History of Dublin

Encyclopedia

.png)

City

A city is a relatively large and permanent settlement. Although there is no agreement on how a city is distinguished from a town within general English language meanings, many cities have a particular administrative, legal, or historical status based on local law.For example, in the U.S...

of Dublin can trace its origin back more than 1,000 years, and for much of this time it has been Ireland's

Ireland

Ireland is an island to the northwest of continental Europe. It is the third-largest island in Europe and the twentieth-largest island on Earth...

principal city and the cultural

Culture

Culture is a term that has many different inter-related meanings. For example, in 1952, Alfred Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn compiled a list of 164 definitions of "culture" in Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions...

, education

Education

Education in its broadest, general sense is the means through which the aims and habits of a group of people lives on from one generation to the next. Generally, it occurs through any experience that has a formative effect on the way one thinks, feels, or acts...

al and industrial

Industry

Industry refers to the production of an economic good or service within an economy.-Industrial sectors:There are four key industrial economic sectors: the primary sector, largely raw material extraction industries such as mining and farming; the secondary sector, involving refining, construction,...

centre of the island.

Founding and early history

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy , was a Roman citizen of Egypt who wrote in Greek. He was a mathematician, astronomer, geographer, astrologer, and poet of a single epigram in the Greek Anthology. He lived in Egypt under Roman rule, and is believed to have been born in the town of Ptolemais Hermiou in the...

, the Egyptian-Greek astronomer and cartographer, around the year A.D. 140, who refers to a settlement called Eblana

Eblana

Eblana is the name of an ancient Irish settlement believed by some to have occupied the same site as the modern city of Dublin, to the extent that 19th-century scholarly writers such as Louis Agassiz used Eblana as a Latin equivalent for Dublin...

. This would seem to give Dublin a just claim to nearly two thousand years of antiquity, as the settlement must have existed a considerable time before Ptolemy became aware of it. Recently, however, doubt has been cast on the identification of Eblana with Dublin, and the similarity of the two names is now thought to be coincidental.

It is now thought that the Viking settlement was preceded by a Christian ecclesiastical settlement known as Duiblinn, from which Dyflin took its name. Beginning in the 9th and 10th century, there were two settlements where the modern city stands. The Viking

Viking

The term Viking is customarily used to refer to the Norse explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided, traded, explored and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th century.These Norsemen used their famed longships to...

settlement of about http://www.nalanda.nitc.ac.in/resources/english/etext-project/history/ireland/book-2chapter2.html 841 was known as Dyflin, from the Irish

Irish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

Duiblinn (or "Black Pool", referring to a dark tidal pool where the River Poddle

River Poddle

The River Poddle , is one of the best known of the more than a hundred watercourses of Dublin. It is the source of the name "Dublin", the city being named after a pool that was once on its course...

entered the Liffey

River Liffey

The Liffey is a river in Ireland, which flows through the centre of Dublin. Its major tributaries include the River Dodder, the River Poddle and the River Camac. The river supplies much of Dublin's water, and a range of recreational opportunities.-Name:The river was previously named An Ruirthech,...

on the site of the Castle Gardens at the rear of Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle off Dame Street, Dublin, Ireland, was until 1922 the fortified seat of British rule in Ireland, and is now a major Irish government complex. Most of it dates from the 18th century, though a castle has stood on the site since the days of King John, the first Lord of Ireland...

), and a Gaelic

Celt

The Celts were a diverse group of tribal societies in Iron Age and Roman-era Europe who spoke Celtic languages.The earliest archaeological culture commonly accepted as Celtic, or rather Proto-Celtic, was the central European Hallstatt culture , named for the rich grave finds in Hallstatt, Austria....

settlement, Áth Cliath ("ford of hurdles") was further up river, at the present day Father Mathew Bridge at the bottom of Church Street. The Celtic settlement's name is still used as the Irish name of the modern city, though the first written evidence of it is found in the Annals of Ulster

Annals of Ulster

The Annals of Ulster are annals of medieval Ireland. The entries span the years between AD 431 to AD 1540. The entries up to AD 1489 were compiled in the late 15th century by the scribe Ruaidhrí Ó Luinín, under his patron Cathal Óg Mac Maghnusa on the island of Belle Isle on Lough Erne in the...

of 1368. The modern English name came from the Viking settlement of Dyflin, which derived its name from the Irish Duiblinn. The Vikings, or Ostmen as they called themselves, ruled Dublin for almost three centuries, though they were expelled in 902 only to return in 917 and notwithstanding their defeat by the Irish High King Brian Boru

Brian Boru

Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig, , , was an Irish king who ended the domination of the High Kingship of Ireland by the Uí Néill. Building on the achievements of his father, Cennétig mac Lorcain, and especially his elder brother, Mathgamain, Brian first made himself King of Munster, then subjugated...

at the battle of Clontarf

Battle of Clontarf

The Battle of Clontarf took place on 23 April 1014 between the forces of Brian Boru and the forces led by the King of Leinster, Máel Mórda mac Murchada: composed mainly of his own men, Viking mercenaries from Dublin and the Orkney Islands led by his cousin Sigtrygg, as well as the one rebellious...

in 1014. From that date, the Danes were a minor political force in Ireland, firmly opting for a commercial life. Viking rule of Dublin would end completely in 1171 when the city was captured by King Dermot MacMurrough

Dermot MacMurrough

Diarmait Mac Murchada , anglicized as Dermot MacMurrough or Dermod MacMurrough , was a King of Leinster in Ireland. In 1167, he was deprived of his kingdom by the High King of Ireland - Turlough Mór O'Connor...

of Leinster

Leinster

Leinster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the east of Ireland. It comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Mide, Osraige and Leinster. Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the historic fifths of Leinster and Mide gradually merged, mainly due to the impact of the Pale, which straddled...

, with the aid of Anglo-Norman

Anglo-Norman

The Anglo-Normans were mainly the descendants of the Normans who ruled England following the Norman conquest by William the Conqueror in 1066. A small number of Normans were already settled in England prior to the conquest...

mercenaries. An attempt was made by the last Norse King of Dublin, Hasculf Thorgillsson

Hasculf Thorgillsson

Ascall mac Ragnaill, also Hasculf Rognvaldsson , but surnamed Mac Torcaill or Thorgillsson, was the last Norse King of Dublin. His fortress is believed to have stood on the modern site of Dublin Castle. After the 1171 invasion under Strongbow, Ascall's kingdom was captured by Cambro-Norman...

, to recapture the city with an army he raised among his relations in the Scottish Highlands, where he was forced to flee after the city was taken, but the attempted reconquest failed and Thorgillsson was killed.

The Thingmote was a raised mound, 40 feet (12.2 m) high and 240 feet (73.2 m) in circumference, where the Norsemen

Norsemen

Norsemen is used to refer to the group of people as a whole who spoke what is now called the Old Norse language belonging to the North Germanic branch of Indo-European languages, especially Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese, Swedish and Danish in their earlier forms.The meaning of Norseman was "people...

assembled and made their laws. It stood on the south of the river, adjacent to Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle off Dame Street, Dublin, Ireland, was until 1922 the fortified seat of British rule in Ireland, and is now a major Irish government complex. Most of it dates from the 18th century, though a castle has stood on the site since the days of King John, the first Lord of Ireland...

