Polish culture during World War II

Encyclopedia

Polish culture during World War II

was suppressed by the occupying powers of Nazi Germany

and the Soviet Union

, both of whom were hostile to Poland

's people

and cultural heritage. Policies aimed at cultural genocide

resulted in the deaths of thousands of scholars and artists, and the theft and destruction of innumerable cultural artifacts. The "maltreatment of the Poles was one of many ways in which the Nazi and Soviet regimes had grown to resemble one another", wrote British historian Niall Ferguson

.

The occupiers looted and destroyed much of Poland's cultural and historical heritage, while persecuting and murdering members of the Polish cultural elite

. Most Polish schools

were closed, and those that remained open saw their curricula

altered significantly.

Nevertheless, underground organizations and individuals – in particular the Polish Underground State – saved much of Poland's most valuable cultural treasures, and worked to salvage as many cultural institutions and artifacts as possible. The Catholic Church and wealthy individuals contributed to the survival of some artists and their works. Despite severe retribution by the Nazis and Soviets, Polish underground cultural activities, including publications, concerts, live theater, education, and academic research, continued throughout the war.

nation and throughout the 18th century remained partitioned

by degrees between Prussian, Austrian and Russian empires. Not until the end of World War I was independence restored

and the nation reunited, although the drawing of boundary lines was, of necessity, a contentious issue

. Independent Poland lasted for only 21 years before it was again attacked and divided among foreign powers.

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland, initiating World War II

, and on 17 September, pursuant to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

, Poland was invaded by the Soviet Union

. Subsequently Poland was partitioned again – between these two powers – and remained under their occupation for most of the war. By 1 October, Germany and the Soviet Union had completely overrun Poland, although the Polish government never formally surrendered, and the Polish Underground State, subordinate to the Polish government-in-exile, was soon formed. On 8 October, Nazi Germany annexed the western areas of pre-war Poland

and, in the remainder of the occupied area, established the General Government

. The Soviet Union had to temporarily give up the territorial gains it made in 1939 due to the German invasion of the Soviet Union

, but permanently re-annexed them after winning them back in mid-1944. Over the course of the war, Poland lost over 20% of its pre-war population amid an occupation that marked the end of the Second Polish Republic

.

. The basic policy was outlined by the Berlin Office of Racial Policy

in a document titled Concerning the Treatment of the Inhabitants of the Former Polish Territories, from a Racial-Political Standpoint. Slavic people living east of the pre-war German border were to be Germanized, enslaved

or eradicated, depending on whether they lived in the territories directly annexed into the German state or in the General Government

.

Much of the German policy on Polish culture was formulated during a meeting between the governor of the General Government, Hans Frank

, and Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels

, at Łódź on 31 October 1939. Goebbels declared that "The Polish nation is not worthy to be called a cultured nation". He and Frank agreed that opportunities for the Poles to experience their culture should be severely restricted: no theaters, cinemas or cabarets; no access to radio or press; and no education. Frank suggested that the Poles should periodically be shown films highlighting the achievements of the Third Reich and should eventually be addressed only by megaphone

. During the following weeks Polish schools beyond middle vocational levels were closed, as were theaters and many other cultural institutions. The only Polish-language

newspaper published in occupied Poland was also closed, and the arrests of Polish intellectuals began.

In March 1940, all cultural activities came under the control of the General Government's Department of People's Education and Propaganda (Abteilung für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda), whose name was changed a year later to the "Chief Propaganda Department" (Hauptabteilung Propaganda). Further directives issued in the spring and early summer reflected policies that had been outlined by Frank and Goebbels during the previous autumn. One of the Department's earliest decrees prohibited the organization of all but the most "primitive" of cultural activities without the Department's prior approval. Spectacles of "low quality", including those of an erotic or pornographic nature, were however an exception—those were to be popularized to appease the population and to show the world the "real" Polish culture as well as to create the impression that Germany was not preventing Poles from expressing themselves. German propaganda specialists invited critics from neutral countries to specially organized "Polish" performances that were specifically designed to be boring or pornographic, and presented them as typical Polish cultural activities. Polish-German cooperation in cultural matters, such as joint public performances, was strictly prohibited. Meanwhile, a compulsory registration scheme for writers and artists was introduced in August 1940. Then, in October, the printing of new Polish-language books was prohibited; existing titles were censored, and often confiscated and withdrawn.

In 1941, German policy evolved further, calling for the complete destruction of the Polish people

, whom the Nazis regarded as "subhuman" (Untermensch

en). Within ten to twenty years, the Polish territories under German occupation were to be entirely cleared of ethnic Poles and settled by German colonists

.

The policy was relaxed somewhat in the final years of occupation (1943–44), in view of German military defeats and the approaching Eastern Front. The Germans hoped that a more lenient cultural policy would lessen unrest and weaken the Polish Resistance. Poles were allowed back into those museums that now supported German propaganda and indoctrination, such as the newly created Chopin museum, which emphasized the composer's invented German roots. Restrictions on education, theater and music performances were eased.

Given that the Second Polish Republic

was a multicultural state, German policies and propaganda also sought to create and encourage conflicts between ethnic groups, fueling tension between Poles and Jews, and between Poles and Ukrainians. In Łódź, the Germans forced Jews to help destroy a monument to a Polish hero, Tadeusz Kościuszko

, and filmed them committing the act. Soon afterward, the Germans set fire to a Jewish synagogue

and filmed Polish bystanders, portraying them in propaganda releases as a "vengeful mob." This divisive policy was reflected in the Germans' decision to destroy Polish education, while at the same time, showing relative tolerance toward the Ukrainian school system. As the high-ranking Nazi official

Erich Koch

explained, "We must do everything possible so that when a Pole meets a Ukrainian, he will be willing to kill the Ukrainian and conversely, the Ukrainian will be willing to kill the Pole."

, Einsatzgruppen

units, who were responsible for art, and by experts of Haupttreuhandstelle Ost, who were responsible for more mundane objects. Notable items plundered by the Nazis included the Altar of Veit Stoss

and paintings by Raphael

, Rembrandt, Leonardo da Vinci

, Canaletto

and Bacciarelli

. Most of the important art pieces had been "secured" by the Nazis within six months of September 1939; by the end of 1942, German officials estimated that "over 90%" of the art previously in Poland was in their possession. Some art was shipped to German museums, such as the planned Führermuseum

in Linz

, while other art became the private property of Nazi officials. Over 516,000 individual art pieces were taken, including 2,800 paintings by European painters; 11,000 works by Polish painters; 1,400 sculptures, 75,000 manuscripts, 25,000 maps, and 90,000 books (including over 20,000 printed before 1800); as well as hundreds of thousands of other objects of artistic and historic value. Even exotic animals were taken from the zoo

s.

" (For Germans Only). Twenty-five museums and a host of other institutions were destroyed during the war. According to one estimate, by war's end 43% of the infrastructure of Poland's educational and research institutions and 14% of its museums had been destroyed. According to another, only 105 of pre-war Poland's 175 museums survived the war, and just 33 of these institutions were able to reopen. Of pre-war Poland's 603 scientific institutions, about half were totally destroyed, and only a few survived the war relatively intact.

