.gif)

History of Australia (1901-1945)

Encyclopedia

The history of Australia from 1901–1945 begins with the federation

Federation of Australia

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Victoria and Western Australia formed one nation...

of the colonies to create the Commonwealth of Australia. The young nation joined Britain in the First World War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, suffered in the global Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

and again joined Britain in the Second World War

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

in 1939. Imperial Japan launched air raids and submarine raids against Australian cities during the Pacific War

Pacific War

The Pacific War, also sometimes called the Asia-Pacific War refers broadly to the parts of World War II that took place in the Pacific Ocean, its islands, and in East Asia, then called the Far East...

.

Federation

At the beginning of the 20th century, nearly two decades of negotiations on federation concluded with the approval of a federal constitution by all six Australian colonies and its subsequent ratification by the British parliament

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

in 1900. This resulted in the creation of one federal Australian state on 1 January 1901. Federation was a symbol of unity and gave people the chance to be 'Australian'.

Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

was chosen as the temporary seat of government while a purpose-designed capital city, Canberra

Canberra

Canberra is the capital city of Australia. With a population of over 345,000, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory , south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Melbourne...

, was constructed. The future King George V

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

, then the Duke of York, opened the first Parliament of Australia

Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia, also known as the Commonwealth Parliament or Federal Parliament, is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It is bicameral, largely modelled in the Westminster tradition, but with some influences from the United States Congress...

on 9 May 1901, and his successor, (later to be King George VI

George VI of the United Kingdom

George VI was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death...

) opened the first session in Canberra during May 1927. Australia became officially autonomous in both internal and external affairs with the passage of the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act on 9 October 1942. The Australia Act in (1986) eliminated the last vestiges of British legal authority at the Federal level. (The last state to remove recourse to British courts, Queensland did not do so until 1988).

Early 20th century

Constitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia is the supreme law under which the Australian Commonwealth Government operates. It consists of several documents. The most important is the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia...

was proclaimed by the Governor General

Governor-General of Australia

The Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia is the representative in Australia at federal/national level of the Australian monarch . He or she exercises the supreme executive power of the Commonwealth...

, Lord Hopetoun

John Hope, 1st Marquess of Linlithgow

John Adrian Louis Hope, 1st Marquess of Linlithgow KT, GCMG, GCVO, PC , also known as Viscount Aithrie before 1873 and as The 7th Earl of Hopetoun between 1873 and 1902, was a Scottish aristocrat, politician and colonial administrator. He is best known for his brief and controversial tenure as the...

, on 1 January 1901. The first Federal elections

Elections in Australia

Australia elects a legislature the Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia using various electoral systems: see Australian electoral system. The Parliament consists of two chambers:...

were held in March 1901 and resulted in a narrow majority for the Protectionist Party

Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1889 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. It argued that Australia needed protective tariffs to allow Australian industry to grow and provide employment. It had its greatest strength in Victoria and in...

over the Free Trade Party

Free Trade Party

The Free Trade Party which was officially known as the Australian Free Trade and Liberal Association, also referred to as the Revenue Tariff Party in some states and renamed the Anti-Socialist Party in 1906, was an Australian political party, formally organised between 1889 and 1909...

with the Australian Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

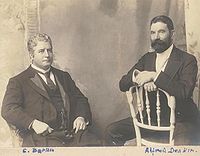

(ALP) polling third. Labor declared it would offer support to the party which offered concessions and Edmund Barton

Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund Barton, GCMG, KC , Australian politician and judge, was the first Prime Minister of Australia and a founding justice of the High Court of Australia....

's Protectionists formed a government, with Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin , Australian politician, was a leader of the movement for Australian federation and later the second Prime Minister of Australia. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Deakin was a major contributor to the establishment of liberal reforms in the colony of Victoria, including the...

as Attorney General.

Barton promised to "create a high court,... and an efficient federal public service.... He proposed to extend conciliation and arbitration, create a uniform railway gauge between the eastern capitals, to introduce female federal franchise, to establish a... system of old age pensions." He also promised to introduce legislation to safeguard "White Australia

White Australia policy

The White Australia policy comprises various historical policies that intentionally restricted "non-white" immigration to Australia. From origins at Federation in 1901, the polices were progressively dismantled between 1949-1973....

" from any influx of Asian or Pacific Island labour.

The Labor Party (the spelling "Labour" was dropped in 1912) had been established in the 1890s, after the failure of the Maritime

1890 Australian maritime dispute

The 1890 Australian Maritime Dispute, commonly known as the 1890 Maritime Strike, was on a scale unprecedented in the Australian colonies to that point in time, causing political and social turmoil across all Australian colonies and in New Zealand, including the collapse of colonial governments in...

and Shearer’s

1891 Australian shearers' strike

350px|thumb|Shearers' strike camp, Hughenden, central Queensland, 1891.The 1891 shearers' strike is one of Australia's earliest and most important industrial disputes. Working conditions for sheep shearers in 19th century Australia weren't good. In 1891 wool was one of Australia's largest industries...

strikes. Its strength was in the Australian Trade Union movement

Australian labour movement

The Australian labour movement has its origins in the early 19th century and includes both trade unions and political activity. At its broadest, the movement can be defined as encompassing the industrial wing, the unions in Australia, and the political wing, the Australian Labor Party and minor...

"which grew from a membership of just under 100,000 in 1901 to more than half a million in 1914." The platform of the ALP was democratic socialist. Its rising support at elections, together with its formation of federal government in 1904 under Chris Watson

Chris Watson

John Christian Watson , commonly known as Chris Watson, Australian politician, was the third Prime Minister of Australia...

, and again in 1908, helped to unify competing conservative, free market

Free market

A free market is a competitive market where prices are determined by supply and demand. However, the term is also commonly used for markets in which economic intervention and regulation by the state is limited to tax collection, and enforcement of private ownership and contracts...

and liberal

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

anti-socialists into the Commonwealth Liberal Party

Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Commonwealth Liberal Party was a political movement active in Australia from 1909 to 1916, shortly after federation....

in 1909. Although this party dissolved in 1916, a successor to its version of "liberalism" in Australia which in some respects comprises an alliance of Millsian

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill was a British philosopher, economist and civil servant. An influential contributor to social theory, political theory, and political economy, his conception of liberty justified the freedom of the individual in opposition to unlimited state control. He was a proponent of...

liberals and Burkian

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke PC was an Irish statesman, author, orator, political theorist and philosopher who, after moving to England, served for many years in the House of Commons of Great Britain as a member of the Whig party....

conservatives united in support for individualism

Individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, or social outlook that stresses "the moral worth of the individual". Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and so value independence and self-reliance while opposing most external interference upon one's own...

and opposition to socialism

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

can be found in the modern Liberal Party

Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is an Australian political party.Founded a year after the 1943 federal election to replace the United Australia Party, the centre-right Liberal Party typically competes with the centre-left Australian Labor Party for political office...

