S. A. Andrée's Arctic balloon expedition of 1897

Encyclopedia

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is, subject to the caveats explained below, defined as the point in the northern hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface...

in which all three expedition members perished. S. A. Andrée

Salomon August Andrée

Salomon August Andrée , during his lifetime most often known as S. A. Andrée, was a Swedish engineer, physicist, aeronaut and polar explorer who died while leading an attempt to reach the Geographic North Pole by hydrogen balloon...

(1854–97), the first Swedish

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

balloonist

Balloon (aircraft)

A balloon is a type of aircraft that remains aloft due to its buoyancy. A balloon travels by moving with the wind. It is distinct from an airship, which is a buoyant aircraft that can be propelled through the air in a controlled manner....

, proposed a voyage by hydrogen

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with atomic number 1. It is represented by the symbol H. With an average atomic weight of , hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant chemical element, constituting roughly 75% of the Universe's chemical elemental mass. Stars in the main sequence are mainly...

balloon

Gas balloon

A gas balloon is any balloon that stays aloft due to being filled with a gas less dense than air or lighter than air . A gas balloon may also be called a Charlière for its inventor, the Frenchman Jacques Charles. Today, familiar gas balloons include large blimps and small rubber party balloons...

from Svalbard

Svalbard

Svalbard is an archipelago in the Arctic, constituting the northernmost part of Norway. It is located north of mainland Europe, midway between mainland Norway and the North Pole. The group of islands range from 74° to 81° north latitude , and from 10° to 35° east longitude. Spitsbergen is the...

to either Russia or Canada, which was to pass, with luck, straight over the North Pole on the way. The scheme was received with patriotic enthusiasm in Sweden, a northern nation that had fallen behind in the race for the North Pole.

Andrée neglected many early signs of the dangers associated with his balloon plan. Being able to steer the balloon to some extent was essential for a safe journey, and there was plenty of evidence that the drag-rope steering technique he had invented was ineffective; yet he staked the fate of the expedition on drag ropes. Worse, the polar balloon Örnen (Eagle) was delivered directly to Svalbard from its manufacturer in Paris without being tested; when measurements showed it to be leaking more than expected, Andrée refused to acknowledge the alarming implications of this. Most modern students of the expedition see Andrée's optimism, faith in the power of technology, and disregard for the forces of nature as the main factors in the series of events that led to his death and the deaths of his two companions Nils Strindberg

Nils Strindberg

Nils Strindberg was a Swedish photographer who was one of the three members of S. A. Andrée's ill-fated Arctic balloon expedition of 1897. Before perishing on Kvitøya with Andrée and Knut Frænkel, Strindberg recorded on film their long doomed struggle on foot to reach populated areas...

(1872–97) and Knut Frænkel

Knut Frænkel

Knut Hjalmar Ferdinand Frænkel was a Swedish engineer and arctic explorer who perished in the Arctic balloon expedition of 1897 of S. A...

(1870–97).

After Andrée, Strindberg, and Frænkel lifted off from Svalbard in July 1897, the balloon lost hydrogen quickly and crashed on the pack ice

Sea ice

Sea ice is largely formed from seawater that freezes. Because the oceans consist of saltwater, this occurs below the freezing point of pure water, at about -1.8 °C ....

after only two days. The explorers were unhurt but faced a grueling trek back south across the drifting icescape. Inadequately clothed, equipped, and prepared, and shocked by the difficulty of the terrain, they did not make it to safety. As the Arctic

Arctic

The Arctic is a region located at the northern-most part of the Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean and parts of Canada, Russia, Greenland, the United States, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland. The Arctic region consists of a vast, ice-covered ocean, surrounded by treeless permafrost...

winter closed in on them in October, the group ended up exhausted on the deserted Kvitøya

Kvitøya

Kvitøya is an island in the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, with an area of . It is located at , making it the easternmost part of the Kingdom of Norway...

(White Island) in Svalbard and died there. For 33 years the fate of the Andrée expedition remained one of the unsolved riddles of the Arctic. The chance discovery in 1930 of the expedition's last camp created a media sensation in Sweden, where the dead men were mourned and idolized. Andrée's motives have later been re-evaluated, along with the role of the polar areas as the proving-ground of masculinity

Masculinity

Masculinity is possessing qualities or characteristics considered typical of or appropriate to a man. The term can be used to describe any human, animal or object that has the quality of being masculine...

and patriotism

Patriotism

Patriotism is a devotion to one's country, excluding differences caused by the dependencies of the term's meaning upon context, geography and philosophy...

. An early example is Per Olof Sundman

Per Olof Sundman

Per Olof Sundman was a Swedish writer and politician.Sundman was born in Vaxholm. After World War II, Sundman joined the Centre Party and was elected to the Riksdag....

's fictionalized bestseller novel of 1967, The Flight of the Eagle (later filmed as Flight of the Eagle

Flight of the Eagle

Flight of the Eagle is a 1982 Swedish biographical drama film directed by Jan Troell, based on Per Olof Sundman's novelization of the true story of S. A. Andrée's Arctic balloon expedition of 1897, an ill-fated effort to reach the North Pole in which all three expedition members perished. The film...

), which portrays Andrée as weak and cynical, at the mercy of his sponsors and the media. The verdict on Andrée by modern writers for virtually sacrificing the lives of his two younger companions varies in harshness, depending on whether he is seen as the manipulator or the victim of Swedish nationalist

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

fervor around the turn of the 20th century.

S. A. Andrée's scheme

Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration defines an era which extended from the end of the 19th century to the early 1920s. During this 25-year period the Antarctic continent became the focus of an international effort which resulted in intensive scientific and geographical exploration, sixteen...

. The inhospitable and dangerous Arctic and Antarctic

Antarctic

The Antarctic is the region around the Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica and the ice shelves, waters and island territories in the Southern Ocean situated south of the Antarctic Convergence...

regions spoke powerfully to the imagination of the age, not as lands with their own ecologies

Ecology

Ecology is the scientific study of the relations that living organisms have with respect to each other and their natural environment. Variables of interest to ecologists include the composition, distribution, amount , number, and changing states of organisms within and among ecosystems...

and cultures, but as challenges to technological ingenuity and manly daring.

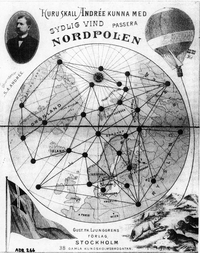

The Swede Salomon August Andrée

Salomon August Andrée

Salomon August Andrée , during his lifetime most often known as S. A. Andrée, was a Swedish engineer, physicist, aeronaut and polar explorer who died while leading an attempt to reach the Geographic North Pole by hydrogen balloon...

shared these enthusiasms, and proposed a plan for letting the wind propel a hydrogen balloon from Svalbard

Svalbard

Svalbard is an archipelago in the Arctic, constituting the northernmost part of Norway. It is located north of mainland Europe, midway between mainland Norway and the North Pole. The group of islands range from 74° to 81° north latitude , and from 10° to 35° east longitude. Spitsbergen is the...

across the Arctic Sea to the Bering Strait

Bering Strait

The Bering Strait , known to natives as Imakpik, is a sea strait between Cape Dezhnev, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia, the easternmost point of the Asian continent and Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, USA, the westernmost point of the North American continent, with latitude of about 65°40'N,...

