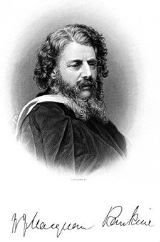

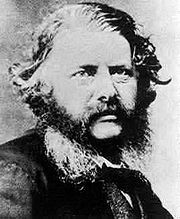

William John Macquorn Rankine

Encyclopedia

William John Macquorn Rankine (5 July 1820 – 24 December 1872) was a Scottish civil engineer

, physicist and mathematician. He was a founding contributor, with Rudolf Clausius

and William Thomson

(1st Baron Kelvin), to the science of thermodynamics

.

Rankine developed a complete theory of the steam engine

and indeed of all heat engines. His manuals of engineering science and practice were used for many decades after their publication in the 1850s and 1860s. He published several hundred papers and notes on science and engineering topics, from 1840 onwards, and his interests were extremely varied, including, in his youth, botany

, music theory

and number theory

, and, in his mature years, most major branches of science, mathematics and engineering. He was an enthusiastic amateur singer, pianist and cellist who composed his own humorous songs. He was born in Edinburgh

and died in Glasgow

, a bachelor.

to British Army

lieutenant

David Rankine and Barbara Grahame, of a prominent legal and banking family. Rankine was initially educated at home but he later attended Ayr Academy

(1828-9) and, very briefly, the High School of Glasgow

(1830). Around 1830 the family moved to Edinburgh; in 1834 he studied at a Military and Naval Academy with the mathematician George Lees; by that year he was already highly proficient in mathematics and received, as a gift from his uncle, Newton's Principia (1687) in the original Latin.

In 1836 Rankine began to study a spectrum of scientific topics at the University of Edinburgh

, including natural history

under Robert Jameson

and natural philosophy

under James David Forbes. Under Forbes he was awarded prizes for essays on methods of physical inquiry and on the undulatory (or wave) theory of light. During vacations, he assisted his father who, from 1830, was manager and, later, effective treasurer and engineer of the Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway

which brought coal into the growing city. He left the University of Edinburgh in 1838 without a degree (which was not then unusual) and, perhaps because of straitened family finances, became an apprentice to Sir John Benjamin Macneill

, who was at the time surveyor to the Irish Railway Commission. During his pupilage he developed a technique, later known as Rankine's method

, for laying out railway curves, fully exploiting the theodolite

and making a substantial improvement in accuracy

and productivity over existing methods. In fact, the technique was simultaneously in use by other engineers – and in the 1860s there was a minor dispute about Rankine's priority.

The year 1842 also marked Rankine's first attempt to reduce the phenomena of heat

to a mathematical

form but he was frustrated by his lack of experimental data. At the time of Queen Victoria's visit to Scotland, he organised a large bonfire

situated on Arthur's Seat

, constructed with radiating air passages under the fuel. The bonfire served as a beacon to initiate a chain of other bonfires across Scotland.

. Though his theory of circulating streams of elastic vortices whose volumes spontaneously adapted to their environment sounds fanciful to scientists formed on a modern account, by 1849, he had succeeded in finding the relationship between saturated vapour pressure and temperature

. The following year, he used his theory to establish relationships between the temperature, pressure

and density

of gas

es, and expressions for the latent heat

of evaporation

of a liquid

. He accurately predicted the surprising fact that the apparent specific heat of saturated

steam

would be negative.

Emboldened by his success, he set out to calculate the efficiency of heat engines and used his theory as a basis to deduce the principle, that the maximum efficiency of a heat engine is a function only of the two temperatures between which it operates. Though a similar result had already been derived by Rudolf Clausius

and William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin

, Rankine claimed that his result rested upon his hypothesis of molecular vortices alone, rather than upon Carnot's theory or some other additional assumption. The work marked the first step on Rankine's journey to develop a more complete theory of heat.

Rankine later recast the results of his molecular theories in terms of a macroscopic account of energy

and its transformations. He defined and distinguished between actual energy which was lost in dynamic processes and potential energy by which it was replaced. He assumed the sum of the two energies to be constant, an idea already, although surely not for very long, familiar in the law of conservation of energy

. From 1854, he made wide use of his thermodynamic function which he later realised was identical to the entropy

of Clausius. By 1855, Rankine had formulated a science of energetics

which gave an account of dynamics in terms of energy and its transformations rather than force

and motion

. The theory was very influential in the 1890s. In 1859 he proposed the Rankine scale of temperature, an absolute or thermodynamic scale whose degree is equal to a Fahrenheit

degree.

