Dutch Revolt

Encyclopedia

The Dutch Revolt or the Revolt of the Netherlands (1566 or 1568–1609)This article adopts 1568 as the starting date of the war, as this was the year of the first battles between armies. However, since there is a long period of Protestant vs. Catholic (establishment) unrest leading to this war, it is not easy to give an exact date when the war started.

The first open violence that would lead to the war was the 1566 iconoclasm, and sometimes the first Spanish repressions of the riots (i.e. battle of Oosterweel

, 1567) are considered the starting point. Most accounts cite the 1568 invasions of armies of mercenaries paid by William of Orange as the official start of the war; this article adopts that point of view. Alternatively, the start of the war is sometimes set at the capture of Brielle

by the Gueux in 1572. was the partially successful revolt of the Protestant Seventeen Provinces

of the defunct Duchy of Burgundy

in the Low Countries

against the ardent militant religious policies of Roman Catholicism pressed by both Charles V and his son Philip II of Spanish Empire

. The religious 'clash of cultures

' built up gradually but inexorably into outbursts of violence against the perceived repression of the Spanish Crown. These tensions marked the beginning of the Thirty Years' War

and led to the formation of the independent Dutch Republic

. The first leader was William of Orange

, followed by several of his descendants and relations. This revolt was one of the first successful secession

s in Europe, and led to one of the first European republics of the modern era, the United Provinces.

Spain was initially successful in suppressing the rebellion. In 1572, however, the rebels captured Brielle

and the rebellion resurged. The northern provinces became independent, first de facto

, and in 1648 de jure

. During the revolt, the United Provinces of the Netherlands, better known as the Dutch Republic

, rapidly grew to become a world power through its merchant shipping and experienced a period of economic, scientific, and cultural growth. The Southern Netherlands

(situated in modern-day Belgium

, Luxembourg

, northern France

and southern Netherlands; see Spanish Netherlands and French Netherlands) remained under Spanish rule. The continuous heavy-handed rule by the Spanish in the south caused many of its financial, intellectual, and cultural elite to flee north, contributing to the success of the Dutch Republic. The Dutch imposed a rigid blockade on the southern provinces which prevented Baltic grain relieving famine in the southern towns, especially in the years 1587-9. Additionally, by the end of the war in 1648 large areas of the Southern Netherlands had been lost to France which had, under the guidance of Cardinal Richelieu and Louis XIII of France

, allied itself with the Dutch Republic in the 1630s against Spain.

The first phase of the conflict can be considered to be the Dutch War of Independence. The focus of the latter phase was to gain official recognition of the already de facto independence of the United Provinces. This phase coincided with the rise of the Dutch Republic as a major power and the founding of the Dutch Empire

.

expanded their original territory by adding to it a series of fiefdoms, including the Seventeen Provinces

. Although Burgundy

itself had been lost to France in 1477, the Burgundian Netherlands were still intact when Charles V

was born in Ghent

in 1500. He was raised in the Netherlands and spoke fluent Dutch, French, Spanish, and some German. In 1506 he became lord of the Burgundian states, among which were the Netherlands. Subsequently, in 1516, he inherited several titles, including the combined kingdoms of Aragon

, and Castile and León

which had become a worldwide empire with the Spanish colonization of the Americas

. In 1519 he became ruler of the Habsburg empire, and he gained the title Holy Roman Emperor

in 1530. Although Friesland

and Guelders

offered prolonged resistance (under Grutte Pier

and Charles of Egmond, respectively), virtually all of the Netherlands had been incorporated into the Habsburg domains by the early 1540s.

had long been a very wealthy region, and had been coveted by the French kings for a long time. The other Netherlands had also grown into wealthy and entrepreneur

ial regions within the empire. Charles V

's empire became a worldwide empire with large American and European territories. The latter were, however, distributed throughout Europe. Control and defence of these were hampered by the disparateness of the territories and huge length of the empire's borders. This large realm was almost continuously at war with its neighbours in its European heartlands, most notably against France in the Italian Wars

and against the Turks

in the Mediterranean Sea

. Further wars were fought against Protestant princes in Germany

. The Netherlands paid heavy taxes to fund these wars, but perceived them as unnecessary and sometimes downright harmful, because they were directed against their most important trading partners.

, felt it was their duty to fight Protestantism, which was considered a heresy

by the Catholic Church. The harsh measures led to increasing grievances in the Netherlands, where the local governments had embarked on a course of peaceful coexistence. In the second half of the century, the situation escalated. Philip sent troops to crush the rebellion and make the Netherlands once more a Catholic region.

The Dutch Protestants compared their humble lifestyle favorably with the supposedly luxurious habits of the ecclesiastical nobility.

Part of the shifting balance of power in the late Middle Ages meant that besides the local nobility, many of the Dutch administrators by now were not traditional aristocrat

Part of the shifting balance of power in the late Middle Ages meant that besides the local nobility, many of the Dutch administrators by now were not traditional aristocrat

s, but instead stemmed from non-noble families that had risen in status over the last centuries. By the 15th century, Brussels

had thus become the de facto capital of the Seventeen Provinces.

Dating back to the Middle Ages the districts of the Netherlands, represented by its nobility and the wealthy city-dwelling merchants still had a large measure of autonomy in appointing its administrators. Charles V and Philip II set out to improve the management of the empire by increasing the authority of the central government in matters like law and taxes, a policy which caused suspicion both among the nobility and the merchant class. An example of this is the takeover of power in the city of Utrecht

in 1528 when Charles V supplanted the council of guild

masters governing the city by his own stadtholder

, who took over worldly powers in the whole province of Utrecht from the archbishop of Utrecht

. Charles ordered the construction of the heavily fortified castle of Vredenburg

, for defence against the Duchy of Gelre and to control the citizens of Utrecht.

Under the governorship of Mary of Hungary (1531–1555), traditional power had for a large part been taken away both from the stadtholders of the provinces and from the high noblemen, who had been replaced by professional jurists in the Council of State

.

. Charles, despite his harsh actions, had been seen as a ruler empathetic to the needs of the Netherlands. Philip, on the other hand, was raised in Spain and spoke neither Dutch nor French. During Philip's reign, tensions flared in the Netherlands over heavy taxation, suppression of Protestantism, and centralisation efforts. The growing conflict would reach a boiling point and would lead ultimately to the war of independence.

as governor of the Netherlands. He continued the policy of his father of appointing members of the high nobility of the Netherlands to the Raad van State (Council of State), the governing body of the seventeen Netherlands, that advised her. He made his confidant Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle

head of that Council. However, already in 1558 the States of the provinces and the States-General of the Netherlands

started to contradict Philip's wishes, by objecting to his tax proposals and by demanding, with eventual success, the withdrawal of Spanish troops which had been left by Philip to guard the Southern Netherlands' borders with France, but which they saw as a threat to their own independence (1559–1561). Subsequent reforms met with much opposition, which was mainly directed at Granvelle. Petitions to King Philip by the high nobility went unanswered. Some of the most influential nobles, including Lamoral, Count of Egmont

, Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn

, and William the Silent

, withdrew from the Council of State until Philip recalled Granvelle. In late 1564, the nobles had noticed the growing power of the reformation and urged Philip to come up with realistic measures to prevent violence. Philip answered that sterner measures could be the only answer. Subsequently Egmont, Horne and Orange withdrew once more from the Council and Bergen and Meghem resigned their Stadholdership. During the same period, the religious protests were increasing in spite of increased oppression. In 1566, a league of about 400 members of the nobility presented a petition to the governor Margaret of Parma

, to suspend persecution until the rest had returned. One of Margaret's courtiers, Count Berlaymont

, called the presentation of this petition an act of 'beggars' (French gueux), a name taken up as an honour by the petitioners (Geuzen

). The petition was sent on to Philip for a final verdict.