, to fetch up in Alaska, Canada, or Russia, and passing near or even right over the North Pole on the way. Andrée was an engineer

Engineer

An engineer is a professional practitioner of engineering, concerned with applying scientific knowledge, mathematics and ingenuity to develop solutions for technical problems. Engineers design materials, structures, machines and systems while considering the limitations imposed by practicality,...

at the patent office

Patent office

A patent office is a governmental or intergovernmental organization which controls the issue of patents. In other words, "patent offices are government bodies that may grant a patent or reject the patent application based on whether or not the application fulfils the requirements for...

in Stockholm

Stockholm

Stockholm is the capital and the largest city of Sweden and constitutes the most populated urban area in Scandinavia. Stockholm is the most populous city in Sweden, with a population of 851,155 in the municipality , 1.37 million in the urban area , and around 2.1 million in the metropolitan area...

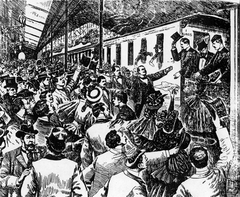

, with a passion for ballooning. He bought his own balloon, the Svea, in 1893 and made nine journeys with it, starting from Gothenburg

Gothenburg

Gothenburg is the second-largest city in Sweden and the fifth-largest in the Nordic countries. Situated on the west coast of Sweden, the city proper has a population of 519,399, with 549,839 in the urban area and total of 937,015 inhabitants in the metropolitan area...

or Stockholm and travelling a combined distance of 1500 kilometres (932.1 mi). In the prevailing westerly winds, the Svea flights had a strong tendency to carry him uncontrollably out to the Baltic Sea

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is a brackish mediterranean sea located in Northern Europe, from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from 20°E to 26°E longitude. It is bounded by the Scandinavian Peninsula, the mainland of Europe, and the Danish islands. It drains into the Kattegat by way of the Øresund, the Great Belt and...

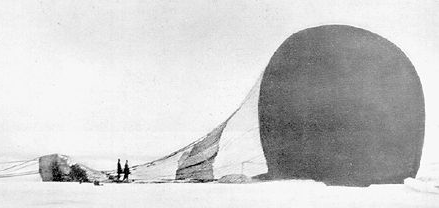

and drag his basket perilously along the surface of the water and/or slam it into one of the many rocky islets in the Stockholm archipelago

Stockholm archipelago

The Stockholm archipelago is the largest archipelago of Sweden, and one of the largest archipelagos of the Baltic Sea.-Geography:The archipelago extends from Stockholm roughly 60 kilometers to the east...

(see artist's impression, right). On one occasion he was blown clear across the Baltic to Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

. His longest trip was due east from Gothenburg, across the breadth of Sweden and out over the Baltic to Gotland

Gotland

Gotland is a county, province, municipality and diocese of Sweden; it is Sweden's largest island and the largest island in the Baltic Sea. At 3,140 square kilometers in area, the region makes up less than one percent of Sweden's total land area...

. Even though he actually saw a lighthouse

Lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses or, in older times, from a fire, and used as an aid to navigation for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways....

and heard breakers off Öland

Öland

' is the second largest Swedish island and the smallest of the traditional provinces of Sweden. Öland has an area of 1,342 km² and is located in the Baltic Sea just off the coast of Småland. The island has 25,000 inhabitants, but during Swedish Midsummer it is visited by up to 500,000 people...

, he remained convinced that he was travelling over land and merely seeing lakes.

During a couple of the Svea flights, Andrée tested and tried out the drag-rope steering technique that he had invented and wanted to use on his projected North Pole expedition. Drag ropes, which hang from the balloon basket and drag part of their length on the ground, are designed to counteract the tendency of lighter-than-air craft to travel at the same speed as the wind, a situation that makes steering by sail

Sail

A sail is any type of surface intended to move a vessel, vehicle or rotor by being placed in a wind—in essence a propulsion wing. Sails are used in sailing.-History of sails:...

s impossible. The friction of the ropes was intended to slow the balloon to the point where the sails would have an effect (beyond that of making the balloon rotate on its axis). Andrée claimed that, with the drag rope/sails steering, his Svea had essentially become a dirigible

Airship

An airship or dirigible is a type of aerostat or "lighter-than-air aircraft" that can be steered and propelled through the air using rudders and propellers or other thrust mechanisms...

, but this notion is rejected by modern balloonists. The Swedish Ballooning Association ascribes Andrée's conviction entirely to wishful thinking, capricious winds, and the fact that much of the time Andrée was inside clouds and had little idea where he was or which way he was moving. Moreover, his drag ropes would persistently snap, fall off, become entangled with each other, or get stuck to the ground, which could result in pulling the often low-flying balloon down into a dangerous bounce. No modern Andrée researcher has expressed any faith in drag ropes as a balloon steering technique.

Promotion and fundraising

Union between Sweden and Norway

The Union between Sweden and Norway , officially the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, consisted of present-day Sweden and Norway between 1814 and 1905, when they were united under one monarch in a personal union....

Norway

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

was a world power in Arctic exploration through such pioneers as Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen was a Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In his youth a champion skier and ice skater, he led the team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, and won international fame after reaching a...

. The Swedish political and scientific elite were eager to see Sweden take that lead among the Scandinavian countries which seemed her due, and Andrée, a persuasive speaker and fundraiser, found it easy to gain support for his ideas. At a lecture in 1895 to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences or Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. The Academy is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization which acts to promote the sciences, primarily the natural sciences and mathematics.The Academy was founded on 2...

, Andrée thrilled the audience of geographer

Geographer

A geographer is a scholar whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society.Although geographers are historically known as people who make maps, map making is actually the field of study of cartography, a subset of geography...

s and meteorologists. A polar exploration balloon, he explained, would need to fulfill four conditions:

- It must have enough lifting power to carry three people and all their scientific equipment, advanced cameraCameraA camera is a device that records and stores images. These images may be still photographs or moving images such as videos or movies. The term camera comes from the camera obscura , an early mechanism for projecting images...

s for aerial photographyAerial photographyAerial photography is the taking of photographs of the ground from an elevated position. The term usually refers to images in which the camera is not supported by a ground-based structure. Cameras may be hand held or mounted, and photographs may be taken by a photographer, triggered remotely or...

, provisions for four months, and ballast, altogether about 3000 kilogramKilogramThe kilogram or kilogramme , also known as the kilo, is the base unit of mass in the International System of Units and is defined as being equal to the mass of the International Prototype Kilogram , which is almost exactly equal to the mass of one liter of water...

s (about 3.5 short tonShort tonThe short ton is a unit of mass equal to . In the United States it is often called simply ton without distinguishing it from the metric ton or the long ton ; rather, the other two are specifically noted. There are, however, some U.S...

s). - It must retain the gas well enough to stay aloft for 30 days.

