Maritime history

Encyclopedia

History

History is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians...

that often uses a global approach, although national and regional histories remain predominant. As an academic subject, it often crosses the boundaries of standard disciplines, focusing on understanding mankind's various relationships to the ocean

Ocean

An ocean is a major body of saline water, and a principal component of the hydrosphere. Approximately 71% of the Earth's surface is covered by ocean, a continuous body of water that is customarily divided into several principal oceans and smaller seas.More than half of this area is over 3,000...

s, sea

Sea

A sea generally refers to a large body of salt water, but the term is used in other contexts as well. Most commonly, it means a large expanse of saline water connected with an ocean, and is commonly used as a synonym for ocean...

s, and major waterway

Waterway

A waterway is any navigable body of water. Waterways can include rivers, lakes, seas, oceans, and canals. In order for a waterway to be navigable, it must meet several criteria:...

s of the globe. Nautical history records and interprets past events involving ships, shipping, navigation, and seamen.

Maritime history is the broad overarching subject that includes fishing

Fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch wild fish. Fish are normally caught in the wild. Techniques for catching fish include hand gathering, spearing, netting, angling and trapping....

, whaling

Whaling

Whaling is the hunting of whales mainly for meat and oil. Its earliest forms date to at least 3000 BC. Various coastal communities have long histories of sustenance whaling and harvesting beached whales...

, international maritime law, naval history

Naval history

Naval history is the area of military history concerning war at sea and the subject is also a sub-discipline of the broad field of maritime history....

, the history of ship

Ship

Since the end of the age of sail a ship has been any large buoyant marine vessel. Ships are generally distinguished from boats based on size and cargo or passenger capacity. Ships are used on lakes, seas, and rivers for a variety of activities, such as the transport of people or goods, fishing,...

s, ship design, shipbuilding

Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to before recorded history.Shipbuilding and ship repairs, both...

, the history of navigation

Navigation

Navigation is the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another. It is also the term of art used for the specialized knowledge used by navigators to perform navigation tasks...

, the history of the various maritime-related sciences (oceanography

Oceanography

Oceanography , also called oceanology or marine science, is the branch of Earth science that studies the ocean...

, cartography

Cartography

Cartography is the study and practice of making maps. Combining science, aesthetics, and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality can be modeled in ways that communicate spatial information effectively.The fundamental problems of traditional cartography are to:*Set the map's...

, hydrography

Hydrography

Hydrography is the measurement of the depths, the tides and currents of a body of water and establishment of the sea, river or lake bed topography and morphology. Normally and historically for the purpose of charting a body of water for the safe navigation of shipping...

, etc.), sea exploration, maritime economics and trade, shipping

Shipping

Shipping has multiple meanings. It can be a physical process of transporting commodities and merchandise goods and cargo, by land, air, and sea. It also can describe the movement of objects by ship.Land or "ground" shipping can be by train or by truck...

, yachting

Yachting

Yachting refers to recreational sailing or boating, the specific act of sailing or using other water vessels for sporting purposes.-Competitive sailing:...

, seaside resort

Seaside resort

A seaside resort is a resort, or resort town, located on the coast. Where a beach is the primary focus for tourists, it may be called a beach resort.- Overview :...

s, the history of lighthouse

Lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses or, in older times, from a fire, and used as an aid to navigation for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways....

s and aids to navigation, maritime themes in literature, maritime themes in art, the social history of sailor

Sailor

A sailor, mariner, or seaman is a person who navigates water-borne vessels or assists in their operation, maintenance, or service. The term can apply to professional mariners, military personnel, and recreational sailors as well as a plethora of other uses...

s and sea-related communities.

Ancient times

In ancient maritime historyAncient maritime history

Maritime history dates back thousands of years. In ancient maritime history, the first boats are presumed to have been dugout canoes which were developed independently by various stone age populations. In ancient history, various vessels were used for coastal fishing and travel.-Prehistory:The...

, the first boats are presumed to have been dugout canoes

Dugout (boat)

A dugout or dugout canoe is a boat made from a hollowed tree trunk. Other names for this type of boat are logboat and monoxylon. Monoxylon is Greek -- mono- + ξύλον xylon -- and is mostly used in classic Greek texts. In Germany they are called einbaum )...

, developed independently by various stone age populations, and used for coastal fishing and travel. The Indigenous of the Pacific Northwest

Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest is a region in northwestern North America, bounded by the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains on the east. Definitions of the region vary and there is no commonly agreed upon boundary, even among Pacific Northwesterners. A common concept of the...

are very skilled at crafting wood. Best known for totem poles up to 80 feet (24 m) tall, they also construct dugout canoes over 60 feet (18.3 m) long for everyday use and ceremonial purposes.

Prehistory of Australia

The prehistory of Australia is the period between the first human habitation of the Australian continent and the first definitive sighting of Australia by Europeans in 1606, which may be taken as the beginning of the recent history of Australia...

. In the history of whaling

History of whaling

The history of whaling is very extensive, stretching back for millennia. This article discusses the history of whaling up to the commencement of the International Whaling Commission moratorium on commercial whaling in 1986....

, humans began whaling in pre-historic times. The oldest known method of catching whales is to simply drive them ashore by placing a number of small boats between the whale and the open sea and attempting to frighten them with noise, activity, and perhaps small, non-lethal weapons such as arrows. Typically, this was used for small species, such as Pilot Whales, Belugas and Narwhals.

The earliest known reference to an organization devoted to ships in ancient India is to the Mauryan Empire from the 4th century BC. It is believed that the navigation as a science originated on the river Indus some 5000 years ago.

The Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

ians had knowledge to some extent of sail

Sail

A sail is any type of surface intended to move a vessel, vehicle or rotor by being placed in a wind—in essence a propulsion wing. Sails are used in sailing.-History of sails:...

construction. This is governed by the science

Science

Science is a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe...

of aerodynamics

Aerodynamics

Aerodynamics is a branch of dynamics concerned with studying the motion of air, particularly when it interacts with a moving object. Aerodynamics is a subfield of fluid dynamics and gas dynamics, with much theory shared between them. Aerodynamics is often used synonymously with gas dynamics, with...

. According to the Greek

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

historian Herodotus

Herodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

, Necho II

Necho II

Necho II was a king of the Twenty-sixth dynasty of Egypt .Necho II is most likely the pharaoh mentioned in several books of the Bible . The Book of Kings states that Necho met King Josiah of the Kingdom of Judah at Megiddo and killed him...

sent out an expedition of Phoenicians, which in three years sailed from the Red Sea

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. The connection to the ocean is in the south through the Bab el Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden. In the north, there is the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez...

around Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

to the mouth of the Nile

Nile

The Nile is a major north-flowing river in North Africa, generally regarded as the longest river in the world. It is long. It runs through the ten countries of Sudan, South Sudan, Burundi, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda and Egypt.The Nile has two major...

. Some current historians believe Herodotus on this point, even though Herodotus himself was in disbelief that the Phoenicians had accomplished the act.

Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

Theories of Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact are those theories that propose interaction between indigenous peoples of the Americas who settled the Americas before 10,000 BC, and peoples of other continents , which occurred before the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean in 1492.Many...

refers to hypothesised interactions between the Natives populations of the Americas and peoples of other continents before

Pre-Columbian

The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic period to European colonization during...

the arrival of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

in 1492. Many such events have been proposed at various times, based on historical reports, archaeological finds, and cultural comparisons.

Age of Navigation

In early modern IndiaIndia

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

and Arabia the lateen

Lateen

A lateen or latin-rig is a triangular sail set on a long yard mounted at an angle on the mast, and running in a fore-and-aft direction....

-sail ship known as the dhow

Dhow

Dhow is the generic name of a number of traditional sailing vessels with one or more masts with lateen sails used in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean region. Some historians believe the dhow was invented by Arabs but this is disputed by some others. Dhows typically weigh 300 to 500 tons, and have a...

was used on the waters of the Red Sea

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. The connection to the ocean is in the south through the Bab el Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden. In the north, there is the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez...

, Indian Ocean, and Persian Gulf

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, in Southwest Asia, is an extension of the Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.The Persian Gulf was the focus of the 1980–1988 Iran-Iraq War, in which each side attacked the other's oil tankers...

. There were also Southeast Asian Seafarers

Seafarers

Seafarers can refer to ethnic groups living by the sea in Southeast Asia, and also other sea-living ethnic groups in the world. The ethnic group name refers to a large distribution area, reaching from the islands of Indonesia to Burma...

and Polynesians

Polynesian culture

Polynesian culture refers to the indigenous peoples' culture of Polynesia who share common traits in language, customs and society. Chronologically, the development of Polynesian culture can be divided into four different historical eras:...

, and the Northern European Vikings, developed oceangoing vessels and depended heavily upon them for travel and population movements prior to 1000 AD. China's ships in the medieval period were particularly massive; multi-mast sailing junks

Junk (ship)

A junk is an ancient Chinese sailing vessel design still in use today. Junks were developed during the Han Dynasty and were used as sea-going vessels as early as the 2nd century AD. They evolved in the later dynasties, and were used throughout Asia for extensive ocean voyages...

were carrying over 200 people as early as 200 AD. The Astrolabe

Astrolabe

An astrolabe is an elaborate inclinometer, historically used by astronomers, navigators, and astrologers. Its many uses include locating and predicting the positions of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars, determining local time given local latitude and longitude, surveying, triangulation, and to...

was the chief tool of Celestial navigation

Celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is a position fixing technique that has evolved over several thousand years to help sailors cross oceans without having to rely on estimated calculations, or dead reckoning, to know their position...

in early maritime history. It was invented in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

and developed by Islamic astronomers

Islamic astronomy

Islamic astronomy or Arabic astronomy comprises the astronomical developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age , and mostly written in the Arabic language. These developments mostly took place in the Middle East, Central Asia, Al-Andalus, and North Africa, and...

. In ancient China, the engineer Ma Jun

Ma Jun

Ma Jun , style name Deheng , was a Chinese mechanical engineer and government official during the Three Kingdoms era of China...

(c. 200-265 AD) invented the South Pointing Chariot

South Pointing Chariot

The south-pointing chariot was an ancient Chinese two-wheeled vehicle that carried a movable pointer to indicate the south, no matter how the chariot turned. Usually, the pointer took the form of a doll or figure with an outstretched arm...

, a wheeled device employing a differential gear that allowed a fixed figurine

Figurine

A figurine is a statuette that represents a human, deity or animal. Figurines may be realistic or iconic, depending on the skill and intention of the creator. The earliest were made of stone or clay...

to always point in the southern cardinal direction

Cardinal direction

The four cardinal directions or cardinal points are the directions of north, east, south, and west, commonly denoted by their initials: N, E, S, W. East and west are at right angles to north and south, with east being in the direction of rotation and west being directly opposite. Intermediate...

.

The magnetic needle compass

Compass

A compass is a navigational instrument that shows directions in a frame of reference that is stationary relative to the surface of the earth. The frame of reference defines the four cardinal directions – north, south, east, and west. Intermediate directions are also defined...

for navigation

Navigation

Navigation is the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another. It is also the term of art used for the specialized knowledge used by navigators to perform navigation tasks...

was not written of until the Dream Pool Essays

Dream Pool Essays

The Dream Pool Essays was an extensive book written by the polymath Chinese scientist and statesman Shen Kuo by 1088 AD, during the Song Dynasty of China...

of 1088 AD by the author Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo or Shen Gua , style name Cunzhong and pseudonym Mengqi Weng , was a polymathic Chinese scientist and statesman of the Song Dynasty...

