Irish American

Encyclopedia

Irish Americans are citizens of the United States

who can trace their ancestry to Ireland

. A total of 36,278,332 Americans—estimated at 11.9% of the total population—reported Irish ancestry in the 2008 American Community Survey

conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. Roughly another 3.5 million (or about another 1.2% of Americans) identified more specifically with Scotch-Irish ancestry.

The only self-reported ancestral group larger than Irish Americans is German American

s. The Irish are widely dispersed in terms of geography, and demographics

. Irish American political leaders have played a major role in local and national politics since before the American Revolutionary War

: eight Irish Americans signed the United States Declaration of Independence

, and 22 American Presidents, from Andrew Jackson to Barack Obama, have been at least partly of Irish ancestry. (See "American Presidents with Irish ancestry" below.)

Most colonial settlers coming from the Irish province of Ulster

came to be known in America as the "Scotch-Irish". They were descendants of Scottish

and English

tenant farmers who had been settled in Ireland by the British government during the 17th-century Plantation of Ulster

. An estimated 250,000 migrated to America during the colonial era. The Scotch-Irish settled mainly in the colonial "back country" of the Appalachian Mountain

region, and became the prominent ethnic strain in the culture that developed there. The descendants of Scotch-Irish settlers had a great influence on the later culture of the United States through such contributions as American folk music

, Country and Western

music, and stock car racing

, which became popular throughout the country in the late 20th century.

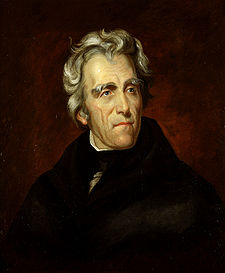

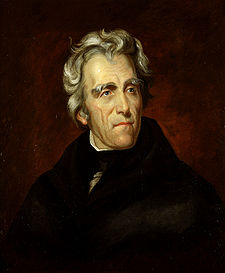

Irish immigrants of this period participated in significant numbers in the American Revolution

, leading one British major general to testify at the House of Commons

that "half the rebel Continental Army were from Ireland." Irish Americans signed the foundational documents of the United States—the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution—and, beginning with Andrew Jackson

, served as President.

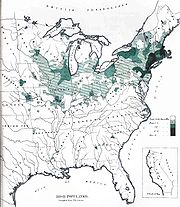

The early Ulster immigrants and their descendants at first usually referred to themselves simply as "Irish," without the qualifier "Scotch." It was not until more than a century later, following the surge in Irish immigration after the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s, that the descendants of the Protestant Irish began to refer to themselves as "Scotch-Irish" to distinguish them from the predominantly Catholic, and largely destitute, wave of immigrants from Ireland in that era. The two groups had little initial interaction in America, as the 18th century Ulster immigrants were predominantly Protestant and had become settled largely in upland regions of the American interior, while the huge wave of 19th-century Catholic immigrant families settled primarily in the Northeast and Midwest port cities such as Boston, New York, or Chicago. However, beginning in the early 19th century, many Irish migrated individually to the interior for work on large-scale infrastructure projects such as canals and, later in the century, railroads

.

Irish Catholics concentrated in a few medium-sized cities, where they were highly visible, especially in Charleston

, Savannah

and New Orleans. They became local leaders in the Democratic party, generally favored preserving the Union in 1860, but became staunch Confederates after secession in 1861.

In 1820 Irish-born John England became the first Catholic bishop in the mainly Protestant city of Charleston, South Carolina

. During the 1820s and '30s, England defended the Catholic minority against Protestant prejudices. In 1831 and 1835, he established free schools for free African American children. Inflamed by the propaganda of the American Anti-Slavery Society

, a mob raided the Charleston post office in 1835 and the next day turned its attention to England's school. England led Charleston's "Irish Volunteers" to defend the school. Soon after this, however, all schools for "free blacks" were closed in Charleston, and England acquiesced.

Beginning as unskilled laborers, Irish Catholics in the South achieved average or above average economic status by 1900. David T. Gleeson wrote:

Irish immigration had greatly increased beginning in the 1820s due to the need for labor in canal building, lumbering, and civil construction works in the Northeast. The large Erie Canal

Irish immigration had greatly increased beginning in the 1820s due to the need for labor in canal building, lumbering, and civil construction works in the Northeast. The large Erie Canal

project was one such example where Irishmen were many of the laborers. Small but tight communities developed in growing cities such as Philadelphia, Boston

, New York

and Providence

.

From 1820 to 1860, 1,956,557 Irish arrived, 75% of these after the Great Irish Famine (or The Great Hunger) of 1845–1852, struck. The Famine hurt Irish men and women alike, especially those poorest or without land. It altered the family structures of Ireland because fewer people could afford to marry and raise children, causing many to adopt a single lifestyle. Consequently, many Irish citizens were less bound to family obligations and could more easily migrate to the United States in the following decade.

Of the total Irish migrants

to the U.S. from 1820 to 1860, many died crossing the ocean due to disease and dismal conditions of what became known as coffin ship

s.

Most Irish immigrants to the United States favored large cities because they could create their own communities for support and protection in a new environment. Another reason for this trend was that Irish immigrants could not afford to move inland and had to settle close to the ports at which they arrived. Cities with large numbers of Irish immigrants included Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, as well as Pittsburgh, Baltimore

Most Irish immigrants to the United States favored large cities because they could create their own communities for support and protection in a new environment. Another reason for this trend was that Irish immigrants could not afford to move inland and had to settle close to the ports at which they arrived. Cities with large numbers of Irish immigrants included Boston, Philadelphia, and New York, as well as Pittsburgh, Baltimore

, Detroit

, Chicago

, St. Louis

, San Francisco, and Los Angeles

. In 1910, there were more people in New York City of Irish heritage than Dublin's whole population, and even today, many of these cities still retain a substantial Irish American community. Mill towns such as Lawrence

, Lowell

, and Pawtucket

attracted many Irish women in particular. The best urban economic opportunities for unskilled Irish women and men included “factory and millwork, domestic service, and the physical labor of public work projects.”

Irish women’s initial experiences in the United States were largely shaped by the types of roles they fulfilled in their homeland. Although Irish culture gave more authority to husbands and fathers, it simultaneously recognized female power. In most cases in Ireland, wives handled money within the family, and a large number of them even worked in cities away from the home in domestic work or sales. Although older women asserted this kind of power, daughters were seen as less valuable than sons due to the patriarchal nature of society. As a result, young women had little hesitation in migrating, and their families saved money in order help finance the trip abroad. Limited social and economic opportunities for daughters in Ireland in the second half of the nineteenth century caused a wave of young women to search for better possibilities in the United States. The pull factors of the United States, especially job availability, caused Irish women to view their “journey with optimism, in a forward-looking assessment that in America they could achieve a status that they never could have at home.”

The female exodus of the mid-nineteenth century stands out in American history as the only major group of immigrants that was over fifty percent women. Because of the decrease in marriages in Ireland, single Irish women, called “unprovided-for ‘girls’”, traveled to the United States to find employment and/or start families of their own. Frustrated by the hardships of Irish farm life and alone in a new country without the help of other family members, female immigrants tended to settle in urban areas to find work. Occupational options, such as domestic work, white-collar work, nursing and teaching, granted more authority to young women in the United States than in Ireland. Recognizing their own successes as single women, most decided to postpone marriage and taught their daughters to do the same. In fact, the majority of the most successful Irish women in America never married, and a significant number of them were nuns.

