Sidney Reilly

Encyclopedia

Lieutenant

Sidney George Reilly, MC

(c.

March 24, 1873/1874 – November 5, 1925), famously known as the Ace of Spies, was a Jewish Russia

n-born adventurer and secret agent

employed by Scotland Yard

, the British

Secret Service Bureau and later the Secret Intelligence Service

(SIS). He is alleged to have spied for at least four nations. His notoriety during the 1920s was created in part by his friend, British diplomat and journalist Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart, who sensationalised their thwarted operation to overthrow the Bolshevik government

in 1918.

After Reilly's death, the London Evening Standard published in May, 1931, a Master Spy serial glorifying his exploits. Later, Ian Fleming

would use Reilly as a model for

James Bond

. Today, many historians consider Reilly to be the first 20th century super-spy. Much of what is thought to be known about him could be false, as Reilly was a master of deception, and most of his life is shrouded in legend.

.

Apparently, Reilly was born Georgi Rosenblum in Odessa

, then a Black Sea port of the Russian Empire

(now Ukraine

), on March 24, 1874 (Lockhart 1986); however, other theories of Reilly's birth place and origins exist. In Ace of Spies: The True Story of Sidney Reilly (pg. 28), author Andrew Cook states that Reilly was born on March 24, 1873, in the Jewish Kherson

gubernia of Tsarist Russia, as Salomon (Shlomo) Rosenblum, and later that "Sidney Reilly" was the illegitimate son of Paulina (Perla), his acknowledged mother, and Dr. Mikhail Abramovich Rosenblum, the trusted first cousin of Reilly's putative father, Grigory (Hersh) Rosenblum. There is speculation that he was the son of a merchant marine captain and the above-mentioned mother.

According to Rosenblum, in 1892, the Imperial Russian Secret Police (Czarist Ochrana) arrested him for being a messenger for the Friends of Enlightenment revolutionary group. When he was released, Grigory (Rosenblum's assumed father) told him that his mother, Paulina, was dead, and that his true, biological father was her Jewish doctor, Mikhail A. Rosenblum. Re-naming himself Sigmund Rosenblum, he faked his death in Odessa Harbour and stowed away

According to Rosenblum, in 1892, the Imperial Russian Secret Police (Czarist Ochrana) arrested him for being a messenger for the Friends of Enlightenment revolutionary group. When he was released, Grigory (Rosenblum's assumed father) told him that his mother, Paulina, was dead, and that his true, biological father was her Jewish doctor, Mikhail A. Rosenblum. Re-naming himself Sigmund Rosenblum, he faked his death in Odessa Harbour and stowed away

aboard a British ship bound for South America

.

In Brazil

, young Sigmund adopted the name Pedro and worked odd jobs: dock worker, road mender, plantation labourer, and in 1895, cook for a British intelligence expedition. Allegedly, Rosenblum saved both the expedition and the life of Major Charles Fothergill when hostile natives attacked them. Rosenblum seized a British officer's pistol and, with expert, single-hand marksmanship, killed the attacking natives. Appropriately for a fantastic story, Major Fothergill rewarded Rosenblum with £1,500, a British passport

, and passage to Britain; there, Pedro became Sidney Rosenblum.

Evidence asserted in Andrew Cook's Ace of Spies: The True Story of Sidney Reilly (pg. 32) contradicts the aforementioned Brazilian scenario, and declares the British expedition incident to be unsubstantiated. Cook states that the arrival of Sigmund Rosenblum in London in December 1895 was via France

, and prompted by Rosenblum's unscrupulous acquisition of a large sum of money in Saint-Maur-des-Fossés

, a residential suburb of Paris

, necessitating a hasty flight. According to Cook's account, Rosenblum and Yan Voitek, a Russian accomplice, waylaid two Italian anarchists

on December 25, 1895, and robbed them of a substantial amount of revolutionary funds. One anarchist's throat was cut; the other, Constant Della Cassa, died from knife wounds in Fontainebleau Hospital three days later. By the time Della Cassa's death appeared in the newspapers, police had learned that one of the assailants, whose physical description matched Rosenblum's, was already en route to England. Rosenblum's accomplice, Voitek, would later relate this incident and his other dealings with Rosenblum to the British

Secret Intelligence Service

.

Regardless of whether Sigmund Rosenblum arrived in England via Brazil or France, he now resided at the Albert Mansions, a prestigious apartment block in Rosetta Street, Waterloo

, London

, in early 1896. Now settled in England, Rosenblum created the Ozone Preparations Company, which peddled miracle cures

. Because of his knowledge of languages, Rosenblum became a paid informant

for the émigré

intelligence network of William Melville

, superintendent of Scotland Yard's

Special Branch

and, according to Cook, later the clandestine head of the British

Secret Service Bureau, which was founded in 1909.

Rosenblum first met Thomas in London via his own Ozone Preparations Company. Thomas had a kidney inflammation and was intrigued by the miracle cures peddled by Rosenblum. Thomas introduced Rosenblum to his young wife at his Manor House

, and an affair developed between the two over the next six months.

On March 4, 1898, Thomas altered his will and appointed Margaret as an executor. A week after the making of the new will, Reverend Thomas and his nurse arrived at Newhaven Harbour Station. On March 12, 1898, in that same hotel, Reverend Thomas was found dead in his bed. A mysterious Dr. T.W. Andrew, who matched the physical description of Sigmund Rosenblum, appeared on the scene to certify Thomas' death as generic influenza

and, signing the relevant documents, proclaimed that there was no need for an inquest. Records indicate that no Dr. T.W. Andrew existed in Great Britain

circa 1897.

Margaret Callaghan insisted that Thomas' body be ready for burial a mere day and a half after his death. Six weeks later, Margaret inherited about £800,000. The Metropolitan Police did not investigate Dr. T.W. Andrew, nor did they investigate the nurse whom Margaret had hired, even though the nurse was previously linked to the arsenic poisoning of a former employer.

Four months later, on August 22, 1898, Rosenblum married Margaret Callaghan Thomas. The two witnesses at the ceremony were Charles Richard Cross and Joseph Bell. Bell was an Admiralty clerk, while Charles Cross was a government official. Both eventually married daughters of Henry Freeman Pannett, a close associate of William Melville. The marriage brought the wealth which Rosenblum desired, but provided a pretext to discard his identity of Sigmund Rosenblum, and, with the help of Melville, craft a new identity: Sidney George Reilly, husband of Margaret Thomas Reilly. This new identity was the key to achieving his desire to return to Czarist Russia and voyage to the Far East.

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

Sidney George Reilly, MC

Military Cross

The Military Cross is the third-level military decoration awarded to officers and other ranks of the British Armed Forces; and formerly also to officers of other Commonwealth countries....

(c.

Circa

Circa , usually abbreviated c. or ca. , means "approximately" in the English language, usually referring to a date...

March 24, 1873/1874 – November 5, 1925), famously known as the Ace of Spies, was a Jewish Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

n-born adventurer and secret agent

Secret Agent

Secret Agent is a British film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, loosely based on two stories in Ashenden: Or the British Agent by W. Somerset Maugham. The film starred John Gielgud, Peter Lorre, Madeleine Carroll, and Robert Young...

employed by Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard is a metonym for the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police Service of London, UK. It derives from the location of the original Metropolitan Police headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place, which had a rear entrance on a street called Great Scotland Yard. The Scotland Yard entrance became...

