Alexandru Averescu

Encyclopedia

Alexandru Averescu was a Romania

n marshal and populist

politician. A Romanian Armed Forces

Commander during World War I

, he served as Prime Minister of three separate cabinets (as well as being interim Foreign Minister in January–March 1918 and Minister without portfolio

in 1938). He first rose to prominence during the peasant's revolt of 1907

, which he helped repress in violence. Credited with engineering the defense of Moldavia

in the 1916–1917 Campaign

, he built on his popularity to found and lead the successful People's Party, which he brought to power in 1920–1921, with backing from King

Ferdinand I

and the National Liberal Party

(PNL), and with the notable participation of Constantin Argetoianu

and Take Ionescu

.

His controversial first mandate, marked by a political crisis and oscillating support from the PNL's leader Ion I. C. Brătianu

, played a part in legislating land reform

and repressed communist

activities, before being brought down by the rally of opposition forces. His second term of 1926–1927 brought a much-debated treaty with Fascist Italy

, and fell after Averescu gave clandestine backing to the ousted Prince Carol

. Faced with the People Party's decline, Averescu closed deals with various right-wing forces and was instrumental in bringing Carol back to the throne in 1930. Relations between the two soured over the following years, and Averescu clashed with his fellow party member Octavian Goga

over the king's attitudes. Shortly before his death, he and Carol reconciled, and Averescu joined the Crown Council.

Averescu, who authored over 12 works on various military topics (including his memoirs from the frontline), was also an honorary member of the Romanian Academy

and an Order of Michael the Brave

recipient. He became a Marshal of Romania in 1930.

, now part of Ukraine

. The son of Constantin Averescu, who held the rank

of sluger

, he studied at the Romanian Orthodox

seminary

in Izmail, then at the School of Arts and Crafts in Bucharest

(intending to become an engineer

). In 1876, he decided to join the Gendarmes

in Izmail.

Seeing action as a cavalry

sergeant with the Romanian troops engaged in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878

, he was decorated on several occasions, but was later moved to reserve (after failing his medical examination due to the effects of frostbite

). He was, however, reinstated later in 1878, and subsequently received a military education in Romania, at the military school of Târgovişte

(Dealu Monastery

), and in Italy

, at the Military Academy of Turin

. Averescu married an Italian opera

singer, Clotilda Caligaris, who had been the prima donna

of La Scala

. His future collaborator and rival Constantin Argetoianu

stated that Averescu "chose Mrs. Clotilda at random".

Upon his return, Averescu steadily climbed through the ranks. He was head of the Bucharest Military Academy (1894–1895), and, in 1895-1898, Romania's military attaché

in the German Empire

; a colonel in 1901, he was advanced to the rank of Brigadier General

and became head of the Tecuci

regional Army Command Center in 1906.

Before the World War, he led the troops in crushing the 1907 peasants' revolt

— where he engaged in using very harsh means of repression, especially when dealing with soldiers who refused to fight against the rebels — and was subsequently Minister of War in Dimitrie Sturdza

's National Liberal Party

(PNL) cabinet (1907–1909). According to the recollections of Eliza Brătianu, a split occurred between him and the PNL after Averescu attempted to advance various political goals — the conflict erupted when he sought support with King

Carol I

and then, as the National Liberals deeply resented Romania's alliance with the Central Powers

, he approached the Germans for backing.

Subsequently, he was commander of the First Infantry Division (stationed in Turnu Severin

) and, later, of the Second Army Corps in Craiova

. In 1912, he became a Major General

, and, in 1911-1913, he was Chief of the General Staff. In the latter capacity, Averescu organized the actions of Romanian troops operating south of the Danube

in the Second Balkan War

(the campaign against Bulgaria

, during which his troops met no resistance).

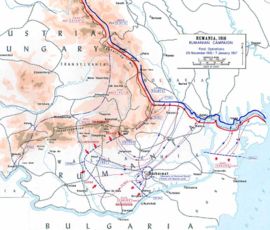

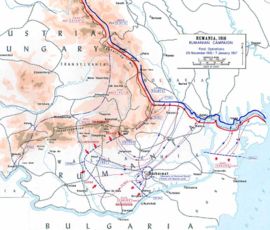

, and was then moved to the head of the Third Army (following the latter's defeat in the Battle of Turtucaia

). He commanded Army Group South in the Flămânda operation

against the Third Bulgarian Army and other forces of the Central Powers

, ultimately stopped by the German offensive (Averescu's forces did not register important losses, and orderly retreated to Moldavia

, where Romanian authorities had taken refuge from the successful German operations).

Promoted Lieutenant General

at 1 January 1917, Averescu again led the Second Army to victory in the Battles of Mărăşti

and Mărăşeşti

(August 1917); his achievements, including his brief breakthrough at Mărăşti, were considered impressive by public opinion and his officers. However, several military historians rate Averescu and his fellow Romanian generals very poorly, arguing that, overall, their direction of the war "could not have been worse". Despite controlling an army of 500,000 plus 100,000 Russian reinforcements, they were soundly defeated by a much smaller German-Austrian

-Bulgarian army in less than four months of combat.

Averescu was widely seen as the person behind a relatively successful resistance to further offensives on Moldavia

(the single piece of territory still held by the Romanian state), and he was considered by many of his contemporaries to have stood in contrast to the what was seen as endemic corruption and incompetence. The state of affairs, together with the October Revolution

in Russia, was to be blamed for the eventual Romanian surrender to the Central Powers; promoted Premier by King

Ferdinand I

during the period of crisis, Averescu began armistice

talks with August von Mackensen

in Buftea

and Focşani

, but was vehemently opposed to the terms — he resigned, leaving the Alexandru Marghiloman

cabinet when it signed the Treaty of Bucharest

. Despite Averescu's talks yielding no result, he was repeatedly attacked by his political adversaries for having initiated them.

During the period, he also faced a Russian Bolshevik

During the period, he also faced a Russian Bolshevik

military action: just before Averescu came to power, as Russia's Leon Trotsky

negotiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

with Germany, the Rumcherod

administrative body in Odessa

, led by Christian Rakovsky

, ordered an offensive from the east into Romania. In order to prevent further losses, Averescu signed his name to a much-criticized temporary armistice with the Rumcherod; eventually, Rakovsky was himself faced with a German offensive (sparked by the temporary breakdown of negotiations at Brest-Litovsk), and had to abandon both his command and the base in Odessa.

(PNL) and its leader Ion I. C. Brătianu

.

He presided over the People's Party (initially named People's League), and he was immensely popular especially among peasants after the end of the war. His force had an appealing populist

message, translated into vague promises and relying on the image of the General: peasants had been promised land at the beginning of the war (and they were being rewarded with it at the very moment, through an agrarian reform

that reached its full scope in 1923); they had formed the larger part of the Army, and had come to see Averescu as the one to fulfill their expectations, as well as a figure who was still commanding their allegiance. Eliza Brătianu, the PNL leader's wife, placed Averescu's ascension in the context of Greater Romania

's creation through the addition of Bessarabia

, Bukovina

, and Transylvania

(while making use of the condescending National Liberal tone towards the Romanian National Party

that was emerging triumphant in previously Austro-Hungarian

Transylvania):

As the movement initially tended to describe itself as a social trend rather than a political party

, it also attracted former members of the Conservative Party

(such as Constantin Argetoianu

, Constantin Garoflid, and Take Ionescu

), military men such as Constantin Coandă

, the Democratic Nationalist Party leader A. C. Cuza

, the notorious supporters of dirigisme

Mihail Manoilescu

and Ştefan Zeletin, the moderate nationalist

Duiliu Zamfirescu

, the future diplomat Citta Davila, the journalist D. R. Ioaniţescu, the left-wing agrarianist

Petru Groza

, the Bukovinan leader Iancu Flondor

, and the lawyer Petre Papacostea. Additional support came from Transylvanian activists such as Octavian Goga

and Teodor Mihali, who had previously left the Romanian National Party

there in protest over the policies of its president Iuliu Maniu

. Nevertheless, the People's Party did attempt to approach Maniu for an alliance at various intervals after summer 1919 (according to Argetoianu, their attempts were frustrated by King

Ferdinand I

, whose relationship with Maniu was cordial at the time, and who allegedly stated "Maniu is no one else's! Maniu is mine!").

