Cyathus

Encyclopedia

Cyathus is a genus

of fungi in the Nidulariaceae

, a family

collectively known as the bird's nest fungi. They are given this name since they resemble tiny bird's nests filled with "eggs", structures large enough to have been mistaken in the past for seeds. However, these are now known to be reproductive structures containing spore

s. The "eggs", or peridioles, are firmly attached to the inner surface of this fruiting body by an elastic cord of mycelia known as a funiculus. The 45 species are widely distributed throughout the world and some are found in most countries, although a few exist in only one or two locales. Cyathus stercoreus

is considered endangered in a number of European countries. Species of Cyathus are also known as splash cups, which refers to the fact that falling raindrops can knock the peridioles out of the open-cup fruiting body. The internal and external surfaces of this cup may be ridged longitudinally (referred to as plicate or striate); this is one example of a taxonomic

characteristic that has traditionally served to distinguish between species.

Generally considered inedible, Cyathus species are saprobic, since they obtain nutrients from decomposing organic matter

. They usually grow on decaying wood or woody debris, on cow and horse dung, or directly on humus-rich soil. The life cycle

of this genus allows it to reproduce both sexually, with meiosis

, and asexually via spores. Several Cyathus species produce bioactive

compounds, some with medicinal properties, and several lignin

-degrading enzyme

s from the genus may be useful in bioremediation

and agriculture

. Phylogenetic analysis is providing new insights into the evolution

ary relationships between the various species in Cyathus, and has cast doubt on the validity of the older classification systems that are based on traditional taxonomic characteristics.

; the generic name Cyathus is Latin, but originally derived from the Ancient Greek

word κύαθος, meaning "cup". The structure and biology of the genus Cyathus was better known by the mid-19th century, starting with the appearance of an 1842 paper by J. Schmitz, and two years later, a monograph

by the brothers Louis René

and Charles Tulasne

. The work of the Tulasnes was thorough and accurate, and was highly regarded by later researchers. Subsequently, monographs were written in 1902 by Violet S. White (American species), Curtis Gates Lloyd

in 1906, Gordon Herriot Cunningham

in 1924 (New Zealand species), and Harold J. Brodie

in 1975.

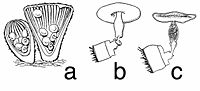

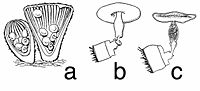

) that are vase-, trumpet- or urn-shaped with dimensions of 4–8 mm wide by 7–18 mm tall. Fruiting bodies are brown to gray-brown in color, and covered with small hair-like structures on the outer surface. Some species, like C. striatus and C. setosus, have conspicuous bristles called setae on the rim of the cup. The fruiting body is often expanded at the base into a solid rounded mass of hypha

e called an emplacement, which typically becomes tangled and entwined with small fragments of the underlying growing surface, improving its stability and helping it from being knocked over by rain. Immature fruiting bodies have a whitish membrane, an epiphragm, that covers the peridium

Immature fruiting bodies have a whitish membrane, an epiphragm, that covers the peridium

opening when young, but eventually dehisces

, breaking open during maturation. Viewed with a microscope, the peridium of Cyathus species is made of three distinct layers—the endo-, meso-, and ectoperidium, referring to the inner, middle, and outer layers respectively. While the surface of the ectoperidium in Cyathus is usually hairy, the endoperidial surface is smooth, and depending on the species, may have longitudinal grooves (striations).

Because the basic fruiting body structure in all genera

of the Nidulariaceae family is essentially similar, Cyathus may be readily confused with species of Nidula

or Crucibulum

, especially older, weathered specimens of Cyathus that may have the hairy ectoperidium worn off. It distinguished from Nidula by the presence of a funiculus, a cord of hyphae attaching the peridiole to the endoperidium. Cyathus differs from genus Crucibulum by having a distinct three-layered wall and a more intricate funiculus.

Derived from the Greek word peridion, meaning "small leather pouch", the peridiole is the "egg" of the bird's nest. It is a mass of basidiospores and gleba

Derived from the Greek word peridion, meaning "small leather pouch", the peridiole is the "egg" of the bird's nest. It is a mass of basidiospores and gleba

l tissue enclosed by a hard and waxy outer shell. The shape may be described as lenticular—like a biconvex lens—and depending on the species, may range in color from whitish to grayish to black. The interior chamber of the peridiole contains a hymenium

that is made of basidia, sterile (non-reproductive) structures, and spores. In young, freshly opened fruiting bodies, the peridioles lie in a clear gelatinous substance which soon dries.

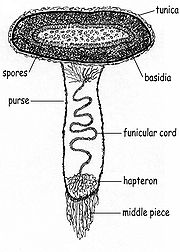

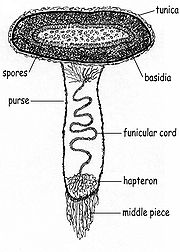

Peridioles are attached to the fruiting body by a funiculus, a complex structure of hypha

e that may be differentiated into three regions: the basal piece, which attaches it to the inner wall of the peridium, the middle piece, and an upper sheath, called the purse, connected to the lower surface of the peridiole. In the purse and middle piece is a coiled thread of interwoven hyphae called the funicular cord, attached at one end to the peridiole and at the other end to an entangled mass of hyphae called the hapteron. In some species the peridioles may be covered by a tunica, a thin white membrane (particularly evident in C. striatus

and C. crassimurus).

Spore

s typically have an elliptical or roughly spherical shape, and are thick-walled, hyaline

or light yellow-brown in color, with dimensions of 5–15 by 5–8 µm

.

, C. costatus, C. fimicola, and C. pygmaeus. Some species have been collected on woody material like dead herbaceous

stems, the empty shells or husk

s of nuts, or on fibrous material like coconut

, jute

, or hemp

fiber woven into matting, sacks or cloth. In nature, fruiting bodies are usually found in moist, partly shaded sites, such as the edges of woods on trails, or around lighted openings in forests. They are less frequently found growing in dense vegetation and deep mosses, as these environments would interfere with the dispersal of peridioles by falling drops of water. The appearance of fruiting bodies is largely dependent upon features of the immediate growing environment; specifically, optimum conditions of temperature, moisture, and nutrient availability are more important factors for fruiting rather than the broad geographical area in which the fungi are located, or the season. Examples of the ability of Cyathus to thrive in somewhat inhospitable environments are provided by C. striatus and C. stercoreus, which can survive the drought and cold of winter in temperate North America, and the species C. helenae

, which has been found growing on dead alpine plants at an altitude of 7000 feet (2,133.6 m).

In general, species of Cyathus have a worldwide distribution

In general, species of Cyathus have a worldwide distribution

, but are only rarely found in the arctic

and subarctic

. One of the best known species, C. striatus

has a circumpolar

distribution and is commonly found throughout temperate

locations, while the morphologically similar C. poeppigii is widely spread in tropical areas, rarely in the subtropics

, and never in temperate regions. The majority of species are native to warm climates. For example, although 20 different species have been reported from the United States and Canada, only 8 are commonly encountered; on the other hand, 25 species may be regularly found in the West Indies, and the Hawaiian Islands

alone have 11 species. Some species seem to be endemic to certain regions, such as C. novae-zeelandiae found in New Zealand

, or C. crassimurus, found only in Hawaii; however, this apparent endemism may just be a result of a lack of collections, rather than a difference in the habitat that constitutes a barrier to spread. Although widespread in the tropics and most of the temperate world, C. stercoreus is only rarely found in Europe; this has resulted in its appearance on a number of Red Lists. For example, it is considered endangered in Bulgaria

, Denmark

, and Montenegro

, and "near threatened" in Great Britain

.

spores), or sexually (with meiosis

). Like other wood-decay fungi, this life cycle may be considered as two functionally different phases: the vegetative stage for the spread of mycelia, and the reproductive stage for the establishment of spore-producing structures, the fruiting bodies.

