History of Panama

Encyclopedia

The History of Panama is about the Isthmus of Panama

region's long history that occurred in southern Central America

, from Pre-Columbian

cultures, during the Spanish colonial era, through independence and the current country of Panama

.

in Panama have included Paleo-Indians projectile point

s. Later central Panama was home to some of the first pottery

-making in the Americas

, such as the Monagrillo

cultures dating to about 2500-1700 BCE. These evolved into significant populations that are best known through the spectacular burials (dating to c. 500-900 CE) at the Monagrillo archaeological site

, and the beautiful polychrome pottery of the Gran Coclé

style. The monumental monolith

ic sculptures at the Barriles

(Chiriqui) site are other important evidence of the ancient isthmian cultures.

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Panama was widely settled by Chibchan, Chocoan, and Cueva

peoples, among whom the largest group were the Cueva (whose specific language affiliation is poorly documented). There is no accurate knowledge of size of the Pre-Columbian indigenous population of the isthmus at the time of the European conquest. Estimates range as high as two million people, but more recent studies place that number closer to 200,000. Archeological finds as well as testimonials by early European explorers describe diverse native isthmian groups exhibiting cultural variety and already experienced in using regional trade route

s. The indigenous people of Panama lived by hunting, gathering edible plants & fruits, growing corn, cacao, and root crops. They lived in small huts made of palm leaves over a rounded branch structure, with hammocks hung between the interior walls for sleeping.

was the first European to explore the Isthmus of Panama

sailing along the eastern coast. A year later Christopher Columbus

, sailing south and eastward from upper Central America, explored Bocas del Toro

, Veragua

, the Chagres River

and Porto Belo

(Beautiful Port) which he named. Soon Spanish expeditions would converge upon Tierra Firma (also Tierra Firme, Spanish from the Latin terra firma, "dry land" or "mainland") which served in Spanish colonial times as the name for the Isthmus of Panama

In 1509, authority was granted to Alonso de Ojeda and Diego de Nicuesa to colonize the territories between the west side of the Gulf of Uraba to Cabo Gracias a Dios in present-day Honduras. The idea was to create an early unitary administrative organization similar to what later became Nueva España (now Mexico). Tierra Firme later received control over other territories: the Isla de Santiago (now Jamaica) the Cayman Islands; Roncador, Quitasueño, and Providencia and other islands now under Colombian control.

on the Americas mainland was founded. Vasco Nuñez de Balboa

and Martin de Enciso agreed on the site near the mouth of the Tarena River on the Atlantic. Balboa maneuvered and was appointed Mayor on the first official cabildo abierto (municipal council) held on the mainland. On August 28, 1513, the Santa María de La Antigua del Darién mission was erected with Fray Juan de Quevedo as the first Catholic Bishop in the continental Americas.

, which he named the South Sea.

The 'fantastic descriptions' of the isthmus by Balboa, as well as those of Columbus and other explorers, impressed Ferdinand II of Aragon

and Castilla, who gave the territory the name of Castilla Aurifica (or Castilla del Oro, Golden Castille). He assigned Pedro Arias Dávila (Pedrarias Davila) as Royal Governor. Pedrarias arrived in June 1514 with a 22 vessel, 1,500 men armada. Dávila was a veteran soldier who had served in the wars against the Moors at Granada

and in North Africa.

), the first European settlement on the shores of the Pacific.

Governor Pedrarias sent Gil González Dávila to explore northward, and in 1524 Francisco Hernández de Córdoba

to settle that region (present day Nicaragua

). Pedrarias was a party to the agreement authorizing the expedition by conquistador

s Francisco Pizarro

and Diego de Almagro

that brought the European discovery and conquest of the Inca Empire

(present day Peru

).

In 1526, Pedrarias was superseded as Governor of Panama by Pedro de los Ríos, and retired to León in Nicaragua, where he was named its new governor on July 1, 1527. Here he died on March 6, 1531, at the age of 91.

Panama was part of the Spanish Empire

for over 300 years (1513-1821) and her fortunes fluctuated with the geopolitical importance of the isthmus to the Spanish crown. During the 16th and 17th centuries, at the height of the Empire, no other region would prove of more strategic and economic importance.

Governor Pedrarias began building intercontinental and trans-isthmian portage routes, such as the "Camino Real" and "Camino de Cruces", linking Panama City and the Pacific with Nombre de Dios (and later with “Portobelo”) and the Atlantic, making possible the establishment of a trans-atlantic system of Treasure Fleets and trade. It is estimated that of all the gold entering Spain from the New World between 1531 and 1660, 60% had arrived at its destiny via the 'Treasure Fleet and Fairs' system from Nombre de Dios/Portobelo.

Explorations and conquest expeditions launched from Panama claimed new lands and riches from Central and South America. Explorations seeking a natural waterway between the Atlantic and the South Sea with the hope of reaching the Molucas (Spice Islands—Maluku Islands

) and Cathay

(China) were also pursued.

In 1538 the Audiencia Real de Panama, Royal Audiencia of Panama

In 1538 the Audiencia Real de Panama, Royal Audiencia of Panama

, was established, initially with jurisdiction from Nicaragua to Cape Horn. A Audiencia Real (royal audiency) was a judicial district that functioned as an appellate court

. Each audiencia had oidores (a hearer, a judge).

Strategically located on the Pacific coast, Panama City was relatively free of the permanent menace of pirates that roamed the Atlantic coast for over one and a half century, until it was destroyed by a devastating fire, when the pirate Henry Morgan sacked it on January 28, 1671. It was rebuilt and formally established on January 21, 1673, in a peninsula located 8 km from the original settlement. The place where the previously devastated city was located is still in ruins, and has become a tourist attraction known as "Panama Viejo".

Panama was the location in 1698 of the Darien scheme

which set up the ill-fated Scottish

"New Caledonia" colony in the region west of the Gulf of Darien

in the Bay of Caledonia.. The Darien scheme failed for a number of reasons, and the ensuing Scottish debt contributed to the 1707 Acts of Union

that joined the previously separate state

s of the Kingdom of England

and the Kingdom of Scotland

- into the Kingdom of Great Britain

".

When Panama was colonized, the indigenous peoples who survived many diseases, massacres and enslavement of the conquest ultimately fled into the forest and nearby islands. Indian slaves were replaced by imported enslaved Africans.

The prosperity enjoyed during the first two centuries (1540–1740) while contributing to colonial growth; the placing of extensive regional judicial authority (Real Audiencia) as part of its jurisdiction; and the pivotal role it played at the height of the Spanish Empire -the first modern global empire- helped define a distinctive sense of autonomy and of regional or national identity within Panama well before the rest of the colonies.

In 1744 Bishop Francisco Javier de Luna Victoria y Castro established the College of San Ignacio de Loyola and on June 3, 1749 founded La Real y Pontificia Universidad de San Javier. By this time, however, Panama’s importance and influence had become insignificant as Spain’s power dwindled in Europe and advances in navigation technique increasingly permitted to round Cape Horn in order to reach the Pacific. While the Panama route was short it was also labor intensive and expensive because of the loading and unloading and laden-down trek required to get from the one coast to the other. The Panama route was also vulnerable to attack from pirates (mostly Dutch and English) and from 'new world' Africans called cimarrons who had freed themselves from enslavement and lived in communes or palenques around the Camino Real in Panama's Interior, and on some of the islands off Panama's Pacific coast. During the last half of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th migrations to the countryside decreased Panama City’s population and the isthmus' economy shifted from the tertiary to the primary sector.

