History of Hertfordshire

Encyclopedia

Counties of England

Counties of England are areas used for the purposes of administrative, geographical and political demarcation. For administrative purposes, England outside Greater London and the Isles of Scilly is divided into 83 counties. The counties may consist of a single district or be divided into several...

, founded in the Norse–Saxon wars of the 9th century, and developed through commerce serving London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

. It is a land-locked county that was several times the seat of Parliament

Parliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief and ecclesiastics before making laws...

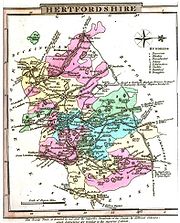

. Today, with a population slightly over 1 million, Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East region of England. The county town is Hertford.The county is one of the Home Counties and lies inland, bordered by Greater London , Buckinghamshire , Bedfordshire , Cambridgeshire and...

retains much of its historic character, but its industry and commerce have changed radically. From origins in brewing and papermaking, through aircraft manufacture, the county has developed a wider range of industry in which pharmaceuticals, financial services and film-making are prominent.

Although Hertfordshire is one of the historic counties of England

Historic counties of England

The historic counties of England are subdivisions of England established for administration by the Normans and in most cases based on earlier Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and shires...

, it does not seem to have existed as a county until the early 10th century. Its development has been tied with that of London, which lies on its southern border. London is the largest city in Western Europe; it requires an enormous tonnage of supplies each day and Hertfordshire grew wealthy on the proceeds of trade because no less than three of the old Roman roads serving the capital run through it, as do the Grand Union Canal

Grand Union Canal

The Grand Union Canal in England is part of the British canal system. Its main line connects London and Birmingham, stretching for 137 miles with 166 locks...

and other watercourses. More recently, rail links sprang up in the county, linking London to the north. Hatfield in Hertfordshire has seen two rail crashes of international importance (in 1870 and 2000).

Though nowadays Hertfordshire tends to be politically conservative, historically it was the site of a number of uprisings against the Crown, particularly in the First Barons' War

First Barons' War

The First Barons' War was a civil war in the Kingdom of England, between a group of rebellious barons—led by Robert Fitzwalter and supported by a French army under the future Louis VIII of France—and King John of England...

, the Peasants' Revolt

Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, Wat Tyler's Rebellion, or the Great Rising of 1381 was one of a number of popular revolts in late medieval Europe and is a major event in the history of England. Tyler's Rebellion was not only the most extreme and widespread insurrection in English history but also the...

, the Wars of the Roses

Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses were a series of dynastic civil wars for the throne of England fought between supporters of two rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet: the houses of Lancaster and York...

and the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

. The county has a rich intellectual history, and many writers of major importance, from Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer , known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey...

to Beatrix Potter

Beatrix Potter

Helen Beatrix Potter was an English author, illustrator, natural scientist and conservationist best known for her imaginative children’s books featuring animals such as those in The Tale of Peter Rabbit which celebrated the British landscape and country life.Born into a privileged Unitarian...

, have connections there. Quite a number of Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

s were born or grew up in Hertfordshire.

The county contains a curiously large number of abandoned settlements, which historians attribute to a mixture of poor harvests on soil hard to farm, and the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

which ravaged Hertfordshire starting in 1349.

Early history

The earliest evidence of human occupation in Hertfordshire come from a gravel pit in RickmansworthRickmansworth

Rickmansworth is a town in the Three Rivers district of Hertfordshire, England, 4¼ miles west of Watford.The town has a population of around 15,000 people and lies on the Grand Union Canal and the River Colne, at the northern end of the Colne Valley regional park.Rickmansworth is a small town in...

. The finds (of flint tools) date back 350,000 years, long before Britain became an island.

People have probably lived in the land now called Hertfordshire for about 12,000 years, since the Mesolithic

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic is an archaeological concept used to refer to certain groups of archaeological cultures defined as falling between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic....

period. Settlement continued through the Neolithic

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age, Era, or Period, or New Stone Age, was a period in the development of human technology, beginning about 9500 BC in some parts of the Middle East, and later in other parts of the world. It is traditionally considered as the last part of the Stone Age...

period, with evidence of occupation sites, enclosures, long barrows

Tumulus

A tumulus is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds, Hügelgrab or kurgans, and can be found throughout much of the world. A tumulus composed largely or entirely of stones is usually referred to as a cairn...

and even an unusual dog cemetery in the region. Although occupied, the area had a relatively low population in the Neolithic and early Bronze Age, perhaps because of its heavy, relatively poorly-drained soil. Nevertheless, just south of present-day Ware and Hertford there is some evidence of an increase in the population, with typical round huts and farming activity having been found at a site called Foxholes Farm. There is no evidence of settlement at Hertford itself from this period, although Ware and perhaps Hertford seem to have been occupied during Roman times.

.jpg)

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

, a Celtic tribe called the Catuvellauni

Catuvellauni

The Catuvellauni were a tribe or state of south-eastern Britain before the Roman conquest.The fortunes of the Catuvellauni and their kings before the conquest can be traced through numismatic evidence and scattered references in classical histories. They are mentioned by Dio Cassius, who implies...

occupied Hertfordshire. Their main settlement (or oppidum

Oppidum

Oppidum is a Latin word meaning the main settlement in any administrative area of ancient Rome. The word is derived from the earlier Latin ob-pedum, "enclosed space," possibly from the Proto-Indo-European *pedóm-, "occupied space" or "footprint."Julius Caesar described the larger Celtic Iron Age...

) was Verlamion

Verlamion

Verlamion, or Verlamio, was the tribal capital of the Catuvellauni tribe in Iron Age Britain from approximately 20 BC until shortly after the Roman invasion of 43 AD...

on the River Ver

River Ver

The Ver is a river in Hertfordshire, England. The river begins in the grounds of Markyate Cell, and flows south for 12 miles alongside Watling Street through Flamstead, Redbourn, St Albans and Park Street, and joins the River Colne at Bricket Wood....

(near present-day St Albans

St Albans

St Albans is a city in southern Hertfordshire, England, around north of central London, which forms the main urban area of the City and District of St Albans. It is a historic market town, and is now a sought-after dormitory town within the London commuter belt...

). Other oppida in Hertfordshire include sites at Cow Roast near Tring, Wheathampstead, Welwyn, Braughing, and Baldock. Hertfordshire contains several Iron Age hill fort

Hill fort

A hill fort is a type of earthworks used as a fortified refuge or defended settlement, located to exploit a rise in elevation for defensive advantage. They are typically European and of the Bronze and Iron Ages. Some were used in the post-Roman period...

s, including the largest example in Eastern England at Ravensburgh Castle in Hexton

Hexton

Hexton is a small village and civil parish about six miles west of Hitchin in Hertfordshire, England.It stands in well wooded and hilly country adjacent to the Bedfordshire border. The church, dedicated to St Faith, is mediaeval with heavy 19th century restoration...

.

There is a wealth of Iron Age burial sites in Hertfordshire, making it a place of international importance in Iron Age study. The large number of sites of all types indicates dense and complex settlement patterns immediately prior to the Roman invasion.

The Roman Invasion of Britain

In 55 BCE when the Romans first attempted to invade Britain, the CatuvellauniCatuvellauni

The Catuvellauni were a tribe or state of south-eastern Britain before the Roman conquest.The fortunes of the Catuvellauni and their kings before the conquest can be traced through numismatic evidence and scattered references in classical histories. They are mentioned by Dio Cassius, who implies...

