.gif)

Prussian Union (Evangelical Christian Church)

Encyclopedia

The Prussian Union was the merger of the Lutheran Church and the Reformed

(Calvinist) Church in Prussia

, by a series of decrees – among them the Unionsurkunde – by King Frederick William III

. The church body

, which in 1817 emerged by the Union was the biggest independent religious organisation in Weimar Germany

with about 18 million enrolled parishioners. Oppressions and interferences by various governments caused the church body to undergo two schisms

(one permanent since the 1830s, one temporary 1934–1948) – including the persecution of many parishioners. In the 1920s during the Weimar Republic and again during the New Left

Movement of the 1960s/1970s some Federal Republic of Germany Stadt or state governments ignored legal precedent and Constitutional law

without consequences by eliminating Congregational control over Church property. These states forcibly imposed permanent or temporary organisational divisions, eliminated entire congregations, and transfered church property to various "government authorized" churches. In the course of the Second World War the church underwent massive destructions of its structures by Precision day-light bombing by the United States Air Force in a still unexplained aerial campaign. More destructively, the church's structure, buildings, and congregations were destroyed in the Genocide

of the community by Communist Soviet Red Army forces which looted, pillaged, raped, and burned the church to the ground. By the end of World War II, the Church would included the the plurality of the populace in the Latvia

, Luthuania, and Estonia

, and the vast majority of the people in East Prussia

, Silesia

, and Pomerania

, and Brandenburg

, were Ethnically cleansed, invading Soviet forces and later Communist Poland. In fact, the war complete ecclesiastical provinces vanished following the expulsion

of most parishioners living east of the Oder-Neiße line. As a result of these three successive persecutions, Germany's primary Protestant Movement was effectively nuetralized and suffered more damage and casualties than anytime since the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

Additionally, under pressure from the government, the Church was forced to recognize various New Left

programs ranging from the Feminist Movement

to Gay Liberation

and Women Priests. However, the Church itself undertook the reform of more parishioners' democratic participation as a result of the successful co-option of some important Church leadership by first the Weimar Republic, then the Nazi Germany

government, and later the German Democratic Republic

government. In theology the church counted many renowned persons as its members – such as Friedrich Schleiermacher

, Julius Wellhausen

(temporarily), Adolf von Harnack

, Karl Barth

(temporarily), Dietrich Bonhoeffer

, or Martin Niemöller

(temporarily), to name only a few. In the early 1950s the church body was transformed into an umbrella, after its prior ecclesiastical provinces had assumed independence in the late 1940s under pressure of the Holy See of Rome, the U.S. Occupation Zone government, and the Soviet Union

.

Today, because of the successful crushing of the Protestant Reformation by these outside forces and the subsequent decline of the number of parishioners due to the German demographic crisis and growing irreligionism, the church body merged in the Union of Evangelical Churches

in 2003. Many changes in the history of the church are reflected in several name changes. The simultaneously created Christian denomination of the Prussian Union exists until this very day and the following church bodies cling to it:

One year after he ascended to the throne in 1798, Frederick William III, being summus episcopus (Supreme Governor of the Protestant Churches), decreed a new common liturgical agenda (service book) to be published, for use in both the Lutheran and Reformed congregations. To accomplish this, a commission to prepare this common agenda was formed. This liturgical agenda was the culmination of the efforts of his predecessors to unify these two Protestant churches in Prussia and in its predecessor, the Electorate of Brandenburg, becoming later its core province.

One year after he ascended to the throne in 1798, Frederick William III, being summus episcopus (Supreme Governor of the Protestant Churches), decreed a new common liturgical agenda (service book) to be published, for use in both the Lutheran and Reformed congregations. To accomplish this, a commission to prepare this common agenda was formed. This liturgical agenda was the culmination of the efforts of his predecessors to unify these two Protestant churches in Prussia and in its predecessor, the Electorate of Brandenburg, becoming later its core province.

The two Protestant churches had existed parallelly after Prince-Elector John Sigismund

declared his conversion from Lutheranism

to Calvinism

in 1617, with most of his subjects remaining Lutheran. However, a significant Calvinist minority had grown due to the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Protestant Calvinist fleed the genocide of their communities by the Catholic Counter-Reformation from Bohemia

, France (Huguenots), the Low Countries

, and Wallonia or migrants from Juliers-Cleves-Berg, the Netherlands

, Poland, or Switzerland

. Their descendants made up the bulk of the Calvinists in Brandenburg.

Major reforms to the administration of Prussia were undertaken after the defeat by Napoléon

's army at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt

. As a part of these reforms, the separate leadership structure of both the Lutheran and the Reformed Churches was abolished by a joint synod of the two Churches and the subsequent approval of the Prussian Estates General. In 1808 the Reformed Friedrich Schleiermacher

, pastor of Trinity Church (Berlin-Friedrichstadt)

, issued his ideas for a constitutional reform of the Protestant Churches, also proposing a union.

Under the influence of the centralizing movement of Absolutism

and the Napoleonic Age, in 1815, rather than re-establishment of the previous confessional leadership structure, all religious communities were placed under a single consistory

in each Prussian province

. This differed from the old structure in that the new leadership administered the affairs of all faiths; Catholics, Jews, Lutherans, Mennonite

s, Moravians, and the Calvinists (Reformed Christians).

In 1814 the Principality of Neuchâtel had been restituted to the Berlin-based Hohenzollern, who had ruled it in personal union

from 1707 until 1806. In 1815 Frederick William III agreed that this French-speaking territory of his joined the Swiss Confederation (then not yet an integrated federation, but a mere confederacy

) as Canton of Neuchâtel

. The church body of the prevailingly Calvinist Neuchâtelians did not rank as state church

but was independent, since at the time of its foundation in 1540, the ruling princely House of Orléans-Longueville (Valois-Dunois) was Catholic. Furthermore no Lutheran congregation existed in Neuchâtel. Thus the Église réformée évangélique du canton de Neuchâtel was not object of Frederick William's Union policy.

On 27 September 1817, Frederick William announced that on the 300th anniversary of the Reformation

Potsdam

's Reformed court and garrison congregation, led by Court Preacher Rulemann Friedrich Eylert, and the Lutheran garrison congregation, both using the Calvinist Garrison Church

would unite into one Evangelical Christian congregation on Reformation Day

, 31 October. Frederick William expressed his desire to see the Protestant congregations around Prussia follow this example, and become Union congregations. Whereas, in previous centuries the two denominations of Calvinist and Lutheran churchs had their own ecclesiastical governments in parallel with the state, and were only under the State through the crown as Supreme Governor, under the new absolutism then in vogue, the Churches were under a civil bureaucratic state supervision through the newly created Prussian Ministry of Religious, Educational and Medical Affairs . The Churches only acquiesced to this supervision in consideration for retaining their separate house in the Parliamentary government having an equal voice in appointment of the head of ministry. Subsequently, Karl vom Stein zum Altenstein

was appointed as minister. However, because of the unique congregation role of the Protestant reformation, no congregation was forced by the King's decree into merger. Thus, in the years that followed, many Lutheran and Reformed congregations did follow the example of Potsdam, and became single merged congregations, while others maintained their former Lutheran or Reformed denomination.

A number of steps were taken to effect the number of pastors that would become Union pastors. Candidates for ministry, from 1820 onwards were required to state whether they would be willing to join the Union. All of the theological

faculty at the Rhenish Frederick William's University in Bonn belonged to the Union. Also an ecumenical

ordination

vow was formulated in which the pastor avowed allegiance to the Evangelical Church.

, to a point where the Real Presence

was not proclaimed. More importantly, the increasing coercion of the civil authorities into Church affairs was viewed as a new threat to Protestant freedom of a kind not seen since the Papacy.

