History of the Jews of Thessaloniki

Encyclopedia

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

of Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki , historically also known as Thessalonica, Salonika or Salonica, is the second-largest city in Greece and the capital of the region of Central Macedonia as well as the capital of the Decentralized Administration of Macedonia and Thrace...

, Greece

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

, reaches back two thousand years.

The city of Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki , historically also known as Thessalonica, Salonika or Salonica, is the second-largest city in Greece and the capital of the region of Central Macedonia as well as the capital of the Decentralized Administration of Macedonia and Thrace...

(also known as Salonika) housed a major Jewish

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

community, mostly of Sephardic

Sephardi Jews

Sephardi Jews is a general term referring to the descendants of the Jews who lived in the Iberian Peninsula before their expulsion in the Spanish Inquisition. It can also refer to those who use a Sephardic style of liturgy or would otherwise define themselves in terms of the Jewish customs and...

origin, until the middle of the Second World War. It is the only known example of a city of this size in the Jewish diaspora

Jewish diaspora

The Jewish diaspora is the English term used to describe the Galut גלות , or 'exile', of the Jews from the region of the Kingdom of Judah and Roman Iudaea and later emigration from wider Eretz Israel....

that retained a Jewish majority for centuries.

Sephardic Jews immigrated to the city following their expulsion from Spain by Christian rulers under the Alhambra Decree

Alhambra decree

The Alhambra Decree was an edict issued on 31 March 1492 by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain ordering the expulsion of Jews from the Kingdom of Spain and its territories and possessions by 31 July of that year.The edict was formally revoked on 16 December 1968, following the Second...

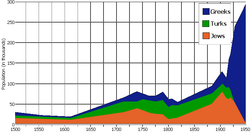

in 1492. This community influenced the Sephardic world both culturally and economically, and the city was nicknamed la madre de Israel (mother of Israel). The community experienced a "golden age" in the 16th century, when they developed a strong culture in the city. Like other groups in the Ottoman Empire, they continued to practice traditional culture during the time when western Europe was undergoing industrialization. In the middle of 19th century, Jewish educators and entrepreneurs came to Thessaloniki from Western Europe to develop schools and industries; they brought contemporary ideas from Europe that changed the culture of the city. With the development of industry, both Jewish and other ethnic populations became industrial workers and developed a large working class, with labor movements contributing to the intellectual mix of the city. After Greece achieved independence from the Ottoman Empire, it made Jews full citizens of the country in the 1920s.

During World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, the German

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

Nazis occupied Greece in 1941, and started to persecute the Jews as they had in other parts of Europe. In 1943 they forced the Jews in Thessaloniki into a ghetto

Ghetto

A ghetto is a section of a city predominantly occupied by a group who live there, especially because of social, economic, or legal issues.The term was originally used in Venice to describe the area where Jews were compelled to live. The term now refers to an overcrowded urban area often associated...

near the rail lines, and started deporting them to concentration

Concentration

In chemistry, concentration is defined as the abundance of a constituent divided by the total volume of a mixture. Four types can be distinguished: mass concentration, molar concentration, number concentration, and volume concentration...

and labor camps, where most of the 60,000 deported died. This resulted in the near-extermination of the community. Only 1200 Jews live in the city today.

Early settlement

Paul of TarsusPaul of Tarsus

Paul the Apostle , also known as Saul of Tarsus, is described in the Christian New Testament as one of the most influential early Christian missionaries, with the writings ascribed to him by the church forming a considerable portion of the New Testament...

' First Epistle to the Thessalonians

First Epistle to the Thessalonians

The First Epistle to the Thessalonians, usually referred to simply as First Thessalonians and often written 1 Thessalonians, is a book from the New Testament of the Christian Bible....

mentions Hellenized

Hellenization

Hellenization is a term used to describe the spread of ancient Greek culture, and, to a lesser extent, language. It is mainly used to describe the spread of Hellenistic civilization during the Hellenistic period following the campaigns of Alexander the Great of Macedon...

Jews in the city about 52 CE. In 1170, Benjamin of Tudela

Benjamin of Tudela

Benjamin of Tudela was a medieval Jewish traveler who visited Europe, Asia, and Africa in the 12th century. His vivid descriptions of western Asia preceded those of Marco Polo by a hundred years...

reported that there were 500 Jews in Thessaloniki. In the following centuries, the native Romaniote

Romaniotes

The Romaniotes or Romaniots are a Jewish population who have lived in the territory of today's Greece and neighboring areas with large Greek populations for more than 2,000 years. Their languages were Yevanic, a Greek dialect, and Greek. They derived their name from the old name for the people...

community was joined by some Italian and Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews, also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim , are the Jews descended from the medieval Jewish communities along the Rhine in Germany from Alsace in the south to the Rhineland in the north. Ashkenaz is the medieval Hebrew name for this region and thus for Germany...

. A small Jewish population lived here during the Byzantine period, but it left virtually no trace in documents or archeological artifacts. Researchers have not determined where the first Jews lived in the city.

Under the Ottomans

In 1430, the start of Ottoman domination, the Jewish population was still small. The Ottomans used population transfers within the empire following military conquests to achieve goals of border security or repopulation; they called it Sürgün. Following the fall of ConstantinopleFall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire, which occurred after a siege by the Ottoman Empire, under the command of Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, against the defending army commanded by Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI...

in 1453, an example of sürgün was the Ottomans' forcing Jews from the Balkans and Anatolia

Anatolia

Anatolia is a geographic and historical term denoting the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey...

to relocate there, which they renamed Istanbul and made the new capital of the Empire. At the time, few Jews were left in Salonika; none were recorded in the Ottoman census of 1478.

Arrival of Sephardic Jews

Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs is the collective title used in history for Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being both descended from John I of Castile; they were given a papal dispensation to deal with...

promulgated the Alhambra Decree

Alhambra decree

The Alhambra Decree was an edict issued on 31 March 1492 by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain ordering the expulsion of Jews from the Kingdom of Spain and its territories and possessions by 31 July of that year.The edict was formally revoked on 16 December 1968, following the Second...

to expel Sephardic Jews from their domains. Many immigrated to Salonica, sometimes after a stop in Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

or Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

. The Ottoman Empire granted protection to Jews as dhimmi

Dhimmi

A , is a non-Muslim subject of a state governed in accordance with sharia law. Linguistically, the word means "one whose responsibility has been taken". This has to be understood in the context of the definition of state in Islam...

s and encouraged the newcomers to settle in its territories. According to the historians Rosamond McKitterick and Christopher Allmand, the Empire's invitation to the expelled Jews was a demographic strategy to prevent ethnic Greeks from dominating the city.

The first Sephardim came in 1492 from Majorca. They were "repentant" returnees to Judaism after earlier forced conversion to Catholicism. In 1493, Castilians

Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval and modern state in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accession of the then King Ferdinand III of Castile to the vacant Leonese throne...

and Sicilians

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

joined them. In subsequent years, other Jews came from those lands and also from Aragon

Kingdom of Aragon

The Kingdom of Aragon was a medieval and early modern kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula, corresponding to the modern-day autonomous community of Aragon, in Spain...