, until 1685. Viking Dublin had a large slave market

Slavery in medieval Europe

Slavery in early medieval Europe was relatively common. It was widespread at the end of antiquity. The etymology of the word slave comes from this period, the word sklabos meaning Slav. Slavery declined in the Middle Ages in most parts of Europe as serfdom slowly rose, but it never completely...

. Thrall

Thrall

Thrall was the term for a serf or unfree servant in Scandinavian culture during the Viking Age.Thralls were the lowest in the social order and usually provided unskilled labor during the Viking era.-Etymology:...

s were captured and sold, not only by the Norse but also by warring Irish chiefs.

Dublin celebrated its millennium in 1988 with the slogan Dublin's great in '88'. The city is far older than that, but in that year, the Norse King Glun Iarainn recognised Máel Sechnaill II

Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill

Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill , also called Máel Sechnaill Mór, Máel Sechnaill II, anglicized Malachy II, was King of Mide and High King of Ireland...

(Máel Sechnaill Mór), High King of Ireland, and agreed to pay taxes and accept Brehon Law

Brehon Laws

Early Irish law refers to the statutes that governed everyday life and politics in Early Medieval Ireland. They were partially eclipsed by the Norman invasion of 1169, but underwent a resurgence in the 13th century, and survived into Early Modern Ireland in parallel with English law over the...

. That date was celebrated, but might not be accurate: in 989 (not 988), Mael Seachlainn laid siege

Siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city or fortress with the intent of conquering by attrition or assault. The term derives from sedere, Latin for "to sit". Generally speaking, siege warfare is a form of constant, low intensity conflict characterized by one party holding a strong, static...

to the city for 20 days and captured it. This was not his first attack on the city.

Dublin became the centre of English power in Ireland after the Norman invasion

Norman Invasion of Ireland

The Norman invasion of Ireland was a two-stage process, which began on 1 May 1169 when a force of loosely associated Norman knights landed near Bannow, County Wexford...

of the southern half of Ireland (Munster

Munster

Munster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the south of Ireland. In Ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial purposes...

and Leinster

Leinster

Leinster is one of the Provinces of Ireland situated in the east of Ireland. It comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Mide, Osraige and Leinster. Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the historic fifths of Leinster and Mide gradually merged, mainly due to the impact of the Pale, which straddled...

) in 1169-71, replacing Tara in Meath

County Meath

County Meath is a county in Ireland. It is part of the Mid-East Region and is also located in the province of Leinster. It is named after the ancient Kingdom of Mide . Meath County Council is the local authority for the county...

— seat of the Gaelic High Kings of Ireland

High King of Ireland

The High Kings of Ireland were sometimes historical and sometimes legendary figures who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over the whole of Ireland. Medieval and early modern Irish literature portrays an almost unbroken sequence of High Kings, ruling from Tara over a hierarchy of...

— as the focal point of Ireland's polity. On 15 May 1192 Dublin's first written Charter of Liberties was granted by John

John of England

John , also known as John Lackland , was King of England from 6 April 1199 until his death...

, Lord of Ireland

Lordship of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland refers to that part of Ireland that was under the rule of the king of England, styled Lord of Ireland, between 1177 and 1541. It was created in the wake of the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169–71 and was succeeded by the Kingdom of Ireland...

, and was addressed to all his "French, English, Irish and Welsh subjects and friends". On 15 June 1229 his son Henry

Henry III of England

Henry III was the son and successor of John as King of England, reigning for 56 years from 1216 until his death. His contemporaries knew him as Henry of Winchester. He was the first child king in England since the reign of Æthelred the Unready...

granted the citizens the right to elect a Mayor

Mayor

In many countries, a Mayor is the highest ranking officer in the municipal government of a town or a large urban city....

who was to be assisted by two provosts. By 1400, however, many of the Anglo-Norman conquerors were absorbed into the Irish culture, adopting the Irish language and customs, leaving only a small area of Leinster around Dublin, known as the Pale

The Pale

The Pale or the English Pale , was the part of Ireland that was directly under the control of the English government in the late Middle Ages. It had reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast stretching from Dalkey, south of Dublin, to the garrison town of Dundalk...

, under direct English control.

Late Medieval Dublin

Norsemen

Norsemen is used to refer to the group of people as a whole who spoke what is now called the Old Norse language belonging to the North Germanic branch of Indo-European languages, especially Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese, Swedish and Danish in their earlier forms.The meaning of Norseman was "people...

inhabitants left the old city, which was on the south side of the river Liffey and built their own settlement on the north side, known as Ostmantown or "Oxmantown". Dublin became the capital of the English Lordship of Ireland

Lordship of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland refers to that part of Ireland that was under the rule of the king of England, styled Lord of Ireland, between 1177 and 1541. It was created in the wake of the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169–71 and was succeeded by the Kingdom of Ireland...

from 1171 onwards and was peopled extensively with settlers from England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

and Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

. The rural area around the city, as far north as Drogheda

Drogheda

Drogheda is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, 56 km north of Dublin. It is the last bridging point on the River Boyne before it enters the Irish Sea....

, also saw extensive English settlement. In the 14th century, this area was fortified against the increasingly assertive Native Irish – becoming known as The Pale

The Pale

The Pale or the English Pale , was the part of Ireland that was directly under the control of the English government in the late Middle Ages. It had reduced by the late 15th century to an area along the east coast stretching from Dalkey, south of Dublin, to the garrison town of Dundalk...

. In Dublin itself, English rule was centred on Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle off Dame Street, Dublin, Ireland, was until 1922 the fortified seat of British rule in Ireland, and is now a major Irish government complex. Most of it dates from the 18th century, though a castle has stood on the site since the days of King John, the first Lord of Ireland...

. The city was also the main seat of the Parliament of Ireland

Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland was a legislature that existed in Dublin from 1297 until 1800. In its early mediaeval period during the Lordship of Ireland it consisted of either two or three chambers: the House of Commons, elected by a very restricted suffrage, the House of Lords in which the lords...

from 1297, which was composed of landowners and merchants. Important buildings that date from this time include St Patrick's Cathedral

St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin

Saint Patrick's Cathedral , or more formally, the Cathedral of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St Patrick is a cathedral of the Church of Ireland in Dublin, Ireland which was founded in 1191. The Church has designated it as The National Cathedral of Ireland...

, Christchurch Cathedral and St. Audoen's Church

St. Audoen's Church

St. Audoen's Church is the church of the parish of St. Audoen in the Church of Ireland, located south of the River Liffey at Cornmarket in Dublin, Ireland. This was close to the centre of the medieval city. The parish is in the Diocese of Dublin and Glendalough. St. Audoen's is the oldest parish...

, all of which are within a kilometre of each other.

Ranelagh

Ranelagh is a residential area and urban village on the south side of Dublin, Ireland. It is in the postal district of Dublin 6. It is in the local government electoral area of Rathmines and the Dáil Constituency of Dublin South-East.-History:...