Energetics offered Rankine an alternative, and rather more mainstream, approach, to his science and, from the mid 1850s, he made rather less use of his molecular vortices. Yet he still claimed that Maxwell's work on electromagnetics was effectively an extension of his model. And, in 1864, he contended that the microscopic theories of heat proposed by Clausius and James Clerk Maxwell

, based on linear atomic motion, were inadequate. It was only in 1869 that Rankine admitted the success of these rival theories. By that time, his own model of the atom had become almost identical with that of Thomson.

As was his constant aim, especially as a teacher of engineering, he used his own theories to develop a number of practical results and to elucidate their physical principles including:

The history of rotordynamics

is replete with the interplay of theory and practice. Rankine first performed an analysis of a spinning shaft in 1869, but his model was not adequate and he predicted that supercritical speeds could not be attained.

Rankine was one of the first engineers to recognise that fatigue

Rankine was one of the first engineers to recognise that fatigue

failures of railway axles was caused by the initiation and growth of brittle cracks. In the early 1840s he examined many broken axles, especially after the Versailles train crash

of 1842 when a locomotive axle suddenly fractured and led to the death of over 50 passengers. He showed that the axles had failed by progressive growth of a brittle crack from a shoulder or other stress concentration

source on the shaft, such as a keyway

. He was supported by similar direct analysis of failed axles by Joseph Glynn

, where the axles failed by slow growth of a brittle crack in a process now known as metal fatigue

. It was likely that the front axle of one of the locomotives involved in the Versailles train crash

failed in a similar way. Rankine presented his conclusions in a paper delivered to the Institution of Civil Engineers. His work was ignored however, by many engineers who persisted in believing that stress could cause "re-crystallisation" of the metal, a myth which has persisted even to recent times. The theory of recrystallisation was quite wrong, and inhibited worthwhile research until the work of William Fairbairn

a few years later, which showed the weakening effect of repeated flexure on large beams. Nevertheless, fatigue remained a serious and poorly understood phenomenon, and was the root cause of many accidents on the railways and elsewhere. It is still a serious problem, but at least is much better understood today, and so can be prevented by careful design.

of civil engineering and mechanics at the University of Glasgow

from November 1855 until his death in December 1872, pursuing engineering research along a number of lines in civil and mechanical engineering

.

Rankine was instrumental in the formation of the forerunner of Glasgow University Officer Training Corps

, the 2nd Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteer Corps at Glasgow University in July 1859, becoming Major in 1860 after it was formed into the first company of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteer Corps; he served until 1864, when he resigned due to pressure of work - much of it associated with Naval Architecture.

s are named in recognition of the significant contributions he made to:

, to make naval architecture into an engineering science. He was a founding member, and first President of the Institution of Engineers & Shipbuilders in Scotland in 1857. He was an early member of the Royal Institute of Naval Architects (founded 1860) and attended many of its annual meetings. With William Thomson and others, Rankine was a member of the board of enquiry into the controversial sinking of the HMS Captain

.

Books

Books

Papers

About Rankine

Civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering; the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructures while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing infrastructures that have been neglected.Originally, a...

, physicist and mathematician. He was a founding contributor, with Rudolf Clausius

Rudolf Clausius

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius , was a German physicist and mathematician and is considered one of the central founders of the science of thermodynamics. By his restatement of Sadi Carnot's principle known as the Carnot cycle, he put the theory of heat on a truer and sounder basis...

and William Thomson

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin OM, GCVO, PC, PRS, PRSE, was a mathematical physicist and engineer. At the University of Glasgow he did important work in the mathematical analysis of electricity and formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics, and did much to unify the emerging...

(1st Baron Kelvin), to the science of thermodynamics

Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics is a physical science that studies the effects on material bodies, and on radiation in regions of space, of transfer of heat and of work done on or by the bodies or radiation...

.