, Valencia, Calabria

Calabria

Calabria , in antiquity known as Bruttium, is a region in southern Italy, south of Naples, located at the "toe" of the Italian Peninsula. The capital city of Calabria is Catanzaro....

, Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

, Apulia

Apulia

Apulia is a region in Southern Italy bordering the Adriatic Sea in the east, the Ionian Sea to the southeast, and the Strait of Òtranto and Gulf of Taranto in the south. Its most southern portion, known as Salento peninsula, forms a high heel on the "boot" of Italy. The region comprises , and...

, Naples

Naples

Naples is a city in Southern Italy, situated on the country's west coast by the Gulf of Naples. Lying between two notable volcanic regions, Mount Vesuvius and the Phlegraean Fields, it is the capital of the region of Campania and of the province of Naples...

, and Provence

Provence

Provence ; Provençal: Provença in classical norm or Prouvènço in Mistralian norm) is a region of south eastern France on the Mediterranean adjacent to Italy. It is part of the administrative région of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur...

. Later, in 1540 and 1560, Jews from Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

sought refuge in Salonika in response to the political persecution of the marranos. In addition to these Sephardim, a few Ashkenazim

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews, also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim , are the Jews descended from the medieval Jewish communities along the Rhine in Germany from Alsace in the south to the Rhineland in the north. Ashkenaz is the medieval Hebrew name for this region and thus for Germany...

arrived from Austria

Austria

Austria , officially the Republic of Austria , is a landlocked country of roughly 8.4 million people in Central Europe. It is bordered by the Czech Republic and Germany to the north, Slovakia and Hungary to the east, Slovenia and Italy to the south, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein to the...

, Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

and Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

. They were sometimes forcibly relocated under the Ottoman policy of "sürgün," following the conquest of land by Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I was the tenth and longest-reigning Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, from 1520 to his death in 1566. He is known in the West as Suleiman the Magnificent and in the East, as "The Lawgiver" , for his complete reconstruction of the Ottoman legal system...

beginning in 1526. Salonika's registers indicate the presence of "Buda

Buda

For detailed information see: History of Buda CastleBuda is the western part of the Hungarian capital Budapest on the west bank of the Danube. The name Buda takes its name from the name of Bleda the Hun ruler, whose name is also Buda in Hungarian.Buda comprises about one-third of Budapest's...

Jews" after the conquest of that city by the Turks in 1541. Immigration was great enough that by 1519, the Jews represented 56% of the population and in 1613, 68%.

Religious organization

Each group of new arrivals founded its own community (aljama in Spanish), whose rites ("minhagMinhag

Minhag is an accepted tradition or group of traditions in Judaism. A related concept, Nusach , refers to the traditional order and form of the prayers...

im") differed from those of other communities. The synagogues cemented each group, and their names most often referred to the groups' origins. For example, Katallan Yashan (Old Catalan) was founded in 1492 and Katallan Hadash (New Catalonia) at the end of the 16th century.

| Name of synagogue | Date of construction | Name of synagogue | Date of construction | Name of synagogue | Date of construction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ets ha Chaim | 1st century | Apulia | 1502 | Yahia | 1560 |

| Ashkenaz or Varnak | 1376 | Lisbon Yashan | 1510 | Sicilia Hadash | 1562 |

| Mayorka | 1391 | Talmud Torah Hagadol | 1520 | Beit Aron | 1575 |

| Provincia | 1394 | Portugal | 1525 | Italia Hadash | 1582 |

| Italia Yashan | 1423 | Evora | 1535 | Mayorka Sheni | 16th century |

| Guerush Sfarad | 1492 | Estrug | 1535 | Katallan Chadash | 16th century |

| Kastilla | 1492-3 | Lisbon Chadash | 1536 | Italia Sheni | 1606 |

| Aragon | 1492-3 | Otranto | 1537 | Shalom | 1606 |

| Katallan Yashan | 1492 | Ishmael | 1537 | Har Gavoa | 1663 |

| Kalabria Yashan | 1497 | Tcina | 1545 | Mograbis | 17th century |

| Sicilia Yashan | 1497 | Nevei Tsedek | 1550 |

A government institution called Talmud Torah Hagadol was introduced in 1520 to head all the congregations and make decisions (haskamot) which applied to all. It was administered by seven members with annual terms. This institution provided an educational program for young boys, and was a preparatory school for entry to yeshivot

Yeshiva

Yeshiva is a Jewish educational institution that focuses on the study of traditional religious texts, primarily the Talmud and Torah study. Study is usually done through daily shiurim and in study pairs called chavrutas...

. It hosted hundreds of students. In addition to Jewish studies, it taught humanities

Humanities

The humanities are academic disciplines that study the human condition, using methods that are primarily analytical, critical, or speculative, as distinguished from the mainly empirical approaches of the natural sciences....

, Latin and Arabic, as well as medicine, the natural sciences and astronomy. The yeshivot of Salonika were frequented by Jews from throughout the Ottoman Empire and even farther abroad; there were students from Italy and Eastern Europe. After completing their studies, some students were appointed rabbis in the Jewish communities of the Empire and Europe, including cities such as Amsterdam

Amsterdam

Amsterdam is the largest city and the capital of the Netherlands. The current position of Amsterdam as capital city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is governed by the constitution of August 24, 1815 and its successors. Amsterdam has a population of 783,364 within city limits, an urban population...

and Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

. The success of its educational institutions was such that there was no illiteracy among the Jews of Salonika.

Economic activities

Shabbat

Shabbat is the seventh day of the Jewish week and a day of rest in Judaism. Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before sunset on Friday evening until a few minutes after when one would expect to be able to see three stars in the sky on Saturday night. The exact times, therefore, differ from...

) - the Jewish holy day. They traded with the rest of the Ottoman Empire, and the countries of Latin Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

and Genoa

Genoa

Genoa |Ligurian]] Zena ; Latin and, archaically, English Genua) is a city and an important seaport in northern Italy, the capital of the Province of Genoa and of the region of Liguria....

, and with all the Jewish communities scattered throughout the Mediterranean. One sign of the influence of Salonikan Jews on trading is in the 1556 boycott of the port of Ancona

Ancona

Ancona is a city and a seaport in the Marche region, in central Italy, with a population of 101,909 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region....

, Papal States

Papal States

The Papal State, State of the Church, or Pontifical States were among the major historical states of Italy from roughly the 6th century until the Italian peninsula was unified in 1861 by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia .The Papal States comprised territories under...

, in response to the auto-da-fé

Auto-da-fé

An auto-da-fé was the ritual of public penance of condemned heretics and apostates that took place when the Spanish Inquisition or the Portuguese Inquisition had decided their punishment, followed by the execution by the civil authorities of the sentences imposed...

issued by Pope Paul IV against 25 marrano

Marrano

Marranos were Jews living in the Iberian peninsula who converted to Christianity rather than be expelled but continued to observe rabbinic Judaism in secret...

es.

