Treatment of Polish citizens by occupiers

Encyclopedia

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

during the Second World War

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

(1939–1945) began with invasion of Poland in September 1939, and formally concluded with the defeat of Nazism by the Four Powers

End of World War II in Europe

The final battles of the European Theatre of World War II as well as the German surrender to the Western Allies and the Soviet Union took place in late April and early May 1945.-Timeline of surrenders and deaths:...

in May 1945. Throughout the entire course of foreign occupation the territory of Poland was divided between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (USSR). In summer-autumn of 1941 the lands annexed by the Soviets were overrun by Nazi Germany in the course of the initially successful German attack on the USSR

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

. After a few years of fighting, the Red Army

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

was able to repel the invaders and drive the Nazi forces

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

out of the USSR and across Poland from the rest of Eastern

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is the eastern part of Europe. The term has widely disparate geopolitical, geographical, cultural and socioeconomic readings, which makes it highly context-dependent and even volatile, and there are "almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region"...

and Central Europe

Central Europe

Central Europe or alternatively Middle Europe is a region of the European continent lying between the variously defined areas of Eastern and Western Europe...

.

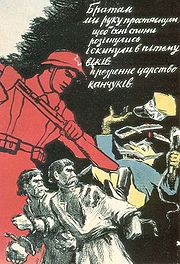

Both occupying powers were equally hostile to the existence of sovereign Poland

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

, her culture and the Polish people

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

, aiming at their destruction. Before Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union coordinated their Poland-related policies, most visibly in the four Gestapo-NKVD Conferences

Gestapo-NKVD Conferences

The Gestapo–NKVD conferences were a series of meetings organized in late 1939 and early 1940, whose purpose was the mutual cooperation between Nazi Germany and Soviet Union...

, where the occupants discussed plans for dealing with the Polish resistance movement

Polish resistance movement in World War II

The Polish resistance movement in World War II, with the Home Army at its forefront, was the largest underground resistance in all of Nazi-occupied Europe, covering both German and Soviet zones of occupation. The Polish defence against the Nazi occupation was an important part of the European...

and future destruction of Poland.

About 6 million Polish citizens – nearly 21.4% of Poland's population – died between 1939 and 1945 as a result of the occupation., many of whom were Jews

History of the Jews in Poland

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back over a millennium. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Jewish community in the world. Poland was the centre of Jewish culture thanks to a long period of statutory religious tolerance and social autonomy. This ended with the...

. Over 90% of the death toll came through non-military losses, as most of the civilians were targeted by various deliberate actions by Germans and the Soviets.

Occupation, annexation and administration

After Germany and the Soviet Union had partitioned Poland in 1939, most of the ethnically Polish territory ended up under the control of Germany while the areas annexed by the Soviet Union contained ethnically diverse peoples, with the territory split into bilingual provinces, some of which had a significant non-Polish majority (Ukrainians in the south and Belarusians in the north). Many of them welcomed the Soviets, alienated in the interwar PolandSecond Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

. Nonetheless Poles comprised the largest single ethnic group on all territories annexed by the Soviet Union.

Areas annexed by Germany

Under the terms of two decrees by Hitler, with Stalin's agreement (8 October and 12 October 1939), large areas of western Poland were annexed by GermanyPolish areas annexed by Nazi Germany

At the beginning of World War II, nearly a quarter of the pre-war Polish areas were annexed by Nazi Germany and placed directly under German civil administration, while the rest of Nazi occupied Poland was named as General Government...

. The size of these annexed territories was approximately 94,000 square kilometres with the population of about 10 million, the great majority of whom were Polish. Nearly 1 million Poles were expelled further east from this Nazi controlled area. Soon, 600,000 Germans from Eastern Europe and 400,000 from the Third Reich were settled there. The Nazis kept in place 1.7 million Poles deemed Germanizable, including between one and two hundred thousand children who had been taken from their parents. Duiker and Spielvogel note that by 1942, the number of new German arrivals in pre-war Poland had already reached two million.

Creation of General Government

The remaining block of territory was placed under a German administration called the General GovernmentGeneral Government

The General Government was an area of Second Republic of Poland under Nazi German rule during World War II; designated as a separate region of the Third Reich between 1939–1945...

(in German: Generalgouvernement für die besetzten polnischen Gebiete), with its capital at Kraków

Kraków

Kraków also Krakow, or Cracow , is the second largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in the Lesser Poland region, the city dates back to the 7th century. Kraków has traditionally been one of the leading centres of Polish academic, cultural, and artistic life...

. A German lawyer and prominent Nazi, Hans Frank

Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank was a German lawyer who worked for the Nazi party during the 1920s and 1930s and later became a high-ranking official in Nazi Germany...

, was appointed Governor-General of this occupied area on 26 October 1939. Frank oversaw the segregation of the Jews

History of the Jews in Poland

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back over a millennium. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Jewish community in the world. Poland was the centre of Jewish culture thanks to a long period of statutory religious tolerance and social autonomy. This ended with the...

into ghetto

Ghetto

A ghetto is a section of a city predominantly occupied by a group who live there, especially because of social, economic, or legal issues.The term was originally used in Venice to describe the area where Jews were compelled to live. The term now refers to an overcrowded urban area often associated...

s in the largest cities, particularly Warsaw

Warsaw

Warsaw is the capital and largest city of Poland. It is located on the Vistula River, roughly from the Baltic Sea and from the Carpathian Mountains. Its population in 2010 was estimated at 1,716,855 residents with a greater metropolitan area of 2,631,902 residents, making Warsaw the 10th most...

, and the use of Polish civilians as forced and compulsory labour in German war industries. In April 1940 Frank made the morbid announcement that Kraków should become racially "cleanest" of all cities under his rule.

Significant border changes were made after the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941, and in late 1944 and 1945, when Soviet Union regained control of those lands and moved further west, eventually taking over all Polish territories.

Soviet administration zone

By the end of the Polish Defensive War against the two invaders, the Soviet Union had taken over 52.1% of the territory of Poland (~200,000 km²), with over 13,700,000 people. The ethnic composition of these areas, according to Elżbieta Trela-Mazur, were as follows: 38% Poles (~5.1 million people), 37% Ukrainians, 14.5% Belarusians, 8.4% Jews, 0.9% Russians and 0.6% Germans. There were also 336,000 refugees who fled from areas occupied by Germany, most of them Jews (198,000). All territory invaded by the Red ArmyRed Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army started out as the Soviet Union's revolutionary communist combat groups during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1922. It grew into the national army of the Soviet Union. By the 1930s the Red Army was among the largest armies in history.The "Red Army" name refers to...

was annexed to the Soviet Union

Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union

Immediately after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, which marked the beginning of World War II, the Soviet Union invaded the eastern regions of the Second Polish Republic, which Poles referred to as the "Kresy," and annexed territories totaling 201,015 km² with a population of 13,299,000...

(after a rigged election

Elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus

Elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus, which took place on October 22, 1939, were an attempt to legitimate territorial gains of the Soviet Union, at the expense of the Second Polish Republic...

