German-Japanese relations

Encyclopedia

From the founding of the Tokugawa Shogunate

in 1603, Japan isolated itself from the outside world until the Meiji Restoration

of 1867, when it began to accept contact with Western nations. German–Japanese relations were established in 1860 with the first ambassadorial visit to Japan

from Prussia

(which predated the formation of the German Empire

in 1871). After a time of intense intellectual and cultural exchange

in the late 19th century, the two empires' conflicting aspirations in China led to a cooling of relations. Japan allied itself with Britain in World War I

, declaring war on Germany in 1914 and seizing key German possessions in Asia.

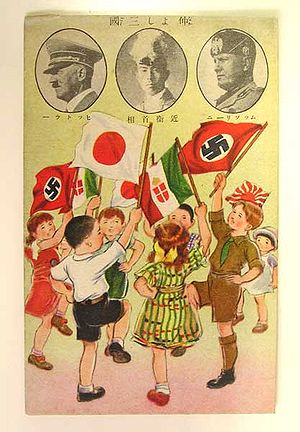

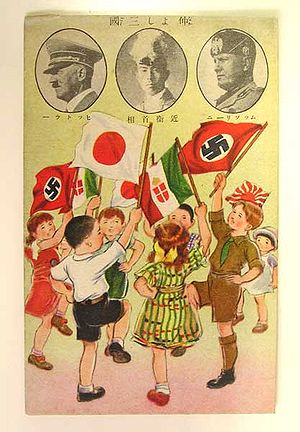

In the 1930s, both countries rejected democracy in all but name, and adopted militaristic attitudes toward their respective regions. This led to a rapprochement and, eventually, a political and military alliance that included Italy: the "Axis

". During the Second World War, however, the Axis was limited by the great distances between the Axis powers; for the most part, Japan and Germany fought separate wars, and eventually surrendered separately.

After the Second World War, the economies of both nations experienced rapid recoveries; bilateral relations, now focused on economic issues, were soon re-established. Today, Japan and Germany are, respectively, the third and fourth largest economies in the world (after the U.S. and China) and benefit greatly from many kinds of political, cultural, scientific and economic cooperation.

Relations between Japan and Germany date from the Tokugawa Shogunate

Relations between Japan and Germany date from the Tokugawa Shogunate

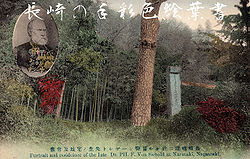

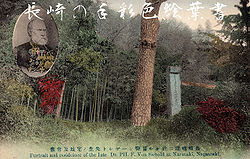

(1603–1868), when Germans in Dutch service arrived in Japan to work for the Dutch East India Company

(VOC). The first well-documented cases are those of the physicians Engelbert Kaempfer

(1651–1716) and Philipp Franz von Siebold

(1796–1866) in the 1690s and the 1820s respectively. Siebold was allowed to travel throughout Japan, in spite of the restrictive seclusion policy which the Tokugawa shogunate

had implemented in the 1630s. Siebold became the author of Nippon, Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan (Nippon, Archive For The Description of Japan), one of the most valuable sources of information on Japan well into the 20th century; since 1979 his achievements have been recognised with an annual German award in his honour, the Philipp Franz von Siebold-Preis, granted to Japanese scientists.

In 1854 the United States

pressured Japan into the Convention of Kanagawa

, which ended Japan's isolation, but was considered an "unequal treaty" by the Japanese public, since the US did not reciprocate most of Japan's concessions with similar privileges. In many cases Japan was effectively forced into a system of extraterritoriality that provided for the subjugation of foreign residents to the laws of their own consular courts instead of the Japanese law system, open up ports for trade, and later even allow Christian missionaries to enter the country. Shortly after the end of Japan's seclusion, in a period called "Bakumatsu" (幕末, "End of the Shogunate"), the first German traders arrived in Japan. In 1860 Count Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg

led the Eulenburg Expedition

to Japan as ambassador from Prussia, a leading regional state in the German Confederation

at that time. After four months of negotiations, another "unequal treaty", officially dedicated to amity and commerce, was signed in January 1861 between Prussia and Japan.

Despite being considered one of the numerous unjust negotiations pressed on Japan during that time, the Eulenburg Expedition, and both the short- and long-term consequences of the treaty of amity and commerce, are today honoured as the beginning of official Japanese-German relations. To commemorate its 150th anniversary, events were held in both Germany and Japan from autumn 2010 through autumn 2011 hoping "to 'raise the treasures of [their] common past' in order to build a bridge to the future."

became diplomatic representative in Japan – first representing Prussia, and after 1866 representing the North German Confederation

, and by 1871 representing the newly established German Empire

.

In 1868 the Tokugawa Shogunate

was overthrown and the Empire of Japan

under Emperor Meiji

was established. With the return of power to the Tenno Dynasty

, Japan demanded a revocation of the "unequal treaties" with the western powers and a civil war ensued. During the conflict, German weapons trader Henry Schnell counselled and supplied weapons to the Daimyo

of Nagaoka

, a land lord loyal to the Shogunate. One year later, the war ended with the defeat of the Tokugawa and the renegotiation of the "unequal treaties".

With the start of the Meiji period

With the start of the Meiji period

(1868–1912), many Germans came to work in Japan as advisors to the new government as so-called "oyatoi gaikokujin" and contributed to the modernization

of Japan, especially in the fields of medicine (Leopold Mueller, 1824–1894; Julius Scriba

, 1848–1905; Erwin Bälz

, 1849–1913), law (K. F. Hermann Roesler

, 1834–1894; Albert Mosse

, 1846–1925) and military affairs (K. W. Jacob Meckel, 1842–1906). Meckel had been invited by Japan's government in 1885 as an advisor to the Japanese general staff and as teacher at the Army War College

. He spent three years in Japan, working with influential persons including Katsura Tarō

and Kawakami Soroku

, thereby decisively contributing to the modernization of the Imperial Japanese Army

. Meckel left behind a loyal group of Japanese admirers, who, after his death, had a bronze statue of him erected in front of his former army college in Tokyo. Overall, the Imperial Japanese Army intensively oriented its organization along Prusso-German lines when building a modern fighting force during the 1880s. The French model that had been followed by the late shogunate and the early Meiji government was gradually replaced by the Prussian model under the leadership of officers such as Katsura Taro and Nogi Maresuke.

In 1889 the ‘Constitution of the Empire of Japan’ was promulgated, greatly influenced by German legal scholars Rudolf von Gneist and Lorenz von Stein

, whom the Meiji oligarch

and future Prime Minister of Japan

Itō Hirobumi

(1841–1909) visited in Berlin and Vienna

in 1882. At the request of the German government, Albert Mosse also met with Hirobumi and his group of government officials and scholars and gave a series of lectures on constitutional law

, which helped to convince Hirobumi that the Prussian-style monarchical constitution was best-suited for Japan. In 1886 Mosse was invited to Japan on a three-year contract as "hired foreigner" to the Japanese government to assist Hirobumi and Inoue Kowashi

in drafting the Meiji Constitution

. He later worked on other important legal drafts, international agreements, and contracts and served as a cabinet advisor in the Home Ministry

, assisting Prime Minister Yamagata Aritomo

in establishing the draft laws and systems for local government. Dozens of Japanese students and military officers also went to Germany in the late 19th century, to study the German military system and receive military training at German army educational facilities and within the ranks of the German, mostly the Prussian army. For example later famous writer Mori Rintarô (Mori Ōgai

), who originally was an army doctor, received tutoring in the German language between 1872 and 1874, which was the primary language for medical education at the time. From 1884 to 1888, Ōgai visited Germany and developed an interest in European literature producing the first translations of the works of Goethe, Schiller, Ibsen, Hans Christian Andersen

, and Gerhart Hauptmann

.