Salonikan Jews were unique in their participation in all economic niches, not confining their business to a few sectors, as was the case where Jews were a minority. They were active in all levels of society, from porters to merchants. Salonika had a large number of Jewish fishermen, unmatched elsewhere, even in what is now Israel

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel is the Biblical name for the territory roughly corresponding to the area encompassed by the Southern Levant, also known as Canaan and Palestine, Promised Land and Holy Land. The belief that the area is a God-given homeland of the Jewish people is based on the narrative of the...

.

The Jewish speciality was spinning

Spinning (textiles)

Spinning is a major industry. It is part of the textile manufacturing process where three types of fibre are converted into yarn, then fabric, then textiles. The textiles are then fabricated into clothes or other artifacts. There are three industrial processes available to spin yarn, and a...

wool

Wool

Wool is the textile fiber obtained from sheep and certain other animals, including cashmere from goats, mohair from goats, qiviut from muskoxen, vicuña, alpaca, camel from animals in the camel family, and angora from rabbits....

. They imported technology from Spain where this craft was highly developed. Only the quality of the wool, better in Spain, differed in Salonica. The community made rapid decisions (haskamot) to require all congregations to regulate this industry. They forbade, under pain of excommunication (cherem), exporting wool and indigo less than three days' travel from the city. The Salonican sheets, blankets and carpets acquired a high profile and were exported throughout the empire from Istanbul to Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

through Smyrna

Smyrna

Smyrna was an ancient city located at a central and strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Thanks to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to prominence. The ancient city is located at two sites within modern İzmir, Turkey...

. The industry spread to all localities close to the Thermaic Gulf

Thermaic Gulf

The Thermaic Gulf is a gulf of the Aegean Sea located immediately south of Thessaloniki, east of Pieria and Imathia, and west of Chalkidiki . It was named after the ancient town of Therma, which was situated on the northeast coast of the gulf...

. This same activity became a matter of state when Sultan Selim II

Selim II

Selim II Sarkhosh Hashoink , also known as "Selim the Sot " or "Selim the Drunkard"; and as "Sarı Selim" or "Selim the Blond", was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1566 until his death in 1574.-Early years:He was born in Constantinople a son of Suleiman the...

decided to dress his Janissary

Janissary

The Janissaries were infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops and bodyguards...

troops with warm and waterproof woollen garments. He made arrangements to protect his supply. His Sublime Porte issued a firman

Firman

A firman is a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in certain historical Islamic states, including the Ottoman Empire, Mughal Empire, State of Hyderabad, and Iran under Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. The word firman comes from the meaning "decree" or "order"...

in 1576 forcing sheep raisers to provide their wool exclusively to the Jews to guarantee the adequacy of their supply. Other provisions strictly regulated the types of woollen production, production standards and deadlines. Tons of woollen goods were transported by boat, camel and horse to Istanbul to cloak the janissaries against the approaching winter. Towards 1578, both sides agreed that the supply of wool would serve as sufficient payment by the State for cloth and replace the cash payment. This turned out to be disadvantageous for the Jews.

Economic decline

The increase in the number of JanissariesJanissary

The Janissaries were infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops and bodyguards...

contributed to an increase in clothing orders putting Jews in a very difficult situation. Contributing to their problems were currency inflation concurrent with a state financial crisis.

Only 1,200 shipments were required initially. However, the orders surpassed 4,000 in 1620. Financially challenged, the factories began cheating on quality. This was discovered.

Rabbi Judah Covo at the head of a Salonican delegation was summoned to explain this deterioration in Istanbul and was sentenced to hang. This left a profound impression in Salonica. Thereafter, applications of the Empire were partially reduced and reorganized production.

These setbacks were heralds of a dark period for Salonican Jews. The flow of migrants from the Iberian Peninsula had gradually dried up. Jews favored such Western European cities as London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, Amsterdam

Amsterdam

Amsterdam is the largest city and the capital of the Netherlands. The current position of Amsterdam as capital city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands is governed by the constitution of August 24, 1815 and its successors. Amsterdam has a population of 783,364 within city limits, an urban population...

and Bordeaux

Bordeaux

Bordeaux is a port city on the Garonne River in the Gironde department in southwestern France.The Bordeaux-Arcachon-Libourne metropolitan area, has a population of 1,010,000 and constitutes the sixth-largest urban area in France. It is the capital of the Aquitaine region, as well as the prefecture...

. This phenomenon led to a progressive estrangement of the Ottoman Sephardim from the West. Although the Jews had brought many new European technologies, including that of printing

Printing

Printing is a process for reproducing text and image, typically with ink on paper using a printing press. It is often carried out as a large-scale industrial process, and is an essential part of publishing and transaction printing....

, they became less and less competitive against other ethno-religious groups. The earlier well-known Jewish doctors and translators were gradually replaced by their Christian counterparts, mostly Armenians and Greeks. In the world of trading, the Jews were supplanted by Western Christians, who were protected by the western powers through their consular bodies. Salonika lost its pre-eminence following the phasing-out of Venice, its commercial partner, and the rising power of the port of Smyrna.

Moreover, the Jews, like other dhimmi

Dhimmi

A , is a non-Muslim subject of a state governed in accordance with sharia law. Linguistically, the word means "one whose responsibility has been taken". This has to be understood in the context of the definition of state in Islam...

s, had to suffer the consequences of successive defeats of the Empire by the West. The city, strategically placed on a road travelled by armies, often saw retaliation by janissaries against "infidels." Throughout the 17th century, there was migration of Jews from Salonika to Istanbul, the Israel

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel is the Biblical name for the territory roughly corresponding to the area encompassed by the Southern Levant, also known as Canaan and Palestine, Promised Land and Holy Land. The belief that the area is a God-given homeland of the Jewish people is based on the narrative of the...

, and especially Smyrna

Smyrna

Smyrna was an ancient city located at a central and strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Thanks to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to prominence. The ancient city is located at two sites within modern İzmir, Turkey...

. The Jewish community of Smyrna became composed of Salonikan émigrés. Plague, along with other epidemics such as cholera which arrived in Salonika in 1823, also contributed to the weakening of Salonika and its Jewish community.

Western products, which began to appear in the East in large quantities in the early to mid-19th century, was a severe blow to the Salonikan economy, including the Jewish textile industry. The state eventually even began supplying janissaries with "Provencal

Provence

Provence ; Provençal: Provença in classical norm or Prouvènço in Mistralian norm) is a region of south eastern France on the Mediterranean adjacent to Italy. It is part of the administrative région of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur...

clothing", which sold in low-priced lots, in preference to Salonican wools, whose quality had continued to deteriorate. Short of cash, the Jews were forced into paying the grand vizier more than half of their taxes in the form of promissory notes. Textile production declined rapidly and then stopped completely with the abolition of the body of janissaries in 1826.