. To represent rural interests, the Country Party

National Party of Australia

The National Party of Australia is an Australian political party.Traditionally representing graziers, farmers and rural voters generally, it began as the The Country Party, but adopted the name The National Country Party in 1975, changed to The National Party of Australia in 1982. The party is...

(today's National Party) was founded in 1913 in Western Australia, and nationally in 1920, from a number of state-based farmer's parties.

Immigration Restriction Act 1901

The Immigration Restriction Act 1901 was an Act of the Parliament of Australia which limited immigration to Australia and formed the basis of the White Australia policy. It also provided for illegal immigrants to be deported. It granted immigration officers a wide degree of discretion to prevent...

was one of the first laws passed by the new Australian parliament

Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia, also known as the Commonwealth Parliament or Federal Parliament, is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It is bicameral, largely modelled in the Westminster tradition, but with some influences from the United States Congress...

. Aimed to restrict immigration from Asia (especially China), it found strong support in the national parliament, arguments ranging from economic protection to outright racism. The law permitted a dictation test in any European language to be used to in effect exclude non-"white" immigrants. The ALP wanted to protect "white" jobs and pushed for more explicit restrictions. A few politicians spoke of the need to avoid hysterical treatment of the question. Member of Parliament Bruce Smith said he had "no desire to see low-class Indians, Chinamen or Japanese... swarming into this country.... But there is obligation...not (to) unnecessarily offend the educated classes of those nations" Donald Cameron, a member from Tasmania, expressed a rare note of dissension:

Outside parliament, Australia's first Catholic cardinal

Cardinal (Catholicism)

A cardinal is a senior ecclesiastical official, usually an ordained bishop, and ecclesiastical prince of the Catholic Church. They are collectively known as the College of Cardinals, which as a body elects a new pope. The duties of the cardinals include attending the meetings of the College and...

, Patrick Francis Moran was politically active and denounced anti-Chinese legislation as "unchristian". The popular press mocked the cardinal's position and the small European population of Australia generally supported the legislation and remained fearful of being overwhelmed by an influx of non-British migrants from the vastly different cultures of the highly populated empires to Australia's north.

The law passed both houses of Parliament and remained a central feature of Australia's immigration laws until abandoned in the 1950s. In the 1930s, the Lyons government

Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons, CH was an Australian politician. He was Labor Premier of Tasmania from 1923 to 1928 and a Minister in the James Scullin government from 1929 until his resignation from the Labor Party in March 1931...

unsuccessfully attempted to exclude Egon Erwin Kisch

Egon Erwin Kisch

Egon Erwin Kisch was a Czechoslovak writer and journalist, who wrote in German. Known as the The raging reporter from Prague, Kisch was noted for his development of literary reportage and his opposition to Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime.- Biography :Kisch was born into a wealthy, German-speaking...

, a Czechoslovakian communist author from entering Australia by means of a 'dictation test' in Scottish Gaelic. The High Court of Australia

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

ruled against this usage, and concerns emerged that the law could be used for such political purposes.

Before 1901, units of soldiers from all six Australian colonies had been active as part of British forces in the Boer War

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

. When the British government asked for more troops from Australia in early 1902, the Australian government obliged with a national contingent. Some 16,500 men had volunteered for service by the war's end in June 1902. But Australians soon felt vulnerable closer to home. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance

Anglo-Japanese Alliance

The first was signed in London at what is now the Lansdowne Club, on January 30, 1902, by Lord Lansdowne and Hayashi Tadasu . A diplomatic milestone for its ending of Britain's splendid isolation, the alliance was renewed and extended in scope twice, in 1905 and 1911, before its demise in 1921...

of 1902 "allowed the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

to withdraw its capital ships from the Pacific by 1907. Australians saw themselves in time of war a lonely, sparsely populated outpost." The impressive visit of the US Navy's Great White Fleet

Great White Fleet

The Great White Fleet was the popular nickname for the United States Navy battle fleet that completed a circumnavigation of the globe from 16 December 1907 to 22 February 1909 by order of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt. It consisted of 16 battleships divided into two squadrons, along with...

in 1908 emphasised to the government the value of an Australian navy

History of the Royal Australian Navy

The history of the Royal Australian Navy can be traced back to 1788 and the colonisation of Australia by the British. During the period until 1859, vessels of the Royal Navy made frequent trips to the new colonies. In 1859, the Australia Squadron was formed as a separate squadron and remained in...

. The Defence Act of 1909 reinforced the importance of Australian defence, and in February 1910, Lord Kitchener

Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener

Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener KG, KP, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCMG, GCIE, ADC, PC , was an Irish-born British Field Marshal and proconsul who won fame for his imperial campaigns and later played a central role in the early part of the First World War, although he died halfway...

provided further advice on a defence scheme based on conscription

Conscription in Australia

Conscription in Australia, or mandatory military service also known as National Service, has a controversial history dating back to the first years of nationhood...

. By 1913, the Battle Cruiser Australia

HMAS Australia (1911)

HMAS Australia was one of three s built for the defence of the British Empire. Ordered by the Australian government in 1909, she was launched in 1911, and commissioned as flagship of the fledgling Royal Australian Navy in 1913...

led the fledgling Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy is the naval branch of the Australian Defence Force. Following the Federation of Australia in 1901, the ships and resources of the separate colonial navies were integrated into a national force: the Commonwealth Naval Forces...

. Historian Bill Gammage

Bill Gammage

William Leonard "Bill" Gammage AM is an Australian academic historian, Adjunct Professor and Senior Research Fellow at the Humanities Research Centre of Australian National University....

estimates on the eve of war, Australia had 200,000 men "under arms of some sort".