The grouping also established close links with Garda Conştiinţei Naţionale (GCN, "The National Awareness Guard"), a reactionary

group formed by the electrician Constantin Pancu, engaged in violence against communist

activists in Iaşi

(the latter were feared by Averescu as well). Nevertheless, in late 1919, Averescu and Argetoianu approached the Socialist Party of Romania

and its associate, the Social Democratic Party of Transylvania and Banat, with an offer for collaboration, negotiating the matter with the parties' reformist

leaders — Ioan Flueraş

, Ilie Moscovici, and Iosif Jumanca. At the time, Argetoianu claimed, his conversations with Moscovici revealed the fact that the latter was growing suspicious of the party's far left

wing, where "the blanket-maker Cristescu

and others were agitating". Averescu proposed merging the two parties, as a distinct section, into the People's Party; he was refused, and talks broke down when the general expected the Socialists to support his electoral platform.

rebel soldier Georges Boulanger

), several voices inside his movement called on Averescu to lead a republican

coup d'état

against King Ferdinand and her husband — a move allegedly prevented only by the general's loyalism. Argetoianu, who admitted that "I shook hands with Averescu [...] expecting a dictatorial regime", claimed that, during his stay in Italy, the general had been decisively influenced by Radicalism

and the Risorgimento

movement. This, in Argetoianu's view, was the cause for his repeated involvement in conspiracies

; he recalled that, in 1919, Davila's house was the scene of regular reunion of officers, who plotted Brătianu's ousting and pondered dethroning the king (in this version of events, Averescu initially accepted to be proclaimed dictator, but, around October of that year, called on conspirators to renounce their plan).

Aiming to answer most of Romania's social and political issues, the League's founding document called for:

According to Argetoianu,

Although he was also Prime Minister of Romania for three mandates (1918, 1920–1921, 1926–1927), his political success is not as spectacular as the military one. Averescu ended up as one of the pawns maneuvered by Brătianu. Argetoianu later repeatedly expressed his distaste for Averescu's hesitant stance and openness to compromise.

Romanian National Party

(PNR)-Peasants' Party

(PŢ) cabinet; the National Liberals managed to obtain the general's renunciation of his goal to prosecute their party for alleged mis-management of Romania before and during the war, as well as his promise to respect the 1866 Constitution of Romania

when carrying out the planned land reform

. At the same time, Brătianu kept a tight relationship with King Ferdinand.

On March 13, 1920, he gave news of the Vaida-Voevod cabinet's dissolution, and was widely expected to call for early elections as soon as this had happened. Instead, he read a document convened with King Ferdinand, which suspended Parliament

(the first legislative body in Greater Romania

) for ten days — the measure was intended to give Averescu the time to negotiate a new majority in the chambers. These moves caused a vocal response from the opposition: Nicolae Iorga

, who was president of the Chamber of Deputies

and sided with the National Party, called for a motion of no confidence

to be passed on March 26; in return, Averescu obtained the support of the monarch in dissolving the Parliament, and invested his cabinet's energies into winning the early elections by enlisting the help of county

-level officials (local administration came to be dominated by People's Party officials). It carried the vote with 206 seats (223 together with Take Ionescu

's Conservative-Democratic Party).

As agreements between the PNR and PŢ broke down (with the PNR awaiting for new developments), the PŢ joined Iorga's party, the Democratic Nationalists, in creating the Federation of National-Social Democracy (which also drew support from the group around Nicolae L. Lupu

).

with Hungary

, and initial steps leading to the creation of the Little Entente

- formed by Romania with Czechoslovakia

and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

. It was also at this stage that Romania and the Second Polish Republic

inaugurated their military alliance (see Polish-Romanian Alliance

). The goal to create a cordon sanitaire

against Bolshevist Russia

also brought him and his Minister of the Interior Argetoianu to oversee repression measures against the group of Socialist Party of Romania

members who voted in favor of joining the Comintern

(arrested on suspicion of "attempt against the state's security" on May 12, 1921). This came after a long debate in Parliament over the imprisonment of Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor, a Romanian citizen who had joined the Russian Red Army

in Bessarabia

during the later stages of the October Revolution

, and who had been tried for treason

. Argetoianu, who proclaimed communism to be "over in Romania", later indicated that Averescu and other members of the cabinet were hesitant about the crackdown, and that he ultimately resorted to taking initiative for the arrests — thus presenting his fellow politicians with a fait accompli

.

The regions coming under Romania's administration at the end of the war still maintained their ad hoc

administrative structures, including the Transylvania

n Directory Council, set up and dominated by the PNR; Averescu ordered these dissolved in April, facing protest from local notabilities. At the same time, he ordered all troops to be demobilized

. He unified currency around the Romanian leu

, and imposed a land reform

in the form in which it was to be carried out by the new Brătianu executive. In fact, the latter measure had been imposed by the outgoing PNL cabinet through the order of Ion G. Duca

, in a manner which Argetoianu described as "destructive". As an initial step, Averescu's government appointed the noted activist Vasile Kogălniceanu, a deputy for Ilfov County

, as rapporteur

; Kogălniceanu used this position to give an account of the agrarian situation in Romania, stressing the role played by his ancestor, Constantin, in abolishing Moldavia

n serfdom

, as well as that of his father, Mihail Kogălniceanu

, in eliminating corvée

s throughout Romania.

The People's Party found itself hard pressed to limit the effects of the reform as promised by Duca — reason why Constantin Garoflid, seen by Argetoianu as "the Conservative and theorist of large-scale landed property

", was promoted as Minister of Agriculture. Argetoianu also accused the Premier of endorsing reform in an even more radical shape, and contended that:

In October 1920, Averescu reached an agreement with the Allied Powers

, recognizing Bessarabia's union with Romania — expressing a hope for the Bolshevik government to be overthrown, it also imposed the region's cession on a projected democratic government in Russia (while calling for further negotiations between it and Romania); throughout the interwar period

, the Soviet Union

refused to bind itself to the provisions of the agreement. Italy

also refused to ratify

the document, citing, alongside various foreign interests (including its friendship with the Soviet Union), the 250 million Italian lire

owed to Italian investors in Romanian state bonds

.

Romanian war bond

s that he had illegally obtained from the Finance Ministry reserve.

