Reception history of Jane Austen

Encyclopedia

Fandom

Fandom is a term used to refer to a subculture composed of fans characterized by a feeling of sympathy and camaraderie with others who share a common interest...

. Jane Austen

Jane Austen

Jane Austen was an English novelist whose works of romantic fiction, set among the landed gentry, earned her a place as one of the most widely read writers in English literature, her realism and biting social commentary cementing her historical importance among scholars and critics.Austen lived...

, the author of such works as Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice is a novel by Jane Austen, first published in 1813. The story follows the main character Elizabeth Bennet as she deals with issues of manners, upbringing, morality, education and marriage in the society of the landed gentry of early 19th-century England...

(1813) and Emma

Emma

Emma, by Jane Austen, is a novel about the perils of misconstrued romance. The novel was first published in December 1815. As in her other novels, Austen explores the concerns and difficulties of genteel women living in Georgian-Regency England; she also creates a lively 'comedy of manners' among...

(1815), has become one of the best-known and widely read novelists in the English language.

During her lifetime, Austen's novels brought her little personal fame; like many women writers, she chose to publish anonymously and it was only among members of the aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

that her authorship was an open secret

Open secret

An open secret is a concept or idea that is "officially" secret or restricted in knowledge, but is actually widely known; or refers to something which is widely known to be true, but which none of the people most intimately concerned are willing to categorically acknowledge in public.Examples of...

. At the time they were published, Austen's works were considered fashionable by members of high society but received few positive reviews. By the mid-19th century, her novels were admired by members of the literary elite who viewed their appreciation of her works as a mark of cultivation. The publication in 1870 of her nephew's Memoir of Jane Austen

A Memoir of Jane Austen

A Memoir of Jane Austen is a biography of the novelist Jane Austen published in 1869 by her nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh. A second edition was published in 1871 which included previously unpublished Jane Austen writings. A family project, the biography was written by James Edward Austen-Leigh...

introduced her to a wider public as an appealing personality—dear, quiet aunt Jane—and her works were republished in popular editions. By the turn of the 20th century, competing groups had sprung up—some to worship her and some to defend her from the "teeming masses"—but all claiming to be the true Janeite

Janeite

The term Janeite has been both embraced by devotees of the works of Jane Austen as well as used as a term of opprobrium. According to Austen scholar Claudia Johnson Janeitism is "the self-consciously idolatrous enthusiasm for 'Jane' and every detail relative to her".Janeitism did not begin until...

s, or those who properly appreciated Austen.

Early in the 20th century, scholars produced a carefully edited collection of her works—the first for any British novelist—but it was not until the 1940s that Austen was widely accepted in academia as a "great English novelist". The second half of the 20th century saw a proliferation of Austen scholarship, which explored numerous aspects of her works: artistic, ideological, and historical. With the growing professionalisation of university English departments in the first half of the 20th century, criticism of Austen became progressively more esoteric and, as a result, appreciation of Austen splintered into distinctive high culture and popular culture trends. In the late 20th century, fans founded Jane Austen societies and clubs to celebrate the author, her time, and her works. As of the early 21st century, Austen fandom supports an industry of printed sequels and prequels as well as television and film adaptations, which started with the 1940 Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice (1940 film)

Pride and Prejudice is a 1940 film adaptation of Jane Austen's novel of the same name. Robert Z. Leonard directed, and Aldous Huxley served as one of the screenwriters of the film. It is adapted specifically from the stage adaptation by Helen Jerome in addition to Jane Austen's novel...

and evolved to include the 2004 Bollywood

Bollywood

Bollywood is the informal term popularly used for the Hindi-language film industry based in Mumbai , Maharashtra, India. The term is often incorrectly used to refer to the whole of Indian cinema; it is only a part of the total Indian film industry, which includes other production centers producing...

-style production Bride and Prejudice

Bride and Prejudice

Bride and Prejudice is a 2004 romantic musical film directed by Gurinder Chadha. The screenplay by Chadha and Paul Mayeda Berges is a Bollywood-style adaptation of Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen. It was filmed primarily in English, with some Hindi and Punjabi dialogue. The film released in...

.

Background

Landed gentry

Landed gentry is a traditional British social class, consisting of land owners who could live entirely off rental income. Often they worked only in an administrative capacity looking after the management of their own lands....

. Her family's steadfast support was critical to Austen's development as a professional writer. For example, Austen read draft versions of all of her novels to her family, receiving feedback and encouragement; in fact, it was her father who sent out her first publication bid. Austen's artistic apprenticeship lasted from her teenage years until she was about thirty-five. During this period, she experimented with various literary forms, including the epistolary novel

Epistolary novel

An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of documents. The usual form is letters, although diary entries, newspaper clippings and other documents are sometimes used. Recently, electronic "documents" such as recordings and radio, blogs, and e-mails have also come into use...

which she tried and then abandoned, and wrote and extensively revised three major novels and began a fourth. With the release of Sense and Sensibility

Sense and Sensibility

Sense and Sensibility, published in 1811, is a British romance novel by Jane Austen, her first published work under the pseudonym, "A Lady." Jane Austen is considered a pioneer of the romance genre of novels, and for the realism portrayed in her novels, is one the most widely read writers in...

(1811), Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice is a novel by Jane Austen, first published in 1813. The story follows the main character Elizabeth Bennet as she deals with issues of manners, upbringing, morality, education and marriage in the society of the landed gentry of early 19th-century England...

(1813), Mansfield Park

Mansfield Park (novel)

Mansfield Park is a novel by Jane Austen, written at Chawton Cottage between 1812 and 1814. It was published in July 1814 by Thomas Egerton, who published Jane Austen's two earlier novels, Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice...

(1814) and Emma

Emma

Emma, by Jane Austen, is a novel about the perils of misconstrued romance. The novel was first published in December 1815. As in her other novels, Austen explores the concerns and difficulties of genteel women living in Georgian-Regency England; she also creates a lively 'comedy of manners' among...

(1815), she achieved success as a published writer.

However, novel-writing was a suspect occupation for women in the early 19th century, because it imperiled their social reputation—it brought them publicity viewed as unfeminine. Therefore, like many other female writers, Austen published anonymously. Eventually, though, her novels' authorship became an open secret

Open secret

An open secret is a concept or idea that is "officially" secret or restricted in knowledge, but is actually widely known; or refers to something which is widely known to be true, but which none of the people most intimately concerned are willing to categorically acknowledge in public.Examples of...

among the aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

. During one of her visits to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, the Prince Regent

George IV of the United Kingdom

George IV was the King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and also of Hanover from the death of his father, George III, on 29 January 1820 until his own death ten years later...

invited her to his home; his librarian gave her a tour and mentioned that the Regent admired her novels and that "if Miss Austen had any other Novel forthcoming, she was quite at liberty to dedicate it to the Prince". Austen, who disapproved of the prince's extravagant lifestyle, did not want to follow this suggestion, but her friends convinced her otherwise: in short order, Emma was dedicated to him. Austen turned down the librarian's further hint to write a historical romance in honor of the prince's daughter's marriage.

In the last year of her life, Austen revised Northanger Abbey

Northanger Abbey

Northanger Abbey was the first of Jane Austen's novels to be completed for publication, though she had previously made a start on Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice. According to Cassandra Austen's Memorandum, Susan was written approximately during 1798–99...