Employment, not marriage, continued to be Irish women’s priority throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, and women outnumbered men in cities and mill towns where they worked in “factory jobs and millwork, domestic service and, later in the century, clerical and shop work.” However, Catholicism preached the centrality of women in the home, and Irish immigrants still respected the Church as the most important institution in their lives. Consequently, Irish women still pursued marriage and bore many children as long as they could meet economic needs. Couples that could not support large families often had many children regardless of their economic status, and due to discrimination against Irish men in the workplace and their tendency to desert their wives, women usually bore the brunt of family responsibility.

After 1860, Irish immigration continued, with another 1,916,547 arriving by 1900, mainly due to family reunification

, mostly to the industrial town and cities where Irish American neighborhoods had previously been established.

During the American Civil War

, Irish Americans volunteered in high numbers for the Union army, and at least thirty-eight Union regiments had the word "Irish" in their title. However, conscription was resisted by the Irish and others as an imposition on liberty. When the conscription law was passed in 1863, draft riots

erupted in New York. The New York draft coincided with the efforts of Tammany Hall to enroll Irish immigrants as citizens so they could vote in local elections. Many such immigrants suddenly discovered they were now expected to fight for their new country. The Irish, employed primarily as laborers, were usually unable to afford the $300 as a "commutation fee" to procure exemption from service, while more established New Yorkers receiving better pay were able to hire substitutes and avoid the draft. Many of the recent immigrants viewed freed slaves as competition for scarce jobs, and as the reason why the Civil War was being fought. African Americans who fell into the mob's hands were often beaten, tortured, or killed, including one man, William Jones, who was attacked by a crowd of 400 with clubs and paving stones, then hung from a tree and set alight.

The Colored Orphan Asylum on Fifth Avenue, which provided shelter for hundreds of children, was attacked by a mob, although the largely Irish-American police force was able to secure the orphanage for enough time to allow orphans to escape.

In 1871, New York's Orange Riots

were incited by Irish Protestants celebrating the Battle of the Boyne

with parades through predominantly Catholic neighborhoods. 63 citizens, mostly Irish Catholics, were massacred in the resulting police-action.

speakers, bilingual speakers of both Irish and English

, and monolingual English speakers. Estimates indicate that there were around 400,000 Irish speakers in the United States in the 1890s, located primarily in New York City

, Philadelphia, Boston

, Chicago

and Yonkers. The Irish speaking population of New York reached its height in this period, when speakers of Irish numbered between 70,000 and 80,000. This number declined during the early 20th century, dropping to 40,000 in 1939, 10,000 in 1979 and 5,000 in 1995. According to the latest census, the Irish language ranks 66th out of the 322 languages spoken today in the U.S., with over 25,000 speakers. New York State has the most Irish Gaelic speakers, and Massachusetts the highest percentage, of the 50 states. Daltaí na Gaeilge

, a nonprofit Gaelic language advocacy group based in Elberon, New Jersey

, estimated that about 30,000 speak the language as of 2006. This, the organization claimed, has seen an increase from only a few thousand at the time of its founding in 1981.

After 1840 most Irish Catholic immigrants went directly to the cities, mill towns, and railroad or canal construction sites in the east coast. In upstate New York, the Great Lakes area, the Midwest and the Far West, many became farmers or ranchers. In the East, male Irish laborers were hired by Irish contractors to work on canals, railroads, streets, sewers and other construction projects, particularly in New York state

and New England

. Large numbers moved to New England mill towns, such as Holyoke

, Lowell

, Taunton

, Brockton

, Fall River

, and Milford

, Massachusetts

, where owners of textile mills welcomed the new low-wage workers. They took the jobs previously held by Yankee

women known as Lowell girls. A large fraction of Irish Catholic women took jobs as maids in hotels and private households.

Large numbers of unemployed or very poor Irish Catholics lived in squalid conditions in the new city slums and tenements. The Irish were the poorest of all immigrant groups that arrived in the United States in the nineteenth century, and many women especially suffered as a result of being abandoned or widowed. Consequently, there were many cases of mental and physical illnesses, as well as alcohol abuse and instances of crime, among women of Irish neighborhoods.

Single, Irish immigrant women quickly assumed jobs in high demand but for very low pay. The majority of them worked in mills, factories, and private households and were considered the bottommost group in the female job hierarchy, alongside African American women. Workers considered mill work in cotton textiles and needle trades the least desirable because of the dangerous and unpleasant conditions. Factory work was primarily a worst case scenario for widows or daughters of families already involved in the industry. Unlike many other immigrants, Irish women preferred domestic work because it was constantly in great demand among middle- and upper-class American households. Although wages differed across the country, they were consistently higher than those of the other occupations available to Irish women and could often be negotiated because of the lack of competition. Also, the working conditions in well-off households were significantly better than those of factories or mills, and free room and board allowed domestic servants to save money or send it back to their families in Ireland.

Despite some of the benefits of domestic work, Irish women’s job requirements were difficult and demeaning. Subject to their employers around the clock, Irish women cooked, cleaned, babysat and more. Because most servants lived in the home where they worked, they were separated from their communities. Most of all, the American stigma on domestic work suggested that Irish women were failures who had “about the same intelligence as that of an old grey-headed negro.” This quote illustrates how, in a period of extreme racism

towards African Americans, society similarly viewed Irish immigrants as inferior beings.

Although the Irish Catholics started very low on the social status scale, by 1900, they had jobs and earnings about equal on average to their neighbors. After 1945, the Catholic Irish consistently ranked toward the top of the social hierarchy, thanks especially to their high rate of college attendance.

, himself an Englishman having been born in Liverpool, England in 1806, almost 17 percent of the police department's officers were Irish-born (compared to 28.2 percent of the city) in a report to the Board of Alderman

. In the 1860s more than half of those arrested in New York City were Irish born or of Irish descent but nearly half of the City's law enforcement officers were also Irish. By the turn of the 20th century, five out of six NYPD officers were Irish born or of Irish descent. As late as 1960s, even after minority hiring efforts, 42% of the NYPD were Irish Americans.

Irish Catholics continue to be prominent in the law enforcement community, especially in New England. When the Emerald Society

of the Boston Police Department

was formed in 1973, half of the city's police officers became members.

and participated in the many American sisterhoods, especially those in St. Louis

in Missouri, St. Paul in Minnesota, and Troy

in New York. Additionally, the women who settled in these communities were often sent back to Ireland to recruit. This kind of religious lifestyle appealed to Irish female immigrants because they outnumbered their male counterparts and the Irish cultural tendency to postpone marriage often promoted gender separation and celibacy. Furthermore, “The Catholic church, clergy, and women religious were highly respected in Ireland,” making the sisterhoods particularly attractive to Irish immigrants. Nuns provided extensive support for Irish immigrants in large cities, especially in fields such as nursing and teaching but also through orphanages, widows’ homes, and housing for young, single women in domestic work. Although many Irish communities built parish schools run by nuns, the majority of Irish parents in large cities in the East enrolled their children in the public school system, where daughters or granddaughters of Irish immigrants had already established themselves as teachers.

Surveys in the 1990s show that of Americans who identify themselves as "Irish", 51% said they were Protestant and 36% Catholic. In the South, Protestants account for 73% of those claiming Irish origins, while Catholics account for 19%. In the North, 45% of those claiming Irish origin are Catholic, while 39% are Protestant.

began thereafter to redefine themselves as "Scotch Irish", to stress their historic origins, and distanced themselves from Irish Catholics. By 1830, Irish diaspora demographics had changed rapidly, with over 60% of all Irish settlers in the US being Catholics from rural areas of Ireland.