In 1713, the Viceroyalty of New Granada

(northern South America) was created in response to other Europeans trying to take Spanish territory in the Caribbean

region. The Isthmus of Panama was placed under its jurisdiction. But the remoteness of New Granada's capitol Santa Fe de Bogotá

proved a greater obstacle than the Spanish crown anticipated as the authority of the new Viceroyalty was contested by the seniority, closer proximity, previous ties to the Viceroyalty of Peru

in Lima

and even Panama's own initiative. This uneasy relationship between Panama and Bogotá would persist for a century.

, who's ambitious project of a Gran Colombia

(1819–1830) was beginning to take shape. Then, timing the action with the rest of the Central American isthmus, Panama declared its independence in 1821 and joined the southern federation. As the isthmus' central interoceanic traffic zone, as well as the City of Panama had been of great historical importance to the Spanish Empire

and subject of direct influence, so, the differences in social and economic status between the more liberal region of Azuero

, and the much more royalist and conservative area of Veraguas displayed contrasting loyalties. When the Grito de la Villa de Los Santos independence motion occurred, Veraguas firmly opposed it.

system in Azuero, set forth by the Spanish Crown, in 1558 due to repeated protests by locals against the mistreatment of the native population. In its stead, a system of medium and smaller-sized landownership was promoted, thus taking away the power from the large landowners and into the hands of medium and small sized proprietors.

The end of the encomienda system in Azuero, however, sparked the conquest of Veraguas in that same year. Under the leadership of Francisco Vázquez

, the region of Veraguas passed into Castillan rule in 1558. In the newly conquered region, the old system of encomienda was imposed.

The tension between the two regions finally peaked when the first printing press arrived in Panama in 1820. Under the guidance of José María Goitía, the printing press was utilized to create a newspaper called La Miscelánea. Panamanians Mariano Arosemena, Manuel María Ayala, and Juan José Calvo, as well as Colombian Juan José Argote, formed the writing team of the new newspaper, whose stories would circulate throughout every town in the isthmus.

The newspaper was put to use in the service of the cause of independence. It circulated stories expounding the virtues of liberty, independence, and the teachings of the French Revolution, as well as stories of the great battles of Bolívar, the emancipation of the United States from their British masters, and the greatness of men such as Santander, Jose Martí, and other such messengers of freedom.

Due to the narrow area of circulation, those in the capital were able to transmit these intoxicating ideals to other such separatits, such as those in Azuero. In Veraguas, however, there remained a strict sense of submission to the Spanish Crown.

The Grito was an event that shook the isthmus to the core. It was a sign, on the part of the residents of Azuero, of their antagonism towards the independence movement in the capital, who in turn regarded the Azueran movement with contempt, since they (the capital movement) believed that their counterparts were fighting their right to rule, once the peninsulares (peninsular-born) were long gone.

It was, as well, an incredibly brave move on the part of Azuero, which lived in fear of Colonel José de Fábrega, and with good reason: the Colonel was a staunch loyalist, and had the entirety of the isthmus' military supplies in his hands. They feared quick retaliation and swift retribution against the separatists.

What they had not counted on, however, was the influence of the separatists in the capital. Ever since October 1821, when the former Governor General, Juan de la Cruz Mourgeón

, left the isthmus on a campaign in Quito and left the Veraguan colonel in charge, the separatists had been slowly converting Fábrega to the separatist side. As such, by November 10, Fábrega was now a supporter of the independence movement. Soon after the separatist declaration of Los Santos, Fábrega convened every organization in the capital with separatist interests and formally declared the city's support for independence. No military repercussions occurred due to the skillful bribing of royalist troops.

Having sealed the fate of the Spanish Crown's rule in Panama with his defection, Jóse de Fábrega now collaborated with the separatists in the capital to bring about a national assembly, where the fate of the country would be decided. Every region in Panama attended the assembly, including the former loyalist region of Veraguas, which was eventually convinced to join the revolution, out of the sheer fact that nothing more could be done for the royalist presence in Panama. Thus, on November 28, 1821, the national assembly was convened and it was officially declared (through Fábrega, who was invested with the title of Head of State of Panama) that the isthmus of Panama had severed its ties with the Spanish Empire and its decision to join New Granada and Venezuela in Bolivar's recently founded Republic of Colombia.

Posterior to the act, Fábrega wrote to Bolívar of the event, saying:

Bólivar, in turn, replied,

project. Besides the geographical argument, there was the fact that Simon Bolivar’s actions had been the decisive military factor in the independence of Venezuela, New Granada and Ecuador, while his role in Panama’s independence was none. Thus, while Bolivar knew that the nation of Panama was linked historically and culturally to South America, he was also conscious of the fact that the region was part of the Central American geography. This view is clearly seen in some of his famous documents and quotes such as his Carta de Jamaica (1815):

Nevertheless in 1821, convinced that under Bolivar's leadership the nation's destiny would move in the most progressive direction, the Isthmus joined Venezuela, New Granada (present day Colombia) and latter Ecuador, in 1822. The Republic of Colombia (1819–1830) or ‘Gran Colombia’ as it began to be called only after 1886, more or less corresponded in territory to the old colonial administrative district called the Viceroyalty of New Granada

(1717–1819). While Panama had also been included in the Viceroyalty during the colonial period, the Isthmus' economic and political ties had been much closer, for all practical purposes, to the Viceroyalty of Peru (1542–1821).

In September 1830, under the guidance of General José Domingo Espinar, the local military commander who rebelled against the nation's central government in response to his being transferred to another command, Panama separated from the Republic of Colombia and requested that general Simón Bolívar

take direct command of the Isthmus Department. It made this a condition to its reunification with the rest of the country. Bolívar rejected Espinar's actions, and though he did not assume control of the isthmus as he desired, he called for Panama to rejoin the central state. Because of the overall political tension, Republic of Colombia's final days were approaching. Bolívar's vision for territorial unity disintegrated finally when General Juan Eligio Alzuru undertook a military coup against Espinar's authority. By early 1831, with order restored, Panama reincorporated itself to what was left of the republic -forming a territory now slightly larger than present day Panama and Colombia combined- which by then had adopted the name of Republic of New Granada

. The alliance of the two nations would last seventy years and prove precarious.

, resulting in the defeat and execution of Alzuru in August, and the reestablishment of ties with New Granada.

In November 1840, during a civil war that had begun as a religious conflict, the isthmus under the leadership of -now General- Tomás Herrera, who assumed the title of Superior Civil Chief, declared its independence as did multiple other local authorities. The State of Panama took in March 1841 the name of 'Estado Libre del Istmo', or the Free State of the Isthmus. The new state established external political and economic ties and by March 1841, had drawn up a constitution which included the possibility for Panama to rejoin New Granada, but only as a federal district. Herrera's style was first changed to Superior Chief of State in March 1841 and in June 1841 to President. By the time the civil conflict ended and the government of New Granada and the government of the Isthmus had negotiated the Isthmus's reincorporation to the union, Panama's First Republic had been free for 13 months. Reunification happened on December 31, 1841.

In the end, the union between Panama and the Republic of New Granada (under its various names United States of Colombia 1863-1886 and the Republic of Colombia since 1886) was made possible by the active participation of U.S.A. under the 1846 Bidlack Mallarino treaty until 1903.

