Arctic exploration

Encyclopedia

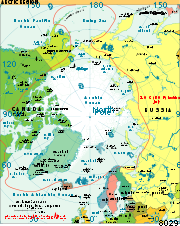

Arctic

The Arctic is a region located at the northern-most part of the Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean and parts of Canada, Russia, Greenland, the United States, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland. The Arctic region consists of a vast, ice-covered ocean, surrounded by treeless permafrost...

region of the Earth

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun, and the densest and fifth-largest of the eight planets in the Solar System. It is also the largest of the Solar System's four terrestrial planets...

. The region that surrounds the North Pole

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is, subject to the caveats explained below, defined as the point in the northern hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface...

. It refers to the historical period during which mankind has explored the region north of the Arctic Circle

Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the five major circles of latitude that mark maps of the Earth. For Epoch 2011, it is the parallel of latitude that runs north of the Equator....

. Historical records suggest that humankind have explored the northern extremes since 325 BC, when the ancient Greek

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

sailor Pytheas

Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia or Massilia , was a Greek geographer and explorer from the Greek colony, Massalia . He made a voyage of exploration to northwestern Europe at about 325 BC. He travelled around and visited a considerable part of Great Britain...

reached a frozen sea while attempting to find a source of the metal tin. Dangerous oceans and poor weather conditions often fetter explorers attempting to reach polar region

Polar region

Earth's polar regions are the areas of the globe surrounding the poles also known as frigid zones. The North Pole and South Pole being the centers, these regions are dominated by the polar ice caps, resting respectively on the Arctic Ocean and the continent of Antarctica...

s and journeying through these perils by sight, boat, and foot has proven difficult.

Ancient Greece

Some scholars believe that the first attempts to penetrate the Arctic Circle can be traced to ancient Greece and the sailor Pytheas, a contemporary of AristotleAristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

, who, in c. 325 BC, attempted to find the source of the tin that would sporadically reach the Greek colony of Massilia (now Marseille

Marseille

Marseille , known in antiquity as Massalia , is the second largest city in France, after Paris, with a population of 852,395 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Marseille extends beyond the city limits with a population of over 1,420,000 on an area of...

) on the Mediterranean

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

coast. Sailing past the Pillars of Hercules

Pillars of Hercules

The Pillars of Hercules was the phrase that was applied in Antiquity to the promontories that flank the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar. The northern Pillar is the Rock of Gibraltar in the British overseas territory of Gibraltar...

, he reached Brittany

Brittany

Brittany is a cultural and administrative region in the north-west of France. Previously a kingdom and then a duchy, Brittany was united to the Kingdom of France in 1532 as a province. Brittany has also been referred to as Less, Lesser or Little Britain...

and even Cornwall

Cornwall

Cornwall is a unitary authority and ceremonial county of England, within the United Kingdom. It is bordered to the north and west by the Celtic Sea, to the south by the English Channel, and to the east by the county of Devon, over the River Tamar. Cornwall has a population of , and covers an area of...

, eventually circumnavigating the British Isles

British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe that include the islands of Great Britain and Ireland and over six thousand smaller isles. There are two sovereign states located on the islands: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and...

. From the local population, he heard news of the mysterious land of Thule

Thule

Thule Greek: Θούλη, Thoulē), also spelled Thula, Thila, or Thyïlea, is, in classical European literature and maps, a region in the far north. Though often considered to be an island in antiquity, modern interpretations of what was meant by Thule often identify it as Norway. Other interpretations...

, even farther to the north. After six days of sailing, he reached land at the edge of a frozen sea (described by him as "curdled"), and described what is believed to be the aurora

Aurora (astronomy)

An aurora is a natural light display in the sky particularly in the high latitude regions, caused by the collision of energetic charged particles with atoms in the high altitude atmosphere...

and the midnight sun

Midnight sun

The midnight sun is a natural phenomenon occurring in summer months at latitudes north and nearby to the south of the Arctic Circle, and south and nearby to the north of the Antarctic Circle where the sun remains visible at the local midnight. Given fair weather, the sun is visible for a continuous...

. While some historians claim that this new land of Thule was the Norwegian

Norway

Norway , officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic unitary constitutional monarchy whose territory comprises the western portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula, Jan Mayen, and the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard and Bouvet Island. Norway has a total area of and a population of about 4.9 million...

coast or the Shetland Islands, based on his descriptions and the trade routes of early British sailors, it is possible that Pytheas reached as far as Iceland

Iceland

Iceland , described as the Republic of Iceland, is a Nordic and European island country in the North Atlantic Ocean, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Iceland also refers to the main island of the country, which contains almost all the population and almost all the land area. The country has a population...

.

While no one knows exactly how far Pytheas sailed, he may have been the first Westerner recorded to penetrate the Arctic Circle. Nevertheless, his tales were regarded as fantasy by later Greek and Roman

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

authorities, such as the geographer Strabo

Strabo

Strabo, also written Strabon was a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher.-Life:Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus , a city which he said was situated the approximate equivalent of 75 km from the Black Sea...

. It was impossible, according to their perception of the world, for man to survive in these 'uninhabitable reaches'.

The Middle Ages

Viking

The term Viking is customarily used to refer to the Norse explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided, traded, explored and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th century.These Norsemen used their famed longships to...

to sight Iceland was Gardar Svavarsson

Gardar Svavarsson

Garðarr Svavarsson was a Swedish man who is considered by many to be the first Scandinavian to live in Iceland, although only for one winter....