(which is Brythonic

British language

The British language was an ancient Celtic language spoken in Britain.British language may also refer to:* Any of the Languages of the United Kingdom.*The Welsh language or the Brythonic languages more generally* British English...

for "Expert Warrior") were the largest British

Britons (historical)

The Britons were the Celtic people culturally dominating Great Britain from the Iron Age through the Early Middle Ages. They spoke the Insular Celtic language known as British or Brythonic...

tribe. Caesar's report to the Senate said that "Cassivellaun" (Cassivellaunus

Cassivellaunus

Cassivellaunus was an historical British chieftain who led the defence against Julius Caesar's second expedition to Britain in 54 BC. The first British person whose name is recorded, Cassivellaunus led an alliance of tribes against Roman forces, but eventually surrendered after his location was...

) was leader of the Britons, and Cassivellaunus' headquarters were near Wheathampstead

Wheathampstead

Wheathampstead is a village and civil parish in the City and District of St Albans, in Hertfordshire, England. It is north of St Albans and in the Hitchin and Harpenden parliamentary constituency....

in Hertfordshire. On Caesar's second invasion attempt in 54 BCE, Cassivellaunus led the British defensive forces. The Romans besieged him at Wheathampstead, and partly because of the defection of the Trinovantes

Trinovantes

The Trinovantes or Trinobantes were one of the tribes of pre-Roman Britain. Their territory was on the north side of the Thames estuary in current Essex and Suffolk, and included lands now located in Greater London. They were bordered to the north by the Iceni, and to the west by the Catuvellauni...

(whose King Cassivellaunus had had murdered), the Catuvellauni were forced to surrender. However, after the siege of Wheathampstead, Caesar returned to Rome without leaving a garrison.

Cunobelinus

Cunobelinus

Cunobeline or Cunobelinus was a historical king in pre-Roman Britain, known from passing mentions by classical historians Suetonius and Dio Cassius, and from his many inscribed coins...

became king of the Catuvellauni in 9 or 10 CE

Common Era

Common Era ,abbreviated as CE, is an alternative designation for the calendar era originally introduced by Dionysius Exiguus in the 6th century, traditionally identified with Anno Domini .Dates before the year 1 CE are indicated by the usage of BCE, short for Before the Common Era Common Era...

and ruled for about thirty years, conquering such a large area of Britain that the Roman writer Suetonius

Suetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, commonly known as Suetonius , was a Roman historian belonging to the equestrian order in the early Imperial era....

called him Britannorum Rex ( "King of Britain"). He built Beech Bottom Dyke

Beech Bottom Dyke

Beech Bottom Dyke, is a large ditch running for half a mile at the northern edge of St Albans, Hertfordshire flanked by banks on both sides. It is up to wide, and deep, and it can be followed for half a mile between the "Ancient Briton Crossroads" on the St Albans to Harpenden road until it is...

, a defensive earthwork

Earthworks (engineering)

Earthworks are engineering works created through the moving or processing of quantities of soil or unformed rock.- Civil engineering use :Typical earthworks include roads, railway beds, causeways, dams, levees, canals, and berms...

, at St Albans, which may be related to another Iron Age defensive earthwork, the Devil's Dyke

Devil's Dyke, Hertfordshire

Devil's Dyke is the remains of a defensive ditch around an ancient settlement of the Catuvellauni tribe of Ancient Britain. It lies at the east side of the current village of Wheathampstead, Hertfordshire, England...

, at Cassivellaunus' headquarters in nearby Wheathampstead

Wheathampstead

Wheathampstead is a village and civil parish in the City and District of St Albans, in Hertfordshire, England. It is north of St Albans and in the Hitchin and Harpenden parliamentary constituency....

. The Romans defeated the Catuvellauni again in July 43 CE and this time, garrisoned Britain. When the Romans took over, their settlement, laid out in 49 CE, became known as Verulamium

Verulamium

Verulamium was an ancient town in Roman Britain. It was sited in the southwest of the modern city of St Albans in Hertfordshire, Great Britain. A large portion of the Roman city remains unexcavated, being now park and agricultural land, though much has been built upon...

. Alban

Saint Alban

Saint Alban was the first British Christian martyr. Along with his fellow saints Julius and Aaron, Alban is one of three martyrs remembered from Roman Britain. Alban is listed in the Church of England calendar for 22 June and he continues to be venerated in the Anglican, Catholic, and Orthodox...

, a Roman army officer who became Britain's first Christian martyr after his arrest at Chantry Island, died in the 3rd or 4th century and gave his name to the modern town of St Albans

St Albans

St Albans is a city in southern Hertfordshire, England, around north of central London, which forms the main urban area of the City and District of St Albans. It is a historic market town, and is now a sought-after dormitory town within the London commuter belt...

. Verulamium became one of Roman Britain's major cities, the third-largest and the only to be granted self-governing status. Strong though Verulamium's defences may have been, they were not enough to stop Boudica

Boudica

Boudica , also known as Boadicea and known in Welsh as "Buddug" was queen of the British Iceni tribe who led an uprising against the occupying forces of the Roman Empire....

, who burned the city in 61 CE. The city was rebuilt, with defenses enclosing a site of some 81 hectares (200.2 acre) and was occupied into the 5th century.

Three Roman Road

Roman road

The Roman roads were a vital part of the development of the Roman state, from about 500 BC through the expansion during the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire. Roman roads enabled the Romans to move armies and trade goods and to communicate. The Roman road system spanned more than 400,000 km...

s run through Hertfordshire: Watling Street

Watling Street

Watling Street is the name given to an ancient trackway in England and Wales that was first used by the Britons mainly between the modern cities of Canterbury and St Albans. The Romans later paved the route, part of which is identified on the Antonine Itinerary as Iter III: "Item a Londinio ad...

, Ermine Street

Ermine Street

Ermine Street is the name of a major Roman road in England that ran from London to Lincoln and York . The Old English name was 'Earninga Straete' , named after a tribe called the Earningas, who inhabited a district later known as Armingford Hundred, around Arrington, Cambridgeshire and Royston,...

and the Icknield Way

Icknield Way

The Icknield Way is an ancient trackway in southern England. It follows the chalk escarpment that includes the Berkshire Downs and Chiltern Hills.-Background:...

. These are three of the "four highways" of medieval England (the other being the Fosse Way

Fosse Way

The Fosse Way was a Roman road in England that linked Exeter in South West England to Lincoln in Lincolnshire, via Ilchester , Bath , Cirencester and Leicester .It joined Akeman Street and Ermin Way at Cirencester, crossed Watling Street at Venonis south...

, which does not run through Hertfordshire) which were still the main routes through the country more than a thousand years later. The first Roman Road to be built was the Military Way, constructed very early in the Roman conquest to speed the troops' access north. Later, Ermine Street would be built directly on top of it.

Hertfordshire in the Dark Ages

After the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain, the Hertfordshire area formed parts of the Kingdom of Mercia and the Kingdom of EssexKingdom of Essex

The Kingdom of Essex or Kingdom of the East Saxons was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the so-called Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was founded in the 6th century and covered the territory later occupied by the counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, Middlesex and Kent. Kings of Essex were...

. The main early Saxon tribes there seem to have been the Hicce, Brahingas and Wæclingas. Place names tend to derive from Celtic rather than Saxon, and there is a "singular lack of Early Saxon place names." The Synod of Hertford

Council of Hertford

The Council of Hertford was a synod of the Christian Church in England held in 673. It was convened at Hertford by Theodore of Tarsus, archbishop of Canterbury...

, which was the first national Synod of the English Church, took place on 26 September 672-3. It was at this Synod that the "question of Easter" was settled, and the church agreed how to calculate the date of Easter

Computus

Computus is the calculation of the date of Easter in the Christian calendar. The name has been used for this procedure since the early Middle Ages, as it was one of the most important computations of the age....

. The Synod also marked the end of the conflict between the Celtic Church and the Romanised church introduced by Saint Augustine

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo , also known as Augustine, St. Augustine, St. Austin, St. Augoustinos, Blessed Augustine, or St. Augustine the Blessed, was Bishop of Hippo Regius . He was a Latin-speaking philosopher and theologian who lived in the Roman Africa Province...

.

King Offa of Mercia

Offa of Mercia

Offa was the King of Mercia from 757 until his death in July 796. The son of Thingfrith and a descendant of Eowa, Offa came to the throne after a period of civil war following the assassination of Æthelbald after defeating the other claimant Beornred. In the early years of Offa's reign it is likely...

(died 796) built a church at Hitchin in Hertfordshire, but it burned down in 910 CE and the monks moved to St Albans. Offa defeated Beornred of Mercia at Pirton

Pirton, Hertfordshire

Pirton is a small village and civil parish three miles north-east of Hitchin in Hertfordshire, England. The church, rebuilt in 1877, but with the remains of its 12th-century tower, is built within the bailey of a former castle...

, near Hitchin and gave his name to the village of Offley ("Offa's Lea"). Some sources (including Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris was a Benedictine monk, English chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey in Hertfordshire...

, who was a monk at St Albans) suggest he died at Offley, though he was buried fifteen miles away in Bedford

Bedford

Bedford is the county town of Bedfordshire, in the East of England. It is a large town and the administrative centre for the wider Borough of Bedford. According to the former Bedfordshire County Council's estimates, the town had a population of 79,190 in mid 2005, with 19,720 in the adjacent town...

. One of Offa's last acts was to found St Albans Abbey.

Origins of the county

The word Hertfordshire (Saxon "Heorotfordscir" or "Heorotfordscír") is attested from 866. The first reference (as "Heoroford") in the Anglo-Saxon ChronicleAnglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

is for 1011, but the county's true origins lie in the 10th century, when Edward the Elder

Edward the Elder

Edward the Elder was an English king. He became king in 899 upon the death of his father, Alfred the Great. His court was at Winchester, previously the capital of Wessex...

established two burh

Burh

A Burh is an Old English name for a fortified town or other defended site, sometimes centred upon a hill fort though always intended as a place of permanent settlement, its origin was in military defence; "it represented only a stage, though a vitally important one, in the evolution of the...

s in Hertford

Hertford

Hertford is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. Forming a civil parish, the 2001 census put the population of Hertford at about 24,180. Recent estimates are that it is now around 28,000...

in 912 and 913 respectively.

Norsemen

Norsemen is used to refer to the group of people as a whole who spoke what is now called the Old Norse language belonging to the North Germanic branch of Indo-European languages, especially Norwegian, Icelandic, Faroese, Swedish and Danish in their earlier forms.The meaning of Norseman was "people...

, Hertfordshire was on the front line. When, after the Saxon victory in the Battle of Ethandun in 878, the Saxon King Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great was King of Wessex from 871 to 899.Alfred is noted for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of southern England against the Vikings, becoming the only English monarch still to be accorded the epithet "the Great". Alfred was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself...

and Norse King Guthrum the Old

Guthrum the Old

Guthrum , christened Æthelstan, was King of the Danish Vikings in the Danelaw. He is mainly known for his conflict with Alfred the Great.-Guthrum, founder of the Danelaw:...

agreed to partition England between them, the dividing line between their territories split what was to become Hertfordshire almost through the middle, along the line of the River Lea

River Lee (England)

The River Lea in England originates in Marsh Farm , Leagrave, Luton in the Chiltern Hills and flows generally southeast, east, and then south to London where it meets the River Thames , the last section being known as Bow Creek.-Etymology:...

and then along Watling Street. Their agreement survives in the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum

Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum

The Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum is an agreement between Alfred of Wessex and Guthrum, the Viking ruler of East Anglia. Its date is uncertain, but must have been between 878 and 890. The treaty is one of the few existing documents of Alfred's reign; it survives in Old English in Corpus Christi...

which establishes the Danelaw

Danelaw

The Danelaw, as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle , is a historical name given to the part of England in which the laws of the "Danes" held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. It is contrasted with "West Saxon law" and "Mercian law". The term has been extended by modern historians to...

's extent. It seems the land now comprising Hertfordshire was then partly in the Kingdom of Essex

Kingdom of Essex

The Kingdom of Essex or Kingdom of the East Saxons was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the so-called Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was founded in the 6th century and covered the territory later occupied by the counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, Middlesex and Kent. Kings of Essex were...

(nominally under Norse control, though still populated by Saxons) and partly in the Kingdom of Mercia

Mercia

Mercia was one of the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was centred on the valley of the River Trent and its tributaries in the region now known as the English Midlands...

(which remained Saxon).

Alfred was also responsible for building weirs on the River Lea at Hertford

Hertford

Hertford is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. Forming a civil parish, the 2001 census put the population of Hertford at about 24,180. Recent estimates are that it is now around 28,000...

(Saxon "Heorotford", ford used by deer) and Ware

Ware

Ware is a town of around 18,000 people in Hertfordshire, England close to the county town of Hertford. It is also a civil parish in East Hertfordshire district. The Prime Meridian passes to the east of Ware.-Location:...

(Saxon "Waras", weir), presumably to prevent Viking ships coming upriver. King Edgar the Peaceful is credited with making Hertford the capital of the surrounding shire, presumably between 973 and 975 CE.

Early Middle Ages

Alfred died in 899, and his son Edward the Elder worked with Alfred's son-in-law, Æthelred, and daughter, Æthelflæd, to re-take parts of southern England from the Norse. During these campaigns he built the two burhs of Hertford as already noted. Their sites have not been found, and probably lie beneath the streets of Hertford itself. From Hertford, together with StaffordStafford

Stafford is the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies approximately north of Wolverhampton and south of Stoke-on-Trent, adjacent to the M6 motorway Junction 13 to Junction 14...

, Tamworth

Tamworth

Tamworth is a town and local government district in Staffordshire, England, located north-east of Birmingham city centre and north-west of London. The town takes its name from the River Tame, which flows through the town, as does the River Anker...

and Witham

Witham

Witham is a town in the county of Essex, in the south east of England with a population of 22,500. It is part of the District of Braintree and is twinned with the town of Waldbröl, Germany. Witham stands between the larger towns of Chelmsford and Colchester...

, Edward and Æthelflæd pushed the Danes back to Northumbria

Northumbria

Northumbria was a medieval kingdom of the Angles, in what is now Northern England and South-East Scotland, becoming subsequently an earldom in a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England. The name reflects the approximate southern limit to the kingdom's territory, the Humber Estuary.Northumbria was...

in a series of battles. Anglo-Saxon Hertford is an example of town planning as demonstrated by its organised rectangular grid street pattern.

