.gif)

History of Pomerania (1933–1945)

Encyclopedia

History of Pomerania covers the History of Pomerania

before and during World War II

.

In 1933, the German Province of Pomerania like all of Germany came under control of the Nazi regime

. During the following years, the Nazis led by Gauleiter

Franz Schwede-Coburg manifested their power through the process known as Gleichschaltung

and repression of their opponents.

At the same time, the Pomeranian Voivodeship

was part of the Second Polish Republic

, led by Józef Piłsudski. With respect to Polish Pomerania Nazi diplomacy as parts of its initial attempts to subordinate Poland into Anti-Comintern Pact aimed at incorporation of the Free City of Danzig

into the Third Reich and an extra-territorial transit route through Polish territory, which was rejected by the Polish government, that feared economic blackmail by Nazi Germany, and reduction to puppet status.

In 1939, the German Wehrmacht

invaded Poland

engaging in series of massacres against the civilian population, the most notable among them being the Mass murders in Piaśnica

. Polish Pomerania was made part of Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia

. The German state set up concentration camps, performed expulsion of the Poles and Jews, and systematically engaged in genocide of people they regarded as Untermensch

(primarily, Jews and ethnic Poles

).

In 1945, Pomerania

was taken by the Red Army

during the East Pomeranian Offensive

and the Battle of Berlin

. Along with the Soviet offensive, atrocities against the German civilian population occurred on a large scale.

, took power in Germany in 1933. By this time, the Second Polish Republic

was led by Józef Piłsudski who ruled the country as an authoritarian democracy. Hitler at first ostentatiously pursued a policy of rapprochement

with Poland, culminating in the ten year Polish-German Non-Aggression Pact of 1934. In the coming years, Germany placed an emphasis on rearmament, to which Poland and other European powers reacted. Initially Nazis were able to achieve their immediate goals of territorial expansion without provoking armed resistance; in 1938 Nazi Germany

annexed Austria

and the Sudetenland

after the Munich Agreement

. In October 1938, Germany tried to get Poland to join the Anti-Comintern Pact

. Poland refused, as the alliance was quickly becoming a sphere of influence for an increasingly powerful Germany.

Following negotiations with Hitler for the Munich Agreement, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

reported that, "He told me privately, and last night he repeated publicly, that after this Sudeten German question is settled, that is the end of Germany's territorial claims in Europe". Almost immediately following the agreement, however, Hitler reneged. The Nazis increased their requests for the incorporation of the Free City of Danzig into the Reich, citing the "protection" of the German majority as a motive.

In November 1938, Danzig's district administrator, Albert Forster

reported to the League of Nations that Hitler had told him Polish frontiers would be guaranteed if the Poles were "reasonable like the Czechs." German State Secretary Ernst von Weizsäcker

reaffirmed this alleged guarantee in December 1938.

The situation regarding the Free City and the Polish Corridor created a number of headaches for German and Polish Customs. The Germans requested the Free City of Danzig

and the construction of an extra-territorial highway (to complete the Reichsautobahn Berlin-Königsberg) and railway through the Polish Corridor, connecting East Prussia to Danzig and Germany proper. Poland agreed on building a German highway and to allow German railway traffic, in return they would extend the non-aggression pact for 25 years.

This seemed to conflict with Hitler's plans and with Poland's rejection of the Anti-Comintern Pact, his desire to either isolate or gain support against the Soviet Union

. German newspapers in Danzig and Nazi Germany played an important role inciting nationalist sentiment; headlines buzzed about how Poland was misusing its economic rights in Danzig and German Danzigers were increasingly subjugated to the will of the Polish state. At the same time, Hitler also offered Poland additional territory as an enticement, such as the possible annexation of Lithuania

, the Memel Territory, Soviet Ukraine

and Czech inhabited lands.

However, Polish leaders continued to fear for the loss of their independence and a shared fate with Czechoslovakia

, although they had also taken part in its partitioning.

Some felt that the Danzig question was inextricably tied to the problems in the Polish Corridor and any settlement regarding Danzig would be one step towards the eventual loss of Poland's access to the sea.

Nevertheless, Hitler's credibility outside of Germany was very low after the occupation of Czechoslovakia.

Hitler used the issue of the status city as pretext for attacking Poland, while explaining during a high level meeting of German military officials in May 1939 that his real goal is obtaining Lebensraum

for Germany, isolating Poles from their Allies in the West and afterwards attacking Poland, thus avoiding the repeat of Czech situation

In 1939, Nazi Germany made another proposal regarding Danzig; the city was to be incorporated into the Reich while the Polish section of the population was to be "evacuated" and resettled elsewhere. Poland was to retain a permanent right to use the seaport and the route through the Polish Corridor was to be constructed. However, the Poles distrusted Hitler and saw the plan as a threat to Polish sovereignty, practically subordinating Poland to the Axis and the Anti-Comintern Bloc while reducing the country to a state of near-servitude.

Additionally, Poland was backed by guarantees of support from both the United Kingdom and France in regard to Danzig.

A revised and less favorable proposal came in the form of an ultimatum

made by the Nazis in late August, after the orders had already been given to attack Poland on September 1, 1939. Nevertheless, at midnight on August 29, Joachim von Ribbentrop

handed British Ambassador Sir Neville Henderson a list of terms which would allegedly ensure peace in regard to Poland. Danzig was to be incorporated into Germany and there was to be a plebiscite in the Polish Corridor; all Poles who were born or settled there since 1919 would have no vote, while all Germans born but not living there would. An exchange of minority populations between the two countries was proposed. If Poland accepted these terms, Germany would agree to the British offer of an international guarantee, which would include the Soviet Union. A Polish plenipotentiary

, with full powers, was to arrive in Berlin and accept these terms by noon the next day. The British Cabinet viewed the terms as "reasonable," except the demand for a Polish Plenipotentiary, which was seen as similar to Czechoslovak President Emil Hácha

accepting Hitler’s terms in mid-March 1939.

When Ambassador Józef Lipski

went to see Ribbentrop on August 30, he was presented with Hitler’s demands. However, he did not have the full power to sign and Ribbentrop ended the meeting. News was then broadcast that Poland had rejected Germany's offer.

to change the Constitution of the Free City of Danzig. The government introduced anti-Semitic

and anti-Catholic

laws, the latter primarily being directed against the newly brought in Poles and Kashubian

inhabitants. The city also served as a training point for members of the German minority within Poland that, recruited by organisations such as the Jungdeutsche Partei ("Young German Party") and the Deutsche Vereinigung ("German Union"), would form the leading cadres of Selbstschutz

, an organisation involved with murder and atrocities during the German invasion of Poland in 1939. As throughout Germany, Jews were increasingly persecuted; the Danzig Great Synagogue

was taken over and demolished by the local authorities in 1939.

, politics in the province was dominated by the nationalist conservative DNVP (German National People's Party). The Nazi party (NSDAP) did not have any significant success at elections, nor did it have a substantial amount of members. The Pomeranian Nazi party was founded by students of the University of Greifswald in 1922, when the NSDAP was officially forbidden. The university's rector Karl Theodor von Vahlen became Gauleiter

(head of the provincial party) in 1924. Soon afterwards, he was fired by the university and went bankrupt. In 1924, the party had 330 members, and in December 1925, 297 members. The party was not present in all of the province. The members were concentrated mainly in Western Pomerania and internally divided. Vahlen retired from the Gauleiter position in 1927 and was replaced by Walther von Corswandt, a Pomeranian knight estate holder.