In the 1840s, two decades after the Monroe Doctrine

declared U.S. intentions to be the dominant anti-European imperial power in the Western Hemisphere

, North American and French interests became excited about the prospects of constructing railroads and/or canals through Central America to quicken trans-oceanic travel. At the same time it was clear that New Granada’s control over the isthmus was turning increasingly untenable. In 1846, the United States and New Granada signed the Bidlack Mallarino Treaty, granting the U.S. rights to build railroads

through Panama, and -most significantly- the power to militarily intervene against revolt to guarantee New Granadine control of Panama. The world's first transcontinental railroad

, the Panama Railway

, was completed in 1855 across the Isthmus from Aspinwall/Colón

to Panama City

. From 1850 until 1903, the United States used troops to suppress separatist uprisings and quell social disturbances on many occasions, creating a long-term animosity among the Panamanian people against the US military and resentment against Bogotá. The Bidlack-Mallarino Treaty had ushered a new era of U.S. intervention and conflicts which would linger on into the new millennium. The first of many such conflicts was known as the Watermelon War

of 1856, where U.S. soldiers mistreated locals causing large-scale race riots that U.S. Marines eventually put down.

Under a federalist constitution that was later brought up in 1858 (and another one in 1863), Panama and other constituent states gained almost complete autonomy on many levels of their administration, which led to an often anarchic national state of affairs that lasted roughly until Colombia's return to centralism in 1886 with the establishment of a new Republic of Colombia.

As was often the case in the new world after independence, the local administrative and political structures were controlled by the remnants of the colonial aristocracy. In the case of Panama, this elite was constituted by a group of under ten extended families. Though Panama has made enormous advances in social mobility and racial integration

, it is still true that much of Panama's economic and social life is controlled by a small number of families. The derogatory term rabiblanco ("white tail"), of uncertain origin, has been used for generations to refer to the usually Caucasian members of the elite families.

In 1852 the isthmus would adopt trial by jury in criminal cases and—30 years after abolition—would finally declare and enforce an end to slavery. In 1855, the first Transcontinental railway of the New World

, the Panama Railway

, was built across the isthmus from Colón

to Panama City

to transport fortune hunters who wanted quick passage to the gold fields of California. The existence of the railroad made speculation about a Panamanian canal feasible.

, who had successfully built the Suez Canal

, attempted to construct a sea-level canal in the same general area as the present Panama Canal

. The company faced insurmountable health problems such as yellow fever

and malaria

as well as engineering challenges caused by frequent landslides, slippage of equipment and mud. In the end the company failed in a spectacular collapse which caused the downfall and incarceration of many of its financial backers in France. A new company was formed in 1894 to recuperate some of the losses of the original canal company.

U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

convinced U.S. Congress to take on the abandoned works in 1902, while Colombia was in the midst of the Thousand Days War

. During the war there were at least three attempts by Panamanian Liberals to seize control of Panama and potentially achieve full autonomy, including one led by Liberal

guerrillas

like Belisario Porras and Victoriano Lorenzo

, each of whom was suppressed by a collaboration of Conservative

Colombian and U.S. forces under the Mallarino-Bidlack Treaty

. By the middle of 1903, the Colombian government in Bogotá

had balked at the prospect of a U.S. controlled canal under the terms that the Roosevelt administration was offering. The U.S. was unwilling to alter its terms and quickly changed tactics. According to the terms of the treaty, the U.S. was to pay the stockholders of the French company that had tried to build the canal across Panama the sum of $40,000,000.

The Colombian Senate's rejection of the treaty confronted these French investors with the prospect of losing everything. At this point, the French company's chief lobbyist (and a major stockholder), Philippe Bunau-Varilla went into action. Justly confident that the Roosevelt administration would support his initiative, from a suite in the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York, Bunau-Varilla arranged for the Panama City fire department to stage a revolution against Colombia. The USS Nashville

was dispatched to local waters around the city of Colón, where a force of 474 Colombian soldiers had landed and was preparing to cross the isthmus and crush the rebellion. The USS Nashville

's Commander John Hubbard sent a small party ashore and, with the support of the American superintendent of the Panama Railroad, kept the Colombians from taking the train to Panama City. On November 3, 1903, after 57 years of policing Bogotá's interests, the United States had sided with Panama.

Less than three weeks later, on November 18, 1903, the Hay-Bunau Varilla Treaty

was signed between Frenchman Philippe Bunau-Varilla, who had promptly been appointed Panamanian ambassador to the United States, representing Panamanian interests, and the United States Secretary of State John Hay. The treaty allowed for the construction of a canal

and U.S. sovereignty over a strip of land 10 miles (16.1 km) wide and 50 miles (80.5 km) long, (16 kilometers by 80 kilometers) on either side of the Panama Canal Zone

. In that zone, the U.S. would build a canal, then administer, fortify, and defend it "in perpetuity."

Roosevelt’s explanation of the U.S.’ role in the region was made abundantly clear throughout the many speeches and addresses he gave from 1902 on. First he invoked the Bidlack-Mallarino Treaty; second, he made it clear that Colombia had rejected his government’s offers for a deal; and finally, he demonstrated that Colombia had never been capable of preventing Panama from regaining its sovereignty. On his December 7, 1903 Third Annual Message to the Senate and House of Representatives he enumerated an extensive list of interventions the U.S. armed forces had made in Panama since 1850 explaining:

And he added:

It is evident that treaties like the Bidlack-Mallarino Treaty were not considered unconstitutional, or illegal, at the time given the fact that they included interference of the U.S. government in internal matters of a sovereign country. It is also evident that Roosevelt speeches made clear that the United States decided to unilaterally break with the Bidlack-Mallarino treaty and, instead of solving the internal Panamanian problem as the treaty forced them to do, helped with the separation of Panama from Colombia. Thus enforcing that part of the treaty which was of interest to the United States, namely, "It granted the U.S. significant transit rights over the Panamanian isthmus"

It is a common mistake to call the 1903 events ‘Panama’s independence from Colombia’. Panamanians do not consider themselves former Colombians. They celebrate their independence from Spain (like the rest of Hispanic America)on November 28, 1821; and November 3, 1903, the separation from Colombia.

in Colombia

signed and presented to its Congress a treaty that would officially recognize the loss of its former province, but the matter was dropped due to popular and legislative opposition, without any ratification being achieved. Different negotiations continued intermittently until a new treaty was signed on December 21, 1921 which finally and formally accepted the independence of Panama.

While Roosevelt’s ‘walk softly and carry a big stick’ as well as the Canal Company’s apartheid administrative policies, early on, have been the subject of much criticism, the fact is that, beyond the financial injection to the country’s economy and workforce, the changes brought about by the canal venture were largely positive for Panama. Well aware of the need to sanitize the area before and during the construction, engineers developed an infrastructure that guaranteed the treatment of potable water, sewage, and garbage that encompassed both the Canal Zone as well as the cities of Panama and Colon. High standards employed in construction techniques, transportation systems and landscaping maintenance operations for the Canal Zone's urban development employed during the first half of the 20th century, had no parallel in tropical regions in the hemisphere. The work of Dr.William Gorgas deploying the techniques pioneered by Cuban physician Carlos Finley made it possible to rid the area of yellow fever between 1902 and 1905. Gorgas' work in the sanitation of the Canal Zone and the cities of Panama and Colon eventually made him a sought after authority internationally.

The entire Panama Canal, the area supporting the Canal, and remaining US military bases were turned over to Panama on December 31, 1999.

dominated by a commercially-oriented oligarchy

. During the 1950s, the Panamanian military began to challenge the oligarchy's political hegemony. The January 9, 1964 Martyrs' Day riots escalated tensions between the country and the U.S. government over its long-term occupation of the Canal Zone. Twenty rioters were killed, and 500 other Panamanians were wounded.

