Scotland in the High Middle Ages

Encyclopedia

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

in the era between the death of Domnall II

Donald II of Scotland

Domnall mac Causantín , anglicised as Donald II was King of the Picts or King of Scotland in the late 9th century. He was the son of Constantine I...

in 900 AD and the death of king Alexander III

Alexander III of Scotland

Alexander III was King of Scots from 1249 to his death.-Life:...

in 1286. Alexander's death was an indirect cause of the Scottish Wars of Independence.

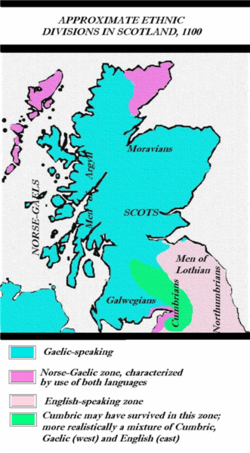

In the tenth and eleventh centuries, northern Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

was increasingly dominated by Gaelic

Gaels

The Gaels or Goidels are speakers of one of the Goidelic Celtic languages: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx. Goidelic speech originated in Ireland and subsequently spread to western and northern Scotland and the Isle of Man....

culture, and by a Gaelic regal lordship known in Gaelic

Goidelic languages

The Goidelic languages or Gaelic languages are one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic languages, the other consisting of the Brythonic languages. Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum stretching from the south of Ireland through the Isle of Man to the north of Scotland...

as "Alba

Alba

Alba is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is cognate to Alba in Irish and Nalbin in Manx, the two other Goidelic Insular Celtic languages, as well as similar words in the Brythonic Insular Celtic languages of Cornish and Welsh also meaning Scotland.- Etymology :The term first appears in...

", in Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

as either "Albania" or "Scotia

Scotia

Scotia was originally a Roman name for Ireland, inhabited by the people they called Scoti or Scotii. Use of the name shifted in the Middle Ages to designate the part of the island of Great Britain lying north of the Firth of Forth, the Kingdom of Alba...

", and in English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

as "Scotland". From a base in eastern Scotland north of the River Forth

River Forth

The River Forth , long, is the major river draining the eastern part of the central belt of Scotland.The Forth rises in Loch Ard in the Trossachs, a mountainous area some west of Stirling...

, the kingdom acquired control of the lands lying to the south. It had a flourishing culture, comprising part of the larger Gaelic-speaking world.

After the twelfth-century reign of King David I, the Scottish monarchs

Scottish Monarchs

The Scottish Monarchs were a motorcycle speedway team based in Glasgow, Scotland.At the end of the 1995 season, the Glasgow Tigers closed due a lack of finance and the Edinburgh Monarchs lost their home track, Powderhall Stadium, to redevelopment, leading to the Monarchs racing at Shawfield Stadium...

are better described as Scoto-Norman

Scoto-Norman

The term Scoto-Norman is used to described people, families, institutions and archaeological artifacts that are partly Scottish and partly Norman...

than Gaelic, preferring French culture to native Scottish culture. They fostered and attached themselves to a kind of Scottish "Norman Conquest". The consequence was the spread of French institutions and social values. Moreover, the first towns, called burghs, appeared in the same era, and as these burghs spread, so did the Middle English language. To a certain degree these developments were offset by the acquisition of the Norse-Gaelic

Norse-Gaels

The Norse–Gaels were a people who dominated much of the Irish Sea region, including the Isle of Man, and western Scotland for a part of the Middle Ages; they were of Gaelic and Scandinavian origin and as a whole exhibited a great deal of Gaelic and Norse cultural syncretism...

west, and the Gaelicization

Gaelicization

Gaelicization or Gaelicisation is the act or process of making something Gaelic, or gaining characteristics of the Gaels. The Gaels are an ethno-linguistic group who are traditionally viewed as having spread from Ireland to Scotland and the Isle of Man."Gaelic" as a linguistic term, refers to the...

of many of the noble families of French

French people

The French are a nation that share a common French culture and speak the French language as a mother tongue. Historically, the French population are descended from peoples of Celtic, Latin and Germanic origin, and are today a mixture of several ethnic groups...

and Anglo-French

Normans

The Normans were the people who gave their name to Normandy, a region in northern France. They were descended from Norse Viking conquerors of the territory and the native population of Frankish and Gallo-Roman stock...

origin. By the end of this period, Scotland experienced a "Gaelic revival" which created an integrated Scottish national identity

Scottish national identity

Scottish national identity is a term referring to the sense of national identity and common culture of Scottish people and is shared by a considerable majority of the people of Scotland....

. Although there remained a great deal of continuity with the past, by 1286 these economic, institutional, cultural, religious and legal developments had brought Scotland closer to its neighbours in England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

and the Continent

Continental Europe

Continental Europe, also referred to as mainland Europe or simply the Continent, is the continent of Europe, explicitly excluding European islands....

. By 1286 the Kingdom of Scotland

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland was a Sovereign state in North-West Europe that existed from 843 until 1707. It occupied the northern third of the island of Great Britain and shared a land border to the south with the Kingdom of England...

had political boundaries that closely resembled those of modern Scotland.

Historiography

Scotland in the High Middle Ages is a relatively well-studied topic with many publications from Scottish medievalists. Based on their main focus, researchers can generally be grouped into two categories: Celticists and Normanists. The former, such as David DumvilleDavid Dumville

Professor David Norman Dumville is a British medievalist and Celtic scholar. He was educated at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, Ludwig-Maximilian Universität, Munich, and received his PhD. at the University of Edinburgh in 1976. In 1974, he married Sally Lois Hannay, with whom he had one son...

, Thomas Owen Clancy

Thomas Owen Clancy

Professor Thomas Owen Clancy is an American academic and historian who specializes in the literature of the Celtic Dark Ages, especially that of Scotland. He did his undergraduate work at New York University, and his Ph.D at the University of Edinburgh. He is currently at the University of Glasgow,...

and Dauvit Broun

Dauvit Broun

Dauvit Broun is a Scottish historian, Professor of Scottish History at the University of Glasgow. A specialist in medieval Scottish and Celtic studies, he concentrates primarily on early medieval Scotland, and has written abundantly on the topic of early Scottish king-lists, as well as on...

, are interested in the native cultures of the country, and often have linguistic training in the Celtic languages

Celtic languages

The Celtic languages are descended from Proto-Celtic, or "Common Celtic"; a branch of the greater Indo-European language family...

. Normanists are concerned with the French and Anglo-French cultures as they were introduced to Scotland after the eleventh century. The most prominent of such scholars is G.W.S. Barrow, who has devoted his life to studying feudalism

Feudalism

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.Although derived from the...

in Britain and Scotland in the High Middle Ages. The change-continuity debate that derives from this division is currently one of the most active topics of discussion. For much of the twentieth century, scholars tended to stress the cultural change that took place in Scotland in the Norman era. However, many scholars, for instance Cynthia Neville

Cynthia Neville

Cynthia J Neville, FRHistS, FSAScot is a Canadian historian, medievalist and George Munro professor of history at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Neville's primary research interests are the social, political and cultural history of medieval Scotland, 1000-1500, specifically legal...

and Richard Oram

Richard Oram

Professor Richard D. Oram F.S.A. is a Scottish historian. He is a Professor of Medieval and Environmental History at the University of Stirling and an Honorary Lecturer in History at the University of Aberdeen. He is also the director of the Centre for Environmental History and Policy at the...

, while not ignoring cultural changes, are arguing that continuity with the Gaelic past was just as, if not more, important.

