ACS National Historical Chemical Landmarks

Encyclopedia

American Chemical Society

The American Chemical Society is a scientific society based in the United States that supports scientific inquiry in the field of chemistry. Founded in 1876 at New York University, the ACS currently has more than 161,000 members at all degree-levels and in all fields of chemistry, chemical...

in 1992 and has recognized more than 60 landmarks to date. The program celebrates the centrality of chemistry

The central science

Chemistry is often called the central science because of its role in connecting the physical sciences, which include chemistry, with the life sciences and applied sciences such as medicine and engineering. The nature of this relationship is one of the main topics in the philosophy of chemistry and...

. The designation of seminal achievements in the history of chemistry demonstrates how chemists have benefited society by fulfilling the ACS vision: Improving people's lives through the transforming power of chemistry.

1994

- The Chandler Chemistry Laboratory at Lehigh UniversityLehigh UniversityLehigh University is a private, co-educational university located in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, in the Lehigh Valley region of the United States. It was established in 1865 by Asa Packer as a four-year technical school, but has grown to include studies in a wide variety of disciplines...

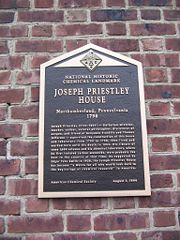

in Bethlehem, PennsylvaniaBethlehem, PennsylvaniaBethlehem is a city in Lehigh and Northampton Counties in the Lehigh Valley region of eastern Pennsylvania, in the United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 74,982, making it the seventh largest city in Pennsylvania, after Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Allentown, Erie,... - The Joseph Priestley HouseJoseph Priestley HouseThe Joseph Priestley House was the American home of 18th-century British theologian, Dissenting clergyman, natural philosopher , educator, and political theorist Joseph Priestley from 1798 until his death. Located in Northumberland, Pennsylvania, the house, which was designed by Priestley's wife...

, Pennsylvania home of Joseph PriestleyJoseph PriestleyJoseph Priestley, FRS was an 18th-century English theologian, Dissenting clergyman, natural philosopher, chemist, educator, and political theorist who published over 150 works...

, discoverer of oxygen

1995

- Atomic weight of oxygenOxygenOxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

calculated by Edward MorleyEdward MorleyEdward Williams Morley was an American scientist famous for the Michelson–Morley experiment.-Biography:... - CoalCoalCoal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock usually occurring in rock strata in layers or veins called coal beds or coal seams. The harder forms, such as anthracite coal, can be regarded as metamorphic rock because of later exposure to elevated temperature and pressure...

as a source of acetylAcetylIn organic chemistry, acetyl is a functional group, the acyl with chemical formula COCH3. It is sometimes represented by the symbol Ac . The acetyl group contains a methyl group single-bonded to a carbonyl...

chemicals for plastics materials and fibers rather than petroleum - First nylonNylonNylon is a generic designation for a family of synthetic polymers known generically as polyamides, first produced on February 28, 1935, by Wallace Carothers at DuPont's research facility at the DuPont Experimental Station...

plant, built by DuPontDuPontE. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company , commonly referred to as DuPont, is an American chemical company that was founded in July 1802 as a gunpowder mill by Eleuthère Irénée du Pont. DuPont was the world's third largest chemical company based on market capitalization and ninth based on revenue in 2009...

, at Seaford, DelawareSeaford, DelawareSeaford is a city located along the Nanticoke River in Sussex County, Delaware. According to the 2010 Census Bureau figures, the population of the city is 6,928, an increase of 3.4% from the 2000 census... - Riverside Laboratory at Universal Oil Products

1996

- The Sohio AcrylonitrileAcrylonitrileAcrylonitrile is the chemical compound with the formula C3H3N. This pungent-smelling colorless liquid often appears yellow due to impurities. It is an important monomer for the manufacture of useful plastics. In terms of its molecular structure, it consists of a vinyl group linked to a nitrile...

production process - HoudryEugene HoudryEugene Houdry was a French mechanical engineer who invented catalytic cracking of petroleum feed stocks. He originally focused on using lignite as a feedstock, but switched to using heavy liquid tars after moving to the United States in 1930...

process for the selective conversion or catalytic crackingCracking (chemistry)In petroleum geology and chemistry, cracking is the process whereby complex organic molecules such as kerogens or heavy hydrocarbons are broken down into simpler molecules such as light hydrocarbons, by the breaking of carbon-carbon bonds in the precursors. The rate of cracking and the end products...