Some Protestant Irish immigrants became active in explicitly anti-Catholic organizations such as the Orange Institution

and the American Protective Association

. However, participation in the Orange Institution was never as large in the United States as it was in Canada. In the early nineteenth century, the post-Revolutionary republican spirit of the new United States attracted exiled United Irishmen such as Theobald Wolf Tone and others. Most Protestant Irish immigrants in the first several decades of the nineteenth century were those who held to the republicanism of the 1790s, and who were unable to accept Orangeism. Loyalists and Orangemen made up a minority of Irish Protestant immigrants to the United States during this period. Most of the Irish loyalist emigration was bound for Upper Canada

and the Canadian Maritime provinces, where Orange lodges were able to flourish under the British flag.

By 1870, when there were about 930 Orange lodges in the Canadian province of Ontario, there were only 43 in the entire eastern United States. These few American lodges were founded by newly arriving Protestant Irish immigrants in coastal cities such as Philadelphia and New York. These ventures were short-lived and of limited political and social impact, although there were specific instances of violence involving Orangemen between Catholic and Protestant Irish immigrants, such as the Orange Riots

in New York City in 1824, 1870 and 1871.

The first "Orange riot" on record was in 1824, in Abingdon, NY, resulting from a 12 July march. Several Orangemen were arrested and found guilty of inciting the riot. According to the State prosecutor in the court record, "the Orange celebration was until then unknown in the country". The immigrants involved were admonished: "In the United States the oppressed of all nations find an asylum, and all that is asked in return is that they become law-abiding citizens. Orangemen, Ribbonmen, and United Irishmen are alike unknown. They are all entitled to protection by the laws of the country."

The later Orange riots of 1870 and 1871 killed nearly 70 people, and were fought out between Irish Protestant and Catholic immigrants. After this the activities of the Orange Order were banned for a time, the Order dissolved, and most members joined Masonic Orders. After 1871, there were no more riots between Irish Catholics and Protestants.

America offered a new beginning, and "...most descendents of the Ulster Presbyterians of the eighteenth century and even many new Protestant Irish immigrants turned their backs on all associations with Ireland and melted into the American Protestant mainstream."

was an Irishman in recognition of the contribution of the early Irish clergy.

In Boston 1810–40 there had been serious tensions between the bishop and the laity who wanted to control the local parishes. By 1845 the Catholic population in Boston had increased to 30,000 from around 5,000 in 1825, due to the influx of Irish immigrants. With the appointment of John B. Fitzpatrick as bishop in 1845 tensions subsided as the increasingly Irish Catholic community grew to support Fitzpatrick's assertion of the bishop's control of parish government.

In New York, Archbishop John Hughes

(1797–1864), an Irish immigrant himself, was deeply involved in "the Irish question"—Irish independence from British rule

. Hughes supported Daniel O'Connell

's Catholic emancipation movement in Ireland, but rejected such radical and violent societies as the Young Irelanders and the National Brotherhood. Hughes also disapproved of American Irish radical fringe groups, urging immigrants to assimilate themselves into American life while remaining patriotic to Ireland 'only individually.' In Hughes's view, a large-scale movement to form Irish settlements in the western United States was too isolationist and ultimately detrimental to immigrants' success in the New World.

In the 1840s, Hughes crusaded for public funded Irish Schools modeled after the successful Irish Public School System in Lowell

. Hughes denounced the Public School Society of New York as an extension of an Old-World struggle whose outcome was directed not by understanding of the basic problems but, rather, by mutual mistrust and violently inflamed emotions. For Irish Catholics, the motivation lay largely memory of British oppression, while their antagonists were dominated by the English Protestant historic phobia against papal interference in civil affairs. Because of the vehemence of this quarrel, the New York Legislature passed the Maclay Act in 1842, giving New York City an elective Board of Education empowered to build and supervise schools and distribute the education fund—but with the proviso that none of the money should go to the schools which taught religion. Hughes responded by building an elaborate parochial school

system that stretched to the college level, setting a policy followed in other large cities. Efforts to get city or state funding failed because of vehement Protestant opposition to a system that rivaled the public schools.

Jesuits established a network of colleges in major cities, including Boston College, Fordham in New York, and Georgetown. Fordham was founded in 1841 and attracted students from other regions of the United States, and even South America and the Caribbean. At first exclusively a liberal arts

institution, it built a science building in 1886, lending more legitimacy to science in the curriculum there. In addition, a three-year bachelor of science degree was created. Boston College, by contrast, was established over twenty years later in 1863 to appeal to urban Irish Catholics. It offered a rather limited intellectual curriculum, however, the priests at Boston College prioritizing spiritual and sacramental activities over intellectual pursuits. One consequence was that Harvard Law School would not admit Boston College graduates to its law school. Modern Jesuit leadership in American academia was not to became their hallmark across all institutions until the 20th century.

The Irish became prominent in the leadership of the Catholic Church in the U.S. by the 1850s—by 1890 there were 7.3 million Catholics in the U.S. and growing, and most bishops were Irish. As late as the 1970s, when Irish were 17% of American Catholics, they were 35% of the priests and 50% of the bishops, together with a similar proportion of presidents of Catholic colleges and hospitals.

from the 1740s to the 1840s. They take pride in their Irish heritage because they identify with the values ascribed to the Scotch-Irish who played a major role in the American Revolution and in the development of American culture. The strongly held religious beliefs of the Scotch-Irish led to the emergence of the Bible Belt

, where evangelical

Protestantism continues to play a large role today.

, in 1746 in order to train ministers dedicated to their views. The college was the educational and religious capital of Scotch-Irish America. By 1808, loss of confidence in the college within the Presbyterian Church led to the establishment of the separate Princeton Theological Seminary

, but deep Presbyterian influence at the college continued through the 1910s, as typified by university president Woodrow Wilson

.

Out on the frontier, the Scotch-Irish Presbyterians of the Muskingum Valley in Ohio established the Muskingum College

at New Concord in 1837. It was led by two clergymen, Samuel Wilson and Benjamin Waddle, who served as trustees, president, and professors during the first few years. During the 1840s and 1850s the college survived the rapid turnover of very young presidents who used the post as a stepping stone in their clerical careers, and in the late 1850s it weathered a storm of student protest. Under the leadership of L. B. W. Shryock during the Civil War, Muskingum gradually evolved from a local and locally controlled institution to one serving the entire Muskingum Valley. It is still affiliated with the Presbyterian church.

Brought up in a Scotch-Irish Presbyterian home, Cyrus McCormick

of Chicago developed a strong sense of devotion to the Presbyterian Church. Throughout his later life he used the wealth gained through invention of the reaper to further the work of the church. His benefactions were responsible for the establishment in Chicago of the Presbyterian Theological Seminary of the Northwest (after his death renamed the McCormick Theological Seminary

of the Presbyterian Church). He assisted the Union Presbyterian Seminary in Richmond, Virginia. He also supported a series of religious publications, beginning with the Presbyterian Expositor in 1857 and ending with the Interior (later called The Continent), which his widow continued until her death.

Catholics and Protestants kept their distance; intermarriage between Catholics and Protestants was uncommon, and strongly discouraged by both ministers and priests.