, where, in 1209, five hundred recent settlers from Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

had been massacred by the O'Toole clan during an outing outside the city limits. Every year on "Black Monday", the Dublin citizens would march out of the city to the spot where the atrocity had happened and raise a black banner in the direction of the mountains to challenge the Irish to battle in a gesture of symbolic defiance. This was still so dangerous that, until the 17th century, the participants had to be guarded by the city militia and a stockade against "the mountain enemy".

Medieval Dublin was a tightly knit place of around 5,000 to 10,000 people, intimate enough for every newly married citizen to be escorted by the mayor to the city bullring to kiss the enclosure for good luck. It was also very small in area, an enclave hugging the south side of the Liffey of no more than three square kilometres. Outside the city walls were suburbs such as the Liberties

The Liberties

The Liberties of Dublin, Ireland were jurisdictions that existed since the arrival of the Anglo-Normans in the 12th century. They were town lands united to the city, but still preserving their own jurisdiction. The most important of these liberties were the Liberty of St...

, on the lands of the Archbishop of Dublin

Archbishop of Dublin (Roman Catholic)

The Archbishop of Dublin is the title of the senior cleric who presides over the Archdiocese of Dublin. The Church of Ireland has a similar role, heading the United Dioceses of Dublin and Glendalough. In both cases, the Archbishop is also Primate of Ireland...

, and Irishtown

Irishtown

Irishtown may refer to:* Irishtown, Dublin, Ireland* Irishtown Stadium* Irishtown, County Antrim, a townland in County Antrim, Northern Ireland* Irishtown, County Mayo, a village in County Mayo, Ireland* Irishtown, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada...

, where Gaelic Irish were supposed to live, having been expelled from the city proper by a 15th century law. Although the native Irish were not supposed to live in the city and its environs, many did so and by the 16th century, English accounts complain that Irish Gaelic

Irish language

Irish , also known as Irish Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language by a minority of Irish people, as well as being a second language of a larger proportion of...

was starting to rival English as the everyday language of the Pale.

Life in Medieval Dublin was very precarious. In 1348, the city was hit by the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

– a lethal bubonic plague

Bubonic plague

Plague is a deadly infectious disease that is caused by the enterobacteria Yersinia pestis, named after the French-Swiss bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin. Primarily carried by rodents and spread to humans via fleas, the disease is notorious throughout history, due to the unrivaled scale of death...

that ravaged Europe in the mid-14th century. In Dublin, victims of the disease were buried in mass graves in an area still known as "Blackpitts".(Archaeological excavations in the past ten years have found evidence of a tanning industry in this area, so the name "Blackpitts" may refer to the tanning pits which stained the surrounding area a deep dark colour). The plague recurred regularly in city until its last major outbreak in 1649.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the city paid protection money or "black rent" to the neighbouring Irish clans to avoid their predatory raids. In 1315, a Scottish army under Edward the Bruce burned the city's suburbs. As English interest in maintaining their Irish colony waned, the defence of Dublin from the surrounding Irish was left to the Fitzgerald Earls of Kildare, who dominated Irish politics until the 16th century. However, this dynasty often pursued their own agenda. In 1487, during the English Wars of the Roses

Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses were a series of dynastic civil wars for the throne of England fought between supporters of two rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet: the houses of Lancaster and York...

, the Fitzgeralds occupied the city with the aid of troops from Burgundy

Duchy of Burgundy

The Duchy of Burgundy , was heir to an ancient and prestigious reputation and a large division of the lands of the Second Kingdom of Burgundy and in its own right was one of the geographically larger ducal territories in the emergence of Early Modern Europe from Medieval Europe.Even in that...

and proclaimed the Yorkist Lambert Simnel

Lambert Simnel

Lambert Simnel was a pretender to the throne of England. His claim to be the Earl of Warwick in 1487 threatened the newly established reign of King Henry VII .-Early life:...

to be King of England. In 1537, the same dynasty, led by Silken Thomas, who was angry at the imprisonment of Garret Fitzgerald, Earl of Kildare, besieged Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle off Dame Street, Dublin, Ireland, was until 1922 the fortified seat of British rule in Ireland, and is now a major Irish government complex. Most of it dates from the 18th century, though a castle has stood on the site since the days of King John, the first Lord of Ireland...

. Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

sent a large army to destroy the Fitzgeralds and replace them with English administrators. This was the beginning of a much closer, though not always happy, relationship between Dublin and the English Crown.

British Dublin

Tudor dynasty

The Tudor dynasty or House of Tudor was a European royal house of Welsh origin that ruled the Kingdom of England and its realms, including the Lordship of Ireland, later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1485 until 1603. Its first monarch was Henry Tudor, a descendant through his mother of a legitimised...

. While the Old English

Old English (Ireland)

The Old English were the descendants of the settlers who came to Ireland from Wales, Normandy, and England after the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169–71. Many of the Old English became assimilated into Irish society over the centuries...

community of Dublin and the Pale were happy with the conquest and disarmament of the native Irish, they were deeply alienated by the Protestant reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

that had taken place in England, being almost all Roman Catholics. In addition, they were angered by being forced to pay for the English garrisons of the country through an extra-parliamentary tax known as "cess

Cess

The term cess generally means a tax. It is a term formerly more particularly applied to local taxation, and was the official term used in Ireland when it was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland; otherwise, it has been superseded by "rate"...

". Several Dubliners were executed for taking part in the Second Desmond Rebellion

Second Desmond Rebellion

The Second Desmond rebellion was the more widespread and bloody of the two Desmond Rebellions launched by the FitzGerald dynasty of Desmond in Munster, Ireland, against English rule in Ireland...

in the 1580s. The Mayoress of Dublin, Margaret Ball

Margaret Ball

Blessed Margaret Ball was born Margaret Birmingham near Skryne in County Meath, and died of deprivation in the dungeons of Dublin Castle. She was the wife of the Mayor of Dublin in 1553. She was beatified in 1992.-Early life:...

died in captivity in Dublin Castle for her Catholic sympathies in 1584 and a Catholic Archbishop, Dermot O'Hurley

Dermot O'Hurley

Blessed Dermot O'Hurley - in Irish Diarmaid Ó hUrthuile - was a Roman Catholic Archbishop of Cashel during the reign of Elizabeth I who was put to death for treason...

was hanged outside the city walls in the same year.

In 1592, Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

opened Trinity College Dublin (located at that time outside the city on its eastern side) as a Protestant University for the Irish gentry. However, the important Dublin families spurned it and sent their sons instead to Catholic Universities

Irish College

Irish Colleges is the collective name used for approximately 34 centres of education for Irish Catholic clergy and lay people opened on continental Europe in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. The Colleges were set up to educate Roman Catholics from Ireland in their own religion following the...

on continental Europe.

The Dublin community's discontent was deepened by the events of the Nine Years War of the 1590s, when English soldiers were required by decree to be housed by the townsmen of Dublin and they spread disease and forced up the price of food. The wounded lay in stalls in the streets, in the absence of a proper hospital. To compound disaffection in the city, in 1597, the English Army's gunpowder store in Winetavern Street exploded accidentally

Dublin Gunpowder Disaster

The Dublin Gunpowder Disaster was a devastating explosion that took place on the quays of Dublin on March 11, 1597. The explosion demolished as many as forty houses, and left dozens of others badly damaged. The disaster claimed the lives of 126 people, as well as inflicting countless injuries.The...