Origins of the Kingdom of Alba

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

, the province of Britannia

Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the part of the island of Great Britain controlled by the Roman Empire from AD 43 until ca. AD 410.The Romans referred to the imperial province as Britannia, which eventually comprised all of the island of Great Britain south of the fluid frontier with Caledonia...

formally ended at Hadrian's Wall

Hadrian's Wall

Hadrian's Wall was a defensive fortification in Roman Britain. Begun in AD 122, during the rule of emperor Hadrian, it was the first of two fortifications built across Great Britain, the second being the Antonine Wall, lesser known of the two because its physical remains are less evident today.The...

. Between this wall and the Antonine Wall

Antonine Wall

The Antonine Wall is a stone and turf fortification built by the Romans across what is now the Central Belt of Scotland, between the Firth of Forth and the Firth of Clyde. Representing the northernmost frontier barrier of the Roman Empire, it spanned approximately 39 miles and was about ten feet ...

, the Romans fostered a series of buffer states separating the Roman-occupied territory from the territory of the Picts

Picts

The Picts were a group of Late Iron Age and Early Mediaeval people living in what is now eastern and northern Scotland. There is an association with the distribution of brochs, place names beginning 'Pit-', for instance Pitlochry, and Pictish stones. They are recorded from before the Roman conquest...

. The development of "Pictland" itself, according to the historical model developed by Peter Heather, was a natural response to Roman imperialism. Around 400 the buffer states became the British

Brythonic languages

The Brythonic or Brittonic languages form one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic language family, the other being Goidelic. The name Brythonic was derived by Welsh Celticist John Rhys from the Welsh word Brython, meaning an indigenous Briton as opposed to an Anglo-Saxon or Gael...

kingdoms of "The Old North", and by 900 the Kingdom of the Picts had developed into the Gaelic

Gaels

The Gaels or Goidels are speakers of one of the Goidelic Celtic languages: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx. Goidelic speech originated in Ireland and subsequently spread to western and northern Scotland and the Isle of Man....

Kingdom of Alba

Kingdom of Alba

The name Kingdom of Alba pertains to the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900, and of Alexander III in 1286 which then led indirectly to the Scottish Wars of Independence...

.

In the tenth century, the Scottish elite began to develop a conquest myth to explain their Gaelicization, a myth often known as MacAlpin's Treason

MacAlpin's treason

MacAlpin's treason is a medieval legend which explains the replacement of the Pictish language by Gaelic in the 9th and 10th centuries.The legend tells of the murder of the nobles of Pictavia...

, in which Cináed mac Ailpín

Kenneth I of Scotland

Cináed mac Ailpín , commonly Anglicised as Kenneth MacAlpin and known in most modern regnal lists as Kenneth I was king of the Picts and, according to national myth, first king of Scots, earning him the posthumous nickname of An Ferbasach, "The Conqueror"...

is supposed to have annihilated the Picts in one fell takeover. The earliest versions include the Life of St Cathróe of Metz and royal genealogies

Genealogy

Genealogy is the study of families and the tracing of their lineages and history. Genealogists use oral traditions, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kinship and pedigrees of its members...

tracing their origin to Fergus Mór mac Eirc. In the reign of Máel Coluim III

Malcolm III of Scotland

Máel Coluim mac Donnchada , was King of Scots...

, the Duan Albanach

Duan Albanach

The Duan Albanach is a Middle Gaelic poem found with the Lebor Bretnach, a Gaelic version of the Historia Brittonum of Nennius, with extensive additional material ....

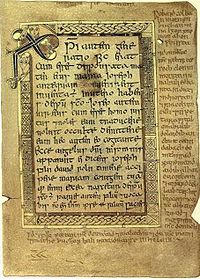

formalised the myth in Gaelic poetic tradition. In the 13th and 14th centuries, these mythical traditions were incorporated into the documents now in the Poppleton Manuscript

Poppleton manuscript

The Poppleton Manuscript is the name given to the fourteenth century codex likely compiled by Robert of Poppleton, a Carmelite friar who was the Prior of Hulne, near Alnwick. The manuscript contains numerous works, such as a map of the world , and works by Orosius, Geoffrey of Monmouth and Gerald...

, and in the Declaration of Arbroath

Declaration of Arbroath

The Declaration of Arbroath is a declaration of Scottish independence, made in 1320. It is in the form of a letter submitted to Pope John XXII, dated 6 April 1320, intended to confirm Scotland's status as an independent, sovereign state and defending Scotland's right to use military action when...

. They were believed in the early modern period, and beyond; even King James VI/I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

traced his origin to Fergus, saying, in his own words, that he was a "Monarch sprunge of Ferguse race".

However, modern historians are now beginning to reject this conceptualization of Scottish origins. No contemporary sources mention this conquest. Moreover, the Gaelicization of Pictland was a long process predating Cináed, and is evidenced by Gaelic-speaking Pictish rulers, Pictish royal patronage of Gaelic poets, Gaelic inscriptions, and Gaelic placenames. The term king of Alba, although only registered at the start of the tenth century, is possibly just a Gaelic translation of Pictland. The change of identity can perhaps be explained by the death of the Pictish language

Pictish language

Pictish is a term used for the extinct language or languages thought to have been spoken by the Picts, the people of northern and central Scotland in the Early Middle Ages...

, but also important may be Causantín II

Constantine II of Scotland

Constantine, son of Áed was an early King of Scotland, known then by the Gaelic name Alba. The Kingdom of Alba, a name which first appears in Constantine's lifetime, was in northern Great Britain...

's alleged Scoticisation of the "Pictish" Church and the trauma caused by Viking

Viking

The term Viking is customarily used to refer to the Norse explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided, traded, explored and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th century.These Norsemen used their famed longships to...

invasions, most strenuously felt in the Pictish Kingdom's heartland of Fortriu

Fortriu

Fortriu or the Kingdom of Fortriu is the name given by historians for an ancient Pictish kingdom, and often used synonymously with Pictland in general...

.

The Kingdom of Strathclyde

Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde , originally Brythonic Ystrad Clud, was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the celtic people called the Britons in the Hen Ogledd, the Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the post-Roman period...

on the valley of the river Clyde

River Clyde

The River Clyde is a major river in Scotland. It is the ninth longest river in the United Kingdom, and the third longest in Scotland. Flowing through the major city of Glasgow, it was an important river for shipbuilding and trade in the British Empire....

remained semi-independent, as did the Gaels of Argyll

Argyll

Argyll , archaically Argyle , is a region of western Scotland corresponding with most of the part of ancient Dál Riata that was located on the island of Great Britain, and in a historical context can be used to mean the entire western coast between the Mull of Kintyre and Cape Wrath...

and the islands to the west (formerly Dál Riata

Dál Riata

Dál Riata was a Gaelic overkingdom on the western coast of Scotland with some territory on the northeast coast of Ireland...

). The south-east had been absorbed by the English

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

Kingdom of Bernicia/Northumbria

Bernicia

Bernicia was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England....

in the seventh century, and other Germanic

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples are an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group of Northern European origin, identified by their use of the Indo-European Germanic languages which diversified out of Proto-Germanic during the Pre-Roman Iron Age.Originating about 1800 BCE from the Corded Ware Culture on the North...

invaders, the Norse

Norsemen

Norsemen is used to refer to the group of people as a whole who spoke what is now called the Old Norse language belonging to the North Germanic branch of Indo-European languages, especially Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese, Swedish and Danish in their earlier forms.The meaning of Norseman was "people...

, were beginning to incorporate much of the Western

Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides also known as the Western Isles and the Long Island, is an island chain off the west coast of Scotland. The islands are geographically contiguous with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland...

and Northern Isles

Northern Isles

The Northern Isles is a chain of islands off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The climate is cool and temperate and much influenced by the surrounding seas. There are two main island groups: Shetland and Orkney...

