Glastonbury

Encyclopedia

Glastonbury is a small town in Somerset

, England, situated at a dry point

on the low lying Somerset Levels

, 23 miles (37 km) south of Bristol

. The town, which is in the Mendip

district, had a population of 8,784 in the 2001 census. Glastonbury is less than 1 miles (2 km) across the River Brue

from the village of Street

.

Evidence from timber trackways such as the Sweet Track

show that the town has been inhabited since Neolithic

times. Glastonbury Lake Village

was an Iron Age

village, close to the old course of the River Brue and Sharpham Park

approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Glastonbury, dates back to the Bronze Age

. Centwine

was the first Saxon patron of Glastonbury Abbey

, which dominated the town for the next 700 years. One of the most important abbey

s in England, it was the site of Edmund Ironside

's coronation as King of England in 1016. Many of the oldest surviving buildings in the town, including the Tribunal

, George Hotel and Pilgrims' Inn

and the Somerset Rural Life Museum

, which is based in an old tithe barn

, are associated with the abbey. The Church of St John the Baptist

dates from the 15th century.

The town became a centre for commerce, which led to the construction of the market cross, Glastonbury Canal

and the Glastonbury and Street railway station

, the largest station on the original Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway

. The Brue Valley Living Landscape

is a conservation

project managed by the Somerset Wildlife Trust

and nearby is the Ham Wall

National Nature Reserve

.

Glastonbury has been described as a New Age community

which attracts people with New Age

and Neopagan beliefs, and is notable for myths and legends often related to Glastonbury Tor

, concerning Joseph of Arimathea

, the Holy Grail

and King Arthur

. In some Arthurian literature Glastonbury is identified with the legendary island of Avalon

. Joseph is said to have arrived in Glastonbury and stuck his staff into the ground, when it flowered miraculously into the Glastonbury Thorn

. The presence of a landscape zodiac

around the town has been suggested, along with a collection of ley line

s, but no evidence has been discovered. The Glastonbury Festival

, held in the nearby village of Pilton

, takes its name from the town.

people occupied seasonal camps on the higher ground, indicated by scatters of flints. The Neolithic

people continued to exploit the reedswamps for their natural resources and started to construct wooden trackways. These included the Sweet Track

, west of Glastonbury, which is one of the oldest engineered roads known and was the oldest timber trackway

discovered in Northern Europe, until the 2009 discovery of a 6,000 year-old trackway in Belmarsh Prison

. Tree-ring dating (dendrochronology

) of the timbers has enabled very precise dating of the track, showing it was built in 3807 or 3806 BC. It has been claimed to be the oldest road in the world. The track was discovered in the course of peat digging in 1970, and is named after its discoverer, Ray Sweet. It extended across the marsh

between what was then an island at Westhay

, and a ridge of high ground at Shapwick

, a distance close to 2000 metres (1.2 mi). The track is one of a network of tracks that once crossed the Somerset Levels

. Built in the 39th century BC, during the Neolithic period, the track consisted of crossed poles of ash

, oak

and lime (Tilia

) which were driven into the waterlogged soil to support a walkway that mainly consisted of oak planks laid end-to-end. Since the discovery of the Sweet Track, it has been determined that it was built along the route of an even earlier track, the Post Track, dating from 3838 BC and so 30 years older.

Glastonbury Lake Village

was an Iron Age

village, close to the old course of the River Brue

, on the Somerset Levels near Godney

, some 3 miles (5 km) north west of Glastonbury. It covers an area of 400 feet (122 m) north to south by 300 feet (91 m) east to west, and housed around 100 people in five to seven groups of houses, each for an extended family, with sheds and barns, made of hazel

and willow

covered with reeds, and surrounded either permanently or at certain times by a wooden palisade

. The village was built in about 300 BC and occupied into the early Roman period (around 100AD) when it was abandoned, possibly due to a rise in the water level. It was built on a morass on an artificial foundation of timber filled with brushwood, bracken, rubble and clay.

Sharpham Park

is a 300 acres (1.2 km²) historic park, 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Glastonbury, which dates back to the Bronze Age

.

and could refer either to a fortified place such as a burh

or, more likely, a monastic enclosure, however the Glestinga element is obscure, and may derive from an Old English word or from a Saxon or Celtic personal name.

William of Malmesbury

in his De Antiquitate Glastonie Ecclesie gives the Old Celtic Ineswitrin (or Ynys Witrin) as its earliest name, and asserts that the founder of the town was the eponymous Glast, a descendant of Cunedda

.

Centwine

(676–685) was the first Saxon patron of Glastonbury Abbey

. In 1016 Edmund Ironside

was crowned king at Glastonbury. After his death later that year he was buried at the abbey. To the southwest of the town centre is Beckery, which was once a village in its own right but is now part of the suburbs. Around the 7th and 8th centuries it was occupied by a small monastic community associated with a cemetery.

Sharpham Park was granted by King Eadwig to the then abbot Æthelwold

in 957. In 1191 Sharpham Park was conferred by the soon-to-be King John I

to the Abbots of Glastonbury, who remained in possession of the park and house until the dissolution of the monasteries

in 1539. From 1539 to 1707 the park was owned by the Duke of Somerset

, Sir Edward Seymour

, brother of Queen Jane

; the Thynne

family of Longleat

, and the family of Sir Henry Gould. Edward Dyer

was born here in 1543. The house is now a private residence and Grade II* listed building. It was the birthplace of Sir Edward Dyer

(died 1607) an Elizabethan

poet and courtier, the writer Henry Fielding

(1707–54), and the cleric William Gould.

In the 1070s St Margaret's Chapel was built on Magdelene Street, originally as a hospital and later as almshouses for the poor. The building dates from 1444. The roof of the hall is thought to have been removed after the Dissolution, and some of the building was demolished in the 1960s. It is Grade II* listed, and a Scheduled ancient monument

. In 2010 plans were announced to restore the building.

During the Middle Ages the town largely depended on the abbey but was also a centre for the wool trade until the 18th century. A Saxon-era canal

connected the abbey to the River Brue. Richard Whiting

, the last Abbot of Glastonbury, was executed with two of his monks on 15 November 1539 during the dissolution of the monasteries

.

During the Second Cornish Uprising of 1497

Perkin Warbeck

surrendered when he heard that Giles, Lord Daubeney's troops, loyal to Henry VII

were camped at Glastonbury.

was founded and named after the English town from which some of the settlers had emigrated. It was originally called "Glistening Town" until the mid-19th century when it was changed in line with Glastonbury, England. A representation of the Glastonbury thorn is incorporated onto the town seal.

The Somerset towns charter of incorporation was received in 1705. Growth in the trade and economy largely depended on the drainage of the surrounding moors. The opening of the Glastonbury Canal

produced an upturn in trade, and encouraged local building.

The parish was part of the hundred of Glaston Twelve Hides

.

In the Northover district industrial production of sheepskins, woollen slipper

s and, later, boot

s and shoes, developed in conjunction with the growth of C&J Clark

in Street. Clarks still has its headquarters in Street, but shoes are no longer manufactured there. Instead, in 1993, redundant factory buildings were converted to form Clarks Village

, the first purpose-built factory outlet in the United Kingdom.

During the 19th and 20th centuries tourism developed based on the rise of antiquarian

ism, the association with the abbey and mysticism of the town. This was aided by accessibility via the rail and road network, which has continued to support the town's economy and led to a steady rise in resident population since 1801.

Glastonbury received national media coverage in 1999 when cannabis

plants were found in the town's floral displays.

Glastonbury is notable for myths and legends concerning Joseph of Arimathea

Glastonbury is notable for myths and legends concerning Joseph of Arimathea

, the Holy Grail

and King Arthur

. The legend that Joseph of Arimathea retrieved certain holy relics was introduced by the French poet Robert de Boron

in his 13th-century version of the grail story, thought to have been a trilogy though only fragments of the later books survive today. The work became the inspiration for the later Vulgate Cycle of Arthurian tales.