, the British

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

Secret Service Bureau and later the Secret Intelligence Service

Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service is responsible for supplying the British Government with foreign intelligence. Alongside the internal Security Service , the Government Communications Headquarters and the Defence Intelligence , it operates under the formal direction of the Joint Intelligence...

(SIS). He is alleged to have spied for at least four nations. His notoriety during the 1920s was created in part by his friend, British diplomat and journalist Sir Robert Bruce Lockhart, who sensationalised their thwarted operation to overthrow the Bolshevik government

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

in 1918.

After Reilly's death, the London Evening Standard published in May, 1931, a Master Spy serial glorifying his exploits. Later, Ian Fleming

Ian Fleming

Ian Lancaster Fleming was a British author, journalist and Naval Intelligence Officer.Fleming is best known for creating the fictional British spy James Bond and for a series of twelve novels and nine short stories about the character, one of the biggest-selling series of fictional books of...

would use Reilly as a model for

Inspirations for James Bond

A number of real-life inspirations have been suggested for James Bond, the sophisticated fictional character and British spy created by Ian Fleming. Although the Bond stories were often fantasy-driven, they did incorporate some real places, incidents and, occasionally, organisations such as...

James Bond

James Bond

James Bond, code name 007, is a fictional character created in 1953 by writer Ian Fleming, who featured him in twelve novels and two short story collections. There have been a six other authors who wrote authorised Bond novels or novelizations after Fleming's death in 1964: Kingsley Amis,...

. Today, many historians consider Reilly to be the first 20th century super-spy. Much of what is thought to be known about him could be false, as Reilly was a master of deception, and most of his life is shrouded in legend.

Origins and youth

The origins, identities, and activities of Sidney George Reilly have befuddled researchers and intelligence agencies for more than a century; hence, much of his purported life and many of his notorious exploits should be cautiously examined. Reilly himself told several versions of his origins to confuse and mislead investigators. Reilly claimed to be the son of (a) an Irish merchant seaman, (b) an Irish clergyman, and (c) an aristocratic landowner and habitué of the Imperial court of Tsar Alexander III of RussiaAlexander III of Russia

Alexander Alexandrovich Romanov , historically remembered as Alexander III or Alexander the Peacemaker reigned as Emperor of Russia from until his death on .-Disposition:...

.

Apparently, Reilly was born Georgi Rosenblum in Odessa

Odessa

Odessa or Odesa is the administrative center of the Odessa Oblast located in southern Ukraine. The city is a major seaport located on the northwest shore of the Black Sea and the fourth largest city in Ukraine with a population of 1,029,000 .The predecessor of Odessa, a small Tatar settlement,...

, then a Black Sea port of the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

(now Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

), on March 24, 1874 (Lockhart 1986); however, other theories of Reilly's birth place and origins exist. In Ace of Spies: The True Story of Sidney Reilly (pg. 28), author Andrew Cook states that Reilly was born on March 24, 1873, in the Jewish Kherson

Kherson

Kherson is a city in southern Ukraine. It is the administrative center of the Kherson Oblast , and is designated as its own separate raion within the oblast. Kherson is an important port on the Black Sea and Dnieper River, and the home of a major ship-building industry...

gubernia of Tsarist Russia, as Salomon (Shlomo) Rosenblum, and later that "Sidney Reilly" was the illegitimate son of Paulina (Perla), his acknowledged mother, and Dr. Mikhail Abramovich Rosenblum, the trusted first cousin of Reilly's putative father, Grigory (Hersh) Rosenblum. There is speculation that he was the son of a merchant marine captain and the above-mentioned mother.

Early life

Stowaway

A stowaway is a person who secretly boards a vehicle, such as an aircraft, bus, ship, cargo truck or train, to travel without paying and without being detected....

aboard a British ship bound for South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

.

In Brazil

Brazil

Brazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

, young Sigmund adopted the name Pedro and worked odd jobs: dock worker, road mender, plantation labourer, and in 1895, cook for a British intelligence expedition. Allegedly, Rosenblum saved both the expedition and the life of Major Charles Fothergill when hostile natives attacked them. Rosenblum seized a British officer's pistol and, with expert, single-hand marksmanship, killed the attacking natives. Appropriately for a fantastic story, Major Fothergill rewarded Rosenblum with £1,500, a British passport

Passport

A passport is a document, issued by a national government, which certifies, for the purpose of international travel, the identity and nationality of its holder. The elements of identity are name, date of birth, sex, and place of birth....

, and passage to Britain; there, Pedro became Sidney Rosenblum.

Evidence asserted in Andrew Cook's Ace of Spies: The True Story of Sidney Reilly (pg. 32) contradicts the aforementioned Brazilian scenario, and declares the British expedition incident to be unsubstantiated. Cook states that the arrival of Sigmund Rosenblum in London in December 1895 was via France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, and prompted by Rosenblum's unscrupulous acquisition of a large sum of money in Saint-Maur-des-Fossés

Saint-Maur-des-Fossés

Saint-Maur-des-Fossés is a commune in the southeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located 11.7 km. from the center of Paris.-The abbey:...

, a residential suburb of Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

, necessitating a hasty flight. According to Cook's account, Rosenblum and Yan Voitek, a Russian accomplice, waylaid two Italian anarchists

Anarchy

Anarchy , has more than one colloquial definition. In the United States, the term "anarchy" typically is meant to refer to a society which lacks publicly recognized government or violently enforced political authority...

on December 25, 1895, and robbed them of a substantial amount of revolutionary funds. One anarchist's throat was cut; the other, Constant Della Cassa, died from knife wounds in Fontainebleau Hospital three days later. By the time Della Cassa's death appeared in the newspapers, police had learned that one of the assailants, whose physical description matched Rosenblum's, was already en route to England. Rosenblum's accomplice, Voitek, would later relate this incident and his other dealings with Rosenblum to the British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

Secret Intelligence Service

Secret Intelligence Service

The Secret Intelligence Service is responsible for supplying the British Government with foreign intelligence. Alongside the internal Security Service , the Government Communications Headquarters and the Defence Intelligence , it operates under the formal direction of the Joint Intelligence...

.

Regardless of whether Sigmund Rosenblum arrived in England via Brazil or France, he now resided at the Albert Mansions, a prestigious apartment block in Rosetta Street, Waterloo

Lambeth

Lambeth is a district of south London, England, and part of the London Borough of Lambeth. It is situated southeast of Charing Cross.-Toponymy:...

, London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, in early 1896. Now settled in England, Rosenblum created the Ozone Preparations Company, which peddled miracle cures

Charlatan

A charlatan is a person practicing quackery or some similar confidence trick in order to obtain money, fame or other advantages via some form of pretense or deception....

. Because of his knowledge of languages, Rosenblum became a paid informant

Informant

An informant is a person who provides privileged information about a person or organization to an agency. The term is usually used within the law enforcement world, where they are officially known as confidential or criminal informants , and can often refer pejoratively to the supply of information...

for the émigré

Émigré

Émigré is a French term that literally refers to a person who has "migrated out", but often carries a connotation of politico-social self-exile....

intelligence network of William Melville

William Melville

William Melville was an Irish law enforcement officer and the first chief of the British Secret Service, forerunner of MI5.-Birth:...