The vegetative stage encompasses those phases of the life cycle involved with the germination, spread, and survival of the mycelium. Spores germinate under suitable conditions of moisture and temperature, and grow into branching filaments called hypha

e, pushing out like roots into the rotting wood. These hyphae are homokaryotic

, containing a single nucleus in each compartment; they increase in length by adding cell-wall material to a growing tip. As these tips expand and spread to produce new growing points, a network called the mycelium develops. Mycelial growth occurs by mitosis

and the synthesis of hyphal biomass. When two homokaryotic hyphae of different mating compatibility groups

fuse with one another, they form a dikaryotic

mycelia in a process called plasmogamy

. Prerequisites for mycelial survival and colonization a substrate (like rotting wood) include suitable humidity and nutrient availability. The majority of Cyathus species are saprobic, so mycelial growth in rotting wood is made possible by the secretion of enzyme

s that break down complex polysaccharide

s (such as cellulose

and lignin

) into simple sugars that can be used as nutrients.

After a period of time and under the appropriate environmental conditions, the dikaryotic mycelia may enter the reproductive stage of the life cycle. Fruiting body formation is influenced by external factors such as season (which affects temperature and air humidity), nutrients and light. As fruiting bodies develop they produce peridioles containing the basidia upon which new basidiospores are made. Young basidia contain a pair of haploid sexually compatible nuclei which fuse, and the resulting diploid fusion nucleus undergoes meiosis to produce basidiospore

s, each containing a single haploid nucleus. The dikaryotic mycelia from which the fruiting bodies are produced is long lasting, and will continue to produce successive generations of fruiting bodies as long as the environmental conditions are favorable.

The development of Cyathus fruiting bodies has been studied in laboratory culture; Cyathus stercoreus has been used most often for these studies due to the ease with which it may be grown experimentally. In 1958, E. Garnett first demonstrated that the development and form of the fruiting bodies is at least partially dependent on the intensity of light it receives during development. For example, exposure of the heterokaryotic

The development of Cyathus fruiting bodies has been studied in laboratory culture; Cyathus stercoreus has been used most often for these studies due to the ease with which it may be grown experimentally. In 1958, E. Garnett first demonstrated that the development and form of the fruiting bodies is at least partially dependent on the intensity of light it receives during development. For example, exposure of the heterokaryotic

mycelium

to light is required for fruiting to occur, and furthermore, this light needs to be at a wavelength

of less than 530 nm. Continuous light is not required for fruiting body development; after the mycelium has reached a certain stage of maturity, only a brief exposure to light is necessary, and fruiting bodies will form if even subsequently kept in the dark. Lu suggested in 1965 that certain growing conditions—such as a shortage in available nutrients—shifts the fungus' metabolism

to produce a hypothetical "photoreceptive precursor" that enables the growth of the fruiting bodies to be stimulated and affected by light. The fungi is also positively phototrophic

, that is, it will orient its fruiting bodies in the direction of the light source. The time required to develop fruiting bodies depends on a number of factors, such as the temperature, or the availability and type of nutrients, but in general "most species that do fruit in laboratory culture do so best at about 25 °C, in from 18 to 40 days."

, species of Cyathus have their spores dispersed when water falls into the fruiting body. The fruiting body is shaped so that the kinetic energy of a fallen raindrop is redirected upward and slightly outward by the angle of the cup wall, which is consistently 70–75° with the horizontal. The action ejects the peridioles out of the so-called "splash cup", where it may break and spread the spores within, or be eaten and dispersed by animals after passing through the digestive tract. This method of spore dispersal in the Nidulariaceae was tested experimentally by George Willard Martin in 1924, and later elaborated by Arthur Henry Reginald Buller, who used Cyathus striatus

as the model species to experimentally investigate the phenomenon. Buller's major conclusions about spore dispersal were later summarized by his graduate student Harold J Brodie, with whom he conducted several of these splash cup experiments:

Although it has not been shown experimentally if the spores can survive the passage through an animal's digestive tract, the regular presence of Cyathus on cow or horse manure strongly suggest that this is true. Alternatively, the hard outer casing of peridioles ejected from splash cups may simply disintegrate over time, eventually releasing the spores within.

, C. africanus and C. earlei. Several of the cyathins (especially cyathins B3 and C3), including striatin compounds from C. striatus, show strong antibiotic

activity. Cyathane diterpenoids also stimulate Nerve Growth Factor

synthesis, and have the potential to be developed into therapeutic agents for neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease

. Compounds named cyathuscavins, isolated from the mycelial liquid culture of C. stercoreus, have significant antioxidant

activity, as do the compounds known as cyathusals, also from C. stercoreus. Various sesquiterpene

compounds have also been identified in C. bulleri, including cybrodol (derived from humulene

), nidulol, and bullerone.

Various Cyathus species have antifungal activity against human pathogens such as Aspergillus fumigatus

, Candida albicans

and Cryptococcus neoformans

. Extracts of C. striatus have inhibitory effects on NF-κB, a transcription factor

responsible for regulating the expression

of several genes involved in the immune system

, inflammation

, and cell death

.

s or other substances considered toxic to humans. Brodie goes on to note that two Cyathus species have been used by native peoples as an aphrodisiac

, or to stimulate fertility

: C. limbatus in Colombia

, and C. microsporus in Guadeloupe

. Whether these species have any actual effect on human physiology

is unknown.

is a complex polymeric chemical compound that is a major constituent of wood. Resistant to biological decomposition, its presence in paper makes it weaker and more liable to discolor when exposed to light. The species C. bulleri contains three lignin-degrading enzymes: lignin peroxidase

, manganese peroxidase

, and laccase

. These enzyme

s have potential applications not only in the pulp and paper industry

, but also to increase the digestibility and protein content of forage

for cattle. Because laccases can break down phenolic compound

s they may be used to detoxify some environmental pollutants, such as dye

s used in the textile industry

. C. bulleri laccase has also been genetically engineered

to be produced by Escherichia coli

, making it the first fungal laccase to be produced in a bacterial host. C. pallidus can biodegrade the explosive compound RDX

(hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine), suggesting it might be used to decontaminate munitions-contaminated soils.

C. olla

C. olla

is being investigated for its ability to accelerate the decomposition of stubble left in the field after harvest, effectively reducing pathogen populations and accelerating nutrient cycling through mineralization

of essential plant nutrients. C. stercoreus

is known to inhibit the growth of Ralstonia solanacearum

, the causal agent of brown rot

disease of potato, and may have application in reducing this disease and enhancing plant health.

s (plications), while the "olla" group lacked plications. Later (1906), Lloyd

published a different concept of infrageneric grouping in Cyathus, describing five groups, two in the eucyathus group and five in the olla group.

In the 1970s, Brodie, in his monograph on bird's nest fungi, separated the genus Cyathus into seven related groups based on a number of taxonomic

characteristics, including the presence or absence of plications, the structure of the peridioles, the color of the fruiting bodies, and the nature of the hairs on the outer peridium:

Olla group: Species with a tomentum

having fine flattened-down hairs, and no plications.

, C. africanus, C. badius, C. canna, C. colensoi, C. confusus, C. earlei, C. hookeri, C. microsporus, C. minimus, C. pygmaeus

Pallidus group: Species with conspicuous, long, downward-pointing hairs, and a smooth (non-plicate) inner peridium.

Triplex group: Species with mostly dark-colored peridia, and a silvery white inner surface.

Gracilis group: Species with tomentum hairs clumped into tufts or mounds.

Stercoreus group: Species with non-plicate peridia, shaggy or wooly outer peridium walls, and dark to black peridioles.

Poeppigii group: Species with plicate internal peridial walls, hairy to shaggy outer walls, dark to black peridioles, and large, roughly spherical or ellipsoidal spores.

Striatus group: Species with plicate internal peridia, hairy to shaggy outer peridia, and mostly elliptical spores.

