Albert Kesselring

Encyclopedia

Albert Kesselring was a German Luftwaffe

Generalfeldmarschall

during World War II

. In a military career that spanned both World Wars, Kesselring became one of Nazi Germany

's most skilful commanders, being one of 27 soldiers awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds

. Nicknamed "Smiling Albert" by the Allies

The nickname "Smiling Albert" was bestowed on Kesselring by the Allies. It is not used by German writers. It was used during the war; see and "Uncle Albert" by his troops, he was one of the most popular generals of World War II with the rank and file.

Kesselring joined the Bavarian Army

as an officer cadet

in 1904, and served in the artillery branch. He completed training as a balloon

observer in 1912. During World War I

, he served on both the Western

and Eastern

fronts and was posted to the General Staff

, despite not having attended the War Academy

. Kesselring remained in the Army after the war but was discharged in 1933 to become head of the Department of Administration at the Reich Commissariat for Aviation

, where he was involved in the re-establishment of the aviation industry and the laying of the foundations for the Luftwaffe, serving as its Chief of Staff from 1936 to 1938.

During World War II he commanded air forces in the invasions of Poland

and France

, the Battle of Britain

, and Operation Barbarossa

. As Commander-in-Chief South, he was overall German commander in the Mediterranean theatre

, which included the operations in North Africa

. Kesselring conducted an uncompromising defensive campaign against the Allied forces in Italy

until he was injured in an accident in October 1944. In the final campaign of the war, he commanded German forces on the Western Front. He won the respect of his Allied opponents for his military accomplishments, but his record was marred by massacres committed by troops under his command in Italy.

After the war, Kesselring was tried for war crimes and sentenced to death. The sentence was subsequently commuted to life imprisonment

. A political and media campaign resulted in his release in 1952, ostensibly on health grounds. He was one of only three Generalfeldmarschalls to publish his memoirs, entitled Soldat bis zum letzten Tag (A Soldier to the Last Day).

, Bavaria

, on 30 November 1885, the son of Carl Adolf Kesselring, a schoolmaster and town councillor, and his wife Rosina, who was born a Kesselring, being Carl's second cousin. Albert's early years were spent in Marktsteft, where relatives had operated a brewery since 1688.

Matriculating from the Christian Ernestinum Secondary School in Bayreuth in 1904, Kesselring joined the German Army

as an Fahnenjunker (officer cadet

) in the 2nd Bavarian Foot Artillery Regiment

. The regiment was based at Metz

and was responsible for maintaining its forts. He remained with the regiment until 1915, except for periods at the Military Academy from 1905 to 1906, at the conclusion of which he received his commission as a Leutnant (lieutenant

), and at the School of Artillery and Engineering in Munich

from 1909 to 1910.

Kesselring married Luise Anna Pauline (Liny) Keyssler, the daughter of an apothecary

from Bayreuth, in 1910. The couple honeymoon

ed in Italy

. Their marriage was childless, but in 1913 they adopted Rainer, the son of Albert's second cousin Kurt Kesselring. In 1912, Kesselring completed training as a balloon

observer in a dirigible section – an early sign of an interest in aviation. Kesselring's superiors considered posting him to the School of Artillery and Engineering as an instructor because of his expertise in "the interplay between tactics and technology".

, Kesselring served with his regiment in Lorraine

until the end of 1914, when he was transferred to the 1st Bavarian Foot Artillery

, which formed part of the Sixth Army. On 19 May 1916, he was promoted to Hauptmann

(captain). In 1916 he was transferred again, to the 3rd Bavarian Foot Artillery

. He distinguished himself in the Battle of Arras

, using his tactical acumen to halt a British advance. For his services on the Western Front, he was decorated with the Iron Cross

2nd Class and 1st Class.

In 1917, he was posted to the General Staff

, despite having not attended the War Academy

. He served on the Eastern Front

on the staff of the 1st Bavarian Landwehr Division

. In January 1918, he returned to the Western Front

as a staff officer with the II and III Bavarian Corps.

) of III Bavarian Corps in the Nuremberg

area. A dispute with the leader of the local Freikorps

led to the issuance of an arrest warrant for his alleged involvement in a putsch against the command of III Bavarian Corps and Kesselring was thrown into prison. He was soon released but his superior, Major Hans Seyler, censured him for having "failed to display the requisite discretion".

From 1919 to 1922, Kesselring served as a battery

commander with the 24th Artillery Regiment. He joined the Reichswehr

on 1 October 1922 and was posted to the Military Training Department at the Reichswehr Ministry in Berlin

. He remained at this post until 1929, when he returned to Bavaria as commander of Wehrkreis

VII in Munich

. In his time with the Reichswehr Ministry, Kesselring was involved in the organisation of the army, trimming staff overheads to produce the best possible army with the limited resources available. He helped reorganise the Ordnance Department, laying the groundwork for the research and development

efforts that would produce new weapons. He was involved in secret military manoeuvres held in the Soviet Union

in 1924 and in the so-called Great Plan for a 102-division army, which was prepared in 1923 and 1924. After another brief stint at the Reichswehr Ministry, Kesselring was promoted to Oberstleutnant

(lieutenant colonel

) in 1930 and spent two years in Dresden

with the 4th Artillery Regiment.

Against his wishes, Kesselring was discharged from the army on 1 October 1933 and appointed head of the Department of Administration at the Reich Commissariat for Aviation (Reichskommissariat für die Luftfahrt), the forerunner of the Reich Air Ministry

(Reichsluftfahrtministerium), with the rank of Oberst

(colonel

). Since the Treaty of Versailles

forbade Germany from establishing an air force, this was nominally a civilian agency. The Luftwaffe would formally be established in 1935. As chief of administration, he had to assemble his new staff from scratch. He was involved in the re-establishment of the aviation industry and the construction of secret factories, forging alliances with industrialists and aviation engineers. He was promoted to Generalmajor (major general

) in 1934 and Generalleutnant (lieutenant general

) in 1936. Like other generals of Nazi Germany, he received personal payments from Adolf Hitler

; in Kesselring's case, RM

6,000, a considerable sum at the time.

At the age of 48, he learned to fly. Kesselring believed that first-hand knowledge of all aspects of aviation was crucial to being able to command airmen, although he was well aware that latecomers like himself did not impress the old pioneers or the young aviators. He qualified in various single and multi-engined aircraft and continued flying three or four days per week until March 1945. At times, his flight path took him over the concentration camps at Oranienburg

At the age of 48, he learned to fly. Kesselring believed that first-hand knowledge of all aspects of aviation was crucial to being able to command airmen, although he was well aware that latecomers like himself did not impress the old pioneers or the young aviators. He qualified in various single and multi-engined aircraft and continued flying three or four days per week until March 1945. At times, his flight path took him over the concentration camps at Oranienburg

, Dachau, and Buchenwald

.

Following the death of Generalleutnant Walther Wever

in an air crash, Kesselring became Chief of Staff of the Luftwaffe on 3 June 1936. In that post, Kesselring oversaw the expansion of the Luftwaffe, the acquisition of new aircraft types such as the Messerschmitt Bf 109

and Junkers Ju 87

, and the development of paratroops. Like many ex-Army officers, he tended to see air power in the tactical

role, providing support to land operations. Kesselring and Hans-Jürgen Stumpff

, are usually blamed for the turning away from strategic bombing

and planning while over-focusing on close air support

with the army. However, it would seem the two most prominent enthusiasts for the focus on ground-support operations (direct or indirect) were actually Hugo Sperrle

and Hans Jeschonnek

. These men were long-time professional airmen involved in German air services since early in their careers. The Luftwaffe was not pressured into ground support operations because of pressure from the army, or because it was led by ex-army personnel like Kesselring. Interdiction

and close air support were operations that suited the Luftwaffe's pre-existing approach to warfare; a culture of joint inter-service operations, rather than independent strategic air campaigns. Moreover, many in the Luftwaffe command believed medium bomber

s to be sufficient in power for use in strategic bombing operations against Germany's most likely enemies; Britain and France.