(1031–1095), who was also the first to discover the concept of true north

True north

True north is the direction along the earth's surface towards the geographic North Pole.True geodetic north usually differs from magnetic north , and from grid north...

(to discern against a compass' magnetic declination towards the North Pole

North Pole

The North Pole, also known as the Geographic North Pole or Terrestrial North Pole, is, subject to the caveats explained below, defined as the point in the northern hemisphere where the Earth's axis of rotation meets its surface...

). By at least 1117 AD, the Chinese used a magnetic needle that was submersed in a bowl of water, and would point in the southern cardinal direction. The first use of a magnetized needle for seafaring navigation in Europe was written of by Alexander Neckham, circa 1190 AD. Around 1300 AD, the pivot-needle dry-box compass was invented in Europe, its cardinal direction pointed north, similar to the modern-day mariners compass. There was also the addition of the compass-card in Europe, which was later adopted by the Chinese through contact with Japanese pirates

Wokou

Wokou , which literally translates as "Japanese pirates" in English, were pirates of varying origins who raided the coastlines of China and Korea from the 13th century onwards...

in the 16th century.

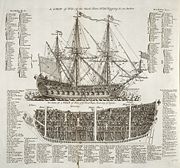

Ships and vessels

Various ships were in use during the Middle AgesMiddle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

. The longship

Longship

Longships were sea vessels made and used by the Vikings from the Nordic countries for trade, commerce, exploration, and warfare during the Viking Age. The longship’s design evolved over many years, beginning in the Stone Age with the invention of the umiak and continuing up to the 9th century with...

was a type of ship that was developed over a period of centuries and perfected by its most famous user, the Vikings, in approximately the 9th century. The ships were clinker-built, utilizing overlapping wooden strakes. The knaar

Knaar

A knarr is a type of Norse merchant ship famously used by the Vikings. Knarr is of the same clinker-built method used to construct longships, karves, and faerings.-History:...

, a relative of the longship, was a type of cargo vessel. It differed from the longship in that it was larger and relied solely on its square rigged sail for propulsion. The cog

Cog (ship)

A cog is a type of ship that first appeared in the 10th century, and was widely used from around the 12th century on. Cogs were generally built of oak, which was an abundant timber in the Baltic region of Prussia. This vessel was fitted with a single mast and a square-rigged single sail...

was a design which is believed to have evolved from (or at least been influenced by) the longship, and was in wide use by the 12th century. It too used the clinker method of construction. The caravel

Caravel

A caravel is a small, highly maneuverable sailing ship developed in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave her speed and the capacity for sailing to windward...

was a ship invented in Islamic Iberia

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

and used in the Mediterranean from the 13th century. Unlike the longship

Longship

Longships were sea vessels made and used by the Vikings from the Nordic countries for trade, commerce, exploration, and warfare during the Viking Age. The longship’s design evolved over many years, beginning in the Stone Age with the invention of the umiak and continuing up to the 9th century with...

and cog

Cog (ship)

A cog is a type of ship that first appeared in the 10th century, and was widely used from around the 12th century on. Cogs were generally built of oak, which was an abundant timber in the Baltic region of Prussia. This vessel was fitted with a single mast and a square-rigged single sail...

, it used a carvel

Carvel (boat building)

In boat building, carvel built or carvel planking is a method of constructing wooden boats and tall ships by fixing planks to a frame so that the planks butt up against each other, edge to edge, gaining support from the frame and forming a smooth hull...

method of construction. It could be either square rigged (Caravela Redonda) or lateen rigged (Caravela Latina). The carrack

Carrack

A carrack or nau was a three- or four-masted sailing ship developed in 15th century Western Europe for use in the Atlantic Ocean. It had a high rounded stern with large aftcastle, forecastle and bowsprit at the stem. It was first used by the Portuguese , and later by the Spanish, to explore and...

was another type of ship invented in the Mediterranean in the 15th century. It was a larger vessel than the caravel. Columbus’s ship, the Santa María

Santa María (ship)

La Santa María de la Inmaculada Concepción , was the largest of the three ships used by Christopher Columbus in his first voyage. Her master and owner was Juan de la Cosa.-History:...

was a famous example of a carrack.

Arab age of discovery

The Arab EmpireCaliphate

The term caliphate, "dominion of a caliph " , refers to the first system of government established in Islam and represented the political unity of the Muslim Ummah...

maintained and expanded a wide trade network across parts of Asia

Asia

Asia is the world's largest and most populous continent, located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres. It covers 8.7% of the Earth's total surface area and with approximately 3.879 billion people, it hosts 60% of the world's current human population...

, Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

and Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

. This helped establish the Arab Empire (including the Rashidun

Rashidun Empire

The Rashidun Caliphate , comprising the first four caliphs in Islam's history, was founded after Muhammad's death in 632, Year 10 A.H.. At its height, the Caliphate extended from the Arabian Peninsula, to the Levant, Caucasus and North Africa in the west, to the Iranian highlands and Central Asia...

, Umayyad

Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate was the second of the four major Arab caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. It was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty, whose name derives from Umayya ibn Abd Shams, the great-grandfather of the first Umayyad caliph. Although the Umayyad family originally came from the...

, Abbasid

Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate or, more simply, the Abbasids , was the third of the Islamic caliphates. It was ruled by the Abbasid dynasty of caliphs, who built their capital in Baghdad after overthrowing the Umayyad caliphate from all but the al-Andalus region....

and Fatimid caliphates) as the world's leading extensive economic power throughout the 7th-13th centuries.

Apart from the Nile

Nile

The Nile is a major north-flowing river in North Africa, generally regarded as the longest river in the world. It is long. It runs through the ten countries of Sudan, South Sudan, Burundi, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania, Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda and Egypt.The Nile has two major...