In 1822 the Protestant congregations were directed to use only the newly formulated agenda for worship

. This met with strong objections from Lutheran pastors around Prussia. Despite the opposition, 5,343 out of 7,782 Protestant congregations were using the new agenda by 1825. Frederick William III took notice of Daniel Amadeus Gottlieb Neander , who had only become his subject by the annexation of Royal Saxon

territory in 1816, and who helped the king to implement the agenda in his Lutheran congregations. In 1823 the king made him the Provost

of St. Petri Church (then the highest ranking ecclesiastical office in Berlin) and an Oberkonsistorialrat (supreme consistorial councillor) and thus a member of the March of Brandenburg consistory. He became an influential confidant of the king and one of his privy councillors and a referee to Minister vom Stein zum Altenstein. With the reintroduction of the ecclesiastical function of general superintendents

in 1828, Neander was appointed first General Superintendent of Kurmark

(1829–1853). Thus Neander fought in three fields for the new agenda, on the governmental level, within the church and in the general public, by publications such as Luther in Beziehung auf die evangelische Kirchen-Agende in den Königlich Preussischen Landen (1827). In 1830 the king bestowed him the very unusual, and merely honorary title of bishop. The king also bestowed other collaborators in implementing the Union, with the honorary title of bishop, such as Eylert (1824), Johann Heinrich Bernhard Dräseke (1832), and Wilhelm Ross (1836).

Debate and opposition to the new agenda persisted until 1829, when a revised edition of the agenda was produced. This liturgy incorporated a greater level of elements from the Lutheran liturgical tradition. With this introduction, the dissent against the agenda was greatly reduced. However, a significant minority felt this was merely a temporary political compromise with which the king could continue his ongoing campaign to establish a civil authority over their Freedom of conscious.

In June 1829 Frederick William ordered that all Protestant congregations and clergy in Prussia give up the names Lutheran or Reformed and take up the name Evangelical. The decree was not to enforce a change of belief or denomination, but was only a change of nomenclature. Subsequently the term Evangelical became the usual general expression for Protestant in German language. In April 1830 Frederick William, in his instructions for the upcoming celebration of the 300th anniversary of the presentation of the Augsburg Confession

, ordered all Protestant congregations in Prussia to celebrate the Lord's Supper

using the new agenda. Rather than having the unifying effect that Frederick William desired, the decree created a great deal of dissent amongst Lutheran congregations. In 1830 Johann Gottfried Scheibel

, professor of theology at the Silesian Frederick William's University, founded in Breslau the first Lutheran congregation in Prussia, independent of the Union and outside of its umbrella organisation Evangelical Church in Prussia.

In a compromise with some dissenters, who had now earned the name Old Lutherans

, in 1834 Frederick William issued a decree, which stated that Union would only be in the areas of governance, and in the liturgical agenda, and that the respective congregations could retain their denominational identities. However, in a bid to quell future dissensions of his "Union", in addition to this, dissenters were forbidden from organising sectarian groups.

In defiance of this decree, a number of Lutheran pastors and congregations – like that in Breslau -, believing to act against the Will of God

by obeying the king's decree, continued to use the old liturgical agenda and sacramental rites of the Lutheran church. Becoming aware of this defiance, officials sought out those who acted against the decree. Pastors, who were caught, were suspended from their ministry. If suspended pastors were caught acting in a pastoral role, they were imprisoned. Having now shown his hand as a tyrant bent on oppressing their religious freedom, and under continual police surveillance, the Christian churches began disintergrating.

, today the second largest Lutheran denomination in the U.S. The former emigration led to the eventual creation of the Lutheran Church of Australia

(which was formed in 1966).

With the death of Frederick William III in 1840, King Frederick William IV ascended to the throne. He released the pastors who had been imprisoned, and allowed the dissenting groups to form religious organisations in freedom. In 1841 the Old Lutherans, who had stayed in Prussia, convened in a general synod

in Breslau and founded the Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Prussia, which merged in 1972 with Old Lutheran church bodies in other German states to become today's Independent Evangelical-Lutheran Church

. On 23 July 1845 the royal government recognised the Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Prussia and its congregations as legal entities. In the same year the Evangelical Church in Prussia reinforced its self-conception as the Prussian State's church and renamed into Evangelical State Church in Prussia .

and Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen

, ruled by Catholic princely branches of the Hohenzollern family, joined the Kingdom of Prussia

and became the Province of Hohenzollern

. There had hardly been any Protestants in the tiny area, but with the support from Berlin congregational structures were built up. Until 1874 three (later altogether five) congregations were founded and in 1889 organised as a deanery

of its own. The congregations were stewarded by the Evangelical Supreme Church Council (see below) like congregations of expatriates abroad. Only on 1 January 1899 the congregations became an integral part of the Prussian state church. No separate ecclesiastical province was established, but the deanery was supervised by that of the Rhineland. In 1866 Prussia annexed the Kingdom of Hanover

(then converted into the Province of Hanover

), the Free City of Frankfurt upon Main

, the Electorate of Hesse, and the Duchy of Nassau (combined as Province of Hesse-Nassau

) as well as the Duchies of Schleswig and Holstein (becoming the Province of Schleswig-Holstein

), all prevailingly Lutheran territories, where Lutherans and the minority of Calvinists had not united. After the trouble with the Old Lutherans in pre-1866 Prussia, the Prussian government refrained from imposing the Prussian Union onto the church bodies in these territories. Also the reconciliation of the Lutheran majority of the citizens in the annexed states with their new Prussian citizenship was not to be further complicated by religious quarrels. Thus the Protestant organisations in the annexed territories maintained their prior constitutions or developed new, independent Lutheran or Calvinist structures.

At the instigation of Frederick William IV the Anglican Church of England

At the instigation of Frederick William IV the Anglican Church of England

and the Evangelical Church in Prussia founded the Anglican-Evangelical Bishopric in Jerusalem

(1841–1886). Its bishops and clergy proselytised in the Holy Land

among the non-Muslim native population and German immigrants, such as the Templers

. But also Calvinist, Evangelical and Lutheran expatriates from Germany and Switzerland, living in the Holy Land, joined the German-speaking congregations.

So a number of congregations of Arabic and German language emerged in Beit Jalla (Ar.), Beit Sahour

So a number of congregations of Arabic and German language emerged in Beit Jalla (Ar.), Beit Sahour

(Ar.), Bethlehem of Judea

(Ar.), German Colony (Haifa) (Ger.), American Colony (Jaffa) (Ger.), Jerusalem (Ar. a. Ger.), Nazareth

(Ar.), and Waldheim

(Ger.). With financial aid from Prussia, other German states, the Association of Jerusalem , the Evangelical Association for the Construction of Churches , and others a number of churches and other premises were built. But there were also congregations of emigrants and expatriates in other areas of the Ottoman Empire

(2), as well as in Argentina

(3), Brasil (10), Bulgaria

(1), Chile

(3), Egypt

(2), Italy

(2), the Netherlands

(2), Portugal

(1), Romania

(8), Serbia

(1), Spain (1), Switzerland

(1), United Kingdom

(5), and Uruguay

(1) and the foreign department of the Evangelical Supreme Church Council (see below) stewarded them.

The Evangelical State Church in Prussia stayed abreast of the changes and renamed in 1875 into Evangelical State Church of Prussia's older Provinces . Its central bodies were the executive Evangelical Supreme Church Council , seated in Jebensstraße # 3 (Berlin, 1912–2003) and the legislative General Synod , consisting of representatives of the clergy, the parishioners and members nominated by the king.

The Evangelical State Church in Prussia stayed abreast of the changes and renamed in 1875 into Evangelical State Church of Prussia's older Provinces . Its central bodies were the executive Evangelical Supreme Church Council , seated in Jebensstraße # 3 (Berlin, 1912–2003) and the legislative General Synod , consisting of representatives of the clergy, the parishioners and members nominated by the king.

The Evangelical State Church of Prussia's older Provinces had substructures, called ecclesiastical province , in the nine pre-1866 political provinces of Prussia, to wit in the Province of East Prussia

The Evangelical State Church of Prussia's older Provinces had substructures, called ecclesiastical province , in the nine pre-1866 political provinces of Prussia, to wit in the Province of East Prussia

(homonymous ecclesiastical province), in Berlin, which had become a separate Prussian administrative unit in 1881, and the Province of Brandenburg

(Ecclesiastical Province of the March of Brandenburg for both), in the Province of Pomerania (homonymous), in the Province of Posen

(homonymous), in the Rhine Province

and since 1899 in the Province of Hohenzollern

(Ecclesiastical Province of the Rhineland), in the Province of Saxony

(homonymous), in the Province of Silesia

(homonymous), in the Province of Westphalia

(homonymous), and in the Province of West Prussia (homonymous). Every ecclesiastical province had a provincial synod (representing the provincial parishioners and clergy), and one consistory

(or more), led by general superintendents

(Gen.-Supt.). The ecclesiastical provinces of Saxony, Silesia and Pomerania had two, that of the March of Brandenburg, three – from 1911 to 1933 even four – general superintendents, annually alternating in the leadership of the respective consistory.