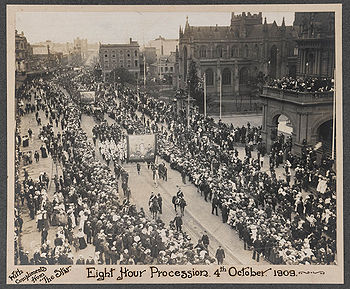

Historians Humphrey McQueen

Humphrey McQueen

Humphrey McQueen is an Australian author, historian, and cultural commentator. He has written many books on a wide range of subjects covering history, the media, politics and the visual arts...

has it that working and living conditions for Australia’s working classes in the early 20th century were of "frugal comfort." While the establishment of an Arbitration court for Labour disputes

Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904

The Conciliation and Arbitration Act 1904 was an Australian Commonwealth Government Act "relating to Conciliation and Arbitration for the Prevention and Settlement of Industrial Disputes extending beyond the Limits of any one State", and was assented to on 15 December 1904, almost four years after...

was divisive, it was an acknowledgement of the need to set Industrial awards, where all wage earners in one industry enjoyed the same conditions of employment and wages. The Harvester Judgment

Harvester Judgment

The Harvester Judgment was a benchmark legal case for ensuring workers in Australia were paid a fair basic wage. The case had national ramifications and was of international significance....

of 1907 recognised the concept of a basic wage and in 1908 the Federal government also began an old age pension scheme. Thus the new Commonwealth gained recognition as a laboratory for social experimentation and positive liberalism.

Catastrophic droughts plagued some regions in the late 1890s and early 20th century and together with a growing rabbit plague

Rabbits in Australia

In Australia, rabbits are a serious mammalian pest and are an invasive species. Annually, European rabbits cause millions of dollars of damage to crops.-Effects on Australia's ecology:...

, created great hardship in rural Australia. Despite this, a number of writers "imagined a time when Australia would outstrip Britain in wealth and importance, when its open spaces would support rolling acres of farms and factories to match those of the United States. Some estimated the future population at 100 million, 200 million or more." Amongst these was E. J. Brady

E. J. Brady

E. J. Brady was an Australian poet.He was born at Carcoar, New South Wales, and was educated both in the United States and Sydney...

, whose 1918 book Australia Unlimited described Australia’s inland as ripe for development and settlement, "destined one day to pulsate with life."

Religion

In the early years of the century the Church of England in AustraliaAnglican Church of Australia

The Anglican Church of Australia is a member church of the Anglican Communion. It was previously officially known as the Church of England in Australia and Tasmania...

transformed itself in its patterns of worship, in the internal appearances of its churches, and in the forms of piety recommended by its clergy. The changes represented a heightened emphasis on the sacraments and were introduced by younger clergy trained in England and inspired by the Oxford and Anglo-Catholic movements. The church's women and its upper and middle class parishes were most supportive, overcoming the reluctance of some of the men. The changes were widely adopted by the 1920s, making the Church of England more self-consciously "Anglican" and distinct from other Protestant churches. Controversy erupted, especially in New South Wales, between the politically liberal proponents of the Social Gospel

Social Gospel

The Social Gospel movement is a Protestant Christian intellectual movement that was most prominent in the early 20th century United States and Canada...

, who wanted more Church attention to the social ills of society, and conservative elements. The opposition of the strong conservative evangelical forces within the Sydney diocese limited the liberals during the 1930s, but their ideas contributed to the formation of the influential post-World War II Christian Social Order Movement.

Attempts to unite the Congregationalist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches failed in 1901-13 and again in 1917-25; they succeeded only in 1977, with the organisation of the Uniting Church in Australia

Uniting Church in Australia

The Uniting Church in Australia was formed on 22 June 1977 when many congregations of the Methodist Church of Australasia, the Presbyterian Church of Australia and the Congregational Union of Australia came together under the Basis of Union....

. The efforts early in the century were impeded by weak organization within each denomination. Interdenominational differences over organization, the status of the ministry, and (to a lesser extent) doctrine also stood in the way. By 1920, the theological liberalism of unionist leaders made the entire movement suspect to orthodox members, especially Presbyterians. Most important was the opposition and apathy of the general membership of the churches. The leaders who designed plans for union had ignored the laity in the decision-making process and had failed to develop practical cooperation at the local level.

Australia's Catholic Church was based, until fairly late in the 20th century, upon working-class Irish communities. Patrick Cardinal Moran (1830–1911), the Archbishop of Sydney 1884–1911, believed that Catholicism would flourish with the emergence of the new nation through Federation in 1901, provided that his people rejected "contamination" from foreign influences, such as anarchism, socialism, modernism and secularism. Moran distinguished between European socialism as an atheistic movement and those Australians calling themselves "socialists;" he approved the objectives of the latter while feeling that the European model was not a real danger in Australia. Moran's outlook reflected his whole-hearted acceptance of Australian democracy and his belief in the country as different and freer than the old societies from which its people had come. Moran thus welcomed the Labor Party, and the Church stood with it in opposing conscription in the referenda of 1916 and 1917. The hierarchy had close ties to Rome, which encouraged the bishops to support the British Empire and emphasize Marian piety.

First World War

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

between 1914 and 1918. Thousands lost their lives at Gallipoli

Battle of Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the Dardanelles Campaign or the Battle of Gallipoli, took place at the peninsula of Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916, during the First World War...

, on the Turkish

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

coast and many more in France. Both Australian victories and losses on World War I battlefields contribute significantly to Australia's national identity. By war's end, over 60,000 Australians had died during the conflict and 160,000 were wounded, a high proportion of the 330,000 who had fought overseas.

Australia's annual holiday to remember its war dead is held on ANZAC Day

ANZAC Day

Anzac Day is a national day of remembrance in Australia and New Zealand, commemorated by both countries on 25 April every year to honour the members of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps who fought at Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. It now more broadly commemorates all...

, 25 April, each year, the date of the first landings at Gallipoli, in Turkey, in 1915, as part of the allied invasion that ended in military defeat. Bill Gammage

Bill Gammage

William Leonard "Bill" Gammage AM is an Australian academic historian, Adjunct Professor and Senior Research Fellow at the Humanities Research Centre of Australian National University....

has suggested that the choice of 25 April has always meant much to Australians because at Gallipoli, "the great machines of modern war were few enough to allow ordinary citizens to show what they could do." In France, between 1916 and 1918, "where almost seven times as many (Australians) died,... the guns showed cruelly, how little individuals mattered."

The Sydney Morning Herald

The Sydney Morning Herald

The Sydney Morning Herald is a daily broadsheet newspaper published by Fairfax Media in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1831 as the Sydney Herald, the SMH is the oldest continuously published newspaper in Australia. The newspaper is published six days a week. The newspaper's Sunday counterpart, The...

referred to the outbreak of war as Australia's "Baptism of Fire." 8,141 men were killed in 8 months of fighting at Gallipoli

Battle of Gallipoli

The Gallipoli Campaign, also known as the Dardanelles Campaign or the Battle of Gallipoli, took place at the peninsula of Gallipoli in the Ottoman Empire between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916, during the First World War...