, who went off course due to harsh conditions when sailing from Norway to the Faroe Islands

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands are an island group situated between the Norwegian Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, approximately halfway between Scotland and Iceland. The Faroe Islands are a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark, along with Denmark proper and Greenland...

. This quickly led to a wave of colonization. Not all the settlers were successful however in the attempts to reach the island. In the 10th century, Gunnbjörn Ulfsson

Gunnbjörn Ulfsson

Gunnbjørn Ulfsson , name also given as Gunnbjørn Ulf-Krakuson, was the first European to sight North America....

got lost in a storm and ended up within sight of the Greenland

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

coast. His report spurred Erik the Red

Erik the Red

Erik Thorvaldsson , known as Erik the Red , is remembered in medieval and Icelandic saga sources as having founded the first Nordic settlement in Greenland. The Icelandic tradition indicates that he was born in the Jæren district of Rogaland, Norway, as the son of Thorvald Asvaldsson, he therefore...

, an outlawed chieftain, to establish a settlement there in 985. While they flourished initially, these settlements eventually foundered due to changing climatic conditions (see Little Ice Age

Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age was a period of cooling that occurred after the Medieval Warm Period . While not a true ice age, the term was introduced into the scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939...

). They are believed to have survived until around 1450.

Greenland's early settlers sailed westward, in search of better pasturage

Pasture

Pasture is land used for grazing. Pasture lands in the narrow sense are enclosed tracts of farmland, grazed by domesticated livestock, such as horses, cattle, sheep or swine. The vegetation of tended pasture, forage, consists mainly of grasses, with an interspersion of legumes and other forbs...

and hunting grounds. Modern scholars debate the precise location of the new lands of Vinland

Vinland

Vinland was the name given to an area of North America by the Norsemen, about the year 1000 CE.There is a consensus among scholars that the Vikings reached North America approximately five centuries prior to the voyages of Christopher Columbus...

, Markland

Markland

Markland is the name given to a part of shoreline in Labrador, Canada, named by Leif Eriksson when he landed in North America. The word Markland is from the Old Norse language for "forestland" or "borderland". It is described as being north of Vinland and south of Helluland...

, and Helluland

Helluland

Helluland is the name given to one of the three lands discovered by Leif Eriksson around 1000 AD on the North Atlantic coast of North America....

that they discovered.

The Scandinavian peoples

Scandinavians

Scandinavians are a group of Germanic peoples, inhabiting Scandinavia and to a lesser extent countries associated with Scandinavia, and speaking Scandinavian languages. The group includes Danes, Norwegians and Swedes, and additionally the descendants of Scandinavian settlers such as the Icelandic...

also pushed farther north into their own peninsula by land and by sea. As early as 880, the Viking Ohthere of Hålogaland rounded the Scandinavian Peninsula

Scandinavian Peninsula

The Scandinavian Peninsula is a peninsula in Northern Europe, which today covers Norway, Sweden, and most of northern Finland. Prior to the 17th and 18th centuries, large parts of the southern peninsula—including the core region of Scania from which the peninsula takes its name—were part of...

and sailed to the Kola Peninsula

Kola Peninsula

The Kola Peninsula is a peninsula in the far northwest of Russia. Constituting the bulk of the territory of Murmansk Oblast, it lies almost completely to the north of the Arctic Circle and is washed by the Barents Sea in the north and the White Sea in the east and southeast...

and the White Sea

White Sea

The White Sea is a southern inlet of the Barents Sea located on the northwest coast of Russia. It is surrounded by Karelia to the west, the Kola Peninsula to the north, and the Kanin Peninsula to the northeast. The whole of the White Sea is under Russian sovereignty and considered to be part of...

. The Pechenga Monastery

Pechenga Monastery

The Pechenga Monastery was for many centuries the northernmost monastery in the world. It was founded in 1533 at the influx of the Pechenga River into the Barents Sea, 135 km west of modern Murmansk, by St...

on the north of Kola Peninsula was founded by Russian monks in 1533; from their base at Kola

Kola (town)

Kola is a town and the administrative center of Kolsky District of Murmansk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kola and Tuloma Rivers, south of Murmansk and southwest of Severomorsk. It is the oldest town of the Kola Peninsula. Population: 11,060 ; -History:The district of Kolo...

, the Pomors

Pomors

Pomors or Pomory are Russian settlers and their descendants on the White Sea coast. It is also term of self-identification for the descendants of Russian, primarily Novgorod, settlers of Pomorye , living on the White Sea coasts and the territory whose southern border lies on a watershed which...

explored the Barents Region

Barents Region

The Barents Region is a name given, by political ambition to establish international cooperation after the fall of the Soviet Union, to the land along the coast of the Barents Sea, from Nordland in Norway to the Kola Peninsula in Russia and beyond all the way to the Ural Mountains and Novaya...

, Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen is the largest and only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipelago in Norway. Constituting the western-most bulk of the archipelago, it borders the Arctic Ocean, the Norwegian Sea and the Greenland Sea...

, and Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya , also known in Dutch as Nova Zembla and in Norwegian as , is an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean in the north of Russia and the extreme northeast of Europe, the easternmost point of Europe lying at Cape Flissingsky on the northern island...