Kesselring's main operational task during this time was the support of the Condor Legion

in the Spanish Civil War

. However, his tenure was marred by personal and professional conflicts with his superior, General der Flieger Erhard Milch

, and Kesselring asked to be relieved. The head of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Göring

, acquiesced and Kesselring became the commander of Air District III in Dresden. On 1 October 1938, he was promoted to General der Flieger

(air general

) and became commander of Luftflotte 1

, based in Berlin.

that began World War II

, Kesselring's Luftflotte 1 operated in support of Army Group North

, commanded by Generaloberst Fedor von Bock

. Although not under von Bock's command, Kesselring worked closely with Bock and considered himself under Bock's orders in all matters pertaining to the ground war. Kesselring strove to provide the best possible close air support

to the ground forces and used the flexibility of air power to concentrate all available air strength at critical points, such as during the Battle of the Bzura

. He attempted to cut the Polish communications by making a series of air attacks against Warsaw

, but found that even 1000 kg (2,204.6 lb) bombs could not guarantee that bridges would be destroyed.

Kesselring was himself shot down over Poland

by the Polish Air Force

. In all, he would be shot down five times during World War II. For his part in the Polish campaign, Kesselring was personally awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

by Adolf Hitler.

network in occupied Poland

. However, after the Mechelen Incident

, in which an aircraft made a forced landing in Belgium

with copies of the German invasion plan, Göring relieved the commander of Luftflotte 2

, General der Flieger Hellmuth Felmy

, of his command, and appointed Kesselring in his place. Kesselring flew to his new headquarters at Münster

the very next day, 13 January 1940. As Felmy's chief of staff, Generalmajor Josef Kammhuber

, had also been relieved, Kesselring brought his own chief of staff, Generalmajor Wilhelm Speidel, with him.

Arriving in the west, Kesselring found Luftflotte 2 operating in support of von Bock's Army Group B

Arriving in the west, Kesselring found Luftflotte 2 operating in support of von Bock's Army Group B

. He inherited from Felmy a complex air plan requiring on-the-minute timing for several hours, incorporating an airborne operation

around Rotterdam

and The Hague

to seize airfields and bridges in the "fortress Holland" area. The paratroopers were General der Flieger Kurt Student

's airborne forces that depended on a quick link up with the mechanised forces. To facilitate this, Kesselring promised von Bock the fullest possible close air support

. Air and ground operations, however, were to commence simultaneously, so there would be no time to suppress the defending Royal Netherlands Air Force

.

The Battle of the Netherlands

commenced on 10 May 1940. While initial air operations went well, and Kesselring's fighters and bombers soon gained the upper hand against the small Dutch air force, the paratroopers ran into fierce opposition in the Battle for The Hague

and the Battle of Rotterdam

. On 14 May 1940, responding to a call for assistance from Student, Kesselring ordered the bombing of Rotterdam

city centre. Fires raged out of control, destroying much of the city.

After the surrender of the Netherlands

on 14 May 1940, Luftflotte 2 attempted to move forward to new airfields in Belgium

while still providing support for the fast moving ground troops. The Battle of France

was going well, with General der Panzertruppe

Heinz Guderian

forcing a crossing of the Meuse River

at Sedan

on 13 May 1940. To support the breakthrough, Kesselring transferred Generalleutnant Wolfram von Richthofen

's VIII. Fliegerkorps

to Luftflotte 3

. By 24 May, the Allied forces had been cut in two, and the German Army was only 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) from Dunkirk, the last channel port remaining in Allied hands. However, that day Generaloberst Gerd von Rundstedt

ordered a halt. Kesselring considered this decision a "fatal error". It left the burden of preventing the Allied evacuation of Dunkirk to Kesselring's fliers, who were hampered by poor flying weather and staunch opposition from the British Royal Air Force

. For his role in the campaign in the west, Kesselring was promoted to Generalfeldmarschall

(field marshal

) on 19 July 1940.

Following the campaign in France, Kesselring's Luftflotte 2 was committed to the Battle of Britain

. Luftflotte 2 was initially responsible for the bombing of southeastern England and the London

area but as the battle progressed, command responsibility shifted, with Generalfeldmarschall Hugo Sperrle

's Luftflotte 3 taking more responsibility for the night-time Blitz attacks while the main daylight operations fell to Luftflotte 2. Kesselring was involved in the planning of numerous raids, including the Coventry Blitz

of November 1940. Kesselring's fliers reported numerous victories, but failed to press home attacks and achieve a decisive victory. Instead, the Luftwaffe employed the inherent flexibility of air power to switch targets.

, Luftflotte 2 remained in the west until May 1941. This was partly as a deception measure, and partly because new airbases in Poland could not be completed by the 1 June 1941 target date, although they were made ready in time for the actual commencement of Operation Barbarossa

on 22 June 1941. Kesselring established his new headquarters at Bielany

, a suburb of Warsaw

.

Luftflotte 2 operated in support of Army Group Centre

, commanded by Fedor von Bock, continuing the close working relationship between the two. Kesselring's mission was to gain air superiority, and if possible air supremacy

, as soon as possible while still supporting ground operations. For this he had a fleet of over 1,000 aircraft, about a third of the Luftwaffes total strength.

The German attack caught large numbers of Soviet Air Force

aircraft on the ground. Faulty tactics – sending unescorted bombers against the Germans at regular intervals in tactically unsound formations – accounted for many more. Kesselring reported that in the first week of operations Luftflotte 2 had accounted for 2,500 Soviet aircraft in the air and on the ground. Even Göring found these figures hard to believe and ordered them to be re-checked. As the ground troops advanced, the figures could be directly confirmed and were found to be too low. Within days, Kesselring was able to fly solo over the front in his Focke-Wulf Fw 189

.

With air supremacy attained, Luftflotte 2 turned to support of ground operations, particularly guarding the flanks of the armoured spearheads, without which the rapid advance was not possible. When enemy counterattacks threatened, Kesselring threw the full weight of his force against them. Now that the Army was convinced of the value of air support, units were all too inclined to call for it. Kesselring now had to convince the Army that air support should be concentrated at critical points. He strove to improve army–air cooperation with new tactics and the appointment of Colonel Martin Fiebig

as a special close air support commander. By 26 July, Kesselring reported the destruction of 165 tanks, 2,136 vehicles and 194 artillery pieces.

In late 1941, Luftflotte 2 supported the final German offensive against Moscow

, codenamed Operation Typhoon

. Raids on Moscow proved hazardous, as Moscow had good all-weather airfields and opposition from both fighters and anti-aircraft guns was similar to that encountered over Britain. The bad weather that hampered ground operations from October on impeded air operations even more. Nonetheless, Luftflotte 2 continued to fly critical reconnaissance, interdiction, close air support and air supply missions.

In November 1941, Kesselring was appointed Commander-in-Chief

In November 1941, Kesselring was appointed Commander-in-Chief

South and was transferred to Italy along with his Luftflotte 2 staff, which for the time being also functioned as his Commander-in-Chief South staff. Only in January 1943 did he form his headquarters into a true theatre staff and create a separate staff to control Luftflotte 2. As a theatre commander, he was answerable directly to the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht

(OKW) and commanded ground, naval and air forces, but this was of little importance at first as most German units were under Italian operational control.

Kesselring strove to organise and protect supply convoys in order to get the German-Italian panzer army the resources it needed. He succeeded in establishing local air superiority and neutralising Malta

, which provided a base from which British aircraft and submarines could menace Axis convoys headed for North Africa. Without the vital supplies they carried, particularly fuel, the Axis forces in North Africa could not conduct operations. Through various expedients, Kesselring managed to deliver a greatly increased flow of supplies to Generaloberst Erwin Rommel

's Afrika Korps

in Libya. With his forces thus strengthened, Rommel prepared an attack on the British positions around Gazala, while Kesselring planned Operation Herkules

, an airborne and seaborne attack on Malta with the 185 Airborne Division Folgore

and Ramcke Parachute Brigade

. Kesselring hoped to thereby secure the Axis line of communication

with North Africa.