(1817), wrote Persuasion

Persuasion (novel)

Persuasion is Jane Austen's last completed novel. She began it soon after she had finished Emma, completing it in August 1816. She died, aged 41, in 1817; Persuasion was published in December that year ....

(1817), and began another novel, eventually titled Sanditon

Sanditon

Sanditon , also known as Sand and Sandition is an unfinished novel by the British novelist Jane Austen.-Background:In Sanditon, Austen explored her interest in the verbal construction of a society by means of a town – and a set of families – that is still in the process of being formed...

, which was left unfinished at her death. Austen did not have time to see Northanger Abbey or Persuasion through the press, but her family published them as one volume after her death and her brother Henry included a "Biographical Notice of the Author". This short biography sowed the seeds for the myth of Austen as a quiet, retiring aunt who wrote during her spare time: "Neither the hope of fame nor profit mixed with her early motives ... [S]o much did she shrink from notoriety, that no accumulation of fame would have induced her, had she lived, to affix her name to any productions of her public she turned away from any allusion to the character of an authoress." However, this description is in direct contrast to the excitement Austen shows in her letters regarding publication and profit: Austen was a professional writer.

Austen's works are noted for their realism

Literary realism

Literary realism most often refers to the trend, beginning with certain works of nineteenth-century French literature and extending to late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century authors in various countries, towards depictions of contemporary life and society "as they were." In the spirit of...

, biting social commentary, and masterful use of free indirect speech

Free indirect speech

Free indirect speech is a style of third-person narration which uses some of the characteristics of third-person along with the essence of first-person direct speech...

, burlesque and irony

Irony

Irony is a rhetorical device, literary technique, or situation in which there is a sharp incongruity or discordance that goes beyond the simple and evident intention of words or actions...

. They critique the novels of sensibility

Sentimental novel

The sentimental novel or the novel of sensibility is an 18th century literary genre which celebrates the emotional and intellectual concepts of sentiment, sentimentalism, and sensibility...

of the second half of the 18th century and are part of the transition to 19th-century realism. As Susan Gubar

Susan Gubar

Dr. Susan D. Gubar is an American academic and Distinguished Professor of English and Women's Studies at Indiana University. She is co-author with Dr. Sandra M. Gilbert of the standard feminist text, The Madwoman in the Attic and a trilogy on women's writing in the twentieth century.Her book...

and Sandra Gilbert

Sandra Gilbert

Sandra M. Gilbert , Professor Emerita of English at the University of California, Davis, is an influential literary critic and poet who has published widely in the fields of feminist literary criticism, feminist theory, and psychoanalytic criticism...

explain, Austen makes fun of "such novelistic clichés as love at first sight, the primacy of passion over all other emotions and/or duties, the chivalric exploits of the hero, the vulnerable sensitivity of the heroine, the lovers' proclaimed indifference to financial considerations, and the cruel crudity of parents". Austen's plots, though comic, highlight the way women depend on marriage to secure social standing and economic security. Like the writings of Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

, a strong influence on her, her works are fundamentally concerned with moral issues.

1812–1821: Individual reactions and contemporary reviews

Henrietta Ponsonby, Countess of Bessborough

Henrietta Ponsonby, Countess of Bessborough , born Lady Henrietta Frances Spencer , was the wife of Frederick Ponsonby, 3rd Earl of Bessborough and mother of the notorious Lady Caroline Lamb. Her father, John Spencer, 1st Earl Spencer, was a great-grandson of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough...

, sister to the notorious Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, commented on Sense and Sensibility in a letter to a friend: "it is a clever novel. ... tho' it ends stupidly, I was much amused by it." The fifteen-year-old daughter of the Prince Regent, Princess Charlotte Augusta

Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales

Princess Charlotte of Wales was the only child of George, Prince of Wales and Caroline of Brunswick...

, compared herself to one of the book's heroines: "I think Marianne & me are very like in disposition, that certainly I am not so good, the same imprudence, &tc". After reading Pride and Prejudice, playwright Richard Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan was an Irish-born playwright and poet and long-term owner of the London Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. For thirty-two years he was also a Whig Member of the British House of Commons for Stafford , Westminster and Ilchester...

advised a friend to "[b]uy it immediately" for it "was one of the cleverest things" he had ever read. Anne Milbanke

Anne Isabella Byron, Baroness Byron

Anne Isabella Noel Byron, 11th Baroness Wentworth and Baroness Byron was the wife of the poet Lord Byron, and mother of Ada Lovelace, the patron and co-worker of mathematician Charles Babbage.-Name:Her names were unusually complex...

, future wife of the Romantic poet

Romantic poetry

Romanticism, a philosophical, literary, artistic and cultural era which began in the mid/late-1700s as a reaction against the prevailing Enlightenment ideals of the day , also influenced poetry...

Lord Byron, wrote that "I have finished the Novel called Pride and Prejudice, which I think a very superior work." She commented that the novel "is the most probable fiction I have ever read" and had become "at present the fashionable novel". The Dowager Lady Vernon told a friend that Mansfield Park was "[n]ot much of a novel, more the history of a family party in the country, very natural"—as if, comments one Austen scholar, "Lady Vernon's parties mostly featured adultery." Lady Anne Romilly told her friend, the novelist Maria Edgeworth

Maria Edgeworth

Maria Edgeworth was a prolific Anglo-Irish writer of adults' and children's literature. She was one of the first realist writers in children's literature and was a significant figure in the evolution of the novel in Europe...

, that "[Mansfield Park] has been pretty generally admired here" and Edgeworth commented later that "we have been much entertained with Mansfield Park".

Despite these positive reactions from the elite, Austen's novels received relatively few reviews during her lifetime: two for Sense and Sensibility, three for Pride and Prejudice, none for Mansfield Park, and seven for Emma. Most of the reviews were short and on balance favourable, although superficial and cautious. They most often focused on the moral lessons of the novels. Moreover, as Brian Southam, who has edited the definitive volumes on Austen's reception, writes in his description of these reviewers, "their job was merely to provide brief notices, extended with quotations, for the benefit of women readers compiling their library lists and interested only in knowing whether they would like a book for its story, its characters and moral". Asked by publisher John Murray to review Emma, famed historical novel

Historical novel

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, a historical novel is-Development:An early example of historical prose fiction is Luó Guànzhōng's 14th century Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which covers one of the most important periods of Chinese history and left a lasting impact on Chinese culture.The...

ist Walter Scott

Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet was a Scottish historical novelist, playwright, and poet, popular throughout much of the world during his time....

wrote the longest and most thoughtful of these reviews, which was published anonymously in the March 1816 issue of the Quarterly Review

Quarterly Review

The Quarterly Review was a literary and political periodical founded in March 1809 by the well known London publishing house John Murray. It ceased publication in 1967.-Early years:...

. Using the review as a platform from which to defend the then disreputable genre of the novel

Novel

A novel is a book of long narrative in literary prose. The genre has historical roots both in the fields of the medieval and early modern romance and in the tradition of the novella. The latter supplied the present generic term in the late 18th century....