Corswandt led the party from his estate in Kuntzow. In the 1928 Reichstag

elections, the Nazis got 1,5% of the votes in Pomerania. Party property was partially pawned. In 1929, the party gained 4,1% of the votes. Corswandt was fired after conflicts with the party's leadership and replaced with Wilhelm von Karpenstein, one of the former students who formed the Pomeranian Nazi party in 1922 and since 1929 lawywer in Greifswald

. He moved the headquarters to Stettin and replaced many of the party officials predominantly with young radicals. In the Reichstag elections of September 14, 1930, the party gained a significant 24,3% of the Pomeranian votes and thus became the second strongest party, the strongest still being the DNVP, which however was internally divided in the early 1930s.

In the elections of July 1932, the Nazis gained 48% of the Pomeranian votes, while the DNVP dropped to 15,8%. In March 1933, the NSDAP gained 56.3%.

maltreated their victims. The Pomeranian SA in 1933 had grown to 100,000 members.

Oberpräsident von Halfern retired in 1933, and with him one third of the Landrat and Oberbürgermeister (mayor) officials.

Also in 1933, an election was held for a new provincial parliament, which then had a Nazi majority. Decrees were issued that shifted all issues formerly in responsibility of the parliament to the "Provinzialausschuß" commission, and furthermore, shifted the power to decide on these issues from the "Provinzialausschuß" to the "Oberpräsident" official, although he had to hear the "Provinzialrat" commission before. Once the power was shifted to the Oberpräsident with the Provinzialrat as an advisor, all organs of the "Provinzialverband" ("Provinziallandtag" (parliament), "Provinzialausschuß and all other commissions), the former self-administration of the province, were dissolved except for the downgraded Provinzialrat, which assembled about once a year without making use of its advisory rights. The "Landeshauptmann" position, the Provinzialverband's head, was not abolished. From 1933, Landeshauptmann would be a Nazi who was acting in line with the Oberpräsident. The law entered into force on April 1, 1934.

In 1934, many of the heads of the Pomeranian Nazi-movement were exchanged. SA

leader von Heydebreck was shot in Stadelheim

near Munich

due to his friendship to Röhm

. Gauleiter

von Karpenstein was arrested for two years and banned from Pomerania due to conflicts with the NSDAP headquarters. His substitute, Franz Schwede-Coburg, replaced most of Karpenstein's staff with Corswant's earlier staff, friends of him from Bavaria

, and SS. From the 27 Kreisleiter

officials, 23 were forced out of office by Schwede-Coburg, who became Gauleiter on July 21, and Oberpräsident on July 28, 1934.

As in all of Nazi Germany

, the Nazis established totalitarian control

over the province by Gleichschaltung

.

Resistance groups formed in the economical centers, especially in Stettin, from where most arrests were reported.

Resistance groups formed in the economical centers, especially in Stettin, from where most arrests were reported.

Resistance is also reported from members of the nationalist conservative DNVP. The monarchist Herbert von Bismarck-Lasbeck was forced out of office in 1933. The conservative newspaper Pommersche Tagespost was banned in 1935 after printing an article of monarchist Hans-Joachim von Rohr. In 1936, four members of the DNVP were tried for founding a monarchist organization.

Other DNVP members, who had addressed their opposition already before 1933, were arrested multiple times after the Nazis had taken over. Ewald Kleist-Schmenzin, Karl Magnus von Knebel-Doberitz, and Karl von Zitzewitz were active resistants.

Within the Protestant church, resistant was organized within the Pfarrernotbund

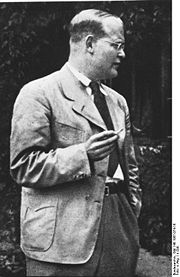

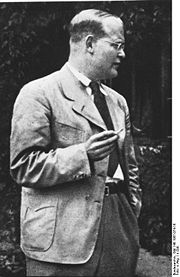

Within the Protestant church, resistant was organized within the Pfarrernotbund

(150 members in late 1933) and Confessing Church

("Bekennende Kirche"), the successor organization, headed by Reinold von Thadden-Trieglaff. In March 1935, 55 priests were arrested. The Confessing Church maintained a preachers' seminar headed by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

in Zingst

, which moved to Finkenwalde in 1935 and to Köslin and Groß Schlönwitz in 1940. Within the Catholic Church, the most prominent resistance member was Greifswald

priest Alfons Wachsmann, who was executed in 1944.

After the failed assassination attempt of Hitler on July 20, 1944, Gestapo

arrested thirteen Pomeranian nobles and one burgher, all knight estate owners. Of those, Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin

had contacted Winston Churchill

in 1938 to inform about the work of the German opposition to the Nazis, and was executed in April 1945. Karl von Zitzewitz had connections to the Kreisauer Kreis group. Among the other arrested were Malte von Veltheim Fürst zu Putbus, who died in a concentration camp, as well as Alexander von Kameke and Oscar Caminecci-Zettuhn, who both were executed.

were made a district of the German Province of Pomerania. Several counties from Mazovia

and Greater Poland

were joined to the Polish Pomeranian Voivodship, and her capital was moved from Toruń to Bydgoszcz (Bromberg).

The dispute between Germany and Poland

The dispute between Germany and Poland

over rights to Free City of Danzig

and land transit through the Polish Corridor

to the exclave of East Prussia

, served as Hitler's pretext for Nazi Germany

's invasion of Poland

, which commenced on September 1, 1939. The strategy

of the Nazi government was to temporarily divide Poland

with Stalin's

Soviet Union

, formalized in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

. In the longer perspective, the Nazis aimed to expand the German "Lebensraum

" in the East, to exploit soil, oil, minerals and workforce from the lands of the Slavs, turning them into a race of slaves destined to serve the German 1000 Year Reich

and its master race

. The fate of other peoples of these territories, notably Jews and Gypsies, was to be annihilation and deportation during the Holocaust

.

When the Nazis started to terrorize Jews, many emigrated. Twenty weeks after the Nazis seized power, the number of Jewish Pomeranians had already dropped by eight percent.

Besides the repressions Jews had to endure in all Nazi Germany

, including the destruction of the Pomeranian synagoges on November 9, 1938 (Reichskristallnacht), all male Stettin Jews were deported to Oranienburg concentration camp

after this event and kept there for several weeks.

On February 12 and 13, 1940, the remaining 1,000 to 1,300 Pomeranian Jews, regardless of sex, age and health, were deported from Stettin and Schneidemühl to the Lublin-Lipowa Reservation, that had been set up following the Nisko Plan

in occupied Poland. Among the deported were intermarried non-Jewish women. The deportation was carried out in an inhumane manner. Despite low temperatures, the carriages were not heated. No food had been allowed to be taken along. The property left behind was liquidated. Up to 300 people perished from the deportation itself. In the Lublin area under Kurt Engel's regime, the people were subject to inhumane treatment, starvation and murder. Only a few survived the war.