, on the Turkish

Turkey

Turkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

coast. After the Australian Imperial Forces

First Australian Imperial Force

The First Australian Imperial Force was the main expeditionary force of the Australian Army during World War I. It was formed from 15 August 1914, following Britain's declaration of war on Germany. Generally known at the time as the AIF, it is today referred to as the 1st AIF to distinguish from...

(AIF) was withdrawn in late 1915, and enlarged to five divisions, most were moved to France to serve under British command.

The AIF's first experience of warfare on the Western Front

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

was also the most costly single encounter in Australian military history. In July 1916, at Fromelles

Battle of Fromelles

The Battle of Fromelles, sometimes known as the Action at Fromelles or the Battle of Fleurbaix , occurred in France between 19 July and 20 July 1916, during World War I...

, in a diversionary attack during the Battle of the Somme, the AIF suffered 5,533 killed or wounded in 24 hours. Sixteen months later, the five Australian divisions became the Australian Corps

Australian Corps

The Australian Corps was a World War I army corps that contained all five Australian infantry divisions serving on the Western Front. It was the largest corps fielded by the British Empire army in France...

, first under the command of General Birdwood

William Birdwood, 1st Baron Birdwood

Field Marshal William Riddell Birdwood, 1st Baron Birdwood, GCB, GCSI, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, CIE, DSO was a First World War British general who is best known as the commander of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps during the Gallipoli Campaign in 1915.- Youth and early career :Birdwood was born...

, and later the Australian General Sir John Monash

John Monash

General Sir John Monash GCMG, KCB, VD was a civil engineer who became the Australian military commander in the First World War. He commanded the 13th Infantry Brigade before the War and then became commander of the 4th Brigade in Egypt shortly after the outbreak of the War with whom he took part...

. Two bitterly fought and divisive conscription referendums

Conscription in Australia

Conscription in Australia, or mandatory military service also known as National Service, has a controversial history dating back to the first years of nationhood...

were held in Australia in 1916 and 1917. Both failed, and Australia's army remained a volunteer force. Monash's approach to the planning of military action was meticulous, and unusual for military thinkers of the time. His first operation at the relatively small Battle of Hamel

Battle of Hamel

The Battle of Hamel was a successful attack launched by the Australian Corps of the Australian Imperial Force and several American units against German positions in and around the town of Hamel in northern France during World War I....

demonstrated the validity of his approach and later actions before the Hindenburg Line in 1918 confirmed it.

In 1919, Prime Minister Billy Hughes

Billy Hughes

William Morris "Billy" Hughes, CH, KC, MHR , Australian politician, was the seventh Prime Minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923....

and former Prime Minister Joseph Cock travelled to Paris to attend the Versailles peace conference

Paris Peace Conference, 1919

The Paris Peace Conference was the meeting of the Allied victors following the end of World War I to set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers following the armistices of 1918. It took place in Paris in 1919 and involved diplomats from more than 32 countries and nationalities...

. Hughes's signing of the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

on behalf of Australia was the first time Australia had signed an international treaty. Hughes demanded heavy reparations from Germany and frequently clashed with U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

. At one point Hughes declared: "I speak for 60 000 [Australian] dead". He went on to ask of Wilson; "How many do you speak for?"

Hughes demanded that Australia have independent representation within the newly formed League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

and was the most prominent opponent of the inclusion of the Japanese racial equality proposal, which as a result of lobbying by him and others was not included in the final Treaty, deeply offending Japan. Hughes was concerned by the rise of Japan. Within months of the declaration of the European War in 1914; Japan, Australia and New Zealand seized all German possessions in the South West Pacific. Though Japan occupied German possessions with the blessings of the British, Hughes was alarmed by this policy. In 1919 at the Peace Conference the Dominion leaders, New Zealand, South Africa and Australia argued their case to keep their occupied German possessions of German Samoa, German South West Africa, and German New Guinea; these territories were given a "Class C Mandates" to the respective Dominions. In a same-same deal Japan obtained control over its occupied German possessions, north of the equator.

In 1916 the Labor Prime Minister, Billy Hughes

Billy Hughes

William Morris "Billy" Hughes, CH, KC, MHR , Australian politician, was the seventh Prime Minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923....

, decided that conscription

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

was necessary if the strength of Australia's military forces at the front was to be maintained. The Labor Party and the trade unions were bitterly opposed to conscription, and Hughes and his followers were expelled from the party when they refused to back down. In 1916 and again in 1917 the Australian people voted against conscription in national plebiscites. (See History of Australian Conscription) Hughes united with the Liberals to form the Nationalist Party

Nationalist Party of Australia

The Nationalist Party of Australia was an Australian political party. It was formed on 17 February 1917 from a merger between the conservative Commonwealth Liberal Party and the National Labor Party, the name given to the pro-conscription defectors from the Australian Labor Party led by Prime...

, and remained in office until 1923, when he was succeeded by Stanley Bruce

Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, CH, MC, FRS, PC , was an Australian politician and diplomat, and the eighth Prime Minister of Australia. He was the second Australian granted an hereditary peerage of the United Kingdom, but the first whose peerage was formally created...

. Labor remained weak and divided through the 1920s. The new Country Party

National Party of Australia

The National Party of Australia is an Australian political party.Traditionally representing graziers, farmers and rural voters generally, it began as the The Country Party, but adopted the name The National Country Party in 1975, changed to The National Party of Australia in 1982. The party is...

took many country voters away from Labor, and in 1923 the Country Party formed a coalition government with the Nationalists.

The 1920s

Billy Hughes

William Morris "Billy" Hughes, CH, KC, MHR , Australian politician, was the seventh Prime Minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923....

led a new conservative force, the Nationalist Party

Nationalist Party of Australia

The Nationalist Party of Australia was an Australian political party. It was formed on 17 February 1917 from a merger between the conservative Commonwealth Liberal Party and the National Labor Party, the name given to the pro-conscription defectors from the Australian Labor Party led by Prime...

, formed from the old Liberal party

Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Commonwealth Liberal Party was a political movement active in Australia from 1909 to 1916, shortly after federation....

and breakaway elements of Labor (of which he was the most prominent), after the deep and bitter split over Conscription

Conscription in Australia

Conscription in Australia, or mandatory military service also known as National Service, has a controversial history dating back to the first years of nationhood...

