History of the United States (1865–1918)

Encyclopedia

The History of the United States (1865–1918) covers Reconstruction, the Gilded Age

, and the Progressive Era

, and includes the rise of industrialization and the resulting surge of immigration in the United States

. This period of rapid economic growth and soaring prosperity in North and West (but not the South) saw the U.S. become the world's dominant economic, industrial and agricultural power. The average annual income (after inflation) of nonfarm workers grew by 75% from 1865 to 1900, and then grew another 33% by 1918.

With a decisive victory in 1865 over Southern secessionists in the Civil War

, the United States became a united and powerful nation with a strong national government. Reconstruction brought the end of slavery and citizenship for the former slaves, but their political power was later rolled back and they became second-class citizens under a "Jim Crow" system of segregation

. Politically the nation in the Third Party System

and Fourth Party System

was mostly dominated by Republicans (except for two Democratic presidents). After 1900 the Progressive Era

brought political and social reforms, such as new roles for education and a higher status for women, and modernized many areas of government and society. The progressives worked through new middle class organizations to fight against the corruption and behind-the-scenes power of entrenched state party organizations and big city machines. They demanded --and obtained in 1920--votes for women and the prohibition of alcohol

.

In an unprecedented wave of European immigration

, 27.5 million new arrivals between 1865 and 1918 provided the labor base for the expansion of industry and agriculture and provided the population base for most of fast-growing urban America.

By the late nineteenth century, the United States had become a leading global industrial power, building on new technologies (such as the telegraph

and steel

), an expanding railroad network

, and abundant natural resources

such as coal, timber, oil and farmland, to usher in the Second Industrial Revolution

.

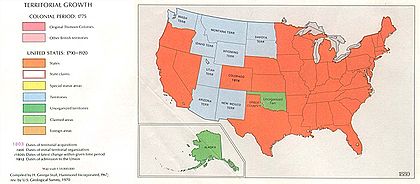

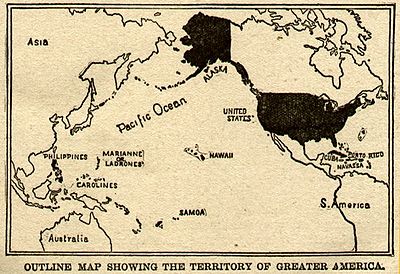

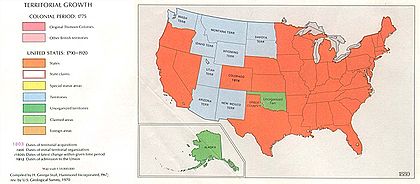

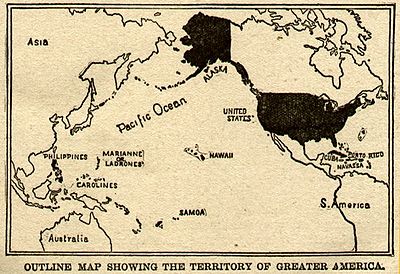

There were two important wars. The US easily defeated Spain in 1898

, which unexpectedly brought a small empire. Cuba quickly was given independence, and eventually also the Philippines in 1946. Puerto Rico

and (and some smaller islands) became permanent possessions, as did Alaska

, added by purchase in 1867, and the independent Republic of Hawaii

, was annexed

to the United States in 1898.

The United States tried and failed to broker a peace settlement for World War I

, then entered the war to oppose German militarism. After a slow mobilization the U.S. produced a decisive Allied victory thanks to American financial, agricultural, industrial and military strength.

of the Confederacy

. Before his assassination in April 1865, Abraham Lincoln

had announced moderate plans for reconstruction to reintegrate the former Confederates as fast as possible. Lincoln set up the Freedman's Bureau in March 1865, aiding former slaves with education, health care, and employment. The final abolition of slavery was achieved by the Thirteenth Amendment

, ratified in December 1865. However, he was opposed by Radical Republicans who feared the former Confederates secretly believed in slavery and Confederate nationalism, and tried to impose restrictions that would prevent most ex-rebels from voting or holding office. The Radicals were opposed by President Andrew Johnson, but the Radicals won the critical election of 1866, and overcame Johnson's vetoes. Indeed, they impeached him and almost removed him from office in 1868. Meanwhile, they gave the Freedmen new constitutional and federal legal protections, most of which were lost after conservative white southerners regained control of all Southern states by 1877.

The Radical reconstruction plan went into effect in 1867 under the supervision of the Army, allowing a Republican coalition of Freedmen, Scalawags (local whites) and Carpetbaggers (recent arrivals) took control of Southern state governments and ratified the Fourteenth Amendment

, giving enormous new powers to the federal courts to deal with justice at the state level. These governments borrowed heavily to build railroads and public schools, running up the tax rates in the face of increasingly fierce opposition that drove most of the Scalawags into the Democratic Party. President Ulysses S. Grant

enforced civil rights protection for African Americans in South Carolina, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The Fifteenth Amendment

was ratified in 1870 giving African Americans the right to vote in elections. The Civil Rights Act of 1875

was passed to give people the right to public facilities regardless of race or previous servitude.

Reconstruction ended at different times in each state, the last in 1877, when Republican Rutherford B. Hayes

won the contentious presidential election of 1876 over his opponent, Samuel J. Tilden

. To deal with disputed electoral votes, Congress set up an Electoral Commission. It awarded the disputed votes to Hayes. The white South accepted the "Compromise of 1877

" knowing that Hayes proposed to end Army control over the remaining three state governments in Republican hands. White Northerners accepted that the Civil War was over and that Southern whites posed no threat to the nation.

The end of Reconstruction marked the end of the brief period of civil rights and civil liberties for African Americans in the South, where most lived. Reconstruction caused lasting bitterness among white Southerners toward the federal government, and helped create the "Solid South," which typically voted for Democrats for local, state, and national office. White supremacists created a segregated society through "Jim Crow Laws

" that made blacks second-class citizens with very little political power or public voice. The white elites ("Redeemers

", the southern wing of the "Bourbon Democrats") were in firm political and economic control until the rise of the Populist movement in the 1890s. Local law enforcement was weak in rural areas, allowing outraged mobs to use lynching

to redress supposed crimes committed by blacks

with the indigenous population of the West

. The government insisted the Indians remain on assigned reservations, and used force to keep them there. The violence petered out in the 1880s and practically ceased after 1890. By 1880 the buffalo herds

, a foundation for the hunting economy, had disappeared.

Indians had the choice of living on reservations, where food, supplies, education and medical care was provided by the federal government, or living on their own in society and earning wages, typically as a cowboy on a ranch, or manual worker in town. Reformers wanted to give as many Indians as possible the opportunity to own and operate their own farms and ranches, and the issue was how to give individual Indians land owned by the tribe. To assimilate the Indians into American society, reformers set up training programs and schools, such as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School

in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, that produced many prominent Indian leaders. The anti-assimilation traditionalists on the reservations, however, resisted integration. The reformers decided the solution was to allow Indians still on reservations to own land as individuals. In 1887, the Dawes Act

proposed to divide tribal land and parcel out 160 acres (0.65 km²) of land to each head of a family. Such allotments were to be held in trust by the government for 25 years, after which time the owner won full title to the land (so that it could be sold or mortgaged), as well as full legal citizenship. Lands not thus distributed, however, were offered for sale to settlers. This policy eventually resulted to the Indian loss, by seizure and sale, of almost half of their tribal lands. It also destroyed much of the communal organization of the tribes, further disrupting the traditional culture of the surviving indigenous population. The Dawes Act was an effort to integrate Indians into the mainstream; the majority accepted integration and were absorbed into American society, leaving a trace of Indian ancestry in millions of American families. Those who refused to assimilate remained in poverty on the reservations, supported by Federal food, medicine and schooling. In 1934, U.S. policy was reversed again by the Indian Reorganization Act

which attempted to protect tribal and communal life on the reservations.

all fostered the cheap extraction of energy, fast transport, and the availability of capital that powered this Second Industrial Revolution

. The average annual income (after inflation) of nonfarm workers grew by 75% from 1865 to 1900, and then grew another 33% by 1918.

