History of Peru

Encyclopedia

The history of Peru spans several millennia, extending back through several stages of cultural development in the mountain region and the coastal desert.

About 15,200 years ago, groups of people are believed to have crossed the Bering Strait

from Asia and survived as nomads, hunting, gathering fruits and vegetables and fishing in the sea, rivers and lakes. Peruvian territory was home to the Norte Chico civilization

, one of the six oldest in the world, and to the Inca Empire

, the largest state in Pre-Columbian

America. It was conquered by the Spanish Empire

in the 16th century, which established a Viceroyalty

with jurisdiction over most of its South American domains. The nation declared independence

from Spain in 1821 butt consolidated only after the Battle of Ayacucho

, three years later.

6000 BC in the coastal provinces of Chilca

and Paracas

, and in the highland province of Callejón de Huaylas

. Over the following three thousand years, inhabitants switched from nomadic lifestyles to cultivating land, as evidence from sites such as Jiskairumoko

, Kotosh

, and Huaca Prieta

demonstrates. Cultivation of plants such as corn

and cotton

(Gossypium barbadense) began, as well as the domestication of animals such as the wild ancestors of the llama

, the alpaca

, and the guinea pig

. Inhabitants practiced spinning

and knitting

of cotton and wool, basketry

, and pottery

.

As these inhabitants became sedentary, farming allowed them to build settlements and new societies emerged along the coast and in the Andean mountains. The first known city in all of the Americas was Caral

, located in the Supe Valley 200 km north of Lima. It is the oldest city in America and was built in approximately 2500 BC.

What is left from the civilization, also called Norte Chico

, are about 30 pyramidical structures built up in receding terraces ending in a flat roof; some of them measured up to 20 meters in height. Caral is one of six world centers of the rise of civilization.

In the early 21st century, archeologists have discovered new evidence of ancient pre-Ceramic complex cultures. In 2005 Tom D. Dillehay and his team announced the discovery of three irrigation

canal

s that were 5400 years old, and a possible fourth that is 6700 years old, all in the Zaña Valley in northern Peru, evidence of community activity to support improved agriculture at a much earlier date than previously believed. In 2006, Robert Benfer and a research team discovered a 4200-year-old observatory

at Buena Vista

, a site in the Andes several kilometers north of present-day Lima

. They believe the observatory was related to the society's reliance on agriculture and understanding the seasons. The site includes the oldest three-dimensional sculptures found thus far in South America. In 2007 the archeologist Walter Alva

and his team found a 4000-year-old temple with painted murals at Ventarrón

, in the northwest Lambayeque

region. The temple contained ceremonial offerings gained from exchange with Peruvian jungle societies, as well as those from the Ecuador

an coast. Such finds show sophisticated, monumental construction requiring large-scale organization of labor, suggesting that hierarchical, complex cultures arose in South America much earlier than scholars had thought.

Many other civilizations developed and were absorbed by the most powerful ones such as Kotosh, Chavin

Many other civilizations developed and were absorbed by the most powerful ones such as Kotosh, Chavin

, Paracas, Lima

, Nasca, Moche

, Tiwanaku

, Wari

, Lambayeque

, Chimu, Chan Chan

, and Chincha

, among others. The Paracas culture

emerged on the southern coast around 300 BC. They are known for their use of vicuña

fibers instead of just cotton

to produce fine textile

s—innovations that did not reach the northern coast of Peru until centuries later. Coastal cultures such as the Moche

and Nazca

flourished from about 100 BC to about AD 700: the Moche produced impressive metalwork, as well as some of the finest pottery

seen in the ancient world, while the Nazca are known for their textiles and the enigmatic Nazca lines

.

These coastal cultures eventually began to decline as a result of recurring el Niño floods and droughts. In consequence, the Huari and Tiwanaku

, who dwelt inland in the Andes

became the predominant cultures of the region encompassing much of modern-day Peru and Bolivia

. They were succeeded by powerful city-state

s, such as Chancay

, Sipan

, and Cajamarca

, and two empires: Chimor

and Chachapoyas culture

These cultures developed relatively advanced techniques of cultivation

, gold and silver craft, pottery

, metallurgy

, and knitting

. Around 700 BC, they appear to have developed systems of social organization that were the precursors of the Inca

civilization.

Not all Andean cultures were willing to offer their loyalty to the Incas as the Incas expanded their empire, and many were openly hostile. The people of the Chachapoyas culture

were an example of this, but the Inca eventually conquered and integrated them into their empire.

The Incas

The Incas

built the largest empire and dynasty of pre-Columbian America

. The Tahuantinsuyo—which is derived from Quechua

for "The Four United Regions"—reached its greatest extension at the beginning of the 16th century. It dominated a territory that included (from north to south): Ecuador

, part of Colombia

, the northern half of Chile

, and the north-west part of Argentina

; and from east to west, from Bolivia

to the Amazonian forests

and Peru

.

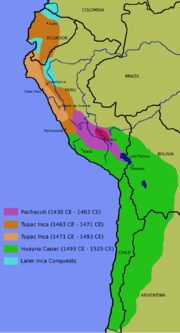

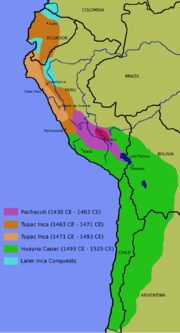

The empire originated from a tribe based in Cuzco, which became the capital. Pachacuti was the first ruler to considerably expand the boundaries of the Cuzco state. His offspring later ruled an empire by both violent and peaceful conquest.

In Cuzco, the royal city was created to resemble a Cougar; the head, the main royal structure, formed what is now known as Sacsayhuaman. The Empire's administrative, political, and military center was located in Cuzco. The empire was divided into four quarters: Chinchasuyo, Antisuyo, Contisuyo, and Collasuyo.

Quechua

was the official language, imposed on the citizens. It was the language of a neighbouring tribe of the original tribe of the empire. Conquered populations—tribes, kingdoms, states, and cities—were allowed to practice their own religions and lifestyles, but had to recognize Inca cultural practices as superior to their own. Inti, the sun god, was to be worshipped as one of the most important gods of the empire. His representation on earth was the Inca ("Emperor").

The Tahuantinsuyo was organized in dominions with a stratified society, in which the ruler was the Inca. It was also supported by an economy based on the collective property of the land. In fact, the Inca Empire

was conceived like an ambitious and audacious civilizing project, based on a mythical thought, in which the harmony of the relationships between the human being, nature, and gods

was truly essential.

Many interesting customs were observed, for example the extravagant feast of Inti Raymi which gave thanks to the God Sun, and the young women who were the Virgins of the Sun, sacrificial virgins devoted to the Inti. The empire, being quite large, also had an impressive transportation system of roads to all points of the empire called the Inca Trail

, and chasquis, message carriers who relayed information from anywhere in the empire to Cuzco.

Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu

(Quechua: Old Peak; sometimes called the "Lost City of the Incas") is a well-preserved pre-Columbian Inca ruin located on a high mountain ridge above the Urubamba Valley, about 70 km (44 mi) northwest of Cuzco. Elevation measurements vary depending on whether the data refers to the ruin or the extremity of the mountain; Machu Picchu tourist information reports the elevation as 2,350 m (7,711 ft)[1]. Forgotten for centuries by the outside world, although not by locals, it was brought back to international attention by Yale archaeologist Hiram Bingham III

, who rediscovered it in 1911 and wrote a best-selling work about it. Peru is pursuing legal efforts to retrieve thousands of artifacts that Bingham removed from the site.