Deterioration of Judaism and arrival of Sabbatai Zevi

Yeshiva

Yeshiva is a Jewish educational institution that focuses on the study of traditional religious texts, primarily the Talmud and Torah study. Study is usually done through daily shiurim and in study pairs called chavrutas...

were always busy teaching, but their output was very formalistic. They published books on religion, but these had little original thought. A witness reported that "outside it is always endless matters of worship and commercial law that absorb their attention and bear the brunt of their studies and their research. Their works are generally a restatement of their predecessors' writings."

From the 15th century, a messianic current had developed in the Sephardic world; the Redemption, marking the end of the world, which seemed imminent. This idea was fueled both by the economic decline of Salonica and the continued growth in Kabbalistic

Kabbalah

Kabbalah/Kabala is a discipline and school of thought concerned with the esoteric aspect of Rabbinic Judaism. It was systematized in 11th-13th century Hachmei Provence and Spain, and again after the Expulsion from Spain, in 16th century Ottoman Palestine...

studies based on the Zohar

Zohar

The Zohar is the foundational work in the literature of Jewish mystical thought known as Kabbalah. It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah and scriptural interpretations as well as material on Mysticism, mythical cosmogony, and mystical psychology...

booming in Salonican yeshivot. The end of time was announced successively in 1540 and 1568 and again in 1648 and 1666.

It is in this context that there arrived a young and brilliant Rabbi who had been expelled from the nearby Smyrna: Sabbatai Zevi

Sabbatai Zevi

Sabbatai Zevi, , was a Sephardic Rabbi and kabbalist who claimed to be the long-awaited Jewish Messiah. He was the founder of the Jewish Sabbatean movement...

. Banned from this city in 1651 after proclaiming himself the messiah, he came to Salonika, where his reputation as a scholar and Kabbalist grew very quickly. The greatest numbers to follow him were members of the Shalom Synagogue, often former marranos. After several years of caution, he again caused a scandal when, during a solemn banquet in the courtyard of the Shalom Synagogue, he pronounced the Tetragrammaton

Tetragrammaton

The term Tetragrammaton refers to the name of the God of Israel YHWH used in the Hebrew Bible.-Hebrew Bible:...

, ineffable in Jewish tradition, and introduced himself as the Messiah son of King David. The federal rabbinical council then drove him from the city, but Sabbatai Zevi went to disseminate his doctrine in other cities around the Sephardic world. His passage divided, as it did everywhere, Thessaloniki's Jewish community, and this situation caused so much turmoil that Sabbatai Zevi was summoned and imprisoned by the sultan. There, rather than prove his supernatural powers, he relented under fire, and instead converted to Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

. The dramatic turn of events was interpreted in various ways by his followers, the Sabbateans. Some saw this as a sign and converted themselves, while others rejected his doctrine and fully returned to Judaism. Some, though, remained publicly faithful to Judaism while continuing to secretly follow the teachings of Sabbatai Zevi. In Salonica, there were 300 families among the richest who decided in 1686 to embrace Islam before the rabbinical authorities could react, their conversion already having been happily accepted by the Ottoman authorities. Therefore, those that the Turks gave the surname "Donme," ("renegades") themselves divided into three groups: Izmirlis, Kuniosos and Yacoubi, forming a new component of the Salonikan ethno-religious mosaic. Although they chose conversion, they did not assimilate with the Turks, practicing strict endogamy, living in separate quarters, building their own mosques and maintaining a specific liturgy in their language. They participated greatly in the 19th century in the spread of modernist ideas in the empire . Then, as Turks, the Donme emigrated from the city following the assumption of power by the Greeks.

Modern times

From the second half of 19th century, the Jews of Salonika had a revival. Frankos, French Jews, and Italian Jews from LivornoLivorno

Livorno , traditionally Leghorn , is a port city on the Tyrrhenian Sea on the western edge of Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of approximately 160,000 residents in 2009.- History :...

were especially influential in introducing new methods of education, and developing new schools and intellectual environment for the Jewish population. Such Western modernists introduced new techniques and ideas to the Balkans from the industrialized world.

Industrialization

1880s

The 1880s was the decade that spanned from January 1, 1880 to December 31, 1889. They occurred at the core period of the Second Industrial Revolution. Most Western countries experienced a large economic boom, due to the mass production of railroads and other more convenient methods of travel...

the city began to industrialize, within the Ottoman Empire whose larger economy was declining. The entrepreneurs in Thessaloniki were mostly Jewish, unlike in other major Ottoman cities, where industrialization was led by other ethno-religious groups. The Italian Allatini brothers led Jewish entrepreneurship, establishing milling

Mill (grinding)

A grinding mill is a unit operation designed to break a solid material into smaller pieces. There are many different types of grinding mills and many types of materials processed in them. Historically mills were powered by hand , working animal , wind or water...

and other food industries, brick

Brick

A brick is a block of ceramic material used in masonry construction, usually laid using various kinds of mortar. It has been regarded as one of the longest lasting and strongest building materials used throughout history.-History:...

making, and processing plants for tobacco

Tobacco

Tobacco is an agricultural product processed from the leaves of plants in the genus Nicotiana. It can be consumed, used as a pesticide and, in the form of nicotine tartrate, used in some medicines...

. Several traders supported the introduction of a large textile-production industry, superseding the weaving of cloth in a system of artisanal production.

With industrialization, many Salonikans of all faiths became factory workers, part of a new proletariat. Given their population in the city, a large Jewish working class developed. Employers hired labor without regard for religion or ethnicity, unlike the common practice in other parts of the Ottoman Empire. Workers movements developed in the city which crossed ethnic lines; in later years, the labor movements here became marked by issues of nationalism and identity.

Haskalah

Haskalah

Haskalah , the Jewish Enlightenment, was a movement among European Jews in the 18th–19th centuries that advocated adopting enlightenment values, pressing for better integration into European society, and increasing education in secular studies, Hebrew language, and Jewish history...

, the movement of thought inspired by the Jewish Enlightenment

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

, touched the Ottoman world at the end of the 19th century, after its spread among Jewish populations of Western and Eastern Europe. These western groups helpe stimulate the city's economic revival.

The maskilim and Moses Allatini from Livorno

Livorno

Livorno , traditionally Leghorn , is a port city on the Tyrrhenian Sea on the western edge of Tuscany, Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of approximately 160,000 residents in 2009.- History :...

, Italy, brought new educational style. In 1856, with the help of the Rothschilds

Rothschild family

The Rothschild family , known as The House of Rothschild, or more simply as the Rothschilds, is a Jewish-German family that established European banking and finance houses starting in the late 18th century...

, he founded a school, having gained consent of rabbis whom he had won over with major donations to charities. The Lippman School was a model institution headed by Professor Lippman, a progressive rabbi from Strasbourg

Strasbourg

Strasbourg is the capital and principal city of the Alsace region in eastern France and is the official seat of the European Parliament. Located close to the border with Germany, it is the capital of the Bas-Rhin département. The city and the region of Alsace are historically German-speaking,...

. After five years, the school closed its doors and Lippman was pressured by the rabbinat, who disagreed with the school's innovative education methods. He trained numerous pupils who took over thereafter.