Where the First Industrial Revolution

shifted production from artisans to factories, the Second Industrial Revolution pioneered an expansion in organization, coordination, and the scale of industry

, spurred on by technology and transportation advancements. Railroads opened the West, creating farms, towns and markets where none had existed. The First Transcontinental Railroad

, built by nationally oriented entrepreneurs with British money and Irish

and Chinese

labor, provided access to previously remote expanses of land. Railway construction boosted opportunities for capital, credit, and would-be farmers.

New technologies in iron and steel manufacturing, such as the Bessemer process

and open-hearth furnace, combined with similar innovations in chemistry and other sciences to vastly improve productivity. New communication tools, such as the telegraph

and telephone

allowed corporate managers to coordinate across great distances. Innovations also occurred in how work was organized, typified by Frederick Winslow Taylor

's ideas of scientific management

.

To finance the larger-scale enterprises required during this era, the corporation emerged as the dominant form of business organization. Corporations expanded by merging, creating single firms out of competing firms known as "trusts

" (a form of monopoly). High tariffs sheltered U.S. factories and workers from foreign competition, especially in the woolen industry. Federal railroad land grants enriched investors, farmers and railroad workers, and created hundreds of towns and cities. Business often went to court to stop labor from organizing into unions

or from organizing strikes.

Powerful industrialists, such as Andrew Carnegie

, John D. Rockefeller

and Jay Gould

, known collectively by their enemies as "robber barons

", held great wealth and power. In a context of cutthroat competition for wealth accumulation, the skilled labor of artisans gave way to well-paid skilled workers and engineers, as the nation deepened its technological base. Meanwhile, a steady stream of immigrants encouraged the availability of cheap labor, especially in mining

and manufacturing

.

A dramatic expansion in farming took place. The number of farms tripled from 2.0 million in 1860 to 6.0 million in 1905. The number of people living on farms grew from about 10 million in 1860 to 22 million in 1880 to 31 million in 1905. The value of farms soared from $8.0 billion in 1860 to $30 billion in 1906.

The federal government issued 160 acres (64.7 ha) tracts virtually free to settlers under the Homestead Act

of 1862. Even larger numbers purchased lands at very low interest from the new railroads, which were trying to create markets. The railroads advertised heavily in Europe and brought over, at low fares, hundreds of thousands of farmers from Germany, Scandinavia and Britain.

Despite their remarkable progress and general prosperity, 19th-century U.S. farmers experienced recurring cycles of hardship, caused primarily by falling world prices for cotton and wheat.

Along with the mechanical improvements which greatly increased yield per unit area, the amount of land under cultivation grew rapidly throughout the second half of the century, as the railroads opened up new areas of the West for settlement. A similar expansion of agricultural lands in other countries, such as Canada, Argentina, and Australia, created problems of oversupply and low prices in the international market, where half of American wheat was sold. The wheat farmers enjoyed abundant output and good years from 1876 to 1881 when bad European harvests kept the world price high. They then suffered from a slump in the 1880s when conditions in Europe improved. The farther west the settlers went, the more dependent they became on the monopolistic railroads to move their goods to market. Wheat farmers blamed local grain elevator owners (who purchased their crop), railroads and eastern bankers for the low prices.

In the South, Reconstruction brought major changes in agricultural practices. The most significant of these was sharecropping

, where tenant farmers "shared" up to half of their crop with the landowners, in exchange for seed and essential supplies. About 80% of the African American farmers and 40% of its white ones lived under this system following the Civil War. Most sharecroppers were locked in a cycle of debt, from which the only hope of escape was increased planting. This led to the over-production of cotton and tobacco (and thus to declining prices and decreased income), exhaustion of the soil, and increased poverty among both the landowners and tenants.

The first organized effort to address general agricultural problems was the Grange movement

The first organized effort to address general agricultural problems was the Grange movement

. Launched in 1867, by employees of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Granges focused initially on social activities to counter the isolation most farm families experienced. Women's participation was actively encouraged. Spurred by the Panic of 1873, the Grange soon grew to 20,000 chapters and 1.5 million members. The Granges set up their own marketing systems, stores, processing plants, factories and cooperative

s. Most went bankrupt. The movement also enjoyed some political success during the 1870s. A few Midwestern states passed "Granger Laws

", limiting railroad and warehouse fees.

and 1893–97

, with low prices for farm goods and heavy unemployment in factories and mines. Full prosperity returned in 1897 and continued (with minor dips) to 1920.

The pool of unskilled labor was constantly growing, as unprecedented numbers of immigrants—27.5 million between 1865 and 1918 —entered the U.S. Most were young men eager for work. The rapid growth of engineering and the need to master the new technology created a heavy demand for engineers, technicians and skilled workers. Before 1874, when Massachusetts

passed the nation's first legislation limiting the number of hours women and child factory workers could perform to 10 hours a day, virtually no labor legislation existed in the country. Child labor reached a peak about 1900 then declined (except in Southern textile mills) as compulsory education laws kept children in school. It was finally ended in the 1930s.

in 1869. Originally a secret, ritualistic society organized by Philadelphia garment workers, it was open to all workers, including African Americans, women and farmers. The Knights grew slowly until they succeeded in facing down the great railroad baron, Jay Gould

, in an 1885 strike. Within a year, they added 500,000 workers to their rolls, far more than the thin leadership structure of the Knights could handle.

The Knights of Labor soon fell into decline, and their place in the labor movement was gradually taken by the American Federation of Labor

(AFL). Rather than open its membership to all, the AFL, under former cigar-makers union official Samuel Gompers

, focused on skilled workers. His objectives were "pure and simple": increasing wages, reducing hours and improving working conditions. As such, Gompers helped turn the labor movement away from the socialist views earlier labor leaders had espoused. The AFL would gradually become a respected organization in the U.S., although it would have nothing to do with unskilled laborers.

Non-skilled workers' goals—and the unwillingness of business owners to grant them—resulted in some of the most violent labor conflicts in the nation's history. The first of these was the Great Railroad Strike in 1877, when rail workers across the nation went on strike in response to a 10-percent pay cut by owners. Attempts to break the strike led to bloody uprisings in several cities. The Haymarket Riot took place in 1886, when an anarchist apparently threw a bomb at police dispersing a strike rally at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company in Chicago. The killing of policemen greatly embarrassed the Knights of Labor, which was not involved with the bomb but which took much of the blame.

In the riots

of 1892 at Carnegie's steel works in Homestead, Pennsylvania

, a group of 300 Pinkerton detectives

, whom the company had hired to break a bitter strike by the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers, were fired upon by strikers and 10 were killed. As a result, the National Guard

was called in to guard the plant; non-union workers were hired and the strike broken. The Homestead plant completely barred unions until 1937.