, Tigris

Tigris

The Tigris River is the eastern member of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of southeastern Turkey through Iraq.-Geography:...

and Euphrates

Euphrates

The Euphrates is the longest and one of the most historically important rivers of Western Asia. Together with the Tigris, it is one of the two defining rivers of Mesopotamia...

, navigable rivers in the Islamic regions were uncommon, so transport by sea was very important. Islamic geography

Islamic geography

Geography and cartography in medieval Islam refers to the advancement of geography, cartography and the earth sciences in the medieval Islamic civilization....

and navigational sciences were highly developed, making use of a magnetic compass

Compass

A compass is a navigational instrument that shows directions in a frame of reference that is stationary relative to the surface of the earth. The frame of reference defines the four cardinal directions – north, south, east, and west. Intermediate directions are also defined...

and a rudimentary instrument known as a kamal, used for celestial navigation

Celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is a position fixing technique that has evolved over several thousand years to help sailors cross oceans without having to rely on estimated calculations, or dead reckoning, to know their position...

and for measuring the altitude

Altitude

Altitude or height is defined based on the context in which it is used . As a general definition, altitude is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or "up" direction, between a reference datum and a point or object. The reference datum also often varies according to the context...

s and latitude

Latitude

In geography, the latitude of a location on the Earth is the angular distance of that location south or north of the Equator. The latitude is an angle, and is usually measured in degrees . The equator has a latitude of 0°, the North pole has a latitude of 90° north , and the South pole has a...

s of the star

Star

A star is a massive, luminous sphere of plasma held together by gravity. At the end of its lifetime, a star can also contain a proportion of degenerate matter. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun, which is the source of most of the energy on Earth...

s. When combined with detailed maps of the period, sailors were able to sail across ocean

Ocean

An ocean is a major body of saline water, and a principal component of the hydrosphere. Approximately 71% of the Earth's surface is covered by ocean, a continuous body of water that is customarily divided into several principal oceans and smaller seas.More than half of this area is over 3,000...

s rather than skirt along the coast. According to the political scientist Hobson, the origins of the caravel

Caravel

A caravel is a small, highly maneuverable sailing ship developed in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave her speed and the capacity for sailing to windward...

ship, used for long-distance travel by the Spanish and Portuguese since the 15th century, date back to the qarib used by Andalusian

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

explorers by the 13th century.

Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic LeagueHanseatic League

The Hanseatic League was an economic alliance of trading cities and their merchant guilds that dominated trade along the coast of Northern Europe...

was an alliance of trading guilds that established and maintained a trade monopoly over the Baltic Sea, to a certain extent the North Sea, and most of Northern Europe for a time in the Late Middle Ages and the early modern period, between the 13th and 17th centuries. Historians generally trace the origins of the League to the foundation of the Northern German town of Lübeck

Lübeck

The Hanseatic City of Lübeck is the second-largest city in Schleswig-Holstein, in northern Germany, and one of the major ports of Germany. It was for several centuries the "capital" of the Hanseatic League and, because of its Brick Gothic architectural heritage, is listed by UNESCO as a World...

, established in 1158/1159 after the capture of the area from the Count of Schauenburg and Holstein by Henry the Lion

Henry the Lion

Henry the Lion was a member of the Welf dynasty and Duke of Saxony, as Henry III, from 1142, and Duke of Bavaria, as Henry XII, from 1156, which duchies he held until 1180....

, the Duke of Saxony

Duchy of Saxony

The medieval Duchy of Saxony was a late Early Middle Ages "Carolingian stem duchy" covering the greater part of Northern Germany. It covered the area of the modern German states of Bremen, Hamburg, Lower Saxony, North Rhine-Westphalia, and Saxony-Anhalt and most of Schleswig-Holstein...

. Exploratory trading adventures, raid

Raid (military)

Raid, also known as depredation, is a military tactic or operational warfare mission which has a specific purpose and is not normally intended to capture and hold terrain, but instead finish with the raiding force quickly retreating to a previous defended position prior to the enemy forces being...

s and piracy

Piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence at sea. The term can include acts committed on land, in the air, or in other major bodies of water or on a shore. It does not normally include crimes committed against persons traveling on the same vessel as the perpetrator...

had occurred earlier throughout the Baltic (see Viking

Viking

The term Viking is customarily used to refer to the Norse explorers, warriors, merchants, and pirates who raided, traded, explored and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th century.These Norsemen used their famed longships to...

s) — the sailor

Sailor

A sailor, mariner, or seaman is a person who navigates water-borne vessels or assists in their operation, maintenance, or service. The term can apply to professional mariners, military personnel, and recreational sailors as well as a plethora of other uses...

s of Gotland

Gotland

Gotland is a county, province, municipality and diocese of Sweden; it is Sweden's largest island and the largest island in the Baltic Sea. At 3,140 square kilometers in area, the region makes up less than one percent of Sweden's total land area...

sailed up rivers as far away as Novgorod, for example — but the scale of international economy

Economic system

An economic system is the combination of the various agencies, entities that provide the economic structure that defines the social community. These agencies are joined by lines of trade and exchange along which goods, money etc. are continuously flowing. An example of such a system for a closed...

in the Baltic area remained insignificant before the growth of the Hanseatic League. German cities achieved domination of trade in the Baltic with striking speed over the next century, and Lübeck became a central node in all the seaborne trade that linked the areas around the North Sea

North Sea

In the southwest, beyond the Straits of Dover, the North Sea becomes the English Channel connecting to the Atlantic Ocean. In the east, it connects to the Baltic Sea via the Skagerrak and Kattegat, narrow straits that separate Denmark from Norway and Sweden respectively...

and the Baltic Sea.