By 1862, Dr. Allatini led his brother Solomon Fernandez to found an Italian school, thanks to a donation by the Kingdom of Italy. French attempts to introduce the educational network of the Alliance Israélite Universelle

Alliance Israélite Universelle

The Alliance Israélite Universelle is a Paris-based international Jewish organization founded in 1860 by the French statesman Adolphe Crémieux to safeguard the human rights of Jews around the world...

(IAU) failed against resistance by the rabbis, who did not want a Jewish school under the patronage of the French embassy. But the need for schools was so urgent that supporters were finally successful in 1874. Allatini became a member of the central committee of the IAU in Paris and its patron in Thessaloniki. In 1912, nine new IAU schools IAU served the education of both boys and girls from kindergarten to high school; at the same time, the rabbinical seminaries were in decline. As a result, the French language

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

became more widely used within the Jewish community of Salonika and throughout the Jewish world of the Mideast. These schools had instruction in both manual and intellectual training. They produced a generation familiar with the developments of the modern world, and able to enter the workforce of a company in the process of industrialization.

Political and social activism

The eruption of modernity was also expressed by the growing influence of new political ideas from Western Europe. The Young Turk revolution of 1908 with its bases in Salonica proclaimed a constitutional monarchyConstitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy is a form of government in which a monarch acts as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, whether it be a written, uncodified or blended constitution...

. The Jews did not remain indifferent to the enormous social and political change of the era, and were active most often in the social rather than national sphere. As the city began to take in the broader modern influences of the early 20th century, the movement of workers to organize and engage in social struggles for the improvement of working conditions began to spread. An attempt at union of different nationalities within a single labor movement took place with the formation of the Socialist Workers' Federation

Socialist Workers' Federation

The Socialist Workers' Federation , led by Avraam Benaroya, was an attempt at union of different nationalities' workers in Ottoman Thessaloniki within a single labor movement.-The Federation in the Ottoman Empire:...

led by Avraam Benaroya

Avraam Benaroya

Avraam Eliezer Benaroya was a Bulgarian Narrow socialist, leader of the workers' movement in the Ottoman Empire and founder of the Communist Party of Greece....

, a Jew from Bulgaria, who initially started publication of a quadrilingual Journal of the worker aired in Greek, Turkish, Bulgarian and other languages. However, the Balkan context was conducive to division, and affected the movement; after the departure of Bulgarian element, the Federation was heavily composed of Jews.

The Zionist movement thus faced competition for Jewish backing from the Socialist Workers' Federation, which was very antizionist. Unable to operate in the working class, Zionism in Salonica turned to the smaller group of the middle classes and intellectuals.

Salonika, Greek city

First Balkan War

The First Balkan War, which lasted from October 1912 to May 1913, pitted the Balkan League against the Ottoman Empire. The combined armies of the Balkan states overcame the numerically inferior and strategically disadvantaged Ottoman armies and achieved rapid success...

, the Greeks took control of Salonika and eventually integrated the city in their territory. This change of sovereignty was not at first well-received by the Jews, who feared that the annexation would lead to difficulties, a concern reinforced by Bulgarian propaganda, and by the Serbia

Serbia

Serbia , officially the Republic of Serbia , is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, covering the southern part of the Carpathian basin and the central part of the Balkans...

ns, who wanted Austrian Jews to join to their cause. Some Jews fought for the internationalization of the city under the protection of the great European powers, but their proposal received little attention, Europe having accepted the fait accompli. The Greek administration nevertheless took some measures to promote the integration of Jews such as permitting them to work on Sundays and allowing them to observe Shabbat

Shabbat

Shabbat is the seventh day of the Jewish week and a day of rest in Judaism. Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before sunset on Friday evening until a few minutes after when one would expect to be able to see three stars in the sky on Saturday night. The exact times, therefore, differ from...

. The economy benefitted from the annexation, which opened to Salonika the doors of markets in northern Greece and Serbia

Serbia

Serbia , officially the Republic of Serbia , is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, covering the southern part of the Carpathian basin and the central part of the Balkans...

(with which Greece was in alliance), and by the influx of Entente

Allies of World War I

The Entente Powers were the countries at war with the Central Powers during World War I. The members of the Triple Entente were the United Kingdom, France, and the Russian Empire; Italy entered the war on their side in 1915...

troops following the outbreak of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. The Greek government was positive towards the development of Zionism and the establishment of a Jewish home in Palestine, which converged with the Greek desire to dismember the Ottoman Empire. The city received the visit of Zionist leaders, Ben Gurion

Ben Gurion

Ben Gurion can refer to the following persons:* Nicodemus ben Gurion, a Biblical figure, probably a rich Jewish member of the Sanhedrin that felt sympathetic to Jesus Christ...

, Ben Zvi

Yitzhak Ben-Zvi

Yitzhak Ben-Zvi was a historian, Labor Zionist leader, the second and longest-serving President of Israel.-Biography:...

and Jabotinsky who saw in Salonika a Jewish model that should inspire their future state.

At the same time, some amongst the local population at the time did not share their government's view. A witness, Jean Leune, correspondent for L'Illustration during the Balkan wars and then an army officer from the East, says:

Fire of 1917 and inter-communal tensions

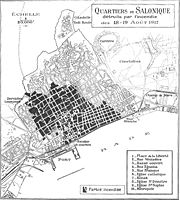

Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917

250px|thumb|The fire as seen from the quay in 1917.250px|thumb|The fire as seen from the [[Thermaic Gulf]].The Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917 was an accidental fire that got out of control and destroyed two thirds of the city of Thessaloniki, second-largest city in Greece, leaving more than...

was a disaster for the community. The Jewish community was concentrated in the lower part of town and was thus the one most affected: the fire destroyed the seat of the Grand Rabbinate

Rabbinate

The term rabbinate may refer to the office of a rabbi or rabbis as a group:*Chief Rabbinate of Israel, the supreme Jewish religious governing body in the state of Israel...

and its archives, as well as 16 of 33 synagogues in the city. Opting for a different course from the reconstruction that had taken place after the fire of 1890, the Greek administration decided on a modern urban redevelopment plan by the Frenchman Ernest Hebrard

Ernest Hebrard

Ernest Hébrard was a French architect, archaeologist and urban planner who completed major projects in Greece, Morocco, and French Indochina. He is mostly renowned for his urban plan for the redevelopment of the center of Thessaloniki in Greece after its Great Fire of 1917.The majority of...

. Therefore it expropriated all land from residents, giving them nevertheless a right of first refusal

Right of first refusal

Right of first refusal is a contractual right that gives its holder the option to enter a business transaction with the owner of something, according to specified terms, before the owner is entitled to enter into that transaction with a third party...

on new housing reconstructed according to a new plan. It was, however, the Greeks who mostly populated the new neighborhoods, while Jews often chose to resettle the city's new suburbs.

