List of book burning incidents

Encyclopedia

Chinese philosophy books (by Emperor Qin Shi Huang and anti-Qin rebels)

Following the advice of minister Li SiLi Si

Li Si was the influential Prime Minister of the feudal state and later of the dynasty of Qin, between 246 BC and 208 BC. A famous Legalist, he was also a notable calligrapher. Li Si served under two rulers: Qin Shi Huang, king of Qin and later First Emperor of China—and his son, Qin Er Shi...

, Emperor Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang , personal name Ying Zheng , was king of the Chinese State of Qin from 246 BC to 221 BC during the Warring States Period. He became the first emperor of a unified China in 221 BC...

ordered the burning of all philosophy books and history books from states other than Qin

Qin (state)

The State of Qin was a Chinese feudal state that existed during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Periods of Chinese history...

— beginning in 213 BCE. This was followed by the live burial of a large number of intellectuals who did not comply with the state dogma.

Li Si is reported to have said: "I, your servant, propose that all historian's records other than those of Qin's

Qin Dynasty

The Qin Dynasty was the first imperial dynasty of China, lasting from 221 to 207 BC. The Qin state derived its name from its heartland of Qin, in modern-day Shaanxi. The strength of the Qin state was greatly increased by the legalist reforms of Shang Yang in the 4th century BC, during the Warring...

be burned. With the exception of the academics whose duty includes possessing books, if anyone under heaven

All under heaven

Tianxia is a phrase in the Chinese language and an ancient Chinese cultural concept that denoted either the entire geographical world or the metaphysical realm of mortals, and later became associated with political sovereignty.In ancient China, tianxia denoted the lands, space, and area divinely...

has copies of the Shi Jing

Shi Jing

The Classic of Poetry , translated variously as the Book of Songs, the Book of Odes, and often known simply as its original name The Odes, is the earliest existing collection of Chinese poems and songs. It comprises 305 poems and songs, with many range from the 10th to the 7th centuries BC...

, the Classic of History

Classic of History

The Classic of History is a compilation of documentary records related to events in ancient history of China. It is also commonly known as the Shàngshū , or simply Shū...

, or the writings of the hundred schools of philosophy, they shall deliver them [the books] to the governor or the commandant for burning. Anyone who dares to discuss the Shi Jing or the Classic of History shall be publicly executed. Anyone who uses history to criticize the present shall have his family executed. Any official who sees the violations but fails to report them is equally guilty. Anyone who has failed to burn the books after thirty days of this announcement shall be subjected to tattoo

Tattoo

A tattoo is made by inserting indelible ink into the dermis layer of the skin to change the pigment. Tattoos on humans are a type of body modification, and tattoos on other animals are most commonly used for identification purposes...

ing and be sent to build the Great Wall. The books that have exemption are those on medicine

Medicine

Medicine is the science and art of healing. It encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness....

, divination

Divination

Divination is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic standardized process or ritual...

, agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

and forestry

Forestry

Forestry is the interdisciplinary profession embracing the science, art, and craft of creating, managing, using, and conserving forests and associated resources in a sustainable manner to meet desired goals, needs, and values for human benefit. Forestry is practiced in plantations and natural stands...

. Those who have interest in law

Law

Law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior, wherever possible. It shapes politics, economics and society in numerous ways and serves as a social mediator of relations between people. Contract law regulates everything from buying a bus...

s shall instead study from officials."

The damage to Chinese culture was compounded during the revolts which ended the short rule of Qin Er Shi

Qin Er Shi

Qin Er Shi , literally Second Emperor of Qin Dynasty, personal name Huhai, was emperor of the Qin Dynasty in China from 210 BC until 207 BC.-Name:...

, Qin Shi Huang's son. The imperial palace and state archives were burned, destroying many of the remaining written records that had been spared by the father.

Several other large book burnings also occurred in Chinese history. It appears they occurred in every dynasty following the Qin, but it is unknown how often.

Protagoras's "On the Gods" (by Athenian authorities)

The Classical Greek philosopher ProtagorasProtagoras

Protagoras was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher and is numbered as one of the sophists by Plato. In his dialogue Protagoras, Plato credits him with having invented the role of the professional sophist or teacher of virtue...

was a proponent of agnosticism

Agnosticism

Agnosticism is the view that the truth value of certain claims—especially claims about the existence or non-existence of any deity, but also other religious and metaphysical claims—is unknown or unknowable....

, writing in a now lost work entitled On the Gods: "Concerning the gods, I have no means of knowing whether they exist or not or of what sort they may be, because of the obscurity of the subject, and the brevity of human life.

According to Diogenes Laertius

Diogenes Laertius

Diogenes Laertius was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Nothing is known about his life, but his surviving Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers is one of the principal surviving sources for the history of Greek philosophy.-Life:Nothing is definitively known about his life...

, the above outspoken Agnostic position taken by Protagoras aroused anger, causing the Athenians to expel him from their city, where the authorities ordered all copies of the book to be collected and burned in the marketplace. The same story is also mentioned by Cicero

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero , was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.He introduced the Romans to the chief...

. However, the Classicist John Burnet

John Burnet (classicist)

John Burnet was a Scottish classicist.-Education, Life and Work:Burnet was educated at the Royal High School, Edinburgh, the University of Edinburgh, and Balliol College, Oxford, receiving his M.A. degree in 1887...

doubts this account, as both Diogenes Laertius and Cicero wrote hundreds of years later and no such persecution of Protagoras is mentioned by contemporaries who make extensive references to this philosopher. Burnet notes that even if some copies of Protagoras' book were burned, enough of them survived to be known and discussed in the following century.

Zoroastrian Scriptures (by Alexander the Great)

The BundahishnBundahishn

Bundahishn, meaning "Primal Creation", is the name traditionally given to an encyclopædiaic collections of Zoroastrian cosmogony and cosmology written in Book Pahlavi. The original name of the work is not known....

- an encyclopædiaic collection of Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is a religion and philosophy based on the teachings of prophet Zoroaster and was formerly among the world's largest religions. It was probably founded some time before the 6th century BCE in Greater Iran.In Zoroastrianism, the Creator Ahura Mazda is all good, and no evil...

cosmogony

Cosmogony

Cosmogony, or cosmogeny, is any scientific theory concerning the coming into existence or origin of the universe, or about how reality came to be. The word comes from the Greek κοσμογονία , from κόσμος "cosmos, the world", and the root of γίνομαι / γέγονα "to be born, come about"...

and cosmology

Cosmology

Cosmology is the discipline that deals with the nature of the Universe as a whole. Cosmologists seek to understand the origin, evolution, structure, and ultimate fate of the Universe at large, as well as the natural laws that keep it in order...

- refers to "Aleskandar" (Alexander the Great) as having burned the Avesta

Avesta

The Avesta is the primary collection of sacred texts of Zoroastrianism, composed in the Avestan language.-Early transmission:The texts of the Avesta — which are all in the Avestan language — were composed over the course of several hundred years. The most important portion, the Gathas,...

(Zoroastrian Scriptures), following his defeat of "Dara" (Darius III). For this act of sacrilage, Alexander's name was regularly accompanied in Zoroastrian texts by the appelation Gojastak or Gojaste (The Damned). No such act by Alexander is recorded in Greek and Latin accounts of his life - these, however, tend to depict Alexander in a favorable light.