With Nicolae Titulescu

as Finance Minister, Averescu resumed the interventionist

course in economic policies, but broke with tradition when he attempted to legislate a major increase in taxes and proposed nationalization

s — with potential negative effects on the PNL-voting middle class

. The National Liberals, through the voice of Alexandru Constantinescu-Porcu, helped exploit the rivalry between the Peasants' Party and Iorga, using the latter's rejection of Constantin Stere

(a conflict sparked by Stere's support for Germany during the World War); Stere won partial elections for the deputy seat in Soroca

, Bessarabia, causing a political scandal which saw all parties (including the PNR) declare their dissatisfaction. The conflict worsened during a prolonged parliamentary debate over Averescu's proposal to nationalize enterprises in Reşiţa

(an initiative the opposition mistrusted, alleging that the new owners were to be People's Party members), when Argetoianu addressed a mumbled insult to the Peasant Party's Virgil Madgearu

. Ion G. Duca

of the PNL expressed his sympathies to Madgearu (who had repeated out an obscene word whispered by Argetoianu), and all opposition groups appealed to Ferdinand, asking for Averescu's recall (July 14, 1921).

Ferdinand then attempted to facilitate a fusion between the Romanian National Party

and the National Liberals, but negotiations broke down after disagreements over the possible leadership. Eventually, Brătianu convened with Ferdinand his return to power, and the king called on Foreign Minister Take Ionescu

to resign, thus causing a political crisis that profited the PNL and put an end to the Averescu cabinet.

Shows of popular support in Bucharest

were called of by Averescu himself, after he had negotiatied with Brătianu for a People's Party cabinet to be formed "at a proper time". Ionescu took over as premier until late January 1922, when he was replaced by Brătianu.

and nominated Averescu as premier (with PNL support).

Averescu's party was instead joined by PNR dissidents, Vasile Goldiş

and Ioan Lupaş

, who represented a Romanian Orthodox

segment of the Transylvanian voters (rather than the Greek Catholics

supporting Iuliu Maniu

). The 1926 elections, which Averescu's cabinet organized in March and won with a landslide (269 mandates) also brought a massive defeat for the PNL, who held just 16 seats in the Chamber of Deputies.

itself, the new government he formed displayed gestures of friendship towards Benito Mussolini

's Fascist Italy

, a state which advertised itself as a rising force — The Nation called Averescu "Romania's Mussolini", as "an epithet which the new premier of Rumania bestowed upon himself". Contacts established (as early as a June 1926, when Mihail Manoilescu

had negotiated a loan in Rome

) were one of the major points of divergence between the policies of Averescu and those of Brătianu: the former attempted to overcome the embarrassment provoked by Mussolini when, due to Romania's debt, the Italian government had recalled the ambassador and had refused to permit King Ferdinand's pre-convened visit.

The loan convened by Manoilescu and Mussolini made important concessions to Italy in return for a clarification of Romania's debt status; it also led to the signing of a five-year Friendship Treaty (September 16), widely condemned by Romanian public opinion for not having called on Italy to state its support for Romanian rule in Bessarabia

, and created tension inside the Little Entente

(Yugoslavia

feared that Italy had attempted to gain Romania's neutrality in case of a potential irredentist

conflict). Writing at the time, Constantin Vişoianu

also criticized the vague terms in which the sections of the document dealing with mutual defense had been drafted:

The treaty expired in 1932, and, after being prolonged by six months, it was not renewed. Overall, the political impact of contacts was minor, given that the Italians mistrusted the Romanian movement for its traditional role as instrument for Brătianu. Referring to the parallel project to marry Princess Ileana

to Prince Umberto of Italy

, Averescu himself allegedly stated: "I didn't get much from Italy except a throne for a Princess of Rumania".

groups (especially to the National-Christian Defense League

formed by A. C. Cuza

, his early collaborator), and probably considered assuming dictatorial powers.

The cabinet clashed with Brătianu when it was discovered that it had been negotiating in secret with the disinherited Prince Carol

(a traditional adversary of the PNL) as Ferdinand's health was taking a turn for the worse (Averescu later claimed that he had been asked by Brătianu: "So, after I have brought you to power, you wish to rise and dominate?"). The PNL withdrew its support, and, through an order signed by Constantin Hiott, Averescu's was replaced by the broad coalition government of Barbu Ştirbey

, Brătianu's brother-in-law. The general's deposition, confirmed by King Ferdinand on his deathbed, created a vacuum on the Right, soon filled by the Iron Guard

, a fascist movement formed by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu

(formerly an associate of Cuza's).

and Prince Nicholas

' regency

. In November 1927, Averescu took the stand in the trial of his supporter Mihail Manoilescu

, who was arrested after having incited pro-Carol sentiment; in his testimony, he backed the notion that, despite his initial anger, Ferdinand had ultimately planned to have Carol return to the throne.

His grouping lost much of its supporters to the newly-formed National Peasants' Party

, and scored under 2% in the 1927 elections. Around 1930, Averescu began opposing the universal suffrage

he had endorsed earlier, and issued an appeal to the intellectual

s in order to have it discarded from legislation on the basis that it was easily influenced by the parties in power. He and his supporter, the pro-authoritarian

poet Octavian Goga

, received criticism from the left-wing Poporanist

journal Viaţa Românească

, who claimed that Averescu had in fact provoked and encouraged widespread electoral irregularities during his time in office.

In November 1930, he filed a complaint against the poet and journalist Bazil Gruia, claiming that the latter had libeled him by publishing, in January, an article in Chemarea which began by questioning the People's Party claim that Averescu was "the only honest comrade of the Romanian peasant" and contrasted it with the general's activities during the 1907 Revolt

. The trial was held in Cluj

, and Gruia was represented in court by Radu R. Rosetti. On December 1, he was found guilty and sentenced to 15 days in a correctional facility with reprieve, and to a fine of 3,000 lei

(soon after, Gruia benefited from a pardon).

Averescu was promoted to Marshal of Romania in the same year, during the time when Carol returned to rule as King — the appointment was attributed by Time

to his political support for the latter's return. According to the same source, by the end of 1930, Averescu was again at the center of Romanian politics, owing to Carol's favor, to the deaths of Ion I. C. and Vintilă Brătianu

, and to the unexpected support he gained from the PNL dissident Gheorghe I. Brătianu

.

; consequently, Goga was instigated by Carol to take over as leader of the People's Party, and the latter attacked Averescu for "subverting [...] the traditional respect enjoyed by the Crown". The clash led to Goga's creation of the splinter National Agrarian Party

, which, although never an important force, obtained more of the vote in the 1932 elections (approx. 3% compared to Averescu's 2%).

Around 1934, as the Guard proclaimed its allegiance to Nazi Germany

, the Italians (still rivals of Adolf Hitler

), approached Averescu (as well as Manoilescu, Nicolae Iorga

, Nichifor Crainic

, Cuza, Goga, and other non-Guardist reactionaries), with an offer for collaboration (see Comitati d'azione per l'universalità di Roma). This apparent alliance was, in fact, marked by major dissensions — Averescu and Iorga were routinely attacked by Crainic's Calendarul. Eventually, Averescu's group formed, in 1934, the Constitutional Front, a nationalist electoral alliance

with the National Liberal Party-Brătianu

, which was joined by Mihai Stelescu

's Crusade of Romanianism

(an Iron Guard offshoot), and the minor party created by Grigore Forţu (the Citizen Bloc); after the latter two parties disappeared, the Front survived in its original form until 1936, when it disbanded.

In 1937, despite his ongoing feud with Carol, Averescu was appointed a member of the Crown Council. Argetoianu recalled that he and the Marshal had reconciled — at a time when Argetoianu pondered rallying all opposition forces, including the National Peasants' Party, the National Liberal Party-Brătianu, and the Iron Guard, in a single electoral bloc (before the general election of December

, the various groups successfully negotiated an electoral pact against the government of Gheorghe Tătărescu

). Averescu, who, according to Argetoianu, declared was more interested in convincing Carol to allow his estranged wife Elena of Greece

to return to Romania, remained opposed to the deal.