, superintendent of Scotland Yard's

Scotland Yard

Scotland Yard is a metonym for the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police Service of London, UK. It derives from the location of the original Metropolitan Police headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place, which had a rear entrance on a street called Great Scotland Yard. The Scotland Yard entrance became...

Special Branch

Special Branch

Special Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security in British and Commonwealth police forces, as well as in the Royal Thai Police...

and, according to Cook, later the clandestine head of the British

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

Secret Service Bureau, which was founded in 1909.

In London: 1890s

In 1897, Sigmund Rosenblum was involved in the sudden and suspicious death of the elderly Reverend Hugh Thomas. It has been verified that Rosenblum had a torrid affair with Thomas' youthful wife, Margaret Callaghan, just prior to Thomas' demise.Rosenblum first met Thomas in London via his own Ozone Preparations Company. Thomas had a kidney inflammation and was intrigued by the miracle cures peddled by Rosenblum. Thomas introduced Rosenblum to his young wife at his Manor House

Manor house

A manor house is a country house that historically formed the administrative centre of a manor, the lowest unit of territorial organisation in the feudal system in Europe. The term is applied to country houses that belonged to the gentry and other grand stately homes...

, and an affair developed between the two over the next six months.

On March 4, 1898, Thomas altered his will and appointed Margaret as an executor. A week after the making of the new will, Reverend Thomas and his nurse arrived at Newhaven Harbour Station. On March 12, 1898, in that same hotel, Reverend Thomas was found dead in his bed. A mysterious Dr. T.W. Andrew, who matched the physical description of Sigmund Rosenblum, appeared on the scene to certify Thomas' death as generic influenza

Influenza

Influenza, commonly referred to as the flu, is an infectious disease caused by RNA viruses of the family Orthomyxoviridae , that affects birds and mammals...

and, signing the relevant documents, proclaimed that there was no need for an inquest. Records indicate that no Dr. T.W. Andrew existed in Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

circa 1897.

Margaret Callaghan insisted that Thomas' body be ready for burial a mere day and a half after his death. Six weeks later, Margaret inherited about £800,000. The Metropolitan Police did not investigate Dr. T.W. Andrew, nor did they investigate the nurse whom Margaret had hired, even though the nurse was previously linked to the arsenic poisoning of a former employer.

Four months later, on August 22, 1898, Rosenblum married Margaret Callaghan Thomas. The two witnesses at the ceremony were Charles Richard Cross and Joseph Bell. Bell was an Admiralty clerk, while Charles Cross was a government official. Both eventually married daughters of Henry Freeman Pannett, a close associate of William Melville. The marriage brought the wealth which Rosenblum desired, but provided a pretext to discard his identity of Sigmund Rosenblum, and, with the help of Melville, craft a new identity: Sidney George Reilly, husband of Margaret Thomas Reilly. This new identity was the key to achieving his desire to return to Czarist Russia and voyage to the Far East.

Tsarist Russia and the Far East

In June 1899, the newly-minted Sidney Reilly and his first wife Margaret Callaghan Thomas traveled to Czarist Russia using Reilly's new British passport—a cover identity purportedly created by William MelvilleWilliam MelvilleWilliam Melville was an Irish law enforcement officer and the first chief of the British Secret Service, forerunner of MI5.-Birth:...

. Margaret remained in St. Petersburg, while Reilly is alleged to have reconnoitred the CaucasusCaucasusThe Caucasus, also Caucas or Caucasia , is a geopolitical region at the border of Europe and Asia, and situated between the Black and the Caspian sea...

for its oil deposits and compiled a resource prospectus as part of "The Great GameThe Great GameThe Great Game or Tournament of Shadows in Russia, were terms for the strategic rivalry and conflict between the British Empire and the Russian Empire for supremacy in Central Asia. The classic Great Game period is generally regarded as running approximately from the Russo-Persian Treaty of 1813...

." He reported his findings to the British government who paid him for completing the assignment. In early 1901, Reilly and his wife voyaged from Port SaidPort SaidPort Said is a city that lies in north east Egypt extending about 30 km along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, north of the Suez Canal, with an approximate population of 603,787...

, EgyptEgyptEgypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, across the globe to the Far EastFar EastThe Far East is an English term mostly describing East Asia and Southeast Asia, with South Asia sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.The term came into use in European geopolitical discourse in the 19th century,...

.

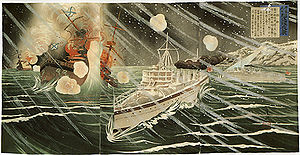

Shortly before the Russo-Japanese WarRusso-Japanese WarThe Russo-Japanese War was "the first great war of the 20th century." It grew out of rival imperial ambitions of the Russian Empire and Japanese Empire over Manchuria and Korea...

, Reilly appeared in Port ArthurLüshunkouLüshunkou is a district in the municipality of Dalian, Liaoning province, China. Also called Lüshun City or Lüshun Port, it was formerly known as both Port Arthur and Ryojun....

, ManchuriaManchuriaManchuria is a historical name given to a large geographic region in northeast Asia. Depending on the definition of its extent, Manchuria usually falls entirely within the People's Republic of China, or is sometimes divided between China and Russia. The region is commonly referred to as Northeast...

, as a double-agentDouble agentA double agent, commonly abbreviated referral of double secret agent, is a counterintelligence term used to designate an employee of a secret service or organization, whose primary aim is to spy on the target organization, but who in fact is a member of that same target organization oneself. They...

serving both the British and the Japanese interests. The Russian-controlled Port Arthur lay under the ever-darkening spectre of Japanese invasion, and Reilly and business partner Moisei (Moses) Akimovich Ginsburg turned the precarious situation to their financial benefit. They purchased enormous amounts of food, raw materials, medicine, and coal—and made a small fortune as war profiteers.

Reilly would have an even greater success in January 1904, when he and a ChineseHan ChineseHan Chinese are an ethnic group native to China and are the largest single ethnic group in the world.Han Chinese constitute about 92% of the population of the People's Republic of China , 98% of the population of the Republic of China , 78% of the population of Singapore, and about 20% of the...

engineerEngineerAn engineer is a professional practitioner of engineering, concerned with applying scientific knowledge, mathematics and ingenuity to develop solutions for technical problems. Engineers design materials, structures, machines and systems while considering the limitations imposed by practicality,...

acquaintance, Ho-Liang-Shung, allegedly stole the Port Arthur harbour defence plans for the Japanese NavyImperial Japanese NavyThe Imperial Japanese Navy was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1869 until 1947, when it was dissolved following Japan's constitutional renunciation of the use of force as a means of settling international disputes...

. Guided by these stolen plans, the Japanese Navy navigated through the Russian minefield protecting the harbour and launched a surprise attack on Port ArthurBattle of Port ArthurThe Battle of Port Arthur was the starting battle of the Russo-Japanese War...

. Yet the stolen plans did not help the Japanese much. More than 31,000 Russians ultimately perished defending Port Arthur, but Japanese losses were much higher, losses that nearly undermined their war effort.

Historian Winfried Ludecke suggests that, upon leaving Port ArthurLüshunkouLüshunkou is a district in the municipality of Dalian, Liaoning province, China. Also called Lüshun City or Lüshun Port, it was formerly known as both Port Arthur and Ryojun....