For the Battle of Gazala

, Rommel divided his command in two, taking personal command of the mobile units of the Deutsches Afrika Korps and Italian XX Motorized Corps, which he led around the southern flank of Lieutenant-General Neil Ritchie

's British Eighth Army

. Rommel left the infantry of the Italian X and XXI Corps under General der Panzertruppe

Ludwig Crüwell

to hold the rest of the Eighth Army in place. This command arrangement went awry on 29 May 1942 when Crüwell was taken prisoner. Lacking an available commander of sufficient seniority, Kesselring assumed personal command of Gruppe Crüwell. Flying his Fieseler Fi 156

Storch to a meeting, Kesselring was fired upon by a British force astride Rommel's line of communications. Kesselring called in an air strike by every available Stuka

and Jabo

. His attack was successful; the British force suffered heavy losses and was forced to pull back.

Kesselring and Rommel had a disagreement over the latter's conduct in the Battle of Bir Hakeim

. Rommel's initial infantry assaults had failed to capture this vital position, the southern pivot of the British Gazala Line, which was held by the 1st Free French brigade

, commanded by General Marie Pierre Koenig

. Rommel had called for air support but had failed to break the position, which Kesselring attributed to faulty coordination between the ground and air attacks. Bir Hakeim was evacuated on 10 June 1942. Kesselring was more impressed with the results of Rommel's successful assault on Tobruk on 21 June, for which Kesselring brought in additional aircraft from Greece and Crete. For his part in the campaign, Kesselring was awarded the Knight's Cross with oak leaves and swords.

In the wake of the victory at Tobruk, Rommel persuaded Hitler to authorise an attack on Egypt instead of Malta, over Kesselring's objections. The parachute troops assembled for Operation Herkules were sent to Rommel. Things went well at first, with Rommel winning the Battle of Mersa Matruh, but just as Kesselring had warned, the logistical difficulties mounted and the result was the disastrous First Battle of El Alamein

In the wake of the victory at Tobruk, Rommel persuaded Hitler to authorise an attack on Egypt instead of Malta, over Kesselring's objections. The parachute troops assembled for Operation Herkules were sent to Rommel. Things went well at first, with Rommel winning the Battle of Mersa Matruh, but just as Kesselring had warned, the logistical difficulties mounted and the result was the disastrous First Battle of El Alamein

, Battle of Alam el Halfa and Second Battle of El Alamein

. Kesselring considered Rommel to be a great general leading fast-moving troops at the corps level of command, but felt that he was too moody and changeable for higher command. For Kesselring, Rommel's nervous breakdown and hospitalisation for depression at the end of the African Campaign only confirmed this.

Kesselring was briefly considered as a possible successor to Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel

as Chief of Staff of the OKW in September 1942, with General der Panzertruppe Friedrich Paulus

replacing Generaloberst Alfred Jodl

as Chief of the Operations Staff at OKW. The consideration demonstrated the high regard in which Kesselring was held by Hitler. Nevertheless, Hitler decided that neither Kesselring nor Paulus could be spared from their current posts. In October 1942, Kesselring was given direct command of all German armed forces in the theatre except Rommel's German-Italian Panzer Army

in North Africa, including General der Infantrie Enno von Rintelen, the German liaison officer at Commando Supremo, who spoke fluent Italian. Kesselring's command also included the troops in Greece and the Balkans until the end of the year, when Hitler created an army group headquarters under Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm List, naming him List Oberbefehlshaber Südost.

precipitated a crisis in Kesselring's command. He ordered Walther Nehring

, the former commander of the Afrika Korps

who was returning to action after recovering from wounds received at the Battle of Alam el Halfa, to proceed to Tunisia

to take command of a new corps (XC Corps). Kesselring ordered Nehring to establish a bridgehead in Tunisia and then to press west as far as possible so as to gain freedom to manoeuvre. By December, the Allied commander, General

Dwight D. Eisenhower

, was forced to concede that Kesselring had won the race; the final phase of Operation Torch

had failed and the Axis could only be ejected from Tunisia after a prolonged struggle.

With the initiative back with the Germans and Italians, Kesselring hoped to launch an offensive that would drive the Allies out of North Africa. At the Battle of the Kasserine Pass

his forces gave the Allies a beating but in the end strong Allied resistance and a string of Axis errors stopped the advance. Kesselring now concentrated on shoring up his forces by moving the required tonnages of supplies from Sicily

but his efforts were frustrated by Allied aircraft and submarines. An Allied offensive in April

finally broke through, leading to a collapse of the Axis position in Tunisia. Some 275,000 German and Italian prisoners were taken. Only the Battle of Stalingrad

overshadowed this disaster. In return, Kesselring had held up the Allies in Tunisia for six months, forcing a postponement of the Allied invasion of northern France from the middle of 1943 to the middle of 1944.

Kesselring expected that the Allies would next invade Sicily

Kesselring expected that the Allies would next invade Sicily

, as a landing could be made there under fighter cover from Tunisia and Malta. He reinforced the six coastal and four mobile Italian divisions there with two mobile German divisions, the 15th Panzergrenadier Division and the Hermann Göring Panzer Division

, both rebuilt after being destroyed in Tunisia. Kesselring was well aware that while this force was large enough to stop the Allies from simply marching in, it could not withstand a large scale invasion. He therefore pinned his hopes on repelling the Allied invasion of Sicily

on an immediate counterattack, which he ordered Colonel Paul Conrath

of the Hermann Göring Panzer Division to carry out the moment the objective of the Allied invasion fleet was known, with or without orders from the island commander, Generale d'Armata Alfredo Guzzoni

.

Kesselring hoped that the Allied invasion fleet would provide good targets for U-boat

s, but they had few successes. U-953 sank two American LSTs and with U-375 sank three vessels from a British convoy on 4–5 July, while U-371 sank a Liberty ship

and a tanker

on 10 July. Pressure from the Allied air forces forced Luftflotte 2, commanded since June by von Richthofen, to withdraw most of its aircraft to the mainland.

The Allied invasion of Sicily on 10 July 1943 was stubbornly opposed. A Stuka attacked and sank the ; an Bf 109 destroyed an LST; and a Liberty ship filled with ammunition was bombed by Ju 88s and caught fire, later exploding without loss of life. Unaware that Guzzoni had already ordered a major counterattack on 11 July, Kesselring bypassed the chain of command to order the Hermann Göring Panzer Division to attack that day in the hope that a vigorous attack could succeed before the Americans could bring the bulk of their artillery and armoured support ashore. Although his troops gave the Americans "quite a battering", they failed to capture the Allied position.

Kesselring flew to Sicily himself on 12 July to survey the situation and decided that no more than a delaying action was possible and that the island would eventually have to be evacuated. Nonetheless, he intended to fight on and he reinforced Sicily with the 29th Panzergrenadier Division on 15 July. Kesselring returned to Sicily by flying boat

on 16 July to give the senior German commander, General der Panzertruppe

Hans-Valentin Hube

, his instructions. Unable to provide much more in the way of air support, Kesselring gave Hube command of the heavy flak units on the island, although this was contrary to Luftwaffe doctrine. In all, Kesselring managed to delay the Allies in Sicily for another month and the Allied conquest of the Sicily was not complete until 17 August.

Kesselring's evacuation of Sicily, which began a week earlier on 10 August, was perhaps the most brilliant action of the campaign. In spite of the Allies' superiority on land, at sea, and in the air, Kesselring was able to evacuate not only 40,000 men, but also 96,605 vehicles, 94 guns, 47 tanks, 1,100 tons of ammunition, 970 tons of fuel, and 15,000 tons of stores. He was able to achieve near-perfect coordination between the three services under his command while his opponent, Eisenhower, could not.

, where his I Parachute Corps was under OKW orders to occupy the capital in case of Italian defection. Benito Mussolini

was removed from power on 25 July 1943 and Rommel and OKW began to plan for the occupation of Italy and the disarmament of the Italian Army. Kesselring remained uninformed of these plans for the time being.

