Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust

Encyclopedia

Holocaust in Poland

The Holocaust, also known as haShoah , was a genocide officially sanctioned and executed by the Third Reich during World War II. It took the lives of three million Polish Jews, destroying an entire civilization. Only a small percentage survived or managed to escape beyond the reach of the Nazis...

of the German Nazi-organized Holocaust. Throughout the German occupation of Poland, many Polish Gentiles risked their own lives—and the lives of their families—to rescue Jews from the Nazis. Grouped by nationality, Poles represent the biggest number of people who rescued Jews during the Holocaust. To date, 6,135 Poles have been awarded the title of Righteous among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous among the Nations of the world's nations"), also translated as Righteous Gentiles is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from extermination by the Nazis....

by the State of Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

—more than any other nation.

The Polish resistance alerted the world to the Holocaust, notably with the reports of Witold Pilecki

Witold Pilecki

Witold Pilecki was a soldier of the Second Polish Republic, the founder of the Secret Polish Army resistance group and a member of the Home Army...

and Jan Karski

Jan Karski

Jan Karski was a Polish World War II resistance movement fighter and later scholar at Georgetown University. In 1942 and 1943 Karski reported to the Polish government in exile and the Western Allies on the situation in German-occupied Poland, especially the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto, and...

. The Polish government in exile

Polish government in Exile

The Polish government-in-exile, formally known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in Exile , was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which...

and the Polish Secret State

Polish Secret State

The Polish Underground State is a collective term for the World War II underground resistance organizations in Poland, both military and civilian, that remained loyal to the Polish Government in Exile in London. The first elements of the Underground State were put in place in the final days of the...

asked for American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

help to stop the Holocaust, to no avail.

Some estimates put the number of Poles involved in rescue at up to 3 million, and credit Poles with saving up to around 450,000 Jews from certain death. The rescue efforts were aided by one of the largest anti-Nazi resistance movements in Europe, the Polish Underground State and its military arm, the Armia Krajowa

Armia Krajowa

The Armia Krajowa , or Home Army, was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II German-occupied Poland. It was formed in February 1942 from the Związek Walki Zbrojnej . Over the next two years, it absorbed most other Polish underground forces...

. Supported by the Polish government in exile

Polish government in Exile

The Polish government-in-exile, formally known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in Exile , was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which...

, these organizations operated special units dedicated to helping Jews; of those, the most notable was Żegota

Zegota

"Żegota" , also known as the "Konrad Żegota Committee", was a codename for the Polish Council to Aid Jews , an underground organization of Polish resistance in German-occupied Poland from 1942 to 1945....

.

Polish citizens were hampered by the most extreme conditions in all of German-occupied Europe. Nazi-occupied Poland was the only territory where the Germans decreed that any kind of help for Jews was punishable by death. Up to 50,000 Polish gentiles were executed by the Nazis for saving Jews. Of the estimated 3 million Polish Gentiles killed in World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, thousands were murdered by the German Nazis only as punishment for assisting Jews. After the War most of this information was suppressed by the Soviet-backed regime in an attempt to discredit Polish prewar society and government as reactionary.

Numbers

Before World War II, 3,300,000 Jewish people lived in PolandHistory of the Jews in Poland

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back over a millennium. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Jewish community in the world. Poland was the centre of Jewish culture thanks to a long period of statutory religious tolerance and social autonomy. This ended with the...

– ten percent of the general population of some 33 million. Poland was the center of the European Jewish world.

The Second World War began with the Nazi German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939; and, on September 17, in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement, the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

attacked Poland

Soviet invasion of Poland

Soviet invasion of Poland can refer to:* the second phase of the Polish-Soviet War of 1920 when Soviet armies marched on Warsaw, Poland* Soviet invasion of Poland of 1939 when Soviet Union allied with Nazi Germany attacked Second Polish Republic...

from the east. By October 1939, the Second Polish Republic

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

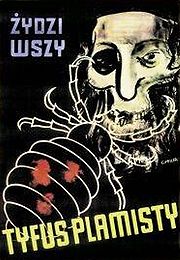

was divided between the two totalitarian powers, with Nazi Germany occupying western and central Poland. The Germans regarded Poles as "sub-human" and Polish Jews somewhere beneath that category, treating both groups with extreme and brutal harshness. One aspect of German policy in conquered Poland was to prevent its ethnically diverse population from uniting against Germany. The Nazi plans for Polish Jews was one of concentration, isolation, and eventually total annihilation in what is now known as the Holocaust or Shoa. Nazi plans for the Polish Catholic majority focused on the murder or suppression of political, religious, and intellectual leaders as well as the Germanization of the annexed lands which included a program to resettle Germans from the Baltic and other regions onto farms, ventures and homes formerly owned by Poles and Jews.

The response of the Polish majority to the Jewish Holocaust covered an extremely wide spectrum, often ranging from acts of altruism

Altruism

Altruism is a concern for the welfare of others. It is a traditional virtue in many cultures, and a core aspect of various religious traditions, though the concept of 'others' toward whom concern should be directed can vary among cultures and religions. Altruism is the opposite of...

at the risk of endangering their own and their families’ lives, through compassion, to passivity, indifference, and outright brutality. Polish rescuers also faced threats from unsympathetic neighbours, the Volksdeutsche

Volksdeutsche

Volksdeutsche - "German in terms of people/folk" -, defined ethnically, is a historical term from the 20th century. The words volk and volkische conveyed in Nazi thinking the meanings of "folk" and "race" while adding the sense of superior civilization and blood...

and the ethnic Ukrainian pro-Nazis, as well as blackmailers called szmalcownik

Szmalcownik

Szmalcownik is a pejorative Polish slang word used during World War II that denoted a person blackmailing Jews who were hiding, or blackmailing Poles who protected Jews during the Nazi occupation...

s and (as in Warsaw) from Jewish collaborators such as Żagiew

Zagiew

Żagiew was a collaborationist Jewish organisation in German Nazi-occupied Warsaw, founded by the Germans in February 1943, during World War II at the beginning of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising...

or Group 13

Group 13

"The Group Thirteen" network was a Jewish collaborationist organisation in the Warsaw Ghetto during the Second World War. The Thirteen took its informal name from the address of its main office in Leszno Street 13. The group was founded in December 1940 and led by Abraham Gancwajch, the former...

. There were cases of denunciation or even participation in massacres

Jedwabne pogrom

The Jedwabne pogrom of July 1941 during German occupation of Poland, was a massacre of at least 340 Polish Jews of all ages. These are the official findings of the Institute of National Remembrance, "confirmed by the number of victims in the two graves, according to the estimate of the...

of Jewish inhabitants. The guidelines for such massacres were formulated by Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich , also known as The Hangman, was a high-ranking German Nazi official.He was SS-Obergruppenführer and General der Polizei, chief of the Reich Main Security Office and Stellvertretender Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia...

, who ordered his chiefs to induce anti-Jewish pogroms on territories newly occupied by the German forces. Statistics of the Israeli War Crimes Commission indicate that less than a tenth of 1 per cent of Polish gentiles collaborated with the Nazis.

Forced labor in Germany during World War II

The use of forced labour in Nazi Germany and throughout German-occupied Europe during World War II took place on an unprecedented scale. It was a vital part of the German economic exploitation of conquered territories. It also contributed to the mass extermination of populations in German-occupied...

. Others directed Jewswho managed to escape from the ghetto

Ghetto

A ghetto is a section of a city predominantly occupied by a group who live there, especially because of social, economic, or legal issues.The term was originally used in Venice to describe the area where Jews were compelled to live. The term now refers to an overcrowded urban area often associated...

sto people who could help them. Some sheltered Jews for only one or a few nights, others assumed full responsibility for the Jews' survival, well aware that the Nazis punished those who helped Jews by summary killings. A special role fell to the Polish medical doctors who alone saved thousands of Jews through their subversive practise. For example, Dr.