, C. annulatus, C. berkeleyanus, C. bulleri, C. chevalieri, C. ellipsoideus, C. helenae

, C. montagnei, C. nigro-albus, C. novae-zeelandiae, C. pullus, C. rudis

s:

ollum group: C. africanus (type

), C. africanus f. latisporus, C. conlensoi, C. griseocarpus, C. guandishanensis, C. hookeri, C. jiayuguanensis, C. olla

, C. olla f. anglicus and C. olla f. brodiensis.

striatum group: C. annulatus, C. crassimurus, C. helenae

, C. poeppigii, C. renwei, C. setosus, C. stercoreus

, and C. triplex.

pallidum group: C. berkeleyanus, C. olla f. lanatus, C. gansuensis, C. pallidus.

This analysis shows that rather than fruiting body structure, spore

size is generally a more reliable character for segregating species groups in Cyathus. For example, species in the ollum clade all have spore lengths less than 15 µm, while all members of the pallidum group have lengths greater than 15 µm; the striatum group, however, cannot be distinguished from the pallidum group by spore size alone. Two characteristics are most suited for distinguishing members of the ollum group from the pallidum group: the thickness of the hair layer on the peridium surface, and the outline of the fruiting bodies. The tomentum of Pallidum species is thick, like felt, and typically aggregates into clumps of shaggy or woolly hair. Their crucible-shaped fruiting bodies do not have a clearly differentiated stipe. The exoperidium of Ollum species, in comparison, has a thin tomentum of fine hairs; fruiting bodies are funnel-shaped and have either a constricted base or a distinct stipe

.

Genus

In biology, a genus is a low-level taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms, which is an example of definition by genus and differentia...

of fungi in the Nidulariaceae

Nidulariaceae

The Nidulariaceae are a family of fungi in the order Nidulariales. Commonly known as the bird's nest fungi, their fruiting bodies resemble tiny egg-filled birds' nests...

, a family

Family (biology)

In biological classification, family is* a taxonomic rank. Other well-known ranks are life, domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, genus, and species, with family fitting between order and genus. As for the other well-known ranks, there is the option of an immediately lower rank, indicated by the...

collectively known as the bird's nest fungi. They are given this name since they resemble tiny bird's nests filled with "eggs", structures large enough to have been mistaken in the past for seeds. However, these are now known to be reproductive structures containing spore

Spore

In biology, a spore is a reproductive structure that is adapted for dispersal and surviving for extended periods of time in unfavorable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many bacteria, plants, algae, fungi and some protozoa. According to scientist Dr...

s. The "eggs", or peridioles, are firmly attached to the inner surface of this fruiting body by an elastic cord of mycelia known as a funiculus. The 45 species are widely distributed throughout the world and some are found in most countries, although a few exist in only one or two locales. Cyathus stercoreus

Cyathus stercoreus

Cyathus stercoreus, commonly known as the dung-loving bird's nest, is a species of fungus in the genus Cyathus, family Nidulariaceae. Like other species in the Nidulariaceae, the fruiting bodies of C. stercoreus resemble tiny bird's nests filled with eggs...

is considered endangered in a number of European countries. Species of Cyathus are also known as splash cups, which refers to the fact that falling raindrops can knock the peridioles out of the open-cup fruiting body. The internal and external surfaces of this cup may be ridged longitudinally (referred to as plicate or striate); this is one example of a taxonomic

Taxonomy

Taxonomy is the science of identifying and naming species, and arranging them into a classification. The field of taxonomy, sometimes referred to as "biological taxonomy", revolves around the description and use of taxonomic units, known as taxa...

characteristic that has traditionally served to distinguish between species.

Generally considered inedible, Cyathus species are saprobic, since they obtain nutrients from decomposing organic matter

Organic matter

Organic matter is matter that has come from a once-living organism; is capable of decay, or the product of decay; or is composed of organic compounds...

. They usually grow on decaying wood or woody debris, on cow and horse dung, or directly on humus-rich soil. The life cycle

Biological life cycle

A life cycle is a period involving all different generations of a species succeeding each other through means of reproduction, whether through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction...

of this genus allows it to reproduce both sexually, with meiosis

Meiosis

Meiosis is a special type of cell division necessary for sexual reproduction. The cells produced by meiosis are gametes or spores. The animals' gametes are called sperm and egg cells....

, and asexually via spores. Several Cyathus species produce bioactive

Natural product

A natural product is a chemical compound or substance produced by a living organism - found in nature that usually has a pharmacological or biological activity for use in pharmaceutical drug discovery and drug design...

compounds, some with medicinal properties, and several lignin

Lignin

Lignin or lignen is a complex chemical compound most commonly derived from wood, and an integral part of the secondary cell walls of plants and some algae. The term was introduced in 1819 by de Candolle and is derived from the Latin word lignum, meaning wood...

-degrading enzyme

Enzyme

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze chemical reactions. In enzymatic reactions, the molecules at the beginning of the process, called substrates, are converted into different molecules, called products. Almost all chemical reactions in a biological cell need enzymes in order to occur at rates...

s from the genus may be useful in bioremediation

Bioremediation

Bioremediation is the use of microorganism metabolism to remove pollutants. Technologies can be generally classified as in situ or ex situ. In situ bioremediation involves treating the contaminated material at the site, while ex situ involves the removal of the contaminated material to be treated...

and agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

. Phylogenetic analysis is providing new insights into the evolution

Evolution

Evolution is any change across successive generations in the heritable characteristics of biological populations. Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity at every level of biological organisation, including species, individual organisms and molecules such as DNA and proteins.Life on Earth...

ary relationships between the various species in Cyathus, and has cast doubt on the validity of the older classification systems that are based on traditional taxonomic characteristics.

History

Bird's nest fungi were first mentioned by Flemish botanist Carolus Clusius in Rariorum plantarum historia (1601). Over the next couple of centuries, these fungi were the subject of some controversy regarding whether the peridioles were seeds, and the mechanism by which they were dispersed in nature. For example, the French botanist Jean-Jacques Paulet, in his work Traité des champignons (1790–3), proposed the erroneous notion that peridioles were ejected from the fruiting bodies by some sort of spring mechanism. The genus was established in 1768 by the Swiss scientist Albrecht von HallerAlbrecht von Haller

Albrecht von Haller was a Swiss anatomist, physiologist, naturalist and poet.-Early life:He was born of an old Swiss family at Bern. Prevented by long-continued ill-health from taking part in boyish sports, he had the more opportunity for the development of his precocious mind...

; the generic name Cyathus is Latin, but originally derived from the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek is the stage of the Greek language in the periods spanning the times c. 9th–6th centuries BC, , c. 5th–4th centuries BC , and the c. 3rd century BC – 6th century AD of ancient Greece and the ancient world; being predated in the 2nd millennium BC by Mycenaean Greek...

word κύαθος, meaning "cup". The structure and biology of the genus Cyathus was better known by the mid-19th century, starting with the appearance of an 1842 paper by J. Schmitz, and two years later, a monograph

Monograph

A monograph is a work of writing upon a single subject, usually by a single author.It is often a scholarly essay or learned treatise, and may be released in the manner of a book or journal article. It is by definition a single document that forms a complete text in itself...

by the brothers Louis René

Louis René Tulasne

Louis René Tulasne, aka Edmond Tulasne was a French botanist and mycologist who was born in Azay-le-Rideau. He originally studied law at Poitiers, but his interest later turned to botany. As a young man he accompanied botanist Auguste de Saint-Hilaire to South America to study the flora of Brazil...

and Charles Tulasne

Charles Tulasne

Charles Tulasne was a French physician and mycologist who was born in Langeais in the département of Indre-et-Loire. He received his medical doctorate in 1840 and practiced medicine in Paris until 1854. Afterwards he worked with his older brother Louis René Tulasne in the field of mycology...