Although the first anniversary of the Balfour Declaration of 1917 was celebrated with a splendor unmatched in Europe, the decline had begun. The influx of tens of thousands of Greek refugees

Greek refugees

Greek refugees is a collective term used to refer to the Greeks from Asia Minor who were evacuated or relocated in Greece following the Treaty of Lausanne and the Population exchange between Greece and Turkey...

from Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

, and the departure of Dönme Jews and Muslims from the region as a result of the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922)

Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922)

The Greco–Turkish War of 1919–1922, known as the Western Front of the Turkish War of Independence in Turkey and the Asia Minor Campaign or the Asia Minor Catastrophe in Greece, was a series of military events occurring during the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire after World War I between May...

and the Treaty of Lausanne

Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne was a peace treaty signed in Lausanne, Switzerland on 24 July 1923, that settled the Anatolian and East Thracian parts of the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire. The treaty of Lausanne was ratified by the Greek government on 11 February 1924, by the Turkish government on 31...

(1923), significantly changed the ethnic composition of the city. The Jews ceased to constitute an absolute majority and, on the eve of the Second World War, they accounted for just 40% of the population.

During the period, a segment of the population began to demonstrate an increasingly less conciliatory policy towards the Jews. The Jewish population reacted by siding with the Greek monarchists during the Greek National Schism (opposing Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Venizelos was an eminent Greek revolutionary, a prominent and illustrious statesman as well as a charismatic leader in the early 20th century. Elected several times as Prime Minister of Greece and served from 1910 to 1920 and from 1928 to 1932...

, who had the overwhelming support of refugees and the lower income classes). This would set the stage for a 20-year period during which the relationship of the Jews with the Greek state and people would oscillate as Greek politics changed.

In 1922, work was banned on Sunday (forcing Jews to either work on Shabbat

Shabbat

Shabbat is the seventh day of the Jewish week and a day of rest in Judaism. Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before sunset on Friday evening until a few minutes after when one would expect to be able to see three stars in the sky on Saturday night. The exact times, therefore, differ from...

or lose income), posters in foreign languages were prohibited, and the authority of rabbinical courts to rule on commercial cases was taken away. As in countries such as Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

and Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

, a significant current of anti-Semitism grew in inner

Inner city

The inner city is the central area of a major city or metropolis. In the United States, Canada, United Kingdom and Ireland, the term is often applied to the lower-income residential districts in the city centre and nearby areas...

Salonica, but "never reached the level of violence in these two countries". It was very much driven by Greek arrivals from Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

, mostly poor and in direct competition with Jews for housing and work. This current of sentiment was, nevertheless, relayed by the Makedonia

Makedonia (newspaper)

Makedonia is a Greek daily newspaper published in Thessaloniki. Being one of the oldest newspapers in Greece, it was first published in 1911 by Konstantinos Vellidis. The present owner is the company Makedoniki Ekdotiki Ektipotiki AE. Currently, director of the newspaper is Dimitrios Gousidis, the...

daily and the National Union of Greece

National Union of Greece

The National Union of Greece was an anti-Semitic nationalist party established in Thessaloniki, Greece, in 1927.Registered as a mutual aid society, the EEE was founded by Asia Minor refugee merchants. According to the organisation's constitution, only Christians could join...

(Ethniki Enosis Ellados, EEE) ultra-nationalist organization, which was close to Venizelos' Liberal Party (in power on and off during the thirties), accusing the Jewish population of not wanting to blend in with the Greek nation, and viewing the development of Communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

and Zionism

Zionism

Zionism is a Jewish political movement that, in its broadest sense, has supported the self-determination of the Jewish people in a sovereign Jewish national homeland. Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Zionist movement continues primarily to advocate on behalf of the Jewish state...

in the community with suspicion. Venizelist Greek governments themselves largely adopted an ambivalent attitude, pursuing a policy of engagement while not distancing themselves unequivocally from the current of anti-Semitism.

In 1931, an antisemitic riot took place in Camp Campbell, where a Jewish neighborhood was completely burned, leaving 500 families homeless and one Jewish resident dead.

Under Metaxas

The seizure of power by dictator Ioannis MetaxasIoannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas was a Greek general, politician, and dictator, serving as Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941...

in 1936 too had a significant bearing on the pattern of Greek-Jewish relations in Thessaloniki. Metaxas' regime was not at all anti-Semitic; it perceived the Venizelists and the Communists as its political enemies, and the Bulgarians

Bulgarians

The Bulgarians are a South Slavic nation and ethnic group native to Bulgaria and neighbouring regions. Emigration has resulted in immigrant communities in a number of other countries.-History and ethnogenesis:...

as its major foreign enemy. This endeared Metaxas to influential Jewish groups: the upper/middle classes which felt threatened by organized labor and the socialist movement. Antisemitic organizations and publications were banned and support for the regime was sufficiently strong for a Jewish charter of the regime-sponsored National Organisation of Youth

National Organisation of Youth

thumb|The emblem of EON.thumb|The flag of EON.The National Youth Organisation was a fascist youth organization in the Kingdom of Greece during the years of the Metaxas Regime . It was established some time in 1937 and was disbanded with the start of the German occupation of Greece...

(EON) to be formed. This reinforced the trend of national self-identification as Greeks among the Jews of Salonika, who had been Greek citizens since 1913. Even in the concentration camps, Greek Jews never ceased to affirm their sense of belonging to the Greek nation.

At the same time, the working-class poor of the Jewish community had joined forces with their Christian counterparts in the labor movement that developed in the 1930s, often the target of suppression during Metaxas' regime. Avraam Benaroya

Avraam Benaroya

Avraam Eliezer Benaroya was a Bulgarian Narrow socialist, leader of the workers' movement in the Ottoman Empire and founder of the Communist Party of Greece....

was a leading figure in the Greek Socialist Movement, not only among Jews, but on a national level. Thus the forces of the period had worked to bridge the gaps between Christians and Jews, while creating new tensions among the different socioeconomic groups within the city and the country as a whole.

Emigration

Emigration of Jews from the city began when the Young TurksYoung Turks

The Young Turks , from French: Les Jeunes Turcs) were a coalition of various groups favouring reformation of the administration of the Ottoman Empire. The movement was against the absolute monarchy of the Ottoman Sultan and favoured a re-installation of the short-lived Kanûn-ı Esâsî constitution...

pushed through the universal conscription

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

of all Ottoman subjects into the military irrespective of religion, a trend that continued to grow after the annexation of the city by Greece. Damage from the Thessaloniki fire, poor economic conditions, rise in anti-Semitism amongst a segment of the population, and the development of Zionism all motivated the departure of part of the city's Jewish population. This group left mainly for Western Europe

Western Europe

Western Europe is a loose term for the collection of countries in the western most region of the European continents, though this definition is context-dependent and carries cultural and political connotations. One definition describes Western Europe as a geographic entity—the region lying in the...

, South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

and Palestine

Palestine

Palestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands....

. The jewish population consequently decreased from 93,000 people to 53,000 on the eve of the war. There were some notable successes amongst the community's diaspora. Isaac Carasso

Isaac Carasso

The Carasso family was a prominent Sephardic Jewish family in Ottoman Selanik...

