September 1911

Encyclopedia

January

- February

- March

- April

- May

- June

- July

- August

- September - October

- November

- December

The following events occurred in September 1911

The following events occurred in September 1911

:

January 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in January 1911:-January 1, 1911 :...

- February

February 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in February 1911:-February 1, 1911 :...

- March

March 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in March 1911:-March 1, 1911 :...

- April

April 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in April 1911:-April 1, 1911 :...

- May

May 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in May 1911:-May 1, 1911 :...

- June

June 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in June 1911:-June 1, 1911 :*The Senate voted 48-20 to reopen the investigation of U.S...

- July

July 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in July 1911:-July 1, 1911 :...

- August

August 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in August 1911:-August 1, 1911 :...

- September - October

October 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in October 1911:-October 1, 1911 :...

- November

November 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in November 1911:-November 1, 1911 :*The first aerial bombardment in history took place when 2d.Lt...

- December

December 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in December 1911:-December 1, 1911 :...

September 1911

January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November - DecemberThe following events occurred in September 1911:-September 1, 1911 :*Emilio Estrada was inaugurated as the 23rd President of Ecuador...

:

September 1, 1911 (Friday)

- Emilio EstradaEmilio EstradaEmilio Estrada Carmona was President of Ecuador September 1-December 21, 1911....

was inaugurated as the 23rd President of Ecuador. He would die less than four months into his term. - Died: Bradford Lee Gilbert, 58, architect who designed the 13-story tall Tower Building, New York's first skyscraperSkyscraperA skyscraper is a tall, continuously habitable building of many stories, often designed for office and commercial use. There is no official definition or height above which a building may be classified as a skyscraper...

.

September 2, 1911 (Saturday)

- The Russian icebreaker ships TaymyrIcebreaker TaymyrIcebreaker Taymyr was an icebreaking steamer of 1200 tons built for the Russian Imperial Navy at St. Petersburg in 1909. It was named after the Taymyr Peninsula....

and VaygachIcebreaker VaygachIcebreaker Vaygach was an icebreaking steamer of moderate size built for the Russian Imperial Navy at St. Petersburg in 1909. It was named after Vaygach Island in the Russian Arctic....

landed at Wrangel IslandWrangel IslandWrangel Island is an island in the Arctic Ocean, between the Chukchi Sea and East Siberian Sea. Wrangel Island lies astride the 180° meridian. The International Date Line is displaced eastwards at this latitude to avoid the island as well as the Chukchi Peninsula on the Russian mainland...

as part of the coast of Antarctica, and claimed it for the Russian Empire. - João Pinheiro ChagasJoão Pinheiro ChagasJoão Pinheiro Chagas was a Portuguese journalist and politician. He was born in Brazil, from Portuguese parents who soon moved back to Portugal. He was an editor at the newspapers "O Primeiro de Janeiro", "Correio do Norte", "O Tempo" and "O Dia"...

became the new Prime Minister of Portugal. - A statue of Baron von Steuben, Hessian leader during the American Revolutionary War, was presented by U.S. Congressman Richard BartholdtRichard BartholdtRichard Bartholdt was a U.S. Representative from Missouri.Born in Schleiz, Germany, Bartholdt attended the public schools and Schleiz College ....

from the United States to Germany, and was unveiled at PotsdamPotsdamPotsdam is the capital city of the German federal state of Brandenburg and part of the Berlin/Brandenburg Metropolitan Region. It is situated on the River Havel, southwest of Berlin city centre....

by Kaiser Wilhelm II. - Born: William F. HarrahWilliam F. HarrahWilliam Fisk Harrah was an American businessman and the founder of Harrah's Hotel and Casinos.-Early years and education:...

, founder of Harrah's casino empire; in South Pasadena, CaliforniaSouth Pasadena, CaliforniaSouth Pasadena is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. As of the 2010 census, it had a population of 25,619, up from 24,292 at the 2000 census. It is located in in the West San Gabriel Valley...

(d. 1978) and Romare BeardenRomare BeardenRomare Bearden was an African American artist and writer. He worked in several media including cartoons, oils, and collage.-Education:...

, African-American painter, in Charlotte, North CarolinaCharlotte, North CarolinaCharlotte is the largest city in the U.S. state of North Carolina and the seat of Mecklenburg County. In 2010, Charlotte's population according to the US Census Bureau was 731,424, making it the 17th largest city in the United States based on population. The Charlotte metropolitan area had a 2009...

(d. 1988)

September 3, 1911 (Sunday)

- Agadir CrisisAgadir CrisisThe Agadir Crisis, also called the Second Moroccan Crisis, or the Panthersprung, was the international tension sparked by the deployment of the German gunboat Panther, to the Moroccan port of Agadir on July 1, 1911.-Background:...

: As the Kaiser and the Chancellor departed for Kiel for a display of German naval might, a crowd of 200,000 turned out for an anti-war rally at Treptower ParkTreptower ParkTreptower Park is a park along the river Spree in Alt-Treptow, in the district of Treptow-Köpenick, south of central Berlin. The park is a popular place for recreation of Berliners and a tourist attraction...

in BerlinBerlinBerlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

. Speakers from the Social DemocratsSocial Democratic Party of GermanyThe Social Democratic Party of Germany is a social-democratic political party in Germany...

, included August BebelAugust BebelFerdinand August Bebel was a German Marxist politician, writer, and orator. He is best remembered as one of the founders of the Social Democratic Party of Germany.-Early years:...

and Karl LiebknechtKarl Liebknechtwas a German socialist and a co-founder with Rosa Luxemburg of the Spartacist League and the Communist Party of Germany. He is best known for his opposition to World War I in the Reichstag and his role in the Spartacist uprising of 1919...

, who criticized Germany's aggressive moves in Morocco.

September 4, 1911 (Monday)

- A professional wrestlingProfessional wrestlingProfessional wrestling is a mode of spectacle, combining athletics and theatrical performance.Roland Barthes, "The World of Wrestling", Mythologies, 1957 It takes the form of events, held by touring companies, which mimic a title match combat sport...

match at Chicago's Comiskey Park attracted a sellout crowd of 30,000 people, pitting world champion Frank GotchFrank GotchFrank Alvin Gotch was an American professional wrestler of German ancestry, the first American to win the world heavyweight free-style championship, and credited for popularizing professional wrestling in the United States...

against George Hackenschmidt, from whom Gotch had won the title on April 3, 1908. The original bout had taken 2 hours. In the rematch, Gotch kept his title, defeating Hackenschmidt in 30 minutes. - Harriet QuimbyHarriet QuimbyHarriet Quimby was an early American aviator and a movie screenwriter. In 1911 she was awarded a U.S. pilot's certificate by the Aero Club of America, becoming the first woman to gain a pilot's license in the United States. In 1912 she became the first woman to fly across the English Channel...

won her first air race, receiving $1,500 at the Richmond County Fair on New York's Staten Island. - Delray Beach, FloridaDelray Beach, FloridaDelray Beach is a city in Palm Beach County, Florida, USA. As of the 2000 census, the city had a total population of 60,020. As of 2004, the population estimated by the U.S...

, population 250, became a city after its charter was approved by the 56 voters participating. A century later, the city population had grown to 65,000. - FranceFranceThe French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

's most powerful naval fleet ever, with 50 warships, was reviewed by President Armand FallièresArmand FallièresClément Armand Fallières was a French politician, president of the French republic from 1906 to 1913.He was born at Mézin in the département of Lot-et-Garonne, France, where his father was clerk of the peace...

at ToulonToulonToulon is a town in southern France and a large military harbor on the Mediterranean coast, with a major French naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur region, Toulon is the capital of the Var department in the former province of Provence....