. After the conclusion of the First Sino-Japanese War

in April 1895, the Treaty of Shimonoseki

was signed, which included several territorial cessions from China to Japan, most importantly Taiwan

and the eastern portion of the bay of the Liaodong Peninsula including Port Arthur

. However, Russia

, France

and Germany grew wary of an ever-expanding Japanese sphere of influence and wanted to take advantage of China's bad situation by expanding their own colonial possessions instead. The frictions culminated in the so-called "Triple Intervention

" on 23 April 1895, when the three powers "urged" Japan to refrain from acquiring its awarded possessions on the Liaodong Peninsula. In the following years, Wilhelm II’s nebulous fears of a “Yellow Peril

” – a united Asia under Japanese leadership, led to further Japanese–German estrangement. Wilhelm II also introduced a regulation to limit the number of members of the Japanese army to come to Germany to study the military system.

Another stress test for German–Japanese relations was the Russo-Japanese War

of 1904/05, during which Germany strongly supported Russia, e.g. by supplying Russian warships with coal. This circumstance triggered the Japanese foreign ministry to proclaim that any ship delivering coal to Russian vessels within the war zone would be sunk. After the Russo-Japanese War, Germany insisted on reciprocity in the exchange of military officers and students, and in the following years, several German military officers were sent to Japan to study the Japanese military, which, after its victory over the tsarist army became a promising organization to study. However, Japan's growing power and influence also caused increased distrust on the German side.

The onset of the First World War in Europe eventually showed how far German–Japanese relations had truly deteriorated. On 7 August 1914, only two days after Britain declared war on the German Empire, the Japanese government received an official request from the British government for assistance in destroying the German raiders of the Kaiserliche Marine

The onset of the First World War in Europe eventually showed how far German–Japanese relations had truly deteriorated. On 7 August 1914, only two days after Britain declared war on the German Empire, the Japanese government received an official request from the British government for assistance in destroying the German raiders of the Kaiserliche Marine

in and around Chinese waters. Japan, eager to reduce the presence of European colonial powers in South-East Asia, especially on China's coast, sent Germany an ultimatum

on 14 August 1914, which was left unanswered. Japan then formally declared war on the German Empire

on 23 August 1914 thereby entering the First World War as an ally of Britain, France and the Russian Empire

to seize the German colonial territories of South-East Asia

.

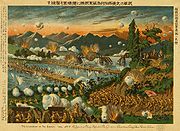

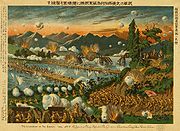

The only major battle that took place between Japan and Germany was the siege of the German-controlled Chinese port of Tsingtao in Kiautschou Bay. The German forces held out from August until November 1914, under a total Japanese/British blockade, sustained artillery barrages and manpower odds of 6:1 – a fact that gave a morale boost during the siege as well as later in defeat. After Japanese troops stormed the city, the German dead were buried at Tsingtao and the remaining troops were transported to Japan where they were treated with respect at places like the Bandō Prisoner of War camp

. In 1919, when the German Empire formally signed the Treaty of Versailles

, all prisoners of war were set free and returned to Europe.

Japan was a signatory of the Treaty of Versailles, which stipulated harsh repercussions for Germany. In the Pacific, Japan gained Germany's islands north of the equator (the Marshall Islands

, the Carolines, the Marianas, the Palau Islands

) and Kiautschou/Tsingtao

in China. Article 156 of the Treaty also transferred German concessions in Shandong

to Japan rather than returning sovereign authority to China, an issue soon to be known as Shandong Problem

. Chinese outrage over this provision led to demonstrations, and a cultural movement known as the May Fourth Movement

influenced China not to sign the treaty. China declared the end of its war against Germany in September 1919 and signed a separate treaty with Germany in 1921. This fact greatly contributed to Germany relying on China, and not Japan, as its strategic partner in East Asia for the coming years.

After Germany had to cede most of former German New Guinea

After Germany had to cede most of former German New Guinea

and Kiautschou/Tsingtao to Japan and with an intensifying Sino-German cooperation, relations between Berlin and Tokyo were nearly dead. Under the initiative of Wilhelm Solf

, who served as German ambassador to Japan from 1920 to 1928, cultural exchange was strengthened again, culminating in the re-establishment of the "German-Japanese Society" (1926), the founding of the "Japanese-German Cultural Society" (1927), and of the "Japanese-German Research Institute" (1934).

Despite experiencing contrasting fortunes regarding the First World War, both Japan and Germany changed their direction toward democratic systems of government during the 1920s, with German–Japanese relations being limited to cultural exchanges. However, parliamentary government was not deeply rooted in either country and did not withstand the economic and political pressures of the 1930s

, during which anti-democratic elements became increasingly influential in both countries. These shifts in power were made possible partly by the ambiguity and imprecision of the Meiji Constitution

in Japan and the Weimar Constitution

in Germany, especially with regard to the positions of the Japanese Emperor and the German Reichspräsident

in relation to their respective constitutions. With the rise of militarism in Japan and Nazism

in Germany in the 1930s, political ties between both countries became closer again, intensifying the existing cultural exchange. On the Japanese side, army officer Hiroshi Ōshima

particularly advocated a closer relationship with Germany and, together with German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

, worked for an alliance when he became military attaché in Berlin in 1934. Over the following decade, Ōshima would serve twice (1938–39 and 1941–45) as ambassador to Berlin, always remaining one of the strongest proponents of Japan's close partnership with Nazi Germany.

A temporary strain was put on German-Japanese rapprochement in June 1935, when the Anglo-German Naval Agreement

was signed between the United Kingdom and Nazi Germany, one of many attempts by Adolf Hitler

to improve relations between the two countries. After all, Hitler had already laid down his plans in Mein Kampf

, in which he identified England as a promising partner, but also defined Japan as a target of "international jewry", and thus a possible ally:

At the time, many Japanese politicians, including Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto

(who was an outspoken critic of an alliance with Nazi Germany), were shocked by the Anglo-German Naval Agreement. Nevertheless, the leaders of the military clique then in control in Tokyo concluded that it was a ruse designed to buy the Nazis time to match the British navy.

". In general, further expansion was envisioned – either northwards, attacking the Soviet Union

, a plan which was called "Hokushin", or by seizing French, Dutch and/or British colonies to the south, a concept dubbed "Nanshin

". Hitler, on the other hand, never desisted from his plan to conquer new territories in Eastern Europe for Lebensraum

; thus, conflicts with Poland

and later with the Soviet Union

seemed inevitable. The first legal consolidation of German-Japanese mutual interests occurred in 1936, when the two countries signed the Anti-Comintern Pact

, which was directed against the Communist International (Comintern) in general and the Soviet Union in particular. After the signing, Nazi Germany's government also included the Japanese people

in their concept of "honorary Aryan

s". Fascist Italy

, led by Benito Mussolini

joined the pact in 1937, initiating the formation of the so-called Axis between Rome, Berlin and Tokyo.

Originally, Germany had a very close relationship with the Chinese nationalist government, even providing military aid and assistance to the Republic of China

. Relations soured after the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War

on 7 July 1937, and when China shortly thereafter concluded the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact with the Soviet Union. Eventually Hitler concluded that Japan, not China, would be a more reliable geostrategic partner, notwithstanding the superior Sino-German economic relationship and chose to end his alliance with the Chinese as the price of gaining an alignment with the more modern and powerful Japan. In a May 1938 address to the Reichstag, Hitler announced German recognition of Manchukuo

, the Japanese-occupied puppet state in Manchuria

, and renounced the German claims to the former colonies in the Pacific held by Japan. Hitler ordered the end of arm shipments to China, as well as the recall of all German officers attached to the Chinese Army. Despite this move, however, Hitler retained his general perception of neither the Japanese nor the Chinese civilizations being inferior to the German one. In The Political Testament of Adolf Hitler, he wrote:

During the late 1930s, though motivated by political and propaganda reasons, several cultural exchanges between Japan and Germany took place. A focus was put on youth exchanges, and numerous mutual visits were conducted; for instance, in late 1938, the ship Gneisenau

carried a delegation of 30 members of the Hitlerjugend to Tokyo for a study visit.