, as well as the Caithness

Caithness

Caithness is a registration county, lieutenancy area and historic local government area of Scotland. The name was used also for the earldom of Caithness and the Caithness constituency of the Parliament of the United Kingdom . Boundaries are not identical in all contexts, but the Caithness area is...

area. Galloway

Galloway

Galloway is an area in southwestern Scotland. It usually refers to the former counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire...

too was under strong Norse-Gaelic

Norse-Gaels

The Norse–Gaels were a people who dominated much of the Irish Sea region, including the Isle of Man, and western Scotland for a part of the Middle Ages; they were of Gaelic and Scandinavian origin and as a whole exhibited a great deal of Gaelic and Norse cultural syncretism...

influence, but there was no one kingdom in that area.

Gaelic kings: Domnall II to Alexander I

Donald II of Scotland

Domnall mac Causantín , anglicised as Donald II was King of the Picts or King of Scotland in the late 9th century. He was the son of Constantine I...

was the first man to have been called rí Alban (i.e. King of Alba) when he died at Dunnottar

Dunnottar Castle

Dunnottar Castle is a ruined medieval fortress located upon a rocky headland on the north-east coast of Scotland, about two miles south of Stonehaven. The surviving buildings are largely of the 15th–16th centuries, but the site is believed to have been an early fortress of the Dark Ages...

in 900 - this meant king of Britain or Scotland. All his predecessors bore the style of either King of the Picts or King of Fortriu. Such an apparent innovation in the Gaelic chronicles is occasionally taken to spell the birth of Scotland, but there is nothing special about his reign that might confirm this. Domnall had the nickname dásachtach. This simply meant a madman, or, in early Irish law, a man not in control of his functions and hence without legal culpability. The following long reign (900–942/3) of Domnall's successor Causantín

Constantine II of Scotland

Constantine, son of Áed was an early King of Scotland, known then by the Gaelic name Alba. The Kingdom of Alba, a name which first appears in Constantine's lifetime, was in northern Great Britain...

is more often regarded as the key to formation of the High Medieval Kingdom of Alba. Despite some setbacks, it was during his half-century reign that the Scots saw off any danger that the Vikings would expand their territory beyond the Western

Outer Hebrides

The Outer Hebrides also known as the Western Isles and the Long Island, is an island chain off the west coast of Scotland. The islands are geographically contiguous with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland...

and Northern Isles

Northern Isles

The Northern Isles is a chain of islands off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The climate is cool and temperate and much influenced by the surrounding seas. There are two main island groups: Shetland and Orkney...

and the Caithness

Caithness

Caithness is a registration county, lieutenancy area and historic local government area of Scotland. The name was used also for the earldom of Caithness and the Caithness constituency of the Parliament of the United Kingdom . Boundaries are not identical in all contexts, but the Caithness area is...

area.

The period between the accession of Máel Coluim I

Malcolm I of Scotland

Máel Coluim mac Domnaill was king of Scots , becoming king when his cousin Causantín mac Áeda abdicated to become a monk...

and Máel Coluim II

Malcolm II of Scotland

Máel Coluim mac Cináeda , was King of the Scots from 1005 until his death...

was marked by good relations with the Wessex

Wessex

The Kingdom of Wessex or Kingdom of the West Saxons was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the West Saxons, in South West England, from the 6th century, until the emergence of a united English state in the 10th century, under the Wessex dynasty. It was to be an earldom after Canute the Great's conquest...

rulers of England, intense internal dynastic disunity and, despite this, relatively successful expansionary policies. In 945, king Máel Coluim I received Strathclyde

Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde , originally Brythonic Ystrad Clud, was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the celtic people called the Britons in the Hen Ogledd, the Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the post-Roman period...

as part of a deal with King Edmund of England

Edmund I of England

Edmund I , called the Elder, the Deed-doer, the Just, or the Magnificent, was King of England from 939 until his death. He was a son of Edward the Elder and half-brother of Athelstan. Athelstan died on 27 October 939, and Edmund succeeded him as king.-Military threats:Shortly after his...

, an event offset somewhat by Máel Coluim's loss of control in Moray. Sometime in the reign of king Idulb

Indulf of Scotland

Ildulb mac Causantín, anglicised as Indulf, nicknamed An Ionsaighthigh, "the Aggressor" was king of Scots from 954. He was the son of Constantine II ; his mother may have been a daughter of Earl Eadulf I of Bernicia, who was an exile in Scotland.John of Fordun and others supposed that Indulf had...

(954–962), the Scots captured the fortress called oppidum Eden, i.e. Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

. Scottish control of Lothian

Lothian

Lothian forms a traditional region of Scotland, lying between the southern shore of the Firth of Forth and the Lammermuir Hills....

was strengthened with Máel Coluim II's victory over the Northumbrians at the Battle of Carham (1018). The Scots had probably had some authority in Strathclyde since the later part of the ninth century, but the kingdom kept its own rulers, and it is not clear that the Scots were always strong enough to enforce their authority.

The reign of King Donnchad I

Duncan I of Scotland

Donnchad mac Crínáin was king of Scotland from 1034 to 1040...

from 1034 was marred by failed military adventures, and he was defeated and killed by the Mormaer of Moray

Mormaer of Moray

The Mormaerdom or Kingdom of Moray was a lordship in High Medieval Scotland that was destroyed by King David I of Scotland in 1130. It did not have the same territory as the modern local government council area of Moray, which is a much smaller area, around Elgin...

, Mac Bethad mac Findláich

Macbeth of Scotland

Mac Bethad mac Findlaích was King of the Scots from 1040 until his death...

, who became king in 1040. Mac Bethad ruled for seventeen years, so peacefully that he was able to leave to go on pilgrimage

Pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey or search of great moral or spiritual significance. Typically, it is a journey to a shrine or other location of importance to a person's beliefs and faith...

to Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

. However, he was overthrown by Máel Coluim

Malcolm III of Scotland

Máel Coluim mac Donnchada , was King of Scots...

, the son of Donnchad who eighteen months later defeated Mac Bethad's successor Lulach to become king Máel Coluim III. In subsequent medieval propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

Donnchad's reign was portrayed positively, while Mac Bethad was vilified. William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon"...

followed this distorted history in describing both men in his play Macbeth

Macbeth

The Tragedy of Macbeth is a play by William Shakespeare about a regicide and its aftermath. It is Shakespeare's shortest tragedy and is believed to have been written sometime between 1603 and 1607...

.

House of Dunkeld

The so-called House of Dunkeld, in Scottish Gaelic Dùn Chailleann , is a historiographical and genealogical construct to illustrate the clear succession of Scottish kings from 1034 to 1040 and from 1058 to 1290.It is dynastically sort of a continuation to Cenél nGabráin of Dál Riata, "race of...

that ruled Scotland for the following two centuries, successfully compared to some. Part of the resource was the large number of children he had, perhaps as many as a dozen, through marriage to the widow or daughter of Thorfinn Sigurdsson, Earl of Orkney

Thorfinn Sigurdsson, Earl of Orkney

Thorfinn Sigurdsson , called Thorfinn the Mighty, was an 11th-century Earl of Orkney. One of five brothers , sons of Earl Sigurd Hlodvirsson by his marriage to the daughter of Malcolm II of Scotland...

and afterwards to the Anglo-Hungarian princess Margaret

Saint Margaret of Scotland

Saint Margaret of Scotland , also known as Margaret of Wessex and Queen Margaret of Scotland, was an English princess of the House of Wessex. Born in exile in Hungary, she was the sister of Edgar Ætheling, the short-ruling and uncrowned Anglo-Saxon King of England...