—all of which are in the Arctic Circle. They also explored north by boat, discovering the Northern Sea Route

Northern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route is a shipping lane officially defined by Russian legislation from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean specifically running along the Russian Arctic coast from Murmansk on the Barents Sea, along Siberia, to the Bering Strait and Far East. The entire route lies in Arctic...

, as well as penetrating to the trans-Ural

Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the Ural River and northwestern Kazakhstan. Their eastern side is usually considered the natural boundary between Europe and Asia...

areas of northern Siberia

Siberia

Siberia is an extensive region constituting almost all of Northern Asia. Comprising the central and eastern portion of the Russian Federation, it was part of the Soviet Union from its beginning, as its predecessor states, the Tsardom of Russia and the Russian Empire, conquered it during the 16th...

. They then founded the settlement of Mangazeya

Mangazeya

Mangazeya was a Northwest Siberian trans-Ural trade colony and later city in the 16-17th centuries. Founded in 1600, it was situated on the Taz River, between the lower courses of the Ob and Yenisei Rivers flowing into the Arctic Ocean....

east of the Yamal Peninsula

Yamal Peninsula

The Yamal Peninsula , located in Yamal-Nenets autonomous district of northwest Siberia, Russia, extends roughly 700 km and is bordered principally by the Kara Sea, Baydaratskaya Bay on the west, and by the Gulf of Ob on the east...

in the early 16th century. In 1648 the Cossack Semyon Dezhnyov opened the now famous Bering Strait

Bering Strait

The Bering Strait , known to natives as Imakpik, is a sea strait between Cape Dezhnev, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia, the easternmost point of the Asian continent and Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, USA, the westernmost point of the North American continent, with latitude of about 65°40'N,...

between America and Asia.

Russian settler

Settler

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established permanent residence there, often to colonize the area. Settlers are generally people who take up residence on land and cultivate it, as opposed to nomads...

s and traders on the coasts of the White Sea, the Pomors, had been exploring parts of the northeast passage as early as the 11th century. By the 17th century they established a continuous sea route

Trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a single trade route contains long distance arteries which may further be connected to several smaller networks of commercial...

from Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk , formerly known as Archangel in English, is a city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina River near its exit into the White Sea in the north of European Russia. The city spreads for over along the banks of the river...

as far east as the mouth of Yenisey

Yenisei River

Yenisei , also written as Yenisey, is the largest river system flowing to the Arctic Ocean. It is the central of the three great Siberian rivers that flow into the Arctic Ocean...

. This route, known as Mangazeya seaway, after its eastern terminus, the trade depot of Mangazeya, was an early precursor to the Northern Sea Route.

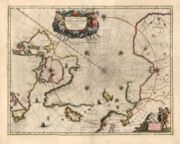

Age of Discovery

Exploration above the Arctic Circle in the RenaissanceRenaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

was driven by the rediscovery of Classical learning

Classics

Classics is the branch of the Humanities comprising the languages, literature, philosophy, history, art, archaeology and other culture of the ancient Mediterranean world ; especially Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome during Classical Antiquity Classics (sometimes encompassing Classical Studies or...

and the national quests for commercial expansion. This exploration was hampered by limits in maritime technology of the age, lack of shelf-stable food supplies, and insufficient insulation for ships' crew against extreme cold.

Renaissance advancements in cartography

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy , was a Roman citizen of Egypt who wrote in Greek. He was a mathematician, astronomer, geographer, astrologer, and poet of a single epigram in the Greek Anthology. He lived in Egypt under Roman rule, and is believed to have been born in the town of Ptolemais Hermiou in the...

's Geographia was translated into Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

, thereby introducing the concepts of latitude and longitude

Geographic coordinate system

A geographic coordinate system is a coordinate system that enables every location on the Earth to be specified by a set of numbers. The coordinates are often chosen such that one of the numbers represent vertical position, and two or three of the numbers represent horizontal position...

into Western Europe

Western Europe

Western Europe is a loose term for the collection of countries in the western most region of the European continents, though this definition is context-dependent and carries cultural and political connotations. One definition describes Western Europe as a geographic entity—the region lying in the...

. Navigators were better able to chart their positions, and the Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

an race to China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

, sparked by interest in the writings of Marco Polo

Marco Polo

Marco Polo was a Venetian merchant traveler from the Venetian Republic whose travels are recorded in Il Milione, a book which did much to introduce Europeans to Central Asia and China. He learned about trading whilst his father and uncle, Niccolò and Maffeo, travelled through Asia and apparently...

, commenced. Just two years after Columbus

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

in 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas

Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas , signed at Tordesillas , , divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between Spain and Portugal along a meridian 370 leagueswest of the Cape Verde islands...

divided the Atlantic Ocean

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

between Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

and Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

. Forced to seek other routes to the Orient

Orient

The Orient means "the East." It is a traditional designation for anything that belongs to the Eastern world or the Far East, in relation to Europe. In English it is a metonym that means various parts of Asia.- Derivation :...

, rival countries like England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, began considering the northern route over the top of the globe.

The Inventio Fortunata

Inventio Fortunata

Inventio Fortunata , "Fortunate, or fortune-making, discovery", is a lost book, probably dating from the 14th century, containing a description of the North Pole as a magnetic island surrounded by a giant whirlpool and four continents...