The atmosphere in the Netherlands was tense due to the rebellion preaching of Calvinist leaders, hunger after the bad harvest of 1565, and economic difficulties due to the Northern Seven Years' War

The atmosphere in the Netherlands was tense due to the rebellion preaching of Calvinist leaders, hunger after the bad harvest of 1565, and economic difficulties due to the Northern Seven Years' War

. Early August 1566, a monastery church at Steenvoorde

in Flanders (now in Northern France) was sacked by a mob led by the preacher Sebastian Matte. This incident was followed by similar riots elsewhere in Flanders, and before long the Netherlands had become the scene of the Beeldenstorm

, a riotous iconoclastic

movement by Calvinists, who stormed churches and other religious buildings to desecrate and destroy church art and all kinds of decorative fittings over most of the country. The number of actual image-breakers appears to have been relatively small and the exact backgrounds of the movement are debated, but in general, local authorities did not step in to rein in the vandalism. The actions of the iconoclasts drove the nobility into two camps, with Orange and other grandees opposing the movement and others, notably Henry of Brederode, supporting it. Even before he answered the petition by the nobles, Philip had lost control in the troublesome Netherlands. He saw no other option than to send an army

to suppress the rebellion. On 22 August 1567, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba

, marched into Brussels at the head of 10,000 troops.

Alba took harsh measures and rapidly established a special court (Raad van Beroerten or Council of Troubles

Alba took harsh measures and rapidly established a special court (Raad van Beroerten or Council of Troubles

) to judge anyone who opposed the King. No one, not even high nobility who had been pleading for less harsh measures, was safe. Alba considered himself the direct representative of Philip in the Netherlands and frequently bypassed Margaret of Parma and made use of her to lure back some of the fugitive nobles, notably the counts of Egmont and Horne

, causing her to resign office in September 1567. Egmont and Horne were arrested for high treason, condemned, and a year later decapitated

on the Grand Place

in Brussels. Egmont and Horne had been Catholic nobles who were loyal to the King of Spain until their death. The reason for their execution was that Alba considered they had been treasonous to the king in their tolerance to Protestantism. Their death, ordered by a Spanish noble, rather than a local court, provoked outrage throughout the Netherlands. Over one thousand people were executed in the following months. The large number of executions led the court to be nicknamed the "Blood Court" in the Netherlands, and Alba to be called the "Iron Duke". Rather than pacifying the Netherlands, these measures helped to fuel the unrest.

William I of Orange was stadtholder

William I of Orange was stadtholder

of the provinces Holland, Zeeland

and Utrecht

, and Margrave

of Antwerp; and the most influential noble in the States General who had signed the petition. After the arrival of Alba, to avoid arrest, as had happened to Egmont and Horne, he fled to the lands ruled by his wife

's father — the Count

-Elector of Saxony

. All his lands and titles in the Netherlands were forfeited to the Spanish King.

In 1568, William returned to try to drive the highly unpopular Duke of Alba from Brussels

. He did not see this as an act of treason against the King (Philip II

), but as an option for reconciliation with the Spanish King. William's disposing of misguided ministers like Alba would allow the king to take his legal place once more. This view is reflected in today's Dutch national anthem

, the Wilhelmus

, in which the last lines of the first stanza read: den koning van Hispanje heb ik altijd geëerd (I have always honoured the King of Spain). In pamphlets and in his letters to allies in the Netherlands William also called attention to the right of subjects to renounce their oath of obedience if the sovereign would not respect their privileges. An attempt was made to encroach on the Netherlands from four different directions, with armies led by his brothers invading from Germany and with French Huguenots invading from the south. Although the Battle of Rheindalen

near Roermond

occurred already on 23 April 1568 and was won by the Spanish, the Battle of Heiligerlee

, fought on 23 May 1568, is commonly regarded as the beginning of the Eighty Years' War, and it resulted in a victory for the rebel army. But the campaign ended in failure as William ran out of money and his own army disintegrated, while those of his allies were destroyed by the Duke of Alba.

William of Orange stayed at large and, being the only one of the grandees still able to offer resistance, was from then on seen as the leader of the rebellion. When the revolt broke out once more in 1572 he moved his court back to the Netherlands, to Delft

in Holland, as the ancestral lands of Orange in Breda remained occupied by the Spanish. Delft remained William's base of operations until his assassination by Balthasar Gérard

in 1584.

.jpg) Spain was hampered by the fact that it was waging war on multiple fronts simultaneously.

Spain was hampered by the fact that it was waging war on multiple fronts simultaneously.

Its struggle against the Ottoman Empire

in the Mediterranean Sea

put serious limits on the military power it could deploy against the rebels in the Netherlands. France too was opposing Spain at every juncture. Furthermore, England, particularly English privateers, were harassing Spanish shipping and its colonies in the Atlantic.

Already in 1566 William I of Orange had asked for Ottoman support. As Suleiman the Magnificent

claimed that he felt religiously close to the Protestants, ("since they did not worship idols, believed in one God and fought against the Pope and Emperor") he supported the Dutch

together with the French

and the English

, as well as generally support Protestants and Calvinists, as a way to counter Habsburg attempts at supremacy in Europe.

Even so, by 1570 the Spanish had more or less suppressed the rebellion throughout the Netherlands. However, in March 1569, in an effort to finance his troops, Alva had proposed to the States that new taxes be introduced, among them the "Tenth Penny", a 1/10 levy on all sales other than landed property.

This proposal was rejected by the States, and a compromise was subsequently agreed upon. Then, in 1571, Alba decided to press forward with the collection of the Tenth Penny regardless of the States' opposition. This aroused strong protest from both Catholics and Protestants, and support for the rebels grew once more and was fanned by a large group of refugees who had fled the country during Alva's rule.

On March 1, 1572, the English Queen Elizabeth I ousted the Gueux, known as Sea Beggars, from the English harbours in an attempt to appease the Spanish King. The Gueux under their leader Lumey

On March 1, 1572, the English Queen Elizabeth I ousted the Gueux, known as Sea Beggars, from the English harbours in an attempt to appease the Spanish King. The Gueux under their leader Lumey

then unexpectedly captured the almost undefended town of Brill

on April 1. In securing Brill, the rebels had gained a foothold, and more importantly a token victory in the north. This was a sign for Protestants all over the Low Countries to rebel once more.

Most of the important cities in the provinces of Holland and Zealand declared loyalty to the rebels. Notable exceptions were Amsterdam

and Middelburg

, which remained loyal to the Catholic cause until 1578. William of Orange was put at the head of the revolt. He was recognized as Governor-General and Stadholder of Holland, Zeeland, Friesland and Utrecht at a meeting in Dordrecht

in July 1572. It was agreed that power would be shared between Orange and the States. With the influence of the rebels rapidly growing in the northern provinces, the war entered a second and more decisive phase.

However, this also led to an increased discord amongst the Dutch. On one side there was a militant Calvinist minority that wanted to continue fighting the Catholic Philip II and convert all Dutch citizens to Calvinism. On the other end was a mostly Catholic minority that wanted to remain loyal to the governor and his administration in Brussels. In between was the large majority of (Catholic) Dutch that had no particular allegiance, but mostly wanted to restore Dutch privileges and the expulsion of the Spanish mercenary armies. William of Orange was the central figure who had to rally these groups to a common goal. In the end he was forced to move more and more towards the radical Calvinist side, because the Calvinists were most fanatic in fighting the Spanish. He went over to Calvinism himself in 1573.

Being unable to deal with the rebellion, Alba was replaced in 1573 by Luis de Requesens and a new policy of moderation was attempted. Spain, however, had to declare bankruptcy in 1575.