- The hydrogen gas must be manufactured, and the balloon filled, at the Arctic launch site.

- It must be at least somewhat steerable.

Andrée gave a glowingly optimistic account of the ease with which these requirements could be met. Larger balloons had been constructed in France, he claimed, and more airtight, too. Some French balloons had remained hydrogen-filled for over a year without appreciable loss of buoyancy

Buoyancy

In physics, buoyancy is a force exerted by a fluid that opposes an object's weight. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus a column of fluid, or an object submerged in the fluid, experiences greater pressure at the bottom of the...

. As for the hydrogen, filling the balloon at the launch site could easily be done with the help of mobile hydrogen manufacturing units; for the steering he referred to his own drag-rope experiments with the Svea, stating that a deviation of 27 degree

Degree (angle)

A degree , usually denoted by ° , is a measurement of plane angle, representing 1⁄360 of a full rotation; one degree is equivalent to π/180 radians...

s from the wind direction could be routinely achieved.

Andrée assured the audience that Arctic summer weather was uniquely suitable for ballooning. The midnight sun

Midnight sun

The midnight sun is a natural phenomenon occurring in summer months at latitudes north and nearby to the south of the Arctic Circle, and south and nearby to the north of the Antarctic Circle where the sun remains visible at the local midnight. Given fair weather, the sun is visible for a continuous...

would enable observations round the clock, halving the voyage time required, and do away with all need for anchoring at night, which might otherwise be a dangerous business. Neither would the balloon's buoyancy be adversely affected by the cold of night. The drag-rope steering technique was particularly well adapted for a region where the ground, consisting of ice, was "low in friction and free of vegetation". The minimal precipitation

Precipitation (meteorology)

In meteorology, precipitation In meteorology, precipitation In meteorology, precipitation (also known as one of the classes of hydrometeors, which are atmospheric water phenomena is any product of the condensation of atmospheric water vapor that falls under gravity. The main forms of precipitation...

in the area posed no threat of weighing down the balloon; if, against expectation, some rain or snow did fall on the balloon, Andrée argued, "precipitation at above-zero temperatures will melt, and precipitation at below-zero temperatures will blow off, for the balloon will be travelling more slowly than the wind." The audience was convinced by these arguments, so disconnected from the realities of the Arctic summer storms, fogs, high humidity

Humidity

Humidity is a term for the amount of water vapor in the air, and can refer to any one of several measurements of humidity. Formally, humid air is not "moist air" but a mixture of water vapor and other constituents of air, and humidity is defined in terms of the water content of this mixture,...

, and ever-present threat of ice formation. The academy approved Andrée's expense calculation of 130,800 kronor

Swedish krona

The krona has been the currency of Sweden since 1873. Both the ISO code "SEK" and currency sign "kr" are in common use; the former precedes or follows the value, the latter usually follows it, but especially in the past, it sometimes preceded the value...

in all, corresponding in today's money to just under a million U.S. dollars

United States dollar

The United States dollar , also referred to as the American dollar, is the official currency of the United States of America. It is divided into 100 smaller units called cents or pennies....

, of which the single largest sum, 36,000 kronor, was for the balloon itself. With this endorsement there was a rush to support his project, headed by King Oscar II

Oscar II of Sweden

Oscar II , baptised Oscar Fredrik was King of Sweden from 1872 until his death and King of Norway from 1872 until 1905. The third son of King Oscar I of Sweden and Josephine of Leuchtenberg, he was a descendant of Gustav I of Sweden through his mother.-Early life:At his birth in Stockholm, Oscar...

, who personally contributed 30,000 kronor, and Alfred Nobel

Alfred Nobel

Alfred Bernhard Nobel was a Swedish chemist, engineer, innovator, and armaments manufacturer. He is the inventor of dynamite. Nobel also owned Bofors, which he had redirected from its previous role as primarily an iron and steel producer to a major manufacturer of cannon and other armaments...

, the dynamite

Dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive material based on nitroglycerin, initially using diatomaceous earth , or another absorbent substance such as powdered shells, clay, sawdust, or wood pulp. Dynamites using organic materials such as sawdust are less stable and such use has been generally discontinued...

magnate and founder of the Nobel Prize

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes are annual international awards bestowed by Scandinavian committees in recognition of cultural and scientific advances. The will of the Swedish chemist Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, established the prizes in 1895...

.

Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne was a French author who pioneered the science fiction genre. He is best known for his novels Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea , A Journey to the Center of the Earth , and Around the World in Eighty Days...

. The press fanned the interest with a wide range of predictions, from certain death for the explorers to a safe and comfortable "guidance" of the balloon (upgraded by the reporter to an "airship

Airship

An airship or dirigible is a type of aerostat or "lighter-than-air aircraft" that can be steered and propelled through the air using rudders and propellers or other thrust mechanisms...

") to the North Pole in a manner planned by Parisian experts and Swedish scientists.

"In these days, the construction and guidance of airships have been improved greatly", wrote The Providence Journal

The Providence Journal

The Providence Journal, nicknamed the ProJo, is a daily newspaper serving the metropolitan area of Providence, Rhode Island and is the largest newspaper in Rhode Island. The newspaper, first published in 1829 and the oldest continuously-published daily newspaper in the United States, was purchased...

, "and it is supposed, both by the Parisian experts and by the Swedish scientists who have been assisting M. Andree, that the question of a sustained flight in this case will be very satisfactorily answered by the character of the balloon, by its careful guidance and, providing it gets into a Polar current of air, by the elements themselves." Faith in the experts and in science was common in the popular press, but with international attention came also for the first time informed criticism. Andrée being Sweden's first balloonist, nobody at home had the requisite knowledge to second-guess him about buoyancy or drag ropes; but in Germany and France there were long ballooning traditions and many far more experienced balloonists than Andrée, several of whom expressed scepticism of his methods and inventions. However, just as with the Svea mishaps, all objections failed to dampen Andrée's optimism. Eagerly followed by national and international media, he began negotiations with the well-known aeronaut and balloon builder Henri Lachambre

Henri Lachambre

Henri Lachambre was a French manufacturer of balloons. His factory was in the Paris suburb Vaugirard. He also participated in ballooning himself and attained a number of 500 ascents....

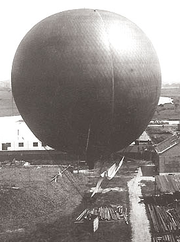

in Paris, world capital of ballooning, and ordered a varnished three-layer silk

Silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The best-known type of silk is obtained from the cocoons of the larvae of the mulberry silkworm Bombyx mori reared in captivity...

balloon, 20.5 meters (67 ft) in diameter

Diameter

In geometry, a diameter of a circle is any straight line segment that passes through the center of the circle and whose endpoints are on the circle. The diameters are the longest chords of the circle...

, from his workshop. The balloon, originally called Le Pôle Nord (French for "The North Pole"), was to be renamed Örnen (Swedish

Swedish language

Swedish is a North Germanic language, spoken by approximately 10 million people, predominantly in Sweden and parts of Finland, especially along its coast and on the Åland islands. It is largely mutually intelligible with Norwegian and Danish...

for "The Eagle").