De Boron's account relates how Joseph captured Jesus' blood in a cup (the "Holy Grail") which was subsequently brought to Britain. The Vulgate Cycle reworked Boron's original tale. Joseph of Arimathea was no longer the chief character in the Grail origin: Joseph's son, Josephus, took over his role of the Grail keeper.

The earliest versions of the grail romance, however, do not call the grail "holy" or mention anything about blood, Joseph or Glastonbury.

In 1191, monks at the abbey claimed to have found the graves of Arthur and Guinevere to the south of the Lady Chapel of the Abbey Church, which was visited by a number of contemporary historians including Giraldus Cambrensis

. The remains were later moved and were lost during the Reformation

. Many scholars suspect that this discovery was a pious forgery to substantiate the antiquity of Glastonbury's foundation, and increase its renown.

In some Arthurian literature Glastonbury is identified with the legendary island of Avalon

. An early Welsh poem links Arthur to the Tor in an account of a confrontation between Arthur and Melwas, who had kidnapped Queen Guinevere

. According to some versions of the Arthurian legend, Lancelot

retreated to Glastonbury Abbey in penance following Arthur's death.

Joseph is said to have arrived in Glastonbury by boat over the flooded Somerset Levels. On disembarking he stuck his staff into the ground and it flowered miraculously into the Glastonbury Thorn

Joseph is said to have arrived in Glastonbury by boat over the flooded Somerset Levels. On disembarking he stuck his staff into the ground and it flowered miraculously into the Glastonbury Thorn

(or Holy Thorn). This is said to explain a hybrid Crataegus monogyna (hawthorn) tree that only grows within a few miles of Glastonbury, and which flowers twice annually, once in spring and again around Christmas time (depending on the weather). Each year a sprig of thorn is cut, by the local Anglican vicar and the eldest child from St John's School, and sent to the Queen.

The original Holy Thorn was a centre of pilgrimage in the Middle Ages but was chopped down during the English Civil War

. A replacement thorn was planted in the 20th century on Wearyall hill (originally in 1951 to mark the Festival of Britain

; but the thorn had to be replanted the following year as the first attempt did not take). Many other examples of the thorn grow throughout Glastonbury including those in the grounds of Glastonbury Abbey, St Johns Church and Chalice Well

.

Today Glastonbury Abbey

presents itself as "traditionally the oldest above-ground Christian church in the world," which according to the legend was built at Joseph's behest to house the Holy Grail

, 65 or so years after the death of Jesus. The legend also says that as a child, Jesus had visited Glastonbury along with Joseph. The legend probably was encouraged during the medieval period when religious relics and pilgrimages were profitable business for abbeys. William Blake

mentioned the legend in a poem that became a popular hymn, "Jerusalem" (see And did those feet in ancient time

).

suggested a landscape zodiac

, a map of the stars on a gigantic scale, formed by features in the landscape such as roads, streams and field boundaries, could be found situated around Glastonbury. She held that the "temple" was created by Sumerians about 2700 BC. The idea of a prehistoric landscape zodiac fell into disrepute when two independent studies examined the Glastonbury Zodiac, one by Ian Burrow in 1975 and the other by Tom Williamson and Liz Bellamy in 1983. These both used standard methods of landscape historical research. Both studies concluded that the evidence contradicted the idea of an ancient zodiac. The eye of Capricorn identified by Maltwood was a haystack. The western wing of the Aquarius phoenix was a road laid in 1782 to run around Glastonbury, and older maps dating back to the 1620s show the road had no predecessors. The Cancer boat (not a crab as in conventional western astrology) consists of a network of 18th-century drainage ditches and paths. There are some Neolithic paths preserved in the peat of the bog formerly comprising most of the area, but none of the known paths match the lines of the zodiac features. There is no support for this theory, or for the existence of the "temple" in any form, from conventional archaeologists. Glastonbury is also said to be the centre of several ley line

s.

ashlar front. It is a Grade II* listed building.

Glastonbury is in the local government district

of Mendip

, which is part of the county of Somerset

. It was previously administered by Glastonbury Municipal Borough. The Mendip district council is responsible for local planning

and building control, local roads, council housing, environmental health

, markets and fairs, refuse collection and recycling

, cemeteries and crematoria, leisure services, parks, and tourism. Somerset County Council

is responsible for running the largest and most expensive local services such as education

, social services, the library, road maintenance, trading standards

, waste disposal and strategic planning.

The town's retained

fire station

is operated by Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue Service

, whilst police and ambulance services are provided by Avon and Somerset Constabulary

and the South Western Ambulance Service

. There are two doctors' surgeries

in Glastonbury, and a National Health Service

community hospital operated by Somerset Primary Care Trust which opened in 2005.

Glastonbury falls within the Wells constituency

, represented in the House of Commons

of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

. It elects one Member of Parliament (MP)

by the first past the post system of election. The Member of Parliament is Tessa Munt

of the Liberal Democrats

. It is within the South West England (European Parliament constituency)

, which elects six MEPs using the d'Hondt method

of party-list proportional representation

.

Glastonbury is twinned with the Greek island of Patmos

, and Lalibela, Ethiopia.

to the distinctive tower at the summit (the partially restored remains of an old church) is rewarded by vistas of the mid-Somerset area, including the Levels which are drained marshland. From there, on a dry point

, 158 metres (518.4 ft) above sea level, it is easy to appreciate how Glastonbury was once an island and, in the winter, the surrounding moors are often flooded, giving that appearance once more. It is an agricultural region typically with open fields of permanent grass, surrounded by ditches with willow

trees. Access to the moors and Levels is by "droves", i.e., green lanes. The Levels and inland moors can be 6 metres (20 ft) below peak tides and have large areas of peat

. The low lying areas are underlain by much older Triassic

age formations of Upper Lias

sand that protrude to form what would once have been islands and include Glastonbury Tor

. The lowland landscape was formed only during the last 10,000 years, following the end of the last ice age

.

The low lying damp ground can produce a visual effect known as a Fata Morgana

. This optical phenomenon

occurs because rays of light are strongly bent when they pass through air layers of different temperatures in a steep thermal inversion where an atmospheric duct

has formed. The Italian name Fata Morgana is derived from the name of Morgan le Fay

, who was alternatively known as Morgane, Morgain, Morgana and other variants. Morgan le Fay was described as a powerful sorceress

and antagonist

of King Arthur

and Queen Guinevere

in the Arthurian legend.

Glastonbury is less than 1 miles (2 km) across the River Brue

from the village of Street

. At the time of King Arthur

the Brue formed a lake just south of the hilly ground on which Glastonbury stands. This lake is one of the locations suggested by Arthurian legend as the home of the Lady of the Lake

. Pomparles Bridge stood at the western end of this lake, guarding Glastonbury from the south, and it is suggested that it was here that Sir Bedivere

threw Excalibur

into the waters after King Arthur fell at the Battle of Camlann

. The old bridge was replaced by a reinforced concrete arch bridge in 1911.

Until the 13th century, the direct route to the sea at Highbridge was prevented by gravel banks and peat near Westhay. The course of the river partially encircled Glastonbury from the south, around the western side (through Beckery), and then north through the Panborough-Bleadney gap in the Wedmore

-Wookey

Hills, to join the River Axe just north of Bleadney. This route made it difficult for the officials of Glastonbury Abbey to transport produce from their outlying estates to the abbey, and when the valley of the River Axe was in flood it backed up to flood Glastonbury itself. Some time between 1230 and 1250 a new channel was constructed westwards into Meare Pool

north of Meare

, and further westwards to Mark Moor. The Brue Valley Living Landscape

is a conservation

project based on the Somerset Levels and Moors and managed by the Somerset Wildlife Trust

. The project commenced in January 2009 and aims to restore, recreate and reconnect habitat

, ensuring that wildlife is enhanced and capable of sustaining itself in the face of climate change

, while guaranteeing farmers and other landowners can continue to use their land profitably. It is one of an increasing number of landscape scale conservation

projects in the UK.