Many university professors, as well as teachers, lawyers, artists, writers, priests and other members of the Polish intelligentsia

Many university professors, as well as teachers, lawyers, artists, writers, priests and other members of the Polish intelligentsia

were arrested and executed, or transported to concentration camps

, during operations such as AB-Aktion. This particular campaign resulted in the infamous Sonderaktion Krakau

and the massacre of Lwów professors. During World War II Poland lost 39% to 45% of its physicians and dentists, 26% to 57% of its lawyers, 15% to 30% of its teachers, 30% to 40% of its scientists and university professors, and 18% to 28% of its clergy. The Jewish intelligentsia was exterminated altogether. The reasoning behind this policy was clearly articulated by a Nazi gauleiter

: "In my district, [any Pole who] shows signs of intelligence will be shot."

As part of their program to suppress Polish culture, the German Nazis attempted to destroy Christianity

in Poland, with a particular emphasis on the Roman Catholic Church

. In some parts of occupied Poland, Poles were restricted, or even forbidden, from attending religious services. At the same time, church property was confiscated, prohibitions were placed on using the Polish language in religious services, organizations affiliated with the Catholic Church were abolished, and it was forbidden to perform certain religious songs—or to read passages of the Bible

—in public. The worst conditions were found in the Reichsgau Wartheland

, which the Nazis treated as a laboratory for their anti-religious policies. Polish clergy and religious leaders figured prominently among portions of the intelligentsia that were targeted for extermination.

To forestall the rise of a new generation of educated Poles, German officials decreed that the schooling of Polish children would be limited to a few years of elementary education. Reichsführer-SS

Heinrich Himmler

wrote, in a memorandum of May 1940: "The sole purpose of this schooling is to teach them simple arithmetic, nothing above the number 500; how to write one's name; and the doctrine that it is divine law to obey the Germans .... I do not regard a knowledge of reading as desirable." Hans Frank

echoed him: "The Poles do not need universities or secondary schools; the Polish lands are to be converted into an intellectual desert." The situation was particularly dire in the former Polish territories beyond the General Government

, which had been annexed to the Third Reich

. The specific policy varied from territory to territory, but in general, there was no Polish-language education at all. German policy constituted a crash-Germanization of the populace. Polish teachers were dismissed, and some were invited to attend "orientation" meetings with the new administration, where they were either summarily arrested or executed on the spot. Some Polish schoolchildren were sent to German schools, while others were sent to special schools where they spent most of their time as unpaid laborers, usually on German-run farms; speaking Polish brought severe punishment. It was expected that Polish children would begin to work

once they finished their primary education at age 12 to 15. In the eastern territories not included in the General Government (Bezirk Bialystok

, Reichskommissariat Ostland

and Reichskommissariat Ukraine

) many primary schools were closed, and most education was conducted in non-Polish languages such as Ukrainian, Belorussian, and Lithuanian. In the Bezirk Bialystok region, for example, 86% of the schools that had existed before the war were closed down during the first two years of German occupation, and by the end of the following year that figure had increased to 93%.

The state of Polish primary schools was somewhat better in the General Government

The state of Polish primary schools was somewhat better in the General Government

, though by the end of 1940, only 30% of prewar schools were operational, and only 28% of prewar Polish children attended them. A German police memorandum

of August 1943 described the situation as follows:

In the General Government, the remaining schools were subjugated to the German educational system, and the number and competence of their Polish staff was steadily scaled down. All universities and most secondary schools were closed, if not immediately after the invasion, then by mid-1940. By late 1940, no official Polish educational institutions more advanced than a vocational school

remained in operation, and they offered nothing beyond the elementary trade and technical training required for the Nazi economy. Primary schooling was to last for seven years, but the classes in the final two years of the program were to be limited to meeting one day per week. There was no money for heating of the schools in winter. Classes and schools were to be merged, Polish teachers dismissed, and the resulting savings used to sponsor the creation of schools for children of the German minority or to create barracks for German troops. No new Polish teachers were to be trained. The educational curriculum

was censored; subjects such as literature, history and geography were removed. Old textbooks were confiscated and school libraries were closed. The new educational aims for Poles included convincing them that their national fate was hopeless, and teaching them to be submissive and respectful to Germans. This was accomplished through deliberate tactics such as police raids on schools, police inspections of student belongings, mass arrests of students and teachers, and the use of students as forced laborers, often by transporting them to Germany as seasonal workers.

The Germans were especially active in the destruction of Jewish culture in Poland; nearly all of the wooden synagogue

The Germans were especially active in the destruction of Jewish culture in Poland; nearly all of the wooden synagogue

s there were destroyed. Moreover, the sale of Jewish literature

was banned throughout Poland.

Polish literature

faced a similar fate in territories annexed by Germany, where the sale of Polish books was forbidden. The public destruction of Polish books was not limited to those seized from libraries, but also included those books that were confiscated from private homes. The last Polish book titles not already proscribed were withdrawn in 1943; even Polish prayer books were confiscated. Soon after the occupation began, most libraries were closed; in Kraków, about 80% of the libraries were closed immediately, while the remainder saw their collections decimated by censors. The occupying powers destroyed Polish book collections, including the Sejm

and Senate

Library, the Przedziecki Estate Library, the Zamoyski Estate Library, the Central Military Library, and the Rapperswil Collection. In 1941, the last remaining Polish public library in the German-occupied territories was closed in Warsaw

. During the war, Warsaw libraries lost about a million volumes, or 30% of their collections. More than 80% of these losses were the direct result of purges rather than wartime conflict. Overall, it is estimated that about 10 million volumes from state-owned libraries and institutions perished during the war.

Polish flags and other symbols were confiscated. The war on the Polish language included the tearing down of signs in Polish and the banning of Polish speech in public places. Persons who spoke Polish in the streets were often insulted and even physically assaulted. The Germanization of place names prevailed. Many treasures of Polish culture – including memorials, plaques and monuments to national heroes (e.g., Kraków's Adam Mickiewicz monument

) – were destroyed. In Toruń

, all Polish monuments and plaques were torn down. Dozens of monuments were destroyed throughout Poland. The Nazis planned to level entire cities

.

The Germans prohibited publication of any regular Polish-language book, literary study or scholarly paper. In 1940, several German-controlled printing houses began operating in occupied Poland, publishing items such as Polish-German dictionaries and antisemitic and anticommunist novels. An aim of German propaganda was to rewrite Polish history: studies were published and exhibitions were held, claiming that Polish lands were in reality Germanic; that famous Poles, including Nicolaus Copernicus

The Germans prohibited publication of any regular Polish-language book, literary study or scholarly paper. In 1940, several German-controlled printing houses began operating in occupied Poland, publishing items such as Polish-German dictionaries and antisemitic and anticommunist novels. An aim of German propaganda was to rewrite Polish history: studies were published and exhibitions were held, claiming that Polish lands were in reality Germanic; that famous Poles, including Nicolaus Copernicus

, Veit Stoss

and Chopin, were ethnic Germans.

Censorship

at first targeted books that were considered to be "serious", including scientific and educational texts and texts that were thought to promote Polish patriotism; only fiction that was free of anti-German overtones was permitted. Banned literature included maps, atlases and English

- and French-language

publications, including dictionaries. Several non-public indexes of prohibited books were created, and over 1,500 Polish writers were declared "dangerous to the German state and culture". The index of banned authors included such Polish authors as Adam Mickiewicz

, Juliusz Słowacki, Stanisław Wyspiański, Bolesław Prus, Stefan Żeromski

, Józef Ignacy Kraszewski

, Władysław Reymont, Stanisław Wyspiański, Julian Tuwim

, Kornel Makuszyński

, Leopold Staff

, Eliza Orzeszkowa

and Maria Konopnicka

. Mere possession of such books was illegal and punishable by imprisonment. Door-to-door sale of books was banned, and bookstores—which required a license to operate—were either emptied out or closed.

