Basque language

Encyclopedia

Basque is the ancestral language

of the Basque people

, who inhabit the Basque Country, a region spanning an area in northeastern Spain

and southwestern France

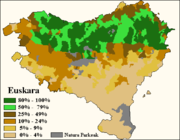

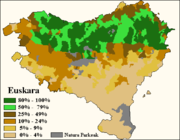

. It is spoken by 25.7% of Basques in all territories (665,800 out of 2,589,600). Of these, 614,000 live in the Spanish part of the Basque country and the remaining 51,800 live in the French part.

In academic discussions of the distribution of Basque in Spain and France, it is customary to refer to three ancient provinces

in France and four Spanish provinces. Native speakers are concentrated in a contiguous area including parts of the Spanish Autonomous Communities of the Basque Autonomous Community

(Spanish: País Vasco; Euskara: Euskadi) and Navarre

and in the western half of the French Département of Pyrénées-Atlantiques

. The Autonomous Community of País Vasco/Euskadi is an administrative entity within the binational ethnographic Basque Country incorporating the traditional Spanish provinces of Biscay

, Gipuzkoa, and Álava

, which retain their existence as politico-administrative divisions.

These provinces and many areas of Navarre are heavily populated by ethnic Basques, but the Euskara language had, at least until the 1990s, all but disappeared from most of Álava, western parts of Biscay and central and southern areas of Navarre

. In southwestern France, the ancient Basque-populated provinces were Labourd

, Lower Navarre

, and Soule

. They and other regions were consolidated into a single département in 1790 under the name Basses-Pyrénées, a name which persisted until 1970.

A standardized form of the Basque language, called Euskara Batua, was developed by the Basque Language Academy

in the late 1960s. Euskara Batua was created so that Basque language could be used—and easily understood by all Basque speakers—in formal situations (education, mass media, literature...), and this is its main use nowadays. This standard Basque is taught and used as a teaching language (as an option, together with standard Spanish) at most educational levels in the Spanish part of the Basque Country, while the intensity, status and funding by state bodies to Basque language instruction varies depending on the area. In France, the Basque language school Seaska and the association for a bilingual (Basque and French) schooling Ikasbi meet a wide range of Basque language educational needs up to the Sixth Form, while often struggling to surmount financial and administrative constraints.

Apart from this standardized version, there are five main Basque dialects: Bizkaian, Gipuzkoan

, and Upper Navarrese

in Spain, and Navarrese-Lapurdian and Zuberoan

(in France). Although they take their names from the mentioned historic provinces, the dialect boundaries are not congruent with province boundaries.

In French the language is normally called basque or, in recent times, euskara. There is a greater variety of Spanish names for the language. Today, it is most commonly referred to as el vasco, la lengua vasca or el euskera. Both terms, vasco and basque, are inherited from Latin ethnonym

Vascones which in turn goes back to the Greek term ουασκωνους (ouaskōnous), an ethnonym used by Strabo

in his Geographica

(23 CE, Book III).

The term Vascuence, derived from Latin vasconĭce, has acquired negative connotations over the centuries and is not well liked amongst Basque speakers generally. Its use is documented at least as far back as the 14th century when a law passed in Huesca

in 1349 stated that Item nuyl corridor nonsia usado que faga mercadería ninguna que compre nin venda entre ningunas personas, faulando en algaravia nin en abraych nin en basquenç: et qui lo fara pague por coto XXX sol—essentially penalizing the use of Arabic, Hebrew or Vascuence (Basque) with a fine of 30 sols

.

Romance languages, Basque is classified as a language isolate

. It is the last remaining descendant of the pre-Indo-European

languages of Western Europe. Consequently, its prehistory may not be reconstructible by means of the comparative method

except by applying it to differences between dialects within the language. Little is known of its origins but it is likely that an early form of the Basque language was present in Western Europe before the arrival of the Indo-European languages to the area.

Latin inscriptions in Aquitania

preserve a number of words with cognates in reconstructed proto-Basque, for instance the personal names Nescato and Cison (neskato and gizon mean "young girl" and "man" respectively in modern Basque). This language is generally referred to as Aquitanian

and is assumed to have been spoken in the area before the Roman

conquests in the western Pyrenees

. Some authors even argue that the language moved westward during the Late Antiquity

, after the fall of Rome

, into the north part of Hispania

in which Basque is spoken today.

Roman neglect of this area allowed Aquitanian to survive while the Iberian

and Tartessian language

s became extinct. Through the long contact with Romance languages, Basque adopted a sizable number of Romance words. Initially the source was Latin, later Gascon

(a branch of Occitan) in the northeast, Navarro-Aragonese

in the southeast and Spanish

in the southwest.

The region in which Basque is spoken today has contracted over centuries and is thus smaller than what is known as the Basque Country

The region in which Basque is spoken today has contracted over centuries and is thus smaller than what is known as the Basque Country

, or Euskal Herria in Basque. Toponyms show that the Basque language used to be spoken further eastward in the Pyrenees than today. An example is the Aran Valley (now a Gascon

-speaking part of Catalonia

), for (h)aran is the Basque word for "valley". However, the growing influence of Latin began to drive Basque out from the less mountainous portions of the region.

The Reconquista

temporarily counteracted this tendency when the Christian lords called on northern Iberian peoples – Basques, Asturians, and "Franks

" – to colonize the new conquests. The Basque language became the main everyday language, while other languages like Spanish

, Gascon

, French

, or Latin were preferred for the administration and high education.

Basque experienced a rapid decline in Alava and Navarre during the 19th century. However, the rise of Basque nationalism

spurred increased interest in the language as a sign of ethnic identity, and with the establishment of autonomous governments, it has recently made a modest comeback. Basque-language schools have brought the language to areas such as Encartaciones and the Navarrese Ribera, where it may have disappeared as a native language in the Middle Ages.

However, Basque was explicitly recognized in some areas. For instance, the local charter

of the Basque-colonized

Ojacastro

valley (now in La Rioja

) allowed the inhabitants to use Basque in legal processes in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Today Basque holds co-official language status in the Basque regions of Spain: the full autonomous community of the Basque Country

and some parts of Navarre

. Basque has no official standing in the Northern Basque Country

of France and French citizens are barred from officially using Basque in a French court of law. However, the use of Basque by Spanish nationals in French courts is allowed (with translation), as Basque is officially recognized on the other side of the border.

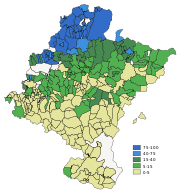

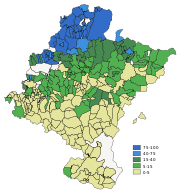

The positions of the various existing governments differ with regard to the promotion of Basque in areas where Basque is commonly spoken. The language has official status in those territories that are within the Basque Autonomous Community, where it is spoken and promoted heavily, but only partially in Navarre. Here the "Ley del Vascuence" ("Law of Basque"), seen as contentious by many Basques, divides Navarre into three language areas: Basque-speaking, non-Basque-speaking, and mixed. The support for the language and the linguistic rights of citizens vary depending on which of the three areas you are in.

Taken together, in 2006 out of a total population of 2,589,600 (1,850,500 in the Autonomous Community, 230,200 in the Northern Provinces and 508,900 in Navarre), there were 665,800 who spoke Basque (aged 16 and above). This amounts to 25.7% Basque bilinguals overall, 15.4% passive speakers and 58.9% non-speakers. Compared to the 1991 figures this represents an overall increase from 528,500 (out of a population of 2,371,100 in 1991) to 665,800 (in 2006).

The modern Basque dialects show a high degree of dialectal divergence, sometimes making cross-dialect communication difficult. This is especially true in the case of Bizkaian and Zuberoan

The modern Basque dialects show a high degree of dialectal divergence, sometimes making cross-dialect communication difficult. This is especially true in the case of Bizkaian and Zuberoan

, which are regarded as the most divergent Basque dialects.