Catholics and Protestants kept their distance; intermarriage between Catholics and Protestants was uncommon, and strongly discouraged by both ministers and priests.

After the large influx of Irish in the middle of the 19th century, many Catholic children were being educated in public schools. While officially nondenominational, the King James Version of the Bible was widely used in the classroom across the country, which Catholics were forbidden to read. Many Irish children complained that Catholicism was openly mocked in the classroom. In New York City the curriculum vividly portrayed Catholics, and specifically the Irish, as villainous. The Catholic clergyman John Hughes

campaigned for public funding of Catholic education

in response to the bigotry. While never successful in obtaining public money for private education, the debate with the city's Protestant elite spurred by Hughes' passionate campaign paved the way for the secularization of public education nationwide. In addition, Catholic higher education

expanded during this period with colleges and universities that evolved into such institutions as Fordham University

and Boston College

providing alternatives to Irish who were not otherwise permitted to apply to other colleges.

Prejudice against Irish Catholics in the US reached a peak in the mid-1850s with the Know Nothing

Movement, which tried to oust Catholics from public office. After a year or two of local success, the Know Nothing Party vanished.

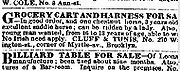

After 1860—and well into the 20th century Protestants refused to hire them; "HELP WANTED - NO IRISH NEED APPLY" was in operation. They called these "the NINA signs". NINA signs were common in London in the early 19th century, and the memory of this discrimination in Britain

After 1860—and well into the 20th century Protestants refused to hire them; "HELP WANTED - NO IRISH NEED APPLY" was in operation. They called these "the NINA signs". NINA signs were common in London in the early 19th century, and the memory of this discrimination in Britain

was imported to the US. After 1860 the Irish sang songs (see illustration) about NINA signs. Some historians, however, maintain that actual job discrimination was minimal.

Many Irish work gangs were hired by contractors to build canals, railroads, city streets and sewers across the country. In the South they underbid slave labor. One result was that small cities that served as railroad centers came to have large Irish populations.

, and dependent on street gangs that were often violent or criminal. Potter quotes contemporary newspaper images:

The Irish had many humorists of their own, but were scathingly attacked in political cartoons, especially those in Puck

magazine from the 1870s to 1900. In addition, the cartoons of Thomas Nast

were especially hostile; for example, he depicted the Irish-dominated Tammany Hall

machine in New York City as a ferocious tiger.

The stereotyope of the Irish as violent drunks has lasted well beyond its high point in the mid-19th century. For example, President Richard Nixon

once told advisor Charles Colson

that “[t]he Irish have certain — for example, the Irish can’t drink. What you always have to remember with the Irish is they get mean. Virtually every Irish I’ve known gets mean when he drinks. Particularly the real Irish.”

Discrimination of Irish Americans differed depending on gender. For example, Irish women were sometimes stereotyped as "reckless breeders" because of American Protestants' fears of the growing number of Irish Catholic babies. Many native-born Americans claimed that "their incessant childbearing [would] ensure an Irish political takeover of American cities [and that] Catholicism would become the reigning faith of the hitherto Protestant nation." Irish men were also targeted but in a different way than women were. The difference between the Irish female "Bridget" and the Irish male "Pat" was distinct; while she was impulsive but fairly harmless, he was "always drunk, eternally fighting, lazy, and shiftless." In contrast to the view that Irish women were shiftless, slovenly, and stupid (like their male counterparts), girls were said to be "industrious, willing, cheerful, and honest—they work hard, and they are very strictly moral."

Americans believed that Irish men, not women, were primarily responsible for any problems that arose in the family. Even Irish people themselves viewed Irish men as the cause of family disintegration while women were “pillars of strength” that could uplift their families out of poverty and into the middle class. In this sense, Irish women were similar to their American counterparts as mothers with moral authority.

Many people Irish descent retain a sense of their Irish heritage. A sense of exile, diaspora

Many people Irish descent retain a sense of their Irish heritage. A sense of exile, diaspora

, and (in the case of songs) even nostalgia is a common theme. The term "Plastic Paddy

" generally used to someone who was not born in Ireland and who is separated from his closest Irish-born ancestor by several generations, but who still considers himself "Irish," is occasionally used in a derogatory fashion towards Irish Americans typically by British

and Ulster loyalists

, in addition to some Irish citizens (many of whom adhere to a form of Irish Socialist Republicanism

), in an attempt to undermine the "Irishness" of the Irish diaspora based on nationality

(citizenship

) rather than ethnicity. The term is freely applied to relevant people of all nationalities, not solely Irish Americans.

Many Irish Americans were enthusiastic supporters of Irish independence; the Fenian Brotherhood

movement was based in the United States and in the late 1860s launched several unsuccessful attacks on British-controlled Canada known as the "Fenian Raids

". The Provisional IRA received significant funding for its paramilitary activities from a group of Irish American supporters—in 1984, the US Department of Justice

won a court case forcing the Irish American fund raising organization NORAID

to acknowledge the Provisional IRA as its "foreign principal".

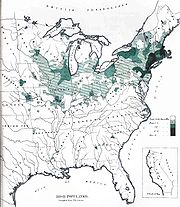

Irish Catholic Americans settled in large and small cities throughout the North, particularly railroad centers and mill towns. They became perhaps the most urbanized group in America, as few became farmers. Areas that retain a significant Irish American population include the metropolitan areas of Boston

Irish Catholic Americans settled in large and small cities throughout the North, particularly railroad centers and mill towns. They became perhaps the most urbanized group in America, as few became farmers. Areas that retain a significant Irish American population include the metropolitan areas of Boston

, Hartford, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Baltimore

, New York City

, Chicago

, Cincinnati and San Francisco, where most new arrivals of the 1830–1910 period settled. As a percentage of the population, Massachusetts is the most Irish state, with about a quarter of the population claiming Irish descent. The most Irish American towns in the United States are Scituate, Massachusetts

with 47.5% of its residents being of Irish descent, Evergreen Park, Illinois

, with 39.6% of its 19,236 residents being of Irish descent,Milton, Massachusetts

, with 38% of its 26,000 being of Irish descent and Braintree, Massachusetts

with 36% of its 34,000 being of Irish descent. Boston, New York, and Chicago have neighborhoods with higher percentages of Irish American residents. Regionally, the most Irish American states are Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland. In consequence of its unique history as a mining center, Butte, Montana

is also one of the country's most thoroughly Irish American cities. Greeley, Nebraska

(population 527) has the highest percentage of Irish American residents (43%) of any town or city with a population of over 500 in the United States. The town was part of the Irish Catholic Colonization effort of Bishop O'Connor of New York in the 1880s.

The United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence

contained fifty-six delegate signatures. Of the signers, eight were of Irish descent. Three signers, Matthew Thornton

, George Taylor

and James Smith were born in Ireland, the remaining five Irish Americans were the sons or grandsons of Irish immigrants: George Read, Thomas McKean

, Thomas Lynch, Jr.

, Edward Rutledge

and Charles Carroll

. The secretary, also Irish American, though not a delegate signed as well: Charles Thompson

. The Constitution of the United States was created by a convention

of thirty-six delegates. Of these as least six were Irish American. George Read and Thomas McKean had already worked on the Declaration, and were joined by John Rutledge

, Pierce Butler

, Daniel Carroll

, and Thomas Fitzsimons

. The Carrolls and Fitzsimmons were Catholic, the remainder Protestant denominations.