The following year, he was briefly Minister without portfolio

in the cabinet of Premier Miron Cristea

, created by Carol to combat the ascension of the Iron Guard, and opposed the monarch's option to renounce the 1923 Constitution

and proclaim his dictatorship (the latter move signaled the end of the People's Party), but was among the figures displayed by Carol's regime. He died soon after in Bucharest, and was buried in the World War I heroes' crypt

in Mărăşti. In December, the king created the National Renaissance Front

as the political instrument of his authoritarian rule.

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

n marshal and populist

Populism

Populism can be defined as an ideology, political philosophy, or type of discourse. Generally, a common theme compares "the people" against "the elite", and urges social and political system changes. It can also be defined as a rhetorical style employed by members of various political or social...

politician. A Romanian Armed Forces

Romanian Armed Forces

The Land Forces, Air Force and Naval Forces of Romania are collectively known as the Romanian Armed Forces...

Commander during World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, he served as Prime Minister of three separate cabinets (as well as being interim Foreign Minister in January–March 1918 and Minister without portfolio

Minister without Portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister that does not head a particular ministry...

in 1938). He first rose to prominence during the peasant's revolt of 1907

1907 Romanian Peasants' Revolt

The 1907 Romanian Peasants' Revolt took place in March 1907 in Moldavia and it quickly spread, reaching Wallachia. The main cause was the discontent of the peasants about the inequity of land ownership, which was in the hands of just a few large landowners....

, which he helped repress in violence. Credited with engineering the defense of Moldavia

Moldavia

Moldavia is a geographic and historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester river...

in the 1916–1917 Campaign

Romanian Campaign (World War I)

The Romanian Campaign was part of the Balkan theatre of World War I, with Romania and Russia allied against the armies of the Central Powers. Fighting took place from August 1916 to December 1917, across most of present-day Romania, including Transylvania, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian...

, he built on his popularity to found and lead the successful People's Party, which he brought to power in 1920–1921, with backing from King

King of Romania

King of the Romanians , rather than King of Romania , was the official title of the ruler of the Kingdom of Romania from 1881 until 1947, when Romania was proclaimed a republic....

Ferdinand I

Ferdinand I of Romania

Ferdinand was the King of Romania from 10 October 1914 until his death.-Early life:Born in Sigmaringen in southwestern Germany, the Roman Catholic Prince Ferdinand Viktor Albert Meinrad of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, later simply of Hohenzollern, was a son of Leopold, Prince of...

and the National Liberal Party

National Liberal Party (Romania)

The National Liberal Party , abbreviated to PNL, is a centre-right liberal party in Romania. It is the third-largest party in the Romanian Parliament, with 53 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 22 in the Senate: behind the centre-right Democratic Liberal Party and the centre-left Social...

(PNL), and with the notable participation of Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu was a Romanian politician, one of the best-known personalities of interwar Greater Romania, who served as the Prime Minister between September 28 and November 23, 1939. His memoirs, Memorii. Pentru cei de mâine. Amintiri din vremea celor de ieri Constantin Argetoianu...

and Take Ionescu

Take Ionescu

Take or Tache Ionescu was a Romanian centrist politician, journalist, lawyer and diplomat, who also enjoyed reputation as a short story author. Starting his political career as a radical member of the National Liberal Party , he joined the Conservative Party in 1891, and became noted as a social...

.

His controversial first mandate, marked by a political crisis and oscillating support from the PNL's leader Ion I. C. Brătianu

Ion I. C. Bratianu

Ion I. C. Brătianu was a Romanian politician, leader of the National Liberal Party , the Prime Minister of Romania for five terms, and Foreign Minister on several occasions; he was the eldest son of statesman and PNL leader Ion Brătianu, the brother of Vintilă and Dinu Brătianu, and the father of...

, played a part in legislating land reform

Land reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

and repressed communist

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

activities, before being brought down by the rally of opposition forces. His second term of 1926–1927 brought a much-debated treaty with Fascist Italy

Italian Fascism

Italian Fascism also known as Fascism with a capital "F" refers to the original fascist ideology in Italy. This ideology is associated with the National Fascist Party which under Benito Mussolini ruled the Kingdom of Italy from 1922 until 1943, the Republican Fascist Party which ruled the Italian...

, and fell after Averescu gave clandestine backing to the ousted Prince Carol

Carol II of Romania

Carol II reigned as King of Romania from 8 June 1930 until 6 September 1940. Eldest son of Ferdinand, King of Romania, and his wife, Queen Marie, a daughter of Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, the second eldest son of Queen Victoria...

. Faced with the People Party's decline, Averescu closed deals with various right-wing forces and was instrumental in bringing Carol back to the throne in 1930. Relations between the two soured over the following years, and Averescu clashed with his fellow party member Octavian Goga

Octavian Goga

Octavian Goga was a Romanian politician, poet, playwright, journalist, and translator.-Life:Born in Răşinari, nearby Sibiu, he was an active member in the Romanian nationalistic movement in Transylvania and of its leading group, the Romanian National Party in Austria-Hungary. Before World War I,...

over the king's attitudes. Shortly before his death, he and Carol reconciled, and Averescu joined the Crown Council.

Averescu, who authored over 12 works on various military topics (including his memoirs from the frontline), was also an honorary member of the Romanian Academy

Romanian Academy

The Romanian Academy is a cultural forum founded in Bucharest, Romania, in 1866. It covers the scientific, artistic and literary domains. The academy has 181 acting members who are elected for life....

and an Order of Michael the Brave

Order of Michael the Brave

The Order of Michael the Brave is Romania's highest military decoration, instituted by King Ferdinand I during the early stages of the Romanian Campaign of World War I, and was again awarded in World War II...

recipient. He became a Marshal of Romania in 1930.

Early life and career

Averescu was born in Ozerne (previously known as Babele, and subsequently renamed Alexandru Averescu), a village northwest of IzmailIzmail

Izmail is a historic town near the Danube river in the Odessa Oblast of south-western Ukraine. Serving as the administrative center of the Izmail Raion , the city itself is also designated as a separate raion within the oblast....

, now part of Ukraine

Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It has an area of 603,628 km², making it the second largest contiguous country on the European continent, after Russia...

. The son of Constantin Averescu, who held the rank

Historical Romanian ranks and titles

This is a glossary of historical Romanian ranks and titles used in the principalities of Moldavia, Wallachia and Transylvania, and later in Romania. Many of these titles are of Slavic etymology, with some of Greek, Byzantine, Latin, and Turkish etymology; several are original...

of sluger

Sluger

Sluger was a historical rank traditionally held by boyars in Moldavia and Wallachia, roughly corresponding to that of Masters of the Royal Court. It originated in the Slavic služar....

, he studied at the Romanian Orthodox

Romanian Orthodox Church

The Romanian Orthodox Church is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church. It is in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox churches, and is ranked seventh in order of precedence. The Primate of the church has the title of Patriarch...

seminary

Seminary

A seminary, theological college, or divinity school is an institution of secondary or post-secondary education for educating students in theology, generally to prepare them for ordination as clergy or for other ministry...

in Izmail, then at the School of Arts and Crafts in Bucharest

Bucharest

Bucharest is the capital municipality, cultural, industrial, and financial centre of Romania. It is the largest city in Romania, located in the southeast of the country, at , and lies on the banks of the Dâmbovița River....