The 1896 fiasco

Meteorology

Meteorology is the interdisciplinary scientific study of the atmosphere. Studies in the field stretch back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not occur until the 18th century. The 19th century saw breakthroughs occur after observing networks developed across several countries...

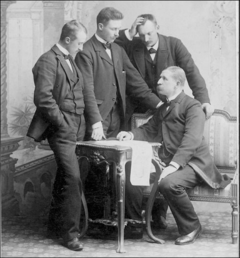

researcher, Nils Gustaf Ekholm

Nils Gustaf Ekholm

Nils Gustaf Ekholm was a Swedish meteorologist who led a Swedish geophysical expedition to Spitsbergen in 1882–1883.Ekholm was born in Smedjebacken in Dalarna, son of a pharmacist...

(1848–1923), formerly his boss during an 1882–83 geophysical

Geophysics

Geophysics is the physics of the Earth and its environment in space; also the study of the Earth using quantitative physical methods. The term geophysics sometimes refers only to the geological applications: Earth's shape; its gravitational and magnetic fields; its internal structure and...

expedition to Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen is the largest and only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in Norway. Constituting the western-most bulk of the archipelago, it borders the Arctic Ocean, the Norwegian Sea and the Greenland Sea...

, and Nils Strindberg

Nils Strindberg

Nils Strindberg was a Swedish photographer who was one of the three members of S. A. Andrée's ill-fated Arctic balloon expedition of 1897. Before perishing on Kvitøya with Andrée and Knut Frænkel, Strindberg recorded on film their long doomed struggle on foot to reach populated areas...

(1872–97), a brilliant student who was doing original research in physics and chemistry. The main scientific purpose of the expedition was to map the area by means of aerial photography

Aerial photography

Aerial photography is the taking of photographs of the ground from an elevated position. The term usually refers to images in which the camera is not supported by a ground-based structure. Cameras may be hand held or mounted, and photographs may be taken by a photographer, triggered remotely or...

, and Strindberg was both a devoted amateur photographer and a skilled constructor of advanced cameras. This was a team with many useful scientific and technical skills, but lacking any particular physical prowess or training for survival under extreme conditions. All three were indoor types, and only one of them, Strindberg, was young. Andrée expected a sedentary voyage in a balloon basket, and strength and survival skills

Survival skills

Survival skills are techniques a person may use in a dangerous situation to save themselves or others...

were far down on his list.

Modern writers all agree that Andrée's North Pole scheme was unrealistic. He relied on the winds blowing more or less in the direction he wanted to go, on being able to fine-tune his direction with the drag ropes, on the balloon being sealed tight enough to stay airborne for 30 days, and on no ice or snow sticking to the balloon to weigh it down. In the attempt of 1896, the wind immediately refuted his optimism by blowing steadily from the north, straight at the balloon hangar at Danskøya

Danskøya

Danskøya is an island in Norway's Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. It lies just off the northwest coast of Spitsbergen, the largest island in the archipelago, near to Magdalenefjorden. Just to the north lies Amsterdamøya. Like many of Svalbard's islands, Danskøya is uninhabited...

, until the expedition had to pack up, let the hydrogen out of the balloon, and go home. It is now known that northerly winds are to be expected at Danskøya; but in the late 19th century, information on Arctic airflow and precipitation existed only as contested academic hypotheses. Even Ekholm, an Arctic climate

Climate

Climate encompasses the statistics of temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure, wind, rainfall, atmospheric particle count and other meteorological elemental measurements in a given region over long periods...

researcher, had no objection to Andrée's theory of where the wind was likely to take them. The observational data simply did not exist.

On the other hand, Ekholm was critical of the balloon's ability to retain hydrogen, from his own measurements. Ekholm's buoyancy

Buoyancy

In physics, buoyancy is a force exerted by a fluid that opposes an object's weight. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus a column of fluid, or an object submerged in the fluid, experiences greater pressure at the bottom of the...

checks in the summer of 1896, during the process of producing the hydrogen and pumping it into the balloon, convinced him that the balloon leaked too much ever to reach the Pole, let alone go on to Russia or Canada. The worst leakage came from the approximately eight million tiny stitching holes along the seams, which no amount of glued-on strips of silk or applications of special secret-formula varnish

Varnish

Varnish is a transparent, hard, protective finish or film primarily used in wood finishing but also for other materials. Varnish is traditionally a combination of a drying oil, a resin, and a thinner or solvent. Varnish finishes are usually glossy but may be designed to produce satin or semi-gloss...

seemed to seal. The balloon was losing 68 kilogram

Kilogram

The kilogram or kilogramme , also known as the kilo, is the base unit of mass in the International System of Units and is defined as being equal to the mass of the International Prototype Kilogram , which is almost exactly equal to the mass of one liter of water...

s (150 lb

Pound (mass)

The pound or pound-mass is a unit of mass used in the Imperial, United States customary and other systems of measurement...

) of lift force a day, and, taking into account its heavy load, Ekholm estimated that it would be able to stay airborne for 17 days at most, not 30. When it was time to go home, he warned Andrée that he himself would not be on board for the next attempt, scheduled for summer 1897, unless a stronger, better-sealed balloon was bought.

Aftonbladet

Aftonbladet is a Swedish tabloid founded by Lars Johan Hierta in 1830 during the modernization of Sweden. It is one of the larger daily newspapers in the Nordic countries. Aftonbladet is owned by the Swedish Trade Union Confederation and Norwegian media group Schibsted, and its editorial page...

, right), and now all the expectations were coming to nothing with the long wait for southerly winds at Danskøya. Especially pointed was the contrast between Nansen's simultaneous return, covered in polar glory from his daring yet well-planned expedition on the ship Fram

Fram

Fram is a ship that was used in expeditions of the Arctic and Antarctic regions by the Norwegian explorers Fridtjof Nansen, Otto Sverdrup, Oscar Wisting, and Roald Amundsen between 1893 and 1912...

, and Andrée's failure even to launch his own much-hyped conveyance. Andrée, theorizes Sundman, could not at this point face letting the press report that besides not knowing which way the wind would blow he had also miscalculated in ordering the balloon and would like another one.

After the 1896 launch was called off, enthusiasm for joining the expedition for a second attempt in 1897 did not run quite so high. There were still candidates, however, and Andrée picked out the 27-year-old engineer Knut Frænkel

Knut Frænkel

Knut Hjalmar Ferdinand Frænkel was a Swedish engineer and arctic explorer who perished in the Arctic balloon expedition of 1897 of S. A...

to replace Ekholm. Frænkel was a civil engineer

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

from the north of Sweden, an athlete and fond of long mountain hikes. He was enrolled specifically to take over Ekholm's meteorological observations, and, despite lacking Ekholm's theoretical and scientific knowledge, handled this task efficiently. His meteorological journal has allowed the movements of the three men during their last few months to be reconstructed with considerable exactness.