, killing nearly 200 Dubliners. It should be noted, however, that the Pale community, however dissatisfied they were with English government, remained hostile to the Gaelic Irish led by Hugh O'Neill.

As a result of these tensions, the English authorities came to see Dubliners as unreliable and encouraged the settlement

Plantations of Ireland

Plantations in 16th and 17th century Ireland were the confiscation of land by the English crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from England and the Scottish Lowlands....

there of Protestants from England. These "New English" became the basis of the English administration in Ireland until the 19th century.

Protestants became a majority in Dublin in the 1640s, when thousands of them fled there to escape the Irish Rebellion of 1641

Irish Rebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 began as an attempted coup d'état by Irish Catholic gentry, who tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland to force concessions for the Catholics living under English rule...

. When the city was subsequently threatened by Irish Catholic forces, the Catholic Dubliners were expelled from the city by its English garrison. In the 1640s, the city was besieged twice during the Irish Confederate Wars

Irish Confederate Wars

This article is concerned with the military history of Ireland from 1641-53. For the political context of this conflict, see Confederate Ireland....

, in 1646 and 1649. However on both occasions the attackers were driven off before a lengthy siege could develop. In 1649, on the second of these occasions, a mixed force of Irish Confederates and English Royalists were routed by Dublin's English Parliamentarian garrison in the battle of Rathmines

Battle of Rathmines

The Battle of Rathmines was fought in and around what is now the Dublin suburb of Rathmines in August 1649, during the Irish Confederate Wars, the Irish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

, fought on the city's southern outskirts.

In the 1650s after the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland refers to the conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell landed in Ireland with his New Model Army on behalf of England's Rump Parliament in 1649...

, Catholics were banned from dwelling within the city limits under the vengeful Cromwellian settlement

Act for the Settlement of Ireland 1652

The Act for the Settlement of Ireland imposed penalties including death and land confiscation against participants and bystanders of the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and subsequent unrest.-Background:...

but this law was not strictly enforced. Ultimately, this religious discrimination led to the Old English

Old English (Ireland)

The Old English were the descendants of the settlers who came to Ireland from Wales, Normandy, and England after the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169–71. Many of the Old English became assimilated into Irish society over the centuries...

community abandoning their English roots and coming to see themselves as part of the native Irish community.

By the end of the seventeenth century, Dublin was the capital of the English run Kingdom of Ireland

Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland refers to the country of Ireland in the period between the proclamation of Henry VIII as King of Ireland by the Crown of Ireland Act 1542 and the Act of Union in 1800. It replaced the Lordship of Ireland, which had been created in 1171...

– ruled by the Protestant New English minority. Dublin (along with parts of Ulster

Ulster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

) was the only part of Ireland in 1700 where Protestants were a majority. In the next century it became larger, more peaceful and prosperous than at any time in its previous history.

From a Medieval to a Georgian city

See Also Georgian DublinGeorgian Dublin

Georgian Dublin is a phrase used in the History of Dublin that has two interwoven meanings,# to describe a historic period in the development of the city of Dublin, Ireland, from 1714 to the death in 1830 of King George IV...

Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy, usually known in Ireland simply as the Ascendancy, is a phrase used when referring to the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland by a minority of great landowners, Protestant clergy, and professionals, all members of the Established Church during the 17th...

was thriving, and the city expanded rapidly from the 17th century onward. By 1700, the population had surpassed 60,000, making it the second largest city, after London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

, in the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

. Under the Restoration

English Restoration

The Restoration of the English monarchy began in 1660 when the English, Scottish and Irish monarchies were all restored under Charles II after the Interregnum that followed the Wars of the Three Kingdoms...

, Ormonde

James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde

James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde PC was an Irish statesman and soldier. He was the second of the Kilcash branch of the family to inherit the earldom. He was the friend of Thomas Wentworth, 1st Earl of Strafford, who appointeed him commander of the Cavalier forces in Ireland. From 1641 to 1647, he...

, the then Lord Deputy of Ireland

Lord Deputy of Ireland

The Lord Deputy was the King's representative and head of the Irish executive under English rule, during the Lordship of Ireland and later the Kingdom of Ireland...

made the first step toward modernising Dublin by ordering that the houses along the river Liffey

River Liffey

The Liffey is a river in Ireland, which flows through the centre of Dublin. Its major tributaries include the River Dodder, the River Poddle and the River Camac. The river supplies much of Dublin's water, and a range of recreational opportunities.-Name:The river was previously named An Ruirthech,...

had to face the river and have high quality frontages. This was in contrast to the earlier period, when Dublin faced away from the river, often using it as a rubbish dump.

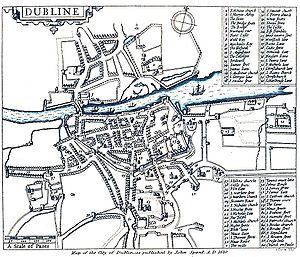

Dublin started the 18th century as, in terms of street layout, a medieval city akin to Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

. In the course of the eighteenth century (as Paris would in the nineteenth century) it underwent a major rebuilding, with the Wide Streets Commission

Wide Streets Commission

The Wide Streets Commission was established by an Act of Parliament in 1757, at the request of Dublin Corporation, as a body to govern standards on the layout of streets, bridges, buildings and other architectural considerations in Dublin...

demolishing many of the narrow medieval streets and replacing them with large Georgian streets. Among the famous streets to appear following this redesign were Sackville Street (now called O'Connell Street

O'Connell Street

O'Connell Street is Dublin's main thoroughfare. It measures 49 m in width at its southern end, 46 m at the north, and is 500 m in length...

), Dame Street

Dame Street

Dame Street is a large thoroughfare in Dublin, Ireland. The street is the location of many banks such as AIB, Ulster Bank and the Central Bank of Ireland. It is close to Ireland's oldest university, Trinity College, Dublin, founded in 1592, the entrance to which is a popular meeting spot.During...

, Westmoreland Street and D'Olier Street, all built following the demolition of narrow medieval streets and their amalgamation. Five major Georgian squares were also laid out; Rutland Square (now called Parnell Square) and Mountjoy Square on the northside, and Merrion Square, Fitzwilliam Square and Saint Stephen's Green, all on the south of the River Liffey

River Liffey

The Liffey is a river in Ireland, which flows through the centre of Dublin. Its major tributaries include the River Dodder, the River Poddle and the River Camac. The river supplies much of Dublin's water, and a range of recreational opportunities.-Name:The river was previously named An Ruirthech,...

