History of South Africa in the apartheid era

Encyclopedia

Apartheid was a system of racial segregation

enforced by the National Party

governments of South Africa

between 1948 and 1994, under which the rights of the majority 'non-white' inhabitants of South Africa were curtailed and white supremacy

and Afrikaner

minority rule was maintained. Apartheid was developed after World War II

by the Afrikaner

-dominated National Party and Broederbond organizations and was practiced also in South West Africa

, under South African administration under a League of Nations

mandate (revoked in 1966), until it gained independence as Namibia

in 1990.

Racial segregation in South Africa began in colonial times. However, apartheid as an official policy was introduced following the general election of 1948

. New legislation classified inhabitants into four racial groups ("native", "white", "coloured

", and "Asian"), and residential areas were segregated, sometimes by means of forced removals. Non-white political representation was completely abolished in 1970, and starting in that year black people

were deprived of their citizenship

, legally becoming citizens of one of ten tribally based self-governing

homelands called bantustan

s, four of which became nominally independent states. The government segregated education

, medical care, beaches, and other public services, and provided black people with services inferior to those of white people.

Apartheid sparked significant internal resistance

and violence as well as a long trade embargo against South Africa. Since the 1950s, a series of popular uprisings and protests were met with the banning of opposition and imprisoning of anti-apartheid leaders. As unrest spread and became more violent, state organisations responded with increasing repression and state-sponsored violence.

Reforms to apartheid in the 1980s failed to quell the mounting opposition, and in 1990 President Frederik Willem de Klerk

began negotiations to end apartheid, culminating in multi-racial democratic elections in 1994, which were won by the African National Congress

under Nelson Mandela

. The vestiges of apartheid still shape South African politics and society.

Under the 1806 Cape Articles of Capitulation the new British

Under the 1806 Cape Articles of Capitulation the new British

colonial rulers were required to respect the previous legislation enacted under Roman-Dutch law and this led to a separation of the law in South Africa from English Common Law

and a high degree of legislative autonomy. The governors and assemblies that governed the legal process in the various colonies of South Africa were then launched on a different and independent legislative path from the rest of the British Empire. In the days of slavery, slaves in general required passes to travel away from their masters. However, in 1797 the Landdrost and Heemraden of Swellendam and Graaff-Reinett (the Dutch colonial governing authority) extended pass laws

beyond slaves and ordained that all Hottentots moving about the country for any purpose should carry passes. This was confirmed by the British Colonial government in 1809 by the Hottentot Proclamation which decreed that if a Hottentot (and Khoikhoi) were to move they would need a pass from their master or a local official. Ordinance No. 49 of 1828 decreed that prospective black immigrants were to be granted passes for the sole purpose of seeking work. The Hottentot Proclamation was repealed by Ordnance 50 in 1828 for Coloreds and Khoikhoi but not for other Africans and other Africans were still forced to carry passes. The Slavery Abolition Act

1833 (3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom abolishing slavery throughout the British Empire and overrode the Cape Articles of Capitulation. To comply with the Slavery Abolition Act the South African legislation was expanded to include Ordinance 1 in 1835 which effectively changed the status of slaves to indentured labourers. This was followed by Ordinance 3 in 1848 which introduced an indenture system for Xhosa that was little different from slavery. The various South African colonies then passed legislation throughout the rest of the nineteenth century to limit the freedom of unskilled workers, to increase the restrictions on indentured workers and to regulate the relations between the races.

The Franchise and Ballot Act of 1892 instituted limits based on financial means and education to the black franchise

, and the Natal Legislative Assembly Bill of 1894 deprived Indians of the right to vote. In 1905 the General Pass Regulations Bill denied blacks the vote altogether, limited them to fixed areas and inaugurated the infamous Pass System. Then followed the Asiatic Registration Act (1906) requiring all Indians to register and carry passes. In 1910 the Union of South Africa

was created as a self-governing dominion

that continued the legislative program: the South Africa Act (1910) that enfranchised whites, giving them complete political control over all other race groups and removing the right of blacks to sit in parliament, the Native Land Act (1913) which prevented all blacks, except those in the Cape, from buying land outside "reserves", the Natives in Urban Areas Bill (1918) designed to force blacks into "locations", the Urban Areas Act (1923) which introduced residential segregation

and provided cheap labour for industry led by white people, the Colour Bar Act (1926), preventing anyone black from practising skilled trades, the Native Administration Act (1927) that made the British Crown, rather than paramount chief

s, the supreme head over all African affairs, the Native Land and Trust Act (1936) that complemented the 1913 Native Land Act and, in the same year, the Representation of Natives Act, which removed previous black voters from the Cape voters' roll. One of the first pieces of segregating legislation enacted by the Jan Smuts

' United Party

government was the Asiatic Land Tenure Bill (1946), which banned any further land sales to Indians.

For example, before the laws mine owners preferred hiring black workers because they were cheaper. Because the market forces direct against discrimination, the whites had to persuade the government to enact laws that highly restricted the black' rights to work, in order to get higher wages than their comparative performance would otherwise yield.

Jan Smuts

' United Party

government began to move away from the rigid enforcement of segregationist laws during World War II

. Amid fears integration would eventually lead the nation to racial assimilation, the legislature established the Sauer Commission

to investigate the effects of the United Party's policies. The commission concluded integration would bring about a "loss of personality" for all racial groups.

, the main Afrikaner nationalist party, the Herenigde Nasionale Party (Reunited National Party) under the leadership of Protestant cleric Daniel Francois Malan

, campaigned on its policy of apartheid. The NP narrowly defeated Smuts's United Party and formed a coalition government

with another Afrikaner nationalist party, the Afrikaner Party

. Malan became the first apartheid prime minister, and the two parties later merged to form the National Party

(NP).

National Party leaders argued that South Africa did not comprise a single nation, but was made up of four distinct racial groups: white, black, coloured, and Indian. These groups were split further into thirteen nations or racial federations. White people encompassed the English and Afrikaans

National Party leaders argued that South Africa did not comprise a single nation, but was made up of four distinct racial groups: white, black, coloured, and Indian. These groups were split further into thirteen nations or racial federations. White people encompassed the English and Afrikaans

language groups; the black populace was divided into ten such groups.

The state passed laws which paved the way for "grand apartheid", which was centred on separating races on a large scale, by compelling people to live in separate places defined by race (This strategy was in part adopted from "left-over" British rule that separated different racial groups after they took control of the Boer republics in the Anglo-Boer war. This created the so called black only "townships" or "locations" where blacks were relocated in their own towns). In addition, "petty apartheid" laws were passed. The principal apartheid laws were as follows:

The first grand apartheid law was the Population Registration Act

of 1950, which formalised racial classification and introduced an identity card for all persons over the age of eighteen, specifying their racial group. Official teams or Boards were established to come to an ultimate conclusion on those people whose race was unclear. This caused difficulty, especially for coloured people, separating their families as members were allocated different races.

The second pillar of grand apartheid was the Group Areas Act

of 1950. Until then, most settlements had people of different races living side by side. This Act put an end to diverse areas and determined where one lived according to race. Each race was allotted its own area, which was used in later years as a basis of forced removal. Further legislation in 1951 allowed the government to demolish black shackland

slums and forced white employers to pay for the construction of housing for those black workers who were permitted to reside in cities otherwise reserved for white people.

The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act

of 1949 prohibited marriage between persons of different races, and the Immorality Act

of 1950 made sexual relations with a person of a different race

a criminal offence.