After the early example of Charles Lynch, the Catholic Irish moved rapidly into law enforcement, built hundreds of schools, colleges, orphanages, hospitals, and asylums. Political opposition to the Catholic Irish climaxed in 1854 in the short-lived Know Nothing Party.

After the early example of Charles Lynch, the Catholic Irish moved rapidly into law enforcement, built hundreds of schools, colleges, orphanages, hospitals, and asylums. Political opposition to the Catholic Irish climaxed in 1854 in the short-lived Know Nothing Party.

By the 1850s, the Irish Catholics were already a major presence in the police departments of large cities. In New York City in 1855, of the city's 1,149 policemen, 305 were natives of Ireland. Both Boston's police and fire departments provided many Irish immigrants with their first jobs. The creation of a unified police force in Philadelphia opened the door to the Irish in that city. By 1860 in Chicago, 49 of the 107 on the police force were Irish. Chief O'Leary headed the police force in New Orleans and Malachi Fallon was chief of police of San Francisco.

The Irish Catholic diaspora are very well organized, and, since 1850, have produced a majority of the leaders of the U.S. Catholic Church, labor unions, the Democratic Party in larger cities, and Catholic high schools, colleges and universities. John F. Kennedy

was their greatest political hero. Al Smith

, who lost to Herbert Hoover

in the 1928 presidential election

, was the first Irish Catholic to run for president. From the 1830s to the 1960s, Irish Catholics voted 80–95% Democratic, with occasional exceptions like the election of 1920. Senator Joseph McCarthy

, who inspired the term "McCarthyism

", is a very notable Republican exception to the Irish-American connection with the Democratic Party.

Today, Irish politicians are associated with both the Democratic Party and the Republican Party. Ronald Reagan

boasted of his Irishness ). Historically, Irish Catholics controlled many city machines and often served as chairmen of the Democratic National Committee, including County Monaghan

native Thomas Taggart

, Vance McCormick, James Farley

, Edward J. Flynn

, Robert E. Hannegan

, J. Howard McGrath

, William H. Boyle, Jr., John Moran Bailey

, Larry O'Brien

, Christopher J. Dodd, Terry McAuliffe

and Tim Kaine

. Irish in Congress are represented in both parties; currently Susan Collins

of Maine, Pat Toomey

of Pennsylvania, Bob Casey, Jr.

of Pennsylvania, Lisa Murkowski

of Alaska, Dick Durbin of Illinois, Pat Leahy

of Vermont, and Maria Cantwell

of Washington are Irish Americans serving in the United States Senate. Exit polls show that in recent presidential elections Irish Catholics have split about 50–50 for Democratic and Republican candidates; large majorities voted for Ronald Reagan. The pro-life faction in the Democratic party includes many Irish Catholic politicians, such as the former Boston

mayor and ambassador to the Vatican Ray Flynn and senator Bob Casey, Jr.

, who defeated Senator Rick Santorum

in a high visibility race in Pennsylvania in 2006.

In some states such as Connecticut

In some states such as Connecticut

, the most heavily Irish communities now tend to be in the outer suburbs and generally support Republican candidates, such as New Fairfield.

Many major cities have elected Irish American Catholic mayors. Indeed, Boston, Baltimore, Maryland, Cincinnati, Ohio

, Houston, Texas

, Newark

, New York City

, Omaha, Nebraska

, Scranton, Pennsylvania

, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

, Saint Louis, Missouri, Saint Paul, Minnesota

, and San Francisco have all elected natives of Ireland as mayors. Chicago

, Boston, and Jersey City, New Jersey

have had more Irish American mayors than any other ethnic group. The cities of Milwaukee, Wisconsin

, Oakland, California

, Omaha, St. Paul, Jersey City, Rochester, New York

, Northampton, Massachusetts

, Springfield, Massachusetts

, Rockford, Illinois

, San Francisco, Scranton, Seattle and Syracuse, New York

currently have Irish American mayors. Pittsburgh mayor Bob O'Connor died in office in 2006. New York City has had at least three Irish-born mayors and over eight Irish American mayors. The most recent one was County Mayo

native William O'Dwyer

, elected in 1949.

The Irish Protestant vote has not been studied nearly as much. Since the 1840s, it has been uncommon for a Protestant politician to be identified as Irish. In Canada, by contrast, Irish Protestants remained a cohesive political force well into the 20th century with many (but not all) belonging to the Orange Order

. Throughout the 19th century, sectarian confrontation was commonplace between Protestant Irish and Catholic Irish in Canadian cities.

A number of the Presidents of the United States have Irish origins. The extent of Irish heritage varies. For example, Chester Arthur's father and both of Andrew Jackson

A number of the Presidents of the United States have Irish origins. The extent of Irish heritage varies. For example, Chester Arthur's father and both of Andrew Jackson

's parents were Irish born, while George W. Bush

has a rather distant Irish ancestry. Ronald Reagan

's father was of Irish ancestry, while his mother also had some Irish ancestors. President Kennedy

had Irish lineage on both sides. Within this group, only Kennedy was raised as a practicing Roman Catholic. Current President Barack Obama

's Irish heritage originates from his Kansas

-born mother, Ann Dunham

, whose ancestry is Irish and English. His Vice President

Joe Biden

is also an Irish-American.

Andrew Jackson

James Knox Polk

James Buchanan

Andrew Johnson

Ulysses S. Grant

Chester A. Arthur

Grover Cleveland

Benjamin Harrison

William McKinley

Theodore Roosevelt

William Howard Taft

Woodrow Wilson

Warren G. Harding

Harry S. Truman

John F. Kennedy

Richard Nixon

Jimmy Carter

Ronald Reagan

George H. W. Bush

Bill Clinton

George W. Bush

Barack Obama

Sam Houston

The annual celebration of Saint Patrick's Day

The annual celebration of Saint Patrick's Day

may be the most widely recognized symbol of the Irish presence in America. In cities throughout the United States, this traditional Irish religious holiday becomes an opportunity to celebrate all things Irish, or things believed to be "Irish". The largest celebration of the holiday takes place in New York, where the annual St. Patrick's Day Parade draws an average of two million people. The second-largest celebration is held in Boston. The South Boston Parade, is one the nation's oldest dating back to 1737. Savannah

also holds one of the largest parades in the United States.

Since the arrival of nearly two million Irish immigrants in the 1840s, the urban Irish cop and firefighter have become virtual icons of American popular culture. In many large cities, the police and fire departments have been dominated by the Irish for over 100 years, even after the ethnic Irish residential populations in those cities dwindled to small minorities. Many police and fire departments maintain large and active "Emerald Societies

", bagpipe marching groups, or other similar units demonstrating their members' pride in their Irish heritage.

While these archetypal images are especially well known, Irish Americans have contributed to U.S. culture in a wide variety of fields: the fine and performing arts, film, literature, politics, sports, and religion. The Irish-American contribution to popular entertainment is reflected in the careers of figures such as James Cagney

, Bing Crosby

, Walt Disney

, John Ford

, Judy Garland

, Gene Kelly

, Grace Kelly

, Tyrone Power

, Ada Rehan

, and Spencer Tracy

. Irish-born actress Maureen O'Hara

, who became an American citizen, defined for U.S. audiences the archetypal, feisty Irish "colleen" in popular films such as The Quiet Man

and The Long Gray Line

. More recently, the Irish-born Pierce Brosnan

gained screen celebrity as James Bond

. During the early years of television, popular figures with Irish roots included Gracie Allen

, Art Carney

, Joe Flynn

, Jackie Gleason

, and Ed Sullivan

.