. Though initially the most prosperous residences of peers were located on the northside, in places like Henrietta Street

Henrietta Street

Henrietta Street is a Dublin street, to the north of Bolton Street on the north side of the city, first laid out and developed by Luke Gardiner during the 1720s. A very wide street relative to streets in other 18th-century cities, it includes a number of very large red-brick city palaces of...

and Rutland Square, the decision of the Earl of Kildare (Ireland's premier peer, later made Duke of Leinster), to build his new townhouse, Kildare House (later renamed Leinster House

Leinster House

Leinster House is the name of the building housing the Oireachtas, the national parliament of Ireland.Leinster House was originally the ducal palace of the Dukes of Leinster. Since 1922, it is a complex of buildings, of which the former ducal palace is the core, which house Oireachtas Éireann, its...

after he was made Duke of Leinster

Duke of Leinster

Duke of Leinster is a title in the Peerage of Ireland and the premier dukedom in that peerage. The title refers to Leinster, but unlike the province the title is pronounced "Lin-ster"...

) on the southside, led to a rush from peers to build new houses on the southside, in or around the three major southern squares.

In 1745 Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

, then Dean of St.Patrick's

St. Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin

Saint Patrick's Cathedral , or more formally, the Cathedral of the Blessed Virgin Mary and St Patrick is a cathedral of the Church of Ireland in Dublin, Ireland which was founded in 1191. The Church has designated it as The National Cathedral of Ireland...

, bequeathed his entire estate to found a hospital for "fools and mad" and on August 8, 1746, a Royal Charter was granted to St Patricks Hospital by George II

George II of Great Britain

George II was King of Great Britain and Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Archtreasurer and Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire from 11 June 1727 until his death.George was the last British monarch born outside Great Britain. He was born and brought up in Northern Germany...

. Crucially, following his experiences as a governor of the Bedlam

Bethlem Royal Hospital

The Bethlem Royal Hospital is a psychiatric hospital located in London, United Kingdom and part of the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Although no longer based at its original location, it is recognised as the world's first and oldest institution to specialise in mental illnesses....

hospital in London, Swift intended the hospital to be designed around the needs of the patient and left strict instructions on how patients were to be treated. The first psychiatric hospital to be built in Ireland, it is one of the oldest in the world and still flourishes today as one of the largest and most comprehensive in the country.

For all its Enlightenment

Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

sophistication in fields such as architecture and music (Handel's "Messiah"

Messiah (Handel)

Messiah is an English-language oratorio composed in 1741 by George Frideric Handel, with a scriptural text compiled by Charles Jennens from the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer. It was first performed in Dublin on 13 April 1742, and received its London premiere nearly a year later...

was first performed there in Fishamble street), 18th century Dublin remained decidedly rough around the edges. Its slum population rapidly increased - fed by the mounting rural migration to the city - housed mostly in the north and south-west quarters of the city. Rival gangs known as the "Liberty Boys" - mostly weavers from the Liberties

The Liberties

The Liberties of Dublin, Ireland were jurisdictions that existed since the arrival of the Anglo-Normans in the 12th century. They were town lands united to the city, but still preserving their own jurisdiction. The most important of these liberties were the Liberty of St...

- and the "Ormonde Boys" - butchers from Ormonde quay on the northside - fought bloody street battles with each other, sometimes heavily armed and with numerous fatalities. It was also common for the Dublin crowds to hold violent demonstrations outside the Irish Parliament when the members passed unpopular laws.

One of the effects of continued rural migration to Dublin was that its demographic balance was again altered, Catholics becoming the majority in the city again in the late 18th century.

Rebellion, Union and Catholic emancipation

Until 1800 the city housed an independent (though still exclusively Anglican) Irish Parliament, and as mentioned it was during this period that much of the great GeorgianGeorgian architecture

Georgian architecture is the name given in most English-speaking countries to the set of architectural styles current between 1720 and 1840. It is eponymous for the first four British monarchs of the House of Hanover—George I of Great Britain, George II of Great Britain, George III of the United...

buildings of Dublin were built. By the late 18th century, Irish Protestants - mostly the descendants of British settlers - had been born in Ireland and saw it as their native country, and the Irish Parliament successfully agitated for increased autonomy and better terms of trade with Britain. From 1778 the Penal Law

Penal Laws (Ireland)

The term Penal Laws in Ireland were a series of laws imposed under English and later British rule that sought to discriminate against Roman Catholics and Protestant dissenters in favour of members of the established Church of Ireland....

started to be repealed, pushed along by liberals such as Henry Grattan

Henry Grattan

Henry Grattan was an Irish politician and member of the Irish House of Commons and a campaigner for legislative freedom for the Irish Parliament in the late 18th century. He opposed the Act of Union 1800 that merged the Kingdoms of Ireland and Great Britain.-Early life:Grattan was born at...

. (See Ireland 1691-1801)

However, under the influence of the American and French revolutions, some Irish radicals went a step further and formed the United Irishmen to create an independent, non-sectarian and democratic republic. United Irish leaders in Dublin included Napper Tandy, Oliver Bond

Oliver Bond

Oliver Bond was an Irish revolutionary, one of the leaders of the Society of United Irishmen in the end of 18th century, which has the objective of ending British rule over Ireland and founding an independent Irish republic.He was born in the parish of St...

and Edward Fitzgerald

Edward Fitzgerald

Edward Fitzgerald may refer to:* Lord Edward FitzGerald , Irish revolutionary*Edward Fitzgerald , Irish* Edward FitzGerald, 7th Duke of Leinster * Edward Fitzgerald...

. Wolfe Tone, the leader of the movement, was also from Dublin. The United Irishmen planned to take Dublin in a street rising in 1798, but their leaders were arrested and the city occupied by a large British military presence shortly before the rebels could assemble. There was some local fighting in the city's outskirts - such as Rathfarnham

Rathfarnham

Rathfarnham or Rathfarnam is a Southside suburb of Dublin, Ireland. It is south of Terenure, east of Templeogue, and is in the postal districts of Dublin 14 and 16. It is within the administrative areas of both Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown and South Dublin County Councils.The area of Rathfarnham...

, but the city itself remained firmly under control during the 1798 rebellion

Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 , also known as the United Irishmen Rebellion , was an uprising in 1798, lasting several months, against British rule in Ireland...

.

The Protestant Ascendancy

Protestant Ascendancy

The Protestant Ascendancy, usually known in Ireland simply as the Ascendancy, is a phrase used when referring to the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland by a minority of great landowners, Protestant clergy, and professionals, all members of the Established Church during the 17th...

was shocked by the events of the 1790s, as was the British government. In response to them, in 1801 under the Irish Act of Union

Act of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 describe two complementary Acts, namely:* the Union with Ireland Act 1800 , an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, and...

, which merged the Kingdom of Ireland with the Kingdom of Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was the formal name of the United Kingdom during the period when what is now the Republic of Ireland formed a part of it....

the Irish Parliament voted itself out of existence and Dublin lost its political status as a capital. Though the city's growth continued, it suffered financially from the loss of parliament and more directly from the loss of the income that would come with the arrival of hundreds of peers and MPs and thousands of servants to the capital for sessions of parliament and the social season of the viceregal court in Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle

Dublin Castle off Dame Street, Dublin, Ireland, was until 1922 the fortified seat of British rule in Ireland, and is now a major Irish government complex. Most of it dates from the 18th century, though a castle has stood on the site since the days of King John, the first Lord of Ireland...