Although Machu Picchu

is by far the most well-known internationally, Peru boasts many other sites where the modern visitor can see extensive and well-preserved ruins, remnants of the Inca-period and even older constructions. Much of the Inca architecture and stonework found at these sites continues to confound archaeologists. For example, at Sacsayhuaman, in Cuzco, the zig-zag-shaped walls are composed of massive boulders fitted very precisely to one another's irregular, angular shapes. No mortar holds them together, but nonetheless they have remained absolutely solid through the centuries, surviving earthquakes that flattened many of Cuzco's colonial constructions. Damage to the walls visible today was mainly inflicted during battles between the Spanish and the Inca, as well as later, in the colonial era. As Cuzco grew, Sacsayhuaman's walls were partially dismantled, the site becoming a convenient source of construction materials for the city's newer inhabitants. Today we not only do not know how these stones were shaped and smoothed, lifted on top of one another (they really are very massive) or fitted together by the Incas; we also don't know how they started got the stones to the site in the first place. The stone used is not native to the area, and most likely came from mountains many miles away.

When the Spanish

landed in 1531, Peru

's territory was the nucleus of the highly developed Inca civilization. Centered at Cuzco

, the Inca Empire extended over a vast region, stretching from northern Ecuador

to central Chile

.

Francisco Pizarro

and his brothers were attracted by the news of a rich and fabulous kingdom. In 1532, they arrived in the country, which they called Peru. (The forms Biru, Pirú, and Berú are also seen in early records.) According to Raúl Porras Barrenechea

, Peru is not a Quechua

n nor Caribbean

word, but Indo-Hispanic or hybrid.

In the years between 1524 and 1526 smallpox

, introduced from Panama and preceding the Spanish conquerors swept through the Inca Empire. The death of the Incan ruler Huayna Capac

as well as most of his family including his heir, caused the fall of the Incan political structure and contributed to the civil war

between the brothers Atahualpa and Huáscar

. Taking advantage of this, Pizarro carried out a coup d'état

. On November 16, 1532, while the natives were in a celebration in Cajamarca

, the Spanish in a surprise move captured the Inca Atahualpa

during the Battle of Cajamarca

, causing a great consternation among the natives and conditioning the future course of the fight. When Huáscar was killed, the Spanish tried and convicted Atahualpa of the murder, executing him by strangulation.

For a period, Pizarro maintained the ostensible authority of the Inca, recognizing Túpac Huallpa

as the Sapa Inca after Atahualpa's death. But the conqueror's abuses made this façade too obvious. Spanish domination consolidated itself as successive indigenous rebellions were bloodily repressed. By March 23, 1534, Pizarro and the Spanish had refounded the Inca city of Cuzco as a new Spanish colonial settlement.

Establishing a stable colonial government was delayed for some time by native revolts and bands of the Conquistadores (led by Pizarro and Diego de Almagro

) fighting among themselves. A long civil war developed, from which the Pizarros emerged victorious at the Battle of Las Salinas

. In 1541, Pizarro was assassinated by a faction led by Diego de Almagro (El Mozo), and the stability of the original colonial regime was shaken up in the ensuing civil war

.

Despite this, the Spaniards did not neglect the colonizing process. Its most significant milestone was the foundation of Lima

Despite this, the Spaniards did not neglect the colonizing process. Its most significant milestone was the foundation of Lima

in January 1535, from which the political and administrative institutions were organized. The new rulers instituted an encomienda system

, by which the Spanish extracted tribute from the local population, part of which was forwarded to Seville

in return for converting the natives to Christianity. Title to the land itself remained with the king of Spain. As governor of Peru, Pizarro used the encomienda system to grant virtually unlimited authority over groups of native Peruvians to his soldier companions, thus forming the colonial land-tenure structure. The indigenous inhabitants of Peru were now expected to raise Old World

cattle

, poultry

, and crops for their landlords. Resistance was punished severely, giving rise to the "Black Legend

".

The necessity of consolidating Spanish royal authority over these territories, led to the creation of a Real Audiencia (Royal Audience). The following year, in 1542, the Viceroyalty of Peru

(in Spanish, Virreinato del Perú) was established, with authority over most of Spanish-ruled South America. (Colombia

, Ecuador

, Panamá

and Venezuela

were split off as the Viceroyalty of New Granada

(in Spanish, Virreinato de Nueva Granada) in 1717; and Argentina

, Bolivia

, Paraguay

, and Uruguay

were set up as the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata

in 1776.)

In response to the internal strife plaguing the country after Pizarro's death, Spain finally sent Blasco Núñez Vela

to be Peru's first viceroy in 1544. He was later killed by Pizarro's brother, Gonzalo Pizarro

, but a new viceroy, Pedro de la Gasca

, eventually managed to restore order. He captured and executed Gonzalo Pizarro.

A census taken by the last Quipucamayoc indicated that there were 12 million inhabitants of Inca Peru; 45 years later, under viceroy Toledo, the census figures amounted to only 1,100,000 Indians. Historian David N. Cook estimates that their population decreased from an estimated 9 million in the 1520s to around 600,000 in 1620 mainly because of infectious disease

s. While the attrition was not an organized attempt at genocide

, the results were similar. Scholars now believe that, among the various contributing factors, epidemic

disease

such as smallpox

(unlike the Spanish, the Amerindians

had no immunity to the disease) was the overwhelming cause of the population decline of the American natives. Inca cities were given Spanish Christian names and rebuilt as Spanish towns centered around a plaza

with a church or cathedral facing an official residence. A few Inca cities like Cuzco retained native masonry for the foundations of their walls. Other Inca sites, like Huanuco Viejo, were abandoned for cities at lower altitudes more hospitable to the Spanish.

In 1542, the Spanish Crown created the Viceroyalty of Peru

In 1542, the Spanish Crown created the Viceroyalty of Peru

, which was reorganized after the arrival of Viceroy Francisco de Toledo in 1572. He put an end to the indigenous State of Vilcabamba

, executed Tupac Amaru I

. He also sought economic development through commercial monopoly and mineral extraction, mainly from the silver mines of Potosí

. He reused the Inca mita

, a forced labor program, to mobilize native communities for mining work. This organization transformed Peru into the principal source of Spanish wealth and power in South America.

The town of Lima

, founded by Pizarro on January 18, 1535 as the "Ciudad de Reyes" (City of Kings), became the seat of the new viceroyalty. It grew into a powerful city, with jurisdiction over most of Spanish South America. Precious metals passed through Lima on its way to the Isthmus of Panama

and from there to Seville, Spain.By the 18th century, Lima had become a distinguished and aristocratic colonial capital, seat of a university and the chief Spanish stronghold in the Americas.

Nevertheless, throughout the eighteenth century, further away from Lima in the provinces, the Spanish did not have complete control. The Spanish could not govern the provinces without the help of local elite. This local elite, who governed under the title of curaca, took pride in their Incan history . Additionally, throughout the eighteenth century, indigenous people rebelled against the Spanish. Two of the most important rebellions were that of Juan Santos Atahualpa

in 1742 in the Andean jungle provinces of Tarma and Jauja, and Rebellion of Tupac Amaru II

in 1780 around the highlands near Cuzco.

At the time, an economic crisis was developing due to creation of the Viceroyalties of New Granada

and Rio de la Plata

(at the expense of its territory), the duty exemptions that moved the commercial center from Lima

to Caracas

and Buenos Aires

, and the decrease of the mining and textile productio. This crisis proved favorable for the indigenous rebellion of Tupac Amaru II and determined the progressive decay of the Viceroyalty of Peru.