Since the early days of the film industry, celluloid representations of Irish Americans have been plentiful. Famous films with Irish-American themes include social dramas such as Little Nellie Kelly

and The Cardinal

, labor epics like On the Waterfront

, and gangster movies such as Angels with Dirty Faces

, Gangs of New York

, and The Departed

. Irish-American characters have been featured in popular television series such as Ryan's Hope

and Rescue Me

.

Prominent Irish-American literary figures include Pulitzer

and Nobel Prize

–winning playwright Eugene O'Neill

, Jazz Age

novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald

, social realist James T. Farrell

, and Southern Gothic

writer Flannery O'Connor

. The 19th-century novelist Henry James

was also of partly Irish descent. While Irish Americans have been underrepresented in the plastic arts, two well-known American painters claim Irish roots. 20th-century painter Georgia O'Keeffe

was born to an Irish-American father, and 19th-century trompe-l'œil painter William Harnett

emigrated from Ireland to the United States.

The Irish-American contribution to politics spans the entire ideological spectrum. Socially conservative Irish immigrants generally recoiled from radical politics, and in the early 1950s, a disproportionate percentage of Irish Americans supported Senator Joseph McCarthy

's anti-Communist "witchhunt". Two prominent American socialists, Mary Harris "Mother" Jones and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn

, were Irish Americans. In the 1960s, Irish-American writer Michael Harrington

became an influential advocate of social welfare programs. Harrington's views profoundly influenced President John F. Kennedy

and his brother, Robert F. Kennedy

. Meanwhile, Irish-American political writer William F. Buckley emerged as a major intellectual force in American conservative

politics in the latter half of the 20th century. Buckley's magazine, National Review

, proved an effective advocate of successful Republican

candidates such as Ronald Reagan

.

Notorious Irish Americans include the legendary New Mexico

outlaw known as Billy the Kid

, whose real name was supposedly Henry McCarty. Many historians believe McCarty was born in New York City to Famine-era immigrants from Ireland. Mary Mallon

, also known as Typhoid Mary was an Irish immigrant, as was madam

Josephine Airey

, who also went by the name of "Chicago Joe" Hensley. New Orleans socialite and murderess Delphine LaLaurie

, whose maiden name was Macarty, was of partial paternal Irish ancestry. Irish-American mobsters

include, amongst others, George "Bugs" Moran, Dean O'Bannion, and Jack "Legs" Diamond. Lee Harvey Oswald

, the assassin of John F. Kennedy had an Irish-born great-grandmother by the name of Mary Tonry. Colorful Irish Americans also include Margaret Tobin

of RMS Titanic fame, scandalous model Evelyn Nesbit

, dancer Isadora Duncan

, San Francisco madam Tessie Wall

, and Nellie Cashman

, nurse and gold prospector in the American west.

The wide popularity of Celtic music has fostered the rise of Irish-American bands that draw heavily on traditional Irish themes and music. Such groups include New York City's Black 47

founded in the late 1980s blending punk rock

, rock and roll

, Irish music, rap/hip-hop

, reggae

, and soul

; and the Dropkick Murphys

, a Celtic punk band formed in Quincy, Massachusetts

nearly a decade later. The Decemberists

, a band featuring Irish-American singer Colin Meloy

, released Shankill Butchers, a song that deals with the Ulster Loyalists

the "Shankill Butchers

". The song appears on their album The Crane Wife

. Flogging Molly

, lead by Dublin-born Dave King, are relative newcomers building upon this new tradition.

The Irish brought their native games of handball

, hurling

and Gaelic football

to America. Along with camogie

, these sports are part of the Gaelic Athletic Association

. The North American GAA

organization is still very strong.

Irish Americans can be found among the earliest stars in professional baseball, including Michael “King” Kelly

, Roger Connor

(the home run king before Babe Ruth), Eddie Collins

, Roger Bresnahan

, Ed Walsh

and NY Giants manager John McGraw

. The large 1945 class of inductees enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York

included nine Irish Americans.

Also of Irish descent, Walter O'Malley

was a real estate businessman and majority team owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. He moved the team to Los Angeles

in 1958 in a deal to bring major league baseball to California

, and he convinced the New York Giants (baseball) team owners move to San Francisco. The O'Malley family owned the Dodgers until they sold the team in 1998.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

who can trace their ancestry to Ireland

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

. A total of 36,278,332 Americans—estimated at 11.9% of the total population—reported Irish ancestry in the 2008 American Community Survey

American Community Survey

The American Community Survey is an ongoing statistical survey by the U.S. Census Bureau, sent to approximately 250,000 addresses monthly . It regularly gathers information previously contained only in the long form of the decennial census...

conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. Roughly another 3.5 million (or about another 1.2% of Americans) identified more specifically with Scotch-Irish ancestry.

The only self-reported ancestral group larger than Irish Americans is German American

German American

German Americans are citizens of the United States of German ancestry and comprise about 51 million people, or 17% of the U.S. population, the country's largest self-reported ancestral group...

s. The Irish are widely dispersed in terms of geography, and demographics

Demographics

Demographics are the most recent statistical characteristics of a population. These types of data are used widely in sociology , public policy, and marketing. Commonly examined demographics include gender, race, age, disabilities, mobility, home ownership, employment status, and even location...

. Irish American political leaders have played a major role in local and national politics since before the American Revolutionary War

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War , the American War of Independence, or simply the Revolutionary War, began as a war between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen British colonies in North America, and ended in a global war between several European great powers.The war was the result of the...

: eight Irish Americans signed the United States Declaration of Independence

United States Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence was a statement adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, which announced that the thirteen American colonies then at war with Great Britain regarded themselves as independent states, and no longer a part of the British Empire. John Adams put forth a...

, and 22 American Presidents, from Andrew Jackson to Barack Obama, have been at least partly of Irish ancestry. (See "American Presidents with Irish ancestry" below.)

Irish immigration to America

18th to mid-19th century

According to the Dictionary of American History, approximately "50,000 to 100,000 Irishmen, over 75 percent of them Catholic, came to America in the 1600s, while 100,000 more Irish Catholics arrived in the 1700s." Indentured servitude was an especially common way of affording migration, and in the 1740s the Irish made up nine out of ten indentured servants in some colonial regions.Most colonial settlers coming from the Irish province of Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

came to be known in America as the "Scotch-Irish". They were descendants of Scottish

Scottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

and English

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

tenant farmers who had been settled in Ireland by the British government during the 17th-century Plantation of Ulster

Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster was the organised colonisation of Ulster—a province of Ireland—by people from Great Britain. Private plantation by wealthy landowners began in 1606, while official plantation controlled by King James I of England and VI of Scotland began in 1609...

. An estimated 250,000 migrated to America during the colonial era. The Scotch-Irish settled mainly in the colonial "back country" of the Appalachian Mountain

Appalachia

Appalachia is a term used to describe a cultural region in the eastern United States that stretches from the Southern Tier of New York state to northern Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia. While the Appalachian Mountains stretch from Belle Isle in Canada to Cheaha Mountain in the U.S...

region, and became the prominent ethnic strain in the culture that developed there. The descendants of Scotch-Irish settlers had a great influence on the later culture of the United States through such contributions as American folk music

American folk music

American folk music is a musical term that encompasses numerous genres, many of which are known as traditional music or roots music. Roots music is a broad category of music including bluegrass, country music, gospel, old time music, jug bands, Appalachian folk, blues, Cajun and Native American...