(intending to become an engineer

Engineer

An engineer is a professional practitioner of engineering, concerned with applying scientific knowledge, mathematics and ingenuity to develop solutions for technical problems. Engineers design materials, structures, machines and systems while considering the limitations imposed by practicality,...

). In 1876, he decided to join the Gendarmes

Jandarmeria Româna

Jandarmeria Română is the military branch of the two Romanian police forces .The gendarmerie is subordinated to the Ministry of Interior and Administrative Reform and does not have responsibility for policing the Romanian Armed Forces...

in Izmail.

Seeing action as a cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

sergeant with the Romanian troops engaged in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878

Russo-Turkish War, 1877–1878

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 was a conflict between the Ottoman Empire and the Eastern Orthodox coalition led by the Russian Empire and composed of numerous Balkan...

, he was decorated on several occasions, but was later moved to reserve (after failing his medical examination due to the effects of frostbite

Frostbite

Frostbite is the medical condition where localized damage is caused to skin and other tissues due to extreme cold. Frostbite is most likely to happen in body parts farthest from the heart and those with large exposed areas...

). He was, however, reinstated later in 1878, and subsequently received a military education in Romania, at the military school of Târgovişte

Târgoviste

Târgoviște is a city in the Dâmbovița county of Romania. It is situated on the right bank of the Ialomiţa River. , it had an estimated population of 89,000. One village, Priseaca, is administered by the city.-Name:...

(Dealu Monastery

Dealu Monastery

Dealu Monastery is a 15th century monastery in Dâmboviţa County, Romania, located 6 km north of Târgovişte.The church of the monastery is dedicated to Saint Nicholas.-Sources and external links:...

), and in Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, at the Military Academy of Turin

Turin

Turin is a city and major business and cultural centre in northern Italy, capital of the Piedmont region, located mainly on the left bank of the Po River and surrounded by the Alpine arch. The population of the city proper is 909,193 while the population of the urban area is estimated by Eurostat...

. Averescu married an Italian opera

Opera

Opera is an art form in which singers and musicians perform a dramatic work combining text and musical score, usually in a theatrical setting. Opera incorporates many of the elements of spoken theatre, such as acting, scenery, and costumes and sometimes includes dance...

singer, Clotilda Caligaris, who had been the prima donna

Prima donna

Originally used in opera or Commedia dell'arte companies, "prima donna" is Italian for "first lady." The term was used to designate the leading female singer in the opera company, the person to whom the prime roles would be given. The prima donna was normally, but not necessarily, a soprano...

of La Scala

La Scala

La Scala , is a world renowned opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as the New Royal-Ducal Theatre at La Scala...

. His future collaborator and rival Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu was a Romanian politician, one of the best-known personalities of interwar Greater Romania, who served as the Prime Minister between September 28 and November 23, 1939. His memoirs, Memorii. Pentru cei de mâine. Amintiri din vremea celor de ieri Constantin Argetoianu...

stated that Averescu "chose Mrs. Clotilda at random".

Upon his return, Averescu steadily climbed through the ranks. He was head of the Bucharest Military Academy (1894–1895), and, in 1895-1898, Romania's military attaché

Attaché

Attaché is a French term in diplomacy referring to a person who is assigned to the diplomatic or administrative staff of a higher placed person or another service or agency...

in the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

; a colonel in 1901, he was advanced to the rank of Brigadier General

Brigadier General

Brigadier general is a senior rank in the armed forces. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries, usually sitting between the ranks of colonel and major general. When appointed to a field command, a brigadier general is typically in command of a brigade consisting of around 4,000...

and became head of the Tecuci

Tecuci

Tecuci is a city in the Galaţi county of Romania , situated among wooded hills, on the right bank of the Bârlad River, and at the junction of railways from Galaţi, Bârlad and Mărăşeşti.-History:...

regional Army Command Center in 1906.

Before the World War, he led the troops in crushing the 1907 peasants' revolt

1907 Romanian Peasants' Revolt

The 1907 Romanian Peasants' Revolt took place in March 1907 in Moldavia and it quickly spread, reaching Wallachia. The main cause was the discontent of the peasants about the inequity of land ownership, which was in the hands of just a few large landowners....

— where he engaged in using very harsh means of repression, especially when dealing with soldiers who refused to fight against the rebels — and was subsequently Minister of War in Dimitrie Sturdza

Dimitrie Sturdza

Dimitrie Sturdza was a Romanian statesman of the late 19th century, and president of the Romanian Academy between 1882 and 1884.-Biography:Born in Iaşi, Moldavia, and educated there at the Academia Mihăileană, he continued his studies in Germany, took part in the political movements of the time,...

's National Liberal Party

National Liberal Party (Romania)

The National Liberal Party , abbreviated to PNL, is a centre-right liberal party in Romania. It is the third-largest party in the Romanian Parliament, with 53 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 22 in the Senate: behind the centre-right Democratic Liberal Party and the centre-left Social...

(PNL) cabinet (1907–1909). According to the recollections of Eliza Brătianu, a split occurred between him and the PNL after Averescu attempted to advance various political goals — the conflict erupted when he sought support with King

King of Romania

King of the Romanians , rather than King of Romania , was the official title of the ruler of the Kingdom of Romania from 1881 until 1947, when Romania was proclaimed a republic....

Carol I

Carol I of Romania

Carol I , born Prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen was reigning prince and then King of Romania from 1866 to 1914. He was elected prince of Romania on 20 April 1866 following the overthrow of Alexandru Ioan Cuza by a palace coup...

and then, as the National Liberals deeply resented Romania's alliance with the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

, he approached the Germans for backing.

Subsequently, he was commander of the First Infantry Division (stationed in Turnu Severin

Drobeta-Turnu Severin

Drobeta-Turnu Severin is a city in Mehedinţi County, Oltenia, Romania, on the left bank of the Danube, below the Iron Gates.The city administers three villages: Dudaşu Schelei, Gura Văii, and Schela Cladovei...

) and, later, of the Second Army Corps in Craiova

Craiova

Craiova , Romania's 6th largest city and capital of Dolj County, is situated near the east bank of the river Jiu in central Oltenia. It is a longstanding political center, and is located at approximately equal distances from the Southern Carpathians and the River Danube . Craiova is the chief...

. In 1912, he became a Major General

Major General

Major general or major-general is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. A major general is a high-ranking officer, normally subordinate to the rank of lieutenant general and senior to the ranks of brigadier and brigadier general...

, and, in 1911-1913, he was Chief of the General Staff. In the latter capacity, Averescu organized the actions of Romanian troops operating south of the Danube

Danube

The Danube is a river in the Central Europe and the Europe's second longest river after the Volga. It is classified as an international waterway....

in the Second Balkan War

Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 29 June 1913. Bulgaria had a prewar agreement about the division of region of Macedonia...

(the campaign against Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

, during which his troops met no resistance).

World War and first cabinet

During the World War (in which Romania entered in 1916), he led the Second Army in the defense of the Southern CarpathiansSouthern Carpathians

The Southern Carpathians or the Transylvanian Alps are a group of mountain ranges which divide central and southern Romania, on one side, and Serbia, on the other side. They cover part of the Carpathian Mountains that is located between the Prahova River in the east and the Timiș and Cerna Rivers...