Doctor (title)

Doctor, as a title, originates from the Latin word of the same spelling and meaning. The word is originally an agentive noun of the Latin verb docēre . It has been used as an honored academic title for over a millennium in Europe, where it dates back to the rise of the university. This use spread...

Eugeniusz Łazowski, known as Polish 'Schindler', saved 8,000 Polish Jews from deportation to death camps, by faking an epidemic of typhus in the town of Rozwadów

Rozwadów

Rozwadów is a suburb of Stalowa Wola, Poland. Founded as a town in 1690, it was incorporated into Stalowa Wola in 1973. The Rozwadów suburb of Stalowa Wola included a thriving Jewish shtetl prior to World War II, closely associated with the Jewish communities of Tarnobrzeg and other nearby...

. Free medicine was given out in the Kraków Ghetto

Kraków Ghetto

The Kraków Ghetto was one of five major, metropolitan Jewish ghettos created by Nazi Germany in the General Government territory for the purpose of persecution, terror, and exploitation of Polish Jews during the German occupation of Poland in World War II...

by Tadeusz Pankiewicz

Tadeusz Pankiewicz

Tadeusz Pankiewicz , was a Polish Roman Catholic pharmacist, operating in the Kraków Ghetto during the Nazi German occupation of Poland...

saving unspecified number of Jews. Rudolf Weigl

Rudolf Weigl

Professor Rudolf Stefan Weigl was a famous Polish biologist and inventor of the first effective vaccine against epidemic typhus. Weigl founded the Weigl Institute in Lwów, Poland , where he did his vaccine-producing research.Of Austrian ethnic descent, Weigl was born in Přerov, Moravia...

employed and protected Jews in his Institute in Lwów. His vaccines were smuggled into the local ghetto as well as the ghetto in Warsaw

Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest of all Jewish Ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II. It was established in the Polish capital between October and November 15, 1940, in the territory of General Government of the German-occupied Poland, with over 400,000 Jews from the vicinity...

saving countless lives. It is mostly those who took full responsibility who qualify for the title of the Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous among the Nations of the world's nations"), also translated as Righteous Gentiles is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from extermination by the Nazis....

. To date, a total of 6,066 Poles have been officially recognized by Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

as the Polish Righteous among the Nations

Polish Righteous among the Nations

Polish citizens have the world's highest count of individuals awarded medals of Righteous among the Nations, given by the State of Israel to non-Jews who saved Jews from extermination during the Holocaust...

for their efforts in rescuing Polish Jews during the Holocaust, making Poland the country with the highest number of Righteous in the world.

The number of Poles who rescued Jews from the Nazi persecution would be hard to determine in black-and-white terms, and is still the subject of scholarly debate. According to Gunnar S. Paulsson

Gunnar S. Paulsson

Gunnar Svante Paulsson is a Swedish-born Canadian historian who has taught in Britain and Canada.Paulsson graduated Oxford University with a D.Phil. in 1998...

, the number of rescuers that meet Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem is Israel's official memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, established in 1953 through the Yad Vashem Law passed by the Knesset, Israel's parliament....

's criteria is perhaps 100,000, and there may have been two or three times as many who offered minor forms of help, while the majority "were passively protective." In an article published in the Journal of Genocide Research

Journal of Genocide Research

The Journal of Genocide Research ' is a peer-reviewed academic journal that covers the field of genocide studies. Subject areas include: Peace and conflict studies, Human rights, international relations, security policies, conflict resolution, holocaust studies, history and international law.The...

, Hans G. Furth

Hans G. Furth

Hans G. Furth , was a Professor emeritus in the Faculty of Psychology of the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., at the time of his death aged 78.-Early Life in Europe:...

estimated that there may have been as many as 1,200,000 Polish rescuers.

Richard C. Lukas

Richard C. Lukas

Richard C. Lukas is an American historian and author of numerous books and articles on Polish history and Polish-Jewish relations. He is recognized as a leading authority on Poland during World War II....

estimated that upwards of 1,000,000 Poles were involved in such rescue efforts, "but some estimates go as high as three million." Lukas also cites Władysław Bartoszewski, a wartime member of Żegota

Zegota

"Żegota" , also known as the "Konrad Żegota Committee", was a codename for the Polish Council to Aid Jews , an underground organization of Polish resistance in German-occupied Poland from 1942 to 1945....

, as having estimated that "at least several hundred thousand Poles ... participated in various ways and forms in the rescue action." Elsewhere, Bartoszewski has estimated that between 1 and 3 percent of the Polish population was actively involved in rescue efforts; Marcin Urynowicz estimates that a minimum of from 500 thousand to over a million Poles actively tried to help Jews. Teresa Prekerowa has estimated that between 160,000 and 360,000 Poles assisted in hiding Jews, amounting to between 1 and 2.5% of the 15 million adult Poles she categorizes as "those who could offer help. Prekerowa arrived at her estimate by assuming that it took two or three non-Jewish Poles to hide one Jew, while other sources indicate that a much higher number was involved (e.g., Paulsson estimates that it might have taken a "dozen or more" people for each person hidden). Prekerowa's estimation only counts those who were involved in hiding Jews directly and does not include those who were involved in other types of rescue efforts. It also assumes that each Jew who hid among the non-Jewish populace stayed through-out the war in only one hiding place and as such had only one set of helpers; Paulsson, on the other hand, wrote that an average Jew in hiding stayed in seven different places throughout the war.

According to Paulsson, an average Jew who survived in occupied Poland depended not on the actions of a single person, but on many acts of assistance and tolerance. As Paulsson notes: "nearly every Jew that was rescued, was rescued by the cooperative efforts of dozen or more people". During the six years of wartime and occupation, the average Jew was sheltered in seven different locations, had three or four sets of documents, two or three encounters with blackmailers, and faced recognition as a Jew multiple times.

Father John T. Pawlikowski

John T. Pawlikowski

John T. Pawlikowski living in Chicago is a Servite priest and Professor of Social Ethics at the Catholic Theological Union.As member of the Catholic Theological Union since 1968, Pawlikowski was appointed to the United States Holocaust Memorial Council in 1980 by then-President Jimmy Carter. He was...

referring to work by other historians speculated that claims of hundreds of thousands of rescuers struck him as inflated. Martin Gilbert

Martin Gilbert

Sir Martin John Gilbert, CBE, PC is a British historian and Fellow of Merton College, University of Oxford. He is the author of over eighty books, including works on the Holocaust and Jewish history...

has written that under Nazi regime, rescuers were an exception, albeit one that could be found in towns and villages throughout Poland.

There is no official number of how many Polish Jews were hidden by their Christian countrymen during wartime. Lukas estimated that the number of Jews sheltered by Poles at one time might have been "as high as 450,000." However, concealment did not automatically assure complete safety from the Nazis, and the number of Jews in hiding who were caught has been estimated variously from 40,000 to 200,000.

Difficulties

Israel Gutman

Israel Gutman is a Polish-born Israeli historian of the Holocaust.Israel Gutman was born in Warsaw, Poland. After playing an important role in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, he was deported to the Majdanek, Auschwitz and Mauthausen concentration camps. His older sister died in the ghetto. After...

has written that the majority of Jews who were sheltered by Poles paid for their own protection, but sadly, a large number of Polish protectors perished along with the people they were hiding.

There is general consensus among scholars that, unlike in Western Europe, Polish collaboration with the Nazis was insignificant. However, the Nazi terror combined with inadequacy of food rations, as well as German greed and the system of corruption as the only "one language the Germans understood well", wrecked traditional values. Poles helping Jews faced unparalleled dangers not only from the German occupiers but also from their own ethnically diverse countrymen including Volksdeutsche

Volksdeutsche

Volksdeutsche - "German in terms of people/folk" -, defined ethnically, is a historical term from the 20th century. The words volk and volkische conveyed in Nazi thinking the meanings of "folk" and "race" while adding the sense of superior civilization and blood...