Regarding the Jewish community from the Schneidemühl area, JewishGen

with reference to research by Peter Simonstein Cullman says that the widespread belief of the Schneidemühl Jews being deported along with the Stettin Jews is contradicted by the respective files in the Bundesarchiv and USHMM archives. While there were indeed such orders and Jews from the Schneidemühl area were rounded up after 15 February, an intervention of the Association of Jews in Germany (Reichsvereinigung)

resulted in a change of the Nazi plans on 21 February: instead of deportation to the Generalgouvernement like the Stettin Jews, these people were to be deported to places within the Altreich. Deportations to transit and death camps followed.

by the Wehrmacht

on September 1, 1939, which marked the beginning of World War II

, was in part mounted from the Province of Pomerania. General Guderian

's 19th army corps attacked from the Schlochau and Preußisch Friedland areas, which since 1938 belonged to the province ("Grenzmark Posen-Westpreußen").

Initially, the Heinz Guderian

' tank corps was to pass through Pomerelia

(Polish Corridor

) on their way to East Prussia

. The Guderian corps was to regroup there and attack Warsaw

from the east. The Polish opponent was the Army of Pomerania

(Armia Pomorze), defeated in the Battle of Tuchola Forest. Krojanty charge was one of the famous episodes of the operation where the Polish cavalry unit charged and dispersed German infantry, but then run into the machine guns of German hidden armed reconnaissance vehicles. The episode was used in Nazi propaganda

After the initial battles in Pomerelia, the remains of the Polish Army of Pomerania withdrew to the southern bank of the Vistula

river. After defending Toruń (Thorn) for several days, the army withdrew further south under pressure of the overall strained strategic situation, and took part in the main battle of Bzura. On the borders of the Free City of Danzig, there were two fortified Polish points: the Polish post office in Danzig and the Polish ammunition store on the Westerplatte

. Both were ordered to defend up to 12 hours in case of local uprising, until an expected relief by the Polish army. The Polish Post office was held by 52 employees led by Konrad Guderski against the German Danzig police, Home Guard (Heimwehr) and SS

, which after 14 hours of battle set the building on fire with flamethrower

s. All but four postman who escaped either died in the battle or were executed by the Germans as partisans (only in 1995 did the German court at Lübeck

invalidate the 1939 ruling and rehabilitate the "postmen"). The Polish Military Transit Depot (Polska Wojskowa Składnica Tranzytowa) on the Westerplatte

repelled countless attacks by the Danzig Police, SS, the Kriegsmarine

and the Wehrmacht

. Finally, the Westerplatte crew surrendered on 7 September, having exhausted their supplies of food, water, ammunition and medicines, becoming one of the symbols of Polish resistance to the German invasion. The heaviest fighting in Pomerelia took place at the Hel peninsula

Polish Navy base, which held out as one of the last centres of Polish military resistance until October 3, 1939 (see Battle of Hel

).

(Polish Corridor

) and the Free City of Danzig

were annexed by Nazi-Germany on October 8, 1939, and fused into Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia

.

and Abwehr

.

In Pomerania German secret organisations were established with the aim of taking part in dismemberment of Poland and weapons were smuggled across the German border

After the war started, acts of sabotage occurred and Polish authorities interned 126 Germans in Pomeranian Voivodeship suspected of cooperating with Nazis and involved in anti-Polish activities, based on previously prepared lists, and shipped them away east from the potential front line.

Before the war, activists from German minority organisations in Poland helped to organize lists of Poles who later were to be arrested or executed in Operation Tannenberg

.

With the beginning of the Invasion of Poland

on 1 September 1939, Selbstschutz units engaged in hostility towards the Polish population and military, and performed sabotage operations helping the German attack on the Polish state.

Bernhard Chiari and Jerzy Kochanowski state estimates of an overall death toll ranging from 2,000 to 3,841 West Prussian ethnic Germans who lost their lives in the context of the invasion. In a report issued after the German historians' summit in 2000, death toll estimates were summarized at about 4,500 in West Prussia, including those killed in ethnic violence, those killed while serving in the Polish army, and those killed in other war-related events like German air raids. Historian Tomasz Chinciński gives a total of 3,257 deaths, 2000 of them being victims either of the normal wartime conditions (including civilians incidentally killed by advancing German army), or of participation in diversionary actions organized by Nazi sympathetics

. The most infamous supposed incident of violence involving suspected Nazi fifth columnists was Bloody Sunday in Bydgoszcz (Bromberg) , which was used excessively by Nazi propaganda

, which vastly inflated death tolls of up to 58,000. Since then these claims have been discredited.

By 5 October 1939, in West Prussia, Selbstschutz units made from German minority members under the command of Ludolf von Alvensleben

were 17,667 men strong, and had already executed 4,247 Poles, while Alvensleben complained to Selbstschutz officers that too few Poles had been shot. (German officers had reported that only a fraction of Poles had been "destroyed" in the region with the total number of those executed in West Prussia during this action being about 20,000. One Selbstschutz commander, Wilhelm Richardt, said in Karolewo (Karlhof) camp that he did not want to build big camps for Poles and feed them, and that it was an honour for Poles to fertilize the German soil with their corpses

About 80% of the German male adults of the Reichsgau were organized by the SS in Selbstschutz

units following the German conquest. Wehrmacht

, Selbstschutz

, Einsatzgruppen

of Sipo

and SD

, and Danzig NSDAP units were involved in a series of atrocities committed during and after the invasion, including murder

primarily of Polish intelligentsia

, Jews, and the extermination

of mentally and physically disabled, most notably at the massacres in Piaśnica forest

. This resulted in between 12,000 and 20,000 dead until October 25, and up to 60,000 dead in the first six month. The highest death toll was paid during the initial stage of the occupation. Estimates range from 36.000 to 42.000 killed.

Units were prepared before the war to sabotage Polish war efforts as well as organized mass executions of Poles. Executions aiming at the extermination of the Polish population started only hours after the invasion. During September 1939, Wehrmacht

took the main part in atrocities as well as Einsatzgruppen

of Sipo

and SD

(police and security service). From September 1939 to January 1940, atrocities were primarily committed by Selbstschutz

units.

During the September campaign, security police set up first concentration camps for Poles. Deportations to the General Government

and Stutthof

soon followed. Use of the Polish language was strictly forbidden, even in church, by the German Roman Catholic Bishop Carl Maria Splett

.

Provisional prisones were set up in Danzig (Gdańsk) and Pruszcz Gdański

. Prisoners were treated extremely brutally. Later Poles who were arrested were moved to Stutthof concentration camp

. In Gdynia

, based on lists prepared before the war, units of SS-Wachsturmbann Eimann, military units, Gestapo

, and police arrested thousands of people. They were transported to concentration camps in Gdynia-Grabówek, Redłów, Victoria Schule or Stutthof.

On the territories of counties: Tczewski, Starogardzki, Kartuski, Kościerski and Morski numerous arrests and executions took place. In the area of Szpęgawski Forest

many Jews were murdered.