, a lost book

Lost work

A lost work is a document or literary work produced some time in the past of which no surviving copies are known to exist. Works may be lost to history either through the destruction of the original manuscript, or through the non-survival of any copies of the work. Deliberate destruction of works...

said to be a description of travels in the North Atlantic by an unknown Friar, describes, in a summary written by Jacobus Cnoyen but only found in a letter from Gerardus Mercator

Gerardus Mercator

thumb|right|200px|Gerardus MercatorGerardus Mercator was a cartographer, born in Rupelmonde in the Hapsburg County of Flanders, part of the Holy Roman Empire. He is remembered for the Mercator projection world map, which is named after him...

, voyages as far as the North Pole. One widely disputed claim is that two brothers from Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

, Niccolo and Antonio Zeno

Zeno brothers

The Zeno brothers, namely Nicolò and Antonio Zeno , were noted Italian navigators from Venice, living in the second half of the 14th century. They were brothers of the Venetian naval hero Carlo Zeno...

, allegedly made a map

Zeno map

The Zeno map is a map of the North Atlantic first published in 1558 in Venice by Nicolo Zeno, a descendant of Nicolo Zeno, of the Zeno brothers....

of their journeys to that region, which were published by their descendants in 1558.

The Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage is a sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific OceanPacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest of the Earth's oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic in the north to the Southern Ocean in the south, bounded by Asia and Australia in the west, and the Americas in the east.At 165.2 million square kilometres in area, this largest division of the World...

s through the Arctic Ocean. Since the discovery of the American continent

Americas

The Americas, or America , are lands in the Western hemisphere, also known as the New World. In English, the plural form the Americas is often used to refer to the landmasses of North America and South America with their associated islands and regions, while the singular form America is primarily...

was the product of the search for a route to Asia, exploration around the northern edge of North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

continued for the Northwest Passage.

John Cabot

John Cabot

John Cabot was an Italian navigator and explorer whose 1497 discovery of parts of North America is commonly held to have been the first European encounter with the continent of North America since the Norse Vikings in the eleventh century...

's initial failure in 1497 to find a Northwest Passage across the Atlantic led the British to seek an alternative route to the east.

Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier was a French explorer of Breton origin who claimed what is now Canada for France. He was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of the Saint Lawrence River, which he named "The Country of Canadas", after the Iroquois names for the two big...

's discovery of the mouth of the Saint Lawrence River

Saint Lawrence River

The Saint Lawrence is a large river flowing approximately from southwest to northeast in the middle latitudes of North America, connecting the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean. It is the primary drainage conveyor of the Great Lakes Basin...

. Martin Frobisher

Martin Frobisher

Sir Martin Frobisher was an English seaman who made three voyages to the New World to look for the Northwest Passage...

had formed a resolution to undertake the challenge of forging a trade route from England westward to India. In 1576 - 1578, he took three trips to what is now the Canadian Arctic

Northern Canada

Northern Canada, colloquially the North, is the vast northernmost region of Canada variously defined by geography and politics. Politically, the term refers to the three territories of Canada: Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut...

in order to find the passage. Frobisher Bay

Frobisher Bay

Frobisher Bay is a relatively large inlet of the Labrador Sea in the Qikiqtaaluk Region of Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the southeastern corner of Baffin Island...

, which he discovered, is named after him. In July 1583, Sir Humphrey Gilbert

Humphrey Gilbert

Sir Humphrey Gilbert of Devon in England was a half-brother of Sir Walter Raleigh. Adventurer, explorer, member of parliament, and soldier, he served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth and was a pioneer of English colonization in North America and the Plantations of Ireland.-Early life:Gilbert...

, who had written a treatise on the discovery of the passage and was a backer of Frobisher's, claimed the territory of Newfoundland

Newfoundland Colony

Newfoundland Colony was England's first permanent colony in the New World.From 1610 to 1728, Proprietary Governors were appointed to establish colonial settlements on the island. John Guy was governor of the first settlement at Cuper's Cove. Other settlements were Bristol's Hope, Renews, New...

for the English crown. On August 8, 1585, under the employ of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

the English explorer John Davis

John Davis (English explorer)

John Davis , was one of the chief English navigators and explorers under Elizabeth I, especially in Polar regions and in the Far East.-Early life:...

entered Cumberland Sound

Cumberland Sound

Cumberland Sound is an Arctic waterway in Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is a western arm of the Labrador Sea located between Baffin Island's Hall Peninsula and the Cumberland Peninsula...

, Baffin Island

Baffin Island

Baffin Island in the Canadian territory of Nunavut is the largest island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, the largest island in Canada and the fifth largest island in the world. Its area is and its population is about 11,000...

. Davis rounded Greenland before dividing his four ships into separate expeditions to search for a passage westward. Though he was unable to pass through the icy Arctic waters, he reported to his sponsors that the passage they sought is "a matter nothing doubtfull [sic]," and secured support for two additional expeditions, reaching as far as Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay , sometimes called Hudson's Bay, is a large body of saltwater in northeastern Canada. It drains a very large area, about , that includes parts of Ontario, Quebec, Saskatchewan, Alberta, most of Manitoba, southeastern Nunavut, as well as parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota,...

. Though England's efforts were interrupted in 1587 because of Anglo-Spanish War, Davis's favorable reports on the region and its people would inspire explorers in the coming century.

The Northeast Passage

Shipping

Shipping has multiple meanings. It can be a physical process of transporting commodities and merchandise goods and cargo, by land, air, and sea. It also can describe the movement of objects by ship.Land or "ground" shipping can be by train or by truck...

lane from the Barent Sea to the Bering Strait along the Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

n northern coast as currently officially defined by Russian Federation law; before the beginning of the 20th century it was known as the Northeast Passage.