The Ham Wall

National Nature Reserve

, 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) west of Glastonbury, is managed by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

. This new wetland habitat has been established from out peat diggings and now consists of areas of reedbed, wet scrub, open water and peripheral grassland and woodland. Bird species living on the site include the Bearded Tit

and the Bittern

.

The Whitelake River

rises between two low limestone

ridges to the north of Glastonbury, part of the southern edge of the Mendip Hills

. The confluence

of the two small streams that make the Whitelake River is on Worthy Farm, the site of the Glastonbury Festival

, between the small villages of Pilton

and Pylle

.

, Glastonbury has a temperate climate which is generally wetter and milder than the rest of the country. The annual mean temperature is approximately 10 °C (50 °F). Seasonal temperature variation is less extreme than most of the United Kingdom because of the adjacent sea temperatures. The summer months of July and August are the warmest with mean daily maxima of approximately 21 °C (69.8 °F). In winter mean minimum temperatures of 1 °C (33.8 °F) or 2 °C (35.6 °F) are common. In the summer the Azores

high pressure affects the south-west of England, however convective cloud sometimes forms inland, reducing the number of hours of sunshine. Annual sunshine rates are slightly less than the regional average of 1,600 hours. In December 1998 there were 20 days without sun recorded at Yeovilton. Most the rainfall in the south-west is caused by Atlantic depressions or by convection

. Most of the rainfall in autumn and winter is caused by the Atlantic depressions, which is when they are most active. In summer, a large proportion of the rainfall is caused by sun heating the ground leading to convection and to showers and thunderstorms. Average rainfall is around 700 mm (27.6 in). About 8–15 days of snowfall is typical. November to March have the highest mean wind speeds, and June to August have the lightest winds. The predominant wind direction is from the south-west.

. As with many towns of similar size, the centre is not as thriving as it once was but Glastonbury supports a large number of alternative shops.

The outskirts of the town contain a DIY shop a former sheepskin

and slipper factory site, once owned by Morlands

, which is slowly being redevoped. The 31 acres (12.5 ha) site of the old Morlands factory was scheduled for demolition and redevelopment into a new light industrial park, although there have been some protests that the buildings should be reused rather than being demolished. As part of the redevelopment of the site a project has been established by the Glastonbury Community Development Trust to provide support for local unemployed people applying for employment, starting in self-employment and accessing work-related training.

was a medieval merchant's house, used as the Abbey courthouse and, during the Monmouth Rebellion

trials

, by Judge Jeffreys. It now serves as a museum containing possessions and works of art from the Glastonbury Lake Village

which were preserved in almost perfect condition in the peat after the village was abandoned. The museum is run by the Glastonbury Antiquarian Society. The building also houses the tourist information centre.

The octagonal Market Cross was built in 1846 by Benjamin Ferrey

The octagonal Market Cross was built in 1846 by Benjamin Ferrey

.

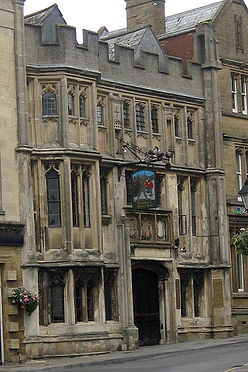

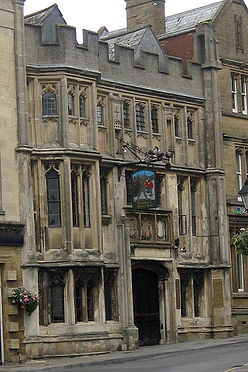

The George Hotel and Pilgrims' Inn

was built in the late 15th century to accommodate visitors to Glastonbury Abbey

, which is open to visitors. It has been designated as a Grade I listed building. The front of the 3-storey building is divided into 3 tiers of panels with traceried heads. Above these are 3 carved panels with arms of the Abbey and Edward IV

.

The Somerset Rural Life Museum

is a museum of the social and agricultural history of Somerset, housed in buildings surrounding a 14th-century barn

once belonging to Glastonbury Abbey. It was used for the storage of arable produce, particularly wheat and rye, from the abbey's home farm of approximately 524 acres (2.1 km²). Threshing and winnowing would also have been carried out in the barn, which was built from local "shelly" limestone

with thick timbers supporting the stone tiling of the roof. It has been designated by English Heritage

as a grade I listed building, and is a Scheduled Ancient Monument

.

The Chalice Well

The Chalice Well

is a holy well

at the foot of the Tor, covered by a wooden well-cover with wrought-iron decoration made in 1919. The natural spring has been in almost constant use for at least two thousand years. Water issues from the spring at a rate of 25000 gallons (113,652.3 l) per day and has never failed, even during drought. Iron oxide

deposits give the water a reddish hue, as dissolved ferrous oxide becomes oxygenated at the surface and is precipitated, providing chalybeate

waters. As with the hot springs in nearby Bath, the water is believed to possess healing qualities. The well is about 9 feet (2.7 m) deep, with two underground chambers at its bottom. It is often portrayed as a symbol of the female aspect of deity

, with the male symbolised by Glastonbury Tor

. As such, it is a popular destination for pilgrim

s in search of the divine feminine, including modern Pagans

. The well is however popular with all faiths and in 2001 became a World Peace Garden.

The Glastonbury Canal

The Glastonbury Canal

ran just over 14 miles (22.5 km) through two locks from Glastonbury to Highbridge

where it entered the Bristol Channel

in the early 19th century, but it became uneconomic with the arrival of the railway in the 1840s.

Glastonbury and Street railway station

was the biggest station on the original Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway

main line from Highbridge to Evercreech Junction

until closed in 1966 under the Beeching axe

. Opened in 1854 as Glastonbury, and renamed in 1886, it had three platforms, two for Evercreech to Highbridge services and one for the branch service to Wells

. The station had a large goods yard controlled from a signal box

. The site is now a timber yard for a local company. Replica level crossing gates have been placed at the entrance.

The main road in the town is the A39

which passes through Glastonbury from Wells

connecting the town with Street

and the M5 motorway

. The other roads around the town are small and run across the levels generally following the drainage ditches. Local bus services are provided by Badgerline, Nippy Bus

, National Express

and local community groups.

. As of 2009, the school had 639 students between the ages of 11 and 16 years. It is named after St. Dunstan, an abbot of Glastonbury Abbey

, who went on to become the Archbishop of Canterbury in 960 AD. The school was built in 1958 with major building work, at a cost of £1.2 million, in 1998, adding the science block and the sports hall. It was designated as a specialist Arts College

in 2004, and the £800,000 spent at this time paid for the Performing Arts studio and facilities to support students with special educational needs.

Strode College

in Street

provides academic and vocational courses for those aged 16–18 and adult education. A tertiary institution and further education

college, most of the courses it offers are A-levels or Business and Technology Education Councils (BTECs). The college also provides some university-level courses, and is part of The University of Plymouth Colleges network

.

, and dates to at least the early 7th century, although later medieval Christian legend claimed that the abbey was founded by Joseph of Arimathea

in the 1st century. This fanciful legend is intimately tied to Robert de Boron

's version of the Holy Grail

story and to Glastonbury's connection to King Arthur

, which dates at least to the early 12th century. Glastonbury fell into Saxon hands after the Battle of Peonnum

in 658. King Ine

of Wessex

enriched the endowment of the community of monk

s already established at Glastonbury. He is said to have directed that a stone church be built in 712. The Abbey Church was enlarged in the 10th century by the Abbot of Glastonbury, Saint Dunstan

, the central figure in the 10th-century revival of English monastic life. He instituted the Benedictine Rule at Glastonbury and built new cloisters. Dunstan became Archbishop of Canterbury

in 960. In 1184, a great fire at Glastonbury destroyed the monastic buildings. Reconstruction began almost immediately and the Lady Chapel

, which includes the well, was consecrated in 1186.