, granddaughter of Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside or Edmund II was king of England from 23 April to 30 November 1016. His cognomen "Ironside" is not recorded until 1057, but may have been contemporary. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, it was given to him "because of his valour" in resisting the Danish invasion led by Cnut...

. However, despite having a royal Anglo-Saxon

Anglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxon is a term used by historians to designate the Germanic tribes who invaded and settled the south and east of Great Britain beginning in the early 5th century AD, and the period from their creation of the English nation to the Norman conquest. The Anglo-Saxon Era denotes the period of...

wife, Máel Coluim spent much of his reign conducting slave

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

raids against the English, adding to the woes of that people in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest of England

Norman conquest of England

The Norman conquest of England began on 28 September 1066 with the invasion of England by William, Duke of Normandy. William became known as William the Conqueror after his victory at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, defeating King Harold II of England...

and the Harrying of the North

Harrying of the North

The Harrying of the North was a series of campaigns waged by William the Conqueror in the winter of 1069–1070 to subjugate Northern England, and is part of the Norman conquest of England...

. Marianus Scotus

Marianus Scotus

Marianus Scotus , was an Irish monk and chronicler , was an Irishman by birth, and called Máel Brigte, or Devotee of St...

narrates that "the Gaels and French devastated the English; and [the English] were dispersed and died of hunger; and were compelled to eat human flesh".

Máel Coluim's raids and attempts to further the claims for his successors to the English kingdom

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

prompted interference by the Norman rulers of England in the Scottish kingdom. He had married the sister of the native English claimant to the English throne, Edgar Ætheling, and had given most of his children by this marriage Anglo-Saxon royal names. In 1080, King William the Conqueror

William I of England

William I , also known as William the Conqueror , was the first Norman King of England from Christmas 1066 until his death. He was also Duke of Normandy from 3 July 1035 until his death, under the name William II...

sent his son on an invasion of Scotland, and Máel Coluim submitted to the authority of the king, giving his oldest son Donnchad as a hostage. King Máel Coluim himself died in one of the raids, in 1093.

Tradition would have made his brother Domnall Bán

Donald III of Scotland

Domnall mac Donnchada , anglicised as Donald III, and nicknamed Domnall Bán, "Donald the Fair" , was King of Scots from 1093–1094 and 1094–1097...

Máel Coluim's successor, but it seems that Edward, his eldest son by Margaret, was his chosen heir. With Máel Coluim and Edward dead in the same battle, and his other sons in Scotland still young, Domnall was made king. However, Donnchad II

Duncan II of Scotland

Donnchad mac Maíl Coluim was king of Scots...

, Máel Coluim's eldest son by his first wife, obtained some support from William Rufus

William II of England

William II , the third son of William I of England, was King of England from 1087 until 1100, with powers over Normandy, and influence in Scotland. He was less successful in extending control into Wales...

and took the throne, but according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

his English and French followers were massacred, and Donnchad II himself was killed later in the same year (1094) by Domnall's ally Máel Petair of Mearns

Máel Petair of Mearns

Máel Petair of Mearns is the only known Mormaer of the Mearns. His name means "tonsured one of Peter".One source tells us that Máel Petair was the son of a Máel Coluim, but tells us nothing about this. If this weren't bad enough, other sources say that his father was a man called "Loren", and in...

. However, in 1097, William Rufus sent another of Máel Coluim's sons, Edgar

Edgar of Scotland

Edgar or Étgar mac Maíl Choluim , nicknamed Probus, "the Valiant" , was king of Alba from 1097 to 1107...

, to take the kingship. The ensuing death of Domnall Bán secured the kingship for Edgar, and there followed a period of relative peace. The reigns of both Edgar and his successor Alexander

Alexander I of Scotland

Alexander I , also called Alaxandair mac Maíl Coluim and nicknamed "The Fierce", was King of the Scots from 1107 to his death.-Life:...

are obscure in comparison with their successors. The former's most notable act was to send a camel

Camel

A camel is an even-toed ungulate within the genus Camelus, bearing distinctive fatty deposits known as humps on its back. There are two species of camels: the dromedary or Arabian camel has a single hump, and the bactrian has two humps. Dromedaries are native to the dry desert areas of West Asia,...

(or perhaps an elephant

Elephant

Elephants are large land mammals in two extant genera of the family Elephantidae: Elephas and Loxodonta, with the third genus Mammuthus extinct...

) to his fellow Gael Muircheartach Ua Briain

Muircheartach Ua Briain

Muircheartach Ua Briain , son of Toirdelbach Ua Briain and great-grandson of Brian Bóruma, was King of Munster and later self declared High King of Ireland.-Background:...

, High King of Ireland

High King of Ireland

The High Kings of Ireland were sometimes historical and sometimes legendary figures who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over the whole of Ireland. Medieval and early modern Irish literature portrays an almost unbroken sequence of High Kings, ruling from Tara over a hierarchy of...

. When Edgar died, Alexander took the kingship, while his youngest brother David became Prince of "Cumbria" and ruler of Lothian.

Scoto-Norman kings: David I to Alexander III

David I of Scotland

David I or Dabíd mac Maíl Choluim was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians and later King of the Scots...

and the death of Alexander III

Alexander III of Scotland

Alexander III was King of Scots from 1249 to his death.-Life:...

was marked by dependency upon and relatively good relations with the Kings of England. As long as one remembers the continuities, the period can also be regarded as one of great historical transformation, part of a more general phenomenon which has been called the "Europeanisation of Europe". As a related matter, the period witnessed the successful imposition of royal authority across most of the modern country. After David I, and especially in the reign of William I

William I of Scotland

William the Lion , sometimes styled William I, also known by the nickname Garbh, "the Rough", reigned as King of the Scots from 1165 to 1214...

, Scotland's Kings became ambivalent about the culture of most of their subjects. As Walter of Coventry

Walter of Coventry

Walter of Coventry , English monk and chronicler, who was apparently connected with a religious house in the province of York, is known to us only through the historical compilation which bears his name, the Memoriale fratris Walteri de Coventria....

tells us, "The modern kings of Scotland count themselves as Frenchmen, in race, manners, language and culture; they keep only Frenchmen in their household and following, and have reduced the Gaels to utter servitude."

The ambivalence of the kings was matched to a certain extent by the Scots themselves. In the aftermath of William's capture at Alnwick

Alnwick

Alnwick is a small market town in north Northumberland, England. The town's population was just over 8000 at the time of the 2001 census and Alnwick's district population was 31,029....

in 1174, the Scots turned on the small number of Middle English

Middle English

Middle English is the stage in the history of the English language during the High and Late Middle Ages, or roughly during the four centuries between the late 11th and the late 15th century....

-speakers and French-speakers among them. William of Newburgh

William of Newburgh

William of Newburgh or Newbury , also known as William Parvus, was a 12th-century English historian and Augustinian canon from Bridlington, Yorkshire.-Biography:...

related that the Scots first attacked the Scoto-English in their own army, and Newburgh reported a repetition of these events in Scotland itself. Walter Bower

Walter Bower

Walter Bower , Scottish chronicler, was born about 1385 at Haddington, East Lothian.He was abbot of Inchcolm Abbey from 1418, was one of the commissioners for the collection of the ransom of James I, King of Scots, in 1423 and 1424, and in 1433 one of the embassy to Paris on the business of the...

, writing a few centuries later albeit, wrote about the same events, and confirms that "there took place a most wretched and widespread persecution of the English both in Scotland and Galloway".