, Scott praised Austen's works, celebrating her ability to copy "from nature as she really exists in the common walks of life, and presenting to the correct and striking representation of that which is daily taking place around him". Modern Austen scholar William Galperin has noted that "unlike some of Austen's lay readers, who recognized her divergence from realistic practice as it had been prescribed and defined at the time, Walter Scott may well have been the first to install Austen as the realist par excellence". Scott wrote in his private journal in 1826, in what later became a widely quoted comparison:

Also read again and for the third time at least Miss Austen's very finely written novel of Pride and Prejudice. That young lady had a talent for describing the involvement and feelings and characters of ordinary life which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with. The Big Bow-wow strain I can do myself like any now going, but the exquisite touch which renders ordinary commonplace things and characters interesting from the truth of the description and the sentiment is denied to me. What a pity such a gifted creature died so early!

British Critic

The British Critic: A New Review was a quarterly publication, established in 1793 as a conservative and high church review journal riding the tide of British reaction against the French Revolution.-High church review:...

in March 1818 and in the Edinburgh Review and Literary Miscellany

Edinburgh Review

The Edinburgh Review, founded in 1802, was one of the most influential British magazines of the 19th century. It ceased publication in 1929. The magazine took its Latin motto judex damnatur ubi nocens absolvitur from Publilius Syrus.In 1984, the Scottish cultural magazine New Edinburgh Review,...

in May 1818. The reviewer for the British Critic felt that Austen's exclusive dependence on realism

Literary realism

Literary realism most often refers to the trend, beginning with certain works of nineteenth-century French literature and extending to late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century authors in various countries, towards depictions of contemporary life and society "as they were." In the spirit of...

was evidence of a deficient imagination. The reviewer for the Edinburgh Review disagreed, praising Austen for her "exhaustless invention" and the combination of the familiar and the surprising in her plots. Overall, Austen scholars have pointed out that these early reviewers did not know what to make of her novels—for example, they misunderstood her use of irony

Irony

Irony is a rhetorical device, literary technique, or situation in which there is a sharp incongruity or discordance that goes beyond the simple and evident intention of words or actions...

. Reviewers reduced Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice to didactic tales of virtue prevailing over vice.

In the Quarterly Review in 1821, the English writer and theologian Richard Whately

Richard Whately

Richard Whately was an English rhetorician, logician, economist, and theologian who also served as the Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin.-Life and times:...

published the most serious and enthusiastic early posthumous review of Austen's work. Whately drew favourable comparisons between Austen and such acknowledged greats as Homer

Homer

In the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

and Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon"...

, praising the dramatic qualities of her narrative. He also affirmed the respectability and legitimacy of the novel as a genre, arguing that imaginative literature, especially narrative, was more valuable than history or biography. When it was properly done, as in Austen, Whately said, imaginative literature concerned itself with generalised human experience from which the reader could gain important insights into human nature; in other words, it was moral. Whately also addressed Austen's position as a female writer, writing: "we suspect one of Miss Austin's [sic] great merits in our eyes to be, the insight she gives us into the peculiarities of female heroines are what one knows women must be, though one never can get them to acknowledge it." No more significant, original Austen criticism was published until the late 19th century: Whately and Scott had set the tone for the Victorian era's

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

view of Austen.

1821–1870: Cultured few

Ian Watt

Ian Watt was a literary critic, literary historian and professor of English at Stanford University. His Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding is an important work in the history of the genre...

, appreciated her " to ordinary social experience". However, Austen's novels did not conform to certain strong Romantic

Romanticism

Romanticism was an artistic, literary and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the 18th century in Europe, and gained strength in reaction to the Industrial Revolution...

and Victorian

Victorian literature

Victorian literature is the literature produced during the reign of Queen Victoria . It forms a link and transition between the writers of the romantic period and the very different literature of the 20th century....

British preferences, which required that "powerful emotion [be] authenticated by an egregious display of sound and color in the writing". Victorian critics and audiences were drawn to the work of authors such as Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian period. Dickens enjoyed a wider popularity and fame than had any previous author during his lifetime, and he remains popular, having been responsible for some of English literature's most iconic...

and George Eliot

George Eliot

Mary Anne Evans , better known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, journalist and translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era...

; by comparison, Austen's novels seemed provincial and quiet. Although Austen's works were republished beginning in late 1832 or early 1833 by Richard Bentley in the Standard Novels series, and remained in print continuously thereafter, they were not bestsellers. Southam describes her "reading public between 1821 and 1870" as "minute beside the known audience for Dickens and his contemporaries".

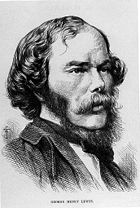

Those who did read Austen saw themselves as discriminating readers—they were a cultured few. This became a common theme of Austen criticism during the nineteenth and early 20th centuries. Philosopher and literary critic George Henry Lewes

George Henry Lewes

George Henry Lewes was an English philosopher and critic of literature and theatre. He became part of the mid-Victorian ferment of ideas which encouraged discussion of Darwinism, positivism, and religious scepticism...

articulated this theme in a series of enthusiastic articles in the 1840s and 1850s. In "The Novels of Jane Austen", published anonymously in Blackwood's Magazine

Blackwood's Magazine

Blackwood's Magazine was a British magazine and miscellany printed between 1817 and 1980. It was founded by the publisher William Blackwood and was originally called the Edinburgh Monthly Magazine. The first number appeared in April 1817 under the editorship of Thomas Pringle and James Cleghorn...

in 1859, Lewes praised Austen's novels for "the economy of easy adaptation of means to ends, with no aid from superfluous elements" and compared her to Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon"...

. Arguing that Austen lacked the ability to construct a plot, he still celebrated her dramatisations: "The reader's pulse never throbs, his curiosity is never intense; but his interest never wanes for a moment. The action begins; the people speak, feel, and act; everything that is said, felt, or done tends towards the entanglement or disentanglement of the plot; and we are almost made actors as well as spectators of the little drama."

Reacting against Lewes's essays and his personal communications with her, novelist Charlotte Brontë

Charlotte Brontë

Charlotte Brontë was an English novelist and poet, the eldest of the three Brontë sisters who survived into adulthood, whose novels are English literature standards...

admired Austen's fidelity to everyday life but described her as "only shrewd and observant" and criticised the absence of visible passion in her work. To Brontë, Austen's work appeared formal and constrained, "a carefully fenced, highly cultivated garden, with neat borders and delicate flowers; but no glance of bright vivid physiognomy, no open country, no fresh air, no blue hill, no bonny beck".

Nineteenth-century European translations

English novel

The English novel is an important part of English literature.-Early novels in English:A number of works of literature have each been claimed as the first novel in English. See the article First novel in English.-Romantic novel:...

tradition. This perception was reinforced by the changes made by translators who injected sentimentalism

Sentimentalism (literature)

Sentimentalism , as a literary and political discourse, has occurred much in the literary traditions of all regions in the world, and is central to the traditions of Indian literature, Chinese literature, and Vietnamese literature...

into Austen's novels and eliminated their humour and irony. European readers therefore more readily associated Walter Scott's style with the English novel.