Modern Basque dialectology distinguishes five dialects:

These dialects are divided in 11 sub-dialects, their minor varieties being 24.

on the Basque language (especially the lexicon, but also to some degree Basque phonology and grammar) has been much more extensive, there has been some feedback from Basque into these languages as well. In particular Gascon

and Aragonese

, and to a lesser degree Spanish

have been influenced. In the case of Aragonese and Gascon, this has been through substrate

interference following language shift

from Aquitanian

or Basque to a Romance language, affecting all levels of the language, including place names around the Pyrenees.

Although a number of words of alleged Basque origin in the Spanish language are circulated (e.g. anchoa 'anchovis', bizarro 'dashing, galant, spirited', cachorro 'puppy', etc.), most of these have more easily explicable Romance etymologies or not particularly convincing derivations from Basque. Ignoring cultural terms, there is one strong loanword

candidate, ezker, long held to be the source of the Pyrennean and Iberian Romance words for "left (side)" (izquierdo, esquerdo, esquerre, quer, esquer). The lack of initial /r/ in Gascon could arguably be due to a Basque influence but this issue is under-researched.

The other most commonly claimed substrate influences:

The first two features are common, widespread developments in many Romance (and non-Romance) languages, and as a result few linguists put much credence in the substrate proposal. The change of /f/ to /h/, however, occurred historically only in a limited area (Gascony

and Old Castile

) that corresponds almost exactly to areas where heavy Basque bilingualism is assumed, and as a result has been widely postulated (and equally strongly disputed). Substrate theories are often difficult to prove (especially in the case of phonetically plausible changes like /f/ to /h/). As a result, although many arguments have been made on both sides, the debate largely comes down to the a priori tendency on the part of particular linguists to accept or reject substrate arguments.

Examples of arguments against the substrate theory, and possible responses:

Beyond these arguments, a number of nomadic groups of Castile are also said to use or have used Basque words in their jargon, such as the gacería

in Segovia

, the mingaña, the Galician fala dos arxinas

and the Asturian

Xíriga

.

Part of the Romani community in the Basque Country speaks Erromintxela, which is a rare mixed language

, with a Kalderash

Romani

vocabulary and Basque grammar.

s have existed. In the 16th century, Basque sailors used a Basque-Icelandic pidgin

in their contacts with Iceland. Another Basque pidgin arose from contact between Basque whalers and the indigenous inhabitants in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Strait of Belle Isle.

is in the absolutive case

(which is unmarked), and the same case is used for the direct object of a transitive verb

. The subject of the transitive verb is marked differently, with the ergative case

(shown by the suffix -k). This also triggers main and auxiliary verbal agreement.

The auxiliary verb

, which accompanies most main verbs, agrees not only with the subject, but with any direct object and the indirect object present. Among European languages, this polypersonal agreement

is only found in Basque, some languages of the Caucasus

, and Hungarian

(all non-Indo-European). The ergative–absolutive alignment is also unique among European languages, but not rare worldwide.

Consider the phrase:

Martin-ek is the agent (transitive subject), so it is marked with the ergative case ending -k (with an epenthetic

-e-). Egunkariak has an -ak ending which marks plural object (plural absolutive, direct object case). The verb is erosten dizkit, in which erosten is a kind of gerund ("buying") and the auxiliary dizkit means "he/she (does) them for me". This dizkit can be split like this:

The phrase "you buy the newspapers for me" would translate as:

The auxiliary verb is composed as di-zki-da-zue and means 'you pl. (do) them for me'

In spoken Basque, the auxiliary verb is never dropped even if it is redundant: "Zuek niri egunkariak erosten dizkidazue", you pl. buying the newspapers for me. However, the pronouns are almost always dropped: "egunkariak erosten dizkidazue", the newspapers buying be-them-for-me-you(plural). The pronouns are used only to show emphasis: "egunkariak zuek erosten dizkidazue", it is you (pl.) who buy the newspapers for me; or "egunkariak niri erosten dizkidazue", it is me for whom you buy the newspapers.

Modern Basque dialects allow for the conjugation of about fifteen verbs, called synthetic verbs, some only in literary contexts. These can be put in the present and past tenses in the indicative and subjunctive moods, in three tenses in the conditional and potential moods, and in one tense in the imperative. Colloquial Basque, however, only uses indicative present, indicative past, and imperative. Each verb that can be taken intransitively has a nor (absolutive) paradigm and possibly a nor-nori (absolutive–dative) paradigm, as in the sentence Aititeri txapela erori zaio ("The hat fell from grandfather['s head]"). Each verb that can be taken transitively uses those two paradigms for passive-voice contexts in which no agent is mentioned, and also has a nor-nork (absolutive–ergative) paradigm and possibly a nor-nori-nork (absolutive–dative–ergative) paradigm. The last would entail the dizkidazue example above. In each paradigm, each constituent noun can take on any of eight persons, five singular and three plural, with the exception of nor-nori-nork in which the absolutive can only be third person singular or plural. (This draws on a language universal: *"Yesterday the boss presented the committee me" sounds at least odd, if not incorrect.) The most ubiquitous auxiliary, izan, can be used in any of these paradigms, depending on the nature of the main verb.

There are more persons in the singular (5) than in the plural

(3) for synthetic (or filamentous) verbs because of the two familiar persons—informal

masculine and feminine second person singular. The pronoun hi is used for both of them, but where the masculine form of the verb uses a -k, the feminine uses an -n. This is a property not found in Indo-European languages. The entire paradigm of the verb is further augmented by inflecting for "listener" (the allocutive) even if the verb contains no second person constituent. If the situation is one in which the familiar masculine may be used, the form is augmented and modified accordingly; likewise for the familiar feminine.

(Gizon bat etorri da, "a man has come"; gizon bat etorri duk, "a man has come [you are a male close friend]", gizon bat etorri dun, "a man has come [you are a female close friend]", gizon bat etorri duzu, "a man has come [I talk to you]")

Notice that this nearly multiplies the number of possible forms by three. Still, the restriction on contexts in which these forms may be used is strong since all participants in the conversation must be friends of the same sex, and not too far apart in age. Some dialects dispense with the familiar forms entirely. Note, however, that the formal second person singular conjugates in parallel to the other plural forms, perhaps indicating that it used to be the second person plural, started being used as a singular formal, and then the modern second person plural was formulated as an innovation.

All the other verbs in Basque are called periphrastic, behaving much like a participle would in English. These have only three forms total, called aspects

: perfect (various suffixes), habitual (suffix -t[z]en), and future/potential (suffix. -ko/-go). Verbs of Latinate origin in Basque, as well as many other verbs, have a suffix -tu in the perfect, adapted from the Latin -tus suffix. The synthetic verbs also have periphrastic forms, for use in perfects and in simple tenses in which they are deponent.

Within a verb phrase, the periphrastic comes first, followed by the auxiliary.

A Basque noun-phrase is inflected in 17 different ways for case, multiplied by 4 ways for its definiteness and number. These first 68 forms are further modified based on other parts of the sentence, which in turn are inflected for the noun again. It has been estimated that, with two levels of recursion

, a Basque noun may have 458,683 inflected forms.

Basic syntactic construction is subject–object–verb (unlike Spanish, French or English where a subject–verb–object construction is more common). The order of the phrases within a sentence can be changed with thematic purposes, whereas the order of the words within a phrase is usually rigid. As a matter of fact, Basque phrase order is topic–focus, meaning that in neutral sentences (such as sentences to inform someone of a fact or event) the topic is stated first, then the focus. In such sentences, the verb phrase comes at the end. In brief, the focus directly precedes the verb phrase. This rule is also applied in questions, for instance, What is this? can be translated as Zer da hau? or Hau zer da?, but in both cases the question tag zer immediately precedes the verb da. This rule is so important in Basque that, even in grammatical descriptions of Basque in other languages, the Basque word galdegai (focus) is used.

In negative sentences, the order changes. Since the negative particle ez must always directly precede the auxiliary, the topic most often comes beforehand, and the rest of the sentence follows. This includes the periphrastic, if there is one: Aitak frantsesa ikasten du, "Father is learning French," in the negative becomes Aitak ez du frantsesa ikasten, in which ikasten ("learning") is separated from its auxiliary and placed at the end.

