France in the nineteenth century

Encyclopedia

The History of France from 1789 to 1914 (the long 19th century

) extends from the French Revolution

to World War I and includes:

and the city of Nice

(first during the First Empire, and then definitively in 1860) and some small papal (like Avignon

) and foreign possessions. France's territorial limits were greatly extended during the Empire through Napoléon Bonaparte's military conquests and re-organization of Europe, but these were reversed by the Vienna Congress. With the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War

of 1870, France lost her provinces of Alsace

and portions of Lorraine

to Germany (see Alsace-Lorraine

); these lost provinces would only be regained at the end of World War I.

In 1830, France invaded Algeria

, and in 1848 this north African country was fully integrated into France as a département. The late nineteenth century saw France embark on a massive program of overseas imperialism — including French Indochina

(modern day Cambodia

, Vietnam

and Laos

) and Africa (the Scramble for Africa

brought France most of North-West and Central Africa) — which brought it in direct competition with British interests.

Until 1850, population growth was mainly in the countryside, but a period of massive urbanization

began under the Second Empire. Unlike in England, industrialization was a late phenomenon in France. The Napoleonic wars

had hindered early industrialization and France's economy in the 1830s (limited iron industry, under-developed coal supplies, a massive rural population) had not developed sufficiently to support an industrial expansion of any scope. French rail transport

only began hesitantly in the 1830s, and would not truly develop until the 1840s. By the revolution of 1848, a growing industrial workforce began to participate actively in French politics, but their hopes were largely betrayed by the policies of the Second Empire. The loss of the important coal, steel and glass production regions of Alsace and Lorraine would cause further problems. The industrial worker population increased from 23% in 1870 to 39% in 1914. Nevertheless, France remained a rather rural country in the early 1900s with 40% of the population still farmers in 1914. While exhibiting a similar urbanization rate as the U.S. (50% of the population in the U.S. was engaged in agriculture in the early 1900s), the urbanization rate of France was still well behind the one of the UK (80% urbanization rate in the early 1900s).

In the 19th century, France was a country of immigration for peoples and political refugees from Eastern Europe (Germany, Poland, Hungary, Russia, Ashkenazi Jews

) and from the Mediterranean (Italy, Spanish Sephardic Jews and North-African Mizrahi Jews

).

France was the first country in Europe to emancipate its Jewish population during the French Revolution. In 1872, there were an estimated 86,000 Jews living in France (by 1945 this would increase to 300,000), many of whom integrated (or attempted to integrate) into French society, although the Dreyfus affair

would reveal anti-semitism in certain classes of French society (see History of the Jews in France

).

With the loss of Alsace and Lorraine, 5000 French refugees from these regions emigrated to Algeria

in the 1870s and 1880s, as did too other Europeans (Spain, Malta) seeking opportunity. In 1889, non-French Europeans in Algeria were granted French citizenship (Arabs would however only win political rights in 1947).

Unlike other European countries, France did not experience a strong population growth in the mid and late 19th century and first half of the 20th century (see Demographics of France

). This would be compounded by the massive French losses of World War I — roughly estimated at 1.4 million French dead including civilians (see World War I casualties

) (or nearly 10% of the active adult male population) and four times as many wounded (see World War I Aftermath).

) and other inhabitants spoke Breton

, Catalan

, Basque

, Dutch

(West Flemish

), Franco-provençal

, Alsatian

and Corsican

. In the north of France, regional dialects of the various langues d'oïl

continued to be spoken in rural communities. France would only become a linguistically unified country by the end of the 19th century, and in particular through the educational policies of Jules Ferry

during the French Third Republic

. From an illiteracy rate of 33% among peasants in 1870, by 1914 almost all French could read and understand the national language, although 50% continued to understand or speak a regional language of France (in today's France, only an estimated 10% still understand a regional language

).

has put it) from a "country of peasants into a nation of Frenchmen".(Weber, E., 1979.) By 1914, most French could read French and regional languages had been greatly suppressed; the role of the Catholic Church in public life had been radically altered; a sense of national identity and glory was actively taught. The anti-clericalism of the Third Republic profoundly changed French religious habits: in one case study for the city of Limoges

comparing the years 1899 with 1914, it was found that baptisms decreased from 98% to 60%, and civil marriages before a town official increased from 14% to 60%. Yet, the eradication of regionalisms and the anti-clerical nature of the Third Republic would create a backlash in the second half of the century.

(1774–1792) saw a temporary revival of French fortunes, but the over-ambitious projects and military campaigns of the 18th century had produced chronic financial problems. Deteriorating economic conditions, popular resentment against the complicated system of privileges granted the nobility and clerics, and a lack of alternate avenues for change were among the principal causes for convoking the Estates-General

which convened in Versailles

in 1789. On May 28, 1789 the Abbé Sieyès

moved that the Third Estate proceed with verification of its own powers and invite the other two estates to take part, but not to wait for them. They proceeded to do so, and then voted a measure far more radical, declaring themselves the National Assembly

, an assembly not of the Estates but of "the People".

Louis XVI shut the Salle des États where the Assembly met. The Assembly moved their deliberations to the king's tennis court, where they proceeded to swear the Tennis Court Oath

(June 20, 1789), under which they agreed not to separate until they had given France a constitution

. A majority of the representatives of the clergy soon joined them, as did forty-seven members of the nobility. By June 27 the royal party had overtly given in, although the military began to arrive in large numbers around Paris and Versailles. On July 9 the Assembly reconstituted itself as the National Constituent Assembly

.

On July 11, 1789 King Louis, acting under the influence of the conservative nobles, as well as his wife, Marie Antoinette

, and brother, the Comte d'Artois

, banished the reformist minister Necker

and completely reconstructed the ministry. Much of Paris, presuming this to be the start of a royal coup, moved into open rebellion. Some of the military joined the mob; others remained neutral. On July 14, 1789, after four hours of combat, the insurgents seized the Bastille

fortress, killing the governor and several of his guards. The king and his military supporters backed down, at least for the time being. After this violence, nobles started to flee the country as émigré

s, some of whom began plotting civil war within the kingdom and agitating for a European coalition against France. Insurrection and the spirit of popular sovereignty

spread throughout France. In rural areas, many went beyond this: some burned title-deeds and no small number of châteaux

, as part of a general agrarian insurrection known as "la Grande Peur" (the Great Fear).

On August 4, 1789, the National Assembly abolished feudalism

, sweeping away both the seigneurial rights of the Second Estate and the tithe

s gathered by the First Estate. In the course of a few hours, nobles, clergy, towns, provinces, companies, and cities lost their special privileges. The revolution also brought about a massive shifting of powers from the Roman Catholic Church

to the State. Legislation enacted in 1790 abolished the Church's authority to levy a tax

on crops known as the "dîme

", cancelled special privileges for the clergy, and confiscated Church property: under the Ancien Régime, the Church had been the largest landowner in the country. Further legislation abolished monastic vows. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy

, passed on July 12, 1790, turned the remaining clergy into employees of the State and required that they take an oath of loyalty to the constitution. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy

also made the Catholic Church an arm of the secular state.

Looking to the United States Declaration of Independence

for a model, on August 26, 1789 the Assembly published the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

. Like the U.S. Declaration, it comprised a statement of principles rather than a constitution

with legal effect. The Assembly replaced the historic provinces

with eighty-three départements, uniformly administered and approximately equal to one another in extent and population; it also abolished the symbolic paraphernalia of the Ancien Régime — armorial bearings, liveries, etc. — which further alienated the more conservative nobles, and added to the ranks of the émigré

s.