, and Polish Ukrainians, who were anti-Semitic and morally disoriented by the war. There were people, the so called szmalcownicy ("shmalts people" from shmalts or szmalec, Yiddish and Polish for “grease” and slang term for money), who blackmailed the hiding Jews and Poles helping the Jews, or who turned them to the Germans for a reward. Outside the cities there were also some peasants looking for Jews who hid in the forests to demand money or turn them over to the Germans for a reward. The vast majority of these individuals joined the criminal underworld only after the German occupation and were responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of people, both Jews and the Poles who were trying to save them.

The threat of denunciation not only deterred many Jews from attempting to find shelter among Poles, but also forestalled Poles of good will who feared denunciators.

According to one reviewer of Paulsson, with regard to the extortionists, "a single hooligan or blackmailer could wreak severe damage on Jews in hiding, but it took the silent passivity of a whole crowd to maintain their cover." He also notes that "hunters" were outnumbered by "helpers" by a ratio of one to 20 or 30. According to Lukas the number of renegades who blackmailed and denounced Jews and their Polish protectors probably did not number more than 1,000 individuals out of the 1,300,000 people living in Warsaw in 1939.

Michael C. Steinlauf

Michael C. Steinlauf is an Associate Professor of History at Gratz College, Pennsylvania. Steinlauf teaches Jewish history and culture in Eastern Europe and Polish-Jewish relations. He is the author and editor focused on studies of Jewish popular culture in Poland. His work has been translated into...

writes that not only the fear of the death penalty was an obstacle limiting Polish aid to Jews, but also some prewar attitudes towards Jews, which made many individuals uncertain of their neighbors' reaction to their attempts at rescue. Number of authors have noted the negative consequences of the hostility towards Jews by extremists advocating their eventual removal from Poland. Meanwhile, Alina Cala in her study of Jews in Polish folk culture argued also for the persistence of traditional religious antisemitism and anti-Jewish propaganda before and during the war both leading to indifference. Steinlauf however notes that despite these uncertainties, Jews were helped by countless thousands of individual Poles throughout the country. He writes that "not the informing or the indifference, but the existence of such individuals is one of the most remarkable features of Polish-Jewish relations during the Holocaust." Nechama Tec

Nechama Tec

Nechama Tec is a Professor Emerita of Sociology at the University of Connecticut. She received her Ph.D. in sociology at Columbia University, where she studied and worked with the highly-regarded sociologist Daniel Bell, and is a noted Holocaust scholar...

, who herself survived the war aided by a group of Catholic Poles, noted that Polish rescuers worked within an environment that was hostile to Jews and unfavorable to their protection, in which rescuers feared both the disapproval of their neighbors and reprisals that such disapproval might bring. Tec also noted that Jews, for many complex and practical reasons, were not always prepared to accept assistance that was available to them. Some Jews did not expect help from their Polish neighbors — in fact, some were surprised to have been aided by some people who expressed antisemitic attitudes before the war. Similar sentiment was expressed by Mordecai Paldiel, former Director of the Department of the Righteous

Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous among the Nations of the world's nations"), also translated as Righteous Gentiles is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from extermination by the Nazis....

at Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem is Israel's official memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, established in 1953 through the Yad Vashem Law passed by the Knesset, Israel's parliament....

, who writes that the widespread revulsion at the murders being committed by the Nazis was sometimes accompanied by a feeling of relief at the disappearance of Jews. A Yad Vashem study of Żegota

Zegota

"Żegota" , also known as the "Konrad Żegota Committee", was a codename for the Polish Council to Aid Jews , an underground organization of Polish resistance in German-occupied Poland from 1942 to 1945....

cites an interview, in which the organization's Deputy Chairman, Tadeusz Rek, mentions his report to the representatives of the Polish government-in-exile claiming "that the overwhelming majority of Polish society are hostile toward those extending relief." Paulsson and Pawlikowski write that overall, such negative attitudes were not a major factor impeding the survival of sheltered Jews, or the work of the rescue organization Żegota.

The fact that the Polish Jewish community was decimated during World War II, coupled with stories about Polish collaborators, has contributed, especially among Israelis and American Jews, to a lingering stereotype

Stereotype

A stereotype is a popular belief about specific social groups or types of individuals. The concepts of "stereotype" and "prejudice" are often confused with many other different meanings...

that the Polish population has been passive in regard to, or even supportive of, Jewish suffering. However, modern scholarship has not validated the claim that Polish antisemitism was irredeemable or different from contemporary Western antisemitism; it has also found that such claims are among the stereotypes that comprise anti-Polonism. The presenting of selective evidence in support of preconceived notions have led some popular press to draw overly simplistic and often misleading conclusions regarding the role played by Poles at the time of the Holocaust.

Punishment for aiding the Jews

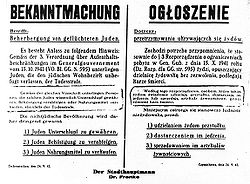

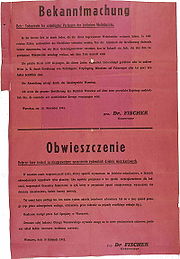

On November 10, 1941, the death penalty was introduced by Hans Frank

Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank was a German lawyer who worked for the Nazi party during the 1920s and 1930s and later became a high-ranking official in Nazi Germany...

, governor of the General Government

General Government

The General Government was an area of Second Republic of Poland under Nazi German rule during World War II; designated as a separate region of the Third Reich between 1939–1945...

, to apply to Poles who helped Jews "in any way: by taking them in for the night, giving them a lift in a vehicle of any kind" or "feed[ing] runaway Jews or sell[ing] them foodstuffs." The law was made public by posters distributed in all major cities.

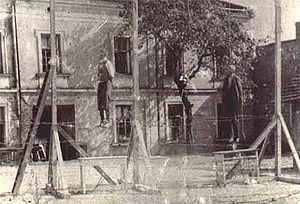

The imposition of the death penalty for Poles aiding Jews was unique to Poland among all Nazi occupied countries, and was a result of the conspicuous and spontaneous nature of such an aid. For example, the Ulma family

Józef and Wiktoria Ulma

Józef and Wiktoria Ulma, a Polish husband and wife, living in Markowa near Rzeszów in south-eastern Poland during the Nazi German occupation in World War II, were the Righteous who attempted to rescue Polish Jewish families by hiding them in their own home during the Holocaust...

(father, mother and six children) of the village of Markowa

Markowa

Markowa is a village in Łańcut County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in south-eastern Poland. It is the seat of the gmina called Gmina Markowa. It lies approximately south-east of Łańcut and east of the regional capital Rzeszów...

near Łańcut – where many families concealed their Jewish neighbors – were executed jointly by the Nazis with the eight Jews they hid. The entire Wołyniec family in Romaszkańce was massacred for sheltering three Jewish refugees from a ghetto. In Maciuńce, for hiding Jews, the Germans shot eight members of Józef Borowski family along with him and four guests who happened to be there. Nazi death squads carried out mass executions of the entire villages that were discovered to be aiding Jews on a communal level. In the villages of Białka near Parczew

Parczew

Parczew is a town in eastern Poland, with a population of 10,281 . Situated in the Lublin Voivodeship , previously in Biała Podlaska Voivodeship . It is the capital of Parczew County.-History:...

and Sterdyń

Gmina Sterdyn

Gmina Sterdyń is a rural gmina in Sokołów County, Masovian Voivodeship, in east-central Poland. Its seat is the village of Sterdyń, which lies approximately 19 kilometres north of Sokołów Podlaski and 95 km north-east of Warsaw.The gmina covers an area of , and as of 2006 its total population is...