. Théophile DelcasséThéophile DelcasséThéophile Delcassé was a French statesman.-Biography:He was born at Pamiers, in the Ariège département...

, the French Minister of the Navy, declared in a speech that "Their powder magazines are full, and all of them could be mobilized immediately." - Roland G. Garros broke the altitude record, flying to 4,250 meters (13,943 feet) at ParameParaméParamé is a former town and commune of France on the north coast of Britanny. The town merged with Saint-Servan into the commune of Saint-Malo in 1967. Paramé is now a quarter of Saint-Malo and its seaside resort. The city is known for its long sand beach and its sea spa....

, France.

September 5, 1911 (Tuesday)

- Reports of the flood that would drown 200,000 people were relayed to the world by Western missionaries, after China's Yangtze RiverYangtze RiverThe Yangtze, Yangzi or Cháng Jiāng is the longest river in Asia, and the third-longest in the world. It flows for from the glaciers on the Tibetan Plateau in Qinghai eastward across southwest, central and eastern China before emptying into the East China Sea at Shanghai. It is also one of the...

overflowed its banks. The American Mission at WuhuWuhuWuhu is a prefecture-level city in the southeastern Anhui province, People's Republic of China. Sitting on the southeast bank of the Yangtze River, Wuhu borders Xuancheng to the southeast, Chizhou and Tongling to the southwest, Chaohu to the northwest, Ma'anshan to the northeast, and the...

initially reported that 100,000 people had drowned in the Ngan-hwei (now AnhuiAnhuiAnhui is a province in the People's Republic of China. Located in eastern China across the basins of the Yangtze River and the Huai River, it borders Jiangsu to the east, Zhejiang to the southeast, Jiangxi to the south, Hubei to the southwest, Henan to the northwest, and Shandong for a tiny...

province) and that 95% of crops along the banks had been destroyed. . Followup reports were that the destruction extended from I-Chang (YichangYichangYichang is a prefecture-level city located in Hubei province of the People's Republic of China. It is the second largest city in Hubei province after the province capital, Wuhan. The Three Gorges Dam is located within its administrative area, in Yiling District.-History:In ancient times Yichang...

) in the Hu-peh (HubeiHubei' Hupeh) is a province in Central China. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Lake Dongting...

) province and down to ShanghaiShanghaiShanghai is the largest city by population in China and the largest city proper in the world. It is one of the four province-level municipalities in the People's Republic of China, with a total population of over 23 million as of 2010...

for 700 miles. Estimates of the number of people who died have been as high as 200,000 who drowned and another 100,000 who starved or were murdered during the subsequent famine. - The day after France showed of its 50 warships, Kaiser Wilhelm II reviewed a fleet of 99 warships of the German NavyGerman NavyThe German Navy is the navy of Germany and is part of the unified Bundeswehr .The German Navy traces its roots back to the Imperial Fleet of the revolutionary era of 1848 – 52 and more directly to the Prussian Navy, which later evolved into the Northern German Federal Navy...

at KielKielKiel is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 238,049 .Kiel is approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the north of Germany, the southeast of the Jutland peninsula, and the southwestern shore of the...

. The procession, which did not include three of the four Helgoland class battleshipHelgoland class battleshipThe Helgoland class was the second class of German dreadnought battleships. Constructed from 1908 to 1912, the class comprised four ships: , the lead ship; ; ; and . The design was a significant improvement over the previous ships; they had a larger main battery— main guns instead of the weapons...

s, was seen by American observers as proof that Germany had displaced the United States as having the second most powerful navy in the world (after the British Navy). - At the Battle of Imamzadeh Ja'farImamzadeh Ja'far, BorujerdImāmzādeh Ja‘far is a historical mausoleum in Borujerd, western Iran. The tomb contains the remains of Abulqāsim Ja’far ibn al-Husayn, grandson of the Shī‘ah Imam Ali ibn Hussayn.-History:...

, Persian troops successfully routed rebels seeking to restore the deposed Shah, Mohammed Ali Mirza, to the throne. The outcome was reported later to have been as a result of superior weapons, with the government forces using machine guns under the direction of German adviser Major Haas. Rebel leader Arshad ed Dowleh was captured, and executed the next day. Seized with him was a large amount of gold used by the ex-Shah, who fled with his remaining 7 followers to Gumesh Tepe at the border. - The first adult literacy program in the United States, when Cora Wilson Stewart, the school superintendent in Rowan County, KentuckyRowan County, KentuckyRowan County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of 2010, the population was 23,333. Its county seat is Morehead. The county was created in 1856 from adjacent counties originally part of Mason county, and named for John Rowan, who represented Kentucky in the U.S...

, began a program that she called the Moonlight Schools. The night classes at the county's 50 schools would take place as long as the Moon was bright enough for students to safely travel. She had expected that 150 adults might want to learn to read. Instead, 1,200 men and women signed up.

September 6, 1911 (Wednesday)

- Thomas W. Burgess became only the second person to swim across the English ChannelEnglish ChannelThe English Channel , often referred to simply as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the North Sea to the Atlantic. It is about long and varies in width from at its widest to in the Strait of Dover...

, and the first in 36 years, after Matthew WebbMatthew WebbCaptain Matthew Webb was the first recorded person to swim the English Channel without the use of artificial aids. On 25 August 1875 he swam from Dover to Calais in less than 22 hours.-Early life and career:...

had crossed on August 25, 1875. Burgess, who had failed in 15 prior attempts, arrived at Cape Grisnez on the French coast at 9:50 a.m., 22 hours and 35 minutes after setting off from South ForelandSouth ForelandSouth Foreland is a chalk headland on the Kent coast of southeast England. It presents a bold cliff to the sea, and commands views over the Strait of Dover. It is northeast of Dover and 15 miles south of North Foreland...

the day before. - Recently released from prison and exiled to Vologda, Joseph StalinJoseph StalinJoseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

(at the time Josif Dzhugashvili) made an illegal trip to Saint PetersburgSaint PetersburgSaint Petersburg is a city and a federal subject of Russia located on the Neva River at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea...

to link up with the Bolshevik organization. Stalin boarded a train with the identity papers of Pyotr Chizhikov, but the Okhrana police, arrested Chizhikov and alerted the Russian capital that Stalin was on the way. Stalin was captured three days later. - Born: Harry DanningHarry DanningHarry Danning, nicknamed Harry the Horse was a professional baseball player. He played his entire Major League Baseball career as a catcher for the New York Giants, and was considered one of the top defensive catchers of his era. He batted and threw right-handed...

, Jewish MLB player nicknamed "Harry the Horse", in Los AngelesLos ÁngelesLos Ángeles is the capital of the province of Biobío, in the commune of the same name, in Region VIII , in the center-south of Chile. It is located between the Laja and Biobío rivers. The population is 123,445 inhabitants...

(d. 2004) - Died: Katherine Cecil ThurstonKatherine Cecil ThurstonKatherine Cecil Thurston was an Irish novelist.-Life:She was born Katherine Cecil Madden in Cork, Ireland, the only daughter of banker Paul J. Madden and Catherine Madden...