The 15th century saw the climax of Lübeck's hegemony. (Visby

Visby

-See also:* Battle of Visby* Gotland University College* List of governors of Gotland County-External links:* - Visby*...

, one of the midwives of the Hanseatic league in 1358, declined to become a member. Visby dominated trade in the Baltic before the Hanseatic league, and with its monopolistic ideology, suppressed the Gotland

Gotland

Gotland is a county, province, municipality and diocese of Sweden; it is Sweden's largest island and the largest island in the Baltic Sea. At 3,140 square kilometers in area, the region makes up less than one percent of Sweden's total land area...

ic free-trade competition.) By the late 16th century, the League imploded and could no longer deal with its own internal struggles, the social and political changes that accompanied the Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

, the rise of Dutch and English merchants, and the incursion of the Ottoman Turks

Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks were the Turkish-speaking population of the Ottoman Empire who formed the base of the state's military and ruling classes. Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks is scarce, but they take their Turkish name, Osmanlı , from the house of Osman I The Ottoman...

upon its trade routes and upon the Holy Roman Empire itself. Only nine members attended the last formal meeting in 1669 and only three (Lübeck, Hamburg and Bremen) remained as members until its final demise in 1862.

Somali maritime enterprise

During the Age of the AjuuraanAjuuraan State

The Ajuuraan state or Ajuuraan sultanate was a Somali Muslim empire that ruled over large parts of East Africa in the Middle Ages. Through a strong centralized administration and an aggressive military stance towards invaders, the Ajuuraan Empire successfully resisted an Oromo invasion from the...

, the Somali sultanates and republics of Merca

Merca

Merca is a port city on the coast of southern Somalia, facing the Indian Ocean. It is the main town in the Shabeellaha Hoose region, and is located approximately southwest of the nation's capital, Mogadishu.-History:...

, Mogadishu

Mogadishu

Mogadishu , popularly known as Xamar, is the largest city in Somalia and the nation's capital. Located in the coastal Benadir region on the Indian Ocean, the city has served as an important port for centuries....

, Barawa

Barawa

Barawa or Brava is a port town on the south-eastern coast of Somalia. The traditional inhabitants are the Tunni Somalis and the Bravanese people, who speak Bravanese, a Swahili dialect.-History:...

, Hobyo

Hobyo

Hobyo is an ancient harbor city in the Mudug region of Somalia. Hobyo literally means "here, water", and the plentiful fresh water to be had from the wells in and around the town has been the driving force behind Hobyo's ancient status as a favorite port-of-call for sailors.-Establishment:Hobyo's...

and their respective ports flourished. They had a lucrative foreign commerce with ships sailing to and coming from Arabia, India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

, Venetia, Persia, Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

and as far away as China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

. In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa

Duarte Barbosa

Duarte Barbosa was a Portuguese writer and Portuguese India officer between 1500 and 1516–17, with the post of scrivener in Cannanore factory and sometimes interpreter of the local language...

noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya

Khambhat

Khambhat , formerly known as Cambay, is a city and a municipality in Anand district in the Indian state of Gujarat. It was formerly an important trading center, although its harbour has gradually silted up, and the maritime trade has moved elsewhere...

in what is modern-day India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

sailed to Mogadishu with cloths and spices, for which they in return received gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

, wax

Wax

thumb|right|[[Cetyl palmitate]], a typical wax ester.Wax refers to a class of chemical compounds that are plastic near ambient temperatures. Characteristically, they melt above 45 °C to give a low viscosity liquid. Waxes are insoluble in water but soluble in organic, nonpolar solvents...

and ivory

Ivory

Ivory is a term for dentine, which constitutes the bulk of the teeth and tusks of animals, when used as a material for art or manufacturing. Ivory has been important since ancient times for making a range of items, from ivory carvings to false teeth, fans, dominoes, joint tubes, piano keys and...

. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat

Meat

Meat is animal flesh that is used as food. Most often, this means the skeletal muscle and associated fat and other tissues, but it may also describe other edible tissues such as organs and offal...

, wheat

Wheat

Wheat is a cereal grain, originally from the Levant region of the Near East, but now cultivated worldwide. In 2007 world production of wheat was 607 million tons, making it the third most-produced cereal after maize and rice...

, barley

Barley

Barley is a major cereal grain, a member of the grass family. It serves as a major animal fodder, as a base malt for beer and certain distilled beverages, and as a component of various health foods...

, horses, and fruit

Fruit

In broad terms, a fruit is a structure of a plant that contains its seeds.The term has different meanings dependent on context. In non-technical usage, such as food preparation, fruit normally means the fleshy seed-associated structures of certain plants that are sweet and edible in the raw state,...

on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.

In the early modern period, successor states of the Adal

Adal Sultanate

The Adal Sultanate or the Kingdom of Adal was a medieval multi-ethnic Muslim state located in the Horn of Africa.-Overview:...

and Ajuuraan

Ajuuraan State

The Ajuuraan state or Ajuuraan sultanate was a Somali Muslim empire that ruled over large parts of East Africa in the Middle Ages. Through a strong centralized administration and an aggressive military stance towards invaders, the Ajuuraan Empire successfully resisted an Oromo invasion from the...

empire

Empire

The term empire derives from the Latin imperium . Politically, an empire is a geographically extensive group of states and peoples united and ruled either by a monarch or an oligarchy....

s began to flourish in Somalia who continued the seaborne trade established by previous Somali empires. The rise of the 19th century Gobroon Dynasty

Gobroon Dynasty

The Gobroon dynasty or Geledi sultanate was a Somali royal house that ruled parts of East Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries. It was established by the Ajuuraan soldier Ibrahim Adeer, who had defeated various vassals of the Ajuuraan Empire and established the House of Gobroon...

in particular saw a rebirth in Somali maritime enterprise. During this period, the Somali agricultural output to Arabian markets was so great that the coast of Somalia came to be known as the Grain Coast of Yemen

Yemen

The Republic of Yemen , commonly known as Yemen , is a country located in the Middle East, occupying the southwestern to southern end of the Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to the north, the Red Sea to the west, and Oman to the east....

and Oman

Oman

Oman , officially called the Sultanate of Oman , is an Arab state in southwest Asia on the southeast coast of the Arabian Peninsula. It is bordered by the United Arab Emirates to the northwest, Saudi Arabia to the west, and Yemen to the southwest. The coast is formed by the Arabian Sea on the...