The repressions in Bydgoszcz (Bromberg), the site of the Bloody Sunday (1939) events, were especially harsh. Bydgoszcz soon became a symbol of Nazi German terror. The "liquidation" action was carried out by Wehrmacht soldiers, operational groups and Selbstschutz. Mass arrests of Bydgoszcz citizens took place from 5 September 1939 until November 1939. Collective responsibility was applied and whole families murdered. On 10 September a special court was set up in Bydgoszcz which gave out 100 death sentences. The overall loss of Polish citizens in the first days of Bydgoszcz’s occupation is estimated at hundreds. Mass murder took place at sites near the town such as the "Valley of Death"

, Fordon

, Tryszczyn

and Borówno

. Others were in Koronów, Solec Kujawski

, Rybieniec, Karolowe, Radzim

, Mniszek

, and Grupa.

In October 1939, the Polish intelligentsia of Toruń

(Thorn) was imprisoned in "Fort VIII" under harsh conditions, before being executed in Barbarka forest (several hundreds), the local airport, and Przysiek.

Also in October 1939, 300 citizens of Grudziądz

(Graudenz) were murdered in Góry Księże and Mniszek

.

Germans especially targeted Polish intellectual and national elites, primarily priests, teachers, lawyers, doctors, officers, land owners, state officials, members of political and social organisations, as well as anyone that could hinder the German plan to enslave the Polish nation (see Operation Tannenberg

).

The first pogroms were made by Wehrmacht units and Sipo

Einsatzgruppen

. They arrested and executed political, social, and cultural activists as well as local government officials. Offices, institutions, and locations of Polish social and political organisations were penetrated. This action was codenamed Operation Tannenberg

. Goals were the liquidation of intellectual elites, and destruction of Polish culture

, institutions and organisations. Operational groups and Selbstschutz received orders to “politically cleanse the areas”. First arrests of Poles started after Wehrmacht arrived in Free City of Danzig

(Gdańsk) on 1 September 1939. With the help of units from SA, SS, and local police Polish officies and institutions were taken over. Polish State Railways

workers and custom officers were executed in Szymanków, Kałdów, or in their offices.

Concentration camps for Polish intelligentsia and Jews were set up in the second half of September 1939 in Karolew

and Radzim

, located in Sępolno powiat.

A high death toll was paid by the Polish clergy. It was a consequence of the old Prussian belief that the Catholic Church is the main pillar of Polish nation and patriotism. This belief was particularly expressed by Albert Forster

, Gauleiter

in Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia

. From 701 priests of the diocese

of Chełm (Kulm) on September 1, 1939, 322 were executed or died in concentration camps. 38 clergy from Starogard Gdański

(Preußisch Stargard) were executed in Szpęgawsko on October 20, 1939. The same day, lecturers and students from Pelpin seminary

were arrested by Gestapo

and afterwards executed. Similar incidents happened in most of Pomerelia

.

Piaśnica Wielka (Groß Piasnitz) was one of the first execution sites in occupied Poland. The executions took place between October 1939 and April 1940. Among others, intellectuals from Gdańsk (Danzig), Gdynia

(Gdingen), Wejherowo

(Neustadt in Westpreußen), and Kartuzy

(Karthaus) were murdered at this site. Additionally, about 2000 mental care clients from the "Altreich" were murdered there. Overall, an estimated 10.000 to 12.000 were killed.

Some Poles and Kashubians of Pomerelia organized an anti-Nazi guerrilla resistance group called "Pomeranian Griffin

" (TOW Gryf Pomorski). The main Polish resistance organization, Armia Krajowa

(Home Army), had a dedicated "Pomerania" district, itself was part of the larger "Western" district.

Roughly 60,000 German men from Pomerania died as soldiers in the Wehrmacht

and SS

until May, 1945.

Since 1943, the province became a target of allied air raids. The first attack was launched against Stettin on April 21, 1943, and left 400 dead. On August 17/18, the British RAF launched an attack on Peenemünde

, where Wernher von Braun

and his staff had developed and tested the world's first rocket

s. In October, Anklam

was a target. Throughout 1944 and early 1945, Stettin's industrial and residential areas were targets of air raids. Stralsund

was a target in October 1944.

Despite these raids, the province was regarded "safe" compared to other areas of the Third Reich, and thus became a shelter for evacuees primarily from hard hit Berlin

and the West German industrial centers.

After the war had turned back on Germany, the Pomeranian Wall

was renovated in the summer of 1944, and in the fall all men between sixteen and sixty years of age who had not yet been drafted were enrolled into Volkssturm

units.

The province of Pomerania became a battlefield on January 26, 1945, when in the pretext of the Red Army

's East Pomeranian Offensive

Soviet tanks entered the province near Schneidemühl, which surrendered on February 13.

On February 14, the remnants of German Army Group Vistula

On February 14, the remnants of German Army Group Vistula

("Heeresgruppe Weichsel") had managed to set up a frontline roughly at the province's southern frontier, and launched a counterattack (Operation Solstice

, "Sonnenwende") on February 15, that however stalled already on February 18. On February 24, the Second Belorussian Front launched the East Pomeranian Offensive

and despite heavy resistance primarily in the Rummelsburg

area took eastern Farther Pomerania

until March 10. On March 1, the First Belorussian Front had launched an offensive from the Stargard

and Märkisch Friedland area and succeeded in taking northwestern Farther Pomerania within five days. Cut off corps group Hans von Tettau

retreated to Dievenow

as a moving pocket

until March 11. Thus, German-held central Farther Pomerania was cut off, and taken after the Battle of Kolberg (March 4 to March 18).

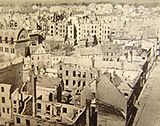

The fast advances of the Red Army during the East Pomeranian Offensive

The fast advances of the Red Army during the East Pomeranian Offensive

caught the civilian Farther Pomeranian population by surprise. The land route to the west was blocked since early March. Evacuation orders were issued not at all or much too late. The only way out of Farther Pomerania was via the ports of Stolpmünde, from which 18,300 were evacueted, Rügenwalde, from which 4,300 were evacuated, and Kolberg, which had been declared fortress and from which before the end of the Battle of Kolberg some 70,000 were evacuted. Those left behind became victims of murder, war rape

, and plunder. On March 6, the USAF bombed Swinemünde, where thousands of refugees were stranded, killing an estimated 25,000.

Many West Prussia

Many West Prussia

n Germans fled westward as the Red Army

advanced on the Eastern Front

. The Hela

peninsula and Hela town, northwest of Danzig, were defended by the German army until the end of the war on May, 9th, 1945. 900,000 people where evacuated by ship, mainly by the Kriegsmarine

. 200,000 could flee to the more western provinces of Germany on land (most before March, 1945). Only 3% of those who fled per ship died on the Baltic sea due to Soviet torpedoes. On land, due to the harsh winter and due to Soviet air raids, the losses among civilians were much higher.

The roving cauldron of Hans von Tettau

's corps was defended by some 10,000 to 16,000 troops, stemming primarily from the remnants of the "Holstein" and "Pommerland" Panzer Divisions, taking with them about 40,000 civilians. This group had managed to break through the Soviet encirclement north of Schivelbein and fought their way toward the coastline. Hoping for evacuation by the German navy, they secured a bridgehead near Hoff

and Horst

. As evacuation did not happen, they moved on to Dievenow, from where they were ferried to Wollin island on 11 and 12 March.