Louis XVI opposed the course of the revolution and on the night of June 20, 1791 the royal family fled the Tuileries. However, the king was recognised at Varennes in the Meuse

late on June 21 and he and his family were brought back to Paris under guard. With most of the Assembly still favouring a constitutional monarchy

rather than a republic

, the various groupings reached a compromise which left Louis XVI little more than a figurehead: he had perforce to swear an oath to the constitution, and a decree declared that retracting the oath, heading an army for the purpose of making war upon the nation, or permitting anyone to do so in his name would amount to de facto abdication.

Meanwhile, a renewed threat from abroad arose: Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor

, Frederick William II of Prussia

, and the king's brother Charles-Phillipe, comte d'Artois

issued the Declaration of Pilnitz which considered the cause of Louis XVI as their own, demanded his total liberty and the dissolution of the Assembly, and promised an invasion of France on his behalf if the revolutionary authorities refused its conditions. The politics of the period inevitably drove France towards war with Austria and its allies. France declared war on Austria (April 20, 1792) and Prussia

joined on the Austrian side a few weeks later. The French Revolutionary Wars

had begun.

On August 10, 1792

in France the King Louis XVI

was arrested. After the first great victory of the French revolutionary troops at the battle of Valmy

on September 20, 1792 the First Republic

was proclaimed the day after on September 21. By the end of the year, the French had overrun the Austrian Netherlands, threatening the Dutch Republic to the north, and also penetrated east of the Rhine, briefly occupying the imperial city of Frankfurt am Main.

January 17, 1793 saw the king condemned to death for "conspiracy against the public liberty and the general safety" by a weak majority in Convention. On January 21, he was beheaded. This action led to Britain and the Netherlands declaring war on France.

The first half of 1793 went badly, with the French armies being driven out of Germany and the Austrian Netherlands. In this situation, prices rose and the sans-culottes

(poor labourers and radical Jacobins) rioted; counter-revolutionary activities began in some regions. This encouraged the Jacobins to seize power through a parliamentary coup

, backed up by force effected by mobilising public support against the Girondist faction, and by utilising the mob power of the Parisian sans-culottes. An alliance of Jacobin and sans-culottes elements thus became the effective centre of the new government. Policy became considerably more radical. The government instituted the "levy-en-masse", where all able-bodied men 18 and older were liable for military service. This allowed France to field much larger armies than its enemies, and soon the tide of war was reversed.

The Committee of Public Safety

came under the control of Maximilien Robespierre

, and the Jacobins unleashed the Reign of Terror

(1793–1794). At least 1200 people met their deaths under the guillotine

— or otherwise — after accusations of counter-revolutionary activities. In October, the queen was beheaded, further antagonizing Austria. In 1794 Robespierre had ultra-radicals and moderate Jacobins executed; in consequence, however, his own popular support eroded markedly. Georges Danton

was beheaded for arguing that there were too many beheadings. There were attempts to do away with organized religion in France entirely and replace it with a Festival of Reason. The primary leader of this movement, Jacques Hebert

, held such a festival in the Cathedral of Notre Dame, with an actress playing the Goddess of Reason. But Robespierre was unmoved by Hebert and had him and all his followers beheaded. On July 27, 1794 the French people revolted against the excesses of the Reign of Terror in what became known as the Thermidorian Reaction

. It resulted in moderate Convention members deposing Robespierre and several other leading members of the Committee of Public Safety. All of them were beheaded without trial. With that, the extreme, radical phase of the Revolution ended. The Convention approved the new "Constitution of the Year III" on August 17, 1795; a plebiscite ratified it in September; and it took effect on September 26, 1795.

The new constitution installed the Directoire

and created the first bicameral legislature in French history. It was markedly more conservative, dominated by the bourgeoise, and sought to restore order and exclude the sans-culottes and other members of the lower classes from political life. By 1795, the French had once again conquered the Austrian Netherlands and the left bank of the Rhine, annexing them directly into France. The Dutch Republic and Spain were both defeated and made into French satellites. At sea however, the French navy proved no match for the British, and was badly beaten off the coast of Ireland in June 1794.

In 1796, Napoleon Bonaparte was given command of an army that was to invade Italy. The Austrian and Sardinian forces were defeated by the young general, they capitulated, and he negotiated the Treaty of Campo Formio without the input of the Directory. The French annexation of the Austrian Netherlands and the left bank of the Rhine was recognized, as were the satellite republics they created in northern Italy. The War of the First Coalition came to an end.

Military campaigns continued in 1798, with invasions of Switzerland, Naples, and the Papal States taking place and republics being established in those countries. Napoleon also convinced the Directory to approve an expedition to Egypt, with the purpose of cutting off Britain's supply route to India. He got approval for this, and set off in May 1798 for Egypt with 40,000 men. But the expedition foundered when the British fleet of Horatio Nelson caught and destroyed most of the French ships in the Battle of the Nile

. The army was left with no way to get home, and now facing the hostility of the Ottoman Empire. Napoleon himself escaped back to France, where he led the coup de etat of November 1799, making himself First Consul (his hapless troops remained in Egypt until they surrendered to a British expedition in 1801 and were repatriated to France).

By that point, the War of the Second Coalition

was in progress. The French suffered a string of defeats in 1799, seeing their satellite republics in Italy overthrown and an invasion of Germany beaten back. Attempts by the allies on Switzerland and the Netherlands failed however, and once Napoleon returned to France, he began turning the tide on them. In 1801, the Peace of Lunéville ended hostilities with Austria and Russia, and the Treaty of Amiens with Britain.

(or the Napoleonic Empire) (1804–1814) was marked by the French domination and reorganization of continental Europe (the Napoleonic Wars

) and by the final codification of the republican legal system (the Napoleonic Code

). The Empire gradually became more authoritarian in nature, with freedom of the press and assembly being severely restricted. Religious freedom survived under the condition that Christianity and Judaism, the two officially recognized faiths, not be attacked, and that atheism not be expressed in public. Napoleon also recreated the nobility, but neither they nor his court had the elegance or historical connections of the old monarchy. Despite the growing administrative despotism of his regime, the emperor was still seen by the rest of Europe as the embodiment of the Revolution.

By 1804, Britain alone stood outside French control and was an important force in encouraging and financing resistance to France. In 1805, Napoleon massed an army of 200,000 men in Bolougne for the purpose of invading the British Isles, but never was able to find the right conditions to embark, and thus abandoned his plans. Three weeks later, the French and Spanish fleets were destroyed by the British at Trafalgar. Afterwards, Napoleon, unable to defeat Britain militarily, tried to bring it down through economic warfare. He inaugurated the Continental System, in which all of France's allies and satellites would join in refusing to trade with the British.

Portugal, an ally of Britain, was the only European country that openly refused to join. After the Treaties of Tilsit

of July 1807, the French launched an invasion through Spain to close this hole in the Continental System. British troops arrived in Portugal, compelling the French to withdraw. A renewed invasion the following year brought the British back, and at that point, Napoleon decided to depose the Spanish king Charles IV

and place his brother Joseph

on the throne. This caused the people of Spain to rise up in a patriotic revolt, beginning the Peninsular War

. The British could now gain a foothold on the Continent, and the war tied down considerable French resources, contributing to Napoleon's eventual defeat.