Óengus of Moray

Óengus of Moray was the last King of Moray of the native line, ruling Moray in what is now northeastern Scotland from some unknown date until his death in 1130....

, the Mormaer of Moray

Mormaer of Moray

The Mormaerdom or Kingdom of Moray was a lordship in High Medieval Scotland that was destroyed by King David I of Scotland in 1130. It did not have the same territory as the modern local government council area of Moray, which is a much smaller area, around Elgin...

. Other important resistors to the expansionary Scottish kings were Somairle mac Gillai Brigte

Somerled

Somerled was a military and political leader of the Scottish Isles in the 12th century who was known in Gaelic as rí Innse Gall . His father was Gillebride...

, Fergus of Galloway

Fergus of Galloway

Fergus of Galloway was King, or Lord, of Galloway from an unknown date , until his death in 1161. He was the founder of that "sub-kingdom," the resurrector of the Bishopric of Whithorn, the patron of new abbeys , and much else besides...

, Gille Brigte, Lord of Galloway

Gille Brigte, Lord of Galloway

Gille Brigte or Gilla Brigte mac Fergusa of Galloway , also known as Gillebrigte, Gille Brighde, Gilbridge, Gilbride, etc., and most famously known in French sources as Gilbert, was Lord of Galloway of Scotland...

and Harald Maddadsson

Harald Maddadsson

Harald Maddadsson was Earl of Orkney and Mormaer of Caithness from 1139 until 1206. He was the son of Matad, Mormaer of Atholl, and Margaret, daughter of Earl Haakon Paulsson of Orkney...

, along with two kin-groups known today as the MacHeths

MacHeths

The MacHeths were a Gaelic kindred who raised several rebellions against the Scotto-Norman kings of Scotland in the 12th and 13th centuries. Their origins have long been debated.-Origins:...

and the MacWilliams

MacWilliams

MacWilliams and MacWilliam is a surname, originating from Meic Uilleim. Some notable MacWilliams are:*Dave MacWilliams, soccer player*Jessie MacWilliams, mathematician*Keenan MacWilliam, actress*Lyle MacWilliam, Canadian congressman...

. The latter claimed descent from king Donnchad II

Duncan II of Scotland

Donnchad mac Maíl Coluim was king of Scots...

, through his son William fitz Duncan

William fitz Duncan

William fitz Duncan was a Scottish prince, a territorial magnate in northern Scotland and northern England, a general and the legitimate son of king Donnchad II of Scotland by Athelreda of Dunbar.In 1094, his father Donnchad II was killed by Mormaer Máel Petair of...

. The MacWilliams appear to have rebelled for no less a reason than the Scottish throne itself. The threat was so grave that, after the defeat of the MacWilliams in 1230, the Scottish crown ordered the public execution of the infant girl who happened to be the last of the MacWilliam line. This was how the Lanercost Chronicle related the fate of this last MacWilliam:

Lochlann, Lord of Galloway

Lochlann , also known by his French name Roland, was the son and successor of Uchtred, Lord of Galloway as the "Lord" or "sub-king" of eastern Galloway....

and Ferchar mac in tSagairt

Fearchar, Earl of Ross

Fearchar of Ross or Ferchar mac in tSagairt , was the first Mormaer or Earl of Ross we know of from the thirteenth century, whose career brought Ross into the fold of the Scottish kings for the first time, and who is remembered as the founder of the Earldom of Ross.-Origins:The traditional...

. Cumulatively, by the reign of Alexander III, the Scots were in a strong position to annex the remainder of the western seaboard, which they did in 1265, with the Treaty of Perth

Treaty of Perth

The Treaty of Perth, 1266, ended military conflict between Norway, under King Magnus VI of Norway, and Scotland, under King Alexander III, over the sovereignty of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man....

. The conquest of the west, the creation of the Mormaerdom of Carrick in 1186 and the absorption of the Lordship of Galloway

Lords of Galloway

The Lords, or Kings of Galloway ruled over Galloway, in south west Scotland, for a large part of the High Middle Ages.Many regions of Scotland, including Galloway and Moray, periodically had kings or subkings, similar to those in Ireland during the Middle Ages. The Scottish monarch was seen as...

after the Galwegian revolt of Gille Ruadh

Gille Ruadh

Gille Ruadh was the Galwegian leader who led the revolt against King Alexander II of Scotland. Also called Gilla Ruadh, Gilleroth, Gilrod, Gilroy, etc....

in 1235 meant that the number and proportion of Gaelic speakers under the rule of the Scottish king actually increased, and perhaps even doubled, in the so-called Norman period. It was the Gaels and Gaelicised warriors of the new west, and the power they offered, that enabled King Robert I

Robert I of Scotland

Robert I , popularly known as Robert the Bruce , was King of Scots from March 25, 1306, until his death in 1329.His paternal ancestors were of Scoto-Norman heritage , and...

(himself a Gaelicised Scoto-Norman

Scoto-Norman

The term Scoto-Norman is used to described people, families, institutions and archaeological artifacts that are partly Scottish and partly Norman...

of Carrick

Carrick, Scotland

Carrick is a former comital district of Scotland which today forms part of South Ayrshire.-History:The word Carrick comes from the Gaelic word Carraig, meaning rock or rocky place. Maybole was the historic capital of Carrick. The county was eventually combined into Ayrshire which was divided...

) to emerge victorious during the Wars of Independence, which followed soon after the death of Alexander III.

Other kingdoms

Royal family

A royal family is the extended family of a king or queen regnant. The term imperial family appropriately describes the extended family of an emperor or empress, while the terms "ducal family", "grand ducal family" or "princely family" are more appropriate to describe the relatives of a reigning...

authority in northern Britain. Until the Norman era, and perhaps even until the reign of Alexander II, the Scottish king controlled only a minority of the people who lived inside the boundary of modern Scotland, in the same way as the French monarchs of the Middle Ages only had control of patches of what is now modern France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

. The ruler of Moray

Mormaer of Moray

The Mormaerdom or Kingdom of Moray was a lordship in High Medieval Scotland that was destroyed by King David I of Scotland in 1130. It did not have the same territory as the modern local government council area of Moray, which is a much smaller area, around Elgin...

was called not only king in both Scandinavian and Irish sources, but before Máel Snechtai

Máel Snechtai of Moray

Máel Snechtai of Moray was the ruler of Moray, and, as his name suggests, the son of Lulach, King of Scotland.He is called on his death notice in the Annals of Ulster, "Máel Snechtai m...

, king of Alba/Scotland. After Máel Snechtai, Irish sources call them merely kings of Moray

Moray

Moray is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland. It lies in the north-east of the country, with coastline on the Moray Firth, and borders the council areas of Aberdeenshire and Highland.- History :...

. The rulers of Moray took over the entire Scottish kingdom under the famous Mac Bethad mac Findláich

Macbeth of Scotland

Mac Bethad mac Findlaích was King of the Scots from 1040 until his death...

(1040–1057) and his successor Lulach mac Gillai Choemgáin

Lulach of Scotland

Lulach mac Gille Coemgáin was King of Scots between 15 August 1057 and 17 March 1058.He appears to have been a weak king, as his nicknames suggest...

(1057–1058). However, Moray was subjugated by the Scottish kings after 1130, when the last native ruler, Óengus of Moray

Óengus of Moray

Óengus of Moray was the last King of Moray of the native line, ruling Moray in what is now northeastern Scotland from some unknown date until his death in 1130....

was defeated in an attempt to seize the Scottish throne.