East of the Oder

river, Wehrmacht

's 3rd Panzer Army had set up the Altdamm bridgehead between Gollnow and Greifenhagen

. The Red Army

cleared the areas south of the bridgehead with the 47th Army

until 6 March, and the areas north of it with the 3rd Shock Army, reaching the coast on 9 March. On 15 March, Adolf Hitler

ordered some of the defending units to reinforce the 9th Army near Küstrin

, seriously weakening the Altdamm bridgehead. Hasso von Manteuffel

, in command since 10 March, was unable to further defend the bridgehead after 19 March, evacuated most of it on 20 March and had the Oder bridges blown up. The Red Army took the remaining pockets of the former bridgehead on 21 March. 40,000 German troops had been killed and 12,000 captured defending the bridgehead.

abandoned the last bridgehead on the Oder

rivers eastern bank, the Altdamm area. The frontline then ran along Dievenow

and lower Oder, and was held by the 3rd panzer army commanded by general Hasso von Manteuffel

. After another four days of fighting, the Red Army

managed to break through and cross the Oder between Stettin and Gartz (Oder), thus starting the northern theater of the Battle of Berlin on March 24. Stettin was abandoned the next day.

Throughout April, the Second Belorussian Front led by general Konstantin Rokossovsky

advanced through Western Pomerania. Demmin

and Greifswald

surrendered on April 30.

In Demmin, nearly 900 people committed mass suicides

in fear of the Red Army. Coroner lists show that most drowned in the nearby River Tollense

and River Peene

, where others poisoned themselves. This was fueled by atrocities - rapes, pillage and executions committed by Red Army soldiers until the city commander had the access to the rivers blocked on May 3.

In the first days of May, Wehrmacht

abandoned Usedom

and Wollin islands, and on May 5, the last German troops departed from Sassnitz

on the island of Rügen

. Two days later, Wehrmacht surrendered unconditionally to the Red Army.

Franz Schwede-Coburg propagated a turn of the war until the very end. Evacuation orders therefore were issued either too late or not at all. Schwede-Coburg even had the authorities repel flight attempts by the population.

) and West Prussia (Pomerelia) died during and shortly after the war due to air raids, but mainly afterwards due to Soviet Red Army atrocities committed in revenge against the German civilians.

The official post-war West German Schieder commission

estimated German civilian losses in all of the territories generally called "Pomerania" at:

History of Pomerania

The history of Pomerania dates back more than 10,000 years. Settlement in the area started by the end of the Vistula Glacial Stage, about 13,000 years ago. Archeological traces have been found of various cultures during the Stone and Bronze Age, of Veneti and Germanic peoples during the Iron Age...

before and during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

In 1933, the German Province of Pomerania like all of Germany came under control of the Nazi regime

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

. During the following years, the Nazis led by Gauleiter

Gauleiter

A Gauleiter was the party leader of a regional branch of the NSDAP or the head of a Gau or of a Reichsgau.-Creation and Early Usage:...

Franz Schwede-Coburg manifested their power through the process known as Gleichschaltung

Gleichschaltung

Gleichschaltung , meaning "coordination", "making the same", "bringing into line", is a Nazi term for the process by which the Nazi regime successively established a system of totalitarian control and tight coordination over all aspects of society. The historian Richard J...

and repression of their opponents.

At the same time, the Pomeranian Voivodeship

Pomeranian Voivodeship (1919-1939)

Pomeranian Voivodeship or Pomorskie Voivodeship was an administrative unit of inter-war Poland . It ceased to exist in September 1939, following German and Soviet aggression on Poland...

was part of the Second Polish Republic

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

, led by Józef Piłsudski. With respect to Polish Pomerania Nazi diplomacy as parts of its initial attempts to subordinate Poland into Anti-Comintern Pact aimed at incorporation of the Free City of Danzig

Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig was a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig and surrounding areas....

into the Third Reich and an extra-territorial transit route through Polish territory, which was rejected by the Polish government, that feared economic blackmail by Nazi Germany, and reduction to puppet status.

In 1939, the German Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

invaded Poland

Invasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

engaging in series of massacres against the civilian population, the most notable among them being the Mass murders in Piaśnica

Mass murders in Piaśnica

The mass murders in Piaśnica were a set of mass executions carried out by Germans, during World War II, between the fall of 1939 and spring of 1940 in Piasnica Wielka in the Darzlubska Wilderness near Wejherowo. Standard estimates put the number of victims at between twelve thousand and fourteen...

. Polish Pomerania was made part of Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia

Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia

The Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia was a Nazi German province created on 8 October 1939 from the territory of the annexed Free City of Danzig, the annexed Polish province Greater Pomeranian Voivodship , and the Nazi German Regierungsbezirk West Prussia of Gau East Prussia. Before 2 November 1939,...

. The German state set up concentration camps, performed expulsion of the Poles and Jews, and systematically engaged in genocide of people they regarded as Untermensch

Untermensch

Untermensch is a term that became infamous when the Nazi racial ideology used it to describe "inferior people", especially "the masses from the East," that is Jews, Gypsies, Poles along with other Slavic people like the Russians, Serbs, Belarussians and Ukrainians...

(primarily, Jews and ethnic Poles

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

).

In 1945, Pomerania

Pomerania

Pomerania is a historical region on the south shore of the Baltic Sea. Divided between Germany and Poland, it stretches roughly from the Recknitz River near Stralsund in the West, via the Oder River delta near Szczecin, to the mouth of the Vistula River near Gdańsk in the East...

was taken by the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

during the East Pomeranian Offensive

East Pomeranian Offensive

The East Pomeranian Strategic Offensive operation was an offensive by the Red Army in its fight against the German Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front...

and the Battle of Berlin

Battle of Berlin

The Battle of Berlin, designated the Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation by the Soviet Union, was the final major offensive of the European Theatre of World War II....

. Along with the Soviet offensive, atrocities against the German civilian population occurred on a large scale.

Pomeranian Voivodeship

The totalitarian and anti-Polish Nazi Party, led by Adolf HitlerAdolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

, took power in Germany in 1933. By this time, the Second Polish Republic

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

was led by Józef Piłsudski who ruled the country as an authoritarian democracy. Hitler at first ostentatiously pursued a policy of rapprochement

Rapprochement

In international relations, a rapprochement, which comes from the French word rapprocher , is a re-establishment of cordial relations, as between two countries...

with Poland, culminating in the ten year Polish-German Non-Aggression Pact of 1934. In the coming years, Germany placed an emphasis on rearmament, to which Poland and other European powers reacted. Initially Nazis were able to achieve their immediate goals of territorial expansion without provoking armed resistance; in 1938 Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

annexed Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

and the Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

after the Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

. In October 1938, Germany tried to get Poland to join the Anti-Comintern Pact

Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact was an Anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on November 25, 1936 and was directed against the Communist International ....

. Poland refused, as the alliance was quickly becoming a sphere of influence for an increasingly powerful Germany.

Following negotiations with Hitler for the Munich Agreement, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

reported that, "He told me privately, and last night he repeated publicly, that after this Sudeten German question is settled, that is the end of Germany's territorial claims in Europe". Almost immediately following the agreement, however, Hitler reneged. The Nazis increased their requests for the incorporation of the Free City of Danzig into the Reich, citing the "protection" of the German majority as a motive.