Launch, flight, and landing

The balloon had two means of communication with the outside world, buoy

Buoy

A buoy is a floating device that can have many different purposes. It can be anchored or allowed to drift. The word, of Old French or Middle Dutch origin, is now most commonly in UK English, although some orthoepists have traditionally prescribed the pronunciation...

s and homing pigeon

Homing pigeon

The homing pigeon is a variety of domestic pigeon derived from the Rock Pigeon selectively bred to find its way home over extremely long distances. The wild rock pigeon has an innate homing ability, meaning that it will generally return to its own nest and its own mate...

s. The buoys, steel cylinders encased in cork

Cork (material)

Cork is an impermeable, buoyant material, a prime-subset of bark tissue that is harvested for commercial use primarily from Quercus suber , which is endemic to southwest Europe and northwest Africa...

, were intended to be dropped from the balloon into the water or onto the ice, to be carried to civilization by the currents. Only two buoy messages have ever been found. One was dispatched by Andrée on July 11, a few hours after takeoff, and reads "Our journey goes well so far. We sail at an altitude of about 250 m, at first N 10° east, but later N 45° east. […] Weather delightful. Spirits high." The second had been dropped an hour later and gave the height as 600 meters. Aftonbladet had supplied the pigeons, bred in northern Norway with the optimistic hope that they would manage to return there, and their message cylinders contained pre-printed instructions in Norwegian asking the finder to pass the messages on to the newspaper's address in Stockholm. Andrée released at least four pigeons, but only one was ever retrieved, by a Norwegian steamer where the pigeon had alighted and been promptly shot. Its message is dated July 13 and gives the travel direction at that point as East by 10° South, adding "All well on board". (Message reads: 'The Andree Polar Expedition to the "Aftonbladet", Stockholm. July 13 12.30pm, 82 deg. north latitude, 15 deg.5 min. east longitude. Good journey eastwards, 10 deg. south. All goes well on board. This is the third message sent by pigeon. Andree.') Lundström and others note that all three messages fail to mention the accident at takeoff, or the increasingly desperate situation, which was being detailed in Andrée's main diary. The balloon was out of equilibrium, sailing much too high and thereby losing hydrogen faster than even Nils Ekholm had feared, then repeatedly threatening to crash on the ice. It was weighed down by being rain-soaked ("dripping wet" writes Andrée in the diary), and all the sand and some of the payload were being thrown overboard to keep it airborne.

Free flight lasted for 10 hours and 29 minutes and was followed by another 41 hours of bumpy ride with frequent ground contact before the inevitable final crash. The Eagle thus traveled for 2 days and 3½ hours altogether, during which time according to Andrée nobody on board got any sleep. The definitive landing appears to have been gentle. Everybody was unhurt, including the homing pigeons in their wicker cages, and all the equipment was undamaged, even the delicate optical instruments and Strindberg's two cameras.

On foot on the ice

Cartography

Cartography is the study and practice of making maps. Combining science, aesthetics, and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality can be modeled in ways that communicate spatial information effectively.The fundamental problems of traditional cartography are to:*Set the map's...

camera, which had been brought to map the region from the air, became instead a means of recording daily life in the icescape and the constant danger and drudgery of the trek. Strindberg took about 200 photos with his seven-kilogram (15 lb) camera over the course of the three months they spent on the pack ice, one of the most famous being his picture of Andrée and Frænkel contemplating the fallen Eagle (see image above). Andrée and Frænkel also kept meticulous records of their experiences and geographical positions, Andrée in his "main diary", Frænkel in his meteorological journal. Strindberg's own stenographic diary was much more personal in content, and included his own general reflections on the expedition, as well as several messages to his fiancée Anna Charlier

Anna Charlier

Anna Albertina Constantia Charlier was a Swedish woman, today most commonly remembered as the fiancé of Nils Strindberg, participant in the Northpole-expedition of S. A. Andrée in 1897....

.

The Eagle had been stocked with safety equipment such as guns, snowshoe

Snowshoe

A snowshoe is footwear for walking over the snow. Snowshoes work by distributing the weight of the person over a larger area so that the person's foot does not sink completely into the snow, a quality called "flotation"....

s, sleds, skis, a tent, a small boat (in the form of a bundle of bent sticks, to be assembled and covered with balloon silk), most of it stored not in the basket but in the storage space arranged above the balloon ring. It had not been put together with great care, or with any thought of the indigenous peoples' techniques for adapting to the extreme environment. In this, Andrée contrasted not only with later but also with many earlier explorers. Sven Lundström points to the agonizing extra efforts that became necessary simply because the sleds Andrée had designed, of a rigid construction which owed nothing to Inuit

Inuit

The Inuit are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic regions of Canada , Denmark , Russia and the United States . Inuit means “the people” in the Inuktitut language...

sleds, were so impractical for the difficult terrain—"dreadful terrain", Andrée calls it—with its channels separating the ice floes, high ridges, and partially iced-over melt ponds. Their clothes did not include furs but consisted of woollen coats and trousers plus oilskin

Oilskin

Oilskin can mean:*A type of fabric: canvas with a skin of oil applied to it as waterproofing, often linseed oil. Old types of oilskin included:-**Heavy cotton cloth waterproofed with linseed oil.**Sailcloth waterproofed with a thin layer of tar....

s. The oilskins were worn, but the explorers still always seemed to be damp or wet from the half-frozen pools of water on the ice and the typically foggy, humid Arctic summer air, and always preoccupied with drying their clothes, mainly by wearing them. Danger was everywhere, as it would have meant certain death to lose the provisions lashed to one of the inconvenient sleds into one of the many channels that had to be laboriously crossed.

Franz Josef Land

Franz Josef Land, Franz Joseph Land, or Francis Joseph's Land is an archipelago located in the far north of Russia. It is found in the Arctic Ocean north of Novaya Zemlya and east of Svalbard, and is administered by Arkhangelsk Oblast. Franz Josef Land consists of 191 ice-covered islands with a...

and one at Seven Islands in Svalbard

Svalbard

Svalbard is an archipelago in the Arctic, constituting the northernmost part of Norway. It is located north of mainland Europe, midway between mainland Norway and the North Pole. The group of islands range from 74° to 81° north latitude , and from 10° to 35° east longitude. Spitsbergen is the...

(see map). Inferring from their faulty maps that the distances to each were about equal, they decided to try for the bigger depot at Cape Flora. Strindberg took more pictures during this week than he would at any later point, including 12 frames that make up a 360-degree panorama

Panorama

A panorama is any wide-angle view or representation of a physical space, whether in painting, drawing, photography, film/video, or a three-dimensional model....

of the crash site.

The balloon had carried a lot of food, of a kind more adapted for a balloon voyage than for travels on foot. Andrée had reasoned that they might as well throw excess food overboard as sand, if losing weight was necessary; and if it was not, the food would serve if wintering in the Arctic desert did after all become necessary. There was therefore less ballast and large amounts of heavy-type provisions, 767 kg (1690 lb) altogether, including 200 liter

Litre

pic|200px|right|thumb|One litre is equivalent to this cubeEach side is 10 cm1 litre water = 1 kilogram water The litre is a metric system unit of volume equal to 1 cubic decimetre , to 1,000 cubic centimetres , and to 1/1,000 cubic metre...

s of water and some crates of champagne, port

Port wine

Port wine is a Portuguese fortified wine produced exclusively in the Douro Valley in the northern provinces of Portugal. It is typically a sweet, red wine, often served as a dessert wine, and comes in dry, semi-dry, and white varieties...