Rankine developed a complete theory of the steam engine

Steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid.Steam engines are external combustion engines, where the working fluid is separate from the combustion products. Non-combustion heat sources such as solar power, nuclear power or geothermal energy may be...

and indeed of all heat engines. His manuals of engineering science and practice were used for many decades after their publication in the 1850s and 1860s. He published several hundred papers and notes on science and engineering topics, from 1840 onwards, and his interests were extremely varied, including, in his youth, botany

Botany

Botany, plant science, or plant biology is a branch of biology that involves the scientific study of plant life. Traditionally, botany also included the study of fungi, algae and viruses...

, music theory

Music theory

Music theory is the study of how music works. It examines the language and notation of music. It seeks to identify patterns and structures in composers' techniques across or within genres, styles, or historical periods...

and number theory

Number theory

Number theory is a branch of pure mathematics devoted primarily to the study of the integers. Number theorists study prime numbers as well...

, and, in his mature years, most major branches of science, mathematics and engineering. He was an enthusiastic amateur singer, pianist and cellist who composed his own humorous songs. He was born in Edinburgh

Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

and died in Glasgow

Glasgow

Glasgow is the largest city in Scotland and third most populous in the United Kingdom. The city is situated on the River Clyde in the country's west central lowlands...

, a bachelor.

Early life

Born in EdinburghEdinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland, the second largest city in Scotland, and the eighth most populous in the United Kingdom. The City of Edinburgh Council governs one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas. The council area includes urban Edinburgh and a rural area...

to British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

lieutenant

Lieutenant

A lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer in many nations' armed forces. Typically, the rank of lieutenant in naval usage, while still a junior officer rank, is senior to the army rank...

David Rankine and Barbara Grahame, of a prominent legal and banking family. Rankine was initially educated at home but he later attended Ayr Academy

Ayr Academy

Ayr Academy is a non-denominational secondary school situated in the centre of the town of Ayr in South Ayrshire. It is a comprehensive school for children from the ages of 11 to 18 from Ayr. Ayr Academy's catchment area covers Newton-on-Ayr, Whitletts and the outlying villages of Coylton, Annbank,...

(1828-9) and, very briefly, the High School of Glasgow

High School of Glasgow

The High School of Glasgow is an independent, co-educational day school in Glasgow, Scotland. Founded as the Choir School of Glasgow Cathedral in around 1124, it is the oldest school in Scotland, and the twelfth oldest in the United Kingdom. It remained part of the Church as the city's grammar...

(1830). Around 1830 the family moved to Edinburgh; in 1834 he studied at a Military and Naval Academy with the mathematician George Lees; by that year he was already highly proficient in mathematics and received, as a gift from his uncle, Newton's Principia (1687) in the original Latin.

In 1836 Rankine began to study a spectrum of scientific topics at the University of Edinburgh

University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh, founded in 1583, is a public research university located in Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland, and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The university is deeply embedded in the fabric of the city, with many of the buildings in the historic Old Town belonging to the university...

, including natural history

Natural history

Natural history is the scientific research of plants or animals, leaning more towards observational rather than experimental methods of study, and encompasses more research published in magazines than in academic journals. Grouped among the natural sciences, natural history is the systematic study...

under Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson

thumb|Robert JamesonProfessor Robert Jameson, FRS FRSE was a Scottish naturalist and mineralogist.As Regius Professor at the University of Edinburgh for fifty years, Jameson is notable for his advanced scholarship in natural history, his superb museum collection, and for his tuition of Charles...

and natural philosophy

Natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or the philosophy of nature , is a term applied to the study of nature and the physical universe that was dominant before the development of modern science...

under James David Forbes. Under Forbes he was awarded prizes for essays on methods of physical inquiry and on the undulatory (or wave) theory of light. During vacations, he assisted his father who, from 1830, was manager and, later, effective treasurer and engineer of the Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway

Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway

The Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway, also called the Innocent Railway, was Edinburgh's first railway. It carried coal from the mines in Lothian to its city centre terminus at St Leonards...

which brought coal into the growing city. He left the University of Edinburgh in 1838 without a degree (which was not then unusual) and, perhaps because of straitened family finances, became an apprentice to Sir John Benjamin Macneill

John Benjamin Macneill

Sir John Benjamin MacNeill FRS was an eminent Irish civil engineer of the 19th century, closely associated with Thomas Telford. His most notable projects were railway schemes in Ireland...