The abbey had a violent end during the Dissolution

The abbey had a violent end during the Dissolution

and the buildings were progressively destroyed as their stones were removed for use in local building work. The remains of the Abbot's Kitchen (a grade I listed building.) and the Lady Chapel

are particularly well-preserved set in 36 acres (145,687 m²) of parkland. It is approached by the Abbey Gatehouse which was built in the mid-14th century and completely restored in 1810.

The Church of St Benedict was rebuilt by Abbot Richard Beere

in about 1520.

The Church of St John the Baptist

dates from the 15th century and has been designated as a Grade I listed building. The church is laid out in a cruciform

plan with an aisled nave

and a clerestorey of seven bays. The west tower has elaborate buttress

ing, panelling and battlements. The interior of the church includes four 15th-century tomb-chests, some 15th-century stained glass

in the chancel, medieval vestments, and a domestic cupboard of about 1500 which was once at Witham Charterhouse

.

The United Reformed Church

on the High Street was built in 1814 and altered in 1898. It stands on the site of the Ship Inn where meetings were held during the 18th century. It is Grade II listed.

The Glastonbury Goddess Temple was founded in 2002 and registered as a place of worship the following year. It is self-described as the first temple of its kind to exist in Europe in over a thousand years.

Division Two as Glastonbury in 1919 and won the Western Football League

title three times in their history. They changed their name to Glastonbury Town in 2003. For the 2010–11 season, they are members of the Somerset County Football League

Premier Division.

Glastonbury Cricket Club

competes in the West of England Premier League

, one of the ECB

Premier Leagues

, the highest level of recreational cricket in England and Wales. The club plays at the Tor Leisure Ground

, which used to stage Somerset County Cricket Club

first-class

fixtures.

where communities have grown up to include people with New Age

beliefs.

In a 1904 novel by Charles Whistler

entitled A Prince of Cornwall Glastonbury in the days of Ine of Wessex

is portrayed. It is also a setting in the Warlord Chronicles a trilogy of books about Arthurian Britain

written by Bernard Cornwell

. Modern fiction has also used Glastonbury as a setting including The Age of Misrule

series of books by Mark Chadbourn

in which the Watchmen appear, a group selected from Anglican priests in and around Glastonbury to safeguard knowledge of a gate to the Otherworld on top of Glastonbury Tor.

The first Glastonbury Festivals were a series of cultural events held in summer, from 1914 to 1926. The festivals were founded by English socialist composer Rutland Boughton

and his librettist Lawrence Buckley. Apart from the founding of a national theatre, they envisaged a summer school and music festival based on utopia

n principles. With strong Arthurian

connections and historic and prehistoric associations, Glastonbury was chosen to host the festivals.

The more recent Glastonbury Festival of Performing Arts

, founded in 1970, is now the largest open-air music and performing arts festival

in the world. Although it is named for Glastonbury, it is held at Worthy Farm between the small villages of Pilton

and Pylle

, 6 miles (9.7 km) east of the town of Glastonbury. The festival is best known for its contemporary music, but also features dance, comedy, theatre, circus, cabaret

and many other arts. For 2005, the enclosed area of the festival was over 900 acres (3.6 km²), had over 385 live performances and was attended by around 150,000 people. In 2007, over 700 acts played on over 80 stages and the capacity expanded by 20,000 to 177,000. The festival has spawned a range of other work including the 1972 film Glastonbury Fayre

and album

, 1996 film Glastonbury the Movie

and the 2005 DVD Glastonbury Anthems

.

The Children's World charity grew out of the festival and is based in the town. It is known internationally (as Children's World International). It was set up by Arabella Churchill

in 1981 to provide drama participation and creative play and to work creatively in educational settings, providing social and emotional benefits for all children, particularly those with special needs. Children's World International is the sister charity of Children's World and was started in 1999 to work with children in the Balkans, in conjunction with Balkan Sunflowers and Save the Children

. They also run the Glastonbury Children's Festival each August.

Glastonbury is one of the venues for the annual West Country Carnival

.

was the recorder of Glastonbury in 1705. Thomas Bramwell Welch

the discoverer of the pasteurisation process to prevent the fermentation

of grape juice

was born in Glastonbury in 1825. The judge John Creighton

represented Lunenburg County in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly

from 1770 to 1775. The fossil

collector Thomas Hawkins

lived in the town during the 19th century.

The religious connections and mythology of the town have also attracted several authors. The occultist and writer Dion Fortune

(Violet Mary Firth) lived and is buried in Glastonbury. Her old house is now home to the writer and historian Geoffrey Ashe

, who is known for his works on local legends. Frederick Bligh Bond

, archaeologist and writer. Eckhart Tolle

, a German-born writer, public speaker, and spiritual teacher lived in Glastonbury during the 1980s. Eileen Caddy

was at a sanctuary in Glastonbury when she first claimed to have heard the "voice of God" while meditating. Her subsequent instructions from the "voice" directed her to take on Sheena Govan

has her spiritual teacher, and became a spiritual teacher and new age

author, best known as one of the founders of the Findhorn Foundation

community. Sally Morningstar

, a Wiccan High Priestess and the author of at least twenty-six books on magic

, astrology

, Ayurveda

, Wicca

, divination

and spirituality teaches Hedge Witchcraft and Natural Magic in Glastonbury, and lives in Somerset.

Popular entertainment and literature is also represented amongst the population. Rutland Boughton

moved from Birmingham to Glastonbury in 1911 and established the country's first national annual summer school of music. Gary Stringer, lead singer of Reef

, was a local along with other members of the band, as are the band Flipron

. The juggler Haggis McLeod

and his late wife, Arabella Churchill

, one of the founders of the Glastonbury Festival

, lived in the town. The author and dramatist Nell Leyshon

and she has set much of her work in the local area. Sarah Fielding

, the 18th-century author and sister of the novelist Henry Fielding

, lived in the town. Michael Aldridge

, a character actor

who appeared as Seymour in the television series Last of the Summer Wine

, was born in Glastonbury. The conductor Charles Hazlewood

lives locally and hosts the "Play the Field" music festival on his farm nearby. Bill Bunbury

moved on from Glastonbury to become a writer, radio broadcaster, and producer for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

.

Athletes and sports players have also been resident. Cricketers born in the town include Cyril Baily

in 1880, George Burrough

in 1907, and Eustace Bisgood

in 1878. The footballer Peter Spiring

was born in Glastonbury in 1950.

Somerset

The ceremonial and non-metropolitan county of Somerset in South West England borders Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south-east, and Devon to the south-west. It is partly bounded to the north and west by the Bristol Channel and the estuary of the...

, England, situated at a dry point

Dry point

In geography a dry point is an area of firm or flood-free ground in an area of wetland, marsh or flood plains. The term typically applies to settlements, and dry point settlements were common in history....

on the low lying Somerset Levels

Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels, or the Somerset Levels and Moors as they are less commonly but more correctly known, is a sparsely populated coastal plain and wetland area of central Somerset, South West England, between the Quantock and Mendip Hills...

, 23 miles (37 km) south of Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

. The town, which is in the Mendip

Mendip

Mendip is a local government district of Somerset in England. The Mendip district covers a largely rural area of ranging from the Mendip Hills through on to the Somerset Levels. It has a population of approximately 110,000...

district, had a population of 8,784 in the 2001 census. Glastonbury is less than 1 miles (2 km) across the River Brue

River Brue

The River Brue originates in the parish of Brewham in Somerset, England, and reaches the sea some 50 km west at Burnham-on-Sea. It originally took a different route from Glastonbury to the sea, but this was changed by the monastery in the twelfth century....

from the village of Street

Street, Somerset

Street is a small village and civil parish in the county of Somerset, England. It is situated on a dry spot in the Somerset Levels, at the end of the Polden Hills, south-west of Glastonbury. The 2001 census records the village as having a population of 11,066...