On the advice of Rommel and Generaloberst Alfred Jodl

On the advice of Rommel and Generaloberst Alfred Jodl

, Hitler decided that the Italian Peninsula

could not be held without the assistance of the Italian Army. Kesselring was ordered to withdraw from southern Italy and consolidate his Army Group C with Rommel's Army Group B in Northern Italy, where Rommel would assume overall command. Kesselring was slated to be posted to Norway

. Kesselring was appalled at the prospect of abandoning Italy. It would expose southern Germany to bombers operating from Italy; risk the Allies breaking into the Po Valley; and was completely unnecessary, as he was certain that Rome could be held until the summer of 1944. This assessment was based on his belief that the Allies would not conduct operations outside the range of their air cover, which could only reach as far as Salerno

. Kesselring submitted his resignation on 14 August 1943.

SS

Obergruppenführer

Karl Wolff

, the highest SS and police Führer

in Italy, intervened on Kesselring's behalf with Hitler. Wolff painted Rommel as "politically unreliable" and argued that Kesselring's presence in southern Italy was vital to prevent an early Italian defection. On Wolff's advice, Hitler refused to accept Kesselring's resignation.

Italy withdrew from the war on 8 September. Kesselring immediately moved to secure Rome, where he expected an Allied airborne and seaborne invasion. He ordered the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division and 2nd Parachute Division to close on the city, while a detachment made an unsuccessful attempt to seize the Italian Army staff at Monterotondo

in a coup de main

. Kesselring's two divisions were faced by five Italian divisions, two of them armoured, but he managed to overcome the opposition, disperse the Italian forces and secure the city in two days.

All over Italy, the Germans swiftly disarmed

Italian units. Rommel deported Italian soldiers, except for those willing to serve in German units, to Germany for forced labor, whereas Italian units in Kesselring's area were initially disbanded and their men permitted to go home. One Italian commander, General Gonzaga, refused German demands that his 222nd Coastal Division disarm, and was promptly shot. A significant part of the 184 Airborne Division Nembo

went over to the German side, eventually becoming the basis of the 4th Parachute Division

. On the Greek Island of Kefalonia

– outside Kesselring's command – some 5,000 Italian troops of the 33 Mountain Infantry Division Acqui

were massacred

. Mussolini was rescued by the Germans in Operation Oak (Unternehmen Eiche

), a raid planned by Kurt Student and carried out by Obersturmbannführer

Otto Skorzeny

on 12 September. The details of the operation were deliberately, though unsuccessfully, kept from Kesselring. "Kesselring is too honest for those born traitors down there" was Hitler's assessment.

Italy now effectively became an occupied country, as the Germans poured in troops. Italy's decision to switch sides created contempt for the Italians among both the Allies and Germans, which was to have far-reaching consequences.

Although his command was already "written off", Kesselring intended to fight. At the Battle of Salerno

Although his command was already "written off", Kesselring intended to fight. At the Battle of Salerno

in September 1943, he launched a full-scale counterattack against the Allied landings there with Generaloberst Heinrich von Vietinghoff

's Tenth Army. The counterattack inflicted heavy casualties on the Allied forces, forced them back in several areas, and, for a time, made Allied commanders contemplate evacuation. The short distance from German airfields allowed Luftflotte 2 to put 120 aircraft over the Salerno area on 11 September 1943. Using Fritz X

anti-ship missile

s, hits were scored on the battleship

and cruiser

s and , while a Liberty ship was sunk on 14 September and another damaged the next day. The offensive ultimately failed to throw the Allies back into the sea because of the intervention of Allied naval gunfire which decimated the advancing German units, stubborn Allied resistance and the advance of the British Eighth Army. On 17 September 1943, Kesselring gave Vietinghoff permission to break off the attack and withdraw.

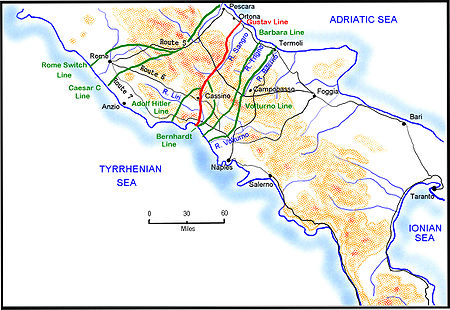

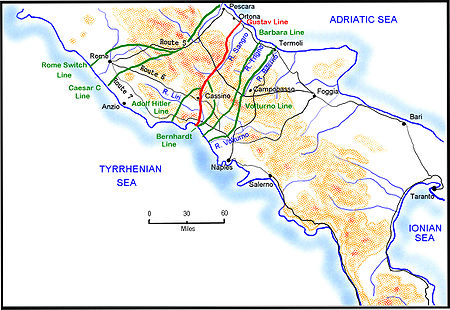

Kesselring had been defeated but gained precious time. Already, in defiance of his orders, he was preparing a series of successive fallback positions on the Volturno Line

, the Barbara Line

and the Bernhardt Line

. Only in November 1943, after a month of hard fighting, did the Allies reach Kesselring's main position, the Gustav Line

. According to his memoirs, Kesselring felt that much more could have been accomplished if he had access to the troops held "uselessly" under Rommel's command.

In November 1943, Kesselring met with Hitler. Kesselring gave an optimistic assessment of the situation in Italy and gave reassurances that he could hold the Allies south of Rome on the Winter Line

. Kesselring further promised that he could prevent the Allies reaching the Northern Apennines

for at least six months. As a result, on 6 November 1943, Hitler ordered Rommel and his Army Group B headquarters to move to France to take charge of the Atlantic Wall

and prepare for the Allied attack that was expected there in the Spring of 1944. On 21 November 1943, Kesselring resumed command of all German forces in Italy, combining Commander-in-Chief South, a joint command, with that of Army Group C, a ground command. "I had always blamed Kesselring", Hitler later explained, "for looking at things too optimistically ... events have proved Rommel wrong, and I have been justified in my decision to leave Field Marshal Kesselring there, whom I have seen as an incredible political idealist, but also as a military optimist, and it is my opinion that military leadership without optimism is not possible."

The Luftwaffe scored a notable success on the night of 2 December 1943 when 105 Ju88 bombers struck the port of Bari

. Skilfully using chaff

to confuse the Allied radar

operators, they found the port packed with brightly lit Allied shipping. The result was the most destructive air raid on Allied shipping since the attack on Pearl Harbor

. Hits were scored on two ammunition ships and a tanker. Burning oil and exploding ammunition spread over the harbour. Some 16 ships were sunk and eight damaged, and the port was put out of action for three weeks. Moreover, one of the ships sunk, SS John Harvey, had been carrying mustard gas, which enveloped the port in a cloud of poisonous vapours.

The first Allied attempt to break through the Gustav Line in the Battle of Monte Cassino

The first Allied attempt to break through the Gustav Line in the Battle of Monte Cassino

in January 1944 met with early success, with the British X Corps

breaking through the line held by the 94th Infantry Division and imperilling the entire Tenth Army front. At the same time, Kesselring was receiving warnings of an imminent Allied amphibious attack. Kesselring rushed his reserves, the 29th and 90th Panzergrenadier Divisions, to the Cassino front. They were able to stabilise the German position there but left Rome poorly guarded. Kesselring felt that he had been out-generalled when the Allies landed at Anzio

.

Although taken by surprise, Kesselring moved rapidly to regain control of the situation, summoning Generaloberst Eberhard von Mackensen

's Fourteenth Army headquarters from northern Italy, the 29th and 90th Panzergrenadier Divisions from the Cassino front, and the 26th Panzer Division from Tenth Army. OKW chipped in some divisions from other theatres. By February, Kesselring was able to take the offensive at Anzio but his forces were unable to crush the Allied beachhead, for which Kesselring blamed himself, OKW and von Mackensen for avoidable errors.

Meanwhile, costly fighting at Monte Cassino

in February 1944 brought the Allies close to a breakthrough into the Liri Valley. To hold the bastion of Monte Cassino, Kesselring brought in the 1st Parachute Division

, an "exceptionally well trained and conditioned" formation, on 26 February. Despite heavy casualties and the expenditure of enormous quantities of ammunition, an Allied offensive in March 1944 failed to break the Gustav Line position.