The two western provinces, Rhineland and Westphalia, had the strongest Calvinist background, since they were including the territories of the former Duchies of Berg, Cleves

, Juliers

and the Counties of Mark, Tecklenburg, the Siegerland

, and the Principality of Wittgenstein

, all of which had Calvinist traditions. Already in 1835 the provincial church constitutions provided for a general superintendent and congregations in both ecclesiastical provinces with presbyteries of elected presbyters. While in the other Prussian provinces this level of parishioners' democracy only emerged in 1874, when Otto von Bismarck

, in his second term as Prussian Minister-President (9 November 1873 – 20 March 1890), gained the parliamentary support of the National Liberals

in the Prussian State Diet . Prussia's then minister of education and religious affairs, Adalbert Falk, put the bill through, which extended the combined Rhenish and Westphalian presbyterial and consistorial church constitution to all the Evangelical State Church in Prussia. Therefore the terminology is differing: In the Rhineland and Westphalia a presbytery is called in , a member thereof is a Presbyter, while in the other provinces the corresponding terms are Gemeindekirchenrat (congregation council) with its members being called Älteste (elder).

Authoritarian traditions competed with liberal and modern ones. Committed congregants formed parties, which nominated candidates for the elections of the parochial presbyteries and of the provincial or church-wide general synods. A strong party were the Konfessionellen (the denominationals), representing congregants of Lutheran tradition, who had succumbed in the process of uniting the denominations after 1817 and still fought the Prussian Union. They promoted Neo-Lutheranism

and strictly opposed the liberal stream of Kulturprotestantismus , promoting rationalism and a reconcialition of belief and modern knowledge, advocated by Deutscher Protestantenverein

. A third party was the anti-liberal Volkskirchlich-Evangelische Vereinigung (VEV, est. in the mid-19th c., People's Church-Evangelical Association), colloquially Middle party , affirming the Prussian Union, criticising the Higher criticism in Biblical science, but still claiming the freedom of science also in theology

. By far the most successful party in church elections was the anti-liberal Positive Union, being in common sense with the Konfessionellen in many fields, but affirming the Prussian Union. Therefore the Positive Union often formed coalitions with the Konfessionellen. King William I of Prussia sided with the Positive Union. Before 1918 most consistories and the Evangelical Supreme Church Council were dominated by proponents of the Positive Union. In 1888 King William II of Prussia could only appoint the liberal Adolf von Harnack

as professor of theology at the Frederick William University of Berlin after long public debates and protests by the Evangelical Supreme Church Council.

The ever-growing societal segment of the workers among the Evangelical parishioners had little affinity to the Church, which was dominated in their pastors and functionaries by members of the bourgeoisie and aristocracy. A survey held in early 1924 figured out that in 96 churches in Berlin, Charlottenburg

and Schöneberg

9 to 15% of the parishioners actually attended the services. Congregations in workers' districts, often comprising several ten thousands of parishioners, usually counted hardly more than a hundred congregants in regular services. William II and his wife Augusta Viktoria of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg, who presided the Evangelical Association for the Construction of Churches, often financing church constructions for poor congregations, promoted massive programmes of church constructions especially in workers' districts, but could thus not increase the attraction of the State Church for the workers. However, it earned the queen the nickname Kirchen-Juste. More impetus reached the charitable work of the State Church, which was much carried by the Inner Mission and the diaconal work of deaconesses.

Modern anti-Semitism

, emerging in the 1870-s, with its prominent proponent Heinrich Treitschke and its famous opponent Theodor Mommsen

, a son of a pastor and later Nobel Prize laureate, found also supporters among the proponents of traditional Protestant Anti-Judaism

as promoted by the Prussian court preacher Adolf Stoecker

. The new King William II dismissed him in 1890 for the reason of his political agitation by his anti-Semitic Christian Social Party

, neo-paganism and personal scandals.

The intertwining of most leading clerics and church functionaries with traditional Prussian elites brought about that the State Church considered the First World War as a just war. Pacifists, like Hans Francke (Church of the Holy Cross, Berlin), Walter Nithack-Stahn (William I Memorial Church

, Charlottenburg [a part of today's Berlin]), and Friedrich Siegmund-Schultze

(Evangelical Auferstehungsheim, Friedensstraße No. 60, Berlin) made up a small, but growing minority among the clergy. The State Church supported the issuances of nine series of war bond

s and subscribed iself for war bonds amounting to 41 million marks (ℳ)

.

of 1919 decreed the separation of state and religion. Thus the Evangelical State Church of Prussia's older Provinces reorganised in 1922 under the name Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union . The church did not bear the term State Church within its name any more, taking into account that its congregations now spread over six sovereign states. The new name was after a denomination, not after a state any more. It became a difficult task to maintain the unity of the church, with some of the annexing states being opposed to the fact that church bodies within their borders keep a union with German church organisations.

The territory comprising the Ecclesiastical Province of Posen was now largely Polish, and except of small fringes that of West Prussia had been either seized by Poland

or Danzig

. The trans-Niemen part of East Prussia (Klaipėda Region

) became a League of Nations mandate

as of 10 January 1920 and parts of Prussian Silesia

were either annexed by Czechoslovakia

(Hlučín Region

) or Poland (Polish Silesia

), while four congregations of the Rhenish ecclesiastical province were seized by Belgium

, and many more became part of the Mandatory Saar (League of Nations)

.

The Evangelical congregation in Hlučín

, annexed by Czechoslovakia in 1920, joined thereafter the Silesian Evangelical Church of Augsburg Confession

of Czech Silesia

. The Polish government ordered the disentanglement of the Ecclesiastical Province of Posen of the Evangelical State Church of Prussia's older Provinces – except of its congregations remaining with Germany. The now Polish church body then formed the United Evangelical Church in Poland , which existed separately from the Evangelical-Augsburg Church in Poland

until 1945, when most of the former's congregants fled the approaching Soviet army or were subsequently denaturalised by Poland due to their German native language and expelled (1945–1948). The United Evangelical Church in Poland also incorporated the Evangelical congregations in Pomerellia, ceded by Germany to Poland in February 1920, which prior used to belong to the Ecclesiastical Province of West Prussia, as well as the congregations in Soldau and 32 further East Prussian municipalities, which Germany ceded to Poland on 10 January 1920, prior belonging to the Ecclesiastical Province of East Prussia.

A number of congregations lay in those northern and western parts of the Province of Posen

, which were not annexed by Poland and remained with Germany. They were united with those congregations of the western most area of West Prussia, which remained with Germany, to form the new Posen-West Prussia

n ecclesiastical province. The congregations in the eastern part of West Prussia remaining with Germany, joined the Ecclesiastical Province of East Prussia.

The 24 congregations in Eastern Upper Silesia

, ceded to Poland in 1922, constituted on 6 June 1923 as United Evangelical Church in Polish Upper Silesia . Between 1945 and 1948 it underwent the same fate like the United Evangelical Church in Poland. The congregations in Eupen

, Malmédy

, Neu-Moresnet

, and St. Vith, located in the now Belgian East Cantons, were disentangled from the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union as of 1 October 1922 and joined until 1923/1924 the Union des églises évangéliques protestantes de Belgique, which later transformed into the United Protestant Church in Belgium

. They continued to exist until this very day.

The congregations in the territory seized by the Free City of Danzig

, which prior belonged to the Ecclesiastical Province of West Prussia, transformed into the Regional Synodal Federation of the Free City of Danzig . It remained an ecclesiastical province of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union, since the Danzig Senate (government) did not oppose cross-border church bodies. The Danzig ecclesiastical province also co-operated with the United Evangelical Church in Poland as to the education of pastors, since its Polish theological students of German native language were hindered to study at German universities by restrictive Polish pass regulations.