, Country and Western

Country music

Country music is a popular American musical style that began in the rural Southern United States in the 1920s. It takes its roots from Western cowboy and folk music...

music, and stock car racing

Stock car racing

Stock car racing is a form of automobile racing found mainly in the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Great Britain, Brazil and Argentina. Traditionally, races are run on oval tracks measuring approximately in length...

, which became popular throughout the country in the late 20th century.

Irish immigrants of this period participated in significant numbers in the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, leading one British major general to testify at the House of Commons

House of Commons of Great Britain

The House of Commons of Great Britain was the lower house of the Parliament of Great Britain between 1707 and 1801. In 1707, as a result of the Acts of Union of that year, it replaced the House of Commons of England and the third estate of the Parliament of Scotland, as one of the most significant...

that "half the rebel Continental Army were from Ireland." Irish Americans signed the foundational documents of the United States—the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution—and, beginning with Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the seventh President of the United States . Based in frontier Tennessee, Jackson was a politician and army general who defeated the Creek Indians at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend , and the British at the Battle of New Orleans...

, served as President.

The early Ulster immigrants and their descendants at first usually referred to themselves simply as "Irish," without the qualifier "Scotch." It was not until more than a century later, following the surge in Irish immigration after the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s, that the descendants of the Protestant Irish began to refer to themselves as "Scotch-Irish" to distinguish them from the predominantly Catholic, and largely destitute, wave of immigrants from Ireland in that era. The two groups had little initial interaction in America, as the 18th century Ulster immigrants were predominantly Protestant and had become settled largely in upland regions of the American interior, while the huge wave of 19th-century Catholic immigrant families settled primarily in the Northeast and Midwest port cities such as Boston, New York, or Chicago. However, beginning in the early 19th century, many Irish migrated individually to the interior for work on large-scale infrastructure projects such as canals and, later in the century, railroads

First Transcontinental Railroad

The First Transcontinental Railroad was a railroad line built in the United States of America between 1863 and 1869 by the Central Pacific Railroad of California and the Union Pacific Railroad that connected its statutory Eastern terminus at Council Bluffs, Iowa/Omaha, Nebraska The First...

.

Irish settlement in the South

During the colonial period, the Scotch-Irish settled in the southern Appalachian backcountry and in the Carolina piedmont. They became the primary cultural group in these areas, and their descendants were in the vanguard of westward movement through Virginia into Tennessee and Kentucky, and thence into Arkansas, Missouri and Texas. By the 19th century, through intermarriage with settlers of English and German ancestry, the descendants of the Scotch-Irish lost their identification with Ireland. "This generation of pioneers...was a generation of Americans, not of Englishmen or Germans or Scotch-Irish."Irish Catholics concentrated in a few medium-sized cities, where they were highly visible, especially in Charleston

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the second largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. It was made the county seat of Charleston County in 1901 when Charleston County was founded. The city's original name was Charles Towne in 1670, and it moved to its present location from a location on the west bank of the...

, Savannah

Savannah, Georgia

Savannah is the largest city and the county seat of Chatham County, in the U.S. state of Georgia. Established in 1733, the city of Savannah was the colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later the first state capital of Georgia. Today Savannah is an industrial center and an important...

and New Orleans. They became local leaders in the Democratic party, generally favored preserving the Union in 1860, but became staunch Confederates after secession in 1861.

In 1820 Irish-born John England became the first Catholic bishop in the mainly Protestant city of Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the second largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. It was made the county seat of Charleston County in 1901 when Charleston County was founded. The city's original name was Charles Towne in 1670, and it moved to its present location from a location on the west bank of the...

. During the 1820s and '30s, England defended the Catholic minority against Protestant prejudices. In 1831 and 1835, he established free schools for free African American children. Inflamed by the propaganda of the American Anti-Slavery Society

American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass was a key leader of this society and often spoke at its meetings. William Wells Brown was another freed slave who often spoke at meetings. By 1838, the society had...

, a mob raided the Charleston post office in 1835 and the next day turned its attention to England's school. England led Charleston's "Irish Volunteers" to defend the school. Soon after this, however, all schools for "free blacks" were closed in Charleston, and England acquiesced.

Beginning as unskilled laborers, Irish Catholics in the South achieved average or above average economic status by 1900. David T. Gleeson wrote:

Mid-19th century and later

Erie Canal

The Erie Canal is a waterway in New York that runs about from Albany, New York, on the Hudson River to Buffalo, New York, at Lake Erie, completing a navigable water route from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes. The canal contains 36 locks and encompasses a total elevation differential of...

project was one such example where Irishmen were many of the laborers. Small but tight communities developed in growing cities such as Philadelphia, Boston

Boston

Boston is the capital of and largest city in Massachusetts, and is one of the oldest cities in the United States. The largest city in New England, Boston is regarded as the unofficial "Capital of New England" for its economic and cultural impact on the entire New England region. The city proper had...

, New York

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

and Providence

Providence, Rhode Island

Providence is the capital and most populous city of Rhode Island and was one of the first cities established in the United States. Located in Providence County, it is the third largest city in the New England region...

.

From 1820 to 1860, 1,956,557 Irish arrived, 75% of these after the Great Irish Famine (or The Great Hunger) of 1845–1852, struck. The Famine hurt Irish men and women alike, especially those poorest or without land. It altered the family structures of Ireland because fewer people could afford to marry and raise children, causing many to adopt a single lifestyle. Consequently, many Irish citizens were less bound to family obligations and could more easily migrate to the United States in the following decade.

Of the total Irish migrants

Irish diaspora

thumb|Night Train with Reaper by London Irish artist [[Brian Whelan]] from the book Myth of Return, 2007The Irish diaspora consists of Irish emigrants and their descendants in countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, Argentina, New Zealand, Mexico, South Africa,...

to the U.S. from 1820 to 1860, many died crossing the ocean due to disease and dismal conditions of what became known as coffin ship

Coffin ship

Coffin ship is the name given to any boat that has been overinsured and is therefore worth more to its owners sunk than afloat. These were hazardous places to work in the days before effective maritime safety regulation. They were generally eliminated in the 1870s with the success of reforms...

s.

Baltimore

Baltimore is the largest independent city in the United States and the largest city and cultural center of the US state of Maryland. The city is located in central Maryland along the tidal portion of the Patapsco River, an arm of the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore is sometimes referred to as Baltimore...

, Detroit

Detroit, Michigan

Detroit is the major city among the primary cultural, financial, and transportation centers in the Metro Detroit area, a region of 5.2 million people. As the seat of Wayne County, the city of Detroit is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan and serves as a major port on the Detroit River...

, Chicago

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

, St. Louis

St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis is an independent city on the eastern border of Missouri, United States. With a population of 319,294, it was the 58th-largest U.S. city at the 2010 U.S. Census. The Greater St...

, San Francisco, and Los Angeles

Los Ángeles

Los Ángeles is the capital of the province of Biobío, in the commune of the same name, in Region VIII , in the center-south of Chile. It is located between the Laja and Biobío rivers. The population is 123,445 inhabitants...

. In 1910, there were more people in New York City of Irish heritage than Dublin's whole population, and even today, many of these cities still retain a substantial Irish American community. Mill towns such as Lawrence

Lawrence, Massachusetts

Lawrence is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States on the Merrimack River. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, the city had a total population of 76,377. Surrounding communities include Methuen to the north, Andover to the southwest, and North Andover to the southeast. It and Salem are...