Because of the significant changes made by her translators, Austen was received as a different kind of novelist on the Continent than in Britain. For example, the French novelist Isabelle de Montolieu

Isabelle de Montolieu

Isabelle de Montolieu was a Swiss novelist and translator. She wrote in and translated to the French language. Montolieu penned a few original novels and over 100 volumes of translations...

translated several of Austen's novels into a genre in which Montolieu herself wrote: the French sentimental novel. In Montolieu's Pride and Prejudice, for example, vivacious conversations between Elizabeth and Darcy were replaced by decorous ones. Elizabeth's claim that she has "always seen a great similarity in the turn of [their] minds" (her and Darcy's) because they are "unwilling to speak, unless [they] expect to say something that will amaze the whole room" becomes "Moi, je garde le silence, parce que je ne sais que dire, et vous, parce que vous aiguisez vos traits pour parler avec effet." ("Me, I keep silent, because I don't know what to say, and you, because you excite your features for effect when speaking.") As Cossy and Saglia explain in their essay on Austen translations, "the equality of mind which Elizabeth takes for granted is denied and gender distinction introduced". Because Austen’s works were seen in France as part of a sentimental tradition, they were overshadowed by the works of French realists such as Stendhal

Stendhal

Marie-Henri Beyle , better known by his pen name Stendhal, was a 19th-century French writer. Known for his acute analysis of his characters' psychology, he is considered one of the earliest and foremost practitioners of realism in his two novels Le Rouge et le Noir and La Chartreuse de Parme...

, Balzac, and Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert was a French writer who is counted among the greatest Western novelists. He is known especially for his first published novel, Madame Bovary , and for his scrupulous devotion to his art and style.-Early life and education:Flaubert was born on December 12, 1821, in Rouen,...

. German translations and reviews of those translations also placed Austen in a line of sentimental writers, particularly late Romantic women writers.

Family biographies

.jpg)

A Memoir of Jane Austen

A Memoir of Jane Austen is a biography of the novelist Jane Austen published in 1869 by her nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh. A second edition was published in 1871 which included previously unpublished Jane Austen writings. A family project, the biography was written by James Edward Austen-Leigh...

, which was written by Jane Austen's nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh. With its release, Austen's popularity and critical standing increased dramatically. Readers of the Memoir were presented with the myth of the amateur novelist who wrote masterpieces: the Memoir fixed in the public mind a sentimental picture of Austen as a quiet, middle-aged maiden aunt and reassured them that her work was suitable for a respectable Victorian

Victorian era

The Victorian era of British history was the period of Queen Victoria's reign from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence...

family. The publication of the Memoir spurred a major reissue of Austen's novels. The first popular editions were released in 1883—a cheap sixpenny series published by Routledge

Routledge

Routledge is a British publishing house which has operated under a succession of company names and latterly as an academic imprint. Its origins may be traced back to the 19th-century London bookseller George Routledge...

. This was followed by a proliferation of elaborate illustrated editions, collectors' sets, and scholarly editions. However, contemporary critics continued to assert that her works were sophisticated and only appropriate for those who could truly plumb their depths. Yet, after the publication of the Memoir, more criticism was published on Austen's novels in two years than had appeared in the previous fifty.

In 1913, William Austen-Leigh and Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh, descendants of the Austen family, published the definitive family biography, Jane Austen: Her Life and Letters—A Family Record. Based primarily on family papers and letters, it is described by Austen biographer Park Honan as "accurate, staid, reliable, and at times vivid and suggestive". Although the authors moved away from the sentimental tone of the Memoir, they made little effort to go beyond the family records and traditions immediately available to them. Their book therefore offers bare facts and little in the way of interpretation.

Criticism

During the last quarter of the 19th century, the first books of critical analysis regarding Austen's works were published. In 1890 Godwin Smith published the Life of Jane Austen, initiating a "fresh phase in the critical heritage", in which Austen reviewers became critics. This launched the beginning of "formal criticism", that is, a focus on Austen as a writer and an analysis of the techniques that made her writing unique. According to Southam, while Austen criticism increased in amount and, to some degree, in quality after 1870, "a certain uniformity" pervaded it:

We see the novels praised for their elegance of form and their surface 'finish'; for the realism of their fictional world, the variety and vitality of their characters; for their pervasive humour; and for their gentle and undogmatic morality and its unsermonising delivery. The novels are prized for their 'perfection'. Yet it is seen to be a narrow perfection, achieved within the bounds of domestic comedy.

Among the most astute of these critics were Richard Simpson

Richard Simpson (writer)

Richard Simpson was a British Roman Catholic writer and literary scholar. He was born at Beddington, Surrey, into an Anglican family, and was educated at Merchant Taylors' School and at Oriel College, Oxford. He obtained a BA degree on 9 February 1843...

, Margaret Oliphant, and Leslie Stephen

Leslie Stephen

Sir Leslie Stephen, KCB was an English author, critic and mountaineer, and the father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.-Life:...

. In a review of the Memoir, Simpson described Austen as a serious yet ironic critic of English society. He introduced two interpretative themes which later became the basis for modern literary criticism of Austen's works: humour as social critique and irony as a means of moral evaluation. Continuing Lewes's comparison to Shakespeare, Simpson wrote that Austen:

began by being an ironical critic; she manifested her by direct censure, but by the indirect method of imitating and exaggerating the faults of her , humour, irony, the judgment not of one that gives sentence but of the mimic who quizzes while he mocks, are her characteristics.

Lionel Trilling

Lionel Trilling was an American literary critic, author, and teacher. With wife Diana Trilling, he was a member of the New York Intellectuals and contributor to the Partisan Review. Although he did not establish a school of literary criticism, he is one of the leading U.S...

quoted it in 1957. Another prominent writer whose Austen criticism was ignored, novelist Margaret Oliphant, described Austen in almost proto-feminist terms, as "armed with a 'fine vein of feminine cynicism,' 'full of subtle power, keenness, finesse, and self-restraint,' blessed with an 'exquisite sense' of the 'ridiculous,' 'a fine stinging yet soft-voiced contempt,' whose novels are 'so calm and cold and keen'". This line of criticism would not be fully explored until the 1970s with the rise of feminist literary criticism

Feminist literary criticism

Feminist literary criticism is literary criticism informed by feminist theory, or by the politics of feminism more broadly. Its history has been broad and varied, from classic works of nineteenth-century women authors such as George Eliot and Margaret Fuller to cutting-edge theoretical work in...

.

Although Austen's novels had been published in the United States since 1832, albeit in bowdlerised editions, it was not until after 1870 that there was a distinctive American response to Austen. As Southam explains, "for American literary nationalists Jane Austen's cultivated scene was too pallid, too constrained, too refined, too downright unheroic". Austen was not democratic

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

enough for American tastes and her canvas did not explore the frontier

Frontier

A frontier is a political and geographical term referring to areas near or beyond a boundary. 'Frontier' was absorbed into English from French in the 15th century, with the meaning "borderland"--the region of a country that fronts on another country .The use of "frontier" to mean "a region at the...

themes that had come to define American literature. By the turn of the century, the American response was represented by the debate between the American novelist and critic William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells was an American realist author and literary critic. Nicknamed "The Dean of American Letters", he was particularly known for his tenure as editor of the Atlantic Monthly as well as his own writings, including the Christmas story "Christmas Every Day" and the novel The Rise of...

and the writer and humorist Mark Twain

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist...