. The work of the Tulasnes was thorough and accurate, and was highly regarded by later researchers. Subsequently, monographs were written in 1902 by Violet S. White (American species), Curtis Gates Lloyd

Curtis Gates Lloyd

Curtis Gates Lloyd was an American mycologist known for both his research on the Gasteromycetes, as well as his controversial views on naming conventions in taxonomy. He had a herbarium with over 59,000 fungal specimens, and published over a thousand new species of fungi...

in 1906, Gordon Herriot Cunningham

G. H. Cunningham

Gordon Herriot Cunningham C.B.E., F.R.S., was the first New Zealand-based mycologist and plant pathologist. In 1936 he was appointed the first director of the DSIR Plant Diseases Division. Cunningham established the New Zealand Fungal Herbarium, and he published extensively on taxonomy of many...

in 1924 (New Zealand species), and Harold J. Brodie

Harold J Brodie

Harold Johnston Brodie was a Canadian mycologist, known for his contributions to the knowledge of the Nidulariaceae, or bird's nest fungi.-Early life:...

in 1975.

Description

Species in the genus Cyathus have fruiting bodies (peridiaPeridium

The peridium is the protective layer that encloses a mass of spores in fungi. This outer covering is a distinctive feature of the Gasteromycetes.-Description:...

) that are vase-, trumpet- or urn-shaped with dimensions of 4–8 mm wide by 7–18 mm tall. Fruiting bodies are brown to gray-brown in color, and covered with small hair-like structures on the outer surface. Some species, like C. striatus and C. setosus, have conspicuous bristles called setae on the rim of the cup. The fruiting body is often expanded at the base into a solid rounded mass of hypha

Hypha

A hypha is a long, branching filamentous structure of a fungus, and also of unrelated Actinobacteria. In most fungi, hyphae are the main mode of vegetative growth, and are collectively called a mycelium; yeasts are unicellular fungi that do not grow as hyphae.-Structure:A hypha consists of one or...

e called an emplacement, which typically becomes tangled and entwined with small fragments of the underlying growing surface, improving its stability and helping it from being knocked over by rain.

Peridium

The peridium is the protective layer that encloses a mass of spores in fungi. This outer covering is a distinctive feature of the Gasteromycetes.-Description:...

opening when young, but eventually dehisces

Dehiscence (botany)

Dehiscence is the opening, at maturity, in a pre-defined way, of a plant structure, such as a fruit, anther, or sporangium, to release its contents. Sometimes this involves the complete detachment of a part. Structures that open in this way are said to be dehiscent...

, breaking open during maturation. Viewed with a microscope, the peridium of Cyathus species is made of three distinct layers—the endo-, meso-, and ectoperidium, referring to the inner, middle, and outer layers respectively. While the surface of the ectoperidium in Cyathus is usually hairy, the endoperidial surface is smooth, and depending on the species, may have longitudinal grooves (striations).

Because the basic fruiting body structure in all genera

Genus

In biology, a genus is a low-level taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms, which is an example of definition by genus and differentia...

of the Nidulariaceae family is essentially similar, Cyathus may be readily confused with species of Nidula

Nidula

Nidula is a genus of fungi in the family Nidulariaceae. Like other members of the Nidulariaceae, their fruit bodies resemble tiny egg-filled birds' nests, from which they derive their common name "bird's nest fungi"...

or Crucibulum

Crucibulum

Crucibulum is a genus in the Nidulariaceae, a family of fungi whose fruiting bodies resemble tiny egg-filled bird's nests. Often called "splash cups", the fruiting bodies are adapted for spore dispersal by using the kinetic energy of falling drops of rain...

, especially older, weathered specimens of Cyathus that may have the hairy ectoperidium worn off. It distinguished from Nidula by the presence of a funiculus, a cord of hyphae attaching the peridiole to the endoperidium. Cyathus differs from genus Crucibulum by having a distinct three-layered wall and a more intricate funiculus.

Peridiole structure

Gleba

Gleba is the fleshy spore-bearing inner mass of fungi such as the puffball or stinkhorn.The gleba is a solid mass of spores, generated within an enclosed area within the sporocarp. The continuous maturity of the sporogenous cells leave the spores behind as a powdery mass that can be easily blown away...

l tissue enclosed by a hard and waxy outer shell. The shape may be described as lenticular—like a biconvex lens—and depending on the species, may range in color from whitish to grayish to black. The interior chamber of the peridiole contains a hymenium

Hymenium

The hymenium is the tissue layer on the hymenophore of a fungal fruiting body where the cells develop into basidia or asci, which produce spores. In some species all of the cells of the hymenium develop into basidia or asci, while in others some cells develop into sterile cells called cystidia or...

that is made of basidia, sterile (non-reproductive) structures, and spores. In young, freshly opened fruiting bodies, the peridioles lie in a clear gelatinous substance which soon dries.

Peridioles are attached to the fruiting body by a funiculus, a complex structure of hypha

Hypha

A hypha is a long, branching filamentous structure of a fungus, and also of unrelated Actinobacteria. In most fungi, hyphae are the main mode of vegetative growth, and are collectively called a mycelium; yeasts are unicellular fungi that do not grow as hyphae.-Structure:A hypha consists of one or...

e that may be differentiated into three regions: the basal piece, which attaches it to the inner wall of the peridium, the middle piece, and an upper sheath, called the purse, connected to the lower surface of the peridiole. In the purse and middle piece is a coiled thread of interwoven hyphae called the funicular cord, attached at one end to the peridiole and at the other end to an entangled mass of hyphae called the hapteron. In some species the peridioles may be covered by a tunica, a thin white membrane (particularly evident in C. striatus

Cyathus striatus

Cyathus striatus, commonly known as the fluted bird's nest, is a common saprobic bird's nest fungus with a widespread distribution throughout temperate regions of the world. This fungus resembles a miniature bird's nest with numerous tiny "eggs"; the eggs, or peridioles, are actually lens-shaped...

and C. crassimurus).

Spore

Spore

In biology, a spore is a reproductive structure that is adapted for dispersal and surviving for extended periods of time in unfavorable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many bacteria, plants, algae, fungi and some protozoa. According to scientist Dr...

s typically have an elliptical or roughly spherical shape, and are thick-walled, hyaline

Hyaline

The term hyaline denotes a substance with a glass-like appearance.-Histopathology:In histopathological medical usage, a hyaline substance appears glassy and pink after being stained with haematoxylin and eosin — usually it is an acellular, proteinaceous material...

or light yellow-brown in color, with dimensions of 5–15 by 5–8 µm

Micrometre

A micrometer , is by definition 1×10-6 of a meter .In plain English, it means one-millionth of a meter . Its unit symbol in the International System of Units is μm...

.

Habitat and distribution

Fruiting bodies typically grow in clusters, and are found on dead or decaying wood, or on woody fragments in cow or horse dung. Dung-loving (coprophilous) species include C. stercoreusCyathus stercoreus

Cyathus stercoreus, commonly known as the dung-loving bird's nest, is a species of fungus in the genus Cyathus, family Nidulariaceae. Like other species in the Nidulariaceae, the fruiting bodies of C. stercoreus resemble tiny bird's nests filled with eggs...

, C. costatus, C. fimicola, and C. pygmaeus. Some species have been collected on woody material like dead herbaceous

Herbaceous

A herbaceous plant is a plant that has leaves and stems that die down at the end of the growing season to the soil level. They have no persistent woody stem above ground...

stems, the empty shells or husk

Husk

Husk in botany is the outer shell or coating of a seed. It often refers to the leafy outer covering of an ear of maize as it grows on the plant. Literally, a husk or hull includes the protective outer covering of a seed, fruit or vegetable...

s of nuts, or on fibrous material like coconut

Coconut

The coconut palm, Cocos nucifera, is a member of the family Arecaceae . It is the only accepted species in the genus Cocos. The term coconut can refer to the entire coconut palm, the seed, or the fruit, which is not a botanical nut. The spelling cocoanut is an old-fashioned form of the word...

, jute

Jute

Jute is a long, soft, shiny vegetable fibre that can be spun into coarse, strong threads. It is produced from plants in the genus Corchorus, which has been classified in the family Tiliaceae, or more recently in Malvaceae....