Galloway, likewise, was a Lordship with some regality. In a Galwegian

Galwegian Gaelic

Galwegian Gaelic is an extinct dialect of Scottish Gaelic formerly spoken in southwest Scotland. It was spoken by the independent kings of Galloway in their time, and by the people of Galloway and Carrick until the early modern period. It was once spoken in Annandale and Strathnith...

charter dated to the reign of Fergus

Fergus of Galloway

Fergus of Galloway was King, or Lord, of Galloway from an unknown date , until his death in 1161. He was the founder of that "sub-kingdom," the resurrector of the Bishopric of Whithorn, the patron of new abbeys , and much else besides...

, the Galwegian ruler styled himself rex Galwitensium, King of Galloway; Irish chroniclers continued to call Fergus' successors King. Although the Scots obtained greater control after the death of Gilla Brigte

Gille Brigte, Lord of Galloway

Gille Brigte or Gilla Brigte mac Fergusa of Galloway , also known as Gillebrigte, Gille Brighde, Gilbridge, Gilbride, etc., and most famously known in French sources as Gilbert, was Lord of Galloway of Scotland...

and the installation of Lochlann/Roland

Lochlann, Lord of Galloway

Lochlann , also known by his French name Roland, was the son and successor of Uchtred, Lord of Galloway as the "Lord" or "sub-king" of eastern Galloway....

in 1185, Galloway was not fully absorbed by Scotland until 1235, after the rebellion of the Galwegians was crushed.

Galloway and Moray were not the only other territories whose rulers had regal status. Both the rulers of Mann

Isle of Man

The Isle of Man , otherwise known simply as Mann , is a self-governing British Crown Dependency, located in the Irish Sea between the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, within the British Isles. The head of state is Queen Elizabeth II, who holds the title of Lord of Mann. The Lord of Mann is...

& the Isles

Hebrides

The Hebrides comprise a widespread and diverse archipelago off the west coast of Scotland. There are two main groups: the Inner and Outer Hebrides. These islands have a long history of occupation dating back to the Mesolithic and the culture of the residents has been affected by the successive...

, and the rulers of Argyll had the status of kings, even if some southern Latin writers called them merely reguli (i.e. "kinglets"). The Mormaers of Lennox referred to their predecessors as Kings of Balloch

Balloch, West Dunbartonshire

Balloch is a small town in West Dunbartonshire, Scotland, at the foot of Loch Lomond. The name comes from the Gaelic for "the pass".Balloch is at the north end of the Vale of Leven, straddling the River Leven itself. It connects to the larger town of Alexandria and to the smaller village of...

, many of the Mormaerdoms had already been kingdoms at an earlier stage. Another kingdom, Strathclyde

Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde , originally Brythonic Ystrad Clud, was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the celtic people called the Britons in the Hen Ogledd, the Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the post-Roman period...

(or Cumbria), had been incorporated into Scotland in a slow process that started in the 9th century and was not fully realised until perhaps the 12th.

Geography

Neither the political nor the theoretical boundaries of Scotland in this period, as both AlbaAlba

Alba is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is cognate to Alba in Irish and Nalbin in Manx, the two other Goidelic Insular Celtic languages, as well as similar words in the Brythonic Insular Celtic languages of Cornish and Welsh also meaning Scotland.- Etymology :The term first appears in...

and Scotia

Scotia

Scotia was originally a Roman name for Ireland, inhabited by the people they called Scoti or Scotii. Use of the name shifted in the Middle Ages to designate the part of the island of Great Britain lying north of the Firth of Forth, the Kingdom of Alba...

, corresponded exactly to modern Scotland. The closest approximation came at the end of the period, when the Treaty of York

Treaty of York

The Treaty of York was an agreement between Henry III of England and Alexander II of Scotland, signed at York on 25 September 1237. It detailed the future status of several feudal properties and addressed other issues between the two kings, and indirectly marked the end of Scotland's attempts to...

(1237) and Treaty of Perth

Treaty of Perth

The Treaty of Perth, 1266, ended military conflict between Norway, under King Magnus VI of Norway, and Scotland, under King Alexander III, over the sovereignty of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man....

(1266) fixed the boundaries between the Kingdom of the Scots with England and Norway

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

respectively; although in neither case did this border exactly match the modern one, Berwick

Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed or simply Berwick is a town in the county of Northumberland and is the northernmost town in England, on the east coast at the mouth of the River Tweed. It is situated 2.5 miles south of the Scottish border....

and the Isle of Man

Isle of Man

The Isle of Man , otherwise known simply as Mann , is a self-governing British Crown Dependency, located in the Irish Sea between the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, within the British Isles. The head of state is Queen Elizabeth II, who holds the title of Lord of Mann. The Lord of Mann is...

being eventually lost to England, and Orkney and Shetland later being gained from Norway.

Until the thirteenth century, Scotland referred to the land to the north of the river Forth

River Forth

The River Forth , long, is the major river draining the eastern part of the central belt of Scotland.The Forth rises in Loch Ard in the Trossachs, a mountainous area some west of Stirling...

, and for this reason historians sometimes use the term "Scotland-proper". By the middle of the thirteenth century, Scotland could include all the lands ruled by the King of Scots, but the older concept of Scotland remained throughout the period.

For legal and administrative purposes, the Kingdom of the Scots was divided into three, four or five zones: Scotland-proper (north and south of the Grampians), Lothian, Galloway and, earlier, Strathclyde. Like Scotland, neither Lothian nor Galloway had its modern meaning. Lothian could refer to the entire Middle English

Middle English

Middle English is the stage in the history of the English language during the High and Late Middle Ages, or roughly during the four centuries between the late 11th and the late 15th century....

-speaking south-east, and latterly, included much of Strathclyde. Galloway could refer to the entire Gaelic-speaking south-west. Lothian was divided from Scotland-proper by the river Forth. To quote the early thirteenth century tract, de Situ Albanie

De Situ Albanie

De Situ Albanie is the name given to the first of seven Scottish documents found in the so-called Poppleton Manuscript, now in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris...

,

Here Scottish refers to the language now called the Middle Irish language

Middle Irish language

Middle Irish is the name given by historical philologists to the Goidelic language spoken in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man from the 10th to 12th centuries; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old English and early Middle English...

, British to the Welsh language

Welsh language

Welsh is a member of the Brythonic branch of the Celtic languages spoken natively in Wales, by some along the Welsh border in England, and in Y Wladfa...

and Romance to the Old French language, which had borrowed the term Scottewatre from the Middle English language.

In this period, little of Scotland was governed by the crown. Instead, most Scots lay under the intermediate control of Gaelic

Middle Irish language

Middle Irish is the name given by historical philologists to the Goidelic language spoken in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man from the 10th to 12th centuries; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old English and early Middle English...

and increasingly after the twelfth century, French-speaking Mormaers/Earls and Lords.

Economy

The Scottish economy of this period was dominated by agriculture and by short-distance, local trade. There was an increasing amount of foreign trade in the period, as well as exchange gained by means of military plunder. By the end of this period, coins were replacing barter goodsBarter

Barter is a method of exchange by which goods or services are directly exchanged for other goods or services without using a medium of exchange, such as money. It is usually bilateral, but may be multilateral, and usually exists parallel to monetary systems in most developed countries, though to a...

, but for most of this period most exchange was done without the use of metal currency.

Pastoralism

Pastoralism or pastoral farming is the branch of agriculture concerned with the raising of livestock. It is animal husbandry: the care, tending and use of animals such as camels, goats, cattle, yaks, llamas, and sheep. It may have a mobile aspect, moving the herds in search of fresh pasture and...