Jewish Holy Books (by the Seleucid monarch Antiochus IV)

In 168 BCE the Seleucid monarch Antiochus IV ordered Jewish 'Books of the Law' found in Jerusalem to be 'rent in pieces' and burned - part of the series of persecutions which precipitated the revolt of the MaccabeesMaccabees

The Maccabees were a Jewish rebel army who took control of Judea, which had been a client state of the Seleucid Empire. They founded the Hasmonean dynasty, which ruled from 164 BCE to 63 BCE, reasserting the Jewish religion, expanding the boundaries of the Land of Israel and reducing the influence...

.

Aeneid (unsuccessfully ordered by Virgil)

In 17 BCE, VirgilVirgil

Publius Vergilius Maro, usually called Virgil or Vergil in English , was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He is known for three major works of Latin literature, the Eclogues , the Georgics, and the epic Aeneid...

died and in his will ordered that his masterpiece, the Aeneid

Aeneid

The Aeneid is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Romans. It is composed of roughly 10,000 lines in dactylic hexameter...

, be burned, as it was a draft and not a final version. However, his friends disobeyed him and released the epic poem after editing it themselves.

Roman history book (by the aediles)

In 25 CE Senator Aulus Cremutius CordusAulus Cremutius Cordus

Aulus Cremutius Cordus was a Roman historian. There are very few remaining fragments of his work, that covered the civil war and the reign of Augustus Caesar. In 25 AD he was forced by Sejanus who was praetorian prefect under Tiberius to take his life after being accused of maiestas...

was forced to commit suicide and his History was burned by the aedile

Aedile

Aedile was an office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public order. There were two pairs of aediles. Two aediles were from the ranks of plebeians and the other...

s, under the order of the senate

Roman Senate

The Senate of the Roman Republic was a political institution in the ancient Roman Republic, however, it was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors. After a magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic...

. The book's praise of Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus , often referred to as Brutus, was a politician of the late Roman Republic. After being adopted by his uncle he used the name Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, but eventually returned to using his original name...

and Cassius

Gaius Cassius Longinus

Gaius Cassius Longinus was a Roman senator, a leading instigator of the plot to kill Julius Caesar, and the brother in-law of Marcus Junius Brutus.-Early life:...

, who had assassinated Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

, was considered an offence under the lex majestatis

Law of majestas

The Law of Majestas, or lex maiestas, refers to any one of several ancient Roman laws throughout the republican and Imperial periods dealing with crimes against the Roman people, state, or Emperor....

. A copy of the book was saved by Cordus' daughter Marcia, and it was published again under Caligula

Caligula

Caligula , also known as Gaius, was Roman Emperor from 37 AD to 41 AD. Caligula was a member of the house of rulers conventionally known as the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Caligula's father Germanicus, the nephew and adopted son of Emperor Tiberius, was a very successful general and one of Rome's most...

. However, only a few fragments survived to the present.

Torah scroll (by Roman soldier)

Flavius Josephus relates that about the year 5050

Year 50 was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Vetus and Nerullinus...

a Roman soldier seized a Torah scroll and, with abusive and mocking language, burned it in public. This incident almost brought on a general Jewish revolt against Roman rule, such as broke out two decades later. However, the Roman Procurator

Procurator (Roman)

A procurator was the title of various officials of the Roman Empire, posts mostly filled by equites . A procurator Augusti was the governor of the smaller imperial provinces...

Cumanus appeased the Jewish populace by beheading the culprit.

Sorcery scrolls (by early converts to Christianity at Ephesus)

According to the New TestamentNew Testament

The New Testament is the second major division of the Christian biblical canon, the first such division being the much longer Old Testament....

book of Acts

Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles , usually referred to simply as Acts, is the fifth book of the New Testament; Acts outlines the history of the Apostolic Age...

, early converts to Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

in Ephesus

Ephesus

Ephesus was an ancient Greek city, and later a major Roman city, on the west coast of Asia Minor, near present-day Selçuk, Izmir Province, Turkey. It was one of the twelve cities of the Ionian League during the Classical Greek era...

who had previously practiced sorcery burned their scrolls: "A number who had practised sorcery brought their scrolls together and burned them publicly. When they calculated the value of the scrolls, the total came to fifty thousand drachmas." (Acts 19:19, NIV

New International Version

The New International Version is an English translation of the Christian Bible. Published by Zondervan in the United States and by Hodder & Stoughton in the UK, it has become one of the most popular modern translations in history.-History:...

)

Rabbi Haninah ben Teradion burned with a Torah scroll (under Hadrian)

Under the Emperor HadrianHadrian

Hadrian , was Roman Emperor from 117 to 138. He is best known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the northern limit of Roman Britain. In Rome, he re-built the Pantheon and constructed the Temple of Venus and Roma. In addition to being emperor, Hadrian was a humanist and was philhellene in...

, the teaching of the Jewish Scriptures was forbidden, as in the wake of the Bar Kochva Rebellion the Roman authorities regarded such teaching as seditious and tending towards revolt. Haninah ben Teradion

Haninah ben Teradion

Rabbi Haninah ben Teradion or Hananiah ben Teradion was a teacher in the third Tannaitic generation . He was a contemporary of Eleazar ben Perata I and of Halafta, together with whom he established certain ritualistic rules...

, one of the Jewish Ten Martyrs

Ten Martyrs

The Ten Martyrs refers to a group of ten rabbis living during the era of the Mishnah who were martyred by the Romans in the period after the destruction of the second Temple...

executed for having defied that ban, is reported to have been burned at the stake

Burned at the Stake

Burned at the Stake is a 1981 film directed by Bert I. Gordon. It stars Susan Swift and Albert Salmi.-Cast:*Susan Swift as Loreen Graham / Ann Putnam*Albert Salmi as Captaiin Billingham*Guy Stockwell as Dr. Grossinger*Tisha Sterling as Karen Graham...

together with the forbidden Torah

Torah

Torah- A scroll containing the first five books of the BibleThe Torah , is name given by Jews to the first five books of the bible—Genesis , Exodus , Leviticus , Numbers and Deuteronomy Torah- A scroll containing the first five books of the BibleThe Torah , is name given by Jews to the first five...

scroll which he had been teaching. According to Jewish tradition, when the flame started to burn himself and the scroll he still managed to say to his pupils: "I see the scrolls burning but the letters fly up in the air" - a saying considered to symbolize the superiority of ideas to brute force. While in the original applying to sacred writings only, 20th Century Israeli writers also quoted this saying in the context of non-religious ideals.

In the same period a Torah scroll was also burned ceremoniously on Jerusalem's Temple Mount

Temple Mount

The Temple Mount, known in Hebrew as , and in Arabic as the Haram Ash-Sharif , is one of the most important religious sites in the Old City of Jerusalem. It has been used as a religious site for thousands of years...

, in this case without a human being added.

Burning of the Torah by Apostomus (precise time and circumstances debated)

Among five catastrophes said to have overtaken the Jews on the Seventeenth of TammuzSeventeenth of Tammuz

The Seventeenth of Tammuz is a minor Jewish fast day commemorating the breach of the walls of Jerusalem before the destruction of the Second Temple. It falls on the 17th day of the Hebrew month of Tammuz and marks the beginning of the three-week mourning period leading up to Tisha B'Av.The day...