, reaching Barcelona

Barcelona

Barcelona is the second largest city in Spain after Madrid, and the capital of Catalonia, with a population of 1,621,537 within its administrative limits on a land area of...

, founded the Danone company. Maurice Abravanel

Maurice Abravanel

Maurice Abravanel was aSwiss-American Jewish conductor of classical music. He is remembered as the conductor of the Utah Symphony Orchestra for over 30 years.-Life:...

went to Switzerland with his family and then to the United States where he became a famous conductor

Conducting

Conducting is the art of directing a musical performance by way of visible gestures. The primary duties of the conductor are to unify performers, set the tempo, execute clear preparations and beats, and to listen critically and shape the sound of the ensemble...

. A future grandparent of the French President

President of the French Republic

The President of the French Republic colloquially referred to in English as the President of France, is France's elected Head of State....

Nicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Sarkozy is the 23rd and current President of the French Republic and ex officio Co-Prince of Andorra. He assumed the office on 16 May 2007 after defeating the Socialist Party candidate Ségolène Royal 10 days earlier....

emigrated to France. In the interwar years, some Jewish families were to be found in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, France; The seat of their association was located on the Rue La Fayette. In Palestine, the Recanati family established one of the most important banks of Israel, the Eretz Yisrael Discount Bank which later became the Israel Discount Bank

Israel Discount Bank

Israel Discount Bank Ltd. , I.D.B., is one of Israel's three largest banks, with 260 branches, and assets of 171 billion NIS .-History:...

.

Battle of Greece

On 28 October 1940, Italian forces invaded Greece following the refusal of the Greek dictator Ioannis MetaxasIoannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas was a Greek general, politician, and dictator, serving as Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941...

to accept the ultimatum given by the Italians. In the resulting Greco-Italian War

Greco-Italian War

The Greco-Italian War was a conflict between Italy and Greece which lasted from 28 October 1940 to 23 April 1941. It marked the beginning of the Balkans Campaign of World War II...

and the subsequent German invasion

Battle of Greece

The Battle of Greece is the common name for the invasion and conquest of Greece by Nazi Germany in April 1941. Greece was supported by British Commonwealth forces, while the Germans' Axis allies Italy and Bulgaria played secondary roles...

, many of Thessaloniki's Jews took part. 12,898 men enlisted in the Greek army; 4,000 participated in the campaigns in Albania and Macedonia; 513 fought with the Germans and, in total, 613 Jews were killed, including 174 from Salonika. The 50th Brigade of Macedonia was nicknamed "Cohen Battalion", reflecting the preponderance of Jews in its composition. After the defeat of Greece, many Jewish soldiers had their feet frozen returning home on foot.

Occupation

Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 were antisemitic laws in Nazi Germany introduced at the annual Nuremberg Rally of the Nazi Party. After the takeover of power in 1933 by Hitler, Nazism became an official ideology incorporating scientific racism and antisemitism...

would not apply to Salonika. The Jewish press was quickly banned, while two pro-Nazi Greek dailies, Nea Evropi ("New Europe") and Apogevmatini ("Evening Press"), appeared. Some homes and community buildings were requisitioned by the occupying forces, including the Baron Hirsch Hospital. In late April, signs prohibiting Jews entry to cafés appeared. Jews were forced to turn in their radios.

The Grand Rabbi of Salonica, Zvi Koretz, was arrested by the Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

on 17 May 1941 and sent to a concentration camp near Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

, from where he returned in late January 1942 to resume his position as rabbi. In June 1941, commissioner Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Rosenberg

' was an early and intellectually influential member of the Nazi Party. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart; he later held several important posts in the Nazi government...

arrived. He plundered Jewish archives, sending tons of documents to his pet-project, the Institut zur Erforschung der Judenfrage ("Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question") in Frankfurt.

Along with the other Greek urban communities, the Jews suffered a severe famine in the winter of 1941-42. The Nazi regime had not attached any importance to the Greek economy, food production or distribution. It is estimated that in 1941-1942 sixty Jews of the city died every day from hunger.

For a year, no further antisemitic action was taken. The momentary reprieve gave the Jews a temporary sense of security.

On a Shabbat

Shabbat

Shabbat is the seventh day of the Jewish week and a day of rest in Judaism. Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before sunset on Friday evening until a few minutes after when one would expect to be able to see three stars in the sky on Saturday night. The exact times, therefore, differ from...

in July 1942, all the men of the community aged 18 to 45 years were rounded up in the Plateia Eleftherias. Throughout the afternoon, they were forced to do humiliating physical exercises at gunpoint. Four thousand of them were ordered to construct a road for the Germans, linking Thessaloniki to Kateríni

Katerini

Katerini is a town in Central Macedonia, Greece, the capital of Pieria regional unit. It lies on the Pierian plain, between Mt. Olympus and the Thermaikos Gulf, at an altitude of 14 m. The town, which is one of the newest in Greece, has a population of 83,764...

and Larissa

Larissa

Larissa is the capital and biggest city of the Thessaly region of Greece and capital of the Larissa regional unit. It is a principal agricultural centre and a national transportation hub, linked by road and rail with the port of Volos, the city of Thessaloniki and Athens...

, a region rife with malaria

Malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

.

In less than ten weeks, 12% of them died of exhaustion and disease. In the meantime, the Thessalonikan community, with the help of Athens, managed to gather two billion drachmas towards the sum of 3.5 billion drachmas demanded by the Germans to ransom the forced laborers. The Germans agreed to release them for the lesser sum but, in return, demanded that the Greek authorities abandon the Jewish cemetery in Salonika, containing 300,000 to 500,000 graves. Its size and location, they claimed, had long hampered urban growth.

The Jews transferred land in the periphery on which there were two graves. The municipal authorities, decrying the slow pace of the transfer, took matters into their own hands. Five hundred Greek workers, paid by the municipality, began with the destruction of tombs. The cemetery was soon transformed into a vast quarry where Greeks and Germans sought gravestones for use as construction materials. Today this site is occupied by the Aristotle University

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki

The Aristotle University of Thessaloniki is the largest Greek university, and the largest university in the Balkans. It was named after the philosopher Aristotle, who was born in Stageira, Chalcidice, about 55 km east of Thessaloniki, in Central Macedonia...

and other buildings.

It is estimated that from the beginning of the occupation to the end of deportations, 3,000-5,000 Jews managed to escape from Salonika, finding temporary refuge in the Italian zone. Of these, 800 had or obtained documents proving Italian citizenship and throughout the period of Italian occupation were actively protected by consular authority. 800 Jews fled to the Macedonian mountainsides, joining the Greek Communist Resistance, ELAS. Few Jews joined its royalist counterpart.

Destruction of the Jews of Salonika

Deportation

To carry out this operation, the Nazi authorities dispatched two specialists in the field, Alois BrunnerAlois Brunner

Alois Brunner is an Austrian Nazi war criminal. Brunner was Adolf Eichmann's assistant, and Eichmann referred to Brunner as his "best man." As commander of the Drancy internment camp outside Paris from June 1943 to August 1944, Brunner is held responsible for sending some 140,000 European Jews to...

and Dieter Wisliceny

Dieter Wisliceny

Dieter Wisliceny was a member of the Nazi SS, and a key executioner in the final phase of the Holocaust.Wisliceny studied theology without obtaining a degree...