, or hemp

Hemp

Hemp is mostly used as a name for low tetrahydrocannabinol strains of the plant Cannabis sativa, of fiber and/or oilseed varieties. In modern times, hemp has been used for industrial purposes including paper, textiles, biodegradable plastics, construction, health food and fuel with modest...

fiber woven into matting, sacks or cloth. In nature, fruiting bodies are usually found in moist, partly shaded sites, such as the edges of woods on trails, or around lighted openings in forests. They are less frequently found growing in dense vegetation and deep mosses, as these environments would interfere with the dispersal of peridioles by falling drops of water. The appearance of fruiting bodies is largely dependent upon features of the immediate growing environment; specifically, optimum conditions of temperature, moisture, and nutrient availability are more important factors for fruiting rather than the broad geographical area in which the fungi are located, or the season. Examples of the ability of Cyathus to thrive in somewhat inhospitable environments are provided by C. striatus and C. stercoreus, which can survive the drought and cold of winter in temperate North America, and the species C. helenae

Cyathus helenae

Cyathus helenae is a species of fungus in the genus Cyathus, family Nidulariaceae. Like other members of the Nidulariaceae, C. helenae resembles a tiny bird's nest filled with 'eggs'—spore-containing structures known as peridioles. It was initially described by mycologist Harold Brodie in...

, which has been found growing on dead alpine plants at an altitude of 7000 feet (2,133.6 m).

Range (biology)

In biology, the range or distribution of a species is the geographical area within which that species can be found. Within that range, dispersion is variation in local density.The term is often qualified:...

, but are only rarely found in the arctic

Arctic

The Arctic is a region located at the northern-most part of the Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean and parts of Canada, Russia, Greenland, the United States, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland. The Arctic region consists of a vast, ice-covered ocean, surrounded by treeless permafrost...

and subarctic

Subarctic

The Subarctic is a region in the Northern Hemisphere immediately south of the true Arctic and covering much of Alaska, Canada, the north of Scandinavia, Siberia, and northern Mongolia...

. One of the best known species, C. striatus

Cyathus striatus

Cyathus striatus, commonly known as the fluted bird's nest, is a common saprobic bird's nest fungus with a widespread distribution throughout temperate regions of the world. This fungus resembles a miniature bird's nest with numerous tiny "eggs"; the eggs, or peridioles, are actually lens-shaped...

has a circumpolar

Circumpolar

The term circumpolar may refer to:* circumpolar navigation: to travel the world "vertically" traversing both of the poles* Antarctic region** Antarctic Circle** the Antarctic Circumpolar Current** Subantarctic** List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands...

distribution and is commonly found throughout temperate

Temperate

In geography, temperate or tepid latitudes of the globe lie between the tropics and the polar circles. The changes in these regions between summer and winter are generally relatively moderate, rather than extreme hot or cold...

locations, while the morphologically similar C. poeppigii is widely spread in tropical areas, rarely in the subtropics

Subtropics

The subtropics are the geographical and climatical zone of the Earth immediately north and south of the tropical zone, which is bounded by the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, at latitudes 23.5°N and 23.5°S...

, and never in temperate regions. The majority of species are native to warm climates. For example, although 20 different species have been reported from the United States and Canada, only 8 are commonly encountered; on the other hand, 25 species may be regularly found in the West Indies, and the Hawaiian Islands

Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, numerous smaller islets, and undersea seamounts in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some 1,500 miles from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost Kure Atoll...

alone have 11 species. Some species seem to be endemic to certain regions, such as C. novae-zeelandiae found in New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

, or C. crassimurus, found only in Hawaii; however, this apparent endemism may just be a result of a lack of collections, rather than a difference in the habitat that constitutes a barrier to spread. Although widespread in the tropics and most of the temperate world, C. stercoreus is only rarely found in Europe; this has resulted in its appearance on a number of Red Lists. For example, it is considered endangered in Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

, Denmark

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

, and Montenegro

Montenegro

Montenegro Montenegrin: Crna Gora Црна Гора , meaning "Black Mountain") is a country located in Southeastern Europe. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea to the south-west and is bordered by Croatia to the west, Bosnia and Herzegovina to the northwest, Serbia to the northeast and Albania to the...

, and "near threatened" in Great Britain

Great Britain

Great Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

.

Life cycle

The life cycle of the genus Cyathus, which contains both haploid and diploid stages, is typical of taxa in the basidiomycetes that can reproduce both asexually (via vegetativeVegetative reproduction

Vegetative reproduction is a form of asexual reproduction in plants. It is a process by which new individuals arise without production of seeds or spores...

spores), or sexually (with meiosis

Meiosis

Meiosis is a special type of cell division necessary for sexual reproduction. The cells produced by meiosis are gametes or spores. The animals' gametes are called sperm and egg cells....

). Like other wood-decay fungi, this life cycle may be considered as two functionally different phases: the vegetative stage for the spread of mycelia, and the reproductive stage for the establishment of spore-producing structures, the fruiting bodies.

The vegetative stage encompasses those phases of the life cycle involved with the germination, spread, and survival of the mycelium. Spores germinate under suitable conditions of moisture and temperature, and grow into branching filaments called hypha

Hypha

A hypha is a long, branching filamentous structure of a fungus, and also of unrelated Actinobacteria. In most fungi, hyphae are the main mode of vegetative growth, and are collectively called a mycelium; yeasts are unicellular fungi that do not grow as hyphae.-Structure:A hypha consists of one or...

e, pushing out like roots into the rotting wood. These hyphae are homokaryotic

Homokaryotic

Homokaryotic refers to multinucleate cells where all nuclei are genetically identical. It is the antonym of heterokaryotic....

, containing a single nucleus in each compartment; they increase in length by adding cell-wall material to a growing tip. As these tips expand and spread to produce new growing points, a network called the mycelium develops. Mycelial growth occurs by mitosis

Mitosis

Mitosis is the process by which a eukaryotic cell separates the chromosomes in its cell nucleus into two identical sets, in two separate nuclei. It is generally followed immediately by cytokinesis, which divides the nuclei, cytoplasm, organelles and cell membrane into two cells containing roughly...

and the synthesis of hyphal biomass. When two homokaryotic hyphae of different mating compatibility groups

Mating type

Mating types occur in eukaryotes that undergo sexual reproduction via isogamy. Since the gametes of different mating types look alike, they are often referred to by numbers, letters, or simply "+" and "-" instead of "male" and "female." Mating can only take place between different mating...

fuse with one another, they form a dikaryotic

Dikaryon

Dikaryon is from Greek, di meaning 2 and karyon meaning nut, referring to the cell nucleus.The dikaryon is a nuclear feature which is unique to some fungi, in which after plasmogamy the two compatible nuclei of two cells pair off and cohabit without karyogamy within the cells of the hyphae,...

mycelia in a process called plasmogamy

Plasmogamy

Plasmogamy is a stage in the sexual reproduction of fungi. In this stage, the cytoplasm of two parent mycelia fuse together without the fusion of nuclei, as occurs in higher terrestrial fungi. After plasmogamy occurs, the secondary mycelium forms. The secondary mycelium consists of dikaryotic...

. Prerequisites for mycelial survival and colonization a substrate (like rotting wood) include suitable humidity and nutrient availability. The majority of Cyathus species are saprobic, so mycelial growth in rotting wood is made possible by the secretion of enzyme

Enzyme

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze chemical reactions. In enzymatic reactions, the molecules at the beginning of the process, called substrates, are converted into different molecules, called products. Almost all chemical reactions in a biological cell need enzymes in order to occur at rates...

s that break down complex polysaccharide

Polysaccharide

Polysaccharides are long carbohydrate molecules, of repeated monomer units joined together by glycosidic bonds. They range in structure from linear to highly branched. Polysaccharides are often quite heterogeneous, containing slight modifications of the repeating unit. Depending on the structure,...

s (such as cellulose

Cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to over ten thousand β linked D-glucose units....

and lignin

Lignin

Lignin or lignen is a complex chemical compound most commonly derived from wood, and an integral part of the secondary cell walls of plants and some algae. The term was introduced in 1819 by de Candolle and is derived from the Latin word lignum, meaning wood...