, who was at the time surveyor to the Irish Railway Commission. During his pupilage he developed a technique, later known as Rankine's method

Rankine's method

Rankine's method is a technique for laying out circular curves by a combination of chaining and angles at circumference, fully exploiting the theodolite and making a substantial improvement in accuracy and productivity over existing methods....

, for laying out railway curves, fully exploiting the theodolite

Theodolite

A theodolite is a precision instrument for measuring angles in the horizontal and vertical planes. Theodolites are mainly used for surveying applications, and have been adapted for specialized purposes in fields like metrology and rocket launch technology...

and making a substantial improvement in accuracy

Accuracy and precision

In the fields of science, engineering, industry and statistics, the accuracy of a measurement system is the degree of closeness of measurements of a quantity to that quantity's actual value. The precision of a measurement system, also called reproducibility or repeatability, is the degree to which...

and productivity over existing methods. In fact, the technique was simultaneously in use by other engineers – and in the 1860s there was a minor dispute about Rankine's priority.

The year 1842 also marked Rankine's first attempt to reduce the phenomena of heat

Heat

In physics and thermodynamics, heat is energy transferred from one body, region, or thermodynamic system to another due to thermal contact or thermal radiation when the systems are at different temperatures. It is often described as one of the fundamental processes of energy transfer between...

to a mathematical

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

form but he was frustrated by his lack of experimental data. At the time of Queen Victoria's visit to Scotland, he organised a large bonfire

Bonfire

A bonfire is a controlled outdoor fire used for informal disposal of burnable waste material or as part of a celebration. Celebratory bonfires are typically designed to burn quickly and may be very large...

situated on Arthur's Seat

Arthur's Seat, Edinburgh

Arthur's Seat is the main peak of the group of hills which form most of Holyrood Park, described by Robert Louis Stevenson as "a hill for magnitude, a mountain in virtue of its bold design". It is situated in the centre of the city of Edinburgh, about a mile to the east of Edinburgh Castle...

, constructed with radiating air passages under the fuel. The bonfire served as a beacon to initiate a chain of other bonfires across Scotland.

Thermodynamics

Undaunted, he returned to his youthful fascination with the mechanics of the heat engineHeat engine

In thermodynamics, a heat engine is a system that performs the conversion of heat or thermal energy to mechanical work. It does this by bringing a working substance from a high temperature state to a lower temperature state. A heat "source" generates thermal energy that brings the working substance...

. Though his theory of circulating streams of elastic vortices whose volumes spontaneously adapted to their environment sounds fanciful to scientists formed on a modern account, by 1849, he had succeeded in finding the relationship between saturated vapour pressure and temperature

Temperature

Temperature is a physical property of matter that quantitatively expresses the common notions of hot and cold. Objects of low temperature are cold, while various degrees of higher temperatures are referred to as warm or hot...

. The following year, he used his theory to establish relationships between the temperature, pressure

Pressure

Pressure is the force per unit area applied in a direction perpendicular to the surface of an object. Gauge pressure is the pressure relative to the local atmospheric or ambient pressure.- Definition :...

and density

Density

The mass density or density of a material is defined as its mass per unit volume. The symbol most often used for density is ρ . In some cases , density is also defined as its weight per unit volume; although, this quantity is more properly called specific weight...

of gas

Gas

Gas is one of the three classical states of matter . Near absolute zero, a substance exists as a solid. As heat is added to this substance it melts into a liquid at its melting point , boils into a gas at its boiling point, and if heated high enough would enter a plasma state in which the electrons...

es, and expressions for the latent heat

Latent heat

Latent heat is the heat released or absorbed by a chemical substance or a thermodynamic system during a process that occurs without a change in temperature. A typical example is a change of state of matter, meaning a phase transition such as the melting of ice or the boiling of water. The term was...

of evaporation

Evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization of a liquid that occurs only on the surface of a liquid. The other type of vaporization is boiling, which, instead, occurs on the entire mass of the liquid....

of a liquid

Liquid

Liquid is one of the three classical states of matter . Like a gas, a liquid is able to flow and take the shape of a container. Some liquids resist compression, while others can be compressed. Unlike a gas, a liquid does not disperse to fill every space of a container, and maintains a fairly...