Two years later, wage cuts at the Pullman Palace Car Company

, just outside Chicago, led to a strike, which, with the support of the American Railway Union

, soon brought the nation's railway industry to a halt. The shutdown of rail traffic meant the virtual shutdown of the entire national economy, and President Grover Cleveland

acted vigorously. He secured injunctions in federal court, which Debs and the other strike leaders ignored. Cleveland then sent in the Army to stop the rioting and get the trains moving. The strike collapsed, as did the ARU

The most militant working class organization of the 1905-1920 era was the Industrial Workers of the World

(IWW). The "Wobblies" as they were commonly known, gained particular prominence from their incendiary and revolutionary rhetoric. Openly calling for class warfare

, the Wobblies gained many adherents after they won a difficult 1912 textile strike

(commonly known as the "Bread and Roses

" strike) in Lawrence

, Massachusetts

. They proved ineffective in managing peaceful labor relations and members dropped away. The IWW strongly opposed the 1917-18 war effort and was shut down by the federal government (with a tiny remnant still in existence).

floated on the surface of the newly industrialized economy of the Second Industrial Revolution. It was further fueled by a period of wealth transfer that catalyzed dramatic social changes. It created for the first time a class of the super-rich "captains of industry", the "Robber Barons" whose network of business, social and family connections ruled a largely White Anglo-Saxon Protestant

social world that possessed clearly defined boundaries. The term "Gilded Age" was coined by Mark Twain

and Charles Dudley Warner

in their 1873 book, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today

, employing the ironic difference between a "gilded" and a Golden Age

.

With the end of Reconstruction, there were few major political issues at stake and the 1880 presidential election was the quietest in a long time. James Garfield, the Republican candidate, won a very close election, but a few months into his administration was shot by a disgruntled public office seeker. Garfield was succeeded by his VP Chester Arthur.

Reformers, especially the "Mugwumps" complained that powerful parties made for corruption during the Gilded Age or "Third Party System

". Voter enthusiasm and turnout during the period 1872-1892 was very high, often reaching practically all men. The major issues involved modernization, money, railroads, corruption, and prohibition. National elections, and many state elections, were very close. The 1884 presidential election saw a mudslinging campaign in which Republican James G. Blaine

was defeated by Democrat Grover Cleveland

, a reformer. During Cleveland's presidency, he pushed to have congress cut tariff duties. He also expanded civil services and vetoed many private pension bills. Many people were worried that these issues would hurt his chances in the 1888 election. When they expressed these concerns to Cleveland, he said "What is the use of being elected or reelected, unless you stand for something?"

The dominant social class of the Northeast possessed the confidence to proclaim an "American Renaissance

", which could be identified in the rush of new public institutions that marked the period—hospitals, museums, colleges, opera houses, libraries, orchestras— and by the Beaux-Arts architectural idiom in which they splendidly stood forth, after Chicago hosted the World's Columbian Exposition

of 1893.

, and from 1892, through the immigration station on Ellis Island

, but various ethnic groups settled in different locations. New York and other large cities of the East Coast

became home to large Jewish, Irish, and Italian populations, while many Germans and Central Europe

ans moved to the Midwest

, obtaining jobs in industry and mining. At the same time, about one million French Canadians migrated from Quebec

to New England

.

Immigrants were pushed out of their homelands by poverty or religious threats, and pulled to America by jobs, farmland and kin connections. They found economic opportunity at factories, mines and construction sites, and found farm opportunities in the Plains states.

While most immigrants were welcomed, Asians were not. Many Chinese had been brought to the west coast to construct railroads, but unlike European immigrants, they were seen as being part of an entirely alien culture. After intense anti-Chinese agitation in California and the west, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act

in 1882. An informal agreement in 1907, the Gentlemen's Agreement, stopped Japanese immigration.

Some immigrants stayed temporarily in the U.S. then returned home, often with savings that made them relatively prosperous. Most, however, permanently left their native lands and stayed in hope of finding a better life in the New World

. This desire for freedom and prosperity led to the famous term, the American Dream

.

was a period of renewal in evangelical Protestantism from the late 1850s to the 1900s. It affected pietistic Protestant denominations and had a strong sense of social activism. It gathered strength from the postmillennial theology that the Second Coming

of Christ would come after mankind had reformed the entire earth. A major component was the Social Gospel

Movement, which applied Christianity to social issues and gained its force from the Awakening, as did the worldwide missionary movement. New groupings emerged, such as the Holiness movement

and Nazarene

movements, and Christian Science

.

At the same time, the Catholic Church grew rapidly, with a base in the German, Irish, Polish, and Italian immigrant communities, and a leadership drawn from the Irish. The Catholics were largely working class and concentrated in the industrial cities and mining towns, where they built churches, parochial schools, and charitable institutions, as well as colleges.

The Jewish community

grew rapidly, especially from the new arrivals from Eastern Europe who settled chiefly in New York City. They avoided the Reform synagogues of the older German Jews and instead formed Orthodox and Conservative synagogues.

Starting in the end of the 1870s, African Americans lost many of the civil rights obtained during Reconstruction and became increasingly subject to racial discrimination. Increased racist

Starting in the end of the 1870s, African Americans lost many of the civil rights obtained during Reconstruction and became increasingly subject to racial discrimination. Increased racist

violence, including lynchings

and race riot

s, lead to a strong deterioration of living conditions of African Americans in the Southern states. Jim Crow laws

were established after the Compromise of 1877

. Many decided to flee for the Midwest as early as 1879, an exile which was intensified during the Great Migration

that began before World War I.

In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court effectively upheld the Jim Crow system of racial segregation

by its "separate but equal

" doctrine.

D. W. Griffith

's The Birth of a Nation

(1915), the first great American film, made heroes of the KKK in Reconstruction.

—of the railroads; currency inflation

to provide debt relief; the lowering of the tariff; and the establishment of government-owned storehouses and low-interest lending facilities. These were known as the Ocala Demands

.

During the late 1880s, a series of droughts devastated the West. Western Kansas

lost half its population during a four-year span. To make matters worse, the McKinley Tariff

of 1890 was one of the highest the country had ever seen. This was detrimental to American farmers, as it drove up the prices of farm equipment.

By 1890, the level of agrarian distress was at an all-time high. Mary Elizabeth Lease

, a noted populist writer and agitator, told farmers that they needed to "raise less corn and more hell". Working with sympathetic Democrats

in the South and small third parties in the West, the Farmer's Alliance made a push for political power. From these elements, a new political party, known as the Populist Party

, emerged. The elections of 1890 brought the new party into coalitions that controlled parts of state government in a dozen Southern

and Western

states and sent a score of Populist senators and representatives to Congress.

Its first convention was in 1892, when delegates from farm, labor and reform organizations met in Omaha, Nebraska

, determined at last to make their mark on a U.S. political system that they viewed as hopelessly corrupted by the monied interests of the industrial and commercial trusts.

The pragmatic portion of the Populist platform focused on issues of land, railroads and money, including the unlimited coinage of silver. The Populists showed impressive strength in the West and South in the 1892 elections

, and their candidate for President polled more than a million votes. It was the currency question, however, pitting advocates of silver against those who favored gold, that soon overshadowed all other issues. Agrarian spokesmen in the West and South demanded a return to the unlimited coinage of silver. Convinced that their troubles stemmed from a shortage of money in circulation, they argued that increasing the volume of money would indirectly raise prices for farm products and drive up industrial wages, thus allowing debts to be paid with inflated dollars.