. In a series of essays, Howells helped make Austen into a canonical figure for the populace whereas Twain used Austen to argue against the Anglophile

Anglophilia

An Anglophile is a person who is fond of English culture or, more broadly, British culture. Its antonym is Anglophobe.-Definition:The word comes from Latin Anglus "English" via French, and is ultimately derived from Old English Englisc "English" + Ancient Greek φίλος - philos, "friend"...

tradition in America. That is, Twain argued for the distinctiveness of American literature by attacking English literature. In his book Following the Equator, Twain described the library on his ship: "Jane Austen's absent from this library. Just that one omission alone would make a fairly good library out of a library that hadn't a book in it."

Janeites

| "Might we from Miss Austen's biographer the title which the affection of a nephew bestows upon her, and recognise her officially as 'dear aunt Jane'?" |

| — Richard Simpson Richard Simpson (writer) Richard Simpson was a British Roman Catholic writer and literary scholar. He was born at Beddington, Surrey, into an Anglican family, and was educated at Merchant Taylors' School and at Oriel College, Oxford. He obtained a BA degree on 9 February 1843... |

The Encyclopædia Britannica's

Encyclopædia Britannica

The Encyclopædia Britannica , published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia that is available in print, as a DVD, and on the Internet. It is written and continuously updated by about 100 full-time editors and more than 4,000 expert...

changing entries on Austen illustrate her increasing popularity and status. The eighth edition (1854) described her as "an elegant novelist" while the ninth edition (1875) lauded her as "one of the most distinguished modern British novelists". Around the turn of the century, Austen novels began to be studied at universities and appear in histories of the English novel. The image of her that dominated the popular imagination was still that first presented in the Memoir and made famous by Howells in his series of essays in Harper's Magazine

Harper's Magazine

Harper's Magazine is a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts, with a generally left-wing perspective. It is the second-oldest continuously published monthly magazine in the U.S. . The current editor is Ellen Rosenbush, who replaced Roger Hodge in January 2010...

, that of "dear aunt Jane". Author and critic Leslie Stephen

Leslie Stephen

Sir Leslie Stephen, KCB was an English author, critic and mountaineer, and the father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.-Life:...

described a mania that started to develop for Austen in the 1880s as "Austenolatry"—it was only after the publication of the Memoir that readers developed a personal connection with Austen. However, around 1900, members of the literary elite, who had claimed an appreciation of Austen as a mark of culture, reacted against this popularisation of her work. They referred to themselves as Janeite

Janeite

The term Janeite has been both embraced by devotees of the works of Jane Austen as well as used as a term of opprobrium. According to Austen scholar Claudia Johnson Janeitism is "the self-consciously idolatrous enthusiasm for 'Jane' and every detail relative to her".Janeitism did not begin until...

s to distinguish themselves from the masses who, in their view, did not properly understand Austen.

American novelist Henry James

Henry James

Henry James, OM was an American-born writer, regarded as one of the key figures of 19th-century literary realism. He was the son of Henry James, Sr., a clergyman, and the brother of philosopher and psychologist William James and diarist Alice James....

, one member of this literary elite, referred to Austen several times with approval and on one occasion ranked her with Shakespeare, Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was a Spanish novelist, poet, and playwright. His magnum opus, Don Quixote, considered the first modern novel, is a classic of Western literature, and is regarded amongst the best works of fiction ever written...

, and Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding was an English novelist and dramatist known for his rich earthy humour and satirical prowess, and as the author of the novel Tom Jones....

as among "the fine painters of life". But, James thought Austen an "unconscious" artist whom he described as "instinctive and charming". In 1905, James responded frustratingly to what he described as "a beguiled infatuation" with Austen, a rising tide of public interest that exceeded Austen's "intrinsic merit and interest". James attributed this rise principally to "the stiff breeze of the special bookselling body of publishers, editors, illustrators, producers of the pleasant twaddle of magazines; who have found their 'dear,' our dear, everybody's dear, Jane so infinitely to their material purpose, so amenable to pretty reproduction in every variety of what is called tasteful, and in what seemingly proves to be salable, form."

In an effort to avoid the sentimental image of the "Aunt Jane" tradition and approach Austen's fiction from a fresh perspective, in 1917 British intellectual and travel writer Reginald Farrer

Reginald Farrer

Reginald John Farrer , was a traveller and plant collector. He published a number of books, although is best known for My Rock Garden...

published a lengthy essay in the Quarterly Review which Austen scholar A. Walton Litz calls the best single introduction to her fiction. Southam describes it as a "Janeite" piece without the worship. Farrer denied that Austen's artistry was unconscious (contradicting James) and described her as a writer of intense concentration and a severe critic of her society, "radiant and remorseless", "dispassionate yet pitiless", with "the steely quality, the incurable rigor of her judgment". Farrer was one of the first critics who viewed Austen as a subversive writer.

1930–2000: Modern scholarship

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

Shakespearean scholar A. C. Bradley's

Andrew Cecil Bradley

Andrew Cecil Bradley was an English literary scholar, best remembered for his work on Shakespeare.-Life:...

1911 essay, "generally regarded as the starting-point for the serious academic approach to Jane Austen". Bradley emphasised Austen's ties to 18th-century critic and writer Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson , often referred to as Dr. Johnson, was an English author who made lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer...

, arguing that she was a moralist as well as humorist; in this he was "totally original", according to Southam. Bradley divided Austen's works into "early" and "late" novels, categories which are still used by scholars today. The second path-breaking early-20th century critic of Austen was R. W. Chapman, whose magisterial edition of Austen's collected works was the first scholarly edition of the works of any English novelist. The Chapman texts have remained the basis for all subsequent editions of Austen's works.

In the wake of Bradley and Chapman's contributions, the 1920s saw a boom in Austen scholarship; British novelist E. M. Forster

E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster OM, CH was an English novelist, short story writer, essayist and librettist. He is known best for his ironic and well-plotted novels examining class difference and hypocrisy in early 20th-century British society...

primarily illustrated his concept of the "round" character by citing Austen's works. It was with the 1939 publication of Mary Lascelles' Jane Austen and Her Art—"the first full-scale historical and scholarly study" of Austen—that the academic study of her works matured. Lascelles included a short biographical essay; an innovative analysis of the books Austen read and their effect on her writing; and an extended analysis of Austen's style and her "narrative art". Lascelles felt that prior critics had all worked on a scale "so small that the reader does not see how they have reached their conclusions until he has patiently found his own way to them". She wished to examine all of Austen's works together and to subject her style and techniques to methodical analysis. Subsequent critics agree that she succeeded. Like Bradley earlier, she emphasised Austen's connection to Samuel Johnson and her desire to discuss morality through fiction. However, at the time some fans of Austen worried that academics were taking over Austen criticism and it was becoming increasingly esoteric—a debate that has continued to the beginning of the 21st century.

Q. D. Leavis

Queenie Dorothy Leavis , née Roth, was an English literary critic and essayist.Born in Edmonton, England, she wrote about the historical sociology of reading and the development of the English, the European, and the American novel...

argued in "Critical Theory of Jane Austen's Writing", published in Scrutiny

Scrutiny (journal)

Scrutiny: A Quarterly Review was a literature periodical founded in 1932 by F. R. Leavis, who remained its principal editor until the final issue in 1953...

in the early 1940s, that Austen was a professional, not an amateur, writer. Harding's and Leavis's articles were followed by another revisionist treatment by Marvin Mudrick in Jane Austen: Irony as Defense and Discovery (1952). Mudrick portrayed Austen as isolated, defensive, and critical of her society, and described in detail the relationship he saw between Austen's attitude toward contemporary literature and her use of irony as a technique to contrast the realities of her society with what she felt they should be. These revisionist views, together with prominent British critic F. R. Leavis's

F. R. Leavis

Frank Raymond "F. R." Leavis CH was an influential British literary critic of the early-to-mid-twentieth century. He taught for nearly his entire career at Downing College, Cambridge.-Early life:...

pronouncement in The Great Tradition (1948) that Austen was one of the great writers of English fiction, a view shared by Ian Watt

Ian Watt

Ian Watt was a literary critic, literary historian and professor of English at Stanford University. His Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding is an important work in the history of the genre...