, Lowell

Lowell, Massachusetts

Lowell is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, USA. According to the 2010 census, the city's population was 106,519. It is the fourth largest city in the state. Lowell and Cambridge are the county seats of Middlesex County...

, and Pawtucket

Pawtucket

Pawtucket may refer to:* Pawtucket, Rhode Island* Pawtucket Falls , Lowell, Massachusetts* Pawtucket tribe* 2 ships named USS Pawtucket* Pawtucket Brewery, fictional brewery on the television series Family Guy...

attracted many Irish women in particular. The best urban economic opportunities for unskilled Irish women and men included “factory and millwork, domestic service, and the physical labor of public work projects.”

Irish women’s initial experiences in the United States were largely shaped by the types of roles they fulfilled in their homeland. Although Irish culture gave more authority to husbands and fathers, it simultaneously recognized female power. In most cases in Ireland, wives handled money within the family, and a large number of them even worked in cities away from the home in domestic work or sales. Although older women asserted this kind of power, daughters were seen as less valuable than sons due to the patriarchal nature of society. As a result, young women had little hesitation in migrating, and their families saved money in order help finance the trip abroad. Limited social and economic opportunities for daughters in Ireland in the second half of the nineteenth century caused a wave of young women to search for better possibilities in the United States. The pull factors of the United States, especially job availability, caused Irish women to view their “journey with optimism, in a forward-looking assessment that in America they could achieve a status that they never could have at home.”

The female exodus of the mid-nineteenth century stands out in American history as the only major group of immigrants that was over fifty percent women. Because of the decrease in marriages in Ireland, single Irish women, called “unprovided-for ‘girls’”, traveled to the United States to find employment and/or start families of their own. Frustrated by the hardships of Irish farm life and alone in a new country without the help of other family members, female immigrants tended to settle in urban areas to find work. Occupational options, such as domestic work, white-collar work, nursing and teaching, granted more authority to young women in the United States than in Ireland. Recognizing their own successes as single women, most decided to postpone marriage and taught their daughters to do the same. In fact, the majority of the most successful Irish women in America never married, and a significant number of them were nuns.

Employment, not marriage, continued to be Irish women’s priority throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, and women outnumbered men in cities and mill towns where they worked in “factory jobs and millwork, domestic service and, later in the century, clerical and shop work.” However, Catholicism preached the centrality of women in the home, and Irish immigrants still respected the Church as the most important institution in their lives. Consequently, Irish women still pursued marriage and bore many children as long as they could meet economic needs. Couples that could not support large families often had many children regardless of their economic status, and due to discrimination against Irish men in the workplace and their tendency to desert their wives, women usually bore the brunt of family responsibility.

After 1860, Irish immigration continued, with another 1,916,547 arriving by 1900, mainly due to family reunification

Family reunification

Family reunification is a recognized reason for immigration in many countries. The presence of one or more family members in a certain country, therefore, enables the rest of the family to immigrate to that country as well....

, mostly to the industrial town and cities where Irish American neighborhoods had previously been established.

During the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, Irish Americans volunteered in high numbers for the Union army, and at least thirty-eight Union regiments had the word "Irish" in their title. However, conscription was resisted by the Irish and others as an imposition on liberty. When the conscription law was passed in 1863, draft riots

New York Draft Riots

The New York City draft riots were violent disturbances in New York City that were the culmination of discontent with new laws passed by Congress to draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War. The riots were the largest civil insurrection in American history apart from the Civil War itself...

erupted in New York. The New York draft coincided with the efforts of Tammany Hall to enroll Irish immigrants as citizens so they could vote in local elections. Many such immigrants suddenly discovered they were now expected to fight for their new country. The Irish, employed primarily as laborers, were usually unable to afford the $300 as a "commutation fee" to procure exemption from service, while more established New Yorkers receiving better pay were able to hire substitutes and avoid the draft. Many of the recent immigrants viewed freed slaves as competition for scarce jobs, and as the reason why the Civil War was being fought. African Americans who fell into the mob's hands were often beaten, tortured, or killed, including one man, William Jones, who was attacked by a crowd of 400 with clubs and paving stones, then hung from a tree and set alight.

The Colored Orphan Asylum on Fifth Avenue, which provided shelter for hundreds of children, was attacked by a mob, although the largely Irish-American police force was able to secure the orphanage for enough time to allow orphans to escape.

In 1871, New York's Orange Riots

Orange Riots

The Orange riots took place in Manhattan, New York City in 1870 and 1871, and involved violent conflict between Irish Protestants, called "Orangemen", and Irish Catholics, along with the New York City Police Department and the New York State National Guard....

were incited by Irish Protestants celebrating the Battle of the Boyne

Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne was fought in 1690 between two rival claimants of the English, Scottish and Irish thronesthe Catholic King James and the Protestant King William across the River Boyne near Drogheda on the east coast of Ireland...

with parades through predominantly Catholic neighborhoods. 63 citizens, mostly Irish Catholics, were massacred in the resulting police-action.

Language

Irish immigrants fell into three linguistic categories: monolingual IrishIrish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

speakers, bilingual speakers of both Irish and English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

, and monolingual English speakers. Estimates indicate that there were around 400,000 Irish speakers in the United States in the 1890s, located primarily in New York City

New York City

New York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

, Philadelphia, Boston

Boston

Boston is the capital of and largest city in Massachusetts, and is one of the oldest cities in the United States. The largest city in New England, Boston is regarded as the unofficial "Capital of New England" for its economic and cultural impact on the entire New England region. The city proper had...

, Chicago

Chicago

Chicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

and Yonkers. The Irish speaking population of New York reached its height in this period, when speakers of Irish numbered between 70,000 and 80,000. This number declined during the early 20th century, dropping to 40,000 in 1939, 10,000 in 1979 and 5,000 in 1995. According to the latest census, the Irish language ranks 66th out of the 322 languages spoken today in the U.S., with over 25,000 speakers. New York State has the most Irish Gaelic speakers, and Massachusetts the highest percentage, of the 50 states. Daltaí na Gaeilge

Daltaí na Gaeilge

Daltaí na Gaeilge is an organization that operates Irish language immersion programs in the American states of New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. It also serves as a resource for Irish language students from across the English-speaking world to connect with qualified instructors.The...

, a nonprofit Gaelic language advocacy group based in Elberon, New Jersey

Elberon, New Jersey

Elberon is an unincorporated area that is part of Long Branch in Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States. The area is served as United States Postal Service ZIP code 07740....

, estimated that about 30,000 speak the language as of 2006. This, the organization claimed, has seen an increase from only a few thousand at the time of its founding in 1981.

Occupations

Before 1800 Irish Protestant immigrants became farmers; many headed to the frontier where land was cheap or free and it was easier to start a farm or herding operation.After 1840 most Irish Catholic immigrants went directly to the cities, mill towns, and railroad or canal construction sites in the east coast. In upstate New York, the Great Lakes area, the Midwest and the Far West, many became farmers or ranchers. In the East, male Irish laborers were hired by Irish contractors to work on canals, railroads, streets, sewers and other construction projects, particularly in New York state

New York

New York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

and New England

New England

New England is a region in the northeastern corner of the United States consisting of the six states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut...

. Large numbers moved to New England mill towns, such as Holyoke

Holyoke, Massachusetts