In 1938, representative measures for embracing the German-Japanese partnership were sought and the construction of a new Japanese embassy building in Berlin was started. After the preceding embassy had to give way to Hitler's and Albert Speer

's plans of re-modeling Berlin to the world capital city of Germania

, a new and more pompous building was erected in a newly established diplomatic district next to the Tiergarten

. It was conceived by Ludwig Moshamer under the supervision of Speer and was placed opposite the Italian embassy, thereby bestowing an architectural emphasis on the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo axis.

Despite tentative plans for a joint German-Japanese approach against the USSR which were slowly maturing and regardless of the 1936 Anti Comintern Pact, the years 1938 and 1939 were already decisive for Japan's decision to finally expand south, instead of north. The Empire decisively lost two border fights against the Soviets, the Battles of Lake Khasan

and Khalkin Gol

, thereby convincing itself that the Imperial Japanese Army

, lacking heavy tanks and the like, would be in no position to challenge the Red Army

at that time. Nevertheless, Hitler's anti-Soviet sentiment soon led to further rapprochements with Japan, since he still believed that Japan would join Germany in a future war against the Soviet Union, either actively by invading southeast Siberia

, or passively by binding large parts of the Red Army

, which was fearing an attack of Japan's Kwantung Army in Manchukuo

, numbering ca. 700,000 men as of the late 1930s.

In contrast to his actual plans, Hitler's concept of stalling – in combination with his frustration with a Japan embroiled in seemingly endless negotiations with the United States, and tending against a war with the USSR – led to a temporary cooperation with the Soviets in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which was signed in August 1939. Neither Japan nor Italy had been informed beforehand of Germany's pact with the Soviets, demonstrating the constant subliminal mistrust between Nazi Germany and its partners. After all, the pact not only stipulated the division of Poland between both signatories in a secret protocol, but also rendered the Anti-Comintern Pact more or less irrelevant. In order to remove the strain that Hitler's move had put on German–Japanese relations, the "Agreement for Cultural Cooperation between Japan and Germany" was signed in November 1939, only a few weeks after Germany and the Soviet Union had concluded their invasion of Poland

In contrast to his actual plans, Hitler's concept of stalling – in combination with his frustration with a Japan embroiled in seemingly endless negotiations with the United States, and tending against a war with the USSR – led to a temporary cooperation with the Soviets in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which was signed in August 1939. Neither Japan nor Italy had been informed beforehand of Germany's pact with the Soviets, demonstrating the constant subliminal mistrust between Nazi Germany and its partners. After all, the pact not only stipulated the division of Poland between both signatories in a secret protocol, but also rendered the Anti-Comintern Pact more or less irrelevant. In order to remove the strain that Hitler's move had put on German–Japanese relations, the "Agreement for Cultural Cooperation between Japan and Germany" was signed in November 1939, only a few weeks after Germany and the Soviet Union had concluded their invasion of Poland

and Great Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany.

Over the following year, Japan also proceeded with its expansion plans. The Invasion of French Indochina on 2 September 1940 (which by then was controlled by the collaborating governmment of Vichy France

), and Japan's ongoing bloody conflict with China

, put a severe strain on American-Japanese relations. On 26 July 1940, the United States

passed the Export Control Act

, cutting oil, iron and steel exports to Japan. This containment policy was Washington's warning to Japan that any further military expansion would result in further sanctions. However, such US moves were interpreted by Japan's militaristic leaders as signals that they needed to take radical measures to improve the Empire's situation, thereby driving Japan closer to Germany.

including France, but also maintaining the impression of a Britain facing imminent defeat

, Tokyo interpreted the situation in Europe as proof of a fundamental and fatal weakness in western democracies. Japan's leadership concluded that the current state of affairs had to be exploited and subsequently started to seek even closer cooperation with Berlin. Hitler, for his part, not only feared a lasting stalemate with Britain, but also had started planning an invasion of the Soviet Union. These circumstances, together with a shortage in raw materials and food, increased Berlin's interest in a stronger alliance with Japan. German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

was sent to negotiate a new treaty with Japan, whose relationships with Germany and Italy, the three soon to be called "Axis powers", were cemented with the Tripartite Pact

of 27 September 1940.

The purpose of the Pact, directed against an unnamed power presumed to be the United States, was to deter that power from supporting Britain, thereby not only strengthening Germany's and Italy's cause in the North African Campaign

and the Mediterranean theatre

, but also weakening British colonies in South-East Asia in advance of a Japanese invasion. The treaty stated that the three countries would respect each other's "leadership" in their respective spheres of influence

, and would assist each other if attacked by an outside party. However, already-ongoing conflicts, as of the signing of the Pact, were explicitly excluded. With this defensive terminology, aggression on the part of a member state toward a non-member state would result in no obligations under the Pact. Relations between Germany and Japan were driven by mutual self-interest, underpinned by the shared militarist, expansionist and nationalistic ideologies of their respective governments.

Another decisive limitation in the German-Japanese alliance were the fundamental differences between the two nation's policies towards Jews. With Nazi Germany's well-known attitude being extreme Antisemitism, Japan refrained from adapting any similar posture. On 31 December 1940, Japanese foreign minister Yōsuke Matsuoka

, a strong proponent of the Tripartite Pact, told a group of Jewish businessmen:

Until 1945, both countries would continue to conceal any war crimes committed by the other side. The Holocaust

was systematically concealed by the leadership in Tokyo, just as Japanese war crimes

, e.g. the situation in China, were kept secret from the German public. Another example is the atrocities committed by the Japanese Army in Nanking in 1937

, which were denounced by German industrialist John Rabe

. Subsequently, the German leadership ordered Rabe back to Berlin, confiscating all his reports and prohibiting any further discussion of the topic.

After the signing of the Tripartite Pact, mutual visits of political and military nature increased. After German ace and parachute expert Ernst Udet

visited Japan in 1939 to inspect the Japanese aerial forces, reporting to Hermann Göring

that "Japanese flyers, though brave and willing, are no sky-beaters", General Tomoyuki Yamashita

was given the job of reorganizing the Japanese Air Arm in late 1940. For this purpose, Yamashita arrived in Berlin in January 1941, staying almost six months. He inspected the broken Maginot Line

and German fortifications on the French coast, watched German flyers in training, and even flew in a raid over Britain

after decorating Hermann Göring

, head of the German Luftwaffe

, with the Japanese "Grand Cordon of the Rising Sun". General Yamashita also met and talked with Hitler, on whom he commented,

According to Yamashita, Hitler promised to remember Japan in his will, by instructing the Germans "to bind themselves eternally to the Japanese spirit." In fact, General Yamashita was so excited that he said: "In a short time, something great will happen. You just watch and wait." Returning home, the Japanese delegation was accompanied by more than 250 German technicians, engineers and instructors. Soon, Japan's Air Force was among the most powerful in the world.

On 11 November 1940, German–Japanese relations, as well as Japan's plans to expand southwards into South-East Asia, were decisively bolstered when the crew of the German auxiliary cruiser Atlantis

boarded the British cargo ship . Fifteen bags of Top Secret

mail for the British Far East Command

were found, including naval intelligence reports containing the latest assessment of the Japanese Empire's military strength in the Far East, along with details of Royal Air Force

units, naval strength, and notes on Singapore

's defences. It painted a gloomy picture of British land and naval capabilities in the Far East, and declared that Britain was too weak to risk war with Japan. The mail reached the German embassy in Tokyo on 5 December, and was then hand-carried to Berlin via the Trans-Siberian railway

. A copy was given to the Japanese; it provided valuable intelligence prior to their commencing hostilities against the Western Powers. The captain of the Atlantis, Bernhard Rogge

, was rewarded for this with an ornate katana

Samurai sword; the only other Germans so honored were Hermann Göring

and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel

.

After reading the captured documents, on 7 January 1941 Japanese Admiral Yamamoto wrote to the Naval Minister asking whether, if Japan knocked out America, the remaining British and Dutch forces would be suitably weakened for the Japanese to deliver a deathblow. Thereby, Nanshin-ron

, the concept of the Japanese Navy conducting a southern campaign quickly matured and gained further proponents.

Hitler on the other hand was concluding the preparations for "Operation Barbarossa

Hitler on the other hand was concluding the preparations for "Operation Barbarossa

", the invasion of the Soviet Union. In order to directly or indirectly support his imminent eastward strike, the Führer had repeatedly suggested to Japan that it reconsider plans for an attack on the Soviet Far East throughout 1940 and 1941. In February 1941, as a result of Hitler's insistence, General Oshima returned to Berlin as Ambassador. On 5 March 1941, Wilhelm Keitel

, chief of OKW issued "Basic Order Number 24 regarding Collaboration with Japan":

On 18 March 1941, at a conference attended by Hitler, Alfred Jodl

, Wilhelm Keitel

and Erich Raeder

, Admiral Raeder stated:

In talks involving Hitler, his foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

, his Japanese counterpart at that time, Yōsuke Matsuoka

, as well as Berlin's and Tokyo's respective ambassadors, Eugen Ott

and Hiroshi Ōshima

, the German side then broadly hinted at, but never openly asked for, either invading the Soviet Union

from the east or attacking Britain's colonies in South-East Asia, thereby preoccupying and diverting the British Empire away from Europe and thus somewhat covering Germany's back. Although Germany would have clearly favored Japan's attacking the USSR, exchanges between the two allies were always kept overly formal and indirect, as shown in the following statement by Hitler to ambassador Ōshima (2 June 1941):

Matsuoka, Ōshima and parts of the Japanese Imperial Army were proponents of "Hokushin", Japan's go-north strategy aiming for a coordinated attack with Germany against the USSR and seizing East Siberia. But the Japanese army-dominated military leadership, namely persons like minister of war

Hideki Tōjō

, were constantly pressured by the Japanese Imperial Navy and, thus, a strong tendency towards "Nanshin

" existed already in 1940, meaning to go south and exploit the weakened European powers by occupying their resource-rich colonies in South-East Asia. In order to secure Japan's back while expanding southwards and as a Soviet effort to demonstrate peaceful intentions toward Germany, the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact was signed in Moscow on 13 April 1941 by Matsuoka on his return trip from a visit to Berlin. Hitler, who was not informed in advance by the Japanese and considering the pact a ruse to stall, misinterpreted the diplomatic situation and thought that his attack on the USSR would bring a tremendous relief for Japan in East Asia and thereby a much stronger threat to American activities through Japanese interventions. As a consequence, Nazi Germany pressed forward with Operation Barbarossa, its attack on the Soviet Union, which started two months later on 22 June without any specific warning to its Axis partners.

Joseph Stalin

had little faith in Japan's commitment to neutrality even before the German attack, but he felt that the pact was important for its political symbolism, to reinforce a public affection for Germany. From Japan's point of view the attack on Russia very nearly ruptured the Tripartite Pact on which the Empire was depending for Germany's aid in maintaining good relations with Moscow so as to preclude any threat from Siberia. Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe

felt betrayed because the Germans clearly trusted their Axis allies too little to warn them of Barbarossa, even though he had feared the worst since receiving an April report from Ōshima in Berlin that "Germany is confident she can defeat Russia and she is preparing to fight at any moment." Foreign minister Matsuoka on the other hand vividly tried to convince the Emperor, the cabinet as well as the army staff of an immediate attack on the Soviet Union. However, his colleagues rejected any such proposal, even regarding him as "Hitler's office boy" by now and pointed out to the fact that the Japanese army, with its light and medium tanks, had no intention of taking on Soviet tanks and aircraft until they could be certain that the Wehrmacht

had smashed the Red Army to the brink of defeat.

Subsequently, Konoe removed Matsuoka from his cabinet and stepped up Japan's negotiations with the US again, which still failed over the China and Indochina issues, however, and the American demand to Japan to withdraw from the Tripartite Pact in anticipation of any settlement. Without any perspective with respect to Washington, Matsuoka felt that his government had to reassure Germany of its loyalty to the pact. In Berlin, Ōshima was ordered to convey to the German foreign minister Ribbentrop that the "Japanese government have decided to secure 'points d'appui' in French Indochina to enable further to strengthen her pressure on Great Britain and the United States of America," and to present this as a "valuable contribution to the common front" by promising that "We Japanese are not going to sit on the fence while you Germans fight the Russians."

Over the first months, Germany's advances in Soviet Russia were spectacular and Stalin's need to transfer troops currently protecting South-East Siberia from a potential Japanese attack to the future defense of Moscow

Over the first months, Germany's advances in Soviet Russia were spectacular and Stalin's need to transfer troops currently protecting South-East Siberia from a potential Japanese attack to the future defense of Moscow

grew. Japan's Kwantung Army in Manchuria was constantly kept in manoeuvres and, in talks with German foreign minister Ribbentrop, ambassador Oshima in Berlin repeatedly hinted at an "imminent Japanese attack" against the USSR. In fact, however, the leadership in Tokyo at this time had in no way changed its mind and these actions were merely concerted to create the illusion of an eastern threat to the Soviet Union in an effort to bind its Siberian divisions. Unknown to Japan and Germany, however, Richard Sorge

, a Soviet spy disguised as a German journalist working for Eugen Ott, the German ambassador in Tokyo, advised the Red Army on 14 September 1941, that the Japanese were not going to attack the Soviet Union until:

Toward the end of September 1941, Sorge transmitted information that Japan would not initiate hostilities against the USSR in the East, thereby freeing Red Army divisions stationed in Siberia for the defence of Moscow. In October 1941 Sorge was unmasked and arrested by the Japanese. Apparently, he was entirely trusted by the German ambassador Eugen Ott, and was allowed access to top secret cables from Berlin in the embassy in Tokyo. Eventually, this involvement would lead to Heinrich Georg Stahmer

replacing Ott in January 1943. Sorge on the other hand would be executed in November 1944 and elevated to a national hero in the Soviet Union.

, was settled.

On 25 November, Germany tried to further solidify the alliance against Soviet Russia by officially reviving the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1936, now joined by additional signatories, Hungary

and Romania

. However, with the Soviet troops around Moscow now being reinforced by East Siberian divisions, Germany's offensive substantially slowed with the onset of the Russian winter in November and December 1941. In the face of his failing Blitzkrieg

tactics, Hitler's confidence in a successful and swift conclusion of the war diminished, especially with a US-supported Britain being a constant threat in the Reich's western front. Furthermore, it was evident that the "neutrality" which the US had superficially maintained to that point would soon change to an open and unlimited support of Britain against Germany. Hitler thus welcomed Japan's sudden entry into the war with its air raid on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor

on 7 December 1941 and its subsequent declaration of war on the United States and Britain

, just as the German army suffered its first military defeat at the gates of Moscow

. Upon learning of Japan's successful attack, Hitler even became euphoric, stating: "With such a capable ally we cannot lose this war." Preceding Japan's attack were numerous communiqués between Berlin and Tokyo. The respective ambassadors Ott and Ōshima tried to draft an amendment to the Tripartite Pact, in which Germany, Japan and Italy should pledge each other's allegiance in the case one signatory is attacked by – or attacks – the United States. Although the protocol was finished in time, it would not be formally signed by Germany until four days after the raid on Pearl Harbor. Also among the communiqués was another definitive Japanese rejection of any war plans against Russia:

Nevertheless, publicly the German leadership applauded their new ally and ambassador Ōshima became one of only eight recipients of the Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle in Gold