On 11 May 1944 General Sir Harold Alexander

launched Operation Diadem

, which finally broke through the Gustav Line and forced the Tenth Army to withdraw. In the process, a gap opened up between the Tenth and Fourteenth Armies, threatening both with encirclement. For this failure, Kesselring relieved von Mackensen of his command, replacing him with General der Panzertruppe Joachim Lemelsen

. Fortunately for the Germans, Lieutenant General

Mark Clark

, obsessed with the capture of Rome, failed to take advantage of the situation and the Tenth Army was able to withdraw to the next line of defence, the Trasimene Line

, where it was able to link up with the Fourteenth Army and then conduct a fighting withdrawal.

For his part in the campaign, Kesselring was awarded the Knight's Cross with oak leaves, swords and diamonds by Hitler at the Wolfsschanze

near Rastenburg, East Prussia

on 19 July 1944. The next day, Hitler was the target of the 20 July plot. Informed of this event that evening by Göring, Kesselring, like many other senior commanders, sent a telegram to Hitler reaffirming his loyalty.

Throughout July and August 1944, Kesselring fought a stubborn delaying action, gradually retreating to the formidable Gothic Line

north of Florence

. There, he was finally able to halt the Allied advance. Casualties of the Gothic Line battles in September and October 1944 included Kesselring himself. On 25 October 1944, his car collided with an artillery piece coming out of a side road. Kesselring suffered serious head and facial injuries and did not return to his command until January 1945.

and Orvieto

. In some cases, historic bridges – such as the Ponte Vecchio

(literally "Old Bridge") – were booby trap

ped rather than blown up. However, other historic Florentine bridges were destroyed on his orders and, in addition to booby-trapping the old bridge, he ordered the demolition of the ancient historical central borough at its two ends, in order to delay the Allied advance across the Arno

river. In the same vein, Kesselring supported the Italian declaration of Rome, Florence and Chieti

as open cities

. In the case of Rome, this was in spite of there being considerable tactical advantages to be had from defending the Tiber

bridges. These declarations were never agreed to by the Allies as the cities were not demilitarised and remained centres of government and industry. Despite the repeated declarations of "open city", Rome was bombed more than fifty times by the Allies, whose air forces hit Florence as well. In practice, the open city status was rendered meaningless.Among several relevant documents available at the National Archives of the United Kingdom – all of which clarify beyond any doubt that the "open city" status was never operative in Rome – the , which contains a number of filed documents about the Allied policy towards Rome, is of most interest. The file n. 400 is a message sent to the Foreign Office by D'Arcy Osborne, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Holy See, in which he transmits the latest German proposal for declaring Rome "open city", relayed to him by the German Ambassador in Rome, via the Vatican Undersecretary of State; the message was then urgently retransmitted to Washington, and is dated 4 June 1944, the same day General Mark Clark's tanks entered Rome. Up to the very last minute, the Germans had used Rome and the diplomatic delusion of the never-ending talks about the "open city" in order to take any possible advantage out of it, including using the Italian capital to cover their ordered retreat behind a safer defence line.

Kesselring tried to preserve the monastery of Monte Cassino

by avoiding its military occupation even though it offered a superb observing point over the battlefield. Ultimately this was unsuccessful, as the Allies never believed the monastery would not be used to direct the German artillery against their lines. On the morning of 15 February 1944, 142 B-17 Flying Fortress, 47 B-25 Mitchell

and 40 B-26 Marauder

medium bombers deliberately dropped 1,150 tons of high explosives and incendiary bombs on the abbey, reducing the historic monastery to a smoking mass of rubble. Kesselring was aware that some artworks taken from Monte Cassino for safekeeping wound up in the possession of Hermann Göring. Kesselring had some German soldiers shot for looting. German authorities avoided giving the Italian authorities control over artworks because they feared that "entire collections would be sold to Switzerland". A 1945 Allied investigation reported that Italian cultural treasures had suffered relatively little war damage. Kesselring received regular updates on efforts to preserve cultural treasures and his personal interest in the matter contributed to the high proportion of art treasures that were saved.

(OSS) Operational Group landed in inflatable boat

s from US Navy PT boats on the Liguria

n coast as part of Operation Ginny II, a mission to blow up the entrances of two vital railway tunnels. Their boats were discovered and they were captured by a smaller group of Italian and German soldiers. On 26 March, they were executed under Hitler's "Commando Order

", issued after German soldiers had been shackled during the Dieppe Raid

. General Anton Dostler

, who had signed the execution order, was tried after the war, found guilty, and executed by firing squad on 1 December 1945.

In Rome on 23 March 1944, 33 policemen of the Polizeiregiment Bozen from the German

-speaking population of the Italian province of South Tyrol

and three Italian civilians were killed by a bomb blast and the subsequent shooting. In response, Hitler approved the recommendation of Generaloberst Eberhard von Mackensen

, the commander of the Fourteenth Army who was responsible for the sector including Rome

, that 10 Italians should be shot for each policeman killed. The task fell to SS Obersturmbannführer Herbert Kappler

who, finding there were not enough condemned prisoners available, made up the numbers as he thought best, using Jewish prisoners and even civilians taken from the streets. The result was the Ardeatine massacre

.

The fall of Rome on 4 June 1944 placed Kesselring in a dangerous situation as his forces attempted to withdraw from Rome to the Gothic Line

. That the Germans were especially vulnerable to Italian partisans was not lost on General Alexander, who appealed in a radio broadcast for Italians to kill Germans "wherever you encounter them". Kesselring responded by authorising the "massive employment of artillery, grenade

and mine throwers

, armoured cars, flamethrower

s and other technical combat equipment" against the partisans. He also issued an order promising indemnity to soldiers who "exceed our normal restraint". Whether or not as a result of Kesselring's hard line, massacres were carried out by the Hermann Göring Panzer Division

at Stia

in April, Civitella in Val di Chiana

in June and Bucine in July 1944, by the 26th Panzer Division at Padule di Fucecchio

on 23 August 1944, and by the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division Reichsführer-SS

at Sant'Anna di Stazzema

in August 1944 and Marzabotto

in September and October 1944.

In August 1944 Kesselring was informed by Rudolf Rahn, the German ambassador to the RSI

, that Mussolini had filed protests about the killing of Italian citizens. In response, Kesselring issued another edict to his troops on 21 August, deploring incidents that had "damaged the German Wehrmachts reputation and discipline and which no longer have anything to do with reprisal operations" and launched investigations into specific cases that Mussolini cited. Between 21 July and 25 September 1944, 624 Germans were killed, 993 wounded and 872 missing in partisan operations, while some 9,520 partisans were killed.

Kesselring used the Jews of Rome as slave labour on the construction of fortifications – as he had earlier done with those of Tunis. He needed a large labour force, given the magnitude of the logistical challenges he was facing. When ordered to deport the Roman Jews, Kesselring resisted. He announced that no resources were available to carry out such an order. Hitler then transferred responsibility to the SS and around 8,000 Roman Jews were ultimately deported. During the German occupation of Italy, the Germans were believed to have killed some 46,000 Italian civilians, including 7,000 Jews.

as OB West

on 10 March 1945. On arrival, he told his new staff, "Well, gentlemen, I am the new V-3", referring to the Vergeltungswaffe

("vengeance" weapons) and, in particular, to the V-3 cannon

, prototypes of which were fired on the Western Front

in late 1944 and early 1945. Given the desperate situation of the Western Front, this was another sign of Kesselring's proverbial optimism. Kesselring still described as "lucid" Hitler's analysis of the situation, according to which the Germans were about to inflict a historical defeat upon the Soviets, after which the victorious German armies would be brought west to crush the Allies and sweep them from the continent. Therefore, Kesselring was determined to "hang on" in the west until the "decision in the East" came. Kesselring endorsed Hitler's order that deserters should be hanged from the nearest tree. When a staff officer sought to make Kesselring aware of the hopelessness of the situation, Kesselring told him that he had driven through the entire army rear area and not seen a single hanged man.

The Western Front at this time generally followed the Rhine river with two important exceptions: the American bridgehead over the Rhine at Remagen

, and a large German salient

west of the Rhine, the Saar

–Palatinate triangle. Consideration was given to evacuating the triangle, but OKW ordered it held. When Kesselring paid his first visit to the German First and Seventh Army headquarters there on 13 March 1945, the army group commander, Oberstgruppenführer

Paul Hausser

, and the two army commanders all affirmed the defence of the triangle could only result in heavy losses or complete annihilation of their commands. General der Infanterie Hans Felber

of the Seventh Army considered the latter the most likely outcome. Nonetheless, Kesselring insisted that the positions had to be held.