In October 1968, Dr. Arnulfo Arias Madrid was elected president for the third time. Twice ousted by the Panamanian military, he was again ousted (for the third time) as president by the National Guard after only 10 days in office. A military junta government was established, and the commander of the National Guard, Brig. Gen. Omar Torrijos

, emerged as the principal power in Panamanian political life. Torrijos' regime was harsh and corrupt, and had to confront the mistrust of the people and guerrillas backing the populist Arnulfo Arias. However, he was a charismatic leader whose Socialist domestic programs and nationalist foreign policy appealed to the rural and urban constituencies who were largely ignored by the oligarchy.

On September 7, 1977, the Torrijos-Carter Treaties

were signed by the Panamanian head of state and U.S. President Jimmy Carter

for the complete transfer of the Canal and the fourteen US army bases from the US to Panama by 1999. These treaties also granted the U.S. a perpetual right of military intervention. Certain portions of the Zone and increasing responsibility over the Canal were turned over in the intervening years.

Torrijos died in a mysterious plane crash on August 1, 1981. The circumstances of his death generated charges and speculation that he was the victim of an assassination plot. Torrijos' death altered the tone but not the direction of Panama's political evolution. Despite 1983 constitutional amendments, which appeared to proscribe a political role for the military, the Panama Defense Forces (PDF), as they were then known, continued to dominate Panamanian political life behind a facade of civilian government. By this time, Gen. Manuel Noriega

Torrijos died in a mysterious plane crash on August 1, 1981. The circumstances of his death generated charges and speculation that he was the victim of an assassination plot. Torrijos' death altered the tone but not the direction of Panama's political evolution. Despite 1983 constitutional amendments, which appeared to proscribe a political role for the military, the Panama Defense Forces (PDF), as they were then known, continued to dominate Panamanian political life behind a facade of civilian government. By this time, Gen. Manuel Noriega

was firmly in control of both the PDF and the civilian government, and had created the Dignity Battalions

to help suppress opposition.

Despite undercover collaboration with Ronald Reagan

on his Contra war in Nicaragua

(including the infamous Iran-Contra Affair

), which had planes flying arms as well as drugs, relations between the United States and the Panama regime worsened in the 1980s.

The United States froze economic and military assistance to Panama in the summer of 1987 in response to the domestic political crisis and an attack on the U.S. embassy. General Noriega's February 1988 indictment in U.S. courts on drug-trafficking charges sharpened tensions. In April 1988, President Reagan invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act

, freezing Panamanian Government assets in U.S. banks, withholding fees for using the canal, and prohibiting payments by American agencies, firms, and individuals to the Noriega regime. The country went into turmoil. When national elections were held in May 1989, the elections were marred by accusations of fraud from both sides. An American, Kurt Muse, was apprehended by the Panamanian authorities, after he had set up a sophisticated radio and computer installation, designed to jam Panamanian radio and broadcast phony election returns. However, the elections proceeded as planned, and Panamanians voted for the anti-Noriega candidates by a margin of over three-to-one. The Noriega regime promptly annulled the election and embarked on a new round of repression. By the fall of 1989, the regime was barely clinging to power.

When Guillermo Endara

won the Presidential elections held in May 1989, the Noriega regime annulled the election, citing massive US interference. Foreign election observers, including the Catholic Church and Jimmy Carter

certified the electoral victory of Endara despite widespread attempts at fraud by the regime. At the behest of the United States, the Organization of American States

convened a meeting of foreign ministers but was unable to obtain Noriega's departure. The U.S. began sending thousands of troops to bases in the canal zone. Panamanian authorities alleged that U.S. troops left their bases and illegally stopped and searched vehicles in Panama. During this time, an American Marine got lost in the former French quarter of Panama City, ran a roadblock, and was killed by Panamanian Police (who were then a part of the Panamanian Military). On December 20, 1989 the United States troops commenced an invasion of Panama

. Their primary objectives were achieved quickly, and the combatants withdrawal began on December 27. The US was obligated to hand control of the Panama Canal her to Panama on January 1 due to a treaty signed decades before. Endara was sworn in as President at a U.S. military base on the day of the invasion. General Manuel Noriega

is now serving a 40-year sentence for drug trafficking. Estimates as to the loss of life on the Panamanian side vary between 500 and 7000. There are also unproven claims that U.S. troops buried many corpses in mass graves (which have never been found) or simply threw them into the sea. For different perspectives, see references below. Much of the Chorillo neighborhood was destroyed by fire shortly after the start of the invasion.

Following the invasion, President George H. W. Bush announced a billion dollars in aid to Panama. Critics argue that about half the aid was a gift from the American taxpayer to American businesses, as $400 million consisted of incentives for U.S. business to export products to Panama, $150 million was to pay off bank loans and $65 million went to private sector loans and guarantees to U.S. investors.

. Subsequently, on December 27, 1989, Panama's Electoral Tribunal invalidated the Noriega regime's annulment of the May 1989 election and confirmed the victory of opposition candidates under the leadership of President Guillermo Endara and Vice Presidents Guillermo Ford

and Ricardo Arias Calderón.

President Endara took office as the head of a four-party minority government, pledging to foster Panama's economic recovery, transform the Panamanian military into a police force under civilian control

, and strengthen democratic institutions. During its 5-year term, the Endara government struggled to meet the public's high expectations. Its new police force proved to be a major improvement in outlook and behavior over its thuggish predecessor but was not fully able to deter crime. In 1992 he would have received 2.4 percent of the vote if there had been an election. Ernesto Pérez Balladares

was sworn in as President on September 1, 1994, after an internationally monitored election campaign.

Pérez Balladares ran as the candidate for a three-party coalition dominated by the Democratic Revolutionary Party

(PRD), the erstwhile political arm of the military dictatorship during the Torrijos and Norieiga years. A long-time member of the PRD, Pérez Balladares worked skillfully during the campaign to rehabilitate the PRD's image, emphasizing the party's populist Torrijos roots rather than its association with Noriega. He won the election with only 33% of the vote when the major non-PRD forces, unable to agree on a joint candidate, splintered into competing factions. His administration carried out economic reforms and often worked closely with the U.S. on implementation of the Canal treaties.

On May 2, 1999, Mireya Moscoso

, the widow of former President Arnulfo Arias Madrid, defeated PRD candidate Martín Torrijos

, son of the late dictator. The elections were considered free and fair. Moscoso took office on September 1, 1999.

During her administration, Moscoso attempted to strengthen social programs, especially for child and youth development, protection, and general welfare. Education programs have also been highlighted. More recently, Moscoso focused on bilateral and multilateral free trade initiatives with the hemisphere. Moscoso's administration successfully handled the Panama Canal transfer and has been effective in the administration of the Canal.

Panama's official counternarcotics cooperation has historically been excellent (in fact, officials of the DEA

praised the role played by Manuel Noriega

prior to his falling-out with the U.S. over his own drug dealing ) The Panamanian Government has expanded money-laundering legislation and concluded with the U.S. a Counternarcotics Maritime Agreement and a Stolen Vehicles Agreement. In the economic investment arena, the Panamanian Government has been very successful in the enforcement of intellectual property rights and has concluded with the U.S. a very important Bilateral Investment Treaty Amendment and an agreement with the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC

). The Moscoso administration was very supportive of the United States in combating international terrorism.

In 2004, Martín Torrijos again ran for president but this time won handily.

Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country of Panama and the Panama Canal...

region's long history that occurred in southern Central America

Central America

Central America is the central geographic region of the Americas. It is the southernmost, isthmian portion of the North American continent, which connects with South America on the southeast. When considered part of the unified continental model, it is considered a subcontinent...

, from Pre-Columbian

Pre-Columbian

The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic period to European colonization during...

cultures, during the Spanish colonial era, through independence and the current country of Panama

Panama

Panama , officially the Republic of Panama , is the southernmost country of Central America. Situated on the isthmus connecting North and South America, it is bordered by Costa Rica to the northwest, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The...