, Manchuria, Reilly voyaged to Imperial Japan in the company of an unknown mistress. If Reilly did visit Japan, presumably to receive espionage pay, he could not have stayed very long, for by June 1904 Reilly appeared in Paris, France. During the brief time that Reilly spent in Paris, he renewed his close acquaintance with William MelvilleWilliam MelvilleWilliam Melville was an Irish law enforcement officer and the first chief of the British Secret Service, forerunner of MI5.-Birth:...

, sometimes incorrectly described as the first Director General of MI5MI5The Security Service, commonly known as MI5 , is the United Kingdom's internal counter-intelligence and security agency and is part of its core intelligence machinery alongside the Secret Intelligence Service focused on foreign threats, Government Communications Headquarters and the Defence...

, whom Reilly had last seen in 1899 just prior to his departure from London. Reilly's meeting with Melville is most significant, for within a matter of weeks Melville was to use Reilly's expertise in what would later become known as The D'Arcy Affair.

D'Arcy affair

In 1904, the Board of the Admiralty projected that petroleumPetroleumPetroleum or crude oil is a naturally occurring, flammable liquid consisting of a complex mixture of hydrocarbons of various molecular weights and other liquid organic compounds, that are found in geologic formations beneath the Earth's surface. Petroleum is recovered mostly through oil drilling...

would supplant coal as the primary source of fuel for the Royal NavyRoyal NavyThe Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

. During their investigation, the British Admiralty learned that William Knox D'ArcyWilliam Knox D'ArcyWilliam Knox D'Arcy was one of the principal founders of the oil and petrochemical industry in Persia .-Early life:...

—who later founded the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) in April 1909—had obtained a valuable concessionConcession (contract)A concession is a business operated under a contract or license associated with a degree of exclusivity in business within a certain geographical area. For example, sports arenas or public parks may have concession stands. Many department stores contain numerous concessions operated by other...

from the Persian government regarding the oil rights in southern Persia and that D'Arcy was negotiating a similar concession from the Ottoman EmpireOttoman EmpireThe Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

for oil rights in MesopotamiaMesopotamiaMesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

. The British Admiralty purportedly initiated efforts to entice D'Arcy to sell his newly acquired oil rights to the British Government rather than to the French de RothschildsRothschild banking family of FranceThe Rothschild banking family of France was founded in 1812 in Paris by James Mayer Rothschild . James was sent there from his home in Frankfurt, Germany by his father, Mayer Amschel Rothschild...

(Lockhart, 1986).

In Reilly: Ace of Spies, Robin Bruce Lockhart repeats one of Reilly's oft-recited tales of how, at the British Admiralty's request, Reilly located William Knox D'Arcy in the south of FranceSouthern FranceSouthern France , colloquially known as le Midi is defined geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Gironde, Spain, the Mediterranean, and Italy...

and clandestinely approached him in disguise. According to Reilly, he boarded Lord de Rothschild's yacht attired as a Catholic priest and secretly persuaded D'Arcy to terminate negotiations with the French Rothschilds and return to London to meet with the British Admiralty. Biographer Andrew Cook is sceptical about Reilly's involvement in the D'Arcy Affair, for in February 1904, Reilly was purportedly still in Port Arthur, Manchuria. Cook further claims that it was Reilly's intelligence chief, William MelvilleWilliam MelvilleWilliam Melville was an Irish law enforcement officer and the first chief of the British Secret Service, forerunner of MI5.-Birth:...

, and a British intelligence officer, Henry Curtis Bennett, who undertook the D'Arcy assignment (Cook, 2004).

Although the extent of his involvement in the D'Arcy Affair is unknown, it has been verified that Reilly stayed in the French RivieraFrench RivieraThe Côte d'Azur, pronounced , often known in English as the French Riviera , is the Mediterranean coastline of the southeast corner of France, also including the sovereign state of Monaco...

on the Côte d'AzurProvence-Alpes-Côte d'AzurProvence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur or PACA is one of the 27 regions of France.It is made up of:* the former French province of Provence* the former papal territory of Avignon, known as Comtat Venaissin...

after the incident—a location very near the Rothschild yachtYachtA yacht is a recreational boat or ship. The term originated from the Dutch Jacht meaning "hunt". It was originally defined as a light fast sailing vessel used by the Dutch navy to pursue pirates and other transgressors around and into the shallow waters of the Low Countries...

. After conclusion of the D'Arcy Affair, Reilly journeyed to BrusselsBrusselsBrussels , officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region , is the capital of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union...

, and shortly thereafter, in January 1905, he arrived in St. Petersburg, RussiaRussiaRussia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, (Cook, 2004).

An alternative scenario put forward in The Prize by Daniel YerginDaniel YerginDaniel Howard Yergin is an American author, speaker, and economic researcher. Yergin is the co-founder and chairman of Cambridge Energy Research Associates, an energy research consultancy. It was acquired by IHS Inc...

has the Admiralty putting forward a "SyndicateSyndicateA syndicate is a self-organizing group of individuals, companies or entities formed to transact some specific business, or to promote a common interest or in the case of criminals, to engage in organized crime...

of Patriots" to keep D'Arcy's concession in British hands, apparently with the full and eager co-operation of D'Arcy himself.

Frankfurt International Air Show

In Ace of Spies, biographer Robin Bruce Lockhart recounts Reilly's alleged involvement in obtaining a newly developed German magnetoMagneto (electrical)A magneto is an electrical generator that uses permanent magnets to produce alternating current.Magnetos adapted to produce pulses of high voltage are used in the ignition systems of some gasoline-powered internal combustion engines to provide power to the spark plugs...

at the first Frankfurt International Air ShowAirshowAn air show is an event at which aviators display their flying skills and the capabilities of their aircraft to spectators in aerobatics. Air shows without aerobatic displays, having only aircraft displayed parked on the ground, are called "static air shows"....

("Internationale Luftschiffahrt-Ausstellung") in 1909.

According to Lockhart, on the fifth day of the air show a German plane lost control and crashed, killing the pilot. The plane's engine was alleged to have used a new type of magneto that was far ahead of other designs. Reilly and a BritishUnited Kingdom of Great Britain and IrelandThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

SISSecret Intelligence ServiceThe Secret Intelligence Service is responsible for supplying the British Government with foreign intelligence. Alongside the internal Security Service , the Government Communications Headquarters and the Defence Intelligence , it operates under the formal direction of the Joint Intelligence...

agentSecret AgentSecret Agent is a British film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, loosely based on two stories in Ashenden: Or the British Agent by W. Somerset Maugham. The film starred John Gielgud, Peter Lorre, Madeleine Carroll, and Robert Young...

posing as one of the exhibition pilots diverted public attention while they removed the magneto from the wreck and substituted another. The SIS agent quickly made detailed drawings of the German magneto, and when the engine had been removed to a hangar, the agent and Reilly managed to restore the original magneto (Lockhart, 1986).

Biographer Andrew Cook has countered that this incident never happened. According to documents about the air show, no plane crashes occurred during the event (Cook, 2004).