Conservative groups and the financial classes, on the other hand, believed that such a policy would be disastrous, and they insisted that inflation, once begun, could not be stopped. Railroad bonds, the most important financial instrument of the time, were payable in gold. If fares and freight rates were set in half-price silver dollars, railroads would go bankrupt in weeks, throwing hundreds of thousands of men out of work and destroying the industrial economy. Only the gold standard

, they said, offered stability.

The financial Panic of 1893

heightened the tension of this debate. Bank failures

abounded in the South and Midwest

; unemployment soared and crop prices fell badly. The crisis, and President Cleveland's inability to solve it, nearly broke the Democratic Party.

The Democratic Party, which supported silver and free trade, absorbed the remnants of the Populist movement as the presidential elections of 1896

neared. The Democratic convention that year was witness to one of the most famous speeches in U.S. political history. Pleading with the convention not to "crucify mankind on a cross of gold", William Jennings Bryan

, the young Nebraska

n champion of silver, won the Democrats' presidential nomination. The remaining Populists also endorsed Bryan, hoping to retain some influence by having a voice inside the Bryan movement. Despite carrying the South and all the West except California

and Oregon

, Bryan lost the more populated, industrial North and East—and the election—to the Republican William McKinley

with his campaign slogan "A Full Dinner Pail".

The following year, the country's finances began to improve, mostly from restored business confidence. Silverites—who did not realize that most transactions were handled by bank checks, not sacks of gold—believed the new prosperity was spurred by the discovery of gold in the Yukon

. In 1898, the Spanish-American War

drew the nation's attention further away from Populist issues. If the movement was dead, however, its ideas were not. Once the Populists supported an idea, it became so tainted that the vast majority of American politicians rejected it; only years later, after the taint had been forgotten, was it possible to achieve Populist reforms, such as the direct popular election of Senators

.

The women's suffrage movement began with the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention

The women's suffrage movement began with the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention

; many of the activists became politically aware during the abolitionist movement. The movement reorganized after the Civil War, gaining experience campaigners, many of who had worked for prohibition in the Women's Christian Temperance Union. By the end of the 19th century a few western states had granted women full voting rights, though women had made significant legal victories, gaining rights in areas such as property and child custody.

Around 1912, the movement, which had grown sluggish, began to reawaken. This put an emphasis on its demands for equality and arguing that the corruption of American politics demanded purification by women because men could no longer do their job. Protests became increasingly common as suffragette

Alice Paul

led parades through the capitol and major cities. Paul split from the large National American Woman Suffrage Association

(NAWSA), which favored a more moderate approach and supported the Democratic Party and Woodrow Wilson, led by Carrie Chapman Catt

, and formed the more militant National Woman's Party

. Suffragists were arrested during their "Silent Sentinels

" pickets at the White House, the first time such a tactic was used, and were taken as political prisoner

s.

Finally, the suffragettes were ordered released from prison, and Wilson urged Congress to pass a Constitutional amendment enfranchising women. The old anti-suffragist argument that only men could fight a war, and therefore only men deserved the franchise, was refuted by the enthusiastic participation of tens of thousands of American women on the home front in World War I. Across the world, grateful nations gave women the right to vote. Furthermore, most of the Western states had already given women the right to vote in state and national elections, and the representatives from those states, including the first voting woman Jeannette Rankin

of Montana, demonstrated that Women's Suffrage was a success. The main resistance came from the south, where white leaders were worried about the threat of black women voting. Nevertheless Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment

in 1919. It became constitutional law on August 26, 1920, after ratification by the 36th required state.

, who had risen to national prominence six years earlier with the passage of the McKinley Tariff

of 1890, a high tariff was passed in 1897 and a decade of rapid economic growth and prosperity ensued, building national self-confidence.

Spain had once controlled a vast colonial empire, but by the second half of the 19th century only Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and some African possessions remained. The Cubans had been in a state of rebellion since the 1870s, and American newspapers, particularly New York City papers of William Randolph Hearst

Spain had once controlled a vast colonial empire, but by the second half of the 19th century only Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and some African possessions remained. The Cubans had been in a state of rebellion since the 1870s, and American newspapers, particularly New York City papers of William Randolph Hearst

and Joseph Pulitzer

, printed sensationalized "Yellow Journalism

" stories about Spanish atrocities in Cuba. However, these lurid stories reached only a small fraction of voters; most read sober accounts of Spanish atrocities, and they called for intervention. On February 15, 1898, the battleship USS Maine

exploded in Havana Harbor. Although it was unclear precisely what caused the blast, many Americans believed it to be the work of a Spanish mine, an attitude encouraged by the yellow journalism

of Hearst and Pulitzer. The military was rapidly mobilized as the U.S. prepared to intervene in the Cuban revolt. It was made clear that no attempt at annexation of Cuba would be made and that the island's independence would be guaranteed. Spain considered this a wanton intervention in its internal affairs and severed diplomatic relations. War was declared on April 25.

The Spanish were quickly defeated, and Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders gained fame in Cuba. Meanwhile, Commodore George Dewey

's fleet crushed the Spanish in the faraway Philippines. Spain capitulated, ending the three-month long war and recognizing Cuba's independence. Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were ceded to the United States.

Although U.S. capital investments within the Philippines and Puerto Rico were small, some politicians hoped they would be strategic outposts for expanding trade with Latin America and Asia, particularly China. That never happened and after 1903 American attention turned to the Panama Canal

as the key to opening new trade routes. The Spanish-American War thus began the active, globally oriented American foreign policy that continues to the present day.

, which ended the Spanish-American War

. However, Philippine revolutionaries

led by Emilio Aguinaldo

declared independence and in 1899 began fighting the U.S. troops. The Philippine-American War

ended in 1901 after Aguinaldo was captured and swore allegiance to the U.S. Likewise the other insurgents accepted American rule and peace prevailed, except in some remote islands under Muslim control. Roosevelt continued the McKinley policies of removing the Catholic friars (with compensation to the Pope), upgrading the infrastructure, introducing public health programs, and launching a program of economic and social modernization. The enthusiasm shown in 1898-99 for colonies cooled off, and Roosevelt saw the islands as "our heel of Achilles." He told Taft in 1907, "I should be glad to see the islands made independent, with perhaps some kind of international guarantee for the preservation of order, or with some warning on our part that if they did not keep order we would have to interfere again." By then the President and his foreign policy advisers turned away from Asian issues to concentrate on Latin America, and Roosevelt redirected Philippine policy to prepare the islands to become the first Western colony in Asia to achieve self-government. The Filipinos fought side by side with the Americans when the Japanese invaded in 1941, and aided the American re-conquest of the islands in 1944-45. Independence came in 1946

; public opinion (overruling McKinley) led to the short, successful Spanish-American War

in 1898. The U.S. permanently took over Puerto Rico, and temporarily held Cuba. Attention increasingly focused on the Caribbean as the rapid growth of the Pacific states, especially California, revealed the need for a canal across to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Plans for one in Nicaragua fell through but under Roosevelt's leadership the U.S. built a canal through Panama, after finding a public health solution to the deadly disease environment. The Panama Canal

opened in 1914.