Basque has a distinction between laminal

and apical

articulation for the alveolar fricatives and affricates. With the laminal alveolar fricative s̻, the friction occurs across the blade of the tongue, the tongue tip pointing toward the lower teeth. This is the usual /s/ in most European languages. It is written with an orthographic z. By contrast, the voiceless apicoalveolar fricative s̺ is written s; the tip of the tongue points toward the upper teeth and friction occurs at the tip (apex). For example, zu "you" is distinguished from su "fire". The affricate counterparts are written with orthographic tz and ts. So, etzi "the day after tomorrow" is distinguished from etsi "to give up"; atzo "yesterday" is distinguished from atso "old woman".

In the westernmost parts of the Basque country, only the apical s and the alveolar affricate tz are used.

Basque also features postalveolar sibilants (/ʃ/, written x, and /tʃ/, written tx), sounding like English sh and ch.

There are two palatal stops, voiced and unvoiced, as well as a palatal nasal and a palatal lateral (the palatal stops are not present in all dialects). These and the postalveolar sounds are typical of diminutives, which are used frequently in child language and motherese (mainly to show affection rather than size). For example, tanta "drop" vs. ttantta /canca/ "droplet". A few common words, such as txakur /tʃakur/ "dog", use palatal sounds even though in current usage they have lost the diminutive sense; the corresponding non-palatal forms now acquiring an augmentative or pejorative sense: zakur "big dog". Many dialects of Basque exhibit a derived palatalization effect in which coronal onset consonants are changed into the palatal counterpart after the high front vowel /i/. For example, the /n/ in egin "to act" becomes palatal in southern and western dialects when a suffix beginning with a vowel is added: /eɡina/ = [eɡiɲa] "the action", /eɡines/ = [eɡiɲes] "doing".

The letter j has a variety of realizations according to the regional dialect: [j, dʒ, x, ʃ, ɟ, ʝ], as pronounced from west to east in south Bizkaia and coastal Lapurdi, central Bizkaia, east Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, south Navarre, inland Lapurdi and Low Navarre, and Zuberoa, respectively.

The letter h is silent in the Spanish Basque provinces, but pronounced in the French ones. Unified Basque spells it except when it is predictible, in a position following a consonant.

The vowel system is the same as Spanish for most speakers. It consists of five pure vowels, /i e a o u/. Speakers of the Zuberoan dialect also have a sixth, front rounded vowel (represented in writing by ü and pronounced as /y/), as well as a set of contrasting nasalized vowels, indicating a strong influence from Gascon

.

Unless they are recent loanwords (e.g., Ruanda (Rwanda), radar...), words cannot begin with the letter r, and when they are borrowed from elsewhere, the initial r- is changed to err-, more rarely to irr- (irratia [the radio], irrisa [the rice]. This is similar to how in Spanish, words with s+ consonant (such as "state") get an initial e (estado).

, from a weak pitch accent

in the central dialects to a marked stress in some outer dialects, with varying patterns of stress placement. Stress is in general not distinctive (and for historical comparisons not very useful); there are, however, a few instances where stress is phonemic, serving to distinguish between a few pairs of stress-marked words and between some grammatical forms (mainly plurals from other forms). E.g., basóà ("the forest", absolutive case) vs. básoà ("the glass", absolutive case; an adoption from Spanish vaso); basóàk ("the forest", ergative case) vs. básoàk ("the glass", ergative case) vs. básoak ("the forests" or "the glasses", absolutive case).

Given its great deal of variation among dialects, stress is not marked in the standard orthography

and Euskaltzaindia

(the Academy of the Basque Language) only provides general recommendations for a standard placement of stress, basically to place a high-pitched weak stress (weaker than that of Spanish, let alone that of English) on the second syllable of a syntagma

, and a low-pitched even-weaker stress on its last syllable, except in plural forms where stress is moved to the first syllable.

This scheme provides Basque with a distinct musicality which sets its sound apart from the prosodical

patterns of Spanish (which tends to stress the second-to-last syllable). Some Euskaldun berriak ("new Basque-speakers", i.e., second-language Basque-speakers) with Spanish as their first language tend to carry the prosodical patterns of Spanish into their pronunciation of Basque, giving rise to a pronunciation that is considered substandard; e.g., pronouncing nire ama ("my mum") as nire áma (– – ´ –), instead of as niré amà (– ´ – `).

, Spanish

, Gascon

, among others. There is a considerable number of Latin loans (sometimes obscured by being subject to Basque phonology and grammar for centuries), for example: lore ("flower", from florem), errota ("mill", from rotam, "[mill] wheel"), gela ("room", from cellam).

and sometimes ç

and ü

. Basque does not use Cc, Qq, Vv, Ww, Yy for words that have some tradition in this language; nevertheless, the Basque alphabet (established by Euskaltzaindia

) does include them for loanwords:

The phonetically meaningful digraphs

dd, ll, rr, ts, tt, tx, tz are treated as double letters.

All letters and digraphs represent unique phoneme

s. The main exception is when l or n are preceded by i, that in most dialects palatalizes their sound into /ʎ/ and /ɲ/, even if these are not written. Hence, Ikurriña

can also be written Ikurrina without changing the sound, while the proper name Ainhoa

requires the mute h to break the palatalization of the n.

H is mute in most regions, but in the Northeast is pronounced in many places, the main reason for its existence in the Basque alphabet.

Its acceptance was a matter of contention during the standardization since the speakers of the most extended dialects had to learn where to place these h's, silent for them.

In Sabino Arana

's (1865–1903) alphabet, ll and rr were replaced with ĺ

and ŕ

, respectively.

A typically Basque style of lettering is sometimes used for inscriptions.

It derives from the work of stone and wood carvers and is characterized by thick serif

s.

(See Basque fonts available for download in the External Links section.)

The system is, as is the Basque system of counting in general, vigesimal

. Although the system is in theory capable of indicating numbers above 100, most recorded examples do not go above 100 in general. Interestingly, fractions are relatively common, especially 1/2.

The exact systems used vary from area to area but generally follow the same principle with 5 usually being a diagonal line or a curve off the vertical line (a V shape is used when writing a 5 horizontally). Units of ten are usually a horizontal line through the vertical. The twenties are based on a circle with intersecting lines.

This system is not in general use anymore but is occasionally employed for decorative purposes.

Language

Language may refer either to the specifically human capacity for acquiring and using complex systems of communication, or to a specific instance of such a system of complex communication...

of the Basque people

Basque people

The Basques as an ethnic group, primarily inhabit an area traditionally known as the Basque Country , a region that is located around the western end of the Pyrenees on the coast of the Bay of Biscay and straddles parts of north-central Spain and south-western France.The Basques are known in the...

, who inhabit the Basque Country, a region spanning an area in northeastern Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

and southwestern France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

. It is spoken by 25.7% of Basques in all territories (665,800 out of 2,589,600). Of these, 614,000 live in the Spanish part of the Basque country and the remaining 51,800 live in the French part.

In academic discussions of the distribution of Basque in Spain and France, it is customary to refer to three ancient provinces

Northern Basque Country

The French Basque Country or Northern Basque Country situated within the western part of the French department of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques constitutes the north-eastern part of the Basque Country....

in France and four Spanish provinces. Native speakers are concentrated in a contiguous area including parts of the Spanish Autonomous Communities of the Basque Autonomous Community

Basque Country (autonomous community)

The Basque Country is an autonomous community of northern Spain. It includes the Basque provinces of Álava, Biscay and Gipuzkoa, also called Historical Territories....

(Spanish: País Vasco; Euskara: Euskadi) and Navarre

Navarre

Navarre , officially the Chartered Community of Navarre is an autonomous community in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Country, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and Aquitaine in France...

and in the western half of the French Département of Pyrénées-Atlantiques

Pyrénées-Atlantiques

Pyrénées-Atlantiques is a department in the southwest of France which takes its name from the Pyrenees mountains and the Atlantic Ocean.- History :...