. He accurately predicted the surprising fact that the apparent specific heat of saturated

Saturation (chemistry)

In chemistry, saturation has six different meanings, all based on reaching a maximum capacity...

steam

Steam

Steam is the technical term for water vapor, the gaseous phase of water, which is formed when water boils. In common language it is often used to refer to the visible mist of water droplets formed as this water vapor condenses in the presence of cooler air...

would be negative.

Emboldened by his success, he set out to calculate the efficiency of heat engines and used his theory as a basis to deduce the principle, that the maximum efficiency of a heat engine is a function only of the two temperatures between which it operates. Though a similar result had already been derived by Rudolf Clausius

Rudolf Clausius

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius , was a German physicist and mathematician and is considered one of the central founders of the science of thermodynamics. By his restatement of Sadi Carnot's principle known as the Carnot cycle, he put the theory of heat on a truer and sounder basis...

and William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin OM, GCVO, PC, PRS, PRSE, was a mathematical physicist and engineer. At the University of Glasgow he did important work in the mathematical analysis of electricity and formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics, and did much to unify the emerging...

, Rankine claimed that his result rested upon his hypothesis of molecular vortices alone, rather than upon Carnot's theory or some other additional assumption. The work marked the first step on Rankine's journey to develop a more complete theory of heat.

Rankine later recast the results of his molecular theories in terms of a macroscopic account of energy

Energy

In physics, energy is an indirectly observed quantity. It is often understood as the ability a physical system has to do work on other physical systems...

and its transformations. He defined and distinguished between actual energy which was lost in dynamic processes and potential energy by which it was replaced. He assumed the sum of the two energies to be constant, an idea already, although surely not for very long, familiar in the law of conservation of energy

Conservation of energy

The nineteenth century law of conservation of energy is a law of physics. It states that the total amount of energy in an isolated system remains constant over time. The total energy is said to be conserved over time...

. From 1854, he made wide use of his thermodynamic function which he later realised was identical to the entropy

Entropy

Entropy is a thermodynamic property that can be used to determine the energy available for useful work in a thermodynamic process, such as in energy conversion devices, engines, or machines. Such devices can only be driven by convertible energy, and have a theoretical maximum efficiency when...

of Clausius. By 1855, Rankine had formulated a science of energetics

Energetics

Energetics is the study of energy under transformation. Because energy flows at all scales, from the quantum level to the biosphere and cosmos, energetics is a very broad discipline, encompassing for example thermodynamics, chemistry, biological energetics, biochemistry and ecological energetics...

which gave an account of dynamics in terms of energy and its transformations rather than force

Force

In physics, a force is any influence that causes an object to undergo a change in speed, a change in direction, or a change in shape. In other words, a force is that which can cause an object with mass to change its velocity , i.e., to accelerate, or which can cause a flexible object to deform...

and motion

Motion (physics)

In physics, motion is a change in position of an object with respect to time. Change in action is the result of an unbalanced force. Motion is typically described in terms of velocity, acceleration, displacement and time . An object's velocity cannot change unless it is acted upon by a force, as...

. The theory was very influential in the 1890s. In 1859 he proposed the Rankine scale of temperature, an absolute or thermodynamic scale whose degree is equal to a Fahrenheit

Fahrenheit

Fahrenheit is the temperature scale proposed in 1724 by, and named after, the German physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit . Within this scale, the freezing of water into ice is defined at 32 degrees, while the boiling point of water is defined to be 212 degrees...

degree.

Energetics offered Rankine an alternative, and rather more mainstream, approach, to his science and, from the mid 1850s, he made rather less use of his molecular vortices. Yet he still claimed that Maxwell's work on electromagnetics was effectively an extension of his model. And, in 1864, he contended that the microscopic theories of heat proposed by Clausius and James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell of Glenlair was a Scottish physicist and mathematician. His most prominent achievement was formulating classical electromagnetic theory. This united all previously unrelated observations, experiments and equations of electricity, magnetism and optics into a consistent theory...

, based on linear atomic motion, were inadequate. It was only in 1869 that Rankine admitted the success of these rival theories. By that time, his own model of the atom had become almost identical with that of Thomson.

As was his constant aim, especially as a teacher of engineering, he used his own theories to develop a number of practical results and to elucidate their physical principles including:

- The Rankine–Hugoniot equation for propagation of shock waveShock waveA shock wave is a type of propagating disturbance. Like an ordinary wave, it carries energy and can propagate through a medium or in some cases in the absence of a material medium, through a field such as the electromagnetic field...

s, governs the behaviour of shock waves normal to the oncoming flow. It is named after physicists Rankine and the French engineer Pierre Henri HugoniotPierre Henri HugoniotPierre-Henri Hugoniot who mostly lived in Montbéliard, . He was an inventor, mathematician, and physicist who worked on fluid mechanics, especially on issues related to material shock.After going into the marine artillery upon his graduation from the École Polytechnique in 1872, Hugoniot became...

; - The Rankine cycleRankine cycleThe Rankine cycle is a cycle that converts heat into work. The heat is supplied externally to a closed loop, which usually uses water. This cycle generates about 90% of all electric power used throughout the world, including virtually all solar thermal, biomass, coal and nuclear power plants. It is...

, an analysis of an ideal heat-engine with a condensor. Like other thermodynamic cycles, the maximum efficiency of the Rankine cycle is given by calculating the maximum efficiency of the Carnot cycleCarnot cycleThe Carnot cycle is a theoretical thermodynamic cycle proposed by Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot in 1824 and expanded by Benoit Paul Émile Clapeyron in the 1830s and 40s. It can be shown that it is the most efficient cycle for converting a given amount of thermal energy into work, or conversely,...

; - Properties of steam, gases and vapours.

The history of rotordynamics

Rotordynamics

Rotordynamics is a specialized branch of applied mechanics concerned with the behavior and diagnosis of rotating structures. It is commonly used to analyze the behavior of structures ranging from jet engines and steam turbines to auto engines and computer disk storage...

is replete with the interplay of theory and practice. Rankine first performed an analysis of a spinning shaft in 1869, but his model was not adequate and he predicted that supercritical speeds could not be attained.

Fatigue studies

Fatigue (material)

'In materials science, fatigue is the progressive and localized structural damage that occurs when a material is subjected to cyclic loading. The nominal maximum stress values are less than the ultimate tensile stress limit, and may be below the yield stress limit of the material.Fatigue occurs...

failures of railway axles was caused by the initiation and growth of brittle cracks. In the early 1840s he examined many broken axles, especially after the Versailles train crash

Versailles train crash

The Versailles rail accident occurred on May 8, 1842 in the cutting at Meudon Bellevue , France. Following the King's fete celebrations at the Palace of Versailles, a train returning to Paris crashed at Meudon after the leading locomotive broke an axle. The carriages behind piled into the wrecked...

of 1842 when a locomotive axle suddenly fractured and led to the death of over 50 passengers. He showed that the axles had failed by progressive growth of a brittle crack from a shoulder or other stress concentration

Stress concentration

A stress concentration is a location in an object where stress is concentrated. An object is strongest when force is evenly distributed over its area, so a reduction in area, e.g. caused by a crack, results in a localized increase in stress...

source on the shaft, such as a keyway

Keyway

A keyway is the shaped channel in a lock cylinder into which the key slides to gain access to the lock tumblers. Lock keyway shapes vary widely with lock manufacturer, and many manufacturers have a number of unique profiles requiring a specifically milled key blank to engage the lock's...

. He was supported by similar direct analysis of failed axles by Joseph Glynn

Joseph Glynn (engineer)

Joseph Glynn, FRS was a British steam engine designer.He was born the son of James Glynn of the Ouseburn Iron Foundry in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and taught by John Bruce at the Percy Street Academy....

, where the axles failed by slow growth of a brittle crack in a process now known as metal fatigue

Metal Fatigue

Metal Fatigue , is a futuristic science fiction, real-time strategy computer game developed by Zono Incorporated and published by Psygnosis and TalonSoft .-Plot:...

. It was likely that the front axle of one of the locomotives involved in the Versailles train crash

Versailles train crash

The Versailles rail accident occurred on May 8, 1842 in the cutting at Meudon Bellevue , France. Following the King's fete celebrations at the Palace of Versailles, a train returning to Paris crashed at Meudon after the leading locomotive broke an axle. The carriages behind piled into the wrecked...

failed in a similar way. Rankine presented his conclusions in a paper delivered to the Institution of Civil Engineers. His work was ignored however, by many engineers who persisted in believing that stress could cause "re-crystallisation" of the metal, a myth which has persisted even to recent times. The theory of recrystallisation was quite wrong, and inhibited worthwhile research until the work of William Fairbairn

William Fairbairn

Sir William Fairbairn, 1st Baronet was a Scottish civil engineer, structural engineer and shipbuilder.-Early career:...

a few years later, which showed the weakening effect of repeated flexure on large beams. Nevertheless, fatigue remained a serious and poorly understood phenomenon, and was the root cause of many accidents on the railways and elsewhere. It is still a serious problem, but at least is much better understood today, and so can be prevented by careful design.

Other work

He served as regius professorRegius Professor

Regius Professorships are "royal" professorships at the ancient universities of the United Kingdom and Ireland - namely Oxford, Cambridge, St Andrews, Glasgow, Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Dublin. Each of the chairs was created by a monarch, and each appointment, save those at Dublin, is approved by the...

of civil engineering and mechanics at the University of Glasgow

University of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow is the fourth-oldest university in the English-speaking world and one of Scotland's four ancient universities. Located in Glasgow, the university was founded in 1451 and is presently one of seventeen British higher education institutions ranked amongst the top 100 of the...

from November 1855 until his death in December 1872, pursuing engineering research along a number of lines in civil and mechanical engineering

Mechanical engineering

Mechanical engineering is a discipline of engineering that applies the principles of physics and materials science for analysis, design, manufacturing, and maintenance of mechanical systems. It is the branch of engineering that involves the production and usage of heat and mechanical power for the...

.

Rankine was instrumental in the formation of the forerunner of Glasgow University Officer Training Corps

Glasgow and Strathclyde Universities Officer Training Corps

Glasgow and Strathclyde Universities Officer Training Corps is one of nineteen University Officer Training Corps in the United Kingdom and one of four in Scotland, drawing recruits from higher education institutions in and around the city of Glasgow and the wider Strathclyde region in west-central...

, the 2nd Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteer Corps at Glasgow University in July 1859, becoming Major in 1860 after it was formed into the first company of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteer Corps; he served until 1864, when he resigned due to pressure of work - much of it associated with Naval Architecture.

Civil engineering

The Rankine LectureRankine Lecture

The Rankine Lecture is hosted in March each year by the British Geotechnical Association. It is widely viewed as the most prestigious of the invited lectures in Geotechnics.The lecture commemorates W. J. M...

s are named in recognition of the significant contributions he made to:

- Forces in frame structuresStructural analysisStructural analysis is the determination of the effects of loads on physical structures and their components. Structures subject to this type of analysis include all that must withstand loads, such as buildings, bridges, vehicles, machinery, furniture, attire, soil strata, prostheses and...

; - Soil mechanicsSoil mechanicsSoil mechanics is a branch of engineering mechanics that describes the behavior of soils. It differs from fluid mechanics and solid mechanics in the sense that soils consist of a heterogeneous mixture of fluids and particles but soil may also contain organic solids, liquids, and gasses and other...

; most notably in lateral earth pressure theory and the stabilization of retaining wallRetaining wallRetaining walls are built in order to hold back earth which would otherwise move downwards. Their purpose is to stabilize slopes and provide useful areas at different elevations, e.g...

s. The Rankine method of earth pressure analysis is named after him.

Naval architecture

Rankine worked closely with Clyde shipbuilders, especially his friend and life-long collaborator James Robert NapierJames Robert Napier (engineer)

James Robert Napier, FRS , engineer and inventor of Napier's diagram, a tool for nautical navigation.-Early life and education:...

, to make naval architecture into an engineering science. He was a founding member, and first President of the Institution of Engineers & Shipbuilders in Scotland in 1857. He was an early member of the Royal Institute of Naval Architects (founded 1860) and attended many of its annual meetings. With William Thomson and others, Rankine was a member of the board of enquiry into the controversial sinking of the HMS Captain

HMS Captain (1869)

HMS Captain was an unsuccessful warship built for the Royal Navy due to public pressure. She was a masted turret ship, designed and built by a private contractor against the wishes of the Controller's department...

.

Honours

- Fellow of the Royal Scottish Society of Arts

- Associate of the Institution of Civil EngineersInstitution of Civil EngineersFounded on 2 January 1818, the Institution of Civil Engineers is an independent professional association, based in central London, representing civil engineering. Like its early membership, the majority of its current members are British engineers, but it also has members in more than 150...

, (1843) (he was never a full Member) - Fellow of the Royal Society of EdinburghRoyal Society of EdinburghThe Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity, operating on a wholly independent and non-party-political basis and providing public benefit throughout Scotland...

, (1850) - Fellow of the Royal SocietyRoyal SocietyThe Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

of London, (1853) - Keith MedalKeith MedalThe Keith Medal is a prize awarded by the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Scotland's national academy, for a scientific paper published in the society's scientific journals, preference being given to a paper containing a discovery, either in mathematics or earth sciences.The medal was inaugurated in...

of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, (1854) - LL.D. from Trinity College, DublinTrinity College, DublinTrinity College, Dublin , formally known as the College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Queen Elizabeth near Dublin, was founded in 1592 by letters patent from Queen Elizabeth I as the "mother of a university", Extracts from Letters Patent of Elizabeth I, 1592: "...we...found and...

, (1857) - Foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of SciencesRoyal Swedish Academy of SciencesThe Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences or Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. The Academy is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization which acts to promote the sciences, primarily the natural sciences and mathematics.The Academy was founded on 2...

, (1868) - The Rankine absolute Fahrenheit scale is named in his honour.

- RankineRankine (crater)Rankine is a small lunar impact crater near the eastern limb of the Moon. It lies on the southern floor of the satellite crater Maclaurin B, a 43-kilometer-diameter feature which is located to the southeast of Maclaurin. To the east of Rankine is the crater Gilbert, and directly to the south is von...

, a small impact craterImpact craterIn the broadest sense, the term impact crater can be applied to any depression, natural or manmade, resulting from the high velocity impact of a projectile with a larger body...

near the eastern limb of the MoonMoonThe Moon is Earth's only known natural satellite,There are a number of near-Earth asteroids including 3753 Cruithne that are co-orbital with Earth: their orbits bring them close to Earth for periods of time but then alter in the long term . These are quasi-satellites and not true moons. For more...

, is also named in his honour.

See also

- Metal fatigueMetal FatigueMetal Fatigue , is a futuristic science fiction, real-time strategy computer game developed by Zono Incorporated and published by Psygnosis and TalonSoft .-Plot:...

- Rankine bodyRankine bodyThe Rankine body discovered by William John Macquorn Rankine, is a feature of naval architecture involving the flow of liquid around a body/surface....

- Rankine CycleRankine cycleThe Rankine cycle is a cycle that converts heat into work. The heat is supplied externally to a closed loop, which usually uses water. This cycle generates about 90% of all electric power used throughout the world, including virtually all solar thermal, biomass, coal and nuclear power plants. It is...

- State functionState functionIn thermodynamics, a state function, function of state, state quantity, or state variable is a property of a system that depends only on the current state of the system, not on the way in which the system acquired that state . A state function describes the equilibrium state of a system...

- Momentum theoryMomentum theoryIn fluid dynamics, the momentum theory or disk actuator theory is a theory describing a mathematical model of an ideal actuator disk, such as a propeller or helicopter rotor, by W.J.M. Rankine , Alfred George Greenhill and R.E. Froude ....

Publications

- Manual of Applied Mechanics, (1858)

- Manual of the Steam Engine and Other Prime Movers, (1859)

- Manual of Civil Engineering, (1861)

- Shipbuilding, theoretical and practical, (1866)

- Manual of Machinery and Millwork, (1869)

Papers

- Mechanical Action of Heat, (1850), read at the Royal Society of Edinburgh

- General Law of Transformation of Energy, (1853), read at the Glasgow Philosophical Society

- On the Thermodynamic Theory of Waves of Finite Longitudinal Disturbance, (1869)

- Outlines of the Science of Energetics, published in the Proceedings of the Philosophical Society of Glasgow in 1855

About Rankine