. An estimated 12,000 Australians died as a result of the Spanish flu pandemic of 1919, almost certainly brought home by returning soldiers.

Following the success of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia the Communist Party of Australia

Communist Party of Australia

The Communist Party of Australia was founded in 1920 and dissolved in 1991; it was succeeded by the Socialist Party of Australia, which then renamed itself, becoming the current Communist Party of Australia. The CPA achieved its greatest political strength in the 1940s and faced an attempted...

was formed in 1920 and, though remaining electorally insignificant, it obtained some influence in the Trade Union

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

movement and was banned during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

for its support for the Hitler-Stalin Pact and the Menzies Government

Robert Menzies

Sir Robert Gordon Menzies, , Australian politician, was the 12th and longest-serving Prime Minister of Australia....

unsuccessfully tried to ban it again during the Korean War

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

. Despite splits, the party remained active until its dissolution at the end of the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

.

The Country Party (today's National Party

National Party of Australia

The National Party of Australia is an Australian political party.Traditionally representing graziers, farmers and rural voters generally, it began as the The Country Party, but adopted the name The National Country Party in 1975, changed to The National Party of Australia in 1982. The party is...

) formed in 1920 to promulgate its version of agrarianism

Agrarianism

Agrarianism has two common meanings. The first meaning refers to a social philosophy or political philosophy which values rural society as superior to urban society, the independent farmer as superior to the paid worker, and sees farming as a way of life that can shape the ideal social values...

, which it called "Countrymindedness". The goal was to enhance the status of the graziers (operators of big sheep ranches) and small farmers, and secure subsidies for them. Enduring longer than any other major party save the Labor party, it has generally operated in Coalition

Coalition (Australia)

The Coalition in Australian politics refers to a group of centre-right parties that has existed in the form of a coalition agreement since 1922...

with the Liberal Party

Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is an Australian political party.Founded a year after the 1943 federal election to replace the United Australia Party, the centre-right Liberal Party typically competes with the centre-left Australian Labor Party for political office...

(since the 1940s), becoming a major party of government in Australia - particularly in Queensland.

Other significant after-effects of the war included ongoing industrial unrest, which included the 1923 Victorian Police strike

1923 Victorian Police strike

The 1923 Victorian Police strike occurred in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. On the eve of the Melbourne Spring Racing Carnival in November 1923, half the police force in Melbourne went on strike over the operation of a supervisory system using labour spies...

. Industrial disputes characterised the 1920s in Australia. Other major strikes occurred on the waterfront, in the coalmining and timber industries in the late 1920s. The union movement had established the Australian Council of Trade Unions

Australian Council of Trade Unions

The Australian Council of Trade Unions is the largest peak body representing workers in Australia. It is a national trade union centre of 46 affiliated unions.-History:The ACTU was formed in 1927 as the "Australian Council of Trade Unions"...

(ACTU) in 1927 in response to the Nationalist government's efforts to change working conditions and reduce the power of the unions.

Jazz

Jazz

Jazz is a musical style that originated at the beginning of the 20th century in African American communities in the Southern United States. It was born out of a mix of African and European music traditions. From its early development until the present, jazz has incorporated music from 19th and 20th...

music, entertainment culture, new technology and consumerism that characterised the 1920s in the USA was, to some extent, also found in Australia. Prohibition

Prohibition

Prohibition of alcohol, often referred to simply as prohibition, is the practice of prohibiting the manufacture, transportation, import, export, sale, and consumption of alcohol and alcoholic beverages. The term can also apply to the periods in the histories of the countries during which the...

was not implemented in Australia, though anti-alcohol forces were successful in having hotels closed after 6 pm, and closed altogether in a few city suburbs.

The fledgling film industry declined through the decade, over 2 million Australians attending cinemas weekly at 1250 venues. A Royal Commission

Royal Commission

In Commonwealth realms and other monarchies a Royal Commission is a major ad-hoc formal public inquiry into a defined issue. They have been held in various countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Saudi Arabia...

in 1927 failed to assist and the industry that had begun so brightly with the release of the world's first feature film, The Story of the Kelly Gang

The Story of the Kelly Gang

The Story of the Kelly Gang is a 1906 Australian film that traces the life of the legendary bushranger Ned Kelly . It was written and directed by Charles Tait. The film ran for more than an hour, and was the longest narrative film yet seen in Australia, and the world. Its approximate reel length...

(1906), atrophied until its revival in the 1970s

Australian New Wave

The Australian New Wave was an era of resurgence in worldwide popularity of Australian cinema...

.

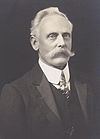

Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, CH, MC, FRS, PC , was an Australian politician and diplomat, and the eighth Prime Minister of Australia. He was the second Australian granted an hereditary peerage of the United Kingdom, but the first whose peerage was formally created...

became Prime Minister in 1923, when members of the Nationalist Party Government voted to remove W.M. Hughes. Speaking in early 1925, Bruce summed up the priorities and optimism of many Australians, saying that "men, money and markets accurately defined the essential requirements of Australia" and that he was seeking such from Britain. The migration campaign of the 1920s, operated by the Development and Migration Commission, brought almost 300,000 Britons to Australia, although schemes to settle migrants and returned soldiers

Soldier settlement (Australia)

Soldier settlement refers to the occupation and settlement of land throughout parts of Australia by returning discharged soldiers under schemes administered by the State Governments after World Wars I and II.- World War I :...

"on the land" were generally not a success. "The new irrigation areas in Western Australia

Western Australia

Western Australia is a state of Australia, occupying the entire western third of the Australian continent. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Great Australian Bight and Indian Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east and South Australia to the south-east...

and the Dawson Valley of Queensland

Queensland

Queensland is a state of Australia, occupying the north-eastern section of the mainland continent. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Australia and New South Wales to the west, south-west and south respectively. To the east, Queensland is bordered by the Coral Sea and Pacific Ocean...

proved disastrous"

In Australia, the costs of major investment had traditionally been met by state and Federal governments and heavy borrowing from overseas was made by the governments in the 1920s. A Loan Council

Loan Council

The Loan Council is an Australian organisation that co-ordinates the financial borrowing arrangements of the Commonwealth of Australia and also the States; including New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania, Northern Territory and the Australian Capital...

set up in 1928 to coordinate loans, three quarters of which came from overseas. Despite Imperial preference

Imperial Preference

Imperial Preference was a proposed system of reciprocally-levelled tariffs or free trade agreements between the dominions and colonies within the British Empire...