), with the exception of Wilno area, which was transferred to sovereign Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

. A small strip of land that was part of Hungary before 1914, was also given to Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

.

Treatment of Polish citizens under Nazi German occupation

From the beginning, the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany was intended as fulfillment of the plan described by Adolf HitlerAdolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

in his book Mein Kampf

Mein Kampf

Mein Kampf is a book written by Nazi leader Adolf Hitler. It combines elements of autobiography with an exposition of Hitler's political ideology. Volume 1 of Mein Kampf was published in 1925 and Volume 2 in 1926...

as the Lebensraum

Lebensraum

was one of the major political ideas of Adolf Hitler, and an important component of Nazi ideology. It served as the motivation for the expansionist policies of Nazi Germany, aiming to provide extra space for the growth of the German population, for a Greater Germany...

. The occupation goal was to turn former Poland into ethnically German "living space", as well as to exploit the material resources of the country and to maximise the use of Polish manpower as a reservoir of slave labour. The Polish nation was to be effectively reduced to the status of Serfdom

Serfdom

Serfdom is the status of peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to Manorialism. It was a condition of bondage or modified slavery which developed primarily during the High Middle Ages in Europe and lasted to the mid-19th century...

, its political, religious and intellectual leadership destroyed. One aspect of German policy in conquered Poland aimed to prevent its ethnically diverse population from uniting against Germany. In a top-secret memorandum, "The Treatment of Racial Aliens in the East", dated May 25, 1940, Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler was Reichsführer of the SS, a military commander, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. As Chief of the German Police and the Minister of the Interior from 1943, Himmler oversaw all internal and external police and security forces, including the Gestapo...

, head of the SS, wrote: "We need to divide Poland's many different ethnic groups

Demographics of Poland

The Demographics of Poland is about the demographic features of the population of Poland, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population....

up into as many parts and splinter groups as possible". Historians, J. Grabowski and Z.R. Grabowski wrote in 2004:

The GermanisationGermanisationGermanisation is both the spread of the German language, people and culture either by force or assimilation, and the adaptation of a foreign word to the German language in linguistics, much like the Romanisation of many languages which do not use the Latin alphabet...

of Polish territories occurred by deporting and exterminating the Jews, depriving Poles of their rights and supporting the local Germans and the ethnic Germans resettled from the East. The German minority living in this ethnically mixed region was required to adhere to strict codes of behaviour and was held accountable for all unauthorised contacts with their Polish and, even more so, their Jewish neighbours. The system of control and repression strove to isolate the various ethnic (‘racial’) groups, encouraging denunciations and thus instilling fear in the populace.

According to the 1931 Polish census, 66% of the prewar population of the country totaling 35 million inhabitants spoke Polish as their mother tongue. Most of them were Roman Catholics. Fifteen per cent were Ukrainians, 8.5% Jews, 4.7% Belarusians, and 2.2% Germans. Poland had a small middle and upper class of well-educated professionals, entrepreneurs, and landowners. Nearly 75% of the population were peasants or agricultural laborers, and another fifth, industrial workers.

In contrast to the Nazi policy of genocide targeting all of Poland's 3.3 million Jewish men, women, and children for elimination, Nazi plans for the Polish Catholic majority focused on the elimination or suppression of political, religious, and intellectual leaders

Intelligenzaktion

Intelligenzaktion was a genocidal action of Nazi Germany targeting Polish elites as part of elimination of potentially dangerous elements. It was an early measure of the Generalplan Ost. About 60,000 people were killed as the result of this operation...

. This policy had two aims: first, to prevent Polish elites from organizing resistance or from ever regrouping into a governing class; second, to exploit the less educated majority of peasants and workers as unskilled laborers in agriculture and industry. This was in spite of racial theory that regarded most Polish leaders as actually being of German blood, and partly because of it, on the grounds that German blood must not be used the service of a foreign nation.

From 1939-1941, the Germans deported en masse about 1,600,000 Poles, including 400,000 Jews. About 700,000 Poles were sent to Germany for forced labor, many to die there. And the most infamous German death camps had been located in Poland. Overall, during German occupation of pre-war Polish territory, 1939–1945, the Germans murdered 5,470,000-5,670,000 Poles, including nearly 3,000,000 Jews. Altogether, 2,500,000 Poles were subjected to expulsions, while 7.3% of the Polish population served as slave labor.

Generalplan Ost and expulsion of Poles

The fate of Poles in German-occupied Poland was decided in Generalplan OstGeneralplan Ost

Generalplan Ost was a secret Nazi German plan for the colonization of Eastern Europe. Implementing it would have necessitated genocide and ethnic cleansing to be undertaken in the Eastern European territories occupied by Germany during World War II...

. Generalplan Ost, essentially a grand plan for ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic orreligious group from certain geographic areas....

, was divided into two parts, the Kleine Planung ("Small Plan"), which covered actions which were to be taken during the war, and the Grosse Planung ("Big Plan"), which covered actions to be undertaken after the war was won. The plan envisaged differing percentages of the various conquered nations undergoing Germanisation

Germanisation

Germanisation is both the spread of the German language, people and culture either by force or assimilation, and the adaptation of a foreign word to the German language in linguistics, much like the Romanisation of many languages which do not use the Latin alphabet...

, expulsion into the depths of Russia, and other gruesome fates, the net effect of which would be to ensure that the conquered territories would take on an irrevocably German character.

In 10 years' time, the plan called for the extermination

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

, expulsion, enslavement

Slavery

Slavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

or Germanisation

Germanisation

Germanisation is both the spread of the German language, people and culture either by force or assimilation, and the adaptation of a foreign word to the German language in linguistics, much like the Romanisation of many languages which do not use the Latin alphabet...

of most or all Poles

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

and East Slavs

East Slavs

The East Slavs are Slavic peoples speaking East Slavic languages. Formerly the main population of the medieval state of Kievan Rus, by the seventeenth century they evolved into the Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian peoples.-Sources:...

still living behind the front line

Front line

A front line is the farthest-most forward position of an armed force's personnel and equipment - generally in respect of maritime or land forces. Forward Line of Own Troops , or Forward Edge of Battle Area are technical terms used by all branches of the armed services...

. Instead, 250 million Germans

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

would live in an extended Lebensraum ("living space") of the 1000-Year Reich (Tausendjähriges Reich / 1000-Year empire) . Fifty years after the war, under the Große Planung, Generalplan Ost foresaw the eventual expulsion and extermination of more than 50 million Slavs beyond the Ural Mountains

Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the Ural River and northwestern Kazakhstan. Their eastern side is usually considered the natural boundary between Europe and Asia...

.

By 1952, only about 3–4 million Poles were supposed to be left residing in the former Poland, and then only to serve as slaves for German settler

Settler

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established permanent residence there, often to colonize the area. Settlers are generally people who take up residence on land and cultivate it, as opposed to nomads...

s. They were to be forbidden to marry, the existing ban on any medical help to Poles in Germany would be extended, and eventually Poles would cease to exist.