) into simple sugars that can be used as nutrients.

After a period of time and under the appropriate environmental conditions, the dikaryotic mycelia may enter the reproductive stage of the life cycle. Fruiting body formation is influenced by external factors such as season (which affects temperature and air humidity), nutrients and light. As fruiting bodies develop they produce peridioles containing the basidia upon which new basidiospores are made. Young basidia contain a pair of haploid sexually compatible nuclei which fuse, and the resulting diploid fusion nucleus undergoes meiosis to produce basidiospore

Basidiospore

A basidiospore is a reproductive spore produced by Basidiomycete fungi. Basidiospores typically each contain one haploid nucleus that is the product of meiosis, and they are produced by specialized fungal cells called basidia. In grills under a cap of one common species in the phylum of...

s, each containing a single haploid nucleus. The dikaryotic mycelia from which the fruiting bodies are produced is long lasting, and will continue to produce successive generations of fruiting bodies as long as the environmental conditions are favorable.

Heterokaryotic

Heterokaryotic refers to cells where two or more genetically different nuclei share one common cytoplasm. It is the antonym of homokaryotic. This stage after Plasmogamy, the fusion of the cytoplasm,a and before Karyogamy, the fusion of the nuclei. It is neither 1n or 2n. It is in the sexual...

mycelium

Mycelium

thumb|right|Fungal myceliaMycelium is the vegetative part of a fungus, consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae. The mass of hyphae is sometimes called shiro, especially within the fairy ring fungi. Fungal colonies composed of mycelia are found in soil and on or within many other...

to light is required for fruiting to occur, and furthermore, this light needs to be at a wavelength

Wavelength

In physics, the wavelength of a sinusoidal wave is the spatial period of the wave—the distance over which the wave's shape repeats.It is usually determined by considering the distance between consecutive corresponding points of the same phase, such as crests, troughs, or zero crossings, and is a...

of less than 530 nm. Continuous light is not required for fruiting body development; after the mycelium has reached a certain stage of maturity, only a brief exposure to light is necessary, and fruiting bodies will form if even subsequently kept in the dark. Lu suggested in 1965 that certain growing conditions—such as a shortage in available nutrients—shifts the fungus' metabolism

Metabolism

Metabolism is the set of chemical reactions that happen in the cells of living organisms to sustain life. These processes allow organisms to grow and reproduce, maintain their structures, and respond to their environments. Metabolism is usually divided into two categories...

to produce a hypothetical "photoreceptive precursor" that enables the growth of the fruiting bodies to be stimulated and affected by light. The fungi is also positively phototrophic

Phototropism

Phototropism is directional growth in which the direction of growth is determined by the direction of the light source. In other words, it is the growth and response to a light stimulus. Phototropism is most often observed in plants, but can also occur in other organisms such as fungi...

, that is, it will orient its fruiting bodies in the direction of the light source. The time required to develop fruiting bodies depends on a number of factors, such as the temperature, or the availability and type of nutrients, but in general "most species that do fruit in laboratory culture do so best at about 25 °C, in from 18 to 40 days."

Spore dispersal

Like other bird's nest fungi in the NidulariaceaeNidulariaceae

The Nidulariaceae are a family of fungi in the order Nidulariales. Commonly known as the bird's nest fungi, their fruiting bodies resemble tiny egg-filled birds' nests...

, species of Cyathus have their spores dispersed when water falls into the fruiting body. The fruiting body is shaped so that the kinetic energy of a fallen raindrop is redirected upward and slightly outward by the angle of the cup wall, which is consistently 70–75° with the horizontal. The action ejects the peridioles out of the so-called "splash cup", where it may break and spread the spores within, or be eaten and dispersed by animals after passing through the digestive tract. This method of spore dispersal in the Nidulariaceae was tested experimentally by George Willard Martin in 1924, and later elaborated by Arthur Henry Reginald Buller, who used Cyathus striatus

Cyathus striatus

Cyathus striatus, commonly known as the fluted bird's nest, is a common saprobic bird's nest fungus with a widespread distribution throughout temperate regions of the world. This fungus resembles a miniature bird's nest with numerous tiny "eggs"; the eggs, or peridioles, are actually lens-shaped...

as the model species to experimentally investigate the phenomenon. Buller's major conclusions about spore dispersal were later summarized by his graduate student Harold J Brodie, with whom he conducted several of these splash cup experiments:

Raindrops cause the peridioles of the Nidulariaceae to be thrown about four feet by splash action. In the genus Cyathus, as a peridiole is jerked out of its cup, the funiculus is torn and this makes possible the expansion of a mass of adhesive hyphae (the hapteron) which clings to any object in the line of flight. The momentum of the peridiole causes a long cord to be pulled out of a sheath attached to the peridiole. The peridiole is checked in flight and the jerk causes the funicular cord to become wound around stems or entangled among plant hairs. Thus the peridiole becomes attached to vegetation and may be eaten subsequently by herbivorous animals.

Although it has not been shown experimentally if the spores can survive the passage through an animal's digestive tract, the regular presence of Cyathus on cow or horse manure strongly suggest that this is true. Alternatively, the hard outer casing of peridioles ejected from splash cups may simply disintegrate over time, eventually releasing the spores within.

Bioactive compounds

A number of species of Cyathus produce metabolites with biological activity, and novel chemical structures that are specific to this genus. For example, cyathins are diterpenoid compounds produced by C. helenaeCyathus helenae

Cyathus helenae is a species of fungus in the genus Cyathus, family Nidulariaceae. Like other members of the Nidulariaceae, C. helenae resembles a tiny bird's nest filled with 'eggs'—spore-containing structures known as peridioles. It was initially described by mycologist Harold Brodie in...

, C. africanus and C. earlei. Several of the cyathins (especially cyathins B3 and C3), including striatin compounds from C. striatus, show strong antibiotic

Antibiotic

An antibacterial is a compound or substance that kills or slows down the growth of bacteria.The term is often used synonymously with the term antibiotic; today, however, with increased knowledge of the causative agents of various infectious diseases, antibiotic has come to denote a broader range of...

activity. Cyathane diterpenoids also stimulate Nerve Growth Factor

Nerve growth factor

Nerve growth factor is a small secreted protein that is important for the growth, maintenance, and survival of certain target neurons . It also functions as a signaling molecule. It is perhaps the prototypical growth factor, in that it is one of the first to be described...

synthesis, and have the potential to be developed into therapeutic agents for neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease also known in medical literature as Alzheimer disease is the most common form of dementia. There is no cure for the disease, which worsens as it progresses, and eventually leads to death...

. Compounds named cyathuscavins, isolated from the mycelial liquid culture of C. stercoreus, have significant antioxidant

Antioxidant

An antioxidant is a molecule capable of inhibiting the oxidation of other molecules. Oxidation is a chemical reaction that transfers electrons or hydrogen from a substance to an oxidizing agent. Oxidation reactions can produce free radicals. In turn, these radicals can start chain reactions. When...

activity, as do the compounds known as cyathusals, also from C. stercoreus. Various sesquiterpene

Sesquiterpene

Sesquiterpenes are a class of terpenes that consist of three isoprene units and have the molecular formula C15H24. Like monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes may be acyclic or contain rings, including many unique combinations...

compounds have also been identified in C. bulleri, including cybrodol (derived from humulene

Humulene

Humulene, also known as α-humulene or α-caryophyllene, is a naturally occurring monocyclic sesquiterpene, which is a terpenoid consisting of 3 isoprene units. It is found in the essential oils of Humulus lupulus from which it derives its name. It is an isomer of β-caryophyllene, and the two are...

), nidulol, and bullerone.