, and was then moved to the head of the Third Army (following the latter's defeat in the Battle of Turtucaia

Battle of Turtucaia

The Battle of Turtucaia in Bulgaria, was the opening battle of the first Central Powers offensive during the Romanian Campaign of World War I...

). He commanded Army Group South in the Flămânda operation

Flamânda Offensive

The Flămânda Offensive The Flămânda Offensive The Flămânda Offensive (or Flămânda Maneuver, which took place between 29 September and 5 October 1916, was an offensive across the Danube mounted by the Romanian 2nd Army during World War I. The battle represented a consistent effort by the Romanian...

against the Third Bulgarian Army and other forces of the Central Powers

Central Powers

The Central Powers were one of the two warring factions in World War I , composed of the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulgaria...

, ultimately stopped by the German offensive (Averescu's forces did not register important losses, and orderly retreated to Moldavia

Moldavia

Moldavia is a geographic and historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester river...

, where Romanian authorities had taken refuge from the successful German operations).

Promoted Lieutenant General

Lieutenant General

Lieutenant General is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages where the title of Lieutenant General was held by the second in command on the battlefield, who was normally subordinate to a Captain General....

at 1 January 1917, Averescu again led the Second Army to victory in the Battles of Mărăşti

Battle of Marasti

The Battle of Mărăşti was one of the main battles to take place on Romanian soil in World War I. It was fought between July 22 and August 1, 1917, and was an offensive operation of the Romanian and Russian Armies intended to encircle and destroy the German 9th Army...

and Mărăşeşti

Battle of Marasesti

The Battle of Mărăşeşti, Vrancea County, eastern Romania was a major battle fought during World War I between Germany and Romania.-Premise:...

(August 1917); his achievements, including his brief breakthrough at Mărăşti, were considered impressive by public opinion and his officers. However, several military historians rate Averescu and his fellow Romanian generals very poorly, arguing that, overall, their direction of the war "could not have been worse". Despite controlling an army of 500,000 plus 100,000 Russian reinforcements, they were soundly defeated by a much smaller German-Austrian

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

-Bulgarian army in less than four months of combat.

Averescu was widely seen as the person behind a relatively successful resistance to further offensives on Moldavia

Moldavia

Moldavia is a geographic and historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester river...

(the single piece of territory still held by the Romanian state), and he was considered by many of his contemporaries to have stood in contrast to the what was seen as endemic corruption and incompetence. The state of affairs, together with the October Revolution

October Revolution

The October Revolution , also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution , Red October, the October Uprising or the Bolshevik Revolution, was a political revolution and a part of the Russian Revolution of 1917...

in Russia, was to be blamed for the eventual Romanian surrender to the Central Powers; promoted Premier by King

King of Romania

King of the Romanians , rather than King of Romania , was the official title of the ruler of the Kingdom of Romania from 1881 until 1947, when Romania was proclaimed a republic....

Ferdinand I

Ferdinand I of Romania

Ferdinand was the King of Romania from 10 October 1914 until his death.-Early life:Born in Sigmaringen in southwestern Germany, the Roman Catholic Prince Ferdinand Viktor Albert Meinrad of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, later simply of Hohenzollern, was a son of Leopold, Prince of...

during the period of crisis, Averescu began armistice

Armistice

An armistice is a situation in a war where the warring parties agree to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, but may be just a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace...

talks with August von Mackensen

August von Mackensen

Anton Ludwig August von Mackensen , born August Mackensen, was a German soldier and field marshal. He commanded with success during the First World War and became one of the German Empire's most prominent military leaders. After the Armistice, Mackensen was interned for a year...

in Buftea

Buftea

Buftea is a town in Ilfov county, Romania, located 20 km north-west of Bucharest. Its population is growing due to its proximity to Bucharest. One village, Buciumeni, is administered by the town....

and Focşani

Focsani

Focşani is the capital city of Vrancea County in Romania on the shores the Milcov river, in the historical region of Moldavia. It has a population of 101,854.-Geography:...

, but was vehemently opposed to the terms — he resigned, leaving the Alexandru Marghiloman

Alexandru Marghiloman

Alexandru Marghiloman was a Romanian conservative statesman who served for a short time in 1918 as Prime Minister of Romania, and had a decisive role during World War I.-Early career:...

cabinet when it signed the Treaty of Bucharest

Treaty of Bucharest, 1918

The Treaty of Bucharest was a peace treaty which the German Empire forced Romania to sign on 7 May 1918 following the Romanian campaign of 1916-1917.-Main terms of the treaty:...

. Despite Averescu's talks yielding no result, he was repeatedly attacked by his political adversaries for having initiated them.

Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic , commonly referred to as Soviet Russia, Bolshevik Russia, or simply Russia, was the largest, most populous and economically developed republic in the former Soviet Union....

military action: just before Averescu came to power, as Russia's Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky

Leon Trotsky , born Lev Davidovich Bronshtein, was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and theorist, Soviet politician, and the founder and first leader of the Red Army....

negotiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was a peace treaty signed on March 3, 1918, mediated by South African Andrik Fuller, at Brest-Litovsk between Russia and the Central Powers, headed by Germany, marking Russia's exit from World War I.While the treaty was practically obsolete before the end of the year,...

with Germany, the Rumcherod

Rumcherod

Rumcherod was a self-proclaimed, unrecognized, and short-lived organ of Soviet power in the South-Western part of Russian Empire that functioned during May 1917–May 1918...

administrative body in Odessa

Odessa

Odessa or Odesa is the administrative center of the Odessa Oblast located in southern Ukraine. The city is a major seaport located on the northwest shore of the Black Sea and the fourth largest city in Ukraine with a population of 1,029,000 .The predecessor of Odessa, a small Tatar settlement,...

, led by Christian Rakovsky

Christian Rakovsky

Christian Rakovsky was a Bulgarian socialist revolutionary, a Bolshevik politician and Soviet diplomat; he was also noted as a journalist, physician, and essayist...

, ordered an offensive from the east into Romania. In order to prevent further losses, Averescu signed his name to a much-criticized temporary armistice with the Rumcherod; eventually, Rakovsky was himself faced with a German offensive (sparked by the temporary breakdown of negotiations at Brest-Litovsk), and had to abandon both his command and the base in Odessa.

Character

Averescu quit the army in the spring of 1918, aiming for a career in politics — initially, with a message that was hostile to the National Liberal PartyNational Liberal Party (Romania)

The National Liberal Party , abbreviated to PNL, is a centre-right liberal party in Romania. It is the third-largest party in the Romanian Parliament, with 53 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 22 in the Senate: behind the centre-right Democratic Liberal Party and the centre-left Social...

(PNL) and its leader Ion I. C. Brătianu

Ion I. C. Bratianu

Ion I. C. Brătianu was a Romanian politician, leader of the National Liberal Party , the Prime Minister of Romania for five terms, and Foreign Minister on several occasions; he was the eldest son of statesman and PNL leader Ion Brătianu, the brother of Vintilă and Dinu Brătianu, and the father of...

.

He presided over the People's Party (initially named People's League), and he was immensely popular especially among peasants after the end of the war. His force had an appealing populist

Populism

Populism can be defined as an ideology, political philosophy, or type of discourse. Generally, a common theme compares "the people" against "the elite", and urges social and political system changes. It can also be defined as a rhetorical style employed by members of various political or social...

message, translated into vague promises and relying on the image of the General: peasants had been promised land at the beginning of the war (and they were being rewarded with it at the very moment, through an agrarian reform

Land reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

that reached its full scope in 1923); they had formed the larger part of the Army, and had come to see Averescu as the one to fulfill their expectations, as well as a figure who was still commanding their allegiance. Eliza Brătianu, the PNL leader's wife, placed Averescu's ascension in the context of Greater Romania

Greater Romania

The Greater Romania generally refers to the territory of Romania in the years between the First World War and the Second World War, the largest geographical extent of Romania up to that time and its largest peacetime extent ever ; more precisely, it refers to the territory of the Kingdom of...