, rather than arable farming

Arable land

In geography and agriculture, arable land is land that can be used for growing crops. It includes all land under temporary crops , temporary meadows for mowing or pasture, land under market and kitchen gardens and land temporarily fallow...

. Arable farming grew significantly in the "Norman period", but with geographical differences, low-lying areas being subject to more arable farming than high-lying areas such as the Highlands

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands is an historic region of Scotland. The area is sometimes referred to as the "Scottish Highlands". It was culturally distinguishable from the Lowlands from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands...

, Galloway

Galloway

Galloway is an area in southwestern Scotland. It usually refers to the former counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire...

and the Southern Uplands

Southern Uplands

The Southern Uplands are the southernmost and least populous of mainland Scotland's three major geographic areas . The term is used both to describe the geographical region and to collectively denote the various ranges of hills within this region...

. Galloway, in the words of G.W.S. Barrow, "already famous for its cattle, was so overwhelmingly pastoral, that there is little evidence in that region of land under any permanent cultivation, save along the Solway coast." The average amount of land used by a husbandman in Scotland might have been around 26 acres. There is a lot of evidence that the native Scots favoured pastoralism, in that Gaelic lords were happier to give away more land to French and Middle English-speaking settlers, whilst holding on tenaciously to more high-lying regions, perhaps contributing to the Highland/Galloway-Lowland division that emerged in Scotland in the later Middle Ages. The main unit of land measurement in Scotland was the davoch (i.e. "vat"), called the arachor in Lennox

Lennox (district)

The district of Lennox , often known as "the Lennox", is a region of Scotland centred around the village of Lennoxtown in East Dunbartonshire, eight miles north of the centre of Glasgow. At various times in history, the district has had both a dukedom and earldom associated with it.- External...

. This unit is also known as the "Scottish ploughgate." In English-speaking Lothian, it was simply ploughgate

Ploughgate

A ploughgate was a Scottish land measurement, used in the south and the east of the country. It was supposed to be the area that eight oxen were said to be able to plough in one year. Because of the variable land quality in Scotland, this could be a number of different actual land areas...

. It may have measured about 104 acre (0.42087344 km²), divided into 4 raths. Cattle, pigs and cheeses were among the most produced foodstuffs, but of course a vast range of foodstuffs were produced, from sheep and fish, rye and barley, to bee wax and honey.

Pre-Davidian Scotland had no known chartered burghs, though most, if not all, of the burghs granted charters by the crown already existed long before the reign of David I but he gave them legal status - a new form of recognition. Scotland, outside Lothian, Lanarkshire, Roxburghshire, Berwickshire, Angus, Aberdeenshire and Fife at least, largely was populated by scattered hamlets, and outside that area, lacked the continental style nucleated village. David I established the first chartered burghs in Scotland. David I copied the burgher charters and Leges Burgorum (rules governing virtually every aspect of life and work in a burgh) almost verbatim from the English customs of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne. Early burgesses were usually Flemish, English

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

, French

French people

The French are a nation that share a common French culture and speak the French language as a mother tongue. Historically, the French population are descended from peoples of Celtic, Latin and Germanic origin, and are today a mixture of several ethnic groups...

and German

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

, rather than Gaelic Scots. The burgh’s vocabulary was composed totally of either Germanic and French terms. The councils which ran individual burghs were individually known as lie doussane, meaning the dozen.

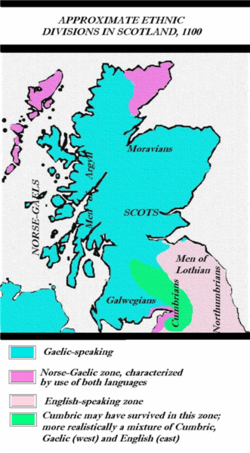

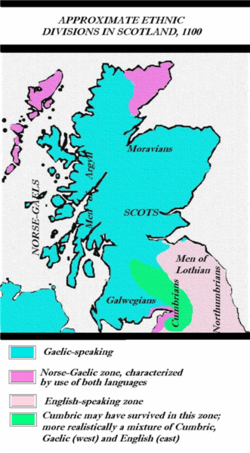

Demographics

Linguistically, the vast majority of people within Scotland throughout this period spoke the Gaelic

Middle Irish language

Middle Irish is the name given by historical philologists to the Goidelic language spoken in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man from the 10th to 12th centuries; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old English and early Middle English...

language, then simply called Scottish, or in Latin, lingua Scotica. Other languages spoken throughout this period were Norse and English, with the Cumbric language

Cumbric language

Cumbric was a variety of the Celtic British language spoken during the Early Middle Ages in the Hen Ogledd or "Old North", or what is now northern England and southern Lowland Scotland, the area anciently known as Cumbria. It was closely related to Old Welsh and the other Brythonic languages...

disappearing somewhere between 900 and 1100. Pictish may have survived into this period, but there is little evidence for this. After the accession of David I

David I of Scotland

David I or Dabíd mac Maíl Choluim was a 12th-century ruler who was Prince of the Cumbrians and later King of the Scots...

, or perhaps before, Gaelic ceased to be the main language of the royal court. From his reign until the end of the period, the Scottish monarchs probably favoured the French language, as evidenced by reports from contemporary chronicles, literature and translations of administrative documents into the French language.

Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic language

Scottish Gaelic is a Celtic language native to Scotland. A member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic languages, Scottish Gaelic, like Modern Irish and Manx, developed out of Middle Irish, and thus descends ultimately from Primitive Irish....

displaced Norse in much of the Norse-Gaelic

Norse-Gaels

The Norse–Gaels were a people who dominated much of the Irish Sea region, including the Isle of Man, and western Scotland for a part of the Middle Ages; they were of Gaelic and Scandinavian origin and as a whole exhibited a great deal of Gaelic and Norse cultural syncretism...

region, but itself lost ground to English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

in much of the region between Scotland-proper

Scotia

Scotia was originally a Roman name for Ireland, inhabited by the people they called Scoti or Scotii. Use of the name shifted in the Middle Ages to designate the part of the island of Great Britain lying north of the Firth of Forth, the Kingdom of Alba...

and Galloway

Galloway

Galloway is an area in southwestern Scotland. It usually refers to the former counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire...

. English, with French and Flemish, became the main language of Scottish towns (burghs), which were created for the first time under David I. However, burghs were, in Barrow's words, “scarcely more than villages … numbered in hundreds rather than thousands”, and Norman knights were a similarly tiny in number when compared with the Gaelic population of Scotland outside of Lothian.

Society

Medieval Scottish society was stratified. The hierarchical structure of statusSocial status

In sociology or anthropology, social status is the honor or prestige attached to one's position in society . It may also refer to a rank or position that one holds in a group, for example son or daughter, playmate, pupil, etc....

in early Gaelic society is well-documented, owing primarily to the large body of extant legal texts and tracts from this period. The legal tract known as Laws of Brets and Scots, lists five grades of man: King, mormaer

Mormaer

The title of Mormaer designates a regional or provincial ruler in the medieval Kingdom of the Scots. In theory, although not always in practice, a Mormaer was second only to the King of Scots, and the senior of a toisech.-Origin:...

/earl

Earl

An earl is a member of the nobility. The title is Anglo-Saxon, akin to the Scandinavian form jarl, and meant "chieftain", particularly a chieftain set to rule a territory in a king's stead. In Scandinavia, it became obsolete in the Middle Ages and was replaced with duke...

, toísech/thane, ócthigern and serf. In pre-twelfth century Scotland slave was a social status as well. The standard differentiation in medieval European society between the bellatores ("those who fight", i.e. aristocrats), the oratores ("those who pray", i.e. clergy) and the laboratores ("those who work", i.e. peasants) was useless for understanding Scottish society in the earlier period, but becomes more useful in the post-Davidian period.