.

Indigenous period

The earliest artifacts discovered of indigenous peoplesIndigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

in Panama have included Paleo-Indians projectile point

Projectile point

In archaeological terms, a projectile point is an object that was hafted to a projectile, such as a spear, dart, or arrow, or perhaps used as a knife....

s. Later central Panama was home to some of the first pottery

Pottery

Pottery is the material from which the potteryware is made, of which major types include earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. The place where such wares are made is also called a pottery . Pottery also refers to the art or craft of the potter or the manufacture of pottery...

-making in the Americas

Americas

The Americas, or America , are lands in the Western hemisphere, also known as the New World. In English, the plural form the Americas is often used to refer to the landmasses of North America and South America with their associated islands and regions, while the singular form America is primarily...

, such as the Monagrillo

Monagrillo

Monagrillo is an archaeological site in south-central Panama with ceramics that have been shown by radiocarbon dating to have an occupation range of about 2500 BCE—1200 BCE. The site is important because it provides the earliest example of ceramics in Central America along with one of the earliest...

cultures dating to about 2500-1700 BCE. These evolved into significant populations that are best known through the spectacular burials (dating to c. 500-900 CE) at the Monagrillo archaeological site

Archaeological site

An archaeological site is a place in which evidence of past activity is preserved , and which has been, or may be, investigated using the discipline of archaeology and represents a part of the archaeological record.Beyond this, the definition and geographical extent of a 'site' can vary widely,...

, and the beautiful polychrome pottery of the Gran Coclé

Gran Coclé

Gran Coclé is an archaeological culture area of the so-called Intermediate Area in pre-Columbian Central America. The area largely coincides with the modern-day Panamanian province of Coclé, and consisted of a number of identifiable native cultures. Archaeologists have loosely designated these...

style. The monumental monolith

Monolith

A monolith is a geological feature such as a mountain, consisting of a single massive stone or rock, or a single piece of rock placed as, or within, a monument...

ic sculptures at the Barriles

Barriles

Barriles , is one of the most famous archaeological sites in Panama. It is located in the highlands of the Chiriquí Province of Western Panama at 1200 meters above sea level. It is several kilometers west of the modern town of Volcán...

(Chiriqui) site are other important evidence of the ancient isthmian cultures.

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Panama was widely settled by Chibchan, Chocoan, and Cueva

Cueva people

The Cueva were an indigenous people that lived in the Darién region of eastern Panamá. They were completely exterminated between 1510 and 1535 due to the effects of Spanish colonization....

peoples, among whom the largest group were the Cueva (whose specific language affiliation is poorly documented). There is no accurate knowledge of size of the Pre-Columbian indigenous population of the isthmus at the time of the European conquest. Estimates range as high as two million people, but more recent studies place that number closer to 200,000. Archeological finds as well as testimonials by early European explorers describe diverse native isthmian groups exhibiting cultural variety and already experienced in using regional trade route

Trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a single trade route contains long distance arteries which may further be connected to several smaller networks of commercial...

s. The indigenous people of Panama lived by hunting, gathering edible plants & fruits, growing corn, cacao, and root crops. They lived in small huts made of palm leaves over a rounded branch structure, with hammocks hung between the interior walls for sleeping.

Spanish Colonial period

In 1501, Rodrigo de BastidasRodrigo de Bastidas

Rodrigo de Bastidas was a Spanish conquistador and explorer who mapped the northern coast of South America and founded the city of Santa Marta.-Early life:...

was the first European to explore the Isthmus of Panama

Isthmus of Panama

The Isthmus of Panama, also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country of Panama and the Panama Canal...

sailing along the eastern coast. A year later Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

, sailing south and eastward from upper Central America, explored Bocas del Toro

Bocas del Toro Province

Bocas del Toro is a province of Panama. Its extension is 4,643.9 square kilometers comprising the mainland and nine main islands. The province consists of the Bocas del Toro Archipelago, Bahía Almirante , Laguna de Chiriquí , and adjacent mainland. The capital is the city of Bocas del Toro on Isla...

, Veragua

Veragua

Veragua or Veraguas was the name of five territorial entities in Central America, beginning in the sixteenth century during the Spanish colonial period...

, the Chagres River

Chagres River

The Chagres River is a river in central Panama. The central part of the river is dammed by the Gatun Dam and forms Gatun Lake, an artificial lake that constitutes part of the Panama Canal. Upstream lies the Madden Dam, creating the Alajuala Lake that is also part of the Canal water system...

and Porto Belo

Porto Belo

Porto Belo is a town and municipality in the state of Santa Catarina in the South region of Brazil.-References:...

(Beautiful Port) which he named. Soon Spanish expeditions would converge upon Tierra Firma (also Tierra Firme, Spanish from the Latin terra firma, "dry land" or "mainland") which served in Spanish colonial times as the name for the Isthmus of Panama

In 1509, authority was granted to Alonso de Ojeda and Diego de Nicuesa to colonize the territories between the west side of the Gulf of Uraba to Cabo Gracias a Dios in present-day Honduras. The idea was to create an early unitary administrative organization similar to what later became Nueva España (now Mexico). Tierra Firme later received control over other territories: the Isla de Santiago (now Jamaica) the Cayman Islands; Roncador, Quitasueño, and Providencia and other islands now under Colombian control.

Santa Maria la Antigua del Darien

In September 1510, the first permanent European settlement, Santa María la Antigua del DariénSanta María la Antigua del Darién

Santa María la Antigua del Darién was a Spanish colonial town founded in 1510 by Vasco Núñez de Balboa, located in present-day Colombia approximately 40 miles south of Acandí...

on the Americas mainland was founded. Vasco Nuñez de Balboa

Vasco Núñez de Balboa

Vasco Núñez de Balboa was a Spanish explorer, governor, and conquistador. He is best known for having crossed the Isthmus of Panama to the Pacific Ocean in 1513, becoming the first European to lead an expedition to have seen or reached the Pacific from the New World.He traveled to the New World in...

and Martin de Enciso agreed on the site near the mouth of the Tarena River on the Atlantic. Balboa maneuvered and was appointed Mayor on the first official cabildo abierto (municipal council) held on the mainland. On August 28, 1513, the Santa María de La Antigua del Darién mission was erected with Fray Juan de Quevedo as the first Catholic Bishop in the continental Americas.

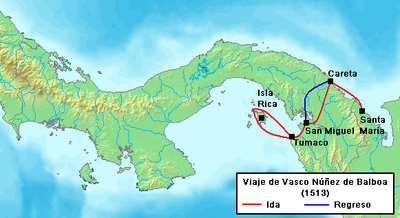

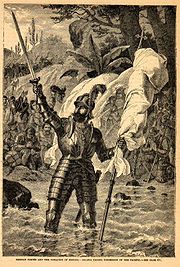

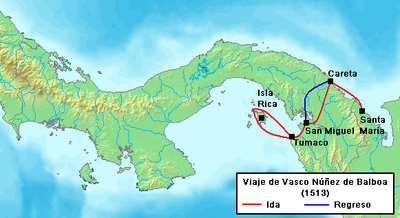

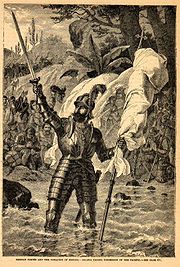

Balboa expedition

On September 25, 1513 the Balboa expedition verified what the indigenous people had spoken of, that the Panama isthmus had another coast to the southwest along another ocean. Balboa was the first known European to see the Pacific OceanPacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

, which he named the South Sea.