of crude petroleum to gasolineGasolineGasoline , or petrol , is a toxic, translucent, petroleum-derived liquid that is primarily used as a fuel in internal combustion engines. It consists mostly of organic compounds obtained by the fractional distillation of petroleum, enhanced with a variety of additives. Some gasolines also contain... - Kem-Tone water-based or latex paint developed by Sherwin-Williams chemists

- Williams-Miles History of Chemistry Collection housed at Harding UniversityHarding UniversityHarding University is located in Searcy, Arkansas, in the United States, about north-east of Little Rock. It is a private liberal arts Christian university associated with the Churches of Christ. The university takes its name from James A...

in Searcy, ArkansasSearcy, ArkansasSearcy is the largest city and county seat of White County, Arkansas, United States. According to 2006 Census Bureau estimates, the population of the city is 20,663. It is the principal city of the Searcy, AR Micropolitan Statistical Area which encompasses all of White County...

1997

- Hall-Héroult processHall-Héroult processThe Hall–Héroult process is the major industrial process for the production of aluminium. It involves dissolving alumina in molten cryolite, and electrolysing the molten salt bath to obtain pure aluminium metal.-Process:...

for the industrial production of aluminum by electrochemistryElectrochemistryElectrochemistry is a branch of chemistry that studies chemical reactions which take place in a solution at the interface of an electron conductor and an ionic conductor , and which involve electron transfer between the electrode and the electrolyte or species in solution.If a chemical reaction is...

discovered in 1886 was demonstrated by American chemist Charles Martin HallCharles Martin HallCharles Martin Hall was an American inventor, music enthusiast, and chemist. He is best known for his invention in 1886 of an inexpensive method for producing aluminium, which became the first metal to attain widespread use since the prehistoric discovery of iron.-Early years:Charles Martin Hall...

and independently in the same year by French chemist Paul HéroultPaul HéroultThe French scientist Paul Héroult was the inventor of the aluminium electrolysis and of the electric steel furnace. He lived in Thury-Harcourt, Normandy.Christian Bickert said of him... - First electrolytic production of bromineBromineBromine ") is a chemical element with the symbol Br, an atomic number of 35, and an atomic mass of 79.904. It is in the halogen element group. The element was isolated independently by two chemists, Carl Jacob Löwig and Antoine Jerome Balard, in 1825–1826...

by Herbert Henry DowHerbert Henry DowHerbert Henry Dow was a Canadian born, American chemical industrialist. He is a graduate of Case School of Applied Science in Cleveland, Ohio. His most significant achievement was the founding of the Dow Chemical Company in 1897...

at the Evens Mill in Midland, MichiganMidland, MichiganMidland is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan in the Tri-Cities region of the state. It is the county seat of Midland County. The city's population was 41,863 as of the 2010 census. It is the principal city of the Midland Micropolitan Statistical Area.... - Gilman Hall at the University of California, BerkeleyUniversity of California, BerkeleyThe University of California, Berkeley , is a teaching and research university established in 1868 and located in Berkeley, California, USA...

- Radiation chemistry commercialized

1998

- Commercial processes for making calcium carbideCalcium carbidethumb|right|Calcium carbide.Calcium carbide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula of CaC2. The pure material is colorless, however pieces of technical grade calcium carbide are grey or brown and consist of only 80-85% of CaC2 . Because of presence of PH3, NH3, and H2S it has a...

and acetyleneAcetyleneAcetylene is the chemical compound with the formula C2H2. It is a hydrocarbon and the simplest alkyne. This colorless gas is widely used as a fuel and a chemical building block. It is unstable in pure form and thus is usually handled as a solution.As an alkyne, acetylene is unsaturated because...

accidentally discovered in 1892 by Thomas WillsonThomas WillsonThomas Leopold "Carbide" Willson was a Canadian inventor.He was born on a farm near Princeton, Ontario in 1860 and went to school in Hamilton, Ontario. By the age of 21, he had designed and patented the first electric arc lamps used in Hamilton... - Fluid bed reactor for petroleum crackingCracking (chemistry)In petroleum geology and chemistry, cracking is the process whereby complex organic molecules such as kerogens or heavy hydrocarbons are broken down into simpler molecules such as light hydrocarbons, by the breaking of carbon-carbon bonds in the precursors. The rate of cracking and the end products...

in gasoline production - Havemeyer Hall at Columbia UniversityColumbia UniversityColumbia University in the City of New York is a private, Ivy League university in Manhattan, New York City. Columbia is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York, the fifth oldest in the United States, and one of the country's nine Colonial Colleges founded before the...