In November 1938, Danzig's district administrator, Albert Forster

Albert Forster

Albert Maria Forster was a Nazi German politician. Under his administration as the Gauleiter of Danzig-West Prussia during the Second World War, the local non-German population suffered ethnic cleansing, mass murder, and forceful Germanisation...

reported to the League of Nations that Hitler had told him Polish frontiers would be guaranteed if the Poles were "reasonable like the Czechs." German State Secretary Ernst von Weizsäcker

Ernst von Weizsäcker

Ernst Freiherr von Weizsäcker was a German diplomat and politician. He served as State Secretary at the Foreign Office from 1938 to 1943, and as German Ambassador to the Holy See from 1943 to 1945...

reaffirmed this alleged guarantee in December 1938.

The situation regarding the Free City and the Polish Corridor created a number of headaches for German and Polish Customs. The Germans requested the Free City of Danzig

Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig was a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig and surrounding areas....

and the construction of an extra-territorial highway (to complete the Reichsautobahn Berlin-Königsberg) and railway through the Polish Corridor, connecting East Prussia to Danzig and Germany proper. Poland agreed on building a German highway and to allow German railway traffic, in return they would extend the non-aggression pact for 25 years.

This seemed to conflict with Hitler's plans and with Poland's rejection of the Anti-Comintern Pact, his desire to either isolate or gain support against the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

. German newspapers in Danzig and Nazi Germany played an important role inciting nationalist sentiment; headlines buzzed about how Poland was misusing its economic rights in Danzig and German Danzigers were increasingly subjugated to the will of the Polish state. At the same time, Hitler also offered Poland additional territory as an enticement, such as the possible annexation of Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

, the Memel Territory, Soviet Ukraine

Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic or in short, the Ukrainian SSR was a sovereign Soviet Socialist state and one of the fifteen constituent republics of the Soviet Union lasting from its inception in 1922 to the breakup in 1991...

and Czech inhabited lands.

However, Polish leaders continued to fear for the loss of their independence and a shared fate with Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, although they had also taken part in its partitioning.

Some felt that the Danzig question was inextricably tied to the problems in the Polish Corridor and any settlement regarding Danzig would be one step towards the eventual loss of Poland's access to the sea.

Nevertheless, Hitler's credibility outside of Germany was very low after the occupation of Czechoslovakia.

Hitler used the issue of the status city as pretext for attacking Poland, while explaining during a high level meeting of German military officials in May 1939 that his real goal is obtaining Lebensraum

Lebensraum

was one of the major political ideas of Adolf Hitler, and an important component of Nazi ideology. It served as the motivation for the expansionist policies of Nazi Germany, aiming to provide extra space for the growth of the German population, for a Greater Germany...

for Germany, isolating Poles from their Allies in the West and afterwards attacking Poland, thus avoiding the repeat of Czech situation

In 1939, Nazi Germany made another proposal regarding Danzig; the city was to be incorporated into the Reich while the Polish section of the population was to be "evacuated" and resettled elsewhere. Poland was to retain a permanent right to use the seaport and the route through the Polish Corridor was to be constructed. However, the Poles distrusted Hitler and saw the plan as a threat to Polish sovereignty, practically subordinating Poland to the Axis and the Anti-Comintern Bloc while reducing the country to a state of near-servitude.

Additionally, Poland was backed by guarantees of support from both the United Kingdom and France in regard to Danzig.

A revised and less favorable proposal came in the form of an ultimatum

Ultimatum

An ultimatum is a demand whose fulfillment is requested in a specified period of time and which is backed up by a threat to be followed through in case of noncompliance. An ultimatum is generally the final demand in a series of requests...

made by the Nazis in late August, after the orders had already been given to attack Poland on September 1, 1939. Nevertheless, at midnight on August 29, Joachim von Ribbentrop

Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop was Foreign Minister of Germany from 1938 until 1945. He was later hanged for war crimes after the Nuremberg Trials.-Early life:...

handed British Ambassador Sir Neville Henderson a list of terms which would allegedly ensure peace in regard to Poland. Danzig was to be incorporated into Germany and there was to be a plebiscite in the Polish Corridor; all Poles who were born or settled there since 1919 would have no vote, while all Germans born but not living there would. An exchange of minority populations between the two countries was proposed. If Poland accepted these terms, Germany would agree to the British offer of an international guarantee, which would include the Soviet Union. A Polish plenipotentiary

Plenipotentiary

The word plenipotentiary has two meanings. As a noun, it refers to a person who has "full powers." In particular, the term commonly refers to a diplomat fully authorized to represent his government as a prerogative...

, with full powers, was to arrive in Berlin and accept these terms by noon the next day. The British Cabinet viewed the terms as "reasonable," except the demand for a Polish Plenipotentiary, which was seen as similar to Czechoslovak President Emil Hácha

Emil Hácha

Emil Hácha was a Czech lawyer, the third President of Czecho-Slovakia from 1938 to 1939. From March 1939, he presided under the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.-Judicial career:...

accepting Hitler’s terms in mid-March 1939.

When Ambassador Józef Lipski

Józef Lipski

Józef Lipski . Polish diplomat and Ambassador to Nazi Germany, 1934 to 1939. Lipski played a key role in foreign policy of Second Polish Republic.-Life:Lipski trained as a lawyer, and joined the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1925....

went to see Ribbentrop on August 30, he was presented with Hitler’s demands. However, he did not have the full power to sign and Ribbentrop ended the meeting. News was then broadcast that Poland had rejected Germany's offer.

Free City of Danzig

In May 1933, the Nazi Party won the local elections in the city. However, they received 57 percent of the vote, less than the two-thirds required by the League of NationsLeague of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

to change the Constitution of the Free City of Danzig. The government introduced anti-Semitic

Anti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

and anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism

Anti-Catholicism is a generic term for discrimination, hostility or prejudice directed against Catholicism, and especially against the Catholic Church, its clergy or its adherents...

laws, the latter primarily being directed against the newly brought in Poles and Kashubian

Kashubians

Kashubians/Kaszubians , also called Kashubs, Kashubes, Kaszubians, Kassubians or Cassubians, are a West Slavic ethnic group in Pomerelia, north-central Poland. Their settlement area is referred to as Kashubia ....

inhabitants. The city also served as a training point for members of the German minority within Poland that, recruited by organisations such as the Jungdeutsche Partei ("Young German Party") and the Deutsche Vereinigung ("German Union"), would form the leading cadres of Selbstschutz

Selbstschutz

Selbstschutz stands for two organisations:# A name used by a number of paramilitary organisations created by ethnic Germans in Central and Eastern Europe# A name for self-defence measures and units in ethnic German, Austrian, and Swiss civil defence....

, an organisation involved with murder and atrocities during the German invasion of Poland in 1939. As throughout Germany, Jews were increasingly persecuted; the Danzig Great Synagogue

Great Synagogue (Danzig)

The Great Synagogue , was a synagogue of the Jewish Community of Danzig in the city of Danzig, Germany . It was built in 1885-1887 on Reitbahnstraße, now Bogusławski Street...

was taken over and demolished by the local authorities in 1939.

Pomeranian Nazi movement before 1933

Throughout the existence of the Weimar RepublicWeimar Republic

The Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

, politics in the province was dominated by the nationalist conservative DNVP (German National People's Party). The Nazi party (NSDAP) did not have any significant success at elections, nor did it have a substantial amount of members. The Pomeranian Nazi party was founded by students of the University of Greifswald in 1922, when the NSDAP was officially forbidden. The university's rector Karl Theodor von Vahlen became Gauleiter

Gauleiter

A Gauleiter was the party leader of a regional branch of the NSDAP or the head of a Gau or of a Reichsgau.-Creation and Early Usage:...

(head of the provincial party) in 1924. Soon afterwards, he was fired by the university and went bankrupt. In 1924, the party had 330 members, and in December 1925, 297 members. The party was not present in all of the province. The members were concentrated mainly in Western Pomerania and internally divided. Vahlen retired from the Gauleiter position in 1927 and was replaced by Walther von Corswandt, a Pomeranian knight estate holder.

Corswandt led the party from his estate in Kuntzow. In the 1928 Reichstag

Reichstag (Weimar Republic)

The Reichstag was the parliament of Weimar Republic .German constitution commentators consider only the Reichstag and now the Bundestag the German parliament. Another organ deals with legislation too: in 1867-1918 the Bundesrat, in 1919–1933 the Reichsrat and from 1949 on the Bundesrat...

elections, the Nazis got 1,5% of the votes in Pomerania. Party property was partially pawned. In 1929, the party gained 4,1% of the votes. Corswandt was fired after conflicts with the party's leadership and replaced with Wilhelm von Karpenstein, one of the former students who formed the Pomeranian Nazi party in 1922 and since 1929 lawywer in Greifswald

Greifswald

Greifswald , officially, the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald is a town in northeastern Germany. It is situated in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, at an equal distance of about from Germany's two largest cities, Berlin and Hamburg. The town borders the Baltic Sea, and is crossed...

. He moved the headquarters to Stettin and replaced many of the party officials predominantly with young radicals. In the Reichstag elections of September 14, 1930, the party gained a significant 24,3% of the Pomeranian votes and thus became the second strongest party, the strongest still being the DNVP, which however was internally divided in the early 1930s.

In the elections of July 1932, the Nazis gained 48% of the Pomeranian votes, while the DNVP dropped to 15,8%. In March 1933, the NSDAP gained 56.3%.

Nazi government since 1933

Immediately after their gain of power, the Nazis began arresting their opponents. In March 1933, 200 people were arrested, this number rose to 600 during the following months. In Stettin-Bredow, at the site of the bankrupt Vulcan-Werft shipyards, the Nazis set up a short-lived "wild" concentration camp from October 1933 to March 1934, where SASturmabteilung

The Sturmabteilung functioned as a paramilitary organization of the National Socialist German Workers' Party . It played a key role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s...

maltreated their victims. The Pomeranian SA in 1933 had grown to 100,000 members.

Oberpräsident von Halfern retired in 1933, and with him one third of the Landrat and Oberbürgermeister (mayor) officials.

Also in 1933, an election was held for a new provincial parliament, which then had a Nazi majority. Decrees were issued that shifted all issues formerly in responsibility of the parliament to the "Provinzialausschuß" commission, and furthermore, shifted the power to decide on these issues from the "Provinzialausschuß" to the "Oberpräsident" official, although he had to hear the "Provinzialrat" commission before. Once the power was shifted to the Oberpräsident with the Provinzialrat as an advisor, all organs of the "Provinzialverband" ("Provinziallandtag" (parliament), "Provinzialausschuß and all other commissions), the former self-administration of the province, were dissolved except for the downgraded Provinzialrat, which assembled about once a year without making use of its advisory rights. The "Landeshauptmann" position, the Provinzialverband's head, was not abolished. From 1933, Landeshauptmann would be a Nazi who was acting in line with the Oberpräsident. The law entered into force on April 1, 1934.

In 1934, many of the heads of the Pomeranian Nazi-movement were exchanged. SA

Sturmabteilung

The Sturmabteilung functioned as a paramilitary organization of the National Socialist German Workers' Party . It played a key role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power in the 1920s and 1930s...

leader von Heydebreck was shot in Stadelheim

Stadelheim Prison

Stadelheim Prison, in Munich's Giesing district, is one of the largest prisons in Germany.Founded in 1894 it was the site of many executions, particularly by guillotine during the Nazi period.-Notable inmates:...

near Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

due to his friendship to Röhm

Ernst Röhm

Ernst Julius Röhm, was a German officer in the Bavarian Army and later an early Nazi leader. He was a co-founder of the Sturmabteilung , the Nazi Party militia, and later was its commander...

. Gauleiter

Gauleiter

A Gauleiter was the party leader of a regional branch of the NSDAP or the head of a Gau or of a Reichsgau.-Creation and Early Usage:...

von Karpenstein was arrested for two years and banned from Pomerania due to conflicts with the NSDAP headquarters. His substitute, Franz Schwede-Coburg, replaced most of Karpenstein's staff with Corswant's earlier staff, friends of him from Bavaria

Bavaria

Bavaria, formally the Free State of Bavaria is a state of Germany, located in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the largest state by area, forming almost 20% of the total land area of Germany...

, and SS. From the 27 Kreisleiter

Kreisleiter

Kreisleiter was a Nazi Party political rank and title which existed as a political rank between 1930 and 1945 and as a Nazi Party title from as early as 1928...

officials, 23 were forced out of office by Schwede-Coburg, who became Gauleiter on July 21, and Oberpräsident on July 28, 1934.

As in all of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

, the Nazis established totalitarian control

Totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a political system where the state recognizes no limits to its authority and strives to regulate every aspect of public and private life wherever feasible...

over the province by Gleichschaltung

Gleichschaltung

Gleichschaltung , meaning "coordination", "making the same", "bringing into line", is a Nazi term for the process by which the Nazi regime successively established a system of totalitarian control and tight coordination over all aspects of society. The historian Richard J...

.

German anti-Nazi resistance

Resistance is also reported from members of the nationalist conservative DNVP. The monarchist Herbert von Bismarck-Lasbeck was forced out of office in 1933. The conservative newspaper Pommersche Tagespost was banned in 1935 after printing an article of monarchist Hans-Joachim von Rohr. In 1936, four members of the DNVP were tried for founding a monarchist organization.

Other DNVP members, who had addressed their opposition already before 1933, were arrested multiple times after the Nazis had taken over. Ewald Kleist-Schmenzin, Karl Magnus von Knebel-Doberitz, and Karl von Zitzewitz were active resistants.

Pfarrernotbund

The Pfarrernotbund was an organisation founded on 11 September 1933 to unite German evangelical theologians, pastors and church office-holders against the introduction of the Aryan paragraph into the 28 Protestant regional church bodies and the Deutsche Evangelische Kirche and against the...

(150 members in late 1933) and Confessing Church

Confessing Church

The Confessing Church was a Protestant schismatic church in Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to nazify the German Protestant church.-Demographics:...

("Bekennende Kirche"), the successor organization, headed by Reinold von Thadden-Trieglaff. In March 1935, 55 priests were arrested. The Confessing Church maintained a preachers' seminar headed by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian and martyr. He was a participant in the German resistance movement against Nazism and a founding member of the Confessing Church. He was involved in plans by members of the Abwehr to assassinate Adolf Hitler...

in Zingst

Zingst

Zingst Peninsula is the easternmost portion of the three-part Fischland-Darß-Zingst Peninsula, located in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany between the cities Rostock and Stralsund on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea. The area is part of the Pomeranian coast...