The triangle was already under attack from two sides by Lieutenant General George Patton's Third Army and Lieutenant General Alexander Patch

's Seventh Army. The German position soon crumbled and Hitler reluctantly sanctioned a withdrawal. The First and Seventh Armies suffered heavy losses: around 113,000 Germans casualties at the cost of 17,000 on the Allied side. Nonetheless, they had avoided encirclement and managed to conduct a skilful delaying action, evacuating the last troops to the east bank of the Rhine on 25 March 1945.

As Germany was cut in two, Kesselring's command was enlarged to include Army Groups Centre

, South

and South-East on the Eastern Front

, and Army Group C in Italy, as well as his own Army Group G

and Army Group Upper Rhine

. On 30 April, Hitler committed suicide in Berlin. On 1 May, Karl Dönitz

was designated German President (Reichspräsident

) and the Flensburg government

was created. One of the new president's first acts was the appointment of Kesselring as Commander-in-Chief of Southern Germany, with plenipotentiary powers.

, Allen Dulles. Known as Operation Sunrise

, these secret negotiations had been in progress since early March 1945. Kesselring was aware of them, having previously consented to them, although he had not informed his own staff. He did, however, later inform Hitler.

At first he did not accept the agreement and, on 30 April, relieved both Vietinghoff and his Chief of Staff, Generalleutnant Hans Röttiger

, putting them at the disposition of the OKW for a possible court martial. They were replaced by General Friedrich Schulz

and Generalmajor Friedrich Wenzel respectively. The next morning, 1 May, Röttinger reacted by placing both Schulz and Wenzel under arrest, and summoning General Joachim Lemelsen

to take Schulz's place. Lemelsen initially refused, as he was in possession of a written order from Kesselring which prohibited any talks with the enemy without his explicit authorization. By this time, Vietinghoff and Wolff had concluded an armistice with the Allied Commander in Chief of the Mediterranean Theatre, Field Marshal

Alexander, which became effective on 2 May at 14:00. Lemelsen reached Bolzano, and Schulz and Wenzel regained control, this time agreeing with the officers pushing for a quick surrender. The German armies in Italy were now utterly defeated by the Allies, who were rapidly advancing from Garmisch towards Innsbruck

. Kesselring remained stubbornly opposed to the surrender, but was finally won over by Wolff on the late morning of 2 May after a two-hour phone call to Kesselring at his headquarters at Pullach

.

North of the Alps, Army Group G followed suit on 6 May. Kesselring now decided to surrender his own headquarters. He ordered SS Oberstgruppenführer

Paul Hausser

to supervise the SS troops to ensure that the surrender was carried out in accordance with his instructions. Kesselring then surrendered to an American major at Saalfelden

, near Salzburg

, in Austria

on 9 May 1945. He was taken to see Major General Maxwell D. Taylor

, the commander of the 101st Airborne Division

, who treated him courteously, allowing him to keep his weapons and field marshal's baton, and to visit the Eastern Front headquarters of Army Groups Centre and South at Zeltweg

and Graz

unescorted. Taylor arranged for Kesselring and his staff to move into a hotel at Berchtesgaden

. Photographs of Taylor and Kesselring drinking tea together created a stir in the United States. Kesselring met with Lieutenant General Jacob L. Devers

, commander of the Sixth United States Army Group, and gave interviews to Allied newspaper reporters.

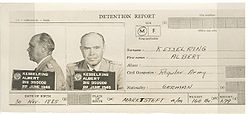

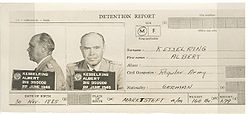

With the end of the war, Kesselring was hoping to be able to make a start on the rehabilitation of Germany. Instead, he found himself placed under arrest. On 15 May 1945, Kesselring was taken to Mondorf-les-Bains

where his baton and decorations were taken from him and he was incarcerated. He was held in a number of American POW camps before being transferred to British custody in 1946. He testified at the Nuremberg trial

of Hermann Göring, but his offers to testify against Soviet, American, and British commanders were declined.

By the end of the war, for many Italians the name of Kesselring, whose signature appeared on posters and printed orders announcing draconian measures adopted by the German occupation, had become synonymous with the oppression and terror that had characterised the German occupation. Kesselring's name headed the list of German officers blamed for a long series of atrocities perpetrated by the German forces.

By the end of the war, for many Italians the name of Kesselring, whose signature appeared on posters and printed orders announcing draconian measures adopted by the German occupation, had become synonymous with the oppression and terror that had characterised the German occupation. Kesselring's name headed the list of German officers blamed for a long series of atrocities perpetrated by the German forces.

The Moscow Declaration

of October 1943 promised that "those German officers and men and members of the Nazi party who have been responsible for or have taken a consenting part in the above atrocities, massacres and executions will be sent back to the countries in which their abominable deeds were done in order that they may be judged and punished according to the laws of these liberated countries and of free governments which will be erected therein." However, the British, who had been a driving force in moulding the war crimes trial policy that culminated in the Nuremberg Trials, explicitly excluded high-ranking German officers in their custody. Thus, Kesselring's conviction became "a legal prerequisite if perpetrators of war crimes were to be found guilty by Italian courts".

The British held two major trials against the top German war criminals who had perpetrated crimes during the Italian campaign. For political reasons it was decided to hold the trials in Italy, but a request by Italy to allow an Italian judge to participate was denied on the grounds that Italy was not an Allied country. The trials were held under the Royal Warrant of 18 June 1945, thus essentially under British Common Military Law. The decision put the trials on a shaky legal basis, as foreign nationals were being tried for crimes against foreigners in a foreign country. The first trial, held in Rome, was of von Mackensen and Generalleutnant Kurt Mälzer

, the Commandant of Rome, for their part in the Ardeatine massacre. Both were sentenced to death on 30 November 1946.

Kesselring's own trial began in Venice on 17 February 1947. The British Military Court was presided over by Major General Sir Edmund Hakewill-Smith

, assisted by four lieutenant colonels. Colonel Richard C. Halse – who had already obtained the death penalty for von Mackensen and Mältzer – was the prosecutor. Kesselring's legal team was headed by Hans Laternser

, a skilful German lawyer who specialised in Anglo-Saxon law, had represented several defendants at the Nuremberg Trials, and would later go on to represent Generalfeldmarschall Erich von Manstein

. Kesselring's ability to pay his legal team was hampered because his assets had been frozen by the Allies, but his legal costs were eventually met by friends in South America

and relatives in Franconia

.

Kesselring was arraigned on two charges: the shooting of 335 Italians in the Ardeatine massacre and incitement to kill Italian civilians. Kesselring did not invoke the "Nuremberg defence". Rather, he maintained that his actions were lawful. On 6 May 1947 the Court found him guilty of both charges and sentenced him to death by firing squad, which was considered more honourable than hanging. The court left open the question of the legality of killing innocent persons in reprisals.

The planned major trial for the campaign of reprisals never took place, but a series of smaller trials was held instead in Padua

between April and June 1947 for SS Brigadeführer Willy Tensfeld, Kapitänleutnant

Waldemar Krummhaar, the 26th Panzer Division's Generalleutnant Eduard Crasemann

and SS Gruppenführer Max Simon

of the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division Reichsführer-SS. Tensfeld was acquitted; Crasemann was sentenced to 10 years; and Simon was sentenced to death, but his sentence was commuted. Simons's trial was the last held in Italy by the British. By 1949, British military tribunals had sentenced 230 Germans to death and another 447 to custodial sentences. None of the death sentences imposed between the end of 1946 and 1948 were carried out. A number of officers, all below the rank of General, including Herbert Kappler

, were transferred to the Italian courts for trial. These applied very different legal standards to the British – ones which were often more favourable to the defendants. Ironically, in view of the repeated attempts by many senior Wehrmacht commanders to shift blame for atrocities onto the SS, the most senior SS commanders in Italy, Karl Wolff

and Himmler's personal representative in Italy, SS Standartenführer Eugen Dollmann

, escaped prosecution.