Operation Tannenberg

During the 1939 German invasion of Poland, special action squads of SS and police (the EinsatzgruppenEinsatzgruppen

Einsatzgruppen were SS paramilitary death squads that were responsible for mass killings, typically by shooting, of Jews in particular, but also significant numbers of other population groups and political categories...

) were deployed in the rear, arresting or killing those civilians caught resisting the Germans or considered capable of doing so as determined by their position and social status. Tens of thousands of wealthy landowners, clergymen, and members of the intelligentsia — government officials, teachers, doctors, dentists, officers, journalists, and others (both Poles and Jews) — were either murdered in mass executions or sent to prisons and concentration camps. German army units and "self-defense" forces composed of Volksdeutsche also participated in executions of civilians. In many instances, these executions were reprisal actions that held entire communities collectively responsible for the killing of Germans.

In an action codenamed "Operation Tannenberg

Operation Tannenberg

Operation Tannenberg was the codename for one of the extermination actions directed at the Polish people during World War II, part of the Generalplan Ost...

" ("Unternehmen Tannenberg") in September and October 1939, an estimated 760 mass executions were carried out by Einsatzkommando

Einsatzkommando

During World War II, the Nazi German Einsatzkommandos were a sub-group of five Einsatzgruppen mobile killing squads—up to 3,000 men each—usually composed of 500-1,000 functionaries of the SS and Gestapo, whose mission was to kill Jews, Romani, communists and the NKVD collaborators in the captured...

s, resulting in the deaths of at least 20,000 of the most prominent Polish citizens. Expulsion and murder became commonplace.

Proscription lists (Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen

Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen

Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen – was the proscription list prepared by Germans, before the war, that identified more than 61,000 members of Polish elites: activists, intelligentsia, scholars, actors, former officers, and others, who were to be interned or...

) identified more than 61,000 Polish activists, intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

, actors, former officers, etc. who were to be interned or shot. Members of the German minority living in Poland assisted in preparing the lists.

The first part of the action started in August 1939 with the arrest and execution of about 2,000 activists of Polish minority organisations in Germany were arrested. The second part of the action started September 1, 1939 and ended in October resulting in at least 20,000 murdered in 760 mass executions by special units, Einsatzgruppen

Einsatzgruppen

Einsatzgruppen were SS paramilitary death squads that were responsible for mass killings, typically by shooting, of Jews in particular, but also significant numbers of other population groups and political categories...

, in addition to regular Wehrmacht units. In addition to these, a special formation was created out of the German minority living in Poland called Selbstschutz

Selbstschutz

Selbstschutz stands for two organisations:# A name used by a number of paramilitary organisations created by ethnic Germans in Central and Eastern Europe# A name for self-defence measures and units in ethnic German, Austrian, and Swiss civil defence....

, whose members trained in Germany prior to the war in diversion and guerilla fighting. The formation was responsible for many massacres and due to its bad reputation was dissolved by Nazi authorities after the September Campaign.

A-B Aktion

The Außerordentliche BefriedungsaktionAußerordentliche Befriedungsaktion

AB-Aktion , was a Nazi German campaign during World War II aimed to eliminate the intellectuals and the upper classes of the Polish people and of Polish nationhood. In the spring and summer of 1940, more than 30,000 Poles were arrested by the Nazi authorities in German-occupied Poland...

(AB-Aktion in short, German

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

for Special Pacification) was a German campaign during World War II aimed at Polish leaders and the intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

. In the spring and summer of 1940, more than 30,000 Poles were arrested by the German authorities of German-occupied Poland

General Government

The General Government was an area of Second Republic of Poland under Nazi German rule during World War II; designated as a separate region of the Third Reich between 1939–1945...

. Several thousand university professors, teachers, priests, and others were shot outside Warsaw, in the Kampinos

Kampinos

Kampinos is a village in Warsaw West County, Masovian Voivodeship, in east-central Poland. It is the seat of the gmina called Gmina Kampinos...

forest near Palmiry

Palmiry

Palmiry During World War II, between 1939 and 1943, the village and the surrounding forest was one of the sites of German mass executions of Jews, Polish intelligentsia, politicians and athletes, killed during the AB Action. Most of the victims were first arrested and tortured in the Pawiak prison...

, and inside the city at the Pawiak

Pawiak

Pawiak was a prison built in 1835 in Warsaw, Poland.During the January 1863 Uprising, it served as a transfer camp for Poles sentenced by Imperial Russia to deportation to Siberia....

prison. Most of the remainder were sent to various German concentration camps.

Suppression of the Roman Catholic Church and other religions

The Catholic Church in Poland was especially hard hit by the Nazis. The Roman Catholic ChurchRoman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

was suppressed throughout Poland because historically it had been one of the primary supporters of Polish nationalist forces fighting for Poland's independence from outside domination.

Throughout the country, monasteries, convents, seminaries, schools and other religious institutions were shut down.

The Germans treated the Church most harshly in the annexed regions, as they systematically closed churches there; most priests were either killed, imprisoned, or deported to the General Government. Between 1939 and 1945, an estimated 3,000 members of the Catholic clergy in Poland were killed; of these, 1,992 died in concentration camps, 787 of them at Dachau, including bishop Michał Kozal.

No exception was made for Poland's higher clergy. Bishop Michael Kozal of Wladislava died in Dachau; Bishop Nowowiejski

Antoni Julian Nowowiejski

Antoni Julian Nowowiejski was a Polish bishop of Płock , titular archbishop of Silyum, first secretary of Polish Episcopal Conference , honorary citizen of Płock and historian...

of Płock and his suffragan

Suffragan bishop

A suffragan bishop is a bishop subordinate to a metropolitan bishop or diocesan bishop. He or she may be assigned to an area which does not have a cathedral of its own.-Anglican Communion:...

Bishop Wetmanski both died in prison in Poland; Bishop Fulman of Lublin and his suffragan Bishop Goral were sent to a concentration camp in Germany.

In 1939, 80% of the Catholic clergy and five of the bishops of the Warthegau region had been deported to concentration camps. In Wrocław, 49.2% of the clergy were dead; in Chełmno, 47.8%; in Łódź, 36.8%; in Poznań, 31.1%. In the Warsaw diocese, 212 priests were killed; 92 were murdered in Wilno, 81 in Lwów, 30 in Kraków, 13 in Kielce. Seminarians who were not killed were shipped off to Germany as forced labor.

Of 690 priests in the Polish province of West Prussia, at least 460 were arrested. The remaining priests of the region fled their parishes. Of the arrested priests, 214 were executed, including the entire cathedral chapter of Pelplin. The rest were deported to the newly created General Government district in Central Poland. By 1940, only 20 priests were still serving their parishes in West Prussia.

Many nuns shared the same fate as priests. Some 400 nuns were imprisoned at Bojanowo concentration camp. Many were later sent to Germany as slave labor.

Of the city of Poznań's 30 churches and 47 chapels, the Nazis left two open to serve some 200,000 souls. Thirteen churches were simply locked and abandoned; six became warehouses; four, including the cathedral, were used as furniture storage centers. In Łódź, only four churches were allowed to remain open to serve 700,000 Catholics.