Stealing weapon plans

According to Lockhart, the German KaiserKaiserKaiser is the German title meaning "Emperor", with Kaiserin being the female equivalent, "Empress". Like the Russian Czar it is directly derived from the Latin Emperors' title of Caesar, which in turn is derived from the personal name of a branch of the gens Julia, to which Gaius Julius Caesar,...

was expanding the war machine of Imperial GermanyGerman EmpireThe German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

in 1909, and British intelligence had scant knowledge regarding the types of weapons being forged inside Germany's war plants. At the behest of British intelligence, Reilly was sent to obtain weapons plans (Lockhart 1967).

Reilly arrived in EssenEssen- Origin of the name :In German-speaking countries, the name of the city Essen often causes confusion as to its origins, because it is commonly known as the German infinitive of the verb for the act of eating, and/or the German noun for food. Although scholars still dispute the interpretation of...

, GermanyGermanyGermany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, in 1909 disguised as a BalticBaltic GermanThe Baltic Germans were mostly ethnically German inhabitants of the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, which today form the countries of Estonia and Latvia. The Baltic German population never made up more than 10% of the total. They formed the social, commercial, political and cultural élite in...

shipyardShipyardShipyards and dockyards are places which repair and build ships. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance and basing activities than shipyards, which are sometimes associated more with initial...

worker by the name of Karl Hahn. Having prepared his cover identity by learning weldingWeldingWelding is a fabrication or sculptural process that joins materials, usually metals or thermoplastics, by causing coalescence. This is often done by melting the workpieces and adding a filler material to form a pool of molten material that cools to become a strong joint, with pressure sometimes...

at a Sheffield engineering firm, Reilly obtained a low-level position as a welder at the Essen plant. Soon he joined the plant fire brigade and persuaded its foreman that a set of plant schematics were needed to indicate the position of fire extinguishers and hydrants. These schematics were soon lodged in the foreman's office for members of the fire brigade to consult, and Reilly set about using them to locate the weapon plans (Lockhart 1967).

In the early morning hours, Reilly used lock-picks to break into the office where the weapon plans were kept but was discovered by the foreman. Reilly strangled the foreman and completed the theft. From Essen, Reilly took a train to DortmundDortmundDortmund is a city in Germany. It is located in the Bundesland of North Rhine-Westphalia, in the Ruhr area. Its population of 585,045 makes it the 7th largest city in Germany and the 34th largest in the European Union....

to a safe houseSafe houseIn the jargon of law enforcement and intelligence agencies, a safe house is a secure location, suitable for hiding witnesses, agents or other persons perceived as being in danger...

, and tearing the plans into four pieces, mailed each separately. If one was lost, the other three would still reveal the gist of the plans (Lockhart 1967).

Cook casts doubt on this incident but concedes that German factory records show a Karl Hahn was indeed employed by the Essen plant during this time and a plant fire brigade was in formal operation.

World War I activity

One of Reilly's claims is that he was a secret agent behind German lines, and that he allegedly attended a German High Command conference {see below}; however, see Cook {Chapter 6}, which effectively debunks this by revealing Reilly's activities between 1915 and 1918 {reference only}. According to author Richard Spence in "Trust No One", Reilly lived in New York for at least a year, 1914–1915, where he engaged in arranging munitions sales to both the Germans and the Imperial Russian Army. This is confirmed by papers of Norman Thwaites, MI1c Head of Station in New York, wherein has been found evidence that Reilly approached Thwaites seeking a job in 1917–1918. Thwaites was reportedly impressed with Reilly, and wrote a letter of recommendation for him to Mansfield Cumming, head of MI1c. It was also Thwaites who recommended that Reilly first visit Toronto to obtain a military commission, which is why Reilly joined the Royal Canadian Flying Corps.

The fact that (by April 1917) the U.S. was now in the war and (by October) the Russians were out of the war made Reilly's munitions business far less profitable since his company would then have been prohibited from selling ammunition to the Germans and the Russians were no longer buying. Sometime during 1916–1918, Reilly reportedly received a commission in the Royal Canadian Flying Corps, and according to Spence, upon his return to London in 1918, Mansfield Cumming formally swore Lieutenant Reilly into service as a staff Case Officer in His Majesty's Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), prior to dispatching Reilly on counter-Bolshevik operations in Germany and Russia.

Ambassadors' plot

The endeavour to depose the Bolshevik Government and assassinate Vladimir Ilyich Lenin is considered by biographers to be Reilly's most daring scheme. The Lockhart Plot, or more accurately the Reilly Plot, has sparked debate over the years: Did the Allies launch a clandestine operation to overthrow the Bolsheviks? If so, did the ChekaChekaCheka was the first of a succession of Soviet state security organizations. It was created by a decree issued on December 20, 1917, by Vladimir Lenin and subsequently led by aristocrat-turned-communist Felix Dzerzhinsky...

uncover the plot at the eleventh hour or had they unmasked the conspirators from the outset? Some historians have suggested that the Cheka orchestrated the conspiracy from beginning to end and possibly that Reilly was a Bolshevik agent provocateurAgent provocateurTraditionally, an agent provocateur is a person employed by the police or other entity to act undercover to entice or provoke another person to commit an illegal act...

.

In May 1918, Robert Bruce Lockhart (BBC 2011), an agent of the British Secret Intelligence Service, and Reilly repeatedly met with Boris SavinkovBoris SavinkovBoris Viktorovich Savinkov was a Russian writer and revolutionary terrorist...

, the head of the counter-revolutionary Union for the Defence of the Fatherland and Freedom (UDFF). Savinkov had been Deputy War Minister in the Provisional GovernmentRussian Provisional GovernmentThe Russian Provisional Government was the short-lived administrative body which sought to govern Russia immediately following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II . On September 14, the State Duma of the Russian Empire was officially dissolved by the newly created Directorate, and the country was...

of Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky, and a key opponent of the BolshevikBolshevikThe Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

s. A former Social Revolutionary Party member, Savinkov had formed the UDFF consisting of several thousand Russian fighters. Lockhart and Reilly then contacted anti-BolshevikWhite movementThe White movement and its military arm the White Army - known as the White Guard or the Whites - was a loose confederation of Anti-Communist forces.The movement comprised one of the politico-military Russian forces who fought...

collectives linked to Savinkov and supported these factions with SIS funds. They also liaised with the intelligence operatives of the French and U.S. consuls in MoscowMoscowMoscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

.

In June, disillusioned members of the Latvian RiflemenLatvian RiflemenThis article is about Latvian military formations in World War I and Russian Civil War. For Red Army military formations in World War II see Latvian Riflemen Soviet Divisions....

began appearing in anti-Bolshevik circles in Petrograd and were eventually directed to Captain Cromie, a British naval attaché, and Mr. Constantine, a Turkish merchant who was actually Reilly. As Latvians were deemed the Praetorian GuardPraetorian GuardThe Praetorian Guard was a force of bodyguards used by Roman Emperors. The title was already used during the Roman Republic for the guards of Roman generals, at least since the rise to prominence of the Scipio family around 275 BC...

of the Bolsheviks and entrusted with the security of the KremlinKremlinA kremlin , same root as in kremen is a major fortified central complex found in historic Russian cities. This word is often used to refer to the best-known one, the Moscow Kremlin, or metonymically to the government that is based there...