There is considerable evidence of a mint in Hertford at this period. Edward the Martyr

Edward the Martyr

Edward the Martyr was king of the English from 975 until he was murdered in 978. Edward was the eldest son of King Edgar, but not his father's acknowledged heir...

(from 975 to 978), Æthelred the Unready (from 978 to 1016) and Knut the Great (from 1016 to 1035) all had coins struck there. The mint itself has not been found, but many coins exist. Over 90% of these coins were found on the Continent or in Scandinavia, which may suggest they were used for payment of Danegeld

Danegeld

The Danegeld was a tax raised to pay tribute to the Viking raiders to save a land from being ravaged. It was called the geld or gafol in eleventh-century sources; the term Danegeld did not appear until the early twelfth century...

.

The St Brice's Day massacre of 1002 probably started at Welwyn

Welwyn

Welwyn is a village and civil parish in Hertfordshire, England. The parish also includes the villages of Digswell and Oaklands. It is sometimes called Old Welwyn to distinguish it from the newer settlement of Welwyn Garden City, about a mile to the south.-History:Situated in the valley of the...

in Hertfordshire. The massacre was to be a slaughter of the Norse in England, including women and children. Probably not many Norse were actually killed, but one of those executed was Gunhilde

Gunhilde

Gunhilde is said to have been the sister of Sweyn Forkbeard, King of Denmark, and the daughter of Harald Bluetooth. She was married to Pallig, a Dane who served the King of England, Æthelred the Unready, as ealdorman of Devonshire...

, the sister of King Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark. He invaded England next year in retaliation. Forkbeard's assault on England lasted ten years, until 1013, when Æthelred fled to the continent. Forkbeard was crowned King of England on Christmas Day, but only reigned for five weeks before dying. Æthelred returned briefly and unsuccessfully until 1016, at which time he was succeeded by Forkbeard's son Knut, who granted the Royal Manor of Hitchin to his second in command, Earl Tovi.

High Middle Ages

Norman conquest of England

The Norman conquest of England began on 28 September 1066 with the invasion of England by William, Duke of Normandy. William became known as William the Conqueror after his victory at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, defeating King Harold II of England...

, Edgar the Ætheling (the successor to Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson was the last Anglo-Saxon King of England.It could be argued that Edgar the Atheling, who was proclaimed as king by the witan but never crowned, was really the last Anglo-Saxon king...

) surrendered to William the Conqueror at Berkhamsted

Berkhamsted

-Climate:Berkhamsted experiences an oceanic climate similar to almost all of the United Kingdom.-Castle:...

. William created the manor of Berkhamsted, and bestowed it on Robert, Count of Mortain

Robert, Count of Mortain

Robert, Count of Mortain, 1st Earl of Cornwall was a Norman nobleman and the half-brother of William I of England. Robert was the son of Herluin de Conteville and Herleva of Falaise and was full brother to Odo of Bayeux. The exact year of Robert's birth is unknown Robert, Count of Mortain, 1st...

, who was his half-brother. From Robert's son William de Mortain it passed to King Henry I

Henry I of England

Henry I was the fourth son of William I of England. He succeeded his elder brother William II as King of England in 1100 and defeated his eldest brother, Robert Curthose, to become Duke of Normandy in 1106...

, and is still owned by the Royal Family. Henry held court there in 1123.

The Domesday Book

Domesday Book

Domesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

, completed in 1086, lists 168 settlements in Hertfordshire. Hertfordshire's population grew quickly from then until the Black Death

Black Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

reached the county in 1349. The Norman

Normans

The Normans were the people who gave their name to Normandy, a region in northern France. They were descended from Norse Viking conquerors of the territory and the native population of Frankish and Gallo-Roman stock...

church at St Albans Abbey

St Albans Cathedral

St Albans Cathedral is a Church of England cathedral church at St Albans, England. At , its nave is the longest of any cathedral in England...

was finished in 1088.

Hertfordshire had a conflicted relationship with the King during the High Middle Ages. Like most counties in the south-east, most of Hertfordshire was in private (i.e. non-royal) ownership during the High Middle Ages. Royal land comprised about 7% of the county's area. The first Earl of Hertford

Marquess of Hertford

The titles of Earl of Hertford and Marquess of Hertford have been created several times in the peerages of England and Great Britain.The third Earldom of Hertford was created in 1559 for Edward Seymour, who was simultaneously created Baron Beauchamp of Hache...

, Gilbert de Clare, was so titled in 1138. He bore one of the first two sets of heraldic arms

Heraldry

Heraldry is the profession, study, or art of creating, granting, and blazoning arms and ruling on questions of rank or protocol, as exercised by an officer of arms. Heraldry comes from Anglo-Norman herald, from the Germanic compound harja-waldaz, "army commander"...

in England: three gold chevrons on a red shield. His grandson Richard de Clare once offered King John £100 in respect of legal proceedings concerning his inheritance, but then during the First Barons War he sided with the Barons against the King. Richard became one of the twenty-five Barons sworn to enforce the Magna Carta

Magna Carta

Magna Carta is an English charter, originally issued in the year 1215 and reissued later in the 13th century in modified versions, which included the most direct challenges to the monarch's authority to date. The charter first passed into law in 1225...

, for which he was excommunicated in 1215.

Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 until his murder in 1170. He is venerated as a saint and martyr by both the Roman Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion...

, who became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1161, held the honour of Berkhamsted Castle from 1155 until 1163. King Henry III celebrated Christmas there in 1163.

Around this time, motte-and-bailey castles were built in Great Wymondley, Pirton and Therfield. Watford was founded in the 12th century, probably as a result of a market and church set up there by the Abbot of St Albans. In 1130, the earliest Pipe Roll

Pipe Rolls

The Pipe rolls, sometimes called the Great rolls, are a collection of financial records maintained by the English Exchequer, or Treasury. The earliest date from the 12th century, and the series extends, mostly complete, from then until 1833. They form the oldest continuous series of records kept by...

shows that King Henry I

Henry I of England

Henry I was the fourth son of William I of England. He succeeded his elder brother William II as King of England in 1100 and defeated his eldest brother, Robert Curthose, to become Duke of Normandy in 1106...

's Queen Consort Adeliza

Adeliza of Louvain

Adeliza of Louvain, sometimes known in England as Adelicia of Louvain, also called Adela and Aleidis; was queen consort of the Kingdom of England from 1121 to 1135, the second wife of Henry I...

owned property in the county.

The first draft of the Magna Carta

Magna Carta

Magna Carta is an English charter, originally issued in the year 1215 and reissued later in the 13th century in modified versions, which included the most direct challenges to the monarch's authority to date. The charter first passed into law in 1225...

was written at St Albans Abbey in 1213. It contained significant provisions still in force to this day, including the principle of habeas corpus

Habeas corpus

is a writ, or legal action, through which a prisoner can be released from unlawful detention. The remedy can be sought by the prisoner or by another person coming to his aid. Habeas corpus originated in the English legal system, but it is now available in many nations...

(which was first invoked in court in 1305). Two years later, King John was in St Albans when he learned of the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

's suspension. Though John agreed to the Magna Carta, he did not adhere to it, and Hertfordshire was the main battlefield in the civil war that followed. On 16 December 1216, during the First Barons' War

First Barons' War

The First Barons' War was a civil war in the Kingdom of England, between a group of rebellious barons—led by Robert Fitzwalter and supported by a French army under the future Louis VIII of France—and King John of England...