. The Autonomous Community of País Vasco/Euskadi is an administrative entity within the binational ethnographic Basque Country incorporating the traditional Spanish provinces of Biscay

Biscay

Biscay is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lord of Biscay. Its capital city is Bilbao...

, Gipuzkoa, and Álava

Álava

Álava is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lord of Álava. Its capital city is Vitoria-Gasteiz which is also the capital of the autonomous community...

, which retain their existence as politico-administrative divisions.

These provinces and many areas of Navarre are heavily populated by ethnic Basques, but the Euskara language had, at least until the 1990s, all but disappeared from most of Álava, western parts of Biscay and central and southern areas of Navarre

Navarre

Navarre , officially the Chartered Community of Navarre is an autonomous community in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Country, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and Aquitaine in France...

. In southwestern France, the ancient Basque-populated provinces were Labourd

Labourd

Labourd is a former French province and part of the present-day Pyrénées Atlantiques département. It is historically one of the seven provinces of the traditional Basque Country....

, Lower Navarre

Lower Navarre

Lower Navarre is a part of the present day Pyrénées Atlantiques département of France. Along with Navarre of Spain, it was once ruled by the Kings of Navarre. Lower Navarre was historically one of the kingdoms of Navarre. Its capital were Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and Saint-Palais...

, and Soule

Soule

Soule is a former viscounty and French province and part of the present day Pyrénées-Atlantiques département...

. They and other regions were consolidated into a single département in 1790 under the name Basses-Pyrénées, a name which persisted until 1970.

A standardized form of the Basque language, called Euskara Batua, was developed by the Basque Language Academy

Euskaltzaindia

Euskaltzaindia is the official academic language regulatory institution which watches over the Basque language. It carries out research on the language, seeks to protect it, and establishes standards of use...

in the late 1960s. Euskara Batua was created so that Basque language could be used—and easily understood by all Basque speakers—in formal situations (education, mass media, literature...), and this is its main use nowadays. This standard Basque is taught and used as a teaching language (as an option, together with standard Spanish) at most educational levels in the Spanish part of the Basque Country, while the intensity, status and funding by state bodies to Basque language instruction varies depending on the area. In France, the Basque language school Seaska and the association for a bilingual (Basque and French) schooling Ikasbi meet a wide range of Basque language educational needs up to the Sixth Form, while often struggling to surmount financial and administrative constraints.

Apart from this standardized version, there are five main Basque dialects: Bizkaian, Gipuzkoan

Gipuzkoan

Gipuzkoan is a dialect of the Basque language spoken mainly in the province of Gipuzkoa in Basque Country but also in a small part of Navarre. It is a central dialect, spoken in the central and eastern part of Gipuzkoa...

, and Upper Navarrese

Upper Navarrese

Upper Navarrese is a dialect of the Basque language spoken in the Navarre community of Spain, as established by linguist Louis Lucien Bonaparte in his famous 1869 map. He actually distinguished two dialects: Meridional and Septentrional...

in Spain, and Navarrese-Lapurdian and Zuberoan

Zuberoan

Souletin , is the Basque dialect spoken in Soule, France.-Name:In English sources, the Basque-based term Zuberoan is sometimes encountered. In Standard Basque, the dialect is known as Zuberera , locally variously as Üskara, Xiberera or Xiberotarra...

(in France). Although they take their names from the mentioned historic provinces, the dialect boundaries are not congruent with province boundaries.

Names of the language

In Basque, the name of the language is officially Euskara (alongside various dialect forms). There are currently three etymological theories of the name Euskara that are taken seriously by linguists and Vasconists which are discussed in detail on the Basque people page.In French the language is normally called basque or, in recent times, euskara. There is a greater variety of Spanish names for the language. Today, it is most commonly referred to as el vasco, la lengua vasca or el euskera. Both terms, vasco and basque, are inherited from Latin ethnonym

Ethnonym

An ethnonym is the name applied to a given ethnic group. Ethnonyms can be divided into two categories: exonyms and autonyms or endonyms .As an example, the ethnonym for...

Vascones which in turn goes back to the Greek term ουασκωνους (ouaskōnous), an ethnonym used by Strabo

Strabo

Strabo, also written Strabon was a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher.-Life:Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus , a city which he said was situated the approximate equivalent of 75 km from the Black Sea...

in his Geographica

Géographica

Géographica is the French-language magazine of the Royal Canadian Geographical Society , published under the Society's French name, the Société géographique royale du Canada . Introduced in 1997, Géographica is not a stand-alone publication, but is published as an irregular supplement to La...

(23 CE, Book III).

The term Vascuence, derived from Latin vasconĭce, has acquired negative connotations over the centuries and is not well liked amongst Basque speakers generally. Its use is documented at least as far back as the 14th century when a law passed in Huesca

Huesca

Huesca is a city in north-eastern Spain, within the autonomous community of Aragon. It is also the capital of the Spanish province of the same name and the comarca of Hoya de Huesca....

in 1349 stated that Item nuyl corridor nonsia usado que faga mercadería ninguna que compre nin venda entre ningunas personas, faulando en algaravia nin en abraych nin en basquenç: et qui lo fara pague por coto XXX sol—essentially penalizing the use of Arabic, Hebrew or Vascuence (Basque) with a fine of 30 sols

French sol

The sol was a coin in use in Ancien Regime France, valued at a 20th of a livre tournois. The sol itself was subdivided into 12 deniers.Over the 17th century the term sol was, apart from in a few instances, progressively replaced by sou, reflecting its pronunciation. In 1787 a sol's buying power was...

.

History and classification

Though geographically surrounded by Indo-EuropeanIndo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a family of several hundred related languages and dialects, including most major current languages of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and South Asia and also historically predominant in Anatolia...

Romance languages, Basque is classified as a language isolate

Language isolate

A language isolate, in the absolute sense, is a natural language with no demonstrable genealogical relationship with other languages; that is, one that has not been demonstrated to descend from an ancestor common with any other language. They are in effect language families consisting of a single...

. It is the last remaining descendant of the pre-Indo-European

Pre-Indo-European

Old Europe is a term coined by archaeologist Marija Gimbutas to describe what she perceives as a relatively homogeneous and widespread pre-Indo-European Neolithic culture in Europe, particularly in Malta and the Balkans....

languages of Western Europe. Consequently, its prehistory may not be reconstructible by means of the comparative method

Comparative method

In linguistics, the comparative method is a technique for studying the development of languages by performing a feature-by-feature comparison of two or more languages with common descent from a shared ancestor, as opposed to the method of internal reconstruction, which analyzes the internal...

except by applying it to differences between dialects within the language. Little is known of its origins but it is likely that an early form of the Basque language was present in Western Europe before the arrival of the Indo-European languages to the area.

Latin inscriptions in Aquitania

Gallia Aquitania

Gallia Aquitania was a province of the Roman Empire, bordered by the provinces of Gallia Lugdunensis, Gallia Narbonensis, and Hispania Tarraconensis...

preserve a number of words with cognates in reconstructed proto-Basque, for instance the personal names Nescato and Cison (neskato and gizon mean "young girl" and "man" respectively in modern Basque). This language is generally referred to as Aquitanian

Aquitanian language

The Aquitanian language was spoken in ancient Aquitaine before the Roman conquest and, probably much later, until the Early Middle Ages....

and is assumed to have been spoken in the area before the Roman

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic was the period of the ancient Roman civilization where the government operated as a republic. It began with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, traditionally dated around 508 BC, and its replacement by a government headed by two consuls, elected annually by the citizens and...

conquests in the western Pyrenees

Pyrenees

The Pyrenees is a range of mountains in southwest Europe that forms a natural border between France and Spain...

. Some authors even argue that the language moved westward during the Late Antiquity

Late Antiquity

Late Antiquity is a periodization used by historians to describe the time of transition from Classical Antiquity to the Middle Ages, in both mainland Europe and the Mediterranean world. Precise boundaries for the period are a matter of debate, but noted historian of the period Peter Brown proposed...

, after the fall of Rome

Decline of the Roman Empire

The decline of the Roman Empire refers to the gradual societal collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Many theories of causality prevail, but most concern the disintegration of political, economic, military, and other social institutions, in tandem with foreign invasions and usurpers from within the...