In 1808, Napoleon invaded the Iberian Peninsula

and took the king, Ferdinand XVII, hostage. Later in 1812, the Cadíz Cortes, the national legislative assembly of Spain, promulgated a liberal Constitution of Cadiz

. These events inspired emancipating ideas between the Spanish Criollo people

throughout the Spanish America. In Perú, The Creole rebellion of Huánuco arose in 1812 and the rebellion of Cuzco arose between 1814 and 1816. Despite these rebellions, the Criollo

oligarchy in Perú remained mostly Spanish loyalist, which accounts for the fact that the Viceroyalty of Peru

became the last redoubt of the Spanish dominion in South America.

Peru's movement toward independence was launched by an uprising of Spanish-American landowners and their forces, led by José de San Martín

Peru's movement toward independence was launched by an uprising of Spanish-American landowners and their forces, led by José de San Martín

of Argentina

and Simón Bolívar

of Venezuela

. San Martín, who had displaced the royalists of Chile after the Battle of Chacabuco

, and who had disembarked in Paracas

in 1819, led the military campaign of 4,200 soldiers. The expedition which included warships was organized and financed by Chile which sailed from Valparaíso

in August 1820. San Martin proclaimed the independence of Peru in Lima on July 28, 1821, with the words "... From this moment on, Peru is free and independent, by the general will of the people and the justice of its cause that God defends. Long live the homeland! Long live freedom! Long live our independence!".

Still, the situation remained changing and emancipation was only completed by December 1824, when General Antonio José de Sucre

defeated Spanish troops at the Battle of Ayacucho

. Spain made futile attempts to regain its former colonies, such as at the Battle of Callao

, and only in 1879 finally recognized Peruvian independence.

A short-lived attempt to reunite Peru and Bolivia

was made during the period 1836–1839 when the Peru-Bolivian Confederation

came into existence, severe internal opposition led to its demise in the War of the Confederation

.

Peru embarked on a railroad building program. Henry Meiggs

built a standard gauge line from Callao

across the Andes to the Interior, Huancayo; striking for Cuzco he built the line but also bankrupted the country.

In 1879, Peru entered the War of the Pacific

which lasted until 1884. Bolivia invoked its alliance with Peru against Chile. The Peruvian Government tried to mediate the dispute by sending a diplomatic team to negotiate with the Chilean government, but the committee concluded that war was inevitable. Chile declared war on April 5, 1879. Almost five years of war ended with the loss of the department of Tarapacá and the provinces of Tacna and Arica, in the Atacama region.

Originally Chile committed to a referendum for the cities of Arica and Tacna to be held years later, in order to self determine their national affiliation. However, Chile refused to apply the Treaty, and both countries could not determine the statutory framework. In an arbitrage that both countries admitted, the USA decided that the plebiscite was impossible to take, therefore, direct negotiations between the parties led to a treaty (Treaty of Lima

, 1929), in which Arica

was ceded to Chile and Tacna

remained in Peru. Tacna returned to Peru on August 29, 1929. The territorial loss and the extensive looting of Peruvian cities by Chilean troops left scars on the country's relations with Chile that have not yet fully healed.

Following the Ecuadorian-Peruvian War

of 1941, the Rio Protocol

sought to formalize the boundary between those two countries. Ongoing boundary disagreements

led to a brief war in early 1981 and the Cenepa War

in early 1995, but in 1998 the governments of both countries signed a historic peace treaty that clearly demarcated the international boundary between them. In late 1999, the governments of Peru and Chile likewise similarly implemented the last outstanding article of their 1929 border agreement.

, an extraordinary effort of rebuilding began. The government started to initiate a number of social and economic reforms in order to recover from the damage of the war. Political stability was achieved only in the early 1900s.

In 1894, Nicolás de Piérola

, after allying his party with the Civil Party of Peru to organize guerrillas with fighters to occupy Lima, ousted Andrés Avelino Cáceres

and once again became president of Peru in 1895. After a brief period in which the military once again controlled the country, civilian rule was permanently established with Pierola's election in 1895. His second term was successfully completed in 1899 and was marked by his reconstruction of a devastated Peru by initiating fiscal, military, religious, and civil reforms. Until the 1920s, this period was called the "Aristocratic Republic", since most of the presidents that ruled the country were from the social elite.

During Augusto B. Leguía

's periods in government (1908–1912 and 1919–1930, the latter known as the "Oncenio" (the "Eleventh"), the entrance of American capital became general and the bourgeoisie

was favored. This policy, along with increased dependence on foreign investment, focused opposition from the most progressive sectors of Peruvian society against the landowner oligarchy.

In 1929, Peru and Chile signed a final peace treaty, the Treaty of Lima

by which Tacna returned to Peru and Peru yielded permanently the formerly rich provinces of Arica and Tarapacá, but kept certain rights to the port activities in Arica and decisions of what Chile can do on those territories.

party had the opportunity to cause system reforms by means of political actions, but it was not successful. This was a nationalistic movement, populist and anti-imperialist, headed by Victor Raul Haya de la Torre

in 1924. The Socialist Party of Peru, later the Peruvian Communist Party

, was created four years later and it was led by Jose C. Mariategui

.

Repression was brutal in the early 1930s and tens of thousands of APRA followers (Apristas) were executed or imprisoned. This period was also characterized by a sudden population growth and an increase in urbanization. According to Alberto Flores Galindo, "By the 1940 census, the last that utilized racial categories, mestizo

s were grouped with whites, and the two constituted more than 53 percent of the population. Mestizos likely outnumbered Indians and were the largest population group." During World War II, Peru was the first South American nation to align with the United States and its allies against Germany and Japan.

In the mid-20th century, Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre

(founder of the APRA), together with José Carlos Mariátegui

(leader of the Peruvian Communist Party

), were two major forces in Peruvian politics. Ideologically opposed, they both managed to create the first political parties that tackled the social and economic problems of the country. Although Mariátegui died at a young age, Haya de la Torre was twice elected president, but prevented by the military from taking office. During World War II, the country rounded up around 2,000 of its Japanese immigrant population and shipped them to the United States as part of the Japanese-American internment program.

President Bustamante y Rivero

hoped to create a more democratic government by limiting the power of the military and the oligarchy. Elected with the cooperation of the APRA, conflict soon arose between the President and Haya de la Torre. Without the support of the APRA party, Bustamante y Rivero found his presidency severely limited. The President disbanded his Aprista cabinet and replaced it with a mostly military one. In 1948, Minister Manuel A. Odria

and other right-wing elements of the Cabinet urged Bustamante y Rivero to ban the APRA, but when the President refused, Odría resigned his post.

In a military coup on October 29, Gen. Manuel A. Odria

became the new President. Odría's presidency was known as the Ochenio. He came down hard on APRA, momentarily pleasing the oligarchy and all others on the right, but followed a populist

course that won him great favor with the poor and lower classes. A thriving economy allowed him to indulge in expensive but crowd-pleasing social policies. At the same time, however, civil rights

were severely restricted and corruption

was rampant throughout his régime.

It was feared that his dictatorship would run indefinitely, so it came as a surprise when Odría allowed new elections. During this time, Fernando Belaúnde Terry

started his political career, and led the slate submitted by the National Front of Democratic Youth. After the National Election Board refused to accept his candidacy, he led a massive protest, and the striking image of Belaúnde walking with the flag was featured by newsmagazine Caretas

the following day, in an article entitled "Así Nacen Los Lideres" ("Thus Are Leaders Born"). Belaúnde's 1956 candidacy was ultimately unsuccessful, as the dictatorship-favored right-wing candidacy of Manuel Prado Ugarteche

took first place.

Belaúnde ran for president once again in the National Elections of 1962, this time with his own party, Acción Popular (Popular Action). The results were very tight; he ended in second place, following Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre (APRA), by less than 14,000 votes. Since none of the candidates managed to get the Constitutionally-established minimum of one third of the vote required to win outright, selection of the President should have fallen to Congress; the long-held antagonistic relationship between the military and APRA prompted Haya de la Torre to make a deal with former dictator Odria, who had come in third, which would have resulted in Odria taking the Presidency in a coalition government.