near Sokołów Podlaski, 150 villagers were massacred for sheltering Jews. In November 1942, the Ukrainian SS squad executed 20 villagers from Berecz in Wołyń Voivodeship for giving aid to Jewish escapees from the ghetto in Povorsk. Michał Kruk and several other people in Przemyśl

Przemysl

Przemyśl is a city in south-eastern Poland with 66,756 inhabitants, as of June 2009. In 1999, it became part of the Podkarpackie Voivodeship; it was previously the capital of Przemyśl Voivodeship....

were executed on September 6, 1943 (pictured) for the assistance they had rendered to the Jews. Altogether, in the town and its environs 415 Jews (including 60 children) were saved, in return for which the Germans killed 568 people of Polish nationality. Several hundred Poles were massacred with their priest, Adam Sztark, in Słonim on December 18, 1942, for sheltering Jews in a church. In Huta Stara

Huta Stara

Huta Stara is a small village in the administrative district of Gmina Krasocin, within Włoszczowa County, Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship, in south-central Poland. It lies approximately east of Krasocin, east of Włoszczowa, and west of the regional capital Kielce.The village has a population of...

near Buczacz, Polish Christians and the Jewish countrymen they protected, were herded into a church by the Nazis and burned alive on March 4, 1944. In the years 1942-1944 about 200 peasants were shot dead and burned alive as punishment in the Kielce

Kielce

Kielce ) is a city in central Poland with 204,891 inhabitants . It is also the capital city of the Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship since 1999, previously in Kielce Voivodeship...

region alone.

Lakhva

Lakhva is a small town in southern Belarus, with a population of approximately 2100. Lakhva is considered to have been the location of one of the first, and possibly the first, Jewish ghetto uprisings of the Second World War.-Geography:Lakhva is located in the Luninets district of the Brest...

, Huta Pieniacka

Huta Pieniacka

Huta Pieniacka – was an ethnic Polish village of about 1,000 inhabitants, until 1939 located in Tarnopol Voivodeship, Poland...

near Brody

Brody

Brody is a city in the Lviv Oblast of western Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Brody Raion , and is located in the valley of the upper Styr River, approximately 90 kilometres northeast of the oblast capital, Lviv...

or Stara Huta

Stara Huta, Garwolin County

Stara Huta is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Garwolin, within Garwolin County, Masovian Voivodeship, in east-central Poland. It lies approximately west of Garwolin and south-east of Warsaw.-References:...

near Szumsk

Szumsk

Szumsk is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Dzierzgowo, within Mława County, Masovian Voivodeship, in east-central Poland. It lies approximately south-east of Dzierzgowo, east of Mława, and north of Warsaw.-References:...

.

Additionally, after the end of the war Poles who saved Jews during the Nazi occupation very often became the victims of repression at the hands of the communist security apparatus

Ministry of Public Security of Poland

The Ministry of Public Security of Poland was a Polish communist secret police, intelligence and counter-espionage service operating from 1945 to 1954 under Jakub Berman of the Politburo...

, due to their instinctive devotion to social justice which they saw as being abused by the government.

Jews in Polish villages

A number of Polish villages in their entirety provided shelter from Nazi apprehension, offering protection for their Jewish neighbors as well as the aid for refugees from other villages and escapees from the ghettos. Postwar research has confirmed that communal protection occurred in Głuchów near Łańcut with everyone engaged, as well as in the villages of Główne, OzorkówOzorków

Ozorków is a town in central Poland with 20,731 inhabitants , located on the Bzura River. It is situated in the Łódź Voivodeship , having previously been in Łódź Metro Voivodeship .- External links :* * *...

, Borkowo

Borkowo Wielkie, Masovian Voivodeship

Borkowo Wielkie is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Sierpc, within Sierpc County, Masovian Voivodeship, in east-central Poland. It lies approximately south-east of Sierpc and north-west of Warsaw.-References:...

near Sierpc

Sierpc

Sierpc is a town in Poland, in the north-west part of the Masovian Voivodeship, about 125 km northwest of Warsaw. It is the capital of Sierpc County. Its population is 18,777 . It is located near the national road No 10, which connects Warsaw and Toruń...

, Dąbrowica

Dabrowica, Nisko County

Dąbrowica is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Ulanów, within Nisko County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in south-eastern Poland. It lies approximately east of Ulanów, east of Nisko, and north-east of the regional capital Rzeszów....

near Ulanów

Ulanów

Ulanów is a town in Nisko County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, Poland, with 1,491 inhabitants .It has grammar and high schools along with 2 churches. One of the churches was set on fire in 2004, it was closed for a repairs and after about a year they opened the church again. Every year in June a...

, in Głupianka near Otwock

Otwock

Otwock is a town in central Poland, some southeast of Warsaw, with 42,765 inhabitants . It is situated on the right bank of Vistula River below the mouth of Swider River. Otwock is home to a unique architectural style called Swidermajer....

, and Teresin near Chełm.

The forms of protection varied from village to village. In Gołąbki, the farm of Jerzy and Irena Krępeć

Jerzy and Irena Krepec

Jerzy and Irena Krępeć, a Polish husband and wife, living in Gołąbki near Warsaw during Nazi German occupation of Poland in World War II, were the Righteous who rescued Polish Jews with families including refugees from the Ghetto in Warsaw during the Holocaust.- The ceremonies :Jerzy and Irena...

provided a hiding place for as many as 30 Jews; years after the war, the couple's son recalled in an interview with the Montreal Gazette

The Gazette (Montreal)

The Gazette, often called the Montreal Gazette to avoid ambiguity, is the only English-language daily newspaper published in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, with three other daily English newspapers all having shut down at different times during the second half of the 20th century.-History:In 1778,...

that their actions were "an open secret in the village [that] everyone knew they had to keep quiet" and that the other villagers helped, "if only to provide a meal." Another farm couple, Alfreda and Bolesław Pietraszek, provided shelter for Jewish families consisting of 18 people in Ceranów

Gmina Ceranów

Gmina Ceranów is a rural gmina in Sokołów County, Masovian Voivodeship, in east-central Poland. Its seat is the village of Ceranów, which lies approximately north of Sokołów Podlaski and north-east of Warsaw....

near Sokołów Podlaski, and their neighbors brought food to those being rescued.

Two decades after the end of the war, a Jewish partisan named Gustaw Alef-Bolkowiak identified the following villages in the Parczew

Parczew

Parczew is a town in eastern Poland, with a population of 10,281 . Situated in the Lublin Voivodeship , previously in Biała Podlaska Voivodeship . It is the capital of Parczew County.-History:...

-Ostrów Lubelski

Ostrów Lubelski

Ostrów Lubelski is a town in Gmina Ostrów Lubelski in Lubartów County, Lublin Voivodeship in Poland. Within the territory of the town and commune there are three lakes. These are Miejskie Lake, Kleszczów Lake and Czarne Lake. The commune is a typically agricultural area...

area where "almost the entire population" assisted Jews: Rudka

Rudka Kijanska

Rudka Kijańska is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Ostrów Lubelski, within Lubartów County, Lublin Voivodeship, in eastern Poland. It lies approximately south of Ostrów Lubelski, east of Lubartów, and north-east of the regional capital Lublin.-References:...

, Jedlanka

Jedlanka, Lublin Voivodeship

Jedlanka is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Stoczek Łukowski, within Łuków County, Lublin Voivodeship, in eastern Poland. It lies approximately east of Stoczek Łukowski, west of Łuków, and north of the regional capital Lublin....

, Makoszka

Makoszka

Makoszka is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Dębowa Kłoda, within Parczew County, Lublin Voivodeship, in eastern Poland. It lies approximately west of Dębowa Kłoda, south-east of Parczew, and north-east of the regional capital Lublin....