, who helped shape the scholarly debate regarding the genre

Genre

Genre , Greek: genos, γένος) is the term for any category of literature or other forms of art or culture, e.g. music, and in general, any type of discourse, whether written or spoken, audial or visual, based on some set of stylistic criteria. Genres are formed by conventions that change over time...

of the novel, did much to cement Austen's reputation amongst academics. They agreed that she "combined

Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding was an English novelist and dramatist known for his rich earthy humour and satirical prowess, and as the author of the novel Tom Jones....

and Samuel Richardson's

Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson was an 18th-century English writer and printer. He is best known for his three epistolary novels: Pamela: Or, Virtue Rewarded , Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady and The History of Sir Charles Grandison...

The period after the Second World War saw a flowering of scholarship on Austen as well as a diversity of critical approaches. One of the most fruitful and contentious has been the consideration of Austen as a political writer. As critic Gary Kelly explains, "Some see her as a political 'conservative' because she seems to defend the established social order. Others see her as sympathetic to 'radical' politics that challenged the established order, especially in the form of critics see Austen's novels as neither conservative nor subversive, but complex, criticizing aspects of the social order but supporting stability and an open class hierarchy." In Jane Austen and the War of Ideas (1975), perhaps the most important of these works, Marilyn Butler

Marilyn Butler

Marilyn Butler is a British literary critic. She was Rector of Exeter College, Oxford from 1993 to 2004, and was King Edward VII Professor of English Literature at the University of Cambridge, from 1986 to 1993...

argues that Austen was steeped in, not insulated from, the principal moral and political controversies of her time, and espoused a partisan, fundamentally conservative and Christian position in these controversies. In a similar vein, Alistair M. Duckworth in The Improvement of the Estate: A Study of Jane Austen's Novels (1971) argues that Austen used the concept of the "estate

Estate (house)

An estate comprises the houses and outbuildings and supporting farmland and woods that surround the gardens and grounds of a very large property, such as a country house or mansion. It is the modern term for a manor, but lacks the latter's now abolished jurisdictional authority...

" to symbolise all that was important about contemporary English society, which should be conserved, improved, and passed down to future generations. As Rajeswari Rajan notes in her essay on recent Austen scholarship, "the idea of a political Austen is no longer seriously challenged". The questions scholars now investigate involve: "the Revolution, war, nationalism, empire, class, 'improvement' [of the estate], the clergy, town versus country, abolition, the professions, female emancipation; whether her politics were Tory, Whig, or radical; whether she was a conservative or a revolutionary, or occupied a reformist position between these extremes".

| "... in all her novels Austen examines the female powerlessness that underlies monetary pressure to marry, the injustice of inheritance laws, the ignorance of women denied formal education, the psychological vulnerability of the heiress or widow, the exploited dependency of the spinster, the boredom of the lady provided with vocation" |

| — Gilbert Sandra Gilbert Sandra M. Gilbert , Professor Emerita of English at the University of California, Davis, is an influential literary critic and poet who has published widely in the fields of feminist literary criticism, feminist theory, and psychoanalytic criticism... and Gubar Susan Gubar Dr. Susan D. Gubar is an American academic and Distinguished Professor of English and Women's Studies at Indiana University. She is co-author with Dr. Sandra M. Gilbert of the standard feminist text, The Madwoman in the Attic and a trilogy on women's writing in the twentieth century.Her book... , The Madwoman in the Attic The Madwoman in the Attic The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination, published in 1979, examines Victorian literature from a feminist perspective... (1979) |

In the 1970s and 1980s, Austen studies was influenced by Sandra Gilbert

Sandra Gilbert

Sandra M. Gilbert , Professor Emerita of English at the University of California, Davis, is an influential literary critic and poet who has published widely in the fields of feminist literary criticism, feminist theory, and psychoanalytic criticism...

and Susan Gubar's

Susan Gubar

Dr. Susan D. Gubar is an American academic and Distinguished Professor of English and Women's Studies at Indiana University. She is co-author with Dr. Sandra M. Gilbert of the standard feminist text, The Madwoman in the Attic and a trilogy on women's writing in the twentieth century.Her book...

seminal The Madwoman in the Attic

The Madwoman in the Attic

The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination, published in 1979, examines Victorian literature from a feminist perspective...

(1979), which contrasts the "decorous surfaces" with the "explosive anger" of 19th-century female English writers. This work, along with other feminist criticism

Feminist literary criticism

Feminist literary criticism is literary criticism informed by feminist theory, or by the politics of feminism more broadly. Its history has been broad and varied, from classic works of nineteenth-century women authors such as George Eliot and Margaret Fuller to cutting-edge theoretical work in...

of Austen, has firmly positioned Austen as a woman writer. The interest generated in Austen by these critics led to the discovery and study of other woman writers of the time. Moreover, with the publication of Julia Prewitt Brown's Jane Austen's Novels: Social Change and Literary Form (1979), Margaret Kirkham's Jane Austen: Feminism and Fiction (1983), and Claudia L. Johnson's

Claudia L. Johnson (scholar)

Claudia L. Johnson is the Murray Professor of English Literature at Princeton University; she is also currently chairperson of the English department. Johnson specializes in Restoration and 18th-century British literature, with an especial focus on the novel. She is also interested in feminist...

Jane Austen: Women, Politics and the Novel (1988), scholars were no longer able to easily argue that Austen was "apolitical, or even unqualifiedly 'conservative'". Kirkham, for example, described the similarities between Austen's thought and that of Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft was an eighteenth-century British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. During her brief career, she wrote novels, treatises, a travel narrative, a history of the French Revolution, a conduct book, and a children's book...

, labelling them both as "Enlightenment feminists". Johnson similarly places Austen in an 18th-century political tradition, however, she outlines the debt Austen owes to the political novels of the 1790s written by women.

In the late-1980s, 1990s, and 2000s ideological, postcolonial

Postcolonialism

Post-colonialism is a specifically post-modern intellectual discourse that consists of reactions to, and analysis of, the cultural legacy of colonialism...

, and Marxist criticism

Marxist philosophy

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are terms that cover work in philosophy that is strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory or that is written by Marxists...

dominated Austen studies. Generating heated debate, Edward Said

Edward Said

Edward Wadie Saïd was a Palestinian-American literary theorist and advocate for Palestinian rights. He was University Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University and a founding figure in postcolonialism...

devoted a chapter of his book Culture and Imperialism

Culture and Imperialism

Culture and Imperialism is the 1993 sequel to Edward Said's highly influential book Orientalism from 1978.-Subject:In a series of essays, Said argues the impact of mainstream culture on colonialism and imperialism., and conversely how imperialism, resistance to it, and...