, which was awarded by Hitler himself, who reportedly said:

Although the amendment to the Tripartite Pact was not yet in force, Hitler chose to declare war on the United States and ordered the Reichstag

Although the amendment to the Tripartite Pact was not yet in force, Hitler chose to declare war on the United States and ordered the Reichstag

, along with Italy, to do so on 11 December 1941, three days after the United States' declaration of war

on the Empire of Japan

. His hopes that, despite the previous rejections, Japan would reciprocally attack the Soviet Union, were not realized, as Japan stuck to its Nanshin strategy of going south, not north, and would continue to maintain an uneasy peace with the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, Germany's declaration of war

further solidified German–Japanese relations and showed Germany's solidarity with Japan, which was now encouraged to cooperate against the British. To some degree, Japan's actions in South-East Asia and the Pacific in the months after Pearl Harbor, including the sinking of the HMS Prince of Wales and the HMS Repulse

, the occupation of the Crown Colonies of Singapore

, Hong Kong

, and British Burma

, and the air raids on Australia, were a tremendous blow to the United Kingdom's war effort and preoccupied the Allies, shifting British (including Australian) and American assets away from the Battle of the Atlantic and the North African Campaign

against Germany to Asia and the Pacific against Japan. In this context, sizeable forces of the British Empire were withdrawn from North Africa to the Pacific theatre with their replacements being only relatively inexperienced and thinly spread divisions. Taking advantage of this situation, Erwin Rommel

's Afrika Korps

successfully attacked only six weeks after Pearl Harbor, eventually pushing the allied lines as far east as El Alamein. In the long run, Germany and Japan envisioned a partnered linkage running across the British-held Indian subcontinent

that would allow for the transfer of weaponry, resources as well as other possibilities. After all, the choice of potential trading partners was very limited during the war and Germany was anxious for rubber

and precious metals, while the Japanese sought industrial products, technical equipment, and chemical goods.

Until Germany attacked the Soviet Union, the two countries were able to exchange these materials using the Trans-Siberian Railway

, but after the attack submarines had to be sent on so-called "Yanagi" (Willow) – missions, since the American and British navies rendered the high seas too dangerous for Axis cargo ships. However, given the limited capacities of submarines, eyes were soon focused directly on the Mediterranean

, the Middle East and British India, all vital to the British war effort. Most importantly, though, these regions offered a direct land- and/or sea-linkage between the Third Reich and Japan, which would improve trade possibilities and enable potential joint military operations. By August 1942 the German advances in North Africa rendered an offensive against Alexandria and the Suez Canal

feasible, which, in turn, had the potential of enabling maritime trade between Europe and Japan through the Indian Ocean. On the other hand, in the face of its defeat at the Battle of Midway

in June 1942 with the loss of four aircraft carriers, the Japanese Navy decided to pursue all possibilities of gaining additional resources to quickly rebuild its forces. As a consequence, ambassador Ōshima in Berlin was ordered to submit an extensive "wish list" requesting the purchase of vast amounts of steel and aluminium to be shipped from Germany to Japan. German foreign minister Ribbentrop quickly dismissed Tokyo's proposal, since those resources were vital for Germany's own industry. However, in order to gain Japanese backing for a new German-Japanese trade treaty, which should also secure the rights of German companies in South-East Asia, he asked Hitler to at least partially agree upon the Japanese demands. It took another five months of arguing over the Reichsmark-Yen-exchange rate and additional talks with the third signatory, the Italian government, until the "Treaty on Economic Cooperation" was signed on 20 January 1943.

Despite this treaty, the envisioned German-Japanese economic relations were never able to grow beyond mostly propagandistic status. This was, at least partly, due to the German-Italian loss of North Africa in spring 1943 since the Allies never abandoned their "Germany first" policy throughout the war despite a brief, post-Pearl Harbor shift of their attention. This policy stipulated that Nazi Germany should be defeated before the focus would be shifted to Japan, and thus, with superior communication between them, the Allies, in contrast to the Axis, were able to jointly coordinate massive counter-attacks. These included three decisive movements, all within the first three weeks of November 1942: 1) The British breakthrough at Rommel

Despite this treaty, the envisioned German-Japanese economic relations were never able to grow beyond mostly propagandistic status. This was, at least partly, due to the German-Italian loss of North Africa in spring 1943 since the Allies never abandoned their "Germany first" policy throughout the war despite a brief, post-Pearl Harbor shift of their attention. This policy stipulated that Nazi Germany should be defeated before the focus would be shifted to Japan, and thus, with superior communication between them, the Allies, in contrast to the Axis, were able to jointly coordinate massive counter-attacks. These included three decisive movements, all within the first three weeks of November 1942: 1) The British breakthrough at Rommel

's positions near El Alamein

, 2) the American-British landings in Morocco

and 3) the Soviet offensive

at Stalingrad

. By early 1943 Germany's strategic situation had drastically worsened, thereby putting an end to Hitler's advances towards the Middle East, especially the oil fields of Iran

, as the Wehrmacht's operations would never pass Egypt

and the Caucasus. Additionally, Japan would not be able to recover from its naval losses at Midway and the imperial alternative plan of conquering the Solomons

at Australia's doorstep turned into a continuous retreat for the Japanese of which the defeat on Guadalcanal marked the beginning. Subsequently Japan's invasion of India, already halted in Burma

, rendered any decisive joint operations aimed at a convergence on the Indian subcontinent, aside from the German U-boat flotilla "Monsun Gruppe

" cooperating with the Japanese Navy in the Indian Ocean, impossible. With submarines remaining the only link between Nazi-controlled Europe and Japan, trade was soon focused on strategic goods such as technical plans and weapon templates. Only 20-40% of goods managed to reach either destination and merely 96 persons travelled by submarine from Europe to Japan and 89 vice versa during the war as only six submarines succeeded in their attempts of the trans-oceanic voyage: (April 1942), (June 1943), (October 1943), (November 1943), (March 1944), and the German submarine U-511

(August 1943). U-234

on the other hand is one of the most popular examples of an aborted Yanagi mission in May 1945.

In the face of their failing war plans, Japanese and German representatives more and more began to deceive each other at tactical briefings by exaggerating minor victories and deemphasizing losses. In several talks in spring and summer 1943 between Generaloberst Alfred Jodl

In the face of their failing war plans, Japanese and German representatives more and more began to deceive each other at tactical briefings by exaggerating minor victories and deemphasizing losses. In several talks in spring and summer 1943 between Generaloberst Alfred Jodl

and the Japanese naval attaché

in Berlin, Vice Admiral

Naokuni Nomura

, Jodl downplayed the afore described defeats of the German Army, e.g. by claiming the Soviet offensive would soon run out of steam and that "anywhere the Wehrmacht can be sent on land, it is sure of its untertaking, but where it has to be taken over sea, it becomes somewhat more difficult." Japan, on the other hand, not only evaded any disclosure of its true strategic position in the Pacific, but also declined any interference in American shipments being unloaded at Vladivostok

and large amounts of men and material being transported from East Siberia to the German front in the west. Being forced to watch the continued reinforcement of Soviet troops from the east without any Japanese intervention was a thorn in Hitler's flesh, especially considering Japan's apparent ignorance with respect to the recent Casablanca Conference at which the Allies declared only to accept the unconditional surrenders of the Axis nations. During a private briefing on 5 March 1943, the "Führer" got a rage attack and gave remarks on the Japanese like

As the war progressed and Germany began to retreat further, Japanese ambassador Ōshima never wavered in his confidence that Germany would emerge victorious. However, in March 1945 he reported to Tokyo on the "danger of Berlin becoming a battlefield

" and revealing a fear "that the abandonment of Berlin may take place another month". On 13 April, he met with Ribbentrop — for the last time, it turned out — and vowed to stand with the leaders of the Third Reich in their hour of crisis but had to leave Berlin at once by Hitler's direct order. On 7 and 8 May 1945, as the German government surrendered

to the Allied powers, Ōshima and his staff were taken into custody and brought to the United States. Now fighting an even more hopeless war, the Japanese government immediately denounced the German surrender as an act of treason and interned the few German individuals as well as confiscated all German property (such as submarines) in Japanese territory at the time. Four months later, on 2 September, Japan had to sign its own surrender documents

.

. Here it was the goal of the Allied prosecutors to portray the limited cooperation between the Third Reich and Imperial Japan as a long-planned conspiracy to divide the world among the two Axis-partners and thereby delivering just another demonstration of the common viciousness expressed by alleged joint long-term war plans. According to modern historic research, however, such a consipracy did not exist and is considered Allied propaganda. Although there was a limited and cautious military cooperation between Japan and Germany during the Second World War, no documents corroborating any long-term planning or real coordination of military operations of both powers exist.

in 1952 and joined the United Nations in 1956, Germany was split into two states, which were both founded in 1949. The Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) restored diplomatic ties with Japan in 1955, the German Democratic Republic

as late as 1973, the year both German states became UN-members.

Quickly, academic and scientific exchange was strengthened, and in 1974, West Germany and Japan signed an intergovernmental agreement on cooperation in science and technology, re-intensifying joint scientific endeavours and technological exchange. The accord resulted in numerous bilateral cooperations since then, generally focused on marine research and geosciences, life sciences

and environmental research. Additionally, youth exchange programs were launched, including a "Youth Summit" held annually since 1974.

German-Japanese political exchange further intensified again with both countries taking part in the creation of the so called Group of Six, or simply "G6", together with the US, the UK, France and Italy in 1975 as a response to the 1973 oil crisis

German-Japanese political exchange further intensified again with both countries taking part in the creation of the so called Group of Six, or simply "G6", together with the US, the UK, France and Italy in 1975 as a response to the 1973 oil crisis

. The G6 was soon expanded by Canada and later the Russian Federation, with G6-, G7-, and later G8-, summits being held annually since then.

Over the following years, institutions, such as in 1985 the "Japanese–German Center" (JDZB) in Berlin and in 1988 the "German Institute for Japanese Studies" (DIJ) in Tokyo, were founded to further contribute to the academic and scientific exchange between Japan and Germany.

Around the mid-80s, German and Japanese representatives decided to rebuild the old Japanese embassy in Berlin from 1938. Its remains had remained unused after the building was largely destroyed during World War II. In addition to the original complex, several changes and additions were made until 2000, like moving the main entrance to the Hiroshima Street, which was named in honour of the homonymous Japanese city, and the creation of a traditional Japanese Garden

.

Nevertheless, however, post-war relations between Japan and both halves of Germany, as well as with unified Germany since 1990, have generally been focused on economic questions, and as such, Germany, dedicated to free trade, continues to be Japan’s largest trading partner within Europe until today. This general posture is also reflected in the so called "7 pillars of cooperation" agreed on by Foreign Minister of Japan Yōhei Kōno

and Foreign Minister of Germany Joschka Fischer

on 30 October 2000:

In 2000, bilateral cultural exchange culminated in the "Japan in Germany" year, which was then followed by the "Germany in Japan" year in 2005/2006. Also in 2005, the annual German Film Festival in Tokyo was brought into being.

In 2004, German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder

and Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi

agreed upon cooperations in the assistance for reconstruction of Iraq

and Afghanistan

, the promotion of economic exchange activities, youth and sports exchanges as well as exchanges and cooperation in science, technology and academic fields.

and an increase of the number of its permanent members. For this purpose both nations organized themselves together with Brazil and India to form the so called "G4 nations

". On 21 September 2004, the G4 issued a joint statement mutually backing each other's claim to permanent seats, together with two African countries. This proposal has found opposition in a group of countries called Uniting for Consensus. In January 2006, Japan announced that it would not support putting the G4 resolution back on the table and was working on a resolution of its own.

Certain inefficiencies with respect to the bilateral cooperation between Germany and Japan were also reflected in 2005, when former Japanese Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa

wrote in a commemoration to the 20th anniversary of the Japanese-German Center in Berlin that

Nevertheless, as of 2008, Japan still was Germany's second largest trading partner in Asia after China. In 2006, German imports from Japan totaled €15.6 billion and German exports to Japan €14.2 billion (15.4% and 9% more than the previous year, respectively). In 2008, however, Japanese exports and imports to and from the European Union fell by 7.8 and 4.8% after growing by 5.8% in 2007 due to the global financial crisis. Bilateral trade between Germany and Japan also shrank in 2008, with imports from Japan having dropped by 6.6% and German exports to Japan having declined by 5.5%. Despite Japan having remained Germany's principal trading partner in Asia after China in 2008, measured in terms of total German foreign trade, Japan’s share of both exports and imports is relatively low and falls well short of the potential between the world’s third- and fourth-largest economies.

On 14 and 15 January 2010, German foreign minister Guido Westerwelle

conducted his personal inaugural visit to Japan, focusing the talks with his Japanese counterpart, Katsuya Okada

, on both nation's bilateral relations and global issues. Westerwelle emphasized, that and both ministers instructed their Ministries to draw up disarmament initiatives and strategies which Berlin and Tokyo can present to the international community together. Especially with regard to Iran's nuclear program, it was also stressed that Japan and Germany, both technically capable of and yet refraining from possessing any ABC weapons, should assume a leading role in realizing a world free of nuclear weapons and that international sanctions

are considered to be an appropriate instrument of pressure. Furthermore, Westerwelle and Okada agreed to enhance cooperation in Afghanistan and to step up the stagnating bilateral trade between both countries. The visit was concluded in talks with Japan's Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama

, before which the German foreign minister visited the famous Meiji Shrine

in the heart of Tokyo.

On Friday 11 March 2011, the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami

, the most powerful known earthquake to hit Japan at the time, and one of the five most powerful recorded earthquakes of which Japanese Prime Minister Naoto Kan

said, "In the 65 years after the end of World War II, this is the toughest and the most difficult crisis for Japan." hit Honshu

. The earthquake and the resulting tsunami

not only devastated wide coastal areas in Miyagi Prefecture

but also caused the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster

triggering a widespread permanent evacuation surrounding the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant

. German chancellor Angela Merkel

immediately expressed her deepest sympathy to all those affected and promised Japan any assistance it would call for. As a consequence rescue specialists from the Technisches Hilfswerk

as well as a scout team of I.S.A.R. Germany (International Search and Rescue) were sent to Japan, however parts of the German personnel had to be recalled due to radiation danger near the damaged power plant. Furthermore, the German Aerospace Center

provided TerraSAR-X

- and RapidEye

-satellite imagery of the affected area. In the days after the disaster, numerous flowers, candles and paper cranes were placed in front of the Japanese embassy in Berlin by compassionates, including leading German politicians. Though never materialised, additional proposals for aid included sending special units of the German Bundeswehr

to Japan, as the German Armed Forces' decontamination equipment belongs to the most sophisticated in the world.

On 2 April 2011, German Foreign Minister Westerwelle visited Tokyo on an Asia voyage, again offering Japan "all help, where it is needed" to recover from the tsunami and subsequent nuclear disaster of the previous month. Westerwelle also emphasised the importance of making progress with a free trade agreement between Japan and the European Union

in order to accelerate the recovery of the Japanese economy. Together with his German counterpart, Japanese foreign minister Takeaki Matsumoto

also addressed potential new fields of cooperation between Tokyo and Berlin with respect to a reform of the United Nations Security Council

.