, Reilly believed their participation in the pending coup to be vital and arranged their meeting with Lockhart at the British mission in Moscow. At this stage, Reilly planned a coup against the Bolshevik government and drew up a list of Soviet military leaders ready to assume responsibilities on the fall of the Bolshevik government. While the coup was prepared, an Allied forceAllied Intervention in the Russian Civil WarThe Allied intervention was a multi-national military expedition launched in 1918 during World War I which continued into the Russian Civil War. Its operations included forces from 14 nations and were conducted over a vast territory...

landed on August 4, 1918, at ArkhangelskArkhangelskArkhangelsk , formerly known as Archangel in English, is a city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina River near its exit into the White Sea in the north of European Russia. The city spreads for over along the banks of the river...

, RussiaRussiaRussia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, beginning a famous military expedition dubbed Operation Archangel. Its objective was to prevent the German Empire from obtaining Allied military supplies stored in the region. In retaliation for this incursion, the Bolsheviks raided the British diplomatic missionDiplomatic missionA diplomatic mission is a group of people from one state or an international inter-governmental organisation present in another state to represent the sending state/organisation in the receiving state...

on August 5, disrupting a meeting Reilly had arranged between the anti-Bolshevik Latvians, UDFF officials, and Lockhart.

On August 17, Reilly conducted meetings between Latvian regimental leaders and liaised with Captain George Hill, another British agent operating in Russia. They agreed the coup would occur the first week of September during a meeting of the Council of People's Commissars and the Moscow Soviet at the Bolshoi TheatreBolshoi TheatreThe Bolshoi Theatre is a historic theatre in Moscow, Russia, designed by architect Joseph Bové, which holds performances of ballet and opera. The Bolshoi Ballet and Bolshoi Opera are amongst the oldest and most renowned ballet and opera companies in the world...

. However, on the eve of the coup, unexpected events thwarted the operation.

On August 30, a military cadet shot and killed Moisei UritskyMoisei UritskyMoisei Solomonovich Uritsky was a Bolshevik revolutionary leader in Russia.He was born in the city of Cherkasy, Kiev Governorate, to a Jewish family. His father, a merchant, died when Moisei was little and his mother raised her son by herself.Moisei studied law at the University of Kiev...

, head of the Petrograd ChekaChekaCheka was the first of a succession of Soviet state security organizations. It was created by a decree issued on December 20, 1917, by Vladimir Lenin and subsequently led by aristocrat-turned-communist Felix Dzerzhinsky...

. On this same day, Fanya Kaplan, a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, shot and wounded Lenin as he left a meeting at the Michelson factory in Moscow. These events were used by the Cheka to implicate any malcontents in a grand conspiracy that warranted a full-scale campaign: the "Red TerrorRed TerrorThe Red Terror in Soviet Russia was the campaign of mass arrests and executions conducted by the Bolshevik government. In Soviet historiography, the Red Terror is described as having been officially announced on September 2, 1918 by Yakov Sverdlov and ended about October 1918...

." Thousands of political opponents were seized and executed. Using lists supplied by undercover agents, the Cheka arrested those involved in Reilly's pending coup. They raided the British Embassy in Petrograd and killed Cromie, Reilly's accomplice, who put up an armed resistance. Lockhart was arrested, but later released in exchange for LitvinovMaxim LitvinovMaxim Maximovich Litvinov was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet diplomat.- Early life and first exile :...

, a diplomatDiplomatA diplomat is a person appointed by a state to conduct diplomacy with another state or international organization. The main functions of diplomats revolve around the representation and protection of the interests and nationals of the sending state, as well as the promotion of information and...

who had been arrested in London in a reprisal. Elizaveta Otten, Reilly's chief courier, was arrested as well as his other mistress Olga Starzheskaya. Another courier, Maria Fride, with papers she carried for Reilly, was arrested at Otten's flat.

On September 3, the aborted coup was sensationalised by the Russian press. Reilly was identified as a leader, and a dragnet ensued. The Cheka raided his assumed refuge, but Reilly avoided capture and met with Captain Hill. Hill proposed that Reilly escape Russia via Ukraine using their network of British agents for safe houses and assistance. Reilly instead chose a shorter, more dangerous route north to FinlandFinlandFinland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

. With the Cheka closing in, Reilly, carrying a Baltic GermanBaltic GermanThe Baltic Germans were mostly ethnically German inhabitants of the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, which today form the countries of Estonia and Latvia. The Baltic German population never made up more than 10% of the total. They formed the social, commercial, political and cultural élite in...

passport, posed as a legation secretary and departed Moscow in a railway car reserved for the German Embassy. In KronstadtKronstadtKronstadt , also spelled Kronshtadt, Cronstadt |crown]]" and Stadt for "city"); is a municipal town in Kronshtadtsky District of the federal city of St. Petersburg, Russia, located on Kotlin Island, west of Saint Petersburg proper near the head of the Gulf of Finland. Population: It is also...

, Reilly sailed by ship to HelsinkiHelsinkiHelsinki is the capital and largest city in Finland. It is in the region of Uusimaa, located in southern Finland, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, an arm of the Baltic Sea. The population of the city of Helsinki is , making it by far the most populous municipality in Finland. Helsinki is...

and reached StockholmStockholmStockholm is the capital and the largest city of Sweden and constitutes the most populated urban area in Scandinavia. Stockholm is the most populous city in Sweden, with a population of 851,155 in the municipality , 1.37 million in the urban area , and around 2.1 million in the metropolitan area...

. He arrived in LondonLondonLondon is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

on November 8.

The day before Reilly and Hill met with Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming ("C") in London for their debriefing, the Russian IzvestiaIzvestiaIzvestia is a long-running high-circulation daily newspaper in Russia. The word "izvestiya" in Russian means "delivered messages", derived from the verb izveshchat . In the context of newspapers it is usually translated as "news" or "reports".-Origin:The newspaper began as the News of the...

newspaper reported that both Reilly and Lockhart had been sentenced to death in absentiaIn absentiaIn absentia is Latin for "in the absence". In legal use, it usually means a trial at which the defendant is not physically present. The phrase is not ordinarily a mere observation, but suggests recognition of violation to a defendant's right to be present in court proceedings in a criminal trial.In...

by a Revolutionary TribunalRevolutionary TribunalThe Revolutionary Tribunal was a court which was instituted in Paris by the Convention during the French Revolution for the trial of political offenders, and eventually became one of the most powerful engines of the Reign of Terror....

for their roles in the attempted coup of the Bolshevik government. Their sentence was to be carried out immediately should either of them be apprehended on Soviet soil. This sentence would later be served on Reilly when he was caught by the OGPU in 1925. Yet, within the week of their debriefing, the BritishUnited KingdomThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

Secret Intelligence ServiceSecret Intelligence ServiceThe Secret Intelligence Service is responsible for supplying the British Government with foreign intelligence. Alongside the internal Security Service , the Government Communications Headquarters and the Defence Intelligence , it operates under the formal direction of the Joint Intelligence...

and the Foreign Office again sent Reilly and Hill to Russia under the cover of British trade delegates. Their assignment was to uncover information about the Black SeaBlack SeaThe Black Sea is bounded by Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus and is ultimately connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the Mediterranean and the Aegean seas and various straits. The Bosphorus strait connects it to the Sea of Marmara, and the strait of the Dardanelles connects that sea to the Aegean...

coast needed for the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.

Career with British intelligence

Throughout his life, Sidney Reilly maintained a close yet tempestuous relationship with the British intelligence community.