, Tyśmienica, and Bójki

Bójki

Bójki is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Ostrów Lubelski, within Lubartów County, Lublin Voivodeship, in eastern Poland. It lies approximately north of Ostrów Lubelski, north-east of Lubartów, and north-east of the regional capital Lublin....

. Historians have documented that a dozen villagers of Mętów

Metów

Mętów is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Głusk, within Lublin County, Lublin Voivodeship, in eastern Poland. It lies approximately south of the regional capital Lublin.The village has a population of 890.-References:...

near Głusk outside Lublin

Lublin

Lublin is the ninth largest city in Poland. It is the capital of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 350,392 . Lublin is also the largest Polish city east of the Vistula river...

sheltered Polish Jews.

In some documented cases, Polish Jews who were hidden were circulated between locations in a village. Farmers in Zdziebórz near Wyszków

Wyszków

Wyszków is a town in northeastern Poland with 26,500 inhabitants . It is the capital of Wyszków County . Wyszków is situated in the Masovian Voivodeship ; previously it was in Warsaw Voivodeship and Ostrołęka Voivodeship .-Description:The village of Wyszków was first documented in 1203. The town...

, by turns, sheltered two Jewish men who later joined the Polish resistance Armia Krajowa

Armia Krajowa

The Armia Krajowa , or Home Army, was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II German-occupied Poland. It was formed in February 1942 from the Związek Walki Zbrojnej . Over the next two years, it absorbed most other Polish underground forces...

(Home Army). The entire village of Mulawicze

Mulawicze

Mulawicze is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Wyszki, within Bielsk County, Podlaskie Voivodeship, in north-eastern Poland. It lies approximately east of Wyszki, north-west of Bielsk Podlaski, and south of the regional capital Białystok....

near Bielsk Podlaski

Bielsk Podlaski

-Roads and Highways:Bielsk Podlaski is at the intersection of two National Road and a Voivodeship Road:* National Road 19 - Kuźnica Białystoka Border Crossing - Kuźnica - Białystok - Bielsk Podlaski - Siemiatycze - Międzyrzec Podlaski - Kock - Lubartów - Lublin - Kraśnik - Janów Lubelski - Nisko...

took responsibility for the survival of an orphaned nine-year-old Jewish boy. Different families took turns hiding a Jewish girl at various homes in Wola Przybysławska near Lublin

Lublin

Lublin is the ninth largest city in Poland. It is the capital of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 350,392 . Lublin is also the largest Polish city east of the Vistula river...

, and around Jabłoń near Parczew

Parczew

Parczew is a town in eastern Poland, with a population of 10,281 . Situated in the Lublin Voivodeship , previously in Biała Podlaska Voivodeship . It is the capital of Parczew County.-History:...

many Polish Jews successfully sought refuge.

Impoverished Polish Jews, unable to offer any money in return, were nonetheless provided with food, clothing, shelter and money by some small communities; historians have confirmed this took place in the villages of Czajków

Gmina Staszów

Gmina Staszów is an urban-rural gmina in Staszów County, Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship, in south-central Poland. Its seat is the town of Staszów, which lies approximately south-east of the regional capital Kielce....

near Staszów

Staszów

Staszów is a town in Poland, in Świętokrzyskie Voivodship, about 54 km southeast of Kielce. It is the capital of Staszów County. Population is 15,108 .- Demography :...

as well as several villages near Łowicz, in Korzeniówka near Grójec

Grójec

Grójec is a town in Poland. Located in the Masovian Voivodeship, about 40 km south of Warsaw, it is the capital of Grójec County. It has about 14,875 inhabitants . Grójec surroundings are considered to be the biggest apple-growing area of Poland. It is said, that the region makes up also for...

, near Żyrardów

Zyrardów

Żyrardów is a town in central Poland with 41,400 inhabitants . It is situated in the Masovian Voivodship ; previously, it was in Skierniewice Voivodship 45 km West of Warsaw. It is the capital of Żyrardów County...

, in Łaskarzew, and across Kielce Voivodship.

In tiny villages where there was no permanent Nazi military presence, such as Dąbrowa Rzeczycka

Dabrowa Rzeczycka

Dąbrowa Rzeczycka is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Radomyśl nad Sanem, within Stalowa Wola County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in south-eastern Poland. It lies approximately east of Radomyśl nad Sanem, north of Stalowa Wola, and north of the regional capital...

, Kępa Rzeczycka

Kepa Rzeczycka

Kępa Rzeczycka is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Radomyśl nad Sanem, within Stalowa Wola County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in south-eastern Poland. It lies approximately south-east of Radomyśl nad Sanem, north of Stalowa Wola, and north of the regional capital...

and Wola Rzeczycka

Wola Rzeczycka

Wola Rzeczycka is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Radomyśl nad Sanem, within Stalowa Wola County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in south-eastern Poland. It lies approximately east of Radomyśl nad Sanem, north of Stalowa Wola, and north of the regional capital Rzeszów.-References:...

near Stalowa Wola

Stalowa Wola

Stalowa Wola is the largest city and capital of Stalowa Wola County with a population of 64,353 inhabitants, as of June 2008. It is located in southeastern Poland in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship...

, some Jews were able to openly participate in the lives of their communities. Olga Lilien, recalling her wartime experience in the 2000 book To Save a Life: Stories of Holocaust Rescue, was sheltered by a Polish family in a village near Tarnobrzeg

Tarnobrzeg

Tarnobrzeg is a city in south-eastern Poland, on the east bank of the river Vistula, with 49,419 inhabitants, as of December 31, 2009. Situated in the Subcarpathian Voivodeship since 1999, it had previously been the capital of Tarnobrzeg Voivodeship...

, where she survived the war despite the posting of a 200 deutsche mark reward by the Nazi occupiers for information on Jews in hiding. Chava Grinberg-Brown from Gmina Wiskitki

Gmina Wiskitki

Gmina Wiskitki is a rural gmina in Żyrardów County, Masovian Voivodeship, in east-central Poland. Its seat is the village of Wiskitki, which lies approximately north-west of Żyrardów and west of Warsaw....

recalled in a postwar interview that some farmers used the threat of violence against a fellow villager who intimated the desire to betray her safety. Polish-born Israeli writer and Holocaust survivor Natan Gross, in his 2001 book Who Are You, Mr. Grymek?, told of a village near Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

where a local Nazi collaborator was forced to flee when it became known he reported the location of a hidden Jew.

Nonetheless there were cases were people who saved the Jews were met with a different response after the war. Antonina Wyrzykowska, one of the Righteous, and her husband provided shelter for seven Jews who had survived the Jedwabne massacre, in which a minimum of 340 Polish Jews were burned alive in a barn by their Polish neighbors. Wyrzykowska successfully hid the seven in two bunkers in her home in nearby Yanczewka from July 1941 until liberation 28 months later. She was able to successfully evade searches by the Gestapo by keeping sheep on top of the hidden bunkers, and spreading gasoline to make it difficult for bloodhounds to pick up the scent of the hidden. After liberation, Wyrzykowska was taunted and beaten by her neighbors for having hidden Jews and was forced to leave her village.

Jews in Polish cities

Ghetto

A ghetto is a section of a city predominantly occupied by a group who live there, especially because of social, economic, or legal issues.The term was originally used in Venice to describe the area where Jews were compelled to live. The term now refers to an overcrowded urban area often associated...

s that were designed to imprison the local Jewish populations. The food rations allocated by the Germans to the ghettos condemned their inhabitants to starvation. Smuggling of food into the ghettos and smuggling of goods out of the ghettos, organized by Jews and Poles, was the only means of subsistence of the Jewish population in the ghettos. The price difference between the Aryan and Jewish sides was large, reaching as much as 100%, but the risk was also great. Hundreds of Polish and Jewish smugglers would come in and out the ghettos, usually at night or at dawn, through openings in the walls, underground tunnels and sewers or through the guardposts by paying bribes.