.

Evidence from timber trackways such as the Sweet Track

Sweet Track

The Sweet Track is an ancient causeway in the Somerset Levels, England. It was built in 3807 or 3806 BC and has been claimed to be the oldest road in the world. It was the oldest timber trackway discovered in Northern Europe until the 2009 discovery of a 6,000 year-old trackway in Belmarsh Prison...

show that the town has been inhabited since Neolithic

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age, Era, or Period, or New Stone Age, was a period in the development of human technology, beginning about 9500 BC in some parts of the Middle East, and later in other parts of the world. It is traditionally considered as the last part of the Stone Age...

times. Glastonbury Lake Village

Glastonbury Lake Village

Glastonbury Lake Village was an iron age village on the Somerset Levels near Godney, some north west of Glastonbury, Somerset, England. It has been designated as a Scheduled Ancient Monument and covers an area of north to south by east to west....

was an Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

village, close to the old course of the River Brue and Sharpham Park

Sharpham

Sharpham is a village and civil parish on the Somerset Levels near Street and Glastonbury in the Mendip district of Somerset, England.It is located near the River Brue.-Governance:...

approximately 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Glastonbury, dates back to the Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

. Centwine

Centwine of Wessex

Centwine was King of Wessex from circa 676 to 685 or 686, although he was perhaps not the only king of the West Saxons at the time.The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that Centwine became king circa 676, succeeding Æscwine...

was the first Saxon patron of Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey was a monastery in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. The ruins are now a grade I listed building, and a Scheduled Ancient Monument and are open as a visitor attraction....

, which dominated the town for the next 700 years. One of the most important abbey

Abbey

An abbey is a Catholic monastery or convent, under the authority of an Abbot or an Abbess, who serves as the spiritual father or mother of the community.The term can also refer to an establishment which has long ceased to function as an abbey,...

s in England, it was the site of Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside or Edmund II was king of England from 23 April to 30 November 1016. His cognomen "Ironside" is not recorded until 1057, but may have been contemporary. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, it was given to him "because of his valour" in resisting the Danish invasion led by Cnut...

's coronation as King of England in 1016. Many of the oldest surviving buildings in the town, including the Tribunal

The Tribunal, Glastonbury

The Tribunal in Glastonbury, Somerset, England was built in the 15th century as a medieval merchant's house. It has been designated as a Grade I listed building....

, George Hotel and Pilgrims' Inn

George Hotel and Pilgrims' Inn, Glastonbury

The George Hotel and Pilgrims' Inn in Glastonbury, Somerset, England was built in the late 15th century to accommodate visitors to Glastonbury Abbey. It has been designated as a Grade I listed building. It is the oldest purpose built public house in the South West of England.The front of the 3...

and the Somerset Rural Life Museum

Somerset Rural Life Museum

The Somerset Rural Life Museum is situated in Glastonbury, Somerset, UK. It is a museum of the social and agricultural history of Somerset, housed in buildings surrounding a 14th century barn once belonging to Glastonbury Abbey....

, which is based in an old tithe barn

Tithe barn

A tithe barn was a type of barn used in much of northern Europe in the Middle Ages for storing the tithes - a tenth of the farm's produce which had to be given to the church....

, are associated with the abbey. The Church of St John the Baptist

Church of St John the Baptist, Glastonbury

The Church of St John the Baptist in Glastonbury, Somerset, England dates from the 15th century and has been designated as a Grade I listed building....

dates from the 15th century.

The town became a centre for commerce, which led to the construction of the market cross, Glastonbury Canal

Glastonbury Canal

The Glastonbury Canal ran for just over through two locks from Glastonbury to Highbridge in Somerset, England, where it entered the River Parrett and from there the Bristol Channel. The canal was authorised by Parliament in 1827 and opened in 1834. It was operated by The Glastonbury Navigation &...

and the Glastonbury and Street railway station

Glastonbury and Street railway station

Glastonbury and Street railway station was the biggest station on the original Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway main line from Highbridge to Evercreech Junction until closed in 1966 under the Beeching axe...

, the largest station on the original Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway

Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway

The Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway – almost always referred to as "the S&D" – was an English railway line connecting Bath in north east Somerset and Bournemouth now in south east Dorset but then in Hampshire...

. The Brue Valley Living Landscape

Brue Valley Living Landscape

The Brue Valley Living Landscape is a UK conservation project based on the Somerset Levels and Moors and managed by the Somerset Wildlife Trust. The project commenced in January 2009 and aims to restore, recreate and reconnect habitat...

is a conservation

Conservation biology

Conservation biology is the scientific study of the nature and status of Earth's biodiversity with the aim of protecting species, their habitats, and ecosystems from excessive rates of extinction...

project managed by the Somerset Wildlife Trust

Somerset Wildlife Trust

Somerset Wildlife Trust is a wildlife trust covering the county of Somerset, England.The trust, which was established in 1964, aims to safeguard the county's wildlife and wild places for this and future generations and manages almost 80 nature reserves. Examples include Fyne Court, Westhay Moor,...

and nearby is the Ham Wall

Ham Wall

The Ham Wall National Nature Reserve, west of Glastonbury, on the Somerset Levels in the valley of the River Brue in Somerset, England is managed by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds....

National Nature Reserve

National Nature Reserve

For details of National nature reserves in the United Kingdom see:*National Nature Reserves in England*National Nature Reserves in Northern Ireland*National Nature Reserves in Scotland*National Nature Reserves in Wales...

.

Glastonbury has been described as a New Age community

New Age communities

New Age communities are places where, intentionally or accidentally, communities have grown up to include significant numbers of people with New Age beliefs. The intentional communities have specific aims but have a variety of structures, purposes and means of subsistence. These include...

which attracts people with New Age

New Age

The New Age movement is a Western spiritual movement that developed in the second half of the 20th century. Its central precepts have been described as "drawing on both Eastern and Western spiritual and metaphysical traditions and then infusing them with influences from self-help and motivational...

and Neopagan beliefs, and is notable for myths and legends often related to Glastonbury Tor

Glastonbury Tor

Glastonbury Tor is a hill at Glastonbury, Somerset, England, which features the roofless St. Michael's Tower. The site is managed by the National Trust. It has been designated as a Scheduled Ancient Monument ....

, concerning Joseph of Arimathea

Joseph of Arimathea

Joseph of Arimathea was, according to the Gospels, the man who donated his own prepared tomb for the burial of Jesus after Jesus' Crucifixion. He is mentioned in all four Gospels.-Gospel references:...

, the Holy Grail

Holy Grail

The Holy Grail is a sacred object figuring in literature and certain Christian traditions, most often identified with the dish, plate, or cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper and said to possess miraculous powers...

and King Arthur

King Arthur

King Arthur is a legendary British leader of the late 5th and early 6th centuries, who, according to Medieval histories and romances, led the defence of Britain against Saxon invaders in the early 6th century. The details of Arthur's story are mainly composed of folklore and literary invention, and...

. In some Arthurian literature Glastonbury is identified with the legendary island of Avalon

Avalon

Avalon is a legendary island featured in the Arthurian legend. It first appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth's 1136 pseudohistorical account Historia Regum Britanniae as the place where King Arthur's sword Excalibur was forged and later where Arthur was...

. Joseph is said to have arrived in Glastonbury and stuck his staff into the ground, when it flowered miraculously into the Glastonbury Thorn

Glastonbury Thorn

The Glastonbury Thorn is a form of Common Hawthorn, Crataegus monogyna 'Biflora' , found in and around Glastonbury, Somerset, England. Unlike ordinary hawthorn trees, it flowers twice a year , the first time in winter and the second time in spring...