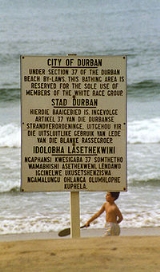

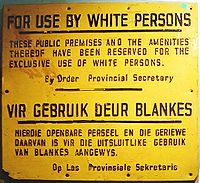

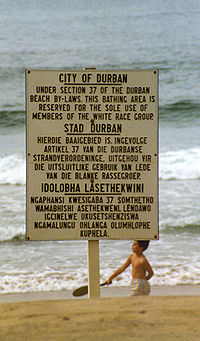

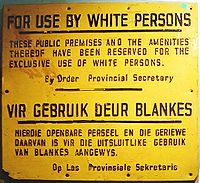

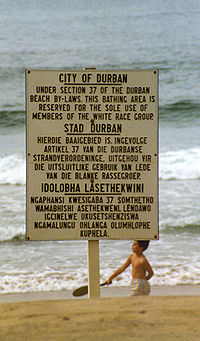

Under the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act

of 1953, municipal grounds could be reserved for a particular race, creating, among other things, separate beaches, buses, hospitals, schools and universities. Signboards such as "whites only" applied to public areas, even including park benches. Black people were provided with services greatly inferior to those of whites, and, to a lesser extent, to those of Indian and coloured people. An act of 1956 formalised racial discrimination

in employment.

Further laws had the aim of suppressing resistance, especially armed resistance, to apartheid. The Suppression of Communism Act

of 1950 banned the South African Communist Party

and any other political party

that the government chose to label as 'communist'. Disorderly gatherings were banned, as were certain organisations that were deemed threatening to the government.

Education

was segregated by means of the 1953 Bantu Education Act

, which crafted a separate system of education for African students and was designed to prepare black people for lives as a labouring class. In 1959 separate universities were created for black, coloured and Indian people. Existing universities were not permitted to enroll new black students. The Afrikaans Medium Decree of 1974 required the use of Afrikaans

and English on an equal basis in high schools outside the homelands.

The Bantu Authorities Act of 1951 created separate government structures for black and white citizens and was the first piece of legislation established to support the government's plan of separate development in the Bantustans. The Promotion of Black Self-Government Act of 1958 entrenched the National Party's policy of nominally independent "homelands" for black people. So-called "self–governing Bantu units" were proposed, which would have devolved administrative powers, with the promise later of autonomy

and self-government. The Bantu Investment Corporation Act of 1959 set up a mechanism to transfer capital to the homelands in order to create employment there. Legislation of 1967 allowed the government to stop industrial development in "white" cities and redirect such development to the "homelands". The Black Homeland Citizenship Act

of 1970 marked a new phase in the Bantustan strategy. It changed the status of black people living in South Africa so that they were no longer citizens of South Africa, but became citizens of one of the ten autonomous territories. The aim was to ensure a demographic majority of white people within South Africa by having all ten Bantustans achieve full independence.

Interracial contact in sport was frowned upon, but there were no segregatory sports laws.

The government tightened existing pass laws, compelling black South Africans to carry identity documents to prevent the migration of blacks to South Africa. Any black residents of cities had to be in employment. Up until 1956 women were for the most part excluded from these pass requirements as attempts to introduce pass laws for women were met with fierce resistance.

was needed in order to change the entrenched clauses of the Constitution. The government then introduced the High Court of Parliament Bill (1952), which gave parliament the power to overrule decisions of the court. The Cape Supreme Court and the Appeal Court declared this invalid too.

In 1955 the Strijdom government increased the number of judges in the Appeal Court from five to eleven, and appointed pro-Nationalist judges to fill the new places. In the same year they introduced the Senate Act, which increased the senate from 49 seats to 89. Adjustments were made such that the NP controlled 77 of these seats. The parliament met in a joint sitting and passed the Separate Representation of Voters Act

in 1956, which transferred coloured voters from the common voters' roll in the Cape to a new coloured voters' roll. Immediately after the vote, the Senate was restored to its original size. The Senate Act was contested in the Supreme Court, but the recently enlarged Appeal Court, packed with government-supporting judges, rejected the application by the Opposition and upheld the Senate Act, and also the Act to remove coloured voters.

pro-republic conservative and the largely English anti-republican liberal

sentiments, with the legacy of the Boer War

still a factor for some people. Once republican status was attained, Verwoerd

called for improved relations and greater accord between those of British descent and the Afrikaners. He claimed that the only difference now was between those who supported apartheid and those in opposition to it. The ethnic divide would no longer be between Afrikaans speakers and English speakers, but rather white and black ethnicities. Most Afrikaners supported the notion of unanimity of white people to ensure their safety. White voters of British descent were divided. Many had opposed a republic, leading to a majority "no" vote in Natal

. Later, however, some of them recognised the perceived need for white unity, convinced by the growing trend of decolonisation elsewhere in Africa, which left them apprehensive. Harold Macmillan

's "Wind of Change

" pronouncement left the British faction feeling that Britain had abandoned them. The more conservative English-speakers gave support to Verwoerd; others were troubled by the severing of ties with Britain and remained loyal to the Crown. They were acutely displeased at the choice between British and South African nationality. Although Verwoerd tried to bond these different blocs, the subsequent ballot illustrated only a minor swell of support, indicating that a great many English speakers remained apathetic and that Verwoerd had not succeeded in uniting the white population.

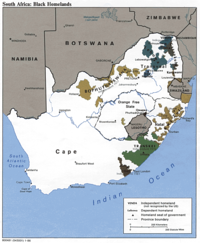

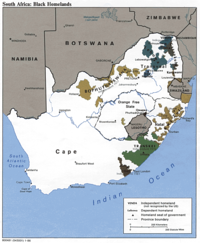

Under the homeland system, the South African government attempted to divide South Africa into a number of separate states, each of which was supposed to develop into a separate nation-state for a different ethnic group.

Under the homeland system, the South African government attempted to divide South Africa into a number of separate states, each of which was supposed to develop into a separate nation-state for a different ethnic group.

Territorial separation was not a new institution. There were, for example, the "reserves" created under the British government in the nineteenth century. Under apartheid, some thirteen per cent of the land was reserved for black homelands, a relatively small amount compared to the total population, and generally in economically unproductive areas of the country. The Tomlinson Commission of 1954 justified apartheid and the homeland system, but stated that additional land ought to be given to the homelands, a recommendation which was not carried out.

With the accession to power of Dr Hendrik Frensch Verwoerd

in 1958, the policy of "separate development" came into being, with the homeland structure as one of its cornerstones. Verwoerd came to believe in the granting of independence to these homelands. The government justified its plans on the basis that "(the) government's policy is, therefore, not a policy of discrimination on the grounds of race or colour, but a policy of differentiation on the ground of nationhood, of different nations, granting to each self-determination within the borders of their homelands – hence this policy of separate development". Under the homelands system, blacks would no longer be citizens of South Africa; they would instead become citizens of the independent homelands who merely worked in South Africa as foreign migrant labourers on temporary work permits. In 1958 the Promotion of Black Self-Government Act was passed, and border industries and the Bantu Investment Corporation were established to promote economic development and the provision of employment in or near the homelands. Many black South Africans who had never resided in their identified homeland were nonetheless forcibly removed from the cities to the homelands.

Ten homelands were ultimately allocated to different black ethnic groups: Lebowa

(North Sotho

, also referred to as Pedi), QwaQwa

(South Sotho), Bophuthatswana

(Tswana), KwaZulu

(Zulu), KaNgwane

(Swazi), Transkei

and Ciskei

(Xhosa), Gazankulu

(Tsonga

), Venda

(Venda

) and KwaNdebele

(Ndebele). Four of these were declared independent by the South African government: (Transkei in 1976, Bophuthatswana in 1977, Venda in 1979, and Ciskei in 1981) (also known as the TBVC states).