, who arrived on February 6, 1943. They immediately applied the Nuremberg laws

Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 were antisemitic laws in Nazi Germany introduced at the annual Nuremberg Rally of the Nazi Party. After the takeover of power in 1933 by Hitler, Nazism became an official ideology incorporating scientific racism and antisemitism...

in all their rigor, imposing the display of the yellow badge

Yellow badge

The yellow badge , also referred to as a Jewish badge, was a cloth patch that Jews were ordered to sew on their outer garments in order to mark them as Jews in public. It is intended to be a badge of shame associated with antisemitism...

and drastically restricting the Jews' freedom of movement. Toward the end of February 1943, they were rounded up in three ghetto

Ghetto

A ghetto is a section of a city predominantly occupied by a group who live there, especially because of social, economic, or legal issues.The term was originally used in Venice to describe the area where Jews were compelled to live. The term now refers to an overcrowded urban area often associated...

s (Kalamaria, Singrou and Vardar / Agia Paraskevi) and then transferred to a transit camp, called the Baron Hirsch ghetto

Baron Hirsch ghetto

The Baron Hirsch ghetto or Baron Hirsch camp was a German transit camp in Thessaloniki, Greece....

or camp, which was adjacent to a train station. There, the death trains were waiting. To accomplish their mission, the SS relied on a Jewish police created for the occasion, led by Vital Hasson, which was the source of numerous abuses against the rest of the Jews.

The first convoy departed on March 15. Each train carried 1000-4000 Jews across the whole of central Europe

Central Europe

Central Europe or alternatively Middle Europe is a region of the European continent lying between the variously defined areas of Eastern and Western Europe...

, mainly to Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp

Concentration camp Auschwitz was a network of Nazi concentration and extermination camps built and operated by the Third Reich in Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany during World War II...

. A convoy also left for Treblinka, and it is possible that deportation to Sobibor

Sobibór extermination camp

Sobibor was a Nazi German extermination camp located on the outskirts of the town of Sobibór, Lublin Voivodeship of occupied Poland as part of Operation Reinhard; the official German name was SS-Sonderkommando Sobibor...

took place, since Salonican Jews were liberated from that camp. The Jewish population of Salonika was so large that the deportation took several months until it was completed, which occurred on August 7 with the deportation of Chief Rabbi Tzvi Koretz and other notables to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp

Bergen-Belsen concentration camp

Bergen-Belsen was a Nazi concentration camp in Lower Saxony in northwestern Germany, southwest of the town of Bergen near Celle...

, under relatively good conditions. In the same convoy were 367 Jews protected by their Spanish nationality, who had a unique destiny: they were transferred from Bergen-Belsen to Barcelona

Barcelona

Barcelona is the second largest city in Spain after Madrid, and the capital of Catalonia, with a population of 1,621,537 within its administrative limits on a land area of...

, and then Morocco

Morocco

Morocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

, with some finally reaching the British Mandate of Palestine.

Factors explaining the effectiveness of the deportations

Judenrat

Judenräte were administrative bodies during the Second World War that the Germans required Jews to form in the German occupied territory of Poland, and later in the occupied territories of the Soviet Union It is the overall term for the enforcement bodies established by the Nazi occupiers to...

, and of its leader in the period prior to the deportations, the chief rabbi Zvi Koretz, has been heavily criticized. He was accused of having responded passively to the Nazis and downplayed the fears of Jews when their transfer to Poland was ordered. As an Austrian citizen and therefore a native German speaker, he was thought to be well-informed. There was a rumor that accused him of having knowingly collaborated with the occupiers. A recent study, however tends to diminish his role in the deportations.

Another factor was the solidarity shown by the families who refused to be separated. This desire undermined individual initiatives. Some older Jews also had difficulty remaining in hiding because of their lack of knowledge of the Greek language, which had only become the city's dominant language after annexation by Greece in 1913. Additionally, the large size of the Jewish population rendered impossible the tactic of blending into the Greek Orthodox population, as in Athens.

Again in contrast to Athens, there was also a latent anti-Semitism amongst a segment of the Greek population, in particular among the refugees from Asia Minor. When these immigrants arrived en masse in Salonica, they were excluded from the economic system. Consequently, some of these outcasts watched the Jewish population with hostility. The Jewish people were more economically integrated and therefore better off, which the immigrants equated with the former Ottoman power. Nevertheless, the Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem is Israel's official memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, established in 1953 through the Yad Vashem Law passed by the Knesset, Israel's parliament....

has identified 265 Greek righteous among the nations

Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous among the Nations of the world's nations"), also translated as Righteous Gentiles is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from extermination by the Nazis....

, the same proportion as among the French population.

In the camps

At Birkenau, about 37,000 Salonicans were gassed immediately, especially women, children and the elderly. Nearly a quarter of all 400 experiments perpetrated on the Jews were on Greek Jews, especially those from Salonika. These experiments included emasculation and implantation of cervical cancerCervical cancer

Cervical cancer is malignant neoplasm of the cervix uteri or cervical area. One of the most common symptoms is abnormal vaginal bleeding, but in some cases there may be no obvious symptoms until the cancer is in its advanced stages...

in women. Most of the twins died following atrocious crimes. Others from the community last worked in the camps. In the years 1943-1944, they accounted for a significant proportion of the workforce of Birkenau, making up to 11,000 of the labourers. Because of their unfamiliarity with Yiddish, Jews from Greece were sent to clean up the rubble of the Warsaw Ghetto

Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest of all Jewish Ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II. It was established in the Polish capital between October and November 15, 1940, in the territory of General Government of the German-occupied Poland, with over 400,000 Jews from the vicinity...

in August 1943 in order to build a camp. Among the 1,000 Salonican Jews employed on the task, a group of twenty managed to escape from the ghetto and join the Polish resistance, the Armia Krajowa

Armia Krajowa

The Armia Krajowa , or Home Army, was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II German-occupied Poland. It was formed in February 1942 from the Związek Walki Zbrojnej . Over the next two years, it absorbed most other Polish underground forces...

, which organized the Warsaw Uprising

Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance Home Army , to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany. The rebellion was timed to coincide with the Soviet Union's Red Army approaching the eastern suburbs of the city and the retreat of German forces...

.

Many Jews from Salonika were also integrated into the Sonderkommando

Sonderkommando

Sonderkommandos were work units of Nazi death camp prisoners, composed almost entirely of Jews, who were forced, on threat of their own deaths, to aid with the disposal of gas chamber victims during The Holocaust...

s. On 7 October 1944, they attacked German forces with other Greek Jews, in an uprising planned in advance, storming the crematoria and killing about twenty guards. A bomb was thrown into the furnace of the crematorium III, destroying the building. Before being massacred by the Germans, insurgents sang a song of the Greek partisan movement and the Greek National Anthem

Hymn to Freedom