In 1896, Reilly was recruited by Superintendent William Melville for the émigréÉmigréÉmigré is a French term that literally refers to a person who has "migrated out", but often carries a connotation of politico-social self-exile....

intelligenceIntelligenceIntelligence has been defined in different ways, including the abilities for abstract thought, understanding, communication, reasoning, learning, planning, emotional intelligence and problem solving....

network of Scotland YardScotland YardScotland Yard is a metonym for the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police Service of London, UK. It derives from the location of the original Metropolitan Police headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place, which had a rear entrance on a street called Great Scotland Yard. The Scotland Yard entrance became...

's Special BranchSpecial BranchSpecial Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security in British and Commonwealth police forces, as well as in the Royal Thai Police...

. Through his close relationship with Melville, Reilly would be employed as a secret agentSecret AgentSecret Agent is a British film directed by Alfred Hitchcock, loosely based on two stories in Ashenden: Or the British Agent by W. Somerset Maugham. The film starred John Gielgud, Peter Lorre, Madeleine Carroll, and Robert Young...

for the Secret Service Bureau, which the War OfficeWar OfficeThe War Office was a department of the British Government, responsible for the administration of the British Army between the 17th century and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the Ministry of Defence...

created in October 1909.

In 1918, Reilly began to work for MI1(c), an early designation for the BritishUnited KingdomThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

Secret Intelligence ServiceSecret Intelligence ServiceThe Secret Intelligence Service is responsible for supplying the British Government with foreign intelligence. Alongside the internal Security Service , the Government Communications Headquarters and the Defence Intelligence , it operates under the formal direction of the Joint Intelligence...

, under Sir Mansfield Smith-Cumming. Reilly was allegedly trained by the latter organization and sent to MoscowMoscowMoscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

in March 1918 to assassinate Vladimir Ilyich Lenin or attempt to overthrow the Bolsheviks. He had to escape after the ChekaChekaCheka was the first of a succession of Soviet state security organizations. It was created by a decree issued on December 20, 1917, by Vladimir Lenin and subsequently led by aristocrat-turned-communist Felix Dzerzhinsky...

unravelled the so-called Lockhart Plot against the Bolshevik government.

Reilly told various tales about his espionage deeds and adventurous exploits. According to Reilly, he earned and lost several fortunes in his lifetime and had many wives and mistresses. He claimed that:

- In the Second Boer WarSecond Boer WarThe Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

he disguised himself as a Russian arms merchantArms industryThe arms industry is a global industry and business which manufactures and sells weapons and military technology and equipment. It comprises government and commercial industry involved in research, development, production, and service of military material, equipment and facilities...

to spy on DutchNetherlandsThe Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

weapons shipments to the Boers. - He procured Persian oil concessions for the British Admiralty, the so-called D'Arcy AffairWilliam Knox D'ArcyWilliam Knox D'Arcy was one of the principal founders of the oil and petrochemical industry in Persia .-Early life:...

. - In the disguise of a timber company owner, he gathered information on the Russian military presence in Port ArthurLüshunkouLüshunkou is a district in the municipality of Dalian, Liaoning province, China. Also called Lüshun City or Lüshun Port, it was formerly known as both Port Arthur and Ryojun....

, Manchuria, and reported to the KempeitaiKempeitaiThe was the military police arm of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1881 to 1945. It was not an English-style military police, but a French-style gendarmerie...

, the JapanJapanJapan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

ese secret policeSecret policeSecret police are a police agency which operates in secrecy and beyond the law to protect the political power of an individual dictator or an authoritarian political regime....

. - He spied on the KruppKruppThe Krupp family , a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty from Essen, have become famous for their steel production and for their manufacture of ammunition and armaments. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG Hoesch-Krupp, was the largest company in Europe at the beginning of the 20th...

armaments plant in GermanyGermanyGermany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

. - He volunteered for the Royal Flying CorpsRoyal Flying CorpsThe Royal Flying Corps was the over-land air arm of the British military during most of the First World War. During the early part of the war, the RFC's responsibilities were centred on support of the British Army, via artillery co-operation and photographic reconnaissance...

in CanadaCanadaCanada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

at the start of World War IWorld War IWorld War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. - He seduced the wife of a Russian minister to obtain information about German weapons shipments to Russia.

- During World War I, he donned a German officer's uniform and attended a German Army High Command meeting.

- He saved British diplomats in Brazil.

- He attempted, but failed, to engineer the downfall of the Russian BolshevikBolshevikThe Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

government.

British intelligence adhered to its policy of publicly saying nothing about anything. Yet Reilly's espionage successes did garner indirect recognition.

After a formal recommendation by Sir Mansfield "C" Smith-Cumming, Reilly, who had been commissioned into the Royal Flying CorpsRoyal Flying CorpsThe Royal Flying Corps was the over-land air arm of the British military during most of the First World War. During the early part of the war, the RFC's responsibilities were centred on support of the British Army, via artillery co-operation and photographic reconnaissance...

in 1917, was awarded the Military CrossMilitary CrossThe Military Cross is the third-level military decoration awarded to officers and other ranks of the British Armed Forces; and formerly also to officers of other Commonwealth countries....

on January 22, 1919, "for distinguished services rendered in connection with military operations in the field." Cook claims the medal was bestowed due to Reilly's anti-Bolshevik operations in southern Russia, but espionage historian Richard DeaconDonald McCormickGeorge Donald King McCormick was a British journalist and popular historian, who also wrote under the pseudonyms Richard Deacon and Lichade Digen....

states the award was given for Reilly's clandestine activities in World War IWorld War IWorld War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. Reilly had allegedly parachuted behind German lines on a number of occasions. Once, disguised as a German officer, he spent three weeks inside the German EmpireGerman EmpireThe German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

(Deutsches ReichDeutsches ReichDeutsches Reich was the official name for Germany from 1871 to 1945 in the German language.As the literal English translation "German Empire" denotes a monarchy, the term is used only in reference to Germany prior to the fall of the monarchies at the end of World War I in 1918...

) gathering information about the next planned thrust against the AlliesAllies of World War IThe Entente Powers were the countries at war with the Central Powers during World War I. The members of the Triple Entente were the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire; Italy entered the war on their side in 1915...

.

Deacon asserts in History of the Russian Secret Service that in April 1912, Reilly was an Ochrana agent with the task of befriending and profiling Sir Basil Zaharoff, the international arms salesman and representative of Vickers-Armstrong Munitions LtdVickersVickers was a famous name in British engineering that existed through many companies from 1828 until 1999.-Early history:Vickers was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by the miller Edward Vickers and his father-in-law George Naylor in 1828. Naylor was a partner in the foundry Naylor &...

. Another Reilly biographer, Richard B. Spence, claims in Trust No One: The Secret World Of Sidney Reilly that during this assignment Reilly learned "le systeme" from Zaharoff. To Zaharoff, "le systeme" was the strategy of playing all sides against each other in order to maximise financial profit.

Cook counters in Ace of Spies: The True Story of Sidney Reilly (pg. 104) that there is no evidence of any relationship between Reilly and Zaharoff. According to Cook, Reilly was more of a con artistConfidence trickA confidence trick is an attempt to defraud a person or group by gaining their confidence. A confidence artist is an individual working alone or in concert with others who exploits characteristics of the human psyche such as dishonesty and honesty, vanity, compassion, credulity, irresponsibility,...

