1930s

Encyclopedia

Dorothea Lange

Dorothea Lange was an influential American documentary photographer and photojournalist, best known for her Depression-era work for the Farm Security Administration...

's photo of the homeless Florence Thompson

Florence Owens Thompson

Florence Owens Thompson , born Florence Leona Christie, was the subject of Dorothea Lange's photo Migrant Mother , an iconic image of the Great Depression. The Library of Congress entitled the Migrant Mother image, "Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two...

show the effects of the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

; Due to the economic collapse, the farms become dry and the Dust Bowl

Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl, or the Dirty Thirties, was a period of severe dust storms causing major ecological and agricultural damage to American and Canadian prairie lands from 1930 to 1936...

spreads through America; The Battle of Wuhan

Battle of Wuhan

The Battle of Wuhan, popularly known to the Chinese as the Defence of Wuhan, and to the Japanese as the Capture of Wuhan, was a large-scale battle of the Second Sino-Japanese War...

during the Second Sino-Japanese War

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was a military conflict fought primarily between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. From 1937 to 1941, China fought Japan with some economic help from Germany , the Soviet Union and the United States...

; Aviator

Aviator

An aviator is a person who flies an aircraft. The first recorded use of the term was in 1887, as a variation of 'aviation', from the Latin avis , coined in 1863 by G. de la Landelle in Aviation Ou Navigation Aérienne...

Amelia Earhart

Amelia Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart was a noted American aviation pioneer and author. Earhart was the first woman to receive the U.S. Distinguished Flying Cross, awarded for becoming the first aviatrix to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean...

becomes a national icon; German

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

dictator

Dictator

A dictator is a ruler who assumes sole and absolute power but without hereditary ascension such as an absolute monarch. When other states call the head of state of a particular state a dictator, that state is called a dictatorship...

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

and the Nazi Party attempted to establish a New Order

New Order (political system)

The New Order or the New Order of Europe was the political order which the Nazis wanted to impose on Europe, and eventually the rest of the world, during their reign over Germany from 1933 to 1945...

of absolute Nazi German hegemony

Hegemony

Hegemony is an indirect form of imperial dominance in which the hegemon rules sub-ordinate states by the implied means of power rather than direct military force. In Ancient Greece , hegemony denoted the politico–military dominance of a city-state over other city-states...

in Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

, which culminated in 1939 when Germany invaded Poland

Invasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

, leading to the outbreak of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

; The Hindenburg

LZ 129 Hindenburg

LZ 129 Hindenburg was a large German commercial passenger-carrying rigid airship, the lead ship of the Hindenburg class, the longest class of flying machine and the largest airship by envelope volume...

explodes

Hindenburg disaster

The Hindenburg disaster took place on Thursday, May 6, 1937, as the German passenger airship LZ 129 Hindenburg caught fire and was destroyed during its attempt to dock with its mooring mast at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station, which is located adjacent to the borough of Lakehurst, New Jersey...

over a small New Jerseian airfield

Lakehurst, New Jersey

Lakehurst is a Borough in Ocean County, New Jersey, United States. As of the United States 2010 Census, the borough population was 2,654.Lakehurst was incorporated as a borough by an Act of the New Jersey Legislature on April 7, 1921, from portions of Manchester Township, based on the results of a...

, effectively ending commercial airship travel; Mohandas Gandhi walks to the Indian Ocean

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third largest of the world's oceanic divisions, covering approximately 20% of the water on the Earth's surface. It is bounded on the north by the Indian Subcontinent and Arabian Peninsula ; on the west by eastern Africa; on the east by Indochina, the Sunda Islands, and...

in the Salt March

Salt Satyagraha

The Salt March, also known as the Salt Satyagrahah began with the Dandi March on March 12, 1930, and was an important part of the Indian independence movement. It was a campaign of tax resistance and nonviolent protest against the British salt monopoly in colonial India, and triggered the wider...

of 1930.|420px|thumb

rect 1 1 174 226 Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

rect 177 1 375 121 Dust Bowl

Dust Bowl

The Dust Bowl, or the Dirty Thirties, was a period of severe dust storms causing major ecological and agricultural damage to American and Canadian prairie lands from 1930 to 1936...

rect 177 124 375 226 Second Sino-Japanese War

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was a military conflict fought primarily between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. From 1937 to 1941, China fought Japan with some economic help from Germany , the Soviet Union and the United States...

rect 378 1 497 226 Amelia Earhart

Amelia Earhart

Amelia Mary Earhart was a noted American aviation pioneer and author. Earhart was the first woman to receive the U.S. Distinguished Flying Cross, awarded for becoming the first aviatrix to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean...

rect 1 229 221 353 Salt March

Salt Satyagraha

The Salt March, also known as the Salt Satyagrahah began with the Dandi March on March 12, 1930, and was an important part of the Indian independence movement. It was a campaign of tax resistance and nonviolent protest against the British salt monopoly in colonial India, and triggered the wider...

rect 1 357 221 488 Hindenburg disaster

Hindenburg disaster

The Hindenburg disaster took place on Thursday, May 6, 1937, as the German passenger airship LZ 129 Hindenburg caught fire and was destroyed during its attempt to dock with its mooring mast at the Lakehurst Naval Air Station, which is located adjacent to the borough of Lakehurst, New Jersey...

rect 225 230 497 488 Nazi Party

The 1930s, or the Thirties, was the decade that started on January 1, 1930 and ended on December 31, 1939. It was the fourth decade of the 20th century.

After the Wall Street Crash of 1929

Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 , also known as the Great Crash, and the Stock Market Crash of 1929, was the most devastating stock market crash in the history of the United States, taking into consideration the full extent and duration of its fallout...

, the largest stock market crash

Stock market crash

A stock market crash is a sudden dramatic decline of stock prices across a significant cross-section of a stock market, resulting in a significant loss of paper wealth. Crashes are driven by panic as much as by underlying economic factors...

in American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

history, most of the decade was consumed by an economic downfall called The Great Depression that had a traumatic effect worldwide. In response, authoritarian regimes emerged in several countries in Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

, in particular the Third Reich

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

in Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

. Weaker states such as Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

, China

Republic of China

The Republic of China , commonly known as Taiwan , is a unitary sovereign state located in East Asia. Originally based in mainland China, the Republic of China currently governs the island of Taiwan , which forms over 99% of its current territory, as well as Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu and other minor...