Winston Churchill

immediately branded it as too harsh and intervened in favour of Kesselring. Field Marshal Alexander, now Governor General of Canada

, sent a telegram to Prime Minister Clement Attlee

in which he expressed his hope that Kesselring's sentence would be commuted. "As his old opponent on the battlefield", he started, "I have no complaints against him. Kesselring and his soldiers fought against us hard but clean." Alexander had expressed his admiration for Kesselring as a military commander as early as 1943. In his 1961 memoirs Alexander paid tribute to Kesselring as a commander who "showed great skill in extricating himself from the desperate situations into which his faulty intelligence had led him". Alexander's sentiments were echoed by Lieutenant General Sir Oliver Leese

, who had commanded the British Eighth Army

in the Italian campaign. In a May 1947 interview, Leese said he was "very sad" to hear of what he considered "British victor's justice" being imposed on Kesselring, an "extremely gallant soldier who had fought his battles fairly and squarely". Lord de L'Isle

, who had been awarded the Victoria Cross

for gallantry at Anzio, raised the issue in the House of Lords

.

The Italian government flatly refused to carry out death sentences, as the death penalty had been abolished in Italy in 1944 and was regarded as a relic of Mussolini's Fascist

regime. The Italian decision was very disappointing to the British government because the trials had partly been intended to meet the expectations of the Italian public. The War Office notified Lieutenant General Sir John Harding

, who had succeeded Alexander as commander of British forces in the Mediterranean in 1946, that there should be no more death sentences and those already imposed should be commuted. Accordingly, Harding commuted the death sentences imposed on von Mackensen, Mältzer and Kesselring to life imprisonment on 4 July 1947. Mältzer died while still in prison in February 1952, while von Mackensen, after having his sentence reduced to 21 years, was eventually freed in October 1952. Kesselring was moved from Mestre

prison near Venice to Wolfsberg, Carinthia, in May 1947. In October 1947 he was transferred for the last time, to Werl

prison, in Westphalia

.

In Wolfsberg, Kesselring was approached by a former SS major who had an escape plan prepared. Kesselring declined the offer on the grounds that he felt it would be seen as a confession of guilt. Other senior Nazi figures did manage to escape from Wolfsberg to South America or Syria

.

Kesselring resumed his work on a history of the war that he was writing for the US Army's Historical Division. This effort, working under the direction of Generaloberst Franz Halder

in 1946, brought together a number of German generals for the purpose of producing historical studies of the war, including Gotthard Heinrici

, Heinz Guderian

, Lothar Rendulic

, Hasso von Manteuffel

and Georg von Küchler

. Kesselring contributed studies of the war in Italy and North Africa and the problems faced by the German high command. Kesselring also worked secretly on his memoirs. The manuscript was smuggled out by Irmgard Horn-Kesselring, Rainer's mother, who typed it up at her home.

An influential group assembled in Britain to lobby for his release from prison. Headed by Lord Hankey

, the group included politicians Lord de L'Isle and Richard Stokes

, Field Marshal Alexander and Admiral of the Fleet

The Earl of Cork and Orrery

, and military historians Basil Liddell Hart

and J. F. C. Fuller. Upon re-gaining the prime ministership in 1951, Winston Churchill, who was closely associated with the group, gave priority to the quick release of the war criminals remaining in British custody.

Meanwhile, in Germany, the release of military prisoners had become a political issue. With the establishment of West Germany

in 1949, and the advent of the Cold War

between the former Allies and the Soviet Union, it became inevitable that the Wehrmacht would be revived in some form, and there were calls for amnesty for military prisoners as a precondition for German military participation in the Western Alliance. A media campaign gradually gathered steam in Germany. Westdeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung

published an interview with Liny Kesselring and Stern

ran a series about Kesselring and von Manstein entitled "Justice, Not Clemency". The pressure on the British government was increased in 1952, when the German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer

made it clear that West German ratification of the European Defence Community

Treaty was dependent on the release of German military figures.

In July 1952, Kesselring was diagnosed with a cancerous growth in the throat. During World War I, he had frequently smoked up to twenty cigars per day but he quit smoking in 1925. Although the British were suspicious of the diagnosis, they were concerned that he might die in prison like Mältzer, which would be a public relations disaster. Kesselring was transferred to a hospital, under guard. In October 1952, Kesselring was released from his prison sentence on the grounds of ill-health.

. Leadership of this organisation tarnished his reputation. He attempted to reform the organisation, proposing that the new German flag

be flown instead of the old Imperial Flag; that the old Stahlhelm greeting Front heil! be abolished; and that members of the Social Democratic Party of Germany

be allowed to join. The response was very unenthusiastic.

Kesselring's memoirs were published in 1953, as Soldat bis zum letzten Tag (A Soldier to the Last Day). They were reprinted in English as A Soldier's Record a year later. Although written while he was in prison, without access to his papers, the memoirs formed a valuable resource, informing military historians on topics such as the background to the invasion of the Soviet Union. When the English edition was published, Kesselring's contentions that the Luftwaffe was not defeated in the air in the Battle of Britain and that Operation Sea Lion– the invasion of Britain–was thought about but never seriously planned were controversial. In 1955, he published a second book, Gedanken zum Zweiten Weltkrieg (Thoughts on the Second World War).

Interviewed by the Italian journalist Enzo Biagi

soon after his release in 1952, Kesselring defiantly described the Marzabotto massacre

–in which almost 800 innocent Italian civilians had been killed–as a "normal military operation". Since the event was considered to be the worst massacre of civilians committed in Italy during World War II, Kesselring's definition caused outcry and indignation in the Italian Parliament. Kesselring reacted by raising the provocation and affirming that he had "saved Italy" and that the Italians ought to build him "a monument". In response, on 4 December 1952, Piero Calamandrei

, an Italian jurist, soldier, university professor, and politician, who had been a leader of the Resistance, penned an antifascist poem, Lapide ad ignominia ("A Monument to Ignominy"). In the poem, Calamandrei stated that if Kesselring returned he would indeed find a monument, but one stronger than stone, composed of Italian Resistance fighters who "willingly took up arms, to preserve dignity, not to promote hate, and who decided to fight back against the shame and terror of the world". Calamandrei's poem appears in monuments in the towns of Cuneo

and Montepulciano

.

After release from prison, Kesselring protested against what he regarded as the "unjustly smirched reputation of the German soldier". In November 1953, testifying at a war crimes trial, he warned that "there won't be any volunteers for the new German army if the German government continues to try German soldiers for acts committed in World War II". He enthusiastically supported the European Defence Community

and suggested that the "war opponents of yesterday must become the peace comrades and friends of tomorrow". On the other hand, he also declared that he found "astonishing" those who believe "that we must revise our ideas in accordance with democratic principles ... That is more than I can take."

In March 1954, Kesselring and Liny toured Austria

ostensibly as private citizens. He met with former comrades-in-arms and prison-mates, some of them former SS members, causing embarrassment to the Austrian government, which ordered his deportation. He ignored the order and completed his tour before leaving a week later, as per his original plan. His only official service was on the Medals Commission, which was established by President

Theodor Heuss

. Ultimately, the commission unanimously recommended that medals should be permitted to be worn—but without the swastika

. He was an expert witness for the "Generals' Trials". The Generals' Trials were trials of German citizens before German courts for crimes committed in Germany, the most prominent of which was that of Generalfeldmarschall Ferdinand Schörner

.

Kesselring died at Bad Nauheim

, West Germany

, on 16 July 1960 at the age of 74. He was given a quasi-military Stahlhelm funeral and buried in Bergfriedhof Cemetery in Bad Wiessee

. Members of Stahlhelm acted as his pall bearers and fired a rifle volley over his grave. His former chief of staff, Siegfried Westphal

, spoke for the veterans of North Africa and Italy, describing Kesselring as "a man of admirable strength of character whose care was for soldiers of all ranks". General Josef Kammhuber

spoke on behalf of the Luftwaffe and Bundeswehr

, expressing the hope that Kesselring would be remembered for his earlier accomplishments rather than for his later activities. Also present were the former SS Oberstgruppenführer

Sepp Dietrich

, the ex-Chancellor Franz von Papen

, Generalfeldmarschall Ferdinand Schörner

, Grossadmiral and former Reichspräsident

Karl Dönitz

, Otto Remer, SS Standartenführer

Joachim Peiper

, and former Ambassador Rudolf Rahn.