In 1904, Roosevelt announced his "Corollary

" to the Monroe Doctrine

, stating that the United States would intervene in cases where Latin America

n governments prove incapable or unstable in the interest of bringing democracy and financial stability to them. The U.S. made numerous interventions, mostly to stabilize the shaky governments and permit the nations to develop their economies. The intervention policy ended in the 1930s and was replaced by the Good Neighbor policy.

In 1909, Nicaraguan President José Santos Zelaya

resigned after the triumph of U.S.-backed rebels. This was followed up by the 1912-1933 U.S. occupation of Nicaragua.

The U.S. military occupation of Haiti

, in 1915, followed the mob execution of Haiti's leader but even more important was the threat of a possible German takeover of the island. Germans controlled 80% of the economy by 1914 and they were bankrolling revolutions that kept the country in political turmoil. The conquest resulted in a 19-year-long United States occupation of Haiti (1915-1934)

. Haiti was an exotic locale that suggested black racial themes to numerous American writers including Eugene O'Neill

, James Weldon Johnson

, Langston Hughes

, Zora Neale Hurston

and Orson Welles

.

Limited American intervention occurred in Mexico as that country fell into a long period of anarchy and civil war starting in 1910. In April 1914, U.S. troops occupied the Mexican port of Veracruz following the Tampico Incident; the reason for the intervention was Woodrow Wilson's desire to overthrow the Mexican dictator Victoriano Huerta

. In March 1916, Pancho Villa

led 1,500 Mexican raiders in a cross-border attack against Columbus, New Mexico

, attacked a U.S. Cavalry detachment, seized 100 horses and mules, burned the town, and killed 17 of its residents. President Woodrow Wilson responded by sending 12,000 troops, under Gen. John J. Pershing

, into Mexico to pursue Villa. The Pancho Villa Expedition

to capture Villa failed in its objectives and was withdrawn in January 1917

In 1916, the U.S. occupied the Dominican Republic

.

A new spirit of the times, known as "Progressivism", arose in the 1890s and into the 1920s (although some historians date the ending with the World War I).

The presidential election of 1900 gave the U.S. a chance to pass judgment on the McKinley

Administration, especially its foreign policy. Meeting at Philadelphia, the Republicans expressed jubilation over the successful outcome of the war with Spain, the restoration of prosperity, and the effort to obtain new markets through the Open Door Policy

. The 1900 election was mostly a repeat of 1896 except for imperialism being added as a new issue (Hawaii had been annexed in 1898). William Jennings Bryan

added anti-imperialism to his tired-out free silver rhetoric, but he was defeated in the face of peace, prosperity and national optimism.

President McKinley was enjoying great popularity as he began his second term, but it would be cut short. In September 1901, while attending an exposition in Buffalo, New York

, McKinley was shot by an anarchist. He was the third President to be assassinated, all since the Civil War. Vice President

Theodore Roosevelt

assumed the presidency.

Political corruption was a central issue, which reformers hoped to solve through civil service reforms at the national, state and local level, replacing political hacks with professionals. The 1883 Civil Service Reform Act

(or Pendleton Act), which placed most federal employees on the merit system

and marked the end of the so-called "spoils system

", permitted the professionalization and rationalization of the federal administration. However, local and municipal government remained in the hands of often-corrupt politicians, political machine

s and their local "bosses". Henceforth, the spoils system survived much longer in many states, counties and municipalities, such as the Tammany Hall

ring, which survived well into the 1930s when New York City reformed its own civil service. Illinois modernized its bureaucracy in 1917 under Frank Lowden, but Chicago held out against civil service reform until the 1970s.

Many self-styled progressives saw their work as a crusade against urban political bosses and corrupt "robber barons". There were increased demands for effective regulation of business, a revived commitment to public service, and an expansion of the scope of government to ensure the welfare and interests of the country as the groups pressing these demands saw fit. Almost all the notable figures of the period, whether in politics, philosophy, scholarship or literature, were connected at least in part with the reform movement.

Trenchant articles dealing with trusts, high finance, impure foods and abusive railroad practices began to appear in the daily newspapers and in such popular magazines as McClure's

and Collier's. Their authors, such as the journalist Ida M. Tarbell

, who crusaded against the Standard Oil Trust

, became known as "Muckraker

s". In his novel, The Jungle

, Upton Sinclair

exposed unsanitary conditions in the Chicago meat packing houses and the grip of the beef trust on the nation's meat supply.

The hammering impact of Progressive Era writers bolstered aims of certain sectors of the population, especially a middle class

caught between political machines and big corporations, to take political action. Many states enacted laws to improve the conditions under which people lived and worked. At the urging of such prominent social critics as Jane Addams

, child labor laws

were strengthened and new ones adopted, raising age limits, shortening work hours, restricting night work and requiring school attendance. By the early 20th century, most of the larger cities and more than half the states had established an eight-hour day

on public works

. Equally important were the Workers' Compensation

Laws, which made employers legally responsible for injuries sustained by employees at work. New revenue laws were also enacted, which, by taxing inheritances

, laid the groundwork for the contemporary Federal income tax.

", and initiated a policy of increased Federal supervision in the enforcement of antitrust laws. Later, extension of government supervision over the railroads prompted the passage of major regulatory bills. One of the bills made published rates the lawful standard, and shippers equally liable with railroads for rebates.

Following TR's landslide victory in the 1904 election he called for still more drastic railroad regulation, and in June 1906, Congress passed the Hepburn Act

. This gave the Interstate Commerce Commission

real authority in regulating rates, extended the jurisdiction of the commission, and forced the railroads to surrender their interlocking interests in steamship lines and coal companies. Roosevelt held many meetings, and opened public hearings, in a successful effort to find a compromise for the Coal Strike of 1902

, which threatened the fuel supplies of urban America. Meanwhile, Congress had created a new Cabinet Department of Commerce and Labor.

Conservation of the nation's natural resources and beautiful places was a very high priority for Roosevelt, and he raised the national visibility of the issue. The President called for a far-reaching and integrated program of conservation, reclamation and irrigation as early as 1901 in his first annual message to Congress. Whereas his predecessors had set aside 46 million acres (188,000 km²) of timberland for preservation and parks, Roosevelt increased the area to 146 million acres (592,000 km²) and began systematic efforts to prevent forest fires and to retimber denuded tracts. His appointment of his friend Gifford Pinchot

Conservation of the nation's natural resources and beautiful places was a very high priority for Roosevelt, and he raised the national visibility of the issue. The President called for a far-reaching and integrated program of conservation, reclamation and irrigation as early as 1901 in his first annual message to Congress. Whereas his predecessors had set aside 46 million acres (188,000 km²) of timberland for preservation and parks, Roosevelt increased the area to 146 million acres (592,000 km²) and began systematic efforts to prevent forest fires and to retimber denuded tracts. His appointment of his friend Gifford Pinchot

as chief forester resulted in vigorous new scientific management of public lands. TR added 50 wildlife refuges, 5 new national parks, and initiated the system of designating National Monuments, such as the Devils Tower National Monument

.

. On the Democratic side, William Jennings Bryan ran for a third time, but managed to carry only the South. Taft, a former judge, first colonial governor of the U.S.-held Philippines and administrator of the Panama Canal, made some progress with his Dollar Diplomacy

.