(1993) to Mansfield Park, arguing that the peripheral position of "Antigua" and the issue of slavery demonstrated that colonial oppression was an unspoken assumption of English society during the early 19th century. In Jane Austen and the Body: 'The Picture of Health, (1992) John Wiltshire explored the preoccupation with illness and health of Austen's characters. Wiltshire addressed current theories of "the body as sexuality", and more broadly how culture is "inscribed" on the representation of the body. There has also been a return to considerations of aesthetics

Aesthetics

Aesthetics is a branch of philosophy dealing with the nature of beauty, art, and taste, and with the creation and appreciation of beauty. It is more scientifically defined as the study of sensory or sensori-emotional values, sometimes called judgments of sentiment and taste...

with D. A. Miller's

D. A. Miller

D. A. Miller is an American literary critic, working mostly on the novel, especially of the Victorian era, as well as on film and different aspects of gender and sexuality studies...

Jane Austen, or The Secret of Style (2003) which connects artistic concerns with queer theory

Queer theory

Queer theory is a field of critical theory that emerged in the early 1990s out of the fields of LGBT studies and feminist studies. Queer theory includes both queer readings of texts and the theorisation of 'queerness' itself...

.

Modern Janeites

Pilgrim

A pilgrim is a traveler who is on a journey to a holy place. Typically, this is a physical journeying to some place of special significance to the adherent of a particular religious belief system...

s with those of Janeites, who travel to places associated with Austen's life, her novels and the film adaptations. She speculates that this is "a kind of time-travel to the past" which, by catering to Janeites, preserves a "vanished Englishness or set of 'traditional' values". The disconnection between the popular appreciation of Austen and the academic appreciation of Austen that began with Lascelles has since widened considerably. Johnson compares Janeites to Trekkie

Trekkie

A Trekkie or Trekker is a fan of the Star Trek franchise, or of specific television series or films within that franchise.-History:In 1967, science fiction editor Arthur W...

s, arguing that both "are derided and marginalized by dominant cultural institutions bent on legitimizing their own objects and protocols of expertise". However, she notes that Austen's works are now considered to be part of both high culture and popular culture, while Star Trek can only claim to be a part of popular culture.

Adaptations

Sequels, prequels, and adaptations based on Jane Austen's work range from attempts to enlarge on the stories in Austen's own style to the soft-core pornographic novel Virtues and Vices (1981) and fantasy novel Resolve and Resistance (1996). Beginning in the middle of the 19th century, Austen family members published conclusions to her incomplete novels. By 2000, there were over one hundred printed adaptations of Austen's works. According to Lynch, "her works appear to have proven more hospitable to sequelisation than those of almost any other novelist". Relying on the categories laid out by Betty A. Schellenberg and Paul Budra, Lynch describes two different kinds of Austen sequels: those that continue the story and those that return to "the world of Jane Austen". The texts that continue the story are "generally regarded as dubious enterprises, as reviews attest" and "often feel like throwbacks to the Gothic and sentimental novels that Austen loved to burlesque". Those that emphasise nostalgiaNostalgia

The term nostalgia describes a yearning for the past, often in idealized form.The word is a learned formation of a Greek compound, consisting of , meaning "returning home", a Homeric word, and , meaning "pain, ache"...

are "defined not only by retrograde longing but also by a kind of postmodern playfulness and predilection for insider joking", relying on the reader to see the web of Austenian allusions. Interest in Austen and adaptations of her novels have been common throughout the 20th century; between 1900 and 1975, more than sixty radio, television, film, and stage productions of Austen's various works were produced.

The first feature film adaptation of an Austen novel was the 1940 MGM

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc. is an American media company, involved primarily in the production and distribution of films and television programs. MGM was founded in 1924 when the entertainment entrepreneur Marcus Loew gained control of Metro Pictures, Goldwyn Pictures Corporation and Louis B. Mayer...

production of Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice (1940 film)

Pride and Prejudice is a 1940 film adaptation of Jane Austen's novel of the same name. Robert Z. Leonard directed, and Aldous Huxley served as one of the screenwriters of the film. It is adapted specifically from the stage adaptation by Helen Jerome in addition to Jane Austen's novel...

starring Laurence Olivier

Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier, OM was an English actor, director, and producer. He was one of the most famous and revered actors of the 20th century. He married three times, to fellow actors Jill Esmond, Vivien Leigh, and Joan Plowright...

and Greer Garson

Greer Garson

Greer Garson, CBE was a British-born actress who was very popular during World War II, being listed by the Motion Picture Herald as one of America's top ten box office draws in 1942, 1943, 1944, 1945, and 1946. As one of MGM's major stars of the 1940s, Garson received seven Academy Award...

. A Hollywood adaptation was first suggested by the entertainer Harpo Marx

Harpo Marx

Adolph "Harpo" Marx was an American comedian and film star. He was the second oldest of the Marx Brothers. His comic style was influenced by clown and pantomime traditions. He wore a curly reddish wig, and never spoke during performances...

, who had seen a dramatisation of the novel in Philadelphia in 1935, but production was delayed. Directed by Robert Z. Leonard

Robert Z. Leonard

Robert Zigler Leonard was an American film director, actor, producer and screenwriter.He was born in Chicago, Illinois...

and written in collaboration with English novelist Aldous Huxley

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley was an English writer and one of the most prominent members of the famous Huxley family. Best known for his novels including Brave New World and a wide-ranging output of essays, Huxley also edited the magazine Oxford Poetry, and published short stories, poetry, travel...

and American screenwriter Jane Murfin, the film was critically well-received although the plot and characterisations notably strayed from Austen's original. Filmed in a studio and in black and white, the story's setting was relocated to the 1830s with opulent costume designs.

Hollywood, Los Angeles, California

Hollywood is a famous district in Los Angeles, California, United States situated west-northwest of downtown Los Angeles. Due to its fame and cultural identity as the historical center of movie studios and movie stars, the word Hollywood is often used as a metonym of American cinema...

adaptations of Austen's novels, BBC

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation is a British public service broadcaster. Its headquarters is at Broadcasting House in the City of Westminster, London. It is the largest broadcaster in the world, with about 23,000 staff...

dramatisations from the 1970s onward aimed to adhere meticulously to Austen's plots, characterisations, and settings. The 1972 BBC adaptation of Emma

Emma (1972 TV serial)

Jane Austen's novel Emma was released on British television in 1972.This dramatization brings to life the wit and humour of Jane Austen's arguably finest novel Emma, recreating her most irritatingly endearing female character, of whom she wrote "no one but myself could like."Emma presides over the...

, for example, took great care to be historically accurate, but its slow pacing and long take

Long take

A long take is an uninterrupted shot in a film which lasts much longer than the conventional editing pace either of the film itself or of films in general, usually lasting several minutes. It can be used for dramatic and narrative effect if done properly, and in moving shots is often accomplished...

s contrasted unfavourably to the pace of commercial films. The BBC's 1980 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice adopted many film techniques—such as the use of long landscape shots—that gave the production a greater visual sophistication. Often seen as the start of the "heritage drama

Heritage film

The term Heritage film refers to a movement in British cinema in the late 20th century which depicts the England of previous centuries often in a nostalgic fashion. It includes the wave of filmings of Shakespeare plays and Jane Austen novels. Typical of such films is the use of splendid scenes of...