Once a homeland was granted its nominal independence, its designated citizens had their South African citizenship revoked, replaced with citizenship in their homeland. These people were then issued passports instead of passbooks. Citizens of the nominally autonomous homelands also had their South African citizenship circumscribed, meaning they were no longer legally considered South African. The South African government attempted to draw an equivalence between their view of black citizens of the homelands and the problems which other countries faced through entry of illegal immigrants.

and Ciskei

homelands. The best-publicised forced removals of the 1950s occurred in Johannesburg

, when 60,000 people were moved to the new township of Soweto

, an abbreviation for South Western Townships.

Until 1955 Sophiatown had been one of the few urban areas where blacks were allowed to own land, and was slowly developing into a multiracial slum. As industry in Johannesburg grew, Sophiatown became the home of a rapidly expanding black workforce, as it was convenient and close to town. It could also boast the only swimming pool for black children in Johannesburg. As one of the oldest black settlements in Johannesburg, Sophiatown held an almost symbolic importance for the 50,000 blacks it contained, both in terms of its sheer vibrancy and its unique culture. Despite a vigorous ANC protest campaign and worldwide publicity, the removal of Sophiatown began on 9 February 1955 under the Western Areas Removal Scheme. In the early hours, heavily armed police entered Sophiatown to force residents out of their homes and load their belongings onto government trucks. The residents were taken to a large tract of land, thirteen miles (19 km) from the city centre, known as Meadowlands

(that the government had purchased in 1953). Meadowlands became part of a new planned black city called Soweto. The Sophiatown slum was destroyed by bulldozers, and a new white suburb named Triomf (Triumph) was built in its place. This pattern of forced removal and destruction was to repeat itself over the next few years, and was not limited to people of African descent. Forced removals from areas like Cato Manor (Mkhumbane) in Durban

, and District Six in Cape Town

, where 55,000 coloured and Indian people were forced to move to new townships on the Cape Flats, were carried out under the Group Areas Act

of 1950. Ultimately, nearly 600,000 coloured, Indian and Chinese people

were moved in terms of the Group Areas Act. Some 40,000 white people were also forced to move when land was transferred from "white South Africa" into the black homelands.

The National Party passed a string of legislation which became known as petty apartheid. The first of these was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act 55 of 1949, prohibiting marriage between white people and people of other races. The Immorality Amendment Act 21 of 1950 (as amended in 1957 by Act 23) forbade "unlawful racial intercourse" and "any immoral or indecent act" between a white person and an African, Indian or coloured person.

The National Party passed a string of legislation which became known as petty apartheid. The first of these was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act 55 of 1949, prohibiting marriage between white people and people of other races. The Immorality Amendment Act 21 of 1950 (as amended in 1957 by Act 23) forbade "unlawful racial intercourse" and "any immoral or indecent act" between a white person and an African, Indian or coloured person.

Blacks were not allowed to run businesses or professional practices in those areas designated as "white South Africa" without a permit. They were supposed to move to the black "homelands" and set up businesses and practices there. Transport and civil facilities were segregated. Black buses stopped at black bus stops and white buses at white ones. Trains, hospitals and ambulances were segregated. Because of the smaller numbers of white patients and the fact that white doctors preferred to work in white hospitals, conditions in white hospitals were much better than those in often overcrowded black hospitals. Blacks were excluded from living or working in white areas, unless they had a pass—nicknamed the dompas ("dumb pass" in Afrikaans). Only blacks with "Section 10" rights (those who had migrated to the cities before World War II) were excluded from this provision. A pass was issued only to a black person with approved work. Spouses and children had to be left behind in black homelands. A pass was issued for one magisterial district (usually one town) confining the holder to that area only. Being without a valid pass made a person subject to arrest and trial for being an illegal migrant. This was often followed by deportation to the person's homeland

and prosecution of the employer (for employing an illegal migrant). Police vans patrolled the white areas to round up illegal blacks found there without passes. Black people were not allowed to employ white people in white South Africa.

Although trade union

s for black and coloured

(mixed race) workers had existed since the early 20th century, it was not until the 1980s reforms that a mass black trade union movement developed.

In the 1970s each black child's education within the Bantu Education system (the education system practised in black schools within white South Africa) cost the state only a tenth of each white child's. Higher education was provided in separate universities and colleges after 1959. Eight black universities were created in the homelands. Fort Hare University in the Ciskei

(now Eastern Cape) was to register only Xhosa

-speaking students. Sotho, Tswana, Pedi and Venda

speakers were placed at the newly founded University College of the North

at Turfloop, while the University College of Zululand

was launched to serve Zulu scholars. Coloureds and Indians were to have their own establishments in the Cape

and Natal

respectively.

In addition, each black homeland controlled its own separate education, health and police system. Blacks were not allowed to buy hard liquor. They were able only to buy state-produced poor quality beer (although this was relaxed later). Public beaches were racially segregated. Public swimming pools, some pedestrian bridges, drive-in cinema parking spaces, graveyards, parks, and public toilets were segregated. Cinemas and theatres in white areas were not allowed to admit blacks. There were practically no cinemas in black areas. Most restaurants and hotels in white areas were not allowed to admit blacks except as staff. Black Africans were prohibited from attending white churches under the Churches Native Laws Amendment Act of 1957. This was, however, never rigidly enforced, and churches were one of the few places races could mix without the interference of the law. Blacks earning 360 rand

a year, 30 rand a month, or more had to pay taxes while the white threshold was more than twice as high, at 750 rand a year, 62.5 rand per month. On the other hand, the taxation rate for whites was considerably higher than that for blacks.

Blacks could never acquire land in white areas. In the homelands, much of the land belonged to a 'tribe', where the local chieftain would decide how the land had to be used. This resulted in white people owning almost all the industrial and agricultural lands and much of the prized residential land. Most blacks were stripped of their South African citizenship when the "homelands" became "independent". Thus, they were no longer able to apply for South African passports. Eligibility requirements for a passport had been difficult for blacks to meet, the government contending that a passport was a privilege, not a right. As such, the government did not grant many passports to blacks. Apartheid pervaded South African culture, as well as the law. This was reinforced by much of the media, and the lack of opportunities for the races to mix in a social setting entrenched social distance between people.

, European

and Malay

ancestry. Many were descended from people brought to South Africa from other parts of the world, such as India

, Madagascar

, China

and the Philippines

, as slaves

and indentured workers.

The Apartheid bureaucracy devised complex (and often arbitrary) criteria at the time that the Population Registration Act was implemented to determine who was Coloured. Minor officials would administer tests to determine if someone should be categorised either Coloured or Black, or if another person should be categorised either Coloured or White. Different members of the same family found themselves in different race groups. Further tests determined membership of the various sub-racial groups of the Coloureds. Many of those who formerly belonged to this racial group are opposed to the continuing use of the term "coloured" in the post-apartheid era, though the term no longer signifies any legal meaning. The expressions 'so-called Coloured' (Afrikaans

sogenaamde Kleurlinge) and 'brown people' (bruinmense) acquired a wide usage in the 1980s.

Discriminated against by apartheid, Coloureds were as a matter of state policy forced to live in separate townships

—in some cases leaving homes their families had occupied for generations—and received an inferior education, though better than that provided to Black South Africans. They played an important role in the anti-apartheid movement

: for example the African Political Organization

established in 1902 had an exclusively coloured membership.