Taft continued the prosecution of trusts, further strengthened the Interstate Commerce Commission, established a postal savings bank and a parcel post system, expanded the civil service, and sponsored the enactment of two amendments to the United States Constitution

. The 16th Amendment authorized a federal income tax, while the 17th Amendment, ratified in 1913, mandated the direct election of U.S. Senators by the people, replacing the prior system established in the original Constitution, in which they were selected by state legislatures.

Yet balanced against these achievements were: Taft's acceptance of a tariff with protective schedules that outraged progressive opinion; his opposition to the entry of the state of Arizona

into the Union because of its progressive constitution; and his growing reliance on the conservative

wing of his party. By 1910, the Republican Party was divided, and an overwhelming vote swept the Democrats

back into control of Congress.

, the Democratic, progressive governor of the state of New Jersey

, campaigned against Taft, the Republican candidate, and against Roosevelt who was appalled by his successor's policies and thus broke his earlier pledge to not run for a third term. As the Republicans would not nominate him, he ran as a third-party Progressive candidate, but the ticket became widely known as the Bull Moose Party. The election was mainly a contest between Roosevelt and Wilson, Taft receiving little attention and carrying just eight electoral votes.

Wilson, in a spirited campaign, defeated both rivals. Under his leadership, the new Congress enacted one of the most notable legislative programs in American history. Its first task was tariff revision. "The tariff duties must be altered," Wilson said. "We must abolish everything that bears any semblance of privilege." The Underwood Tariff in 1913 provided substantial rate reductions on imported raw materials and foodstuffs, cotton and woolen goods, iron and steel, and removed the duties from more than a hundred other items. Although the act retained many protective features, it was a genuine attempt to lower the cost of living for American workers.

The second item on the Democratic program was a reorganization of the banking and currency system. "Control," said Wilson, "must be public, not private, must be vested in the government itself, so that the banks may be the instruments, not the masters, of business and of individual enterprise and initiative."

Passage of the Federal Reserve Act

of 1913 was one of Wilson's most enduring legislative accomplishments, for he successfully developed negotiated a compromise between Wall Street, and the agrarians. The plan built on ideas developed by Senator Nelson Aldrich, who discovered the European nations had more efficient central banks that helped their internal business and international trade. The new organization divided the country into 12 districts, with a Federal Reserve Bank in each, all supervised by a Federal Reserve Board. These banks were owned by local banks and served as depositories for the cash reserves of member banks. Until the Federal Reserve Act, the U.S. government had left control of its money supply largely to unregulated private banks. While the official medium of exchange was gold coins, most loans and payments were carried out with bank notes, backed by the promise of redemption in gold. The trouble with this system was that the banks were tempted to reach beyond their cash reserves, prompting periodic panics during which fearful depositors raced to turn their bank paper into coin. With the passage of the act, greater flexibility in the money supply was assured, and provision was made for issuing federal reserve notes—paper dollars—to meet business demands. The Fed opened in 1914 and played a central role in funding the World War. After 1914, issues of money and banking faded away from the political agenda.

To resolve the long-standing dispute over trusts, the Wilson Administration dropped the "trust-busting" legal strategies of Roosevelt and Taft and relied on the new a Federal Trade Commission

to issue orders prohibiting "unfair methods of competition" by business concerns in interstate trade. In addition a second law, the Clayton Antitrust Act

, forbade many corporate practices that had thus far escaped specific condemnation—interlocking directorates, price discrimination among purchasers, use of the injunction in labor disputes and ownership by one corporation of stock in similar enterprises. After 1914 the trust issue faded away from politics.

The Adamson Act

of 1916 established an eight-hour day for railroad labor and solidified the ties between the labor unions and the Democratic Party. The record of achievement won Wilson a firm place in American history as one of the nation's foremost liberal reformers. Wilson's domestic reputation would soon be overshadowed by his record as a wartime President who led his country to victory but could not hold the support of his people for the peace that followed.

began in Europe in 1914, the United States helped supply the Allies, but could not ship anything to Britain because of the German blockade. Sympathies among many politically and culturally influential Americans had favored the British cause from the start of the war, as typified by industrialist Samuel Insull

, born in London, who helped young Americans enlist in British or Canadian forces. On the other hand, especially in the Midwest, many Irish Americans and German Americans opposed any American involvement, the Irish because they hated the British, and the Germans because they feared they would come under attack.

German efforts to use its submarines ("U-boats") to blockade Britain resulted in the deaths of American travelers and sailors, and attacks on passenger liners caused public outrage. Most notable was torpedoing without warning the passenger liner Lusitania

in 1915. Germany promised not to repeat but decided in early 1917 that unrestricted U-boat warfare against all ships headed to Britain would win the war, albeit at the cost of American entry. When Americans read the text of the German offer to Mexico, known as the Zimmermann Telegram

, they saw an offer for Mexico to go to war with Germany against the United States, with German funding, with the promise of the return of the lost territories of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

Congress voted on April 6, 1917 to declare war, but it was far from unanimous.

. Former president Theodore Roosevelt

denounced "hyphenated American

ism", insisting that dual loyalties were impossible in wartime. A small minority came out for Germany, or ridiculed the British. About 1% of the 480,000 enemy aliens of German birth were imprisoned in 1917-18. The allegations included spying for Germany, or endorsing the German war effort. Thousands were forced to buy war bonds to show their loyalty. One person was killed by a mob; in Collinsville, Illinois

, German-born Robert Prager

was dragged from jail as a suspected spy and lynched. The war saw a phobia of anything German engulf the nation. Sauerkraut was rechristened "liberty cabbage", for example

(CPI) to control war information and provide pro-war propaganda. The private American Protective League

, working with the Federal Bureau of Investigation

, was one of many private right-wing "patriotic associations" that sprang up to support the war and at the same time fight labor unions and various left-wing and anti-war organizations. The U.S. Congress passed, and Wilson signed, the Espionage Act of 1917

and the Sedition Act of 1918

. The Sedition Act criminalized any expression of opinion that used "disloyal, profane, scurrilous or abusive language" about the U.S. government, flag or armed forces. Government police action, private vigilante groups and public war hysteria compromised the civil liberties of many Americans who disagreed with Wilson's policies.

s of factories, producing tanks, trucks and munitions. For the first time, department stores employed African American women as elevator operators and cafeteria waitresses. The Food Administration helped housewives prepare nutritious meals with less waste and with optimum use of the foods available. Most important, the morale of the women remained high, as millions join the Red Cross as volunteers to help soldiers and their families. With rare exceptions, the women did not protest the draft.

, head of the AFL, and nearly all labor unions were strong supporters of the war effort. They minimized strikes as wages soared and full employment was reached. The AFL unions strongly encouraged their young men to enlist in the military, and fiercely opposed efforts to reduce recruiting and slow war production by the anti-war IWW and left-wing Socialists. President Wilson appointed Gompers to the powerful Council of National Defense

, where he set up the War Committee on Labor. The AFL membership soared to 2.4 million in 1917. In 1919, the Union tried to make their gains permanent and called a series of major strikes in meat, steel and other industries. The strikes, all of which failed, forced unions back to their position around 1910. Anti-war socialists controlled the IWW

, which fought against the war effort and was in turn shut down by legal action by the federal government.

armies in the summer of 1918. They arrived at the rate of 10,000 a day, at a time that the Germans were unable to replace their losses. After the Allies turned back the powerful final German offensive (Spring Offensive

), the Americans played a central role in the Allied final offensive (Hundred Days Offensive

). Victory over Germany achieved on November 11, 1918

.