, which moved to Finkenwalde in 1935 and to Köslin and Groß Schlönwitz in 1940. Within the Catholic Church, the most prominent resistance member was Greifswald

Greifswald

Greifswald , officially, the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald is a town in northeastern Germany. It is situated in the state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, at an equal distance of about from Germany's two largest cities, Berlin and Hamburg. The town borders the Baltic Sea, and is crossed...

priest Alfons Wachsmann, who was executed in 1944.

After the failed assassination attempt of Hitler on July 20, 1944, Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

arrested thirteen Pomeranian nobles and one burgher, all knight estate owners. Of those, Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin

Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin

Ewald von Kleist-Schmenzin was a lawyer, a conservative politician, resistance fighter in Nazi Germany and a member of the July 20 Plot.- Biography :...

had contacted Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

in 1938 to inform about the work of the German opposition to the Nazis, and was executed in April 1945. Karl von Zitzewitz had connections to the Kreisauer Kreis group. Among the other arrested were Malte von Veltheim Fürst zu Putbus, who died in a concentration camp, as well as Alexander von Kameke and Oscar Caminecci-Zettuhn, who both were executed.

Territorial changes in 1938

In 1938-39, the German as well as the Polish Pomeranian provinces were enlarged. Most of Grenzmark Posen-West Prussia and two counties of BrandenburgBrandenburg

Brandenburg is one of the sixteen federal-states of Germany. It lies in the east of the country and is one of the new federal states that were re-created in 1990 upon the reunification of the former West Germany and East Germany. The capital is Potsdam...

were made a district of the German Province of Pomerania. Several counties from Mazovia

Mazovia

Mazovia or Masovia is a geographical, historical and cultural region in east-central Poland. It is also a voivodeship in Poland.Its historic capital is Płock, which was the medieval residence of first Dukes of Masovia...

and Greater Poland

Greater Poland

Greater Poland or Great Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief city is Poznań.The boundaries of Greater Poland have varied somewhat throughout history...

were joined to the Polish Pomeranian Voivodship, and her capital was moved from Toruń to Bydgoszcz (Bromberg).

World War II (1939–1945)

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

over rights to Free City of Danzig

Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig was a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig and surrounding areas....

and land transit through the Polish Corridor

Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor , also known as Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia , which provided the Second Republic of Poland with access to the Baltic Sea, thus dividing the bulk of Germany from the province of East...

to the exclave of East Prussia

East Prussia

East Prussia is the main part of the region of Prussia along the southeastern Baltic Coast from the 13th century to the end of World War II in May 1945. From 1772–1829 and 1878–1945, the Province of East Prussia was part of the German state of Prussia. The capital city was Königsberg.East Prussia...

, served as Hitler's pretext for Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

's invasion of Poland

Invasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

, which commenced on September 1, 1939. The strategy

Strategy

Strategy, a word of military origin, refers to a plan of action designed to achieve a particular goal. In military usage strategy is distinct from tactics, which are concerned with the conduct of an engagement, while strategy is concerned with how different engagements are linked...

of the Nazi government was to temporarily divide Poland

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

with Stalin's

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, formalized in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

. In the longer perspective, the Nazis aimed to expand the German "Lebensraum

Lebensraum

was one of the major political ideas of Adolf Hitler, and an important component of Nazi ideology. It served as the motivation for the expansionist policies of Nazi Germany, aiming to provide extra space for the growth of the German population, for a Greater Germany...

" in the East, to exploit soil, oil, minerals and workforce from the lands of the Slavs, turning them into a race of slaves destined to serve the German 1000 Year Reich

Reich

Reich is a German word cognate with the English rich, but also used to designate an empire, realm, or nation. The qualitative connotation from the German is " sovereign state." It is the word traditionally used for a variety of sovereign entities, including Germany in many periods of its history...

and its master race

Master race

Master race was a phrase and concept originating in the slave-holding Southern US. The later phrase Herrenvolk , interpreted as 'master race', was a concept in Nazi ideology in which the Nordic peoples, one of the branches of what in the late-19th and early-20th century was called the Aryan race,...

. The fate of other peoples of these territories, notably Jews and Gypsies, was to be annihilation and deportation during the Holocaust

The Holocaust

The Holocaust , also known as the Shoah , was the genocide of approximately six million European Jews and millions of others during World War II, a programme of systematic state-sponsored murder by Nazi...

.

Deportation of the Pomeranian Jews

In 1933, about 7,800 Jews lived in the Province of Pomerania, of which a third lived in Stettin. The other two thirds were living all over the province, Jewish communities numbering more than 200 people were in Stettin, Kolberg, Lauenburg, and Stolp.When the Nazis started to terrorize Jews, many emigrated. Twenty weeks after the Nazis seized power, the number of Jewish Pomeranians had already dropped by eight percent.

Besides the repressions Jews had to endure in all Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

, including the destruction of the Pomeranian synagoges on November 9, 1938 (Reichskristallnacht), all male Stettin Jews were deported to Oranienburg concentration camp

Oranienburg concentration camp

Oranienburg concentration camp was one of the first detention facilities established by the Nazis when they gained power in 1933. It held the Nazis' political opponents from the Berlin region, mostly members of the Communist Party of Germany and social-democrats, as well as a number of homosexual...

after this event and kept there for several weeks.

On February 12 and 13, 1940, the remaining 1,000 to 1,300 Pomeranian Jews, regardless of sex, age and health, were deported from Stettin and Schneidemühl to the Lublin-Lipowa Reservation, that had been set up following the Nisko Plan

Nisko Plan

The Nisko Plan, also Lublin Plan or Nisko-Lublin Plan , was developed in September 1939 by the Nazi German Schutzstaffel as a "territorial solution to the Jewish Question"...

in occupied Poland. Among the deported were intermarried non-Jewish women. The deportation was carried out in an inhumane manner. Despite low temperatures, the carriages were not heated. No food had been allowed to be taken along. The property left behind was liquidated. Up to 300 people perished from the deportation itself. In the Lublin area under Kurt Engel's regime, the people were subject to inhumane treatment, starvation and murder. Only a few survived the war.

Regarding the Jewish community from the Schneidemühl area, JewishGen

JewishGen

JewishGen is a non-profit organization founded in 1987 as a resource for Jewish genealogy. In 2003, JewishGen became an affiliate of the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust in New York.It provides amateur and professional genealogists with the tools to research their...

with reference to research by Peter Simonstein Cullman says that the widespread belief of the Schneidemühl Jews being deported along with the Stettin Jews is contradicted by the respective files in the Bundesarchiv and USHMM archives. While there were indeed such orders and Jews from the Schneidemühl area were rounded up after 15 February, an intervention of the Association of Jews in Germany (Reichsvereinigung)

Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland

The Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland was an administrative branch subject to the Reich's government, represented by its Reichssicherheitshauptamt...

resulted in a change of the Nazi plans on 21 February: instead of deportation to the Generalgouvernement like the Stettin Jews, these people were to be deported to places within the Altreich. Deportations to transit and death camps followed.

Invasion and occupation of the Polish Corridor and Danzig

Military campaign

The invasion of PolandInvasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

by the Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

on September 1, 1939, which marked the beginning of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...