However, widespread allegations of fraud prompted the Peruvian military to depose Prado and install a military junta, led by Ricardo Perez Godoy. Godoy ran a short transitional government and held new elections in 1963, which were won by Belaúnde by a more comfortable but still narrow five percent margin.

Throughout Latin America in the 1960s, communist movements inspired by the Cuban Revolution

sought to win power through guerrilla warfare

. The Revolutionary Left Movement (Peru)

, or MIR, launched an insurrection that had been crushed by 1965, but Peru's internal strife would only accelerate until its climax in the 1990s.

The military has been prominent in Peruvian history. Coups have repeatedly interrupted civilian constitutional government. The most recent period of military rule (1968–1980) began when General Juan Velasco Alvarado

overthrew elected President Fernando Belaúnde Terry

of the Popular Action Party (AP). As part of what has been called the "first phase" of the military government's nationalist program, Velasco undertook an extensive agrarian reform program and nationalized the fish meal industry, some petroleum companies, and several banks and mining firms.

General Francisco Morales Bermúdez

replaced Velasco in 1975, citing Velasco's economic mismanagement and deteriorating health. Morales Bermúdez moved the revolution into a more conservative "second phase", tempering the radical measures of the first phase and beginning the task of restoring the country's economy.

A Constitutional Assembly was created in 1979, which was led by Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre

. Morales Bermúdez presided over the return to civilian government in accordance with a new constitution drawn up in 1979.

(Sendero Luminoso, SL) and the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement

(MRTA) increased during this time and derived significant financial support from alliances with the narcotraffickers, leading to the Internal conflict in Peru

.

In the May 1980 elections, President Fernando Belaúnde Terry

was returned to office by a strong plurality. One of his first actions as President was the return of several newspapers to their respective owners. In this way, freedom of speech

once again played an important part in Peruvian politics. Gradually, he also attempted to undo some of the most radical effects of the Agrarian Reform initiated by Velasco, and reversed the independent stance that the Military Government of Velasco had with the United States.

Belaúnde's second term was also marked by the unconditional support for Argentine

forces during the Falklands War

with the United Kingdom in 1982. Belaúnde declared that "Peru was ready to support Argentina with all the resources it needed." This included a number of fighter planes and possibly personnel from the Peruvian Air Force

, as well as ships, and medical teams. Belaunde's government proposed a peace settlement between the two countries, but it was rejected by both sides, as both claimed undiluted sovereignty of the territory. In response to Chile

's support of the UK, Belaúnde called for Latin American unity.

The nagging economic problems left over from the previous military government persisted, worsened by an occurrence of the "El Niño" weather phenomenon in 1982–83, which caused widespread flooding in some parts of the country, severe droughts in others, and decimated the schools of ocean fish that are one of the country's major resources. After a promising beginning, Belaúnde's popularity eroded under the stress of inflation, economic hardship, and terrorism.

In 1985, the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance

(APRA) won the presidential election, bringing Alan García to office. The transfer of the presidency from Belaúnde to García on July 28, 1985, was Peru's first exchange of power from one democratically elected leader to another for the first time in 40 years.

With a parliamentary majority for the first time in APRA's history, Alan García started his administration with hopes for a better future. However, economic mismanagement led to hyperinflation

from 1988 to 1990. García's term in office was marked by bouts of hyperinflation, which reached 7,649% in 1990 and had a cumulative total of 2,200,200% between July 1985 and July 1990, thereby profoundly destabilizing the Peruvian economy.

Owing to such chronic inflation, the Peruvian currency, the sol

, was replaced by the Inti in mid-1985, which itself was replaced the nuevo sol

("new sun") in July 1991, at which time the new sol had a cumulative value of one billion old soles. During his administration, the per capita annual income of Peruvians fell to $720 (below the level of 1960) and Peru's Gross Domestic Product

dropped 20%. By the end of his term, national reserves were a negative $900 million.

The economic turbulence of the time acerbated social tensions in Peru and partly contributed to the rise of the violent rebel movement Shining Path

. The García administration unsuccessfully sought a military solution to the growing terrorism, committing human rights violations which are still under investigation.

Concerned about the economy, the increasing terrorist threat from Sendero Luminoso and MRTA, and allegations of official corruption, voters chose a relatively unknown mathematician-turned-politician, Alberto Fujimori

, as president in 1990. The first round of the election was won by well-known writer Mario Vargas Llosa

, a conservative candidate who went on to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2010, but Fujimori defeated him in the second round. Fujimori implemented drastic measures that caused inflation to drop from 7,650% in 1990 to 139% in 1991. Faced with opposition to his reform efforts, Fujimori dissolved Congress in the auto-golpe of April 5, 1992. He then revised the constitution; called new congressional elections; and implemented substantial economic reform, including privatization of numerous state-owned companies, creation of an investment-friendly climate, and sound management of the economy.

Fujimori's administration was dogged by several insurgent groups, most notably Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), which carried on a terrorist campaign in the countryside throughout the 1980s and 1990s. He cracked down on the insurgents and was successful in largely quelling them by the late 1990s, but the fight was marred by atrocities committed by the both Peruvian security forces and the insurgents: the Barrios Altos massacre

and La Cantuta massacre

by Government paramilitary groups, and the bombings of Tarata

and Frecuencia Latina

by Shining Path

. Those examples subsequently came to be seen as symbols of the human rights violations committed during the last years of violence. With the capture of Abimael Guzmán

(known as President Gonzalo) in September 1992, the Shining Path received a severe blow which practically destroyed the organization.

In December 1996, a group of insurgents belonging to the MRTA

took over the Japanese embassy in Lima

, taking 72 people hostage. Military commandos stormed the embassy compound in May 1997, which resulted in the death of all 15 hostage takers, one hostage, and 2 commandos. It later emerged, however, that Fujimori's security chief Vladimiro Montesinos

may have ordered the killing of at least eight of the rebels after they surrendered.

Fujimori's constitutionally questionable decision to seek a third term and subsequent tainted victory in June 2000 brought political and economic turmoil. A bribery scandal that broke just weeks after he took office in July forced Fujimori to call new elections in which he would not run. The scandal involved Vladimiro Montesinos, who was shown in a video broadcast on TV bribing a politician to change sides. Montesinos subsequently emerged as the center a vast web of illegal activities, including embezzlement, graft, drug trafficking, as well as human rights violations committed during the war against Sendero Luminoso.

In November 2000, Fujimori resigned from office and went to Japan in self-imposed exile, avoiding prosecution for human rights violations and corruption charges by the new Peruvian authorities. His main intelligence chief, Vladimiro Montesinos

, fled Peru shortly afterwards. Authorities in Venezuela arrested him in Caracas in June 2001 and turned him over to Peruvian authorities; he is now imprisoned and charged with acts of corruption and human rights violations committed during Fujimori's administration.

A caretaker government presided over by Valentín Paniagua took on the responsibility of conducting new presidential and congressional elections. The elections were held in April 2001; observers considered them to be free and fair. Alejandro Toledo

(who led the opposition against Fujimori) defeated former President Alan García.

The newly elected government took office on July 28, 2001. The Toledo Administration managed to restore some degree of democracy to Peru following the authoritarianism and corruption that plagued both the Fujimori and García governments. Innocents wrongfully tried by military courts during the war against terrorism (1980–2000) were allowed to receive new trials in civilian courts.

On August 28, 2003, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

(CVR), which had been charged with studying the roots of the violence of the 1980–2000 period, presented its formal report to the President.