Napoleon was at the height of his power in 1810-1812, with most of the European countries either his allies, satellites, or annexed directly into France. After the defeat of Austria in the War of the Fifth Coalition

, Europe was at peace for 2-1/2 years except for the conflict in Spain. The emperor was given an archduchess to marry by the Austrians, and she gave birth to his long-awaited son in 1811.

Ultimately, the Continental System failed. Its effect on Great Britain and on British trade is uncertain, but the embargo is thought to have been more harmful on the continental European states. Russia in particular chafed under the embargo, and in 1812, that country reopened trade with Britain, provoking Napoleon's invasion of Russia. The disaster of that campaign caused all the subjugated peoples of Europe to rise up against French domination. In 1813, Napoleon was forced to conscript boys under the age of 18 and less able-bodied men who had been passed up for military service in previous years. The quality of his troops deteriorated sharply and war weariness at home increased. The allies could also put far more men in the field than he could. Throughout 1813, the French were forced back and by early 1814, the British were occupying Gascony. The allied troops reached Paris in March, and Napoleon abdicated as emperor. Louis XVIII, the brother of Louis XVI, was installed as king and France was granted a quite generous peace settlement, being restored to its 1792 boundaries and having to pay no war indemnity.

After eleven months of exile on the island of Elba

in the Mediterranean, Napoleon escaped and returned to France, where he was greeted with huge enthusiasm. Louis XVIII fled Paris, but the one thing that would have given the emperor mass support, a return to the revolutionary extremism of 1793-1794, was out of the question. Enthusiasm quickly waned, and as the allies (then discussing the fate of Europe in Vienna) refused to negotiate with him, he had no choice but to fight. At Waterloo

, Napoleon was completely defeated by the British and Prussians, and abdicated once again. This time, he was exiled to the island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, where he remained until his death from stomach cancer

in 1821.

, a more harsh peace treaty was imposed on France, returning it to its 1789 boundaries and requiring a war indemnity. Allied troops were to remain in the country until it was paid. There were large-scale purges of Bonapartists from the government and military, and a brief "White Terror" in the south of France claimed 300 victims.

Despite the return of the House of Bourbon to power, France was much changed from the era of the Ancien Régime. The egalitarianism and liberalism of the revolutionaries remained an important force and the autocracy and hierarchy of the earlier era could not be fully restored. The economic changes, which had been underway long before the revolution, had been further enhanced during the years of turmoil and were firmly entrenched by 1815. These changes had seen power shift from the noble landowners to the urban merchants. The administrative reforms of Napoleon, such as the Napoleonic Code

and efficient bureaucracy, also remained in place. These changes produced a unified central government that was fiscally sound and had much control over all areas of French life, a sharp difference from the situation the Bourbons had faced before the Revolution.

In 1823, France intervened in Spain, where a civil war had deposed its king Ferdinand VII. The British objected to this, as it brought back memories of the still recent Peninsular War. However, the French troops marched into Spain, retook Madrid from the rebels, and left almost as quickly as they came. Despite worries to the contrary, France showed no sign of returning to an aggressive foreign policy and was admitted to the Concert of Europe

in 1818.

Louis XVIII

, for the most part, accepted that much had changed. However, he was pushed on his right by the Ultra-royalists, led by the comte de Villèle, who condemned the Doctrinaires

' attempt to reconcile the Revolution with the monarchy through a constitutional monarchy

. Instead, the Chambre introuvable

elected in 1815 banished all Conventionnels

who had voted Louis XVI's death and passed several reactionary

laws. Louis XVIII was forced to dissolve this Chamber, dominated by the Ultras, in 1816, fearing a popular uprising. The liberals thus governed until the 1820 assassination of the duc de Berry

the nephew of the king and known supporter of the Ultras, which brought Villèle's ultras back to power (vote of the Anti-Sacrilege Act

in 1825, and of the loi sur le milliard des émigrés, Act on the émigrés' billions). Louis died in September 1824 and was succeeded by his brother.

Charles X of France

took a far more conservative line. He attempted to rule as an absolute monarch and reassert the power of the Catholic Church in France. Acts of sacrilege in churches became punishable by death, and freedom of the press was severely restricted. Finally, he tried to compensate the families of the nobles who had had their property destroyed during the Revolution. In 1830 the discontent caused by these changes and Charles X's authoritarian nomination of the Ultra prince de Polignac

as minister culminated in an uprising in the streets of Paris, known as the 1830 July Revolution

(or, in French, "Les trois Glorieuses" - The three Glorious days - of 27, 28 and July 29). Charles was forced to flee and Louis-Philippe d'Orléans, a member of the Orléans

branch of the family, and son of Philippe Égalité who had voted the death of his cousin Louis XVI, ascended the throne. Louis-Philippe ruled, not as "King of France" but as "King of the French" (an evocative difference for contemporaries). It was made clear that his right to rule came from the people and was not divinely granted. He also revived the Tricolor as the flag of France, in place of the white Bourbon flag that had been used since 1815, an important distinction because the Tricolour was the symbol of the revolution.

(1830–1848) is generally seen as a period during which the haute bourgeoisie

was dominant, and marked the shift from the counter-revolutionaries Legitimists to the Orleanist

s, who were willing to make some compromises with the changes brought by the 1789 Revolution

. Louis-Philippe was crowned "King of the French

," instead of "King of France": this marked his acceptance of popular sovereignty

, which replaced the Ancien Régime 's divine right

. Louis-Philippe clearly understood his base of power: the wealthy bourgeoisie had carried him aloft during the July Revolution

through their work in the Parliament, and throughout his reign, he kept their interests in mind.

Louis-Philippe, who had flirted with liberalism

in his youth, rejected much of the pomp and circumstance of the Bourbons

and surrounded himself with merchants and bankers. The July Monarchy, however, remained a time of turmoil. A large group of Legitimists on the right

demanded the restoration of the Bourbons to the throne. On the left, Republicanism

and, later Socialism

, remained a powerful force. Late in his reign Louis-Philippe became increasingly rigid and dogmatic and his President of the Council, François Guizot

, had become deeply unpopular, but Louis-Philippe refused to remove him. The situation gradually escalated until the Revolutions of 1848 saw the fall of the monarchy and the creation of the Second Republic.

However, during the first several years of his regime, Louis-Philippe appeared to move his government toward legitimate, broad-based reform. The government found its source of legitimacy within the Charter of 1830

, written by reform-minded members of Chamber of Deputies

upon a platform of religious equality, the empowerment of the citizenry through the reestablishment of the National Guard

, electoral reform, the reformation of the peerage system, and the lessening of royal authority. And indeed, Louis-Phillipe and his ministers adhered to policies that seemed to promote the central tenets of the constitution. However, the majority of these policies were veiled attempts to shore up the power and influence of the government and the bourgeoisie, rather than legitimate attempts to promote equality and empowerment for a broad constituency of the French population. Thus, though the July Monarchy seemed to move toward reform, this movement was largely illusory.

During the years of the July Monarchy, enfranchisement roughly doubled, from 94,000 under Charles X to more than 200,000 by 1848 . However, this represented only roughly one percent of population, and as the requirements for voting were tax-based, only the wealthiest gained the privilege. By implication, the enlarged enfranchisement tended to favor the wealthy merchant bourgeoisie more than any other group. Beyond simply increasing their presence within the Chamber of Deputies

, this electoral enlargement provided the bourgeoisie the means by which to challenge the nobility in legislative matters. Thus, while appearing to honor his pledge to increase suffrage, Louis-Philippe acted primarily to empower his supporters and increase his hold over the French Parliament. The inclusion of only the wealthiest also tended to undermine any possibility of the growth of a radical faction in Parliament, effectively serving socially conservative ends.