. Within a short few years, many of the finest mansions, including Leinster House, Powerscourt House and Aldborough House, once owned by peers who spent much of their year in the capital, were for sale. Many of the city's once elegant Georgian neighbourhoods rapidly became slums. In 1803, Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet was an Irish nationalist and Republican, orator and rebel leader born in Dublin, Ireland...

, the brother of one of the United Irish leaders launched another one-day rebellion in the city, however, it was put down easily and Emmet himself was hanged, drawn and quartered

Hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered was from 1351 a penalty in England for men convicted of high treason, although the ritual was first recorded during the reigns of King Henry III and his successor, Edward I...

.

In 1829 the wealthier Irish Catholics recovered full citizenship of the United Kingdom. This was partly as a result of agitation by Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell Daniel O'Connell Daniel O'Connell (6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847; often referred to as The Liberator, or The Emancipator, was an Irish political leader in the first half of the 19th century...

, who organised mass rallies for Catholic Emancipation

Catholic Emancipation

Catholic emancipation or Catholic relief was a process in Great Britain and Ireland in the late 18th century and early 19th century which involved reducing and removing many of the restrictions on Roman Catholics which had been introduced by the Act of Uniformity, the Test Acts and the penal laws...

in Dublin among other places. O'Connell also campaigned unsuccessfully for a restoration of Irish legislative autonomy. O'Connell was later elected Lord Mayor of Dublin

Lord Mayor of Dublin

The Lord Mayor of Dublin is the honorific title of the Chairman of Dublin City Council which is the local government body for the city of Dublin, the capital of Ireland. The incumbent is Labour Party Councillor Andrew Montague. The office holder is elected annually by the members of the...

, and is remembered among trade union

Trade union

A trade union, trades union or labor union is an organization of workers that have banded together to achieve common goals such as better working conditions. The trade union, through its leadership, bargains with the employer on behalf of union members and negotiates labour contracts with...

ists in the city to this day for calling on the British army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

to suppress a strike

Strike action

Strike action, also called labour strike, on strike, greve , or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became important during the industrial revolution, when mass labour became...

during his tenure.

Late 19th Century

After Emancipation and with the gradual extension of the right to vote in British politics, Irish nationalists (mainly Catholics) gained control of Dublin's municipal government with the reform of local government in 1840, Daniel O'ConnellDaniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell Daniel O'Connell Daniel O'Connell (6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847; often referred to as The Liberator, or The Emancipator, was an Irish political leader in the first half of the 19th century...

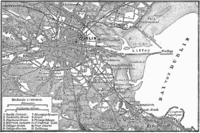

being the first Catholic Mayor in 150 years. Increasing wealth prompted many of Dublin's Protestant and Unionist middle classes to move out of the city proper to new suburbs such as Ballsbridge

Ballsbridge

Ballsbridge is a suburb of Dublin, Ireland, named for the bridge spanning the River Dodder on the south side of the city. The sign on the bridge still proclaims it as "Ball's Bridge" in recognition of the fact that the original bridge in this location was built and owned by a Mr...

, Rathmines

Rathmines

Rathmines is a suburb on the southside of Dublin, about 3 kilometres south of the city centre. It effectively begins at the south side of the Grand Canal and stretches along the Rathmines Road as far as Rathgar to the south, Ranelagh to the east and Harold's Cross to the west.Rathmines has...

and Rathgar

Rathgar

Rathgar is a suburb of Dublin, Ireland, lying about 3 kilometres south of the city centre.-Amenities:Rathgar is largely a quiet suburb with good amenities, including primary and secondary schools, nursing homes, child-care and sports facilities, and good public transport to the city centre...

- which are still distinguished by their graceful Victorian architecture

Victorian architecture

The term Victorian architecture refers collectively to several architectural styles employed predominantly during the middle and late 19th century. The period that it indicates may slightly overlap the actual reign, 20 June 1837 – 22 January 1901, of Queen Victoria. This represents the British and...

. A new railway also connected Dublin with the middle class suburb of Dún Laoghaire

Dún Laoghaire

Dún Laoghaire or Dún Laoire , sometimes anglicised as "Dunleary" , is a suburban seaside town in County Dublin, Ireland, about twelve kilometres south of Dublin city centre. It is the county town of Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown County and a major port of entry from Great Britain...

, renamed Kingstown in 1821.

Dublin, unlike Belfast

Belfast

Belfast is the capital of and largest city in Northern Ireland. By population, it is the 14th biggest city in the United Kingdom and second biggest on the island of Ireland . It is the seat of the devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly...

in the north, did not experience the full effect of the industrial revolution

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

and as a result, the number of unskilled unemployed was always high in the city. Industries like the Guinness

Guinness

Guinness is a popular Irish dry stout that originated in the brewery of Arthur Guinness at St. James's Gate, Dublin. Guinness is directly descended from the porter style that originated in London in the early 18th century and is one of the most successful beer brands worldwide, brewed in almost...

brewery, Jameson

Jameson Irish Whiskey

Jameson is a single distillery Irish whiskey produced by a division of the French distiller Pernod Ricard. Jameson is similar in its adherence to the single distillery principle to the single malt tradition, but Jameson combines malted barley with unmalted or "green" barley...

Distillery, and Jacob's

Jacob's

Jacob's is a brand name for several lines of biscuits and crackers. The brand name in the Republic of Ireland is owned by Jacob Fruitfield Food Group and in the United Kingdom it is owned under license by United Biscuits.-History:...

biscuit factory provided the most stable employment. New working class

Working class

Working class is a term used in the social sciences and in ordinary conversation to describe those employed in lower tier jobs , often extending to those in unemployment or otherwise possessing below-average incomes...

suburbs grew up in Kilmainham

Kilmainham

Kilmainham is a suburb of Dublin south of the River Liffey and west of the city centre, in the Dublin 8 postal district.-History:In the Viking era, the monastery was home to the first Norse base in Ireland....

and Inchicore

Inchicore

-Location and access:Located five kilometres due west of the city centre, Inchicore lies south of the River Liffey, west of Kilmainham, north of Drimnagh and east of Ballyfermot. The majority of Inchicore is in the Dublin 8 postal district...

around them. Another major employer was the Dublin Tramways system, run by a private company - the Dublin United Tramway Company

Dublin United Transport Company

The Dublin United Transport Company operated trams and buses in Dublin, Ireland until 1945. Following legislation in the Oireachtas , the DUTC and the Great Southern Railways were vested in the newly formed Coras Iompair Éireann in 1945.-Formation:The DUTC was formed by the merging of several of...

. By 1900 Belfast had a larger population than Dublin, though it is smaller today.

In 1867, the Irish Republican Brotherhood

Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland during the second half of the 19th century and the start of the 20th century...

or 'Fenians', attempted an insurrection aimed at the ending of British rule in Ireland. However, the rebellion was badly organised, lacked public support and failed to get off the ground. In Dublin, fighting was confined to the suburb of Tallaght

Tallaght

Tallaght is the largest town, and county town, of South Dublin County, Ireland. The village area, dating from at least the 17th century, held one of the earliest settlements known in the southern part of the island, and one of medieval Ireland's more important monastic centres.Up to the 1960s...