, and Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

were invaded by expansionist world powers, ultimately leading to World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

by the decade's end. The decade also saw a proliferation in new technologies, including intercontinental aviation

Aviation

Aviation is the design, development, production, operation, and use of aircraft, especially heavier-than-air aircraft. Aviation is derived from avis, the Latin word for bird.-History:...

, radio

Radio

Radio is the transmission of signals through free space by modulation of electromagnetic waves with frequencies below those of visible light. Electromagnetic radiation travels by means of oscillating electromagnetic fields that pass through the air and the vacuum of space...

, and film

Film

A film, also called a movie or motion picture, is a series of still or moving images. It is produced by recording photographic images with cameras, or by creating images using animation techniques or visual effects...

.

Wars

- Colombia–Peru War (1 September 1932 – 24 May 1933) – fought between the Republic of Colombia and the Republic of Peru.

- Chaco WarChaco WarThe Chaco War was fought between Bolivia and Paraguay over control of the northern part of the Gran Chaco region of South America, which was incorrectly thought to be rich in oil. It is also referred to as La Guerra de la Sed in literary circles for being fought in the semi-arid Chaco...

(15 June 1932 – 10 June 1935) – the war was fought between BoliviaBoliviaBolivia officially known as Plurinational State of Bolivia , is a landlocked country in central South America. It is the poorest country in South America...

and ParaguayParaguayParaguay , officially the Republic of Paraguay , is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to the east and northeast, and Bolivia to the northwest. Paraguay lies on both banks of the Paraguay River, which runs through the center of the...

over the disputed territory of Gran ChacoGran ChacoThe Gran Chaco is a sparsely populated, hot and semi-arid lowland region of the Río de la Plata basin, divided among eastern Bolivia, Paraguay, northern Argentina and a portion of the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul, where it is connected with the Pantanal region...

resulting in an overall Paraguayan victory in 1935. An agreement dividing the territory was made in 1938, officially ending outstanding differences and bringing an official "peace" to the conflict. - Second Sino-Japanese WarSecond Sino-Japanese WarThe Second Sino-Japanese War was a military conflict fought primarily between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. From 1937 to 1941, China fought Japan with some economic help from Germany , the Soviet Union and the United States...

(7 July 1937 – 9 September 1945) – fought between the Republic of ChinaRepublic of ChinaThe Republic of China , commonly known as Taiwan , is a unitary sovereign state located in East Asia. Originally based in mainland China, the Republic of China currently governs the island of Taiwan , which forms over 99% of its current territory, as well as Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu and other minor...

and the Empire of JapanEmpire of JapanThe Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

. The Second Sino-Japanese War was the largest AsiaAsiaAsia is the world's largest and most populous continent, located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres. It covers 8.7% of the Earth's total surface area and with approximately 3.879 billion people, it hosts 60% of the world's current human population...

n warWarWar is a state of organized, armed, and often prolonged conflict carried on between states, nations, or other parties typified by extreme aggression, social disruption, and usually high mortality. War should be understood as an actual, intentional and widespread armed conflict between political...

in the twentieth century. It also made up more than 50% of the casualties in the Pacific War. - World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

outbreaks on September 1, 1939.

Internal conflicts

- Spanish Civil WarSpanish Civil WarThe Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

(17 July 1936 – 1 April 1939) – GermanyGermanyGermany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

and ItalyItalyItaly , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

back anti-communist FalangeFalangeThe Spanish Phalanx of the Assemblies of the National Syndicalist Offensive , known simply as the Falange, is the name assigned to several political movements and parties dating from the 1930s, most particularly the original fascist movement in Spain. The word means phalanx formation in Spanish....

forces of Francisco FrancoFrancisco FrancoFrancisco Franco y Bahamonde was a Spanish general, dictator and head of state of Spain from October 1936 , and de facto regent of the nominally restored Kingdom of Spain from 1947 until his death in November, 1975...

. The Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

and international communist parties (see Abraham Lincoln BrigadeAbraham Lincoln BrigadeThe Abraham Lincoln Brigade refers to volunteers from the United States who served in the Spanish Civil War in the International Brigades. They fought for Spanish Republican forces against Franco and the Spanish Nationalists....

) back the left-wing republican faction in the war. The war ends in April 1939 with Franco's nationalist forces defeating the republican forces. Franco becomes Head of State of Spain, President of Government and de facto dictator. The Republic gives way to the Spanish StateSpanish StateFrancoist Spain refers to a period of Spanish history between 1936 and 1975 when Spain was under the authoritarian dictatorship of Francisco Franco....

, an authoritarian dictatorshipDictatorshipA dictatorship is defined as an autocratic form of government in which the government is ruled by an individual, the dictator. It has three possible meanings:...

.

- Castellammarese WarCastellammarese WarThe Castellammarese War was a bloody power struggle for control of the Italian-American Mafia between partisans of Joe "The Boss" Masseria and those of Salvatore Maranzano. It was so called because Maranzano was based in Castellammare del Golfo, Sicily...

(1929 – 10 September 1931).

Major political changes

The rise of NazismNazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

- Adolf HitlerAdolf HitlerAdolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

and the National Socialist German Worker's Party (Nazi Party) rise to power in Germany in 1933, forming a fascistFascismFascism is a radical authoritarian nationalist political ideology. Fascists seek to rejuvenate their nation based on commitment to the national community as an organic entity, in which individuals are bound together in national identity by suprapersonal connections of ancestry, culture, and blood...

regime committed to repudiating the Treaty of VersaillesTreaty of VersaillesThe Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

, persecuting and removing JewsJewsThe Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

and other minorities from German society, expanding Germany's territory, and opposing the spread of communismCommunismCommunism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

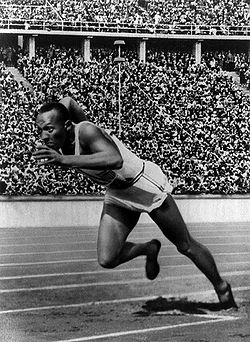

. - Hitler pulls Germany out of the League of Nations, but hosts the 1936 Summer Olympics1936 Summer OlympicsThe 1936 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XI Olympiad, was an international multi-sport event which was held in 1936 in Berlin, Germany. Berlin won the bid to host the Games over Barcelona, Spain on April 26, 1931, at the 29th IOC Session in Barcelona...

to show his new reich to the world as well as the supposed Athleticism of his AryanAryan raceThe Aryan race is a concept historically influential in Western culture in the period of the late 19th century and early 20th century. It derives from the idea that the original speakers of the Indo-European languages and their descendants up to the present day constitute a distinctive race or...

troops/athletes. - Neville ChamberlainNeville ChamberlainArthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1937–1940), attempts the appeasementAppeasementThe term appeasement is commonly understood to refer to a diplomatic policy aimed at avoiding war by making concessions to another power. Historian Paul Kennedy defines it as "the policy of settling international quarrels by admitting and satisfying grievances through rational negotiation and...

of Hitler in hope of avoiding war by allowing the dictator to annex the SudetenlandSudetenlandSudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

(the western regions of CzechoslovakiaCzechoslovakiaCzechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

). Later signing the Munich AgreementMunich AgreementThe Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

and promising constituents "Peace for our time". He was ousted in favor of Winston ChurchillWinston ChurchillSir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

in May 1940, after the Invasion of Norway. - The assassination of the German diplomat Ernst vom RathErnst vom RathErnst Eduard vom Rath was a German diplomat, remembered for his assassination in Paris in 1938 by a Jewish youth, Herschel Grynszpan. The assassination triggered Kristallnacht, the "Night of Broken Glass"....

by a German-born Polish Jew triggers the KristallnachtKristallnachtKristallnacht, also referred to as the Night of Broken Glass, and also Reichskristallnacht, Pogromnacht, and Novemberpogrome, was a pogrom or series of attacks against Jews throughout Nazi Germany and parts of Austria on 9–10 November 1938.Jewish homes were ransacked, as were shops, towns and...

(The Night of Broken Glass) held between the 9 to 10 November 1938 and carried out by the Hitler YouthHitler YouthThe Hitler Youth was a paramilitary organization of the Nazi Party. It existed from 1922 to 1945. The HJ was the second oldest paramilitary Nazi group, founded one year after its adult counterpart, the Sturmabteilung...

, the GestapoGestapoThe Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

and the SSSchutzstaffelThe Schutzstaffel |Sig runes]]) was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. Built upon the Nazi ideology, the SS under Heinrich Himmler's command was responsible for many of the crimes against humanity during World War II...

during which the Jewish population living in Nazi Germany and Austria were attacked – 91 Jews were murdered and 25,000 to 30,000 were arrested and placed in concentration camps. 267 synagogues were destroyed and thousands of homes and businesses were ransacked. Kristallnacht also served as a pretext and a means for the wholesale confiscation of firearms from German Jews. - Germany and Italy pursue territorial expansionist agendas. Germany demands the annexation of the Federal State of AustriaFederal State of AustriaThe Federal State of Austria refers to Austria from 1934 to 1938, according to its self-conception a non-party, in fact a single-party state led by the fascist Fatherland's Front...

and German-populated territories in Europe. From 1935 to 1936, Germany receives the SaarSaar (League of Nations)The Territory of the Saar Basin , also referred as the Saar or Saargebiet, was a region of Germany that was occupied and governed by Britain and France from 1920 to 1935 under a League of Nations mandate, with the occupation originally being under the auspices of the Treaty of Versailles...

, remilitarizes the RhinelandRhinelandHistorically, the Rhinelands refers to a loosely-defined region embracing the land on either bank of the River Rhine in central Europe....

. Italy initially opposes Germany's aims on Austria but the two countries resolve their differences in 1936 in the aftermath of Italy's diplomatic isolation following the start of the Second Italo-Abyssinian WarSecond Italo-Abyssinian WarThe Second Italo–Abyssinian War was a colonial war that started in October 1935 and ended in May 1936. The war was fought between the armed forces of the Kingdom of Italy and the armed forces of the Ethiopian Empire...

. Germany becoming Italy's only remaining ally. Germany and Italy improve relations by forming an alliance against communism in 1936 with the signing of the Anti-Comintern PactAnti-Comintern PactThe Anti-Comintern Pact was an Anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on November 25, 1936 and was directed against the Communist International ....

. Germany annexes Austria in the event known as the AnschlussAnschlussThe Anschluss , also known as the ', was the occupation and annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938....

. The annexation of SudetenlandSudetenlandSudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

followed after negotiations which resulted in the Munich AgreementMunich AgreementThe Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German annexation of Czechoslovakia's Sudetenland. The Sudetenland were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without...

of 1938. The Italian invasion of AlbaniaItalian invasion of AlbaniaThe Italian invasion of Albania was a brief military campaign by the Kingdom of Italy against the Albanian Kingdom. The conflict was a result of the imperialist policies of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini...

in 1939 succeeds in turning the Kingdom of AlbaniaAlbania under ItalyThe Albanian Kingdom existed as a protectorate of the Kingdom of Italy. It was practically a union between Italy and Albania, officially led by Italy's King Victor Emmanuel III and its government: Albania was led by Italian governors, after being militarily occupied by Italy, from 1939 until 1943...

to an Italian protectorateProtectorateIn history, the term protectorate has two different meanings. In its earliest inception, which has been adopted by modern international law, it is an autonomous territory that is protected diplomatically or militarily against third parties by a stronger state or entity...

. The vacant throne was claimed by Victor Emmanuel III of ItalyVictor Emmanuel III of ItalyVictor Emmanuel III was a member of the House of Savoy and King of Italy . In addition, he claimed the crowns of Ethiopia and Albania and claimed the titles Emperor of Ethiopia and King of Albania , which were unrecognised by the Great Powers...

. Germany receives the MemelKlaipėda RegionThe Klaipėda Region or Memel Territory was defined by the Treaty of Versailles in 1920 when it was put under the administration of the Council of Ambassadors...

territory from LithuaniaLithuaniaLithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

, occupies CzechoslovakiaCzechoslovakiaCzechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, and finally invades the Second Polish RepublicSecond Polish RepublicThe Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

. The final event resulting in the outbreak of World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. - Multiple countries in the Americas including Canada, CubaCubaThe Republic of Cuba is an island nation in the Caribbean. The nation of Cuba consists of the main island of Cuba, the Isla de la Juventud, and several archipelagos. Havana is the largest city in Cuba and the country's capital. Santiago de Cuba is the second largest city...

, and the United States controversially deny asylum to hundreds of Jewish German refugees on the MS St. Louis who are fleeing Germany in 1939 which under the Nazi regime was pursuing a racist agenda of anti-Semitic persecution. In the end, no country accepted the refugees and the ship returns to Germany with most of its passengers on board, while some commit suicide based on the prospect of returning to Nazi-run Germany.

United States

- Franklin D. RooseveltFranklin D. RooseveltFranklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

is elected President of the United StatesPresident of the United StatesThe President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

in November 1932. Roosevelt initiates a widespread social welfare strategy called the "New DealNew DealThe New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

" to combat the economic and social devastation of the Great DepressionGreat DepressionThe Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

. The economic agenda of the "New Deal" was a radical departure from previous laissez-faireLaissez-faireIn economics, laissez-faire describes an environment in which transactions between private parties are free from state intervention, including restrictive regulations, taxes, tariffs and enforced monopolies....

economics.

Colonization

- The Ethiopian EmpireEthiopian EmpireThe Ethiopian Empire also known as Abyssinia, covered a geographical area that the present-day northern half of Ethiopia and Eritrea covers, and included in its peripheries Zeila, Djibouti, Yemen and Western Saudi Arabia...

is invaded by the Kingdom of ItalyKingdom of Italy (1861–1946)The Kingdom of Italy was a state forged in 1861 by the unification of Italy under the influence of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which was its legal predecessor state...

during the Second Italo-Abyssinian WarSecond Italo-Abyssinian WarThe Second Italo–Abyssinian War was a colonial war that started in October 1935 and ended in May 1936. The war was fought between the armed forces of the Kingdom of Italy and the armed forces of the Ethiopian Empire...

from 1935 to 1936. The occupied territory merges with EritreaEritreaEritrea , officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa. Eritrea derives it's name from the Greek word Erethria, meaning 'red land'. The capital is Asmara. It is bordered by Sudan in the west, Ethiopia in the south, and Djibouti in the southeast...

and Italian SomalilandItalian SomalilandItalian Somaliland , also known as Italian Somalia, was a colony of the Kingdom of Italy from the 1880s until 1936 in the region of modern-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th century by the Somali Sultanate of Hobyo and the Majeerteen Sultanate, the territory was later acquired by Italy through various...

into the colony of Italian East AfricaItalian East AfricaItalian East Africa was an Italian colonial administrative subdivision established in 1936, resulting from the merger of the Ethiopian Empire with the old colonies of Italian Somaliland and Italian Eritrea. In August 1940, British Somaliland was conquered and annexed to Italian East Africa...

. - The Empire of JapanEmpire of JapanThe Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

captures ManchuriaManchuriaManchuria is a historical name given to a large geographic region in northeast Asia. Depending on the definition of its extent, Manchuria usually falls entirely within the People's Republic of China, or is sometimes divided between China and Russia. The region is commonly referred to as Northeast...

in 1931, creating the puppet statePuppet stateA puppet state is a nominal sovereign of a state who is de facto controlled by a foreign power. The term refers to a government controlled by the government of another country like a puppeteer controls the strings of a marionette...

of ManchukuoManchukuoManchukuo or Manshū-koku was a puppet state in Manchuria and eastern Inner Mongolia, governed under a form of constitutional monarchy. The region was the historical homeland of the Manchus, who founded the Qing Empire in China...

. A puppet government was created, with PuyiPuyiPuyi , of the Manchu Aisin Gioro clan, was the last Emperor of China, and the twelfth and final ruler of the Qing Dynasty. He ruled as the Xuantong Emperor from 1908 until his abdication on 12 February 1912. From 1 to 12 July 1917 he was briefly restored to the throne as a nominal emperor by the...

, the last Qing DynastyQing DynastyThe Qing Dynasty was the last dynasty of China, ruling from 1644 to 1912 with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917. It was preceded by the Ming Dynasty and followed by the Republic of China....

Emperor of China, installed as the nominal regent and emperor.

Decolonization and independence

- Mohandas Gandhi lead the non-violent SatyagrahaSatyagrahaSatyagraha , loosely translated as "insistence on truth satya agraha soul force" or "truth force" is a particular philosophy and practice within the broader overall category generally known as nonviolent resistance or civil resistance. The term "satyagraha" was conceived and developed by Mahatma...

movement in the Declaration of the Independence of India and the Salt MarchSalt SatyagrahaThe Salt March, also known as the Salt Satyagrahah began with the Dandi March on March 12, 1930, and was an important part of the Indian independence movement. It was a campaign of tax resistance and nonviolent protest against the British salt monopoly in colonial India, and triggered the wider...

in March 1930.

Disasters

- The German dirigible airshipAirshipAn airship or dirigible is a type of aerostat or "lighter-than-air aircraft" that can be steered and propelled through the air using rudders and propellers or other thrust mechanisms...

HindenburgLZ 129 HindenburgLZ 129 Hindenburg was a large German commercial passenger-carrying rigid airship, the lead ship of the Hindenburg class, the longest class of flying machine and the largest airship by envelope volume...

explodes in the sky above LakehurstLakehurstThere are a number of places named Lakehurst:*Lakehurst, New Jersey.*Lakehurst High School, a fictional school in Degrassi: The Next Generation*Lakehurst Mall, a defunct shopping complex in Waukegan, Illinois...

, New JerseyNew JerseyNew Jersey is a state in the Northeastern and Middle Atlantic regions of the United States. , its population was 8,791,894. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York, on the southeast and south by the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Pennsylvania and on the southwest by Delaware...

, United States on May 6, 1937. 36 people are killed. The event leads to an investigation of the explosion and the disaster causes major public distrust of the use of hydrogenHydrogenHydrogen is the chemical element with atomic number 1. It is represented by the symbol H. With an average atomic weight of , hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant chemical element, constituting roughly 75% of the Universe's chemical elemental mass. Stars in the main sequence are mainly...

-inflated airships and seriously damages the reputation of the Zeppelin companyLuftschiffbau ZeppelinLuftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH is a German company which, during the early 20th century, was a leader in the design and manufacture of rigid airships, specifically of the Zeppelin type. The company was founded by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin...

. - The New London SchoolNew London School explosionThe New London School explosion occurred on March 18, 1937, when a natural gas leak caused an explosion, destroying the London School of New London, Texas, a community in Rusk County previously known as "London". The disaster killed more than 295 students and teachers, making it the worst...

in New London, TexasNew London, TexasNew London is a city in Rusk County, Texas, United States. The population was 987 at the 2000 census.On March 18, 1937, the London School Explosion killed in excess of three hundred people...

is destroyed by an explosion, killing in excess of 300 students and teachers (1937). - The New England Hurricane of 1938New England Hurricane of 1938The New England Hurricane of 1938 was the first major hurricane to strike New England since 1869...

, which became a Category 5 hurricane before making landfall as a Category 3. The hurricane was estimated to have caused property losses estimated at US$306 million ($ 4.72 billion in 2010), killed between 682 and 800 people, and damaged or destroyed over 57,000 homes, including famed actress Katharine HepburnKatharine HepburnKatharine Houghton Hepburn was an American actress of film, stage, and television. In a career that spanned 62 years as a leading lady, she was best known for playing strong-willed, sophisticated women in both dramas and comedies...

's, who had been staying in her family's Old Saybrook, ConnecticutOld Saybrook, ConnecticutOld Saybrook is a town in Middlesex County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 10,367 at the 2000 census. It contains the incorporated borough of Fenwick, as well as the census-designated places of Old Saybrook Center and Saybrook Manor.-History:...

beach home when the hurricane struck. - The Dust BowlDust BowlThe Dust Bowl, or the Dirty Thirties, was a period of severe dust storms causing major ecological and agricultural damage to American and Canadian prairie lands from 1930 to 1936...

, or Dirty Thirties: a period of severe dust storms causing major ecological and agricultural damage to AmericanUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and Canadian prairiePrairiePrairies are considered part of the temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands biome by ecologists, based on similar temperate climates, moderate rainfall, and grasses, herbs, and shrubs, rather than trees, as the dominant vegetation type...

lands from 1930 to 1936 (in some areas until 1940). Caused by extreme droughtDroughtA drought is an extended period of months or years when a region notes a deficiency in its water supply. Generally, this occurs when a region receives consistently below average precipitation. It can have a substantial impact on the ecosystem and agriculture of the affected region...

, coupled with decades of extensive farming without crop rotationCrop rotationCrop rotation is the practice of growing a series of dissimilar types of crops in the same area in sequential seasons.Crop rotation confers various benefits to the soil. A traditional element of crop rotation is the replenishment of nitrogen through the use of green manure in sequence with cereals...

, fallow fields, cover crops, or other techniques to prevent erosion, and heavy winds, it affected an estimated 100000000 acres (404,686 km²) of land (traveling as far east as New YorkNew YorkNew York is a state in the Northeastern region of the United States. It is the nation's third most populous state. New York is bordered by New Jersey and Pennsylvania to the south, and by Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont to the east...

and the Atlantic OceanAtlantic OceanThe Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

), caused mass migration (which was the inspiration for the Pulitzer PrizePulitzer PrizeThe Pulitzer Prize is a U.S. award for achievements in newspaper and online journalism, literature and musical composition. It was established by American publisher Joseph Pulitzer and is administered by Columbia University in New York City...

winning The Grapes of WrathThe Grapes of WrathThe Grapes of Wrath is a novel published in 1939 and written by John Steinbeck, who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1940 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962....

by John SteinbeckJohn SteinbeckJohn Ernst Steinbeck, Jr. was an American writer. He is widely known for the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden and the novella Of Mice and Men...

), food shortages, multiple deaths and illness from sand inhalation (see History in Motion), and a severe reduction in the going wage rate. - The 1938 Yellow River flood1938 Yellow River floodThe 1938 Yellow River flood was a flood created by the Nationalist Government in central China during the early stage of the Second Sino-Japanese War in an attempt to halt the rapid advance of the Japanese forces...

pours out from HuayuankouHuayuankouHuayuankou is a town in Huiji District, used to be a ferry of the Yellow River in Zhengzhou, Henan, China.It has an area of 39 square kilometers and a population of 15,000....

, ChinaChinaChinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

in 1938, inundating 54000 km² (20,849.5 sq mi) of land, and takes an estimated 500,000 lives.

Assassinations

The 1930s were marked by several notable assassinations:- U.S. presidential candidate Huey LongHuey LongHuey Pierce Long, Jr. , nicknamed The Kingfish, served as the 40th Governor of Louisiana from 1928–1932 and as a U.S. Senator from 1932 to 1935. A Democrat, he was noted for his radical populist policies. Though a backer of Franklin D...

assassinated (1935). - Engelbert DollfussEngelbert DollfussEngelbert Dollfuss was an Austrian Christian Social and Patriotic Front statesman. Serving previously as Minister for Forest and Agriculture, he ascended to Federal Chancellor in 1932 in the midst of a crisis for the conservative government...

, Chancellor of AustriaChancellor of AustriaThe Federal Chancellor is the head of government in Austria. Its deputy is the Vice-Chancellor. Before 1918, the equivalent office was the Minister-President of Austria. The Federal Chancellor is considered to be the most powerful political position in Austrian politics.-Appointment:The...

and leading figure of AustrofascismAustrofascismAustrofascism is a term which is frequently used by historians to describe the authoritarian rule installed in Austria with the May Constitution of 1934, which ceased with the forcible incorporation of the newly-founded Federal State of Austria into Nazi Germany in 1938...

, is assassinated in 1934 by Austrian Nazis. Germany and Italy nearly clash over the issue of Austrian independence despite close ideological similarities of the Italian Fascist and Nazi regimes. - Alexander I of YugoslaviaAlexander I of YugoslaviaAlexander I , also known as Alexander the Unifier was the first king of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia as well as the last king of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes .-Childhood:...

is assassinated in 1934 during a visit to MarseilleMarseilleMarseille , known in antiquity as Massalia , is the second largest city in France, after Paris, with a population of 852,395 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Marseille extends beyond the city limits with a population of over 1,420,000 on an area of...

, France. His assassin was Vlado ChernozemskiVlado ChernozemskiVlado Chernozemski , born Velichko Dimitrov Kerin , was a Bulgarian revolutionary.Chernozemski also entered the region of Vardar Macedonia with IMRO bands and participated in more than 15 battles with the Serbian police....

, a member of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. The IMRO was a political organization that fought for secession of Vardar MacedoniaVardar MacedoniaVardar Macedonia is an area in the north of the Macedonia . The borders of the area are those of the Republic of Macedonia. It covers an area of...

from Yugoslavia.

International issues

- The NSDAP (Nazi Party) under Adolf HitlerAdolf HitlerAdolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

wins the German federal election, March 1933. Hitler becomes Chancellor of Germany. Following the 1934 death in office of Paul von HindenburgPaul von HindenburgPaul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg , known universally as Paul von Hindenburg was a Prussian-German field marshal, statesman, and politician, and served as the second President of Germany from 1925 to 1934....

, President of Germany, Hitler's cabinet passed a law proclaiming the presidency vacant and transferred the role and powers of the head of state to Hitler as Führer und ReichskanzlerFührerFührer , alternatively spelled Fuehrer in both English and German when the umlaut is not available, is a German title meaning leader or guide now most associated with Adolf Hitler, who modelled it on Benito Mussolini's title il Duce, as well as with Georg von Schönerer, whose followers also...

(leader and chancellor). The Weimar RepublicWeimar RepublicThe Weimar Republic is the name given by historians to the parliamentary republic established in 1919 in Germany to replace the imperial form of government...

effectively gives way to Nazi GermanyNazi GermanyNazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

, a Totalitarian autocratic national socialistNazismNazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

dictatorshipDictatorshipA dictatorship is defined as an autocratic form of government in which the government is ruled by an individual, the dictator. It has three possible meanings:...

. - The Great DepressionGreat DepressionThe Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

seriously affects the economic, political, and social aspects of society across the world. - Major conflict occurs across the world such as the Chaco WarChaco WarThe Chaco War was fought between Bolivia and Paraguay over control of the northern part of the Gran Chaco region of South America, which was incorrectly thought to be rich in oil. It is also referred to as La Guerra de la Sed in literary circles for being fought in the semi-arid Chaco...

, the Second Italo-Abyssinian WarSecond Italo-Abyssinian WarThe Second Italo–Abyssinian War was a colonial war that started in October 1935 and ended in May 1936. The war was fought between the armed forces of the Kingdom of Italy and the armed forces of the Ethiopian Empire...

, the Spanish Civil WarSpanish Civil WarThe Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

, the Chinese Civil WarChinese Civil WarThe Chinese Civil War was a civil war fought between the Kuomintang , the governing party of the Republic of China, and the Communist Party of China , for the control of China which eventually led to China's division into two Chinas, Republic of China and People's Republic of...

, the Second Sino-Japanese WarSecond Sino-Japanese WarThe Second Sino-Japanese War was a military conflict fought primarily between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. From 1937 to 1941, China fought Japan with some economic help from Germany , the Soviet Union and the United States...

, and the outbreak of World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

on September 1, 1939. - Collapse of the League of NationsLeague of NationsThe League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

as countries like Germany, the Kingdom of ItalyKingdom of Italy (1861–1946)The Kingdom of Italy was a state forged in 1861 by the unification of Italy under the influence of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which was its legal predecessor state...

, and the Empire of JapanEmpire of JapanThe Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

abdicate the League.

Europe

- In 1930, Miguel Primo de RiveraMiguel Primo de RiveraMiguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2nd Marquis of Estella, 22nd Count of Sobremonte, Knight of Calatrava was a Spanish dictator, aristocrat, and a military official who was appointed Prime Minister by the King and who for seven years was a dictator, ending the turno system of alternating...

, Prime Minister of Spain and head of a military dictatorshipMilitary dictatorshipA military dictatorship is a form of government where in the political power resides with the military. It is similar but not identical to a stratocracy, a state ruled directly by the military....

is forced to resign in response to a financial crisis. (Part of the Great DepressionGreat DepressionThe Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

). Alfonso XIII of SpainAlfonso XIII of SpainAlfonso XIII was King of Spain from 1886 until 1931. His mother, Maria Christina of Austria, was appointed regent during his minority...

, who had previously backed the dictatorship, attempts to return gradually to the previous system and restore his prestige. This failed utterly, as the King was considered a supporter of the dictatorship, and more and more political forces called for the establishment of a republic. In 1931, republican and socialist parties won a major victory in the local elections, while the monarchists were in decline. Street riots ensued, calling for the removal of the monarchy. The Spanish ArmySpanish ArmyThe Spanish Army is the terrestrial army of the Spanish Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is one of the oldest active armies - dating back to the 15th century.-Introduction:...

declared that they would not defend the King. Alfonso flees the country, effectively abdicating and ending the Bourbon RestorationSpain under the RestorationThe Restoration was the name given to the period that began on December 29, 1874 after the First Spanish Republic ended with the restoration of Alfonso XII to the throne after a coup d'état by Martinez Campos, and ended on April 14, 1931 with the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic.After...

phase which had started in the 1870s. A Second Spanish RepublicSecond Spanish RepublicThe Second Spanish Republic was the government of Spain between April 14 1931, and its destruction by a military rebellion, led by General Francisco Franco....

emerges. - In the Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

, agricultural collectivization and rapid industrialization take place. - More than 25 million people migrate to cities in the Soviet Union.

- Anglo-German Naval AgreementAnglo-German Naval AgreementThe Anglo-German Naval Agreement of June 18, 1935 was a bilateral agreement between the United Kingdom and German Reich regulating the size of the Kriegsmarine in relation to the Royal Navy. The A.G.N.A fixed a ratio whereby the total tonnage of the Kriegsmarine was to be 35% of the total tonnage...

is signed in 1935, removing the Treaty of VersaillesTreaty of VersaillesThe Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

' level of limitation on the size of the KriegsmarineKriegsmarineThe Kriegsmarine was the name of the German Navy during the Nazi regime . It superseded the Kaiserliche Marine of World War I and the post-war Reichsmarine. The Kriegsmarine was one of three official branches of the Wehrmacht, the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany.The Kriegsmarine grew rapidly...

(German NavyGerman NavyThe German Navy is the navy of Germany and is part of the unified Bundeswehr .The German Navy traces its roots back to the Imperial Fleet of the revolutionary era of 1848 – 52 and more directly to the Prussian Navy, which later evolved into the Northern German Federal Navy...

). The agreement allows Germany to build a larger naval force. - Éamon de ValeraÉamon de ValeraÉamon de Valera was one of the dominant political figures in twentieth century Ireland, serving as head of government of the Irish Free State and head of government and head of state of Ireland...

introduces a new constitutionConstitutionA constitution is a set of fundamental principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization is governed. These rules together make up, i.e. constitute, what the entity is...

for the Irish Free StateIrish Free StateThe Irish Free State was the state established as a Dominion on 6 December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed by the British government and Irish representatives exactly twelve months beforehand...

in 1937, effectively ending its status as a British DominionDominionA dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

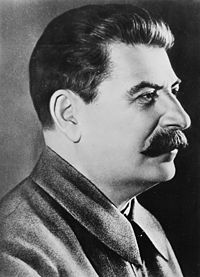

. - The "Great PurgeGreat PurgeThe Great Purge was a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in the Soviet Union orchestrated by Joseph Stalin from 1936 to 1938...

" of "Old Bolsheviks" from the Communist Party of the Soviet UnionCommunist Party of the Soviet UnionThe Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the only legal, ruling political party in the Soviet Union and one of the largest communist organizations in the world...

takes place from 1936 to 1938, as ordered by Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

leader Joseph StalinJoseph StalinJoseph Vissarionovich Stalin was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 6 May 1941 to 5 March 1953. He was among the Bolshevik revolutionaries who brought about the October Revolution and had held the position of first General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union's Central Committee...

, resulting in hundreds of thousands of people being killed. This purge was due to mistrust and political differences, as well as the massive drop in Grain produce. This was due to the method of collectivization in Russia. The Soviet Union produced 16 million lbs of grain less in 1934 compared to 1930. This led to the starvation of millions of Russians. - The 1937 World's FairExposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (1937)The Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne was held from May 25 to November 25, 1937 in Paris, France...

in ParisParisParis is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

, France displays the growing political tensions in Europe. The pavilions of the rival countries of Nazi GermanyNazi GermanyNazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and the Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

face each other. Germany at the time was internationally condemned for LuftwaffeLuftwaffeLuftwaffe is a generic German term for an air force. It is also the official name for two of the four historic German air forces, the Wehrmacht air arm founded in 1935 and disbanded in 1946; and the current Bundeswehr air arm founded in 1956....

(its air force) having performed a bombingBombing of GuernicaThe bombing of Guernica was an aerial attack on the Basque town of Guernica, Spain, causing widespread destruction and civilian deaths, during the Spanish Civil War...

of the Basque town of Guernica in Spain during the Spanish Civil WarSpanish Civil WarThe Spanish Civil WarAlso known as The Crusade among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War among Carlists, and The Rebellion or Uprising among Republicans. was a major conflict fought in Spain from 17 July 1936 to 1 April 1939...

. Spanish artist Pablo PicassoPablo PicassoPablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso known as Pablo Ruiz Picasso was a Spanish expatriate painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramicist, and stage designer, one of the greatest and most influential artists of the...

depicted the bombing in his masterpiece painting GuernicaGuernica (painting)Guernica is a painting by Pablo Picasso. It was created in response to the bombing of Guernica, Basque Country, by German and Italian warplanes at the behest of the Spanish Nationalist forces, on 26 April 1937, during the Spanish Civil War...

at the World Fair, which was a surrealistSurrealismSurrealism is a cultural movement that began in the early 1920s, and is best known for the visual artworks and writings of the group members....

depiction of the horror of the bombing.

Africa

Hertzog of South Africa, whose National Party had won the 1929 election alone, after splitting with the Labour Party, received much of the blame for the devastating economic impact of the depression.Americas

- Canada and other countries under the British EmpireBritish EmpireThe British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

sign the Statute of WestminsterStatute of Westminster 1931The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Passed on 11 December 1931, the Act established legislative equality for the self-governing dominions of the British Empire with the United Kingdom...

in 1931 establishing effective parliamentary independence of Canada from the parliament of the United Kingdom. - United States Marine CorpsUnited States Marine CorpsThe United States Marine Corps is a branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for providing power projection from the sea, using the mobility of the United States Navy to deliver combined-arms task forces rapidly. It is one of seven uniformed services of the United States...

general Smedley ButlerSmedley ButlerSmedley Darlington Butler was a Major General in the U.S. Marine Corps, an outspoken critic of U.S. military adventurism, and at the time of his death the most decorated Marine in U.S...

confesses to the U.S. Congress in 1934 that a group of industrialists contacted him, requesting his aid to overthrow the U.S. government of Roosevelt and establish what he claimed would be a fascist regime in the United States. - NewfoundlandNewfoundland and LabradorNewfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada. Situated in the country's Atlantic region, it incorporates the island of Newfoundland and mainland Labrador with a combined area of . As of April 2011, the province's estimated population is 508,400...

voluntarily returns to British colonial rule in 1934 amid its economic crisis during the Great Depression with the creation of the Commission of GovernmentCommission of GovernmentThe Commission of Government was a non-elected body that governed Newfoundland from 1934 to 1949...

, a non-elected body. - Canadian Prime MinisterPrime Minister of CanadaThe Prime Minister of Canada is the primary minister of the Crown, chairman of the Cabinet, and thus head of government for Canada, charged with advising the Canadian monarch or viceroy on the exercise of the executive powers vested in them by the constitution...

W. L. Mackenzie KingWilliam Lyon Mackenzie KingWilliam Lyon Mackenzie King, PC, OM, CMG was the dominant Canadian political leader from the 1920s through the 1940s. He served as the tenth Prime Minister of Canada from December 29, 1921 to June 28, 1926; from September 25, 1926 to August 7, 1930; and from October 23, 1935 to November 15, 1948...

meets with German FührerFührerFührer , alternatively spelled Fuehrer in both English and German when the umlaut is not available, is a German title meaning leader or guide now most associated with Adolf Hitler, who modelled it on Benito Mussolini's title il Duce, as well as with Georg von Schönerer, whose followers also...

Adolf HitlerAdolf HitlerAdolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

in 1937 in Berlin. King is the only North American head of government to meet with Hitler. - Amelia EarhartAmelia EarhartAmelia Mary Earhart was a noted American aviation pioneer and author. Earhart was the first woman to receive the U.S. Distinguished Flying Cross, awarded for becoming the first aviatrix to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean...

receives major attention in the 1930s as the first woman pilot to conduct major air flights. Her disappearance for unknown reasons in 1937 while on flight prompted search efforts which failed. - Southern Great PlainsGreat PlainsThe Great Plains are a broad expanse of flat land, much of it covered in prairie, steppe and grassland, which lies west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains in the United States and Canada. This area covers parts of the U.S...

devastated by decades-long Dust BowlDust BowlThe Dust Bowl, or the Dirty Thirties, was a period of severe dust storms causing major ecological and agricultural damage to American and Canadian prairie lands from 1930 to 1936... - In 1932 the Cipher Bureau broke the German Enigma cipher and overcame the ever-growing structural and operating complexities of the evolving Enigma machineEnigma machineAn Enigma machine is any of a family of related electro-mechanical rotor cipher machines used for the encryption and decryption of secret messages. Enigma was invented by German engineer Arthur Scherbius at the end of World War I...

with plugboardPlugboardA plugboard, or control panel , is an array of jacks, or hubs, into which patch cords can be inserted to complete an electrical circuit. Control panels were used to direct the operation of some unit record equipment...