The Polish Underground urged the Poles to support smuggling. The punishment for smuggling was death, carried out on the spot. Among the Jewish smuggler victims were scores of Jewish children aged five or six, whom the German shot at the ghetto exits and near the walls. While communal rescue was impossible under these circumstances, many Polish Christians concealed their Jewish neighbors. For example, Zofia Baniecka

Zofia Baniecka

Zofia Baniecka was a Polish member of the Resistance during World War II. In addition to relaying guns and other materials to resistance fighters, Baniecka and her mother rescued over 50 Jews in their home between 1941 and 1944. Later, Baniecka was an activist with the Intervention Bureau of the...

and her mother rescued over 50 Jews in their home between 1941 and 1944. Paulsson, in his research on the Jews of Warsaw, documented that Warsaw's Polish residents managed to support and conceal the same percentage of Jews as did residents in other European cities under Nazi occupation.

Ten percent of Warsaw's Polish population was actively engaged in sheltering their Jewish neighbors. It is estimated that the number of Jews living in hiding on the Aryan side of the capital city in 1944 was at least 15,000 to 30,000 and relied on the network of 50,000–60,000 Poles who provided shelter, and about half as many assisting in other ways.

Organizations dedicated to saving the Jews

1946.jpg)

Zegota

"Żegota" , also known as the "Konrad Żegota Committee", was a codename for the Polish Council to Aid Jews , an underground organization of Polish resistance in German-occupied Poland from 1942 to 1945....

, the Council to Aid Jews, was the most prominent. It was unique not only in Poland, but in all of Nazi-occupied Europe, as there was no other organization dedicated solely to that goal. Żegota concentrated its efforts on saving Jewish children toward whom the Germans were especially cruel. Polish sociologist Tadeusz Piotrowski

Tadeusz Piotrowski (sociologist)

Tadeusz Piotrowski or Thaddeus Piotrowski is a Polish-American sociologist. He is a Professor of Sociology in the Social Science Division of the University of New Hampshire at Manchester in Manchester, New Hampshire, where he lives....

estimates that about half of the Jews who survived the war (more than 50,000) were aided by Żegota with various forms of assistance – financial, legalization, medical, child care, and help against blackmailers. In his 1977 study Joseph Kermish asserts that a number of Polish sources overestimated the levels of support Żegota provided to Jews, saving perhaps only a few thousands of Jews (although this lower figure only counts those saved in Warsaw rather than all of occupied Poland); nonetheless the study concurs that the activities of Żegota "constitute one of the most brilliant chapters in the efforts to extend relief to Jews.".

Perhaps the most famous member of Żegota was Irena Sendler

Irena Sendler

Irena Sendler was a Polish Catholic social worker who served in the Polish Underground and the Żegota resistance organization in German-occupied Warsaw during World War II...

, who managed to successfully smuggle 2,500 Jewish children out of the Warsaw Ghetto

Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest of all Jewish Ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II. It was established in the Polish capital between October and November 15, 1940, in the territory of General Government of the German-occupied Poland, with over 400,000 Jews from the vicinity...

. Besides Żegota, there were few smaller, less effective organizations, which on their actions agenda included help to the Jews. Some were associated with Zegota.

Jews and the Church

The Roman Catholic Church in Poland provided many persecuted Jews with food and shelter during the war, even though monasteries gave no immunity to Polish priests and monks against the death penalty. Nearly every Catholic institution in Poland looked after a few Jews, usually children with forged Christian birth certificates and an assumed or vague identity. In particular, convents of Catholic nuns in Poland (see Sister BertrandaAnna Borkowska (Sister Bertranda)

Anna Borkowska a.k.a. Sister Bertranda , a graduate of the University of Kraków, was a Polish nun who served as Mother Superior of a convent for an order of Dominican Sisters at a cloister in Kolonia Wileńska, near Wilno, Poland...

), played a major role in the effort to rescue and shelter Polish Jews, with the Franciscan Sisters credited with the largest number of Jewish children saved. Two thirds of all nunneries in Poland took part in the rescue, in all likelihood with the support and encouragement of the church hierarchy. These efforts were supported by local Polish bishops and the Vatican

Holy See

The Holy See is the episcopal jurisdiction of the Catholic Church in Rome, in which its Bishop is commonly known as the Pope. It is the preeminent episcopal see of the Catholic Church, forming the central government of the Church. As such, diplomatically, and in other spheres the Holy See acts and...

itself. The convent leaders never disclosed the exact number of children saved in their institutions, and for security reasons the rescued children were never registered. Jewish institutions have no statistics that could clarify the matter. Systematic recording of testimonies did not begin until the early 1970s. In the villages of Ożarów

Ozarów

Ożarów is a town in Poland, in Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship, in Powiat of Opatów . It has 4,906 inhabitants and its largest employer is a large cement factory nearby. The cement factory was privatized in 1995 and a controlling stake in the company was purchased by Irish company CRH plc from HCP...

, Ignaców, Szymanów

Gmina Lezajsk

Gmina Leżajsk is a rural gmina in Leżajsk County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in south-eastern Poland. Its seat is the town of Leżajsk, although the town is not part of the territory of the gmina....

, and Grodzisko

Grodzisko Dolne

Grodzisko Dolne is a village in Leżajsk County, Subcarpathian Voivodeship, in south-eastern Poland. It is the seat of the gmina called Gmina Grodzisko Dolne. It lies approximately south of Leżajsk and north-east of the regional capital Rzeszów.-References:...

near Leżajsk

Lezajsk

Leżajsk is a town in southeastern Poland with 14,127 inhabitants . It has been situated in the Subcarpathian Voivodship since 1999 and is the capital of Leżajsk County. Leżajsk is famed for its Bernadine basilica and monastery, built by the architect Antonio Pellacini...

, the Jewish children were cared for by Catholic convents and by the surrounding communities. In these villages, Christian parents did not remove their children from schools where Jewish children were in attendance.

Irena Sendler

Irena Sendler

Irena Sendler was a Polish Catholic social worker who served in the Polish Underground and the Żegota resistance organization in German-occupied Warsaw during World War II...

head of children's section Żegota

Zegota

"Żegota" , also known as the "Konrad Żegota Committee", was a codename for the Polish Council to Aid Jews , an underground organization of Polish resistance in German-occupied Poland from 1942 to 1945....

(the Council to Aid Jews) organisation cooperated very closely in saving Jewish children from the Warsaw Ghetto

Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest of all Jewish Ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II. It was established in the Polish capital between October and November 15, 1940, in the territory of General Government of the German-occupied Poland, with over 400,000 Jews from the vicinity...

with social worker and catholic nun

Nun

A nun is a woman who has taken vows committing her to live a spiritual life. She may be an ascetic who voluntarily chooses to leave mainstream society and live her life in prayer and contemplation in a monastery or convent...

, mother provincial of Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary

Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary

The Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary, , also known as Siostry Rodziny Maryi, RM, is a Polish female Catholic order. The congregation was established in St. Petersburg during the Partitions of Poland with the mission to help Polish children stricken by hunger in the Russian Empire, and to...

- Matylda Getter

Matylda Getter

Matylda Getter was a Polish catholic nun, mother provincial of CSFFM - Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary in Warsaw and social worker in pre war Poland...

. The children were placed with Polish families, the Warsaw orphanage of the Sisters of the Family of Mary, or Roman Catholic convents such as the Little Sister Servants of the Blessed Virgin Mary Conceived Immaculate at Turkowice and Chotomów. Sister Matylda Getter rescued between 250-550 Jewish children in different education and care facilities for children in Anin, Białołęka, Chotomów

Chotomów

Chotomów is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Jabłonna, within Legionowo County, Masovian Voivodeship, in east-central Poland. It lies approximately north-west of Jabłonna, north-west of Legionowo, and north of Warsaw....