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the and the , was a feudal regime of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family. This period is known as the Edo period and gets its name from the capital city, Edo, which is now called Tokyo, after the name was...

in 1603, Japan isolated itself from the outside world until the Meiji Restoration

Meiji Restoration

The , also known as the Meiji Ishin, Revolution, Reform or Renewal, was a chain of events that restored imperial rule to Japan in 1868...

of 1867, when it began to accept contact with Western nations. German–Japanese relations were established in 1860 with the first ambassadorial visit to Japan

Japan

Japan is an island nation in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean, it lies to the east of the Sea of Japan, China, North Korea, South Korea and Russia, stretching from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea and Taiwan in the south...

from Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

(which predated the formation of the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

in 1871). After a time of intense intellectual and cultural exchange

O-yatoi gaikokujin

The Foreign government advisors in Meiji Japan, known in Japanese as oyatoi gaikokujin , were those foreign advisors hired by the Japanese government for their specialized knowledge to assist in the modernization of Japan at the end of the Bakufu and during the Meiji era. The term is sometimes...

in the late 19th century, the two empires' conflicting aspirations in China led to a cooling of relations. Japan allied itself with Britain in World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, declaring war on Germany in 1914 and seizing key German possessions in Asia.

In the 1930s, both countries rejected democracy in all but name, and adopted militaristic attitudes toward their respective regions. This led to a rapprochement and, eventually, a political and military alliance that included Italy: the "Axis

Axis Powers

The Axis powers , also known as the Axis alliance, Axis nations, Axis countries, or just the Axis, was an alignment of great powers during the mid-20th century that fought World War II against the Allies. It began in 1936 with treaties of friendship between Germany and Italy and between Germany and...

". During the Second World War, however, the Axis was limited by the great distances between the Axis powers; for the most part, Japan and Germany fought separate wars, and eventually surrendered separately.

After the Second World War, the economies of both nations experienced rapid recoveries; bilateral relations, now focused on economic issues, were soon re-established. Today, Japan and Germany are, respectively, the third and fourth largest economies in the world (after the U.S. and China) and benefit greatly from many kinds of political, cultural, scientific and economic cooperation.

First contacts and end of Japanese isolation (before 1871)

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the and the , was a feudal regime of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family. This period is known as the Edo period and gets its name from the capital city, Edo, which is now called Tokyo, after the name was...

(1603–1868), when Germans in Dutch service arrived in Japan to work for the Dutch East India Company

Dutch East India Company

The Dutch East India Company was a chartered company established in 1602, when the States-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly to carry out colonial activities in Asia...

(VOC). The first well-documented cases are those of the physicians Engelbert Kaempfer

Engelbert Kaempfer

Engelbert Kaempfer , a German naturalist and physician is known for his tour of Russia, Persia, India, South-East Asia, and Japan between 1683 and 1693. He wrote two books about his travels...

(1651–1716) and Philipp Franz von Siebold

Philipp Franz von Siebold

Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold was a German physician and traveller. He was the first European to teach Western medicine in Japan...

(1796–1866) in the 1690s and the 1820s respectively. Siebold was allowed to travel throughout Japan, in spite of the restrictive seclusion policy which the Tokugawa shogunate

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the and the , was a feudal regime of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family. This period is known as the Edo period and gets its name from the capital city, Edo, which is now called Tokyo, after the name was...

had implemented in the 1630s. Siebold became the author of Nippon, Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan (Nippon, Archive For The Description of Japan), one of the most valuable sources of information on Japan well into the 20th century; since 1979 his achievements have been recognised with an annual German award in his honour, the Philipp Franz von Siebold-Preis, granted to Japanese scientists.

In 1854 the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

pressured Japan into the Convention of Kanagawa

Convention of Kanagawa

On March 31, 1854, the or was concluded between Commodore Matthew C. Perry of the U.S. Navy and the Tokugawa shogunate.-Treaty of Peace and Amity :...

, which ended Japan's isolation, but was considered an "unequal treaty" by the Japanese public, since the US did not reciprocate most of Japan's concessions with similar privileges. In many cases Japan was effectively forced into a system of extraterritoriality that provided for the subjugation of foreign residents to the laws of their own consular courts instead of the Japanese law system, open up ports for trade, and later even allow Christian missionaries to enter the country. Shortly after the end of Japan's seclusion, in a period called "Bakumatsu" (幕末, "End of the Shogunate"), the first German traders arrived in Japan. In 1860 Count Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg

Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg

Count Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg was a Prussian diplomat and politician. He led the Eulenburg Expedition and secured the Prusso-Japanese Treaty of 24 January 1861, which was similar to other unequal treaties that European powers held Eastern Countries to.-Biography :Eulenburg was born in...

led the Eulenburg Expedition

Eulenburg Expedition

The Eulenburg Expedition was a diplomatic mission conducted by Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg on behalf of Prussia and the German Customs Union in 1859-62...

to Japan as ambassador from Prussia, a leading regional state in the German Confederation

German Confederation

The German Confederation was the loose association of Central European states created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to coordinate the economies of separate German-speaking countries. It acted as a buffer between the powerful states of Austria and Prussia...

at that time. After four months of negotiations, another "unequal treaty", officially dedicated to amity and commerce, was signed in January 1861 between Prussia and Japan.

Despite being considered one of the numerous unjust negotiations pressed on Japan during that time, the Eulenburg Expedition, and both the short- and long-term consequences of the treaty of amity and commerce, are today honoured as the beginning of official Japanese-German relations. To commemorate its 150th anniversary, events were held in both Germany and Japan from autumn 2010 through autumn 2011 hoping "to 'raise the treasures of [their] common past' in order to build a bridge to the future."

Japanese diplomatic mission in Prussia

In 1863, three years after Eulenberg's visit in Tokyo, a Shogunal legation arrived at the Prussian court of King Wilhelm I and was greeted with a grandiose ceremony in Berlin. After the treaty was signed, Max von BrandtMax von Brandt

Maximilian August Scipio von Brandt was a German diplomat, East Asia expert and publicist.- Biography :...

became diplomatic representative in Japan – first representing Prussia, and after 1866 representing the North German Confederation

North German Confederation

The North German Confederation 1866–71, was a federation of 22 independent states of northern Germany. It was formed by a constitution accepted by the member states in 1867 and controlled military and foreign policy. It included the new Reichstag, a parliament elected by universal manhood...

, and by 1871 representing the newly established German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

.

In 1868 the Tokugawa Shogunate

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the and the , was a feudal regime of Japan established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and ruled by the shoguns of the Tokugawa family. This period is known as the Edo period and gets its name from the capital city, Edo, which is now called Tokyo, after the name was...

was overthrown and the Empire of Japan

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

under Emperor Meiji

Emperor Meiji

The or was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, reigning from 3 February 1867 until his death...

was established. With the return of power to the Tenno Dynasty

Emperor of Japan

The Emperor of Japan is, according to the 1947 Constitution of Japan, "the symbol of the state and of the unity of the people." He is a ceremonial figurehead under a form of constitutional monarchy and is head of the Japanese Imperial Family with functions as head of state. He is also the highest...

, Japan demanded a revocation of the "unequal treaties" with the western powers and a civil war ensued. During the conflict, German weapons trader Henry Schnell counselled and supplied weapons to the Daimyo

Daimyo

is a generic term referring to the powerful territorial lords in pre-modern Japan who ruled most of the country from their vast, hereditary land holdings...

of Nagaoka

Nagaoka, Niigata

is a city located in the central part of Niigata Prefecture, Japan. It is the second largest city in the prefecture, behind the capital city of Niigata...

, a land lord loyal to the Shogunate. One year later, the war ended with the defeat of the Tokugawa and the renegotiation of the "unequal treaties".

Modernization of Japan and educational exchange (1871 to 1885)

Meiji period

The , also known as the Meiji era, is a Japanese era which extended from September 1868 through July 1912. This period represents the first half of the Empire of Japan.- Meiji Restoration and the emperor :...