The reformed Charter of 1830 limited the power of the King – stripping him of his ability to propose and decree legislation, as well as limiting his executive authority. However, the King of the French still believed in a version of monarchy that held the king as much more than a figurehead for an elected Parliament, and as such, he was quite active in politics. One of the first acts of Louis-Philippe in constructing his cabinet was to appoint the rather conservative Casimir Perier

as the premier of that body. Perier, a banker, was instrumental in shutting down many of the Republican secret societies and labor unions that had formed during the early years of the regime. In addition, he oversaw the dismemberment of the National Guard after it proved too supportive of radical ideologies. He performed all of these actions, of course, with royal approval. He was once quoted as saying that the source of French misery was the belief that there had been a revolution. "No Monsieur," he said to another minister, "there has not been a revolution: there is simply a change at the head of state."

Further expressions of this conservative trend came under the supervision of Perier and the then Minister of the Interior, François Guizot

. The regime acknowledged early on that radicalism

and republicanism threatened it, undermining its laissez-faire policies. Thus, the Monarchy declared the very term republican illegal in 1834. Guizot shut down republican clubs and disbanded republican publications. Republicans within the cabinet, like the banker Dupont, were all but excluded by Perier and his conservative clique. Distrusting the sole National Guard, Louis-Philippe increased the size of the army

and reformed it in order to ensure its loyalty to the government.

Though two factions always persisted in the cabinet, split between liberal conservatives like Guizot (le parti de la Résistance, the Party of Resistance) and liberal reformers like the aforementioned journalist Adolphe Thiers

(le parti du Mouvement, the Party of Movement), the latter never gained prominence. After Perier came count Molé, another conservative. After Molé came Thiers, a reformer later sacked by Louis-Philippe after attempting to pursue an aggressive foreign policy. After Thiers came the conservative Guizot. In particular, the Guizot administration was marked by increasingly authoritarian crackdowns on republicanism and dissent, and an increasingly pro-business laissez-faire policy. This policy included protective tariff

s that defended the status quo and enriched French businessmen. Guizot's government granted railway and mining contracts to the bourgeois supporters of the government, and even contributing some of the start-up costs. As workers under these policies had no legal right to assemble, unionize, or petition the government for increased pay or decreased hours, the July Monarchy under Perier, Molé, and Guizot generally proved detrimental to the lower classes. In fact, Guizot's advice to those who were disenfranchised by the tax-based electoral requirements was a simple "enrichissez-vous" – enrich yourself. The king himself was not very popular either by the middle of the 1840s, and due to his appearance was widely referred to as the "crowned pear". There was a considerable hero-worship of Napoleon during this era, and in 1841 his body was taken from Saint Helena and given a magnificent reburial in France.

Louis-Philippe conducted a pacifistic foreign policy. Shortly after he assumed power in 1830, Belgium revolted against Dutch rule and proclaimed its independence. The king rejected the idea of intervention there or any military activities outside France's borders. The only exception to this was a war in Algeria

which had been started by Charles X a few weeks before his overthrow on the pretext of suppressing pirates in the Mediterranean. Louis-Philippe's government decided to continue the conquest of that country, which took over a decade. By 1848, Algeria had been declared an integral part of France.

and Prussia

, and in the Italian States of Milan

, Venice

, Turin

and Rome. Economic downturns and bad harvests during the 1840s contributed to growing discontent.

In February 1848, the French government banned the holding of the Campagne des banquets

, fundraising dinners by activists where critics of the regime would meet (as public demonstrations and strikes were forbidden). As a result, protests and riots broke out in the streets of Paris. An angry mob converged on the royal palace, after which the hapless king abdicated and fled to England. The Second Republic was then proclaimed.

The revolution in France had brought together classes of wildly different interests: the bourgeoisie desired electoral reforms (a democratic republic), socialist leaders (like Louis Blanc

, Pierre Joseph Proudhon

and the radical Auguste Blanqui) asked for a "right to work" and the creation of national workshops (a social welfare republic) and for France to liberate the oppressed peoples of Europe (Poles and Italians), while moderates (like the aristocrat Alphonse de Lamartine

) sought a middle ground. Tensions between groups escalated, and in June 1848, a working class insurrection in Paris cost the lives of 1500 workers and eliminated once and for all the dream of a social welfare constitution.

. Finally, in 1852 he had himself declared Emperor Napoléon III of the Second Empire

.

from 1852 to 1870. The regime was authoritarian in nature during its early years, curbing most freedom of the press and assembly. The era saw great industrialization, urbanization (including the massive rebuilding of Paris by Baron Haussmann

) and economic growth, but Napoleon III's foreign policies would be catastrophic.

In 1852, Napoleon declared that "L'Empire, c'est la paix" (The empire is peace), but it was hardly fitting for a Bonaparte to continue the foreign policy of Louis-Philippe. Only a few months after becoming president in 1848, he sent French troops to break up a short-lived republic in Rome, remaining there until 1870. The overseas empire expanded, and France made gains in Indo-China, West and central Africa, and the South Seas. This was helped by the opening of large central banks in Paris to finance overseas expeditions. The Suez Canal

was opened by the Empress Eugénie in 1869 and was the achievement of a Frenchman. Yet still, Napoleon III's France lagged behind Britain in colonial affairs, and his determination to upstage British control of India and American influence in Mexico resulted in a fiasco.

In 1854, the emperor allied with Britain and the Ottoman Empire against Russia in the Crimean War

. Afterwards, Napoleon intervened in the questions of Italian independence. He declared his intention of making Italy "free from the Alps

to the Adriatic", and fought a war

with Austria in 1859 over this matter. With the victories of Montebello

, Magenta

and Solferino

France and Austria signed the Peace of Villafranca

in 1859, as the emperor worried that a longer war might cause the other powers, particularly Prussia, to intervene. Austria ceded Lombardy

to Napoleon III, who in turn ceded it to Victor Emmanuel; Modena

and Tuscany

were restored to their respective dukes, and the Romagna

to the pope

, now president of an Italian federation. In exchange for France's military assistance against Austria, Piedmont ceded its provinces of Nice

and Savoy

to France in March 1860. Napoleon then turned his hand to meddling in the Western Hemisphere. He gave support to the Confederacy during the American Civil War

, until Abraham Lincoln

announced the Emancipation Proclamation

in the autumn of 1862. As this made it impossible to support the South without also supporting slavery, the emperor backed off. However, he was conducting a simultaneous venture in Mexico, which had refused to pay interest on loans taken from France, Britain, and Spain. As a result, those three countries sent a joint expedition to the city of Veracruz

in January 1862, but the British and Spanish quickly withdrew after realizing the extent of Napoleon's plans. French troops occupied Mexico City

in June 1863 and established a puppet government headed by the Austrian archduke Maximilian, who was declared Emperor of Mexico. Although this sort of thing was forbidden by the Monroe Doctrine

, Napoleon reasoned that the United States was far too distracted with the Civil War to do anything about it. The French were never able to suppress the forces of the ousted Mexican president Benito Juárez

, and then in the spring of 1865, the Civil War ended. The United States, which had an army of a million battle-hardened troops, demanded that the French withdraw or prepare for war. They quickly did so, but Maximilian tried to hold onto power. He was captured and shot by the Mexicans in 1867.