, beer

Beer

Beer is the world's most widely consumed andprobably oldest alcoholic beverage; it is the third most popular drink overall, after water and tea. It is produced by the brewing and fermentation of sugars, mainly derived from malted cereal grains, most commonly malted barley and malted wheat...

, etc., donated by sponsors and manufacturers. There was also lemon juice

Lemon juice

The lemon fruit, from a citrus plant, provides a useful liquid when squeezed. Lemon juice, either in natural strength or concentrated, is sold as a bottled product, usually with the addition of preservatives and a small amount of lemon oil.-Uses:...

, though not as much of this precaution against scurvy

Scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a deficiency of vitamin C, which is required for the synthesis of collagen in humans. The chemical name for vitamin C, ascorbic acid, is derived from the Latin name of scurvy, scorbutus, which also provides the adjective scorbutic...

as other polar explorers usually thought necessary. Much of the food was in the form of cans of pemmican

Pemmican

Pemmican is a concentrated mixture of fat and protein used as a nutritious food. The word comes from the Cree word pimîhkân, which itself is derived from the word pimî, "fat, grease". It was invented by the native peoples of North America...

, meat, sausages, cheese, and condensed milk

Condensed milk

Condensed milk, also known as sweetened condensed milk, is cow's milk from which water has been removed and to which sugar has been added, yielding a very thick, sweet product which when canned can last for years without refrigeration if unopened. The two terms, condensed milk and sweetened...

. Some of it had in fact been thrown overboard. The three men took most of the rest with them on leaving the crash site, along with other necessities such as guns, tent, ammunition, and cooking utensils, making a load on each sled of more than 200 kg (440 lb). This was not realistic, as it broke the sleds and wore out the men, and after one week a big pile of food and non-essential equipment was left behind, bringing the loads down to 130 kg per sled. It became then more necessary than ever to hunt for food. Seal

Pinniped

Pinnipeds or fin-footed mammals are a widely distributed and diverse group of semiaquatic marine mammals comprising the families Odobenidae , Otariidae , and Phocidae .-Overview: Pinnipeds are typically sleek-bodied and barrel-shaped...

s, walrus

Walrus

The walrus is a large flippered marine mammal with a discontinuous circumpolar distribution in the Arctic Ocean and sub-Arctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. The walrus is the only living species in the Odobenidae family and Odobenus genus. It is subdivided into three subspecies: the Atlantic...

es, and especially polar bear

Polar Bear

The polar bear is a bear native largely within the Arctic Circle encompassing the Arctic Ocean, its surrounding seas and surrounding land masses. It is the world's largest land carnivore and also the largest bear, together with the omnivorous Kodiak Bear, which is approximately the same size...

s were shot and eaten throughout the march.

Starting out for Franz Josef Land to the south-east on July 22, the three soon found that their struggle across the ice with its two-story-high ridges was hardly bringing the goal any nearer: the drift of the ice was in the opposite direction, moving them backwards. On August 4 they decided, after a long discussion, to aim for Seven Islands in the southwest instead, hoping to reach the depot there after a six- to seven-week march, with the help of the current. The terrain in that direction was mostly extremely difficult, sometimes necessitating a crawl on all fours, but there was occasional relief in the form of open water—the little boat (not designed by Andrée) was apparently a functional and safe conveyance—and smooth, flat ice floes. "Paradise!" wrote Andrée. "Large even ice floes with pools of sweet drinking water and here and there a tender-fleshed young polar bear!" They made fair apparent headway, but the wind turned almost as soon as they did and they were again being moved backwards, away from Seven Islands. The wind varied between southwest and northwest over the coming weeks; they tried in vain to overcome this by turning more and more westward, but it was becoming clear that Seven Islands was out of their reach.

On September 12, the explorers resigned themselves to wintering on the ice and camped on a large floe, letting the ice take them where it would, "which", writes Kjellström, "it had really been doing all along" (p. 47). Drifting rapidly due south towards Kvitøya, they hurriedly built a winter "home" on the floe against the increasing cold, with walls made of water-reinforced snow to Strindberg's design (see plan, below, left). Observing the rapidity of their drift, Andrée recorded his hopes that they might get far enough south to feed themselves entirely from the sea. However, the floe began to break up directly under the hut on October 2 from the stresses of pressing against Kvitøya, and they were forced to bring their stores on to the island itself, which took a couple of days. "Morale remains good", reports Andrée at the very end of the coherent part of his diary, which ends: "With such comrades as these, one ought to be able to manage under practically any circumstances whatsoever." It is inferred from the incoherent and badly damaged last pages of Andrée's diary that the three men were all dead within a few days of moving onto the island.

Speculation and recovery

Psychic

A psychic is a person who professes an ability to perceive information hidden from the normal senses through extrasensory perception , or is said by others to have such abilities. It is also used to describe theatrical performers who use techniques such as prestidigitation, cold reading, and hot...

s, all of which would typically locate the stranded balloon far from Danskøya and Svalbard. Lundström points out (p. 134) that some of the international and national reports take on the features of urban legend

Urban legend

An urban legend, urban myth, urban tale, or contemporary legend, is a form of modern folklore consisting of stories that may or may not have been believed by their tellers to be true...

s and reflect a prevailing disrespect for the indigenous peoples of the Arctic, who frequently appear in the newspapers as uncomprehending savages and kill the three men or show a deadly indifference to their plight. These speculations were refuted in 1930, upon the discovery of the expedition's final resting place on Kvitøya by the crews of two ships, the Bratvaag and the Isbjørn.

The Norwegian Bratvaag Expedition

Bratvaag Expedition

The Bratvaag Expedition was a Norwegian expedition in 1930 led by Dr. Gunnar Horn, whose official tasks were hunting seals and to study glaciers and seas in the Svalbard Arctic region. The name of the expedition was taken from its ship, M/S Bratvaag of Ålesund, in which captain Peder Eliassen had...

, studying the glaciers and seas of the Svalbard archipelago

Archipelago

An archipelago , sometimes called an island group, is a chain or cluster of islands. The word archipelago is derived from the Greek ἄρχι- – arkhi- and πέλαγος – pélagos through the Italian arcipelago...

from the Norwegian sealing

Seal hunting

Seal hunting, or sealing, is the personal or commercial hunting of seals. The hunt is currently practiced in five countries: Canada, where most of the world's seal hunting takes place, Namibia, the Danish region of Greenland, Norway and Russia...

vessel Bratvaag of Ålesund

Ålesund

is a town and municipality in Møre og Romsdal county, Norway. It is part of the traditional district of Sunnmøre, and the center of the Ålesund Region. It is a sea port, and is noted for its unique concentration of Art Nouveau architecture....