, a balance of trade was not successfully achieved with Britain. "In the five years from 1924... to... 1928, Australia bought 43.4% of its imports from Britain and sold 38.7% of its exports. Wheat and wool made up more than two thirds of all Australian exports," a dangerous reliance on just two export commodities.

Australia embraced the new technologies of transport and communication. Coastal sailing ships were finally abandoned in favour of steam, and improvements in rail and motor transport heralded dramatic changes in work and leisure. In 1918 there were 50,000 cars and lorries in the whole of Australia. By 1929 there were 500,000. The stage coach company Cobb and Co

Cobb and Co

Cobb and Co is the name of a transportation company in Australia. It was prominent in the late 19th century when it operated stagecoaches to many areas in the outback and at one point in several other countries, as well....

, established in 1853, finally closed in 1924. In 1920, the Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Service (to become the Australian airline QANTAS

Qantas

Qantas Airways Limited is the flag carrier of Australia. The name was originally "QANTAS", an initialism for "Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services". Nicknamed "The Flying Kangaroo", the airline is based in Sydney, with its main hub at Sydney Airport...

) was established. The Reverend John Flynn, founded the Royal Flying Doctor Service, the world's first air ambulance in 1928. Dare devil pilot, Sir Charles Kingsford Smith

Charles Kingsford Smith

Sir Charles Edward Kingsford Smith MC, AFC , often called by his nickname Smithy, was an early Australian aviator. In 1928, he earned global fame when he made the first trans-Pacific flight from the United States to Australia...

pushed the new flying machines to the limit, completing a round Australia circuit in 1927 and in 1928 traversed the Pacific Ocean, via Hawaii and Fiji from the USA to Australia in the aircraft Southern Cross. He went on to global fame and a series of aviation records before vanishing on a night flight to Singapore in 1935.

Dominion status

Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Passed on 11 December 1931, the Act established legislative equality for the self-governing dominions of the British Empire with the United Kingdom...

. This formalised the Balfour Declaration of 1926, a report resulting from the 1926 Imperial Conference

1926 Imperial Conference

The 1926 Imperial Conference was the sixth Imperial Conference held amongst the Prime Ministers of the dominions of the British Empire. It was held in London from 19 October to 22 November 1926...

of British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

leaders in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, which defined Dominion

Dominion

A dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

s of the British empire in the following way

However, Australia did not ratify the Statute of Westminster

Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Passed on 11 December 1931, the Act established legislative equality for the self-governing dominions of the British Empire with the United Kingdom...

until 1942. According to historian Frank Crowley

Frank Crowley

Frank Crowley is a retired IrishFine Gael party politician and Teachta Dála for Cork North West.Crowley first stood for election in the Cork Mid constituency at the 1977 general election...

, this was because Australians had little interest in redefining their relationship with Britain until the crisis of World War II.

The Australia Act 1986

Australia Act 1986

The Australia Act 1986 is the name given to a pair of separate but related pieces of legislation: one an Act of the Commonwealth Parliament of Australia, the other an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom...

removed any remaining links between the British Parliament and the Australian states.

From 1 February 1927 until 12 June 1931, the Northern Territory was divided up as North Australia

North Australia

North Australia can refer to a former territory, a former colony or a proposed state which would replace the current Northern Territory.-Colony :...

and Central Australia

Central Australia

Central Australia/Alice Springs Region is one of the five regions in the Northern Territory. The term Central Australia is used to describe an area centred on Alice Springs in Australia. It is sometimes referred to as Centralia; likewise the people of the area are sometimes called Centralians...

at latitude 20°S

20th parallel south

The 20th parallel south is a circle of latitude that is 20 degrees south of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses the Atlantic Ocean, Africa, the Indian Ocean, Australasia, the Pacific Ocean and South America....

. New South Wales has had one further territory surrendered, namely Jervis Bay Territory

Jervis Bay Territory

The Jervis Bay Territory is a territory of the Commonwealth of Australia. It was surrendered by the state of New South Wales to the Commonwealth Government in 1915 so that the Federal capital at Canberra would have "access to the sea"....

comprising 6,677 hectares, in 1915. The external territories were added: Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island is a small island in the Pacific Ocean located between Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia. The island is part of the Commonwealth of Australia, but it enjoys a large degree of self-governance...

(1914); Ashmore Island, Cartier Islands

Cartier Islands

Cartier Island is an uninhabited and unvegetated sand cay in a platform reef in the Timor Sea north of Australia and south of Indonesia. It is located at 12°31'S 123°33'E, on the edge of the Sahul Shelf, about 300 kilometres off the north west coast of Western Australia, 200 kilometres south of the...

(1931); the Australian Antarctic Territory

Australian Antarctic Territory

The Australian Antarctic Territory is a part of Antarctica. It was claimed by the United Kingdom and placed under the authority of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1933. It is the largest territory of Antarctica claimed by any nation...

transferred from Britain (1933); Heard Island, McDonald Islands, and Macquarie Island

Macquarie Island

Macquarie Island lies in the southwest corner of the Pacific Ocean, about half-way between New Zealand and Antarctica, at 54°30S, 158°57E. Politically, it has formed part of the Australian state of Tasmania since 1900 and became a Tasmanian State Reserve in 1978. In 1997 it became a world heritage...

transferred to Australia from Britain (1947).

The Federal Capital Territory (FCT) was formed from New South Wales in 1911 to provide a location for the proposed new federal capital of Canberra

Canberra

Canberra is the capital city of Australia. With a population of over 345,000, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory , south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Melbourne...

(Melbourne

Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

was the seat of government from 1901 to 1927). The FCT was renamed the Australian Capital Territory

Australian Capital Territory

The Australian Capital Territory, often abbreviated ACT, is the capital territory of the Commonwealth of Australia and is the smallest self-governing internal territory...

(ACT) in 1938. The Northern Territory

Northern Territory

The Northern Territory is a federal territory of Australia, occupying much of the centre of the mainland continent, as well as the central northern regions...

was transferred from the control of the South Australian government to the Commonwealth in 1911.

Great Depression: the 1930s

Australia's dependence on primary exports such as wheat and wool was cruelly exposed by the Great DepressionGreat Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

of the 1930s, which produced unemployment and destitution even greater than those seen during the 1890s. The Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

under James Scullin

James Scullin

James Henry Scullin , Australian Labor politician and the ninth Prime Minister of Australia. Two days after he was sworn in as Prime Minister, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 occurred, marking the beginning of the Great Depression and subsequent Great Depression in Australia.-Early life:Scullin was...

won the 1929 election in a landslide, but was quite unable to cope with the Depression. Labor split into three factions and then lost power in 1932 to a new conservative party, the United Australia Party

United Australia Party

The United Australia Party was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. It was the political successor to the Nationalist Party of Australia and predecessor to the Liberal Party of Australia...