's creation through the addition of Bessarabia

Bessarabia

Bessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

, Bukovina

Bukovina

Bukovina is a historical region on the northern slopes of the northeastern Carpathian Mountains and the adjoining plains.-Name:The name Bukovina came into official use in 1775 with the region's annexation from the Principality of Moldavia to the possessions of the Habsburg Monarchy, which became...

, and Transylvania

Transylvania

Transylvania is a historical region in the central part of Romania. Bounded on the east and south by the Carpathian mountain range, historical Transylvania extended in the west to the Apuseni Mountains; however, the term sometimes encompasses not only Transylvania proper, but also the historical...

(while making use of the condescending National Liberal tone towards the Romanian National Party

Romanian National Party

The Romanian National Party , initially known as the Romanian National Party in Transylvania and Banat , was a political party which was initially designed to offer ethnic representation to Romanians in the Kingdom of Hungary, the Transleithanian half of Austria-Hungary, and especially to those in...

that was emerging triumphant in previously Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

Transylvania):

"[The] so very harsh losses [during the war], the defeats suffered by the Old KingdomRomanian Old KingdomThe Romanian Old Kingdom is a colloquial term referring to the territory covered by the first independent Romanian nation state, which was composed of the Danubian Principalities—Wallachia and Moldavia...

, the traces of foreign domination in the newly-acquired provinces, but most of all the state of unhealthy euphoria that had taken hold of Transylvania, who had begun, in all good faith, to believe that only she had made the union happen, all of these have created a sort of insecurity within the borders of [Greater Romania]."

As the movement initially tended to describe itself as a social trend rather than a political party

Political party

A political party is a political organization that typically seeks to influence government policy, usually by nominating their own candidates and trying to seat them in political office. Parties participate in electoral campaigns, educational outreach or protest actions...

, it also attracted former members of the Conservative Party

Conservative Party (Romania, 1880-1918)

The Conservative Party was between 1880 and 1918 one of Romania's two most important parties, the other one being the Liberal Party...

(such as Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu

Constantin Argetoianu was a Romanian politician, one of the best-known personalities of interwar Greater Romania, who served as the Prime Minister between September 28 and November 23, 1939. His memoirs, Memorii. Pentru cei de mâine. Amintiri din vremea celor de ieri Constantin Argetoianu...

, Constantin Garoflid, and Take Ionescu

Take Ionescu

Take or Tache Ionescu was a Romanian centrist politician, journalist, lawyer and diplomat, who also enjoyed reputation as a short story author. Starting his political career as a radical member of the National Liberal Party , he joined the Conservative Party in 1891, and became noted as a social...

), military men such as Constantin Coandă

Constantin Coanda

Constantin Coandă was a Romanian soldier and politician. He reached the rank of general in the Romanian Army, and later became mathematics professor at the National School of Bridges and Roads in Bucharest...

, the Democratic Nationalist Party leader A. C. Cuza

A. C. Cuza

A. C. Cuza was a Romanian far right politician and theorist.-Early life:Born in Iaşi, after attending secondary school in his native city and in Dresden, Cuza studied law at the University of Paris, the Universität unter den Linden, and the Université Libre de Bruxelles...

, the notorious supporters of dirigisme

Dirigisme

Dirigisme is an economy in which the government exerts strong directive influence. While the term has occasionally been applied to centrally planned economies, where the state effectively controls both production and allocation of resources , it originally had neither of these meanings when...

Mihail Manoilescu

Mihail Manoilescu

Mihail Manoilescu was a Romanian journalist, engineer, economist, politician and memoirist, who served as Foreign Minister of Romania during the summer of 1940...

and Ştefan Zeletin, the moderate nationalist

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

Duiliu Zamfirescu

Duiliu Zamfirescu

Duiliu Zamfirescu was a Romanian novelist, poet, short story writer, lawyer, nationalist politician, journalist, diplomat and memoirist. In 1909, he was elected a member of the Romanian Academy, and, for a while in 1920, he was Foreign Minister of Romania...

, the future diplomat Citta Davila, the journalist D. R. Ioaniţescu, the left-wing agrarianist

Agrarianism

Agrarianism has two common meanings. The first meaning refers to a social philosophy or political philosophy which values rural society as superior to urban society, the independent farmer as superior to the paid worker, and sees farming as a way of life that can shape the ideal social values...

Petru Groza

Petru Groza

Petru Groza was a Romanian politician, best known as the Prime Minister of the first Communist Party-dominated governments under Soviet occupation during the early stages of the Communist regime in Romania....

, the Bukovinan leader Iancu Flondor

Iancu Flondor

Iancu Flondor was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian activist who advocated Bukovina's unifion with the Kingdom of Romania....

, and the lawyer Petre Papacostea. Additional support came from Transylvanian activists such as Octavian Goga

Octavian Goga

Octavian Goga was a Romanian politician, poet, playwright, journalist, and translator.-Life:Born in Răşinari, nearby Sibiu, he was an active member in the Romanian nationalistic movement in Transylvania and of its leading group, the Romanian National Party in Austria-Hungary. Before World War I,...

and Teodor Mihali, who had previously left the Romanian National Party

Romanian National Party

The Romanian National Party , initially known as the Romanian National Party in Transylvania and Banat , was a political party which was initially designed to offer ethnic representation to Romanians in the Kingdom of Hungary, the Transleithanian half of Austria-Hungary, and especially to those in...

there in protest over the policies of its president Iuliu Maniu

Iuliu Maniu

Iuliu Maniu was an Austro-Hungarian-born Romanian politician. A leader of the National Party of Transylvania and Banat before and after World War I, he served as Prime Minister of Romania for three terms during 1928–1933, and, with Ion Mihalache, co-founded the National Peasants'...

. Nevertheless, the People's Party did attempt to approach Maniu for an alliance at various intervals after summer 1919 (according to Argetoianu, their attempts were frustrated by King

King of Romania

King of the Romanians , rather than King of Romania , was the official title of the ruler of the Kingdom of Romania from 1881 until 1947, when Romania was proclaimed a republic....

Ferdinand I

Ferdinand I of Romania

Ferdinand was the King of Romania from 10 October 1914 until his death.-Early life:Born in Sigmaringen in southwestern Germany, the Roman Catholic Prince Ferdinand Viktor Albert Meinrad of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, later simply of Hohenzollern, was a son of Leopold, Prince of...

, whose relationship with Maniu was cordial at the time, and who allegedly stated "Maniu is no one else's! Maniu is mine!").

The grouping also established close links with Garda Conştiinţei Naţionale (GCN, "The National Awareness Guard"), a reactionary

Reactionary

The term reactionary refers to viewpoints that seek to return to a previous state in a society. The term is meant to describe one end of a political spectrum whose opposite pole is "radical". While it has not been generally considered a term of praise it has been adopted as a self-description by...

group formed by the electrician Constantin Pancu, engaged in violence against communist

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

activists in Iaşi

Iasi

Iași is the second most populous city and a municipality in Romania. Located in the historical Moldavia region, Iași has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Romanian social, cultural, academic and artistic life...