Poles were forbidden, under penalty of death, to own radios. The press was reduced from over 2,000 publications to a few dozen, all censored

Poles were forbidden, under penalty of death, to own radios. The press was reduced from over 2,000 publications to a few dozen, all censored

by the Germans. All pre-war newspapers were closed, and the few that were published during the occupation were new creations under the total control of the Germans. Such a thorough destruction of the press was unprecedented in contemporary history. The only officially available reading matter was the propaganda

press that was disseminated by the German occupation administration. Cinemas, now under the control of the German propaganda machine, saw their programming dominated by Nazi German movies, which were preceded by propaganda newsreel

s. The few Polish films permitted to be shown (about 20% of the total programming) were edited to eliminate references to Polish national symbols as well as Jewish actors and producers. Several propaganda films were shot in Polish, although no Polish films were shown after 1943. As all profits from Polish cinemas were officially directed toward German war production, attendance was discouraged by the Polish underground; a famous underground slogan declared: "Tylko świnie siedzą w kinie" ("Only pigs attend the movies"). A similar situation faced theaters, which were forbidden by the Germans to produce "serious" spectacles. Indeed, a number of propaganda pieces were created for theater stages. Hence, theatrical productions were also boycotted by the underground. In addition, actors were discouraged from performing in them and warned that they would be labeled as collaborators if they failed to comply. Ironically, restrictions on cultural performances were eased in Jewish ghetto

s, given that the Germans wished to distract ghetto inhabitants and prevent them from grasping their eventual fate

.

Music was the least restricted of cultural activities, probably because Hans Frank regarded himself as a fan of serious music. In time, he ordered the creation of the Orchestra and Symphony of the General Government in its capital, Kraków

. Numerous musical performances were permitted in cafes and churches, and the Polish underground chose to boycott only the propagandist opera

s. Visual artists, including painters and sculptors, were compelled to register with the German government; but their work was generally tolerated by the underground, unless it conveyed propagandist themes. Shuttered museums were replaced by occasional art exhibitions that frequently conveyed propagandist themes.

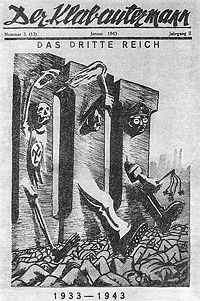

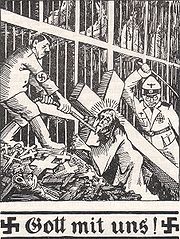

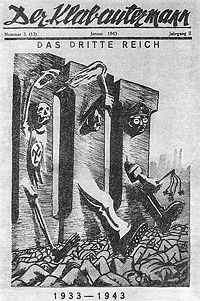

The development of Nazi propaganda

in occupied Poland can be divided into two main phases. Initial efforts were directed towards creating a negative image of pre-war Poland, and later efforts were aimed at fostering anti-Soviet, antisemitic, and pro-German attitudes.

(beginning 17 September 1939) that followed the German invasion

that had marked the start of World War II (beginning 1 September 1939), the Soviet Union

annexed the eastern parts

("Kresy

") of the Second Polish Republic

, comprising 201015 square kilometres (77,612 sq mi) and a population of 13.299 million. Hitler and Stalin shared the goal of obliterating Poland's political and cultural life, so that Poland would, according to historian Niall Ferguson, "cease to exist not merely as a place, but also as an idea".

The Soviet authorities regarded service to the prewar Polish state as a "crime against revolution" and "counter-revolutionary activity" and arrested many members of the Polish intelligentsia

The Soviet authorities regarded service to the prewar Polish state as a "crime against revolution" and "counter-revolutionary activity" and arrested many members of the Polish intelligentsia

, politicians, civil servants and academics, as well as ordinary persons suspected of posing a threat to Soviet rule. More than a million Polish citizens were deported to Siberia, many to Gulag

concentration camps, for years or decades. Others died, including over 20,000 military officers who perished in the Katyn massacre

s.

The Soviets quickly Sovietized

the annexed lands, introducing compulsory collectivization. They proceeded to confiscate, nationalize and redistribute private and state-owned Polish property. In the process, they banned political parties and public associations and imprisoned or executed their leaders as "enemies of the people". In line with Soviet anti-religious policy

, churches and religious organizations were persecuted. On 10 February 1940, the NKVD unleashed a campaign of terror against "anti-Soviet" elements in occupied Poland. The Soviets' targets included persons who often traveled abroad, persons involved in overseas correspondence, Esperantists

, philatelists, Red Cross workers, refugees, smugglers, priests and members of religious congregations, the nobility, landowners, wealthy merchants, bankers, industrialists, and hotel and restaurant owners. Stalin, like Hitler, strove to decapitate Polish society.

The Soviet authorities sought to remove all trace of the Polish history of the area now under their control. The name "Poland" was banned. Polish monuments were torn down. All institutions of the dismantled Polish state, including the Lwów University

, were closed, then reopened, mostly with new Russian directors. Soviet communist ideology became paramount in all teaching. Polish literature and language studies were dissolved by the Soviet authorities, and the Polish language was replaced with Russian or Ukrainian. Polish-language books were burned even in the primary schools. Polish teachers were not allowed in the schools, and many were arrested. Classes were held in Belorussian, Ukrainian and Lithuanian, with a new pro-Soviet curriculum

. As Polish-Canadian historian Piotr Wróbel

noted, citing British historians M. R. D. Foot and I. C. B. Dear

, majority of scholars believe that "In the Soviet occupation zone, conditions were only marginally less harsh than under the Germans." In September 1939, many Polish Jews had fled east; after some months of living under Soviet rule, some of them wanted to return to the German zone of occupied Poland.

All publications and media were subjected to censorship

All publications and media were subjected to censorship

. The Soviets sought to recruit Polish left-wing intellectuals who were willing to cooperate. Soon after the Soviet invasion, the Writers' Association of Soviet Ukraine created a local chapter in Lwów; there was a Polish-language theater and radio station. Polish cultural activities in Minsk

and Wilno

were less organized. These activities were strictly controlled by the Soviet authorities, which saw to it that these activities portrayed the new Soviet regime in a positive light and vilified the former Polish government.

The Soviet propaganda-motivated support for Polish-language cultural activities, however, clashed with the official policy of Russification

. The Soviets at first intended to phase out the Polish language and so banned Polish from schools, street signs, and other aspects of life. This policy was, however, reversed at times—first before the elections in October 1939; and later, after the German conquest of France

. By the late spring of 1940, Stalin, anticipating possible future conflict with the Third Reich, decided that the Poles might yet be useful to him. In the autumn of 1940, the Poles of Lwów observed the 85th anniversary of Adam Mickiewicz

's death. Soon, however, Stalin decided to re-implement the Russification policies. He reversed his decision again, however, when a need arose for Polish-language pro-Soviet propaganda following the German invasion of the Soviet Union; as a result Stalin permitted the creation of Polish forces in the East and later decided to create a communist People's Republic of Poland

.