Being unable to deal with the rebellion, Alba was replaced in 1573 by Luis de Requesens and a new policy of moderation was attempted. Spain, however, had to declare bankruptcy in 1575.

Don Luis de Requesens had not managed to broker a policy acceptable to both the Spanish King and the Netherlands when he died in early 1576.

The inability to pay the Spanish mercenary armies endured, leading to numerous mutinies and in November 1576 troops sacked Antwerp

at the cost of some 8,000 lives. This so-called "Spanish Fury" strengthened the resolve of the rebels in the 17 provinces to take fate into their own hands.

The Netherlands negotiated an internal treaty, the Pacification of Ghent

in the same year 1576, in which the provinces agreed to religious tolerance and pledged to fight together against the mutinous Spanish forces.

For the mostly Catholic provinces, the destruction by mutinous foreign troops was the principal reason to join in an open revolt, but formally the provinces still remained loyal to the sovereign Philip II.

However, some religious hostilities continued and Spain, aided by shipments of Bullion from the New World

, was able to send a new army under Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma and Piacenza.

, Hainault

and the so-called Walloon Flanders

located in what is now France and Wallonia) left the alliance agreed upon by the pacification of Ghent and signed the Union of Arras (Atrecht), expressing their loyalty to the Spanish king. This meant an early end to the goal of united independence for the 17 provinces of the Low Countries on the basis of religious tolerance, agreed upon only three years previously.

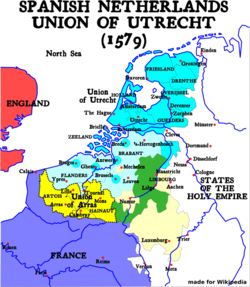

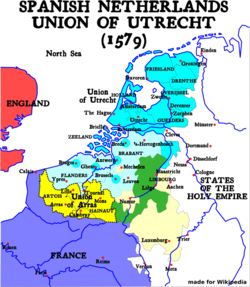

In response to the union of Arras, William united the provinces of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders

and Groningen

in the Union of Utrecht

on January 23, 1579; Brabant

and Flanders

joined a month later, in February 1579. Effectively, the 17 provinces were now divided into a southern group loyal to the Spanish king, and a rebellious northern group.

tried to find a suitable replacement for Philip. The Protestant Queen of England, Elizabeth I

seemed the obvious choice to be protector of the Netherlands. Elizabeth, however, found the idea abhorrent as she had learned from her mistake intervening with the French Huguenots Treaty of Hampton Court

, and had promised herself not to involve herself in any of her fellow Monarchs’ domestic affairs for not only would intervention provoke Philip but it would set an inconvenient precedent; if she could interfere in other Monarchs affairs, they very well might return the favour. Subsequently Elizabeth did break her promise by guaranteeing the Dutch rebels aid with the Treaty of Nonsuch

in 1585, and as a consequence Philip aided the Irish in the Nine Years War. The States-General

responded to Elizabeth's refusal by inviting the younger brother of the French King, the Duke of Anjou

, to be sovereign ruler. Anjou accepted on the condition that the Netherlands officially denounce any loyalty to Philip. In 1581, the Act of Abjuration was issued, in which the Netherlands proclaimed that the King of Spain had not upheld his responsibilities to the Netherlands population and would therefore no longer be accepted as rightful King. Anjou was, however, deeply distrusted by the population and he became increasingly bothered by the limited influence the States were willing to allow him. After some effort to increase his power by military action against the uncooperative cities, Anjou left the Netherlands in 1583.

Elizabeth was now offered the sovereignty of the Netherlands, but she declined. All options for foreign royalty being exhausted, the civilian body States General eventually decided to rule as a republican body instead.

Immediately after the Act of Abjuration, Spain sent a new army to recapture the United Provinces. Over the following years, Parma reconquered the major part of Flanders

Immediately after the Act of Abjuration, Spain sent a new army to recapture the United Provinces. Over the following years, Parma reconquered the major part of Flanders

and Brabant

, as well as large parts of the northeastern provinces. The Roman Catholic

religion was restored in much of this area. In 1585, Antwerp — the largest city in the Low Countries at the time — fell into his hands, which caused over half its population to flee to the north (see also Siege of Antwerp). Between 1560 and 1590, the population of Antwerp plummeted from c. 100,000 inhabitants to c. 42,000.

William of Orange, who had been declared an outlaw

by Philip II in March 1580, was assassinated by a supporter of the King on July 10, 1584. He would be succeeded as leader of the rebellion by his son Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange

.

The Netherlands were split into an independent northern part, while the southern part remained under Spanish control. Due to the almost uninterrupted rule of the Calvinist-dominated separatists, most of the population of the northern provinces became converted to Protestantism over the next decades. The south, under Spanish rule, remained a Catholic stronghold; most of its Protestants fled to the north. Spain retained a large military presence in the south, where it could also be used against France.

With the war going against them, the United Provinces had sought help from the kingdoms of France and England

With the war going against them, the United Provinces had sought help from the kingdoms of France and England

and, in February to May 1585, even offered each monarch sovereignty over the Netherlands, but both had declined.

While England had unofficially been supporting the Dutch for years, Elizabeth had not officially supported the Dutch because she was afraid it might aggravate Spain into a war. However, the year before, the Catholics of France had signed a treaty with Spain in order to destroy the French Protestants. Afraid that France would fall under control of the Habsburgs, Elizabeth now decided to act. In 1585, under the Treaty of Nonsuch

, Elizabeth I

sent the Earl of Leicester to take the rule as lord-regent, with 5,000 to 6,000 troops, including 1,000 cavalry. The Earl of Leicester proved to be a poor commander, and also did not understand the sensitive trade arrangements between the Dutch regents and the Spanish. Moreover, Leicester sided with the radical Calvinists, earning him the distrust of the Catholics and moderates. Leicester also collided with many Dutch patricians when he tried to strengthen his own power at the cost of the Provincial States. Within a year of his arrival, he had lost his public support. Leicester returned to England, after which the States-General, being unable to find any other suitable regent, appointed Maurice of Orange (William's son), at the age of 20, to the position of Captain General

of the Dutch army in 1587. On 7 September 1589 Philip II ordered Parma to move all available forces south to prevent Henry of Navarre from becoming King of France. For Spain the Netherlands had become a side show in comparison to the French Wars of Religion

.

The borders of the present-day Netherlands were largely defined by the campaigns of Maurice of Orange. The Dutch successes owed not only to his tactical skill but also to the financial burden Spain incurred replacing ships lost in the disastrous campaign of the Spanish Armada

in 1588, and the need to refit its navy to recover control of the sea after the subsequent English counter attack

. One of the most notable features of this war are the number of mutinies by the troops in the Spanish army because of arrears of pay. At least 40 mutinies in the period 1570 to 1607 are known. In 1595, when Henry IV of France

declared war against Spain, the Spanish government declared bankruptcy again. However, by regaining control of the sea, Spain was able to greatly increase its supply of gold and silver from the Americas, which allowed it to increase military pressure on England and France.

Under financial and military pressure, in 1598, Philip ceded the Netherlands to his favorite daughter Isabella

Under financial and military pressure, in 1598, Philip ceded the Netherlands to his favorite daughter Isabella

and to her husband, Philip's nephew Archduke Albert of Austria

(they proved to be highly competent governors) following the conclusion of the Treaty of Vervins with France. By that time Maurice was engaged in conquering important cities in the Netherlands. Starting with the important fortification of Bergen op Zoom

(1588), Maurice conquered Breda

(1590), Zutphen, Deventer

, Delfzijl

and Nijmegen (1591), Steenwijk

, Coevorden

(1592) Geertruidenberg

(1593) Groningen (1594) Grol

, Enschede

, Ootmarsum

, Oldenzaal (1597) and Grave (1602). As this campaign was restricted to the border areas of the current Netherlands, the heartland of Holland remained at peace, during which time it moved into its Golden age

.