, the Mishnah

Mishnah

The Mishnah or Mishna is the first major written redaction of the Jewish oral traditions called the "Oral Torah". It is also the first major work of Rabbinic Judaism. It was redacted c...

includes "the burning of the Torah

Torah

Torah- A scroll containing the first five books of the BibleThe Torah , is name given by Jews to the first five books of the bible—Genesis , Exodus , Leviticus , Numbers and Deuteronomy Torah- A scroll containing the first five books of the BibleThe Torah , is name given by Jews to the first five...

by Apostomus

Apostomus

-The Talmudic account:Among five catastrophes said to have overtaken the Jews on the Seventeenth of Tammuz, the Mishnah includes "the burning of the Torah by Apostomus"....

". Since no further details are given and there are no other references to Apostomus in Jewish or non-Jewish sources, the exact time and circumstances of this traumatic event are debated, historians assigning to it different dates in Jewish history under Seleucid or Roman rule, and it might be identical with one of the events noted above (see Apostomus

Apostomus

-The Talmudic account:Among five catastrophes said to have overtaken the Jews on the Seventeenth of Tammuz, the Mishnah includes "the burning of the Torah by Apostomus"....

page).

Epicurus's book (in Paphlagonia)

The book Established beliefs of EpicurusEpicurus

Epicurus was an ancient Greek philosopher and the founder of the school of philosophy called Epicureanism.Only a few fragments and letters remain of Epicurus's 300 written works...

was burned in a Paphlagonia

Paphlagonia

Paphlagonia was an ancient area on the Black Sea coast of north central Anatolia, situated between Bithynia to the west and Pontus to the east, and separated from Phrygia by a prolongation to the east of the Bithynian Olympus...

n marketplace by order of the charlatan Alexander, supposed prophet of Ascapius ca 160

Christian books (by Diocletian)

A decree of emperor DiocletianDiocletian

Diocletian |latinized]] upon his accession to Diocletian . c. 22 December 244 – 3 December 311), was a Roman Emperor from 284 to 305....

in 303, calling for an increased persecution of Christians

Persecution of Christians

Persecution of Christians as a consequence of professing their faith can be traced both historically and in the current era. Early Christians were persecuted for their faith, at the hands of both Jews from whose religion Christianity arose, and the Roman Empire which controlled much of the land...

, included the burning of Christian

Christian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

books. At that time, the governor of Valencia

Valencia (city in Spain)

Valencia or València is the capital and most populous city of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third largest city in Spain, with a population of 809,267 in 2010. It is the 15th-most populous municipality in the European Union...

offered the deacon

Deacon

Deacon is a ministry in the Christian Church that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions...

who would become known as Saint Vincent of Saragossa to have his life spared in exchange for his consigning Scripture to the fire. Vincent refused and let himself be executed instead. In religious paintings he is often depicted holding the book whose preservation he preferred to his own life (see illustration in Saint Vincent of Saragossa page.)

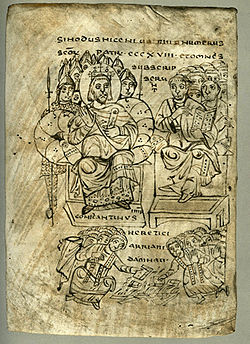

Books of Arianism (after Council of Nicaea)

Arianism

Arianism is the theological teaching attributed to Arius , a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt, concerning the relationship of the entities of the Trinity and the precise nature of the Son of God as being a subordinate entity to God the Father...

and his followers, after the first Council of Nicaea

First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea was a council of Christian bishops convened in Nicaea in Bithynia by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325...

(325 B.C.E.), were burned for heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

. Arius

Arius

Arius was a Christian presbyter in Alexandria, Egypt of Libyan origins. His teachings about the nature of the Godhead, which emphasized the Father's divinity over the Son , and his opposition to the Athanasian or Trinitarian Christology, made him a controversial figure in the First Council of...

was exiled and presumably assassinated following this, and Arian books continued to be regularly burned into the 330s.

Library of Antioch (by Jovian)

In 364, the Christian Emperor Jovian ordered the entire Library of AntiochAntioch

Antioch on the Orontes was an ancient city on the eastern side of the Orontes River. It is near the modern city of Antakya, Turkey.Founded near the end of the 4th century BC by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander the Great's generals, Antioch eventually rivaled Alexandria as the chief city of the...

to be burnt. It had been heavily stocked by the aid of his non-Christian predecessor, Emperor Julian.

"Unnaceptable writings" (by Athanasius)

Elaine PagelsElaine Pagels

Elaine Pagels, née Hiesey , is the Harrington Spear Paine Professor of Religion at Princeton University. The recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, she is best known for her studies and writing on the Gnostic Gospels...

claims that in 367, Athanasius ordered monks in the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria in his role as bishop

Bishop

A bishop is an ordained or consecrated member of the Christian clergy who is generally entrusted with a position of authority and oversight. Within the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox Churches, in the Assyrian Church of the East, in the Independent Catholic Churches, and in the...

of Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

to destroy all "unacceptable writings" in Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, the list of writings to be saved constituting the New Testament

New Testament

The New Testament is the second major division of the Christian biblical canon, the first such division being the much longer Old Testament....

.

The Sibylline Books (various times)

The Sibylline BooksSibylline Books

The Sibylline Books or Libri Sibyllini were a collection of oracular utterances, set out in Greek hexameters, purchased from a sibyl by the last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus, and consulted at momentous crises through the history of the Republic and the Empire...

were a collection of oracular sayings. According to myth, the Cumae

Cumae

Cumae is an ancient Greek settlement lying to the northwest of Naples in the Italian region of Campania. Cumae was the first Greek colony on the mainland of Italy , and the seat of the Cumaean Sibyl...

an sibyl

Sibyl

The word Sibyl comes from the Greek word σίβυλλα sibylla, meaning prophetess. The earliest oracular seeresses known as the sibyls of antiquity, "who admittedly are known only through legend" prophesied at certain holy sites, under the divine influence of a deity, originally— at Delphi and...

offered Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus was the legendary seventh and final King of Rome, reigning from 535 BC until the popular uprising in 509 BC that led to the establishment of the Roman Republic. He is more commonly known by his cognomen Tarquinius Superbus and was a member of the so-called Etruscan...

the books for a high price, and when he refused, burned three. When he refused to buy the remaining six at the same price, she again burned three, finally forcing him to buy the last three at the original price. The quindecimviri sacris faciundis watched over the surviving books in the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, but could not prevent their being burned when the temple burned down in 83 BCE. They were replaced by a similar collection of oracular sayings from around the Mediterranean in 76 BCE, along with the sayings of the Tiburtine sibyl

Tiburtine Sibyl

The Tiburtine Sibyl was a Roman sibyl, whose seat was the ancient Etruscan town of Tibur .The mythic meeting of Cæsar Augustus with the Sibyl, of whom he inquired whether he should be worshiped as a god, was a favored motif of Christian artists. Whether the sibyl in question was the Etruscan Sibyl...

, and then checked by priests for perceived accuracy as compared to the burned originals. These remained until for political reasons they were burned by Flavius Stilicho

Stilicho

Flavius Stilicho was a high-ranking general , Patrician and Consul of the Western Roman Empire, notably of Vandal birth. Despised by the Roman population for his Germanic ancestry and Arian beliefs, Stilicho was in 408 executed along with his wife and son...

(died 408).

Writings of Priscillian

In 385, the theologian PriscillianPriscillian

Priscillian was bishop of Ávila and a theologian from Roman Gallaecia , the first person in the history of Christianity to be executed for heresy . He founded an ascetic group that, in spite of persecution, continued to subsist in Hispania and Gaul until the later 6th century...

of Ávila became the first Christian to be executed by fellow-Christians as a heretic

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

. Some (though not all) of his writings were condemned as heretical and burned. For many centuries they were considered irreversibly lost, but surviving copies were discovered in the 19th century.

Archives of Ctesiphon (during Arab conquest)

The Sassanid EmpireSassanid Empire

The Sassanid Empire , known to its inhabitants as Ērānshahr and Ērān in Middle Persian and resulting in the New Persian terms Iranshahr and Iran , was the last pre-Islamic Persian Empire, ruled by the Sasanian Dynasty from 224 to 651...

's capital Ctesiphon

Ctesiphon

Ctesiphon, the imperial capital of the Parthian Arsacids and of the Persian Sassanids, was one of the great cities of ancient Mesopotamia.The ruins of the city are located on the east bank of the Tigris, across the river from the Hellenistic city of Seleucia...

was conquered by Arab armies

Islamic conquest of Persia

The Muslim conquest of Persia led to the end of the Sassanid Empire in 644, the fall of Sassanid dynasty in 651 and the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Persia...

under the military command of Sa'ad ibn Abi Waqqas in 637, during the caliphate of Umar

Umar

`Umar ibn al-Khattāb c. 2 November , was a leading companion and adviser to the Islamic prophet Muhammad who later became the second Muslim Caliph after Muhammad's death....

. Though the general population was not harmed, the palaces were burned, leading to destruction of archives recording centuries of Sassenid history.

Repeated destruction of Alexandria libraries

The library of the SerapeumSerapeum

A serapeum is a temple or other religious institution dedicated to the syncretic Hellenistic-Egyptian god Serapis, who combined aspects of Osiris and Apis in a humanized form that was accepted by the Ptolemaic Greeks of Alexandria...

in Alexandria was trashed, burned and looted, 392, at the decree of Theophilus of Alexandria

Theophilus of Alexandria

Theophilus of Alexandria was Patriarch of Alexandria, Egypt, from 385 to 412. He is regarded as a saint by the Coptic Orthodox Church....

, who was ordered so by Theodosius I

Theodosius I

Theodosius I , also known as Theodosius the Great, was Roman Emperor from 379 to 395. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule over both the eastern and the western halves of the Roman Empire. During his reign, the Goths secured control of Illyricum after the Gothic War, establishing their homeland...

. Around the same time, Hypatia was murdered. One of the largest destructions of books occurred at the Library of Alexandria

Library of Alexandria

The Royal Library of Alexandria, or Ancient Library of Alexandria, in Alexandria, Egypt, was the largest and most significant great library of the ancient world. It flourished under the patronage of the Ptolemaic dynasty and functioned as a major center of scholarship from its construction in the...

, traditionally held to be in 640; however, the precise years are unknown as are whether the fires were intentional or accidental.

Etrusca Disciplina

Etrusca Disciplina, the EtruscanEtruscan civilization

Etruscan civilization is the modern English name given to a civilization of ancient Italy in the area corresponding roughly to Tuscany. The ancient Romans called its creators the Tusci or Etrusci...

books of cult and divination, were collected and burned in the 5th century.

Nestorius' books (by Theodosius II)

The books of NestoriusNestorius

Nestorius was Archbishop of Constantinople from 10 April 428 to 22 June 431.Drawing on his studies at the School of Antioch, his teachings, which included a rejection of the long-used title of Theotokos for the Virgin Mary, brought him into conflict with other prominent churchmen of the time,...

, declared to be heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

, were burned under an edict of Theodosius II

Theodosius II

Theodosius II , commonly surnamed Theodosius the Younger, or Theodosius the Calligrapher, was Byzantine Emperor from 408 to 450. He is mostly known for promulgating the Theodosian law code, and for the construction of the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople...

(435). The Greek originals of most writings were irrevocably destroyed, surviving mainly in Syriac translations.

Qur'anic texts with varying wording (ordered by the 3rd Caliph, Uthman)

Uthman ibn 'AffanUthman

Uthman ibn Affan was one of the companions of Islamic prophet, Muhammad. He played a major role in early Islamic history as the third Sunni Rashidun or Rightly Guided Caliph....

, the third Caliph

Caliph

The Caliph is the head of state in a Caliphate, and the title for the ruler of the Islamic Ummah, an Islamic community ruled by the Shari'ah. It is a transcribed version of the Arabic word which means "successor" or "representative"...

of Islam after Muhammad

Muhammad

Muhammad |ligature]] at U+FDF4 ;Arabic pronunciation varies regionally; the first vowel ranges from ~~; the second and the last vowel: ~~~. There are dialects which have no stress. In Egypt, it is pronounced not in religious contexts...

, who is credited with overseeing the collection of the verses of the Qur'an

Qur'an

The Quran , also transliterated Qur'an, Koran, Alcoran, Qur’ān, Coran, Kuran, and al-Qur’ān, is the central religious text of Islam, which Muslims consider the verbatim word of God . It is regarded widely as the finest piece of literature in the Arabic language...

, ordered the destruction of any other remaining text containing verses of the Quran after the Quran has been fully collected, circa 650. This was done to ensure that the collected and authenticated Quranic copy that Uthman collected became the primary source for others to follow, thereby ensuring that Uthman's version of the Quran remained authentic. Although the Qur'an had mainly been propagated through oral transmission, it also had already been recorded in at least three codices

Codex

A codex is a book in the format used for modern books, with multiple quires or gatherings typically bound together and given a cover.Developed by the Romans from wooden writing tablets, its gradual replacement...

, most importantly the codex of Abdullah ibn Mas'ud in Kufa

Kufa

Kufa is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000....

, and the codex of Ubayy ibn Ka'b in Syria

Syria

Syria , officially the Syrian Arab Republic , is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest....

. Sometime between 650 and 656, a committee appointed by Uthman is believed to have produced a singular version in seven copies, and Uthman is said to have "sent to every Muslim province one copy of what they had copied, and ordered any other Qur'anic materials, whether written in fragmentary manuscripts or whole copies, be burnt."

Competing prayer books (at Toledo)

After the conquest of Toledo, SpainToledo, Spain

Toledo's Alcázar became renowned in the 19th and 20th centuries as a military academy. At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 its garrison was famously besieged by Republican forces.-Economy:...

(1085) by the king of Castile, it was being disputed on whether Iberian Christians should follow the foreign Roman rite

Roman Rite

The Roman Rite is the liturgical rite used in the Diocese of Rome in the Catholic Church. It is by far the most widespread of the Latin liturgical rites used within the Western or Latin autonomous particular Church, the particular Church that itself is also called the Latin Rite, and that is one of...

or the traditional Mozarabic rite

Mozarabic Rite

The Mozarabic, Visigothic, or Hispanic Rite is a form of Catholic worship within the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church, and in the Spanish Reformed Episcopal Church . Its beginning dates to the 7th century, and is localized in the Iberian Peninsula...

. After other ordeal

Ordeal

Ordeal may refer to* The American title of What Happened to the Corbetts, a 1939 novel by Nevil Shute* Trial by ordeal, the judicial practice...

s, it was submitted to the trial by fire

Trial by ordeal

Trial by ordeal is a judicial practice by which the guilt or innocence of the accused is determined by subjecting them to an unpleasant, usually dangerous experience...

: One book for each rite was thrown into a fire. The Toledan book was little damaged after the Roman one was consumed. Henry Jenner

Henry Jenner

Henry Jenner FSA was a British scholar of the Celtic languages, a Cornish cultural activist, and the chief originator of the Cornish language revival....

comments in the Catholic Encyclopedia

Catholic Encyclopedia

The Catholic Encyclopedia, also referred to as the Old Catholic Encyclopedia and the Original Catholic Encyclopedia, is an English-language encyclopedia published in the United States. The first volume appeared in March 1907 and the last three volumes appeared in 1912, followed by a master index...

: "No one who has seen a Mozarabic manuscript with its extraordinarily solid vellum

Vellum

Vellum is mammal skin prepared for writing or printing on, to produce single pages, scrolls, codices or books. It is generally smooth and durable, although there are great variations depending on preparation, the quality of the skin and the type of animal used...

, will adopt any hypothesis of Divine Interposition here."

Abelard forced to burn his own book (at Soissons)

The provincial synodSynod

A synod historically is a council of a church, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. In modern usage, the word often refers to the governing body of a particular church, whether its members are meeting or not...

held at Soissons

Soissons

Soissons is a commune in the Aisne department in Picardy in northern France, located on the Aisne River, about northeast of Paris. It is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital of the Suessiones...

(in France) in 1121 condemned the teachings of the famous theologian

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

Peter Abelard

Peter Abelard

Peter Abelard was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, theologian and preeminent logician. The story of his affair with and love for Héloïse has become legendary...

as heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

; he was forced to burn his own book before being shut up inside the convent

Convent

A convent is either a community of priests, religious brothers, religious sisters, or nuns, or the building used by the community, particularly in the Roman Catholic Church and in the Anglican Communion...

of St. Medard at Soissons.

The writings of Arnold of Brescia (at France and Rome)

The rebellious monk Arnold of BresciaArnold of Brescia

Arnold of Brescia , also known as Arnaldus , was an Italian monk from Lombardy who called on the Church to renounce ownership of property and participated in the failed Commune of Rome. Eventually arrested, he was hanged by the Church, burned posthumously, and then had his ashes thrown into the...

- Abelard's pupil and colleague - refused to abjure his views after they were condemned at the Synod of Sens in 1141, and went on to lead the Commune of Rome

Commune of Rome

The Commune of Rome was an attempt to establish a government like the old Roman Republic in opposition to the temporal power of the higher nobles and the popes beginning in 1144...

in direct opposition to the Pope, until being executed in 1155.

The Church ordered the burning of all his writings, which was carried out so thoroughly than none of them survives and it is unknown even what they were - except for what can be inferred from polemics against him. Nevertheless, though no written word of Arnold's has survived, his teachings on apostolic poverty

Apostolic poverty

Apostolic poverty is a doctrine professed in the thirteenth century by the newly formed religious orders, known as the mendicant orders, in direct response to calls for reform in the Roman Catholic Church...

continued potent after his death, among "Arnoldists" and more widely among Waldensians

Waldensians

Waldensians, Waldenses or Vaudois are names for a Christian movement of the later Middle Ages, descendants of which still exist in various regions, primarily in North-Western Italy. There is considerable uncertainty about the earlier history of the Waldenses because of a lack of extant source...

and the Spiritual Franciscans.

Nalanda University

The library of NalandaNalanda

Nālandā is the name of an ancient center of higher learning in Bihar, India.The site of Nalanda is located in the Indian state of Bihar, about 55 miles south east of Patna, and was a Buddhist center of learning from the fifth or sixth century CE to 1197 CE. It has been called "one of the...

, known as Dharma Gunj (Mountain of Truth) or Dharmagañja (Treasury of Truth), was the most renowned repository of Buddhist and Hindu knowledge in the world at the time. Its collection was said to comprise hundreds of thousands of volumes, so extensive that it burned for months when set aflame by Muslim invaders in 1193.

Samanid Dynasty Library

The Royal Library of the Samanid Dynasty was burned at the turn of the 11th century during the Turkic invasion from the east. AvicennaAvicenna

Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā , commonly known as Ibn Sīnā or by his Latinized name Avicenna, was a Persian polymath, who wrote almost 450 treatises on a wide range of subjects, of which around 240 have survived...

was said to have tried to save the precious manuscripts from the fire as the flames engulfed the collection.

Buddhist writings (in the MaldivesMaldivesThe Maldives , , officially Republic of Maldives , also referred to as the Maldive Islands, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean formed by a double chain of twenty-six atolls oriented north-south off India's Lakshadweep islands, between Minicoy Island and...

)

Following the conversion of the MaldivesMaldives

The Maldives , , officially Republic of Maldives , also referred to as the Maldive Islands, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean formed by a double chain of twenty-six atolls oriented north-south off India's Lakshadweep islands, between Minicoy Island and...

to Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

in 1153 (or by some accounts in 1193), the Buddhist religion - hitherto state religion for more than a thousand years - was suppressed. The copper-plate document known as Dhanbidhū Lōmāfānu

Lomafanu

Lōmāfānu or Loamaafaanu, also known by the Sanskrit name Sasanam, are Maldivian texts in the form of copper plates on which inscriptions have been added. The oldest of these plates dates from the twelfth century AD....

gives information about events the southern Haddhunmathi Atoll

Haddhunmathi Atoll

Haddhunmathi or Haddummati Atoll is an administrative division of the Maldives. It corresponds to the natural atoll of the same name.It is mostly rimmed by barrier reefs, the broadest of which are topped by islands...

, which had been a major center of Buddhism, where monks were beheaded, and statues of Vairocana

Vairocana

Vairocana is a celestial Buddha who is often interpreted as the Bliss Body of the historical Gautama Buddha; he can also be referred to as the dharmakaya Buddha and the great solar Buddha. In Sino-Japanese Buddhism, Vairocana is also seen as the embodiment of the Buddhist concept of shunyata or...

, the transcendent Buddha

Buddhahood

In Buddhism, buddhahood is the state of perfect enlightenment attained by a buddha .In Buddhism, the term buddha usually refers to one who has become enlightened...

, were destroyed. At that time, also the wealth of Buddhist manuscripts written on screwpine leaves by Maldivian monks in their Buddhist monasteries was either burnt or otherwise so thoroughly eliminated that it has disappeared without leaving any trace.

Destruction of Cathar texts (Languedoc region of France)

Cathar

Catharism was a name given to a Christian religious sect with dualistic and gnostic elements that appeared in the Languedoc region of France and other parts of Europe in the 11th century and flourished in the 12th and 13th centuries...

s of Languedoc

Languedoc

Languedoc is a former province of France, now continued in the modern-day régions of Languedoc-Roussillon and Midi-Pyrénées in the south of France, and whose capital city was Toulouse, now in Midi-Pyrénées. It had an area of approximately 42,700 km² .-Geographical Extent:The traditional...

(smaller numbers also lived elsewhere in Europe), culminating in the Albigensian Crusade

Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade or Cathar Crusade was a 20-year military campaign initiated by the Catholic Church to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc...

. Nearly every Cathar text that could be found was destroyed, in an effort to completely extirpate their heretical beliefs; only a few are known to have survived.

Maimonides' philosophy (at Montpellier)

MaimonidesMaimonides

Moses ben-Maimon, called Maimonides and also known as Mūsā ibn Maymūn in Arabic, or Rambam , was a preeminent medieval Jewish philosopher and one of the greatest Torah scholars and physicians of the Middle Ages...

' major philosophical and theological work, "Guide for the Perplexed

Guide for the Perplexed

The Guide for the Perplexed is one of the major works of Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, better known as Maimonides or "the Rambam"...

", got highly mixed reactions from fellow-Jews of his and later times - some revering it and viewing it as a triumph, while others deemed many of its ideas heretical

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

, banning it and on some occasions burning copies of it.

One such burning took place at Montpellier

Montpellier

-Neighbourhoods:Since 2001, Montpellier has been divided into seven official neighbourhoods, themselves divided into sub-neighbourhoods. Each of them possesses a neighbourhood council....

, Southern France, in 1233.

The Talmud (at Paris), first of many such burnings over the next centuries

In 1242, The French crown burned all TalmudTalmud

The Talmud is a central text of mainstream Judaism. It takes the form of a record of rabbinic discussions pertaining to Jewish law, ethics, philosophy, customs and history....

copies in Paris, about 12,000, after the book was "charged" and "found guilty" in the Paris trial sometimes called "the Paris debate". This burnings of Hebrew books were initiated by Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX, born Ugolino di Conti, was pope from March 19, 1227 to August 22, 1241.The successor of Pope Honorius III , he fully inherited the traditions of Pope Gregory VII and of his uncle Pope Innocent III , and zealously continued their policy of Papal supremacy.-Early life:Ugolino was...

, who persuaded French King Louis IX

Louis IX of France

Louis IX , commonly Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 until his death. He was also styled Louis II, Count of Artois from 1226 to 1237. Born at Poissy, near Paris, he was an eighth-generation descendant of Hugh Capet, and thus a member of the House of Capet, and the son of Louis VIII and...

to undertake it. This particular book burning was commemorated by the German Rabbi and poet Meir of Rothenburg

Meir of Rothenburg

Meir of Rothenburg was a German Rabbi and poet, a major author of the tosafot on Rashi's commentary on the Talmud...

in the elegy (kinna)

Kinnot

Kinnot are dirges or elegies traditionally recited by Jews on Tisha B'Av to mourn the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem and other tragedies in Jewish history, including the Crusades and the Holocaust...

called "Ask, O you who are burned in fire" (שאלי שרופה באש), which is recited to this day by Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews, also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim , are the Jews descended from the medieval Jewish communities along the Rhine in Germany from Alsace in the south to the Rhineland in the north. Ashkenaz is the medieval Hebrew name for this region and thus for Germany...

on the fast of Tisha B'av

Tisha B'Av

|Av]],") is an annual fast day in Judaism, named for the ninth day of the month of Av in the Hebrew calendar. The fast commemorates the destruction of both the First Temple and Second Temple in Jerusalem, which occurred about 655 years apart, but on the same Hebrew calendar date...

.

Since the Church and Christian states viewed the Talmud as a book hateful and insulting toward Christ and gentiles, subsequent popes were also known to organize public burnings of Jewish books. The most well known of them were Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV , born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was pope from June 25, 1243 until his death in 1254.-Early life:...

(1243–1254), Clement IV

Pope Clement IV

Pope Clement IV , born Gui Faucoi called in later life le Gros , was elected Pope February 5, 1265, in a conclave held at Perugia that took four months, while cardinals argued over whether to call in Charles of Anjou, the youngest brother of Louis IX of France...

(1256–1268), John XXII

Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII , born Jacques Duèze , was pope from 1316 to 1334. He was the second Pope of the Avignon Papacy , elected by a conclave in Lyon assembled by Philip V of France...

(1316–1334), Paul IV

Pope Paul IV

Pope Paul IV, C.R. , né Giovanni Pietro Carafa, was Pope from 23 May 1555 until his death.-Early life:Giovanni Pietro Carafa was born in Capriglia Irpina, near Avellino, into a prominent noble family of Naples...

(1555–1559), Pius V

Pope Pius V

Pope Saint Pius V , born Antonio Ghislieri , was Pope from 1566 to 1572 and is a saint of the Catholic Church. He is chiefly notable for his role in the Council of Trent, the Counter-Reformation, and the standardization of the Roman liturgy within the Latin Church...

(1566–1572) and Clement VIII

Pope Clement VIII

Pope Clement VIII , born Ippolito Aldobrandini, was Pope from 30 January 1592 to 3 March 1605.-Cardinal:...

(1592–1605).

Once the printing press was invented, the Church found it impossible to destroy entire printed editions of the Talmud and other sacred books. Johann Gutenberg, the German who invented the printing press around 1450, certainly helped stamp out the effectiveness of further book burnings. The tolerant (for its time) policies of Venice made it a center for the printing of Jewish books (as of books in general), yet the Talmud was publicly burned in 1553 and there was a lesser known burning of Hebrew book in 1568.

The House of Wisdom library (at Baghdad)

The House of WisdomHouse of Wisdom

The House of Wisdom was a library and translation institute established in Abbassid-era Baghdad, Iraq. It was a key institution in the Translation Movement and considered to have been a major intellectual centre during the Islamic Golden Age...

was destroyed during the Mongol invasion of Baghdad

Battle of Baghdad (1258)

The Siege of Baghdad, which occurred in 1258, was an invasion, siege and sacking of the city of Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate at the time and the modern-day capital of Iraq, by the Ilkhanate Mongol forces along with other allied troops under Hulagu Khan.The invasion left Baghdad in...

in 1258, along with all other libraries in Baghdad

Baghdad

Baghdad is the capital of Iraq, as well as the coterminous Baghdad Governorate. The population of Baghdad in 2011 is approximately 7,216,040...

. It was said that the waters of the Tigris

Tigris

The Tigris River is the eastern member of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of southeastern Turkey through Iraq.-Geography:...

ran black for six months with ink from the enormous quantities of books flung into the river.

Wycliffe's books (at Prague)

In 1410 John WycliffeJohn Wycliffe

John Wycliffe was an English Scholastic philosopher, theologian, lay preacher, translator, reformer and university teacher who was known as an early dissident in the Roman Catholic Church during the 14th century. His followers were known as Lollards, a somewhat rebellious movement, which preached...

's books were burnt by the illiterate Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

archbishop Zbyněk Zajíc z Házmburka

Zbynek Zajíc

Zbyněk Zajíc of Hasenburg was a Czech nobleman, and an important representative of the Roman Catholic Church...

in the court of his palace in Lesser Town of Prague

Malá Strana

Malá Strana is a district of the city of Prague, Czech Republic, and one of its most historic regions.The name translated into English literally means "Little Side", though it is frequently referred to as "Lesser Town", "Lesser Quarter", or "Lesser Side"...

to hinder the spread of Jan Hus

Jan Hus

Jan Hus , often referred to in English as John Hus or John Huss, was a Czech priest, philosopher, reformer, and master at Charles University in Prague...

's teaching.

Codices of the peoples conquered by the Aztecs (by Itzcoatl)

According to the Madrid CodexFlorentine Codex

The Florentine Codex is the common name given to a 16th century ethnographic research project in Mesoamerica by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Bernardino originally titled it: La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva Espana...

, the fourth tlatoani

Tlatoani

Tlatoani is the Nahuatl term for the ruler of an altepetl, a pre-Hispanic state. The word literally means "speaker", but may be translated into English as "king". A is a female ruler, or queen regnant....

Itzcoatl

Itzcóatl

Itzcoatl was the fourth emperor of the Aztecs, ruling from 1427 to 1440, the period when the Mexica threw off the domination of the Tepanecs and laid the foundations for the eventual Aztec Empire.- Biography :...

(ruling from 1427 (or 1428) to 1440) ordered the burning of all historical codices

Codex

A codex is a book in the format used for modern books, with multiple quires or gatherings typically bound together and given a cover.Developed by the Romans from wooden writing tablets, its gradual replacement...

because it was "not wise that all the people should know the paintings". Among other purposes, this allowed the Aztec state to develop a state-sanctioned history and mythos that venerated the Aztec god Huitzilopochtli

Huitzilopochtli

In Aztec mythology, Huitzilopochtli, also spelled Uitzilopochtli , was a god of war, a sun god, and the patron of the city of Tenochtitlan. He was also the national god of the Mexicas of Tenochtitlan.- Genealogy :...

.

Non-Catholic books (by Torquemada)

In the 1480s Tomas Torquemada promoted the burning of non-Catholic literature, especially the Jewish Talmud and also Arabic books after the final defeat of the Moors at GranadaGranada

Granada is a city and the capital of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence of three rivers, the Beiro, the Darro and the Genil. It sits at an elevation of 738 metres above sea...

in 1492.

Decameron, Ovid and other "lewd" books (by Savonarola)

In 1497, followers of the Italian priest Girolamo SavonarolaGirolamo Savonarola

Girolamo Savonarola was an Italian Dominican friar, Scholastic, and an influential contributor to the politics of Florence from 1494 until his execution in 1498. He was known for his book burning, destruction of what he considered immoral art, and what he thought the Renaissance—which began in his...

collected and publicly burned books and objects which were deemed to be "immoral", some - but by no means all - of which might fit modern criteria of pornography

Pornography

Pornography or porn is the explicit portrayal of sexual subject matter for the purposes of sexual arousal and erotic satisfaction.Pornography may use any of a variety of media, ranging from books, magazines, postcards, photos, sculpture, drawing, painting, animation, sound recording, film, video,...

or "lewd pictures", as well as pagan books, gaming tables, cosmetics, copies of Boccaccio's

Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio was an Italian author and poet, a friend, student, and correspondent of Petrarch, an important Renaissance humanist and the author of a number of notable works including the Decameron, On Famous Women, and his poetry in the Italian vernacular...

Decameron, and all the works of Ovid

Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso , known as Ovid in the English-speaking world, was a Roman poet who is best known as the author of the three major collections of erotic poetry: Heroides, Amores, and Ars Amatoria...

which could be found in Florence

Florence

Florence is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany and of the province of Florence. It is the most populous city in Tuscany, with approximately 370,000 inhabitants, expanding to over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area....

.

Arabic and Hebrew books (at Andalucia)

In 1490 a number of Hebrew Bibles and other Jewish books were burned at the behest of the Spanish Inquisition. In 1499 about 5000 Arabic manuscripts were consumed by flames in the public square at Granada on the orders of Ximénez de Cisneros, Archbishop of Toledo. Many of the poetic works were allegedly destroyed on account of their symbolized homoeroticismHomoeroticism

Homoeroticism refers to the erotic attraction between members of the same sex, either male–male or female–female , most especially as it is depicted or manifested in the visual arts and literature. It can also be found in performative forms; from theatre to the theatricality of uniformed movements...

. The German Romantic poet Heinrich Heine

Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine was one of the most significant German poets of the 19th century. He was also a journalist, essayist, and literary critic. He is best known outside Germany for his early lyric poetry, which was set to music in the form of Lieder by composers such as Robert Schumann...

wrote about this, stating "Dort, wo man Bücher verbrennt, verbrennt man am Ende auch Menschen" (Where they burn books, they will also, in the end, burn humans

Auto Da Fe

Auto Da Fe were an Irish new wave musical group formed in Holland in 1980 by former Steeleye Span singer Gay Woods and Trevor Knight. The band's sound incorporated keyboards and electronics. Woods stated "It was the happiest musical time I ever had so far. I learned so much. I was ridding myself...

), a quote written on the monument for the Nazi Book Burnings today.

Tyndale's New Testament (in England)

In October 1526 William TyndaleWilliam Tyndale

William Tyndale was an English scholar and translator who became a leading figure in Protestant reformism towards the end of his life. He was influenced by the work of Desiderius Erasmus, who made the Greek New Testament available in Europe, and by Martin Luther...

's English translation of the New Testament

New Testament

The New Testament is the second major division of the Christian biblical canon, the first such division being the much longer Old Testament....

was burned in London by Cuthbert Tunstal, Bishop of London.

Angelo Carletti's theological works (by Martin Luther)

Angelo Carletti di ChivassoAngelo Carletti di Chivasso

Blessed Angelo Carletti di Chivasso was a noted moral theologian of the Order of Friars Minor; born at Chivasso in Piedmont, in 1411; and died at Coni, in Piedmont, in 1495....

's work on Scotist theology, widely taken up in the Catholic Church, so infuriated Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

that the Protestant founder had it publicly burned.

Servetus's writings (burned with their author at Geneva, and also burned at Vienne)

In 1553, Servetus was burned as a heretic at the order of the city council of Geneva, dominated by CalvinJohn Calvin

John Calvin was an influential French theologian and pastor during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology later called Calvinism. Originally trained as a humanist lawyer, he broke from the Roman Catholic Church around 1530...

- because a remark in his translation of Ptolemy

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy , was a Roman citizen of Egypt who wrote in Greek. He was a mathematician, astronomer, geographer, astrologer, and poet of a single epigram in the Greek Anthology. He lived in Egypt under Roman rule, and is believed to have been born in the town of Ptolemais Hermiou in the...

's Geographia was considered an intolerable heresy. As he was placed on the stake, "around [Servetus'] waist were tied a large bundle of manuscript and a thick octavo

Octavo

Octavo to is a technical term describing the format of a book.Octavo may also refer to:* Octavo is a grimoire in the Discworld series by Terry Pratchett...

printed book", his Christianismi Restitutio. In the same year the Catholic

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

authorities at Vienne

Vienne

Vienne is the northernmost département of the Poitou-Charentes region of France, named after the river Vienne.- Viennese history :Vienne is one of the original 83 departments, established on March 4, 1790 during the French Revolution. It was created from parts of the former provinces of Poitou,...

also burned Servetus in effigy together with whatever of his writings fell into their hands, in token of the fact that Catholics and Protestants - mutually hostile in this time - were united in regarding Servetus as a heretic and seeking to extirpate his works. At the time it was considered that they succeeded, but three copies were later found to have survived, from which all later editions were printed.

"The Historie of Italie" (In England)

"The Historie of Italie" (1549), a scholarly and in itself not particularly controversial book by William ThomasWilliam Thomas (scholar)

William Thomas , probably a Welshman, was an Italian scholar and clerk of the council to Edward VI, who was executed for treason after the death of Edward.-Early years:...

, was in 1554 suppressed and publicly burnt by order of Queen Mary I of England

Mary I of England

Mary I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from July 1553 until her death.She was the only surviving child born of the ill-fated marriage of Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon. Her younger half-brother, Edward VI, succeeded Henry in 1547...

- after its author was executed on charges of treason. Enough copies survived for new editions to be published in 1561 and 1562, after Elizabeth I came to power.

Maya sacred books (by Spanish Bishop of Yucatan)

July 12, 1562, Fray Diego de LandaDiego de Landa

Diego de Landa Calderón was a Spanish Bishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Yucatán. He left future generations with a mixed legacy in his writings, which contain much valuable information on pre-Columbian Maya civilization, and his actions which destroyed much of that civilization's...

, acting Bishop of Yucatan - then recently conquered by the Spanish - threw into the fires the sacred books of the Maya

Maya civilization

The Maya is a Mesoamerican civilization, noted for the only known fully developed written language of the pre-Columbian Americas, as well as for its art, architecture, and mathematical and astronomical systems. Initially established during the Pre-Classic period The Maya is a Mesoamerican...

. The number of destroyed books is greatly disputed.

De Landa himself admitted to 27, other sources claim "99 times as many" - the later being disputed as an exaggeration motivated by anti-Spanish feeling, the so-called Black Legend

Black Legend

The Black Legend refers to a style of historical writing that demonizes Spain and in particular the Spanish Empire in a politically motivated attempt to morally disqualify Spain and its people, and to incite animosity against Spanish rule...

. Only three Maya codices

Maya codices

Maya codices are folding books stemming from the pre-Columbian Maya civilization, written in Maya hieroglyphic script on Mesoamerican bark cloth, made from the inner bark of certain trees, the main being the wild fig tree or Amate . Paper, generally known by the Nahuatl word amatl, was named by...

and a fragment of a fourth survive. Approximately 5,000 Maya cult image

Cult image

In the practice of religion, a cult image is a human-made object that is venerated for the deity, spirit or daemon that it embodies or represents...

s were also burned at the same time. The burning of books and images alike were part of de Landa's effort to eradicate the Maya "idol worship

Idolatry

Idolatry is a pejorative term for the worship of an idol, a physical object such as a cult image, as a god, or practices believed to verge on worship, such as giving undue honour and regard to created forms other than God. In all the Abrahamic religions idolatry is strongly forbidden, although...

", which he considered "diabolical". As narrated by de Landa himself, he had gained access to the sacred books, transcribed on deerskin, by previously gaining the natives' trust and showing a considerable interest in their culture and language: "We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they (the Maya) regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction." De Landa was later recalled to Spain and accused of having acted illegally in Yucatan, though eventually found not guilty of these charges. Present-day apologists for de Landa assert that, while he had destroyed the Maya books, his own Relación de las cosas de Yucatán

Relacíon de las cosas de Yucatán

Relación de las cosas de Yucatán was written by Diego de Landa Calderón circa 1566 shortly after his return to Spain after serving as Bishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Yucatán in the sixteenth century...

is a major source for the Mayan language and culture. Allen Wells calls his work an “ethnographic masterpiece”, while William J. Folan, Laraine A. Fletcher and Ellen R. Kintz have written that Landa‘s account of Maya social organization and towns before conquest is a “gem.”

"Obscene" Maltese poetry (by the Inquisition)

In 1584 Pasquale Vassallo, a MalteseMaltese people

The Maltese are an ethnic group indigenous to the Southern European nation of Malta, and identified with the Maltese language. Malta is an island in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea...

Dominican friar

Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

, wrote a collection of songs, of the kind known as "canczuni", in Italian

Italian language

Italian is a Romance language spoken mainly in Europe: Italy, Switzerland, San Marino, Vatican City, by minorities in Malta, Monaco, Croatia, Slovenia, France, Libya, Eritrea, and Somalia, and by immigrant communities in the Americas and Australia...

and Maltese

Maltese language

Maltese is the national language of Malta, and a co-official language of the country alongside English,while also serving as an official language of the European Union, the only Semitic language so distinguished. Maltese is descended from Siculo-Arabic...

. The poems fell into the hands of other Dominican friars who denounced him for writing "obscene literature". At the order of the Inquisition

Inquisition

The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy...

in 1585 the poems were burned for this allegedly 'obscene' content.

Bernardino de Sahagún's manuscripts on Aztec culture (by Spanish authorities)

The 12-volume work known as the Florentine CodexFlorentine Codex

The Florentine Codex is the common name given to a 16th century ethnographic research project in Mesoamerica by Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún. Bernardino originally titled it: La Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva Espana...

, result of a decades-long meticulous research conducted by the Fransciscan Bernardino de Sahagún

Bernardino de Sahagún

Bernardino de Sahagún was a Franciscan friar, missionary priest and pioneering ethnographer who participated in the Catholic evangelization of colonial New Spain . Born in Sahagún, Spain, in 1499, he journeyed to New Spain in 1529, and spent more than 50 years conducting interviews regarding Aztec...

in Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

, is among the most important sources on Aztec

Aztec

The Aztec people were certain ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, a period referred to as the late post-classic period in Mesoamerican chronology.Aztec is the...

culture and society as they were before the Spanish conquest, and on the Nahuatl

Nahuatl

Nahuatl is thought to mean "a good, clear sound" This language name has several spellings, among them náhuatl , Naoatl, Nauatl, Nahuatl, Nawatl. In a back formation from the name of the language, the ethnic group of Nahuatl speakers are called Nahua...

language. However, upon Sahagún's return to Europe in 1585, his original manuscripts - including the records of conversations and interviews with indigenous sources in Tlatelolco

Tlatelolco (altepetl)

Tlatelolco was a pre-Columbian Nahua altepetl in the Valley of Mexico. Its inhabitants were known as Tlatelolca. The Tlatelolca were a part of the Mexica ethnic group, a Nahuatl speaking people who arrived in what is now central Mexico in the 13th century...

, Texcoco, and Tenochtitlan, and likely to have included much primary material which did not get into the final codex - were confiscated by the Spanish authorities, disappeared irrevocably, and are assumed to have been destroyed. The Florentine Codex itself was for centuries afterwards only known in heavily-censored versions.

Luther's Bible translation

Martin LutherMartin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

's German translation of the Bible

Luther Bible

The Luther Bible is a German Bible translation by Martin Luther, first printed with both testaments in 1534. This translation became a force in shaping the Modern High German language. The project absorbed Luther's later years. The new translation was very widely disseminated thanks to the printing...

was burned in Catholic-dominated parts of Germany in 1624, by order of the Pope - part of the exacerbation of Catholic-Protestant relations due to the Thirty Years' War

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most countries in Europe. It was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history....

, then in its early stages.

Uriel da Costa's book (By Jewish community and city authorities in Amsterdam)

The 1624 book An Examination of the Traditions of the Pharisees, written by the dissident Jewish intellectual Uriel da CostaUriel da Costa

Uriel da Costa or Uriel Acosta was a philosopher and skeptic from Portugal.-Life:Costa was born in Porto with the name Gabriel da Costa...

, was burned in public by joint action of the Amsterdam Jewish Community and the city's Protestant-dominated City Council. The book, which questioned the fundamental idea of the immortality of the soul, was considered heretical from the Jewish and the Christian points of view alike.

Marco Antonio de Dominis' writings (in Rome)

The theologian and scientist Marco Antonio de DominisMarco Antonio de Dominis

Marco Antonio Dominis was a Dalmatian ecclesiastic, apostate, and man of science.-Early life:He was born on the island of Rab, Croatia, off the coast of Dalmatia...

came in 1624 into conflict with the Inquisition

Inquisition

The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy...

in Rome

Rome

Rome is the capital of Italy and the country's largest and most populated city and comune, with over 2.7 million residents in . The city is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, on the Tiber River within the Lazio region of Italy.Rome's history spans two and a half...

and was declared "a relapsed heretic

Heresy