(the latter were feared by Averescu as well). Nevertheless, in late 1919, Averescu and Argetoianu approached the Socialist Party of Romania

Socialist Party of Romania

The Socialist Party of Romania was a Romanian socialist political party, created on December 11, 1918 by members of the Romanian Social Democratic Party , after the latter emerged from clandestinity...

and its associate, the Social Democratic Party of Transylvania and Banat, with an offer for collaboration, negotiating the matter with the parties' reformist

Reformism

Reformism is the belief that gradual democratic changes in a society can ultimately change a society's fundamental economic relations and political structures...

leaders — Ioan Flueraş

Ioan Flueras

Ioan Flueraş was a Romanian social democratic politician and a victim of the communist regime.-Early activities:...

, Ilie Moscovici, and Iosif Jumanca. At the time, Argetoianu claimed, his conversations with Moscovici revealed the fact that the latter was growing suspicious of the party's far left

Far left

Far left, also known as the revolutionary left, radical left and extreme left are terms which refer to the highest degree of leftist positions among left-wing politics...

wing, where "the blanket-maker Cristescu

Gheorghe Cristescu

Gheorghe Cristescu was a Romanian socialist and, for a part of his life, communist militant. Nicknamed "Plăpumarul" , he is also occasionally referred to as "Omul cu lavaliera roşie" , after the most notable of his accessories.-Early activism:Born in Copaciu Gheorghe Cristescu (October 10, 1882...

and others were agitating". Averescu proposed merging the two parties, as a distinct section, into the People's Party; he was refused, and talks broke down when the general expected the Socialists to support his electoral platform.

Impact

According to Eliza Brătianu (who was comparing Averescu with the FrenchFrance

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

rebel soldier Georges Boulanger

Georges Boulanger

Georges Ernest Jean-Marie Boulanger was a French general and reactionary politician. At the apogee of his popularity in January 1889 many republicans including Georges Clemenceau feared the threat of a coup d'état by Boulanger and the establishment of a dictatorship.- Early life and career :Born...

), several voices inside his movement called on Averescu to lead a republican

Republicanism

Republicanism is the ideology of governing a nation as a republic, where the head of state is appointed by means other than heredity, often elections. The exact meaning of republicanism varies depending on the cultural and historical context...

coup d'état

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

against King Ferdinand and her husband — a move allegedly prevented only by the general's loyalism. Argetoianu, who admitted that "I shook hands with Averescu [...] expecting a dictatorial regime", claimed that, during his stay in Italy, the general had been decisively influenced by Radicalism

Radicalism (historical)

The term Radical was used during the late 18th century for proponents of the Radical Movement. It later became a general pejorative term for those favoring or seeking political reforms which include dramatic changes to the social order...

and the Risorgimento

Italian unification

Italian unification was the political and social movement that agglomerated different states of the Italian peninsula into the single state of Italy in the 19th century...

movement. This, in Argetoianu's view, was the cause for his repeated involvement in conspiracies

Conspiracy (political)

In a political sense, conspiracy refers to a group of persons united in the goal of usurping or overthrowing an established political power. Typically, the final goal is to gain power through a revolutionary coup d'état or through assassination....

; he recalled that, in 1919, Davila's house was the scene of regular reunion of officers, who plotted Brătianu's ousting and pondered dethroning the king (in this version of events, Averescu initially accepted to be proclaimed dictator, but, around October of that year, called on conspirators to renounce their plan).

Aiming to answer most of Romania's social and political issues, the League's founding document called for:

"A land reform, with the passage of the land which is at the moment expropriatedNationalizationNationalisation, also spelled nationalization, is the process of taking an industry or assets into government ownership by a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to private assets, but may also mean assets owned by lower levels of government, such as municipalities, being...

only on principle [ - a reference to the 1917 promise for a land reform] into the effective and immediate ownership of villagers through the means of communes; an electoral reformElectoral reformElectoral reform is change in electoral systems to improve how public desires are expressed in election results. That can include reforms of:...

, through universal suffrageUniversal suffrageUniversal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

, direct electionDirect electionDirect election is a term describing a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the person, persons or political party that they desire to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are chosen depends upon the...

, secret ballotSecret ballotThe secret ballot is a voting method in which a voter's choices in an election or a referendum are anonymous. The key aim is to ensure the voter records a sincere choice by forestalling attempts to influence the voter by intimidation or bribery. The system is one means of achieving the goal of...

, and compulsory votingCompulsory votingCompulsory voting is a system in which electors are obliged to vote in elections or attend a polling place on voting day. If an eligible voter does not attend a polling place, he or she may be subject to punitive measures such as fines, community service, or perhaps imprisonment if fines are unpaid...

, with representationRepresentation (politics)In politics, representation describes how some individuals stand in for others or a group of others, for a certain time period. Representation usually refers to representative democracies, where elected officials nominally speak for their constituents in the legislature...

given to ethnic minoritiesMinorities of RomaniaOfficially, 10.5% of Romania's population is represented by minorities . The principal minorities in Romania are Hungarians and Roma people, with a declining German population and smaller numbers of Poles in Bucovina...

, since the latter would not hinder the free manifestation of political individualities; administrative decentralizationDecentralization__FORCETOC__Decentralization or decentralisation is the process of dispersing decision-making governance closer to the people and/or citizens. It includes the dispersal of administration or governance in sectors or areas like engineering, management science, political science, political economy,...

."

According to Argetoianu,

"in the autumn of 1919, [Averescu's] popularity had reached its peak. In the villages, people would dream of him, some swore that they had seen him descending from an airplane into their midst, others, who had fought in the war, told that they had lived by his side in the trenchesTrench warfareTrench warfare is a form of occupied fighting lines, consisting largely of trenches, in which troops are largely immune to the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery...

, it was through him that hopes were solidified, and he was expected of to provide a miracle for people to live a carefree and fulfilling life. His popularity was something mysticalMysticismMysticism is the knowledge of, and especially the personal experience of, states of consciousness, i.e. levels of being, beyond normal human perception, including experience and even communion with a supreme being.-Classical origins:...

, something supernatural, and all sorts of legends had begun to surround this MessiahMessiahA messiah is a redeemer figure expected or foretold in one form or another by a religion. Slightly more widely, a messiah is any redeemer figure. Messianic beliefs or theories generally relate to eschatological improvement of the state of humanity or the world, in other words the World to...

of the Romanian people."

Although he was also Prime Minister of Romania for three mandates (1918, 1920–1921, 1926–1927), his political success is not as spectacular as the military one. Averescu ended up as one of the pawns maneuvered by Brătianu. Argetoianu later repeatedly expressed his distaste for Averescu's hesitant stance and openness to compromise.

Establishment

Initially, Brătianu approached Averescu using their shared displeasure over the Alexandru Vaida-VoevodAlexandru Vaida-Voevod

Alexandru Vaida-Voevod or Vaida-Voievod was a Romanian politician who was a supporter and promoter of the union of Transylvania with the Romanian Old Kingdom; he later served three terms as a Prime Minister of Greater Romania.-Transylvanian politics:He was born to a Greek-Catholic family in the...

Romanian National Party

Romanian National Party

The Romanian National Party , initially known as the Romanian National Party in Transylvania and Banat , was a political party which was initially designed to offer ethnic representation to Romanians in the Kingdom of Hungary, the Transleithanian half of Austria-Hungary, and especially to those in...

(PNR)-Peasants' Party

Peasants' Party (Romania)