By now, it had become clear that Spanish control of the Southern Netherlands was strong. However, control over Zeeland meant that the Northern Netherlands could control and close the estuary of the Scheldt

, the entry to the sea for the important port of Antwerp. The port of Amsterdam benefited greatly from the blockade of the port of Antwerp, to the extent that merchants in the North began to question the desirability of reconquering the South. A campaign to control the Southern provinces' coast region was launched against Maurice's advice in 1600. Although portrayed as a liberation of the Southern Netherlands, the campaign was chiefly aimed at eliminating the threat to Dutch trade posed by the Spanish-supported Dunkirkers

. The Spaniards strengthened their positions along the coast, leading to the Battle of Nieuwpoort

.

Although the States-General army won great acclaim for itself and its commander by inflicting a then-surprising defeat of a Spanish army in open battle, Maurice halted the march on Dunkirk and returned to the Northern Provinces. Maurice never forgave the regents, led by van Oldenbarneveld, for being sent on this mission. By now the division of the Netherlands into separate states had become almost inevitable. With the failure to eliminate the Dunkirk threat to trade, the states decided to build up their navy to protect sea trade, which had greatly increased through the creation of the Dutch East Indies Company in 1602. The strengthened Dutch fleets would prove to be a formidable force, hampering Spain's naval ambitions thereafter.

, afterwards called the Twelve Years' Truce

, between the United Provinces and the Spanish controlled southern states, mediated by France and England at The Hague

. It was during this ceasefire the Dutch made great efforts to build their navy, which was later to have a crucial bearing on the course of the war.

During the Truce, two factions emerged in the Dutch camp, along political and religious lines. On one side were the Arminians

, whose prominent supporters included Johan van Oldenbarnevelt and Hugo Grotius

. They tended to be well-to-do merchants who accepted a less strict interpretation of the Bible than did classical Calvinists. They were opposed by the more radical Gomarists, who had openly proclaimed their allegiance to Prince Maurice in 1610. In 1617 the conflict escalated when republicans pushed the "Sharp Resolution", allowing the cities to take measures against the Gomarists. Prince Maurice accused van Oldenbarnevelt of treason, had him arrested, and in 1619, executed. Hugo Grotius fled the country after escaping from imprisonment in Castle Loevestein

.

and the Americas) which could not be resolved. The Spanish made one last effort to reconquer the North, and the Dutch used their navy to enlarge their colonial trade routes to the detriment of Spain. The war was on once more — and crucially, merging with the wider Thirty Years' War

.

In 1622, a Spanish attack on the important fortress town of Bergen op Zoom

was repelled. However, in 1625 Maurice died while the Spanish laid siege to the city of Breda

. Ignoring orders, the Spanish commander Ambrogio Spinola succeeded in conquering the city of Breda. The war was now more focused on trade, much of it in between the Dutch and the Dunkirkers

, but also Dutch attacks on Spanish convoys but above all the seizure of the undermanned Portuguese trading forts and ill defended territories. Maurice's half-brother, Frederick Henry

had succeeded his brother and took command of the army. Frederick Henry conquered the pivotal fortified city of 's-Hertogenbosch in 1629. This town, largest in the northern part of Brabant, had been considered to be impregnable from attack. Its loss was a serious blow to the Spanish.

In 1632, Frederick Henry captured Venlo

, Roermond

, and Maastricht

during his famous "March along the Meuse" in a pincer move to prepare for the conquest of the major cities of Flanders. Attempts in the next years to attack Antwerp and Brussels failed, however. The Dutch were disappointed by the lack of support they received from the Flemish population. This was mainly because of the pillaging of Tienen and the new generation that had been raised in Flanders and Brabant, that had been thoroughly reconverted to Roman Catholicism and now distrusted the Calvinist Dutch even more than it loathed the Spanish occupants.

As more European countries began to build their empires, the war between the countries extended to colonies

As more European countries began to build their empires, the war between the countries extended to colonies

as well. Battles for profitable colonies were fought as far away as Macau

, East Indies

, Ceylon, Formosa (Taiwan

), the Philippines

, Brazil

, and others. The most important of these conflicts would become known as the Dutch-Portuguese War

. The Dutch carved out a trading empire all over the world, using their dominance at sea to great advantage. The Dutch East India Company

was founded to administer all Dutch trade with the East, while the Dutch West India Company

did the same for the West.

In the Western colonies, the Dutch States General mostly restricted itself to supporting privateer

ing by their captains in the Caribbean to drain the Spanish coffers, and to fill their own. The most successful of these raids was the capture of the larger part of the Spanish treasure fleet

by Piet Hein

in 1628; which allowed Frederick Henry to finance the siege of 's Hertogenbosch; and seriously troubled Spanish payments of troops. But attempts were also made to conquer existing colonies or found new ones in Brazil, North America and Africa. Most of these would be only briefly or partially successful. In the East the activities led to the conquest of many profitable trading colonies, a major factor in bringing about the Dutch Golden Age

.

bound for Flanders

, carrying 20,000 troops to assist in a last large scale attempt to defeat the northern "rebels". The armada was decisively defeated by Lieutenant-Admiral Maarten Tromp

in the Battle of the Downs

. This victory had historic consequences far beyond the Eighty Years' War as it marked the end of Spain as the dominant sea power.

An alliance with France changed the balance of power. The Republic could now hope to reconquer the Southern Netherlands. However, this would not mean that they would become a part of the Netherlands, but that they would be divided among the victors, resulting in a powerful French state bordering on the Republic. Furthermore it would mean that the port of Antwerp would most likely no longer be blockaded and might become serious competition for Amsterdam. With the Thirty Years' War

decided, there was also no longer any need to fight on in order to support fellow Protestant nations. As a result, the decision was made to end the war.

On January 30, 1648, the war ended with the Treaty of Münster

On January 30, 1648, the war ended with the Treaty of Münster

between Spain and the Netherlands. In Münster on May 15, 1648, the parties exchanged ratified copies of the treaty. This treaty was part of the European scale Peace of Westphalia

that also ended the Thirty Years' War

. In the treaty, the power balance in Western Europe was readjusted to the actual geopolitical reality. This meant that de jure the Dutch Republic was recognised as an independent state and retained control over the territories that were conquered in the later stages of the war. The new republic consisted of seven provinces: Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, Overijssel

, Friesland

, and Groningen. Each province was governed by its local Provincial States and by a stadtholder. In theory, each stadtholder was elected and subordinate to the States-General. However, the princes of Orange-Nassau, beginning with William I of Orange, became de facto hereditary stadtholders in Holland and Zeeland. In practice they usually became stadtholder of the other provinces as well. A constant power struggle, which already had shown its precursor during the Twelve years' Truce, emerged between the Orangists

, who supported the stadtholders, and the Regent's supporters.

The border states, parts of Flanders, Brabant and Limburg that were conquered by the Dutch in the final stages of the war, were to be federally governed by the States-General. The so called Generality Lands

(Generaliteitslanden), which consisted of Staats-Brabant (present North Brabant

), Staats-Vlaanderen (present Zeeuws-Vlaanderen

) and Staats-Limburg (around Maastricht

).

The peace would not be long-lived as the newly emerged world powers, the Republic of the Netherlands and the Commonwealth of England

, would start their first war in 1652, only four years after the peace was signed.

, which demanded much of Spain's financial and human resources.