, into the north part of Hispania

Hispania

Another theory holds that the name derives from Ezpanna, the Basque word for "border" or "edge", thus meaning the farthest area or place. Isidore of Sevilla considered Hispania derived from Hispalis....

in which Basque is spoken today.

Roman neglect of this area allowed Aquitanian to survive while the Iberian

Iberian language

The Iberian language was the language of a people identified by Greek and Roman sources who lived in the eastern and southeastern regions of the Iberian peninsula. The ancient Iberians can be identified as a rather nebulous local culture between the 7th and 1st century BC...

and Tartessian language

Tartessian language

The Tartessian language is the extinct Paleohispanic language of inscriptions in the Southwestern script found in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula: mainly in the south of Portugal , but also in Spain . There are 95 of these inscriptions with the longest having 82 readable signs...

s became extinct. Through the long contact with Romance languages, Basque adopted a sizable number of Romance words. Initially the source was Latin, later Gascon

Gascon language

Gascon is usually considered as a dialect of Occitan, even though some specialists regularly consider it a separate language. Gascon is mostly spoken in Gascony and Béarn in southwestern France and in the Aran Valley of Spain...

(a branch of Occitan) in the northeast, Navarro-Aragonese

Navarro-Aragonese

Navarro-Aragonese was a Romance language spoken south of the middle Pyrenees and in part of the Ebro River basin in the Middle Ages. The language extended over the County of Aragón, Sobrarbe, Ribagorza, the southern plains of Navarre on both banks of the Ebro including La Rioja and the eastern...

in the southeast and Spanish

Spanish language

Spanish , also known as Castilian , is a Romance language in the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several languages and dialects in central-northern Iberia around the 9th century and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castile into central and southern Iberia during the...

in the southwest.

Hypotheses on connections with other languages

The impossibility of linking Basque with its Indo-European neighbors in Europe has inspired many scholars to search for its possible relatives elsewhere. Besides many pseudoscientific comparisons, the appearance of long-range linguistics gave rise to several attempts to connect Basque with geographically very distant language families. All hypotheses on the origin of Basque are controversial, and the suggested evidence is not generally accepted by most linguists. Some of these hypothetical connections are as follows:- IberianIberian languageThe Iberian language was the language of a people identified by Greek and Roman sources who lived in the eastern and southeastern regions of the Iberian peninsula. The ancient Iberians can be identified as a rather nebulous local culture between the 7th and 1st century BC...

: another ancient language once spoken in the peninsula, shows several similarities with AquitanianAquitanian languageThe Aquitanian language was spoken in ancient Aquitaine before the Roman conquest and, probably much later, until the Early Middle Ages....

and Basque. However, there is not enough evidence to distinguish areal contacts from genetic relationship. Iberian itself remains unclassifiedUnclassified languageUnclassified languages are languages whose genetic affiliation has not been established by means of historical linguistics. If this state of affairs continues after significant study of the language and efforts to relate it to other languages, as in the case of Basque, it is termed a language...

. Eduardo Orduña Aznar claims to have established correspondences between Basque and Iberian numerals and noun case markers. - the Ligurian substrate hypothesis proposed in the 19th century by d'Arbois de Joubainville, J. Pokorny, P. Kretschmer and several other linguists encompasses the Basco-Iberian hypothesis.

- GeorgianGeorgian languageGeorgian is the native language of the Georgians and the official language of Georgia, a country in the Caucasus.Georgian is the primary language of about 4 million people in Georgia itself, and of another 500,000 abroad...

: Linking Basque to Kartvelian languages is now widely discredited. The hypothesis was inspired by the existence of the ancient Kingdom of IberiaCaucasian IberiaIberia , also known as Iveria , was a name given by the ancient Greeks and Romans to the ancient Georgian kingdom of Kartli , corresponding roughly to the eastern and southern parts of the present day Georgia...

farther east in the Mediterranean and further by some typological similarities between the two languages. According to J.P. Mallory, in his 1989 book In Search of the Indo-Europeans, the hypothesis was also inspired by a Basque place-name ending in -adze. - Northeast Caucasian languagesNortheast Caucasian languagesThe Northeast Caucasian languages constitute a language family spoken in the Russian republics of Dagestan, Chechnya, Ingushetia, northern Azerbaijan, and in northeastern Georgia, as well as in diaspora populations in Russia, Turkey, and the Middle East...

, such as ChechenChechen languageThe Chechen language is spoken by more than 1.5 million people, mostly in Chechnya and by Chechen people elsewhere. It is a member of the Northeast Caucasian languages.-Classification:...

, are seen by the French linguist Michel Morvan as more likely candidates for a very distant connection. - Dené–Caucasian superfamily: Based on the possible Caucasian link, some linguists, for example John BengtsonJohn BengtsonJohn D. Bengtson is a historical and anthropological linguist. He is a past president and currently a vice-president of the Association for the Study of Language in Prehistory, and has served as editor of the journal Mother Tongue...

and Merritt RuhlenMerritt RuhlenMerritt Ruhlen is an American linguist known for his work on the classification of languages and what this reveals about the origin and evolution of modern humans. Amongst other linguists, Ruhlen's work is recognized as standing outside the mainstream of comparative-historical linguistics...

, have proposed including Basque in the Dené–Caucasian superfamily of languages, but this proposed superfamily includes languages from North America and Eurasia, and its existence is highly controversial. - Vasconic substratum hypothesis: This proposal, by the German linguist Theo VennemannTheo VennemannTheo Vennemann is a German linguist known best for his work on historical linguistics, especially for his disputed theories of a Vasconic substratum and an Atlantic superstratum of European languages. He also suggests that the High German consonant shift was already completed in the early 1st...

, claims that there is enough toponymical evidence to conclude that Basque is the only survivor of a larger family that once extended throughout most of Europe, and has also left its mark in modern Indo-European languagesIndo-European languagesThe Indo-European languages are a family of several hundred related languages and dialects, including most major current languages of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and South Asia and also historically predominant in Anatolia...

spoken in Europe.

Geographic distribution

Basque Country (historical territory)

The Basque Country is the name given to the home of the Basque people in the western Pyrenees that spans the border between France and Spain on the Atlantic coast....

, or Euskal Herria in Basque. Toponyms show that the Basque language used to be spoken further eastward in the Pyrenees than today. An example is the Aran Valley (now a Gascon

Gascon language

Gascon is usually considered as a dialect of Occitan, even though some specialists regularly consider it a separate language. Gascon is mostly spoken in Gascony and Béarn in southwestern France and in the Aran Valley of Spain...

-speaking part of Catalonia

Catalonia

Catalonia is an autonomous community in northeastern Spain, with the official status of a "nationality" of Spain. Catalonia comprises four provinces: Barcelona, Girona, Lleida, and Tarragona. Its capital and largest city is Barcelona. Catalonia covers an area of 32,114 km² and has an...

), for (h)aran is the Basque word for "valley". However, the growing influence of Latin began to drive Basque out from the less mountainous portions of the region.

The Reconquista

Reconquista

The Reconquista was a period of almost 800 years in the Middle Ages during which several Christian kingdoms succeeded in retaking the Muslim-controlled areas of the Iberian Peninsula broadly known as Al-Andalus...

temporarily counteracted this tendency when the Christian lords called on northern Iberian peoples – Basques, Asturians, and "Franks

Franks

The Franks were a confederation of Germanic tribes first attested in the third century AD as living north and east of the Lower Rhine River. From the third to fifth centuries some Franks raided Roman territory while other Franks joined the Roman troops in Gaul. Only the Salian Franks formed a...

" – to colonize the new conquests. The Basque language became the main everyday language, while other languages like Spanish

Spanish language

Spanish , also known as Castilian , is a Romance language in the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several languages and dialects in central-northern Iberia around the 9th century and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castile into central and southern Iberia during the...

, Gascon

Gascon language

Gascon is usually considered as a dialect of Occitan, even though some specialists regularly consider it a separate language. Gascon is mostly spoken in Gascony and Béarn in southwestern France and in the Aran Valley of Spain...