, where several hundred Fenians made a failed attack on the Royal Irish Constabulary

Royal Irish Constabulary

The armed Royal Irish Constabulary was Ireland's major police force for most of the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries. A separate civic police force, the unarmed Dublin Metropolitan Police controlled the capital, and the cities of Derry and Belfast, originally with their own police...

barracks. The failure of this rebellion did not mark the end of nationalist violence however. In 1882, an offshoot of the Fenians, who called themselves the Irish National Invincibles

Irish National Invincibles

The Irish National Invincibles, usually known as "The Invincibles" were a radical splinter group of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and leading representatives of the Land League movement, both of Ireland and Britain...

, assassinated two prominent members of the British administration with surgical knives in the Phoenix Park

Phoenix Park

Phoenix Park is an urban park in Dublin, Ireland, lying 2–4 km west of the city centre, north of the River Liffey. Its 16 km perimeter wall encloses , one of the largest walled city parks in Europe. It includes large areas of grassland and tree-lined avenues, and since the seventeenth...

. The incident became known as the Phoenix Park murders

Phoenix Park Murders

The Phoenix Park Murders were the fatal stabbings on 6 May 1882 in the Phoenix Park in Dublin of Lord Frederick Cavendish and Thomas Henry Burke. Cavendish was the newly appointed Chief Secretary for Ireland, and Burke was the Permanent Undersecretary, the most senior Irish civil servant...

and was universally condemned.

Monto

See Also MontoMonto

Monto was the nickname for a one-time notorious red light district in Dublin, the capital of Ireland...

Act of Union 1800

The Acts of Union 1800 describe two complementary Acts, namely:* the Union with Ireland Act 1800 , an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain, and...

, it grew steadily in size throughout the 19th century. By 1900, the population was over 400,000. While the city grew, so did its level of poverty. Though described as "the second city of the (British) Empire", its large number of tenements became infamous, being mentioned by writers such as James Joyce

James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce was an Irish novelist and poet, considered to be one of the most influential writers in the modernist avant-garde of the early 20th century...

. An area called Monto (in or around Montgomery Street off Sackville Street) became infamous also as the British Empire's biggest red light district, its financial viability aided by the number of British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

barracks and hence soldiers in the city, notably the Royal Barracks (later Collins Barracks

Collins Barracks (Dublin)

Collins Barracks is a former military barracks in the Arbour Hill area of Dublin, Ireland. The buildings are now the National Museum of Ireland, Decorative Arts and History...

and now one of the locations of Ireland's National Museum). Monto finally closed in the mid 1920s, following a campaign against prostitution by the Roman Catholic Legion of Mary

Legion of Mary

The Legion of Mary is an association of Catholic laity who serve the Church on a voluntary basis. It was founded in Dublin, Ireland, as a Roman Catholic Marian Movement by layman Frank Duff. Today between active and auxiliary members there are in excess of 10 million members worldwide making it...

, its financial viability having already been seriously undermined by the withdrawal of soldiers from the city following the Anglo-Irish Treaty

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Anglo-Irish Treaty , officially called the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was a treaty between the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and representatives of the secessionist Irish Republic that concluded the Irish War of...

(December 1921) and the establishment of the Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

(6 December 1922).

The Lockout

Dublin Lockout

The Dublin Lock-out was a major industrial dispute between approximately 20,000 workers and 300 employers which took place in Ireland's capital city of Dublin. The dispute lasted from 26 August 1913 to 18 January 1914, and is often viewed as the most severe and significant industrial dispute in...

. James Larkin

James Larkin

James Larkin was an Irish trade union leader and socialist activist, born to Irish parents in Liverpool, England. He and his family later moved to a small cottage in Burren, southern County Down. Growing up in poverty, he received little formal education and began working in a variety of jobs...

, a militant syndicalist trade unionist, founded the Irish Transport and General Worker's Union (ITGWU) and tried to win improvements in wages and conditions for unskilled and semi-skilled workers. His means were negotiation and if necessary sympathetic strikes. In response, William Martin Murphy

William Martin Murphy

William Martin Murphy was an Irish nationalist journalist, businessman and politician. A Member of Parliament representing Dublin from 1885 to 1892, he was dubbed 'William Murder Murphy' among Dublin workers and the press due to the Dublin Lockout of 1913...

, who owned the Dublin Tram Company, organised a cartel of employers who agreed to sack any ITGWU members and to make other employees agree not to join it. Larkin in turn called the Tram workers out on strike, which was followed by the sacking, or "lockout", of any workers in Dublin who would not resign from the union. Within a month, 25,000 workers were either on strike or locked out. Demonstrations during the dispute were marked by vicious rioting with the Dublin Metropolitan Police

Dublin Metropolitan Police

The Dublin Metropolitan Police was the police force of Dublin, Ireland, from 1836 to 1925, when it amalgamated into the new Garda Síochána.-19th century:...

, which left three people dead and hundreds more injured. James Connolly

James Connolly

James Connolly was an Irish republican and socialist leader. He was born in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, to Irish immigrant parents and spoke with a Scottish accent throughout his life. He left school for working life at the age of 11, but became one of the leading Marxist theorists of...

in response founded the Irish Citizen Army

Irish Citizen Army

The Irish Citizen Army , or ICA, was a small group of trained trade union volunteers established in Dublin for the defence of worker’s demonstrations from the police. It was formed by James Larkin and Jack White. Other prominent members included James Connolly, Seán O'Casey, Constance Markievicz,...

to defend strikers from the police. The lockout lasted for six months, after which most workers, many of whose families were starving, resigned from the union and returned to work.

The End of British Rule

Home rule

Home rule is the power of a constituent part of a state to exercise such of the state's powers of governance within its own administrative area that have been devolved to it by the central government....

(or self government), however, instead of a peaceful handover from direct British rule to limited Irish autonomy, Ireland and Dublin saw nearly ten years of political violence and instability that eventually resulted in a much more complete break with Britain than Home Rule would have represented. By 1923, Dublin was the capital of the Irish Free State

Irish Free State

The Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

, an all but independent Irish state, governing 26 of Ireland's 32 counties.

Howth Gun Running 1914

Unionists, predominantly concentrated in UlsterUlster

Ulster is one of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the north of the island. In ancient Ireland, it was one of the fifths ruled by a "king of over-kings" . Following the Norman invasion of Ireland, the ancient kingdoms were shired into a number of counties for administrative and judicial...

, though also with significant numbers in Dublin and throughout the country, resisted the introduction of Home Rule and founded the Ulster Volunteers (UVF) - a private army - to this end. In response, nationalists founded their own army, the Irish Volunteers

Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists. It was ostensibly formed in response to the formation of the Ulster Volunteers in 1912, and its declared primary aim was "to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland"...