Many Polish writers collaborated with the Soviets, writing anti-Polish, pro-Soviet propaganda. They included Jerzy Borejsza

, Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński

, Kazimierz Brandys

, Janina Broniewska

, Jan Brzoza, Teodor Bujnicki

, Leon Chwistek

, Zuzanna Ginczanka

, Halina Górska

, Mieczysław Jastrun, Stefan Jędrychowski, Stanisław Jerzy Lec, Tadeusz Łopalewski

, Juliusz Kleiner

, Jan Kott

, Jalu Kurek

, Karol Kuryluk

, Leopold Lewin

, Anatol Mikułko, Jerzy Pański

, Leon Pasternak

, Julian Przyboś

, Jerzy Putrament

, Jerzy Rawicz, Adolf Rudnicki

, Włodzimierz Słobodnik

, Włodzimierz Sokorski

, Elżbieta Szemplińska

, Anatol Stern

, Julian Stryjkowski

, Lucjan Szenwald

, Leopold Tyrmand

, Wanda Wasilewska

, Stanisław Wasilewski, Adam Ważyk

, Aleksander Weintraub

and Bruno Winawer

.

Other Polish writers, however, rejected the Soviet persuasions and instead published underground: Jadwiga Czechowiczówna, Jerzy Hordyński

, Jadwiga Gamska-Łempicka, Herminia Naglerowa

, Beata Obertyńska

, Ostap Ortwin

, Tadeusz Peiper

, Teodor Parnicki

, Juliusz Petry

. Some writers, such as Władysław Broniewski, after collaborating with the Soviets for a few months, joined the anti-Soviet opposition. Similarly, Aleksander Wat

, initially sympathetic to communism, was arrested by the Soviet NKVD

secret police

and exiled to Kazakhstan

.

Polish culture persisted in underground education

Polish culture persisted in underground education

, publications, even theater. The Polish Underground State created a Department of Education and Culture (under Stanisław Lorentz) which, along with a Department of Labor and Social Welfare (under Jan Stanisław Jankowski and, later, Stefan Mateja) and a Department for Elimination of the Effects of War (under Antoni Olszewski and Bronisław Domosławski), became underground patrons of Polish culture. These Departments oversaw efforts to save from looting and destruction works of art in state and private collections (most notably, the giant paintings by Jan Matejko

that were concealed throughout the war). They compiled reports on looted and destroyed works and provided artists and scholars with means to continue their work and their publications and to support their families. Thus, they sponsored the underground publication (bibuła) of works by Winston Churchill

and Arkady Fiedler

and of 10,000 copies of a Polish primary-school primer

and commissioned artists to create resistance artwork (which was then disseminated by Operation N and like activities). Also occasionally sponsored were secret art exhibitions, theater performances and concerts.

Other important patrons of Polish culture included the Roman Catholic Church and Polish aristocrats, who likewise supported artists and safeguarded Polish heritage (notable patrons included Cardinal Adam Stefan Sapieha

and a former politician, Janusz Radziwiłł). Some private publishers, including Stefan Kamieński, Zbigniew Mitzner and the Ossolineum

publishing house, paid writers for books that would be delivered after the war.

. Most notably, the Secret Teaching Organization

(Tajna Organizacja Nauczycielska, TON) was created as early as in October 1939. Other organizations were created locally; after 1940 they were increasingly subordinated and coordinated by the TON, working closely with the Underground's State Department of Culture and Education, which was created in autumn 1941 and headed by Czesław Wycech, creator of the TON. Classes were either held under the cover of officially permitted activities or in private homes and other venues. By 1942, about 1,500,000 students took part in underground primary education; in 1944, its secondary school system covered 100,000 people, and university level courses were attended by about 10,000 students (for comparison, the pre-war enrollment at Polish universities was about 30,000 for the 1938/1939 year). More than 90,000 secondary-school pupils attended underground classes held by nearly 6,000 teachers between 1943 and 1944 in four districts of the General Government

(centered around the cities of Warsaw

, Kraków

, Radom

and Lublin

). Overall, in that period in the General Government, one of every three children was receiving some sort of education from the underground organizations; the number rose to about 70% for children old enough to attend secondary school. It is estimated that in some rural areas, the educational coverage was actually improved (most likely as courses were being organized in some cases by teachers escaped or deported from the cities). Compared to pre-war classes, the absence of Polish Jewish students was notable, as they were confined by the Nazi Germans to ghettos; there was, however, underground Jewish education in the ghettos, often organized with support from Polish organizations like TON. Students at the underground schools were often also members of the Polish resistance.

In Warsaw

In Warsaw

, there were over 70 underground schools, with 2,000 teachers and 21,000 students. Underground Warsaw University educated 3,700 students, issuing 64 masters and 7 doctoral degrees. Warsaw Politechnic under occupation educated 3,000 students, issuing 186 engineering degrees, 18 doctoral ones and 16 habilitation

s. Jagiellonian University

issued 468 masters and 62 doctoral degrees, employed over 100 professors and teachers, and served more than 1,000 students per year. Throughout Poland, many other universities and institutions of higher education (of music, theater, arts, and others) continued their classes throughout the war.

Even some academic research was carried out (for example, by Władysław Tatarkiewicz, a leading Polish philosopher, and Zenon Klemensiewicz

, a linguist). Nearly 1,000 Polish scientists received funds from the Underground State, enabling them to continue their research.

The German attitude to underground education varied depending on whether it took place in the General Government or the annexed territories. The Germans had almost certainly realized the full scale of the Polish underground education system by about 1943, but lacked the manpower to put an end to it, probably prioritizing resources to dealing with the armed resistance. For the most part, closing underground schools and colleges in the General Government was not a top priority for the Germans. In 1943 a German report on education admitted that control of what was being taught in schools, particularly rural ones, was difficult, due to lack of manpower, transportation, and the activities of the Polish resistance. Some schools semi-openly taught unauthorized subjects in defiance of the German authorities. Hans Frank

noted in 1944 that although Polish teachers were a "mortal enemy" of the German states, they could not all be disposed of immediately. It was perceived as a much more serious issue in the annexed territories, as it hindered the process of Germanization; involvement in the underground education in those territories was much more likely to result in a sentence to a concentration camp.

Print

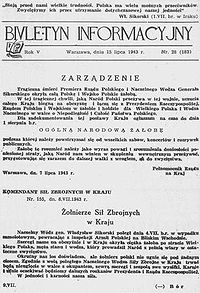

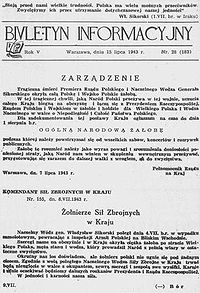

There were over 1,000 underground newspapers; among the most important were the Biuletyn Informacyjny

There were over 1,000 underground newspapers; among the most important were the Biuletyn Informacyjny

of Armia Krajowa

and Rzeczpospolita of the Government Delegation for Poland. In addition to publication of news (from intercepted Western radio transmissions), there were hundreds of underground publications dedicated to politics, economics, education, and literature (for example, Sztuka i Naród

). The highest recorded publication volume was an issue of Biuletyn Informacyjny printed in 43,000 copies; average volume of larger publication was 1,000–5,000 copies. The Polish underground also published booklets and leaflets from imaginary anti-Nazi German organizations

aimed at spreading disinformation and lowering morale among the Germans. Books were also sometimes printed. Other items were also printed, such as patriotic posters or fake German administration posters, ordering the Germans to evacuate Poland or telling Poles to register household cats.