, Hertford Castle

Hertford Castle

Hertford Castle was a Norman castle situated by the River Lea in Hertford, the county town of Hertfordshire, England.-Early history:Hertford Castle was built on a site first fortified by Edward the Elder around 911. By the time of the Norman Invasion in 1066, a motte and bailey were on the site...

surrendered after a siege from Dauphin Louis (later Louis VIII of France

Louis VIII of France

Louis VIII the Lion reigned as King of France from 1223 to 1226. He was a member of the House of Capet. Louis VIII was born in Paris, France, the son of Philip II Augustus and Isabelle of Hainaut. He was also Count of Artois, inheriting the county from his mother, from 1190–1226...

), whom the English barons had invited to England to replace John as King. Berkhamsted

Berkhamsted

-Climate:Berkhamsted experiences an oceanic climate similar to almost all of the United Kingdom.-Castle:...

Castle surrendered around the same time.

In winter 1217, royalist forces plundered St Albans, took captives and extorted £100 from the Abbot, who feared the Abbey would be burned.

In 1261 King Henry III

Henry III of England

Henry III was the son and successor of John as King of England, reigning for 56 years from 1216 until his death. His contemporaries knew him as Henry of Winchester. He was the first child king in England since the reign of Æthelred the Unready...

held parliament in the county. In 1295, another parliament was held in St Albans, and in 1299, King Edward I gave Hertford Castle to his wife Margaret of France on her wedding day.

Industry and commerce

Hertfordshire is largely on a clay sub-soil, and much of its land, though rich, is "heavy" and not well-suited to crop cultivation with a medieval ploughPlough

The plough or plow is a tool used in farming for initial cultivation of soil in preparation for sowing seed or planting. It has been a basic instrument for most of recorded history, and represents one of the major advances in agriculture...

. However, the county did grow good barley

Barley

Barley is a major cereal grain, a member of the grass family. It serves as a major animal fodder, as a base malt for beer and certain distilled beverages, and as a component of various health foods...

which later became important for the brewing trade. Hertfordshire developed more through commerce than through the agriculture which drove most of England's economy during this period.

Commerce grew in Hertfordshire from the start of the 12th century; the number of markets and fairs rose steadily from about 1100 until the Black Death. During the 13th century, Hertfordshire's commerce grew still further. The county traded in butter and cheese, and to a lesser extent meat, hides and leather. Much of this produce was bound for London. The county also developed its inns and other services for travellers to and from London.

The Knights Templar

Knights Templar

The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon , commonly known as the Knights Templar, the Order of the Temple or simply as Templars, were among the most famous of the Western Christian military orders...

built Baldock

Baldock

Baldock is a historic market town in the local government district of North Hertfordshire in the ceremonial county of Hertfordshire, England where the River Ivel rises. It lies north of London, southeast of Bedford, and north northwest of the county town of Hertford...

, starting around 1140. In 1185, a survey of the Knights' holdings showed Baldock had 122 tenants on 150 acre (0.607029 km²) of land and several skilled craftsmen. King John granted the Knights a fair and market at Baldock in 1199, to be held annually. It began on St Matthew's Day and lasted five days in all. At around the same time, the leatherworking trade was prominent in Hitchin.

An English pope

Nicholas BreakspearPope Adrian IV

Pope Adrian IV , born Nicholas Breakspear or Breakspeare, was Pope from 1154 to 1159.Adrian IV is the only Englishman who has occupied the papal chair...

, the only Englishman ever to have been elected Pope

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

, was born on a farm in Bedmond or Abbots Langley

Abbots Langley

Abbots Langley is a large village and civil parish in the English county of Hertfordshire. It is an old settlement and is mentioned in the Domesday Book. Economically the village is closely linked to Watford and was formerly part of the Watford Rural District...

in Hertfordshire, probably around 1100. He was baptised in Abbots Langley. Nicholas was refused permission to become a monk at St Albans, but his career does not seem to have suffered for this, and he was unanimously elected Pope on 2 December 1154, taking the papal name Adrian IV. He died in 1159. He was the Pope who placed Rome under an interdict

Interdict

The term Interdict may refer to:* Court order enforcing or prohibiting a certain action* Injunction, such as a restraining order...

, and is famous for his alleged Donation of Ireland

Laudabiliter

Laudabiliter was a papal bull issued in 1155 by Adrian IV, the only Englishman to serve as Pope, giving the Angevin King Henry II of England the right to assume control over Ireland and apply the Gregorian Reforms in the Irish church...

to the English throne.

Late Middle Ages

In 1302, King Edward IEdward I of England

Edward I , also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons...

granted Kings Langley

Kings Langley

Kings Langley is a historic English village and civil parish northwest of central London on the southern edge of the Chiltern Hills and now part of the London commuter belt. The major western portion lies in the borough of Dacorum and the east is in the Three Rivers district, both in the county of...

to the Prince of Wales. King Edward II

Edward II of England

Edward II , called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed by his wife Isabella in January 1327. He was the sixth Plantagenet king, in a line that began with the reign of Henry II...

's "favourite", Piers Gaveston, loved the palace at Kings Langley and he was buried there after his death in 1312. Edmund of Langley

Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York

Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, 1st Earl of Cambridge, KG was a younger son of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault, the fourth of the five sons who lived to adulthood, of this Royal couple. Like so many medieval princes, Edmund gained his identifying nickname from his...

, the first Duke of York

Duke of York

The Duke of York is a title of nobility in the British peerage. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of the British monarch. The title has been created a remarkable eleven times, eight as "Duke of York" and three as the double-barreled "Duke of York and...

and founder of the House of York

House of York

The House of York was a branch of the English royal House of Plantagenet, three members of which became English kings in the late 15th century. The House of York was descended in the paternal line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, the fourth surviving son of Edward III, but also represented...

, was born in Kings Langley on 5 June 1341 and died there on 1 August 1402.

Richard of Wallingford

Richard of Wallingford was an English mathematician who made major contributions to astronomy/astrology and horology while serving as abbot of St Albans Abbey in Hertfordshire.-Biography:...

, the mathematician and astronomer, became Abbott of St Albans in 1326. He is regarded as the father of modern trigonometry.

Hertford Castle was used as a gaol for a series of important captives during the Hundred Years' War

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War was a series of separate wars waged from 1337 to 1453 by the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet, also known as the House of Anjou, for the French throne, which had become vacant upon the extinction of the senior Capetian line of French kings...

. This was actually a series of separate wars that lasted a total of 116 years, between 1337 and 1453. The Plantagenet

House of Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet , a branch of the Angevins, was a royal house founded by Geoffrey V of Anjou, father of Henry II of England. Plantagenet kings first ruled the Kingdom of England in the 12th century. Their paternal ancestors originated in the French province of Gâtinais and gained the...

Kings of England fought the Valois Kings of France, almost entirely on French soil. Queen Isabella

Isabella of France

Isabella of France , sometimes described as the She-wolf of France, was Queen consort of England as the wife of Edward II of England. She was the youngest surviving child and only surviving daughter of Philip IV of France and Joan I of Navarre...

was imprisoned by her son, the King, in Hertford Castle in 1330, as were King David II

David II of Scotland

David II was King of Scots from 7 June 1329 until his death.-Early life:...

of Scotland and his queen in 1346, after the Battle of Neville's Cross

Battle of Neville's Cross

The Battle of Neville's Cross took place to the west of Durham, England on 17 October 1346.-Background:In 1346, England was embroiled in the Hundred Years' War with France. In order to divert his enemy Philip VI of France appealed to David II of Scotland to attack the English from the north in...