, American novelist famous for The Masquerader; and Armand Cochefort, 61, French chief of detectives during the Dreyfus AffairDreyfus AffairThe Dreyfus affair was a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent...

.

September 7, 1911 (Thursday)

- French poet Guillaume ApollinaireGuillaume ApollinaireWilhelm Albert Włodzimierz Apolinary Kostrowicki, known as Guillaume Apollinaire was a French poet, playwright, short story writer, novelist, and art critic born in Italy to a Polish mother....

was arrested in Paris and charged with the theft of the Mona LisaMona LisaMona Lisa is a portrait by the Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci. It is a painting in oil on a poplar panel, completed circa 1503–1519...

, but released after a week. Pablo PicassoPablo PicassoPablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso known as Pablo Ruiz Picasso was a Spanish expatriate painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, and stage designer, one of the greatest and most influential artists of the...

was brought in for questioning by the police, but not detained. - The first U.S. Navy aviation unit was organized, with Lt. Theodore Gordon EllysonTheodore Gordon EllysonTheodore Gordon Ellyson, USN , nicknamed "Spuds", was the first United States Navy officer designated as an aviator . Ellyson served in the experimental development of aviation in the years before and after World War I. He also spent several years before the war as part of the Navy's new...

as its commanding officer. - PortugalPortugalPortugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

assembled 12,000 troops at its northern border to fend off a monarchist invasion. Airplane reconnaissance estimated that 5,000 rebels were concentrated at Orense. - Born: Todor ZhivkovTodor ZhivkovTodor Khristov Zhivkov was a communist politician and leader of the People's Republic of Bulgaria from March 4, 1954 until November 10, 1989....

, First Secretary of Bulgarian Communist Party 1954-1989, President 1971-1989; in PravetsPravetsPravets is a town in central western Bulgaria, located approximately 60 km from the capital Sofia.Pravets has a population of 4,512 people. Mountains surround it, which allows for a mild climate with rare winds. In the outskirts there is a small lake used for fishing and recreation...

(d. 1998) - Died: Professor Masuchika ShimoseShimose powderShimose powder was a type of explosive shell filling developed by the Japanese chemist Shimose Masachika . It was a form of picric acid used by France as melinite and by Britain as lyddite...

, 52, Japanese chemist who invented "Shimose powder", a powerful explosive successfully used in shells and torpedoes by the Japanese Imperial Navy.

September 8, 1911 (Friday)

- A day after the temperature at his Antarctic camp at FramheimFramheimFramheim was the name of explorer Roald Amundsen's base at the Bay of Whales on the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica during his quest for the South Pole...

rose to -7.6° F, Norwegian explorer Roald AmundsenRoald AmundsenRoald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen was a Norwegian explorer of polar regions. He led the first Antarctic expedition to reach the South Pole between 1910 and 1912 and he was the first person to reach both the North and South Poles. He is also known as the first to traverse the Northwest Passage....

, seven men and 86 dogs began the journey toward the South PoleSouth PoleThe South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole or Terrestrial South Pole, is one of the two points where the Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on the surface of the Earth and lies on the opposite side of the Earth from the North Pole...

. Four days later, the temperature dropped to -68° F, forcing Amundsen's return. - General John J. PershingJohn J. PershingJohn Joseph "Black Jack" Pershing, GCB , was a general officer in the United States Army who led the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I...

, serving in the PhilippinesPhilippinesThe Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

as U.S. Military Governor of the Moro ProvinceMoro ProvinceMoro Province is the name of the province of the Philippines consisting of the current provinces/regions of Zamboanga, Lanao, Cotabato, Davao, and Sulu...

issued Executive Order No. 24 to disarm the Moro residents. The rule made it unlawful for anyone in the province "to acquire, possess, or have the custody of any rifle, musket, carbine, shotgun, revolve, pistol or other deadly weapon from which a bullet, ball, shot, shell or other missile or missiles may be discharged by means of gunpowder or other explosive" and prohibited people from carrying "any bowie knife, dirk, dagger, kris, campilan, spear, or other deadly cutting or thrusting weapon, except tools used exclusively for working purposes having blades less than 15 inches in length" - The collapse of the El Dorado Theatre at NiceNiceNice is the fifth most populous city in France, after Paris, Marseille, Lyon and Toulouse, with a population of 348,721 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Nice extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of more than 955,000 on an area of...

killed 11 construction workers. - Lt. Col. Henry GalwayHenry GalwayLieutenant-Colonel Sir Henry Lionel Galway, KCMG, DSO was the Governor of South Australia from 18 April 1914 until 30 April 1920....

was appointed as the British colonial Governor of The Gambia.

September 9, 1911 (Saturday)

- The first test of air mail service in Britain was done by an airplane flight between Hendon AerodromeHendon AerodromeHendon Aerodrome was an aerodrome in Hendon, north London, England that, between 1908 and 1968, was an important centre for aviation.It was situated in Colindale, seven miles north west of Charing Cross. It nearly became "the Charing Cross of the UK's international air routes", but for the...

and WindsorWindsor, BerkshireWindsor is an affluent suburban town and unparished area in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead in Berkshire, England. It is widely known as the site of Windsor Castle, one of the official residences of the British Royal Family....

. - Governor Judson HarmonJudson HarmonJudson Harmon was a Democratic politician from Ohio. He served as United States Attorney General under President Grover Cleveland and later served as the 45th Governor of Ohio....

of Ohio opposed Taft at a campaign speech in Boston, and did not rule out a run for the Democratic nomination in 1912, with New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson as his running mate - Fourteen people were killed in a motorboat accident on Lake Trasimene in ItalyItalyItaly , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

. - Born: Sir John GortonJohn GortonSir John Grey Gorton, GCMG, AC, CH , Australian politician, was the 19th Prime Minister of Australia.-Early life:...

, 19th Prime Minister of AustraliaPrime Minister of AustraliaThe Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia is the highest minister of the Crown, leader of the Cabinet and Head of Her Majesty's Australian Government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful...

(1968-1971), in MelbourneMelbourneMelbourne is the capital and most populous city in the state of Victoria, and the second most populous city in Australia. The Melbourne City Centre is the hub of the greater metropolitan area and the Census statistical division—of which "Melbourne" is the common name. As of June 2009, the greater...

(d. 2002); and Paul GoodmanPaul Goodman (writer)Paul Goodman was an American sociologist, poet, writer, anarchist, and public intellectual. Goodman is now mainly remembered as the author of Growing Up Absurd and an activist on the pacifist Left in the 1960s and an inspiration to that era's student movement...

, American social critic, in New York City (d. 1972)

September 10, 1911 (Sunday)

- The Lakeview GusherLakeview GusherLakeview Gusher Number One was an immense out-of-control pressurized oil well in the Midway-Sunset Oil Field in Kern County, California, resulting in what is the largest single oil spill in history, lasting 18 months and releasing of crude oil. In what was one of the largest oil reserves in...

, which had erupted in California on March 14, 1910March 1910January - February - March - April - May - June - July - August - September - October - November -DecemberThe following events occurred in March, 1910:-March 1, 1910 :...

, ceased as sudenly as it started, as oil stopped flowing from it in the early morning hours. - `Abdu'l-Bahá`Abdu'l-Bahá‘Abdu’l-Bahá , born ‘Abbás Effendí, was the eldest son of Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Bahá'í Faith. In 1892, `Abdu'l-Bahá was appointed in his father's will to be his successor and head of the Bahá'í Faith. `Abdu'l-Bahá was born in Tehran to an aristocratic family of the realm...