Voting rights were denied to Coloured

s in the same way that they were denied to blacks from 1950 to 1983. However, in 1977 the NP caucus approved proposals to bring coloured and Indians into central government. In 1982, final constitutional proposals produced a referendum among white voters, and the Tricameral Parliament

was approved. The Constitution was reformed the following year to allow the Coloured and Asian minorities participation in separate Houses in a Tricameral Parliament, and Botha became the first Executive State President. The idea was that the Coloured minority could be granted voting rights, but the Black majority were to become citizens of independent homelands. These separate arrangements continued until the abolition of apartheid. The Tricameral reforms led to the formation of the (anti-apartheid) UDF as a vehicle to try and prevent the co-option of coloureds and Indians into an alliance with white South Africans. The subsequent battles between the UDF and the NP government from 1983 to 1989 were to become the most intense period of struggle between left-wing and right-wing South Africans.

and apartheid had a major impact on women since they suffered both racial and gender discrimination. Oppression against African women was different from discrimination against men. They had very few or no legal rights, no access to education and no right to own property. Jobs were often hard to find but many African women worked as agricultural or domestic workers though wages were extremely low, if existent. Children suffered from diseases caused by malnutrition and sanitary problems, and mortality rates were therefore high. The controlled movement of African workers within the country through the Natives Urban Areas Act of 1923 and the pass-laws, separated family members from one another as men usually worked in urban centres, while women were forced to stay in rural areas. Marriage law and births were also controlled by the government and the pro-apartheid Dutch Reformed Church

, who tried to restrict African birth rates.

While football was plagued by racism, it also played a role in protesting apartheid and its policies. With the international bans from FIFA and other major sporting events, South Africa would be in the spotlight internationally. In a 1977 survey, white South Africans ranked the lack of international sport as one of the three most damaging consequences of apartheid. By the mid-fifties, Black South Africans would also use media to challenge the "racialisation" of sports in South Africa; anti-apartheid forces had begun to pinpoint sport as the 'weakness' of white national morale. Black journalists on the Johannesburg Drum magazine were the first to give the issue public exposure, with an intrepid special issue in 1955 that asked, "Why shouldn't our blacks be allowed in the SA team?" As time progressed, international standing with South Africa would continue to be strained. In the 80s, as the oppressive system was slowly collapsing the ANC and National Party started negotiations on the end of apartheid. Football associations also discussed the formation of a single, non-racial controlling body. This unity process accelerated in the late 1980s and led to the creation, in December 1991, of an incorporated South African Football Association. On 3 July 1992, FIFA finally welcomed South Africa back into international football.

, with which South Africa maintained diplomatic and economic relations, were considered "honorary whites

" with the same privileges as normal whites.

. Pornography, gambling and other such vices were banned. Cinemas, shops selling alcohol and most other businesses were forbidden from operating on Sundays. Abortion

, homosexuality

and sex education

were also restricted; abortion was legal only in cases of rape or if the mother's life was threatened.

Television was not introduced

until 1976 because the government viewed it as dangerous. Television was also run on apartheid lines – TV1 broadcast in Afrikaans and English (geared to a white audience), TV2 in Zulu and Xhosa and TV3 in Sotho, Tswana and Pedi (both geared to a black audience), and TV4 mostly showed programmes for an urban-black audience.

Internal resistance to the apartheid system in South Africa came from several sectors of society and saw the creation of organisations dedicated variously to peaceful protests, passive resistance and armed insurrection.

In 1949 the youth wing

of the African National Congress

(ANC) took control of the organisation and started advocating a radical black nationalist programme. The new young leaders proposed that white authority could only be overthrown through mass campaigns. In 1950 that philosophy saw the launch of the Programme of Action, a series of strikes, boycotts and civil disobedience actions that led to occasionally violent clashes with the authorities.

In 1959 a group of disenchanted ANC members formed the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), which organised a demonstration against pass books on 21 March 1960. One of those protests was held in the township of Sharpeville, where 69 people were killed by police in the Sharpeville massacre

.

In the wake of the Sharpeville incident the government declared a state of emergency. More than 18 000 people were arrested, including leaders of the ANC and PAC, and both organisations were banned. The resistance went underground, with some leaders in exile abroad and others engaged in campaigns of domestic sabotage and terrorism.

In May 1961, before the declaration of South Africa as a Republic, an assembly representing the banned ANC called for negotiations between the members of the different ethnic groupings, threatening demonstrations and strikes during the inauguration of the Republic if their calls were ignored.

When the government overlooked them, the strikers (among the main organizers was a 42-year-old, Thembu

-origin Nelson Mandela

) carried out their threats. The government countered swiftly by giving police the authority to arrest people for up to twelve days and detaining many strike leaders amid numerous cases of police brutality. Defeated, the protesters called off their strike. The ANC then chose to launch an armed struggle through a newly formed military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe

(MK), which would perform acts of sabotage on tactical state structures. Its first sabotage plans were carried out on 16 December 1961, the anniversary of the Battle of Blood River

.

In the 1970s the Black Consciousness Movement was created by tertiary students influenced by the American Black Power movement. BC endorsed black pride and African customs and did much to alter the feelings of inadequacy instilled among black people by the apartheid system. The leader of the movement, Steve Biko

, was taken into custody on 18 August 1977 and was murdered in detention.

In 1976 secondary students in Soweto

took to the streets in the Soweto uprising to protest against forced tuition in Afrikaans. On 16 June, police opened fire on students in what was meant to be a peaceful protest. According to official reports 23 people were killed, but news agencies put the number as high as 600 killed and 4000 injured. In the following years several student organisations were formed with the goal of protesting against apartheid, and these organisations were central to urban school boycotts in 1980 and 1983 as well as rural boycotts in 1985 and 1986.

In parallel to student protests, labour unions started protest action in 1973 and 1974. After 1976 unions and workers are considered to have played an important role in the struggle against apartheid, filling the gap left by the banning of political parties. In 1979 black trade unions were legalised and could engage in collective bargaining, although strikes were still illegal.

At roughly the same time churches and church groups also emerged as pivotal points of resistance. Church leaders were not immune to prosecution, and certain faith-based organisations were banned, but the clergy generally had more freedom to criticise the government than militant groups did.

Although the majority of whites supported apartheid, some 20 percent did not. Parliamentary opposition was galvanised by Helen Suzman

, Colin Eglin

and Harry Schwarz

who formed the Progressive Federal Party

. Extra-parliamentary resistance was largely centred in the South African Communist Party

and women's organisation the Black Sash

. Women were also notable in their involvement in trade union organisations and banned political parties.

Harold Macmillan

criticised them during his celebrated Wind of Change speech

in Cape Town

. Weeks later, tensions came to a head in the Sharpeville Massacre

, resulting in more international condemnation. Soon thereafter, Verwoerd announced a referendum on whether the country should become a republic. Verwoerd lowered the voting age for whites to eighteen and included whites in South West Africa

on the voter's roll. The referendum on 5 October that year asked whites, "Are you in favour of a Republic for the Union?", and 52 percent voted "Yes".

As a consequence of this change of status, South Africa needed to reapply for continued membership of the Commonwealth

, with which it had privileged trade links. Even though India

became a republic within the Commonwealth in 1950 it became clear that African and Asian member states would oppose South Africa due to its apartheid policies. As a result, South Africa withdrew from the Commonwealth on 31 May 1961, the day that the Republic came into existence.

In April 1960, the UN's conservative stance on apartheid changed following the Sharpeville massacre

, and the Security Council for the first time agreed on concerted action against the apartheid regime, demanding an end to racial separation and discrimination. From 1960 the ANC began a campaign of armed struggle of which there would later be a charge of 193 acts of terrorism from 1961 to 1963, mainly bombings and murders of civilians.

Instead, the South African government then began further suppression, banning the ANC and PAC. In 1961, UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld

stopped over in South Africa and subsequently stated that he had been unable to reach agreement with Prime Minister Verwoerd.