The idea to explore this region was initially economic, and was first put forward by Russian diplomat Dmitry Gerasimov

Dmitry Gerasimov

Dmitry Gerasimov , was a Russian translator, diplomat and philologist; he also provided some of the earliest information on Muscovy to Renaissance scholars such as Paolo Giovio and Sigismund von Herberstein....

in 1525. The vast majority of the route lies in Arctic waters and parts are only free of ice for two months per year, making it a very perilous journey.

In the mid-16th century, John Cabot's son Sebastian

Sebastian Cabot (explorer)

Sebastian Cabot was an explorer, born in the Venetian Republic.-Origins:...

helped organize just such an expedition, led by Sir Hugh Willoughby and Richard Chancellor

Richard Chancellor

Richard Chancellor was an English explorer and navigator; the first to penetrate to the White Sea and establish relations with Russia....

. Willoughby's crew was shipwrecked off the Kola Peninsula, where they eventually died of scurvy

Scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a deficiency of vitamin C, which is required for the synthesis of collagen in humans. The chemical name for vitamin C, ascorbic acid, is derived from the Latin name of scurvy, scorbutus, which also provides the adjective scorbutic...

. Chancellor and his crew made it to the mouth of the Dvina River, where they were met by a delegation from the Tsar

Tsar

Tsar is a title used to designate certain European Slavic monarchs or supreme rulers. As a system of government in the Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire, it is known as Tsarist autocracy, or Tsarism...

, Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV of Russia

Ivan IV Vasilyevich , known in English as Ivan the Terrible , was Grand Prince of Moscow from 1533 until his death. His long reign saw the conquest of the Khanates of Kazan, Astrakhan, and Siberia, transforming Russia into a multiethnic and multiconfessional state spanning almost one billion acres,...

. Brought back to Moscow

Moscow

Moscow is the capital, the most populous city, and the most populous federal subject of Russia. The city is a major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation centre of Russia and the continent...

, he launched the Muscovy Company

Muscovy Company

The Muscovy Company , was a trading company chartered in 1555. It was the first major chartered joint stock company, the precursor of the type of business that would soon flourish in England, and became closely associated with such famous names as Henry Hudson and William Baffin...

, promoting trade between England and Russia. This diplomatic course allowed British Ambassadors such as Sir Francis Cherry

Francis Cherry (diplomat)

Sir Francis Cherry was the English ambassador to the Court of Russia from April 1598 to 23 March 1599.Queen Elizabeth knighted Cherry “for faithful and gallant service” at Chatham on 4 July 1604. He became the founder of the Cherry line at Camberwell....

the opportunity to consolidate geographic information developed by Russian merchants into maps for British exploration of the region. Some years later, Steven Borough

Steven Borough

Steven Borough , English navigator, was born at Northam, Devon.In 1553 he took part in the expedition which was dispatched from the Thames under Sir Hugh Willoughby to look for a northern passage to Cathay and India, serving as master of the Edward Bonaventure, on which Richard Chancellor sailed as...

, the master of Chancellor's ship, made it as far as the Kara Sea

Kara Sea

The Kara Sea is part of the Arctic Ocean north of Siberia. It is separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya....

, when he was forced to turn back because of icy conditions.

Western parts of the passage were simultaneously being explored by Northern European countries like England, the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway, looking for an alternative seaway to China and India. Although these expeditions failed, new coasts and islands were discovered. Most notable is the 1596 expedition led by Dutch navigator Willem Barentsz who discovered Spitsbergen and Bear Island.

Fearing English and Dutch penetration into Siberia, Russia closed the Mangazeya seaway in 1619. Pomor activity in Northern Asia declined and the bulk of exploration in the 17th century was carried out by Siberian Cossacks, sailing from one river mouth to another in their Arctic-worthy kochs

Koch (boat)

The Koch was a special type of small one or two mast wooden sailing ships designed and used in Russia for transpolar voyages in ice conditions of the Arctic seas, popular among the Pomors....

. In 1648 the most famous of these expeditions, led by Fedot Alekseev and Semyon Dezhnev

Semyon Dezhnev

Semyon Ivanovich Dezhnyov was a Russian explorer of Siberia and the first European to sail through the Bering Strait. In 1648 he sailed from the Kolyma River on the Arctic Ocean to the Anadyr River on the Pacific...

, sailed east from the mouth of Kolyma

Kolyma

The Kolyma region is located in the far north-eastern area of Russia in what is commonly known as Siberia but is actually part of the Russian Far East. It is bounded by the East Siberian Sea and the Arctic Ocean in the north and the Sea of Okhotsk to the south...

to the Pacific and doubled the Chukchi Peninsula

Chukchi Peninsula

The Chukchi Peninsula, Chukotka Peninsula or Chukotski Peninsula , at about 66° N 172° W, is the northeastern extremity of Asia. Its eastern end is at Cape Dezhnev near the village of Uelen. It is bordered by the Chukchi Sea to the north, the Bering Sea to the south, and the Bering Strait to the...