. King John II of France

John II of France

John II , called John the Good , was the King of France from 1350 until his death. He was the second sovereign of the House of Valois and is perhaps best remembered as the king who was vanquished at the Battle of Poitiers and taken as a captive to England.The son of Philip VI and Joan the Lame,...

was imprisoned there in 1359 in considerable luxury.

The Black Death midway through the 14th century massively reduced Hertfordshire's population. The number of residents probably fell by 30%–50%, and likely took until the 16th century to recover. This meant many of the settlements in Hertfordshire were abandoned, particularly in the north and east of the county where farm yields were poor. Near Tring

Tring

Tring is a small market town and also a civil parish in the Chiltern Hills in Hertfordshire, England. Situated north-west of London and linked to London by the old Roman road of Akeman Street, by the modern A41, by the Grand Union Canal and by rail lines to Euston Station, Tring is now largely a...

, a cluster of deserted medieval villages can still be seen. However, the residents who survived grew richer. The reduced population meant workers could demand higher wages and better conditions, despite laws such as the Ordinance of Labourers

Ordinance of Labourers

The Ordinance of Labourers 1349 is often considered to be the start of English labour law. Along with the Statute of Labourers , it made the employment contract different from other contracts and made illegal any attempt on the part of workers to bargain collectively...

of 1349 and the Statute of Labourers of 1351. These changed economic conditions contributed to the Peasants' Revolt

Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, Wat Tyler's Rebellion, or the Great Rising of 1381 was one of a number of popular revolts in late medieval Europe and is a major event in the history of England. Tyler's Rebellion was not only the most extreme and widespread insurrection in English history but also the...

in 1381, in which Hertfordshire's people were deeply involved. (Perhaps confusingly, another man called Richard of Wallingford

Richard of Wallingford (constable)

Richard of Wallingford , constable of Wallingford Castle and landowner in St Albans, played a key part in the English peasants' revolt of 1381. Though clearly not a peasant, he helped organise Wat Tyler’s campaign, and was involved in presenting the rebels’ petition to Richard II...

was one of revolt leader Wat Tyler

Wat Tyler

Walter "Wat" Tyler was a leader of the English Peasants' Revolt of 1381.-Early life:Knowledge of Tyler's early life is very limited, and derives mostly through the records of his enemies. Historians believe he was born in Essex, but are not sure why he crossed the Thames Estuary to Kent...

's principal allies. This is not the same man as the Abbott of St Albans.)

After Wat Tyler had been caught and executed, King Richard II

Richard II of England

Richard II was King of England, a member of the House of Plantagenet and the last of its main-line kings. He ruled from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. Richard was a son of Edward, the Black Prince, and was born during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III...

went to St Albans to quell the rebels. Richard's body was buried at Kings Langley

Kings Langley

Kings Langley is a historic English village and civil parish northwest of central London on the southern edge of the Chiltern Hills and now part of the London commuter belt. The major western portion lies in the borough of Dacorum and the east is in the Three Rivers district, both in the county of...

church in Hertfordshire in 1400, but he was moved to Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey

The Collegiate Church of St Peter at Westminster, popularly known as Westminster Abbey, is a large, mainly Gothic church, in the City of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, located just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is the traditional place of coronation and burial site for English,...

in 1413, next to his wife Anne. That same year, King Henry IV

Henry IV of England

Henry IV was King of England and Lord of Ireland . He was the ninth King of England of the House of Plantagenet and also asserted his grandfather's claim to the title King of France. He was born at Bolingbroke Castle in Lincolnshire, hence his other name, Henry Bolingbroke...

appointed his knight Hugh de Waterton to Berkhamsted Castle to supervise his children John and Philippa.

.jpg)

Battle of Shrewsbury

The Battle of Shrewsbury was a battle fought on 21 July 1403, waged between an army led by the Lancastrian King, Henry IV, and a rebel army led by Henry "Hotspur" Percy from Northumberland....

in 1403. King Henry IV married Catherine of France

Catherine of Valois

Catherine of France was the Queen consort of England from 1420 until 1422. She was the daughter of King Charles VI of France, wife of Henry V of Monmouth, King of England, mother of Henry VI, King of England and King of France, and through her secret marriage with Owen Tudor, the grandmother of...

on 2 June 1420, and gave Hertford Castle to her.

In 1413, King Henry V

Henry V of England

Henry V was King of England from 1413 until his death at the age of 35 in 1422. He was the second monarch belonging to the House of Lancaster....

kept Easter at Kings Langley. He gave the alm of a groat to the poor. Henry Chichele

Henry Chichele

Henry Chichele , English archbishop, founder of All Souls College, Oxford, was born at Higham Ferrers, Northamptonshire, in 1363 or 1364...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, visited Barnet in 1423. No bells rang, and the archbishop took offence at his poor welcome. When he returned in 1426, the church doors were

sealed against him.

Three important battles of the Wars of the Roses

Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses were a series of dynastic civil wars for the throne of England fought between supporters of two rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet: the houses of Lancaster and York...

took place in Hertfordshire. At the First Battle of St Albans

First Battle of St Albans

The First Battle of St Albans, fought on 22 May 1455 at St Albans, 22 miles north of London, traditionally marks the beginning of the Wars of the Roses. Richard, Duke of York and his ally, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, defeated the Lancastrians under Edmund, Duke of Somerset, who was killed...

on 22 May 1455, which was the first major battle of the Wars of the Roses, Richard of York

Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York

Richard Plantagenêt, 3rd Duke of York, 6th Earl of March, 4th Earl of Cambridge, and 7th Earl of Ulster, conventionally called Richard of York was a leading English magnate, great-grandson of King Edward III...

and Neville the Kingmaker

Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick

Richard Neville KG, jure uxoris 16th Earl of Warwick and suo jure 6th Earl of Salisbury and 8th and 5th Baron Montacute , known as Warwick the Kingmaker, was an English nobleman, administrator, and military commander...

defeated the Lancastrians

House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. It was one of the opposing factions involved in the Wars of the Roses, an intermittent civil war which affected England and Wales during the 15th century...

, killed their leader, Edmund Beaufort

Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset

Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, KG , sometimes styled 1st Duke of Somerset, was an English nobleman and an important figure in the Wars of the Roses and in the Hundred Years' War...

and captured King Henry VI

Henry VI of England

Henry VI was King of England from 1422 to 1461 and again from 1470 to 1471, and disputed King of France from 1422 to 1453. Until 1437, his realm was governed by regents. Contemporaneous accounts described him as peaceful and pious, not suited for the violent dynastic civil wars, known as the Wars...

. The Lancastrians recaptured the King at the Second Battle of St Albans

Second Battle of St Albans

The Second Battle of St Albans was a battle of the English Wars of the Roses fought on 17 February, 1461, at St Albans. The army of the Yorkist faction under the Earl of Warwick attempted to bar the road to London north of the town. The rival Lancastrian army used a wide outflanking manoeuvre to...

on 12 February 1461. While he was a prisoner of the Yorkists, in 1459, Henry VI kept Easter at St Albans Abbey. He gave his best gown to the prior, but the gift seems to have been regretted and the treasurer later bought it back for fifty marks.