As the revolt and its suppression centered largely around issues of religious freedom and taxation, the conflict necessarily involved not only soldiers, but also civilians at all levels of society. This may be one reason for the resolve and subsequent successes of the Dutch rebels in defending cities. Another factor was the fact that the unpopularity of the Spanish army, which existed even before the start of the revolt, was exacerbated when in the early stage of the war a few cities were purposely sacked by the Spanish troops after having surrendered; this was done in order to intimidate the remaining rebel cities into surrender. Given the involvement of all sectors of Dutch society in the conflict, a more-or-less organized, irregular army emerged alongside the regular forces. Among these were the geuzen

(from the French word "gueux" meaning "beggars"), who waged a guerrilla

war against Spanish interests. Especially at sea, the 'watergeuzen' were effective agents of the Dutch cause.

Another aspect of warfare in the Netherlands was its relatively static character. There were very few pitched battles where armies met in the field. Most military operations were sieges, as was typical of the era, resulting in protracted and expensive use of the military forces available. The Dutch had fortified most of their cities and even many smaller towns in accordance with the most modern views of the time

, and these cities had to be subdued one by one. Sometimes sieges were broken off when the enemy threatened to attack the besieging army, or, on the Spanish side, conquered cities were given up immediately, or occasionally sold back to the Dutch, when the conquering army turned mutinous.

In the later stages, Maurice raised a professional standing army that was even paid when no hostilities were taking place, a radical innovation in that time and part of the Military Revolution

. This ensured him of loyal soldiers, who were trained in cooperating among each other and were intimately familiar with the doctrines of their commanders and were capable of carrying out complicated manoeuvres.

In the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549

In the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549

, Charles V established the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands as an entity separate from France, Burgundy, or the Holy Roman Empire. The Netherlands at this point were among the wealthiest regions in Europe, and an important center of trade, finance, and art. The Eighty Years' War introduced a sharp breach in the region, with the Dutch Republic (the present-day Netherlands

) growing into a world power (see Dutch Golden Age

), and the Southern Netherlands (more or less present-day Belgium

) losing much of its economic and cultural significance for centuries to come. The naval blockade during much of the Eighty Years' War of Antwerp, once the largest commercial centre of Europe, greatly contributed to the rise of Amsterdam as the new centre of European and world trade.

Politically, a unique situation had emerged in the Netherlands where a republican body (the States General) ruled, but where a (increasingly hereditary) noble function of Stadtholder was occupied by the house of Orange-Nassau

. This division of power prevented large scale fighting between nobility and civilians as happened in the English Civil War

. The frictions between the civil and noble fractions, that already started in the twelve years' truce, were numerous and would finally lead to an outburst with the French supported Batavian Republic

, where Dutch bourgeoisie

hoped to get rid of the increasing self-esteem in the nobility once and for all. However, in a dramatic resurgence of nobility after the Napoleonic era

the republic would be abandoned in favor of the foundation of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands

. Thus, one of the oldest republics of Europe was turned into a monarchy, which it still is today.

The conquest of various American

The conquest of various American

territories made Spain the leading European power of the 16th century. This brought them into continuous conflict with France and the emerging power that was England. In addition, the deeply religious monarchs Charles V and Philip II saw a role for themselves as protectors of the Catholic faith against Islam

in the Mediterranean and against Protestantism in northern Europe. This meant the Spanish Empire was almost continuously at war. Of all these conflicts, the Eighty Years' War was the most prolonged and had a major effect on the Spanish finances and the morale of the Spanish people, who saw taxes increase and soldiers not returning, with little successes to balance the scales. The Spanish government had to declare several bankruptcies

. The Spanish population increasingly questioned the necessity of the war in the Netherlands and even the necessity of the Empire in general. The loss of Portugal

in 1640

and the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, ending the war were the first signs that the role of the Spanish Empire

in Europe was declining.

, and eventually led to the Dutch Republic

. The acceptance of a non-monarchic country by the other European powers in 1648 spread across Europe, fueling resistance against the divine power of Kings.

The first open violence that would lead to the war was the 1566 iconoclasm, and sometimes the first Spanish repressions of the riots (i.e. battle of Oosterweel

Battle of Oosterweel

The Battle of Oosterweel took place on March 13, 1567, and is traditionally seen as the beginning of the Eighty Years' War. The battle was fought near the village of Oosterweel, north of Antwerp. A Spanish professional army under General Beauvoir defeated an army of radical Calvinists rebels under...

, 1567) are considered the starting point. Most accounts cite the 1568 invasions of armies of mercenaries paid by William of Orange as the official start of the war; this article adopts that point of view. Alternatively, the start of the war is sometimes set at the capture of Brielle

Capture of Brielle

The Capture of Brielle by the Sea Beggars, or Watergeuzen, on 1 April 1572 marked a turning point in the uprising of the Low Countries against Spain in the Eighty Years' War. Militarily the success was minor, as Brielle was not being defended at the time...

by the Gueux in 1572. was the partially successful revolt of the Protestant Seventeen Provinces

Seventeen Provinces

The Seventeen Provinces were a personal union of states in the Low Countries in the 15th century and 16th century, roughly covering the current Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, a good part of the North of France , and a small part of Western Germany.The Seventeen Provinces were originally held by...

of the defunct Duchy of Burgundy

Duchy of Burgundy

The Duchy of Burgundy , was heir to an ancient and prestigious reputation and a large division of the lands of the Second Kingdom of Burgundy and in its own right was one of the geographically larger ducal territories in the emergence of Early Modern Europe from Medieval Europe.Even in that...

in the Low Countries

Low Countries

The Low Countries are the historical lands around the low-lying delta of the Rhine, Scheldt, and Meuse rivers, including the modern countries of Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and parts of northern France and western Germany....

against the ardent militant religious policies of Roman Catholicism pressed by both Charles V and his son Philip II of Spanish Empire

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

. The religious 'clash of cultures

Culture Clash

Culture Clash may refer to:* Culture Clash , American performance troupe* Culture Clash , British band which plays Harare Jit music...

' built up gradually but inexorably into outbursts of violence against the perceived repression of the Spanish Crown. These tensions marked the beginning of the Thirty Years' War

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was fought primarily in what is now Germany, and at various points involved most countries in Europe. It was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history....

and led to the formation of the independent Dutch Republic

Dutch Republic

The Dutch Republic — officially known as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands , the Republic of the United Netherlands, or the Republic of the Seven United Provinces — was a republic in Europe existing from 1581 to 1795, preceding the Batavian Republic and ultimately...

. The first leader was William of Orange

William the Silent

William I, Prince of Orange , also widely known as William the Silent , or simply William of Orange , was the main leader of the Dutch revolt against the Spanish that set off the Eighty Years' War and resulted in the formal independence of the United Provinces in 1648. He was born in the House of...

, followed by several of his descendants and relations. This revolt was one of the first successful secession

Secession

Secession is the act of withdrawing from an organization, union, or especially a political entity. Threats of secession also can be a strategy for achieving more limited goals.-Secession theory:...

s in Europe, and led to one of the first European republics of the modern era, the United Provinces.

Spain was initially successful in suppressing the rebellion. In 1572, however, the rebels captured Brielle

Capture of Brielle

The Capture of Brielle by the Sea Beggars, or Watergeuzen, on 1 April 1572 marked a turning point in the uprising of the Low Countries against Spain in the Eighty Years' War. Militarily the success was minor, as Brielle was not being defended at the time...

and the rebellion resurged. The northern provinces became independent, first de facto

De facto

De facto is a Latin expression that means "concerning fact." In law, it often means "in practice but not necessarily ordained by law" or "in practice or actuality, but not officially established." It is commonly used in contrast to de jure when referring to matters of law, governance, or...

, and in 1648 de jure

De jure

De jure is an expression that means "concerning law", as contrasted with de facto, which means "concerning fact".De jure = 'Legally', De facto = 'In fact'....

. During the revolt, the United Provinces of the Netherlands, better known as the Dutch Republic

Dutch Republic

The Dutch Republic — officially known as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands , the Republic of the United Netherlands, or the Republic of the Seven United Provinces — was a republic in Europe existing from 1581 to 1795, preceding the Batavian Republic and ultimately...