The two largest underground publishers were the Bureau of Information and Propaganda

of Armia Krajowa and the Government Delegation for Poland. Tajne Wojskowe Zakłady Wydawnicze (Secret Military Publishing House) of Jerzy Rutkowski

(subordinated to the Armia Krajowa) was probably the largest underground publisher in the world. In addition to Polish titles, Armia Krajowa also printed false German newspapers designed to decrease morale of the occupying German forces (as part of Action N

). The majority of Polish underground presses were located in occupied Warsaw; until the Warsaw Uprising

in the summer of 1944 the Germans found over 16 underground printing presses (whose crews were usually executed or sent to concentration camps). The second largest center for Polish underground publishing was Kraków

. There, writers and editors faced similar dangers: for example, almost the entire editorial staff of the underground satirical paper Na Ucho was arrested, and its chief editors were executed in Kraków on 27 May 1944. (Na Ucho was the longest published Polish underground paper devoted to satire

; 20 issues were published starting in October 1943.) The underground press was supported by a large number of activists; in addition to the crews manning the printing presses, scores of underground couriers distributed the publications. According to some statistics, these couriers were among the underground members most frequently arrested by the Germans.

Under German occupation, the professions of Polish journalists and writers were virtually eliminated, as they had little opportunity to publish their work. The Underground State's Department of Culture sponsored various initiatives and individuals, enabling them to continue their work and aiding in their publication. Novels and anthologies were published by underground presses; over 1,000 works were published underground over the course of the war. Literary discussions were held, and prominent writers of the period working in Poland included, among others, Krzysztof Kamil Baczyński

, Leslaw Bartelski

, Tadeusz Borowski

, Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński

, Maria Dąbrowska

, Tadeusz Gajcy

, Zuzanna Ginczanka

, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, future Nobel Prize

winner Czesław Miłosz, Zofia Nałkowska, Jan Parandowski

, Leopold Staff

, Kazimierz Wyka

, and Jerzy Zawiejski. Writers wrote about the difficult conditions in the prisoner-of-war camps (Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński, Stefan Flukowski

, Leon Kruczkowski

, Andrzej Nowicki

and Marian Piechała), the ghetto

s, and even from inside the concentration camps (Jan Maria Gisges

, Halina Gołczowa, Zofia Górska (Romanowiczowa), Tadeusz Hołuj, Kazimierz Andrzej Jaworski

and Marian Kubicki). Many writers did not survive the war, among them Krzysztof Kamil Baczyński, Wacław Berent, Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński, Tadeusz Gajcy, Zuzanna Ginczanka, Juliusz Kaden-Bandrowski

, Stefan Kiedrzyński

, Janusz Korczak

, Halina Krahelska

, Tadeusz Hollender

, Witold Hulewicz

, Ferdynand Antoni Ossendowski

, Włodzimierz Pietrzak, Leon Pomirowski, Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer

and Bruno Schulz

.

With the censorship of Polish theater (and the virtual end of the Polish radio and film industry), underground theaters were created, primarily in Warsaw and Kraków, with shows presented in various underground venues. Beginning in 1940 the theaters were coordinated by the Secret Theatrical Council. Four large companies and more than 40 smaller groups were active throughout the war, even in the Gestapo's Pawiak

With the censorship of Polish theater (and the virtual end of the Polish radio and film industry), underground theaters were created, primarily in Warsaw and Kraków, with shows presented in various underground venues. Beginning in 1940 the theaters were coordinated by the Secret Theatrical Council. Four large companies and more than 40 smaller groups were active throughout the war, even in the Gestapo's Pawiak

prison in Warsaw and in Auschwitz

; underground acting schools were also created. Underground actors, many of whom officially worked mundane jobs, included Karol Adwentowicz

, Elżbieta Barszczewska

, Henryk Borowski

, Wojciech Brydziński

, Władysław Hańcza, Stefan Jaracz

, Tadeusz Kantor

, Mieczysław Kotlarczyk, Bohdan Korzeniowski, Jan Kreczmar

, Adam Mularczyk

, Andrzej Pronaszko

, Leon Schiller

, Arnold Szyfman

, Stanisława Umińska

, Edmund Wierciński

, Maria Wiercińska, Karol Wojtyła (who later became Pope John Paul II

), Marian Wyrzykowski

, Jerzy Zawiejski and others. Theater was also active in the Jewish ghettos and in the camps for Polish war prisoners.

Polish music, including orchestras, also went underground. Top Polish musicians and directors (Adam Didur, Zbigniew Drzewiecki

, Jan Ekier

, Barbara Kostrzewska

, Zygmunt Latoszewski

, Jerzy Lefeld

, Witold Lutosławski, Andrzej Panufnik

, Piotr Perkowski

, Edmund Rudnicki, Eugenia Umińska

, Jerzy Waldorff

, Kazimierz Wiłkomirski, Maria Wiłkomirska, Bolesław Woytowicz, Mira Zimińska

) performed in restaurants, cafes, and private homes, with the most daring singing patriotic ballads

on the streets while evading German patrols. Patriotic songs were written, such as Siekiera, motyka

, the most popular song of occupied Warsaw. Patriotic puppet shows were staged. Jewish musicians (e.g. Władysław Szpilman) and artists likewise performed in ghettos and even in concentration camps. Although many of them died, some survived abroad, like Alexandre Tansman

in the United States, and Eddie Rosner

and Henryk Wars

in the Soviet Union.

Visual arts were also practiced underground. Cafes, restaurants and private homes were turned into galleries or museums; some were closed, with their owners, staff and patrons harassed, arrested or even executed. Polish underground artists included Eryk Lipiński

, Stanisław Miedza-Tomaszewski, Stanisław Ostoja-Chrostowski, and Konstanty Maria Sopoćko

. Some artists worked directly for the Underground State, forging

money and documents, and creating anti-Nazi art (satirical poster

s and caricature

s) or Polish patriotic symbols (for example kotwica

). These works were reprinted on underground presses, and those intended for public display were plastered to walls or painted on them as graffiti

. Many of these activities were coordinated under the Action N

Operation of Armia Krajowa's Bureau of Information and Propaganda

. In 1944 three giant (6 m, or 20 ft) puppets, caricatures of Hitler and Benito Mussolini

, were successfully displayed in public places in Warsaw. Some artists recorded life and death in occupied Poland; despite German bans on Poles using cameras, photographs and even films were taken. Although it was impossible to operate an underground radio station, underground auditions were recorded and introduced into German radios or loudspeaker systems. Underground postage stamps were designed and issued. Since the Germans also banned Polish sport activities, underground sport clubs were created; underground football matches and even tournaments were organized in Warsaw, Kraków and Poznań, although these were usually dispersed by the Germans. All of these activities were supported by the Underground State's Department of Culture.

, the Home Army's Bureau of Information and Propaganda even created three newsreel

s and over 30000 metres (98,425 ft) of film documenting the struggle.

Eugeniusz Lokajski

took some 1,000 photographs before he died; Sylwester Braun

some 3,000, of which 1,500 survive; Jerzy Tomaszewski some 1,000, of which 600 survived.