, the main German cipher device during World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

. - Board of Temperance StrategyBoard of Temperance StrategyThe Anti-Saloon League launched the Board of Temperance Strategy to coordinate resistance to the growing public demand for the repeal of prohibition that was occurring in the U.S. in the early 1930s....

established in U.S. to fight repeal of prohibitionRepeal of ProhibitionThe Repeal of Prohibition in the United States was accomplished with the passage of the Twenty-first Amendment to the United States Constitution on December 5, 1933.-Background:... - Getúlio VargasGetúlio VargasGetúlio Dornelles Vargas served as President of Brazil, first as dictator, from 1930 to 1945, and in a democratically elected term from 1951 until his suicide in 1954. Vargas led Brazil for 18 years, the most for any President, and second in Brazilian history to Emperor Pedro II...

became the President of Brazil after the 1930 coup d'état.

Asia

- Major international media attention follows Mohandas Gandhi's peaceful resistanceNonviolent resistanceNonviolent resistance is the practice of achieving goals through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, and other methods, without using violence. It is largely synonymous with civil resistance...

movement against the British colonial rule in India. - Chinese Communist Party leader Mao ZedongMao ZedongMao Zedong, also transliterated as Mao Tse-tung , and commonly referred to as Chairman Mao , was a Chinese Communist revolutionary, guerrilla warfare strategist, Marxist political philosopher, and leader of the Chinese Revolution...

forms the small enclave state called the Chinese Soviet Republic in 1931. - The Gandhi–Irwin Pact is signed by Mohandas Gandhi and Viceroy of India, Lord IrwinE. F. L. Wood, 1st Earl of HalifaxEdward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, , known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and as The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was one of the most senior British Conservative politicians of the 1930s, during which he held several senior ministerial posts, most notably as...

on March 5, 1931. Gandhi agrees to end the campaign of civil disobedienceCivil disobedienceCivil disobedience is the active, professed refusal to obey certain laws, demands, and commands of a government, or of an occupying international power. Civil disobedience is commonly, though not always, defined as being nonviolent resistance. It is one form of civil resistance...

being carried out by the Indian National CongressIndian National CongressThe Indian National Congress is one of the two major political parties in India, the other being the Bharatiya Janata Party. It is the largest and one of the oldest democratic political parties in the world. The party's modern liberal platform is largely considered center-left in the Indian...

(INC) in exchange for Irwin accepting the INC to participate in roundtable talks on British colonial policy in India. - The Government of India Act of 1935Government of India Act 1935The Government of India Act 1935 was originally passed in August 1935 , and is said to have been the longest Act of Parliament ever enacted by that time. Because of its length, the Act was retroactively split by the Government of India Act 1935 into two separate Acts:# The Government of India...

is passed in the British RajBritish RajBritish Raj was the British rule in the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947; The term can also refer to the period of dominion...

, separating Burma into a separate British colony and increasing political autonomy of the princely states in India. - Mao Zedong's Chinese communists begin a large retreat from advancing nationalist forces, called the Long MarchLong MarchThe Long March was a massive military retreat undertaken by the Red Army of the Communist Party of China, the forerunner of the People's Liberation Army, to evade the pursuit of the Kuomintang army. There was not one Long March, but a series of marches, as various Communist armies in the south...

beginning in October 1934 and ending in October 1936 resulting in the collapse of the Chinese Soviet Republic. - Colonial India's Muslim League leader Muhammed Ali Jinnah delivers his "Day of DeliveranceDay of Deliverance (India)During the Indian Independence movement, Muslim League President Muhammad Ali Jinnah declared December 22, 1939 a "Day of Deliverance" for Indian Muslims...

" speech on December 2, 1939, calling upon Muslims to begin to engage in civil disobedience against the British colonial government starting on December 12. Jinnah demands redress and resolution to tensions and violence occurring between Muslims and Hindus in India. Jinnah's actions are not supported by the largely Hindu-dominated Indian National CongressIndian National CongressThe Indian National Congress is one of the two major political parties in India, the other being the Bharatiya Janata Party. It is the largest and one of the oldest democratic political parties in the world. The party's modern liberal platform is largely considered center-left in the Indian...

whom he had previously closely allied with. The decision is seen as part of an agenda by Jinnah to support the eventual creation of an independent Muslim state called PakistanPakistanPakistan , officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan is a sovereign state in South Asia. It has a coastline along the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman in the south and is bordered by Afghanistan and Iran in the west, India in the east and China in the far northeast. In the north, Tajikistan...

from British Empire.

Australia

- AustraliaAustraliaAustralia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

and New ZealandNew ZealandNew Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

sign the Statute of WestminsterStatute of Westminster 1931The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Passed on 11 December 1931, the Act established legislative equality for the self-governing dominions of the British Empire with the United Kingdom...

in 1931 which established legislative equality between the self-governing dominionDominionA dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

s of the British EmpireBritish EmpireThe British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

and the United KingdomUnited KingdomThe United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, with a few residual exceptions. The Parliament of AustraliaParliament of AustraliaThe Parliament of Australia, also known as the Commonwealth Parliament or Federal Parliament, is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It is bicameral, largely modelled in the Westminster tradition, but with some influences from the United States Congress...

and Parliament of New ZealandParliament of New ZealandThe Parliament of New Zealand consists of the Queen of New Zealand and the New Zealand House of Representatives and, until 1951, the New Zealand Legislative Council. The House of Representatives is often referred to as "Parliament".The House of Representatives usually consists of 120 Members of...

gain full legislative authority over their territories, no longer sharing powers with the Parliament of the United KingdomParliament of the United KingdomThe Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

.

Economics

- The Great DepressionGreat DepressionThe Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

occurred during the 1930s. - Economic interventionist policiesEconomic interventionismEconomic interventionism is an action taken by a government in a market economy or market-oriented mixed economy, beyond the basic regulation of fraud and enforcement of contracts, in an effort to affect its own economy...

increase in popularity as a result of the Great Depression in both authoritarian and democratic countries. In the western world, Keynesianism replaces classical economic theoryClassical economicsClassical economics is widely regarded as the first modern school of economic thought. Its major developers include Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, David Ricardo, Thomas Malthus and John Stuart Mill....

. - Rapid industrialization takes place in the Soviet UnionSoviet UnionThe Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....