Public opinion was becoming a major force as people began to tire of oppressive authoritarianism in the 1860s. Napoleon III, who had expressed some rather woolly liberal ideas prior to his coronation, began to relax censorship, laws on public meetings, and the right to strike. As a result, radicalism grew among industrial workers. Discontent with the Second Empire spread rapidly, as the economy began to experience a downturn. The golden days of the 1850s were over. Napoleon's reckless foreign policy was inciting criticism. To placate the Liberals, in 1870 Napoleon proposed the establishment of a fully parliamentary legislative regime, which won massive support. The French emperor never had the chance to implement this, however - by the end of the year, the Second Empire had ignominiously collapsed.

Napoleon's distraction with Mexico prevented him from intervening in the Second Schleswig War in 1864 and the Seven Weeks War in 1866. Both of those conflicts saw Prussia establish itself as the dominant power in Germany. Afterwards, tensions between France and Prussia grew, especially in 1868 when the latter tried to place a Hohenzollern prince on the Spanish throne, which was left vacant by a revolution there.

The Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck

provoked Napoleon into declaring war on Prussia in July 1870. The French troops were swiftly defeated in the following weeks, and on September 1, the main army, which the emperor himself was with, was trapped at Sedan and forced to surrender. A republic was quickly proclaimed in Paris, but the war was far from over. As it was clear that Prussia would expect territorial concessions, the provisional government vowed to continue resistance. The Prussians laid siege to Paris, and new armies mustered by France failed to alter this situation. The French capital began experiencing severe food shortages, to the extent where even the animals in the zoo were eaten. As the city was being bombarded by Prussian siege guns in January 1871, King William of Prussia was proclaimed Emperor of Germany in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. Shortly afterwards, Paris surrendered. The subsequent peace treaty was harsh. France ceded Alsace and Lorraine to Germany and had to pay an indemnity of 5 billion francs. German troops were to remain in the country until it was paid off. Meanwhile, the fallen Napoleon III went into exile in England where he died in 1873.

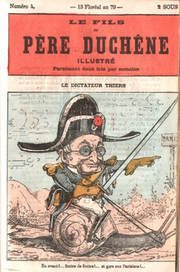

(which was violently repressed by Adolphe Thiers) — and two provinces (Alsace-Lorraine

) annexed to Germany. Feelings of national guilt and a desire for vengeance ("revanchism

") would be major preoccupations of the French throughout the next half century.

The Third Republic

The Third Republic

was established on September 4, 1870, following the defeat of Napoleon III during the 1870 war against Prussia

. However, the constitutional laws of the new republic were established only in February 1875, after the crushing of the revolutionary Paris Commune

by Adolphe Thiers.

The Commune started with the uprising of the Parisian population following the siege of Paris in September 1870, and was in place from March 18, 1871 to May 28, 1871. Adolphe Thiers angered the people of Paris by allowing the Prussians a parade in Paris on February 17, 1871, and on March 18 in an attempt to strengthen his government's position and decrease the power of the National Guard, he ordered the French regular troops to remove the cannon which had been moved to Montmartre

, a move opposed by the leadership of the National Guard. Many French soldiers agreed with the National Guard, refused to obey the order, and fell in with the Guard in the uprising. Seeing that he had lost control, Thiers ordered the regular forces, police, administrators and specialists to go to Versailles

and fled the city followed by all those that obeyed.

The Commune used the socialist

red flag

rather than the moderate republican

tricolore (during the Second Republic

in 1848, radicals supporting a socialist alternative government to the moderate republican Second Republic already raised a red flag). In only three months, the Commune voted many social measures, including:

Projected legislation also separated the Church from the state

, made all Church property state property, and excluded religion from schools. During the uprising, the churches were only allowed to continue their religious activity if they kept their doors open to public political meetings during the evenings. This made the churches, along with the streets and the cafés, the chief participatory political centres of the Commune. Other projected legislation dealt with educational reforms which would make further education and technical training freely available to all. The Vendôme Column, seen as a symbol of Napoleon's imperialism

and of chauvinism

, was taken down. Some women organized the first traces of a feminist movement

. Thus, Nathanie Le Mel, a religious workwoman, and Elisabeth Dmitrieff, a young Russian aristocrat, created the Union des femmes pour la défense de Paris et les soins aux blessés ("Women Union for the Defense of Paris and Care to the Injured") on April 11, 1871. Considering that their struggle against patriarchy

could only be followed in the frame of a global struggle against capitalism

, the association revendicated gender equality, wages' equality, right of divorce for women, right to laïque

instruction (non-clerical) and for professional formation for girls. They also demanded suppression of the distinction between married women and concubins, between legitimate and natural children, the abolition of prostitution

— they obtained the closing of the maisons de tolérance (legal unofficial brothel

s). The Women Union also participated in several municipal commissions and organized cooperative workshops.

Taking advantage of his retreat from Paris and of Baron Haussmann

's urban modeling of the capital

during the Second Empire — construction of wide boulevards

linking the train stations and therefore the soldiers coming from the countryside to the capital — Adolphe Thiers led the harsh repression of the Communards

. On May 27, 1871, when the last barricade

, in the rue Ramponeau in Belleville

, fell, Marshal MacMahon issued a proclamation: "To the inhabitants of Paris. The French army has come to save you. Paris is freed! At 4 o'clock our soldiers took the last insurgent position. Today the fight is over. Order, work and security will be reborn."

in the Père Lachaise cemetery, while thousands of others were marched to Versailles

for trials. The number killed during La Semaine Sanglante (The Bloody Week) can never be established for certain but the best estimates are 30,000 dead, many more wounded, and perhaps as many as 50,000 later executed or imprisoned; 7,000 were exiled to New Caledonia

. Thousands of them fled to Belgium, England, Italy, Spain and the United States. In 1872, "stringent laws were passed that ruled out all possibilities of organizing on the left." For the imprisoned there was a general amnesty in 1880. Paris remained under martial law for five years.

Beside this defeat, the Republican

movement also had to confront the counterrevolutionaries who rejected the legacy of the 1789 Revolution. Both the Legitimist and the Orleanist

royalists rejected republicanism, which they saw as an extension of modernity

and atheism

, breaking with France's traditions. This lasted until at least the May 16, 1877 crisis, which finally led to the resignation of royalist Marshal MacMahon in January 1879. The death of Henri, comte de Chambord

in 1883, who, as the grandson of Charles X, had refused to abandon the fleur-de-lys and the white flag

, thus jeopardizing the alliance between Legitimists and Orleanists, convinced many of the remaining Orleanists to rally themselves to the Republic, as Adolphe Thiers

had already done. The vast majority of the Legitimists abandoned the political arena or became marginalised, at least until Pétain

's Vichy regime. Some of them founded Action Française

in 1898, during the Dreyfus affair

, which became an influent movement through-out the 1930s, in particular among the intellectuals of Paris' Quartier Latin. In 1891, Pope Leo XIII

's encyclical Rerum Novarum

was incorrectly seen to have legitimised the Social Catholic

movement, which in France could be traced back to Hughes Felicité Robert de Lamennais

' efforts under the July Monarchy. Pope St Pius X later condemned these movements of Catholics for democracy and Socialism in Nostre Charge Apostolique against the Le Síllon movement.

") and bonapartists

scrambled for power. The period from 1879–1899 saw power come into the hands of moderate republicans and former "radicals" (around Léon Gambetta

); these were called the "Opportunists

" (Républicains opportunistes). The newly found Republican control on the Republic allowed the vote of the 1881 and 1882 Jules Ferry laws

on a free, mandatory and laic

public education

.