, based in Britain with the Polish Armed Forces in the West

wrote about the 303 Polish Fighter Squadron

. Melchior Wańkowicz

wrote about the Polish contribution to the capture of Monte Cassino

in Italy. Other writers working abroad included Jan Lechoń

, Antoni Słonimski, Kazimierz Wierzyński

and Julian Tuwim

. There were artists who performed for the Polish forces in the West as well as for the Polish forces in the East. Among musicians who performed for the Polish II Corps

in a Polska Parada cabaret were Henryk Wars

and Irena Anders

. The most famous song of the soldiers fighting under the Allies was the Czerwone maki na Monte Cassino

(The Red Poppies on Monte Cassino), composed by Feliks Konarski

and Alfred Schultz in 1944. There were also Polish theaters in exile in both the East and the West. Several Polish painters, mostly soldiers of the Polish II Corps, kept working throughout the war, including Tadeusz Piotr Potworowski, Adam Kossowski

, Marian Kratochwil, Bolesław Leitgeber and Stefan Knapp

.

wrote in God's Playground

: "In 1945, as a prize for untold sacrifices, the attachment of the survivors to their native culture was stronger than ever before." Similarly, close-knit underground classes, from primary schools to universities, were renowned for their high quality, due in large part to the lower ratio of students to teachers. The resulting culture was, however, different from the culture of interwar Poland for a number of reasons. The destruction of Poland's Jewish community

, Poland's postwar territorial changes

, and postwar migrations left Poland without its historic ethnic minorities. The multicultural nation was no more.

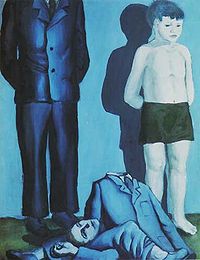

The experience of World War II placed its stamp on a generation

The experience of World War II placed its stamp on a generation

of Polish artists that became known as the "Generation of Columbuses

". The term denotes an entire generation of Poles, born soon after Poland regained independence in 1918, whose adolescence was marked by World War II. In their art, they "discovered a new Poland"–one forever changed by the atrocities of World War II and the ensuing creation of a communist Poland.

Over the years, nearly three-quarters of the Polish people have emphasized the importance of World War II to the Polish national identity. Many Polish works of art created since the war have centered around events of the war. Books by Tadeusz Borowski

, Adolf Rudnicki

, Henryk Grynberg

, Miron Białoszewski, Hanna Krall

and others; films, including those by Andrzej Wajda

(A Generation

, Kanał, Ashes and Diamonds

, Lotna

, A Love in Germany, Korczak, Katyń

); TV series (Four Tank Men and a Dog

and Stakes Larger than Life

); music (Powstanie Warszawskie

); and even comic book

s–all of these diverse works have reflected those times. Polish historian Tomasz Szarota

wrote in 1996:

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

was suppressed by the occupying powers of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, both of whom were hostile to Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

's people

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

and cultural heritage. Policies aimed at cultural genocide

Cultural genocide

Cultural genocide is a term that lawyer Raphael Lemkin proposed in 1933 as a component to genocide. The term was considered in the 1948 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples juxtaposed next to the term ethnocide, but it was removed in the final document, replaced with...

resulted in the deaths of thousands of scholars and artists, and the theft and destruction of innumerable cultural artifacts. The "maltreatment of the Poles was one of many ways in which the Nazi and Soviet regimes had grown to resemble one another", wrote British historian Niall Ferguson

Niall Ferguson

Niall Campbell Douglas Ferguson is a British historian. His specialty is financial and economic history, particularly hyperinflation and the bond markets, as well as the history of colonialism.....

.

The occupiers looted and destroyed much of Poland's cultural and historical heritage, while persecuting and murdering members of the Polish cultural elite

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

. Most Polish schools

Education in Poland

Since changes made in 2009 Education in Poland starts at the age of five or six for the 0 class and six or seven years in the 1st class of primary school . It is compulsory that children do one year of formal education before entering 1st class at no later than 7 years of age...

were closed, and those that remained open saw their curricula

Curriculum

See also Syllabus.In formal education, a curriculum is the set of courses, and their content, offered at a school or university. As an idea, curriculum stems from the Latin word for race course, referring to the course of deeds and experiences through which children grow to become mature adults...

altered significantly.

Nevertheless, underground organizations and individuals – in particular the Polish Underground State – saved much of Poland's most valuable cultural treasures, and worked to salvage as many cultural institutions and artifacts as possible. The Catholic Church and wealthy individuals contributed to the survival of some artists and their works. Despite severe retribution by the Nazis and Soviets, Polish underground cultural activities, including publications, concerts, live theater, education, and academic research, continued throughout the war.

Background

In 1795 Poland ceased to exist as an sovereignSovereign

A sovereign is the supreme lawmaking authority within its jurisdiction.Sovereign may also refer to:*Monarch, the sovereign of a monarchy*Sovereign Bank, banking institution in the United States*Sovereign...

nation and throughout the 18th century remained partitioned

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland or Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth took place in the second half of the 18th century and ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland for 123 years...

by degrees between Prussian, Austrian and Russian empires. Not until the end of World War I was independence restored

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

and the nation reunited, although the drawing of boundary lines was, of necessity, a contentious issue

Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor , also known as Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia , which provided the Second Republic of Poland with access to the Baltic Sea, thus dividing the bulk of Germany from the province of East...

. Independent Poland lasted for only 21 years before it was again attacked and divided among foreign powers.

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland, initiating World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, and on 17 September, pursuant to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

, Poland was invaded by the Soviet Union

Soviet invasion of Poland (1939)

The 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland was a Soviet military operation that started without a formal declaration of war on 17 September 1939, during the early stages of World War II. Sixteen days after Nazi Germany invaded Poland from the west, the Soviet Union did so from the east...

. Subsequently Poland was partitioned again – between these two powers – and remained under their occupation for most of the war. By 1 October, Germany and the Soviet Union had completely overrun Poland, although the Polish government never formally surrendered, and the Polish Underground State, subordinate to the Polish government-in-exile, was soon formed. On 8 October, Nazi Germany annexed the western areas of pre-war Poland

Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany

At the beginning of World War II, nearly a quarter of the pre-war Polish areas were annexed by Nazi Germany and placed directly under German civil administration, while the rest of Nazi occupied Poland was named as General Government...

and, in the remainder of the occupied area, established the General Government

General Government

The General Government was an area of Second Republic of Poland under Nazi German rule during World War II; designated as a separate region of the Third Reich between 1939–1945...

. The Soviet Union had to temporarily give up the territorial gains it made in 1939 due to the German invasion of the Soviet Union

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

, but permanently re-annexed them after winning them back in mid-1944. Over the course of the war, Poland lost over 20% of its pre-war population amid an occupation that marked the end of the Second Polish Republic

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

.

Policy

Germany's policy toward the Polish nation and its culture evolved during the course of the war. Many German officials and military officers were initially not given any clear guidelines on the treatment of Polish cultural institutions, but this quickly changed. Immediately following their invasion of Poland, in September 1939 the Nazi German government implemented the first stages (the "small plan") of Generalplan OstGeneralplan Ost

Generalplan Ost was a secret Nazi German plan for the colonization of Eastern Europe. Implementing it would have necessitated genocide and ethnic cleansing to be undertaken in the Eastern European territories occupied by Germany during World War II...

. The basic policy was outlined by the Berlin Office of Racial Policy

Office of Racial Policy

The NSDAP Office of Racial Policy was a Nazi Party office created in 1933 for "unifying and supervising all indoctrination and propaganda work in the field of population and racial politics"...

in a document titled Concerning the Treatment of the Inhabitants of the Former Polish Territories, from a Racial-Political Standpoint. Slavic people living east of the pre-war German border were to be Germanized, enslaved

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

or eradicated, depending on whether they lived in the territories directly annexed into the German state or in the General Government

General Government

The General Government was an area of Second Republic of Poland under Nazi German rule during World War II; designated as a separate region of the Third Reich between 1939–1945...

.

Much of the German policy on Polish culture was formulated during a meeting between the governor of the General Government, Hans Frank

Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank was a German lawyer who worked for the Nazi party during the 1920s and 1930s and later became a high-ranking official in Nazi Germany...