On 6 November 1962, the United Nations General Assembly

passed Resolution 1761

, condemning South African apartheid policies. In 1966, the UN held the first of many colloquiums on apartheid. The General Assembly announced 21 March as the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, in memory of the Sharpeville massacre. In 1971, the General Assembly formally denounced the institution of homelands, and a motion was passed in 1974 to expel South Africa from the UN, but this was vetoed by France, Britain and the United States of America, all key trade associates of South Africa.

On 7 August 1963 the United Nations Security Council

passed Resolution 181

calling for a voluntary arms embargo

against South Africa, and in the same year, a Special Committee Against Apartheid was established to encourage and oversee plans of action against the regime. From 1964, the US and Britain discontinued their arms trade with South Africa. It also condemned the Soweto massacre in Resolution 392

. In 1977, the voluntary UN arms embargo became mandatory with the passing of United Nations Security Council Resolution 418

.

Economic sanctions against South Africa were also frequently debated as an effective way of putting pressure on the apartheid government. In 1962, the UN General Assembly requested that its members sever political, fiscal and transportation ties with South Africa. In 1968, it proposed ending all cultural, educational and sporting connections as well. Economic sanctions, however, were not made mandatory, because of opposition from South Africa's main trading partners.

In 1973, the UN adopted the Apartheid Convention which defines apartheid and even qualifies it as a crime against humanity

which might lead to international criminal prosecution of the individuals responsible for perpetrating it.

In 1978 and 1983 the UN condemned South Africa at the World Conference Against Racism

, and a significant divestment movement

started, pressuring investors to disinvest from South African companies or companies that did business with South Africa.

After much debate, by the late 1980s the United States, the United Kingdom, and 23 other nations had passed laws placing various trade sanctions on South Africa. A divestment

movement in many countries was similarly widespread, with individual cities and provinces around the world implementing various laws and local regulations forbidding registered corporations under their jurisdiction from doing business with South African firms, factories, or banks.

, Zambia, and formulated the 'Lusaka Manifesto', which was signed on 13 April by all of the countries in attendance except Malawi

. This manifesto was later taken on by both the OAU and the United Nations.

The Lusaka Manifesto summarised the political situations of self-governing African countries, condemning racism and inequity, and calling for black majority rule in all African nations. It did not rebuff South Africa entirely, though, adopting an appeasing manner towards the apartheid government, and even recognising its autonomy. Although African leaders supported the emancipation of black South Africans, they preferred this to be attained through peaceful means.

South Africa's negative response to the Lusaka Manifesto and rejection of a change to her policies brought about another OAU announcement in October 1971. The Mogadishu Declaration declared that South Africa's rebuffing of negotiations meant that her black people could only be freed through military means, and that no African state should converse with the apartheid government. Henceforth, it would be up to South Africa to keep contact with other African states.

was made South African Prime Minister. He was not prepared to dismantle apartheid, but he did try to redress South Africa's isolation and to revitalise the country's global reputation, even those with black-ruled nations in Africa. This he called his "Outward-Looking" policy; the buzzwords for his strategy were "dialogue" and "détente", signifying a reduction of tension.

Vorster's willingness to talk to African leaders stood in contrast to Verwoerd's refusal to engage with leaders such as Abubakar Tafawa Balewa

of Nigeria

in 1962 and Kenneth Kaunda

of Zambia

in 1964. In 1966, Vorster met with the heads of the neighbouring states of Lesotho

, Swaziland and Botswana

. In 1967, Vorster offered technological and financial aid to any African state prepared to receive it, asserting that no political strings were attached, aware that many African states needed financial aid despite their opposition to South Africa's racial policies. Many were also tied to South Africa economically because of their migrant labour population working on the South African mines. Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland remained outspoken critics of apartheid, but depended on South Africa's economic aid.

Malawi was the first country not on South African borders to accept South African aid. In 1967, the two states set out their political and economic relations, and, in 1969, Malawi became the only country at the assembly which did not sign the Lusaka Manifesto condemning South Africa' apartheid policy. In 1970, Malawian president Hastings Banda

made his first and most successful official stopover in South Africa.

Associations with Mozambique followed suit and were sustained after that country won its sovereignty in 1975. Angola was also granted South African loans. Other countries which formed relationships with South Africa were Liberia

, Ivory Coast, Madagascar, Mauritius

, Gabon, Zaire

(now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), Ghana

and the Central African Republic

. Although these states condemned apartheid (more than ever after South Africa's denunciation of the Lusaka Manifesto), South Africa's economic and military dominance meant that they remained dependent on South Africa to varying degrees.

severed its ties with the all-white South African Table Tennis Union, preferring the non-racial South African Table Tennis Board. The apartheid government responded by confiscating the passports of the Board's players so that they were unable to attend international games.

In 1959, the non-racial South African Sports Association (SASA) was formed to secure the rights of all players on the global field. After meeting with no success in its endeavours to attain credit by collaborating with white establishments, SASA approached the International Olympic Committee

(IOC) in 1962, calling for South Africa's expulsion from the Olympic Games. The IOC sent South Africa a caution to the effect that, if there were no changes, they would be barred from the 1964 Olympic Games

. The changes were initiated, and in January 1963, the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (SANROC) was set up. The Anti-Apartheid Movement persisted in its campaign for South Africa's exclusion, and the IOC acceded in barring the country from the 1964 Games in Tokyo

. South Africa selected a multi-racial team for the next Games, and the IOC opted for incorporation in the 1968 Games in Mexico

. Because of protests from AAMs and African nations, however, the IOC was forced to retract the invitation.

Foreign complaints about South Africa's bigoted sports brought more isolation. Racially selected New Zealand sports teams toured South Africa, until the 1970 New Zealand All Blacks

rugby tour allowed Maori to go under the status of 'honorary whites'. Huge and widespread protest occurred in New Zealand in 1981 against the Springbok tour, the government spent eight million dollars protecting games using the army and police force. A planned All Black tour to South Africa in 1985 remobilised the New Zealand protestors and it was cancelled. A 'rebel tour' not government sanctioned went ahead in 1986, but after that sporting ties were cut, and New Zealand made a decision not to convey an authorised rugby team to South Africa until the end of apartheid.

B. J. Vorster took Verwoerd's place as PM in 1966 and declared that South Africa would no longer dictate to other countries what their teams should look like. Although this reopened the gate for sporting meets, it did not signal the end of South Africa's racist sporting policies. In 1968, Vorster went against his policy by refusing to permit Basil D'Oliveira

, a Coloured South African-born cricketer, to join the English cricket team on its tour to South Africa. Vorster said that the side had been chosen only to prove a point, and not on merit. After protests, however, "Dolly" was eventually included in the team. Protests against certain tours brought about the cancellation of a number of other visits, like that of an England rugby team in 1969/70.

The first of the "White Bans" occurred in 1971 when the Chairman of the Australian Cricketing Association, Don Bradman flew to South Africa to meet with the South African Prime Minister John Vorster. The Prime Minister had expected Bradman to allow the tour of the Australian cricket team to go ahead, but things became heated after Bradman asked why black sportsmen were not allowed to play cricket. Vorster stated that blacks were intellectually inferior and had no finesse for the game. Bradman, thinking this ignorant and repugnant, asked Vorster if he had heard of a man named Garry Sobers. On his return to Australia, Bradman released a one sentence statement:

"We will not play them until they choose a team on a non-racist basis."

In South Africa, Vorster vented his anger publicly against Bradman, while the African National Congress rejoiced. This was the first time a predominantly white nation had taken the side of multiracial sport, producing an unsettling resonance that more "White" boycotts were coming.

Almost twenty years later, on his release from prison, Nelson Mandela asked a visiting Australian statesman if Donald Bradman, his childhood hero, was still alive.

In 1971, Vorster altered his policies even further by distinguishing multiracial from multinational sport. Multiracial sport, between teams with players of different races, remained outlawed; multinational sport, however, was now acceptable: international sides would not be subject to South Africa's racial stipulations.

In 1978

, Nigeria boycott

ed the Commonwealth Games because New Zealand's sporting contacts with the South African government were not considered to be in accordance with the 1977 Gleneagles Agreement

. Nigeria also led the 32-nation boycott of the 1986 Commonwealth Games

because of British prime minister Margaret Thatcher

's ambivalent attitude towards sporting links with South Africa, significantly affecting the quality and profitability of the Games and thus thrusting apartheid into the international spotlight.

Sporting bans were revoked in 1993, when conciliations for a democratic South Africa were well under way.

In the 1960s, the Anti-Apartheid Movements began to campaign for cultural boycotts of apartheid South Africa. Artists were requested not to present or let their works be hosted in South Africa. In 1963, 45 British writers put their signatures to an affirmation approving of the boycott, and, in 1964, American actor Marlon Brando

called for a similar affirmation for films. In 1965, the Writers' Guild of Great Britain

called for a proscription on the sending of films to South Africa. Over sixty American artists signed a statement against apartheid and against professional links with the state. The presentation of some South African plays in Britain and the United States was also vetoed. After the arrival of television in South Africa in 1975, the British Actors Union, Equity, boycotted the service, and no British programme concerning its associates could be sold to South Africa. Sporting and cultural boycotts did not have the same impact as economic sanctions, but they did much to lift consciousness amongst normal South Africans of the global condemnation of apartheid.

in particular provided both moral and financial support for the ANC. On 21 February 1986 a week before he was murdered Sweden

's prime minister Olof Palme

made the keynote

address to the Swedish People's Parliament Against Apartheid held in Stockholm

. In addressing the hundreds of anti-apartheid sympathizers as well as leaders and officials from the ANC and the Anti-Apartheid Movement

such as Oliver Tambo

, Palme declared:

Other Western countries adopted a more ambivalent position. In the 1980s, both the Reagan

and Thatcher

administrations, in the USA and UK respectively, followed a 'constructive engagement

' policy with the apartheid government, vetoing the imposition of UN economic sanctions on South Africa, justified by a belief in free trade and a vision of South Africa as a bastion against Marxist forces in Southern Africa. Thatcher declared the ANC a terrorist organisation, and in 1987 her spokesman, Bernard Ingham

, famously said that anyone who believed that the ANC would ever form the government of South Africa was "living in cloud cuckoo land

".

By the late 1980s, however, with the tide of the Cold War

turning and no sign of a political resolution in South Africa, Western patience with the apartheid government began to run out. By 1989, a bipartisan Republican

/Democratic

initiative in the US favoured economic sanctions

(realised as the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act

of 1986), the release of Nelson Mandela

and a negotiated settlement involving the ANC. Thatcher too began to take a similar line, but insisted on the suspension of the ANC's armed struggle.

Britain's significant economic involvement in South Africa may have provided some leverage

with the South African government, with both the UK and the US applying pressure on the government, and pushing for negotiations. However, neither Britain nor the US were willing to apply economic pressure upon their multinational interests in South Africa, such as the mining company Anglo American. Although a high-profile compensation claim against these companies was thrown out of court in 2004, the US Supreme Court in May 2008 upheld an appeal court ruling allowing another lawsuit that seeks damages of more than US$400 billion from major international companies which are accused of aiding South Africa's apartheid system.

). Initially South Africa fought a counter-insurgency

war against SWAPO. This conflict deepened after Angola

gained its independence in 1975 under the leadership of the leftist Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola

(MPLA) aided by Cuba

. South Africa, Zaire and the United States sided with the Angolan rival UNITA

party against the MPLA's armed force, FAPLA (People's Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola

). The following struggle turned into one of several late Cold War

flashpoints in the world. The Angolan civil war

developed into a conventional war with South Africa and UNITA on one side against the Angolan government, the Soviet volunteers, the Cubans and SWAPO on the other.

besieged by communism and radical black nationalists. Considerable effort was put into circumventing sanctions

, and the government even went so far as to develop nuclear weapons

, with the help of Israel

. In 2010, The Guardian

released South African government documents that revealed an Israeli offer to sell Apartheid South Africa nuclear weapons. Israel categorically denied these allegations and claimed that the documents were minutes from a meeting which did not indicate any concrete offer for a sale of nuclear weapons. Shimon Peres

said that The Guardian article was based on "selective interpretation... and not on concrete facts."

The term "front-line states" referred to countries in Southern Africa geographically near South Africa. Although these front-line states were all opposed to apartheid, many were economically dependent on South Africa. In 1980, they formed the Southern African Development Coordination Conference

(SADCC), the aim of which was to promote economic development in the region and hence reduce dependence on South Africa. Furthermore, many SADCC members also allowed the exiled ANC and Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) to establish bases in their countries.

s of the ANC, PAC and SWAPO in neighbouring countries beginning in the early 1980s. These attacks were in retaliation for acts of terror such as bomb explosions, massacres and guerrilla actions (like sabotage) by ANC, PAC and SWAPO guerrillas in South Africa and Namibia. The country also aided organisations in surrounding countries who were actively combating the spread of communism in southern Africa. The results of these policies included:

In 1984, Mozambican president Samora Machel

signed the Nkomati Accord

with South Africa's president P.W. Botha, in an attempt to rebuild Mozambique's economy. South Africa agreed to cease supporting anti-government forces, while the MK was prohibited from operating in Mozambique. This was a setback for the ANC. Two years later, President Machel was killed in an air crash

in mountainous terrain in South Africa near the Mozambican border after returning from a meeting in Zambia

. South Africa was accused by the Mozambican government and U.S. Secretary of State George P. Shultz

of continuing its aid to RENAMO and having caused the accident by using a false radio navigation

beacon to lure the aircraft into crashing. This conspiracy theory

was never proven and is still a subject of some controversy, despite the South African Margo Commission finding that the crash was an accident. A Soviet delegation that did not participate in the investigation issued a minority report implicating South Africa.

, Botha's government set up a powerful state security apparatus

to "protect" the state against an anticipated upsurge in political violence that the reforms were expected to trigger. The 1980s became a period of considerable political unrest, with the government becoming increasingly dominated by Botha's circle of generals and police chiefs (known as securocrats), who managed the various States of Emergencies.

Botha's years in power were marked also by numerous military interventions in the states bordering South Africa, as well as an extensive military and political campaign to eliminate SWAPO in Namibia

. Within South Africa, meanwhile, vigorous police action and strict enforcement of security legislation resulted in hundreds of arrests and bans, and an effective end to the ANC's sabotage campaign.

The government punished political offenders brutally. 40,000 people were subjected to whipping

as a form of punishment annually. The vast majority had committed political offences and were lashed ten times for their trouble. If convicted of treason, a person could be hanged, and the government executed numerous political offenders in this way.

As the 1980s progressed, more and more anti-apartheid organisations were formed and affiliated with the UDF. Led by the Reverend Allan Boesak

and Albertina Sisulu, the UDF called for the government to abandon its reforms and instead abolish apartheid and eliminate the homelands completely.

, where a burning tyre was placed around the victim's neck.

On 20 July 1985, State President P.W. Botha declared a State of Emergency in 36 magisterial districts. Areas affected were the Eastern Cape

, and the PWV

region ("Pretoria

, Witwatersrand

, Vereeniging"). Three months later the Western Cape

was included as well. An increasing number of organisations were banned or listed (restricted in some way); many individuals had restrictions such as house arrest imposed on them. During this state of emergency about 2,436 people were detained under the Internal Security Act. This act gave police and the military sweeping powers. The government could implement curfews controlling the movement of people. The president could rule by decree without referring to the constitution or to parliament. It became a criminal offence to threaten someone verbally or possess documents that the government perceived to be threatening. It was illegal to advise anyone to stay away from work or oppose the government. It was illegal, too, to disclose the name of anyone arrested under the State of Emergency until the government saw fit to release that name. People could face up to ten years' imprisonment for these offences. Detention without trial became a common feature of the government's reaction to growing civil unrest and by 1988, 30,000 people had been detained. The media was censored, thousands were arrested and many were interrogated and torture

d.

On 12 June 1986, four days before the ten-year anniversary of the Soweto uprising, the state of emergency was extended to cover the whole country. The government amended the Public Security Act, expanding its powers to include the right to declare "unrest" areas, allowing extraordinary measures to crush protests in these areas. Severe censorship of the press became a dominant tactic in the government's strategy and television cameras were banned from entering such areas. The state broadcaster, the South African Broadcasting Corporation

(SABC) provided propaganda in support of the government. Media opposition to the system increased, supported by the growth of a pro-ANC underground press within South Africa.

In 1987, the State of Emergency was extended for another two years. Meanwhile, about 200,000 members of the National Union of Mineworkers commenced the longest strike (three weeks) in South African history. 1988 saw the banning of the activities of the UDF and other anti-apartheid organisations.

Much of the violence in the late 1980s and early 1990s was directed at the government, but a substantial amount was between the residents themselves. Many died in violence between members of Inkatha and the UDF-ANC faction. It was later proven that the government manipulated the situation by supporting one side or the other when it suited it. Government agents assassinated opponents within South Africa and abroad; they undertook cross-border army and air-force attacks on suspected ANC and PAC bases. The ANC and the PAC in return exploded bombs at restaurants, shopping centres and government buildings such as magistrates courts.

The state of emergency continued until 1990, when it was lifted by State President F.W. de Klerk.

second only to that of Japan. Trade with Western countries grew, and investment from the United States, France and Britain poured in. Resistance among blacks had been crushed. Since 1964 Mandela, leader of the African National Congress, had been in prison on Robben Island

just off the coast from Cape Town, and it appeared that South Africa's security forces could handle any resistance to apartheid.

In 1974, resistance to apartheid was encouraged by Portugal

's withdrawal from Mozambique

and Angola

, after the 1974 Carnation Revolution

. South African troops withdrew from Angola in early 1976, failing to prevent the liberation forces from gaining power there, and black students in South Africa celebrated a victory of black liberation over white resistance.

The Mahlabatini Declaration of Faith, signed by Mangosuthu Buthelezi

and Harry Schwarz

in 1974, enshrined the principles of peaceful transition of power and equality for all. Its purpose was to provide a blueprint for the government of South Africa by consent and racial peace in a multi-racial society, stressing opportunity for all, consultation, the federal concept, and a Bill of Rights. It caused a split in the United Party

that ultimately realigned opposition politics in South Africa, with the formation of the Progressive Federal Party

in 1977. It was the first of such agreements by acknowledged black and white political leaders in South Africa.

In 1978 the defence minister of the Nationalist Party, Pieter Willem Botha

, became Prime Minister. Botha's all white regime was worried about the Soviet Union helping revolutionaries in South Africa, and the economy had turned sluggish. The new government noted that it was spending too much money trying to maintain the segregated homelands that had been created for blacks and the homelands were proving to be uneconomical.

Nor was maintaining blacks as a third class working well. The labour of blacks remained vital to the economy, and illegal black labour unions were flourishing. Many blacks remained too poor to make much of a contribution to the economy through their purchasing power – although they were more than 70 percent of the population. Botha's regime was afraid that an antidote was needed to prevent the blacks from being attracted to Communism.

In the 1980s, the anti-apartheid movements in the United States and Europe were gaining support for boycotts against South Africa, for the withdrawal of U.S. firms from South Africa and for the release of Mandela. South Africa was becoming an outlaw in the world community of nations. Investing in South Africa by Americans and others was coming to an end and an active policy of disinvestment

ensued. The then ShellBP used to circumvent the oil embargo on the apartheid regime by buying crude oil from Nigeria and transferring the crude oil from their ship to oil tankers headed for apartheid South Africa. This was done outside Nigeria's territorial waters. When Nigeria found out, Shell BP was nationalised. In retaliation, Margaret Thatcher's government introduced visa requirements for Nigerians visiting the United Kingdom. This was in retaliation for Nigeria refusing to pay any compensation for the nationalisation. Also many South Africans attended schools in Nigeria. Nelson Mandela has himself at several times acknowledged the role of Nigeria in the struggle against apartheid.

In 1983, a new constitution was passed implementing a so-called Tricameral Parliament

, giving coloureds and Indians voting rights and parliamentary representation in separate houses – the House of Assembly (178 members) for whites, the House of Representatives (85 members) for coloureds and the House of Delegates (45 members) for Indians. Each House handled laws pertaining to its racial group's "own affairs", including health, education and other community issues. All laws relating to "general affairs" (matters such as defence, industry, taxation and Black affairs) were handled by a cabinet made up of representatives from all three houses, where the ruling party in the white House of Assembly had an unassailable numerical advantage. Blacks, although making up the majority of the population, were excluded from representation; they remained nominal citizens of their homelands. The first Tricameral elections were largely boycotted by Coloured and Indian voters, amid widespread rioting.

committed to violent revolution, but to appease black opinion and nurture Mandela as a benevolent leader of blacks the government moved Mandela from Robben Island to a prison in a rural area just outside Cape Town, Pollsmoor prison, where prison life was easier. And the government allowed Mandela more visitors, including visits and interviews by foreigners, to let the world know that Mandela was being treated well.

Black homelands were declared nation-states and pass laws were abolished. Also, black labour unions were legitimised, the government recognised the right of blacks to live in urban areas permanently and gave blacks property rights there. Interest was expressed in rescinding the law against interracial marriage and also rescinding the law against sex between the races, which was under ridicule abroad. The spending for black schools increased, to one-seventh of what was spent per white child, up from on one-sixteenth in 1968. At the same time, attention was given to strengthening the effectiveness of the police apparatus.

In January 1985, Botha addressed the government's House of Assembly and stated that the government was willing to release Mandela on condition that Mandela pledge opposition to acts of violence to further political objectives. Mandela's reply was read in public by his daughter Zinzi – his first words distributed publicly since his sentence to prison twenty-one years before. Mandela described violence as the responsibility of the apartheid regime and said that with democracy there would be no need for violence. The crowd listening to the reading of his speech erupted in cheers and chants. This response helped to further elevate Mandela's status in the eyes of those, both internationally and domestically, who opposed apartheid.

Between 1986 and 1988, some petty apartheid laws were repealed. Botha told white South Africans to "adapt or die" and twice he wavered on the eve of what were billed as "rubicon

" announcements of substantial reforms, although on both occasions he backed away from substantial changes. Ironically, these reforms served only to trigger intensified political violence through the remainder of the eighties as more communities and political groups across the country joined the resistance movement. Botha's government stopped short of substantial reforms, such as lifting the ban on the ANC, PAC and SACP and other liberation organisations, releasing political prisoners, or repealing the foundation laws of grand apartheid. The government's stance was that they would not contemplate negotiating until those organisations "renounced violence".

By 1987 the growth of South Africa's economy had dropped to among the lowest rate in the world, and the ban on South African participation in international sporting events was frustrating many whites in South Africa. Examples of African states with black leaders and white minorities existed in Kenya and Zimbabwe. Whispers of South Africa one day having a black President sent more hardline whites into Rightist parties. Mandela was moved to a four-bedroom house of his own, with a swimming pool and shaded by fir trees, on a prison farm just outside Cape Town. He had an unpublicised meeting with Botha, Botha impressing Mandela by walking forward, extending his hand and pouring Mandela's tea. And the two had a friendly discussion, Mandela comparing the African National Congress' rebellion with that of the Afrikaner rebellion, and about everyone being brothers.