- Raman EffectRaman scatteringRaman scattering or the Raman effect is the inelastic scattering of a photon. It was discovered by Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman and Kariamanickam Srinivasa Krishnan in liquids, and by Grigory Landsberg and Leonid Mandelstam in crystals....

discovered by Indian physicist Chandrasekhara Venkata RamanChandrasekhara Venkata RamanSir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman, FRS was an Indian physicist whose work was influential in the growth of science in the world. He was the recipient of the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1930 for the discovery that when light traverses a transparent material, some of the light that is deflected... - Synthetic rubberSynthetic rubberSynthetic rubber is is any type of artificial elastomer, invariably a polymer. An elastomer is a material with the mechanical property that it can undergo much more elastic deformation under stress than most materials and still return to its previous size without permanent deformation...

developed by the United States Synthetic Rubber Program (1939–1945) to - Development process for TagametCimetidineCimetidine INN is a histamine H2-receptor antagonist that inhibits the production of acid in the stomach. It is largely used in the treatment of heartburn and peptic ulcers. It is marketed by GlaxoSmithKline under the trade name Tagamet...

used for treating ulcers at SmithKline Beecham PharmaceuticalsGlaxoSmithKlineGlaxoSmithKline plc is a global pharmaceutical, biologics, vaccines and consumer healthcare company headquartered in London, United Kingdom...

1999

- The discovery of penicillinPenicillinPenicillin is a group of antibiotics derived from Penicillium fungi. They include penicillin G, procaine penicillin, benzathine penicillin, and penicillin V....

- PhysostigminePhysostigminePhysostigmine is a parasympathomimetic alkaloid, specifically, a reversible cholinesterase inhibitor. It occurs naturally in the Calabar bean....

(used for the treatment of glaucomaGlaucomaGlaucoma is an eye disorder in which the optic nerve suffers damage, permanently damaging vision in the affected eye and progressing to complete blindness if untreated. It is often, but not always, associated with increased pressure of the fluid in the eye...

) synthesis first accomplished at the Minshall Laboratory, DePauw UniversityDePauw UniversityDePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, USA, is a private, national liberal arts college with an enrollment of approximately 2,400 students. The school has a Methodist heritage and was originally known as Indiana Asbury University. DePauw is a member of both the Great Lakes Colleges Association...

by African American chemist Percy L. Julian - ProgesteroneProgesteroneProgesterone also known as P4 is a C-21 steroid hormone involved in the female menstrual cycle, pregnancy and embryogenesis of humans and other species...

synthesis from a Mexican yam developed by Russell MarkerRussell MarkerRussell Earl Marker was an American chemist who invented the octane rating system when he was working at the Ethyl Corporation. Later in his career, he went on to found a steroid industry in Mexico when he successfully made synthetic progesterone from chemical constituents found in Mexican yams...

in a process known as Marker degradationMarker degradationThe Marker degradation is a three-step synthetic route in steroid chemistry developed by American chemist Russell Earl Marker in 1938–40. It is used for the production of cortisone and mammalian sex hormones from plant steroids, and established Mexico as a world center for steroid production in...

and Mexican steroid industry - The foundation of polymer sciencePolymer sciencePolymer science or macromolecular science is the subfield of materials science concerned with polymers, primarily synthetic polymers such as plastics...

by Hermann StaudingerHermann Staudinger- External links :* Staudinger's * Staudinger's Nobel Lecture *.... - Polypropylene and high-density polyethylene discovered by J. Paul Hogan and Robert BanksRobert Banks (chemist)Robert L. Banks was an American chemist. He was born and grew up in Piedmont, Missouri. He attended Southeast Missouri State University, and initiated into Alpha Phi Omega in 1940. He joined the Phillips Petroleum company in 1946 and worked there until he retired in 1985.He was a fellow research...

working at Phillips Petroleum Company - Separation of rare earth elements by Charles James at the University of New HampshireUniversity of New HampshireThe University of New Hampshire is a public university in the University System of New Hampshire , United States. The main campus is in Durham, New Hampshire. An additional campus is located in Manchester. With over 15,000 students, UNH is the largest university in New Hampshire. The university is...

- Work of French scientist Antoine LavoisierAntoine LavoisierAntoine-Laurent de Lavoisier , the "father of modern chemistry", was a French nobleman prominent in the histories of chemistry and biology...

, who elucidated the principles of modern chemistry

2000

- Bowood HouseBowood HouseBowood is a grade I listed Georgian country house with interiors by Robert Adam and a garden designed by Lancelot "Capability" Brown. It is adjacent to the village of Derry Hill, halfway between Calne and Chippenham in Wiltshire, England...

in Wiltshire, U.K.WiltshireWiltshire is a ceremonial county in South West England. It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset, Somerset, Hampshire, Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire. It contains the unitary authority of Swindon and covers...

site of Joseph PriestleyJoseph PriestleyJoseph Priestley, FRS was an 18th-century English theologian, Dissenting clergyman, natural philosopher, chemist, educator, and political theorist who published over 150 works...