. The presence of a landscape zodiac

Landscape zodiac

A landscape zodiac is a map of the stars on a gigantic scale, formed by features in the landscape, such as roads, streams and field boundaries. Perhaps the best known alleged example is the Glastonbury Temple of the Stars, situated around Glastonbury in Somerset, England...

around the town has been suggested, along with a collection of ley line

Ley line

Ley lines are alleged alignments of a number of places of geographical and historical interest, such as ancient monuments and megaliths, natural ridge-tops and water-fords...

s, but no evidence has been discovered. The Glastonbury Festival

Glastonbury Festival

The Glastonbury Festival of Contemporary Performing Arts, commonly abbreviated to Glastonbury or even Glasto, is a performing arts festival that takes place near Pilton, Somerset, England, best known for its contemporary music, but also for dance, comedy, theatre, circus, cabaret and other arts.The...

, held in the nearby village of Pilton

Pilton, Somerset

Pilton is a village and civil parish in Somerset, England, situated on the A361 road in the Mendip district, 3 miles south-west of Shepton Mallet and 6 miles east of Glastonbury. The village has a population of 935...

, takes its name from the town.

Prehistory

During the 7th millennium BC the sea level rose and flooded the valleys and low lying ground surrounding Glastonbury so the MesolithicMesolithic

The Mesolithic is an archaeological concept used to refer to certain groups of archaeological cultures defined as falling between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic....

people occupied seasonal camps on the higher ground, indicated by scatters of flints. The Neolithic

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age, Era, or Period, or New Stone Age, was a period in the development of human technology, beginning about 9500 BC in some parts of the Middle East, and later in other parts of the world. It is traditionally considered as the last part of the Stone Age...

people continued to exploit the reedswamps for their natural resources and started to construct wooden trackways. These included the Sweet Track

Sweet Track

The Sweet Track is an ancient causeway in the Somerset Levels, England. It was built in 3807 or 3806 BC and has been claimed to be the oldest road in the world. It was the oldest timber trackway discovered in Northern Europe until the 2009 discovery of a 6,000 year-old trackway in Belmarsh Prison...

, west of Glastonbury, which is one of the oldest engineered roads known and was the oldest timber trackway

Timber trackway

A timber trackway was typically used as the shortest route between two places in a bog or peatland and have been built for thousands of years as a means of getting between two points. Timber trackways have been identified in archaeological finds in Neolithic England, dating to 500 years before...

discovered in Northern Europe, until the 2009 discovery of a 6,000 year-old trackway in Belmarsh Prison

Belmarsh (HM Prison)

HM Prison Belmarsh is a Category A men's prison, located in the Thamesmead area of the London Borough of Greenwich, in south-east London, England. Belmarsh Prison is operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service...

. Tree-ring dating (dendrochronology

Dendrochronology

Dendrochronology or tree-ring dating is the scientific method of dating based on the analysis of patterns of tree-rings. Dendrochronology can date the time at which tree rings were formed, in many types of wood, to the exact calendar year...

) of the timbers has enabled very precise dating of the track, showing it was built in 3807 or 3806 BC. It has been claimed to be the oldest road in the world. The track was discovered in the course of peat digging in 1970, and is named after its discoverer, Ray Sweet. It extended across the marsh

Marsh

In geography, a marsh, or morass, is a type of wetland that is subject to frequent or continuous flood. Typically the water is shallow and features grasses, rushes, reeds, typhas, sedges, other herbaceous plants, and moss....

between what was then an island at Westhay

Westhay

Westhay is a village in Somerset, England. It is situated in the parish of Meare, north west of Glastonbury on the Somerset Levels, in the Mendip district.The name means 'The west field that is enclosed by hedges' from the Old English west and haga...

, and a ridge of high ground at Shapwick

Shapwick, Somerset

Shapwick is a village on the Somerset Levels, in the Sedgemoor district of Somerset, England. It is situated to the west of Glastonbury.-History:Shapwick is the site of one end of the Sweet Track, an ancient causeway dating from the 39th century BC....

, a distance close to 2000 metres (1.2 mi). The track is one of a network of tracks that once crossed the Somerset Levels

Somerset Levels

The Somerset Levels, or the Somerset Levels and Moors as they are less commonly but more correctly known, is a sparsely populated coastal plain and wetland area of central Somerset, South West England, between the Quantock and Mendip Hills...

. Built in the 39th century BC, during the Neolithic period, the track consisted of crossed poles of ash

Ash tree

Fraxinus is a genus flowering plants in the olive and lilac family, Oleaceae. It contains 45-65 species of usually medium to large trees, mostly deciduous though a few subtropical species are evergreen. The tree's common English name, ash, goes back to the Old English æsc, while the generic name...

, oak

Oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus Quercus , of which about 600 species exist. "Oak" may also appear in the names of species in related genera, notably Lithocarpus...

and lime (Tilia

Tilia

Tilia is a genus of about 30 species of trees native throughout most of the temperate Northern Hemisphere. The greatest species diversity is found in Asia, and the genus also occurs in Europe and eastern North America, but not western North America...

) which were driven into the waterlogged soil to support a walkway that mainly consisted of oak planks laid end-to-end. Since the discovery of the Sweet Track, it has been determined that it was built along the route of an even earlier track, the Post Track, dating from 3838 BC and so 30 years older.

Glastonbury Lake Village

Glastonbury Lake Village

Glastonbury Lake Village was an iron age village on the Somerset Levels near Godney, some north west of Glastonbury, Somerset, England. It has been designated as a Scheduled Ancient Monument and covers an area of north to south by east to west....

was an Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

village, close to the old course of the River Brue

River Brue

The River Brue originates in the parish of Brewham in Somerset, England, and reaches the sea some 50 km west at Burnham-on-Sea. It originally took a different route from Glastonbury to the sea, but this was changed by the monastery in the twelfth century....

, on the Somerset Levels near Godney

Godney

Godney is a village and civil parish near Glastonbury on the River Sheppey on the Somerset Levels in the Mendip district of Somerset, England.-Governance:...

, some 3 miles (5 km) north west of Glastonbury. It covers an area of 400 feet (122 m) north to south by 300 feet (91 m) east to west, and housed around 100 people in five to seven groups of houses, each for an extended family, with sheds and barns, made of hazel

Hazel

The hazels are a genus of deciduous trees and large shrubs native to the temperate northern hemisphere. The genus is usually placed in the birch family Betulaceae, though some botanists split the hazels into a separate family Corylaceae.They have simple, rounded leaves with double-serrate margins...

and willow

Willow

Willows, sallows, and osiers form the genus Salix, around 400 species of deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist soils in cold and temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere...

covered with reeds, and surrounded either permanently or at certain times by a wooden palisade

Palisade

A palisade is a steel or wooden fence or wall of variable height, usually used as a defensive structure.- Typical construction :Typical construction consisted of small or mid sized tree trunks aligned vertically, with no spacing in between. The trunks were sharpened or pointed at the top, and were...

. The village was built in about 300 BC and occupied into the early Roman period (around 100AD) when it was abandoned, possibly due to a rise in the water level. It was built on a morass on an artificial foundation of timber filled with brushwood, bracken, rubble and clay.

Sharpham Park

Sharpham

Sharpham is a village and civil parish on the Somerset Levels near Street and Glastonbury in the Mendip district of Somerset, England.It is located near the River Brue.-Governance:...

is a 300 acres (1.2 km²) historic park, 2 miles (3.2 km) west of Glastonbury, which dates back to the Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

.

Middle Ages

The origin of the name Glastonbury is unclear but when the settlement is first recorded in the 7th and the early 8th century, it was called Glestingaburg. The burg element is Anglo-SaxonAnglo-Saxon

Anglo-Saxon may refer to:* Anglo-Saxons, a group that invaded Britain** Old English, their language** Anglo-Saxon England, their history, one of various ships* White Anglo-Saxon Protestant, an ethnicity* Anglo-Saxon economy, modern macroeconomic term...

and could refer either to a fortified place such as a burh

Burh

A Burh is an Old English name for a fortified town or other defended site, sometimes centred upon a hill fort though always intended as a place of permanent settlement, its origin was in military defence; "it represented only a stage, though a vitally important one, in the evolution of the...

or, more likely, a monastic enclosure, however the Glestinga element is obscure, and may derive from an Old English word or from a Saxon or Celtic personal name.