, thus proving that there was no land connection between Asia and North America. Eighty years after Dezhnev, in 1728, another Russian explorer, Danish-born Vitus Bering

Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering Vitus Jonassen Bering Vitus Jonassen Bering (also, less correNavy]], a captain-komandor known among the Russian sailors as Ivan Ivanovich. He is noted for being the first European to discover Alaska and its Aleutian Islands...

on Sviatoy Gavriil made a similar voyage in reverse, starting in Kamchatka

Kamchatka Peninsula

The Kamchatka Peninsula is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of . It lies between the Pacific Ocean to the east and the Sea of Okhotsk to the west...

and going north to the passage that now bears his name (Bering Strait). It was Bering who gave their current names to Diomede Islands

Diomede Islands

The Diomede Islands , also known in Russia as Gvozdev Islands , consist of two rocky, tuya-like islands:* The U.S. island of Little Diomede or, in its native language, Ignaluk , and* The Russian island of Big Diomede , also known as Imaqliq,...

, discovered and first described by Dezhnev.

Modern exploration

In the first half of the 19th century, parts of the Northwest Passage were explored separately by a number of different expeditions, including those by John RossJohn Ross (Arctic explorer)

Sir John Ross, CB, was a Scottish rear admiral and Arctic explorer.Ross was the son of the Rev. Andrew Ross, minister of Inch, near Stranraer in Scotland. In 1786, aged only nine, he joined the Royal Navy as an apprentice. He served in the Mediterranean until 1789 and then in the English Channel...

, William Edward Parry

William Edward Parry

Sir William Edward Parry was an English rear-admiral and Arctic explorer, who in 1827 attempted one of the earliest expeditions to the North Pole...

, James Clark Ross

James Clark Ross

Sir James Clark Ross , was a British naval officer and explorer. He explored the Arctic with his uncle Sir John Ross and Sir William Parry, and later led his own expedition to Antarctica.-Arctic explorer:...

; and overland expeditions led by John Franklin

John Franklin

Rear-Admiral Sir John Franklin KCH FRGS RN was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. Franklin also served as governor of Tasmania for several years. In his last expedition, he disappeared while attempting to chart and navigate a section of the Northwest Passage in the Canadian Arctic...

, George Back

George Back

Admiral Sir George Back FRS was a British naval officer, explorer of the Canadian Arctic , naturalist and artist.-Career:...

, Peter Warren Dease

Peter Warren Dease

Peter Warren Dease was a Canadian fur trader and arctic explorer.-Early life:Peter Warren Dease was born at Michilimackinac on January 1, 1788, the fourth son of Dr. John Dease, captain and deputy agent of Indian Affairs, and Jane French, Catholic Mohawk from Caughnawaga...

, Thomas Simpson

Thomas Simpson (explorer)

Thomas Simpson , Hudson's Bay Company agent and personal secretary for Hudson Bay governor Sir George Simpson, and arctic explorer.-Early life:...

, and John Rae

John Rae (explorer)

John Rae was a Scottish doctor who explored Northern Canada, surveyed parts of the Northwest Passage and reported the fate of the Franklin Expedition....

. Sir Robert McClure

Robert McClure

Sir Robert John Le Mesurier McClure was an Irish explorer of the Arctic.In 1854, he was the first to transit the Northwest Passage , as well as the first to circumnavigate the Americas.-Early life and career:He was born at Wexford, in Ireland, the posthumous son of one of Abercrombie's captains,...

was credited with the discovery of the Northwest Passage

McClure Arctic Expedition

The McClure Arctic Expedition of 1850, among numerous British search efforts to determine the fate of the Franklin's lost expedition, is distinguished as the voyage during which Robert McClure became the first person to confirm and transit the Northwest Passage by a combination of sea travel and...

by sea in 1851 when he looked across M'Clure Strait from Banks Island

Banks Island

One of the larger members of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, Banks Island is situated in the Inuvik Region of the Northwest Territories, Canada. It is separated from Victoria Island to its east by the Prince of Wales Strait and from the mainland by Amundsen Gulf to its south. The Beaufort Sea lies...

and viewed Melville Island. However, the strait was blocked by young ice at this point in the season, and not navigable to ships. The only usable route, linking the entrances of Lancaster Sound

Lancaster Sound

Lancaster Sound is a body of water in Qikiqtaaluk, Nunavut, Canada. It is located between Devon Island and Baffin Island, forming the eastern portion of the Northwest Passage. East of the sound lies Baffin Bay; to the west lies Viscount Melville Sound...

and Dolphin and Union Strait

Dolphin and Union Strait

Dolphin and Union Strait lies in both the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, Canada, between the mainland and Victoria Island. It links Amundsen Gulf, lying to the northwest, with Coronation Gulf, lying to the southeast...

was first used by John Rae in 1851. Rae used a pragmatic approach of traveling by land on foot and dog sled

Dog sled

A dog sled is a sled pulled by one or more sled dogs used to travel over ice and through snow. Numerous types of sleds are used, depending on their function. They can be used for dog sled racing.-History:...

, and typically employed less than ten people in his exploration parties.

The Northwest Passage was not completely conquered by sea until 1906, when the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen

Roald Amundsen

Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He led the first Antarctic expedition to reach the South Pole between 1910 and 1912 and he was the first person to reach both the North and South Poles. He is also known as the first to traverse the Northwest Passage....

, who had sailed just in time to escape creditors seeking to stop the expedition, completed a three-year voyage in the converted 47-ton herring boat Gjøa

Gjøa

Gjøa was the first vessel to transit the Northwest Passage. With a crew of six, Roald Amundsen traversed the passage in a three year journey, finishing in 1906.- History :- Construction :...