, French

French language

French is a Romance language spoken as a first language in France, the Romandy region in Switzerland, Wallonia and Brussels in Belgium, Monaco, the regions of Quebec and Acadia in Canada, and by various communities elsewhere. Second-language speakers of French are distributed throughout many parts...

, or Latin were preferred for the administration and high education.

Basque experienced a rapid decline in Alava and Navarre during the 19th century. However, the rise of Basque nationalism

Basque nationalism

Basque nationalism is a political movement advocating for either further political autonomy or, chiefly, full independence of the Basque Country in the wider sense...

spurred increased interest in the language as a sign of ethnic identity, and with the establishment of autonomous governments, it has recently made a modest comeback. Basque-language schools have brought the language to areas such as Encartaciones and the Navarrese Ribera, where it may have disappeared as a native language in the Middle Ages.

Official status

Historically, Latin or Romance languages have been the official languages in this region.However, Basque was explicitly recognized in some areas. For instance, the local charter

Fuero

Fuero , Furs , Foro and Foru is a Spanish legal term and concept.The word comes from Latin forum, an open space used as market, tribunal and meeting place...

of the Basque-colonized

Reconquista

The Reconquista was a period of almost 800 years in the Middle Ages during which several Christian kingdoms succeeded in retaking the Muslim-controlled areas of the Iberian Peninsula broadly known as Al-Andalus...

Ojacastro

Ojacastro

Ojacastro is a village in the province and autonomous community of La Rioja, Spain....

valley (now in La Rioja

La Rioja (Spain)

La Rioja is an autonomous community and a province of northern Spain. Its capital is Logroño. Other cities and towns in the province include Calahorra, Arnedo, Alfaro, Haro, Santo Domingo de la Calzada, and Nájera.-History:...

) allowed the inhabitants to use Basque in legal processes in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Today Basque holds co-official language status in the Basque regions of Spain: the full autonomous community of the Basque Country

Basque Country (autonomous community)

The Basque Country is an autonomous community of northern Spain. It includes the Basque provinces of Álava, Biscay and Gipuzkoa, also called Historical Territories....

and some parts of Navarre

Navarre

Navarre , officially the Chartered Community of Navarre is an autonomous community in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Country, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and Aquitaine in France...

. Basque has no official standing in the Northern Basque Country

Northern Basque Country

The French Basque Country or Northern Basque Country situated within the western part of the French department of the Pyrénées-Atlantiques constitutes the north-eastern part of the Basque Country....

of France and French citizens are barred from officially using Basque in a French court of law. However, the use of Basque by Spanish nationals in French courts is allowed (with translation), as Basque is officially recognized on the other side of the border.

The positions of the various existing governments differ with regard to the promotion of Basque in areas where Basque is commonly spoken. The language has official status in those territories that are within the Basque Autonomous Community, where it is spoken and promoted heavily, but only partially in Navarre. Here the "Ley del Vascuence" ("Law of Basque"), seen as contentious by many Basques, divides Navarre into three language areas: Basque-speaking, non-Basque-speaking, and mixed. The support for the language and the linguistic rights of citizens vary depending on which of the three areas you are in.

Demographics

The 2006 sociolinguistic survey of all Basque provinces showed that in 2006 of all people aged 16 and above:- in the Basque Autonomous Community, 30.1% were fluent Basque speakers, 18.3% passive speakersPassive speakers (language)A passive speaker is someone who has had enough exposure to a language in childhood to have a native-like comprehension of it, but has little or no active command of it....

and 51.5% did not speak Basque. The percentage was highest in Gipuzkoa (49.1% speakers) and lowest in Álava (14.2%). These results represent an increase on previous years (29.5% in 2001, 27.7% in 1996 and 24.1% in 1991). The highest percentage of speakers can now be found in the 16-24 age range (57.5%) vs 25.0% in the 65+ age range. The percentage of fluent speakers turns out to be even higher if those under 16 are also taken into account, given that the proportion of bilinguals is particularly high in this age group (76.7% of those aged between 10 and 14 and 72.4% of those aged 5-9): 37.5% of the population aged 6 and above in the whole Basque Autonomous Community, 25.0% in Álava, 31.3% in Biscay and 53.3% in Gipuzkoa. - in Iparralde, 22.5% were fluent Basque speakers, 8.6% passive speakers and 68.9% did not speak Basque. The percentage was highest in Labourd and Soule (55.5% speakers) and lowest in the BayonneBayonneBayonne is a city and commune in south-western France at the confluence of the Nive and Adour rivers, in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department, of which it is a sub-prefecture...

-AngletAngletAnglet is a commune in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques department in Aquitaine in south-western France. The town's name is pronounced [ãglet]; i.e...

-BiarritzBiarritzBiarritz is a city which lies on the Bay of Biscay, on the Atlantic coast, in south-western France. It is a luxurious seaside town and is popular with tourists and surfers....

conurbation (8.8%). These results represent another decrease on previous years (24.8% in 2001 and 26.4 in 1996). The highest percentage of speakers is in the 65+ age range (32.4%). The lowest percentage is found in the 25-34 age range (11.6%) but there is a slight increase in the 16-24 age range (16.1%) - in Navarre 11.1% were fluent Basque speakers, 7.6% passive speakers and 81.3% did not speak Basque. The percentage was highest in the so-called Basque Zone in the North (60.1% speakers) and lowest in the non-Basque Zone in the South (1.9%). These results represent a slight increase on previous years (10.3% in 2001, 9.6% in 1996 and 9.5% in 1991). The highest percentage of speakers can now be found in the 16-24 age range (19.1%) vs 9.1% in the 65+ age range.

Taken together, in 2006 out of a total population of 2,589,600 (1,850,500 in the Autonomous Community, 230,200 in the Northern Provinces and 508,900 in Navarre), there were 665,800 who spoke Basque (aged 16 and above). This amounts to 25.7% Basque bilinguals overall, 15.4% passive speakers and 58.9% non-speakers. Compared to the 1991 figures this represents an overall increase from 528,500 (out of a population of 2,371,100 in 1991) to 665,800 (in 2006).

Dialects

Zuberoan

Souletin , is the Basque dialect spoken in Soule, France.-Name:In English sources, the Basque-based term Zuberoan is sometimes encountered. In Standard Basque, the dialect is known as Zuberera , locally variously as Üskara, Xiberera or Xiberotarra...

, which are regarded as the most divergent Basque dialects.

Modern Basque dialectology distinguishes five dialects:

- The Western dialect

- The Central dialect

- Upper Navarrese

- Lower Navarrese-Lapurdian

- Souletin (Zuberoan)

These dialects are divided in 11 sub-dialects, their minor varieties being 24.

Influence on other languages

Although the influence of the neighboring Romance languagesRomance languages

The Romance languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family, more precisely of the Italic languages subfamily, comprising all the languages that descend from Vulgar Latin, the language of ancient Rome...

on the Basque language (especially the lexicon, but also to some degree Basque phonology and grammar) has been much more extensive, there has been some feedback from Basque into these languages as well. In particular Gascon

Gascon language

Gascon is usually considered as a dialect of Occitan, even though some specialists regularly consider it a separate language. Gascon is mostly spoken in Gascony and Béarn in southwestern France and in the Aran Valley of Spain...

and Aragonese

Aragonese language

Aragonese is a Romance language now spoken in a number of local varieties by between 10,000 and 30,000 people over the valleys of the Aragón River, Sobrarbe and Ribagorza in Aragon, Spain...

, and to a lesser degree Spanish

Spanish language

Spanish , also known as Castilian , is a Romance language in the Ibero-Romance group that evolved from several languages and dialects in central-northern Iberia around the 9th century and gradually spread with the expansion of the Kingdom of Castile into central and southern Iberia during the...

have been influenced. In the case of Aragonese and Gascon, this has been through substrate

Substratum

In linguistics, a stratum or strate is a language that influences, or is influenced by another through contact. A substratum is a language which has lower power or prestige than another, while a superstratum is the language that has higher power or prestige. Both substratum and superstratum...

interference following language shift

Language shift

Language shift, sometimes referred to as language transfer or language replacement or assimilation, is the progressive process whereby a speech community of a language shifts to speaking another language. The rate of assimilation is the percentage of individuals with a given mother tongue who speak...

from Aquitanian

Aquitanian language

The Aquitanian language was spoken in ancient Aquitaine before the Roman conquest and, probably much later, until the Early Middle Ages....

or Basque to a Romance language, affecting all levels of the language, including place names around the Pyrenees.