, found the remains of the Andrée expedition on August 5, 1930. Kvitøya was usually inaccessible to the sealing or whaling ships of the time, as it is typically surrounded by a wide belt of thick polar ice and often hidden by thick ice fogs. However, summer in 1930 had been particularly warm, and the surrounding sea was practically free of ice. As Kvitøya was known to be a prime hunting ground for walrus

Walrus

The walrus is a large flippered marine mammal with a discontinuous circumpolar distribution in the Arctic Ocean and sub-Arctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. The walrus is the only living species in the Odobenidae family and Odobenus genus. It is subdivided into three subspecies: the Atlantic...

and the fogs over the island on that day were comparatively thin, some of the crew of the Bratvaag took this rare opportunity to land on what they called the "inaccessible island". Two of the sealers in search of water, Olav Salen and Karl Tusvick, discovered Andrée's boat near a small stream, frozen under a mound of snow and full of equipment, including a boathook engraved with the words "Andrée's Polar Expedition, 1896". Presented with this hook, the Bratvaags captain, Peder Eliassen, had the crew search the site together with the expedition members. Among other finds, a journal and two skeletons were uncovered, identified as Andrée's and Strindberg's remains by monogram

Monogram

A monogram is a motif made by overlapping or combining two or more letters or other graphemes to form one symbol. Monograms are often made by combining the initials of an individual or a company, used as recognizable symbols or logos. A series of uncombined initials is properly referred to as a...

s found on their clothing.

The Bratvaag left the island to continue its scheduled hunting and observations, with the intent of coming back later to see if the ice had melted further and uncovered more items. Further discoveries were made by the M/K Isbjørn of Tromsø

Tromsø

Tromsø is a city and municipality in Troms county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Tromsø.Tromsø city is the ninth largest urban area in Norway by population, and the seventh largest city in Norway by population...

, Norway

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

, a sealing sloop

Sloop

A sloop is a sail boat with a fore-and-aft rig and a single mast farther forward than the mast of a cutter....

chartered by news reporters to waylay the Bratvaag. Unsuccessful in this, the reporters and the Isbjørn crew made instead for Kvitøya, landing on the island on September 5 in fine weather and finding even less ice than the Bratvaag had. After photographing the area, they searched for and found the third body, that of Frænkel, and further artifacts, including a tin box containing Strindberg's photographic film and Strindberg's logbook and maps. The crews of both ships turned over their finds to a scientific commission of the Swedish and Norwegian governments in Tromsø

Tromsø

Tromsø is a city and municipality in Troms county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Tromsø.Tromsø city is the ninth largest urban area in Norway by population, and the seventh largest city in Norway by population...

on September 2 and 16, respectively. The bodies of the three explorers were transported to Stockholm, arriving on October 5.

Cause of deaths

Diarrhea

Diarrhea , also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having three or more loose or liquid bowel movements per day. It is a common cause of death in developing countries and the second most common cause of infant deaths worldwide. The loss of fluids through diarrhea can cause dehydration and...

, and were always tired, cold, and wet. When they moved on to Kvitøya from the ice, they left much of their valuable equipment and stores outside the tent, and even down by the water's edge, as if they were too exhausted, indifferent, or ill to carry it further. Strindberg, the youngest, died first and was "buried" (wedged into a cliff aperture) by the others. However, the interpretation of these observations is contested.

The best-known and most widely credited suggestion is that made by Ernst Tryde, a medical practitioner, in his book De döda på Vitön ("The Dead on Kvitøya") in 1952: that the men succumbed to trichinosis

Trichinosis

Trichinosis, also called trichinellosis, or trichiniasis, is a parasitic disease caused by eating raw or undercooked pork or wild game infected with the larvae of a species of roundworm Trichinella spiralis, commonly called the trichina worm. There are eight Trichinella species; five are...

that they contracted from eating undercooked polar bear meat. Larva

Larva

A larva is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle...

e of Trichinella spiralis

Trichinella spiralis

Trichinella spiralis is a nematode parasite, occurring in rats, pigs, bears and humans, and is responsible for the disease trichinosis. It is sometimes referred to as the "pork worm" due to it being found commonly in undercooked pork products...

were found in parts of a polar bear carcass at the site. Lundström and Sundman both favor this explanation, while critics point out that the diarrhea which is Tryde's main symptomatic evidence hardly needs an explanation beyond the general poor diet and physical misery, whereas some more specific symptoms of trichinosis are missing. Also, Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen was a Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In his youth a champion skier and ice skater, he led the team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, and won international fame after reaching a...

and his companion Hjalmar Johansen

Hjalmar Johansen

Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen was a polar explorer from Norway. He shipped out with Fridtjof Nansen's Fram expedition in 1893–1896, and accompanied Nansen to notch a new Farthest North record near the North Pole on what was then the frozen Arctic Ocean...

had lived largely on polar bear meat in exactly the same area for 15 months without any ill effects. Other suggestions have included vitamin A poisoning

Hypervitaminosis A

Hypervitaminosis A refers to the effects of excessive vitamin A intake.-Presentation:Effects include* Birth defects* Liver problems* Reduced bone mineral density that may result in osteoporosis* Coarse bone growths...

from eating polar bear liver; however, the diary shows Andrée to have been aware of this danger. Carbon monoxide poisoning

Carbon monoxide poisoning

Carbon monoxide poisoning occurs after enough inhalation of carbon monoxide . Carbon monoxide is a toxic gas, but, being colorless, odorless, tasteless, and initially non-irritating, it is very difficult for people to detect...

is a theory that has found a few adherents, such as the explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Vilhjalmur Stefansson was a Canadian Arctic explorer and ethnologist.-Early life:Stefansson, born William Stephenson, was born at Gimli, Manitoba, Canada, in 1879. His parents had emigrated from Iceland to Manitoba two years earlier...

. The chief objection is that their primus stove

Primus stove

The Primus stove, the first pressurized-burner kerosene stove, was developed in 1892 by Frans Wilhelm Lindqvist, a factory mechanic in Stockholm, Sweden. The stove was based on the design of the hand-held blowtorch; Lindqvist’s patent covered the burner, which was turned upward on the stove...

had kerosene still in the tank when found. Stefansson argues that they were using a malfunctioning stove, something he has experienced in his own expeditions. Lead poisoning

Lead poisoning

Lead poisoning is a medical condition caused by increased levels of the heavy metal lead in the body. Lead interferes with a variety of body processes and is toxic to many organs and tissues including the heart, bones, intestines, kidneys, and reproductive and nervous systems...

from the cans in which their food was stored is an alternative suggestion, as are scurvy

Scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a deficiency of vitamin C, which is required for the synthesis of collagen in humans. The chemical name for vitamin C, ascorbic acid, is derived from the Latin name of scurvy, scorbutus, which also provides the adjective scorbutic...

, botulism

Botulism

Botulism also known as botulinus intoxication is a rare but serious paralytic illness caused by botulinum toxin which is metabolic waste produced under anaerobic conditions by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, and affecting a wide range of mammals, birds and fish...