Nor were the small Evangelical churches of Poland spared. All the Protestant clergy of the Cieszyn region of Silesia

Cieszyn Silesia

Cieszyn Silesia or Těšín Silesia or Teschen Silesia is a historical region in south-eastern Silesia, centered around the towns of Cieszyn and Český Těšín and bisected by the Olza River. Since 1920 it has been divided between Poland and Czechoslovakia, and later the Czech Republic...

were arrested and sent to the death camps at Mauthausen, Buchenwald, Dachau and Oranienburg.

Among the Protestant martyrs were Karol Kulisz, director of the Evangelical Church's largest charitable organization, who died in Buchenwald in November 1939; Professor Edmund Bursche, a member of the Evangelical Faculty of Theology at the University of Warsaw, who died in the stone quarries of Mauthausen; and the 79-year-old Bishop of the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Poland, Juliusz Bursche

Juliusz Bursche

Juliusz Bursche was a bishop of the Evangelical-Augsburg Church in Poland. A vocal opponent of Nazi Germany, after the German invasion of Poland in 1939 he was arrested by the Germans, tortured, and sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp where he died.- Youth :Bursche was born as the first child...

, who died in solitary confinement in Berlin.

Abolition of secondary and higher education

As part of wider efforts to destroy Polish culture, the Germans closed or destroyed universities, schools, museums, libraries, and scientific laboratories. Many university professors, along with teachers, lawyers, intellectuals and other members of the Polish elite, were arrested and executed. They demolished hundreds of monuments to national heroes. To prevent the birth of a new generation of educated Poles, German officials decreed that Polish children's schooling end after a few years of elementary education.Himmler wrote in a May 1940 memorandum, "The sole goal of this schooling is to teach them simple arithmetic, nothing above the number 500; writing one's name; and the doctrine that it is divine law to obey the Germans. . . . I do not think that reading is desirable".

Germanization and expulsion of Poles

In the territories which were annexed to Nazi GermanyPolish areas annexed by Nazi Germany

At the beginning of World War II, nearly a quarter of the pre-war Polish areas were annexed by Nazi Germany and placed directly under German civil administration, while the rest of Nazi occupied Poland was named as General Government...

, the Nazis' goal was to achieve complete "Germanization" which would assimilate the territories politically, culturally, socially, and economically into the German Reich. They applied this policy most rigorously in western incorporated territories—the so-called Wartheland. There, the Germans closed even elementary schools where Polish was the language of instruction. They renamed streets and cities so that Łódź became Litzmannstadt, for example. They also seized tens of thousands of Polish enterprises, from large industrial firms to small shops, without payment to the owners. Signs posted in public places warned: "Entrance is forbidden to Poles, Jews, and dogs."

Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor , also known as Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia , which provided the Second Republic of Poland with access to the Baltic Sea, thus dividing the bulk of Germany from the province of East...

and transport them to the General Government. By the end of 1940, the SS had expelled 325,000 people without warning and plundered their property and belongings. Many elderly people and children died en route or in makeshift transit camps such as those in the towns of Potulice

Potulice

Potulice is a village in the administrative district of Gmina Nakło nad Notecią, within Nakło County, Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, in north-central Poland. It lies approximately south-east of Nakło nad Notecią and west of Bydgoszcz...

, Smukal, and Toruń

Torun

Toruń is an ancient city in northern Poland, on the Vistula River. Its population is more than 205,934 as of June 2009. Toruń is one of the oldest cities in Poland. The medieval old town of Toruń is the birthplace of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus....

. In 1941, the Germans expelled 45,000 more people, but they scaled back the program after the invasion of the Soviet Union in late June 1941. Trains used for resettlement were more urgently needed to transport soldiers and supplies to the front.

During the German occupation of Poland in World War II attempts to divide (Divide and rule

Divide and rule

In politics and sociology, divide and rule is a combination of political, military and economic strategy of gaining and maintaining power by breaking up larger concentrations of power into chunks that individually have less power than the one implementing the strategy...

) the Polish nation by the new rulers led to the postulation of a separate ethnicity called "Goralenvolk

Goralenvolk

Goralenvolk was the name given by the German Nazis in World War II during their occupation of Poland to the population of Podhale in the south near the Slovakian border. They postulated a different ethnicity for that population, in an effort to divide the Polish people. The word was derived from...

". In 1941, the German Nazis also started forceful enrollment of Kashubians

Kashubians

Kashubians/Kaszubians , also called Kashubs, Kashubes, Kaszubians, Kassubians or Cassubians, are a West Slavic ethnic group in Pomerelia, north-central Poland. Their settlement area is referred to as Kashubia ....

onto the Deutsche Volksliste due to losses in the Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

.

In late 1942 and in 1943, the SS also carried out massive expulsions in the General Government, uprooting 110,000 Poles from 300 villages in the Zamość

Zamosc

Zamość ukr. Замостя is a town in southeastern Poland with 66,633 inhabitants , situated in the south-western part of Lublin Voivodeship , about from Lublin, from Warsaw and from the border with Ukraine...

–Lublin

Lublin

Lublin is the ninth largest city in Poland. It is the capital of Lublin Voivodeship with a population of 350,392 . Lublin is also the largest Polish city east of the Vistula river...

region. Families were torn apart as able-bodied teens and adults were taken for forced labor and elderly, young, and disabled persons were moved to other localities. Tens of thousands were also imprisoned in the Auschwitz and Majdanek

Majdanek

Majdanek was a German Nazi concentration camp on the outskirts of Lublin, Poland, established during the German Nazi occupation of Poland. The camp operated from October 1, 1941 until July 22, 1944, when it was captured nearly intact by the advancing Soviet Red Army...

concentration camps.

Kidnapping of children

The Nazis kept an eye out for Polish children who possessed Aryan racial characteristics. Promising children were separated from their parents and sent to Łódź for further examination. If they passed the battery of racial, physical and psychological tests, they were sent on to Germany for "Germanization". As many as 4,454 children chosen for Germanization were given German names, forbidden to speak Polish, and reeducated in SS or other Nazi institutions. Few ever saw their parents again. Many more children were rejected as unsuitable for Germanization after failing to measure up to racial scientists' criteria for establishing "AryanAryan race

The Aryan race is a concept historically influential in Western culture in the period of the late 19th century and early 20th century. It derives from the idea that the original speakers of the Indo-European languages and their descendants up to the present day constitute a distinctive race or...

" ancestry. These children were shipped to orphanages or to Auschwitz where they were killed, most often by intercardiac injections of phenol

Phenol

Phenol, also known as carbolic acid, phenic acid, is an organic compound with the chemical formula C6H5OH. It is a white crystalline solid. The molecule consists of a phenyl , bonded to a hydroxyl group. It is produced on a large scale as a precursor to many materials and useful compounds...

.