, leader of the Baha'i FaithBahá'í FaithThe Bahá'í Faith is a monotheistic religion founded by Bahá'u'lláh in 19th-century Persia, emphasizing the spiritual unity of all humankind. There are an estimated five to six million Bahá'ís around the world in more than 200 countries and territories....

since 1892, gave his first lecture in the West, speaking at the City Temple in London at the request of the pastor, the Reverend John Campbell. - Died: Mrs. Samantha Breniholz, chief telegrapher for Union Army at Battle of Gettysburg; and Edward Butler, 73, St. Louis political boss and owner of a chain of blacksmithing shops

September 11, 1911 (Monday)

- California State University, FresnoCalifornia State University, FresnoCalifornia State University, Fresno, often referred to as Fresno State University and synonymously known in athletics as Fresno State , is one of the leading campuses of the California State University system, located at the northeast edge of Fresno, California, USA.The campus sits at the foot of...

, popularly known as Fresno State, began classes as the Fresno State Normal School. - The Pittsburgh PiratesPittsburgh PiratesThe Pittsburgh Pirates are a Major League Baseball club based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. They play in the Central Division of the National League, and are five-time World Series Champions...

, on the way from St. Louis to Cincinnati, stopped in West Baden, Indiana and played an exhibition game against a local African-American team, the West Baden Sprudels. The all-white Pirates, third place in the National League at the time with a record of 76-56, lost to the all-black Sprudels, 2-1. - The Bird of ParadiseRichard Walton TullyRichard Walton Tully was an American playwright. His best known works were the 1912 play The Bird of Paradise which caused a long running court case over alleged plagiarism...

, a musical credited with introducing Hawaiian music to the mainland United States, was first performed. - With 900,000 men on the battlefield, the German Army began the largest maneuvers in history, drilling at PrenzlauPrenzlauPrenzlau , a city in the Uckermark District of Brandenburg in Germany, had a population of about 21,000 in 2005.-International relations:Prenzlau is twinned with: Uster, Switzerland Barlinek, Poland Świdwin, Poland...

at PomeraniaPomeraniaPomerania is a historical region on the south shore of the Baltic Sea. Divided between Germany and Poland, it stretches roughly from the Recknitz River near Stralsund in the West, via the Oder River delta near Szczecin, to the mouth of the Vistula River near Gdańsk in the East...

. Exceeding any war games that had ever been done, the demonstration of German military might concluded on September 13 - The eruption of Mount EtnaMount EtnaMount Etna is an active stratovolcano on the east coast of Sicily, close to Messina and Catania. It is the tallest active volcano in Europe, currently standing high, though this varies with summit eruptions; the mountain is 21 m higher than it was in 1981.. It is the highest mountain in...

in Italy sent a lava stream 2000 feet wide and four feet deep, and leaving 20,000 homeless, between LinguaglossaLinguaglossaLinguaglossa is a town and comune in the Province of Catania in Italy, located on the northern side of Mount Etna. It was founded on a lava stream in 1566 which is reflected in the Sicilian name "tongue red"....

and RandazzoRandazzoRandazzo is a town and comune of Sicily, Italy, in the province of Catania. It is situated at the northern foot of Mount Etna, 70 km NW of Catania by rail. It is the nearest town to the summit of Etna, and is one of the points from which the ascent may be made.-History:In the 13th century the...

. - After a ten day voyage from England, the Hai Chi became the first Chinese warship to visit the United States, sailing into the port of New York City. The ship, with Rear Admiral Chin Pih Kwang on board, and anchored in the Hudson River.

- Born: Lala AmarnathLala AmarnathNanik Amarnath Bhardwaj was an Indian Test cricketer. He was the first cricketer to score a Test century for the Indian cricket team, which he achieved on debut...

, first captain of Indian National cricket team after independence (d. 2000)

September 12, 1911 (Tuesday)

- The Viceroy of Szechuan Province was ordered to suppress labor unrest there and "to destroy the rebels to the last man".

- Japan abandoned its naval station at Port Arthur naval base, Manchuria.

- Died: The Most Rev. William AlexanderWilliam Alexander (bishop)William Alexander was an Irish cleric in the Church of Ireland.-Life:He was born in Derry on the 13 April 1824, the third child of Rev Robert Alexander. He was educated at Tonbridge School and Brasenose College, Oxford....

, 87, Anglican Primate of All Ireland and Archbishop of ArmaghArchbishop of ArmaghThe Archbishop of Armagh is the title of the presiding ecclesiastical figure of each of the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of Ireland in the region around Armagh in Northern Ireland...

since 1896

September 13, 1911 (Wednesday)

- In Imperial ChinaLate Imperial ChinaLate Imperial China refers to the period between the end of Mongol rule in 1368 and the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912 and includes the Ming and Qing Dynasties...

, a new constitution with 19 articles was promulgated, providing for some democratic reforms, as well as the legal authority for emergency power to issue orders. The document was only in use for a month before the Qing dynastyQing DynastyThe Qing Dynasty was the last dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming Dynasty and followed by the Republic of China....

failed and the Republic of ChinaRepublic of ChinaThe Republic of China , commonly known as Taiwan , is a unitary sovereign state located in East Asia. Originally based in mainland China, the Republic of China currently governs the island of Taiwan , which forms over 99% of its current territory, as well as Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu and other minor...

was declared. - The "Third Attack Group", the first close air supportClose air supportIn military tactics, close air support is defined as air action by fixed or rotary winged aircraft against hostile targets that are close to friendly forces, and which requires detailed integration of each air mission with fire and movement of these forces.The determining factor for CAS is...

unit for the United States ArmyUnited States ArmyThe United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

, was established with four attack squadrons of flyers. - Born: Bill MonroeBill MonroeWilliam Smith Monroe was an American musician who created the style of music known as bluegrass, which takes its name from his band, the "Blue Grass Boys," named for Monroe's home state of Kentucky. Monroe's performing career spanned 60 years as a singer, instrumentalist, composer and bandleader...

, American musician nicknamed the Father of Bluegrass Music, in Rosine, KentuckyRosine, KentuckyRosine is an unincorporated town in Ohio County, Kentucky, United States. Bill Monroe, The Father of Bluegrass, is not only buried in the town but also memorialized with a bronze cast disk affixed to the barn where his music remains alive. The community was named for the pen name of Jenny Taylor...

(d. 1996)

September 14, 1911 (Thursday)

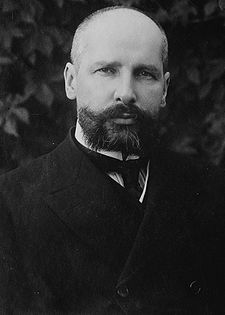

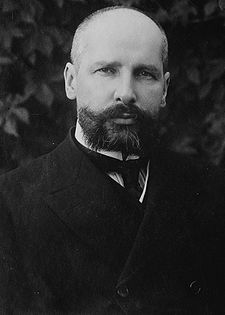

- Pyotr StolypinPyotr StolypinPyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin served as the leader of the 3rd DUMA—from 1906 to 1911. His tenure was marked by efforts to repress revolutionary groups, as well as for the institution of noteworthy agrarian reforms. Stolypin hoped, through his reforms, to stem peasant unrest by creating a class of...