. At the end of this trip, he walked into the city of Eagle, Alaska

Eagle, Alaska

Eagle is a city located along the United States-Canada border in the Southeast Fairbanks Census Area, Alaska, United States. It includes Eagle Historic District, a U.S. National Historic Landmark. The population was 129 at the 2000 census...

, and sent a telegram announcing his success. His route was not commercially practical; in addition to the time taken, some of the waterways were extremely shallow.

The North Pole

Robert Peary

Robert Edwin Peary, Sr. was an American explorer who claimed to have been the first person, on April 6, 1909, to reach the geographic North Pole...

claimed to be the first person in recorded history to reach the North Pole (although whether he actually reached the Pole is doubted by some). He traveled with the aid of dogsleds and three separate support crews who turned back at successive intervals before reaching the Pole. Many modern explorers, including Olympic skiers using modern equipment, contend that Peary could not have reached the pole on foot in the time he claimed. In 2005 British explorer Tom Avery

Tom Avery

Thomas Avery is a British explorer and author. He gained notoriety for his record-breaking journey to the South Pole in 2002. He has travelled by foot to both the North and South Poles.-Early life:...

, with four colleagues, completed a trek to the pole in 36 days, 22 hours and 11 minutes using 16 husky dogs

Husky

Husky is a general name for a type of dog originally used to pull sleds in northern regions, differentiated from other sled dog types by their fast hard pulling style...

, and pulling two sledges which were replicas of those used by Peary. Some believe Avery's expedition has vindicated Peary, showing that Peary's speeds were not so impossible after all, since Avery's time was some four hours faster than Peary's claim. However a close examination of Avery's speeds only casts more doubt on Peary's claim: while Peary claimed to have made good an incredible 135 nmi (250 km; 155.4 mi) in his final five days, Avery managed only 71. Indeed, Avery never exceeded 90 nautical miles (166.7 km) made good in any five-day stretch. Further, Avery had the luxury of an airlift back to shore, and so had lightly loaded sledges in his final five days, while Peary was loaded down with all food and supplies needed for his return. Avery was able to equal Peary's 37-day total time only because Peary spent five days encamped by a big lead, making no progress at all.

A number of previous expeditions set out with the intention of reaching the North Pole but did not succeed; that of British naval officer William Edward Parry, in 1827, the American Polaris expedition

Polaris expedition

The Polaris expedition was led by the American Charles Francis Hall, who intended it to be the first expedition to reach the North Pole. Sponsored by the United States government, it was one of the first serious attempts at the Pole, after that of British naval officer William Edward Parry, who in...

in 1871, and Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Nansen

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen was a Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In his youth a champion skier and ice skater, he led the team that made the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, and won international fame after reaching a...

in 1895. American Frederick Cook

Frederick Cook

Frederick Albert Cook was an American explorer and physician, noted for his claim of having reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908. This would have been a year before April 6, 1909, the date claimed by Robert Peary....

claimed to have reached the North Pole in 1908, but this has not been widely accepted.

Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen observed the Pole on May 12, 1926, accompanied by his American sponsor Lincoln Ellsworth

Lincoln Ellsworth

Lincoln Ellsworth was an arctic explorer from the United States.-Birth:He was born on May 12, 1880 to James Ellsworth and Eva Frances Butler in Chicago, Illinois...

from the airship

Airship

An airship or dirigible is a type of aerostat or "lighter-than-air aircraft" that can be steered and propelled through the air using rudders and propellers or other thrust mechanisms...

Norge

Norge (airship)

The Norge was a semi-rigid Italian-built airship that carried out what many consider the first verified overflight of the North Pole on May 12, 1926. It was also the first aircraft to fly over the polar ice cap between Europe and America...

, the first undisputed sighting of the Pole. Norge was designed and piloted by the Italian

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

Umberto Nobile

Umberto Nobile

Umberto Nobile was an Italian aeronautical engineer and Arctic explorer. Nobile was a developer and promoter of semi-rigid airships during the Golden Age of Aviation between the two World Wars...

, who overflew the Pole a second time on May 24, 1928.

The first people to have without doubt walked on the North Pole were the Soviet party of 1948 under the command of Alexander Kuznetsov, who landed their aircraft nearby and walked to the pole.

On August 3, 1958, the US submarine Nautilus

USS Nautilus (SSN-571)

USS Nautilus is the world's first operational nuclear-powered submarine. She was the first vessel to complete a submerged transit beneath the North Pole on August 3, 1958...

reached the North Pole without surfacing. It then proceeded to travel under the entire Polar ice cap

Polar ice cap

A polar ice cap is a high latitude region of a planet or natural satellite that is covered in ice. There are no requirements with respect to size or composition for a body of ice to be termed a polar ice cap, nor any geological requirement for it to be over land; only that it must be a body of...

. On March 17, 1959 the USS Skate

USS Skate (SSN-578)

USS Skate , the third submarine of the United States Navy named for the skate, a type of ray, was the lead ship of the Skate class of nuclear submarines...

surfaced on the North Pole and dispersed the ashes of explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins

Hubert Wilkins

Sir Hubert Wilkins MC & Bar was an Australian polar explorer, ornithologist, pilot, soldier, geographer and photographer.-Early life:...

. These journeys were part of military explorations stimulated by the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

context.

On April 19, 1968, Ralph Plaisted

Ralph Plaisted

Ralph Plaisted and his three companions, Walt Pederson, Gerry Pitzl and Jean-Luc Bombardier, are regarded by most polar authorities to be the first to succeed in a surface traverse across the ice to the North Pole on 19 April 1968, making the first confirmed surface conquest of the Pole.Plaisted...

reached the North Pole via snowmobile

Snowmobile

A snowmobile, also known in some places as a snowmachine, or sled,is a land vehicle for winter travel on snow. Designed to be operated on snow and ice, they require no road or trail. Design variations enable some machines to operate in deep snow or forests; most are used on open terrain, including...

, the first surface traveler known with certainty to have done so. His position was verified independently by a US Air Force

United States Air Force

The United States Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the American uniformed services. Initially part of the United States Army, the USAF was formed as a separate branch of the military on September 18, 1947 under the National Security Act of...

meteorological overflight. In 1969 Wally Herbert

Wally Herbert

Sir Walter William "Wally" Herbert was a British polar explorer, writer and artist. In 1969 he became the first man to walk undisputed to the North Pole, on the 60th anniversary of Robert Peary's famous, but disputed, expedition...

, on foot and by dog sled, became the first man to reach the North Pole on muscle power alone, on the 60th anniversary of Robert Peary's famous but disputed expedition.

The first persons to reach the North Pole on foot (or skis) and return with no outside help, no dogs, air planes, or re-supplies were Richard Weber

Richard Weber

Richard Weber is a Canadian Arctic and polar adventurer. From 1978 to 2006, he organized and lead more than 45 Arctic expeditions. Richard is the only person to have completed six full North Pole expeditions...

(Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

) and Misha Malakhov (Russia) in 1995. No one has completed this journey since.

U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Joseph O. Fletcher

Joseph O. Fletcher

Joseph Otis Fletcher was an American Air Force pilot and polar explorer.-Biography:Born outside of Ryegate, Montana, the family moved to Oklahoma during the Dust Bowl. Fletcher started studying at the University of Oklahoma and then continued his studies in meteorology at the MIT. After...

and Lieutenant William Pershing Benedict

William Pershing Benedict

Lieutenant Colonel William Pershing Benedict was an American pilot from California. He is best known for having made the first aircraft landing at the North Pole.-Early life:...

landed a plane at the Pole on May 3, 1952, accompanied by the scientist Albert P. Crary

Albert P. Crary

Albert Paddock Crary , was a pioneer polar geophysicist and glaciologist. He made it to the North and then to the South Pole on February 12, 1961 as the leader of a team of eight. The south pole expedition had set out from McMurdo Station on December 10, 1960, using three Snowcats with trailers...

.

On April 26, 2009, Vassily Elagin, Afanassi Makovnev, Vladimir Obikhod, Sergey Larin, Alexey Ushakov, Alexey Shkrabkin and Nikolay Nikulshin after 38 days and over 2000 km (1,242.7 mi) (starting from Sredniy Island, Severnaya Zemlya

Severnaya Zemlya

Severnaya Zemlya is an archipelago in the Russian high Arctic at around . It is located off mainland Siberia's Taymyr Peninsula across the Vilkitsky Strait...

) drove two Russian built cars "Yemelya-1" and "Yemelya-2" to the North Pole.

See also

- Farthest NorthFarthest NorthFarthest North describes the most northerly latitude reached by explorers before the conquest of the North Pole rendered the expression obsolete...

- List of polar explorers

- List of Arctic expeditions

- List of Arctic exploration vessels

- List of firsts in the Geographic North Pole

- Great Northern ExpeditionGreat Northern ExpeditionThe Great Northern Expedition or Second Kamchatka expedition was one of the largest organised exploration enterprises in history, resulting in mapping of the most of the Arctic coast of Siberia and some parts of the North America coastline, greatly reducing the "white areas" on the maps...

- List of Antarctic expeditions

- Heroic Age of Antarctic ExplorationHeroic Age of Antarctic ExplorationThe Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration defines an era which extended from the end of the 19th century to the early 1920s. During this 25-year period the Antarctic continent became the focus of an international effort which resulted in intensive scientific and geographical exploration, sixteen...

- History of AntarcticaHistory of AntarcticaThe history of Antarctica emerges from early Western theories of a vast continent, known as Terra Australis, believed to exist in the far south of the globe...

- History of research shipsHistory of research shipsThe research ship had origins in the early voyages of exploration. By the time of James Cook's Endeavour, the essentials of what today we would call a research ship are clearly apparent. In 1766, the Royal Society hired Cook to travel to the Pacific Ocean to observe and record the transit of Venus...

- List of Russian explorers

- Timeline of European explorationTimeline of European explorationThe following timeline covers European exploration from 1418 to 1948.The fifteenth century witnessed the rounding of the feared Cape Bojador and Portuguese exploration of the west coast of Africa, while in the last decade of the century the Spanish sent expeditions to the New World, focusing on...

External links

- To the North Pole - slideshow by Life magazine

- Freeze Frame - collection of historic polar images at the Scott Polar Research Institute, University of CambridgeUniversity of CambridgeThe University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

. Represents the history of British exploration and science in the Arctic and Antarctic during the period 1845-1960. Also covers early European and international collaborative ventures in the polar regions, portraiture, shipping and aerial reconnaissance. - "Why Go To The Arctic?", January 1931, Popular Mechanics