The moderates however became deeply divided over the Dreyfus affair

, and this allowed the Radicals to eventually gain power from 1899 until the Great War. During this period, crises like the potential "Boulangist" coup d'état (see Georges Boulanger

) in 1889, showed the fragility of the republic. The Radicals' policies on education (suppression of local languages, compulsory education), mandatory military service, and control of the working classes eliminated internal dissent and regionalisms, while their participation in the Scramble for Africa

and in the acquiring of overseas possessions (such as French Indochina

) created myths of French greatness. Both of these processes transformed a country of regionalisms into a modern nation state.

In 1880, Jules Guesde

and Paul Lafargue

, Marx

's son-in-law, created the French Workers' Party

(Parti ouvrier français, or POF), the first Marxist party in France. Two years later, Paul Brousse

's possibilistes split. A controversy arose in the French socialist movement and in the Second International

concerning "socialist participation in a bourgeois government", a theme which was triggered by independent socialist Alexandre Millerand

's participation to Radical-Socialist

Waldeck-Rousseau's cabinet at the turn of the century, which also included the marquis de Galliffet, best known for his role as repressor of the 1871 Commune. While Jules Guesde was opposed to this participation, which he saw as a trick, Jean Jaurès

defended it, making him one of the first social-democrat. Guesde's POF united itself in 1902 with the Parti socialiste de France, and finally in 1905 all socialist tendencies, including Jaurès' Parti socialiste français, unified into the Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière

(SFIO), the "French section of the Second International

", itself formed in 1889 after the split between anarcho-syndicalists

and Marxist socialists which led to the dissolving of the First International (founded in London in 1864).

In an effort to isolate Germany, France went to great pains to woo Russia and the United Kingdom to its side, first by means of the Franco-Russian Alliance

of 1894, then the 1904 Entente Cordiale

with the U.K, and finally, with the signing of the Anglo-Russian Entente

in 1907 this became the Triple Entente

, which eventually led Russia and the UK to enter World War I as Allies

.

Distrust of Germany, faith in the army and native French anti-semitism

combined to make the Dreyfus affair

(the unjust trial and condemnation of a Jewish military officer for treason) a political scandal of the utmost gravity. The nation was divided between "dreyfusards" and "anti-dreyfusards" and far-right Catholic agitators inflamed the situation even when proofs of Dreyfus' innocence came to light. The writer Émile Zola

published an impassioned editorial on the injustice, and was himself condemned by the government for libel. Once Dreyfus was finally pardoned, the progressive legislature enacted the 1905 laws on laïcité

which created a complete separation of church and state

and stripped churches of most of their property rights.

The period and the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century is often termed the belle époque

. Although associated with cultural innovations and popular amusements (cabaret, cancan, the cinema, new art forms such as Impressionism

and Art Nouveau

), France was nevertheless a nation divided internally on notions of religion, class, regionalisms and money, and on the international front France came repeatedly to the brink of war with the other imperial powers, including Great Britain (the Fashoda Incident

). The human and financial costs of World War I would be catastrophic for the French.

The long 19th century

The long nineteenth century, defined by Eric Hobsbawm , a British Marxist historian and author, refers to the period between the years 1789 and 1914...

) extends from the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

to World War I and includes:

- French RevolutionFrench RevolutionThe French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

(1789–1792) - French First RepublicFrench First RepublicThe French First Republic was founded on 22 September 1792, by the newly established National Convention. The First Republic lasted until the declaration of the First French Empire in 1804 under Napoleon I...

(1792–1804) - First French EmpireFirst French EmpireThe First French Empire , also known as the Greater French Empire or Napoleonic Empire, was the empire of Napoleon I of France...

under Napoleon (1804–1814) - Restoration under Louis XVIIILouis XVIII of FranceLouis XVIII , known as "the Unavoidable", was King of France and of Navarre from 1814 to 1824, omitting the Hundred Days in 1815...

and Charles XCharles X of FranceCharles X was known for most of his life as the Comte d'Artois before he reigned as King of France and of Navarre from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. A younger brother to Kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, he supported the latter in exile and eventually succeeded him...

(1814–1830) - July MonarchyJuly MonarchyThe July Monarchy , officially the Kingdom of France , was a period of liberal constitutional monarchy in France under King Louis-Philippe starting with the July Revolution of 1830 and ending with the Revolution of 1848...

under Louis Philippe d'Orléans (1830–1848) - Second RepublicFrench Second RepublicThe French Second Republic was the republican government of France between the 1848 Revolution and the coup by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte which initiated the Second Empire. It officially adopted the motto Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité...

(1848–1852) - Second Empire under Napoleon III (1852–1871)

- first decades of the Third RepublicFrench Third RepublicThe French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

(1871–1940)

Geography

At the time of the French Revolution, France had expanded to nearly her modern territorial limits. The nineteenth century would complete the process by the annexation of the Duchy of SavoySavoy

Savoy is a region of France. It comprises roughly the territory of the Western Alps situated between Lake Geneva in the north and Monaco and the Mediterranean coast in the south....

and the city of Nice

Nice

Nice is the fifth most populous city in France, after Paris, Marseille, Lyon and Toulouse, with a population of 348,721 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Nice extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of more than 955,000 on an area of...

(first during the First Empire, and then definitively in 1860) and some small papal (like Avignon

Avignon

Avignon is a French commune in southeastern France in the départment of the Vaucluse bordered by the left bank of the Rhône river. Of the 94,787 inhabitants of the city on 1 January 2010, 12 000 live in the ancient town centre surrounded by its medieval ramparts.Often referred to as the...

) and foreign possessions. France's territorial limits were greatly extended during the Empire through Napoléon Bonaparte's military conquests and re-organization of Europe, but these were reversed by the Vienna Congress. With the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the 1870 War was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the North German Confederation, of which it was a member, and the South German states of Baden, Württemberg and...

of 1870, France lost her provinces of Alsace

Alsace

Alsace is the fifth-smallest of the 27 regions of France in land area , and the smallest in metropolitan France. It is also the seventh-most densely populated region in France and third most densely populated region in metropolitan France, with ca. 220 inhabitants per km²...

and portions of Lorraine

Lorraine (province)

The Duchy of Upper Lorraine was an historical duchy roughly corresponding with the present-day northeastern Lorraine region of France, including parts of modern Luxembourg and Germany. The main cities were Metz, Verdun, and the historic capital Nancy....

to Germany (see Alsace-Lorraine

Alsace-Lorraine

The Imperial Territory of Alsace-Lorraine was a territory created by the German Empire in 1871 after it annexed most of Alsace and the Moselle region of Lorraine following its victory in the Franco-Prussian War. The Alsatian part lay in the Rhine Valley on the west bank of the Rhine River and east...

); these lost provinces would only be regained at the end of World War I.

In 1830, France invaded Algeria

Algeria

Algeria , officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria , also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa with Algiers as its capital.In terms of land area, it is the largest country in Africa and the Arab...

, and in 1848 this north African country was fully integrated into France as a département. The late nineteenth century saw France embark on a massive program of overseas imperialism — including French Indochina

French Indochina

French Indochina was part of the French colonial empire in southeast Asia. A federation of the three Vietnamese regions, Tonkin , Annam , and Cochinchina , as well as Cambodia, was formed in 1887....

(modern day Cambodia

Cambodia

Cambodia , officially known as the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia...

