led by Fionn mac Cumhaill....

. There are also a number of stories that do not fit into these cycles – this includes the immrama and echtrai, which are tales of the 'otherworld

Otherworld

Otherworld, or the Celtic Otherworld, is a concept in Celtic mythology that refers to the home of the deities or spirits, or a realm of the dead.Otherworld may also refer to:In film and television:...

' and the voyages to get there.

Christianity

Law

Gaelic law (collectively known as Fénechas) was originally passed down orally, but was written down in Old Irish during the period 600–900 AD. Most of the laws were developed before Christianisation and are largely secular, but there is some Christian influence. These secular laws existed in parallel, and occasionally in conflict, with Church lawCanon law (Catholic Church)

The canon law of the Catholic Church, is a fully developed legal system, with all the necessary elements: courts, lawyers, judges, a fully articulated legal code and principles of legal interpretation. It lacks the necessary binding force present in most modern day legal systems. The academic...

. The brithem were the judiciary

Judiciary

The judiciary is the system of courts that interprets and applies the law in the name of the state. The judiciary also provides a mechanism for the resolution of disputes...

in Gaelic society and were expected to interpret the written laws and give advice or pass judgement accordingly. Kings would have been able to pass judgement also, but it is unclear how much they would have been able to make their own judgments, and how much they would have had to rely on professionals. However, unlike other kingdoms in Europe, Gaelic kings—by their own authority—could not enact new laws as they wished and could not be "above the law".

Private law

Private law is that part of a civil law legal system which is part of the jus commune that involves relationships between individuals, such as the law of contracts or torts, as it is called in the common law, and the law of obligations as it is called in civilian legal systems...

rather than a criminal

Criminal law

Criminal law, is the body of law that relates to crime. It might be defined as the body of rules that defines conduct that is not allowed because it is held to threaten, harm or endanger the safety and welfare of people, and that sets out the punishment to be imposed on people who do not obey...

code, concerned with the payment of fines (dire) for harm done. Although Gaelic law recognized a distinction between intentional and unintentional injury, any type of injury required compensation. The legal text Bretha Déin Chécht goes into great detail in describing compensation based on the location, severity, and type of wound. Types of fines included coirpdire (body-fine), einachlan (honour-price) and éraic (reparation). The éraic was the fine for murder

Murder

Murder is the unlawful killing, with malice aforethought, of another human being, and generally this state of mind distinguishes murder from other forms of unlawful homicide...

or manslaughter

Manslaughter

Manslaughter is a legal term for the killing of a human being, in a manner considered by law as less culpable than murder. The distinction between murder and manslaughter is said to have first been made by the Ancient Athenian lawmaker Dracon in the 7th century BC.The law generally differentiates...

; the fine for murder being twice that for manslaughter. State-administered punishment for crime was a foreign concept. Criminals were summoned to appear before a brithem, who heard the case and assessed the amount of fine that should be paid. If the defendant did not pay outright, his property was seized

Distraint

Distraint or distress is "the seizure of someone’s property in order to obtain payment of rent or other money owed", especially in common law countries...

until he did so. Should the offender be unable to pay, his family would be responsible for doing so. Should the family be unable or unwilling to pay, responsibility would extend to the wider fine. If the criminal died, and his crime was purely personal, the fine would be freed of liability. However, if the criminal died and his crime had caused damage/loss of property, the fine was still liable for this loss. Hence, it has been argued that "the people were their own police".

Punishment was adjusted to match one's rank or profession. In certain cases, those of higher rank could receive a higher amount of compensation. However, an offence against the property of a poor man (who could ill afford it), was punished more harshly than a similar offence upon a wealthy man. The clergy

Clergy

Clergy is the generic term used to describe the formal religious leadership within a given religion. A clergyman, churchman or cleric is a member of the clergy, especially one who is a priest, preacher, pastor, or other religious professional....

were more harshly punished than the laity

Laity

In religious organizations, the laity comprises all people who are not in the clergy. A person who is a member of a religious order who is not ordained legitimate clergy is considered as a member of the laity, even though they are members of a religious order .In the past in Christian cultures, the...

. When a layman had paid his fine he would go through a probationary period and then regain his status, but a convicted clergyman could never regain his status.