The congregations in the League of Nations mandate of the Klaipėda Region

continued to belong to the Ecclesiastical Province of East Prussia. When from 10–16 January 1923 neighbouring Lithuania

conquered the mandatory territory and annexed it on 24 January, the situation of the congregations there turned precarious. On 8 May 1924 Lithuania and the mandatory powers France

, Italy

, Japan and the United Kingdom

signed the Klaipėda Convention

, granting autonomy to the inhabitants of the Klaipėda Region. This enabled the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union to sign a contract with the Memel autonomous government

under Viktoras Gailius on 23 July 1925 in order to maintain the affiliation of the congregations with the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union. The Evangelical congregations in the Klaipėda Region were disentangled from the Ecclesiastical Province of East Prussia and formed the Regional Synodal Federation of the Memel Territory (Landessynodalverband Memelgebiet), being ranked an ecclesiastical province directly subordinate to the Evangelical Supreme Church Council with an own consistory in Klaipėda

(est. in 1927), led by a general superintendent (at first F. Gregor, after 1933 O. Obereiniger). On 25 June 1934 the tiny church body of the Oldenburgian

exclave Birkenfeld

merged in the Rhenish ecclesiastical province.

The 1922 constitution of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union included much stronger presbyterial structures

and forms of parishioners' democratic participation in church matters. The parishioners of a congregation elected a presbytery and a congregants' representation . A number of congregations formed a deanery

, holding a deanery synod of synodals elected by the presbyteries. The deanery synodals elected the deanery synodal board , in charge of the ecclesiastical supervision of the congregations in a deanery, which was chaired by a superintendent, appointed by the provincial church council after a proposal of the general superintendent. The parishioners in the congregations elected synodals for their respective provincial synod – a legislative body -, which again elected its governing board the provincial church council, which also included members delegated by the consistory. The consistory was the provincial administrative body, whose members were appointed by the Evangelical Supreme Church Council. Each consistory was chaired by a general superintendent, being the ecclesiastical, and a consistorial president , being the administrative leader. The provincial synods and the provincial church councils elected from their midst the synodals of the general synod, the legislative body of the overall Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union. The general synod elected the church senate , the governing board presided by the praeses

of the general synod, elected by the synodals. Johann Friedrich Winckler held the office of praeses from 1915 until 1933. The church senate appointed the members of the Evangelical Supreme Church Council, the supreme administrative entity, which again appointed the members of the consistories.

. Authoritarian traditions competed with liberal and modern ones. The traditional affinity to the former princely holders of the summepiscopacy often continued. So when in 1926 the leftist parties successfully launched a plebiscite to the effect of the expropriation of the German former regnal houses

without compensation, the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union called up for an abstention from the election, holding up the commandment Thou shalt not steal. Thus the plesbiscite missed the minimum turnout and failed.

A problem was the spiritual vacuum, which emerged after the church stopped being a state church. Otto Dibelius

, since 1925 general superintendent of Kurmark

within the Ecclesiastical Province of the March of Brandenburg, published his book Das Jahrhundert der Kirche (The century of the Church), in which he declared the 20th century to be the era when the Evangelical Church may for the first time develop freely and gain the independence God would have wished for, without the burden and constraints of the state church function. He regarded the role of the church as even the more important, since the state of the Weimar Republic

– in his eyes – would not provide the society with binding norms any more, thus this would be the task of the church. The church would have to stand for the defense of the Christian culture of the Occident. In this respect Dibelius regarded himself as consciously anti-Jewish, explaining in a circular to the pastors in his general superintendency district of Kurmark, "that with all degenerating phenomena of modern civilisation Judaism plays a leading role". His book was one of the most read on church matters in that period.

While this new self-conception helped the activists within the church, the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union could not increase the number of its activists. In Berlin the number of activists made up maybe 60,000 to 80,000 persons of an overall number of parishioners of more than 3 millions within an overall of more than 4 million Berliners. Especially in Berlin the affiliation faded. By the end of the 1920-s still 70% of the dead in Berlin were buried accompanied by an Evangelical ceremony and 90% of the children from Evangelical couples were baptised. But only 40% of the marriages in Berlin chose an Evangelical wedding ceremony. From 1928 to 1932 annually about 50,000 parishioners seceded from the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union.

In the field of church elections committed congregants formed new parties, which nominated candidates for the elections of the presbyteries and synods of different level. In 1919 Christian socialists founded the Covenant of Religious Socialists . As reaction to this politicisation the Evangelisch-unpolitische Liste (EuL, Evangelical unpolitical List) emerged, which ran for mandates besides the traditional Middle Party, Positive Union and another new party, the Jungreformatorische Bewegung (Young Reformatory Movement). Especially in the country-side, there often were no developed church parties, thus activist congregants formed common lists of candidates of many different opinions. In February 1932 Protestant Nazis, above all Wilhelm Kube

(presbyter at the Gethsemane Church

, Berlin, and speaker of the six NSDAP parliamentarians in the Prussian State Diet) initiated the foundation of a new party, the so-called Faith Movement of German Christians

, participating on 12–14 November 1932 for the first time in the elections for presbyters and synodals within the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union and gaining about a third of the seats in presbyteries and synods.

After the system of state churches had disappeared with the monarchies in the German states, the question arose, why the Protestant church bodies within Germany did not merge. Besides the smaller Protestant denominations of the Mennonites, Baptists or Methodists, which were organised crossing state borders along denominational lines, there were 29 (later 28) church bodies organised along territorial borders of German states

or Prussian provinces. All those, covering the territory of former monarchies with a ruling Protestant dynasty, had been state churches until 1918 – except of the Protestant church bodies of territories annexed by Prussia in 1866. Others had been no less territorially defined Protestant minority church bodies within states of Catholic monarchs, where – before 1918 – the Roman Catholic Church played the role of state church.

In fact, a merger was permanently under discussion, but never materialised due to strong regional self-confidence and traditions as well as the denominational fragmentation into Lutheran, Calvinist and United and uniting churches

. Following the Swiss example of 1920, the then 29 territorially defined German Protestant church bodies founded the German Federation of Protestant Churches in 1922, which was no new merged church, but a loose federation of the existing independent church bodies.

by Paul von Hindenburg

on 28 February 1933, hit the right persons. On 20 March 1933 Dachau concentration camp, the first official premise of its kind, was opened, while 150,000 hastily arrested inmates were held in hundreds of spontaneous so-called wild concentration camps, to be gradually evacuated into about 100 new official camps to be opened until the end of 1933.

On 21 March 1933 the newly elected Reichstag

convened in the Evangelical Garrison Church

of Potsdam

, an event commemorated as the Day of Potsdam, and the locally competent Gen.-Supt. Dibelius

held the preach. Dibelius downplayed the boycott against enterprises of Jewish proprietors and such of Gentiles of Jewish descent

in an address for the US radio. Even after this clearly anti-Semitic action he repeated in his circular to the pastors of Kurmark on the occasion of Easter (16 April 1933) his anti-Jewish attitude, giving the same words as in 1928.

The Nazi Reich's government, aiming at streamlining the Protestant churches, recognised the German Christians

as its means to do so. On 4 and 5 April 1933 representatives of the German Christians convened in Berlin and demanded the dismissal of all members of the executive bodies of the 28 Protestant church bodies in Germany. The German Christians demanded their ultimate merger into a uniform German Protestant Church, led according to the Nazi Führerprinzip

by a Reich's Bishop , abolishing all democratic participation of parishioners in presbyteries and synods. The German Christians announced the appointment of a Reich's Bishop for 31 October 1933, the Reformation Day

holiday.

Furthermore the German Christians demanded to purify Protestantism of all Jewish patrimony. Judaism should no longer be regarded a religion, which can be adopted and given up, but a racial category which were genetic. Thus German Christians opposed proselytising among Jews. Protestantism should become a pagan kind heroic pseudo-Nordic religion. Of course the Old Testament

, which includes the Ten Commandments

and the virtue of charity

(taken from the Thorah

, Third Book of Moses

: "Thou shalt not avenge, nor bear any grudge against the children of thy people, but thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself: I am the LORD."), was to be abandoned.