, Vietnam

Vietnam

Vietnam – sometimes spelled Viet Nam , officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam – is the easternmost country on the Indochina Peninsula in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by China to the north, Laos to the northwest, Cambodia to the southwest, and the South China Sea –...

and Laos

Laos

Laos Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ Sathalanalat Paxathipatai Paxaxon Lao, officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic, is a landlocked country in Southeast Asia, bordered by Burma and China to the northwest, Vietnam to the east, Cambodia to the south and Thailand to the west...

) and Africa (the Scramble for Africa

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also known as the Race for Africa or Partition of Africa was a process of invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period, between 1881 and World War I in 1914...

brought France most of North-West and Central Africa) — which brought it in direct competition with British interests.

Demographics

Between 1795 and 1866, metropolitan France (that is, without overseas or colonial possessions) was the second most populous country of Europe, behind Russia, and the fourth most populous country in the world (behind China, India, and Russia); between 1866 and 1911, metropolitan France was the third most populous country of Europe, behind Russia and Germany. Unlike other European countries, France did not experience a strong population growth from the middle of the 19th century to the first half of the 20th century. The French population in 1789 is estimated at roughly 28 million; by 1850, it was 36 million and in 1880 it was around 39 million.Until 1850, population growth was mainly in the countryside, but a period of massive urbanization

Urbanization

Urbanization, urbanisation or urban drift is the physical growth of urban areas as a result of global change. The United Nations projected that half of the world's population would live in urban areas at the end of 2008....

began under the Second Empire. Unlike in England, industrialization was a late phenomenon in France. The Napoleonic wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

had hindered early industrialization and France's economy in the 1830s (limited iron industry, under-developed coal supplies, a massive rural population) had not developed sufficiently to support an industrial expansion of any scope. French rail transport

History of rail transport in France

The history of rail transport in France dates from the first French railway in 1832 to present-day enterprises such as the AGV.-Beginnings:During the 19th century, railway construction began in France with short mineral lines...

only began hesitantly in the 1830s, and would not truly develop until the 1840s. By the revolution of 1848, a growing industrial workforce began to participate actively in French politics, but their hopes were largely betrayed by the policies of the Second Empire. The loss of the important coal, steel and glass production regions of Alsace and Lorraine would cause further problems. The industrial worker population increased from 23% in 1870 to 39% in 1914. Nevertheless, France remained a rather rural country in the early 1900s with 40% of the population still farmers in 1914. While exhibiting a similar urbanization rate as the U.S. (50% of the population in the U.S. was engaged in agriculture in the early 1900s), the urbanization rate of France was still well behind the one of the UK (80% urbanization rate in the early 1900s).

In the 19th century, France was a country of immigration for peoples and political refugees from Eastern Europe (Germany, Poland, Hungary, Russia, Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews, also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim , are the Jews descended from the medieval Jewish communities along the Rhine in Germany from Alsace in the south to the Rhineland in the north. Ashkenaz is the medieval Hebrew name for this region and thus for Germany...

) and from the Mediterranean (Italy, Spanish Sephardic Jews and North-African Mizrahi Jews

Mizrahi Jews

Mizrahi Jews or Mizrahiyim, , also referred to as Adot HaMizrach are Jews descended from the Jewish communities of the Middle East, North Africa and the Caucasus...

).

France was the first country in Europe to emancipate its Jewish population during the French Revolution. In 1872, there were an estimated 86,000 Jews living in France (by 1945 this would increase to 300,000), many of whom integrated (or attempted to integrate) into French society, although the Dreyfus affair

Dreyfus Affair

The Dreyfus affair was a political scandal that divided France in the 1890s and the early 1900s. It involved the conviction for treason in November 1894 of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a young French artillery officer of Alsatian Jewish descent...

would reveal anti-semitism in certain classes of French society (see History of the Jews in France

History of the Jews in France

The history of the Jews of France dates back over 2,000 years. In the early Middle Ages, France was a center of Jewish learning, but persecution increased as the Middle Ages wore on...

).

With the loss of Alsace and Lorraine, 5000 French refugees from these regions emigrated to Algeria

Algeria

Algeria , officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria , also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa with Algiers as its capital.In terms of land area, it is the largest country in Africa and the Arab...

in the 1870s and 1880s, as did too other Europeans (Spain, Malta) seeking opportunity. In 1889, non-French Europeans in Algeria were granted French citizenship (Arabs would however only win political rights in 1947).

Unlike other European countries, France did not experience a strong population growth in the mid and late 19th century and first half of the 20th century (see Demographics of France

Demographics of France

This article is about the demographic features of the population of France, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects....

). This would be compounded by the massive French losses of World War I — roughly estimated at 1.4 million French dead including civilians (see World War I casualties

World War I casualties

The total number of military and civilian casualties in World War I were over 35 million. There were over 15 million deaths and 20 million wounded ranking it among the deadliest conflicts in human history....

) (or nearly 10% of the active adult male population) and four times as many wounded (see World War I Aftermath).

Language

Linguistically, France was a patchwork. In 1792, perhaps 50% of the French population did not speak or understand French. The southern half of the country continued to speak one of the Occitan languages (such as ProvençalProvençal language

Provençal is a dialect of Occitan spoken by a minority of people in southern France, mostly in Provence. In the English-speaking world, "Provençal" is often used to refer to all dialects of Occitan, but it actually refers specifically to the dialect spoken in Provence."Provençal" is also the...

) and other inhabitants spoke Breton

Breton language

Breton is a Celtic language spoken in Brittany , France. Breton is a Brythonic language, descended from the Celtic British language brought from Great Britain to Armorica by migrating Britons during the Early Middle Ages. Like the other Brythonic languages, Welsh and Cornish, it is classified as...

, Catalan

Catalan language

Catalan is a Romance language, the national and only official language of Andorra and a co-official language in the Spanish autonomous communities of Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and Valencian Community, where it is known as Valencian , as well as in the city of Alghero, on the Italian island...

, Basque

Basque language

Basque is the ancestral language of the Basque people, who inhabit the Basque Country, a region spanning an area in northeastern Spain and southwestern France. It is spoken by 25.7% of Basques in all territories...

, Dutch

Dutch language

Dutch is a West Germanic language and the native language of the majority of the population of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Suriname, the three member states of the Dutch Language Union. Most speakers live in the European Union, where it is a first language for about 23 million and a second...

(West Flemish

West Flemish

West Flemish , , , Fransch vlaemsch in French Flemish) is a group of dialects or regional language related to Dutch spoken in parts of the Netherlands, Belgium, and France....

), Franco-provençal

Franco-Provençal language

Franco-Provençal , Arpitan, or Romand is a Romance language with several distinct dialects that form a linguistic sub-group separate from Langue d'Oïl and Langue d'Oc. The name Franco-Provençal was given to the language by G.I...

, Alsatian

Alsatian language

Alsatian is a Low Alemannic German dialect spoken in most of Alsace, a region in eastern France which has passed between French and German control many times.-Language family:...

and Corsican

Corsican language

Corsican is a Italo-Dalmatian Romance language spoken and written on the islands of Corsica and northern Sardinia . Corsican is the traditional native language of the Corsican people, and was long the vernacular language alongside the Italian, official language in Corsica until 1859, which was...