A number of clandestine meetings were held between the ANC-in-exile and various sectors of the internal struggle, such as women and educationalists. More overtly, a group of white intellectuals met the ANC in Senegal

for talks.

Early in 1989, Botha suffered a stroke; he was prevailed upon to resign in February 1989. He was succeeded as president later that year by F.W. de Klerk

Early in 1989, Botha suffered a stroke; he was prevailed upon to resign in February 1989. He was succeeded as president later that year by F.W. de Klerk

. Despite his initial reputation as a conservative, De Klerk moved decisively towards negotiations to end the political stalemate in the country. In his opening address to parliament on 2 February 1990, De Klerk announced that he would repeal discriminatory laws and lift the 30-year ban on leading anti-apartheid groups such as the African National Congress

, the Pan Africanist Congress, the South African Communist Party

(SACP) and the United Democratic Front

. The Land Act was brought to an end. De Klerk also made his first public commitment to release jailed ANC leader Nelson Mandela

, to return to press freedom and to suspend the death penalty. Media restrictions were lifted and political prisoners not guilty of common-law crimes were released.

On 11 February 1990, Nelson Mandela was released from Victor Verster Prison

after more than 27 years in prison.

Having been instructed by the UN Security Council to end its long-standing involvement in South-West Africa /Namibia

, and in the face of military stalemate in Southern Angola, and an escalation in the size and cost of the combat with the Cubans, the Angolans, and SWAPO forces and the growing cost of the border war, South Africa negotiated a change of control of this territory; Namibia officially became an independent state on 21 March 1990.

, the first in South Africa with universal suffrage

.

From 1990 to 1996 the legal apparatus of apartheid was abolished. In 1990 negotiations were earnestly begun, with two meetings between the government and the ANC. The purpose of the negotiations was to pave the way for talks towards a peaceful transition of power. These meetings were successful in laying down the preconditions for negotiations – despite the considerable tensions still abounding within the country.

At the first meeting, the NP and ANC discussed the conditions for negotiations to begin. The meeting was held at Groote Schuur

, the President's official residence. They released the Groote Schuur Minute which said that before negotiations commenced political prisoners would be freed and all exiles allowed to return.

There were fears that the change of power in South Africa would be violent. To avoid this, it was essential that a peaceful resolution between all parties be reached. In December 1991, the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) began negotiations on the formation of a multiracial transitional government and a new constitution extending political rights to all groups. CODESA adopted a Declaration of Intent and committed itself to an "undivided South Africa".

Reforms and negotiations to end apartheid led to a backlash among the right-wing white opposition, leading to the Conservative Party

winning a number of by-elections against NP candidates. De Klerk responded by calling a whites-only referendum in March 1992 to decide whether negotiations should continue. A 68-percent majority of white voters gave its support, and the victory instilled in De Klerk and the government a lot more confidence, giving the NP a stronger position in negotiations.

Thus, when negotiations resumed in May 1992, under the tag of CODESA II, stronger demands were made. The ANC and the government could not reach a compromise on how power should be shared during the transition to democracy. The NP wanted to retain a strong position in a transitional government, as well as the power to change decisions made by parliament.

Persistent violence added to the tension during the negotiations. This was due mostly to the intense rivalry between the Inkatha Freedom Party

(IFP) and the ANC and the eruption of some traditional tribal and local rivalrys between the Zulu and Xhosa historical tribal affinities, especially in the Southern Natal provinces. Although Mandela and Buthelezi met to settle their differences, they could not stem the violence. One of the worst cases of ANC-IFP violence was the Boipatong massacre

of 17 June 1992, when 200 IFP militants attacked the Gauteng township of Boipatong, killing 45. Witnesses said that the men had arrived in police vehicles, supporting claims that elements within the police and army contributed to the ongoing violence. Subsequent judicial inquiries found the evidence of the witnesses to be unreliable or discredited, and that there was no evidence of National Party or police involvement in the massacre. When De Klerk tried to visit the scene of the incident, he was initially warmly welcomed in the area. But he was suddenly confronted by a crowd of protesters brandishing stones and placards. The motorcade sped from the scene as police tried to hold back the crowd. Shots were fired by the police, and the PAC stated that three of its supporters had been gunned down.. Nonetheless, the Boipatong massacre offered the ANC a pretext to engage in brinkmanship. Mandela argued that de Klerk, as head of state, was responsible for bringing an end to the bloodshed. He also accused the South African police of inciting the ANC-IFP violence. This formed the basis for ANC's withdrawal from the negoatiations, and the CODESA forum broke down completely at this stage.

The Bisho massacre

on 7 September 1992 brought matters to a head. The Ciskei Defence Force killed 29 people and injured 200 when they opened fire on ANC marchers demanding the reincorporation of the Ciskei homeland

into South Africa. In the aftermath, Mandela and De Klerk agreed to meet to find ways to end the spiralling violence. This led to a resumption of negotiations.

Right-wing violence also added to the hostilities of this period. The assassination of Chris Hani

on 10 April 1993 threatened to plunge the country into chaos. Hani, the popular general secretary of the South African Communist Party

(SACP), was assassinated in 1993 in Dawn Park in Johannesburg

by Janusz Waluś

, an anti-communist Polish

refugee who had close links to the white nationalist Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging

(AWB). Hani enjoyed widespread support beyond his constituency in the SACP and ANC and had been recognised as a potential successor to Mandela; his death brought forth protests throughout the country and across the international community, but ultimately proved a turning point, after which the main parties pushed for a settlement with increased determination. On 25 June 1993, the AWB used an armoured vehicle to crash through the doors

of the Kempton Park World Trade Centre where talks were still going ahead under the Negotiating Council, though this did not derail the process.

In addition to the continuing "black-on-black" violence, there were a number of attacks on white civilians by the PAC's military wing, the Azanian People's Liberation Army

(APLA). The PAC was hoping to strengthen their standing by attracting the support of the angry, impatient youth. In the St James Church massacre

on 25 July 1993, members of the APLA opened fire in a church in Cape Town

, killing 11 members of the congregation and wounding 58.

In 1993, de Klerk

and Mandela

were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

"for their work for the peaceful termination of the apartheid regime, and for laying the foundations for a new democratic South Africa".

Violence persisted right up to the 1994 elections. Lucas Mangope

, leader of the Bophuthatswana homeland

, declared that it would not take part in the elections. It had been decided that, once the temporary constitution had come into effect, the homelands would be incorporated into South Africa, but Mangope did not want this to happen. There were strong protests against his decision, leading to a coup d'état in Bophuthatswana on 10 March which deposed Mangope, despite the intervention of white right-wingers hoping to maintain him in power. Three AWB militants were killed during this intervention, and harrowing images were shown on national television and in newspapers across the world.

Two days before the elections, a car bomb

exploded in Johannesburg, killing nine. The day before the elections, another one went off, injuring thirteen. Finally, though, at midnight on 26–27 April 1994, the old flag was lowered, and the old (now co-official) national anthem Die Stem

("The Call") was sung, followed by the raising of the new rainbow flag

and singing of the other co-official anthem, Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika

("God Bless Africa").

The ANC won 62.65% of the vote, less than the 66.7% that would have allowed it to rewrite the constitution. In the new parliament, 252 of its 400 seats went to members of the African National Congress. The NP captured most of the white and coloured votes and became the official opposition party. As well as deciding the national government, the election decided the provincial governments, and the ANC won in seven of the nine provinces, with the NP winning in the Western Cape

and the IFP in KwaZulu-Natal