It is generally believed that execution

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

of criminals was rare. If a murderer was unable/unwilling to pay éraic and was surrendered to his victim's family, they might kill him if they pleased should nobody intervene by paying the éraic. Certain criminals might be expelled from the fine and its territory, even though the fine had been paid. Such people became outlaws (with no protection from the law) and anyone who sheltered him became liable for his crimes. If he still haunted the fine territory and continued his crimes there, he was proclaimed in the fines public assembly and after this anyone might lawfully kill him.

The law texts take great care to define social status, the rights and duties that went with that status, and the relationships between people. For example, chieftains had to take responsibility for members of their fine, acting as a surety

Surety

A surety or guarantee, in finance, is a promise by one party to assume responsibility for the debt obligation of a borrower if that borrower defaults...

for some of the actions of members and making sure debts were paid. He would also be responsible for unmarried women after the death of their fathers.

Structure

Clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clan members may be organized around a founding member or apical ancestor. The kinship-based bonds may be symbolical, whereby the clan shares a "stipulated" common ancestor that is a...

n (plural: clanna) or fine (plural: finte). Each clann was a large group of related people—theoretically an extended family—supposedly descended from one progenitor and all owing allegiance to its chieftain, known as a cennfine or toísech

Taoiseach

The Taoiseach is the head of government or prime minister of Ireland. The Taoiseach is appointed by the President upon the nomination of Dáil Éireann, the lower house of the Oireachtas , and must, in order to remain in office, retain the support of a majority in the Dáil.The current Taoiseach is...

(plural: toísigh). Often, clanna are thought of as based on blood kinship alone; however, clanna also included those who were adopted or fostered into the clann, and those who joined the clann for strategic reasons (such as safety or combining of resources). As Nicholls describes, they would be better thought of as akin to the modern-day corporation

Corporation

A corporation is created under the laws of a state as a separate legal entity that has privileges and liabilities that are distinct from those of its members. There are many different forms of corporations, most of which are used to conduct business. Early corporations were established by charter...

. The power of clanna fluctuated, and endemic warfare

Endemic warfare

Endemic warfare is the state of continual, low-threshold warfare in a tribal warrior society. Endemic warfare is often highly ritualized and plays an important function in assisting the formation of a social structure among the tribes' men by proving themselves in battle.Ritual fighting permits...

between clanna was a constant affair. Once-powerful clanna could in time decline in stature and be amalgamated into once-smaller ones. How this "merger" would be dealt with would be a matter of negotiation. Many clanna were also divided into a number of sub-groups known as septs

Sept (social)

A sept is an English word for a division of a family, especially a division of a clan. The word might have its origin from Latin saeptum "enclosure, fold", or it can be an alteration of sect.The term is found in both Ireland and Scotland...

, often when that group took up residence outside the original clann territory.

Lineage was based on the practice of tanistry

Tanistry

Tanistry was a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands. In this system the Tanist was the office of heir-apparent, or second-in-command, among the Gaelic patrilineal dynasties of Ireland, Scotland and Man, to succeed to the chieftainship or to the kingship.-Origins:The Tanist was chosen from...

(rather than primogeniture

Primogeniture

Primogeniture is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn to inherit the entire estate, to the exclusion of younger siblings . Historically, the term implied male primogeniture, to the exclusion of females...

). At an assembly called a tocomra a relative was elected—prior to the death of a leader—to act as his deputy and then his successor. To be eligible for election, one had to share the same great-grandfather as the toísech. This group of electable cousins was called the derbfine

Derbfine

The derbfine was an Irish agnatic kinship group and power structure as defined in the law tracts of the eighth century. Its principal purpose was as an institution of property inheritance, with property redistributed on the death of a member to those remaining members of the derbfine...

, and the elected person was called a tanaiste

Tánaiste

The Tánaiste is the deputy prime minister of Ireland. The current Tánaiste is Eamon Gilmore, TD who was appointed on 9 March 2011.- Origins and etymology :...

(plural: tanaistí). The clann system formed the basis of society.

Gaelic society was structured hierarchically

Hierarchy

A hierarchy is an arrangement of items in which the items are represented as being "above," "below," or "at the same level as" one another...

.

- The top social layer was the nobility (nemed), which included kings or ríRíRí, or very commonly ríg , is an ancient Gaelic word meaning "King". It is used in historical texts referring to the Irish and Scottish kings and those of similar rank. While the modern Irish word is exactly the same, in modern Scottish it is Rìgh, apparently derived from the genitive. The word...

, princes or flatha, lords or tiarnaí, and chieftains (toísigh). See also Gaelic nobility of Ireland for their surviving modern descendants.

- Below that were the professionals (dóernemed), which included skilled poets (filiFiliA fili was a member of an elite class of poets in Ireland, up into the Renaissance, when the Irish class system was dismantled.-Elite scholars:According to the Textbook of Irish Literature, by Eleanor Hull:-Oral tradition:...

d), judges (brithem), craftsmen, physicians, and so on. Masters in a particular profession were known as ollamOllamIn Irish, Ollam or Ollamh , is a master in a particular trade or skill. In early Irish Literature, it generally refers to the highest rank of Fili; it could also modify other terms to refer to the highest member of any group: thus an ollam brithem would be the highest rank of judge and an ollam rí...

h. The various professions—including law, poetry, medicine, history and genealogy—were associated with particular hereditary families. Although most practised only one profession, some exercised more than one. Prior to the Christianisation of Ireland, this group also included the druídechtDruidA druid was a member of the priestly class in Britain, Ireland, and Gaul, and possibly other parts of Celtic western Europe, during the Iron Age....

and fáitheVatesThe earliest Latin writers used vātēs to denote "prophets" and soothsayers in general; the word fell into disuse in Latin until it was revived by Virgil...

. The druídecht or druids could combine the duties of priest, judge, scholar, poet, physician, and religious teacher, while the fáithe acted as soothsayerFortune-tellingFortune-telling is the practice of predicting information about a person's life. The scope of fortune-telling is in principle identical with the practice of divination...

s and clairvoyantsClairvoyanceThe term clairvoyance is used to refer to the ability to gain information about an object, person, location or physical event through means other than the known human senses, a form of extra-sensory perception...

.

- Below that were those who owned land and cattle (bóaireBoaireBóaire was a title given to a member of medieval and earlier Gaelic societies prior to the introductions of English law according to Early Irish law. The terms means a "Cow lord". Despite this a Bóaire was a "free-holder", and ranked below the noble grades but above the unfree...

).

- Below that were serfSERFA spin exchange relaxation-free magnetometer is a type of magnetometer developed at Princeton University in the early 2000s. SERF magnetometers measure magnetic fields by using lasers to detect the interaction between alkali metal atoms in a vapor and the magnetic field.The name for the technique...

s (bothach) and slaves (mug). Slaves were typically criminals or prisoners of war.

- The warrior bands (fiannaFiannaFianna were small, semi-independent warrior bands in Irish mythology and Scottish mythology, most notably in the stories of the Fenian Cycle, where they are led by Fionn mac Cumhaill....

) generally lived apart from society. A fian was typically composed of young men who had not yet come into their inheritanceInheritanceInheritance is the practice of passing on property, titles, debts, rights and obligations upon the death of an individual. It has long played an important role in human societies...

of land. A member of a fian was called a fénnid and the leader of a fian was a rígfénnid. Geoffrey KeatingGeoffrey KeatingSeathrún Céitinn, known in English as Geoffrey Keating, was a 17th century Irish Roman Catholic priest, poet and historian. He was born in County Tipperary c. 1569, and died c. 1644...

, in his 17th century History of Ireland, says that during the winter the fianna were quartered and fed by the nobility, during which time they would keep order on their behalf. But during the summer, from Beltaine to SamhainSamhainSamhain is a Gaelic harvest festival held on October 31–November 1. It was linked to festivals held around the same time in other Celtic cultures, and was popularised as the "Celtic New Year" from the late 19th century, following Sir John Rhys and Sir James Frazer...

, they were obliged to live by hunting for food and for pelts to sell.

Although quite distinct, these ranks were not utterly exclusive caste

Caste

Caste is an elaborate and complex social system that combines elements of endogamy, occupation, culture, social class, tribal affiliation and political power. It should not be confused with race or social class, e.g. members of different castes in one society may belong to the same race, as in India...

s like those of India. It was possible for persons to rise or sink from one rank to another. Progressing upward could be achieved a number of ways, such as by gaining wealth, by gaining skill in some department, by qualifying for a learned profession, by displaying conspicuous valour, or by performing some signal service to the community. An example is a person choosing to become a briugu (hospitaller). A briugu had to have his house open to any guests, which included feeding no matter how large the group. To enable the briugu to fulfill these duties, he was allowed more land and privileges, but if he ever refused guests he could lose this status.

Marriage, women and children

Commenting on the general view of women, Richard Stanihurst wrote in 1584 that at Irish social gatherings, "the prime place at the table is bestowed upon the woman of the household".Apparently the laws on marriage and divorce were wholly pagan, and never underwent any change in Christian times. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Gaelic Irish kept many of their marriage laws and traditions separate from those of the Church.

Under Gaelic law, married women could hold property independent of their husbands, the tie between married women and their own families was kept intact, couples could easily divorce/separate, and men could have concubines

Concubinage

Concubinage is the state of a woman or man in an ongoing, usually matrimonially oriented, relationship with somebody to whom they cannot be married, often because of a difference in social status or economic condition.-Concubinage:...

(which could be lawfully bought). These laws differed from most of contemporary Europe and from Church law.

The lawful age of marriage was fifteen for girls and eighteen for boys. Upon marriage, the families of the bride and bridegroom were expected to contribute to the match. It was the custom for the bridegroom and his family to pay a coibche and the bride was allowed a portion of it. If the marriage ended due to a fault of the husband then the coibche was kept by the wife and her family, but if the fault lay with the wife then the coibche was to be returned. It was customary for the bride to receive a spréidh from her family (or foster family) upon marriage. This was to be returned if the marriage ended through divorce or the death of the husband. Later, the spréidh seems to have been converted into a dowry

Dowry

A dowry is the money, goods, or estate that a woman brings forth to the marriage. It contrasts with bride price, which is paid to the bride's parents, and dower, which is property settled on the bride herself by the groom at the time of marriage. The same culture may simultaneously practice both...

. Women could seek divorce/separation as easily as men could and, when obtained on her petition, she kept all the property she had brought her husband during their marriage.

Trial marriages seem to have been popular among the rich and powerful, and thus it has been argued that cohabitation

Cohabitation

Cohabitation usually refers to an arrangement whereby two people decide to live together on a long-term or permanent basis in an emotionally and/or sexually intimate relationship. The term is most frequently applied to couples who are not married...

before marriage must have been acceptable. It also seems that the wife of a chieftain was entitled to some share of the chief's authority over his territory. This led to some Gaelic Irish wives wielding a great deal of political power.

In Gaelic Ireland a type of fosterage

Fosterage

Fosterage, the practice of a family bringing up a child not their own, differs from adoption in that the child's parents, not the foster-parents, remain the acknowledged parents. In many modern western societies foster care can be organised by the state to care for children with troubled family...

was commonplace, whereby (for certain periods of time) children would be placed in the care of other fine members, namely their mother's family, preferably her brother. This may have been used to strengthen family ties or political bonds. Foster parents were required to teach their foster children or to have them taught. Foster parents who had properly done their duties were entitled to be supported by their foster children in old age (if they were in need and had no children of their own). As with divorce, Gaelic law again differed from most of Europe and from Church law in giving legal status to both "legitimate" and "illegitimate"

Legitimacy (law)

At common law, legitimacy is the status of a child who is born to parents who are legally married to one another; and of a child who is born shortly after the parents' divorce. In canon and in civil law, the offspring of putative marriages have been considered legitimate children...

children.

Settlements and architecture

Wattle and daub

Wattle and daub is a composite building material used for making walls, in which a woven lattice of wooden strips called wattle is daubed with a sticky material usually made of some combination of wet soil, clay, sand, animal dung and straw...

, timber, sods, clay, or a mix of materials. Roofs were made of thatch or sods. These houses (along with livestock) were often surrounded by a circular rampart

Circular rampart

A circular rampart is an embankment built in the shape of a circle that was used as part of the defences for a military fortification, hill fort or refuge, or was built for religious purposes or as a place of gathering....

called a "ringfort

Ringfort

Ringforts are circular fortified settlements that were mostly built during the Iron Age , although some were built as late as the Early Middle Ages . They are found in Northern Europe, especially in Ireland...

". There are two main types of ringfort. The ráth is an earthen ringfort, averaging 30m diameter, with a dry outside ditch. The cathair or caiseal is a stone ringfort. Sometimes there were several buildings inside. Most date to the period 500–1000 CE and there is evidence of large-scale ringfort desertion at the end of the first millennium. Between 30,000 and 40,000 survived into the 19th century to be mapped by Ordnance Survey Ireland

Ordnance Survey Ireland

Ordnance Survey Ireland is the national mapping agency of the Republic of Ireland and, together with the Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland , succeeded, after 1922, the Irish operations of the United Kingdom Ordnance Survey. It is part of the Public service of the Republic of Ireland...