.

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery was a period from the early 15th century and continuing into the early 17th century, during which EuropeEurope

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

an ships traveled around the world to search for new trading routes and partners to feed burgeoning capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

in Europe. They also were in search of trading goods such as gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

, silver

Silver

Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal...

, and spices. In the process, Europeans encountered peoples and mapped lands previously unknown to them.

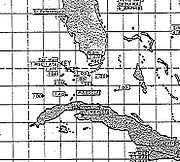

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

was a navigator

Navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation. The navigator's primary responsibility is to be aware of ship or aircraft position at all times. Responsibilities include planning the journey, advising the Captain or aircraft Commander of estimated timing to...

and maritime explorer who is one of several historical figures credited as the discoverer of the Americas

Discoverer of the Americas

The discovery of the Americas in modern western history is mainly attributed to the voyages of Christopher Columbus. The discovery of the Americas has also variously been attributed to others, depending on context and definition....

. It is generally believed that he was born in Genoa

Genoa

Genoa |Ligurian]] Zena ; Latin and, archaically, English Genua) is a city and an important seaport in northern Italy, the capital of the Province of Genoa and of the region of Liguria....

, although other theories and possibilities exist. Columbus' voyages across the Atlantic Ocean

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

began a Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

an effort at exploration

Exploration

Exploration is the act of searching or traveling around a terrain for the purpose of discovery of resources or information. Exploration occurs in all non-sessile animal species, including humans...

and colonization

European colonization of the Americas

The start of the European colonization of the Americas is typically dated to 1492. The first Europeans to reach the Americas were the Vikings during the 11th century, who established several colonies in Greenland and one short-lived settlement in present day Newfoundland...

of the Western Hemisphere

Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere or western hemisphere is mainly used as a geographical term for the half of the Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian and east of the Antimeridian , the other half being called the Eastern Hemisphere.In this sense, the western hemisphere consists of the western portions...

. While history places great significance on his first voyage of 1492, he did not actually reach the mainland

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

until his third voyage in 1498. Likewise, he was not the earliest European explorer to reach the Americas, as there are accounts of European transatlantic contact

Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

Theories of Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact are those theories that propose interaction between indigenous peoples of the Americas who settled the Americas before 10,000 BC, and peoples of other continents , which occurred before the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean in 1492.Many...

prior to 1492. Nevertheless, Columbus's voyage came at a critical time of growing national imperialism

Imperialism

Imperialism, as defined by Dictionary of Human Geography, is "the creation and/or maintenance of an unequal economic, cultural, and territorial relationships, usually between states and often in the form of an empire, based on domination and subordination." The imperialism of the last 500 years,...

and economic competition

Competition

Competition is a contest between individuals, groups, animals, etc. for territory, a niche, or a location of resources. It arises whenever two and only two strive for a goal which cannot be shared. Competition occurs naturally between living organisms which co-exist in the same environment. For...

between developing nation states

History of Europe

History of Europe describes the history of humans inhabiting the European continent since it was first populated in prehistoric times to present, with the first human settlement between 45,000 and 25,000 BC.-Overview:...

seeking wealth from the establishment of trade route

Trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a single trade route contains long distance arteries which may further be connected to several smaller networks of commercial...

s and colonies

Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment, maintenance, acquisition and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is a process whereby the metropole claims sovereignty over the colony and the social structure, government, and economics of the colony are changed by...

. Therefore, the period before 1492 is known as Pre-Columbian

Pre-Columbian

The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic period to European colonization during...

.

John Cabot

John Cabot

John Cabot was an Italian navigator and explorer whose 1497 discovery of parts of North America is commonly held to have been the first European encounter with the continent of North America since the Norse Vikings in the eleventh century...

was a Genoese

Genoa

Genoa |Ligurian]] Zena ; Latin and, archaically, English Genua) is a city and an important seaport in northern Italy, the capital of the Province of Genoa and of the region of Liguria....

navigator

Navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation. The navigator's primary responsibility is to be aware of ship or aircraft position at all times. Responsibilities include planning the journey, advising the Captain or aircraft Commander of estimated timing to...

and explorer

Exploration

Exploration is the act of searching or traveling around a terrain for the purpose of discovery of resources or information. Exploration occurs in all non-sessile animal species, including humans...

commonly credited as one of the first early modern Europe

Early modern Europe

Early modern Europe is the term used by historians to refer to a period in the history of Europe which spanned the centuries between the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, roughly the late 15th century to the late 18th century...

ans to land on the North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

n mainland aboard the Matthew

Matthew (ship)

The Matthew was a caravel sailed by John Cabot in 1497 from Bristol to North America, presumably Newfoundland. After a voyage which had got no further than Iceland, Cabot left again with only one vessel, the Matthew, a small ship , but fast and able. The crew consisted of only 18 people. The...

in 1497. Sebastian Cabot

Sebastian Cabot (explorer)

Sebastian Cabot was an explorer, born in the Venetian Republic.-Origins:...

was an Italian

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

explorer and may have sailed with his father John Cabot in May 1497. John Cabot and perhaps Sebastian, sailing from Bristol

Bristol

Bristol is a city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, with an estimated population of 433,100 for the unitary authority in 2009, and a surrounding Larger Urban Zone with an estimated 1,070,000 residents in 2007...