. The United States Senate

did not ratify the Treaty of Versailles; instead, the United States signed separate peace treaties with Germany and her allies. The Senate also refused to enter the newly created League of Nations

on Wilson's terms, and Wilson rejected the Senate's compromise proposal.

Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age refers to the era of rapid economic and population growth in the United States during the post–Civil War and post-Reconstruction eras of the late 19th century. The term "Gilded Age" was coined by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner in their book The Gilded...

, and the Progressive Era

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s. One main goal of the Progressive movement was purification of government, as Progressives tried to eliminate corruption by exposing and undercutting political...

, and includes the rise of industrialization and the resulting surge of immigration in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

. This period of rapid economic growth and soaring prosperity in North and West (but not the South) saw the U.S. become the world's dominant economic, industrial and agricultural power. The average annual income (after inflation) of nonfarm workers grew by 75% from 1865 to 1900, and then grew another 33% by 1918.

With a decisive victory in 1865 over Southern secessionists in the Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, the United States became a united and powerful nation with a strong national government. Reconstruction brought the end of slavery and citizenship for the former slaves, but their political power was later rolled back and they became second-class citizens under a "Jim Crow" system of segregation

Racial segregation in the United States

Racial segregation in the United States, as a general term, included the racial segregation or hypersegregation of facilities, services, and opportunities such as housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation along racial lines...

. Politically the nation in the Third Party System

Third Party System

The Third Party System is a term of periodization used by historians and political scientists to describe a period in American political history from about 1854 to the mid-1890s that featured profound developments in issues of nationalism, modernization, and race...

and Fourth Party System

Fourth Party System

The Fourth Party System is the term used in political science and history for the period in American political history from about 1896 to 1932 that was dominated by the Republican party, excepting the 1912 split in which Democrats held the White House for eight years. History texts usually call it...

was mostly dominated by Republicans (except for two Democratic presidents). After 1900 the Progressive Era

Progressive Era

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s. One main goal of the Progressive movement was purification of government, as Progressives tried to eliminate corruption by exposing and undercutting political...

brought political and social reforms, such as new roles for education and a higher status for women, and modernized many areas of government and society. The progressives worked through new middle class organizations to fight against the corruption and behind-the-scenes power of entrenched state party organizations and big city machines. They demanded --and obtained in 1920--votes for women and the prohibition of alcohol

Prohibition in the United States

Prohibition in the United States was a national ban on the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol, in place from 1920 to 1933. The ban was mandated by the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, and the Volstead Act set down the rules for enforcing the ban, as well as defining which...

.

In an unprecedented wave of European immigration

Immigration to the United States

Immigration to the United States has been a major source of population growth and cultural change throughout much of the history of the United States. The economic, social, and political aspects of immigration have caused controversy regarding ethnicity, economic benefits, jobs for non-immigrants,...

, 27.5 million new arrivals between 1865 and 1918 provided the labor base for the expansion of industry and agriculture and provided the population base for most of fast-growing urban America.

By the late nineteenth century, the United States had become a leading global industrial power, building on new technologies (such as the telegraph

Telegraphy

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages via some form of signalling technology. Telegraphy requires messages to be converted to a code which is known to both sender and receiver...

and steel

Bessemer process

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass-production of steel from molten pig iron. The process is named after its inventor, Henry Bessemer, who took out a patent on the process in 1855. The process was independently discovered in 1851 by William Kelly...

), an expanding railroad network

Rail transport in the United States

Presently, most rail transport in the United States is based on freight train shipments. The U.S. rail industry has experienced repeated convulsions due to changing U.S. economic needs and the rise of automobile, bus, and air transport....

, and abundant natural resources

Natural Resources

Natural Resources is a soul album released by Motown girl group Martha Reeves and the Vandellas in 1970 on the Gordy label. The album is significant for the Vietnam War ballad "I Should Be Proud" and the slow jam, "Love Guess Who"...

such as coal, timber, oil and farmland, to usher in the Second Industrial Revolution

Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of the larger Industrial Revolution corresponding to the latter half of the 19th century until World War I...

.

There were two important wars. The US easily defeated Spain in 1898

Spanish-American War

The Spanish–American War was a conflict in 1898 between Spain and the United States, effectively the result of American intervention in the ongoing Cuban War of Independence...

, which unexpectedly brought a small empire. Cuba quickly was given independence, and eventually also the Philippines in 1946. Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico , officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico , is an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the Dominican Republic and west of both the United States Virgin Islands and the British Virgin Islands.Puerto Rico comprises an...

and (and some smaller islands) became permanent possessions, as did Alaska

Alaska purchase

The Alaska Purchase was the acquisition of the Alaska territory by the United States from Russia in 1867 by a treaty ratified by the Senate. The purchase, made at the initiative of United States Secretary of State William H. Seward, gained of new United States territory...

, added by purchase in 1867, and the independent Republic of Hawaii

Republic of Hawaii

The Republic of Hawaii was the formal name of the government that controlled Hawaii from 1894 to 1898 when it was run as a republic. The republic period occurred between the administration of the Provisional Government of Hawaii which ended on July 4, 1894 and the adoption of the Newlands...

, was annexed

Newlands Resolution

The Newlands Resolution, was a joint resolution written by and named after United States Congressman Francis G. Newlands. It was an Act of Congress to annex the Republic of Hawaii and create the Territory of Hawaii....

to the United States in 1898.

The United States tried and failed to broker a peace settlement for World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, then entered the war to oppose German militarism. After a slow mobilization the U.S. produced a decisive Allied victory thanks to American financial, agricultural, industrial and military strength.

Reconstruction

Reconstruction was the period from 1863 to 1877 when the national government took control one by one of the Southern statesSouthern United States

The Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

of the Confederacy

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America was a government set up from 1861 to 1865 by 11 Southern slave states of the United States of America that had declared their secession from the U.S...

. Before his assassination in April 1865, Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and...

had announced moderate plans for reconstruction to reintegrate the former Confederates as fast as possible. Lincoln set up the Freedman's Bureau in March 1865, aiding former slaves with education, health care, and employment. The final abolition of slavery was achieved by the Thirteenth Amendment

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution officially abolished and continues to prohibit slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. It was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, passed by the House on January 31, 1865, and adopted on December 6, 1865. On...

, ratified in December 1865. However, he was opposed by Radical Republicans who feared the former Confederates secretly believed in slavery and Confederate nationalism, and tried to impose restrictions that would prevent most ex-rebels from voting or holding office. The Radicals were opposed by President Andrew Johnson, but the Radicals won the critical election of 1866, and overcame Johnson's vetoes. Indeed, they impeached him and almost removed him from office in 1868. Meanwhile, they gave the Freedmen new constitutional and federal legal protections, most of which were lost after conservative white southerners regained control of all Southern states by 1877.