The 'fantastic descriptions' of the isthmus by Balboa, as well as those of Columbus and other explorers, impressed Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand the Catholic was King of Aragon , Sicily , Naples , Valencia, Sardinia, and Navarre, Count of Barcelona, jure uxoris King of Castile and then regent of that country also from 1508 to his death, in the name of...

and Castilla, who gave the territory the name of Castilla Aurifica (or Castilla del Oro, Golden Castille). He assigned Pedro Arias Dávila (Pedrarias Davila) as Royal Governor. Pedrarias arrived in June 1514 with a 22 vessel, 1,500 men armada. Dávila was a veteran soldier who had served in the wars against the Moors at Granada

Granada

Granada is a city and the capital of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence of three rivers, the Beiro, the Darro and the Genil. It sits at an elevation of 738 metres above sea...

and in North Africa.

Colonization

On August 15, 1519, Pedrarias, having abandoned Santa María la Antigua del Darién, moved the capital of Castilla del Oro with all its organizational institutions to the Pacific Ocean's coast and founded Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Panamá (present day Panama CityPanama City

Panama is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Panama. It has a population of 880,691, with a total metro population of 1,272,672, and it is located at the Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal, in the province of the same name. The city is the political and administrative center of the...

), the first European settlement on the shores of the Pacific.

Governor Pedrarias sent Gil González Dávila to explore northward, and in 1524 Francisco Hernández de Córdoba

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba (founder of Nicaragua)

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba is usually reputed as the founder of Nicaragua, and in fact he founded two important Nicaraguan cities, Granada and León. The currency of Nicaragua is named the córdoba in his memory....

to settle that region (present day Nicaragua

Nicaragua

Nicaragua is the largest country in the Central American American isthmus, bordered by Honduras to the north and Costa Rica to the south. The country is situated between 11 and 14 degrees north of the Equator in the Northern Hemisphere, which places it entirely within the tropics. The Pacific Ocean...

). Pedrarias was a party to the agreement authorizing the expedition by conquistador

Conquistador

Conquistadors were Spanish soldiers, explorers, and adventurers who brought much of the Americas under the control of Spain in the 15th to 16th centuries, following Europe's discovery of the New World by Christopher Columbus in 1492...

s Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess was a Spanish conquistador, conqueror of the Incan Empire, and founder of Lima, the modern-day capital of the Republic of Peru.-Early life:...

and Diego de Almagro

Diego de Almagro

Diego de Almagro, , also known as El Adelantado and El Viejo , was a Spanish conquistador and a companion and later rival of Francisco Pizarro. He participated in the Spanish conquest of Peru and is credited as the first European discoverer of Chile.Almagro lost his left eye battling with coastal...

that brought the European discovery and conquest of the Inca Empire

Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire was one of the most important campaigns in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. This historic process of military conquest was made by Spanish conquistadores and their native allies....

(present day Peru

Peru

Peru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

).

In 1526, Pedrarias was superseded as Governor of Panama by Pedro de los Ríos, and retired to León in Nicaragua, where he was named its new governor on July 1, 1527. Here he died on March 6, 1531, at the age of 91.

Panama was part of the Spanish Empire

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

for over 300 years (1513-1821) and her fortunes fluctuated with the geopolitical importance of the isthmus to the Spanish crown. During the 16th and 17th centuries, at the height of the Empire, no other region would prove of more strategic and economic importance.

Governor Pedrarias began building intercontinental and trans-isthmian portage routes, such as the "Camino Real" and "Camino de Cruces", linking Panama City and the Pacific with Nombre de Dios (and later with “Portobelo”) and the Atlantic, making possible the establishment of a trans-atlantic system of Treasure Fleets and trade. It is estimated that of all the gold entering Spain from the New World between 1531 and 1660, 60% had arrived at its destiny via the 'Treasure Fleet and Fairs' system from Nombre de Dios/Portobelo.

Explorations and conquest expeditions launched from Panama claimed new lands and riches from Central and South America. Explorations seeking a natural waterway between the Atlantic and the South Sea with the hope of reaching the Molucas (Spice Islands—Maluku Islands

Maluku Islands

The Maluku Islands are an archipelago that is part of Indonesia, and part of the larger Maritime Southeast Asia region. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone...

) and Cathay

Cathay

Cathay is the Anglicized version of "Catai" and an alternative name for China in English. It originates from the word Khitan, the name of a nomadic people who founded the Liao Dynasty which ruled much of Northern China from 907 to 1125, and who had a state of their own centered around today's...

(China) were also pursued.

Royal Audiencia of Panama

Royal Audiencia of Panama

The Royal Audiencia and Chancery of Panama in Tierra Firme was a governing body and superior court in the New World empire of Spain. The Audiencia of Panama was the third American audiencia after the ones of Santo Domingo and Mexico...

, was established, initially with jurisdiction from Nicaragua to Cape Horn. A Audiencia Real (royal audiency) was a judicial district that functioned as an appellate court

Appellate court

An appellate court, commonly called an appeals court or court of appeals or appeal court , is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal...

. Each audiencia had oidores (a hearer, a judge).

Strategically located on the Pacific coast, Panama City was relatively free of the permanent menace of pirates that roamed the Atlantic coast for over one and a half century, until it was destroyed by a devastating fire, when the pirate Henry Morgan sacked it on January 28, 1671. It was rebuilt and formally established on January 21, 1673, in a peninsula located 8 km from the original settlement. The place where the previously devastated city was located is still in ruins, and has become a tourist attraction known as "Panama Viejo".

Panama was the location in 1698 of the Darien scheme

Darién scheme

The Darién scheme was an unsuccessful attempt by the Kingdom of Scotland to become a world trading nation by establishing a colony called "New Caledonia" on the Isthmus of Panama in the late 1690s...

which set up the ill-fated Scottish

Scottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

"New Caledonia" colony in the region west of the Gulf of Darien

Gulf of Darién

The Gulf of Darién is the southernmost region of the Caribbean Sea, located north and east of the border between Panama and Colombia. Within the gulf is the Gulf of Urabá, a small lip of sea extending southward, between Caribana Point and Cape Tiburón, Colombia, on the southern shores of which is...

in the Bay of Caledonia.. The Darien scheme failed for a number of reasons, and the ensuing Scottish debt contributed to the 1707 Acts of Union

Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union were two Parliamentary Acts - the Union with Scotland Act passed in 1706 by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act passed in 1707 by the Parliament of Scotland - which put into effect the terms of the Treaty of Union that had been agreed on 22 July 1706,...

that joined the previously separate state

Sovereign state

A sovereign state, or simply, state, is a state with a defined territory on which it exercises internal and external sovereignty, a permanent population, a government, and the capacity to enter into relations with other sovereign states. It is also normally understood to be a state which is neither...

s of the Kingdom of England

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

and the Kingdom of Scotland

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland was a Sovereign state in North-West Europe that existed from 843 until 1707. It occupied the northern third of the island of Great Britain and shared a land border to the south with the Kingdom of England...

- into the Kingdom of Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

".

When Panama was colonized, the indigenous peoples who survived many diseases, massacres and enslavement of the conquest ultimately fled into the forest and nearby islands. Indian slaves were replaced by imported enslaved Africans.

The prosperity enjoyed during the first two centuries (1540–1740) while contributing to colonial growth; the placing of extensive regional judicial authority (Real Audiencia) as part of its jurisdiction; and the pivotal role it played at the height of the Spanish Empire -the first modern global empire- helped define a distinctive sense of autonomy and of regional or national identity within Panama well before the rest of the colonies.

In 1744 Bishop Francisco Javier de Luna Victoria y Castro established the College of San Ignacio de Loyola and on June 3, 1749 founded La Real y Pontificia Universidad de San Javier. By this time, however, Panama’s importance and influence had become insignificant as Spain’s power dwindled in Europe and advances in navigation technique increasingly permitted to round Cape Horn in order to reach the Pacific. While the Panama route was short it was also labor intensive and expensive because of the loading and unloading and laden-down trek required to get from the one coast to the other. The Panama route was also vulnerable to attack from pirates (mostly Dutch and English) and from 'new world' Africans called cimarrons who had freed themselves from enslavement and lived in communes or palenques around the Camino Real in Panama's Interior, and on some of the islands off Panama's Pacific coast. During the last half of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th migrations to the countryside decreased Panama City’s population and the isthmus' economy shifted from the tertiary to the primary sector.

In 1713, the Viceroyalty of New Granada

Viceroyalty of New Granada

The Viceroyalty of New Granada was the name given on 27 May 1717, to a Spanish colonial jurisdiction in northern South America, corresponding mainly to modern Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela. The territory corresponding to Panama was incorporated later in 1739...

(northern South America) was created in response to other Europeans trying to take Spanish territory in the Caribbean

Caribbean

The Caribbean is a crescent-shaped group of islands more than 2,000 miles long separating the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, to the west and south, from the Atlantic Ocean, to the east and north...

region. The Isthmus of Panama was placed under its jurisdiction. But the remoteness of New Granada's capitol Santa Fe de Bogotá

Bogotá

Bogotá, Distrito Capital , from 1991 to 2000 called Santa Fé de Bogotá, is the capital, and largest city, of Colombia. It is also designated by the national constitution as the capital of the department of Cundinamarca, even though the city of Bogotá now comprises an independent Capital district...

proved a greater obstacle than the Spanish crown anticipated as the authority of the new Viceroyalty was contested by the seniority, closer proximity, previous ties to the Viceroyalty of Peru

Viceroyalty of Peru

Created in 1542, the Viceroyalty of Peru was a Spanish colonial administrative district that originally contained most of Spanish-ruled South America, governed from the capital of Lima...

in Lima

Lima

Lima is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín rivers, in the central part of the country, on a desert coast overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Together with the seaport of Callao, it forms a contiguous urban area known as the Lima...

and even Panama's own initiative. This uneasy relationship between Panama and Bogotá would persist for a century.

Independence

In 1819 the liberation of New Granada was achieved, finally gaining its freedom from Spain. Panama and the other regions of former New Granada were therefore technically free. Panama weighed its options carefully as it considered union with Peru or with Central America in federations that were emerging in the region. Finally it was won over by Venezuela's Simon BolivarSimón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios Ponte y Yeiter, commonly known as Simón Bolívar was a Venezuelan military and political leader...

, who's ambitious project of a Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia

Gran Colombia is a name used today for the state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 1831. This short-lived republic included the territories of present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, northern Peru and northwest Brazil. The...

(1819–1830) was beginning to take shape. Then, timing the action with the rest of the Central American isthmus, Panama declared its independence in 1821 and joined the southern federation. As the isthmus' central interoceanic traffic zone, as well as the City of Panama had been of great historical importance to the Spanish Empire

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

and subject of direct influence, so, the differences in social and economic status between the more liberal region of Azuero

Azuero Peninsula

Azuero Peninsula is a large peninsula in southern Panama. It is surrounded by the Pacific Ocean in the south; the Pacific and Gulf of Montijo to the west, and by the Gulf of Panama in the east...

, and the much more royalist and conservative area of Veraguas displayed contrasting loyalties. When the Grito de la Villa de Los Santos independence motion occurred, Veraguas firmly opposed it.

Origin of the movement

The Panamanian movement for independence can be indirectly attributed to the abolishment of the encomiendaEncomienda

The encomienda was a system that was employed mainly by the Spanish crown during the colonization of the Americas to regulate Native American labor....

system in Azuero, set forth by the Spanish Crown, in 1558 due to repeated protests by locals against the mistreatment of the native population. In its stead, a system of medium and smaller-sized landownership was promoted, thus taking away the power from the large landowners and into the hands of medium and small sized proprietors.

The end of the encomienda system in Azuero, however, sparked the conquest of Veraguas in that same year. Under the leadership of Francisco Vázquez

Francisco Vázquez

Francisco H. Vázquez is a Mexican-American scholar and public intellectual. Vázquez is currently a tenured professor of the history of ideas and director of the Hutchins Institute for Public Policy Studies and Community Action at the nationally-known Hutchins School of Liberal Studies at Sonoma...

, the region of Veraguas passed into Castillan rule in 1558. In the newly conquered region, the old system of encomienda was imposed.

Arrival of the printing press

After the region of Veraguas was conquered, the two regions settled for a mutual dislike of each other. To the inhabitants of Azuero, their region was symbolic of the power of the people, while Veraguas represented an old, oppressive order. Diametrically, to the inhabitants of Veraguas, their region was a bastion of loyalty and morality, while Azuero was a hotbed for vice and treason.The tension between the two regions finally peaked when the first printing press arrived in Panama in 1820. Under the guidance of José María Goitía, the printing press was utilized to create a newspaper called La Miscelánea. Panamanians Mariano Arosemena, Manuel María Ayala, and Juan José Calvo, as well as Colombian Juan José Argote, formed the writing team of the new newspaper, whose stories would circulate throughout every town in the isthmus.

The newspaper was put to use in the service of the cause of independence. It circulated stories expounding the virtues of liberty, independence, and the teachings of the French Revolution, as well as stories of the great battles of Bolívar, the emancipation of the United States from their British masters, and the greatness of men such as Santander, Jose Martí, and other such messengers of freedom.

Due to the narrow area of circulation, those in the capital were able to transmit these intoxicating ideals to other such separatits, such as those in Azuero. In Veraguas, however, there remained a strict sense of submission to the Spanish Crown.

José de Fábrega

On November 10, 1821, the Grito de La Villa de Los Santos occurred. It was a unilateral decision by the residents of Azuero (without backing from Panama City) to declare their separation from the Spanish Empire. In both Veraguas and the capital this act was met with disdain, although on differing levels of said emotion. To Veraguas, it was the ultimate act of treason, while to the capital, it was seen as inefficient and irregular, and furthermore forced them to accelerate their plans.The Grito was an event that shook the isthmus to the core. It was a sign, on the part of the residents of Azuero, of their antagonism towards the independence movement in the capital, who in turn regarded the Azueran movement with contempt, since they (the capital movement) believed that their counterparts were fighting their right to rule, once the peninsulares (peninsular-born) were long gone.

It was, as well, an incredibly brave move on the part of Azuero, which lived in fear of Colonel José de Fábrega, and with good reason: the Colonel was a staunch loyalist, and had the entirety of the isthmus' military supplies in his hands. They feared quick retaliation and swift retribution against the separatists.

What they had not counted on, however, was the influence of the separatists in the capital. Ever since October 1821, when the former Governor General, Juan de la Cruz Mourgeón

Juan de la Cruz Mourgeón

Juan de la Cruz Mourgeón y Achet was a Spanish general and colonial administrator. He fought in the Spanish War of Independence against the French, and in the Viceroyalty of New Granada against rebels supporting independence...

, left the isthmus on a campaign in Quito and left the Veraguan colonel in charge, the separatists had been slowly converting Fábrega to the separatist side. As such, by November 10, Fábrega was now a supporter of the independence movement. Soon after the separatist declaration of Los Santos, Fábrega convened every organization in the capital with separatist interests and formally declared the city's support for independence. No military repercussions occurred due to the skillful bribing of royalist troops.

Having sealed the fate of the Spanish Crown's rule in Panama with his defection, Jóse de Fábrega now collaborated with the separatists in the capital to bring about a national assembly, where the fate of the country would be decided. Every region in Panama attended the assembly, including the former loyalist region of Veraguas, which was eventually convinced to join the revolution, out of the sheer fact that nothing more could be done for the royalist presence in Panama. Thus, on November 28, 1821, the national assembly was convened and it was officially declared (through Fábrega, who was invested with the title of Head of State of Panama) that the isthmus of Panama had severed its ties with the Spanish Empire and its decision to join New Granada and Venezuela in Bolivar's recently founded Republic of Colombia.

Posterior to the act, Fábrega wrote to Bolívar of the event, saying:

Exalted Sir,

I have the pleasure to communicate to Your Excellency the praiseworthy news of the Isthmus' decision of independence from Spanish dominion. The town of Los Santos, to the comprehension of this Province, was the first town to pronounce with enthusiasm the sacred name of Liberty and immediately almost every other town imitated their glorious example...

Inasmuch as I am concerned, Most Excellent Sir, the effusion of my gratitude is inexplicable, at having had the unique satisfaction capable of filling the human heart, as is to deserve the public confidence in circumstances so critical to govern the independent Isthmus; and I can only correspond to such high distinction with the sacrifices I am willing to make since I devoted myself, as it wished, to the mother country that has seen me be born and to who I owe all that I own...

Bólivar, in turn, replied,

It is not possible to me to express the feeling of joy and admiration that I have experimented to the knowledge that Panama, the center of the Universe, is segregated by itself and freed by its own virtue. The act of independence of Panama is the monument most glorious that any American province can give. Everything there is addressed; justice, generosity, policy and national interest. Transmit, then, you to those meritorious Colombians the tribute of my enthusiasm by their pure patriotism and true actions...

Panama and Colombia

Bolivar, well aware of geographical obstacles but also of the unique qualities and critical role in trade throughout history and under Spanish tutelage, had hesitated to include Panama in his Gran ColombiaGran Colombia

Gran Colombia is a name used today for the state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to 1831. This short-lived republic included the territories of present-day Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, northern Peru and northwest Brazil. The...

project. Besides the geographical argument, there was the fact that Simon Bolivar’s actions had been the decisive military factor in the independence of Venezuela, New Granada and Ecuador, while his role in Panama’s independence was none. Thus, while Bolivar knew that the nation of Panama was linked historically and culturally to South America, he was also conscious of the fact that the region was part of the Central American geography. This view is clearly seen in some of his famous documents and quotes such as his Carta de Jamaica (1815):

The Isthmian States, from Panama to Guatemala, will perhaps form an association. This magnificent position between the two great oceans could with time become the emporium of the universe. Its canals will shorten the distances of the world: they will narrow commercial ties between Europe, America and Asia; and bring to such fortunate region the tributes of the four parts of the globe. Perhaps some day only there could the capital of the world be established!

New Granada will join Venezuela, if they convene to form a new republic, their capital will be Maracaibo….This great nation would be called Colombia in tribute to the justice and gratitude of the creator of our hemisphere.

Nevertheless in 1821, convinced that under Bolivar's leadership the nation's destiny would move in the most progressive direction, the Isthmus joined Venezuela, New Granada (present day Colombia) and latter Ecuador, in 1822. The Republic of Colombia (1819–1830) or ‘Gran Colombia’ as it began to be called only after 1886, more or less corresponded in territory to the old colonial administrative district called the Viceroyalty of New Granada

Viceroyalty of New Granada

The Viceroyalty of New Granada was the name given on 27 May 1717, to a Spanish colonial jurisdiction in northern South America, corresponding mainly to modern Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela. The territory corresponding to Panama was incorporated later in 1739...

(1717–1819). While Panama had also been included in the Viceroyalty during the colonial period, the Isthmus' economic and political ties had been much closer, for all practical purposes, to the Viceroyalty of Peru (1542–1821).

In September 1830, under the guidance of General José Domingo Espinar, the local military commander who rebelled against the nation's central government in response to his being transferred to another command, Panama separated from the Republic of Colombia and requested that general Simón Bolívar

Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios Ponte y Yeiter, commonly known as Simón Bolívar was a Venezuelan military and political leader...

take direct command of the Isthmus Department. It made this a condition to its reunification with the rest of the country. Bolívar rejected Espinar's actions, and though he did not assume control of the isthmus as he desired, he called for Panama to rejoin the central state. Because of the overall political tension, Republic of Colombia's final days were approaching. Bolívar's vision for territorial unity disintegrated finally when General Juan Eligio Alzuru undertook a military coup against Espinar's authority. By early 1831, with order restored, Panama reincorporated itself to what was left of the republic -forming a territory now slightly larger than present day Panama and Colombia combined- which by then had adopted the name of Republic of New Granada

Republic of New Granada

The Republic of New Granada was a centralist republic consisting primarily of present-day Colombia and Panama with smaller portions of today's Ecuador, and Venezuela. It was created after the dissolution in 1830 of Gran Colombia. It was later abolished in 1858 when the Granadine Confederation was...

. The alliance of the two nations would last seventy years and prove precarious.

19th century Panama

By July 1831, as the new countries of Venezuela and Ecuador were being established, the isthmus would again reiterate its independence, now under the same General Alzuru as supreme military commander. Abuses committed by Alzuru's short-lived administration were countered by military forces under the command of Colonel Tomás de HerreraTomás de Herrera

Tomás José Ramón del Carmen de Herrera y Pérez Dávila was a neogranadine statesman and general who in 1840 became the first Head of State of the Free State of the Isthmus, now Panama...

, resulting in the defeat and execution of Alzuru in August, and the reestablishment of ties with New Granada.

In November 1840, during a civil war that had begun as a religious conflict, the isthmus under the leadership of -now General- Tomás Herrera, who assumed the title of Superior Civil Chief, declared its independence as did multiple other local authorities. The State of Panama took in March 1841 the name of 'Estado Libre del Istmo', or the Free State of the Isthmus. The new state established external political and economic ties and by March 1841, had drawn up a constitution which included the possibility for Panama to rejoin New Granada, but only as a federal district. Herrera's style was first changed to Superior Chief of State in March 1841 and in June 1841 to President. By the time the civil conflict ended and the government of New Granada and the government of the Isthmus had negotiated the Isthmus's reincorporation to the union, Panama's First Republic had been free for 13 months. Reunification happened on December 31, 1841.

In the end, the union between Panama and the Republic of New Granada (under its various names United States of Colombia 1863-1886 and the Republic of Colombia since 1886) was made possible by the active participation of U.S.A. under the 1846 Bidlack Mallarino treaty until 1903.

In the 1840s, two decades after the Monroe Doctrine

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a policy of the United States introduced on December 2, 1823. It stated that further efforts by European nations to colonize land or interfere with states in North or South America would be viewed as acts of aggression requiring U.S. intervention...

declared U.S. intentions to be the dominant anti-European imperial power in the Western Hemisphere

Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere or western hemisphere is mainly used as a geographical term for the half of the Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian and east of the Antimeridian , the other half being called the Eastern Hemisphere.In this sense, the western hemisphere consists of the western portions...

, North American and French interests became excited about the prospects of constructing railroads and/or canals through Central America to quicken trans-oceanic travel. At the same time it was clear that New Granada’s control over the isthmus was turning increasingly untenable. In 1846, the United States and New Granada signed the Bidlack Mallarino Treaty, granting the U.S. rights to build railroads

Rail transport