, took their small fleet along the coasts of a "New Found Land". There is much controversy over where exactly Cabot landed, but two likely locations that are often suggested are Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

and Newfoundland. Cabot and his crew (including perhaps Sebastian) mistook this place for China, without finding the passage to the east they were looking for. Some scholars maintain that the name America comes from Richard Amerik, a Bristol merchant and customs officer, who is claimed on very slender evidence to have helped finance the Cabot voyages.

Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier was a French explorer of Breton origin who claimed what is now Canada for France. He was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of the Saint Lawrence River, which he named "The Country of Canadas", after the Iroquois names for the two big...

was a French

French people

The French are a nation that share a common French culture and speak the French language as a mother tongue. Historically, the French population are descended from peoples of Celtic, Latin and Germanic origin, and are today a mixture of several ethnic groups...

navigator

Navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation. The navigator's primary responsibility is to be aware of ship or aircraft position at all times. Responsibilities include planning the journey, advising the Captain or aircraft Commander of estimated timing to...

who first explored and described the Gulf of St-Lawrence and the shores of the Saint Lawrence River

Saint Lawrence River

The Saint Lawrence is a large river flowing approximately from southwest to northeast in the middle latitudes of North America, connecting the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean. It is the primary drainage conveyor of the Great Lakes Basin...

, which he named Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

. Juan Fernández was a Spanish

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

explorer and navigator. Probably between 1563 and 1574 he discovered the Juan Fernández Islands

Juan Fernández Islands

The Juan Fernández Islands are a sparsely inhabited island group reliant on tourism and fishing in the South Pacific Ocean, situated about off the coast of Chile, and is composed of three main volcanic islands; Robinson Crusoe Island, Alejandro Selkirk Island and Santa Clara Island, the first...

west of Valparaíso

Valparaíso

Valparaíso is a city and commune of Chile, center of its third largest conurbation and one of the country's most important seaports and an increasing cultural center in the Southwest Pacific hemisphere. The city is the capital of the Valparaíso Province and the Valparaíso Region...

, Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

. He also discovered the Pacific islands of San Félix and San Ambrosio (1574). Among the other famous explorer

Exploration

Exploration is the act of searching or traveling around a terrain for the purpose of discovery of resources or information. Exploration occurs in all non-sessile animal species, including humans...

s of the period were Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira was a Portuguese explorer, one of the most successful in the Age of Discovery and the commander of the first ships to sail directly from Europe to India...

, Pedro Álvares Cabral

Pedro Álvares Cabral

Pedro Álvares Cabral was a Portuguese noble, military commander, navigator and explorer regarded as the discoverer of Brazil. Cabral conducted the first substantial exploration of the northeast coast of South America and claimed it for Portugal. While details of Cabral's early life are sketchy, it...

, Yermak

Yermak Timofeyevich

Yermak Timofeyevich , Cossack leader, Russian folk hero and explorer of Siberia. His exploration of Siberia marked the beginning of the expansion of Russia towards this region and its colonization...

, Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de León

Juan Ponce de León was a Spanish explorer. He became the first Governor of Puerto Rico by appointment of the Spanish crown. He led the first European expedition to Florida, which he named...

, Francisco Coronado, Juan Sebastián Elcano

Juan Sebastián Elcano

Juan Sebastián Elcano was a Basque Spanish explorer who completed the first circumnavigation of the world. As Ferdinand Magellan's second in command, Elcano took over after Magellan's death in the Philippines.-Early life:Elcano was born to Domingo Sebastián Elcano I and Catalina del Puerto...

, Bartolomeu Dias

Bartolomeu Dias

Bartolomeu Dias , a nobleman of the Portuguese royal household, was a Portuguese explorer who sailed around the southernmost tip of Africa in 1488, the first European known to have done so.-Purposes of the Dias expedition:...

, Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan was a Portuguese explorer. He was born in Sabrosa, in northern Portugal, and served King Charles I of Spain in search of a westward route to the "Spice Islands" ....

, Willem Barentsz, Abel Tasman

Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the VOC . His was the first known European expedition to reach the islands of Van Diemen's Land and New Zealand and to sight the Fiji islands...

, Jean Alfonse

Jean Alfonse

Jean Fonteneau dit Alfonse de Saintonge was a French navigator, explorer and corsair, prominent in the European age of discovery....

, Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain , "The Father of New France", was a French navigator, cartographer, draughtsman, soldier, explorer, geographer, ethnologist, diplomat, and chronicler. He founded New France and Quebec City on July 3, 1608....

, Willem Jansz, Captain James Cook

James Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

, Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson was an English sea explorer and navigator in the early 17th century. Hudson made two attempts on behalf of English merchants to find a prospective Northeast Passage to Cathay via a route above the Arctic Circle...

, and Giovanni da Verrazzano.

Peter Martyr d'Anghiera

Peter Martyr d'Anghiera

Peter Martyr d'Anghiera was an Italian-born historian of Spain and its discoveries during the Age of Exploration...

was an Italian

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

-born historian

Historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the study of all history in time. If the individual is...

of Spain

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

and of the discoveries of her representatives during the Age of Exploration. He wrote the first accounts of explorations in Central

Central America

Central America is the central geographic region of the Americas. It is the southernmost, isthmian portion of the North American continent, which connects with South America on the southeast. When considered part of the unified continental model, it is considered a subcontinent...

and South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

in a series of letters and reports, grouped in the original Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

publications of 1511-1530 into sets of ten chapters called "decades." His Decades are thus of great value in the history of geography and discovery. His De Orbe Novo (published 1530; "On the New World") describes the first contacts of Europeans and native Americans

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

and contains, for example, the first Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

an reference to India rubber.

Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt was an English writer. He is principally remembered for his efforts in promoting and supporting the settlement of North America by the English through his works, notably Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America and The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and...

was an English

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

writer, and is principally remembered for his efforts in promoting and supporting the settlement of North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

by the English

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

through his works, notably Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America (1582) and The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoueries of the English Nation (1598–1600).

European expansion

The maritime history of EuropeMaritime history of Europe

Maritime history of Europe is a term used to describe significant past events relating to the northwestern region of Eurasia in areas concerning shipping and shipbuilding, shipwrecks, naval battles, and military installations and lighthouses constructed to protect or aid navigation and the...

is a term used to describe significant past events relating to the northwestern region of Eurasia

Eurasia

Eurasia is a continent or supercontinent comprising the traditional continents of Europe and Asia ; covering about 52,990,000 km2 or about 10.6% of the Earth's surface located primarily in the eastern and northern hemispheres...

in areas concerning shipping

Shipping

Shipping has multiple meanings. It can be a physical process of transporting commodities and merchandise goods and cargo, by land, air, and sea. It also can describe the movement of objects by ship.Land or "ground" shipping can be by train or by truck...

and shipbuilding

Shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to before recorded history.Shipbuilding and ship repairs, both...

, shipwrecks, naval battle

Naval battle

A naval battle is a battle fought using boats, ships or other waterborne vessels. Most naval battles have occurred at sea, but a few have taken place on lakes or rivers. The earliest recorded naval battle took place in 1210 BC near Cyprus...

s, and military

Military

A military is an organization authorized by its greater society to use lethal force, usually including use of weapons, in defending its country by combating actual or perceived threats. The military may have additional functions of use to its greater society, such as advancing a political agenda e.g...

installations and lighthouses constructed to protect or aid navigation

Navigation

Navigation is the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another. It is also the term of art used for the specialized knowledge used by navigators to perform navigation tasks...

and the development of Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

. Although Europe is the world's second-smallest continent

Continent

A continent is one of several very large landmasses on Earth. They are generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, with seven regions commonly regarded as continents—they are : Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe, and Australia.Plate tectonics is...

in terms of area, is has a very long coastline, and has arguably been influenced more by its maritime history than any other continent. Europe is uniquely situated between several navigable sea

Sea

A sea generally refers to a large body of salt water, but the term is used in other contexts as well. Most commonly, it means a large expanse of saline water connected with an ocean, and is commonly used as a synonym for ocean...

s and intersected by navigable river

River

A river is a natural watercourse, usually freshwater, flowing towards an ocean, a lake, a sea, or another river. In a few cases, a river simply flows into the ground or dries up completely before reaching another body of water. Small rivers may also be called by several other names, including...

s running into them in a way which greatly facilitated the influence of maritime traffic and commerce.

When the carrack

Carrack

A carrack or nau was a three- or four-masted sailing ship developed in 15th century Western Europe for use in the Atlantic Ocean. It had a high rounded stern with large aftcastle, forecastle and bowsprit at the stem. It was first used by the Portuguese , and later by the Spanish, to explore and...

and then the caravel

Caravel

A caravel is a small, highly maneuverable sailing ship developed in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave her speed and the capacity for sailing to windward...

were developed by Portuguese

Portuguese people

The Portuguese are a nation and ethnic group native to the country of Portugal, in the west of the Iberian peninsula of south-west Europe. Their language is Portuguese, and Roman Catholicism is the predominant religion....

that European thoughts returned to the fabled East. These explorations have a number of causes. Monetarists believe the main reason the Age of Exploration began was because of a severe shortage of bullion in Europe. The European economy was dependent on gold and silver currency, but low domestic supplies had plunged much of Europe into a recession. Another factor was the centuries long conflict between the Iberians and the Muslims to the south. The eastern trade routes

Silk Road

The Silk Road or Silk Route refers to a historical network of interlinking trade routes across the Afro-Eurasian landmass that connected East, South, and Western Asia with the Mediterranean and European world, as well as parts of North and East Africa...

were controlled by the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

after the Turk

Turkish people

Turkish people, also known as the "Turks" , are an ethnic group primarily living in Turkey and in the former lands of the Ottoman Empire where Turkish minorities had been established in Bulgaria, Cyprus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Greece, Kosovo, Macedonia, and Romania...

s took control of Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

in 1453, and they barred Europeans from those trade routes. The ability to outflank the Muslim states of North Africa was seen as crucial to their survival. At the same time, the Iberians learnt much from their Arab neighbours. The carrack and caravel both incorporated the Mediterranean lateen sail that made ships far more manoeuvrable. It was also through the Arabs that Ancient Greek geography was rediscovered, for the first time giving European sailors some idea of the shape of Africa and Asia.

European colonization

In 1492, Christopher ColumbusChristopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

reached the Americas

Americas

The Americas, or America , are lands in the Western hemisphere, also known as the New World. In English, the plural form the Americas is often used to refer to the landmasses of North America and South America with their associated islands and regions, while the singular form America is primarily...

, after which European exploration and colonization rapidly expanding. The post-1492 era is known as the Columbian Exchange

Columbian Exchange

The Columbian Exchange was a dramatically widespread exchange of animals, plants, culture, human populations , communicable disease, and ideas between the Eastern and Western hemispheres . It was one of the most significant events concerning ecology, agriculture, and culture in all of human history...

period. The first conquests were made by the Spanish

Spain

Spain , officially the Kingdom of Spain languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Spain's official name is as follows:;;;;;;), is a country and member state of the European Union located in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula...

, who quickly conquered most of South

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

and Central America

Central America

Central America is the central geographic region of the Americas. It is the southernmost, isthmian portion of the North American continent, which connects with South America on the southeast. When considered part of the unified continental model, it is considered a subcontinent...

and large parts of North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

. The Portuguese

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

took Brazil

Brazil

Brazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

. The British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and Dutch

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

conquered islands in the Caribbean Sea

Caribbean Sea