's discovery of oxygenOxygenOxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

in 1774 - Edgar Fahs Smith Memorial Collection at The University of Pennsylvania

- The discovery of heliumHeliumHelium is the chemical element with atomic number 2 and an atomic weight of 4.002602, which is represented by the symbol He. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas that heads the noble gas group in the periodic table...

in natural gasNatural gasNatural gas is a naturally occurring gas mixture consisting primarily of methane, typically with 0–20% higher hydrocarbons . It is found associated with other hydrocarbon fuel, in coal beds, as methane clathrates, and is an important fuel source and a major feedstock for fertilizers.Most natural...

by Hamilton CadyHamilton CadyHamilton Perkins Cady, , was an American chemist who in 1907 in collaboration with David McFarland discovered that helium could be extracted from natural gas.-Early life:...

and David Ford McFarland while working in Bailey Hall at The University of Kansas on a sample from a gas well in Dexter, KansasDexter, KansasDexter is a city in Cowley County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 278.-History:Early in the 20th century Dexter became the focus of research that would confirm the existence of an abundance of naturally occurring and readily available helium. In May 1903, a...

in 1905 - Isolation of organic free radicals by University of MichiganUniversity of MichiganThe University of Michigan is a public research university located in Ann Arbor, Michigan in the United States. It is the state's oldest university and the flagship campus of the University of Michigan...

chemist Moses GombergMoses GombergMoses Gomberg was a chemistry professor at the University of Michigan....

in 1900 - The establishment of modern polymer sciencePolymer sciencePolymer science or macromolecular science is the subfield of materials science concerned with polymers, primarily synthetic polymers such as plastics...

by Wallace CarothersWallace CarothersWallace Hume Carothers was an American chemist, inventor and the leader of organic chemistry at DuPont, credited with the invention of nylon.... - Protein and nucleic acid chemistry at Rockefeller UniversityRockefeller UniversityThe Rockefeller University is a private university offering postgraduate and postdoctoral education. It has a strong concentration in the biological sciences. It is also known for producing numerous Nobel laureates...

- Discovery of transcurium elements at E. O. Lawrence Berkeley National LaboratoryLawrence Berkeley National LaboratoryThe Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory , is a U.S. Department of Energy national laboratory conducting unclassified scientific research. It is located on the grounds of the University of California, Berkeley, in the Berkeley Hills above the central campus...

at the University of California, BerkeleyUniversity of California, BerkeleyThe University of California, Berkeley , is a teaching and research university established in 1868 and located in Berkeley, California, USA...

including berkelium (97)BerkeliumBerkelium , is a synthetic element with the symbol Bk and atomic number 97, a member of the actinide and transuranium element series. It is named after the city of Berkeley, California, the location of the University of California Radiation Laboratory where it was discovered in December 1949...

, californium (98)CaliforniumCalifornium is a radioactive metallic chemical element with the symbol Cf and atomic number 98. The element was first made in the laboratory in 1950 by bombarding curium with alpha particles at the University of California, Berkeley. It is the ninth member of the actinide series and was the...

, einsteinium (99)EinsteiniumEinsteinium is a synthetic element with the symbol Es and atomic number 99. It is the seventh transuranic element, and an actinide.Einsteinium was discovered in the debris of the first hydrogen bomb explosion in 1952, and named after Albert Einstein...

, fermium (100)FermiumFermium is a synthetic element with the symbol Fm. It is the 100th element in the periodic table and a member of the actinide series. It is the heaviest element that can be formed by neutron bombardment of lighter elements, and hence the last element that can be prepared in macroscopic quantities,...

, mendelevium (101)MendeleviumMendelevium is a synthetic element with the symbol Md and the atomic number 101. A metallic radioactive transuranic element in the actinide series, mendelevium is usually synthesized by bombarding einsteinium with alpha particles. It was named after Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev, who created the...

, nobelium (102)NobeliumNobelium is a synthetic element with the symbol No and atomic number 102. It was first correctly identified in 1966 by scientists at the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions in Dubna, Soviet Union...

, lawrencium (103)LawrenciumLawrencium is a radioactive synthetic chemical element with the symbol Lr and atomic number 103. In the periodic table of the elements, it is a period 7 d-block element and the last element of actinide series...