The Radical reconstruction plan went into effect in 1867 under the supervision of the Army, allowing a Republican coalition of Freedmen, Scalawags (local whites) and Carpetbaggers (recent arrivals) took control of Southern state governments and ratified the Fourteenth Amendment

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

, giving enormous new powers to the federal courts to deal with justice at the state level. These governments borrowed heavily to build railroads and public schools, running up the tax rates in the face of increasingly fierce opposition that drove most of the Scalawags into the Democratic Party. President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant was the 18th President of the United States as well as military commander during the Civil War and post-war Reconstruction periods. Under Grant's command, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military and ended the Confederate States of America...

enforced civil rights protection for African Americans in South Carolina, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The Fifteenth Amendment

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude"...

was ratified in 1870 giving African Americans the right to vote in elections. The Civil Rights Act of 1875

Civil Rights Act of 1875

The Civil Rights Act of 1875 was a United States federal law proposed by Senator Charles Sumner and Representative Benjamin F. Butler in 1870...

was passed to give people the right to public facilities regardless of race or previous servitude.

Reconstruction ended at different times in each state, the last in 1877, when Republican Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

won the contentious presidential election of 1876 over his opponent, Samuel J. Tilden

Samuel J. Tilden

Samuel Jones Tilden was the Democratic candidate for the U.S. presidency in the disputed election of 1876, one of the most controversial American elections of the 19th century. He was the 25th Governor of New York...

. To deal with disputed electoral votes, Congress set up an Electoral Commission. It awarded the disputed votes to Hayes. The white South accepted the "Compromise of 1877

Compromise of 1877

The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Corrupt Bargain, refers to a purported informal, unwritten deal that settled the disputed 1876 U.S. Presidential election and ended Congressional Reconstruction. Through it, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was awarded the White House over Democrat Samuel J...

" knowing that Hayes proposed to end Army control over the remaining three state governments in Republican hands. White Northerners accepted that the Civil War was over and that Southern whites posed no threat to the nation.

The end of Reconstruction marked the end of the brief period of civil rights and civil liberties for African Americans in the South, where most lived. Reconstruction caused lasting bitterness among white Southerners toward the federal government, and helped create the "Solid South," which typically voted for Democrats for local, state, and national office. White supremacists created a segregated society through "Jim Crow Laws

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities, with a supposedly "separate but equal" status for black Americans...

" that made blacks second-class citizens with very little political power or public voice. The white elites ("Redeemers

Redeemers

In United States history, "Redeemers" and "Redemption" were terms used by white Southerners to describe a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction era which followed the American Civil War...

", the southern wing of the "Bourbon Democrats") were in firm political and economic control until the rise of the Populist movement in the 1890s. Local law enforcement was weak in rural areas, allowing outraged mobs to use lynching

Lynching in the United States

Lynching, the practice of killing people by extrajudicial mob action, occurred in the United States chiefly from the late 18th century through the 1960s. Lynchings took place most frequently in the South from 1890 to the 1920s, with a peak in the annual toll in 1892.It is associated with...

to redress supposed crimes committed by blacks

Indian assimilation

Expansion into the plains and mountains by miners, ranchers and settlers led to increasing conflictsIndian Wars

American Indian Wars is the name used in the United States to describe a series of conflicts between American settlers or the federal government and the native peoples of North America before and after the American Revolutionary War. The wars resulted from the arrival of European colonizers who...

with the indigenous population of the West

Western United States

.The Western United States, commonly referred to as the American West or simply "the West," traditionally refers to the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. Because the U.S. expanded westward after its founding, the meaning of the West has evolved over time...

. The government insisted the Indians remain on assigned reservations, and used force to keep them there. The violence petered out in the 1880s and practically ceased after 1890. By 1880 the buffalo herds

American Bison

The American bison , also commonly known as the American buffalo, is a North American species of bison that once roamed the grasslands of North America in massive herds...

, a foundation for the hunting economy, had disappeared.

Indians had the choice of living on reservations, where food, supplies, education and medical care was provided by the federal government, or living on their own in society and earning wages, typically as a cowboy on a ranch, or manual worker in town. Reformers wanted to give as many Indians as possible the opportunity to own and operate their own farms and ranches, and the issue was how to give individual Indians land owned by the tribe. To assimilate the Indians into American society, reformers set up training programs and schools, such as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School

Carlisle Indian Industrial School

Carlisle Indian Industrial School was an Indian boarding school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1879 at Carlisle, Pennsylvania by Captain Richard Henry Pratt, the school was the first off-reservation boarding school, and it became a model for Indian boarding schools in other locations...

in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, that produced many prominent Indian leaders. The anti-assimilation traditionalists on the reservations, however, resisted integration. The reformers decided the solution was to allow Indians still on reservations to own land as individuals. In 1887, the Dawes Act

Dawes Act

The Dawes Act, adopted by Congress in 1887, authorized the President of the United States to survey Indian tribal land and divide the land into allotments for individual Indians. The Act was named for its sponsor, Senator Henry L. Dawes of Massachusetts. The Dawes Act was amended in 1891 and again...

proposed to divide tribal land and parcel out 160 acres (0.65 km²) of land to each head of a family. Such allotments were to be held in trust by the government for 25 years, after which time the owner won full title to the land (so that it could be sold or mortgaged), as well as full legal citizenship. Lands not thus distributed, however, were offered for sale to settlers. This policy eventually resulted to the Indian loss, by seizure and sale, of almost half of their tribal lands. It also destroyed much of the communal organization of the tribes, further disrupting the traditional culture of the surviving indigenous population. The Dawes Act was an effort to integrate Indians into the mainstream; the majority accepted integration and were absorbed into American society, leaving a trace of Indian ancestry in millions of American families. Those who refused to assimilate remained in poverty on the reservations, supported by Federal food, medicine and schooling. In 1934, U.S. policy was reversed again by the Indian Reorganization Act

Indian Reorganization Act

The Indian Reorganization Act of June 18, 1934 the Indian New Deal, was U.S. federal legislation that secured certain rights to Native Americans, including Alaska Natives...

which attempted to protect tribal and communal life on the reservations.

Industrialization

From 1865 to about 1913, the U.S. grew to become the world's leading industrial nation. Land and labor, the diversity of climate, the ample presence of railroads (as well as navigable rivers), and the natural resourcesNatural Resources

Natural Resources is a soul album released by Motown girl group Martha Reeves and the Vandellas in 1970 on the Gordy label. The album is significant for the Vietnam War ballad "I Should Be Proud" and the slow jam, "Love Guess Who"...

all fostered the cheap extraction of energy, fast transport, and the availability of capital that powered this Second Industrial Revolution

Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of the larger Industrial Revolution corresponding to the latter half of the 19th century until World War I...

. The average annual income (after inflation) of nonfarm workers grew by 75% from 1865 to 1900, and then grew another 33% by 1918.

Where the First Industrial Revolution

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

shifted production from artisans to factories, the Second Industrial Revolution pioneered an expansion in organization, coordination, and the scale of industry

United States technological and industrial history

The technological and industrial history of the United States describes the United States' emergence as one of the largest nations in the world as well as the most technologically powerful nation in the world...

, spurred on by technology and transportation advancements. Railroads opened the West, creating farms, towns and markets where none had existed. The First Transcontinental Railroad

First Transcontinental Railroad

The First Transcontinental Railroad was a railroad line built in the United States of America between 1863 and 1869 by the Central Pacific Railroad of California and the Union Pacific Railroad that connected its statutory Eastern terminus at Council Bluffs, Iowa/Omaha, Nebraska The First...

, built by nationally oriented entrepreneurs with British money and Irish

Irish American

Irish Americans are citizens of the United States who can trace their ancestry to Ireland. A total of 36,278,332 Americans—estimated at 11.9% of the total population—reported Irish ancestry in the 2008 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau...

and Chinese