, the Prime Minister of RussiaPrime Minister of RussiaThe Chairman of the Government of the Russian Federation The use of the term "Prime Minister" is strictly informal and is not allowed for by the Russian Constitution and other laws....

was assassinated. Stolypin was shot in the stomach by Dmitry BogrovDmitry BogrovDmitry Grigoriyevich Bogrov was the assassin of the Russian Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin.Born Mordekhai Gershkovich Bogrov...

while attending The Tale of Tsar SaltanThe Tale of Tsar SaltanThe Tale of Tsar Saltan, of His Son the Renowned and Mighty Bogatyr Prince Gvidon Saltanovich, and of the Beautiful Princess-Swan is an 1831 poem by Aleksandr Pushkin, written after the Russian fairy tale edited by Vladimir Dahl...

at the opera house in KievKievKiev or Kyiv is the capital and the largest city of Ukraine, located in the north central part of the country on the Dnieper River. The population as of the 2001 census was 2,611,300. However, higher numbers have been cited in the press....

, and died of his wounds four days later. - El Primer Congreso Mexicanista, with 400 Mexican American residents of Texas in attendance, was convened at LaredoLaredo, TexasLaredo is the county seat of Webb County, Texas, United States, located on the north bank of the Rio Grande in South Texas, across from Nuevo Laredo, Tamaulipas, Mexico. According to the 2010 census, the city population was 236,091 making it the 3rd largest on the United States-Mexican border,...

under the leadership of Nicasio IdarJovita IdarJovita Idar was an American journalist, political activist and civil rights worker, born in Laredo, Texas in 1885. Idar strove to advance the civil rights of Mexican-Americans....

to advocate civil rights for Hispanic citizens. The convention approved the formation of La Gran Liga de Beneficincia y Proteccion (The Grand League for Benefits and Protection).

September 15, 1911 (Friday)

- In the largest bank robbery to that time, three safecrackers broke into a branch of the Bank of Montreal in New Westminster, British ColumbiaNew Westminster, British ColumbiaNew Westminster is an historically important city in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia, Canada, and is a member municipality of the Greater Vancouver Regional District. It was founded as the capital of the Colony of British Columbia ....

, and stole $251,161 in Canadian currency and $20,560 worth of American double eagle gold coins, with a worth in U.S. dollars of $320,000. A janitor who had happened by at 4:00 in the morning was tied up by the robbers, and the bank's caretaker did not discover the theft until two hours later. The culprits left behind another $100,000 worth of small bills and silver and escaped without notice, despite the bank being located only 25 yards away from the city police station. "Australian Jack" McNamara and Charles Dean were both tried for the theft, and both acquitted, although McNamara was convicted of stealing an automobile believed to have been used as a getaway car. Bills from the robbery continued to be spotted a decade after the robbery. ; - U.S. President Taft finished the vacation at Beverly, MassachusettsBeverly, MassachusettsBeverly is a city in Essex County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 39,343 on , which differs by no more than several hundred from the 39,862 obtained in the 2000 census. A resort, residential and manufacturing community on the North Shore, Beverly includes Beverly Farms and Prides...

that had begun on August 11. Rather than returning to the White House, he began a 15,000 mile tour of 30 of the nation's 46 states. After spending three months away from Washington, D.C., Taft returned to the White House on November 12 - Born: Joseph PevneyJoseph PevneyJoseph Pevney was an American film and television director.-Biography:Pevney was born on September 15, 1911 in New York City, New York.He made his debut in vaudeville as a boy soprano in 1924...

, American television and film director in New York City (d. 2008); and Luther L. Terry, U.S. Surgeon General, 1961-1965 (d. 1985) - Died: Kimi-chan Huit, 9, subject of the Japanese children's song "The Girl in Red Shoes". Adopted by American missionary Charles Huit at the age of 3, she was abandoned to a church orphanage in Azabu-JubanAzabu-Juban Stationis a subway station in Minato, Tokyo, Japan.-Lines:This station is served by the Tokyo Metro Namboku Line and Toei Ōedo Line. The station number is N-04 for the Namboku Line and E-22 for the Ōedo Line.-Tokyo Metro:...

when the Huits returned to the U.S., because she had tuberculosis. Statues of Kimi were erected in several sites in Japan after her story was retold in 1973, including one at Azabu-Juban.

September 16, 1911 (Saturday)

- Ten auto race fans were killed, and 13 others seriously injured in Syracuse, New YorkSyracuse, New YorkSyracuse is a city in and the county seat of Onondaga County, New York, United States, the largest U.S. city with the name "Syracuse", and the fifth most populous city in the state. At the 2010 census, the city population was 145,170, and its metropolitan area had a population of 742,603...

, when a car driven by Lee Oldfield, brother of Barney OldfieldBarney OldfieldBerna Eli "Barney" Oldfield was an automobile racer and pioneer. He was born on a farm on the outskirts of Wauseon, Ohio. He was the first man to drive a car at 60 miles per hour on an oval...

blew a tire, went out of control at the New York State Fair and crashed through a fence. President Taft, a guest at the fair, had left only a few minutes earlier. - Born: Wilfred BurchettWilfred BurchettWilfred Graham Burchett was an Australian journalist known for his reporting of conflicts in Asia and his Communist sympathies...

, leftist Australian journalist, at Clifton Hill, VictoriaClifton Hill, VictoriaClifton Hill is a suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 4 km north-east from Melbourne's central business district. The border between Clifton Hill and Fitzroy North is Queens Parade and Smith Street. Merri Creek defines the eastern border of Clifton Hill. Its Local Government Area is...

(d. 1983) - Died: Edward WhymperEdward WhymperEdward Whymper , was an English illustrator, climber and explorer best known for the first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865. On the descent four members of the party were killed.-Early life:...

, 71, the first man to climb the MatterhornMatterhornThe Matterhorn , Monte Cervino or Mont Cervin , is a mountain in the Pennine Alps on the border between Switzerland and Italy. Its summit is 4,478 metres high, making it one of the highest peaks in the Alps. The four steep faces, rising above the surrounding glaciers, face the four compass points...

(on July 14, 1865); and Édouard de Nié PortÉdouard de Nié PortÉdouard de Nié Port was the co-founder with his brother Charles of the eponymous Nieuport aircraft manufacturing company, Société Anonyme Des Établissements Nieuport, formed in 1909 at Issy-les-Moulineaux...

, 36, French aircraft pilot and designer; in a plane crash

September 17, 1911 (Sunday)

- Calbraith Perry RodgersCalbraith Perry RodgersCalbraith Perry Rodgers was an American pioneer aviator. He made the first transcontinental airplane flight across the U.S. from September 17, 1911 to November 5, 1911, with dozens of stops, both intentional and accidental...

took off from the airstrip at Sheepshead Bay near New York City with the goal of winning the $50,000 Hearst Transcontinental Prize for the first person to fly across the United States in an airplane within 30 days and before October 10, 1911. Sponsored by the Armour Company and flying the Vin Fiz, Rodgers made 69 landings, including 19 crashes. When the deadline for the prize expired on October 10, he had only reached Marshall, MissouriMarshall, MissouriMarshall is a city in Saline County, Missouri, United States. The population was 13,065 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Saline County,. The Marshall Micropolitan Statistical Area consists of Saline County. It is also home to Missouri Valley College...