. Another type of native dwelling was the crannóg

Crannog

A crannog is typically a partially or entirely artificial island, usually built in lakes, rivers and estuarine waters of Scotland and Ireland. Crannogs were used as dwellings over five millennia from the European Neolithic Period, to as late as the 17th/early 18th century although in Scotland,...

, which were fortified roundhouses built on wooden platforms in lakes.

Monastic settlements emerged in the 5th century. Although there were no town

Town

A town is a human settlement larger than a village but smaller than a city. The size a settlement must be in order to be called a "town" varies considerably in different parts of the world, so that, for example, many American "small towns" seem to British people to be no more than villages, while...

s or village

Village

A village is a clustered human settlement or community, larger than a hamlet with the population ranging from a few hundred to a few thousand , Though often located in rural areas, the term urban village is also applied to certain urban neighbourhoods, such as the West Village in Manhattan, New...

s, the monasteries sometimes became the centre of a small settlement cluster or "monastic town". By the 10th century, there were few nucleated settlements other than these monastic towns and the Norse-Gaelic

Norse-Gaels

The Norse–Gaels were a people who dominated much of the Irish Sea region, including the Isle of Man, and western Scotland for a part of the Middle Ages; they were of Gaelic and Scandinavian origin and as a whole exhibited a great deal of Gaelic and Norse cultural syncretism...

ports. It was at this time, perhaps as a response to Viking raids, that many of the Irish round tower

Irish round tower

Irish round towers , Cloigthithe – literally "bell house") are early medieval stone towers of a type found mainly in Ireland, with three in Scotland and one on the Isle of Man...

s were built.

In the fifty years before the Norman invasion (1169), the term "castle" appears in Gaelic writings, although all the recorded examples of pre-Norman castles have been destroyed. After the invasion, the Normans converted some ringforts into motte-and-bailey

Motte-and-bailey

A motte-and-bailey is a form of castle, with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised earthwork called a motte, accompanied by an enclosed courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade...

s. From the mid 14th century onward, the Normans began to build tower house

Tower house

A tower house is a particular type of stone structure, built for defensive purposes as well as habitation.-History:Tower houses began to appear in the Middle Ages, especially in mountain or limited access areas, in order to command and defend strategic points with reduced forces...

s in large numbers. These are free-standing multi-storey stone towers usually surrounded by a wall (see bawn

Bawn

A bawn is the defensive wall surrounding an Irish tower house. It is the anglicised version of the Irish word badhún meaning "cattle-stronghold" or "cattle-enclosure". The Irish word for "cow" is bó and its plural is ba...

) and ancillary buildings. Gaelic families had begun to build their own tower houses by the 15th century. As many as 7000 may have been built, but they were rare in areas with little Norman settlement or contact. They are concentrated in counties Limerick and Clare but are lacking in Ulster, except the area around Strangford Lough

Strangford Lough

Strangford Lough, sometimes Strangford Loch, is a large sea loch or inlet in County Down, Northern Ireland. It is separated from the Irish Sea by the Ards Peninsula. The name Strangford is derived ; describing the fast-flowing narrows at its mouth...

.

In Gaelic law, a 'sanctuary' called a maighin digona surrounded each person's dwelling. Within this the owner and his family and property were protected by law. The maighin digona's size varied according to the owner's rank. In the case of a bóaire

Boaire

Bóaire was a title given to a member of medieval and earlier Gaelic societies prior to the introductions of English law according to Early Irish law. The terms means a "Cow lord". Despite this a Bóaire was a "free-holder", and ranked below the noble grades but above the unfree...

it extended as far as he, while sitting at his house, could cast a cnairsech (variously described as a spear or sledgehammer). The owner of a maighin digona could extend its protection to someone fleeing from pursuers, who would then have to resort to legal methods of bringing that person to justice.

Sustenance

Money was non-existent in Gaelic society; instead, livestockLivestock

Livestock refers to one or more domesticated animals raised in an agricultural setting to produce commodities such as food, fiber and labor. The term "livestock" as used in this article does not include poultry or farmed fish; however the inclusion of these, especially poultry, within the meaning...

(cows, sheep, pigs and horses) and fishing

Fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch wild fish. Fish are normally caught in the wild. Techniques for catching fish include hand gathering, spearing, netting, angling and trapping....

was the main currency and the main source of sustenance. Horticulture

Horticulture

Horticulture is the industry and science of plant cultivation including the process of preparing soil for the planting of seeds, tubers, or cuttings. Horticulturists work and conduct research in the disciplines of plant propagation and cultivation, crop production, plant breeding and genetic...

was practiced; the main crops being oats, wheat and barley, although flax was also grown for making linen. The main exports were fish, hides, wool and linen cloth. The main imports were goods that could not be found in Ireland, such as salt and wine.

Transhumance

Transhumance

Transhumance is the seasonal movement of people with their livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and to lower valleys in winter. Herders have a permanent home, typically in valleys. Only the herds travel, with...

was practised, whereby the people moved with their livestock (over short distances) to higher pasture

Pasture

Pasture is land used for grazing. Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, cattle, sheep or swine. The vegetation of tended pasture, forage, consists mainly of grasses, with an interspersion of legumes and other forbs...

s in summer and back to lower pastures in the cooler months. The summer pasture was called the buaile (anglicised as booley) and it is significant that the Irish word for boy (buachaill) originally meant a herdsman. Many moorland

Moorland

Moorland or moor is a type of habitat, in the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome, found in upland areas, characterised by low-growing vegetation on acidic soils and heavy fog...

areas were "shared as a common summer pasturage

Common land

Common land is land owned collectively or by one person, but over which other people have certain traditional rights, such as to allow their livestock to graze upon it, to collect firewood, or to cut turf for fuel...

by the people of a whole parish or barony".

Dress

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

, the common clothing amongst the Gaelic Irish consisted of a brat (a woollen cloak or mantle) worn over a léine (a loose-fitting, long-sleeved tunic made of wool or linen). For men these were either thigh-length or knee-length and for women they were longer. Men sometimes wore tight-fitting truis

Trews

Trews are men's clothing for the legs and lower abdomen, a traditional form of tartan trousers from Scottish apparel...

on the legs, but otherwise went bare-legged. The brat was usually fastened with a crios (belt

Belt (clothing)

A belt is a flexible band or strap, typically made of leather or heavy cloth, and worn around the waist. A belt supports trousers or other articles of clothing.-History:...

) and dealg (brooch

Celtic brooch

The Celtic brooch, more properly called the penannular brooch, and its closely related type, the pseudo-penannular brooch, are types of brooch clothes fasteners, often rather large...

), with men usually wearing the dealg at their shoulders and women at their chests. The ionar (a short, tight-fitting jacket) became popular later on. In Topographia Hibernica

Topographia Hibernica

Topographia Hibernica , also known as Topographia Hiberniae, is an account of the landscape and people of Ireland written by Gerald of Wales around 1188, soon after the Norman invasion of Ireland...

, written during the 1180s, Gerald de Barri wrote that the Irish also wore hoods at that time (perhaps forming part of the brat), while Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser was an English poet best known for The Faerie Queene, an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognised as one of the premier craftsmen of Modern English verse in its infancy, and one of the greatest poets in the English...

wrote in the 1580s that the brat was (in general) their sole garment.

According to Gerald de Barri, most of the Irish wore clothes made of black wool, because most of the sheep in Ireland were black in his time. The number of colours worn came to indicate the rank or wealth of the wearer; the wealthy often wore cloth of many colours while the poor only wore cloth of one colour.

Both men and women grew their hair long and often braid

Braid

A braid is a complex structure or pattern formed by intertwining three or more strands of flexible material such as textile fibres, wire, or human hair...

ed it. It is claimed that the Gaelic Irish took great pride in their long hair—for example, a person could be forced to pay the heavy fine of two cows for shaving a man's head against his will. The glib (short all over except for a thick lock of hair towards the front of the head) was also popular among some medieval Gaels, and the mohawk

Mohawk hairstyle

The mohawk is a hairstyle in which, in the most common variety, both sides of the head are shaven, leaving a strip of noticeably longer hair...

may have been popular in pre-Christian times (as worn by the Irish bog body

Bog body

Bog bodies, which are also known as bog people, are the naturally preserved human corpses found in the sphagnum bogs in Northern Europe. Unlike most ancient human remains, bog bodies have retained their skin and internal organs due to the unusual conditions of the surrounding area...

known as Clonycavan man

Clonycavan Man