, suicide (they had plenty of opium), and polar bear attack. A combination favoured by Kjellström is that of cold and hypothermia

Hypothermia

Hypothermia is a condition in which core temperature drops below the required temperature for normal metabolism and body functions which is defined as . Body temperature is usually maintained near a constant level of through biologic homeostasis or thermoregulation...

as the Arctic winter closed in, with dehydration

Dehydration

In physiology and medicine, dehydration is defined as the excessive loss of body fluid. It is literally the removal of water from an object; however, in physiological terms, it entails a deficiency of fluid within an organism...

and general exhaustion, apathy, and disappointment. Kjellström argues that Tryde never takes the nature of their daily life into account, and especially the crowning blow of the ice breaking up under their promisingly mobile home, with the enforced move onto a glacier

Glacier

A glacier is a large persistent body of ice that forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. At least 0.1 km² in area and 50 m thick, but often much larger, a glacier slowly deforms and flows due to stresses induced by its weight...

island. "Posterity has expressed surprise that they died on Kvitøya, surrounded by food," writes Kjellström. "The surprise is rather that they found the strength to live so long" (p. 54).

In 2010, the theory that larva

Larva

A larva is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle...

e of Trichinella spiralis

Trichinella spiralis

Trichinella spiralis is a nematode parasite, occurring in rats, pigs, bears and humans, and is responsible for the disease trichinosis. It is sometimes referred to as the "pork worm" due to it being found commonly in undercooked pork products...

killed the expedition was rejected by researcher Bea Uusma Schyffert at Karolinska institutet, Sweden. Her conclusion after examining the clothes is that at least Strindberg was killed by polar bears.

Legacy

Engineer

An engineer is a professional practitioner of engineering, concerned with applying scientific knowledge, mathematics and ingenuity to develop solutions for technical problems. Engineers design materials, structures, machines and systems while considering the limitations imposed by practicality,...

"—"Ingenjör Andrée"—was generally and reverentially used in speaking of him, and expressed high esteem for the late 19th-century ideal of the engineer as a representative of social improvement through technological progress. The three explorers were fêted when they departed and mourned by the nation when they disappeared. When they were found, they were celebrated for the heroism of their doomed two-month struggle to reach populated areas and were seen as having selflessly perished for the ideals of science and progress. The home-bringing of their mortal remains to Stockholm on October 5, 1930, writes Swedish historian of ideas Sverker Sörlin, "must be one of the most solemn and grandiose manifestations of national mourning that has ever occurred in Sweden. One of the rare comparable events is the national mourning that followed the Estonia

M/S Estonia

MS Estonia, previously MS Viking Sally , MS Silja Star , and MS Wasa King , was a cruise ferry built in 1979/80 at the German shipyard Meyer Werft in Papenburg. The ship sank in the Baltic Sea in one of the worst maritime disasters of the 20th century...

disaster in the Baltic Sea in September 1994" (p. 100).

More recently, Andrée's heroic motives have been questioned, beginning with Per Olof Sundman

Per Olof Sundman

Per Olof Sundman was a Swedish writer and politician.Sundman was born in Vaxholm. After World War II, Sundman joined the Centre Party and was elected to the Riksdag....

's bestselling semi-documentary novel of 1967, The Flight of the Eagle, where Andrée is portrayed as the victim of the demands of the media and the Swedish scientific and political establishment, and as ultimately motivated by fear rather than courage. Sundman's interpretation of the personalities involved, the blind spots of the Swedish national culture, and the role of the press carries over into the Oscar-nominated film by Jan Troell, Flight of the Eagle

Flight of the Eagle

Flight of the Eagle is a 1982 Swedish biographical drama film directed by Jan Troell, based on Per Olof Sundman's novelization of the true story of S. A. Andrée's Arctic balloon expedition of 1897, an ill-fated effort to reach the North Pole in which all three expedition members perished. The film...

(1982), which is based on Sundman's novel.

Appreciation of Nils Strindberg's role seems to be growing, both for the fortitude with which the untrained and unprepared student kept photographing at all in what must have been a more or less permanent state of near-collapse from exhaustion and exposure, and for the artistic quality of the result. Out of the 240 exposed frames that were found on Kvitøya in waterlogged containers, 93 were saved by John Hertzberg at Strindberg's own workplace, the Royal Institute of Technology

Royal Institute of Technology

The Royal Institute of Technology is a university in Stockholm, Sweden. KTH was founded in 1827 as Sweden's first polytechnic and is one of Scandinavia's largest institutions of higher education in technology. KTH accounts for one-third of Sweden’s technical research and engineering education...

in Stockholm. In his article "Recovering the visual history of the Andrée expedition" (2004), Tyrone Martinsson has lamented the traditional focus by previous researchers on the written records—the diaries—as primary sources of information, and made a renewed claim for the historical significance of the photographs.

In 1983, American composer Dominick Argento

Dominick Argento

Dominick Argento is an American composer, best known as a leading composer of lyric opera and choral music...

created a song cycle

Song cycle

A song cycle is a group of songs designed to be performed in a sequence as a single entity. As a rule, all of the songs are by the same composer and often use words from the same poet or lyricist. Unification can be achieved by a narrative or a persona common to the songs, or even, as in Schumann's...

for baritone and piano entitled "The Andrée Expedition". This cycle sets to music texts from the diaries and letters. Swedish composer Klas Torstensson's opera "Expeditionen" (1994–99) is based on Andrée's story.

The story is included in The Ghost Disease and Twelve Other Stories of Detective Work in the Medical Field, by Michael Howell and Peter Ford (Penguin, 1986), which was dramatised for BBC Radio 4 by Michael Butt as "The Stranded Eagle" as part of the "Medical Detectives" series. The radio play aired 1 April 1998 and starred John Woodvine (Knut Stubbendorf), Clive Merrison (Ernst Tryde),

Ken Stott (S.A. Andrée), Jack Klaff (Knut Fraenkel) and Scott Handy (Nils Strindberg). The play has subsequently been broadcast on the digital channel, BBC 7.

Some of the items from the expedition, including the balloon-silk boat, and the tent, are on display at the Andréeexpeditionen Polar Centre at Grenna Museum, Sweden.

Further reading

- Pavlopoulos, George (2007). A novel in Greek about the echo of that expedition today, in Western societies.

- Sollinger, Guenther (2005), S.A. Andree: The Beginning of Polar Aviation 1895–1897. Moscow. Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Sollinger, Guenther (2005). S.A. Andree and Aeronautics: An annotated bibliography. Moscow. Russian Academy of Sciences.

External links

- Andrzej M. Kobos "Orłem" do bieguna, high-quality photos from the expedition.

- The Balloonist by MacDonald HarrisDonald HeineyDonald Heiney was a sailor and academic as well as a prolific and inventive writer using the pseudonym of MacDonald Harris for fiction.Heiney was born in South Pasadena, California, and grew up in South Pasadena and San Gabriel. He served in the Merchant Marine and the Navy during World War II...

, New York, Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 1976, is a fictional account of a polar expedition that bears a striking resemblance to, and was presumably inspired by, S. A. Andrée's expedition. ISBN 0-374-10874-9 ISBN 0-380-01739-3. - "Why Go To The Arctic", January 1931, Popular Mechanics drawing of ill fated Andree balloon flight top page 26