, and Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels

Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels was a German politician and Reich Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. As one of Adolf Hitler's closest associates and most devout followers, he was known for his zealous oratory and anti-Semitism...

, at Łódź on 31 October 1939. Goebbels declared that "The Polish nation is not worthy to be called a cultured nation". He and Frank agreed that opportunities for the Poles to experience their culture should be severely restricted: no theaters, cinemas or cabarets; no access to radio or press; and no education. Frank suggested that the Poles should periodically be shown films highlighting the achievements of the Third Reich and should eventually be addressed only by megaphone

Megaphone

A megaphone, speaking-trumpet, bullhorn, blowhorn, or loud hailer is a portable, usually hand-held, cone-shaped horn used to amplify a person’s voice or other sounds towards a targeted direction. This is accomplished by channelling the sound through the megaphone, which also serves to match the...

. During the following weeks Polish schools beyond middle vocational levels were closed, as were theaters and many other cultural institutions. The only Polish-language

Polish language

Polish is a language of the Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages, used throughout Poland and by Polish minorities in other countries...

newspaper published in occupied Poland was also closed, and the arrests of Polish intellectuals began.

In March 1940, all cultural activities came under the control of the General Government's Department of People's Education and Propaganda (Abteilung für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda), whose name was changed a year later to the "Chief Propaganda Department" (Hauptabteilung Propaganda). Further directives issued in the spring and early summer reflected policies that had been outlined by Frank and Goebbels during the previous autumn. One of the Department's earliest decrees prohibited the organization of all but the most "primitive" of cultural activities without the Department's prior approval. Spectacles of "low quality", including those of an erotic or pornographic nature, were however an exception—those were to be popularized to appease the population and to show the world the "real" Polish culture as well as to create the impression that Germany was not preventing Poles from expressing themselves. German propaganda specialists invited critics from neutral countries to specially organized "Polish" performances that were specifically designed to be boring or pornographic, and presented them as typical Polish cultural activities. Polish-German cooperation in cultural matters, such as joint public performances, was strictly prohibited. Meanwhile, a compulsory registration scheme for writers and artists was introduced in August 1940. Then, in October, the printing of new Polish-language books was prohibited; existing titles were censored, and often confiscated and withdrawn.

In 1941, German policy evolved further, calling for the complete destruction of the Polish people

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

, whom the Nazis regarded as "subhuman" (Untermensch

Untermensch

Untermensch is a term that became infamous when the Nazi racial ideology used it to describe "inferior people", especially "the masses from the East," that is Jews, Gypsies, Poles along with other Slavic people like the Russians, Serbs, Belarussians and Ukrainians...

en). Within ten to twenty years, the Polish territories under German occupation were to be entirely cleared of ethnic Poles and settled by German colonists

Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment, maintenance, acquisition and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is a process whereby the metropole claims sovereignty over the colony and the social structure, government, and economics of the colony are changed by...

.

The policy was relaxed somewhat in the final years of occupation (1943–44), in view of German military defeats and the approaching Eastern Front. The Germans hoped that a more lenient cultural policy would lessen unrest and weaken the Polish Resistance. Poles were allowed back into those museums that now supported German propaganda and indoctrination, such as the newly created Chopin museum, which emphasized the composer's invented German roots. Restrictions on education, theater and music performances were eased.

Given that the Second Polish Republic

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

was a multicultural state, German policies and propaganda also sought to create and encourage conflicts between ethnic groups, fueling tension between Poles and Jews, and between Poles and Ukrainians. In Łódź, the Germans forced Jews to help destroy a monument to a Polish hero, Tadeusz Kościuszko

Tadeusz Kosciuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko was a Polish–Lithuanian and American general and military leader during the Kościuszko Uprising. He is a national hero of Poland, Lithuania, the United States and Belarus...

, and filmed them committing the act. Soon afterward, the Germans set fire to a Jewish synagogue

Synagogue

A synagogue is a Jewish house of prayer. This use of the Greek term synagogue originates in the Septuagint where it sometimes translates the Hebrew word for assembly, kahal...

and filmed Polish bystanders, portraying them in propaganda releases as a "vengeful mob." This divisive policy was reflected in the Germans' decision to destroy Polish education, while at the same time, showing relative tolerance toward the Ukrainian school system. As the high-ranking Nazi official

Gauleiter

A Gauleiter was the party leader of a regional branch of the NSDAP or the head of a Gau or of a Reichsgau.-Creation and Early Usage:...

Erich Koch

Erich Koch

Erich Koch was a Gauleiter of the Nazi Party in East Prussia from 1928 until 1945. Between 1941 and 1945 he was the Chief of Civil Administration of Bezirk Bialystok. During this period, he was also the Reichskommissar in Reichskommissariat Ukraine from 1941 until 1943...

explained, "We must do everything possible so that when a Pole meets a Ukrainian, he will be willing to kill the Ukrainian and conversely, the Ukrainian will be willing to kill the Pole."

Plunder

In 1939, as the occupation regime was being established, the Nazis confiscated Polish state property and much private property. Countless art objects were looted and taken to Germany, in line with a plan that had been drawn up well in advance of the invasion. The looting was supervised by experts of the SS-AhnenerbeAhnenerbe

The Ahnenerbe was a Nazi German think tank that promoted itself as a "study society for Intellectual Ancient History." Founded on July 1, 1935, by Heinrich Himmler, Herman Wirth, and Richard Walther Darré, the Ahnenerbe's goal was to research the anthropological and cultural history of the Aryan...

, Einsatzgruppen

Einsatzgruppen

Einsatzgruppen were SS paramilitary death squads that were responsible for mass killings, typically by shooting, of Jews in particular, but also significant numbers of other population groups and political categories...

units, who were responsible for art, and by experts of Haupttreuhandstelle Ost, who were responsible for more mundane objects. Notable items plundered by the Nazis included the Altar of Veit Stoss

Altar of Veit Stoss

The Altarpiece of Veit Stoss , also St. Mary's Altar , is the largest Gothic altarpiece in the World and a national treasure of Poland. It is located behind the Communion table of St. Mary's Basilica, Kraków...

and paintings by Raphael

Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino , better known simply as Raphael, was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. His work is admired for its clarity of form and ease of composition and for its visual achievement of the Neoplatonic ideal of human grandeur...

, Rembrandt, Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci was an Italian Renaissance polymath: painter, sculptor, architect, musician, scientist, mathematician, engineer, inventor, anatomist, geologist, cartographer, botanist and writer whose genius, perhaps more than that of any other figure, epitomized the Renaissance...

, Canaletto

Canaletto

Giovanni Antonio Canal better known as Canaletto , was a Venetian painter famous for his landscapes, or vedute, of Venice. He was also an important printmaker in etching.- Early career :...

and Bacciarelli

Bacciarelli

Bacciarelli is an Italian surname and Polish family:* Marcello Bacciarelli** Bacciarelli coat of arms...

. Most of the important art pieces had been "secured" by the Nazis within six months of September 1939; by the end of 1942, German officials estimated that "over 90%" of the art previously in Poland was in their possession. Some art was shipped to German museums, such as the planned Führermuseum

Führermuseum

The Führermuseum was an unrealized museum complex planned by Adolf Hitler for the Austrian city of Linz to display the collection of art plundered or purchased by the Nazis throughout Europe during World War II.-Design:...

in Linz

Linz

Linz is the third-largest city of Austria and capital of the state of Upper Austria . It is located in the north centre of Austria, approximately south of the Czech border, on both sides of the river Danube. The population of the city is , and that of the Greater Linz conurbation is about...