President Toledo was forced to make a number of cabinet changes, mostly in response to personal scandals. Toledo's governing coalition had a minority of seats in Congress and had to negotiate on an ad hoc

basis with other parties to form majorities on legislative proposals. Toledo's popularity in the polls suffered throughout the last years of his regime, due in part to family scandals and in part to dissatisfaction amongst workers with their share of benefits from Peru's macroeconomic success. After strikes by teachers and agricultural producers led to nationwide road blockages in May 2003, Toledo declared a state of emergency that suspended some civil liberties and gave the military power to enforce order in 12 regions. The state of emergency was later reduced to only the few areas where the Shining Path was operating.

On July 28, 2006 former president Alan García became the current President of Peru. He won the 2006 elections after winning in a runoff against Ollanta Humala

.

In May 2008, President García was a signatory to the The UNASUR Constitutive Treaty of the Union of South American Nations. Peru has ratified the treaty.

On June 5, 2011, Ollanta Humala was elected President in a run-off against Keiko Fujimori

, the daughter of Alberto Fujimori and former First Lady

of Peru, in the 2011 elections, making him the first leftist president of Peru since Juan Velasco Alvarado

.

About 15,200 years ago, groups of people are believed to have crossed the Bering Strait

Bering Strait

The Bering Strait , known to natives as Imakpik, is a sea strait between Cape Dezhnev, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia, the easternmost point of the Asian continent and Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, USA, the westernmost point of the North American continent, with latitude of about 65°40'N,...

from Asia and survived as nomads, hunting, gathering fruits and vegetables and fishing in the sea, rivers and lakes. Peruvian territory was home to the Norte Chico civilization

Norte Chico civilization

The Norte Chico civilization was a complex pre-Columbian society that included as many as 30 major population centers in what is now the Norte Chico region of north-central coastal Peru...

, one of the six oldest in the world, and to the Inca Empire

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire, or Inka Empire , was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political and military center of the empire was located in Cusco in modern-day Peru. The Inca civilization arose from the highlands of Peru sometime in the early 13th century...

, the largest state in Pre-Columbian

Pre-Columbian

The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic period to European colonization during...

America. It was conquered by the Spanish Empire

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

in the 16th century, which established a Viceroyalty

Viceroyalty of Peru

Created in 1542, the Viceroyalty of Peru was a Spanish colonial administrative district that originally contained most of Spanish-ruled South America, governed from the capital of Lima...

with jurisdiction over most of its South American domains. The nation declared independence

Independence of Peru

The Peruvian War of Independence was a series of military conflicts beginning in 1809 that culminated in the proclamation of the independence of Peru by José de San Martín on July 28, 1821. During the previous decade Peru had been a stronghold for royalists, who fought those in favor of...

from Spain in 1821 butt consolidated only after the Battle of Ayacucho

Battle of Ayacucho

The Battle of Ayacucho was a decisive military encounter during the Peruvian War of Independence. It was the battle that sealed the independence of Peru, as well as the victory that ensured independence for the rest of South America...

, three years later.

Pre-Columbian cultures

Hunting tools dating back to more than 11,000 years have been found in the caves in Pachacamac, Telarmachay, Junin and Lauricocha. Some of the oldest civilizations appeared circaCirca

Circa , usually abbreviated c. or ca. , means "approximately" in the English language, usually referring to a date...

6000 BC in the coastal provinces of Chilca

Chilca

Chilca was a rocket launch site in Peru at , near to Lima. Chilca was in service from 1974 and 1983 and was mainly used for launching Arcas and Nike rockets....

and Paracas

Paracas

Paracas may refer to:* Paracas culture, an important Andean society that existed in Peru between approximately 750 BC and 100 AD* Paracas Peninsula, located in the Ica Region of Peru* Paracas Bay, located in the Pisco Province of the Ica Region in Peru...

, and in the highland province of Callejón de Huaylas

Callejón de Huaylas

The Santa Valley is a inter-andean valley in the Ancash Region in the north-central highlands of Peru. Due to its location between two mountain ranges it is known as Callejón de Huaylas —Alley of Huaylas—, whereas Huaylas refers to the name of the territorial division's name during the Viceroyalty...

. Over the following three thousand years, inhabitants switched from nomadic lifestyles to cultivating land, as evidence from sites such as Jiskairumoko

Jiskairumoko

Jiskairumoko is a pre-Columbian archaeological site south east of Puno, Peru. The site lies at 4,115 meters , in the Aymara community of Jachacachi, adjacent to the Ilave River drainage, of the Lake Titicaca Basin, Peru...

, Kotosh

Kotosh

Kotosh is an archaeological site near Huanuco containing a temple of the Late Archaic period. The site gave name to the Kotosh Religious Tradition, which existed in Peru in 2300—1200 BCE, i.e. in the Late Archaic period...

, and Huaca Prieta

Huaca Prieta

Huaca Prieta is the site of a prehistoric coastal settlement in the Chicama valley, Peru. Consisting of a huge midden mound, it was first excavated by Junius B. Bird in 1946–1947. The site is the remains of a pre-pottery culture that lived here from 3,100–1,300 BCE. The remains include a number of...

demonstrates. Cultivation of plants such as corn

Maize

Maize known in many English-speaking countries as corn or mielie/mealie, is a grain domesticated by indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica in prehistoric times. The leafy stalk produces ears which contain seeds called kernels. Though technically a grain, maize kernels are used in cooking as a vegetable...

and cotton

Gossypium

Gossypium is the cotton genus. It belongs to the tribe Gossypieae, in the mallow family, Malvaceae, native to the tropical and subtropical regions from both the Old and New World. The genus Gossypium comprises around 50 species , making it the largest in species number in the tribe Gosssypioieae....

(Gossypium barbadense) began, as well as the domestication of animals such as the wild ancestors of the llama

Llama

The llama is a South American camelid, widely used as a meat and pack animal by Andean cultures since pre-Hispanic times....

, the alpaca

Alpaca

An alpaca is a domesticated species of South American camelid. It resembles a small llama in appearance.Alpacas are kept in herds that graze on the level heights of the Andes of southern Peru, northern Bolivia, Ecuador, and northern Chile at an altitude of to above sea level, throughout the year...

, and the guinea pig

Guinea pig

The guinea pig , also called the cavy, is a species of rodent belonging to the family Caviidae and the genus Cavia. Despite their common name, these animals are not in the pig family, nor are they from Guinea...

. Inhabitants practiced spinning

Spinning (textiles)

Spinning is a major industry. It is part of the textile manufacturing process where three types of fibre are converted into yarn, then fabric, then textiles. The textiles are then fabricated into clothes or other artifacts. There are three industrial processes available to spin yarn, and a...

and knitting

Knitting

Knitting is a method by which thread or yarn may be turned into cloth or other fine crafts. Knitted fabric consists of consecutive rows of loops, called stitches. As each row progresses, a new loop is pulled through an existing loop. The active stitches are held on a needle until another loop can...

of cotton and wool, basketry

Basket weaving

Basket weaving is the process of weaving unspun vegetable fibres into a basket or other similar form. People and artists who weave baskets are called basketmakers and basket weavers.Basketry is made from a variety of fibrous or pliable materials•anything that will bend and form a shape...

, and pottery

Pottery

Pottery is the material from which the potteryware is made, of which major types include earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. The place where such wares are made is also called a pottery . Pottery also refers to the art or craft of the potter or the manufacture of pottery...

.

As these inhabitants became sedentary, farming allowed them to build settlements and new societies emerged along the coast and in the Andean mountains. The first known city in all of the Americas was Caral

Caral

Caral was a large settlement in the Supe Valley, near Supe, Barranca province, Peru, some 200 km north of Lima. Caral is the most ancient city of the Americas, and is a well-studied site of the Caral civilization or Norte Chico civilization.- History :...