In a mood of an emergency through an impending Nazi takeover functionaries of the then officiating executive bodies of the 28 Protestant church bodies stole a march on the German Christians. Functionaries and activists worked hastily on negotiating between the 28 Protestant church bodies a legally indoubtable unification. On 25 April 1933 three men convened, Hermann Kapler, president of the old-Prussian Evangelical Supreme Church Council – representing United Protestantism -, August Marahrens , state bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Hanover (for the Lutherans), and the Reformed Hermann-Albert Klugkist Hesse, director of the preacher seminary in Wuppertal

, to prepare the constitution of a united church. The Nazi government compelled the negotiators to include its representative, the former army chaplain Ludwig Müller from Königsberg

, a devout German Christian. The plans were to dissolve the German Evangelical Church Federation and the 28 church bodies and to replace them by a uniform Protestant church, to be called the German Evangelical Church .

On 27 May 1933 representatives of the 28 church bodies gathered in Berlin and against a minority, voting for Ludwig Müller, Friedrich von Bodelschwingh

On 27 May 1933 representatives of the 28 church bodies gathered in Berlin and against a minority, voting for Ludwig Müller, Friedrich von Bodelschwingh

, head of the Bethel Institution

and member of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union, was elected Reich's Bishop, a newly created title. The German Christians strictly opposed that election, because Bodelschwingh was not their partisan. Thus the Nazis, who were permanently breaking the law, stepped in, using the streamlined Prussian government, and declared the functionaries had exceeded their authority.

appointed August Jäger as Prussian

State Commissioner for the Prussian ecclesiastical affairs .

This act clearly violated the status of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union as statutory body and subjecting it to Jäger's orders (see Struggle of the Churches

). Bodelschwingh resigned as Reich's Bishop the same day. On 28 June Jäger appointed Müller as new Reich's Bishop and on 6 July as leader of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union, then with 18 million parishioners by far the biggest Protestant church body within Germany, with 41 million Protestants altogether (total population: 62 millions).

Kapler resigned as president of the Evangelical Supreme Church Council, after he had applied for retirement on 3 June, and Gen.-Supt. Wilhelm Haendler (competent for Berlin's suburbia), then presiding the March of Brandenburg Consistory retired for age reasons. Jäger furloughed Martin Albertz

(superintendent of the Spandau

deanery), Dibelius, Max Diestel (superintendent of the Cölln Land I deanery in the southwestern suburbs of Berlin), Emil Karow (general superintendent of Berlin inner city), and Ernst Vits (general superintendent of Lower Lusatia

and the New March), thus decapitating the complete spiritual leadership of the Ecclesiastical Province of the March of Brandenburg.

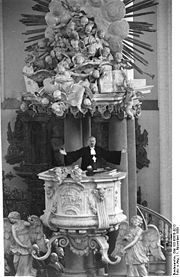

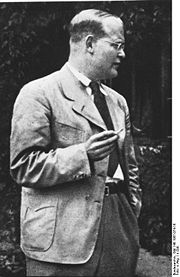

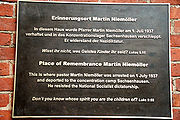

Then the German Christian Dr. iur. Friedrich Werner was appointed as provisional president of the Evangelical Supreme Church Council, which he remained after his official appointment by the re-elected old-Prussian general synod until 1945. For 2 July, Werner ordered general thanksgiving services in all congregations to thank for the new imposed streamlined leadership. Many pastors protested that and held instead services of penance

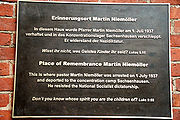

bearing the violation of the church constitution in mind. The pastors Gerhard Jacobi (William I Memorial Church

, Berlin), Fritz (Friedrich) Müller, Martin Niemöller

, Eberhard Röhricht (all the three Dahlem Congregation, Berlin) and Eitel-Friedrich von Rabenau (Apostle Paul Church, Berlin, formerly Immanuel Church (Tel Aviv-Yafo)

, 1912–1917) wrote a letter of protest to Jäger. Pastor Otto Grossmann (Mark's Church, Berlin-Südende, Steglitz Congregation) criticised the violation of the church constitution in a speech on the radio and was subsequently arrested and interrogated (July 1933).

On 11 July German-Christian and intimidated non-such representatives of all the 28 Protestant church bodies in Germany declared the German Evangelical Church Federation to be dissolved and the German Evangelical Church to be founded. On 14 July Hesse, Kapler and Marahrens presented the newly developed constitution of the German Evangelical Church, which the Nazi government declared to be valid. The same day Adolf Hitler

discretionarily decreed an unconstitutional premature re-election of all presbyters and synodals in all 28 church bodies for 23 July. The new synods of the 28 Protestant churches were to declare their dissolution as separate church bodies. Representatives of all 28 Protestant churches were to attend the newly created National Synod to confirm Müller as Reich's Bishop. Müller already now regarded himself as leader of that new organisation. He established an Ecclesiastical Ministry , being the executive body, consisting of four persons, who were not to be elected, but whom he appointed himself.

.

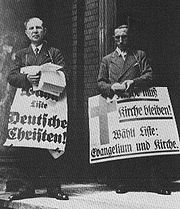

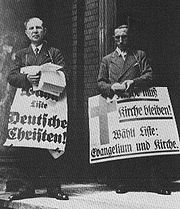

In the campaign for the premature re-election of all presbyters and synodals on 23 July the Nazi Reich's government sided with the German Christians. Under the impression of the government's partiality the other existing lists of opposing candidates united to form the list Evangelical Church. The Gestapo

In the campaign for the premature re-election of all presbyters and synodals on 23 July the Nazi Reich's government sided with the German Christians. Under the impression of the government's partiality the other existing lists of opposing candidates united to form the list Evangelical Church. The Gestapo

(est. 26 April 1933) ordered the list to change its name and to replace all its election posters and flyers issued under the forbidden name. Pastor Wilhelm Harnisch (Good Samaritan Church, Berlin) hosted the opposing list in the office for the homeless of his congregation in Mirbachstraße # 24 (now Bänschstraße # 52).

The Gestapo confiscated the office and the printing-press there, in order to hinder any reprint. Thus the list, which had renamed into Gospel and Church , took refuge with the Evangelical Press Association , presided by Dibelius and printed new election posters in its premises in Alte Jacobstraße # 129, Berlin. The night before the election Hitler appealed on the radio to all Protestants to vote for candidates of the German Christians, while the Nazi Party declared, all its Protestant members were obliged to vote for the German Christians.

The Gestapo confiscated the office and the printing-press there, in order to hinder any reprint. Thus the list, which had renamed into Gospel and Church , took refuge with the Evangelical Press Association , presided by Dibelius and printed new election posters in its premises in Alte Jacobstraße # 129, Berlin. The night before the election Hitler appealed on the radio to all Protestants to vote for candidates of the German Christians, while the Nazi Party declared, all its Protestant members were obliged to vote for the German Christians.

Thus the turnout in the elections was extraordinarily high, since most non-observant Protestants, who since long aligned with the Nazis, had voted. 70–80% of the newly elected presbyters and synodals of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union were candidates of the German Christians. In Berlin e.g., the candidates of Gospel and Church only won the majority in two presbyteries, in Niemöller's Dahlem Congregation, and in the congregation in Berlin-Staaken

-Dorf. In 1933 among the pastors of Berlin, 160 stuck to Gospel and Church, 40 were German Christians while another 200 had taken neither side.

German Christians won a majority within the general synod of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union and within its provincial synods – except of the one of Westphalia

–, as well as in many synods of other Protestant church bodies, except of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria right of the river Rhine

, the Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Hanover, and the Lutheran Evangelical State Church in Württemberg, which the opposition thus regarded as uncorrupted intact churches, as opposed to the other than so-called destroyed churches.

On 24 August 1933 the new synodals convened for a March of Brandenburg provincial synod. They elected a new provincial church council with 8 seats for the German Christians and two for Detlev von Arnim-Kröchlendorff, an esquire owning a manor in Kröchlendorff (a part of today's Nordwestuckermark

), and Gerhard Jacobi (both Gospel and Church). Then the German Christian majority of 113 synodals over 37 nays decided to appeal to the general synod to introduce the so-called Aryan paragraph

as church law, thus demanding that employees of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union – being all baptised Protestant church members -, who had grandparents, who were enrolled as Jews, or who were married with such persons, were all to be fired. Gerhard Jacobi led the opposing provincial synodals. Other provincial synods demanded the Aryan paragraph too.