, rutherfordium (104)RutherfordiumRutherfordium is a chemical element with symbol Rf and atomic number 104, named in honor of New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford. It is a synthetic element and radioactive; the most stable known isotope, 267Rf, has a half-life of approximately 1.3 hours.In the periodic table of the elements,...

, dubnium (105)DubniumThe Soviet team proposed the name nielsbohrium in honor of the Danish nuclear physicist Niels Bohr. The American team proposed that the new element should be named hahnium , in honor of the late German chemist Otto Hahn...

, and seaborgium (106)SeaborgiumSeaborgium is a synthetic chemical element with the symbol Sg and atomic number 106.Seaborgium is a synthetic element whose most stable isotope 271Sg has a half-life of 1.9 minutes. A new isotope 269Sg has a potentially slightly longer half-life based on the observation of a single decay...

2001

- Savannah Pulp and Paper Laboratory founded by Georgia chemist Charles H. Herty, Sr.Charles HertyCharles Holmes Herty, Sr. was an American academic, scientist and businessman. Serving in academia as a chemistry professor to begin his career, Herty concurrently promoted collegiate athletics including creating the first varsity football team at the University of Georgia...

who discovered a method to make quality paper from southern pine trees in 1932 - National Institute of Standards and TechnologyNational Institute of Standards and TechnologyThe National Institute of Standards and Technology , known between 1901 and 1988 as the National Bureau of Standards , is a measurement standards laboratory, otherwise known as a National Metrological Institute , which is a non-regulatory agency of the United States Department of Commerce...

, (NIST) - The commercialization of aluminum by the Pittsburgh Reduction Company (Aluminum Company of AmericaAlcoaAlcoa Inc. is the world's third largest producer of aluminum, behind Rio Tinto Alcan and Rusal. From its operational headquarters in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Alcoa conducts operations in 31 countries...

) in 1888 that used the elctrochemical process discovered by Charles Martin HallCharles Martin HallCharles Martin Hall was an American inventor, music enthusiast, and chemist. He is best known for his invention in 1886 of an inexpensive method for producing aluminium, which became the first metal to attain widespread use since the prehistoric discovery of iron.-Early years:Charles Martin Hall... - The founding of the American Chemical SocietyAmerican Chemical SocietyThe American Chemical Society is a scientific society based in the United States that supports scientific inquiry in the field of chemistry. Founded in 1876 at New York University, the ACS currently has more than 161,000 members at all degree-levels and in all fields of chemistry, chemical...

in 1876 and its first president John William DraperJohn William DraperJohn William Draper was an American scientist, philosopher, physician, chemist, historian, and photographer. He is credited with producing the first clear photograph of a female face and the first detailed photograph of the Moon...

2002

- African-American engineer Norbert RillieuxNorbert RillieuxNorbert Rillieux , an American inventor and engineer, is most noted for his invention of the multiple-effect evaporator, an energy-efficient means of evaporating water. This invention was an important development in the growth of the sugar industry...

, inventor of the multiple-effect evaporatorMultiple-effect evaporatorA multiple-effect evaporator, as defined in chemical engineering, is an apparatus for efficiently using the heat from steam to evaporate water. In a multiple-effect evaporator, water is boiled in a sequence of vessels, each held at a lower pressure than the last...

(1934) and a revolution in sugar processing giving better quality with less manpower and at reduced cost - Hungarian chemist Albert Szent-GyörgyiAlbert Szent-GyörgyiAlbert Szent-Györgyi de Nagyrápolt was a Hungarian physiologist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1937. He is credited with discovering vitamin C and the components and reactions of the citric acid cycle...

and the discovery of Vitamin CVitamin CVitamin C or L-ascorbic acid or L-ascorbate is an essential nutrient for humans and certain other animal species. In living organisms ascorbate acts as an antioxidant by protecting the body against oxidative stress...

which he proved was identical to the hexuronic acid that could be extracted in kilogram quantities from paprika - Noyes LaboratoryNoyes LaboratoryNoyes Laboratory is a chemistry laboratory at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign that was established in 1902. When it was expanded in 1916 it housed the largest chemistry department in the United States. In 1939 the building was dedicated in honor of the influential U of I chemist...

: One Hundred Years of Chemistry - Alice HamiltonAlice HamiltonAlice Hamilton was the first woman appointed to the faculty of Harvard University and was a leading expert in the field of occupational health...

and the development of occupational medicine that helped make the American workplace less dangerous - Quality and stability of frozen foods made possible by the research of the Western Regional Research Center after World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

that investigated how time and temperature affected their stability and quality

2003

- The discovery of the life-saving anticancer agents CamptothecinCamptothecinCamptothecin is a cytotoxic quinoline alkaloid which inhibits the DNA enzyme topoisomerase I . It was discovered in 1966 by M. E. Wall and M. C. Wani in systematic screening of natural products for anticancer drugs. It was isolated from the bark and stem of Camptotheca acuminata , a tree native to...