, rapidly grew to become a world power through its merchant shipping and experienced a period of economic, scientific, and cultural growth. The Southern Netherlands

Southern Netherlands

Southern Netherlands were a part of the Low Countries controlled by Spain , Austria and annexed by France...

(situated in modern-day Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

, Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Luxembourg , officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg , is a landlocked country in western Europe, bordered by Belgium, France, and Germany. It has two principal regions: the Oesling in the North as part of the Ardennes massif, and the Gutland in the south...

, northern France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and southern Netherlands; see Spanish Netherlands and French Netherlands) remained under Spanish rule. The continuous heavy-handed rule by the Spanish in the south caused many of its financial, intellectual, and cultural elite to flee north, contributing to the success of the Dutch Republic. The Dutch imposed a rigid blockade on the southern provinces which prevented Baltic grain relieving famine in the southern towns, especially in the years 1587-9. Additionally, by the end of the war in 1648 large areas of the Southern Netherlands had been lost to France which had, under the guidance of Cardinal Richelieu and Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII of France

Louis XIII was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and of Navarre from 1610 to 1643.Louis was only eight years old when he succeeded his father. His mother, Marie de Medici, acted as regent during Louis' minority...

, allied itself with the Dutch Republic in the 1630s against Spain.

The first phase of the conflict can be considered to be the Dutch War of Independence. The focus of the latter phase was to gain official recognition of the already de facto independence of the United Provinces. This phase coincided with the rise of the Dutch Republic as a major power and the founding of the Dutch Empire

Dutch Empire

The Dutch Empire consisted of the overseas territories controlled by the Dutch Republic and later, the modern Netherlands from the 17th to the 20th century. The Dutch followed Portugal and Spain in establishing an overseas colonial empire, but based on military conquest of already-existing...

.

Background

In a series of marriages and conquests, a succession of Dukes of BurgundyDuke of Burgundy

Duke of Burgundy was a title borne by the rulers of the Duchy of Burgundy, a small portion of traditional lands of Burgundians west of river Saône which in 843 was allotted to Charles the Bald's kingdom of West Franks...

expanded their original territory by adding to it a series of fiefdoms, including the Seventeen Provinces

Seventeen Provinces

The Seventeen Provinces were a personal union of states in the Low Countries in the 15th century and 16th century, roughly covering the current Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, a good part of the North of France , and a small part of Western Germany.The Seventeen Provinces were originally held by...

. Although Burgundy

Duchy of Burgundy

The Duchy of Burgundy , was heir to an ancient and prestigious reputation and a large division of the lands of the Second Kingdom of Burgundy and in its own right was one of the geographically larger ducal territories in the emergence of Early Modern Europe from Medieval Europe.Even in that...

itself had been lost to France in 1477, the Burgundian Netherlands were still intact when Charles V

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V was ruler of the Holy Roman Empire from 1519 and, as Charles I, of the Spanish Empire from 1516 until his voluntary retirement and abdication in favor of his younger brother Ferdinand I and his son Philip II in 1556.As...

was born in Ghent

Ghent

Ghent is a city and a municipality located in the Flemish region of Belgium. It is the capital and biggest city of the East Flanders province. The city started as a settlement at the confluence of the Rivers Scheldt and Lys and in the Middle Ages became one of the largest and richest cities of...

in 1500. He was raised in the Netherlands and spoke fluent Dutch, French, Spanish, and some German. In 1506 he became lord of the Burgundian states, among which were the Netherlands. Subsequently, in 1516, he inherited several titles, including the combined kingdoms of Aragon

Aragon

Aragon is a modern autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. Located in northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces : Huesca, Zaragoza, and Teruel. Its capital is Zaragoza...

, and Castile and León

Castile and León

Castile and León is an autonomous community in north-western Spain. It was so constituted in 1983 and it comprises the historical regions of León and Old Castile...

which had become a worldwide empire with the Spanish colonization of the Americas

Spanish colonization of the Americas

Colonial expansion under the Spanish Empire was initiated by the Spanish conquistadores and developed by the Monarchy of Spain through its administrators and missionaries. The motivations for colonial expansion were trade and the spread of the Christian faith through indigenous conversions...

. In 1519 he became ruler of the Habsburg empire, and he gained the title Holy Roman Emperor

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor is a term used by historians to denote a medieval ruler who, as German King, had also received the title of "Emperor of the Romans" from the Pope...

in 1530. Although Friesland

Friesland

Friesland is a province in the north of the Netherlands and part of the ancient region of Frisia.Until the end of 1996, the province bore Friesland as its official name. In 1997 this Dutch name lost its official status to the Frisian Fryslân...

and Guelders

Guelders

Guelders or Gueldres is the name of a historical county, later duchy of the Holy Roman Empire, located in the Low Countries.-Geography:...

offered prolonged resistance (under Grutte Pier

Pier Gerlofs Donia

Pier Gerlofs Donia was a Frisian warrior, pirate, and rebel. He is best known by his West Frisian nickname "Grutte Pier" , or by the Dutch translations "Grote Pier" and "Lange Pier", or, in Latin, "Pierius Magnus", which referred to his legendary size and strength. His life is mostly shrouded in...

and Charles of Egmond, respectively), virtually all of the Netherlands had been incorporated into the Habsburg domains by the early 1540s.

Taxation

FlandersFlanders

Flanders is the community of the Flemings but also one of the institutions in Belgium, and a geographical region located in parts of present-day Belgium, France and the Netherlands. "Flanders" can also refer to the northern part of Belgium that contains Brussels, Bruges, Ghent and Antwerp...

had long been a very wealthy region, and had been coveted by the French kings for a long time. The other Netherlands had also grown into wealthy and entrepreneur

Entrepreneur

An entrepreneur is an owner or manager of a business enterprise who makes money through risk and initiative.The term was originally a loanword from French and was first defined by the Irish-French economist Richard Cantillon. Entrepreneur in English is a term applied to a person who is willing to...

ial regions within the empire. Charles V

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V was ruler of the Holy Roman Empire from 1519 and, as Charles I, of the Spanish Empire from 1516 until his voluntary retirement and abdication in favor of his younger brother Ferdinand I and his son Philip II in 1556.As...

's empire became a worldwide empire with large American and European territories. The latter were, however, distributed throughout Europe. Control and defence of these were hampered by the disparateness of the territories and huge length of the empire's borders. This large realm was almost continuously at war with its neighbours in its European heartlands, most notably against France in the Italian Wars

Italian Wars

The Italian Wars, often referred to as the Great Italian Wars or the Great Wars of Italy and sometimes as the Habsburg–Valois Wars, were a series of conflicts from 1494 to 1559 that involved, at various times, most of the city-states of Italy, the Papal States, most of the major states of Western...

and against the Turks

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

in the Mediterranean Sea

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

. Further wars were fought against Protestant princes in Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

. The Netherlands paid heavy taxes to fund these wars, but perceived them as unnecessary and sometimes downright harmful, because they were directed against their most important trading partners.

Protestantism

During the 16th century, Protestantism rapidly gained ground in northern Europe. Dutch Protestants, after initial repression, were tolerated by local authorities. By the 1560s, the Protestant community had become a significant influence in the Netherlands, although it clearly formed a minority then. In a society dependent on trade, freedom and tolerance were considered essential. Nevertheless, Charles V, and later Philip IIPhilip II of Spain

Philip II was King of Spain, Portugal, Naples, Sicily, and, while married to Mary I, King of England and Ireland. He was lord of the Seventeen Provinces from 1556 until 1581, holding various titles for the individual territories such as duke or count....

, felt it was their duty to fight Protestantism, which was considered a heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

by the Catholic Church. The harsh measures led to increasing grievances in the Netherlands, where the local governments had embarked on a course of peaceful coexistence. In the second half of the century, the situation escalated. Philip sent troops to crush the rebellion and make the Netherlands once more a Catholic region.

The Dutch Protestants compared their humble lifestyle favorably with the supposedly luxurious habits of the ecclesiastical nobility.

Centralisation

Aristocracy (class)

The aristocracy are people considered to be in the highest social class in a society which has or once had a political system of Aristocracy. Aristocrats possess hereditary titles granted by a monarch, which once granted them feudal or legal privileges, or deriving, as in Ancient Greece and India,...

s, but instead stemmed from non-noble families that had risen in status over the last centuries. By the 15th century, Brussels

Brussels

Brussels , officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region , is the capital of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union...

had thus become the de facto capital of the Seventeen Provinces.

Dating back to the Middle Ages the districts of the Netherlands, represented by its nobility and the wealthy city-dwelling merchants still had a large measure of autonomy in appointing its administrators. Charles V and Philip II set out to improve the management of the empire by increasing the authority of the central government in matters like law and taxes, a policy which caused suspicion both among the nobility and the merchant class. An example of this is the takeover of power in the city of Utrecht

Utrecht (city)

Utrecht city and municipality is the capital and most populous city of the Dutch province of Utrecht. It is located in the eastern corner of the Randstad conurbation, and is the fourth largest city of the Netherlands with a population of 312,634 on 1 Jan 2011.Utrecht's ancient city centre features...

in 1528 when Charles V supplanted the council of guild

Guild

A guild is an association of craftsmen in a particular trade. The earliest types of guild were formed as confraternities of workers. They were organized in a manner something between a trade union, a cartel, and a secret society...

masters governing the city by his own stadtholder

Stadtholder

A Stadtholder A Stadtholder A Stadtholder (Dutch: stadhouder [], "steward" or "lieutenant", literally place holder, holding someones place, possibly a calque of German Statthalter, French lieutenant, or Middle Latin locum tenens...

, who took over worldly powers in the whole province of Utrecht from the archbishop of Utrecht

Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Utrecht

The Archdiocese of Utrecht is an archdiocese of the Catholic Church in the Netherlands. The archdiocese is the metropolitan for 6 suffragans, the dioceses of Breda, Groningen-Leeuwarden, Haarlem-Amsterdam, Roermond, Rotterdam, and 's-Hertogenbosch....

. Charles ordered the construction of the heavily fortified castle of Vredenburg

Vredenburg (castle)

Vredenburg or Vredeborch was a 16th-century castle built by Habsburg emperor Charles V in the city of Utrecht in the Netherlands. Some remains of the castle, which stood for only 50 years, are still visible on what is now Vredenburg square in Utrecht....

, for defence against the Duchy of Gelre and to control the citizens of Utrecht.

Under the governorship of Mary of Hungary (1531–1555), traditional power had for a large part been taken away both from the stadtholders of the provinces and from the high noblemen, who had been replaced by professional jurists in the Council of State

Dutch Council of State

In the Netherlands, the Council of State is a constitutionally established advisory body to the government which consists of members of the royal family and Crown-appointed members generally having political, commercial, diplomatic, or military experience...

.

Initial stages (1555–1572)

Prelude to the rebellion (1555–1568)

In 1556 Charles passed on his throne to his son Philip II of SpainPhilip II of Spain

Philip II was King of Spain, Portugal, Naples, Sicily, and, while married to Mary I, King of England and Ireland. He was lord of the Seventeen Provinces from 1556 until 1581, holding various titles for the individual territories such as duke or count....

. Charles, despite his harsh actions, had been seen as a ruler empathetic to the needs of the Netherlands. Philip, on the other hand, was raised in Spain and spoke neither Dutch nor French. During Philip's reign, tensions flared in the Netherlands over heavy taxation, suppression of Protestantism, and centralisation efforts. The growing conflict would reach a boiling point and would lead ultimately to the war of independence.

Nobility in opposition

In an effort to build a stable and trustworthy government of the Netherlands, Philip appointed his half-sister Margaret of ParmaMargaret of Parma

Margaret, Duchess of Parma , Governor of the Netherlands from 1559 to 1567 and from 1578 to 1582, was the illegitimate daughter of Charles V and Johanna Maria van der Gheynst...

as governor of the Netherlands. He continued the policy of his father of appointing members of the high nobility of the Netherlands to the Raad van State (Council of State), the governing body of the seventeen Netherlands, that advised her. He made his confidant Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle

Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle

Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle , Comte de La Baume Saint Amour, was a Burgundian statesman, made a cardinal, who followed his father as a leading minister of the Spanish Habsburgs, and was one of the most influential European politicians during the time which immediately followed the appearance of...

head of that Council. However, already in 1558 the States of the provinces and the States-General of the Netherlands

States-General of the Netherlands

The States-General of the Netherlands is the bicameral legislature of the Netherlands, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The parliament meets in at the Binnenhof in The Hague. The archaic Dutch word "staten" originally related to the feudal classes in which medieval...

started to contradict Philip's wishes, by objecting to his tax proposals and by demanding, with eventual success, the withdrawal of Spanish troops which had been left by Philip to guard the Southern Netherlands' borders with France, but which they saw as a threat to their own independence (1559–1561). Subsequent reforms met with much opposition, which was mainly directed at Granvelle. Petitions to King Philip by the high nobility went unanswered. Some of the most influential nobles, including Lamoral, Count of Egmont

Lamoral, Count of Egmont

Lamoral, Count of Egmont, Prince of Gavere was a general and statesman in the Habsburg Netherlands just before the start of the Eighty Years' War, whose execution helped spark the national uprising that eventually led to the independence of the Netherlands.The Count of Egmont headed one of the...

, Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn

Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn

Philip de Montmorency was also known as Count of Horn or Hoorne or Hoorn.-Biography:De Montmorency was born, between 1518 and 1526, possibly at the Ooidonk Castle, as the son of Jozef van Montmorency, Count of Nevele and Anna van Egmont...

, and William the Silent

William the Silent

William I, Prince of Orange , also widely known as William the Silent , or simply William of Orange , was the main leader of the Dutch revolt against the Spanish that set off the Eighty Years' War and resulted in the formal independence of the United Provinces in 1648. He was born in the House of...

, withdrew from the Council of State until Philip recalled Granvelle. In late 1564, the nobles had noticed the growing power of the reformation and urged Philip to come up with realistic measures to prevent violence. Philip answered that sterner measures could be the only answer. Subsequently Egmont, Horne and Orange withdrew once more from the Council and Bergen and Meghem resigned their Stadholdership. During the same period, the religious protests were increasing in spite of increased oppression. In 1566, a league of about 400 members of the nobility presented a petition to the governor Margaret of Parma

Margaret of Parma

Margaret, Duchess of Parma , Governor of the Netherlands from 1559 to 1567 and from 1578 to 1582, was the illegitimate daughter of Charles V and Johanna Maria van der Gheynst...

, to suspend persecution until the rest had returned. One of Margaret's courtiers, Count Berlaymont

Charles de Berlaymont

Charles de Berlaymont was a noble who sided with the Spanish during the Eighty years war, and was a member of the Council of Troubles. He was the son of Michiel de Berlaymont and Maria de Berault. He was lord of Floyon and Haultpenne, and baron of Hierges...

, called the presentation of this petition an act of 'beggars' (French gueux), a name taken up as an honour by the petitioners (Geuzen

Geuzen

Geuzen was a name assumed by the confederacy of Calvinist Dutch nobles and other malcontents, who from 1566 opposed Spanish rule in the Netherlands. The most successful group of them operated at sea, and so were called Watergeuzen...

). The petition was sent on to Philip for a final verdict.