William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. C. Warren Hollister so ranks him among the most talented generation of writers of history since Bede, "a gifted historical scholar and an omnivorous reader, impressively well versed in the literature of classical,...

in his De Antiquitate Glastonie Ecclesie gives the Old Celtic Ineswitrin (or Ynys Witrin) as its earliest name, and asserts that the founder of the town was the eponymous Glast, a descendant of Cunedda

Cunedda

Cunedda ap Edern , was an important early Welsh leader, and the progenitor of the royal dynasty of Gwynedd.-Background and life:The name Cunedda derives from the Brythonic word , meaning good hound. His genealogy is traced back to Padarn Beisrudd, which literally translates as Paternus of the...

.

Centwine

Centwine of Wessex

Centwine was King of Wessex from circa 676 to 685 or 686, although he was perhaps not the only king of the West Saxons at the time.The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports that Centwine became king circa 676, succeeding Æscwine...

(676–685) was the first Saxon patron of Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey

Glastonbury Abbey was a monastery in Glastonbury, Somerset, England. The ruins are now a grade I listed building, and a Scheduled Ancient Monument and are open as a visitor attraction....

. In 1016 Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside or Edmund II was king of England from 23 April to 30 November 1016. His cognomen "Ironside" is not recorded until 1057, but may have been contemporary. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, it was given to him "because of his valour" in resisting the Danish invasion led by Cnut...

was crowned king at Glastonbury. After his death later that year he was buried at the abbey. To the southwest of the town centre is Beckery, which was once a village in its own right but is now part of the suburbs. Around the 7th and 8th centuries it was occupied by a small monastic community associated with a cemetery.

Sharpham Park was granted by King Eadwig to the then abbot Æthelwold

Æthelwold of Wessex

Æthelwold was the youngest of three known sons of King Æthelred of Wessex. His brother Oswald is recorded between 863 and 875, and Æthelhelm is only recorded as a beneficiary of King Alfred's will in the mid 880s, and probably died soon afterwards...

in 957. In 1191 Sharpham Park was conferred by the soon-to-be King John I

John of England

John , also known as John Lackland , was King of England from 6 April 1199 until his death...

to the Abbots of Glastonbury, who remained in possession of the park and house until the dissolution of the monasteries

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, sometimes referred to as the Suppression of the Monasteries, was the set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 by which Henry VIII disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland; appropriated their...

in 1539. From 1539 to 1707 the park was owned by the Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset is a title in the peerage of England that has been created several times. Derived from Somerset, it is particularly associated with two families; the Beauforts who held the title from the creation of 1448 and the Seymours, from the creation of 1547 and in whose name the title is...

, Sir Edward Seymour

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp of Hache, KG, Earl Marshal was Lord Protector of England in the period between the death of Henry VIII in 1547 and his own indictment in 1549....

, brother of Queen Jane

Jane Seymour

Jane Seymour was Queen of England as the third wife of King Henry VIII. She succeeded Anne Boleyn as queen consort following the latter's execution for trumped up charges of high treason, incest and adultery in May 1536. She died of postnatal complications less than two weeks after the birth of...

; the Thynne

Thomas Thynne, 1st Marquess of Bath

Thomas Thynne, 1st Marquess of Bath KG was a British politician who held office under George III serving as Southern Secretary, Northern Secretary and Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Between 1751 and 1780 he was known as Lord Weymouth...

family of Longleat

Longleat

Longleat is an English stately home, currently the seat of the Marquesses of Bath, adjacent to the village of Horningsham and near the towns of Warminster in Wiltshire and Frome in Somerset. It is noted for its Elizabethan country house, maze, landscaped parkland and safari park. The house is set...

, and the family of Sir Henry Gould. Edward Dyer

Edward Dyer

Sir Edward Dyer was an English courtier and poet.-Life:The son of Sir Thomas Dyer, Kt., he was born at Sharpham Park, Glastonbury, Somerset. He was educated, according to Anthony Wood, either at Balliol College, Oxford or at Broadgates Hall , and left after taking a degree...

was born here in 1543. The house is now a private residence and Grade II* listed building. It was the birthplace of Sir Edward Dyer

Edward Dyer

Sir Edward Dyer was an English courtier and poet.-Life:The son of Sir Thomas Dyer, Kt., he was born at Sharpham Park, Glastonbury, Somerset. He was educated, according to Anthony Wood, either at Balliol College, Oxford or at Broadgates Hall , and left after taking a degree...

(died 1607) an Elizabethan

Elizabethan era

The Elizabethan era was the epoch in English history of Queen Elizabeth I's reign . Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history...

poet and courtier, the writer Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding was an English novelist and dramatist known for his rich earthy humour and satirical prowess, and as the author of the novel Tom Jones....

(1707–54), and the cleric William Gould.

In the 1070s St Margaret's Chapel was built on Magdelene Street, originally as a hospital and later as almshouses for the poor. The building dates from 1444. The roof of the hall is thought to have been removed after the Dissolution, and some of the building was demolished in the 1960s. It is Grade II* listed, and a Scheduled ancient monument

Scheduled Ancient Monument

In the United Kingdom, a scheduled monument is a 'nationally important' archaeological site or historic building, given protection against unauthorized change. The various pieces of legislation used for legally protecting heritage assets from damage and destruction are grouped under the term...

. In 2010 plans were announced to restore the building.

During the Middle Ages the town largely depended on the abbey but was also a centre for the wool trade until the 18th century. A Saxon-era canal

Glastonbury Canal (medieval)

The medieval Glastonbury canal was built in about the middle of the 10th century to link the River Brue at Northover with Glastonbury Abbey, a distance of about . Its initial purpose is believed to be the transport of building stone for the abbey, but later it was used for delivering produce,...

connected the abbey to the River Brue. Richard Whiting

Richard Whiting (the Blessed Richard Whiting)

Blessed Richard Whiting was an English clergyman and the last Abbot of Glastonbury. He presided over Glastonbury Abbey at the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries under King Henry VIII of England, and was executed for unclear reasons in 1539...

, the last Abbot of Glastonbury, was executed with two of his monks on 15 November 1539 during the dissolution of the monasteries

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, sometimes referred to as the Suppression of the Monasteries, was the set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 by which Henry VIII disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland; appropriated their...

.

During the Second Cornish Uprising of 1497

Second Cornish Uprising of 1497

The Second Cornish Uprising is the name given to the Cornish uprising of September 1497 when the pretender to the throne Perkin Warbeck landed at Whitesand Bay, near Land's End, on 7 September with just 120 men in two ships...

Perkin Warbeck

Perkin Warbeck

Perkin Warbeck was a pretender to the English throne during the reign of King Henry VII of England. By claiming to be Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, the younger son of King Edward IV, one of the Princes in the Tower, Warbeck was a significant threat to the newly established Tudor Dynasty,...

surrendered when he heard that Giles, Lord Daubeney's troops, loyal to Henry VII

Henry VII of England

Henry VII was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizing the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death on 21 April 1509, as the first monarch of the House of Tudor....

were camped at Glastonbury.

Early modern

In 1693 Glastonbury, ConnecticutGlastonbury, Connecticut

Glastonbury is a town in Hartford County, Connecticut, United States, founded in 1693. The population was 31,876 at the 2000 census. The town was named after Glastonbury in Somerset, England. Glastonbury is located on the banks of the Connecticut River, 7 miles southeast of Hartford. The town...

was founded and named after the English town from which some of the settlers had emigrated. It was originally called "Glistening Town" until the mid-19th century when it was changed in line with Glastonbury, England. A representation of the Glastonbury thorn is incorporated onto the town seal.