Various Cyathus species have antifungal activity against human pathogens such as Aspergillus fumigatus

Aspergillus fumigatus

Aspergillus fumigatus is a fungus of the genus Aspergillus, and is one of the most common Aspergillus species to cause disease in individuals with an immunodeficiency....

, Candida albicans

Candida albicans

Candida albicans is a diploid fungus that grows both as yeast and filamentous cells and a causal agent of opportunistic oral and genital infections in humans. Systemic fungal infections including those by C...

and Cryptococcus neoformans

Cryptococcus neoformans

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated yeast that can live in both plants and animals. Its teleomorph is Filobasidiella neoformans, a filamentous fungus belonging to the class Tremellomycetes. It is often found in pigeon excrement....

. Extracts of C. striatus have inhibitory effects on NF-κB, a transcription factor

Transcription factor

In molecular biology and genetics, a transcription factor is a protein that binds to specific DNA sequences, thereby controlling the flow of genetic information from DNA to mRNA...

responsible for regulating the expression

Regulation of gene expression

Gene modulation redirects here. For information on therapeutic regulation of gene expression, see therapeutic gene modulation.Regulation of gene expression includes the processes that cells and viruses use to regulate the way that the information in genes is turned into gene products...

of several genes involved in the immune system

Immune system

An immune system is a system of biological structures and processes within an organism that protects against disease by identifying and killing pathogens and tumor cells. It detects a wide variety of agents, from viruses to parasitic worms, and needs to distinguish them from the organism's own...

, inflammation

Inflammation

Inflammation is part of the complex biological response of vascular tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. Inflammation is a protective attempt by the organism to remove the injurious stimuli and to initiate the healing process...

, and cell death

Programmed cell death

Programmed cell-death is death of a cell in any form, mediated by an intracellular program. PCD is carried out in a regulated process which generally confers advantage during an organism's life-cycle...

.

Edibility

Species in the Nidulariaceae family, including Cyathus, are considered inedible, as they are "not sufficiently large, fleshy, or odorous to be of interest to humans as food". However, there have not been reports of poisonous alkaloidAlkaloid

Alkaloids are a group of naturally occurring chemical compounds that contain mostly basic nitrogen atoms. This group also includes some related compounds with neutral and even weakly acidic properties. Also some synthetic compounds of similar structure are attributed to alkaloids...

s or other substances considered toxic to humans. Brodie goes on to note that two Cyathus species have been used by native peoples as an aphrodisiac

Aphrodisiac

An aphrodisiac is a substance that increases sexual desire. The name comes from Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of sexuality and love. Throughout history, many foods, drinks, and behaviors have had a reputation for making sex more attainable and/or pleasurable...

, or to stimulate fertility

Fertility

Fertility is the natural capability of producing offsprings. As a measure, "fertility rate" is the number of children born per couple, person or population. Fertility differs from fecundity, which is defined as the potential for reproduction...

: C. limbatus in Colombia

Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia , is a unitary constitutional republic comprising thirty-two departments. The country is located in northwestern South America, bordered to the east by Venezuela and Brazil; to the south by Ecuador and Peru; to the north by the Caribbean Sea; to the...

, and C. microsporus in Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an archipelago located in the Leeward Islands, in the Lesser Antilles, with a land area of 1,628 square kilometres and a population of 400,000. It is the first overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department. As with the other overseas departments, Guadeloupe...

. Whether these species have any actual effect on human physiology

Human physiology

Human physiology is the science of the mechanical, physical, bioelectrical, and biochemical functions of humans in good health, their organs, and the cells of which they are composed. Physiology focuses principally at the level of organs and systems...

is unknown.

Biodegradation

LigninLignin

Lignin or lignen is a complex chemical compound most commonly derived from wood, and an integral part of the secondary cell walls of plants and some algae. The term was introduced in 1819 by de Candolle and is derived from the Latin word lignum, meaning wood...

is a complex polymeric chemical compound that is a major constituent of wood. Resistant to biological decomposition, its presence in paper makes it weaker and more liable to discolor when exposed to light. The species C. bulleri contains three lignin-degrading enzymes: lignin peroxidase

Lignin peroxidase

Lignin is highly resistant to biodegradation and only higher fungi are capable of degrading the polymer via an oxidative process. This process has been studied extensively in the past twenty years, but the actual mechanism has not yet been fully elucidated...

, manganese peroxidase

Manganese peroxidase

In enzymology, a manganese peroxidase is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reactionThe 3 substrates of this enzyme are Mn, H+, and H2O2, whereas its two products are Mn and H2O....

, and laccase

Laccase

Laccases are copper-containing oxidase enzymes that are found in many plants, fungi, and microorganisms. The copper is bound in several sites; Type 1, Type 2, and/or Type 3. The ensemble of types 2 and 3 copper is called a trinuclear cluster . Type 1 copper is available to action of solvents,...

. These enzyme

Enzyme

Enzymes are proteins that catalyze chemical reactions. In enzymatic reactions, the molecules at the beginning of the process, called substrates, are converted into different molecules, called products. Almost all chemical reactions in a biological cell need enzymes in order to occur at rates...

s have potential applications not only in the pulp and paper industry

Pulp and paper industry

The global pulp and paper industry is dominated by North American , northern European and East Asian countries...

, but also to increase the digestibility and protein content of forage

Forage

Forage is plant material eaten by grazing livestock.Historically the term forage has meant only plants eaten by the animals directly as pasture, crop residue, or immature cereal crops, but it is also used more loosely to include similar plants cut for fodder and carried to the animals, especially...

for cattle. Because laccases can break down phenolic compound

Phenols

In organic chemistry, phenols, sometimes called phenolics, are a class of chemical compounds consisting of a hydroxyl group bonded directly to an aromatic hydrocarbon group...

s they may be used to detoxify some environmental pollutants, such as dye

Dye

A dye is a colored substance that has an affinity to the substrate to which it is being applied. The dye is generally applied in an aqueous solution, and requires a mordant to improve the fastness of the dye on the fiber....

s used in the textile industry

Textile industry

The textile industry is primarily concerned with the production of yarn, and cloth and the subsequent design or manufacture of clothing and their distribution. The raw material may be natural, or synthetic using products of the chemical industry....

. C. bulleri laccase has also been genetically engineered

Genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification, is the direct human manipulation of an organism's genome using modern DNA technology. It involves the introduction of foreign DNA or synthetic genes into the organism of interest...

to be produced by Escherichia coli

Escherichia coli

Escherichia coli is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that is commonly found in the lower intestine of warm-blooded organisms . Most E. coli strains are harmless, but some serotypes can cause serious food poisoning in humans, and are occasionally responsible for product recalls...

, making it the first fungal laccase to be produced in a bacterial host. C. pallidus can biodegrade the explosive compound RDX

RDX

RDX, an initialism for Research Department Explosive, is an explosive nitroamine widely used in military and industrial applications. It was developed as an explosive which was more powerful than TNT, and it saw wide use in WWII. RDX is also known as cyclonite, hexogen , and T4...

(hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine), suggesting it might be used to decontaminate munitions-contaminated soils.

Agriculture

Cyathus olla

Cyathus olla is a species of saprobic fungus in the genus Cyathus, family Nidulariaceae. The fruit bodies resemble tiny bird's nests filled with "eggs" – spore-containing structures called peridioles. Like other bird's nest fungi, C. olla relies on the force of falling water to dislodge...

is being investigated for its ability to accelerate the decomposition of stubble left in the field after harvest, effectively reducing pathogen populations and accelerating nutrient cycling through mineralization

Mineralization (soil)

Mineralization in soil science, is when the chemical compounds in organic matter decompose or are oxidized into plant-accessible forms,. Mineralization is the opposite of immobilization....

of essential plant nutrients. C. stercoreus

Cyathus stercoreus

Cyathus stercoreus, commonly known as the dung-loving bird's nest, is a species of fungus in the genus Cyathus, family Nidulariaceae. Like other species in the Nidulariaceae, the fruiting bodies of C. stercoreus resemble tiny bird's nests filled with eggs...

is known to inhibit the growth of Ralstonia solanacearum

Ralstonia solanacearum

Ralstonia solanacearum is an aerobic non-sporing, Gram-negative plant pathogenic bacterium. R. solanacearum is soil-borne and motile with a polar flagellar tuft. It colonises the xylem, causing bacterial wilt in a very wide range of potential host plants...