(UAP) led by Joseph Lyons

Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons, CH was an Australian politician. He was Labor Premier of Tasmania from 1923 to 1928 and a Minister in the James Scullin government from 1929 until his resignation from the Labor Party in March 1931...

, and did not return to office until 1941. Australia made a very slow recovery from the Depression during the late 1930s. Lyons died in 1939 and was succeeded by Robert Menzies.

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

accounted for almost half Australia’s accumulated debt by December 1927. The situation caused alarm amongst a few politicians and economists, notably Edward Shann of the University of Western Australia

University of Western Australia

The University of Western Australia was established by an Act of the Western Australian Parliament in February 1911, and began teaching students for the first time in 1913. It is the oldest university in the state of Western Australia and the only university in the state to be a member of the...

, but most political, union and business leaders were reluctant to admit to serious problems. In 1926, Australian Finance magazine described loans as occurring with a "disconcerting frequency" unrivalled in the British Empire: "It may be a loan to pay off maturing loans or a loan to pay the interest on existing loans, or a loan to repay temporary loans from the bankers.... Thus, well before the Wall Street Crash of 1929

Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 , also known as the Great Crash, and the Stock Market Crash of 1929, was the most devastating stock market crash in the history of the United States, taking into consideration the full extent and duration of its fallout...

, the Australian economy was already facing significant difficulties. As the economy slowed in 1927, so did manufacturing and the country slipped into recession as profits slumped and unemployment rose.

At elections held in October 1929 the Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

was swept to power in a landslide, the former Prime Minister Stanley Bruce

Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, CH, MC, FRS, PC , was an Australian politician and diplomat, and the eighth Prime Minister of Australia. He was the second Australian granted an hereditary peerage of the United Kingdom, but the first whose peerage was formally created...

losing his own seat. The new Prime Minister James Scullin

James Scullin

James Henry Scullin , Australian Labor politician and the ninth Prime Minister of Australia. Two days after he was sworn in as Prime Minister, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 occurred, marking the beginning of the Great Depression and subsequent Great Depression in Australia.-Early life:Scullin was...

and his largely inexperienced Government were almost immediately faced with a series of crises. Hamstrung by their lack of control of the Senate, a lack of control over the Banking system and divisions within their Party over how best to deal with the situation, the government was forced to accept solutions that eventually split the party, as it had in 1917. Some gravitated to New South Wales Premier Lang, other to Prime Minister Scullin.

Various "plans" to resolve the crisis were suggested; Sir Otto Niemeyer

Otto Niemeyer

Sir Otto Ernst Niemeyer, GBE, KCB was financial controller at the Treasury and a director at the Bank of England. He was also treasurer of the National Association of Mental Health post World War II...

, a representative of the English banks who visited in mid 1930, proposed a deflationary plan, involving cuts to government spending and wages. Treasurer Ted Theodore

Ted Theodore

Edward Granville Theodore was an Australian politician. He was Premier of Queensland 1919–25, a federal politician representing a New South Wales seat 1927–31, and Federal Treasurer 1929–30.-Early life:...

proposed a mildly inflationary plan, while the Labor Premier of New South Wales, Jack Lang

Jack Lang (Australian politician)

John Thomas Lang , usually referred to as J.T. Lang during his career, and familiarly known as "Jack" and nicknamed "The Big Fella" was an Australian politician who was Premier of New South Wales for two terms...

, proposed a radical plan which repudiated overseas debt. The "Premier's Plan" finally accepted by federal and state governments in June 1931, followed the deflationary model advocated by Niemeyer and included a reduction of 20% in government spending, a reduction in bank interest rates and an increase in taxation. In March 1931, Lang announced that interest due in London would not be paid and the Federal government stepped in to meet the debt. In May, the Government Savings Bank of New South Wales was forced to close. The Melbourne Premiers' Conference agreed to cut wages and pensions as part of a severe deflationary policy but Lang, renounced the plan. The grand opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge

Sydney Harbour Bridge

The Sydney Harbour Bridge is a steel through arch bridge across Sydney Harbour that carries rail, vehicular, bicycle and pedestrian traffic between the Sydney central business district and the North Shore. The dramatic view of the bridge, the harbour, and the nearby Sydney Opera House is an iconic...

in 1932 provided little respite to the growing crisis straining the young federation. With multi-million pound debts mounting, public demonstrations and move and counter-move by Lang and the Scullin, then Lyons federal governments, the Governor of New South Wales, Philip Game

Philip Game

Air Vice-Marshal Sir Philip Woolcott Game GCB, GCVO, GBE, KCMG, DSO was a British Royal Air Force commander, who later served as Governor of New South Wales and Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis...

, had been examining Lang's instruction not to pay money into the Federal Treasury. Game judged it was illegal. Lang refused to withdraw his order and, on 13 May, he was dismissed by Governor Game

Lang Dismissal Crisis

The 1932 dismissal of Premier Jack Lang by New South Wales Governor Philip Game was the first real constitutional crisis in Australia. Lang remains the only Australian Premier to be removed from office by his Governor, using the Reserve Powers of the Crown....

. At June elections, Lang Labor's seats collapsed.

May 1931 had seen the creation of a new conservative political force, the United Australia Party

United Australia Party

The United Australia Party was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. It was the political successor to the Nationalist Party of Australia and predecessor to the Liberal Party of Australia...

formed by breakaway members of the Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

combining with the Nationalist Party

Nationalist Party of Australia

The Nationalist Party of Australia was an Australian political party. It was formed on 17 February 1917 from a merger between the conservative Commonwealth Liberal Party and the National Labor Party, the name given to the pro-conscription defectors from the Australian Labor Party led by Prime...

. At Federal elections in December 1931, the United Australia Party, led by former Labor member Joseph Lyons

Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons, CH was an Australian politician. He was Labor Premier of Tasmania from 1923 to 1928 and a Minister in the James Scullin government from 1929 until his resignation from the Labor Party in March 1931...

, easily won office. They remained in power under Lyons through Australia's recovery from the Great Depression and into the early stages of the World War II under Robert Menzies.

Anne Henderson

Anne Henderson is an Australian writer, best known as the Deputy Director of The Sydney Institute and editor of The Sydney Papers....

of the Sydney Institute

Sydney Institute

The Sydney Institute, founded in 1989, is a privately funded, conservative, Australian current affairs forum. The Sydney Institute took over the resources of the Sydney Institute of Public Affairs which ceased activity in the late 1980s...