On 7 April 1933 the Nazi Reich's government had introduced an equivalent law for all state officials and employees. By introducing the Nazi racist attitudes into the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union, the approving synodals betrayed the Christian sacrament of baptism

, according to which this act makes a person a Christian, superseding any other faith, which oneself may have been observing before and knowing nothing about any racial affinity as a prerequisite of being a Christian, let alone one's grandparents' religious affiliation being an obstacle to being Christian.

Rudolf Bultmann

and Hans von Soden, professors of Protestant theology at the Philip's University in Marburg upon Lahn

, wrote in their assessment in 1933, that the Aryan paragraph contradicts the Protestant confession of everybody's right to perform her or his faith freely. "The Gospel is to be universally preached to all peoples and races and makes all baptised persons insegregable brethren to each other. Therefore unequal rights, due to national or racial arguments, are inacceptable as well as any segregation."

On 5 and 6 September the same year the General Synod of the whole Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union convened in the building of the former Prussian State Council (Leipziger Straße No. 3, now seat of the Federal Council (Germany)). Also here the German Christians used their new majority, thus this General Synod became known among the opponents as the Brown Synod, for brown being the colour of the Nazi party.

When on 5 September Karl Koch

, then praeses

of the unadulterated Westphalian provincial synod, tried to bring forward the arguments of the opposition against the Aryan paragraph and the abolition of synodal and presbyterial democracy, the majority of German Christian synodals shouted him down. The German Christians abused the general synod as a mere acclamation, like a Nazi party convention. Koch and his partisans left the synod. The majority of German Christians thus voted in the Aryan paragraph for all the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union. On 5 September the brown synodals passed the retroactive church law, which only established the function and title of bishop. The same law renamed the ecclesiastical provinces into bishoprics , each led – according to the new law of 6 September – by a provincial bishop replacing the prior general superintendents.

By enabling the dismissal of all Protestants of Jewish descent from jobs with the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union, the official church bodies accepted the Nazi racist doctrine of anti-Semitism

. This breach with Christian principles within the range of the church was unacceptable to many church members. Nevertheless, pursuing Martin Luther

's Doctrine of the two kingdoms

(God rules within the world: Directly within the church and in the state by means of the secular government) many church members could not see any basis, how a Protestant church body could interfere with the anti-Semitism performed in the state sphere, since in its self-conception the church body was a religious, not a political organisation. Only few parishioners and clergy, mostly of Reformed tradition, followed Jean Cauvin's doctrine of the Kingdom of Christ within the church and the world.

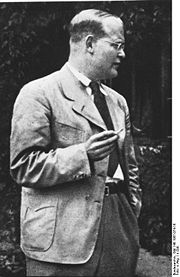

Among them were Karl Barth

and Dietrich Bonhoeffer

, who demanded the church bodies to oppose the abolition of democracy and the unlawfulness in the general political sphere. Especially pastors in the countryside – often younger men, since the traditional pastoral career ladder started in a village parish – were outraged about this development. Herbert Goltzen, Eugen Weschke, and Günter Jacob, three pastors from Lower Lusatia

, regarded the introduction of the Aryan paragraph as the violation of the confession. In late summer 1933 Jacob, pastor in Noßdorf (a part of today's Forst in Lusatia/Baršć), developed the central theses, which became the self-commitment of the opponents.

In reaction to the anti-Semitic discriminations within the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union the church-aligned Breslauer Christliches Wochenblatt (Breslau Christian Weekly) published the following criticism in the October edition of 1933:

"Vision:

Service. The introit faded away. The pastor stands at the altar and begins:

›Non-Aryans are requested to leave the church!‹

Nobody budges.

›Non-Aryans are requested to leave the church!‹

Everything remains still.

›Non-Aryans are requested to leave the church!‹

Then Christ descends from the Crucifix

of the altar and leaves the church."

, and so they did, electing Pastor Niemöller their president. On the basis of the theses of Günter Jacob its members concluded that a schism

was a matter of fact, a new Protestant church was to be established, since the official organisation was anti-Christian, heretical

and therefore illegitimate. Each pastor joining the Covenant – until the end of September 1933 2,036 out of a total of 18,842 Protestant pastors in Germany acceded – had to sign that he rejected the Aryan paragraph.

In 1934 the Covenant counted 7,036 members, after 1935 the number sank to 4,952, among them 374 retired pastors, 529 auxiliary preachers and 116 candidates. First the pastors of Berlin, affiliated with the Covenant, met biweekly in Gerhard Jacobi's private apartment. From 1935 on they convened in the premises of the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) in Wilhelmstraße

No. 24 in Berlin-Kreuzberg

, opposite to the head quarters of Heinrich Himmler

's Sicherheitsdienst

(in 1939 integrated into the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, RSHA) in Wilhelmstraße # 102. In 1941 the Gestapo closed the YMCA house.

On 18 September 1933 Werner was appointed praeses of the old-Prussian general synod, thus becoming president of the church senate. In September Ludwig Müller appointed Joachim Hossenfelder , Reich's leader of the German Christians, as provincial bishop of Brandenburg (resigned in November after the éclat in the Sportpalast, see below), while the then furloughed Karow was newly appointed as provincial bishop of Berlin. Thus the Ecclesiastical Province of the March of Brandenburg, which included Berlin, had two bishops. Karow, being no German Christian, resigned in early 1934 in protest against Ludwig Müller.

On 18 September 1933 Werner was appointed praeses of the old-Prussian general synod, thus becoming president of the church senate. In September Ludwig Müller appointed Joachim Hossenfelder , Reich's leader of the German Christians, as provincial bishop of Brandenburg (resigned in November after the éclat in the Sportpalast, see below), while the then furloughed Karow was newly appointed as provincial bishop of Berlin. Thus the Ecclesiastical Province of the March of Brandenburg, which included Berlin, had two bishops. Karow, being no German Christian, resigned in early 1934 in protest against Ludwig Müller.

On 27 September the pan-German First National Synod convened in the highly symbolic city of Wittenberg

On 27 September the pan-German First National Synod convened in the highly symbolic city of Wittenberg

, where Martin Luther

initiated the Reformation

in 1517. The synodals were not elected by the parishioners, but two thirds were delegated by the church leaders, now called bishops, of the 28 Protestant church bodies, including the three intact ones, and one third were emissaries of Müller's Ecclesiastical Ministry.

Only such synodals were admitted, who would "uncompromisingly stand up any time for the National Socialist state" . The national synod confirmed Müller as Reich's Bishop. The synodals of the national synod decided to waive their right to legislate in church matters and empowered Müller's Ecclesiastical Ministry to act as he wished. Furthermore the national synod usurped the power in the 28 Protestant church bodies and provided the new so-called bishops of the 28 Protestant church bodies with hierarchical supremacy over all clergy and laymen within their church organisation. The national synod abolished future election for the synods of the 28 Protestant church bodies. Henceforth synodals had to replace two thirds of the outgoing synodals by co-optation, the remaining third was to be appointed by the respective bishop.

, led by Hans Meiser , and the Evangelical State Church in Württemberg, presided by Theophil Wurm

, opposed and decided not to merge.

This made also the Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Hanover (the sole Protestant church in Germany using the title of bishop already since 1925, thus prior to Nazi time), with State Bishop August Marahrens, change its mind. But the Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Hanover hesitated to openly confront the Nazi Reich's government, still searching for an understanding even after 1934.

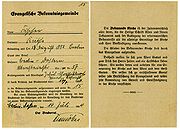

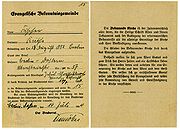

Niemöller, Rabenau and Kurt Scharf

(Congregation in Sachsenhausen (Oranienburg)

) circulated an appeal, calling the pastors up not to fill in the forms, meant to prove their Aryan descent, distributed by the Evangelical Supreme Church Council. Thus its president Werner furloughed the three on 9 November. For more and more purposes Germans had to prove their so-called Aryan descent, which usually was confirmed by copies from the baptismal registers of the churches, certifying that all four grandparents had been baptised. Some pastors soon understood, that people lacking four baptised grandparents are helped a lot – and later even rescued their lives – if they were certified to be Aryan by false copies from the baptismal registers. Pastor Paul Braune (Lobetal, a part of today's Bernau bei Berlin

) issued a memorandum, secretly handed out to pastors of confidence, how to falsify the best. But the majority of pastors in their legalist attitude would not issue false copies.

On 13, 20 November 000 German Christians convened in the Berlin Sportpalast

for a general meeting. Dr. Reinhold Krause, then president of the Greater Berlin section of the German Christians, held a speech, defaming the Old Testament

for its alleged "Jewish morality of rewards" , and demanding the cleansing of the New Testament

from the "scapegoat mentality and theology of inferiority" , whose emergence Krause attributed to the Rabbi (Sha'ul) Paul of Tarsos. Through this speech the German Christians showed their true colours and this opened the eyes of many sympathisers of the German Christians. On 22 November, the Emergency Covenant of Pastors, led by Niemöller, issued a declaration about the heretic belief of the German Christians. On 29 November the Covenant gathered 170 members in Berlin-Dahlem in order to call up Ludwig Müller to resign so that the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union could return into a constitutional condition.

A wave of protest flooded over the German Christians, which ultimately initiated the decline of that movement. On 25 November the complete Bavarian section of the German Christians declared its secession. So Krause was dismissed from his functions with the German Christians and the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union. Krause's dismissal again made the radical Thuringian subsection declare its secession by the end of November. This pushed the complete Faith Movement into crisis so that its Reich's leader Joachim Hossenfelder had to resign on 20 December 1933. The different regional sections then split and united and resplit into half a dozen of movements, entering into a tiresome self-deprecation. Many presbyters of German Christian alignment retired, tired from disputing. So until 1937/1938 many presbyteries in Berlin congregations lost their German Christian majority by mere absenteeism. However the German Christian functionaries on the higher levels mostly remained aboard.

On 4 January 1934 Ludwig Müller, claiming to have by his title as Reich's Bishop legislative power for all Protestant church bodies in Germany, issued the so-called muzzle decree, which forbade any debate about the struggle of the churches within the rooms, bodies and media of the church. The Emergency Covenant of Pastors answered this decree by a declaration read by opposing pastors from their pulpits on 7 and 14 January. Müller then prompted the arrestment or disciplinary procedures against about 60 pastors alone in Berlin, who had been denounced by spies or congregants of German Christian affiliation. The Gestapo tapped Niemöller's phone and thus learned about his and Walter Künneth

's plan to personally plea Hitler for a dismissal of Ludwig Müller. The Gestapo – playing divide et impera – publicised their intention as a conspiracy and so the Lutheran church leaders Marahrens, Meiser, and Wurm distanced themselves from Niemöller on 26 January.

The same day Ludwig Müller decreed the Führerprinzip

, a hierarchy of subordination to command, within the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union. Thus having usurped the power the German Christian Müller forbade his unwelcome competitor as church leader, the German Christian Werner, to discharge his duties as praeses of the Church Senate and president of the Evangelical Supreme Church Council. Werner then sued Müller at the Landgericht I in Berlin. The verdict would have major consequences for the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union. Also opponents, legally consulted by Judge Günther (judge at the Landgericht court), Horst Holstein, Friedrich Justus Perels, and Friedrich Weißler

, covered Ludwig Müller and his willing subordinates with a wave of litigations in the ordinary courts in order to reach verdicts on his arbitrary anticonstitutional measures. Since Müller had acted without legal basis the courts usually proved the litigants to be right.

On 3 February Müller decreed another ordinance to send functionaries against their will into early retirement. Müller thus further cleansed the staff in the consistories, the Evangelical Supreme Church Council and the deaneries from opponents. On 1 March Müller pensioned Niemöller off, the latter and his Dahlem Congregation simply ignored that.

Furthermore Müller degraded the legislative provincial synods and the executive provincial church councils into mere advisory boards. Müller appointed Paul Walzer, formerly county commissioner in the Free City of Danzig, as president of the March of Brandenburg provincial consistory. In the beginning of 1936 Supreme Consistorial Councillor Georg Rapmund, member of the Evangelical Supreme Church Council, succeeded Walzer as consistorial president. After Rapmund's death Supreme Consistorial Councillor Ewald Siebert followed him.

In a series of provincial synods the opposition assumed shape. On 3/4 January 1934 Karl Barth

presided a synod in Wuppertal-Barmen for Reformed parishioners within the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union; on 18/19 February a so-called free synod convened the Rhenish opponents and the Westphalians met at the first Westphalian Synod of Confession on 16 March. On 7 March the so-called free synod for the Ecclesiastical Province of the March of Brandenburg, much influenced by the Reformed pastor Supt. Martin Albertz, elected its first provincial brethren council, comprising Supt. Albertz, Arnim-Kröchlendorff, Wilhelm von Arnim-Lützow, sculpturist Wilhelm Groß, Walter Häfele, Justizrat Willy Hahn, Oberstudienrat Georg Lindner, H. Michael, Willy Praetorius, Rabenau, Scharf, Regierunsgrat Kurt Siehe, and Heinrich Vogel, presided by Gerhard Jacobi.

The Gestapo shut down one office of the provincial brethren council after the other. Werner Zillich and Max Moelter were the executive directors, further collaborators were Elisabeth Möhring (sister of the opposing pastor Gottfried Möhring at St. Catharine's Church in Brandenburg upon Havel) and Senta Maria Klatt (Congregation of St. John's Church, Berlin-Moabit

). The Gestapo summoned her more than 40 times and tried to intimidate her, confronting her with the fact that she, being partly of Jewish descent, would have to realise the worst possible treatment in jail. In the eleven deaneries covering Greater Berlin, six were led by superintendents, who joined the Emergency Covenant of Pastors.

from 29 to 31 May 1934. On 29 May those coming from congregations within the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union held a separate meeting, their later on so-called first old-Prussian Synod of Confession . The old-Prussian synodals elected the Brethren Council of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union, chaired by the Westphalian synodal praeses Karl Koch

, then titled Praeses of the Brethren Council. Further members were Gerhard Jacobi, Niemöller and Fritz Müller.

In the convention, following suit on 30 and 31 May, the participants from all 28 Protestant church bodies in Germany – including the old-Prussian synodals – declared Protestantism were based on the complete Holy Scripture, the Old

and the New Covenant

. The participants declared this basis to be binding for any Protestant Church deserving that name and confessed their allegiance to this basis (see Barmen Theological Declaration

). Henceforth the movement of all Protestant denominations, opposing Nazi adulteration of Protestantism and Nazi intrusion into Protestant church affairs, was called the Confessing Church

, their partisans Confessing Christians, as opposed to German Christians. Later this convention in Barmen used to be called the first Reich's Synod of Confession .

Presbyteries with German Christian majorities often banned Confessing Christians from using church property and even entering the church buildings. Many church employees, who opposed, were dismissed. Especially among the many rural Pietists in the Ecclesiastical Province of Pomerania

the opposition found considerable support. While the German Christians, holding the majority in most official church bodies, lost many supporters, the Confessing Christians, comprising many authentical persuasive activists, still remained a minority but increased their number. As compared to the vast majority of indifferent, non-observing Protestants, both movements were marginal.

One pre-1918 tradition of non-ecclesiastical influence within church structures had made it into the new constitution of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union of 1922. Many of the churches, which had been founded before the 19th c., had a Patron

holding the ius patronatus

, meaning that either the owner of a manor estate

(in the countryside) or a political municipality or city was in charge of maintaining the church buildings and paying the pastor. No pastor could be appointed without the consent of the patron (advowson

). This became a curse and a blessing during the Nazi period. While all political entities were Nazi-streamlined they abused the patronage to appoint Nazi-submissive pastors on the occasion of a vacancy. Also estate owners sometimes sided with the Nazis. But more estate owners were conservative and thus rather backed the opposition in the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union. So the congregations under their patronage could often keep or appoint anew a pastor of the intra-church opposition.

On 9 August 1934 the Second National Synod, with all synodals again admitted by the Ecclesiastical Ministry, severed the uniformation of the formerly independent Protestant church bodies, disenfranchising their respective synods to decide in internal church matters. These pretensions increased the criticism among church members within the streamlined church bodies. On 23 September 1934 Ludwig Müller was inaugurated in a church ceremony as Reich's Bishop.

The Lutheran church bodies of Bavaria right of the river Rhine and Württemberg again refused to merge in September 1934. The imprisonment of their leaders, Bishop Meiser and Bishop Wurm, evoked public protests of congregants in Bavaria right of the river Rhine and Württemberg. Thus the Nazi Reich's government saw, that the German Christians aroused more and more unrest among Protestants, rather driving people into opposition to the government, than domesticating Protestantism as useful beadle for the Nazi reign. A breakthrough was the verdict of 20 November 1934. The court Landgericht I in Berlin

decided that all decisions, taken by Müller since he decreed the Führerprinzip

within the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union on 26 January, the same year, were to be reversed. Thus the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union reconstituted on 20 November 1934. But the prior dismissals of opponents and impositions of loyal German Christians in many church functions were not reversed. Werner regained his authority as president of the Evangelical Supreme Church Council.

In autumn 1934 the Gestapo ordered the closure of the existing free preachers' seminaries, whose attendance formed part of the obligatory theological education of a pastor. The existing Reformed seminary in Wuppertal-Elberfeld, led by Hesse, resisted its closure and was accepted by the Confessing Church, which opened more preachers' seminaries of its own, such as the seminary in Bielefeld

In autumn 1934 the Gestapo ordered the closure of the existing free preachers' seminaries, whose attendance formed part of the obligatory theological education of a pastor. The existing Reformed seminary in Wuppertal-Elberfeld, led by Hesse, resisted its closure and was accepted by the Confessing Church, which opened more preachers' seminaries of its own, such as the seminary in Bielefeld

-Sieker (led by Otto Schmitz), Bloestau (East Prussia) and Jordan in the New March (both led by Hans Joachim Iwand 1935–1937), Naumburg am Queis (Gerhard Gloege), Stettin-Finkenwalde

, later relocated to Groß Schlönwitz and then to Sigurdshof

(forcibly closed in 1940, led by Dietrich Bonhoeffer

). These activities completely depended on donations. In 1937 the Gestapo closed the seminaries in the east. Iwand, on whom in 1936 the Gestapo had inflicted the nationwide prohibition to speak in the public, reopened a seminary in Dortmund

in January 1938. This earned him an imprisonment of four month in the same year.

On 11 October 1934 the Confessing Church established in Achenbachstraße No. 3, Berlin, its own office for the examination of pastors and other church employees, since the official church body discriminated against candidates of Nazi opposing opinion. Until 1945 3,300 theologists graduated at this office. Among their examinators were originally professors of the Frederick William University of Berlin, who refrained from examinating after their employer, the Nazi government, threatened to dismiss them in 1935. After this there were only ecclesiastical examinators, such as Walter Delius (Berlin-Friedrichshagen), Elisabeth Grauer, Günther Harder (Fehrbellin

), Günter Jacob, Fritz Müller, Wilhelm Niesel (auxiliary preacher Wuppertal-Elberfeld

), Susanne Niesel-Pfannschmidt, Barbara Thiele, Bruno Violet (Friedrichswerder Church

, Berlin), and Johannes Zippel (Steglitz Congregation, Berlin). On 1 December 1935 the Confessing Church opened its own Kirchliche Hochschule (KiHo, ecclesiastical college), seated in Berlin-Dahlem and Wuppertal-Elberfeld. The Gestapo forbade the opening ceremony in Dahlem, thus Supt. Albertz spontaneously celebrated it in St. Nicholas' Church (Berlin-Spandau). On 4 December, the Gestapo closed the KiHo altogether, thus the teaching and learning continued underground at changing locations. Among the teachers were Supt. Albertz, Hans Asmussen , Joseph Chambon, Franz Hildebrandt, Niesel, Edo Osterloh, Heinrich Vogel, and Johannes Wolff.

Meanwhile Niemöller and other Confessing Church activists organised the second Reich's Synod of Confession in Berlin's Dahlem Congregation on 19 and 20 October 1934. The synodals elected by all confessing congregations and the congregations of the intact churches decided to found an independent German Evangelical Church. Since the confessing congregations would have to contravene the laws as interpreted by the official church bodies, the synod developed an emergency law of its own. For the destroyed church of the old-Prussian Union they provided for each congregation, taken over by a German Christian majority a so-called brethren council as provisional presbytery, and a Confessing congregation assembly to parallelise the congregants' representation. The Confessing congregations of each deanery formed a Confessing deanery synod , electing a deanery brethren council .

Meanwhile Niemöller and other Confessing Church activists organised the second Reich's Synod of Confession in Berlin's Dahlem Congregation on 19 and 20 October 1934. The synodals elected by all confessing congregations and the congregations of the intact churches decided to found an independent German Evangelical Church. Since the confessing congregations would have to contravene the laws as interpreted by the official church bodies, the synod developed an emergency law of its own. For the destroyed church of the old-Prussian Union they provided for each congregation, taken over by a German Christian majority a so-called brethren council as provisional presbytery, and a Confessing congregation assembly to parallelise the congregants' representation. The Confessing congregations of each deanery formed a Confessing deanery synod , electing a deanery brethren council .

If the superintendent of a deanery clung to the Confessing Church, he was accepted, otherwise a deanery pastor was elected from the midst of the Confessing pastors in the deanery. Confessing congregants elected synodals for a Confessing provincial synod as well as Confessing State synod , who again elected a provincial brethren council or the state brethren council of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union (colloquially old-Prussian brethren council), and a council of the Confessing ecclesiastical province ( of the respective ecclesiastical province) or the council of the Confessing Church of the old-Prussian Union, the respective administrative bodies. Any obedience to the official bodies of the destroyed church of the old-Prussian Union was to be rejected. The Confessing Christians integrated the existing bodies of the opposition – such as the brethren councils of the Emergency Covenant of Pastors, and the independent synods (est. starting in January 1934) -, or established the described parallel structures anew all over the area of the Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union in November 1934.

The rivalling German Evangelical Church of the Confessing Church movement constituted in Dahlem. The synodals elected a Reich's Brethren Council, which elected from its midst the executive Council of the German Evangelical Church, consisting of six.

In Berlin Confessing Christians celebrated the constitution of their church on the occasion of the Reformation Day

In Berlin Confessing Christians celebrated the constitution of their church on the occasion of the Reformation Day

(31 October 1934). The Gestapo forbade them any public event, thus the festivities had to take place in closed rooms with bidden guests only. All the participants had to carry a so-called red card, identifying them as proponents of the Confessing Church. However, 30,000 convened in different convention centres in the city and Niemöller, Peter Petersen (Lichterfelde) and Adolf Kurtz (Twelve Apostles Church) – among others – held speeches. On 7 December the Gestapo forbade the Confessing Church to rent any location, in order to prevent future events like that. The Nazi government then forbade any mentioning of the Kirchenkampf in which media whatsoever.

Hitler was informed about the proceedings in Dahlem and invited the leaders of the three Lutheran intact churches, Marahrens, Meiser and Wurm. He recognised them as legitimate leaders, but expressed that he would not accept the Reich's Brethren Council. This was meant to wedge the Confessing Church along the lines of the uncompromising Confessing Christians, around Niemöller from Dahlem, therefore nicknamed the Dahlemites , and the more moderate Lutheran intact churches and many opposing functionaries and clergy in the destroyed churches, which had not yet been dismissed. For the time being the Confessing Christians found a compromise and appointed – on 22 November – the so-called first Preliminary Church Executive , consisting of Thomas Breit, Wilhelm Flor, Paul Humburg, Koch, and Marahrens. The executive was meant to only represent the Reich's Brethren Council to the outside. But soon Barth, Hesse, Karl Immanuel Immer and Niemöller found the first Preliminary Church Executive to be too compromising so that these Dahlemites resigned from the Reich's Brethren Council.