Scotia

Scotia was originally a Roman name for Ireland, inhabited by the people they called Scoti or Scotii. Use of the name shifted in the Middle Ages to designate the part of the island of Great Britain lying north of the Firth of Forth, the Kingdom of Alba...

was directly under a lord who in medieval Scottish

Middle Irish language

Middle Irish is the name given by historical philologists to the Goidelic language spoken in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man from the 10th to 12th centuries; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old English and early Middle English...

was called a Mormaer

Mormaer

The title of Mormaer designates a regional or provincial ruler in the medieval Kingdom of the Scots. In theory, although not always in practice, a Mormaer was second only to the King of Scots, and the senior of a toisech.-Origin:...

. The term was translated into Latin as comes, and is misleadingly translated into modern English as Earl

Earl

An earl is a member of the nobility. The title is Anglo-Saxon, akin to the Scandinavian form jarl, and meant "chieftain", particularly a chieftain set to rule a territory in a king's stead. In Scandinavia, it became obsolete in the Middle Ages and was replaced with duke...

. These secular lords exercised secular power and religious patronage like kings in miniature. They kept their own warbands and followers, issued charters and supervised law and internal order within their provinces. When actually under the power of the Scottish king, they were responsible for rendering to the king cain, a tribute paid several times a year, usually in cattle and other barter goods. They also had to provide for the king conveth, a kind of hospitality payment, paid by putting-up the lord on a visit with food and accommodation, or with barter payments in lieu of this. In the Norman era, they provided the servitum Scoticanum ("Gaelic service", "Scottish service" or simply forinsec) and led the exercitus Scoticanus , the Gaelic part of the king's army that made up the vast majority almost any national hosting (slógad) in the period.

A toísech ("chieftain") was like a mormaer, providing for his lord the same services that a mormaer provided for the king. The Latin word usually used is thanus, which is why the office-bearers are often called "thanes" in English. The formalization of this institution was largely confined to eastern Scotland north of the Forth, and only two of the seventy-one known thanages existed south of that river. Behind the offices of toísech and mormaer were kinship groups

Clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, clan members may be organized around a founding member or apical ancestor. The kinship-based bonds may be symbolical, whereby the clan shares a "stipulated" common ancestor that is a...

. Sometimes these offices were formalised, but mostly they are informal. The head of the kinship group was called capitalis in Latin and cenn in medieval Gaelic

Middle Irish language

Middle Irish is the name given by historical philologists to the Goidelic language spoken in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man from the 10th to 12th centuries; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old English and early Middle English...

. In the Mormaerdom of Fife, the primary kinship group was known then as Clann MacDuib ("Children of MacDuff

Clan MacDuff

Clan MacDuff is a Scottish armigerous clan, which is registered with Lyon Court, though currently without a chief. Moncreiffe wrote that the Clan MacDuff was the premier clan among the Scottish Gaels. The early chiefs of Clan MacDuff were the Earls of Fife...

"). Others include the Cennedig (from Carrick

Carrick, Scotland

Carrick is a former comital district of Scotland which today forms part of South Ayrshire.-History:The word Carrick comes from the Gaelic word Carraig, meaning rock or rocky place. Maybole was the historic capital of Carrick. The county was eventually combined into Ayrshire which was divided...

), Morggain (from Buchan

Buchan

Buchan is one of the six committee areas and administrative areas of Aberdeenshire Council, Scotland. These areas were created by the council in 1996, when the Aberdeenshire unitary council area was created under the Local Government etc Act 1994...

), and the MacDowalls (from Galloway

Galloway

Galloway is an area in southwestern Scotland. It usually refers to the former counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire...

). There were probably hundreds in total, mostly unrecorded.

The highest non-noble rank was, according to the Laws of Brets and Scots, called the ócthigern (literally, little or young lord), a term the text does not bother to translate into French. The Anglo-Saxon equivalent was perhaps the sokeman. Other known ranks include the scoloc, perhaps equivalent to the Anglo-Saxon gerseman. In the earlier period, the Scots kept slaves, and many of these were foreigners (English or Scandinavian) captured during warfare. Large-scale Scottish slave-raids are particularly well documented in the eleventh century.

Law and government

Common law

Common law is law developed by judges through decisions of courts and similar tribunals rather than through legislative statutes or executive branch action...

began to take shape at the end of the period, assimilating Gaelic and Celtic law with practices from Anglo-Norman England and the Continent. In the twelfth century, and certainly in the thirteenth, strong continental legal influences began to have more effect, such as Canon law

Canon law (Catholic Church)

The canon law of the Catholic Church, is a fully developed legal system, with all the necessary elements: courts, lawyers, judges, a fully articulated legal code and principles of legal interpretation. It lacks the necessary binding force present in most modern day legal systems. The academic...

and various Anglo-Norman practices. Pre-fourteenth century law

Law

Law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior, wherever possible. It shapes politics, economics and society in numerous ways and serves as a social mediator of relations between people. Contract law regulates everything from buying a bus...

amongst the native Scots is not always well attested. However, our extensive knowledge of early Gaelic Law

Brehon Laws

Early Irish law refers to the statutes that governed everyday life and politics in Early Medieval Ireland. They were partially eclipsed by the Norman invasion of 1169, but underwent a resurgence in the 13th century, and survived into Early Modern Ireland in parallel with English law over the...

gives some basis for reconstructing pre-fourteenth century Scottish law. In the earliest extant Scottish legal manuscript, there is a document called Leges inter Brettos et Scottos. The document survives in Old French, and is almost certainly a French translation of an earlier Gaelic document. The document retained untranslated a vast number of Gaelic legal terms. Later medieval legal documents, written both in Latin and Middle English, contain more Gaelic legal terms, examples including slains (Old Irish slán or sláinte; exemption) and cumherba (Old Irish comarba; ecclesiastic heir).

A Judex (pl. judices) represents a post-Norman continuity with the ancient Gaelic orders of lawmen called in English today Brehons. Bearers of the office almost always have Gaelic names north of the Forth or in the south-west

Galloway

Galloway is an area in southwestern Scotland. It usually refers to the former counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire...

. Judices were often royal officials who supervised baronial, abbatial and other lower-ranking "courts". However, the main official of law in the post-Davidian Kingdom of the Scots was the Justiciar

Justiciar

In medieval England and Ireland the Chief Justiciar was roughly equivalent to a modern Prime Minister as the monarch's chief minister. Similar positions existed on the Continent, particularly in Norman Italy. The term is the English form of the medieval Latin justiciarius or justitiarius In...

. The institution has Anglo-Norman origins, but in Scotland north of the Forth it probably represented some form of continuity with an older office. For instance, Mormaer Causantín of Fife is styled judex magnus (i.e. great Brehon), and it seems that the Justiciarship of Scotia was just a further Latinisation/Normanisation of that position. The formalised office of the Justiciar held responsibility for supervising the activity and behaviour of royal sheriffs and sergeants, held courts and reported on these things to the king personally. Normally, there were two Justiciarships, organised by linguistic boundaries: the Justiciar of Scotia and the Justiciar of Lothian. Sometimes Galloway had its own Justiciar too.

The office of Justiciar and Judex were just two ways that Scottish society was governed. In the earlier period, the king "delegated" power to hereditary native "officers" such as the Mormaers/Earls and Toísechs/Thanes. It was a government

Government

Government refers to the legislators, administrators, and arbitrators in the administrative bureaucracy who control a state at a given time, and to the system of government by which they are organized...