Although a number of words of alleged Basque origin in the Spanish language are circulated (e.g. anchoa 'anchovis', bizarro 'dashing, galant, spirited', cachorro 'puppy', etc.), most of these have more easily explicable Romance etymologies or not particularly convincing derivations from Basque. Ignoring cultural terms, there is one strong loanword

Loanword

A loanword is a word borrowed from a donor language and incorporated into a recipient language. By contrast, a calque or loan translation is a related concept where the meaning or idiom is borrowed rather than the lexical item itself. The word loanword is itself a calque of the German Lehnwort,...

candidate, ezker, long held to be the source of the Pyrennean and Iberian Romance words for "left (side)" (izquierdo, esquerdo, esquerre, quer, esquer). The lack of initial /r/ in Gascon could arguably be due to a Basque influence but this issue is under-researched.

The other most commonly claimed substrate influences:

- the Old Spanish merger of /v/ and /b/.

- the simple five vowel system.

- change of initial /f/ into /h/ (e.g. fablar → hablar, with Old Basque lacking /f/).

The first two features are common, widespread developments in many Romance (and non-Romance) languages, and as a result few linguists put much credence in the substrate proposal. The change of /f/ to /h/, however, occurred historically only in a limited area (Gascony

Gascony

Gascony is an area of southwest France that was part of the "Province of Guyenne and Gascony" prior to the French Revolution. The region is vaguely defined and the distinction between Guyenne and Gascony is unclear; sometimes they are considered to overlap, and sometimes Gascony is considered a...

and Old Castile

Old Castile

Old Castile is a historic region of Spain, which included territory that later corresponded to the provinces of Santander , Burgos, Logroño , Soria, Segovia, Ávila, Valladolid, Palencia....

) that corresponds almost exactly to areas where heavy Basque bilingualism is assumed, and as a result has been widely postulated (and equally strongly disputed). Substrate theories are often difficult to prove (especially in the case of phonetically plausible changes like /f/ to /h/). As a result, although many arguments have been made on both sides, the debate largely comes down to the a priori tendency on the part of particular linguists to accept or reject substrate arguments.

Examples of arguments against the substrate theory, and possible responses:

- Spanish did not fully shift /f/ to /h/, instead, it has preserved /f/ before consonants such as /w/ and /ɾ/ (cf fuerte, frente). (On the other hand, the occurrence of [f] in these words might be a secondary development from an earlier sound such as [h] or [ɸ]. Gascon does have /h/ in these words, which might reflect the original situation.)

- Evidence of Arabic loanwords in Castilian points to /f/ continuing to exist long after a Basque substrate might have had any effect on Castilian. (On the other hand, the occurrence of /f/ in these words might be a late development. Many languages have come to accept new phonemes from other languages after a period of significant influence. For example, French lost /h/ but later regained it as a result of Germanic influence, and has recently gained /ŋ/ as a result of English influence.)

- Basque regularly developed Latin /f/ into /b/.

- The same change also occurs in parts of Sardinia, Italy and the Romance languages of the Balkans where no Basque substrate can be reasonably argued for. (On the other hand, the fact that the same change might have occurred elsewhere independently does not disprove substrate influence. Furthermore, parts of Sardinia also have prothetic /a/ or /e/ before initial /r/, just as in Basque and Gascon, which may actually argue for some type of influence between both areas.)

Beyond these arguments, a number of nomadic groups of Castile are also said to use or have used Basque words in their jargon, such as the gacería

Gacería

Gacería is the name of a slang or argot employed by the trilleros and the briqueros in the village of Cantalejo, in the Spanish province of Segovia...

in Segovia

Segovia (province)

Segovia is a province of central/northern Spain, in the southern part of the autonomous community of Castile and León. It is bordered by the provinces of Burgos, Soria, Guadalajara, Madrid, Ávila, and Valladolid....

, the mingaña, the Galician fala dos arxinas

Fala dos arxinas

Fala dos arxinas is the name of an argot employed by stonecutters in Galicia, Spain, particularly in the area of Pontevedra, based on galician language...

and the Asturian

Asturias

The Principality of Asturias is an autonomous community of the Kingdom of Spain, coextensive with the former Kingdom of Asturias in the Middle Ages...

Xíriga

Xíriga

Xíriga is an occupation-related cant on Asturian developed by the tejeros of Llanes and Ribadesella in Asturias. The tejeros were migrant workers in brick or clay, usually poor, who contracted themselves out for work sometimes in distant towns...

.

Part of the Romani community in the Basque Country speaks Erromintxela, which is a rare mixed language

Mixed language

A mixed language is a language that arises through the fusion of two source languages, normally in situations of thorough bilingualism, so that it is not possible to classify the resulting language as belonging to either of the language families that were its source...

, with a Kalderash

Kalderash

The Kalderash are a subgroup of the Romani people, from the Roma meta-group. They were traditionally smiths and metal workers and speak a number of Romani dialects grouped together under the term Kalderash Romani, a sub-group of Vlax Romani.-Etymology:The name Kalderash The Kalderash (also spelled...

Romani

Romani language

Romani or Romany, Gypsy or Gipsy is any of several languages of the Romani people. They are Indic, sometimes classified in the "Central" or "Northwestern" zone, and sometimes treated as a branch of their own....

vocabulary and Basque grammar.

Basque pidgins

A number of Basque-based or Basque-influenced pidginPidgin

A pidgin , or pidgin language, is a simplified language that develops as a means of communication between two or more groups that do not have a language in common. It is most commonly employed in situations such as trade, or where both groups speak languages different from the language of the...

s have existed. In the 16th century, Basque sailors used a Basque-Icelandic pidgin

Basque-Icelandic pidgin

The Basque-Icelandic pidgin was a pidgin spoken in Iceland in the 17th century. It developed due to the contact that Basque traders had with the Icelandic locals, probably in Vestfirðir...

in their contacts with Iceland. Another Basque pidgin arose from contact between Basque whalers and the indigenous inhabitants in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Strait of Belle Isle.

Grammar

Basque is an ergative–absolutive language. The subject of an intransitive verbIntransitive verb

In grammar, an intransitive verb is a verb that has no object. This differs from a transitive verb, which takes one or more objects. Both classes of verb are related to the concept of the transitivity of a verb....

is in the absolutive case

Absolutive case

The absolutive case is the unmarked grammatical case of a core argument of a verb which is used as the citation form of a noun.-In ergative languages:...

(which is unmarked), and the same case is used for the direct object of a transitive verb

Transitive verb

In syntax, a transitive verb is a verb that requires both a direct subject and one or more objects. The term is used to contrast intransitive verbs, which do not have objects.-Examples:Some examples of sentences with transitive verbs:...

. The subject of the transitive verb is marked differently, with the ergative case

Ergative case

The ergative case is the grammatical case that identifies the subject of a transitive verb in ergative-absolutive languages.-Characteristics:...

(shown by the suffix -k). This also triggers main and auxiliary verbal agreement.

The auxiliary verb

Auxiliary verb

In linguistics, an auxiliary verb is a verb that gives further semantic or syntactic information about a main or full verb. In English, the extra meaning provided by an auxiliary verb alters the basic meaning of the main verb to make it have one or more of the following functions: passive voice,...

, which accompanies most main verbs, agrees not only with the subject, but with any direct object and the indirect object present. Among European languages, this polypersonal agreement

Polypersonal agreement

In linguistics, polypersonal agreement or polypersonalism is the agreement of a verb with more than one of its arguments...

is only found in Basque, some languages of the Caucasus

Languages of the Caucasus

The languages of the Caucasus are a large and extremely varied array of languages spoken by more than ten million people in and around the Caucasus Mountains, which lie between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea....