The Battle of Barnet

Battle of Barnet

The Battle of Barnet was a decisive engagement in the Wars of the Roses, a dynastic conflict of 15th-century England. The military action, along with the subsequent Battle of Tewkesbury, secured the throne for Edward IV...

took place on 14 April 1471. Neville the Kingmaker advanced on London. He camped on Hadley Green, and King Edward IV

Edward IV of England

Edward IV was King of England from 4 March 1461 until 3 October 1470, and again from 11 April 1471 until his death. He was the first Yorkist King of England...

's army met him there. After confusion in the early morning mist, in which the Yorkists seem to have ended up fighting each other, the Lancastrians won the battle. The Kingmaker was captured and executed, and Edward's authority was never again seriously challenged.

One of the first three printing presses in England was in St Albans. England's first recorded paper mill, which was the property of one John Tate, stood in Hertford from near the very end of the 15th century. England's oldest surviving pub is in Hertfordshire and dates to this period. Ye Olde Fighting Cocks

Ye Olde Fighting Cocks

Ye Olde Fighting Cocks is a public house in St Albans, Hertfordshire, which is one of several that lay claim to being the oldest in England. It currently holds the official Guinness Book of Records title, but Ye Olde Man & Scythe in Bolton, Greater Manchester has claimed it is older by some 234 years...

, which is in St Albans, was rebuilt in 1485. Some of the foundation stones are even older, allegedly going back to the 8th century.

Renaissance

The long Elizabethan peace, and turmoil in Europe, conspired to raise English commercial power during the Renaissance. European refugees also contributed to English wealth. London was the centre of this new power, and Hertfordshire's commerce benefited accordingly.In November 1524, Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon

Catherine of Aragon , also known as Katherine or Katharine, was Queen consort of England as the first wife of King Henry VIII of England and Princess of Wales as the wife to Arthur, Prince of Wales...

held court at Hertford Castle. On 3 May 1547, King Edward VI

Edward VI of England

Edward VI was the King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death. He was crowned on 20 February at the age of nine. The son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, Edward was the third monarch of the Tudor dynasty and England's first monarch who was raised as a Protestant...

granted his sister Mary

Mary I of England

Mary I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from July 1553 until her death.She was the only surviving child born of the ill-fated marriage of Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine of Aragon. Her younger half-brother, Edward VI, succeeded Henry in 1547...

the manor and castle of Hertford, tolls from the bridge at Ware, and the manor of Hertingfordbury.

Under Mary, who as Queen earned the sobriquet

Sobriquet

A sobriquet is a nickname, sometimes assumed, but often given by another. It is usually a familiar name, distinct from a pseudonym assumed as a disguise, but a nickname which is familiar enough such that it can be used in place of a real name without the need of explanation...

"Bloody Mary", three "heretics" (that is, protestants

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

who refused to become catholic) were burnt at the stake in Hertfordshire. William Hale, Thomas Fust, and George Tankerville, were executed at Barnet, Ware, and St Albans respectively. In 1554, Queen Mary granted the town of Hertford its first charter

Charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified...

for a fee of thirteen shilling

Shilling

The shilling is a unit of currency used in some current and former British Commonwealth countries. The word shilling comes from scilling, an accounting term that dates back to Anglo-Saxon times where it was deemed to be the value of a cow in Kent or a sheep elsewhere. The word is thought to derive...

s and fourpence, due annually at Michaelmas

Michaelmas

Michaelmas, the feast of Saint Michael the Archangel is a day in the Western Christian calendar which occurs on 29 September...

.

Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

lived at Hatfield House

Hatfield House

Hatfield House is a country house set in a large park, the Great Park, on the eastern side of the town of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England. The present Jacobean house was built in 1611 by Robert Cecil, First Earl of Salisbury and Chief Minister to King James I and has been the home of the Cecil...

near Hatfield

Hatfield, Hertfordshire

Hatfield is a town and civil parish in Hertfordshire, England in the borough of Welwyn Hatfield. It has a population of 29,616, and is of Saxon origin. Hatfield House, the home of the Marquess of Salisbury, is the nucleus of the old town...

as a girl. When plague ravaged London, she held parliament

Parliament

A parliament is a legislature, especially in those countries whose system of government is based on the Westminster system modeled after that of the United Kingdom. The name is derived from the French , the action of parler : a parlement is a discussion. The term came to mean a meeting at which...

s at Hertford Castle in 1564 and 1581. The law courts moved to St Albans for the same reason. During her reign, Hertfordshire was specifically commended for its soldiers' efficiency. In the mobilisation of 1588 for the Anglo-Spanish War

Anglo-Spanish War (1585)

The Anglo–Spanish War was an intermittent conflict between the kingdoms of Spain and England that was never formally declared. The war was punctuated by widely separated battles, and began with England's military expedition in 1585 to the Netherlands under the command of the Earl of Leicester in...

, the county sent twenty-five lances and sixty light horse to Brentwood

Brentwood, Essex

Brentwood is a town and the principal settlement of the Borough of Brentwood, in the county of Essex in the east of England. It is located in the London commuter belt, 20 miles east north-east of Charing Cross in London, and near the M25 motorway....

, a thousand infantry to Tilbury

Tilbury

Tilbury is a town in the borough of Thurrock, Essex, England. As a settlement it is of relatively recent existence, although it has important historical connections, being the location of a 16th century fort and an ancient cross-river ferry...

, a thousand to Stratford-at-Bow

Bow, London

Bow is an area of London, England, United Kingdom in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is a built-up, mostly residential district located east of Charing Cross, and is a part of the East End.-Bridges at Bowe:...

, and five hundred to guard Her Majesty's person. The Arms of Hertfordshire were granted next year.

King James I

James I of England

James VI and I was King of Scots as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the English and Scottish crowns on 24 March 1603...

was often in Hertfordshire and had several works carried out in the county. He built Theobalds Park

Theobalds House

Theobalds House , located in Theobalds Park, just outside Cheshunt in the English county of Hertfordshire, was a prominent stately home and royal palace of the 16th and early 17th centuries.- Early history :...

, enclosing a large tract of southern Hertfordshire in a wall. Parts of the wall still exist. He also had a hand in creating the New River

New River (England)

The New River is an artificial waterway in England, opened in 1613 to supply London with fresh drinking water taken from the River Lea and from Amwell Springs , and other springs and wells along its course....

, which was the brainchild of Welsh entrepreneur, Hugh Myddelton: an artificial watercourse that predated the building of England's canal network by over a century.

James I, who was a confirmed dog-lover, also built a huge kennel (about 46 feet (14 m) long) and dog-yard (over half an acre in size) at Royston

Royston, Hertfordshire

Royston is a town and civil parish in the District of North Hertfordshire and county of Hertfordshire in England.It is situated on the Greenwich Meridian, which brushes the towns western boundary, and at the northernmost apex of the county on the same latitude of towns such as Milton Keynes and...

. He seems to have loved Royston and spent considerable time there, hunting and feasting and enjoying himself—so much so that his favourite dog, Jowler, returned one evening with a note tied to his collar. The note read: "Good Mr Jowler, we pray you to speak to the King (for he hears you every day and so he doth not us) that it will please His Majesty to go back to London, for else the country will be undone; all our provision is spent already and we are not able to entertain him longer."