The Somerset towns charter of incorporation was received in 1705. Growth in the trade and economy largely depended on the drainage of the surrounding moors. The opening of the Glastonbury Canal

Glastonbury Canal

The Glastonbury Canal ran for just over through two locks from Glastonbury to Highbridge in Somerset, England, where it entered the River Parrett and from there the Bristol Channel. The canal was authorised by Parliament in 1827 and opened in 1834. It was operated by The Glastonbury Navigation &...

produced an upturn in trade, and encouraged local building.

The parish was part of the hundred of Glaston Twelve Hides

Glaston Twelve Hides (hundred)

The Hundred of Glaston Twelve Hides is one of the 40 historical Hundreds in the ceremonial county of Somerset, England, dating from before the Norman conquest during the Anglo-Saxon era although exact dates are unknown. Each hundred had a 'fyrd', which acted as the local defence force and a court...

.

Modern history

By the middle of the 18th century the Glastonbury Canal drainage problems and competition from the new railways caused a decline in trade, and the town's economy became depressed. The canal was closed on 1 July 1854, and the lock and aqueducts on the upper section were dismantled. The railway opened on 17 August 1854. The lower sections of the canal were given to the Commissioners for Sewers, for use as a drainage ditch. The final section was retained to provide a wharf for the railway company, which was used until 1936, when it passed to the Commissioners of Sewers and was filled in. The Central Somerset Railway merged with the Dorset Central Railway to become the Somerset and Dorset Railway. The main line to Glastonbury closed in 1966.In the Northover district industrial production of sheepskins, woollen slipper

Slipper

A slipper or houseshoe is a semi-closed type of indoor/outdoor shoe, consisting of a sole held to the wearer's foot by a strap running over the toes or instep. Slippers are soft and lightweight compared to other types of footwear. They are mostly made of soft or comforting materials that allow a...

s and, later, boot

Boot

A boot is a type of footwear but they are not shoes. Most boots mainly cover the foot and the ankle and extend up the leg, sometimes as far as the knee or even the hip. Most boots have a heel that is clearly distinguishable from the rest of the sole, even if the two are made of one piece....

s and shoes, developed in conjunction with the growth of C&J Clark

C&J Clark

C. and J. Clark International Ltd, trading as Clarks, is a British, international shoe manufacturer and retailer based in Street, Somerset, England...

in Street. Clarks still has its headquarters in Street, but shoes are no longer manufactured there. Instead, in 1993, redundant factory buildings were converted to form Clarks Village

Clarks Village

Clarks Village is a designer outlet shopping complex at Street in the English county of Somerset. The centre includes more than 90 shops. There are also coffee shops, refreshment stalls and a dining area shared by fast food chains , mostly selling goods at a discount to high street prices.It is...

, the first purpose-built factory outlet in the United Kingdom.

During the 19th and 20th centuries tourism developed based on the rise of antiquarian

Antiquarian

An antiquarian or antiquary is an aficionado or student of antiquities or things of the past. More specifically, the term is used for those who study history with particular attention to ancient objects of art or science, archaeological and historic sites, or historic archives and manuscripts...

ism, the association with the abbey and mysticism of the town. This was aided by accessibility via the rail and road network, which has continued to support the town's economy and led to a steady rise in resident population since 1801.

Glastonbury received national media coverage in 1999 when cannabis

Cannabis

Cannabis is a genus of flowering plants that includes three putative species, Cannabis sativa, Cannabis indica, and Cannabis ruderalis. These three taxa are indigenous to Central Asia, and South Asia. Cannabis has long been used for fibre , for seed and seed oils, for medicinal purposes, and as a...

plants were found in the town's floral displays.

Mythology and legends

Joseph of Arimathea

Joseph of Arimathea was, according to the Gospels, the man who donated his own prepared tomb for the burial of Jesus after Jesus' Crucifixion. He is mentioned in all four Gospels.-Gospel references:...

, the Holy Grail

Holy Grail

The Holy Grail is a sacred object figuring in literature and certain Christian traditions, most often identified with the dish, plate, or cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper and said to possess miraculous powers...

and King Arthur

King Arthur

King Arthur is a legendary British leader of the late 5th and early 6th centuries, who, according to Medieval histories and romances, led the defence of Britain against Saxon invaders in the early 6th century. The details of Arthur's story are mainly composed of folklore and literary invention, and...

. The legend that Joseph of Arimathea retrieved certain holy relics was introduced by the French poet Robert de Boron

Robert de Boron

Robert de Boron was a French poet of the late 12th and early 13th centuries who is most notable as the author of the poems Joseph d'Arimathe and Merlin.-Work:...

in his 13th-century version of the grail story, thought to have been a trilogy though only fragments of the later books survive today. The work became the inspiration for the later Vulgate Cycle of Arthurian tales.

De Boron's account relates how Joseph captured Jesus' blood in a cup (the "Holy Grail") which was subsequently brought to Britain. The Vulgate Cycle reworked Boron's original tale. Joseph of Arimathea was no longer the chief character in the Grail origin: Joseph's son, Josephus, took over his role of the Grail keeper.

The earliest versions of the grail romance, however, do not call the grail "holy" or mention anything about blood, Joseph or Glastonbury.

In 1191, monks at the abbey claimed to have found the graves of Arthur and Guinevere to the south of the Lady Chapel of the Abbey Church, which was visited by a number of contemporary historians including Giraldus Cambrensis

Giraldus Cambrensis

Gerald of Wales , also known as Gerallt Gymro in Welsh or Giraldus Cambrensis in Latin, archdeacon of Brecon, was a medieval clergyman and chronicler of his times...

. The remains were later moved and were lost during the Reformation

English Reformation

The English Reformation was the series of events in 16th-century England by which the Church of England broke away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church....

. Many scholars suspect that this discovery was a pious forgery to substantiate the antiquity of Glastonbury's foundation, and increase its renown.

In some Arthurian literature Glastonbury is identified with the legendary island of Avalon

Avalon

Avalon is a legendary island featured in the Arthurian legend. It first appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth's 1136 pseudohistorical account Historia Regum Britanniae as the place where King Arthur's sword Excalibur was forged and later where Arthur was...

. An early Welsh poem links Arthur to the Tor in an account of a confrontation between Arthur and Melwas, who had kidnapped Queen Guinevere

Guinevere

Guinevere was the legendary queen consort of King Arthur. In tales and folklore, she was said to have had a love affair with Arthur's chief knight Sir Lancelot...

. According to some versions of the Arthurian legend, Lancelot

Lancelot

Sir Lancelot du Lac is one of the Knights of the Round Table in the Arthurian legend. He is the most trusted of King Arthur's knights and plays a part in many of Arthur's victories...

retreated to Glastonbury Abbey in penance following Arthur's death.

Glastonbury Thorn

The Glastonbury Thorn is a form of Common Hawthorn, Crataegus monogyna 'Biflora' , found in and around Glastonbury, Somerset, England. Unlike ordinary hawthorn trees, it flowers twice a year , the first time in winter and the second time in spring...

(or Holy Thorn). This is said to explain a hybrid Crataegus monogyna (hawthorn) tree that only grows within a few miles of Glastonbury, and which flowers twice annually, once in spring and again around Christmas time (depending on the weather). Each year a sprig of thorn is cut, by the local Anglican vicar and the eldest child from St John's School, and sent to the Queen.

The original Holy Thorn was a centre of pilgrimage in the Middle Ages but was chopped down during the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

. A replacement thorn was planted in the 20th century on Wearyall hill (originally in 1951 to mark the Festival of Britain

Festival of Britain

The Festival of Britain was a national exhibition in Britain in the summer of 1951. It was organised by the government to give Britons a feeling of recovery in the aftermath of war and to promote good quality design in the rebuilding of British towns and cities. The Festival's centrepiece was in...

; but the thorn had to be replanted the following year as the first attempt did not take). Many other examples of the thorn grow throughout Glastonbury including those in the grounds of Glastonbury Abbey, St Johns Church and Chalice Well

Chalice Well