, and Hungarian

Hungarian language

Hungarian is a Uralic language, part of the Ugric group. With some 14 million speakers, it is one of the most widely spoken non-Indo-European languages in Europe....

(all non-Indo-European). The ergative–absolutive alignment is also unique among European languages, but not rare worldwide.

Consider the phrase:

-

Martin-ek egunkari-ak erosten di-zki-t Martin-ERG newspaper-PL buy-GER AUX.(s)he/it/they.OBJ-PL.OBJ-me.IO [(s)he/it_SBJ] - "Martin buys the newspapers for me."

Martin-ek is the agent (transitive subject), so it is marked with the ergative case ending -k (with an epenthetic

Epenthesis

In phonology, epenthesis is the addition of one or more sounds to a word, especially to the interior of a word. Epenthesis may be divided into two types: excrescence, for the addition of a consonant, and anaptyxis for the addition of a vowel....

-e-). Egunkariak has an -ak ending which marks plural object (plural absolutive, direct object case). The verb is erosten dizkit, in which erosten is a kind of gerund ("buying") and the auxiliary dizkit means "he/she (does) them for me". This dizkit can be split like this:

- di- is used in the present tense when the verb has a subject (ergative), a direct object (absolutive), and an indirect object, and the object is him/her/it/them.

- -zki- means the absolutive (in this case the newspapers) is plural, if it were singular there would be no infix; and

- -t or '-da-' means "to me/for me" (indirect object).

- in this instance there is no suffix after -t. A zero suffix in this position indicates that the ergative (the subject) is third person singular (he/she/it).

The phrase "you buy the newspapers for me" would translate as:

-

Zu-ek egunkari-ak erosten di-zki-da-zue you-ERG newspaper-PL buy-GER AUX.(s)he/it/they.OBJ-PL.OBJ-me.IO-you(pl.).SBJ

The auxiliary verb is composed as di-zki-da-zue and means 'you pl. (do) them for me'

- di- indicates that the main verb is transitive and in the present tense

- -zki- indicates that the direct object is plural

- -da- indicates that the indirect object is me (to me/for me) {-t becomes -da- when not final.}

- -zue indicates that the subject is you (plural)

In spoken Basque, the auxiliary verb is never dropped even if it is redundant: "Zuek niri egunkariak erosten dizkidazue", you pl. buying the newspapers for me. However, the pronouns are almost always dropped: "egunkariak erosten dizkidazue", the newspapers buying be-them-for-me-you(plural). The pronouns are used only to show emphasis: "egunkariak zuek erosten dizkidazue", it is you (pl.) who buy the newspapers for me; or "egunkariak niri erosten dizkidazue", it is me for whom you buy the newspapers.

Modern Basque dialects allow for the conjugation of about fifteen verbs, called synthetic verbs, some only in literary contexts. These can be put in the present and past tenses in the indicative and subjunctive moods, in three tenses in the conditional and potential moods, and in one tense in the imperative. Colloquial Basque, however, only uses indicative present, indicative past, and imperative. Each verb that can be taken intransitively has a nor (absolutive) paradigm and possibly a nor-nori (absolutive–dative) paradigm, as in the sentence Aititeri txapela erori zaio ("The hat fell from grandfather['s head]"). Each verb that can be taken transitively uses those two paradigms for passive-voice contexts in which no agent is mentioned, and also has a nor-nork (absolutive–ergative) paradigm and possibly a nor-nori-nork (absolutive–dative–ergative) paradigm. The last would entail the dizkidazue example above. In each paradigm, each constituent noun can take on any of eight persons, five singular and three plural, with the exception of nor-nori-nork in which the absolutive can only be third person singular or plural. (This draws on a language universal: *"Yesterday the boss presented the committee me" sounds at least odd, if not incorrect.) The most ubiquitous auxiliary, izan, can be used in any of these paradigms, depending on the nature of the main verb.

There are more persons in the singular (5) than in the plural

Plural

In linguistics, plurality or [a] plural is a concept of quantity representing a value of more-than-one. Typically applied to nouns, a plural word or marker is used to distinguish a value other than the default quantity of a noun, which is typically one...

(3) for synthetic (or filamentous) verbs because of the two familiar persons—informal

T-V distinction

In sociolinguistics, a T–V distinction is a contrast, within one language, between second-person pronouns that are specialized for varying levels of politeness, social distance, courtesy, familiarity, or insult toward the addressee....

masculine and feminine second person singular. The pronoun hi is used for both of them, but where the masculine form of the verb uses a -k, the feminine uses an -n. This is a property not found in Indo-European languages. The entire paradigm of the verb is further augmented by inflecting for "listener" (the allocutive) even if the verb contains no second person constituent. If the situation is one in which the familiar masculine may be used, the form is augmented and modified accordingly; likewise for the familiar feminine.

(Gizon bat etorri da, "a man has come"; gizon bat etorri duk, "a man has come [you are a male close friend]", gizon bat etorri dun, "a man has come [you are a female close friend]", gizon bat etorri duzu, "a man has come [I talk to you]")

Notice that this nearly multiplies the number of possible forms by three. Still, the restriction on contexts in which these forms may be used is strong since all participants in the conversation must be friends of the same sex, and not too far apart in age. Some dialects dispense with the familiar forms entirely. Note, however, that the formal second person singular conjugates in parallel to the other plural forms, perhaps indicating that it used to be the second person plural, started being used as a singular formal, and then the modern second person plural was formulated as an innovation.

All the other verbs in Basque are called periphrastic, behaving much like a participle would in English. These have only three forms total, called aspects

Grammatical aspect

In linguistics, the grammatical aspect of a verb is a grammatical category that defines the temporal flow in a given action, event, or state, from the point of view of the speaker...

: perfect (various suffixes), habitual (suffix -t[z]en), and future/potential (suffix. -ko/-go). Verbs of Latinate origin in Basque, as well as many other verbs, have a suffix -tu in the perfect, adapted from the Latin -tus suffix. The synthetic verbs also have periphrastic forms, for use in perfects and in simple tenses in which they are deponent.

Within a verb phrase, the periphrastic comes first, followed by the auxiliary.

A Basque noun-phrase is inflected in 17 different ways for case, multiplied by 4 ways for its definiteness and number. These first 68 forms are further modified based on other parts of the sentence, which in turn are inflected for the noun again. It has been estimated that, with two levels of recursion

Recursion

Recursion is the process of repeating items in a self-similar way. For instance, when the surfaces of two mirrors are exactly parallel with each other the nested images that occur are a form of infinite recursion. The term has a variety of meanings specific to a variety of disciplines ranging from...

, a Basque noun may have 458,683 inflected forms.

Basic syntactic construction is subject–object–verb (unlike Spanish, French or English where a subject–verb–object construction is more common). The order of the phrases within a sentence can be changed with thematic purposes, whereas the order of the words within a phrase is usually rigid. As a matter of fact, Basque phrase order is topic–focus, meaning that in neutral sentences (such as sentences to inform someone of a fact or event) the topic is stated first, then the focus. In such sentences, the verb phrase comes at the end. In brief, the focus directly precedes the verb phrase. This rule is also applied in questions, for instance, What is this? can be translated as Zer da hau? or Hau zer da?, but in both cases the question tag zer immediately precedes the verb da. This rule is so important in Basque that, even in grammatical descriptions of Basque in other languages, the Basque word galdegai (focus) is used.

In negative sentences, the order changes. Since the negative particle ez must always directly precede the auxiliary, the topic most often comes beforehand, and the rest of the sentence follows. This includes the periphrastic, if there is one: Aitak frantsesa ikasten du, "Father is learning French," in the negative becomes Aitak ez du frantsesa ikasten, in which ikasten ("learning") is separated from its auxiliary and placed at the end.

Phonology

| Labial Labial consonant Labial consonants are consonants in which one or both lips are the active articulator. This precludes linguolabials, in which the tip of the tongue reaches for the posterior side of the upper lip and which are considered coronals... |