" movement, this production was the first to be filmed largely on location. A push for "fusion" adaptations, or films that combined Hollywood style and British heritage style, began in the mid-1980s. The BBC's first fusion adaptation was the 1986 production of Northanger Abbey

Northanger Abbey (1986 film)

Jane Austen's novel Northanger Abbey was adapted for television in 1986 by the A&E Network and the BBC.-Crew:*Giles Foster *Louis Marks *Ilona Sekacz *Nat Crosby...

, which combined authentic style and 1980s punk, with characters often veering into the surreal

Surrealism

Surrealism is a cultural movement that began in the early 1920s, and is best known for the visual artworks and writings of the group members....

.

A wave of Austen adaptations began to appear around 1995, starting with Emma Thompson's

Emma Thompson

Emma Thompson is a British actress, comedian and screenwriter. Her first major film role was in the 1989 romantic comedy The Tall Guy. In 1992, Thompson won multiple acting awards, including an Academy Award and a BAFTA Award for Best Actress, for her performance in the British drama Howards End...

1995 adaptation of Sense and Sensibility for Columbia Pictures

Columbia Pictures

Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. is an American film production and distribution company. Columbia Pictures now forms part of the Columbia TriStar Motion Picture Group, owned by Sony Pictures Entertainment, a subsidiary of the Japanese conglomerate Sony. It is one of the leading film companies...

, a fusion production directed by Ang Lee

Ang Lee

Ang Lee is a Taiwanese film director. Lee has directed a diverse set of films such as Eat Drink Man Woman , Sense and Sensibility , Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon , Hulk , and Brokeback Mountain , for which he won an Academy...

. This star-studded film departed from the novel in many ways, but it quickly became a commercial and critical success. It was nominated for numerous awards, including seven Oscars. The BBC produced two adaptations in 1995: the traditional telefilm Persuasion

Persuasion (1995 film)

Producer Fiona Finlay had for several years been interested in making a film based on the novel Persuasion, and approached screenwriter Nick Dear about adapting it for television...

and Andrew Davies's

Andrew Davies (writer)

Andrew Wynford Davies is a British author and screenwriter. He was made a Fellow of BAFTA in 2002.-Education and early career:...

immensely popular Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice (1995 TV serial)

Pride and Prejudice is a six-episode 1995 British television drama, adapted by Andrew Davies from Jane Austen's 1813 novel Pride and Prejudice. Jennifer Ehle and Colin Firth starred as Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy. Produced by Sue Birtwistle and directed by Simon Langton, the serial was a BBC...

. Starring Colin Firth

Colin Firth

SirColin Andrew Firth, CBE is a British film, television, and theatre actor. Firth gained wide public attention in the 1990s for his portrayal of Mr. Darcy in the 1995 television adaptation of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice...

and Jennifer Ehle

Jennifer Ehle

Jennifer Ehle is an American actress of stage and screen. She is known for her BAFTA winning role as Elizabeth Bennet in the 1995 mini-series Pride and Prejudice.-Early life:...

, Davies's film outshone the small-scale Persuasion and became a runaway success, igniting "Darcymania" in Britain and launching the stars' careers. Critics praised its smart departures from the novel as well as its sensual costuming, fast-paced editing, and original yet appropriate dialogue. This BBC production sparked an explosion in the publication of printed Austen adaptations; in addition, 200,000 video copies of the serial were sold within a year of its airing—50,000 were sold within the first week alone.

Books and scripts that use the general storyline of Austen's novels but change or otherwise modernise the story also became popular at the end of the 20th century. Clueless (1995), Amy Heckerling's

Amy Heckerling

Amy Heckerling is an American film director, one of the few female directors to have produced multiple box-office hits.-Early life:...

updated version of Emma that takes place in Beverly Hills

Beverly Hills, California

Beverly Hills is an affluent city located in Los Angeles County, California, United States. With a population of 34,109 at the 2010 census, up from 33,784 as of the 2000 census, it is home to numerous Hollywood celebrities. Beverly Hills and the neighboring city of West Hollywood are together...

, became a cultural phenomenon and spawned its own television series

Clueless (TV series)

Clueless is a television series spun off from the 1995 teen film of the same name . The series originally premiered on ABC on September 20, 1996 as a part of the TGIF lineup during its first season...

. Bridget Jones's Diary

Bridget Jones's Diary (film)

Bridget Jones's Diary is a 2001 British romantic comedy film based on Helen Fielding's novel of the same name. The adaptation stars Renée Zellweger as Bridget, Hugh Grant as the caddish Daniel Cleaver, and Colin Firth as Bridget's "true love", Mark Darcy...

(2001), based on the successful 1996 book of the same name

Bridget Jones's Diary

Bridget Jones's Diary is a 1996 novel by Helen Fielding. Written in the form of a personal diary, the novel chronicles a year in the life of Bridget Jones, a thirty-something single working woman living in London. She writes about her career, self-image, vices, family, friends, and romantic...

by Helen Fielding

Helen Fielding

Helen Fielding is an English novelist and screenwriter, best known as the creator of the fictional character Bridget Jones, a sequence of novels and films that chronicle the life of a thirtysomething single woman in London as she tries to make sense of life and love.Her novels Bridget Jones's...

, was inspired by both Pride and Prejudice and the 1995 BBC adaptation. The Bollywood

Bollywood

Bollywood is the informal term popularly used for the Hindi-language film industry based in Mumbai , Maharashtra, India. The term is often incorrectly used to refer to the whole of Indian cinema; it is only a part of the total Indian film industry, which includes other production centers producing...

esque production Bride and Prejudice

Bride and Prejudice

Bride and Prejudice is a 2004 romantic musical film directed by Gurinder Chadha. The screenplay by Chadha and Paul Mayeda Berges is a Bollywood-style adaptation of Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen. It was filmed primarily in English, with some Hindi and Punjabi dialogue. The film released in...

, which sets Austen's story in present-day India while including original musical numbers, premiered in 2004. Yet another adaptation of Pride and Prejudice

Pride & Prejudice (2005 film)

Pride & Prejudice is a 2005 British romance film directed by Joe Wright. It is a film adaptation of the 1813 novel of the same name by Jane Austen and the second adaption produced by Working Title Films. It was released on September 16, 2005, in the UK and on November 11, 2005, in the...

was released the following year. Starring Keira Knightley

Keira Knightley

Keira Christina Knightley born 26 March 1985) is an English actress and model. She began acting as a child and came to international notice in 2002 after co-starring in the film Bend It Like Beckham...

, who was nominated for an Academy Award for her portrayal of Elizabeth Bennet, Joe Wright's

Joe Wright

Joe Wright is an English film director best known for Pride and Prejudice, Atonement and Hanna.-Early life and career:...

film marked the first feature adaptation since 1940 that aspired to be faithful to the novel.

External links

- Chapman's Collected Works of Austen - Volume 1 at the Internet ArchiveInternet ArchiveThe Internet Archive is a non-profit digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It offers permanent storage and access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, music, moving images, and nearly 3 million public domain books. The Internet Archive...

- Chapman's Collected Works of Austen - Volume 2 at the Internet Archive

- Chapman's Collected Works of Austen - Volume 4 at the Internet Archive

- Chapman's Collected Works of Austen - Volume 5 at the Internet Archive