, located in the Supe Valley 200 km north of Lima. It is the oldest city in America and was built in approximately 2500 BC.

What is left from the civilization, also called Norte Chico

Norte Chico

Norte Chico or Near North Coast ranges over five river valleys north of present-day Lima: the Chancay River, the Huaura River, Supe River, Fortaleza River and Pativilca River....

, are about 30 pyramidical structures built up in receding terraces ending in a flat roof; some of them measured up to 20 meters in height. Caral is one of six world centers of the rise of civilization.

In the early 21st century, archeologists have discovered new evidence of ancient pre-Ceramic complex cultures. In 2005 Tom D. Dillehay and his team announced the discovery of three irrigation

Irrigation

Irrigation may be defined as the science of artificial application of water to the land or soil. It is used to assist in the growing of agricultural crops, maintenance of landscapes, and revegetation of disturbed soils in dry areas and during periods of inadequate rainfall...

canal

Canal

Canals are man-made channels for water. There are two types of canal:#Waterways: navigable transportation canals used for carrying ships and boats shipping goods and conveying people, further subdivided into two kinds:...

s that were 5400 years old, and a possible fourth that is 6700 years old, all in the Zaña Valley in northern Peru, evidence of community activity to support improved agriculture at a much earlier date than previously believed. In 2006, Robert Benfer and a research team discovered a 4200-year-old observatory

Observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geology, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed...

at Buena Vista

Buena Vista

Buena Vista, meaning "good view" in Spanish, may refer to:*Buena Vista , a Walt Disney trademark*Buena Vista Social Club , a Cuban music club plus an album and film inspired by the club...

, a site in the Andes several kilometers north of present-day Lima

Lima

Lima is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín rivers, in the central part of the country, on a desert coast overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Together with the seaport of Callao, it forms a contiguous urban area known as the Lima...

. They believe the observatory was related to the society's reliance on agriculture and understanding the seasons. The site includes the oldest three-dimensional sculptures found thus far in South America. In 2007 the archeologist Walter Alva

Walter Alva

Walter Alva , full name is Walter Alva Alva, is a Peruvian archaeologist, specializing in the study and excavation of the prehistoric Moche culture. Alva is noted for two major finds: the tomb of the Lord of Sipan and related people in 1987, and 2007.-Early life and education:Alva was born on 28...

and his team found a 4000-year-old temple with painted murals at Ventarrón

Ventarron

Ventarrón is the site of a 4,000-year old temple with painted murals, which was excavated in Peru in 2007 in the Lambayeque region on the northern coast, north of Peru's capital of Lima...

, in the northwest Lambayeque

Lambayeque Region

Lambayeque is a region in northwestern Peru known for its rich Moche and Chimú historical past. The region's name originates from the ancient pre-Inca civilization of the Lambayeque.-Etymology:...

region. The temple contained ceremonial offerings gained from exchange with Peruvian jungle societies, as well as those from the Ecuador

Ecuador

Ecuador , officially the Republic of Ecuador is a representative democratic republic in South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and by the Pacific Ocean to the west. It is one of only two countries in South America, along with Chile, that do not have a border...

an coast. Such finds show sophisticated, monumental construction requiring large-scale organization of labor, suggesting that hierarchical, complex cultures arose in South America much earlier than scholars had thought.

Chavin

Chavin may refer to:* Chavín culture, an early culture of the Andean region, pre-dating the Moche culture in Peru* Chavín de Huantar, an archaeological site built by the Chavín culture* Chavin, Indre, a commune of the Indre département in France...

, Paracas, Lima

Lima

Lima is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón, Rímac and Lurín rivers, in the central part of the country, on a desert coast overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Together with the seaport of Callao, it forms a contiguous urban area known as the Lima...

, Nasca, Moche

Moche

'The Moche civilization flourished in northern Peru from about 100 AD to 800 AD, during the Regional Development Epoch. While this issue is the subject of some debate, many scholars contend that the Moche were not politically organized as a monolithic empire or state...

, Tiwanaku

Tiwanaku

Tiwanaku, is an important Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia, South America. Tiwanaku is recognized by Andean scholars as one of the most important precursors to the Inca Empire, flourishing as the ritual and administrative capital of a major state power for approximately five...

, Wari

Wari

Wari may refer to:*Wari', Amerindian nation**Wari’ language, spoken by Wari'*Wari culture, Middle Horizon civilization that flourished in Peru*Wari Empire, political formation that emerged around AD500 in Peru...

, Lambayeque

Lambayeque Region

Lambayeque is a region in northwestern Peru known for its rich Moche and Chimú historical past. The region's name originates from the ancient pre-Inca civilization of the Lambayeque.-Etymology:...

, Chimu, Chan Chan

Chan Chan

The largest Pre-Columbian city in South America, Chan Chan is an archaeological site located in the Peruvian region of La Libertad, five km west of Trujillo. Chan Chan covers an area of approximately 20 km² and had a dense urban center of about 6km²...

, and Chincha

Chincha

The Chincha were a Native American people of the Andes. They are discussed by Maria Rostworowski de Diez Canseco in "History of the Inca Realm" and by Justo Caceres Macedo in "Prehispanic Cultures of Peru"...

, among others. The Paracas culture

Paracas culture

The Paracas culture was an important Andean society between approximately 800 BCE and 100 BCE, with an extensive knowledge of irrigation and water management. It developed in the Paracas Peninsula, located in what today is the Paracas District of the Pisco Province in the Ica Region...

emerged on the southern coast around 300 BC. They are known for their use of vicuña

Vicuña

The vicuña or vicugna is one of two wild South American camelids, along with the guanaco, which live in the high alpine areas of the Andes. It is a relative of the llama, and is now believed to share a wild ancestor with domesticated alpacas, which are raised for their fibre...

fibers instead of just cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

to produce fine textile

Textile

A textile or cloth is a flexible woven material consisting of a network of natural or artificial fibres often referred to as thread or yarn. Yarn is produced by spinning raw fibres of wool, flax, cotton, or other material to produce long strands...

s—innovations that did not reach the northern coast of Peru until centuries later. Coastal cultures such as the Moche

Moche

'The Moche civilization flourished in northern Peru from about 100 AD to 800 AD, during the Regional Development Epoch. While this issue is the subject of some debate, many scholars contend that the Moche were not politically organized as a monolithic empire or state...

and Nazca

Nazca

Nazca is a system of valleys on the southern coast of Peru, and the name of the region's largest existing town in the Nazca Province. It is also the name applied to the Nazca culture that flourished in the area between 300 BC and AD 800...

flourished from about 100 BC to about AD 700: the Moche produced impressive metalwork, as well as some of the finest pottery

Pottery

Pottery is the material from which the potteryware is made, of which major types include earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. The place where such wares are made is also called a pottery . Pottery also refers to the art or craft of the potter or the manufacture of pottery...

seen in the ancient world, while the Nazca are known for their textiles and the enigmatic Nazca lines

Nazca Lines

The Nazca Lines are a series of ancient geoglyphs located in the Nazca Desert in southern Peru. They were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994. The high, arid plateau stretches more than between the towns of Nazca and Palpa on the Pampas de Jumana about 400 km south of Lima...

.

These coastal cultures eventually began to decline as a result of recurring el Niño floods and droughts. In consequence, the Huari and Tiwanaku

Tiwanaku

Tiwanaku, is an important Pre-Columbian archaeological site in western Bolivia, South America. Tiwanaku is recognized by Andean scholars as one of the most important precursors to the Inca Empire, flourishing as the ritual and administrative capital of a major state power for approximately five...

, who dwelt inland in the Andes

Andes

The Andes is the world's longest continental mountain range. It is a continual range of highlands along the western coast of South America. This range is about long, about to wide , and of an average height of about .Along its length, the Andes is split into several ranges, which are separated...

became the predominant cultures of the region encompassing much of modern-day Peru and Bolivia

Bolivia

Bolivia officially known as Plurinational State of Bolivia , is a landlocked country in central South America. It is the poorest country in South America...

. They were succeeded by powerful city-state

City-state

A city-state is an independent or autonomous entity whose territory consists of a city which is not administered as a part of another local government.-Historical city-states:...

s, such as Chancay

Chancay

Chancay is a small city in the Lima Region of Peru. Its population is 26,958....

, Sipan

Sipán

Sipán is a Moche archaeological site in northern Peru that is famous for the tomb of El Señor de Sipán , excavated by Walter Alva and his wife Susana Meneses. It is considered to be one of the most important archaeological discoveries in the last 30 years, because the main tomb was found intact...

, and Cajamarca

Cajamarca

Cajamarca may refer to:Colombia*Cajamarca, Tolima a town and municipality in Tolima DepartmentPeru* Cajamarca, city in Peru.* Cajamarca District, district in the Cajamarca province.* Cajamarca Province, province in the Cajamarca region....

, and two empires: Chimor

Chimor

Chimor was the political grouping of the Chimú culture that ruled the northern coast of Peru, beginning around 850 AD and ending around 1470 AD. Chimor was the largest kingdom in the Late Intermediate period, encompassing 1,000 km of coastline...

and Chachapoyas culture

Chachapoyas culture

The Chachapoyas, also called the Warriors of the Clouds, were an Andean people living in the cloud forests of the Amazonas region of present-day Peru. The Incas conquered their civilization shortly before the arrival of the Spanish in Peru. When the Spanish arrived in Peru in the 16th century, the...

These cultures developed relatively advanced techniques of cultivation

Tillage

Tillage is the agricultural preparation of the soil by mechanical agitation of various types, such as digging, stirring, and overturning. Examples of human-powered tilling methods using hand tools include shovelling, picking, mattock work, hoeing, and raking...

, gold and silver craft, pottery

Pottery

Pottery is the material from which the potteryware is made, of which major types include earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. The place where such wares are made is also called a pottery . Pottery also refers to the art or craft of the potter or the manufacture of pottery...

, metallurgy

Metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their intermetallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are called alloys. It is also the technology of metals: the way in which science is applied to their practical use...

, and knitting

Knitting

Knitting is a method by which thread or yarn may be turned into cloth or other fine crafts. Knitted fabric consists of consecutive rows of loops, called stitches. As each row progresses, a new loop is pulled through an existing loop. The active stitches are held on a needle until another loop can...

. Around 700 BC, they appear to have developed systems of social organization that were the precursors of the Inca

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire, or Inka Empire , was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political and military center of the empire was located in Cusco in modern-day Peru. The Inca civilization arose from the highlands of Peru sometime in the early 13th century...

civilization.

Not all Andean cultures were willing to offer their loyalty to the Incas as the Incas expanded their empire, and many were openly hostile. The people of the Chachapoyas culture

Chachapoyas culture

The Chachapoyas, also called the Warriors of the Clouds, were an Andean people living in the cloud forests of the Amazonas region of present-day Peru. The Incas conquered their civilization shortly before the arrival of the Spanish in Peru. When the Spanish arrived in Peru in the 16th century, the...

were an example of this, but the Inca eventually conquered and integrated them into their empire.

Inca Empire (1438–1532)

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire, or Inka Empire , was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political and military center of the empire was located in Cusco in modern-day Peru. The Inca civilization arose from the highlands of Peru sometime in the early 13th century...

built the largest empire and dynasty of pre-Columbian America

Pre-Columbian

The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic period to European colonization during...

. The Tahuantinsuyo—which is derived from Quechua

Quechua languages

Quechua is a Native South American language family and dialect cluster spoken primarily in the Andes of South America, derived from an original common ancestor language, Proto-Quechua. It is the most widely spoken language family of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, with a total of probably...

for "The Four United Regions"—reached its greatest extension at the beginning of the 16th century. It dominated a territory that included (from north to south): Ecuador

Ecuador

Ecuador , officially the Republic of Ecuador is a representative democratic republic in South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and by the Pacific Ocean to the west. It is one of only two countries in South America, along with Chile, that do not have a border...

, part of Colombia

Colombia

Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia , is a unitary constitutional republic comprising thirty-two departments. The country is located in northwestern South America, bordered to the east by Venezuela and Brazil; to the south by Ecuador and Peru; to the north by the Caribbean Sea; to the...

, the northern half of Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

, and the north-west part of Argentina

Argentina

Argentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

; and from east to west, from Bolivia

Bolivia

Bolivia officially known as Plurinational State of Bolivia , is a landlocked country in central South America. It is the poorest country in South America...

to the Amazonian forests

Amazon Rainforest

The Amazon Rainforest , also known in English as Amazonia or the Amazon Jungle, is a moist broadleaf forest that covers most of the Amazon Basin of South America...

and Peru

Peru

Peru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

.

The empire originated from a tribe based in Cuzco, which became the capital. Pachacuti was the first ruler to considerably expand the boundaries of the Cuzco state. His offspring later ruled an empire by both violent and peaceful conquest.

In Cuzco, the royal city was created to resemble a Cougar; the head, the main royal structure, formed what is now known as Sacsayhuaman. The Empire's administrative, political, and military center was located in Cuzco. The empire was divided into four quarters: Chinchasuyo, Antisuyo, Contisuyo, and Collasuyo.

Quechua

Quechua languages

Quechua is a Native South American language family and dialect cluster spoken primarily in the Andes of South America, derived from an original common ancestor language, Proto-Quechua. It is the most widely spoken language family of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, with a total of probably...

was the official language, imposed on the citizens. It was the language of a neighbouring tribe of the original tribe of the empire. Conquered populations—tribes, kingdoms, states, and cities—were allowed to practice their own religions and lifestyles, but had to recognize Inca cultural practices as superior to their own. Inti, the sun god, was to be worshipped as one of the most important gods of the empire. His representation on earth was the Inca ("Emperor").

The Tahuantinsuyo was organized in dominions with a stratified society, in which the ruler was the Inca. It was also supported by an economy based on the collective property of the land. In fact, the Inca Empire

Inca Empire

The Inca Empire, or Inka Empire , was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political and military center of the empire was located in Cusco in modern-day Peru. The Inca civilization arose from the highlands of Peru sometime in the early 13th century...

was conceived like an ambitious and audacious civilizing project, based on a mythical thought, in which the harmony of the relationships between the human being, nature, and gods

Inca mythology

Inca mythology includes many stories and legends that are mythological and helps to explain or symbolizes Inca beliefs.All those that followed the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire by Francisco Pizarro burned the records of the Inca culture...

was truly essential.

Many interesting customs were observed, for example the extravagant feast of Inti Raymi which gave thanks to the God Sun, and the young women who were the Virgins of the Sun, sacrificial virgins devoted to the Inti. The empire, being quite large, also had an impressive transportation system of roads to all points of the empire called the Inca Trail

Inca road system

The Inca road system was the most extensive and advanced transportation system in pre-Columbian South America. The network was based on two north-south roads with numerous branches. The best known portion of the road system is the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu...

, and chasquis, message carriers who relayed information from anywhere in the empire to Cuzco.

Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu is a pre-Columbian 15th-century Inca site located above sea level. It is situated on a mountain ridge above the Urubamba Valley in Peru, which is northwest of Cusco and through which the Urubamba River flows. Most archaeologists believe that Machu Picchu was built as an estate for...

(Quechua: Old Peak; sometimes called the "Lost City of the Incas") is a well-preserved pre-Columbian Inca ruin located on a high mountain ridge above the Urubamba Valley, about 70 km (44 mi) northwest of Cuzco. Elevation measurements vary depending on whether the data refers to the ruin or the extremity of the mountain; Machu Picchu tourist information reports the elevation as 2,350 m (7,711 ft)[1]. Forgotten for centuries by the outside world, although not by locals, it was brought back to international attention by Yale archaeologist Hiram Bingham III

Hiram Bingham III

Hiram Bingham, formally Hiram Bingham III, was an academic, explorer, treasure hunter and politician from the United States. He made public the existence of the Quechua citadel of Machu Picchu in 1911 with the guidance of local indigenous farmers...

, who rediscovered it in 1911 and wrote a best-selling work about it. Peru is pursuing legal efforts to retrieve thousands of artifacts that Bingham removed from the site.

Although Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu is a pre-Columbian 15th-century Inca site located above sea level. It is situated on a mountain ridge above the Urubamba Valley in Peru, which is northwest of Cusco and through which the Urubamba River flows. Most archaeologists believe that Machu Picchu was built as an estate for...

is by far the most well-known internationally, Peru boasts many other sites where the modern visitor can see extensive and well-preserved ruins, remnants of the Inca-period and even older constructions. Much of the Inca architecture and stonework found at these sites continues to confound archaeologists. For example, at Sacsayhuaman, in Cuzco, the zig-zag-shaped walls are composed of massive boulders fitted very precisely to one another's irregular, angular shapes. No mortar holds them together, but nonetheless they have remained absolutely solid through the centuries, surviving earthquakes that flattened many of Cuzco's colonial constructions. Damage to the walls visible today was mainly inflicted during battles between the Spanish and the Inca, as well as later, in the colonial era. As Cuzco grew, Sacsayhuaman's walls were partially dismantled, the site becoming a convenient source of construction materials for the city's newer inhabitants. Today we not only do not know how these stones were shaped and smoothed, lifted on top of one another (they really are very massive) or fitted together by the Incas; we also don't know how they started got the stones to the site in the first place. The stone used is not native to the area, and most likely came from mountains many miles away.

Conquest of Peru (1532–1572)

| The etymology of Peru: The word Peru may be derived from Birú, the name of a local ruler who lived near the Bay of San Miguel Bay of San Miguel The Bay of San Miguel is located on the Pacific coast of Darién, a district of eastern Panama. Bay is located at . It is fed by the Tuira River. At its southern end is Cape Garachiné , and at its northern end is Punta San Lorenzo .... , Panama Panama Panama , officially the Republic of Panama , is the southernmost country of Central America. Situated on the isthmus connecting North and South America, it is bordered by Costa Rica to the northwest, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. The... , in the early 16th century. When his possessions were visited by Spanish explorers in 1522, they were the southernmost part of the New World yet known to Europeans. Thus, when Francisco Pizarro Francisco Pizarro Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess was a Spanish conquistador, conqueror of the Incan Empire, and founder of Lima, the modern-day capital of the Republic of Peru.-Early life:... explored the regions farther south, they came to be designated Birú or Peru. An alternative history is provided by the contemporary writer Inca Garcilasco de la Vega, son of an Inca princess and a conquistador. He says the name Birú was that of a common Indian happened upon by the crew of a ship on an exploratory mission for governor Pedro Arias de Ávila, and goes on to relate many more instances of misunderstandings due to the lack of a common language. The Spanish Crown Spanish Empire The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power.... gave the name legal status with the 1529 Capitulación de Toledo, which designated the newly encountered Inca Empire Inca Empire The Inca Empire, or Inka Empire , was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The administrative, political and military center of the empire was located in Cusco in modern-day Peru. The Inca civilization arose from the highlands of Peru sometime in the early 13th century... as the province of Peru. Under Spanish rule, the country adopted the denomination Viceroyalty of Peru Viceroyalty of Peru Created in 1542, the Viceroyalty of Peru was a Spanish colonial administrative district that originally contained most of Spanish-ruled South America, governed from the capital of Lima... , which became Republic of Peru after independence. |

When the Spanish

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

landed in 1531, Peru

Peru

Peru , officially the Republic of Peru , is a country in western South America. It is bordered on the north by Ecuador and Colombia, on the east by Brazil, on the southeast by Bolivia, on the south by Chile, and on the west by the Pacific Ocean....

's territory was the nucleus of the highly developed Inca civilization. Centered at Cuzco

Cusco

Cusco , often spelled Cuzco , is a city in southeastern Peru, near the Urubamba Valley of the Andes mountain range. It is the capital of the Cusco Region as well as the Cuzco Province. In 2007, the city had a population of 358,935 which was triple the figure of 20 years ago...

, the Inca Empire extended over a vast region, stretching from northern Ecuador

Ecuador

Ecuador , officially the Republic of Ecuador is a representative democratic republic in South America, bordered by Colombia on the north, Peru on the east and south, and by the Pacific Ocean to the west. It is one of only two countries in South America, along with Chile, that do not have a border...

to central Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

.

Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess was a Spanish conquistador, conqueror of the Incan Empire, and founder of Lima, the modern-day capital of the Republic of Peru.-Early life:...

and his brothers were attracted by the news of a rich and fabulous kingdom. In 1532, they arrived in the country, which they called Peru. (The forms Biru, Pirú, and Berú are also seen in early records.) According to Raúl Porras Barrenechea

Raúl Porras Barrenechea

Raúl Porras Barrenechea was a Peruvian historian. He was born in Pisco, Peru on March 23, 1897 and died in Lima, Peru on September 27, 1960. He was a teacher at the Anglo-Peruvian School. As a student during the 1950s Mario Vargas Llosa worked with Porras for four and one-half years and learned a...

, Peru is not a Quechua

Quechua languages

Quechua is a Native South American language family and dialect cluster spoken primarily in the Andes of South America, derived from an original common ancestor language, Proto-Quechua. It is the most widely spoken language family of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, with a total of probably...

n nor Caribbean

Caribbean Spanish

Caribbean Spanish is the general name of the Spanish dialects spoken in the Caribbean region. It closely resembles the Spanish spoken in the Canary Islands and Andalusia....

word, but Indo-Hispanic or hybrid.

In the years between 1524 and 1526 smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease unique to humans, caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor. The disease is also known by the Latin names Variola or Variola vera, which is a derivative of the Latin varius, meaning "spotted", or varus, meaning "pimple"...

, introduced from Panama and preceding the Spanish conquerors swept through the Inca Empire. The death of the Incan ruler Huayna Capac

Huayna Capac

Huayna Capac was the eleventh Sapa Inca of the Inca Empire and sixth of the Hanan dynasty. He was the successor to Tupac Inca Yupanqui.-Name:In Quechua, his name is spelled Wayna Qhapaq, and in Southern Quechua, it is Vaina Ghapakh...

as well as most of his family including his heir, caused the fall of the Incan political structure and contributed to the civil war

Inca Civil War

The Inca Civil War, the Inca Dynastic War, the Inca War of Succession, or, sometimes, the War of the Two Brothers was fought between two brothers, Huáscar and Atahualpa, sons of Huayna Capac, over the succession to the Inca throne. The war followed Huayna Capac's death in 1527, although it did not...

between the brothers Atahualpa and Huáscar

Huáscar

Huáscar Inca was Sapa Inca of the Inca empire from 1527 to 1532 AD, succeeding his father Huayna Capac and brother Ninan Cuyochi, both of whom died of smallpox while campaigning near Quito.After the conquest, the Spanish put forth the idea that Huayna Capac may have...

. Taking advantage of this, Pizarro carried out a coup d'état

Coup d'état