During the civil war

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

, the county was mainly parliamentarian. St Albans was an especially staunch parliamentary stronghold. In the course of this war, deserters and mutineers among the various encamped armies ravaged the Chilterns, plundered Ashridge, rifled Little Gaddesden Church and broke open its tombs. In 1645, a dozen men of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

's New Model Army

New Model Army

The New Model Army of England was formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, and was disbanded in 1660 after the Restoration...

were hanged for outrages against the people of the county.

In 1647, the parliamentary army, still unpaid after their victory in the First English Civil War

First English Civil War

The First English Civil War began the series of three wars known as the English Civil War . "The English Civil War" was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1651, and includes the Second English Civil War and...

, camped on Thriploe Heath near Royston. They wrote to Parliament demanding their pay. This led to a clash between Cromwell's army and the Levellers

Levellers

The Levellers were a political movement during the English Civil Wars which emphasised popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law, and religious tolerance, all of which were expressed in the manifesto "Agreement of the People". They came to prominence at the end of the First...

at Cockbush Field, near Ware, on 15 November 1647. Cromwell captured and imprisoned the Levellers' "agitators" and a number were sentenced to death, though only one was actually executed.

After the Great Fire of London

Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through the central parts of the English city of London, from Sunday, 2 September to Wednesday, 5 September 1666. The fire gutted the medieval City of London inside the old Roman City Wall...

, many children were sent to Hertfordshire: 62 were sent to Ware, and 56 to Hertford. A few years later the mayor and people of Hertford petitioned King Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

to confirm, amend and expand the town's charters. Enquiries were made as to whether

anyone would object, and three prominent men did, but the attorney general dismissed their objections on grounds of malice in 1680. The town henceforth had its own coroner, who doubled as the town clerk, and both the court-day and market-day were changed so as not to coincide with nearby markets at Ware, Hoddesdon or Hatfield.

In 1683, there was a plot to assassinate Charles II and his brother

Rye House Plot

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a plan to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother James, Duke of York. Historians vary in their assessment of the degree to which details of the conspiracy were finalized....

as he passed through Rye House in Hertfordshire. Unfortunately for the plotters, the Royal party was early, so the opportunity was missed; when the plot was discovered, it became a pretext for a purge of the Whig leaders.

Modern era

Smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

broke out in Hertford gaol in 1729, and spread into the town. The next year, smallpox hit Hitchin, killing 158 people. The River Lea Navigation Act of 1739 led to the river being improved, becoming navigable as far as Ware. Locks

Lock (water transport)

A lock is a device for raising and lowering boats between stretches of water of different levels on river and canal waterways. The distinguishing feature of a lock is a fixed chamber in which the water level can be varied; whereas in a caisson lock, a boat lift, or on a canal inclined plane, it is...

were built in Ware, Broxbourne

Broxbourne

Broxbourne is a commuter town in the Broxbourne borough of Hertfordshire in the East of England with a population of 13,298 in 2001.It is located 17.1 miles north north-east of Charing Cross in London and about a mile north of Wormley and south of Hoddesdon...

, and "Stanstead" (presumably Stanstead Abbotts

Stanstead Abbotts

Stanstead Abbotts is a village and civil parish in the district of East Hertfordshire, Hertfordshire, England. At the 2001 census the parish had a population of 1,983...

rather than Stansted Mountfitchet

Stansted Mountfitchet

Stansted Mountfitchet is a village and civil parish in the county of Essex, England, near the Hertfordshire border, north of London. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 5,533. The village is served by Stansted Mountfitchet railway station....

, which is not on the Lea). By 1797, the Grand Junction Canal (now called the Grand Union Canal

Grand Union Canal

The Grand Union Canal in England is part of the British canal system. Its main line connects London and Birmingham, stretching for 137 miles with 166 locks...

) was being cut. Its highest point is the Tring Summit in Hertfordshire, which was formed in 1799. Because a canal barge can hold so much more than a wagon, the waterways expansions increased the quantity of supplies that could reach London (and the amount of refuse and manure that could be carted away).

Mobilisation for the Seven Years War affected Hertfordshire. In 1756, £350 was paid to the inns and public houses of Ware for the troops staying with them. The next year, Pitt's

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham PC was a British Whig statesman who led Britain during the Seven Years' War...

army reforms made Hertfordshire liable to provide 560 officers and men.

The county also contributed soldiers to the French Revolutionary Wars

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars were a series of major conflicts, from 1792 until 1802, fought between the French Revolutionary government and several European states...

. On 7 May 1794, lists opened for the Hertfordshire Yeomanry Cavalry Regiment, which comprised five troops of cavalry. The Loyal Hemel Hempstead Volunteers formed in 1797. Two further troops of volunteers were raised in 1798, at Borehamwood

Borehamwood

-Film industry:Since the 1920s, the town has been home to several film studios and many shots of its streets are included in final cuts of 20th century British films. This earned it the nickname of the "British Hollywood"...

and Sawbridgeworth

Sawbridgeworth

Sawbridgeworth is a small, mainly residential, town and also a civil parish in Hertfordshire, England.- Location :Sawbridgeworth is four miles south of Bishop's Stortford, twelve miles east of Hertford and nine miles north of Epping. It lies on the A1184 and has a railway station that links to...

, and the same year, the Hitchin Volunteers were also raised, but their duty was only to defend land within three miles (5 km) of Hitchin.

In 1795, a Dr Walker wrote a report on agriculture and forestry in the county. He said "Herts is justly deemed the first and best corn county in the kingdom", an assessment that may not be free from local bias. It nevertheless shows how more advanced farming techniques and soil improvement programmes had enabled farmers to work Hertfordshire's "heavier" soils to better effect since the Saxon–Norse wars.

Thanks to a rapidly-increasing population and improved record-keeping practices, the volume of paper records for Hertfordshire in the 19th and 20th centuries is huge. Many of these documents are written or printed on paper made locally, at a time when paper-making joined brewing as another dominant industry in the county.

John Dickinson (1782–1869)

John Dickinson invented a continuous mechanised papermaking process and founded the paper mills at Croxley Green, Apsley and Nash Mills in England, which evolved into John Dickinson Stationery Limited...

purchased Apsley Mills in Hemel Hempstead

Hemel Hempstead

Hemel Hempstead is a town in Hertfordshire in the East of England, to the north west of London and part of the Greater London Urban Area. The population at the 2001 Census was 81,143 ....

for his newly-patented paper-making machine. In a dispute with the Society of Paper-Makers in 1821, he dismissed the men involved and trained replacements. By 1825, Apsley

Apsley

Apsley is a 19th century mill town in the county of Hertfordshire, England. It is a historic industrial site situated in a valley of the Chiltern Hills. It is positioned below the confluence of two permanent rivers, the Gade and Bulbourne. In an area of little surface water this was an obvious site...

and Nash Mills

Nash Mills

Nash Mills is a civil parish within Hemel Hempstead and Dacorum Borough Council on the northern side of the Grand Union Canal, formerly the River Gade, and in the southernmost corner of Hemel Hempstead...

in Hemel Hempstead were using steam power to produce paper. Dickinson patented his silk threadpaper in 1829, which was used, among other things, for Exchequer Bonds

Government bond

A government bond is a bond issued by a national government denominated in the country's own currency. Bonds are debt investments whereby an investor loans a certain amount of money, for a certain amount of time, with a certain interest rate, to a company or country...

, and had to be made under supervision from two excise men. He built Croxley Mills, near Rickmansworth

Rickmansworth