1566 — Iconoclasm and repression

Northern Seven Years' War

The Northern Seven Years' War was the war between Kingdom of Sweden and a coalition of Denmark–Norway, Lübeck and the Polish–Lithuanian union, fought between 1563 and 1570...

. Early August 1566, a monastery church at Steenvoorde

Steenvoorde

Steenvoorde is a commune in the Nord department in northern France. The Beeldenstorm iconoclasm started in Steenvoorde. Steenvoorde is a city of the giants -Heraldry:-References:* -External links:*...

in Flanders (now in Northern France) was sacked by a mob led by the preacher Sebastian Matte. This incident was followed by similar riots elsewhere in Flanders, and before long the Netherlands had become the scene of the Beeldenstorm

Beeldenstorm

Beeldenstorm in Dutch, roughly translatable to "statue storm", or Bildersturm in German , also the Iconoclastic Fury, is a term used for outbreaks of destruction of religious images that occurred in Europe in the 16th century...

, a riotous iconoclastic

Iconoclasm

Iconoclasm is the deliberate destruction of religious icons and other symbols or monuments, usually with religious or political motives. It is a frequent component of major political or religious changes...

movement by Calvinists, who stormed churches and other religious buildings to desecrate and destroy church art and all kinds of decorative fittings over most of the country. The number of actual image-breakers appears to have been relatively small and the exact backgrounds of the movement are debated, but in general, local authorities did not step in to rein in the vandalism. The actions of the iconoclasts drove the nobility into two camps, with Orange and other grandees opposing the movement and others, notably Henry of Brederode, supporting it. Even before he answered the petition by the nobles, Philip had lost control in the troublesome Netherlands. He saw no other option than to send an army

Army of Flanders

The Army of Flanders was a Spanish Habsburg army based in the Netherlands during the 16th to 18th centuries. It was notable for being the longest standing army of the period, being in continuous service from 1567 until its disestablishment in 1706...

to suppress the rebellion. On 22 August 1567, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba

Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba

Don Fernando Álvarez de Toledo y Pimentel, 3rd Duke of Alba was a Spanish general and governor of the Spanish Netherlands , nicknamed "the Iron Duke" in the Low Countries because of his harsh and cruel rule there and his role in the execution of his political opponents and the massacre of several...

, marched into Brussels at the head of 10,000 troops.

Council of Troubles

The Council of Troubles was the special tribunal instituted on September 9, 1567 by Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, governor-general of the Habsburg Netherlands on the orders of Philip II of Spain to punish the ringleaders of the recent political and religious "troubles" in the...

) to judge anyone who opposed the King. No one, not even high nobility who had been pleading for less harsh measures, was safe. Alba considered himself the direct representative of Philip in the Netherlands and frequently bypassed Margaret of Parma and made use of her to lure back some of the fugitive nobles, notably the counts of Egmont and Horne

Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn

Philip de Montmorency was also known as Count of Horn or Hoorne or Hoorn.-Biography:De Montmorency was born, between 1518 and 1526, possibly at the Ooidonk Castle, as the son of Jozef van Montmorency, Count of Nevele and Anna van Egmont...

, causing her to resign office in September 1567. Egmont and Horne were arrested for high treason, condemned, and a year later decapitated

Decapitation

Decapitation is the separation of the head from the body. Beheading typically refers to the act of intentional decapitation, e.g., as a means of murder or execution; it may be accomplished, for example, with an axe, sword, knife, wire, or by other more sophisticated means such as a guillotine...

on the Grand Place

Grand Place

The Grand Place or Grote Markt is the central square of Brussels. It is surrounded by guildhalls, the city's Town Hall, and the Breadhouse . The square is the most important tourist destination and most memorable landmark in Brussels, along with the Atomium and Manneken Pis...

in Brussels. Egmont and Horne had been Catholic nobles who were loyal to the King of Spain until their death. The reason for their execution was that Alba considered they had been treasonous to the king in their tolerance to Protestantism. Their death, ordered by a Spanish noble, rather than a local court, provoked outrage throughout the Netherlands. Over one thousand people were executed in the following months. The large number of executions led the court to be nicknamed the "Blood Court" in the Netherlands, and Alba to be called the "Iron Duke". Rather than pacifying the Netherlands, these measures helped to fuel the unrest.

William of Orange

Stadtholder

A Stadtholder A Stadtholder A Stadtholder (Dutch: stadhouder [], "steward" or "lieutenant", literally place holder, holding someones place, possibly a calque of German Statthalter, French lieutenant, or Middle Latin locum tenens...

of the provinces Holland, Zeeland

Zeeland

Zeeland , also called Zealand in English, is the westernmost province of the Netherlands. The province, located in the south-west of the country, consists of a number of islands and a strip bordering Belgium. Its capital is Middelburg. With a population of about 380,000, its area is about...

and Utrecht

Utrecht (province)

Utrecht is the smallest province of the Netherlands in terms of area, and is located in the centre of the country. It is bordered by the Eemmeer in the north, Gelderland in the east, the river Rhine in the south, South Holland in the west, and North Holland in the northwest...

, and Margrave

Margrave

A margrave or margravine was a medieval hereditary nobleman with military responsibilities in a border province of a kingdom. Border provinces usually had more exposure to military incursions from the outside, compared to interior provinces, and thus a margrave usually had larger and more active...

of Antwerp; and the most influential noble in the States General who had signed the petition. After the arrival of Alba, to avoid arrest, as had happened to Egmont and Horne, he fled to the lands ruled by his wife

Anna of Saxony

Anna of Saxony was the only child and heiress of Maurice, Elector of Saxony, and Agnes, eldest daughter of Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse. She was the second wife of William the Silent.Anna was born and died in Dresden...

's father — the Count

Count

A count or countess is an aristocratic nobleman in European countries. The word count came into English from the French comte, itself from Latin comes—in its accusative comitem—meaning "companion", and later "companion of the emperor, delegate of the emperor". The adjective form of the word is...

-Elector of Saxony

Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony , sometimes referred to as Upper Saxony, was a State of the Holy Roman Empire. It was established when Emperor Charles IV raised the Ascanian duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg to the status of an Electorate by the Golden Bull of 1356...

. All his lands and titles in the Netherlands were forfeited to the Spanish King.

In 1568, William returned to try to drive the highly unpopular Duke of Alba from Brussels

Brussels

Brussels , officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region , is the capital of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union...

. He did not see this as an act of treason against the King (Philip II

Philip II of Spain

Philip II was King of Spain, Portugal, Naples, Sicily, and, while married to Mary I, King of England and Ireland. He was lord of the Seventeen Provinces from 1556 until 1581, holding various titles for the individual territories such as duke or count....

), but as an option for reconciliation with the Spanish King. William's disposing of misguided ministers like Alba would allow the king to take his legal place once more. This view is reflected in today's Dutch national anthem

Anthem

The term anthem means either a specific form of Anglican church music , or more generally, a song of celebration, usually acting as a symbol for a distinct group of people, as in the term "national anthem" or "sports anthem".-Etymology:The word is derived from the Greek via Old English , a word...

, the Wilhelmus

Wilhelmus

Wilhelmus van Nassouwe, usually known just as the Wilhelmus , , is the national anthem of the Netherlands and is the oldest national anthem in the world though the words of the Japanese national anthem date back to the ninth century...

, in which the last lines of the first stanza read: den koning van Hispanje heb ik altijd geëerd (I have always honoured the King of Spain). In pamphlets and in his letters to allies in the Netherlands William also called attention to the right of subjects to renounce their oath of obedience if the sovereign would not respect their privileges. An attempt was made to encroach on the Netherlands from four different directions, with armies led by his brothers invading from Germany and with French Huguenots invading from the south. Although the Battle of Rheindalen

Battle of Rheindalen