, Międzylesie

Miedzylesie

Międzylesie is a town in Kłodzko County, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, in south-western Poland. It is the seat of the administrative district called Gmina Międzylesie, close to the Czech border. Prior to 1945 it was part of Germany....

, Płudy, Sejny

Sejny

Sejny is a town in north-eastern Poland, in Podlaskie Voivodeship, close to the border with Lithuania and Belarus. It is located in the eastern part of the Suwałki Lake Area , on the Marycha river, being a tributary of Czarna Hańcza...

, Vilnius

Vilnius

Vilnius is the capital of Lithuania, and its largest city, with a population of 560,190 as of 2010. It is the seat of the Vilnius city municipality and of the Vilnius district municipality. It is also the capital of Vilnius County...

and others.

Historians have determined that in some villages, Jewish families survived the Holocaust by living under assumed identities as Christians — with the knowledge of their neighbors, who did not betray their identities. This has been confirmed in the villages of Bielsko

Bielsko

Bielsko was until 1950 an independent town situated in Cieszyn Silesia, Poland. In 1951 it was joined with Biała Krakowska to form the new town of Bielsko-Biała. Bielsko constitutes the western part of that town....

(Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia. Since the 9th century, Upper Silesia has been part of Greater Moravia, the Duchy of Bohemia, the Piast Kingdom of Poland, again of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown and the Holy Roman Empire, as well as of...

), in Dziurków near Radom

Radom

Radom is a city in central Poland with 223,397 inhabitants . It is located on the Mleczna River in the Masovian Voivodeship , having previously been the capital of Radom Voivodeship ; 100 km south of Poland's capital, Warsaw.It is home to the biennial Radom Air Show, the largest and...

, in Olsztyn Village near Częstochowa

Czestochowa

Częstochowa is a city in south Poland on the Warta River with 240,027 inhabitants . It has been situated in the Silesian Voivodeship since 1999, and was previously the capital of Częstochowa Voivodeship...

, in Korzeniówka near Grójec

Grójec

Grójec is a town in Poland. Located in the Masovian Voivodeship, about 40 km south of Warsaw, it is the capital of Grójec County. It has about 14,875 inhabitants . Grójec surroundings are considered to be the biggest apple-growing area of Poland. It is said, that the region makes up also for...

, in Łaskarzew, Sobolew

Garwolin County

Garwolin County is a unit of territorial administration and local government in Masovian Voivodeship, east-central Poland. It came into being on January 1, 1999, as a result of the Polish local government reforms passed in 1998. Its administrative seat and largest town is Garwolin, which lies ...

, and Wilga

Garwolin County

Garwolin County is a unit of territorial administration and local government in Masovian Voivodeship, east-central Poland. It came into being on January 1, 1999, as a result of the Polish local government reforms passed in 1998. Its administrative seat and largest town is Garwolin, which lies ...

triangle, and in several villages near Łowicz.

Some officials in the senior Polish priesthood however, remained hostile toward the Jews – a theological attitude well-known from before the war. After the war, some convents were unwilling to return children to Jewish institutions that asked for them and refused to disclose the adoptive parents' identities, forcing government agencies and courts to intervene.

Jews and the Polish government

Lack of international effort to aid Jews resulted in political uproar on the part of the Polish government in exilePolish government in Exile

The Polish government-in-exile, formally known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in Exile , was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which...

residing in Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

. The government often publicly expressed outrage at German mass murders of Jews. In 1942, Directorate of Civil Resistance

Directorate of Civil Resistance

Directorate of Civil Resistance was one of the branches of the Polish Government Delegate’s Office during World War II. Its main tasks were to maintain the morale of the Polish society, encourage passive resistance, report German atrocities and cruelties to the Polish Government in Exile, and to...

, part of the Polish Underground State, issued a following declaration based on reports by Polish underground.

Western Allies

The Western Allies were a political and geographic grouping among the Allied Powers of the Second World War. It generally includes the United Kingdom and British Commonwealth, the United States, France and various other European and Latin American countries, but excludes China, the Soviet Union,...

about the Holocaust, although early reports were often met with disbelief even by Jewish leaders themselves; then, for much longer, by Western powers. Witold Pilecki

Witold Pilecki

Witold Pilecki was a soldier of the Second Polish Republic, the founder of the Secret Polish Army resistance group and a member of the Home Army...

was member of Polish Armia Krajowa

Armia Krajowa

The Armia Krajowa , or Home Army, was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II German-occupied Poland. It was formed in February 1942 from the Związek Walki Zbrojnej . Over the next two years, it absorbed most other Polish underground forces...

resistance, and the only person who volunteered to be imprisoned in Auschwitz. As agent of underground intelligence he begun sending numerous reports about camp and genocide to Polish resistance

Polish resistance movement in World War II

The Polish resistance movement in World War II, with the Home Army at its forefront, was the largest underground resistance in all of Nazi-occupied Europe, covering both German and Soviet zones of occupation. The Polish defence against the Nazi occupation was an important part of the European...

headquarters in Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

through the resistance network he organized in Auschwitz. In March 1941, Pilecki's reports were being forwarded via the Polish resistance to the British government in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

but the British authorities refused AK reports on atrocities as be a gross exaggerations and propaganda of Polish government.

Similarly, Jan Karski

Jan Karski

Jan Karski was a Polish World War II resistance movement fighter and later scholar at Georgetown University. In 1942 and 1943 Karski reported to the Polish government in exile and the Western Allies on the situation in German-occupied Poland, especially the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto, and...

, who had been serving as a courier between the Polish underground and the Polish government in exile, was smuggled into the Warsaw Ghetto

Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest of all Jewish Ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II. It was established in the Polish capital between October and November 15, 1940, in the territory of General Government of the German-occupied Poland, with over 400,000 Jews from the vicinity...

and reported to the Polish, British and American governments on the situation of Jews in Poland. In 1942 Karski reported to the Polish, British and U.S. governments on the situation in Poland, especially the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto and the Holocaust of the Jews. He met with Polish politicians in exile including the prime minister, as well as members of political parties such as the PPS, SN, SP

Stronnictwo Pracy

Stronnictwo Pracy was a Polish Christian democratic political party, active from 1937 in the Second Polish Republic and later part of the Polish government in exile. Its founder and main activist was Karol Popiel....

, SL

Stronnictwo Ludowe

The People's Party was a Polish political party, active from 1931 in the Second Polish Republic. An agrarian populist party, its power base was composed mostly from peasants....

, Jewish Bund

General Jewish Labour Bund in Poland

The General Jewish Labour Bund in Poland was a Jewish socialist party in Poland which promoted the political, cultural and social autonomy of Jewish workers, sought to combat antisemitism and was generally opposed to Zionism.-Creation of the Polish Bund:...

and Poalei Zion. He also spoke to Anthony Eden

Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, KG, MC, PC was a British Conservative politician, who was Prime Minister from 1955 to 1957...

, the British foreign secretary, and included a detailed statement on what he had seen in Warsaw and Bełżec. In 1943 in London he met the then much known journalist Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler

Arthur Koestler CBE was a Hungarian author and journalist. Koestler was born in Budapest and, apart from his early school years, was educated in Austria...

. He then traveled to the United States and reported to President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

.

In July 1943, Jan Karski again personally reported to Roosevelt about the plight of Polish Jews, but the president "interrupted and asked the Polish emissary about the situation of... horses" in Poland. He also met with many other government and civic leaders in the United States, including Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.-Early life:Frankfurter was born into a Jewish family on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, Austria, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe. He was the third of six children of Leopold and Emma Frankfurter...

, Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull was an American politician from the U.S. state of Tennessee. He is best known as the longest-serving Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt during much of World War II...

, William Joseph Donovan

William Joseph Donovan

William Joseph Donovan was a United States soldier, lawyer and intelligence officer, best remembered as the wartime head of the Office of Strategic Services...

, and Stephen Wise

Stephen Samuel Wise

Stephen Samuel Wise was an Austro-Hungarian-born American Reform rabbi and Zionist leader.-Early life:...

. Karski also presented his report to media, bishops of various denominations (including Cardinal Samuel Stritch), members of the Hollywood film industry and artists, but without success. Many of those he spoke to did not believe him and again supposed that his testimony was much exaggerated or was propaganda from the Polish government in exile

Polish government in Exile

The Polish government-in-exile, formally known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in Exile , was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which...

.

The supreme political body of the underground government within Poland was the Delegatura. There were no Jewish representatives in it. Delegatura financed and sponsored Żegota

Zegota

"Żegota" , also known as the "Konrad Żegota Committee", was a codename for the Polish Council to Aid Jews , an underground organization of Polish resistance in German-occupied Poland from 1942 to 1945....

, the organization for help to the Polish Jews – run jointly by Jews and non-Jews. Żegota was granted nearly 29 million zlotys (over $ 5 million dollars; or, 13.56 times as much in today's funds) by Delegatura since 1942 for the relief payments to thousands of extended Jewish families in Poland. The government in exile also provided special assistance – funds, arms and other supplies – to Jewish resistance organizations (like ŻOB

ZOB

ZOB can refer to:*Jewish Combat Organization*Cleveland Air Route Traffic Control Center*Berlin Zoologischer Garten railway station*Electronic Music Producer...

and ŻZW), particularly from 1942 onwards. The interim government transmitted messages from Jewish underground to the West and gave support to their requests for retaliation on German targets if the atrocities are not stopped – a request that was dismissed by the Allied governments. The Polish government also tried, without much success, to increase the chances of Polish refugees finding a safe haven in neutral countries and to prevent deportations of escaping Jews back to Nazi-occupied Poland.

Polish Delegate of the Government in Exile residing in Hungary, Henryk Slawik

Henryk Slawik

Henryk Sławik, born 16 July 1894 in Szeroka , was executed by Nazi Germans in Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp on 26 August 1944...

, helped rescue over 5,000 Hungarian and Polish Jews in Budapest

Budapest

Budapest is the capital of Hungary. As the largest city of Hungary, it is the country's principal political, cultural, commercial, industrial, and transportation centre. In 2011, Budapest had 1,733,685 inhabitants, down from its 1989 peak of 2,113,645 due to suburbanization. The Budapest Commuter...

, by giving them false Polish passports as non-Jews.

With two members on the National Council, Polish Jews were sufficiently represented in the government in exile. Also, in 1943 a Jewish affairs section of the Underground State was set up by the Government Delegation for Poland; it was headed by Witold Bieńkowski

Witold Bienkowski

Witold Bieńkowski, code-name Wencki , was a Polish politician, publicist and during World War II, leader ofthe Catholic underground group, “Front for a Reborn Poland” , member of the Provisional...

and Władysław Bartoszewski. Its purpose was to organize efforts concerning the Polish Jewish population, to coordinate with Zegota, and to prepare documentation about the fate of the Jews for the government in London. Regrettably, the great number of Polish Jews had been killed already even before the Government-in-exile fully realized the totality of the Final Solution. According to David Engel and Daniel Stola, the government-in-exile primarily concerned itself with the fate of Polish people in general, reestablishing independent Polish state and establishing itself as an equal partner amongst the Allied forces. On top of its relative weakness, the government in exile was subject to the scrutiny of the West, in particular, American and British Jews reluctant to criticize their own governments for inaction in regard to saving their fellow Jews.

The Polish government and its underground representatives at home issued declarations that people acting against the Jews (blackmailers and others) would be punished by death. General Władysław Sikorski, the Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, signed a following decree and called upon the Polish population to extend aid to the persecuted Jews:

However, according to Michael C. Steinlauf

Michael C. Steinlauf

Michael C. Steinlauf is an Associate Professor of History at Gratz College, Pennsylvania. Steinlauf teaches Jewish history and culture in Eastern Europe and Polish-Jewish relations. He is the author and editor focused on studies of Jewish popular culture in Poland. His work has been translated into...

, only on rare occasions did appeals to Poles to help Jews accompany these statements before the Warsaw Ghetto uprising

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the Jewish resistance that arose within the Warsaw Ghetto in German occupied Poland during World War II, and which opposed Nazi Germany's effort to transport the remaining ghetto population to Treblinka extermination camp....

in 1943. Steinlauf points out that in one speech made in London Sikorski was promising equal rights for Jews after the war, but the promise was omitted from the printed Polish version of the speech. According to David Engel

David Engel

David Engel is an American historian and Professor of Holocaust and Judaic Studies at New York University. Dr. Engel holds a Ph.D...

, the loyalty of Polish Jews to Poland and Polish interests was held in doubt by some members of the exiled government, leading to political tensions. Overall, as Stola notes, Polish government was just as unprepared to deal with the Holocaust as were the other Allied governments, and that the government's hesitancy in appeals to the general population to aid the Jews diminished only after reports of the Holocaust became more wide spread.

Szmul Zygielbojm

Szmul Zygielbojm

Szmul Zygielbojm was a Jewish-Polish socialist politician, leader of the Bund, and a member of the National Council of the Polish government in exile...

, a member of the National Council

National Council of Poland

National Council of Poland was a consulting and expert body of the Polish government in exile and Polish president. The first council was formed in December 1939 and was disbanded in July 1941 in protest to the signing of the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement. It was reactivated in February 1942, but...

of the Polish government in exile, committed suicide in May 1943, in London, in protest against the indifference of the Allied governments toward the destruction of the Jewish people, and the failure of the Polish government to rouse public opinion commensurate with the scale of the tragedy befalling Polish Jews.

Poland, with its unique underground state, was the only country in occupied Europe to have an extensive, underground justice system. These clandestine courts operated with attention to due process (obviously limited by circumstances) and as a result it could take months to get a death sentence passed, much as in regular judicial systems. However, Prekerowa notes that the death sentences only began to be issued in September 1943, which meant that blackmailers were able to operate undeterred for 3 years from the time of the sealing of the Jewish ghettos in Autumn 1940. Overall, it took the Polish underground until late 1942 to legislate and organize non-military courts which were authorized to pass death sentences for civilian crimes, such as non-treasonous collaboration, extortion and blackmail. According to Joseph Kermish, among the thousands of collaborators sentenced to death by the Special Courts

Special Courts

Special Courts were the underground courts organized by the Polish Government in Exile during World War II in occupied Poland. The courts determined punishments for the citizens of Poland who were subject to the Polish law before the war.-History:After the Polish Defense War of 1939...

and executed by the Polish resistance fighters who risked death carrying out these verdicts, very few were explicitly blackmailers or informers who had persecuted Jews. This, according to Kermish, led to increasing boldness of some of the blackmailers in their criminal activities. Marek Jan Chodakiewicz writes that a number of Polish Jews were executed for denouncing other Jews. He notes that since Nazi informers often denounced members of the underground as well as Jews in hiding, the charge of collaboration was a general one and sentences passed were for cumulative crimes.

The Home Army units under the command of officers from left-wing Sanacja

Sanacja

Sanation was a Polish political movement that came to power after Józef Piłsudski's May 1926 Coup d'État. Sanation took its name from his watchword—the moral "sanation" of the Polish body politic...

, the PPS

Polish Socialist Party

The Polish Socialist Party was one of the most important Polish left-wing political parties from its inception in 1892 until 1948...

as well as the centrist Democratic Party

Democratic Party (Poland)