An estimated total of 50,000 children were kidnapped in Poland, the majority taken from orphanages and foster homes in the annexed lands. Infants born to Polish women deported to Germany as farm and factory laborers, if deemed "racially valuable", were also usually taken from the mothers and subjected to Germanization. If an examination of the father and mother suggested that a "racially valuable" child might not result from the union, the mother was compelled to have an abortion, and if a born child did not pass muster, they would be removed to an Ausländerkinder-Pflegestätte

Ausländerkinder-Pflegestätte

Ausländerkinder-Pflegestätte , also Säuglingsheim, Entbindungsheim, were Third Reich institutions where babies and children, abducted from Eastern European forced laborers from 1943 to 1945, were kept.-Nazi policy:...

, where many died to the lack of food.

German People's List

The German People's List (Deutsche Volksliste) classified Polish citizens into four groups.- Group 1 included so-called ethnic Germans who had taken an active part in the struggle for the Germanization of Poland;

- Group 2 included those ethnic Germans who had not taken such an active part, but had "preserved" their German characteristics;

- Group 3 included individuals of alleged German stock who had become "Polonized", but whom it was believed, could be won back to Germany. This group also included persons of non-German descent married to Germans or members of non-Polish groups who were considered desirable for their political attitude and racial characteristics;

- Group 4 consisted of persons of German stock who had become politically merged with the Poles.

After registration in the List, individuals from Groups 1 and 2 automatically became German citizens. Those from Group 3 acquired German citizenship subject to revocation. Those from Group 4 received German citizenship through naturalization proceedings; resistance to Germanization constituted treason because "German blood must not be utilized in the interest of a foreign nation," and such people were sent to concentration camps. Persons ineligible for the List were classified as stateless, and all Poles from the occupied territory, that is from the Government General of Poland, as distinct from the incorporated territory, were classified as non-protected.

Concentration camps

Camps such as Auschwitz in Poland and Buchenwald in central Germany became administrative centers of huge networks of forced-labor camps. In addition to SS-owned enterprises (the German Armament Works, for example), private German firms — such as MesserschmittMesserschmitt

Messerschmitt AG was a famous German aircraft manufacturing corporation named for its chief designer, Willy Messerschmitt, and known primarily for its World War II fighter aircraft, notably the Bf 109 and Me 262...

, Junkers, Siemens

Siemens

Siemens may refer toSiemens, a German family name carried by generations of telecommunications industrialists, including:* Werner von Siemens , inventor, founder of Siemens AG...

, and IG Farben

IG Farben

I.G. Farbenindustrie AG was a German chemical industry conglomerate. Its name is taken from Interessen-Gemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG . The company was formed in 1925 from a number of major companies that had been working together closely since World War I...

— increasingly relied on forced laborers to boost war production. One of the most infamous of these camps was Auschwitz III, or Monowitz

Monowice

Monowitz , initially established as a subcamp of Nazi Germany's Auschwitz concentration camp, was one of the three main camps in the Auschwitz concentration camp system, with an additional 45 subcamps in the surrounding area...

, which supplied forced laborers to a synthetic rubber plant owned by IG Farben. Prisoners in all the concentration camps were literally worked to death.

Auschwitz (Oświęcim) became the main concentration camp for Poles after the arrival there on June 14, 1940, of 728 men transported from an overcrowded prison at Tarnów

Tarnów

Tarnów is a city in southeastern Poland with 115,341 inhabitants as of June 2009. The city has been situated in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship since 1999, but from 1975 to 1998 it was the capital of the Tarnów Voivodeship. It is a major rail junction, located on the strategic east-west connection...

. By March 1941, 10,900 prisoners were registered at the camp, most of them Poles. In September 1941, 200 ill prisoners, most of them Poles, along with 650 Soviet prisoners of war, were killed in the first gassing experiments at Auschwitz. Beginning in 1942, Auschwitz's prisoner population became much more diverse, as Jews and other "enemies of the state" from all over German-occupied Europe were deported to the camp.

The Polish scholar Franciszek Piper

Franciszek Piper

Franciszek Piper is a Polish scholar, historian and author. Most of his work concerns the Jewish Holocaust, especially the history of the concentration camps at Auschwitz. Dr. Piper is credited as one of the historians who helped establish a more accurate number of victims of Auschwitz-Birkenau...

, the chief historian of Auschwitz, has estimated that 140,000-150,000 Poles were brought to that camp between 1940 and 1945, and that 70,000-75,000 died there as victims of executions, of cruel medical experiments, and of starvation and disease. Some 100,000 Poles were deported to Majdanek

Majdanek

Majdanek was a German Nazi concentration camp on the outskirts of Lublin, Poland, established during the German Nazi occupation of Poland. The camp operated from October 1, 1941 until July 22, 1944, when it was captured nearly intact by the advancing Soviet Red Army...

, and tens of thousands of them died there. An estimated 20,000 Poles died at Sachsenhausen

Sachsenhausen concentration camp

Sachsenhausen or Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used primarily for political prisoners from 1936 to the end of the Third Reich in May, 1945. After World War II, when Oranienburg was in the Soviet Occupation Zone, the structure was used as an NKVD...

, 20,000 at Gross-Rosen, 30,000 at Mauthausen

Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp

Mauthausen Concentration Camp grew to become a large group of Nazi concentration camps that was built around the villages of Mauthausen and Gusen in Upper Austria, roughly east of the city of Linz.Initially a single camp at Mauthausen, it expanded over time and by the summer of 1940, the...

, 17,000 at Neuengamme, 10,000 at Dachau, and 17,000 at Ravensbrueck. In addition, tens of thousands were executed or died in other camps and prisons.

Forced labor

Labor shortages in the German war economy became critical especially after German defeat in the battle of Stalingrad in 1942–1943. This led to the increased use of prisoners as forced laborers in German industries. Especially in 1943 and 1944, hundreds of camps were established in or near industrial plants.Between 1939 and 1945, at least 1.5 million Polish citizens were transported to the Reich for labor, most of them against their will. Many were teenaged boys and girls. Although Germany also used forced laborers from Western Europe, Poles, along with other Eastern Europeans viewed as inferior, were subject to especially harsh discriminatory measures. They were forced to wear identifying purple P's sewn to their clothing, subjected to a curfew, and banned from public transportation. While the actual treatment accorded factory workers or farm hands often varied depending on the individual employer, Polish laborers as a rule were compelled to work longer hours for lower wages than Western Europeans, and in many cities they lived in segregated barracks behind barbed wire.

Polish identity cards

Polish identity cards were replaced by the "KennkarteKennkarte

Kennkarte was the basic identity document in use during the Third Reich era, first introduced in July 1938. They were normally obtained through a police precinct and had the corresponding issuing office and official’s stamps on them...

" (identifying card). Those who applied for it had to fill out an affidavit that they were not Jews. Ultimately, the Nazis' "New Order" in Poland would result in the death of 20% of the population, some 6 million people, half of them Jewish.

Resistance

In response to the German occupation, Poles organized the largest underground movement in Europe with more than 300 widely supported political and military groups and subgroups. Despite military defeat, the Polish government itself never surrendered. In 1940, the Polish government in ExilePolish government in Exile

The Polish government-in-exile, formally known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in Exile , was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which...

was established in London.

The Polish resistance movement

Polish resistance movement in World War II

The Polish resistance movement in World War II, with the Home Army at its forefront, was the largest underground resistance in all of Nazi-occupied Europe, covering both German and Soviet zones of occupation. The Polish defence against the Nazi occupation was an important part of the European...

fought against the occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany during World War II. Resistance to the Nazi German

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

occupation

Military occupation

Military occupation occurs when the control and authority over a territory passes to a hostile army. The territory then becomes occupied territory.-Military occupation and the laws of war:...

began almost at once, although there is little terrain in Poland suitable for guerilla operations. The Home Army

Armia Krajowa

The Armia Krajowa , or Home Army, was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II German-occupied Poland. It was formed in February 1942 from the Związek Walki Zbrojnej . Over the next two years, it absorbed most other Polish underground forces...

(in Polish Armia Krajowa or AK), loyal to the Polish government in exile

Polish government in Exile

The Polish government-in-exile, formally known as the Government of the Republic of Poland in Exile , was the government in exile of Poland formed in the aftermath of the Invasion of Poland of September 1939, and the subsequent occupation of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, which...

in London and a military arm of the Polish Secret State

Polish Secret State

The Polish Underground State is a collective term for the World War II underground resistance organizations in Poland, both military and civilian, that remained loyal to the Polish Government in Exile in London. The first elements of the Underground State were put in place in the final days of the...

, was formed from a number of smaller groups in 1942. From 1943 the AK was in competition with the People's Army

People's Army

People's Army was a title of several communist armed forces:* Czechoslovak People's Army* People's Army of Poland* Vietnam People's Army* National People's Army, of East Germany* Yugoslav People's Army* Korean People's Army...

(Polish Armia Ludowa or AL), backed by the Soviet Union and controlled by the Polish Workers' Party

Polish Workers' Party

The Polish Workers' Party was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland, and merged with the Polish Socialist Party in 1948 to form the Polish United Workers' Party.-History:...

(Polish Polska Partia Robotnicza or PPR). By 1944 the AK had some 380,000 men, although few arms: the AL was much smaller, numbering around 30,000 http://encyklopedia.pwn.pl/3804_1.html. By the summer of 1944 Polish underground forces numbered more than 300,000 http://www.polishembassy.ca/files/Polish%20Armed%20Forces%20in%20WWII%20eng.pdf.The Polish partisan

Partisan (military)

A partisan is a member of an irregular military force formed to oppose control of an area by a foreign power or by an army of occupation by some kind of insurgent activity...

groups (Leśni

Leśni

Leśni is one of the informal names applied to the anti-German partisan groups operating in occupied Poland during World War II. The groups were formed mostly by people who for various reasons could not operate from settlements they lived in and had to retreat to the forests...

) killed about 150,000 Axis during the occupation.

In August 1943 and March 1944, Polish Secret State announced their long-term plan, partially designed to counter attractiveness of some of communists' proposals. That plan promised a land reform

Land reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

, nationalisation of industrial base, demands for territorial compensation from Germany as well as re-establishment of pre-1939 eastern border. Thus the main difference between the Underground State and the communists, in terms of politics, amounted not to radical economic and social reforms, which were advocated by both sides, but to their attitudes towards national sovereignty, borders and Polish-Soviet relations.

Resistance groups inside Poland set up underground courts for trying collaborators and others deemed to be traitors to Poland. The resistance groups also set up clandestine schools

Education in Poland during World War II

This article covers the topic of underground education in Poland during World War II. Secret learning prepared new cadres for the post-war reconstruction of Poland and countered the German and Soviet threat to exterminate the Polish culture....

in response to the Germans' closing of many educational institutions. For example, the universities of Warsaw

University of Warsaw

The University of Warsaw is the largest university in Poland and one of the most prestigious, ranked as best Polish university in 2010 and 2011...

, Cracow, and Lvov

Lviv University

The Lviv University or officially the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv is the oldest continuously operating university in Ukraine...

all operated clandestinely.

Officers of the regular Polish army formed an underground armed force, the "Home Army" (Armia Krajowa

Armia Krajowa

The Armia Krajowa , or Home Army, was the dominant Polish resistance movement in World War II German-occupied Poland. It was formed in February 1942 from the Związek Walki Zbrojnej . Over the next two years, it absorbed most other Polish underground forces...

—AK). After preliminary organizational activities, including the training of fighters and stockpiling of weapons, the AK activated partisan units in many parts of Poland in 1943. A Communist underground resistance group, the "People's Guard" (Gwardia Ludowa

Gwardia Ludowa

Gwardia Ludowa or GL was a communist armed organisation in Poland, organised by the Soviet created Polish Workers Party. It was the largest military organization which refused to join the structures of the Polish Underground State. It was created in 1942 and in 1944 it was incorporated by the...

), also formed in 1942, but its military strength and influence were relatively weak compared to the Armia Krajowa.

When the arrival of the Soviet army seemed imminent, the AK launched an uprising in Warsaw

Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance Home Army , to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany. The rebellion was timed to coincide with the Soviet Union's Red Army approaching the eastern suburbs of the city and the retreat of German forces...

against the German army on August 1, 1944. After 63 days of bitter fighting, the Germans quashed the insurrection. The Polish resistance received little or no assistance from the Soviet army. The Soviet army had reached a point within a few hundred meters across the Vistula

Vistula

The Vistula is the longest and the most important river in Poland, at 1,047 km in length. The watershed area of the Vistula is , of which lies within Poland ....

River from the city on September 16, but failed to make further headway in the course of the Uprising, leading to accusations that they had deliberately stopped their advance because Stalin did not want the Uprising to succeed. The reasoning behind the allegation was that Stalin preferred to have the Polish resistance suppressed by the Nazis so as to weaken any forces that might resist Soviet domination after the war.

Nearly 250,000 Poles, most of them civilians, lost their lives in the Warsaw Uprising

Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance Home Army , to liberate Warsaw from Nazi Germany. The rebellion was timed to coincide with the Soviet Union's Red Army approaching the eastern suburbs of the city and the retreat of German forces...

. The Germans deported hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children to concentration camps. Many others were transported to the Reich for forced labor. Acting on Hitler's orders, German forces reduced the city to rubble, greatly extending the destruction begun during their suppression of the earlier armed uprising by Jewish fighters resisting deportation from the Warsaw ghetto

Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest of all Jewish Ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II. It was established in the Polish capital between October and November 15, 1940, in the territory of General Government of the German-occupied Poland, with over 400,000 Jews from the vicinity...

in April 1943.

Impact on the Polish population

The Polish civilian population suffered under German occupation in several ways. Large numbers were expelled from areas intended for German colonisation, and forced to resettle in the General-Government area. Hundreds of thousands of Poles were deported to Germany for forced labour in industry and agriculture, where many thousands died. Poles were also conscripted for labour in Poland, and were held in labour camps all over the country, again with a high death rate. There was a general shortage of food, fuel for heating and medical supplies, and there was a high death rate among the Polish population as a result. Finally, thousands of Poles were killed as reprisals for resistance attacks on German forces or for other reasons. In all, about 3 million (non-Jewish) Poles died as a result of the German occupation, more than 10% of the pre-war population. When this is added to the 3 million Polish Jews who were killed as a matter of policy by the Germans, Poland lost about 22% of its population, the highest proportion of any European country in World War II http://www.citinet.net/ak/polska_55_f2.html.Some three million non-Jewish Polish

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

citizens perished during the course of the war, over two million of whom were ethnic Poles (the remainder being mostly Ukrainians

Ukrainians

Ukrainians are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine, which is the sixth-largest nation in Europe. The Constitution of Ukraine applies the term 'Ukrainians' to all its citizens...

and Belarusians

Belarusians

Belarusians ; are an East Slavic ethnic group who populate the majority of the Republic of Belarus. Introduced to the world as a new state in the early 1990s, the Republic of Belarus brought with it the notion of a re-emerging Belarusian ethnicity, drawn upon the lines of the Old Belarusian...

). The vast majority of those killed were civilian

Civilian

A civilian under international humanitarian law is a person who is not a member of his or her country's armed forces or other militia. Civilians are distinct from combatants. They are afforded a degree of legal protection from the effects of war and military occupation...

s, mostly killed by the actions of Nazi Germany.

Rather than being sent to concentration camps, most non-Jewish Poles died through in mass executions, starvation, singled out murder cases, ill health or forced labour. Apart from Auschwitz, the main six "extermination camps" in Poland were used almost exclusively to kill Jews. There was also camp Stutthof concentration camp

Stutthof concentration camp

Stutthof was the first Nazi concentration camp built outside of 1937 German borders.Completed on September 2, 1939, it was located in a secluded, wet, and wooded area west of the small town of Sztutowo . The town is located in the former territory of the Free City of Danzig, 34 km east of...

used for mass extermination of Poles. There was a number of civilian labour camps (Gemeinschaftslager) for Poles (Polenlager) on the territory of Poland. Many Poles did die in German camps. The first non-German prisoners at Auschwitz were Poles, who were the majority of inmates there until 1942, when the systematic killing of the Jews began. The first killing by poison gas at Auschwitz involved 300 Poles and 700 Soviet prisoners of war, among them ethnic Ukrainians, Russians and others. Many Poles and other Eastern Europeans were also sent to concentration camps in Germany: over 35,000 to Dachau, 33,000 to the camp for women at Ravensbrück

Ravensbrück concentration camp

Ravensbrück was a notorious women's concentration camp during World War II, located in northern Germany, 90 km north of Berlin at a site near the village of Ravensbrück ....

, 30,000 to Mauthausen

Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp

Mauthausen Concentration Camp grew to become a large group of Nazi concentration camps that was built around the villages of Mauthausen and Gusen in Upper Austria, roughly east of the city of Linz.Initially a single camp at Mauthausen, it expanded over time and by the summer of 1940, the...

and 20,000 to Sachsenhausen

Sachsenhausen concentration camp

Sachsenhausen or Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used primarily for political prisoners from 1936 to the end of the Third Reich in May, 1945. After World War II, when Oranienburg was in the Soviet Occupation Zone, the structure was used as an NKVD...

, for example.

The population in the General Government's territory was initially about 12 million in an area of 94,000 square kilometres, but this increased as about 860,000 Poles and Jews were expelled from the German-annexed areas and "resettled" in the General Government. Offsetting this was the German campaign of extermination of the Polish intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

and other elements thought likely to resist (e.g. Operation Tannenberg

Operation Tannenberg

Operation Tannenberg was the codename for one of the extermination actions directed at the Polish people during World War II, part of the Generalplan Ost...

). From 1941, disease and hunger also began to reduce the population. Poles were also deported in large numbers to work as forced labour in Germany: eventually about a million were deported, and many died in Germany.

About one fifth of Polish citizens lost their lives in the war http://books.google.com/books?ie=UTF-8&vid=ISBN0786403713&id=A4FlatJCro4C&pg=PA305&lpg=PA305&dq=poland+second+world+war+losses&sig=obpXqNW40aSskoue-XWLfdoEZaI, most of the civilians targeted by various deliberate actions.

Treatment of Polish citizens under Soviet occupation

Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union

Immediately after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, which marked the beginning of World War II, the Soviet Union invaded the eastern regions of the Second Polish Republic, which Poles referred to as the "Kresy," and annexed territories totaling 201,015 km² with a population of 13,299,000...

, with the exception of area of Wilno, which was transferred to Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

, although soon attached to USSR, when Lithuania

Lithuanian SSR

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic , also known as the Lithuanian SSR, was one of the republics that made up the former Soviet Union...

became a Soviet republic

Republics of the Soviet Union

The Republics of the Soviet Union or the Union Republics of the Soviet Union were ethnically-based administrative units that were subordinated directly to the Government of the Soviet Union...

.

Initially the Soviet occupation gained support among some members the non-Polish population who had chafed under the nationalist policies of the Second Polish Republic. Much of the Ukrainian population initially welcomed the unification with the rest of Ukraine which Ukrainians had failed to achieve in 1919 when their attempt for self-determination was crushed by Poland

Polish-Ukrainian War

The Polish–Ukrainian War of 1918 and 1919 was a conflict between the forces of the Second Polish Republic and West Ukrainian People's Republic for the control over Eastern Galicia after the dissolution of Austria-Hungary.-Background:...

and Soviet Union.

There were large groups of pre-war Polish citizens, notably Jewish youth and, to a lesser extent, the Ukrainian peasants, who saw the Soviet power as an opportunity to start political or social activity outside of their traditional ethnic or cultural groups. Their enthusiasm however faded with time as it became clear that the Soviet repressions were aimed at all groups equally, regardless of their political stance.

British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore

Simon Sebag Montefiore

Simon Jonathan Sebag Montefiore is a British historian and writer.-Family history:Simon's father, a doctor, is descended from a famous line of wealthy Sephardic Jews who became diplomats and bankers all over Europe...

states that Soviet terror in the occupied eastern Polish lands was as cruel and tragic as Nazi in the west. Soviet authorities brutally treated those who might oppose their rule, deporting by November 10, 1940, around 10% of total population of Kresy, with 30% of those deported dead by 1941. They arrested and imprisoned about 500,000 Poles during 1939–1941, including former officials, officers, and natural "enemies of the people", like the clergy, but also noblemen and intellectuals. The Soviets also executed about 65,000 Poles. Soldiers of the Red Army and their officers behaved like conquerors, looting and stealing Polish treasures. When Stalin was told about it, he answered: "If there is no ill will, they [the soldiers] can be pardoned".

In one notorious massacre, the NKVD-the Soviet secret police—systematically executed 21,768 Poles, among them 14,471 former Polish officers, including political leaders, government officials, and intellectuals. Some 4,254 of these were uncovered in mass graves in Katyn Forest by the Nazis in 1943, who then invited an international group of neutral representatives and doctors to study the corpses and confirm Soviet guilt, but the findings from the study were denounced by the Allies as "Nazi propaganda".