(1966) and Taxol (1971) obtained from the Chinese Camptotheca acuminata and the Pacific yew tree respectively at the Research Triangle Institute (RTI) by the research team of Monroe Wall, Mansukh C. WaniMansukh C. WaniProfessor Mansukh C. Wani, Ph.D. is a principal scientist at the Research Triangle Institute in North Carolina. He is co-discoverer of Taxol and camptothecin, two anti-cancer drugs considered standard in the treatment to fight ovarian, breast, lung and colon cancers. In 2000, Dr. Wani received an...

, and colleagues - The Polymer Research Institute at the Polytechnic University of New YorkPolytechnic University of New YorkThe Polytechnic Institute of New York University, often referred to as Polytechnic Institute of NYU, NYU Polytechnic, or NYU-Poly, is the engineering and applied sciences affiliate of New York University...

, established in 1946 by Herman Mark, the first academic facility in the United States devoted to the study and teaching of polymer sciencePolymer sciencePolymer science or macromolecular science is the subfield of materials science concerned with polymers, primarily synthetic polymers such as plastics... - The development of high-performance Carbon fiberCarbon fiberCarbon fiber, alternatively graphite fiber, carbon graphite or CF, is a material consisting of fibers about 5–10 μm in diameter and composed mostly of carbon atoms. The carbon atoms are bonded together in crystals that are more or less aligned parallel to the long axis of the fiber...

s by scientists at the Parma Technical Center of Union Carbide Corporation (now GrafTech International)

2004

- The Beckman pH meterPH meterA pH meter is an electronic instrument used for measuring the pH of a liquid...

, developed by Arnold Orville BeckmanArnold Orville BeckmanArnold Orville Beckman was an American chemist who founded Beckman Instruments based on his 1934 invention of the pH meter, a device for measuring acidity. He also funded the first transistor company, thus giving rise to Silicon Valley.-Early life:Beckman was born in Cullom, Illinois, the son of...

while a member of the faculty of the California Institute of TechnologyCalifornia Institute of TechnologyThe California Institute of Technology is a private research university located in Pasadena, California, United States. Caltech has six academic divisions with strong emphases on science and engineering...

, the first commercially successful electronic pH meter - The evolution of durable press and flame retardantFlame retardantFlame retardants are chemicals used in thermoplastics, thermosets, textiles and coatings that inhibit or resist the spread of fire. These can be separated into several different classes of chemicals:...

cottonCottonCotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

by the Southern Regional Research Center that made cotton more competitive with synthetic fabrics - Carl Ferdinand CoriCarl Ferdinand CoriCarl Ferdinand Cori was a Czech biochemist and pharmacologist born in Prague who, together with his wife Gerty Cori and Argentine physiologist Bernardo Houssay, received a Nobel Prize in 1947 for their discovery of how glycogen – a derivative of glucose – is broken down and...

and Gerty CoriGerty CoriGerty Theresa Cori was an American biochemist who became the third woman—and first American woman—to win a Nobel Prize in science, and the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.Cori was born in Prague...

and their research that led to our current understanding of the metabolismMetabolismMetabolism is the set of chemical reactions that happen in the cells of living organisms to sustain life. These processes allow organisms to grow and reproduce, maintain their structures, and respond to their environments. Metabolism is usually divided into two categories...

of sugarSugarSugar is a class of edible crystalline carbohydrates, mainly sucrose, lactose, and fructose, characterized by a sweet flavor.Sucrose in its refined form primarily comes from sugar cane and sugar beet...

s or the "Cori cycleCori cycleThe Cori cycle , named after its discoverers, Carl Cori and Gerty Cori, refers to the metabolic pathway in which lactate produced by anaerobic glycolysis in the muscles moves to the liver and is converted to glucose, which then returns to the muscles and is converted back to lactate.-Cycle:Muscular...

" by which the body reversibly converts glucoseGlucoseGlucose is a simple sugar and an important carbohydrate in biology. Cells use it as the primary source of energy and a metabolic intermediate...

and glycogenGlycogenGlycogen is a molecule that serves as the secondary long-term energy storage in animal and fungal cells, with the primary energy stores being held in adipose tissue...

2005

- George Washington CarverGeorge Washington CarverGeorge Washington Carver , was an American scientist, botanist, educator, and inventor. The exact day and year of his birth are unknown; he is believed to have been born into slavery in Missouri in January 1864....

who, despite being born into slaverySlaverySlavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

, went on to join the faculty of Tuskegee Institute in 1896 where he developed new products including peanutPeanutThe peanut, or groundnut , is a species in the legume or "bean" family , so it is not a nut. The peanut was probably first cultivated in the valleys of Peru. It is an annual herbaceous plant growing tall...

s and sweet potatoSweet potatoThe sweet potato is a dicotyledonous plant that belongs to the family Convolvulaceae. Its large, starchy, sweet-tasting, tuberous roots are an important root vegetable. The young leaves and shoots are sometimes eaten as greens. Of the approximately 50 genera and more than 1,000 species of...

es and researched crop rotationCrop rotationCrop rotation is the practice of growing a series of dissimilar types of crops in the same area in sequential seasons.Crop rotation confers various benefits to the soil. A traditional element of crop rotation is the replenishment of nitrogen through the use of green manure in sequence with cereals...

and the restoration of soil fertility - Selman WaksmanSelman WaksmanSelman Abraham Waksman was an American biochemist and microbiologist whose research into organic substances—largely into organisms that live in soil—and their decomposition promoted the discovery of Streptomycin, and several other antibiotics...

, who isolated antibiotics produced by actinomycetes, including streptomycinStreptomycinStreptomycin is an antibiotic drug, the first of a class of drugs called aminoglycosides to be discovered, and was the first antibiotic remedy for tuberculosis. It is derived from the actinobacterium Streptomyces griseus. Streptomycin is a bactericidal antibiotic. Streptomycin cannot be given...

which was the first effective pharmaceutical treatment for tuberculosisTuberculosisTuberculosis, MTB, or TB is a common, and in many cases lethal, infectious disease caused by various strains of mycobacteria, usually Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis usually attacks the lungs but can also affect other parts of the body...

, choleraCholeraCholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission occurs primarily by drinking or eating water or food that has been contaminated by the diarrhea of an infected person or the feces...

and typhoid feverTyphoid feverTyphoid fever, also known as Typhoid, is a common worldwide bacterial disease, transmitted by the ingestion of food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person, which contain the bacterium Salmonella enterica, serovar Typhi...

, and neomycinNeomycinNeomycin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic that is found in many topical medications such as creams, ointments, and eyedrops. The discovery of Neomycin dates back to 1949. It was discovered in the lab of Selman Waksman, who was later awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and medicine in 1951...

used as a topicalTopicalIn medicine, a topical medication is applied to body surfaces such as the skin or mucous membranes such as the vagina, anus, throat, eyes and ears.Many topical medications are epicutaneous, meaning that they are applied directly to the skin...

antibacterial agent - The development of the Columbia dry cellDry Cell-Dry Cell's formation:Part of the band formed in 1998 when guitarist Danny Hartwell and drummer Brandon Brown met at the Ratt Show on the Sunset Strip. They later met up with then-vocalist Judd Gruenbaum. The original name of the band was "Beyond Control"....

batteryBattery (electricity)An electrical battery is one or more electrochemical cells that convert stored chemical energy into electrical energy. Since the invention of the first battery in 1800 by Alessandro Volta and especially since the technically improved Daniell cell in 1836, batteries have become a common power...

, the first sealed dry cell battery successfully manufactured for the mass market by the National Carbon Company (predecessor of Energizer) in 1896

2006

- Neil Bartlett's demonstration of the first reaction of a noble gasNoble gasThe noble gases are a group of chemical elements with very similar properties: under standard conditions, they are all odorless, colorless, monatomic gases, with very low chemical reactivity...

by combining xenonXenonXenon is a chemical element with the symbol Xe and atomic number 54. The element name is pronounced or . A colorless, heavy, odorless noble gas, xenon occurs in the Earth's atmosphere in trace amounts...

with platinum fluoridePlatinum hexafluoridePlatinum hexafluoride is the chemical compound with the formula PtF6. It is a dark-red volatile solid that forms a red gas. The compound is a unique example of platinum in the +6 oxidation state... - Rumford baking powderBaking powderBaking powder is a dry chemical leavening agent used to increase the volume and lighten the texture of baked goods such as muffins, cakes, scones and American-style biscuits. Baking powder works by releasing carbon dioxide gas into a batter or dough through an acid-base reaction, causing bubbles in...