, to make sure Home Rule became a reality. In April 1914, thousands of German weapons were imported by the UVF into the north (see Larne gunrunning). Some within the Irish Volunteers, and other nationalists unconnected with that organisation, attempted to do the same in July. The crew of Asgard

Asgard (yacht)

The Asgard is a yacht, formerly owned by the English-born Irish nationalist, and writer Robert Erskine Childers and his wife Molly Childers. It was bought for £1,000 in 1904 from one of Norway's most famous boat designers, Colin Archer...

successfully landed a consignment of surplus German rifles and ammunition at Howth

Howth

Howth is an area in Fingal County near Dublin city in Ireland. Originally just a small fishing village, Howth with its surrounding rural district is now a busy suburb of Dublin, with a mix of dense residential development and wild hillside, all on the peninsula of Howth Head. The only...

, near Dublin. Shortly after the cargo was landed, British troops from the Scottish Borderers regiment tried to seize them but were unsuccessful. The soldiers were jeered by Dublin crowds when they returned to the city centre and they retaliated by opening fire at Bachelors Walk

Bachelors Walk (Dublin)

Bachelors Walk is a street and quay on the north bank of the Liffey, Dublin, Ireland, between Swifts' Row to the west and both the southern end of O'Connell Street and O'Connell Bridge in the east.It was the setting for the eponymous tv series....

, killing three people. Ireland appeared to be on the brink of civil war by the time the Home Rule Bill

Home Rule Act 1914

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 , also known as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide self-government for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.The Act was the first law ever passed by the Parliament of...

was actually passed in September 1914. However the outbreak of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

led to its shelving. John Redmond

John Redmond

John Edward Redmond was an Irish nationalist politician, barrister, MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party from 1900 to 1918...

, the leader of the Volunteers and the Irish Parliamentary Party

Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party was formed in 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nationalist Members of Parliament elected to the House of Commons at...

, called on nationalists to join the British Army. This caused a split in the Volunteers. Thousands of Irishmen did join (particularly those from working class areas, where unemployment was high) and many died in the war. The majority, who followed Redmond's leadership, formed the National Volunteers

National Volunteers

The National Volunteers was the name taken by the majority of the Irish Volunteers that sided with Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond after the movement split over the question of the Volunteers' role in World War I.-Origins:...

. A militant minority kept the title of Irish Volunteers, some of whom were now prepared to fight against, rather than with British forces for Irish independence.

Easter Rising 1916

In April 1916 about 1,250 armed Irish republicans under Padraig Pearse staged what became known as the Easter RisingEaster Rising

The Easter Rising was an insurrection staged in Ireland during Easter Week, 1916. The Rising was mounted by Irish republicans with the aims of ending British rule in Ireland and establishing the Irish Republic at a time when the British Empire was heavily engaged in the First World War...

in Dublin in pursuit not of Home Rule but of an Irish Republic. One of the rebels' first acts was to declare this Republic to be in existence. The rebels were composed of Irish Volunteers and the much smaller Irish Citizen Army

Irish Citizen Army

The Irish Citizen Army , or ICA, was a small group of trained trade union volunteers established in Dublin for the defence of worker’s demonstrations from the police. It was formed by James Larkin and Jack White. Other prominent members included James Connolly, Seán O'Casey, Constance Markievicz,...

under James Connolly

James Connolly

James Connolly was an Irish republican and socialist leader. He was born in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, to Irish immigrant parents and spoke with a Scottish accent throughout his life. He left school for working life at the age of 11, but became one of the leading Marxist theorists of...

. The rising saw rebel forces take over strongpoints in the city, including the Four Courts

Four Courts

The Four Courts in Dublin is the Republic of Ireland's main courts building. The Four Courts are the location of the Supreme Court, the High Court and the Dublin Circuit Court. The building until 2010 also formerly was the location for the Central Criminal Court.-Gandon's Building:Work based on...

, Stephen's Green, Boland's mill

Boland's Mill

Boland's Mill is located on the Grand Canal Dock in Dublin, Ireland at the corner of Pearse Street and Barrow St. The majority of the complex consists of silos built in the 1940s. The mill stopped production in 2001 and the site is now derelict...

, the South Dublin Union and Jacobs Biscuit Factory and establishing their headquarters at the General Post Office building

General Post Office

General Post Office is the name of the British postal system from 1660 until 1969.General Post Office may also refer to:* General Post Office, Perth* General Post Office, Sydney* General Post Office, Melbourne* General Post Office, Brisbane...

in O'Connell street

O'Connell Street

O'Connell Street is Dublin's main thoroughfare. It measures 49 m in width at its southern end, 46 m at the north, and is 500 m in length...

. They held for a week until they were forced to surrender to British troops. The British deployed artillery to bombard the rebels into submission, sailing a gunboat

Gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.-History:...

named the Helga

Muirchú

Public Armed Ship Muirchú was a ship in the Irish Naval Service. She was the former Royal Navy ship HMY Helga and was involved in shelling Liberty Hall in Dublin from the River Liffey with her pair of 12 pounder naval guns during the Easter Rising of 1916.Helga was purchased by the Irish Free State...

up the Liffey and stationing field guns at Cabra

Cabra, Dublin

Cabra is a suburb on the northside of Dublin city in Ireland. It is approximately northwest of the city centre, in the administrative area of Dublin City Council. It was commonly known as Cabragh until the early 20th century.- Transport and access:...

, Phibsboro

Phibsboro

Phibsborough , often formerly shortened to Phibsboro and later Phibsboro , is a district of Dublin in Ireland.-Location:Phibsboro' is located in the Dublin 7 postal district on the Northside of the city. The area is very close to the city centre, about two kilometres from the River Liffey which...

ugh and Prussia street. Much of the city centre was destroyed by shell fire and around 450 people, about half of them civilians, were killed, with another 1,500 injured. Fierce combat took place along the grand canal at Mount street, where British troops were repeatedly ambushed and suffered heavy casualties. In addition, the rebellion was marked by a wave of looting

Looting

Looting —also referred to as sacking, plundering, despoiling, despoliation, and pillaging—is the indiscriminate taking of goods by force as part of a military or political victory, or during a catastrophe, such as during war, natural disaster, or rioting...

and lawlessness by Dublin's slum population and many of the city centre's shops were ransacked. The rebel commander, Patrick Pearse

Patrick Pearse

Patrick Henry Pearse was an Irish teacher, barrister, poet, writer, nationalist and political activist who was one of the leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916...

surrendered after a week, in order to avoid further civilian casualties. Initially, the rebellion was generally unpopular in Dublin, due to the amount of death and destruction it caused, the opinion by some that it was bad timing to irreverently hold it at Easter and also due to the fact that many Dubliners had relatives serving in the British Army.

Though the rebellion was relatively easily suppressed by the British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

military and initially faced with the hostility of most Irish people, public opinion swung gradually but decisively behind the rebels, after 16 of their leaders were executed by the British military in the aftermath of the Rising. In December 1918 the party now taken over by the rebels, Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin is a left wing, Irish republican political party in Ireland. The name is Irish for "ourselves" or "we ourselves", although it is frequently mistranslated as "ourselves alone". Originating in the Sinn Féin organisation founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffith, it took its current form in 1970...

, won an overwhelming majority of Irish parliamentary seats. Instead of taking their seats in the British House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

, they assembled in the Lord Mayor of Dublin

Lord Mayor of Dublin