, but he continued until landing in PasadenaPasadena-Places:Places in Australia:*Pasadena, South Australia, a suburb of AdelaidePlaces in Canada:*Pasadena, NewfoundlandPlaces in the United States:*Pasadena, California*South Pasadena, California*South Pasadena, Florida*Pasadena, Maryland...

on November 5, 1911, having covered 4,231 miles in 49 days.

September 18, 1911 (Monday)

- Osman Ali Khan was formally entrhoned as the new Nizam of Hyderabad in an elaborate durbar attended by the nobility across his Indian princely state.

- The value of reconnaissance by airplane was first demonstrated to the French ArmyFrench ArmyThe French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

, conducted for the Grand Quartier General of the French Army, as Captain Eteve and Captain Pichot-Duclas flew from VerdunVerdunVerdun is a city in the Meuse department in Lorraine in north-eastern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department.Verdun is the biggest city in Meuse, although the capital of the department is the slightly smaller city of Bar-le-Duc.- History :...

to EtrayeÉtrayeÉtraye is a commune in the Meuse department in Lorraine in north-eastern France.- See also :* Communes of the Meuse department...

and RomagneRomagneRomagne is the name or part of the name of several places in France:* Romagne, Gironde, a commune in the Gironde department* Romagné, a commune in the Ille-et-Vilaine department* Romagne, Vienne, a commune in the Vienne department...

and provided in-depth information of their observations. - Died: Pyotr Stolypin, 49, Prime Minister of Russia

September 19, 1911 (Tuesday)

- Labor unions across Spain called for a walkout, martial law proclaimed

- Born: William GoldingWilliam GoldingSir William Gerald Golding was a British novelist, poet, playwright and Nobel Prize for Literature laureate, best known for his novel Lord of the Flies...

, British novelist most famous for Lord of the FliesLord of the FliesLord of the Flies is a novel by Nobel Prize-winning author William Golding about a group of British boys stuck on a deserted island who try to govern themselves, with disastrous results...

, in NewquayNewquayNewquay is a town, civil parish, seaside resort and fishing port in Cornwall, England. It is situated on the North Atlantic coast of Cornwall approximately west of Bodmin and north of Truro....

, Cornwall, England; winner of 1983 Nobel Prize in LiteratureNobel Prize in LiteratureSince 1901, the Nobel Prize in Literature has been awarded annually to an author from any country who has, in the words from the will of Alfred Nobel, produced "in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction"...

(d. 1993)

September 20, 1911 (Wednesday)

- The massive White Star ocean liner RMS Olympic collided with the British cruiser HMS HawkeHMS Hawke (1891)HMS Hawke, launched in 1891, was the sixth British warship to be named Hawke. She was an Edgar-class protected cruiser.-Service:...

at the SolentSolentThe Solent is a strait separating the Isle of Wight from the mainland of England.The Solent is a major shipping route for passengers, freight and military vessels. It is an important recreational area for water sports, particularly yachting, hosting the Cowes Week sailing event annually...

, the narrow strait near Southampton, and was badly damaged. . The captain of the Olympic was Edward J. Smith, who would later be assigned to the White Star liner RMS Titanic, and who died after that ship sank on its maiden voyage on April 15, 1912. The White Star LineWhite Star LineThe Oceanic Steam Navigation Company or White Star Line of Boston Packets, more commonly known as the White Star Line, was a prominent British shipping company, today most famous for its ill-fated vessel, the RMS Titanic, and the World War I loss of Titanics sister ship Britannic...

was successfully sued for damages to the Hawke after investigators determined that the Olympic had failed to yield the right of way to the smaller ship. In repairing the Olympic, the White Star Line delayed the completion and scheduled March 20, 1912 launch of the Titanic by 20 days. One historian speculated later that, "If the Hawke and the Olympic had never met, neither would the iceberg and the Titanic." - Born: Shriram Sharma, Indian religious leader (d. 1990) Frank De VolFrank De VolFrank Denny De Vol, also known simply as De Vol was an American arranger, composer and actor.-Early life and career:...

, American composer for film and television, in AgraAgraAgra a.k.a. Akbarabad is a city on the banks of the river Yamuna in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, India, west of state capital, Lucknow and south from national capital New Delhi. With a population of 1,686,976 , it is one of the most populous cities in Uttar Pradesh and the 19th most...

(d. 1990); and Moundsville, West VirginiaMoundsville, West VirginiaMoundsville is a city in Marshall County, West Virginia, along the Ohio River. It is part of the Wheeling Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 9,998 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Marshall County. The city was named for the Grave Creek Mound. Moundsville was settled in...

(d. 1999); - Died: Anna Parnell, 59, Irish political journalist

September 21, 1911 (Thursday)

- Canadian federal election, 1911Canadian federal election, 1911The Canadian federal election of 1911 was held on September 21 to elect members of the Canadian House of Commons of the 12th Parliament of Canada.-Summary:...

: Prime Minister Wilfrid LaurierWilfrid LaurierSir Wilfrid Laurier, GCMG, PC, KC, baptized Henri-Charles-Wilfrid Laurier was the seventh Prime Minister of Canada from 11 July 1896 to 6 October 1911....

was swept out of office and his Liberal Party lost its 133-85 majority in the 221 seat House of Commons. The Conservative Party, led by Robert BordenRobert BordenSir Robert Laird Borden, PC, GCMG, KC was a Canadian lawyer and politician. He served as the eighth Prime Minister of Canada from October 10, 1911 to July 10, 1920, and was the third Nova Scotian to hold this office...

, picked up 47 seats for a 132-85 advantage, as voters made it clear that they did not support the proposal for full trade reciprocity with the United States. - Chinese troops relieved the besieged city of ChengduChengduChengdu , formerly transliterated Chengtu, is the capital of Sichuan province in Southwest China. It holds sub-provincial administrative status...

and found that no foreigners had been harmed. - Died: Ahmed Arabi Pasha, 70, exiled Egyptian rebel leader of the 1881 rebellion against British rule

September 22, 1911 (Friday)

- Cy YoungCy YoungDenton True "Cy" Young was an American Major League Baseball pitcher. During his 22-year baseball career , he pitched for five different teams. Young was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1937...

pitched his 511th and final win, leading the Boston RustlersAtlanta BravesThe Atlanta Braves are a professional baseball club based in Atlanta, Georgia. The Braves are a member of the Eastern Division of Major League Baseball's National League. The Braves have played in Turner Field since 1997....

(who would be renamed the Boston Braves in 1912) to a 1-0 while visiting the Pittsburgh PiratesPittsburgh PiratesThe Pittsburgh Pirates are a Major League Baseball club based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. They play in the Central Division of the National League, and are five-time World Series Champions...

. The 511 wins is a record that remains unapproached a century later. . Walter JohnsonWalter JohnsonWalter Perry Johnson , nicknamed "Barney" and "The Big Train", was a Major League Baseball right-handed pitcher. He played his entire 21-year baseball career for the Washington Senators...

is second with 417 career wins, and the career record for a pitcher active in 2011 was around 200 for Tim WakefieldTim WakefieldTimothy Stephen Wakefield is an American professional baseball pitcher. Wakefield began pitching with the Red Sox in 1995, making him the longest-serving player currently on the team. Wakefield is also the oldest current active player in the majors, and one of two active knuckleballers, the other...

. Young pitched two more games in 1911, finishing with 313 losses, also a record.