The Soviet Union had ceased to recognise the Polish state at the start of the invasion. As a result, the two governments never officially declared war on each other. The Soviets therefore did not classify Polish military prisoners as prisoners of war but as rebels against the new legal government of Western Ukraine and Western Byelorussia. The Soviets killed tens of thousands of Polish prisoners of war. Some, like General Józef Olszyna-Wilczyński

Józef Olszyna-Wilczynski

Józef Konstanty Olszyna-Wilczyński was a Polish general and one of the high-ranking commanders of the Polish Army. A veteran of World War I, Polish-Ukrainian War and the Polish-Bolshevik War, he was murdered by the Soviets during the Polish Defensive War of 1939.-Early life:Józef Wilczyński was...

, who was captured, interrogated and shot on 22 September, were executed during the campaign itself. On 24 September, the Soviets killed 42 staff and patients of a Polish military hospital in the village of Grabowiec

Grabowiec, Zamosc County

Grabowiec is a village in Zamość County, Lublin Voivodeship, in eastern Poland. It is the seat of the gmina called Gmina Grabowiec. It lies approximately north-east of Zamość and south-east of the regional capital Lublin....

, near Zamość

Zamosc

Zamość ukr. Замостя is a town in southeastern Poland with 66,633 inhabitants , situated in the south-western part of Lublin Voivodeship , about from Lublin, from Warsaw and from the border with Ukraine...

. The Soviets also executed all the Polish officers they captured after the Battle of Szack

Battle of Szack

Battle of Szack was one of the major battles between the Polish Army and the Red Army fought in 1939 in the beginning the Second World War.- Eve of the Battle :...

, on 28 September. Over 20,000 Polish military personnel and civilians perished in the Katyn massacre

Katyn massacre

The Katyn massacre, also known as the Katyn Forest massacre , was a mass execution of Polish nationals carried out by the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs , the Soviet secret police, in April and May 1940. The massacre was prompted by Lavrentiy Beria's proposal to execute all members of...

.

The Poles and the Soviets re-established diplomatic relations in 1941, following the Sikorski-Mayski Agreement

Sikorski-Mayski Agreement

The Sikorski–Mayski Agreement was a treaty between the Soviet Union and Poland signed in London on 30 July 1941. Its name was coined after the two most notable signatories: Polish Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski and Soviet Ambassador to the United Kingdom Ivan Mayski.- Details :After signing...

; but the Soviets broke them off again in 1943 after the Polish government demanded an independent examination of the recently discovered Katyn burial pits. The Soviets then lobbied the Western Allies to recognize the pro-Soviet Polish puppet government of Wanda Wasilewska

Wanda Wasilewska

Wanda Wasilewska was a Polish and Soviet novelist and communist political activist who played an important role in the creation of a Polish division of the Soviet Red Army during World War II and the formation of the Polish People's Republic....

in Moscow.

On 28 September 1939, the Soviet Union and Germany had changed the secret terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

. They moved Lithuania

Lithuania

Lithuania , officially the Republic of Lithuania is a country in Northern Europe, the biggest of the three Baltic states. It is situated along the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea, whereby to the west lie Sweden and Denmark...

into the Soviet sphere of influence

Sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence is a spatial region or conceptual division over which a state or organization has significant cultural, economic, military or political influence....

and shifted the border in Poland to the east, giving Germany more territory. By this arrangement, often described as a fourth partition of Poland, the Soviet Union secured almost all Polish territory east of the line of the rivers Pisa, Narew, Western Bug and San. This amounted to about 200,000 square kilometres of land, inhabited by 13.5 million Polish citizens.

The Red Army had originally sowed confusion among the locals by claiming that they were arriving to save Poland from the Nazis. Their advance surprised Polish communities and their leaders, who had not been advised how to respond to a Bolshevik invasion. Polish and Jewish citizens may at first have preferred a Soviet regime to a German one, but the Soviets soon proved as hostile and destructive towards the Polish people and their culture as the Nazis. They began confiscating, nationalising and redistributing all private and state-owned Polish property. During the two years following the annexation, they arrested approximately 100,000 Polish citizens and deported between 350,000 and 1,500,000, of whom between 150,000 and 1,000,000 died, mostly civilians.

Land reform and collectivisation

The Soviet base of support was even strengthened by a land reformLand reform

[Image:Jakarta farmers protest23.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Farmers protesting for Land Reform in Indonesia]Land reform involves the changing of laws, regulations or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution,...

program initiated by the Soviets in which most of the owners of large lots of land were labeled "kulak

Kulak

Kulaks were a category of relatively affluent peasants in the later Russian Empire, Soviet Russia, and early Soviet Union...

s" and dispossessed of their land which was then divided among poorer peasants.

However, the Soviet authorities then started a campaign of forced collectivisation, which largely nullified the earlier gains from the land reform as the peasants generally did not want to join the Kolkhoz

Kolkhoz

A kolkhoz , plural kolkhozy, was a form of collective farming in the Soviet Union that existed along with state farms . The word is a contraction of коллекти́вное хозя́йство, or "collective farm", while sovkhoz is a contraction of советское хозяйство...

farms, nor to give away their crops for free to fulfill the state-imposed quotas.

Restructuring of Polish governmental and social institutions

While Germans enforced their policies based on racismRacism

Racism is the belief that inherent different traits in human racial groups justify discrimination. In the modern English language, the term "racism" is used predominantly as a pejorative epithet. It is applied especially to the practice or advocacy of racial discrimination of a pernicious nature...

, the Soviet administration justified their Stalinist

Stalinism

Stalinism refers to the ideology that Joseph Stalin conceived and implemented in the Soviet Union, and is generally considered a branch of Marxist–Leninist ideology but considered by some historians to be a significant deviation from this philosophy...

policies by appealing to the Soviet ideology, which in reality meant the thorough Sovietization

Sovietization

Sovietization is term that may be used with two distinct meanings:*the adoption of a political system based on the model of soviets .*the adoption of a way of life and mentality modelled after the Soviet Union....

of the area. Immediately after their conquest of eastern Poland, the Soviet authorities started a campaign of sovietization

Sovietization

Sovietization is term that may be used with two distinct meanings:*the adoption of a political system based on the model of soviets .*the adoption of a way of life and mentality modelled after the Soviet Union....

of the newly-acquired areas. No later than several weeks after the last Polish units surrendered, on October 22, 1939, the Soviets organized staged elections to the Moscow-controlled Supreme Soviet

Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union was the Supreme Soviet in the Soviet Union and the only one with the power to pass constitutional amendments...

s (legislative body) of Western Byelorussia and Western Ukraine. The result of the staged voting was to become a legitimization of Soviet annexation of eastern Poland.

Subsequently, all institutions of the dismantled Polish state were being closed down and reopened under the Soviet appointed supervisors. Lviv University

Lviv University

The Lviv University or officially the Ivan Franko National University of Lviv is the oldest continuously operating university in Ukraine...