, developed in the mid-19th century by the Harvard UniversityHarvard UniversityHarvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

RumfordBenjamin ThompsonSir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford , FRS was an American-born British physicist and inventor whose challenges to established physical theory were part of the 19th century revolution in thermodynamics. He also served as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Loyalist forces in America during the American...

Professor Eben Horsford by adding calcium acid phosphateDicalcium phosphateDicalcium phosphate, also known as calcium monohydrogen phosphate, is a dibasic calcium phosphate. It is usually found as the dihydrate, with the chemical formula of CaHPO4 • 2H2O, but it can be thermally converted to the anhydrous form. It is practically insoluble in water, with a solubility of...

, to make bakingBakingBaking is the technique of prolonged cooking of food by dry heat acting by convection, and not by radiation, normally in an oven, but also in hot ashes, or on hot stones. It is primarily used for the preparation of bread, cakes, pastries and pies, tarts, quiches, cookies and crackers. Such items...

easier, quicker, and more reliable - The development of TideTide (detergent)Tide is the brand-name of a popular laundry detergent manufactured by Procter & Gamble and first introduced to the United States consumer in 1946. It is also marketed in Canada, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, India and several other countries...

, the first heavy-duty synthetic laundry detergentLaundry detergentLaundry detergent, or washing powder, is a substance that is a type of detergent that is added for cleaning laundry. In common usage, "detergent" refers to mixtures of chemical compounds including alkylbenzenesulfonates, which are similar to soap but are less affected by "hard water." In most...

, by Procter & GambleProcter & GambleProcter & Gamble is a Fortune 500 American multinational corporation headquartered in downtown Cincinnati, Ohio and manufactures a wide range of consumer goods....

chemists working at the Ivorydale Technical Center in 1946 by adding the "builder" sodium tripolyphosphateSodium tripolyphosphateSodium triphosphate is an inorganic compound with formula Na5P3O10. It is the sodium salt of the polyphosphate penta-anion, which is the conjugate base of triphosphoric acid. It is produced on a large scale as a component of many domestic and industrial products, especially detergents...

2007

- Food dehydration technology developed at the USDA-Agricultural Research ServiceAgricultural Research ServiceThe Agricultural Research Service is the principal in-house research agency of the United States Department of Agriculture . ARS is one of four agencies in USDA's Research, Education and Economics mission area...

-Eastern Regional Research CenterEastern Regional Research CenterThe Eastern Regional Research Center is an United States Department of Agriculture laboratory center in Wyndmoor, PA. The Center researches new industrial and food uses for agricultural commodities, develops new technology to improve environmental quality, and provides technical support to...

. - Chemical Abstracts ServiceChemical Abstracts ServiceChemical Abstracts is a periodical index that provides summaries and indexes of disclosures in recently published scientific documents. Approximately 8,000 journals, technical reports, dissertations, conference proceedings, and new books, in any of 50 languages, are monitored yearly, as are patent...

. - Scotch TapeScotch TapeScotch Tape is a brand name used for certain pressure sensitive tapes manufactured by 3M as part of the company's Scotch brand.- History :The precursor to the current tapes was developed in the 1930s in Minneapolis, Minnesota by Richard Drew to seal a then-new transparent material known as...

- Jamestown, VirginiaJamestown, VirginiaJamestown was a settlement in the Colony of Virginia. Established by the Virginia Company of London as "James Fort" on May 14, 1607 , it was the first permanent English settlement in what is now the United States, following several earlier failed attempts, including the Lost Colony of Roanoke...

for the birth of the American Chemical Enterprise

2008

- The production and distribution of radioisotopes by the Oak Ridge National LaboratoryOak Ridge National LaboratoryOak Ridge National Laboratory is a multiprogram science and technology national laboratory managed for the United States Department of Energy by UT-Battelle. ORNL is the DOE's largest science and energy laboratory. ORNL is located in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, near Knoxville...

- The development of deep-tank fermentation by PfizerPfizerPfizer, Inc. is an American multinational pharmaceutical corporation. The company is based in New York City, New York with its research headquarters in Groton, Connecticut, United States...

, the technology that permitted the mass production of penicillinPenicillinPenicillin is a group of antibiotics derived from Penicillium fungi. They include penicillin G, procaine penicillin, benzathine penicillin, and penicillin V....

during World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. - Aqueous Emulsion Technology by Rohm and HaasRohm and HaasRohm and Haas Company, a Philadelphia, Pennsylvania based company, manufactures miscellaneous materials. Formerly a Fortune 500 Company, Rohm and Haas employs more than 17,000 people in 27 countries, with its last sales revenue reported as an independent company at USD 8.9 billion. On July 10,...

. This technology helped enable the Do-It-Yourself paint movement.