September 23, 1911 (Saturday)

- In the first major demonstration by Protestant Irishmen against "Home Rule" and the separation of all of Ireland from the United Kingdom, Edward Carson led the march of 50,000 Unionists in Northern Ireland from BelfastBelfastBelfast is the capital of and largest city in Northern Ireland. By population, it is the 14th biggest city in the United Kingdom and second biggest on the island of Ireland . It is the seat of the devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly...

to Craigavon, the home of James Craig, 1st Viscount CraigavonJames Craig, 1st Viscount CraigavonJames Craig, 1st Viscount Craigavon, PC, PC , was a prominent Irish unionist politician, leader of the Ulster Unionist Party and the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland...

, and addressed the crowd, declaring, "We must be prepared.. the morning Home Rule passes, ourselves to become responsible forthe government of the Protestant Province of Ulster." - Vladimir KokovtsovVladimir KokovtsovCount Vladimir Nikolayevich Kokovtsov was a Russian prime minister during the reign of Nicholas II of Russia.- Biography :...

, Finance Minister, became the new Prime Minister of Russia - The Argentine battleship ARA MorenoARA MorenoARA Moreno was a dreadnought battleship designed by the American Fore River Shipbuilding Company for the Argentine Navy...

, joining the Rivadavia as larger than any other warship in the world, was launched from a shipyard in Camden, New JerseyCamden, New JerseyThe city of Camden is the county seat of Camden County, New Jersey. It is located across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. As of the 2010 United States Census, the city had a total population of 77,344...

. - Jack DonaldsonJack Donaldson (athlete)John Donaldson, Jnr, , better known as Jack, was a professional sprinter in the early part of the 1900s. He held various world sprinting records ranging from 100 yards to 400 yards, some of which stood for many years.-Early life:...

of Australia, nicknamed "The Blue Streak" ran 130 yards in 12 seconds in a foot race against American challenger C.E. "Bullet" Holway, setting a new world record. - Died: Charles Battell LoomisCharles Battell LoomisCharles Battell Loomis was an American author, born in Brooklyn, New York and educated at the Polytechnic Institute there. He was in business from 1879 to 1891, but he gave it up to devote himself to the writing of magazine sketches and books much appreciated for their humor...

, 50, American humorist

September 24, 1911 (Sunday)

- A train struck a group of people on a hayride at Neenah, WisconsinNeenah, WisconsinNeenah is a city on Lake Winnebago in Winnebago County, Wisconsin, United States. Its population was 24,507 at the 2000 census. The city is bordered by, but is politically independent of, the Town of Neenah. Neenah is the southwestern-most of the Fox Cities of Northeast Wisconsin...

, killing 13 and seriously injuring 8. The group had been returning to MenashaMenasha, WisconsinMenasha is a city in Calumet and Winnebago Counties in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. The population was 16,331 at the 2000 census. The city is located mostly in the Town of Menasha in Winnebago County; only a small portion is in the Town of Harrison in Calumet County. Doty Island is located...

from a late night wedding anniversary celebration in a fog, when it was struck by the No. 121 train of the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad. The crossing, whose view was blocked by a billboard, had been the scene of several other fatal accidents in the previous 8 years. - As war between Italy and the Ottoman Empire appeared imminent, Conrad von Hötzendorf, Chief of the General Staff, sent a proposal to the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Count Alois Lexa von Aehrenthal, proposing that Austria attack Italy or conquer the Balkan territories.

- Born: Konstantin ChernenkoKonstantin ChernenkoKonstantin Ustinovich Chernenko was a Soviet politician and the fifth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He led the Soviet Union from 13 February 1984 until his death thirteen months later, on 10 March 1985...

, President of the Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

and General Secretary of the Communist Party of the USSR from 1984 until his death in 1985; in Bolshaya TesNovosyolovsky DistrictNovosyolovsky District is an administrative and municipal district , one of the forty-three in Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia. It is located in the southwestern portion of the krai and borders with Balakhtinsky District in the north and east, Krasnoturansky District in the southeast, the Republic of...

, Russian EmpireRussian EmpireThe Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

; and Ed KretzEd KretzEd Kretz, Sr. , aka Ed "Iron Man" Kretz, was a motorcycle racer in the 1930s and 1940s.Kretz was known for riding rough. He strove to finish, and win, every race. He rode #38, usually on an Indian motorcycle.Kretz was best known for winning the first Daytona 200 race in 1937, riding an Indian...

, American motorcycle racer, in San Diego (d. 1996)

September 25, 1911 (Monday)

- The French battleship LibertéFrench battleship Liberté (1905)The Liberté was a pre-dreadnought battleship of the French Navy, and the lead ship of her class. Commanded by capitaine de vaisseau Louis Jaurès, She sailed to the United States after her commissioning...

exploded at anchor in ToulonToulonToulon is a town in southern France and a large military harbor on the Mediterranean coast, with a major French naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur region, Toulon is the capital of the Var department in the former province of Provence....

, France killing 235 on the ship and another 65 on other ships, in the worst disaster to have hit the French Navy around 300 on both ship and the neighbouring area. At 4:00 in the morning, a fire broke out on the ship, and at 5:35 it reached magazines of gun powder. The largest blast happened at 5:53. - Born: Eric WilliamsEric WilliamsEric Eustace Williams served as the first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago. He served from 1956 until his death in 1981. He was also a noted Caribbean historian, and is widely regarded as "The Father of The Nation."...

, first Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago (d. 1981); and Lilian NgoyiLilian NgoyiLillian Masediba Ngoyi "Ma Ngoyi", , was a South African anti-apartheid activist. She was the first woman elected to the executive committee of the African National Congress, and helped launch the Federation of South African Women.Ngoyi joined the ANC Women's League in 1952; she was at that stage a...

, South African anti-apartheid activist, in PretoriaPretoriaPretoria is a city located in the northern part of Gauteng Province, South Africa. It is one of the country's three capital cities, serving as the executive and de facto national capital; the others are Cape Town, the legislative capital, and Bloemfontein, the judicial capital.Pretoria is...

(d. 1980) - Died: Dmitri Bogrov, who had fatally wounded Premier Stolypin on September 14, was hanged

September 26, 1911 (Tuesday)

- Italo-Turkish WarItalo-Turkish WarThe Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War was fought between the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Italy from September 29, 1911 to October 18, 1912.As a result of this conflict, Italy was awarded the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania, Fezzan, and...

: The government of ItalyItalyItaly , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

prepared an ultimatum to TurkeyTurkeyTurkey , known officially as the Republic of Turkey , is a Eurasian country located in Western Asia and in East Thrace in Southeastern Europe...

, demanding cession of the Ottoman Empire's North African territory in modern day LibyaLibyaLibya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

, on grounds that Muslim fanatics in TripoliTripoliTripoli is the capital and largest city in Libya. It is also known as Western Tripoli , to distinguish it from Tripoli, Lebanon. It is affectionately called The Mermaid of the Mediterranean , describing its turquoise waters and its whitewashed buildings. Tripoli is a Greek name that means "Three...

were endangering Italian lives. Because GermanyGermanyGermany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

had been attempting to mediate the crisis between the two kingdoms, delivery of the ultimatum was held off for two days.

September 27, 1911 (Wednesday)

- Swedish general election, 1911Swedish general election, 1911A general election was held in Sweden in 1911 to allocate the seats of what was then the lower of the two houses of the Swedish Riksdag. This election was the first election in Sweden with universal male suffrage.Source: Statistics Sweden...