, while other art became the private property of Nazi officials. Over 516,000 individual art pieces were taken, including 2,800 paintings by European painters; 11,000 works by Polish painters; 1,400 sculptures, 75,000 manuscripts, 25,000 maps, and 90,000 books (including over 20,000 printed before 1800); as well as hundreds of thousands of other objects of artistic and historic value. Even exotic animals were taken from the zoo

Zoo

A zoological garden, zoological park, menagerie, or zoo is a facility in which animals are confined within enclosures, displayed to the public, and in which they may also be bred....

s.

Destruction

Many places of learning and culture—universities, schools, libraries, museums, theaters and cinemas—were either closed or designated as "Nur für DeutscheNur für Deutsche

The slogan Nur für Deutsche was during World War II, in many German-occupied countries, a racialist slogan indicating that certain establishments and transportation were reserved only for Germans...

" (For Germans Only). Twenty-five museums and a host of other institutions were destroyed during the war. According to one estimate, by war's end 43% of the infrastructure of Poland's educational and research institutions and 14% of its museums had been destroyed. According to another, only 105 of pre-war Poland's 175 museums survived the war, and just 33 of these institutions were able to reopen. Of pre-war Poland's 603 scientific institutions, about half were totally destroyed, and only a few survived the war relatively intact.

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

were arrested and executed, or transported to concentration camps

Nazi concentration camps

Nazi Germany maintained concentration camps throughout the territories it controlled. The first Nazi concentration camps set up in Germany were greatly expanded after the Reichstag fire of 1933, and were intended to hold political prisoners and opponents of the regime...

, during operations such as AB-Aktion. This particular campaign resulted in the infamous Sonderaktion Krakau

Sonderaktion Krakau

Sonderaktion Krakau was the codename for a German operation against professors and academics from the University of Kraków and other Kraków universities at the beginning of World War II....

and the massacre of Lwów professors. During World War II Poland lost 39% to 45% of its physicians and dentists, 26% to 57% of its lawyers, 15% to 30% of its teachers, 30% to 40% of its scientists and university professors, and 18% to 28% of its clergy. The Jewish intelligentsia was exterminated altogether. The reasoning behind this policy was clearly articulated by a Nazi gauleiter

Gauleiter

A Gauleiter was the party leader of a regional branch of the NSDAP or the head of a Gau or of a Reichsgau.-Creation and Early Usage:...

: "In my district, [any Pole who] shows signs of intelligence will be shot."

As part of their program to suppress Polish culture, the German Nazis attempted to destroy Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

in Poland, with a particular emphasis on the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

. In some parts of occupied Poland, Poles were restricted, or even forbidden, from attending religious services. At the same time, church property was confiscated, prohibitions were placed on using the Polish language in religious services, organizations affiliated with the Catholic Church were abolished, and it was forbidden to perform certain religious songs—or to read passages of the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

—in public. The worst conditions were found in the Reichsgau Wartheland

Reichsgau Wartheland

Reichsgau Wartheland was a Nazi German Reichsgau formed from Polish territory annexed in 1939. It comprised the Greater Poland and adjacent areas, and only in part matched the area of the similarly named pre-Versailles Prussian province of Posen...

, which the Nazis treated as a laboratory for their anti-religious policies. Polish clergy and religious leaders figured prominently among portions of the intelligentsia that were targeted for extermination.

To forestall the rise of a new generation of educated Poles, German officials decreed that the schooling of Polish children would be limited to a few years of elementary education. Reichsführer-SS

Reichsführer-SS

was a special SS rank that existed between the years of 1925 and 1945. Reichsführer-SS was a title from 1925 to 1933 and, after 1934, the highest rank of the German Schutzstaffel .-Definition:...

Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler was Reichsführer of the SS, a military commander, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. As Chief of the German Police and the Minister of the Interior from 1943, Himmler oversaw all internal and external police and security forces, including the Gestapo...

wrote, in a memorandum of May 1940: "The sole purpose of this schooling is to teach them simple arithmetic, nothing above the number 500; how to write one's name; and the doctrine that it is divine law to obey the Germans .... I do not regard a knowledge of reading as desirable." Hans Frank

Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank was a German lawyer who worked for the Nazi party during the 1920s and 1930s and later became a high-ranking official in Nazi Germany...

echoed him: "The Poles do not need universities or secondary schools; the Polish lands are to be converted into an intellectual desert." The situation was particularly dire in the former Polish territories beyond the General Government

General Government

The General Government was an area of Second Republic of Poland under Nazi German rule during World War II; designated as a separate region of the Third Reich between 1939–1945...

, which had been annexed to the Third Reich

Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany

At the beginning of World War II, nearly a quarter of the pre-war Polish areas were annexed by Nazi Germany and placed directly under German civil administration, while the rest of Nazi occupied Poland was named as General Government...

. The specific policy varied from territory to territory, but in general, there was no Polish-language education at all. German policy constituted a crash-Germanization of the populace. Polish teachers were dismissed, and some were invited to attend "orientation" meetings with the new administration, where they were either summarily arrested or executed on the spot. Some Polish schoolchildren were sent to German schools, while others were sent to special schools where they spent most of their time as unpaid laborers, usually on German-run farms; speaking Polish brought severe punishment. It was expected that Polish children would begin to work

Child labor

Child labour refers to the employment of children at regular and sustained labour. This practice is considered exploitative by many international organizations and is illegal in many countries...

once they finished their primary education at age 12 to 15. In the eastern territories not included in the General Government (Bezirk Bialystok

Bezirk Bialystok

The Bezirk Bialystok , also Belostok was an administrative unit that existed during the World War II occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany...

, Reichskommissariat Ostland

Reichskommissariat Ostland

Reichskommissariat Ostland, literally "Reich Commissariat Eastland", was the civilian occupation regime established by Nazi Germany in the Baltic states and much of Belarus during World War II. It was also known as Reichskommissariat Baltenland initially...

and Reichskommissariat Ukraine

Reichskommissariat Ukraine

Reichskommissariat Ukraine , literally "Reich Commissariat of Ukraine", was the civilian occupation regime of much of German-occupied Ukraine during World War II. Between September 1941 and March 1944, the Reichskommissariat was administered by Reichskommissar Erich Koch as a colony...

) many primary schools were closed, and most education was conducted in non-Polish languages such as Ukrainian, Belorussian, and Lithuanian. In the Bezirk Bialystok region, for example, 86% of the schools that had existed before the war were closed down during the first two years of German occupation, and by the end of the following year that figure had increased to 93%.

General Government

The General Government was an area of Second Republic of Poland under Nazi German rule during World War II; designated as a separate region of the Third Reich between 1939–1945...

, though by the end of 1940, only 30% of prewar schools were operational, and only 28% of prewar Polish children attended them. A German police memorandum

Memorandum

A memorandum is from the Latin verbal phrase memorandum est, the gerundive form of the verb memoro, "to mention, call to mind, recount, relate", which means "It must be remembered ..."...

of August 1943 described the situation as follows:

In the General Government, the remaining schools were subjugated to the German educational system, and the number and competence of their Polish staff was steadily scaled down. All universities and most secondary schools were closed, if not immediately after the invasion, then by mid-1940. By late 1940, no official Polish educational institutions more advanced than a vocational school

Vocational school

A vocational school , providing vocational education, is a school in which students are taught the skills needed to perform a particular job...