(1868–1912), many Germans came to work in Japan as advisors to the new government as so-called "oyatoi gaikokujin" and contributed to the modernization

Modernization

In the social sciences, modernization or modernisation refers to a model of an evolutionary transition from a 'pre-modern' or 'traditional' to a 'modern' society. The teleology of modernization is described in social evolutionism theories, existing as a template that has been generally followed by...

of Japan, especially in the fields of medicine (Leopold Mueller, 1824–1894; Julius Scriba

Julius Scriba

Julius Karl Scriba was a German surgeon serving as a foreign advisor in Meiji period Japan, where he was an important contributor to the development of Western medicine in Japan.- Biography :...

, 1848–1905; Erwin Bälz

Erwin Bälz

Erwin Bälz was a German internist, anthropologist, personal physician to the Japanese Imperial Family and cofounder of modern medicine in Japan.- Biography :...

, 1849–1913), law (K. F. Hermann Roesler

Hermann Roesler

Karl Friedrich Hermann Roesler was a German legal scholar, economist, and foreign advisor to the Meiji period Empire of Japan.-Life in Japan:...

, 1834–1894; Albert Mosse

Albert Mosse

Isaac Albert Mosse was a German judge and legal scholar. Mosse's importance lies in the working out of Japan's Meiji Constitution and his continuation of Litthauer's Comments on the German Commercial Code.-Biography:...

, 1846–1925) and military affairs (K. W. Jacob Meckel, 1842–1906). Meckel had been invited by Japan's government in 1885 as an advisor to the Japanese general staff and as teacher at the Army War College

Army War College (Japan)

The ; Short form: of the Empire of Japan was founded in 1882 in Minato, Tokyo to modernize and Westernize the Imperial Japanese Army. Much of the empire's elite including prime ministers during the period of Japanese militarism were graduates of the college....

. He spent three years in Japan, working with influential persons including Katsura Tarō

Katsura Taro

Prince , was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army, politician and three-time Prime Minister of Japan.-Early life:Katsura was born into a samurai family from Hagi, Chōshū Domain...

and Kawakami Soroku

Kawakami Soroku

- Notes :...

, thereby decisively contributing to the modernization of the Imperial Japanese Army

Imperial Japanese Army

-Foundation:During the Meiji Restoration, the military forces loyal to the Emperor were samurai drawn primarily from the loyalist feudal domains of Satsuma and Chōshū...

. Meckel left behind a loyal group of Japanese admirers, who, after his death, had a bronze statue of him erected in front of his former army college in Tokyo.

In 1889 the ‘Constitution of the Empire of Japan’ was promulgated, greatly influenced by German legal scholars Rudolf von Gneist and Lorenz von Stein

Lorenz von Stein

Lorenz von Stein was a German economist, sociologist, and public administration scholar from Eckernförde. As an advisor to Meiji period Japan, his conservative political views influenced the wording of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan.- Biography :Stein was born in the seaside town of Borby...

, whom the Meiji oligarch

Oligarchy

Oligarchy is a form of power structure in which power effectively rests with an elite class distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, commercial, and/or military legitimacy...

and future Prime Minister of Japan

Prime Minister of Japan

The is the head of government of Japan. He is appointed by the Emperor of Japan after being designated by the Diet from among its members, and must enjoy the confidence of the House of Representatives to remain in office...

Itō Hirobumi

Ito Hirobumi

Prince was a samurai of Chōshū domain, Japanese statesman, four time Prime Minister of Japan , genrō and Resident-General of Korea. Itō was assassinated by An Jung-geun, a Korean nationalist who was against the annexation of Korea by the Japanese Empire...

(1841–1909) visited in Berlin and Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

in 1882. At the request of the German government, Albert Mosse also met with Hirobumi and his group of government officials and scholars and gave a series of lectures on constitutional law

Constitutional law

Constitutional law is the body of law which defines the relationship of different entities within a state, namely, the executive, the legislature and the judiciary....

, which helped to convince Hirobumi that the Prussian-style monarchical constitution was best-suited for Japan. In 1886 Mosse was invited to Japan on a three-year contract as "hired foreigner" to the Japanese government to assist Hirobumi and Inoue Kowashi

Inoue Kowashi

Viscount was a statesman in Meiji period Japan.- Early life :Inoue was born into a samurai family in Higo Province , as the third son of Karō Iida Gongobei. In 1866 Kowashi was adopted by Inoue Shigesaburō, another retainer of the Nagaoka daimyō...

in drafting the Meiji Constitution

Meiji Constitution

The ', known informally as the ', was the organic law of the Japanese empire, in force from November 29, 1890 until May 2, 1947.-Outline:...

. He later worked on other important legal drafts, international agreements, and contracts and served as a cabinet advisor in the Home Ministry

Home Ministry (Japan)

The ' was a Cabinet-level ministry established under the Meiji Constitution that managed the internal affairs of Empire of Japan from 1873-1947...

, assisting Prime Minister Yamagata Aritomo

Yamagata Aritomo

Field Marshal Prince , also known as Yamagata Kyōsuke, was a field marshal in the Imperial Japanese Army and twice Prime Minister of Japan. He is considered one of the architects of the military and political foundations of early modern Japan. Yamagata Aritomo can be seen as the father of Japanese...

in establishing the draft laws and systems for local government. Dozens of Japanese students and military officers also went to Germany in the late 19th century, to study the German military system and receive military training at German army educational facilities and within the ranks of the German, mostly the Prussian army. For example later famous writer Mori Rintarô (Mori Ōgai

Mori Ogai

was a Japanese physician, translator, novelist and poet. is considered his major work.- Early life :Mori was born as Mori Rintarō in Tsuwano, Iwami province . His family were hereditary physicians to the daimyō of the Tsuwano Domain...

), who originally was an army doctor, received tutoring in the German language between 1872 and 1874, which was the primary language for medical education at the time. From 1884 to 1888, Ōgai visited Germany and developed an interest in European literature producing the first translations of the works of Goethe, Schiller, Ibsen, Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen was a Danish author, fairy tale writer, and poet noted for his children's stories. These include "The Steadfast Tin Soldier," "The Snow Queen," "The Little Mermaid," "Thumbelina," "The Little Match Girl," and "The Ugly Duckling."...

, and Gerhart Hauptmann

Gerhart Hauptmann

Gerhart Hauptmann was a German dramatist and novelist who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1912.-Life and work:...

.

Cooling of relations and World War I (1885 to 1920)

At the end of the 19th century, Japanese–German relations cooled due to Germany’s, and in general Europe's, imperialist aspirations in East AsiaEast Asia

East Asia or Eastern Asia is a subregion of Asia that can be defined in either geographical or cultural terms...

. After the conclusion of the First Sino-Japanese War

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War was fought between Qing Dynasty China and Meiji Japan, primarily over control of Korea...

in April 1895, the Treaty of Shimonoseki

Treaty of Shimonoseki

The Treaty of Shimonoseki , known as the Treaty of Maguan in China, was signed at the Shunpanrō hall on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing Empire of China, ending the First Sino-Japanese War. The peace conference took place from March 20 to April 17, 1895...

was signed, which included several territorial cessions from China to Japan, most importantly Taiwan

Taiwan

Taiwan , also known, especially in the past, as Formosa , is the largest island of the same-named island group of East Asia in the western Pacific Ocean and located off the southeastern coast of mainland China. The island forms over 99% of the current territory of the Republic of China following...

and the eastern portion of the bay of the Liaodong Peninsula including Port Arthur

Lüshunkou

Lüshunkou is a district in the municipality of Dalian, Liaoning province, China. Also called Lüshun City or Lüshun Port, it was formerly known as both Port Arthur and Ryojun....

. However, Russia

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

, France

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

and Germany grew wary of an ever-expanding Japanese sphere of influence and wanted to take advantage of China's bad situation by expanding their own colonial possessions instead. The frictions culminated in the so-called "Triple Intervention

Triple Intervention

The was a diplomatic intervention by Russia, Germany, and France on 23 April 1895 over the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki signed between Japan and Qing dynasty China that ended the First Sino-Japanese War.-Treaty of Shimonoseki:...