, the causal agent of brown rot

Brown rot

Brown rot may refer to the following diseases:*Wood-decay fungus, a disease of trees and wood.*Ralstonia solanacearum, a disease of plants caused by bacteria.*Monilinia fructicola, a disease of stone fruits....

disease of potato, and may have application in reducing this disease and enhancing plant health.

Infrageneric classification

The genus Cyathus was first subdivided into two infrageneric groups (i.e., grouping species below the rank of genus) by the Tulasne brothers; the "eucyathus" group had fruiting bodies with inner surfaces folded into pleatPleat

A pleat is a type of fold formed by doubling fabric back upon itself and securing it in place. It is commonly used in clothing and upholstery to gather a wide piece of fabric to a narrower circumference....

s (plications), while the "olla" group lacked plications. Later (1906), Lloyd

Curtis Gates Lloyd

Curtis Gates Lloyd was an American mycologist known for both his research on the Gasteromycetes, as well as his controversial views on naming conventions in taxonomy. He had a herbarium with over 59,000 fungal specimens, and published over a thousand new species of fungi...

published a different concept of infrageneric grouping in Cyathus, describing five groups, two in the eucyathus group and five in the olla group.

In the 1970s, Brodie, in his monograph on bird's nest fungi, separated the genus Cyathus into seven related groups based on a number of taxonomic

Taxonomy

Taxonomy is the science of identifying and naming species, and arranging them into a classification. The field of taxonomy, sometimes referred to as "biological taxonomy", revolves around the description and use of taxonomic units, known as taxa...

characteristics, including the presence or absence of plications, the structure of the peridioles, the color of the fruiting bodies, and the nature of the hairs on the outer peridium:

Olla group: Species with a tomentum

Tomentum

Tomentum may refer to the following:*In botany, a covering of closely matted or fine hairs on plant leaves. *A network of minute blood vessels in the brain.* Tomentum in zoology are a short, soft pubescence...

having fine flattened-down hairs, and no plications.

Cyathus olla

Cyathus olla is a species of saprobic fungus in the genus Cyathus, family Nidulariaceae. The fruit bodies resemble tiny bird's nests filled with "eggs" – spore-containing structures called peridioles. Like other bird's nest fungi, C. olla relies on the force of falling water to dislodge...

, C. africanus, C. badius, C. canna, C. colensoi, C. confusus, C. earlei, C. hookeri, C. microsporus, C. minimus, C. pygmaeus

Pallidus group: Species with conspicuous, long, downward-pointing hairs, and a smooth (non-plicate) inner peridium.

- C. pallidus, C. julietae

Triplex group: Species with mostly dark-colored peridia, and a silvery white inner surface.

Gracilis group: Species with tomentum hairs clumped into tufts or mounds.

- C. gracilis, C. intermedius, C. crassimurus, C. elmeri

Stercoreus group: Species with non-plicate peridia, shaggy or wooly outer peridium walls, and dark to black peridioles.

Poeppigii group: Species with plicate internal peridial walls, hairy to shaggy outer walls, dark to black peridioles, and large, roughly spherical or ellipsoidal spores.

- C. poeppigii, C. crispus, C. limbatus, C. gayanus, C. costatus, C. cheliensis, C. olivaceo-brunneus

Striatus group: Species with plicate internal peridia, hairy to shaggy outer peridia, and mostly elliptical spores.

Cyathus striatus

Cyathus striatus, commonly known as the fluted bird's nest, is a common saprobic bird's nest fungus with a widespread distribution throughout temperate regions of the world. This fungus resembles a miniature bird's nest with numerous tiny "eggs"; the eggs, or peridioles, are actually lens-shaped...

, C. annulatus, C. berkeleyanus, C. bulleri, C. chevalieri, C. ellipsoideus, C. helenae

Cyathus helenae

Cyathus helenae is a species of fungus in the genus Cyathus, family Nidulariaceae. Like other members of the Nidulariaceae, C. helenae resembles a tiny bird's nest filled with 'eggs'—spore-containing structures known as peridioles. It was initially described by mycologist Harold Brodie in...

, C. montagnei, C. nigro-albus, C. novae-zeelandiae, C. pullus, C. rudis

Phylogenetic analysis

The 2007 publication of phylogenetic analyses of DNA sequence data of numerous Cyathus species has cast doubt on the validity of the morphology-based infrageneric classifications described by Brodie. This research suggests that Cyathus species can be grouped into three genetically related cladeClade

A clade is a group consisting of a species and all its descendants. In the terms of biological systematics, a clade is a single "branch" on the "tree of life". The idea that such a "natural group" of organisms should be grouped together and given a taxonomic name is central to biological...

s:

ollum group: C. africanus (type

Type species

In biological nomenclature, a type species is both a concept and a practical system which is used in the classification and nomenclature of animals and plants. The value of a "type species" lies in the fact that it makes clear what is meant by a particular genus name. A type species is the species...

), C. africanus f. latisporus, C. conlensoi, C. griseocarpus, C. guandishanensis, C. hookeri, C. jiayuguanensis, C. olla

Cyathus olla

Cyathus olla is a species of saprobic fungus in the genus Cyathus, family Nidulariaceae. The fruit bodies resemble tiny bird's nests filled with "eggs" – spore-containing structures called peridioles. Like other bird's nest fungi, C. olla relies on the force of falling water to dislodge...

, C. olla f. anglicus and C. olla f. brodiensis.

striatum group: C. annulatus, C. crassimurus, C. helenae

Cyathus helenae

Cyathus helenae is a species of fungus in the genus Cyathus, family Nidulariaceae. Like other members of the Nidulariaceae, C. helenae resembles a tiny bird's nest filled with 'eggs'—spore-containing structures known as peridioles. It was initially described by mycologist Harold Brodie in...

, C. poeppigii, C. renwei, C. setosus, C. stercoreus

Cyathus stercoreus

Cyathus stercoreus, commonly known as the dung-loving bird's nest, is a species of fungus in the genus Cyathus, family Nidulariaceae. Like other species in the Nidulariaceae, the fruiting bodies of C. stercoreus resemble tiny bird's nests filled with eggs...

, and C. triplex.

pallidum group: C. berkeleyanus, C. olla f. lanatus, C. gansuensis, C. pallidus.

This analysis shows that rather than fruiting body structure, spore

Spore

In biology, a spore is a reproductive structure that is adapted for dispersal and surviving for extended periods of time in unfavorable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many bacteria, plants, algae, fungi and some protozoa. According to scientist Dr...

size is generally a more reliable character for segregating species groups in Cyathus. For example, species in the ollum clade all have spore lengths less than 15 µm, while all members of the pallidum group have lengths greater than 15 µm; the striatum group, however, cannot be distinguished from the pallidum group by spore size alone. Two characteristics are most suited for distinguishing members of the ollum group from the pallidum group: the thickness of the hair layer on the peridium surface, and the outline of the fruiting bodies. The tomentum of Pallidum species is thick, like felt, and typically aggregates into clumps of shaggy or woolly hair. Their crucible-shaped fruiting bodies do not have a clearly differentiated stipe. The exoperidium of Ollum species, in comparison, has a thin tomentum of fine hairs; fruiting bodies are funnel-shaped and have either a constricted base or a distinct stipe

Stipe (mycology)

thumb|150px|right|Diagram of a [[basidiomycete]] stipe with an [[annulus |annulus]] and [[volva |volva]]In mycology a stipe refers to the stem or stalk-like feature supporting the cap of a mushroom. Like all tissues of the mushroom other than the hymenium, the stipe is composed of sterile hyphal...

.