. In the north of France, regional dialects of the various langues d'oïl

Langues d'oïl

The langues d'oïl or langues d'oui , in English the Oïl or Oui languages, are a dialect continuum that includes standard French and its closest autochthonous relatives spoken today in the northern half of France, southern Belgium, and the Channel Islands...

continued to be spoken in rural communities. France would only become a linguistically unified country by the end of the 19th century, and in particular through the educational policies of Jules Ferry

Jules Ferry

Jules François Camille Ferry was a French statesman and republican. He was a promoter of laicism and colonial expansion.- Early life :Born in Saint-Dié, in the Vosges département, France, he studied law, and was called to the bar at Paris in 1854, but soon went into politics, contributing to...

during the French Third Republic

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

. From an illiteracy rate of 33% among peasants in 1870, by 1914 almost all French could read and understand the national language, although 50% continued to understand or speak a regional language of France (in today's France, only an estimated 10% still understand a regional language

Regional language

A regional language is a language spoken in an area of a nation state, whether it be a small area, a federal state or province, or some wider area....

).

Identity

Through the educational, social and military policies of the Third Republic, by 1914 the French had been converted (as the historian Eugen WeberEugen Weber

Eugen Joseph Weber was a Romanian-born American historian with a special focus on Western Civilization and the Western Tradition....

has put it) from a "country of peasants into a nation of Frenchmen".(Weber, E., 1979.) By 1914, most French could read French and regional languages had been greatly suppressed; the role of the Catholic Church in public life had been radically altered; a sense of national identity and glory was actively taught. The anti-clericalism of the Third Republic profoundly changed French religious habits: in one case study for the city of Limoges

Limoges

Limoges |Limousin]] dialect of Occitan) is a city and commune, the capital of the Haute-Vienne department and the administrative capital of the Limousin région in west-central France....

comparing the years 1899 with 1914, it was found that baptisms decreased from 98% to 60%, and civil marriages before a town official increased from 14% to 60%. Yet, the eradication of regionalisms and the anti-clerical nature of the Third Republic would create a backlash in the second half of the century.

French Revolution (1789–1792)

The reign of Louis XVILouis XVI of France

Louis XVI was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre until 1791, and then as King of the French from 1791 to 1792, before being executed in 1793....

(1774–1792) saw a temporary revival of French fortunes, but the over-ambitious projects and military campaigns of the 18th century had produced chronic financial problems. Deteriorating economic conditions, popular resentment against the complicated system of privileges granted the nobility and clerics, and a lack of alternate avenues for change were among the principal causes for convoking the Estates-General

French States-General

In France under the Old Regime, the States-General or Estates-General , was a legislative assembly of the different classes of French subjects. It had a separate assembly for each of the three estates, which were called and dismissed by the king...

which convened in Versailles

Versailles

Versailles , a city renowned for its château, the Palace of Versailles, was the de facto capital of the kingdom of France for over a century, from 1682 to 1789. It is now a wealthy suburb of Paris and remains an important administrative and judicial centre...

in 1789. On May 28, 1789 the Abbé Sieyès

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès , commonly known as Abbé Sieyès, was a French Roman Catholic abbé and clergyman, one of the chief theorists of the French Revolution, French Consulate, and First French Empire...

moved that the Third Estate proceed with verification of its own powers and invite the other two estates to take part, but not to wait for them. They proceeded to do so, and then voted a measure far more radical, declaring themselves the National Assembly

National Assembly (French Revolution)

During the French Revolution, the National Assembly , which existed from June 17 to July 9, 1789, was a transitional body between the Estates-General and the National Constituent Assembly.-Background:...

, an assembly not of the Estates but of "the People".

Louis XVI shut the Salle des États where the Assembly met. The Assembly moved their deliberations to the king's tennis court, where they proceeded to swear the Tennis Court Oath

Tennis Court Oath

The Tennis Court Oath was a pivotal event during the first days of the French Revolution. The Oath was a pledge signed by 576 of the 577 members from the Third Estate who were locked out of a meeting of the Estates-General on 20 June 1789...

(June 20, 1789), under which they agreed not to separate until they had given France a constitution

Constitution

A constitution is a set of fundamental principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization is governed. These rules together make up, i.e. constitute, what the entity is...

. A majority of the representatives of the clergy soon joined them, as did forty-seven members of the nobility. By June 27 the royal party had overtly given in, although the military began to arrive in large numbers around Paris and Versailles. On July 9 the Assembly reconstituted itself as the National Constituent Assembly

National Constituent Assembly

The National Constituent Assembly was formed from the National Assembly on 9 July 1789, during the first stages of the French Revolution. It dissolved on 30 September 1791 and was succeeded by the Legislative Assembly.-Background:...

.

On July 11, 1789 King Louis, acting under the influence of the conservative nobles, as well as his wife, Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette ; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was an Archduchess of Austria and the Queen of France and of Navarre. She was the fifteenth and penultimate child of Holy Roman Empress Maria Theresa and Holy Roman Emperor Francis I....

, and brother, the Comte d'Artois

Charles X of France

Charles X was known for most of his life as the Comte d'Artois before he reigned as King of France and of Navarre from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. A younger brother to Kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, he supported the latter in exile and eventually succeeded him...

, banished the reformist minister Necker

Jacques Necker

Jacques Necker was a French statesman of Swiss birth and finance minister of Louis XVI, a post he held in the lead-up to the French Revolution in 1789.-Early life:...

and completely reconstructed the ministry. Much of Paris, presuming this to be the start of a royal coup, moved into open rebellion. Some of the military joined the mob; others remained neutral. On July 14, 1789, after four hours of combat, the insurgents seized the Bastille

Bastille

The Bastille was a fortress in Paris, known formally as the Bastille Saint-Antoine. It played an important role in the internal conflicts of France and for most of its history was used as a state prison by the kings of France. The Bastille was built in response to the English threat to the city of...

fortress, killing the governor and several of his guards. The king and his military supporters backed down, at least for the time being. After this violence, nobles started to flee the country as émigré

Émigré

Émigré is a French term that literally refers to a person who has "migrated out", but often carries a connotation of politico-social self-exile....

s, some of whom began plotting civil war within the kingdom and agitating for a European coalition against France. Insurrection and the spirit of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty or the sovereignty of the people is the political principle that the legitimacy of the state is created and sustained by the will or consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. It is closely associated with Republicanism and the social contract...

spread throughout France. In rural areas, many went beyond this: some burned title-deeds and no small number of châteaux

Château

A château is a manor house or residence of the lord of the manor or a country house of nobility or gentry, with or without fortifications, originally—and still most frequently—in French-speaking regions...

, as part of a general agrarian insurrection known as "la Grande Peur" (the Great Fear).

On August 4, 1789, the National Assembly abolished feudalism

Feudalism

Feudalism was a set of legal and military customs in medieval Europe that flourished between the 9th and 15th centuries, which, broadly defined, was a system for ordering society around relationships derived from the holding of land in exchange for service or labour.Although derived from the...

, sweeping away both the seigneurial rights of the Second Estate and the tithe

Tithe

A tithe is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash, cheques, or stocks, whereas historically tithes were required and paid in kind, such as agricultural products...

s gathered by the First Estate. In the course of a few hours, nobles, clergy, towns, provinces, companies, and cities lost their special privileges. The revolution also brought about a massive shifting of powers from the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

to the State. Legislation enacted in 1790 abolished the Church's authority to levy a tax

Tax

To tax is to impose a financial charge or other levy upon a taxpayer by a state or the functional equivalent of a state such that failure to pay is punishable by law. Taxes are also imposed by many subnational entities...

on crops known as the "dîme

Tithe

A tithe is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash, cheques, or stocks, whereas historically tithes were required and paid in kind, such as agricultural products...

", cancelled special privileges for the clergy, and confiscated Church property: under the Ancien Régime, the Church had been the largest landowner in the country. Further legislation abolished monastic vows. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy