History of Poland

Encyclopedia

The History of Poland

is rooted in the arrival of the Slavs

, who gave rise to permanent settlement and historic development on Polish lands. During the Piast dynasty

Christianity

was adopted

in 966 and medieval monarchy

established. The Jagiellon dynasty

period brought close ties with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

, cultural development

and territorial expansion, culminating in the establishment of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569.

The Commonwealth in its early phase constituted a continuation of the Jagiellon prosperity. From the mid-17th century, the huge state entered a period of decline caused by devastating wars and deterioration of the country's system of government

. Significant internal reforms

were introduced during the later part of the 18th century, but the reform process was not allowed to run its course, as the Russian Empire

, the Kingdom of Prussia

and the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy

through a series of invasions and partitions

terminated the Commonwealth's independent existence in 1795.

From then until 1918 there was no independent Polish state. The Poles had engaged intermittently in armed resistance until 1864. After the failure of the last uprising

, the nation preserved its identity through educational uplift and the program called "organic work

" to modernize the economy and society. The opportunity for freedom appeared only after World War I

, when the partitioning imperial powers were defeated by war and revolution.

The Second Polish Republic

was established and existed from 1918 to 1939. It was destroyed by Nazi Germany

and the Soviet Union

by their Invasion of Poland at the beginning of World War II

. Millions of Polish citizens perished in the course of the Nazi occupation. The Polish government in exile

kept functioning and through the many Polish military formations on the western

and eastern

fronts the Poles contributed

to the Allied

victory. Nazi Germany's forces were compelled to retreat from Poland as the Soviet Red Army

advanced, which led to the creation of the People's Republic of Poland

.

The country's geographic location was shifted to the west

and Poland existed as a Soviet satellite state

. Poland largely lost its traditional multi-ethnic

character and the communist

system was imposed. By the late 1980s Solidarity, a Polish reform movement, became crucial in causing a peaceful transition from a communist state

to the capitalist

system and parliamentary democracy

. This process resulted in the creation of the modern Polish state

.

have lived in the glaciation

disrupted environment of north Central Europe

for a long time. In prehistoric

and protohistoric

times, over the period of at least 800,000 years, the area of present-day Poland went through the Stone Age

, Bronze Age

and Iron Age

stages of development, along with the nearby regions. Settled agricultural people have lived there for the past 7500 years, since their first arrival at the outset of the Neolithic

period. Following the earlier La Tène

and Roman influence

cultures

, the Slavic

people have been in this territory for over 1500 years. They organized first into tribal units

, and then combined into larger political structure

s.

Poland during the Piast dynasty is the period of the formation and establishment of Poland as a state and a nation. The historically recorded Polish state begins with the rule of Mieszko I

Poland during the Piast dynasty is the period of the formation and establishment of Poland as a state and a nation. The historically recorded Polish state begins with the rule of Mieszko I

of the Piast dynasty

in the second half of the 10th century. Mieszko chose to be baptized

in the Western Latin Rite in 966. Mieszko completed the unification of the West Slavic

tribal lands fundamental to the new country's existence. Following its emergence, the Polish nation

was led by a series of rulers who converted the population to Christianity

, created a strong kingdom and integrated Poland into the European culture

.

Mieszko's son Bolesław I Chrobry established a Polish Church province, pursued territorial conquests and was officially crowned in 1025, becoming the first King of Poland. This was followed by a collapse of the monarchy and restoration under Casimir I. Casimir's son Bolesław II the Bold became fatally involved in a conflict with the ecclesiastical authority

, and was expelled from the country. After Bolesław III divided the country among his sons, internal fragmentation eroded the initial Piast monarchy structure in the 12th and 13th centuries. One of the regional Piast dukes

invited the Teutonic Knights

to help him fight the Baltic

Prussian

pagans, which caused centuries of Poland's warfare with the Knights and then with the German Prussian state. The Kingdom was restored under Władysław I the Elbow-high, strengthened and expanded by his son Casimir III the Great. The western provinces of Silesia

and Pomerania

were lost after the fragmentation, and Poland began expanding to the east. The consolidation in the 14th century laid the base for, after the reigns of two members of the Angevin dynasty

, the new powerful Kingdom of Poland

that was to follow.

Beginning with the Lithuanian Grand Duke

Beginning with the Lithuanian Grand Duke

Jogaila

(Władysław II Jagiełło), the Jagiellon dynasty

(1386–1572) formed the Polish–Lithuanian union. The partnership brought vast Lithuania

-controlled Rus' areas

into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for the Poles and Lithuanians

, who coexisted and cooperated in one of the largest political entities

in Europe for the next four centuries. In the Baltic Sea

region, Poland's struggle with the Teutonic Knights continued and included the Battle of Grunwald

(German: Battle of Tannenberg; Lithuanian: Battle of Žalgiris) (1410) and in 1466 the milestone Peace of Thorn under King Casimir IV Jagiellon

; the treaty created the future Duchy of Prussia. In the south, Poland confronted the Ottoman Empire

and the Crimean Tatars

, and in the east helped Lithuania fight the Grand Duchy of Moscow

. Poland was developing as a feudal

state, with predominantly agricultural economy and an increasingly dominant landed nobility

component. The Nihil novi

act adopted by the Polish Sejm

(parliament

) in 1505, transferred most of the legislative power

from the monarch

to the Sejm. This event marked the beginning of the period known as "Golden Liberty

", when the state was ruled by the "free and equal" Polish nobility

. Protestant Reformation

movements made deep inroads into the Polish Christianity, which resulted in unique at that time in Europe policies of religious tolerance

. The European Renaissance

currents evoked in late Jagiellon Poland (kings Sigismund I the Old

and Sigismund II Augustus

) an immense cultural flowering

. Poland's and Lithuania's territorial expansion included the far north region of Livonia

.

The Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin

of 1569 established the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a more closely unified federal state. The Union was largely run by the nobility, through the system of the central parliament

and local assemblies

, but led by elected kings

. The beginning of the Commonwealth coincided with the period of Poland's great power, civilizational advancement and prosperity. The Polish–Lithuanian Union had become an influential player in Europe and a vital cultural entity, spreading

the Western culture

eastward. In the second half of the 16th and the first half of the 17th century, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a huge state in central-eastern Europe, with an area approaching one million square kilometers. The Catholic Church embarked on an ideological counteroffensive and Counter-Reformation

claimed many converts from Protestant circles. The Union of Brest

split the Eastern Christians

of the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth, assertive militarily under King Stephen Báthory, suffered from dynastic distractions during the reigns of the Vasa

kings Sigismund III

and Władysław IV

. The Commonwealth fought wars with Russia

, Sweden

and the Ottoman Empire

and dealt with a series of Cossack uprisings. Allied with the Habsburg Monarchy

, it did not directly participate in the Thirty Years' War

.

Beginning in the middle of the 17th century, the nobles' democracy

Beginning in the middle of the 17th century, the nobles' democracy

, subjected to devastating wars, falling into internal disorder and then anarchy

, gradually declined, making the once powerful Commonwealth vulnerable to foreign intervention. From 1648, the Cossack Khmelnytsky Uprising

engulfed the south and east, and was soon followed by a Swedish invasion, which raged through core Polish lands. Warfare with the Cossacks and Russia left Ukraine

divided, with the eastern part, lost by the Commonwealth, becoming the Tsardom

's dependency. John III Sobieski

, fighting protracted wars with the Ottoman Empire, revived the Commonwealth's military might once more, in process helping decisively in 1683 to deliver Vienna

from a Turkish

onslaught. From there, it all went downhill. The Commonwealth, subjected to almost constant warfare until 1720, suffered enormous population losses as well as massive damage to its economy and social structure. The government became ineffective because of large scale internal conflicts (e.g. Lubomirski's Rokosz

against John II Casimir and rebellious confederation

s), corrupted legislative processes and manipulation by foreign interests. The nobility class fell under control of a handful of powerful families with established territorial domains, the urban population and infrastructure fell into ruin, together with most peasant farms. The reigns of two kings of the Saxon

Wettin dynasty, Augustus II

and Augustus III

, brought the Commonwealth further disintegration. The Great Northern War

, a period seen by the contemporaries as a passing eclipse, may have been the fatal blow destined to bring down the Noble Republic. The Kingdom of Prussia

became a strong regional power and took Silesia

from the Habsburg Monarchy

. The Commonwealth-Saxony personal union

however gave rise to the emergence of the reform movement in the Commonwealth, and the beginnings of the Polish Enlightenment

culture.

During the later part of the 18th century, the Commonwealth attempted fundamental internal reforms. The reform activity provoked hostile reaction and eventually military response on the part of the neighboring powers. The second half of the century brought improved economy and significant growth of the population. The most populous capital city of Warsaw

During the later part of the 18th century, the Commonwealth attempted fundamental internal reforms. The reform activity provoked hostile reaction and eventually military response on the part of the neighboring powers. The second half of the century brought improved economy and significant growth of the population. The most populous capital city of Warsaw

replaced Danzig

(Gdańsk) as the leading trade center, and the role of the more prosperous urban strata was increasing. The last decades of the independent Commonwealth existence were characterized by intense reform movements and far-reaching progress in the areas of education, intellectual life, art, and especially toward the end of the period, evolution of the social and political system. The royal election of 1764 resulted in the elevation of Stanisław August Poniatowski, a refined and worldly aristocrat connected to a major magnate

faction, but hand-picked and imposed by Empress Catherine II of Russia

, who expected Poniatowski to be her obedient follower. The King accordingly spent his reign torn between his desire to implement reforms necessary to save the state, and his perceived necessity of remaining in subordinate relationship with his Russian

sponsors. The Bar Confederation

of 1768 was a szlachta

rebellion directed against Russia and the Polish king, fought to preserve Poland's independence and in support of szlachtas traditional causes. It was brought under control and followed in 1772 by the First Partition of the Commonwealth

, a permanent encroachment on the outer Commonwealth provinces by the Russian Empire

, the Kingdom of Prussia

and Habsburg Austria

. The "Partition Sejm

" under duress "ratified" the partition fait accompli, but in 1773 also established the Commission of National Education, a pioneering in Europe government education authority.

The long-lasting sejm

The long-lasting sejm

convened by Stanisław August in 1788 is known as the Great, or Four-Year Sejm

. The sejms landmark achievement was the passing of the May 3 Constitution

, the first in modern Europe singular pronouncement of a supreme law of the state. The reformist but moderate document, accused by detractors of French Revolution

sympathies, soon generated strong opposition coming from the Commonwealth's upper nobility conservative circles and Catherine II, determined to prevent a rebirth of the strong Commonwealth. The nobility's Targowica Confederation

appealed to the Empress

for help and in May 1792 the Russian army entered the territory of the Commonwealth. The defensive war fought by the forces of the Commonwealth ended when the King, convinced of the futility of resistance, capitulated by joining the Targowica Confederation. The Confederation took over the government, but Russia and Prussia in 1793 arranged for and executed the Second Partition of the Commonwealth

, which left the country with critically reduced territory, practically incapable of independent existence. The radicalized by the recent events reformers, in the still nominally Commonwealth area and in exile, were soon working on national insurrection preparations. Tadeusz Kościuszko

was chosen as its leader; the popular general came from abroad and on March 24, 1794 in Cracow (Kraków)

declared

a national uprising

under his supreme command

. Kościuszko emancipated and enrolled in his army many peasants, but the hard-fought insurrection, strongly supported also by urban plebeian masses, proved incapable of generating the necessary foreign collaboration and aid. It ended suppressed by the forces of Russia and Prussia, with Warsaw captured in November. The third and final partition of the Commonwealth

was undertaken again by all three partitioning powers

, and in 1795 the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth effectively ceased to exist.

. Henryk Dąbrowski's

Polish Legions fought in French campaigns outside of Poland, hoping that their involvement and contribution result in liberation of their Polish homeland. The Polish national anthem - Dąbrowski's Mazurka - was written in praise of his actions by Józef Wybicki

in 1797. The Duchy of Warsaw

, a small, semi-independent Polish state, was created in 1807 by Napoleon Bonaparte

, following his defeat of Prussia. The Duchy's military forces, led by Józef Poniatowski

, participated in numerous campaigns, including the Polish–Austrian War of 1809, the French invasion of Russia

in 1812, and the German campaign

of 1813.

After the defeat of Napoleon, a new European order was established at the Congress of Vienna

After the defeat of Napoleon, a new European order was established at the Congress of Vienna

. Adam Czartoryski

became the leading advocate for the Polish national cause. The Congress implemented a new partition scheme, which took into account some of the gains realized by the Poles during the Napoleonic period. The Duchy of Warsaw was replaced with the Kingdom of Poland

, a residual Polish state in personal union

with the Russian Empire

, ruled by the Russian tsar. East of the Kingdom, large areas of the former Commonwealth remained directly incorporated

into the Empire; together with the Kingdom they were part of the Russian partition

. There was a Prussian partition

, with a portion of it separated as the Grand Duchy of Posen, and an Austrian partition

. The newly created Republic of Kraków

was a tiny state under a joint supervision of the three partitioning powers. "Partitions" were the lands of the former Commonwealth, not actual administrative units.

The increasingly repressive policies of the partitioning powers led to Polish conspiracies, and in 1830 to the November Uprising

in the Kingdom. The uprising developed into a full-scale war with Russia, but the leadership was taken over by the Polish conservative circles reluctant to challenge the Empire, and hostile to broadening the independence movement's social base through measures such as land reform

. Despite the significant resources mobilized and self-sacrifice of the participants, a series of missteps by several successive unwilling or incompetent chief commanders appointed by the Polish government ultimately led to the defeat of the insurgents by the Russian army. After the fall of the Uprising, thousands of former Polish combatants and other activists emigrated to Western Europe, where they were initially enthusiastically received. This element, known as the Great Emigration

, soon dominated the Polish political and intellectual life. Together with the leaders of the independence movement, the exile community included the greatest Polish literary and artistic minds, including the Romantic

poets Adam Mickiewicz

, Juliusz Słowacki, Cyprian Norwid

, and composer Frédéric Chopin

. Within the occupied and repressed Poland, some sought progress through self-improvement oriented activities known as organic work

, others, in cooperation with the emigrant circles, organized conspiracies and prepared for the next armed insurrection.

The planned national uprising, after authorities in the partitions had found out about secret preparations, ended in a fiasco in early 1846. In its most significant manifestation, the Kraków Uprising

of February 1846, patriotic action was combined with revolutionary demands, but the result was the incorporation of the Republic of Kraków into the Austrian partition. Peasant discontent was taken advantage of by the Austrian authorities, who incited the villagers against noble-dominated insurgent units; it led to the Galician slaughter

, a violent anti-feudal rebellion, beyond the intended scope of the provocation. A new wave of Polish military and other involvement, in the partitions and in other parts of Europe, soon took place in the context of the 1848 Spring of Nations

revolutions. In particular, the Berlin events

precipitated the Greater Poland Uprising, where prominent role was played by the by then largely enfranchised in Prussia peasants.

A renewal of popular liberation activities took place in 1860-1861; during the large scale demonstrations in Warsaw the Russian forces inflicted numerous casualties on the civilian participants. The "Red", or left-wing conspiracy faction, which promoted peasant enfranchisement and cooperated with Russian revolutionaries, became involved in immediate preparations for a national uprising. The "White", or right-wing faction, inclined to cooperate with the Russian authorities, countered with partial reform proposals. The conservative leader of the Kingdom's government Aleksander Wielopolski

A renewal of popular liberation activities took place in 1860-1861; during the large scale demonstrations in Warsaw the Russian forces inflicted numerous casualties on the civilian participants. The "Red", or left-wing conspiracy faction, which promoted peasant enfranchisement and cooperated with Russian revolutionaries, became involved in immediate preparations for a national uprising. The "White", or right-wing faction, inclined to cooperate with the Russian authorities, countered with partial reform proposals. The conservative leader of the Kingdom's government Aleksander Wielopolski

, in order to cripple the manpower potential of the Reds, arranged for a partial selective conscription of young Poles for the Russian army, which hastened the outbreak of the hostilities. The January Uprising

, joined and led after the initial period by the Whites, was fought by partisan units against an overwhelming enemy advantage. The warfare was limited to the Kingdom and lasted from January 1863 to the spring of 1864, when Romuald Traugutt

, the dedicated last supreme commander of the insurgence, was captured by the tsarist

police.

On March 2, 1864, the Russian authority — compelled by the uprising to compete for the loyalty of Polish peasants — officially published an enfranchisement decree in the Kingdom, along the lines of an earlier insurgent land reform proclamation. The act created the conditions necessary for the development of the capitalist system on central Polish lands. At the time when the futility of armed resistance without external support was realized by most Poles, the various segments of the Polish society were undergoing deep and far-reaching social, economic and cultural transformations.

, downgraded in official usage from the Kingdom of Poland to the Vistula Land

, was more fully integrated into Russia proper, but not entirely obliterated. The Russian and German languages were respectively imposed in all public communication and the Catholic Church was not spared from severe repression. On the other hand the Galicia region in western Ukraine and southern Poland, economically and socially backward, but under the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy

rule increasingly allowed limited autonomy, experienced gradual relaxation of authoritarian policies and even a Polish cultural revival. Positivism

replaced Romanticism as the leading intellectual, social and literary trend.

"Organic work

" social activities consisted of self-help organizations that promoted economic advancement and worked on improving competitiveness of Polish-held business entities, industrial, agricultural, or other. New commercial methods and ways of generating higher productivity were discussed and implemented through trade associations and special interest groups, while Polish banking and cooperative financial institutions made necessary business loans available. The other major area of organic work concern was education and intellectual development of the common people. Many libraries and reading rooms were established in small towns and villages, and numerous printed periodicals reflected the growing interest in popular education. Scientific and educational societies were active in a number of cities.

Economic and social changes, such as land reform and industrialization, combined with the effects of foreign domination, altered the centuries old social structure of the Polish society. Among the newly emergent strata were wealthy industrialists and financiers, distinct from the traditional, but still critically important landed aristocracy. The intelligentsia

, an educated, professional or business middle class, often originated from gentry alienated from their rural possessions (many smaller serfdom

-based agricultural enterprises

had not survived the land reforms) and from urban people. Industrial proletariat

, the new underprivileged class, were usually poor peasants or townspeople forced by deteriorating conditions to migrate and search for work in urban centers in countries of their origin or abroad. Millions of residents of the former Commonwealth of various ethnic backgrounds

worked or settled in Europe and in North and South America.

The changes were partial and gradual, and the degree of the fast-paced in some areas industrialization and capitalist development on Polish lands lagged behind the advanced regions of western Europe. The three partitions developed different economies, and were economically integrated with their mother states more than with each other. In the 1870s-1890s, large scale socialist

, nationalist

and agrarian

movements of great ideological fervor and corresponding political parties became established in partitioned Poland and Lithuania. The main minority ethnic groups of the former Commonwealth, including Ukrainians

, Lithuanians, Belarusians

and Jews

, were getting involved in their own national movements and plans, which met with disapproval on the part of those ethnically Polish independence activists, who counted on an eventual rebirth of the Commonwealth. Around the turn of the century the Young Poland

cultural movement

, centered on Galicia and taking advantage of the conducive to liberal expression milieu there, was the source of Poland's finest artistic and literary productions.

The 1905 Russian Revolution arose new waves of Polish unrest, political maneuvering, strikes and rebellion, with Roman Dmowski

and Józef Piłsudski active as leaders of the nationalist and socialist

factions respectively. As the authorities reestablished control within the Empire

, the revolt in the Kingdom

, placed under martial law, had withered as well, leaving tsarist concessions in the areas of national and workers' rights, including Polish representation in the newly created Russian Duma

. Some of the acquired gains were however rolled back, which coupled with intensified Germanization

in the Prussian partition, left the Austrian Galicia

as the most amenable to patriotic action territory.

After the outbreak of World War I

After the outbreak of World War I

, which confronted the partitioning powers against each other, Piłsudski's paramilitary units stationed in Galicia were turned into the Polish Legions

, and as a part of the Austro-Hungarian Army

fought on the Russian front.

World War I and the political turbulence that was sweeping Europe in 1914 offered the Polish nation hopes for regaining independence. On the outbreak of war the Poles found themselves conscripted

into the armies of Germany, Austria and Russia, and forced to fight each other in a war that was not theirs. Although many Poles sympathized with France and Britain, they found it hard to fight for their ally, Russia. They also had little sympathy for the Germans. Total deaths

from 1914 to 1918, military and civilian, within the 1919–1939 borders, were estimated at 1,128,000. By the end of World War I Poland had seen the defeat or retreat of all three partitioning powers.

As the area of Congress Poland became occupied by the Central Powers

, with the act of November 5, 1916 the Kingdom of Poland

(Królestwo Regencyjne) was recreated by Imperial Germany

and Austria-Hungary

on formerly Russian-controlled territory. This new puppet state

existed until November 1918, when it was replaced by the newly established Republic of Poland

. The independence of Poland had been campaigned for in the West by Dmowski and Ignacy Paderewski

. With Woodrow Wilson's support

, Polish independence was officially endorsed in June 1918 by the Entente Powers

, on whose fronts sizable armies of Polish volunteers had been mobilized and fought. On the ground in Poland in October–November the final upsurge of the push for independence was taking place, with Ignacy Daszyński

heading a short-lived Polish government in Lublin

from November 6. Germany

decided to withdraw its forces from Warsaw and released imprisoned Piłsudski, who arrived in Warsaw on November 10.

After more than a century of rule by its neighbors, Poland regained its independence

After more than a century of rule by its neighbors, Poland regained its independence

in 1918, internationally recognized in 1919 with the Treaty of Versailles

. The Paris Peace Conference

and the Versailles treaty that followed resolved the issue of Poland's western border with Germany, including the Polish Corridor

, which gave Poland access to the Baltic Sea

, and the separate status of the Free City of Danzig

. Plebiscites in southern East Prussia

and Upper Silesia

were provided for, while the issues of other northern, eastern and southern borders remained undetermined, inviting military action.

Of the several border-settling conflicts that ensued, the Polish–Soviet War of 1919-1921 was the confrontation fought on a very large scale. Piłsudski had entertained far-reaching anti-Russian cooperative designs for Eastern Europe, and in 1919 the Polish forces pushed eastward into Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine (previously a theater of the Polish–Ukrainian War), taking advantage of the Russian preoccupation with the civil war

. By June 1920, the Polish armies were past Vilnius

, Minsk

and (allied with the Directorate of Ukraine

) reached Kiev, but then the massive Bolshevik

counteroffensive moved the Poles out of most of Ukraine and on the northern front arrived at the outskirts of Warsaw. The seemingly certain disaster was averted

in August by the combination of Piłsudski's military skills and a dedicated national defense effort.

The Russian armies were separated, defeated and pushed back, which forced Lenin

The Russian armies were separated, defeated and pushed back, which forced Lenin

and the Soviet

leadership to abandon for the time being their strategic objective of linking up with the German and other European revolution-minded comrades (Lenin's hope of generating support for the Red Army

in Poland had already failed to materialize). Piłsudski's seizure of Vilnius in October 1920 poisoned Polish–Lithuanian relations for the remainder of the interwar period

. Piłsudski's planned East European federation of states (inspired by the tradition of the binational and multiethnic Commonwealth) was incompatible, at the time of rising national movements, with his assumption of Polish domination and with the encroachment on the neighboring peoples' lands and aspirations; as such it was doomed to failure. A larger federated structure was also opposed by Dmowski's National Democrats. Their representative at the Peace of Riga

talks opted for leaving Minsk

area on the Soviet side of the border, not wanting the ethnically Polish element overly diluted. The successful outcome of the war gave Poland a false sense of being a major and self-sufficient military power, and the government a justification for trying to resolve international problems through imposed unilateral solutions. The interwar period's Polish territorial and ethnic policies contributed to bad relations with most of Poland's neighbors and to uneasy cooperation with the more distant centers of power, including France, Britain and the League of Nations

. The Treaty of Riga

of 1921 settled the eastern border, preserving for Poland, at the cost of partitioning the ethnic Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine, a good portion

of the old Commonwealth's eastern lands.

The rapidly growing population of Poland within the new boundaries was ¾ agricultural and ¼ urban, with Polish being the primary language of ⅔ of the inhabitants. A constitution

was adopted in 1921. Due to the insistence of the National Democrats, worried about the potential power of Piłsudski if elected, it introduced limited prerogatives for the presidency.

What followed was the Second Republic's short (1921–1926) and turbulent period of constitutional order and parliamentary democracy

. The legislature remained fragmented and lacking stable majorities, governments changed frequently, corruption was commonplace. The open-minded Gabriel Narutowicz

was constitutionally elected president by the National Assembly in 1922, but deemed not pure enough by the nationalist right wing, was assassinated. Poland had suffered under a plethora of economic calamities, but there were also signs of progress and stabilization (Władysław Grabski's economically competent government lasted for almost two years). The achievements of the democratic period, such as the establishment, strengthening or expansion of the various governmental and civil society

structures and integrative processes necessary for normal functioning of the reunited state and nation, were too easily overlooked. Lurking on the sidelines was the disgusted army upper corps, not willing to subject itself to civilian control, but ready to follow its equally dissatisfied, at that time retired, legendary chief.

On May 12, 1926, Piłsudski, prompted by mutinous units seeking his leadership and intent on preventing the three-time prime minister Wincenty Witos

of the peasant Polish People's Party from forming another coalition, staged a military overthrow of the Polish government, confronting President Stanisław Wojciechowski and overpowering the troops loyal to him. Piłsudski was supported by several leftist factions, who ensured the success of his coup by blocking during the fighting the railway transportation of government forces, but the authoritarian

"Sanation" regime that he was to lead for the rest of his life and that stayed in power until World War II

, was neither leftist, nor overtly fascist

. Political institutions and parties were allowed to function, which was combined with electoral manipulation and strong-arming of those not willing to cooperate into submission. Eventually persistent opponents of the regime, many of the leftist persuasion, were subjected to long staged trials

and harsh sentences, or detained in camps for political prisoners

. Rebellious peasants

, striking industrial workers and nationalist Ukrainians became targets of ruthless military pacification, other minorities were harassed. Piłsudski, conscious of Poland's precarious international situation, signed non-aggression pacts with the Soviet Union in 1932 and with Nazi Germany in 1934.

The mainstream of the Polish society was not affected by the repressions of the Sanation authorities, many enjoyed the relative prosperity (the economy improved between 1926 and 1929) and supported the government. Polish independence had boosted the development of thriving culture

and intellectual achievement was high, but the Great Depression

brought huge unemployment and increased social tensions, including rising antisemitism. The reconstituted Polish state had had only 20 years of relative stability and uneasy peace between the two wars

. A major economic transformation and national industrial development plan led by Minister Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski

, the main architect of the Gdynia seaport

project, was in progress at the time of the outbreak of the war

. The interwar period's overall economic situation in Poland was however stagnant. The total industrial production (within the pre-1939 borders) had barely increased between 1913 and 1939, but because of the population growth, the per capita output actually decreased by 17.8%.

The lack of sufficient domestic or foreign investment funding precluded by 1939 the level of industrial development necessary for creating modern armed forces for successful self-defense; because of its strategic and tactical priorities, the ruling establishment had not primarily prepared the country for a major war on the western front. The regime of Piłsudski's "colonels", left in power after the marshal's death, had neither the vision nor resources to cope with the deteriorating situation in Europe. The government (foreign policy conduct was the responsibility of Józef Beck

The lack of sufficient domestic or foreign investment funding precluded by 1939 the level of industrial development necessary for creating modern armed forces for successful self-defense; because of its strategic and tactical priorities, the ruling establishment had not primarily prepared the country for a major war on the western front. The regime of Piłsudski's "colonels", left in power after the marshal's death, had neither the vision nor resources to cope with the deteriorating situation in Europe. The government (foreign policy conduct was the responsibility of Józef Beck

) undertook opportunistic hostile actions against Lithuania

and Czechoslovakia, while it failed to control the increasingly fractured situation at home, where fringe groups and extreme nationalist circles were getting more outspoken (one Camp of National Unity was connected to the new strongman, Marshal Edward Rydz-Śmigły).

In 1939 the Polish government rejected the German offer of forming an alliance on terms which would amount to an end or severe curtailment of Poland's sovereignty; Hitler

abrogated the Polish-German pact. Before the war broke out, Poland entered into a full military alliance with Britain and France; the western powers lacked the will to confront Nazi Germany

and their (false) assurances of imminent military action were only intended as pressure applied to deter Hitler. The mid-August British-French talks with the Soviets on forming an anti-Nazi defensive military alliance had failed, in part over the Polish government's refusal to allow the Red Army to operate on Polish territory. On August 23, 1939 Germany and the Soviet Union signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop non-aggression pact, which secretly provided for the dismemberment of Poland into Nazi

and Soviet-controlled zones.

On September 1, 1939 Hitler ordered his troops into Poland. Poland had signed a pact with Britain (as recently as August 25) and France and the two western powers soon declared a war

On September 1, 1939 Hitler ordered his troops into Poland. Poland had signed a pact with Britain (as recently as August 25) and France and the two western powers soon declared a war

on Germany, but remained rather inactive and extended no aid to the attacked country. On September 17, the Soviet troops moved in

and took control of most of the areas of eastern Poland having significant Ukrainian

and Belarusian

populations under the terms of the German-Soviet agreement. While Poland's military forces were fighting the invading armies, Poland's top government officials and military high command left the country (September 17/18). Among the military operations that held out the longest (until late September or early October) were the Defense of Warsaw

, the Defense of Hel

and the resistance of the Polesie Group

.

Fighting the initial "September Campaign" of World War II was the most significant Polish contribution to the allied war effort

. The nearly one million Polish soldiers mobilized significantly delayed Hitler's attack on Western Europe

, planned for 1939. When the Nazi offensive did happen, the delay caused it to be less effective, a possibly crucial factor in the case of the defense of Britain

.

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Poland was completely occupied by German troops.

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Poland was completely occupied by German troops.

The Poles formed an underground resistance movement and a Polish government in exile, first in Paris

and later in London

, which was recognized by the Soviet Union (diplomatic relations, broken since September 1939, were resumed in July 1941). During World War II, about 300,000 Poles fought under the Soviet command

, and about 200,000 went into combat on western fronts

in units loyal to the Polish government in exile.

In April 1943, the Soviet Union broke the deteriorating relations with the Polish government in exile after the German military announced that they had discovered mass graves of murdered Polish army officers

at Katyn, in the USSR

. The Soviets claimed that the Poles had committed a hostile act by requesting that the Red Cross

investigate these reports.

As the Jewish

ghetto in occupied Warsaw

was being liquidated by the Nazi SS

units, in 1943 the city was the scene of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

. The eliminations of the ghettos took place in Polish cities and uprisings were fought there against impossible odds by desperate Jewish insurgents, whose people were being removed and exterminated.

At the time of the western Allies' increasing cooperation with the Soviet Union, the standing and influence of the Polish government in exile were seriously diminished by the death of its most prominent leader — Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski — on July 4, 1943.

At the time of the western Allies' increasing cooperation with the Soviet Union, the standing and influence of the Polish government in exile were seriously diminished by the death of its most prominent leader — Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski — on July 4, 1943.

In July 1944, the Soviet Red Army

and the People's Army of Poland controlled by the Soviets entered Poland, and through protracted fighting in 1944 and 1945 defeated the Germans, losing 600,000 of their soldiers. Initially, a communist

-controlled "Polish Committee of National Liberation

" was established in Lublin

.

The greatest single instance of armed struggle in the occupied Poland

and a major political event of World War II was the Warsaw Uprising

of 1944. The uprising, in which most of the Warsaw population participated, was instigated by the underground Armia Krajowa

(Home Army) and approved by the Polish government in exile, in an attempt to establish a non-communist Polish administration ahead of the approaching Red Army. The uprising was planned with the expectation that the Soviet forces, who had arrived in the course of their offensive and were present on the other side of the Vistula River

, would help in battle over Warsaw. However, the Soviets stopped their advance at the Vistula and were mostly passive as the Germans brutally suppressed the forces of the pro-Western Polish underground.

The bitterly fought uprising lasted for two months and resulted in hundreds of thousands of civilians killed and expelled. After a hopeless surrender on the part of the Poles (October 2), the Germans carried out Hitler's order to destroy the remaining infrastructure of the city. The Polish First Army

The bitterly fought uprising lasted for two months and resulted in hundreds of thousands of civilians killed and expelled. After a hopeless surrender on the part of the Poles (October 2), the Germans carried out Hitler's order to destroy the remaining infrastructure of the city. The Polish First Army

, fighting along the Soviet Red Army, entered Warsaw on 17 January 1945.

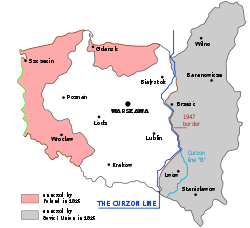

As a consequence of the war and by the decision of the Soviet leadership, agreed to by the United States and Britain beginning with the Tehran Conference

(late 1943), Poland's geographic location was fundamentally altered. Stalin

's proposal that Poland should be moved very far to the west was readily accepted by Polish communists

, who were at that time at the early stages of forming the post-war government

.

By the time of the Yalta Conference

(February 1945), seen by many Poles as the pivotal point when the nation's fate was sealed

by the Great Powers, the communists had established a provisional government in Poland. The Soviet position at the Conference was strong, corresponding to their advance on the German battlefield. The three Great Powers gave assurances for the conversion of the communist provisional government, by including in it democratic forces from within the country and currently active abroad (the Provisional Government of National Unity

and subsequent democratic elections were the agreed stated goals), but the London-based government in exile was not mentioned.

After the final (for all practical purposes) settlement at Potsdam

After the final (for all practical purposes) settlement at Potsdam

, the Soviet Union retained most of the territories captured as a result of the 1939 German-Soviet pact (now western Ukraine

, western Belarus

and part of Lithuania

around Vilnius

). Poland was compensated with parts of Silesia

including Breslau (Wrocław) and Grünberg (Zielona Góra)

, of Pomerania

including Stettin (Szczecin)

, and of East Prussia

, along with Danzig (Gdańsk)

, collectively referred to as the "Recovered Territories

", which were incorporated into the reconstituted Polish state. Most of the German population there was expelled to Germany

.

Scientific and numerically correct estimation of the human losses suffered by Polish citizens during World War II does not seem possible because of the paucity of available data. Some conjectures can be arrived at and they suggest that assertions made in the past have been incorrect and motivated by political needs. To begin with, the total population of 1939 Poland and of the several nationalities/ethnicities

present there are not accurately known, since the last population census took place in 1931

.

Modern research indicates that during the war about 5 million Polish citizens were killed, including 3 million Polish Jews

. According to the Holocaust Memorial Museum

, at least 1.9 to two million ethnic Poles and 3 million Polish Jews were killed, and 2.5 million were deported to Germany for forced labor or to German extermination camps such as Treblinka

and Auschwitz

. According to a recent estimate, between 2.35 and 2.9 million Polish Jews and about 2 million ethnic Poles were killed (almost all of the Jewish losses and 90% of the Polish losses were caused by Nazi Germany). This Jewish loss of life, together with the numerically much less significant waves of displacement during the war and emigration after the war, after the Polish October

1956 thaw and following the 1968 Polish political crisis, put an end to several centuries of large scale, well-established Jewish settlement and presence in Poland

. The magnitudes of the (also substantial) losses of Polish citizens of German, Ukrainian, Belarusian and other nationalities are not known.

In 1940-1941, some 325,000 Polish citizens were deported by the Soviet regime. The number of Polish citizen deaths at the hands of the Soviets is estimated at less than 100,000. In 1943–1944, Ukrainian nationalists (OUN

and Ukrainian Insurgent Army) massacred tens of thousands of Poles in Volhynia and Galicia

.

Approximately 90% of Polish war losses (Jews and Gentiles) were the victims of prisons, death camps, raids, executions, annihilation of ghettos, epidemics, starvation, excessive work and ill treatment. There were one million war orphans and 590,000 war disabled. The country lost 38% of its national assets (Britain lost 0.8%, France 1.5%). Nearly half the prewar Poland was expropriated by the Soviet Union, including the two great cultural centers of Lwów

Approximately 90% of Polish war losses (Jews and Gentiles) were the victims of prisons, death camps, raids, executions, annihilation of ghettos, epidemics, starvation, excessive work and ill treatment. There were one million war orphans and 590,000 war disabled. The country lost 38% of its national assets (Britain lost 0.8%, France 1.5%). Nearly half the prewar Poland was expropriated by the Soviet Union, including the two great cultural centers of Lwów

and Wilno

. Many Poles could not return to the country for which they had fought because they belonged to the "wrong" political group, or came from prewar eastern Poland incorporated into the Soviet Union (see Polish population transfers (1944–1946)), or having fought in the West were warned not to return because of the high risk of persecution. Others were arrested, tortured and imprisoned by the Soviet authorities for belonging to the Home Army (see Cursed soldiers

), or persecuted because of having fought on the western front.

With Germany's defeat, as the reestablished Polish state was shifted west to the area between the Oder-Neisse

and Curzon

lines, the Germans who had not fled were expelled

. Of those who remained, many chose to emigrate to post-war Germany

. According to a recently quoted estimate, of the 200-250 thousand Jews who escaped the Nazis, 40-60 thousand had survived in Poland. More had been repatriated from the Soviet Union and elsewhere, and the February 1946 population census showed ca. 300,000 Jews within the new borders. Of the surviving Jews, many chose or felt compelled to emigrate. Many Ukrainians remaining in Poland were forcibly moved to Soviet Ukraine (see Repatriation of Ukrainians from Poland to the Soviet Union), and to the new territories in northern and western Poland under Operation Vistula. Because of the changing borders and of mass movements of people of various nationalities, sponsored by governments and spontaneous, the emerging communist Poland ended up with a mainly homogeneous, ethnically Polish population (97.6% according to the December 1950 census). The remaining members of the minorities were not encouraged, by the authorities or by their neighbors, to emphasize their ethnic identity.

In June 1945, as an implementation of the February Yalta Conference

In June 1945, as an implementation of the February Yalta Conference

directives, according to the Soviet interpretation, a Polish Provisional Government of National Unity

was formed; it was soon recognized by the United States and many other countries. A national referendum

arranged for by the communist

Polish Workers' Party

was used to legitimize its dominance in Polish politics and claim widespread support for the party's policies. Although the Yalta agreement called for free elections, those held in January 1947

were controlled by the communists. Some democratic and pro-Western elements, led by Stanisław Mikołajczyk, the former Prime Minister in Exile, participated in the Provisional National Unity Government and the 1947 elections, but were ultimately eliminated through electoral fraud

, intimidation and violence. In times of radical change, they attempted to preserve some degree of mixed economy

.

A Polish People's Republic

(Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa) was created under the communist Polish United Workers' Party

rule after the brief period of coalition "National Unity" government. The ruling party

itself was a result of the forced amalgamation (December 1948) of the communist Polish Workers' Party and the historically non-communist, more popular Polish Socialist Party

(the party, reestablished in 1944, had been from that time allied with the communists). The ruling communists, who in post-war Poland preferred to use the term "socialism", needed to include the socialist junior partner to broaden their appeal, claim greater legitimacy and eliminate competition on the left

. The socialists, who were losing their organization, had to be subjected to political pressure, ideological cleansing and purges in order to become suitable for the unification on the "Workers' Party"'s terms.

During the most oppressive Stalinist

During the most oppressive Stalinist

period, terror, justified by the necessity to eliminate the reactionary subversion, was widespread; many thousands of perceived opponents of the regime were arbitrarily tried and large numbers executed. The People's Republic was led by discredited Moscow

's operatives such as Bolesław Bierut and Konstantin Rokossovsky

.

Larger rural estates and agricultural holdings as well as post-German property were redistributed through land reform

and industry was nationalized

beginning in 1944. The Three-Year Plan

(1947–1949) continued with the rebuilding, socialization

and restructuring of the economy. The rejection of the Marshall Plan

however made the aspirations to catch-up with the West European

standard of living unrealistic. The government's economic high priority was the development of militarily useful heavy industry. State-run institutions, collectivization and cooperative entities were imposed (the last category dismantled in the 1940s as not socialist enough, later reestablished), while even small-scale private enterprises were being eradicated. Great strides however were made in the areas of universal public education (including elimination of adult illiteracy), health care and recreational amenities for working people. Many historic sites, including central districts of war-destroyed Warsaw and Gdańsk (Danzig), were rebuilt at a great cost. The Polish government in exile

existed until 1990, although its influence was degraded.

In October 1956, after the 20th Soviet Party Congress in Moscow ushered in de-Stalinization

and riots by workers in Poznań

ensued, there was a shakeup in the communist regime. While retaining most traditional communist economic and social aims, the regime led by the Polish Communist Party

's First Secretary Władysław Gomułka began to liberalize internal life in Poland

. Several years of relative stabilization followed the legislative election of 1957

.

In 1965, the Conference of Polish Bishops

issued the Letter of Reconciliation of the Polish Bishops to the German Bishops

. In 1966, the celebrations of the 1,000th anniversary of the Baptism of Poland

led by Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński and other bishops turned into a huge demonstration of the power and popularity of the Polish Catholic Church

.

Sophisticated cultural life developed under Gomułka and his successors, even if the creative process had often been compromised by state censorship. Significant productions were accomplished in fields such as literature, theater, cinema and music, among others. Journalism of veiled understanding and native varieties of popular trends and styles of western mass culture

were well represented. Uncensored information and works generated by émigré

circles were conveyed by a variety of channels, the Radio Free Europe being of foremost importance.

In 1968, the liberalizing trend was reversed when student demonstrations were suppressed and an anti-Zionist

campaign initially directed against Gomułka supporters within the party eventually led to the emigration of much of Poland's remaining Jewish population. In August 1968, the Polish People's Army took part in the infamous Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia

.

In 1970, the governments of Poland and West Germany

signed a treaty

which normalized their relations and in which the Federal Republic

recognized the post-war de facto borders between Poland and East Germany.

In December 1970, disturbances and strikes in the port cities

In December 1970, disturbances and strikes in the port cities

of Gdańsk

(Danzig), Gdynia

, and Szczecin

(Stettin), triggered by a price increase for essential consumer goods, reflected deep dissatisfaction with living and working conditions in the country. Edward Gierek

replaced Gomułka as First Secretary.

Fueled by large infusions of Western credit, Poland's economic growth rate was one of the world's highest during the first half of the 1970s. But much of the borrowed capital was misspent, and the centrally planned economy

was unable to use the new resources effectively. The growing debt burden became insupportable in the late 1970s, and economic growth had become negative by 1979. The Workers' Defense Committee

(KOR) established in 1976 consisted of dissident intellectuals willing to openly support industrial workers struggling with the authorities.

In October 1978, the Archbishop of Kraków, Cardinal Karol Józef Wojtyła

, became Pope John Paul II

, head of the Roman Catholic Church. Polish Catholics rejoiced at the elevation of a Pole to the papacy

and greeted his June 1979 visit to Poland with an outpouring of emotion.

On July 1, 1980, with the Polish foreign debt at more than $20 billion, the government made another attempt to increase meat prices. A chain reaction of strikes

virtually paralyzed the Baltic coast by the end of August and, for the first time, closed most coal mines in Silesia

. Poland was entering into an extended crisis that would change the course of its future development.

On August 31, workers at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk

, led by an electrician named Lech Wałęsa

, signed a 21-point agreement with the government

that ended their strike. Similar agreements were signed at Szczecin and in Silesia. The key provision of these agreements was the guarantee of the workers' right to form independent trade union

s and the right to strike. After the Gdańsk Agreement

was signed, a new national union movement "Solidarity" swept Poland.

The discontent underlying the strikes was intensified by revelations of widespread corruption and mismanagement within the Polish state and party leadership. In September 1980, Gierek was replaced by Stanisław Kania as First Secretary.

Alarmed by the rapid deterioration of the PZPR's

authority following the Gdańsk agreement, the Soviet Union proceeded with a massive military buildup along Poland's border in December 1980. In February 1981, Defense Minister Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski

assumed the position of Prime Minister, and in October 1981, was named First Secretary of the Communist Party. At the first Solidarity national congress

in September–October 1981, Lech Wałęsa was elected national chairman of the union.

On December 12–13, the regime declared martial law

, under which the army and ZOMO

riot police were used to crush the union. Virtually all Solidarity leaders and many affiliated intellectuals were arrested or detained. The United States and other Western countries responded to martial law by imposing economic sanctions against the Polish regime and against the Soviet Union. Unrest in Poland continued for several years thereafter.

Having achieved some semblance of stability, the Polish regime in several stages relaxed and then rescinded martial law. By December 1982, martial law was suspended, and a small number of political prisoners (including Wałęsa) were released. Although martial law formally ended in July 1983 and a general amnesty was enacted, several hundred political prisoners remained in jail.

In July 1984, another general amnesty was declared, and two years later, the government had released nearly all political prisoners. The authorities continued, however, to harass dissidents and Solidarity activists. Solidarity remained proscribed and its publications banned. Independent publications were censored.

The government's inability to forestall Poland's economic decline led to waves of strikes across the country in April, May and August 1988. With the Soviet Union increasingly destabilized, in the late 1980s the government was forced to negotiate with Solidarity in the Polish Round Table Negotiations

. The resulting Polish legislative election in 1989

became one of the important events marking the fall of communism

in Poland.

The "round-table" talks

The "round-table" talks

with the opposition began in February 1989. These talks produced the Round Table Agreement

in April for partly open National Assembly elections

. The failure of the communists at the polls produced a political crisis. The agreement called for a communist president

, and on July 19, the National Assembly

, with the support of a number of Solidarity deputies, elected General Wojciech Jaruzelski

to that office. However, two attempts by the communists to form governments failed.

On August 19, President Jaruzelski asked journalist/Solidarity activist Tadeusz Mazowiecki

to form a government; on September 12, the Sejm (national legislature) voted approval of Prime Minister Mazowiecki and his cabinet. For the first time in more than 40 years, Poland had a government led by noncommunists.

In December 1989, the Sejm approved the government's reform program to transform the Polish economy rapidly from centrally planned to free-market, amended the constitution

to eliminate references to the "leading role" of the Communist Party, and renamed the country the "Republic of Poland." The Polish United Workers' (Communist) Party

dissolved itself in January 1990, creating in its place a new party, Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland

.

In October 1990, the constitution was amended to curtail the term of President Jaruzelski.

In the early 1990s, Poland made great progress towards achieving a fully democratic government and a market economy. In November 1990, Lech Wałęsa was elected president

for a five-year term. In December Wałęsa became the first popularly elected President of Poland.

Poland's first free parliamentary election

was held in 1991. More than 100 parties participated, and no single party received more than 13% of the total vote. In 1993 parliamentary election

the "post-communist" Democratic Left Alliance

(SLD) received the largest share of votes. In 1993 the Soviet Northern Group of Forces

finally left Poland.

In November 1995, Poland held its second post-war free presidential election

. SLD leader Aleksander Kwaśniewski

defeated Wałęsa by a narrow margin—51.7% to 48.3%.

In 1997 parliamentary election

two parties with roots in the Solidarity movement — Solidarity Electoral Action

(AWS) and the Freedom Union

(UW) — won 261 of the 460 seats in the Sejm and formed a coalition government. In April 1997, the new Constitution of Poland

was finalized, and in July put into effect, replacing the previously used amended

communist statute

.

Poland joined NATO in 1999. Elements of the Polish Armed Forces

Poland joined NATO in 1999. Elements of the Polish Armed Forces

have since participated in the Iraq War and the Afghanistan War

.

In the presidential election of 2000

, Aleksander Kwaśniewski, the incumbent former leader of the SLD

, was re-elected in the first round of voting. After September 2001 parliamentary election

SLD (a successor of the communist party) formed a coalition with the agrarian Polish People's Party (PSL) and the leftist Labor Union

(UP).

Poland joined the European Union

in May 2004. Both President Kwaśniewski and the government were vocal in their support for this cause. The only party decidedly opposed to EU entry was the populist right-wing League of Polish Families

(LPR).

After the fall of communism the government policy of guaranteed full employment had ended and many large unprofitable state enterprises were closed or restructured. This and other economic woes of the transition period caused the unemployment to be at times as high as 20%. With the EU

access, the gradual opening of West European labor markets to Polish workers, combined with the domestic economic growth, led to marked improvement in the employment situation (currently at above 10%) in Poland.

September's 2005 parliamentary election

was expected to produce a coalition of two center-right parties, PiS (Law and Justice

) and PO (Civic Platform

). During the bitter campaign PiS overtook PO, gaining 27% of votes cast and becoming the largest party in the Sejm, ahead of PO with 24%. In the presidential election in October

the early favorite, Donald Tusk

, leader of the PO, was beaten 54% to 46% in the second round by the PiS candidate Lech Kaczyński

.

Coalition talks ensued simultaneously with the presidential elections, but negotiations ended up in a stalemate and the PO decided to go into opposition. PiS formed a minority government which relied on the support of smaller populist and agrarian parties (Samoobrona

, LPR

) to govern. This became a formal coalition, but its deteriorating state made early parliamentary election necessary.

In the 2007 parliamentary election

, the Civic Platform was most successful (41.5%), ahead of Law and Justice (32%), and the government of Donald Tusk, the chairman of PO, was formed. PO governs in a parliamentary majority coalition with the smaller Polish People's Party (PSL).

In the current great worldwide economic downturn, triggered and exemplified in particular by the 2008 USA collapse and bailout of the banking system

, the Polish economy has weathered the crisis, in comparison with many European and other countries, relatively unscathed. Worrisome signs, signalling upcoming difficulties are however present, and the European sovereign debt crisis, unraveling some of Europe's economies, is expected to negatively affect also the economy of Poland, currently not a member of the eurozone

.

The social price paid by the Poles for the implementation of liberal free market economic policies

has been the sharply more inequitable distribution of wealth and the associated impoverishment of large segments of the society.

Poland's president Lech Kaczyński and all aboard died in a plane crash on April 10, 2010 in western Russia, near Smolensk

. President Kaczyński and other prominent Poles were on the way to the Katyn massacre

anniversary commemoration.

In the second final round of the Polish presidential election on July 4, 2010, Bronisław Komorowski, Acting President, Marshal of the Sejm and a Civic Platform politician, defeated Jarosław Kaczyński by 53% to 47%.

The Smolensk tragedy brought into the open deep divisions within the Polish society and became a destabilizing factor in Poland's politics.

Poland's relations with its European neighbors have been good or improving, with Belarus

being a sore point

. The Eastern Partnership

summit, hosted in September 2011 by Poland, the holder of the rotating Presidency of the Council of the European Union

, resulted in no agreement on near future expansion of the Union to include the several considered Eastern Europe

an and Caucasus

states, formerly Soviet republics

. The European Union membership for at least some of those states, including Ukraine

, has long been a goal of Polish diplomacy. Poland has also been promoting NATO membership for Ukraine and Georgia

, a plan seen by Russia as threatening to its security.

The 2011 parliamentary election

results were generally an affirmation of the current distribution of political forces. The Civic Platform

won over 39% of the votes, Law and Justice

almost 30%, Palikot's Movement 10%, the Polish People's Party and the Democratic Left Alliance

over 8% each. The new element was the successful debut of the left-of-center movement of Janusz Palikot

, a maverick politician, which resulted in decreased electoral appeal of the Democratic Left Alliance.

Poland's foreign minister, Radosław Sikorski, delivered a speech on 28 November 2011 in Berlin, in which he emphatically appealed to Germany and other European Union countries for closer economic and political integration and coordination, to be achieved through a more powerful central government of the Union. Sikorski feels that decisive action and substantial reform, led by Germany, are necessary to prevent a collapse of the euro and subsequent destabilization and possible demise of the European Union. His remarks, directed primarily at the German audience, encountered hostile reception in Poland from Jarosław Kaczyński and his conservative parliamentary opposition

, who accused the minister of betraying Poland's sovereignty and demanded his ouster and trial. Sikorski specified in his speech several areas important to Polish traditionalists, which, he said, should permanently remain within the competence of individual national governments.

Other:

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

is rooted in the arrival of the Slavs

Poland in the Early Middle Ages

The ancient Roman scholars new nothing about the impenetrable forest north of Dacia and the Carpathian Mountains, between the migrating Celts and Germanic tribes to the west, and the Sarmatians to the east. Augustian historian Strabo only assumed the presence of a different tribe reaching north to...

, who gave rise to permanent settlement and historic development on Polish lands. During the Piast dynasty

Piast dynasty

The Piast dynasty was the first historical ruling dynasty of Poland. It began with the semi-legendary Piast Kołodziej . The first historical ruler was Duke Mieszko I . The Piasts' royal rule in Poland ended in 1370 with the death of king Casimir the Great...

Christianity

Western Christianity

Western Christianity is a term used to include the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church and groups historically derivative thereof, including the churches of the Anglican and Protestant traditions, which share common attributes that can be traced back to their medieval heritage...

was adopted

Baptism of Poland

The Baptism of Poland was the event in 966 that signified the beginning of the Christianization of Poland, commencing with the baptism of Mieszko I, who was the first ruler of the Polish state. The next significant step in Poland's adoption of Christianity was the establishment of various...

in 966 and medieval monarchy

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages was the period of European history around the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries . The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which by convention end around 1500....

established. The Jagiellon dynasty

Jagiellon dynasty

The Jagiellonian dynasty was a royal dynasty originating from the Lithuanian House of Gediminas dynasty that reigned in Central European countries between the 14th and 16th century...

period brought close ties with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Grand Duchy of Lithuania

The Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a European state from the 12th /13th century until 1569 and then as a constituent part of Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth until 1791 when Constitution of May 3, 1791 abolished it in favor of unitary state. It was founded by the Lithuanians, one of the polytheistic...

, cultural development

Renaissance in Poland

The Renaissance in Poland lasted from the late 15th to the late 16th century and is widely considered to have been the Golden Age of Polish culture. Ruled by the Jagiellon dynasty, the Kingdom of Poland actively participated in the broad European Renaissance...

and territorial expansion, culminating in the establishment of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569.

The Commonwealth in its early phase constituted a continuation of the Jagiellon prosperity. From the mid-17th century, the huge state entered a period of decline caused by devastating wars and deterioration of the country's system of government

Golden Liberty

Golden Liberty , sometimes referred to as Golden Freedoms, Nobles' Democracy or Nobles' Commonwealth refers to a unique aristocratic political system in the Kingdom of Poland and later, after the Union of Lublin , in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth...

. Significant internal reforms

Constitution of May 3, 1791

The Constitution of May 3, 1791 was adopted as a "Government Act" on that date by the Sejm of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Historian Norman Davies calls it "the first constitution of its type in Europe"; other scholars also refer to it as the world's second oldest constitution...

were introduced during the later part of the 18th century, but the reform process was not allowed to run its course, as the Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

, the Kingdom of Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

and the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy

Habsburg Monarchy

The Habsburg Monarchy covered the territories ruled by the junior Austrian branch of the House of Habsburg , and then by the successor House of Habsburg-Lorraine , between 1526 and 1867/1918. The Imperial capital was Vienna, except from 1583 to 1611, when it was moved to Prague...

through a series of invasions and partitions

Partitions of Poland

The Partitions of Poland or Partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth took place in the second half of the 18th century and ended the existence of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the elimination of sovereign Poland for 123 years...

terminated the Commonwealth's independent existence in 1795.

From then until 1918 there was no independent Polish state. The Poles had engaged intermittently in armed resistance until 1864. After the failure of the last uprising

January Uprising

The January Uprising was an uprising in the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth against the Russian Empire...

, the nation preserved its identity through educational uplift and the program called "organic work

Organic work

Organic work is a term coined by 19th century Polish positivists, denoting an ideology demanding that the vital powers of the nation be spent on labour rather than fruitless national uprisings. The basic principles of the organic work included education of the masses and increase of the economical...

" to modernize the economy and society. The opportunity for freedom appeared only after World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, when the partitioning imperial powers were defeated by war and revolution.

The Second Polish Republic

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

was established and existed from 1918 to 1939. It was destroyed by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

by their Invasion of Poland at the beginning of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. Millions of Polish citizens perished in the course of the Nazi occupation. The Polish government in exile

Polish government in Exile

The Polish government-in-exile, formally known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in Exile , was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which...

kept functioning and through the many Polish military formations on the western

Western Front (World War II)

The Western Front of the European Theatre of World War II encompassed, Denmark, Norway, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands, France, and West Germany. The Western Front was marked by two phases of large-scale ground combat operations...

and eastern

Eastern Front (World War II)

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of World War II between the European Axis powers and co-belligerent Finland against the Soviet Union, Poland, and some other Allies which encompassed Northern, Southern and Eastern Europe from 22 June 1941 to 9 May 1945...

fronts the Poles contributed

Polish contribution to World War II

The European theater of World War II opened with the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. The Polish Army was defeated after over a month of fighting. After Poland had been overrun, a government-in-exile , armed forces, and an intelligence service were established outside of Poland....

to the Allied

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

victory. Nazi Germany's forces were compelled to retreat from Poland as the Soviet Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

advanced, which led to the creation of the People's Republic of Poland

People's Republic of Poland