: In the first parliamentary elections in Sweden since the introduction of universal male suffrage, the Liberal PartyLiberal Coalition PartyThe Liberal Coalition Party was a political party in Sweden represented in the Swedish parliament from 1900 to 1924. The party was in government from 1905 to 1906 and from 1911 to 1914 under the leadership of Karl Staaff, and from 1917 to 1920 under the leadership of Nils Edén.In 1924 the party...

, led by Karl StaafKarl StaafKarl Gustaf Staaf was a Swedish athlete and tug of war competitor who competed at the 1900 Summer Olympics.He finished seventh in the pole vault competition and fifth in the hammer throw event....

, won 102 of the 230 seats in the RiksdagParliament of SwedenThe Riksdag is the national legislative assembly of Sweden. The riksdag is a unicameral assembly with 349 members , who are elected on a proportional basis to serve fixed terms of four years...

, bringing an end to the Conservative government of Prime Minister Arvid LindmanArvid LindmanSalomon Arvid Achates Lindman was a Swedish Rear Admiral, Industrialist and conservative politician...

. - Born: John HarveyJohn Harvey (actor)John Harvey was an English actor. He appeared in 52 films, two television films and made 70 television guest appearances between 1948 and 1979....

, British character actor, in London (d. 1982) - Died: A. K. Loring, 74, founder of the first circulating library (in Boston)

September 28, 1911 (Thursday)

- Italo-Turkish WarItalo-Turkish WarThe Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War was fought between the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Italy from September 29, 1911 to October 18, 1912.As a result of this conflict, Italy was awarded the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania, Fezzan, and...

: Italy's ultimatum served upon Turkish Grand Vizier Ibrahim Hakki PashaIbrahim Hakki PashaIbrahim Hakki Pasha was one of the Grand Viziers of the Ottoman Empire.-References:...

at noon by Giacomo De MartinoGiacomo De MartinoBaron Giacomo de Martino was the Envoy of Italy to the United States during the regime of Benito Mussolini. On January 23, 1927 he traveled to Chicago, and spent several days touring the city addressing the Italian community and explaining Fascism....

, the Italian Charge d'Affaires at ConstantinopleConstantinopleConstantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

after negotiations by Baron Marschall von Bieberstein, the German Ambassador, had failed, giving Turkey 24 hours to give up Libya or to go to war. - Five days after the appeal in BelfastBelfastBelfast is the capital of and largest city in Northern Ireland. By population, it is the 14th biggest city in the United Kingdom and second biggest on the island of Ireland . It is the seat of the devolved government and legislative Northern Ireland Assembly...

by Edward Carson, "Ulster Day" was set aside for residents of the Irish province to sign a covenant to resist rule from Dublin in the event that Ireland was granted Home Rule. The pledge was signed by 237,368 men and 234,046 women.

September 29, 1911 (Friday)

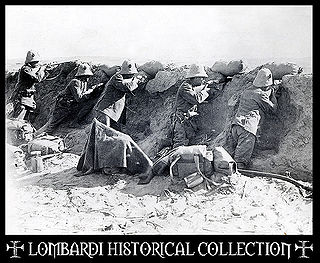

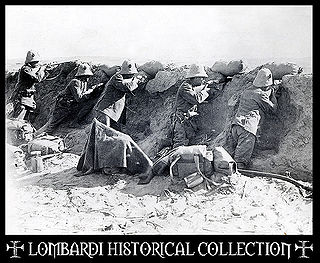

- Italo-Turkish WarItalo-Turkish WarThe Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War was fought between the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Italy from September 29, 1911 to October 18, 1912.As a result of this conflict, Italy was awarded the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania, Fezzan, and...

: After its ultimatum to Turkey expired at noon, the Italian destroyer Garibaldino sailed into the harbor at TripoliTripoliTripoli is the capital and largest city in Libya. It is also known as Western Tripoli , to distinguish it from Tripoli, Lebanon. It is affectionately called The Mermaid of the Mediterranean , describing its turquoise waters and its whitewashed buildings. Tripoli is a Greek name that means "Three...

, and an officer from the ship approached the commander of the Turkish Army to formally demand the city's surrender, which was refused. At 2:30 pm, ItalyItalyItaly , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

declared war on Ottoman EmpireOttoman EmpireThe Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

at 2:30 pm after Turkey declined to surrender Tripoli. . Having failed to prepare Turkey for war, Grand Vizier Hakkı Pasha resigned and was succeeded by Mehmed Said Pasha. The landing of Italian troops took place simultaneously at TripoliTripoliTripoli is the capital and largest city in Libya. It is also known as Western Tripoli , to distinguish it from Tripoli, Lebanon. It is affectionately called The Mermaid of the Mediterranean , describing its turquoise waters and its whitewashed buildings. Tripoli is a Greek name that means "Three...

, BenghaziBenghaziBenghazi is the second largest city in Libya, the main city of the Cyrenaica region , and the former provisional capital of the National Transitional Council. The wider metropolitan area is also a district of Libya...

, Derna and TobrukTobrukTobruk or Tubruq is a city, seaport, and peninsula on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near the border with Egypt. It is the capital of the Butnan District and has a population of 120,000 ....

, "accompanied by the first air raids in history, with the pilots of early biplanes flying low over their targets and lobbing small bombs out by hand" Within a year, Libya would become a protectorateProtectorateIn history, the term protectorate has two different meanings. In its earliest inception, which has been adopted by modern international law, it is an autonomous territory that is protected diplomatically or militarily against third parties by a stronger state or entity...

of Italy. - Died: Henry Northcote, 1st Baron NorthcoteHenry Northcote, 1st Baron NorthcoteHenry Stafford Northcote, 1st Baron Northcote GCMG, GCIE, CB, PC , known as Sir Henry Northcote, Bt, between 1887 and 1900, was a Conservative politician and colonial administrator...

, 65, who served from 1904 to 1908 as the 3rd Governor-General of AustraliaGovernor-General of AustraliaThe Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia is the representative in Australia at federal/national level of the Australian monarch . He or she exercises the supreme executive power of the Commonwealth...

September 30, 1911 (Saturday)

- Austin DamAustin DamAustin Dam was a dam in the Freeman Run Valley, Potter County, Pennsylvania, which serviced the Bayless Pulp & Paper Mill. A failure of the dam in 1911 caused significant destruction in the valley below.-History:...

Disaster: A concrete dam, maintained by the Bayless Pulp and Paper Mill, burst at 2:30 in the afternoon, sending 4,500,000 gallons of water through the town of Austin, PennsylvaniaAustin, PennsylvaniaAustin is a borough in Potter County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 623 at the 2000 census.-Geography:Austin is located at ....

and the smaller localities of Costello and Wharton. Officially, seventy-eight people were killed, although the initial estimate of death was almost 1,000. ` - The U.S. Army became the first army in the world to make vaccinations against typhoid mandatory. Within 9 months, the whole army had been immunized against typhoid.

- Born: Ruth GruberRuth GruberRuth Gruber is an American journalist, photographer, writer, humanitarian and a former United States government official.-Early life:...

, American humanitarian, in New York City - Died: Wilhelm DiltheyWilhelm DiltheyWilhelm Dilthey was a German historian, psychologist, sociologist and hermeneutic philosopher, who held Hegel's Chair in Philosophy at the University of Berlin. As a polymathic philosopher, working in a modern research university, Dilthey's research interests revolved around questions of...

, 77, German philosopher