. Reilly claimed to have been employed by the BritishUnited KingdomThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

Secret Intelligence ServiceSecret Intelligence ServiceThe Secret Intelligence Service is responsible for supplying the British Government with foreign intelligence. Alongside the internal Security Service , the Government Communications Headquarters and the Defence Intelligence , it operates under the formal direction of the Joint Intelligence...

since the 1890s, but he did not volunteer his services nor was he accepted as an agent until March 15, 1918, and was effectively fired in 1921 because of his tendency to be a rogue operative. Nevertheless, Reilly had been a renowned operative for Scotland Yard'sScotland YardScotland Yard is a metonym for the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police Service of London, UK. It derives from the location of the original Metropolitan Police headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place, which had a rear entrance on a street called Great Scotland Yard. The Scotland Yard entrance became...

Special BranchSpecial BranchSpecial Branch is a label customarily used to identify units responsible for matters of national security in British and Commonwealth police forces, as well as in the Royal Thai Police...

and the Secret Service Bureau, which were the early forerunners of the British intelligence community.

On May 18, 1923 formerly Pepita Bobadilla, actress, widow of Haddon Chambers, dramatist, married Sidney Reilly at the Registrar Office in Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, Captain Hill acting as witness.

Author Michael Kettle has claimed in Sidney Reilly: The True Story of the World's Greatest Spy (pg. 121) that despite having been fired by SIS, Reilly possibly was involved with Sir Stewart Graham MenziesStewart MenziesMajor General Sir Stewart Graham Menzies, KCB, KCMG, DSO, MC was Chief of MI6 , British Secret Intelligence Service, during and after World War II.-Early life, family:...

in the forging of the The Zinoviev LetterZinoviev LetterThe "Zinoviev Letter" refers to a controversial document published by the British press in 1924, allegedly sent from the Communist International in Moscow to the Communist Party of Great Britain...

in 1924.

Death

In September 1925, undercover agents of the OGPU, the intelligence successor of the Cheka ChekaCheka was the first of a succession of Soviet state security organizations. It was created by a decree issued on December 20, 1917, by Vladimir Lenin and subsequently led by aristocrat-turned-communist Felix Dzerzhinsky...

ChekaCheka was the first of a succession of Soviet state security organizations. It was created by a decree issued on December 20, 1917, by Vladimir Lenin and subsequently led by aristocrat-turned-communist Felix Dzerzhinsky...

, lured Reilly to BolshevikBolshevikThe Bolsheviks, originally also Bolshevists , derived from bol'shinstvo, "majority") were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party which split apart from the Menshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903....

RussiaRussiaRussia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, ostensibly to meet the supposed anti-Communist organization The Trust—in reality, an OGPU deception existing under the code name Operation TrustTrust OperationOperation Trust was a counterintelligence operation of the State Political Directorate of the Soviet Union. The operation, which ran from 1921-1926, set up a fake anti-Bolshevik underground organization, "Monarchist Union of Central Russia", MUCR , in order to help the OGPU identify real...

. At the Russian border, Reilly was introduced to undercover OGPU agents posing as senior Trust representatives from Moscow. One of these undercover Soviet agents, Alexander Yakushev, later recalled the meeting:

After Reilly crossed the FinnishFinlandFinland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

border, the Soviets captured, transported, and interrogated him at Lubyanka Prison. On arrival, Reilly was taken to the office of Roman Pilar, a Soviet official who the previous year had arrested and ordered the execution of Boris SavinkovBoris SavinkovBoris Viktorovich Savinkov was a Russian writer and revolutionary terrorist...

, a close friend of Reilly. Pilar reminded Reilly that he had been sentenced to death by a 1918 Soviet tribunal for his participation in a counter-revolutionary plot against the Bolshevik government. While Reilly was being interrogated, the Soviets publicly claimed that he had been shot trying to cross the Finnish border.

Historians debate whether Reilly was tortured while in OGPU custody. Cook contends that Reilly was not tortured other than psychologically by mock execution scenarios designed to shake the resolve of prisoners. During OGPU interrogation, Reilly maintained his charade of being a British subject born in ClonmelClonmelClonmel is the county town of South Tipperary in Ireland. It is the largest town in the county. While the borough had a population of 15,482 in 2006, another 17,008 people were in the rural hinterland. The town is noted in Irish history for its resistance to the Cromwellian army which sacked both...

, IrelandIrelandIreland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

, and would not reveal any intelligence matters. While facing such daily interrogation, Reilly kept a diary in his cell of tiny handwritten notes on cigarette papers which he hid in the plasterwork of a cell wall. While his Soviet captors were interrogating Reilly, Reilly in turn was analysing and documenting their techniques. The diary was a detailed record of OGPU interrogation techniques, and Reilly was understandably confident that such unique documentation would, if he escaped, be of interest to the British SIS. After Reilly's death, Soviet guards discovered the diary in Reilly's cell, and photographic enhancements were made by OGPU technicians.

Reilly was executed in a forest near Moscow on November 5, 1925; British intelligence documents released in 2000 confirm this. According to eyewitness Boris GudzBoris GudzBoris Gudz was the last survivor of the October Revolution, veteran of the Russian Civil War and OGPU security agent member.-Biography:...

, the execution of Sidney Reilly was supervised by an OGPU officer, Grigory Feduleev; another OGPU officer, George Syroezhkin, fired the final shot into Reilly's chest.

After the death of Reilly, there were various rumors about his survival. Some, for example, speculated that Reilly had defected and became an adviser to Soviet intelligence.

Ace of Spies

In 1983, a television TelevisionTelevision is a telecommunication medium for transmitting and receiving moving images that can be monochrome or colored, with accompanying sound...

TelevisionTelevision is a telecommunication medium for transmitting and receiving moving images that can be monochrome or colored, with accompanying sound...

mini-series, Reilly, Ace of SpiesReilly, Ace of SpiesReilly, Ace of Spies is a 1983 television miniseries dramatizing the life of Sidney Reilly, a Russian Jew who became one of the greatest spies to ever work for the British. Among his exploits in the early 20th century were the infiltration of the German General Staff in 1917 and a near-overthrow of...

, dramatised the historical adventures of Reilly. The programme won the 1984 BAFTA TV Award. Reilly was portrayed by actor Sam NeillSam NeillNigel John Dermot "Sam" Neill, DCNZM, OBE is a New Zealand actor. He is well known for his starring role as paleontologist Dr Alan Grant in Jurassic Park and Jurassic Park III....

. Leo McKernLeo McKernReginald "Leo" McKern, AO was an Australian-born British actor who appeared in numerous British and Australian television programmes and movies, and more than 200 stage roles.-Early life:...

portrayed Sir Basil ZaharoffBasil ZaharoffBasil Zaharoff, GCB, GBE , born Zacharias Basileios Zacharoff, was an arms dealer and financier...

. The series was based on Robin Bruce Lockhart's book, Ace of Spies, which was adapted by Troy Kennedy MartinTroy Kennedy MartinTroy Kennedy Martin was a Scottish-born film and television screenwriter best known for creating the long running BBC TV police series Z-Cars, and for the award-winning 1985 anti-nuclear drama Edge of Darkness...

.

James Bond