, Lyons held a steadfast belief in the need to balance budgets, lower costs to business and restore confidence and the Lyons period gave Australia stability and eventual growth between the drama of the Depression and the outbreak of the Second World War. A lowering of wages was enforced and industry tariff protections maintained, which together with cheaper raw materials during the 1930s saw a shift from agriculture to manufacturing as the chief employer of the Australian economy - a shift which was consolidated by increased investment by the commonwealth government into defence and armaments manufacture. Lyons saw restoration of Australia's exports as the key to economic recovery. The Lyons government

Lyons Government

The Lyons Government was the federal Executive Government of Australia led by Prime Minister Joseph Lyons. It was made up of members of a United Australia Party in the Australian Parliament from January 1932 until the death of Joseph Lyons in 1939. Lyons negotiated a coalition with the Country...

has often been credited with steering recovery from the depression, although just how much of this was owed to their policies remains contentious. Stuart Macintyre

Stuart Macintyre

Stuart Forbes Macintyre , Australian historian, academic and public intellectual, is a former Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne. He has been voted one of Australia's most influential public intellectuals...

also points out that although Australian GDP

Gross domestic product

Gross domestic product refers to the market value of all final goods and services produced within a country in a given period. GDP per capita is often considered an indicator of a country's standard of living....

grew from £386.9 million to £485.9 million between 1931-2 and 1938-9, real domestic product per head of population was still "but a few shillings greater in 1938-39 (£70.12), than it had been in 1920-21 (£70.04).

There is debate over the extent reached by unemployment in Australia, often cited as peaking at 29% in 1932. "Trade Union figures are the most often quoted, but the people who were there…regard the figures as wildly understating the extent of unemployment" wrote historian Wendy Lowenstein

Wendy Lowenstein

Wendy Lowenstein was an Australian historian, author and teacher notable for her recording of people's everyday experiences and her advocacy of left wing politics...

in her collection of oral histories of the Depression. However, David Potts argues that "over the last thirty years …historians of the period have either uncritically accepted that figure (29% in the peak year 1932) including rounding it up to ‘a third,’ or they have passionately argued that a third is far too low." Potts suggests a peak national figure of 25% unemployed.

Extraordinary sporting successes did something to alleviate the spirits of Australians during the economic downturn. In a Sheffield Shield cricket match at the Sydney Cricket Ground

Sydney Cricket Ground

The Sydney Cricket Ground is a sports stadium in Sydney in Australia. It is used for Australian football, Test cricket, One Day International cricket, some rugby league and rugby union matches and is the home ground for the New South Wales Blues cricket team and the Sydney Swans of the Australian...

in 1930, Don Bradman, a young New South Welshman of just 21 years of age wrote his name into the record books by smashing the previous highest batting score in first-class cricket with 452 runs not out in just 415 minutes. The rising star's world beating cricketing exploits were to provide Australians with much needed joy to Australians through the emerging Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

and post-World War II recovery. Between 1929 and 1931 the legendary racehorse Phar Lap

Phar Lap

Phar Lap was a champion Thoroughbred racehorse whose achievements captured the public's imagination during the early years of the Great Depression. Foaled in New Zealand, he was trained and raced in Australia. Phar Lap dominated Australian racing during a distinguished career, winning a Melbourne...

dominated Australia's racing industry, at one stage winning fourteen races in a row. Famous victories included the 1930 Melbourne Cup

Melbourne Cup

The Melbourne Cup is Australia's major Thoroughbred horse race. Marketed as "the race that stops a nation", it is a 3,200 metre race for three-year-olds and over. It is the richest "two-mile" handicap in the world, and one of the richest turf races...

, following an assassination attempt and carrying 9 stone 12 pounds weight. Phar Lap sailed for the United States in 1931, going on to win North America's richest race, the Agua Caliente Handicap

Agua Caliente Handicap

The Agua Caliente Handicap is a defunct thoroughbred horse race that was once the premier event at Agua Caliente Racetrack in Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico, and the richest race in North America...

in 1932. Soon after, on the cusp of US success, Phar Lap developed suspicious symptoms and died. Theories swirled that the champion race horse had been poisoned and a devoted Australian public went in to shock. The 1938 British Empire Games

1938 British Empire Games

The 1938 British Empire Games was the third British Empire Games, the Commonwealth Games being the modern-day equivalent. Held in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia from February 5–12, 1938, they were timed to coincide with Sydney's sesqui-centenary...

were held in Sydney from 5–12 February, timed to coincide with Sydney's sesqui-centenary (150 years since the foundation of British settlement in Australia).

Second World War

.jpg)

Defence policy in the 1930s

Defence issues became increasingly prominent in public affairs with the rise of fascismFascism

Fascism is a radical authoritarian nationalist political ideology. Fascists seek to rejuvenate their nation based on commitment to the national community as an organic entity, in which individuals are bound together in national identity by suprapersonal connections of ancestry, culture, and blood...

in Europe and militant Japan

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

in Asia. Prime Minister Lyons sent veteran World War I Prime Minister Billy Hughes

Billy Hughes

William Morris "Billy" Hughes, CH, KC, MHR , Australian politician, was the seventh Prime Minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923....

to represent Australia at the 1932 League of Nations Assembly in Geneva and in 1934 Hughes became Minister for Health and Repatriation. Later Lyons appointed him Minister for External Affairs, however Hughes was forced to resign in 1935 after his book Australia and the War Today exposed a lack of preparation in Australia for what Hughes correctly supposed to be a coming war. Soon after, the Lyons government tripled the defence budget. With Western Powers developing a policy of appeasement

Appeasement

The term appeasement is commonly understood to refer to a diplomatic policy aimed at avoiding war by making concessions to another power. Historian Paul Kennedy defines it as "the policy of settling international quarrels by admitting and satisfying grievances through rational negotiation and...

to try to satisfy the demands of Europe's new dictators without war, Prime Minister Lyons sailed for Britain in 1937 for the coronation of King George VI

George VI of the United Kingdom

George VI was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death...

, en route conducting a diplomatic mission to Italy on behalf of the British Government, visiting Benito Mussolini

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

with assurances of British friendship.

Until the late 1930s, defence was not a significant issue for Australians. At the 1937 elections, both political parties advocated increased defence spending, in the context of increased Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

ese aggression in China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

and Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

’s aggression in Europe

Europe