In 2000, a memorial event was held in Bad Wiessee marking the fortieth anniversary of Kesselring's death. No representatives of the Bundeswehr attended, on the grounds that Kesselring was "not worthy of being part of our tradition". Instead, the task of remembering the Generalfeldmarschall fell to two veterans groups, the Deutsche Montecassino Vereinigung (German Monte Cassino Association) and the Bund Deutscher Fallschirmjäger (Association of German Paratroopers). To his ageing troops, Kesselring remained a commander to be commemorated.

Luftwaffe

Luftwaffe is a generic German term for an air force. It is also the official name for two of the four historic German air forces, the Wehrmacht air arm founded in 1935 and disbanded in 1946; and the current Bundeswehr air arm founded in 1956....

Generalfeldmarschall

Generalfeldmarschall

Field Marshal or Generalfeldmarschall in German, was a rank in the armies of several German states and the Holy Roman Empire; in the Austrian Empire, the rank Feldmarschall was used...

during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. In a military career that spanned both World Wars, Kesselring became one of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

's most skilful commanders, being one of 27 soldiers awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds

Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross was a grade of the 1939 version of the 1813 created Iron Cross . The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross was the highest award of Germany to recognize extreme battlefield bravery or successful military leadership during World War II...

. Nicknamed "Smiling Albert" by the Allies

Allies of World War II

The Allies of World War II were the countries that opposed the Axis powers during the Second World War . Former Axis states contributing to the Allied victory are not considered Allied states...

The nickname "Smiling Albert" was bestowed on Kesselring by the Allies. It is not used by German writers. It was used during the war; see and "Uncle Albert" by his troops, he was one of the most popular generals of World War II with the rank and file.

Kesselring joined the Bavarian Army

Bavarian army

The Bavarian Army was the army of the Electorate and then Kingdom of Bavaria. It existed from 1682 as the standing army of Bavaria until the merger of the military sovereignty of Bavaria into that of the German State in 1919...

as an officer cadet

Officer Cadet

Officer cadet is a rank held by military and merchant navy cadets during their training to become commissioned officers and merchant navy officers, respectively. The term officer trainee is used interchangeably in some countries...

in 1904, and served in the artillery branch. He completed training as a balloon

Observation balloon

Observation balloons are balloons that are employed as aerial platforms for intelligence gathering and artillery spotting. Their use began during the French Revolutionary Wars, reaching their zenith during World War I, and they continue in limited use today....

observer in 1912. During World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, he served on both the Western

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

and Eastern

Eastern Front (World War I)

The Eastern Front was a theatre of war during World War I in Central and, primarily, Eastern Europe. The term is in contrast to the Western Front. Despite the geographical separation, the events in the two theatres strongly influenced each other...

fronts and was posted to the General Staff

General Staff

A military staff, often referred to as General Staff, Army Staff, Navy Staff or Air Staff within the individual services, is a group of officers and enlisted personnel that provides a bi-directional flow of information between a commanding officer and subordinate military units...

, despite not having attended the War Academy

War Academy (Kingdom of Bavaria)

The Kriegsakademie of the Bavarian Army was the military academy and staff college of the Kingdom of Bavaria, existing from 1867 to the beginning of World War I in 1914...

. Kesselring remained in the Army after the war but was discharged in 1933 to become head of the Department of Administration at the Reich Commissariat for Aviation

Reich Air Ministry

thumb|300px|The Ministry of Aviation, December 1938The Ministry of Aviation was a government department during the period of Nazi Germany...

, where he was involved in the re-establishment of the aviation industry and the laying of the foundations for the Luftwaffe, serving as its Chief of Staff from 1936 to 1938.

During World War II he commanded air forces in the invasions of Poland

Invasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

and France

Battle of France

In the Second World War, the Battle of France was the German invasion of France and the Low Countries, beginning on 10 May 1940, which ended the Phoney War. The battle consisted of two main operations. In the first, Fall Gelb , German armoured units pushed through the Ardennes, to cut off and...

, the Battle of Britain

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain is the name given to the World War II air campaign waged by the German Air Force against the United Kingdom during the summer and autumn of 1940...

, and Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

. As Commander-in-Chief South, he was overall German commander in the Mediterranean theatre

Mediterranean Theatre of World War II

The African, Mediterranean and Middle East theatres encompassed the naval, land, and air campaigns fought between the Allied and Axis forces in the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and Africa...

, which included the operations in North Africa

North African campaign

During the Second World War, the North African Campaign took place in North Africa from 10 June 1940 to 13 May 1943. It included campaigns fought in the Libyan and Egyptian deserts and in Morocco and Algeria and Tunisia .The campaign was fought between the Allies and Axis powers, many of whom had...

. Kesselring conducted an uncompromising defensive campaign against the Allied forces in Italy

Italian Campaign (World War II)

The Italian Campaign of World War II was the name of Allied operations in and around Italy, from 1943 to the end of the war in Europe. Joint Allied Forces Headquarters AFHQ was operationally responsible for all Allied land forces in the Mediterranean theatre, and it planned and commanded the...

until he was injured in an accident in October 1944. In the final campaign of the war, he commanded German forces on the Western Front. He won the respect of his Allied opponents for his military accomplishments, but his record was marred by massacres committed by troops under his command in Italy.

After the war, Kesselring was tried for war crimes and sentenced to death. The sentence was subsequently commuted to life imprisonment

Life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is a sentence of imprisonment for a serious crime under which the convicted person is to remain in jail for the rest of his or her life...

. A political and media campaign resulted in his release in 1952, ostensibly on health grounds. He was one of only three Generalfeldmarschalls to publish his memoirs, entitled Soldat bis zum letzten Tag (A Soldier to the Last Day).

Early life

Albert Kesselring was born in MarktsteftMarktsteft

Marktsteft is a town in the district of Kitzingen, in Bavaria, Germany. It is situated on the left bank of the Main, southwest of Kitzingen.It was the birthplace of the well-known Second World War general Albert Kesselring.-External links:*...

, Bavaria

Kingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria was a German state that existed from 1806 to 1918. The Bavarian Elector Maximilian IV Joseph of the House of Wittelsbach became the first King of Bavaria in 1806 as Maximilian I Joseph. The monarchy would remain held by the Wittelsbachs until the kingdom's dissolution in 1918...

, on 30 November 1885, the son of Carl Adolf Kesselring, a schoolmaster and town councillor, and his wife Rosina, who was born a Kesselring, being Carl's second cousin. Albert's early years were spent in Marktsteft, where relatives had operated a brewery since 1688.

Matriculating from the Christian Ernestinum Secondary School in Bayreuth in 1904, Kesselring joined the German Army

German Army (German Empire)

The German Army was the name given the combined land forces of the German Empire, also known as the National Army , Imperial Army or Imperial German Army. The term "Deutsches Heer" is also used for the modern German Army, the land component of the German Bundeswehr...

as an Fahnenjunker (officer cadet

Officer Cadet

Officer cadet is a rank held by military and merchant navy cadets during their training to become commissioned officers and merchant navy officers, respectively. The term officer trainee is used interchangeably in some countries...

) in the 2nd Bavarian Foot Artillery Regiment

4th Royal Bavarian Division

The 4th Royal Bavarian Division was a unit of the Royal Bavarian Army which served alongside the Prussian Army as part of the Imperial German Army. The division was formed on November 27, 1815 as an Infantry Division of the Würzburg General Command...

. The regiment was based at Metz

Metz

Metz is a city in the northeast of France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers.Metz is the capital of the Lorraine region and prefecture of the Moselle department. Located near the tripoint along the junction of France, Germany, and Luxembourg, Metz forms a central place...

and was responsible for maintaining its forts. He remained with the regiment until 1915, except for periods at the Military Academy from 1905 to 1906, at the conclusion of which he received his commission as a Leutnant (lieutenant

Lieutenant